Sticky Postings

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Friday, March 13. 2015

Via Eurekalert

-----

DURHAM, N.C. -- Using little more than a few perforated sheets of plastic and a staggering amount of number crunching, Duke engineers have demonstrated the world's first three-dimensional acoustic cloak. The new device reroutes sound waves to create the impression that both the cloak and anything beneath it are not there.

The acoustic cloaking device works in all three dimensions, no matter which direction the sound is coming from or where the observer is located, and holds potential for future applications such as sonar avoidance and architectural acoustics.

The study appears online in Nature Materials.

"The particular trick we're performing is hiding an object from sound waves," said Steven Cummer, professor of electrical and computer engineering at Duke University. "By placing this cloak around an object, the sound waves behave like there is nothing more than a flat surface in their path."

To achieve this new trick, Cummer and his colleagues turned to the developing field of metamaterials--the combination of natural materials in repeating patterns to achieve unnatural properties. In the case of the new acoustic cloak, the materials manipulating the behavior of sound waves are simply plastic and air. Once constructed, the device looks like several plastic plates with a repeating pattern of holes poked through them stacked on top of one another to form a sort of pyramid.

To give the illusion that it isn't there, the cloak must alter the waves' trajectory to match what they would look like had they had reflected off a flat surface. Because the sound is not reaching the surface beneath, it is traveling a shorter distance and its speed must be slowed to compensate.

"The structure that we built might look really simple," said Cummer. "But I promise you that it's a lot more difficult and interesting than it looks. We put a lot of energy into calculating how sound waves would interact with it. We didn't come up with this overnight."

To test the cloaking device, researchers covered a small sphere with the cloak and "pinged" it with short bursts of sound from various angles. Using a microphone, they mapped how the waves responded and produced videos of them traveling through the air.

Cummer and his team then compared the videos to those created with both an unobstructed flat surface and an uncloaked sphere blocking the way. The results clearly show that the cloaking device makes it appear as though the sound waves reflected off an empty surface.

Although the experiment is a simple demonstration showing that the technology is possible and concealing an evil super-genius' underwater lair is a long ways away, Cummer believes that the technique has several potential commercial applications.

"We conducted our tests in the air, but sound waves behave similarly underwater, so one obvious potential use is sonar avoidance," said Cummer. "But there's also the design of auditoriums or concert halls--any space where you need to control the acoustics. If you had to put a beam somewhere for structural reasons that was going to mess up the sound, perhaps you could fix the acoustics by cloaking it."

###

This research was supported by Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative grants from the Office of Naval Research (N00014-13-1-0631) and from the Army Research Office (W911NF-09-1-00539).

"Three-dimensional broadband omnidirectional acoustic ground cloak," Zigoneanu L., Popa, B., Cummer, S.A. Nature Materials, March 9, 2014. DOI: 10.1038/NMAT3901

Friday, May 02. 2014

Via Stuff

-----

Atmosferas sonoras en Villa Mairea

Javier Janda

Wednesday, February 12. 2014

And what about this prequel to Blur by architects Diller & Scofidio (during Swiss National Exhibition in 2002), the Pepsi Pavilion for the Expo '70" in Osaka, japan, by Fujiko Nakaya and E.A.T. (Experiments in Art & Technology: Robert Breer, Billy Klüver, Frosty Myers, Robert Whitman and David Tudor)!

Via Medien Kunst Netz

-----

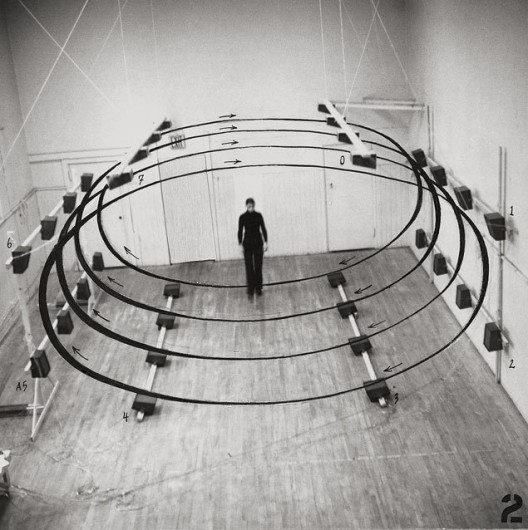

E.A.T. – Experiments in Art and Technology, «Pepsi Pavilion for the Expo '70», 1970

