Sticky Postings

All 242 fabric | rblg updated tags | #fabric|ch #wandering #reading

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Wednesday, January 26. 2022

Platform of Future-Past (2022) at HOW Art Museum in Shanghai | #data #monitering #installation

Note:

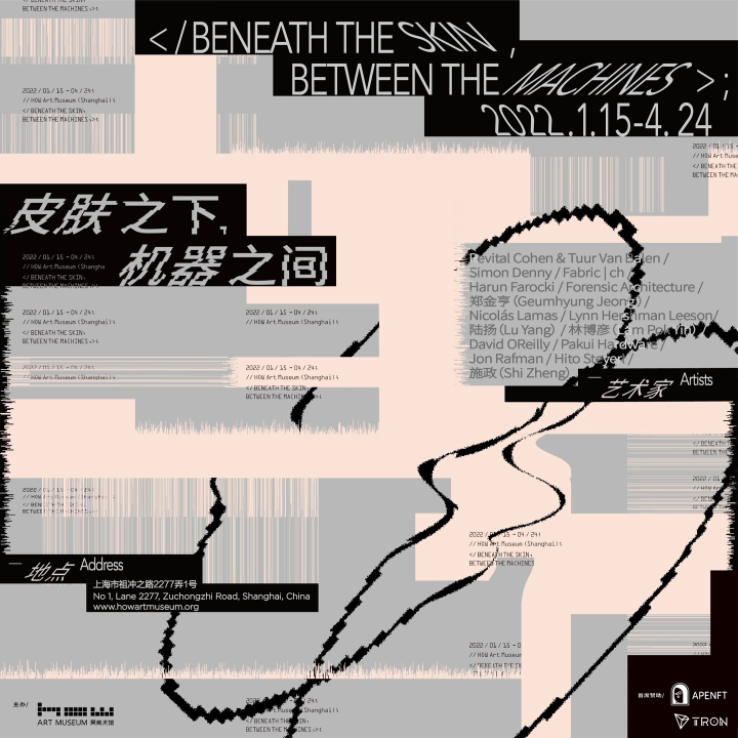

The exhibition Beneath the Skin, Between the Machines just opened at HOW Art Museum (Hao Art Gallery) and fabric | ch was keen to be invited to create a large installation for the show, also intented to be used during a symposium that will be entirely part of the exhibition (panels and talks as part of the installation therefore). The exhibition will be open between January 15 - April 24 2022 in Shanghai.

Along with a selection of chinese and international artists, curator Liaoliao Fu asked us to develop a proposal based on a former architectural device, Public Platform of Future-Past, which in itself was inspired by an older installation of ours... Heterochrony.

This new work, entitled Platform of Future-Past, deals with the temporal oddity that can be produced and induced by the recording, accumulation and storage of monitoring data, which contributes to leaving partial traces of "reality", functioning as spectres of the past.

We are proud to present this work along artists such as Hito Steyerl, Geumhyung Jeong, Lu Yang, Jon Rafman, Forensic Architecture, Lynn Hershman Leeson and Harun Farocki.

...

Last but not least and somehow a "sign of the times", this is the first exhibition in which we are participating and whose main financial backers are a blockchain and crypto-finance company, as well as a NFT platform. Both based in China.

More information about the symposium will be published.

Via Pro Helvetia

-----

-----

Curatorial Statement

By Fu Liaoliao and the curatorial team

"Man is only man at the surface. Remove the skin, dissect, and immediately you come to machinery.” When Paul Valéry wrote this down, he might not foresee that human beings – a biological organism – would indeed be incorporated into machinery at such a profound level in a highly informationized and computerized time and space. In a sense, it is just as what Marx predicted: a conscious connection of machine[1]. Today, machine is no longer confined to any material form; instead, it presents itself in the forms of data, coding and algorithm – virtually everything that is “operable”, “calculable” and “thinkable”. Ever since the idea of cyborg emerges, the man-machine relation has always been intertwined with our imagination, vision and fear of the past, present and future.

In a sense, machine represents a projection of human beings. We human beings transfer ideas of slavery and freedom to other beings, namely a machine that could replace human beings as technical entities or tools. Opposite (and similar, in a sense,) to the “embodiment” of machine, organic beings such as human beings are hurrying to move towards “disembodiment”. Everything pertinent to our body and behavior can be captured and calculated as data. In the meantime, the social system that human beings have created never stops absorbing new technologies. During the process of trial and error, the difference and fortuity accompanying the “new” are taken in and internalized by the system. “Every accident, every impulse, every error is productive (of the social system),”[2] and hence is predictable and calculable. Within such a system, differences tend to be obfuscated and erased, but meanwhile due to highly professional complexities embedded in different disciplines/fields, genuine interdisciplinary communication is becoming increasingly difficult, if not impossible.