Pavilion exterior view

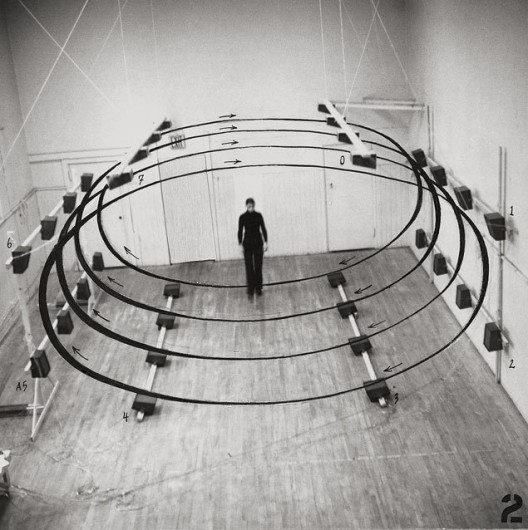

In September of 1968 Robert Breer introduced the members of E.A.T. to his neighbor, David Thomas of Pepsi Cola, who proposed that artists be involved in designing the Pepsi Pavilion for Expo ‘70 in Osaka, Japan. Breer and Billy Klüver chose Frosty Myers, Robert Whitman, and David Tudor to collaborate on the design of the Pavilion. As the design of the Pavilion developed, engineers and more artists were added to the project and given responsibility to develop specific elements. All in all 63 engineers, artists and scientists contributed to the design of the Pavilion. Outside the Pavilion, the dome, which had been decided on before we came into the project, was covered by a water vapor cloud sculpture, by Fujiko Nakaya. And on the plaza, seven of Robert Breer's Floats, six-foot high white sculptures, moved around slowly at less than 2 feet per minute, emitting sound. Four tall triangular towers held the lights for Myers’ Light Frame sculpture.

«The ‹Pepsi Pavilion› was first an experiment in collaboration and interaction between the artists and the engineers, exploring systems of feedback between aesthetic and technical choices, and the humanization of technological systems. Klüver‘s ambition was to create a laboratory environment, encouraging ‹live programming› that offered opportunity for experimentation, rather than resort to fixed or ‹dead programming› as he called it, typical of most exposition pavilions. [...] The Pavilion‘s interior dome–immersing viewers in three-dimensional real images generated by mirror reflections, as well as spatialized electronic music–invited the spectator to individually and collectively participate in the experience rather than view the work as a fixed narrative of pre-programmed events. The Pavilion gave visitors the liberty of shaping their own reality from the materials, processes, and structures set in motion by its creators.»

(Randall Packer, «The Pepsi Pavilion: Laboratory for Social Experimentation», in: Jeffrey Shaw/Peter Weibel (eds), Future Cinema. The cinematic Imaginary after Film, exhib. cat., The MIT Press, Cambridge (Mass.), London, 2003, p. 145.)