As a result, technologies today are highly centralized, homogenized, sophisticated and commonized. They penetrate deeply into our skin, but beyond knowing, sensing and thinking. On the one hand, the exhibition probes into the reconfiguration of man by technologies through what’s “beneath the skin”; and on the other, encourages people to rethink the position and situation we’re in under this context through what’s “between the machines”. As an art institute located at Shanghai Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone, one of the most important hi-tech parks in China, HOW Art Museum intends to carve out an open rather than enclosed field through the exhibition, inviting the public to immerse themselves and ponder upon the questions such as “How people touch machines?”, “What the machines think of us?” and “Where to position art and its practice in the face of the overwhelming presence of technology and the intricate technological reality?”

Departing from these issues, the exhibition presents a selection of recent works of Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, Simon Denny, Harun Farocki, Nicolás Lamas, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Lu Yang, Lam Pok Yin, David OReilly, Pakui Hardware, Jon Rafman, Hito Steyerl, Shi Zheng and Geumhyung Jeong. In the meantime, it intends to set up a “panel installation”, specially created by fabric | ch for this exhibition, trying to offer a space and occasion for decentralized observation and participation in the above discussions. Conversations and actions are to be activated as well as captured, observed and archived at the same time.

[1] Karl Marx, “Fragment on Machines”, Foundations of a Critique of Political Economy

[2] Niklas Luhmann, Social Systems

-----

Schedule

Duration: January 15-April 24, 2022

Artists: Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, Simon Denny, fabric | ch, Harun Farocki, Geumhyung Jeong, Nicolás Lamas, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Lu Yang, Lam Pok Yin, David OReilly, Pakui Hardware, Jon Rafman, Hito Steyerl, Shi Zheng

Curator: Fu Liaoliao

Organizer: HOW Art Museum, Shanghai

Lead Sponsor: APENFT Foundation

Swiss participation is supported by Pro Helvetia Shanghai, Swiss Arts Council.

(Swiss speakers and performers appearing in the educational events will be updated soon.)

-----

Work by fabric | ch

HOW Art Museum has invited Lausanne-based artist group fabric | ch to set up a “panel installation” based on their former project “Public Platform of Future Past” and adapted to the museum space, fostering insightful communication among practitioners from different fields and the audiences.

“Platform of Future-Past” is a temporary environmental device that consists in a twenty meters long walkway, or rather an observation deck, almost archaeological: a platform that overlooks an exhibition space and that, paradoxically, directly links its entrance to its exit. It thus offers the possibility of crossing this space without really entering it and of becoming its observer, as from archaeological observation decks. The platform opens- up contrasting atmospheres and offers affordances or potential uses on the ground.

The peculiarity of the work consists thus in the fact that it generates a dual perception and a potential temporal disruption, which leads to the title of the work, Platform of Future-Past: if the present time of the exhibition space and its visitors is, in fact, the “archeology” to be observed from the platform, and hence a potential “past,” then the present time of the walkway could be understood as a possible “future” viewed from the ground…

“Platform of Future-Past” is equipped in three zones with environmental monitoring devices. The sensors record as much data as possible over time, generated by the continuously changing conditions, presences and uses in the exhibition space. The data is then stored on Platform Future-Past’s servers and replayed in a loop on its computers. It is a “recorded moment”, “frozen” on the data servers, that could potentially replay itself forever or is waiting for someone to reactivate it. A “data center” on the deck, with its set of interfaces and visualizations screens, lets the visitors-observers follow the ongoing process of recording.

The work could be seen as an architectural proposal built on the idea of massive data production from our environment. Every second, our world produces massive amounts of data, stored “forever” in remote data centers, like old gas bubbles trapped in millennial ice.

As such, the project is attempting to introduce doubt about its true nature: would it be possible, in fact, that what is observed from the platform is already a present recorded from the past? A phantom situation? A present regenerated from the data recorded during a scientific experiment that was left abandoned? Or perhaps replayed by the machine itself ? Could it already, in fact, be running on a loop for years?

Platform of Future-Past, Scaffolding, projection screens, sensors, data storage, data flows, plywood panels, textile partitions

-----

Platform of Future-Past (2022)

-----

Beneath the Skin, Between the Machines (exhibition, 01.22 - 04.22)

-----

Platform of Future-Past was realized with the support of Pro Helvetia.

Tuesday, September 21. 2021

"Essais climatiques" by P. Rahm, Ed. B2 (Paris, 2020) | #2ndaugmentation #essay #AR #VR

Note: it is with great pleasure and interest that I read recently one of Philippe Rahm's last publication, "Essais climatiques" (published in French, by Editions B2), which consists in fact in a collection of articles published in the past 10+ years in various magazines, journals and exhibition catalogs. It is certainly less developed than the even more recent book, "L'histoire naturelle de l'architecture" (ed. Pavillon de l'Arsenal, 2020), but nonetheless an excellent and brief introduction to his thinking and work.

Philippe Rahm's call for the "return" of an "objective architecture", climatic and free of narrative issues, is of great interest. Especially at a time when we need to reduce our CO2 emissions and will need to reach energy objectives of slenderness. The historical reading of the postmodern era (in architecture), in relation to oil, vaccines and antibiotics is also really valuable in this context, when we are all looking to move forward this time in cultural history.

I also had the good surprise, and joy, to see the text "L'âge de la deuxième augmentation" finally published! It was written by Philippe back in 2009 probably, about the works of fabric | ch at the time, when we were preparing a publication that finally never came out... Though this text will also be part of a monographic publication that is expected to be finalized and self-published in 2022.

Via fabric | ch

-----

Wednesday, August 25. 2021

Cloud of Cards – A design research publication, ed. ECAL, Hemisphere & Frame magazines (2019 – 2020) | #design #research #datacenters #infrastructure

Note: still catching up on past publications, these ones (Cloud of Cards and related) are "pre-covid times", in Print-on-Demand and related to a the design research on data and the cloud led jointly between ECAL / University of Art & Design, Lausanne and HEAD - Genève (with Prof. Nicolas Nova). It concerns mainly new propositions for hosting infrastructure of data, envisioned as "personal", domestic (decentralized) and small scale alternatives. Many "recipes" were published to describe how to creatively hold you data yourself.

It can also be accessed through my academia account, along with it's accompanying publication by NIcolas Nova: Cloud of Practices.

-----

By Patrick Keller

--

The same research was shortly presented in the Swiss journal Hemispheres, as well as in the international magazine Frame:

--

Making Sense – A publication about design research, (ed. D. Fornari), ECAL (Lausanne, 2017) | #iiclouds #datacenter #research

Note: to catch up on time and work with the documentation of our past publications, this one was published already some time ago by ECAL / University of Art and Design, Lausanne (HES-SO), but still a topical issue (> how to redesign/codesign datacenters and the access to personal data in both a sustainable and "fair" way for the end user?)

We're currently working on an evolution of this project that involves the recent decentralized technologies that emerged in the meantime (a.k.a "blockchains", "NFT", etc.). In the meantime, we are preparing academic talks on the subject with the media sociologist Joël Vacheron, who will be invoved in the next phases of the research -- would they happen... --

-----

By Patrick Keller

(sorry for the strange colors on these 3 img. below...)

Monday, November 23. 2015

The Information Age Is Over. Welcome to the Infrastructure Age | #infrastructure

Note: this article was published a while ago and was rebloged here and there already. I kept it in my pile of "interesting articles to read later when I'll have time" for a long time as well therefore. But it make sense to post it in conjunction with the previous one about Norman Foster and by extension with the otehr one concerning the Chicago Biennial.

It is also sometimes interesting to read posts with delay, when the hype and buzzwords are gone. Written in the aftermath of the Tesla annoncement about its home battery (Powerwall), the article was all about energy revolution. But since then, what? We're definitely looking forward...

Via Gizmodo

-----

Photo: SpaceX

Nobody wants to say it outright, but the Apple Watch sucks. So do most smartwatches. Every time I use my beautiful Moto 360, its lack of functionality makes me despair. But the problem isn’t our gadgets. It’s that the future of consumer tech isn’t going to come from information devices. It’s going to come from infrastructure.

That’s why Elon Musk’s announcements of the new Tesla battery line last night were more revolutionary than Apple Watch and more exciting than Microsoft’s admittedly nifty HoloLens. Information tech isn’t dead — it has just matured to the point where all we’ll get are better iterations of the same thing. Better cameras and apps for our phones. VR that actually works. But these are not revolutionary gadgets. They are just realizations of dreams that began in the 1980s, when the information revolution transformed the consumer electronics market.

But now we’re entering the age of infrastructure gadgets. Thanks to devices like Tesla’s household battery, Powerwall, electrical grid technology that was once hidden behind massive barbed wire fences, owned by municipalities and counties, is now seeping slowly into our homes. And this isn’t just about alternative energy like solar. It’s about how we conceive of what technology is. It’s about what kinds of gadgets we’ll be buying for ourselves in 20 years.

It’s about how the kids of tomorrow won’t freak out over terabytes of storage. They’ll freak out over kilowatt-hours.