Wednesday, November 06. 2013

Via e-flux

-----

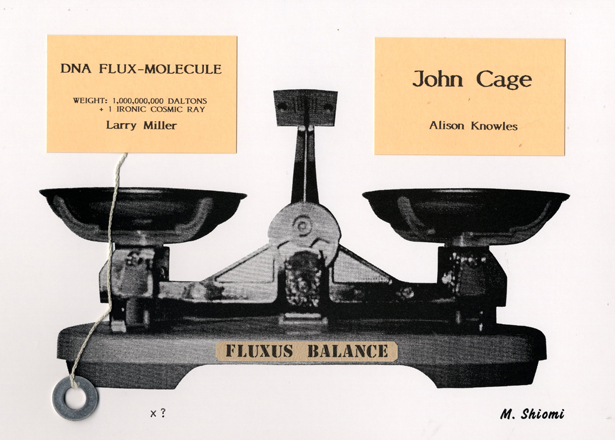

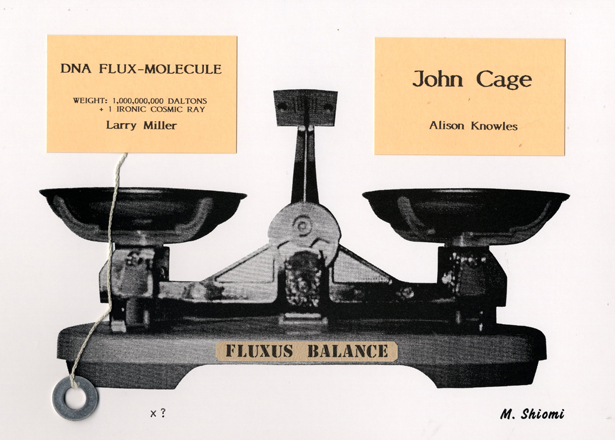

Shiomi Mieko, "Fluxus balance: version 1955, for 68 contributors," 1995. One from a portfolio of 68 prints, each 9 1/16 x 12 5/8 inches, edition of 10. Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2013 Shiomi Mieko.

New on post:

Shiomi Mieko, Poema Colectivo, Polish Radio Experimental Studio

The editors of post are delighted to announce Between New York and Tokyo: Fluxus and Graphic Scores, a selection of archival materials, artistic projects, and essays commissioned and edited by Miki Kaneda and Doryun Chong.

post.at.moma.org

In 1964, Shiomi Mieko sent a card to more than 200 artists spanning multiple continents inviting them to "write a word and place it somewhere." Shiomi's simple instruction exemplifies the spirit of openness, simplicity, and versatility that characterized the transnational artistic networks related to Fluxus in the 1960s. Between New York and Tokyo raises questions about artistic networks and their transformative potential still relevant today.

Materials include:

–Newly commissioned essays by artist Shiomi Mieko and art historian Midori Yoshimoto

–Rarely seen collections of Spatial Poems by Shiomi Mieko drawn from MoMA's holdings

–A video of pianist Fujii Aki performing Shiomi's Endless Box

–David Horvitz's Artist Breakfast, a contemporary, networked take on Shiomi's Spatial Poems, broadcast live on post

Appearing on post this fall:

Polish Radio Experimental Studio (PRES)

A selection of audio recordings, films, and musical notations produced by artists and composers linked to the Polish Radio Experimental Studio, a unique hub for experiments in sound and art established in Warsaw in 1957.

Poema Colectivo: Revolución and the International Mail Art Network

In 1981, the Mexican group Colectivo 3 initiated an international collective poem with the aim of investigating the theme "revolution." post presents images of the 310 works, newly commissioned essays, and primary documents translated for the first time.

Also on post:

Interviews

Bratescu: "The Studio Is Myself" / Dias's "Incomplete Biography" / Yamaguchi: Jikken Kobo / Yasunao: The "John Cage Shock" in Japan

Essays

Uesaki on Yokoo Tadanori / Hendricks on Fluxus / Ehrenberg on the archive as artwork / Ross on Iimura Takahiko

Places

Istanbul report by Superpool / The sounds of Japan's antinuclear movement by Novak / MoMA curators in Brazil, Central and Eastern Europe, and Japan

Practices

APN portfolios from the 1950s / Poetry performance by Augusto de Campos / Portfolio of Iimura Takahiko's film performances / Krakowiak's response to the Sogetsu Art Center

Features

Kaneda on experimental music in Japan / Hirasawa on 1960s Japanese film festivals

Workshops

Denegri on Gorgona—in English and Croatian / Montgomery on historicizing the 1960s and 1970s in Latin America / Crowley on sound experiments in the former Soviet Bloc / Bal's remarks on C-MAP / Longoni's reflections on decentering

post is an online platform developed by The Museum of Modern Art, and managed with an international network of partners and contributors. post launched in February 2013 with the aim of publishing research resources and artistic projects that engage with narratives falling outside art history's familiar accounts. Committed to investigating artistic practices that have historically been overlooked in MoMA's collection and exhibitions, post explores experimental practices in East Asia, Central and Eastern Europe, and Latin America and the Caribbean.