Beyond transforming our relationship to energy, though, the infrastructure age is about where we expect computers to live. The so-called internet of things is a big part of this. Our computers aren’t living in isolated boxes on our desktops, and they aren’t going to be inside our phones either. The apps in your phone won’t always suck you into virtual worlds, where you can escape to build treehouses and tunnels in Minecraft. Instead, they will control your home, your transit, and even your body.

Once you accept that the thing our ancestors called the information superhighway will actually be controlling cars on real-life highways, you start to appreciate the sea change we’re witnessing. The internet isn’t that thing in there, inside your little glowing box. It’s in your washing machine, kitchen appliances, pet feeder, your internal organs, your car, your streets, the very walls of your house. You use your wearable to interface with the world out there.

It makes perfect sense to me that a company like Tesla could be at the heart of the new infrastructure age. Musk’s focus has always been relentlessly about remolding the physical world, changing the way we power our transit — and, with SpaceX, where future generations might live beyond Earth. The opposite of cyberspace is, well, physical space. And that’s where Tesla is taking us.

But in the infrastructure age, physical space has been irrevocably transformed by cyberspace. Now we use computers to experience the world in ways we never could before computer networks and data analysis, using distributed sensor devices over fault lines to give people early warnings about earthquakes that are rippling beneath the ground — and using satellites like NASA’s SMAP to predict droughts years before they happen.

Of course, there are the inevitable dangers that come with infusing physical space with all the vulnerabilities of cyberspace. People will hack your house; they’ll inject malicious code into delivery drones; stealing your phone might become the same thing as stealing your car. We’ll still be mining unsustainably to support our glorious batteries and photovoltaics and smart dance clubs.

But we will also benefit enormously from personalizing the energy grid, creating a battery-powered hearth for every home. Plus the infrastructure age leads directly into outer space, to tackle big problems of human survival, and diverts our impoverished attention spans from gazing neurotically at the social scene unfolding in tiny glowing rectangles on our wrists.

The information age brought us together, for better or worse. It allowed us to understand our environment and our bodies in ways we never could before. But the infrastructure age is what will prevent us from killing ourselves as we grow up into a truly global civilization. That is far more important, and exciting, than any gold watch could ever be.

Norman Foster: "I have no power as an architect, none whatsoever" | #energy #sustainability

Note: Meanwhile, on the "big architects" end of the spectrum... Where I enjoyed to read the sentence " Foster is delighted that Britain now has an infrastructure commission, chaired by Andrew Adonis, which he says gives the opportunity to plan in 30-year cycles and remove the politics from infrastructure."

Via The Guardian

-----

By Rowan Moore

Norman Foster’s Millau viaduct in France, which has ‘cut out five-hour traffic jams’. Photograph: Michael Reinhard/Corbis

“Do you believe in infrastructure?” asks Norman Foster, with challenge in his voice. He does. Infrastructure, he says, is about “investing not to solve the problems of today but to anticipate the issues of future generations”. He cites his hero, Joseph Bazalgette, who, in solving Victorian London’s sewage problems, “thought holistically to integrate drains with below-ground public transportation and above-ground civic virtue”.

Foster is delighted that Britain now has an infrastructure commission, chaired by Andrew Adonis, which he says gives the opportunity to plan in 30-year cycles and remove the politics from infrastructure. He will expound these views this week at the Urban Age 10th anniversary Global Debates, Urban Age being the LSE’s Deutsche Bank-sponsored series of conferences in which high-powered and highly powerful people travel the world exchanging views on city building.

Statistics spin out of him about sustainability. “If you take the carbon footprint of London, that’s one seventh of that of Atlanta, so there’s a relationship between density and emissions. The whole climate change issue, which many would argue is about the survival of the species, comes down to urbanism.

Foster’s proposed design for the Thames Hub airport. Photograph: dbox/Foster & Partners

“When I was in Harvard recently, I said that each of us in this room, the energy that we consume in one year would equal the energy consumed by two Japanese, 13 Chinese, 31 Indians and 370 Ethiopians. So you start to take the relationship between energy consumed by a society and infant mortality, life expectancy, sexual freedom, academic freedom, freedom from violence. So those societies that consume more energy have more of those desirable qualities, so all those issues are inseparable from the nature of the infrastructure.” The connections between these points are not always clear, but the argument seems to be that better use of energy through better infrastructure will enable more people to live better.

Of his own work, Foster says that many of the most important projects are not what are normally considered buildings, but things such as the Millennium Bridge, the pedestrianisation of Trafalgar Square in London, the Millau viaduct in southern France and the remaking of the Marseille waterfront. More statistics: “Millau cut out five-hour traffic jams, which meant that the saving in CO2 from the 10% of traffic that is heavy good vehicles had an effect equivalent to a forest of 40,000 trees.”

He has campaigned vigorously for the Thames Hub, a new airport in the Thames estuary with an associated network of huge ambition: an orbital railway around London, a flood barrier, tidal energy generation. He is profoundly disappointed that his plan is likely to be rejected in favour of an expanded Heathrow: “The reality of a hub airport is that you can never ever do that at Heathrow. If you do that at Heathrow now you can absolutely guarantee that we will still be pedalling furiously to stand still. You can never accommodate long-term needs there.”

Norman Foster: ‘The whole climate change issue comes down to urbanism.’ Photograph: Manolo Yllera

But given what he just said about sustainability, should we be expanding airports at all? “Do you eat meat?” he asks scathingly. “You’re probably going to have your hamburger in spite of the fact that you’re going to make a much greater impact than any travel.” Air travel, he says, “compares well statistically with the amount of methane produced by cows and the amount of energy and water needed to produce a hamburger”.

“The reality is that all society is embedded in mobility. You’re going to take that flight. You’d be better to take the flight out of an airport that is driven by tidal power and which uses natural light, and which anticipates the day when air travel will be more sustainable.” He talks of solar-powered flight and planes made of lightweight composite materials.

It could also be asked what is the role of the architect in what is generally the province of engineers, planners and politicians. Around us is evidence of his practice’s apparent potency – towers in China and India, a model of the giant circle, one mile in circumference, which will be Apple’s new headquarters, images of a concept for habitats on Mars – but Foster says: “I have no power as an architect, none whatsoever. I can’t even go on to a building site and tell people what to do.” Advocacy, he says, is the only power an architect ever has.

To write about Foster presents a particular challenge to an architecture critic. The scale of his achievement is immense and he has created many outstanding buildings. A wise man recently pointed out that if Foster had only built his 20 or 30 best works, critical admiration would be virtually unqualified. It is largely because his practice has designed many more projects than this that he sometimes gets a bad press. But would it really have been better if he had confined himself to a boutique practice in order to preserve his architectural purity?

It can seem peevish and petty to question his work, but it is not beyond criticism. In particular, it can become weaker the more it makes contact with realities outside itself. If you look upwards in the Great Court he designed in the British Museum, you will see an impressive structure of steel and glass, but at your own level it becomes bland and sometimes clumsy. The Gherkin is a memorable presence on the London skyline, but awkward at pavement level. The Millennium Bridge, even with the modifications necessary to stop it wobbling, is confident and elegant except at its landing, where the overhang of its cantilever creates spaces that are plain nasty.

In the context of infrastructure, the question is also whether it adapts to the political, social and physical conditions that surround it. In answer to Foster’s question, yes, I do believe in infrastructure. Or, rather, I’d compare it to water: essential to existence, life-enhancing and sometimes beautiful, but with the power to damage and destroy if misused.

Design for the proposed drone-port project in Rwanda. Photograph: Foster & Partners

All this makes a new drone-port project in Rwanda one of Foster and Partners’ most intriguing. Conceived with Jonathan Ledgard, the director of Afrotech, who describes himself as a thinker on the future of Africa, it is a plan to create a network of cargo drones that can bring medical supplies and blood, plus spare parts, electronics and e-commerce, to hard-to-access parts of Africa. The drones have ports – shelters where they can safely land and unload, but which also serve as “a health clinic, a digital fabrication shop, a post and courier room, and an e-commerce trading hub, allowing it to become part of local community life”. Because of their inaccessible locations, they have to be built using materials close to hand, so techniques have been developed for efficiently making local earth into bricks and stones into foundations.

It is impossible at this point and at this distance to know if the drone-port project will achieve what it hopes, but its ambition to adapt to local conditions seems absolutely to the point. The interesting question is then how to bring the same thinking to infrastructure in a developed country, such as Britain. What is the right infrastructure for the society and culture of this country, at this point? Has it changed since Foster’s Victorian heroes, such as Bazalgette, did their work? Can we import the large-scale thinking of modern China and, if so, with what modification? These are good questions for an architect to address.

Urban Age Global Debates run until 3 December; lsecities.net/ua

Related Links:

Friday, October 02. 2015

I&IC at Renewable Futures Conference in Riga | #thinking #speculation #futures

Via iiclouds.org

-----

The design research Inhabiting and Interfacing the Cloud(s) will be presented during the peer reviewed Renewable Futures Conference next week in Riga (Estonia), which will be the first edition of a serie that promiss to scout for radical approaches.

Christophe Guignard will introduce the participants to the stakes and the progresses of our ongoing experimental work. There will be profiled and inspiring speakers such as Lev Manovitch, John Thackara, Andreas Brockmann, etc.