Adapting the attributes of an online journal, archive, exhibition space, and forum for research exchanges, post uses the characteristics of the Web to spark in-depth explorations of the ways in which modernism is being redefined, and link those topics to artists and institutions working today.

post grows out of Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP), a cross-departmental research program begun in 2009 at MoMA to facilitate a museum-wide study that reflects the multiplicity of modernities and histories of contemporary and modern art. Read more about C-MAP here.

To join the conversations and follow topics of interest to you, create a user profile that will keep you updated with activities on post.

post.at.MoMA.org

Friday, October 11. 2013

Via ArchDaily

-----

By Eric Baldwin

“The modern architect is designing for the deaf.” Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer makes a valid point. [1] The topic of sound is practically non-existent in modern architectural discourse. Why? We, as architects, think in terms of form and space; we balance scientific understanding and artistic vision. The problem is, we have a tendency to give ample thought to objects rather than processes and systems. Essentially, our field is ocular-centric by nature. So how do we start to “see” sound? And more importantly, how do we use it to promote health, safety and well-being?

So why does designing for our ears matter? Well, even if you happen to find yourself in an anechoic chamber right now, you’re still surrounded by sound. In 1910, a medical doctor by the name of Robert Koch, considered to be the founder of modern bacteriology, stated that: “One day people will have to fight noise just as relentlessly as they fight cholera and plague.” [2] His prediction came true: studies have shown that sound has a direct impact on our educational system, healthcare, and productivity in the workplace. As Julian Treasure states in his enlightening TED talk, “sound affects us physiologically, psychologically, cognitively, and behaviorally, all at the time.” For this reason, sound must be a consideration in the way we design; it is a constant that can dramatically improve or ruin our quality of life.

Meanwhile, the topic of Public Interest Design has gained significant momentum in the past couple years. The keynote speaker at the national AIA convention this year was none other than Cameron Sinclair, the vanguard of service-minded architecture. Teams like MASS Design Group and Sam Mockbee’s Rural Studio have gained international recognition. But taking a glimpse at their magnificent work, one is often left to wonder, did they consider sound? Can sound become a major aspect of Public Interest Design?

Looking at the photo above taken in the Butaro Hospital designed by MASS Design Group, you can easily notice the “big ass fans,” as co-founder Michael Murphy calls them. A major success in the project is the consideration of ventilation, which helps to mitigate transmission of airborne diseases. It is an idea that directly saves lives. But what do those fans sound like? Does the vaulted ceiling increase or decrease the intelligibility of speech? And in turn, do these combined effects decrease hospital personnel accuracy and patient recovery rates? With noise levels in hospitals having doubled in the last 40 years, these are the questions that are becoming more and more relevant – although too frequently left unasked [3]. Perhaps we are afraid of the answers.

So where do we begin? How can we “see” sound? Louis Roberts, an architect out of California, noted that one way he thinks about a design element like light is by asking “how will natural light pull someone through space?” [4] What we can begin to do is inquire about the nature of sound, and how it can “pull us” through space, as Roberts said. What would happen if we imagine sound as a continual mass, if we as architects design according to the patterns by which sound travels around and through space.

For example, the University of Virginia’s Sound Lounge uses an aural understanding to create “pockets” of conversation and increased intelligibility within a larger space. These same ideas can be adapted to a larger scale, within the context of a city, to tackle the problem of urban noise. Expanding further, LMN Architects are using parametric modeling and digital fabrication in their School of Music project to create an integrated acoustic system where lighting, speakers, and sprinklers are all part of a single ceiling surface. We can imagine facades, streetscapes, and interior spaces in the same manner.

In essence, these are general, minor steps, but it is time for architects to take those first steps and begin to truly listen. Let us design schools where children can better hear their teachers, hospitals where patients can fall sound asleep, and offices where workers can hear themselves think. But first of all, let’s ask ourselves the vital questions of “sound” design, and begin by truly listening to the answers.

References

[1] Robinson, Sarah. Nesting: Body, Dwelling, Mind. Richmond, CA: William Stout, 2011. Print.