Christophe Guignard will make a short “follow up” about the conference on this blog once he’ll be back from Riga.

Monday, September 28. 2015

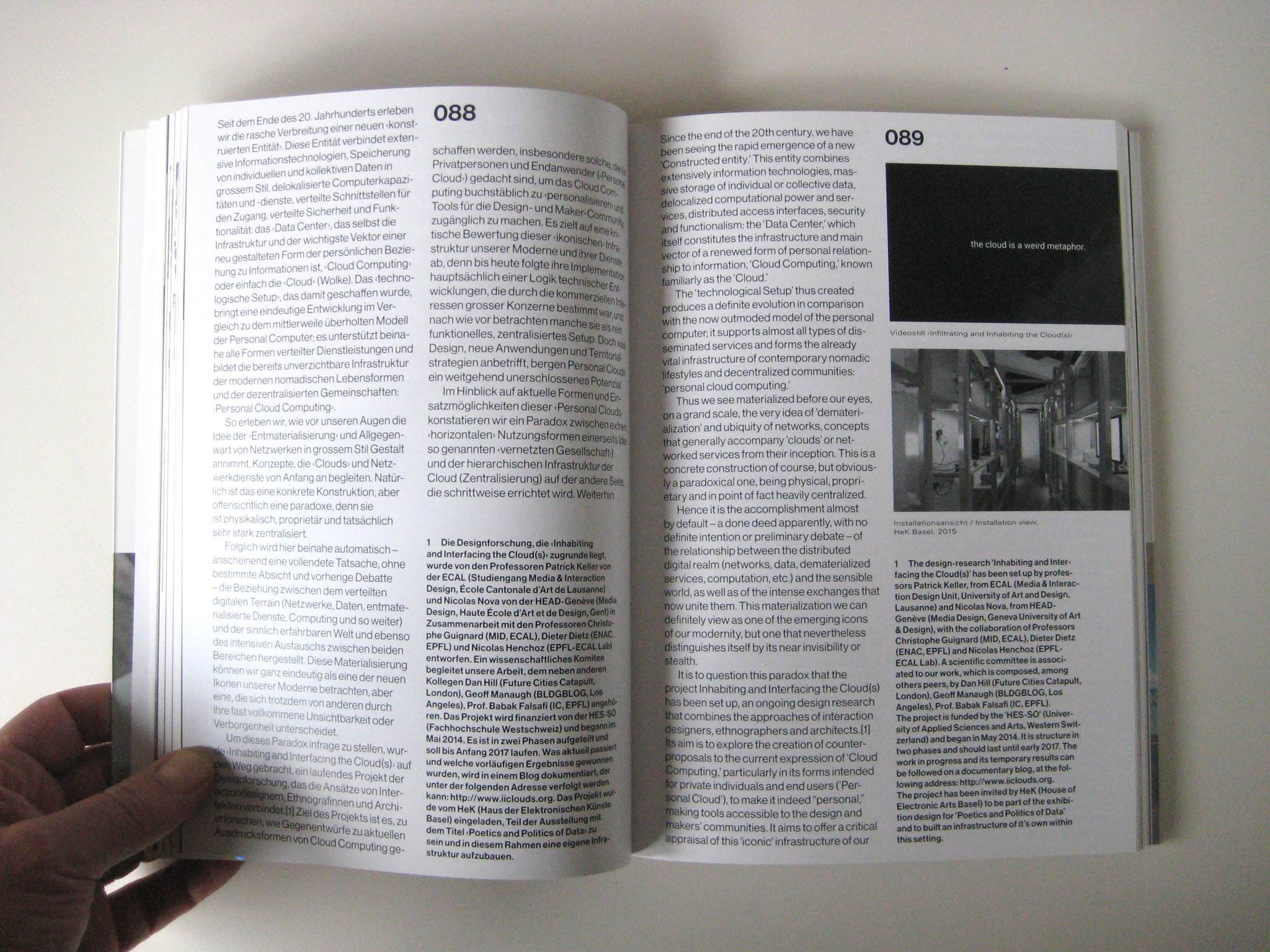

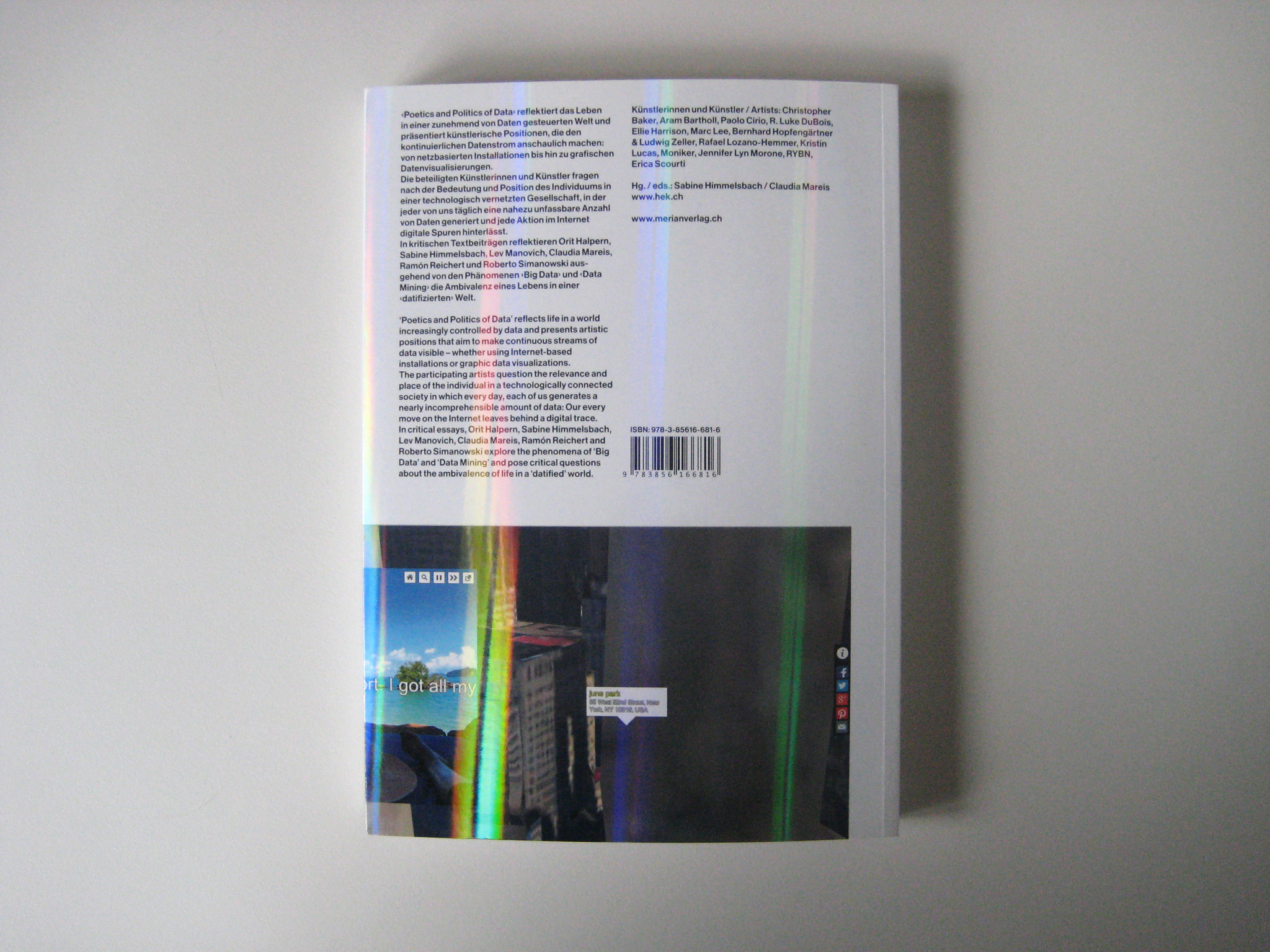

Poetics and Politics of Data (ed. S. Himmelsbach), HEK (Basel, 2015) | #data #clouds #society

Note: a book as a follow up of the exhibition for which fabric | ch designed the scenography last May at the Haus der elektronische Künste in Basel (project White Oblique, downloadable pdf on our website). I was implicated in a double way in the exhibition due to the fact that the content of the design research I'm jointly leading with Nicolas Nova for ECAL and HEAD, Inhabiting and Interfacing the Cloud(s), was also exhibited. I have the pleasure to publish a text in the book about the state and objectives of the ongoing research as well.

Via iiclouds.org

-----

Note: we’re pleased to see that the publication related to the exhibition and symposium Poetics & Politics of Data, curated by Sabine Himmelsbach at the H3K in Basel, has been released later this summer. The publication, with the same title as the exhibition, was first distributed in the context of the conference Data Traces. Big Data in the Context of Culture and Society that also took place at H3K on the 3rd andf 4th of July.

The book contains texts by Nicolas Nova (Me, My cloud and I) and myself (Inhabiting and Interfacing the Cloud(s). An ongoing Design Research), but also and mainly contributions by speakers of the conference (which include the american theorician Lev Manovitch, curator Sabine Himmelsbach and Prof. researcher from HGK Basel Claudia Mareis) and exhibiting artists (Moniker, Aram Bartholl, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Jennifer Lyn Morone, etc.)