[2] Kleilein, Doris. Tuned City: Zwischen Klang- Und Raumspekulation = Between Sound and Space Speculation. Idstein: Kook, 2008. Print.

[3] Work Group 44. Rep. no. 512. ANSI, 21 May 2009

[4] Roberts, Louis O.Man between Earth and Sky: A Symbolic Awareness of Architecture through a Process of Creativity. Carmel, CA: Octavio Pub., 2009. Print.

Making Space Resonate: Incorporating Sound Into Public-Interest Design originally appeared on ArchDaily, the most visited architecture website on 13 Sep 2013.

Personal comment:

I agree with the observation by E. Baldwin, when speaking about architecture, that "Essentially, our field is ocular-centric by nature" (or by design habits?) and therefore architecture is often oriented toward this primary, strong sense. So as most of our designed (visual) environments. Unfortunately I would add.

But I disagree with the idea that we should "see" what is invisible (Baldwin puts the "", so it is of course not trivial "seeing" that he's thinking about I believe), materialize it in the form of images or objects. When it comes to physiological or invisible parts of our livable environment, it is interesting not to necessarily bring them, again, in the visible field, but to also work with invisibility and physiology. To literally architecture them and make them fully part of our projects, sometimes also just as they are.

Thursday, October 10. 2013

Via The Guardian

-----

By Christopher Fox

Whether in the 1950s studios of Paris or Cologne, the first electronic sounds of the future were forged through graft and experimentation. Now those works speak vividly of their time

Model lineup … Kraftwerk used electronic music to tell us that it was here and now. Photograph: Steffen Schmidt/AP

Nothing dates faster than the future. Listen to any pop record and the thing that places it most precisely in time is the thing that was once so shiny and new. The electronic future is particularly susceptible to this ageing process; the synthesiser solo at the end of Ike and Tina Turner's "Nutbush City Limits" is totally 1973; the Auto-Tune on Cher's "Believe" is a time capsule from 1998.

It seems like a paradox. Part of the appeal of electronic music has always been the supposed neutrality of its sounds. A note played on a cello is freighted with history, but a sine tone is a sound so simple that it seems to exist in the natural world. The electronic music studios of the 1950s, the analogue synthesisers of the 60s and 70s, and the computers that in turn have replaced them have all used these simple sounds as their basic building blocks, but pass a sine tone through an electronic circuit and it emerges date‑stamped with the age of the technology and the aspirations of the musicians using it.

The science-fiction film Return to the Forbidden Planet is a classic example. In 1956, when the film was made, the future was electric, so the film's soundtrack is full of oscillators humming, swooshing and bleeping as the space cruiser C57D circles planet Altair IV. It's difficult to tell where the sound effects end and the musical underscoring begins; indeed, the creators of the soundtrack, Louis and Bebe Barron, appear in the title credits not as "composers" but as creators of "electronic tonalities".

In 1956 the future was alien and otherworldly. By 1974, Kraftwerk were using electronic music to tell us that it was here and now, the robotic repetitions of "Autobahn" an expression of the grids within which we lived our lives. A decade later, in derelict warehouses, looping melodies, bass lines and drum tracks pumped out the message that there was no future: only now, only raving. More recently the future seems to have become a thing of the past. New music is full of old electronic sounds, none more ubiquitous than Auto-Tune, as we yearn for the future that we used to believe in.

It's not just the old sounds that are the subject of this disillusion-fuelled nostalgia; it's the machines that made them, too. The remorseless march of progress, from valve to chip, tape to hard disk, studio to laptop, has been paused while musicians rummage around in the back of the cupboard, pulling out ancient reel-to-reel tape recorders and revelling in the quaint mechanical aura they give to any sound that passes through them. In 2002 the White Stripes recorded their Elephant CD the old-fashioned way, on tape; this year, it has been rereleased on vinyl on Jack White's own label. He denies he's a Luddite: "It's like I can't be proud of it unless I know we overcame some kind of struggle."

In the 50s, tape machines were at the heart of every studio. For the first time in history, sounds could be measured not just in time but in centimetres, as lengths of magnetic tape travelling past the record and playback heads of tape recorders. Sounds could be reversed, slowed down, speeded up and layered over and over again. For his Williams Mix, John Cage spent three years sticking bits of magnetic tape together. The tapes were in six categories – "city", "country", "electronic", "manually produced", "wind" and "small" – and, tying a satisfactory knot in the fabric of music history, they were recorded for Cage by Louis and Bebe Barron, the Barrons of The Forbidden Planet. Everything else was determined by chance: from which of the six sound categories each bit of tape should come, how long it should be, and finally, into which of eight tape sequences it was to be stuck. By 1953 the collage was complete and all eight tapes were played simultaneously: four minutes and 15 seconds of sonic mayhem.

Cage's work was part of a privately funded "Project for Music for Magnetic Tape". In Europe, the use of tape machines was at its most adventurous in the state-sponsored radio stations, nowhere more so than in Paris and Cologne. But there was an ideological split: Paris was the home of musique concrète, music made by recording and transforming the sounds of the world around us; Cologne was the headquarters of elektronische musik, using the applied science of oscillators and filters to construct new sounds for a new world. It's an aesthetic axis around which musicians still orientate themselves. Do you start with a sound recorded from the real world, with all its intrinsic life, or do you build new sounds from scratch?

At its simplest it's a distinction between surrealism and abstraction. The microphone is a lens which allows the sounds around us to be captured, then cropped, stretched, juxtaposed. 'Art exists to help us to recover the sensation of life […] the technique […] is to make things "unfamiliar"', said Viktor Shklovsky in 1916, but it could have been the pioneer of musique concrète, Pierre Schaeffer, explaining the aesthetics of the Paris studio. Or it could have been Schaeffer's colleague Pierre Henry in 1963 explaining how he transformed the creak of a door-hinge and an exhalation into a series of 25 variations for a door and a sigh.

In fact, Shklovsky was writing Russian literary theory, introducing his concept of "ostranenie" (making strange) – an idea waiting for the technology to turn it from words into sounds. Record, cut, stick, loop – it's an endlessly fascinating technique that probably crossed over into mass consciousness in 1973 with Pink Floyd's cash-register riff on "Money". Certainly the university music text-books of the time were happy to claim the mix of synths and sound collage on The Dark Side of the Moon as an affirmation of electronic music and musique concrète's capacity to engage with a pop sensibility.

But sound recording is always a means of making strange. It's an act of selection: what sort of microphone, where to put it, when to begin, when to end? Opening and closing our eyes is easy; it's much harder to close our ears, so deciding to listen to just this, for just this long, is quite unnatural. Nevertheless, there are composers and sound artists who have devoted themselves to the illusion that the world recorded in sound is the world itself. It's an idea that keeps coming round: in the 1970s, Hildegard Westerkamp and R Murray Schafer tried to document disappearing 'acoustic ecologies' with their Soundscapes project. These days it's called "field recording" and the doyen is Chris Watson, who last year made In Britten's Footsteps, an audio recreation of the landscape around Benjamin Britten's home in Aldeburgh.

My favourite soundscape is a glorious hybrid, Luc Ferrari's Presque Rien (1967–70). It sounds like a field recording – early morning in a Croatian fishing village – but it can't be: first light of day is compressed into just over 20 minutes, artifice masquerading as nature. Perhaps hybrids flourish best. In the 1950s, Stockhausen worked in the Cologne studios of West German Radio and his first tape works, two Electronic Studies, were on the elektronische musik side of the great aesthetic divide. In 1955, however, he decided to embark on a hybrid, and his new work, Gesang der Jünglinge (Song of the Youths), combined pure electronic sounds with the recorded voice of a boy singing passages from the Old Testament story of the three young men who miraculously survived after being cast into King Nebuchadnezzar's fiery furnace.

It is an extraordinarily ambitious conception: at over 13 minutes, it is longer than any other electronic work of the period and, though composed at a time when stereo was still a novelty, it is in five-channel sound. Above all, it's full of life. Stockhausen – in those days a Roman Catholic – had intended to create an "electronic mass", but the vivid juxtaposition of the boy's voice, alone but resolute, amid the bubbling cauldron of electronic sound proved a much better idea. The humanity of a solo voice set in an abstract electronic landscape is a powerful and recurrent musical image, whether in Milton Babbit's 1964 Philomel for solo soprano and tape, or Donna Summer's "I feel love".

Aesthetic breakthroughs … Karlheinz Stockhausen in the mid 1960s. Photograph: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis

Gesang der Jünglinge was a technical and aesthetic breakthrough, but Stockhausen's next studio project was even more remarkable. In Kontakte (Contacts), the real-world sounds are live, played by a pianist and a percussionist, and Stockhausen brings off a series of spectacular aural illusions in which prerecorded tape sounds appear to imitate, anticipate and transform the sounds of the live instruments before taking off into another world of their own. That Stockhausen could bully the banks of oscillators, filters and modulators in the Cologne studio into producing such amazing trompes l'oreille is a tribute to his imagination and his industry: it took him more than two years to complete.

These days, Kontakte would take weeks rather than years. The instrumental sounds could be sampled, analysed and remodelled in any one of a number of readily available software programmes, and perhaps that's another reason why the future isn't as interesting as it used to be. Computers started out in music in the 50s by emulating the simpler electronic devices of the period – oscillators and filters don't need much processing power – and in its early days, computer music was just that: music that sounded as if it had come out of a computer. But as computers grew quicker and stronger, they became more self-effacing; instead of buzzing and bleeping, they began to mimic familiar musical instruments. Yamaha's DX7, the smartest synth in town in the early 80s, used sophisticated maths to produce simulacra of acoustic instrumental sounds. It couldn't replicate them exactly, but, in the midst of a pop-song mix, the sounds were convincing enough, a sort of musical mock-Tudor.

These days, computers can recreate not only the instrument but the acoustic around it. Whether recording and editing the real world, or generating new sounds, it's all easy with a laptop; under the keyboard on which I'm typing this article there is space for the digital equivalent of rooms full of equipment from the old Cologne and Paris studios. All too easy? Possibly. Gesang der Jünglinge and Kontakte are masterpieces. That's why they're being featured in the Southbank Centre's year-long celebration of 20th-century music, The Rest is Noise. But, at least in part, they're masterpieces because of the resistance of the materials with which Stockhausen had to work, the intractability of all that old technology. Perhaps it's time to invent a new future.

• Christopher Fox will introduce Stockhausen's Gesang der Jünglinge and Kontakte in the Queen Elizabeth Hall, London SE1, tonight. southbankcentre.co.uk.

Tuesday, July 02. 2013

Via Triangulation

-----

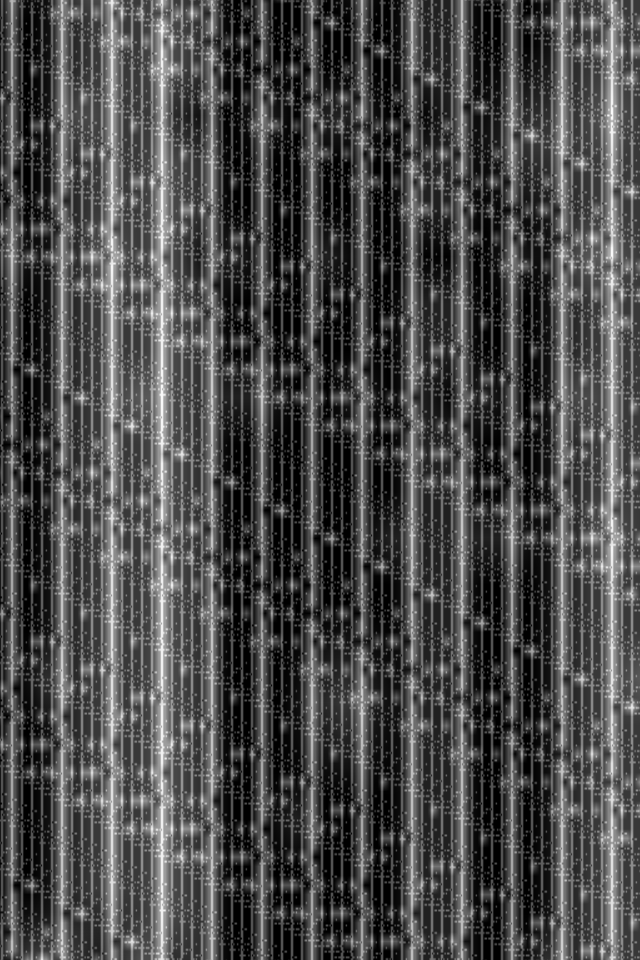

"PURE FLOW is a mobile artwork by Katy Connor that reveals new perceptions of technological systems, transforming the iPhone and iPad into a Live probe revealing the noise between GPS satellites, 3G networks and Wifi hotspots as a tangible presence in the environment.

PURE FLOW visualises these signals as a sliver of fluctuating white noise, responding directly to the movement and immediate environment of the device. The user can directly manipulate the outcomes, by touching the visual and sonic patterns triggered by fluctuations in the data, sampling this immersive and enveloping field." See more;

"PURE FLOW visualises the instability and fragility of Live signals, passing through cloud cover, being absorbed by bodies, reflecting off concrete and refracting through glass. The APP subverts the use-value of GPS as a surveying and navigational tool; revealing these invisible data streams and highlighting their ubiquity, as sophisticated military technologies become key components in daily life."

Download it here.

Monday, April 22. 2013

Via Architecture Source via Archinect

-----

soundscraper. Source: eVolo 2013 Skyscraper Competition

Soundscrapers could soon turn urban noise pollution into usable energy to power cities.

An honourable mention-winning entry in the 2013 eVolo Skyscraper Competition, dubbed Soundscraper, looked into ways to convert the ambient noise in urban centres into a renewable energy form.

Noise pollution is currently a negative element of urban life but it could soon be valued and put to good use.

Acoustic architecture, or design to minimise noise, has long been an important facet of the architecture industry, but design aimed at maximising and capturing noise for beneficial reasons is an untapped area with great potential.

The Soundscraper concept is based around constructing the buildings near major highways and railroad junctions to capture noise vibrations and turn them into energy. The intensity and direction of urban noise dictates the vibrations captured by the building’s facade.

Covering a wide array of frequencies, everyday noise from trains, cars, planes and pedestrians would be picked up by 84,000 electro-active lashes covering a Soundscraper’s light metallic frame. Armed with Parametric Frequency Increased Generators (sound sensors) on the lashes, the vibrations would then be converted to kinetic energy through an energy harvester.

soundscraper. Source: eVolo 2013 Skyscraper Competition

The energy would be converted to electricity through transducer cells, at which point that power could be stored or sent to the grid for regular electricity usage.

The Soundscraper team of Julien Bourgeois, Savinien de Pizzol, Olivier Colliez, Romain Grouselle and Cédric Dounval estimate that 150 megawatts of energy could be produced from one Soundscraper, meaning that a single tower could produce enough energy to fuel 10 percent of Los Angeles’ lighting needs.

Constructing several 100-metre high Soundscrapers throughout a city near major motorways could help offset the electrical needs of the urban population. This form of renewable energy would also help lower the city’s CO2 emissions.

The energy-producing towers could become city landmarks and give interstitial spaces an important function. The electricity needs of an entire city could be met solely by Soundscrapers if enough were constructed at appropriate locations, also helping to minimise the city’s carbon footprint.

Tuesday, October 30. 2012

Via The Creators Project

-----

No matter how compact, portable, and convenient music formats get, somehow there is still a market for vinyl. If folks are that attached to impractically large plastic discs and are willing to continue buying them for the sake of purism, then why not take things in the other direction? Sound artist Yuri Suzuki designed The Sound of Earth, a custom globe which essentially acts as a spherical record, with the track spiraling all the way around it from top to bottom.

The music itself is choppy and abstract, and yet it has an almost rhythmic feel as the needle glides over various land masses. Described by Guardian as “a surreal mashup of field recordings taken by Suzuki on his travels, along with fragments of national anthems and folk music.”

As you can hear in the video above, it sounds like something between a skipping record and scrolling through FM radio stations. We’re curious as to what it sounds like when the stylus reaches Brooklyn.

[via: Fact]

@ImYourKid

|