The publication serves both as the catalogue of the exhibition and the conference proceedings. Due to its close relation to our subject of research (the book speaks about data, we’re interested in the infrastructure –both physical and digital– that host them), we’re integrating the book to our list of relevant book. The article A short history of Clouds, by Orit Halpern is obviously of direct signifiance to our work.

It can be ordered directly from H3K website:

Poetics and Politics of Data, 265 pp, ed. Christoph Merian Verlag, Basel, 2015 (29.- chf)

Friday, June 26. 2015

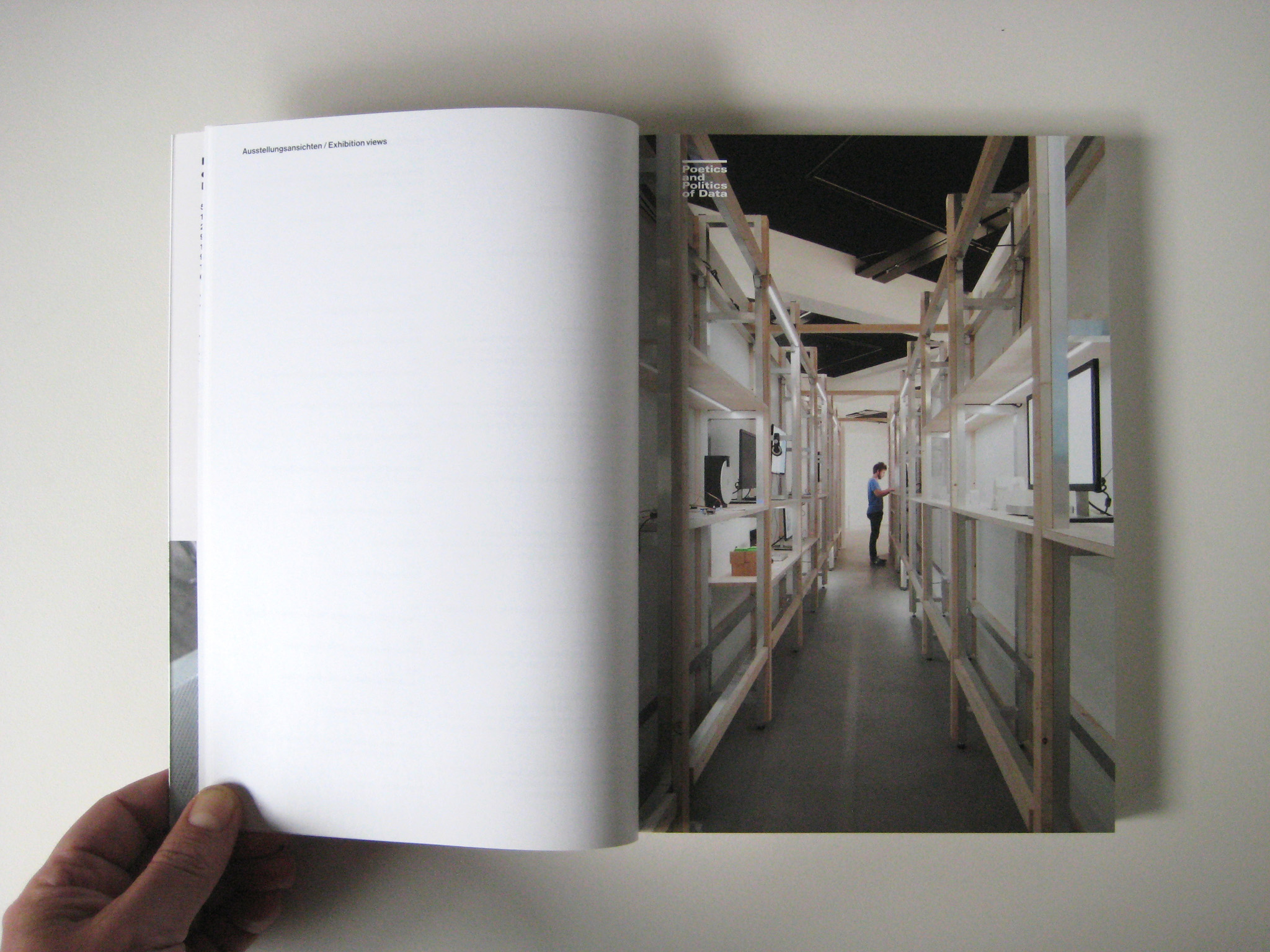

I&IC within Poetics and Politics of Data, exhibition at H3K, scenography. Pictures | #data #research

By fabric | ch

-----

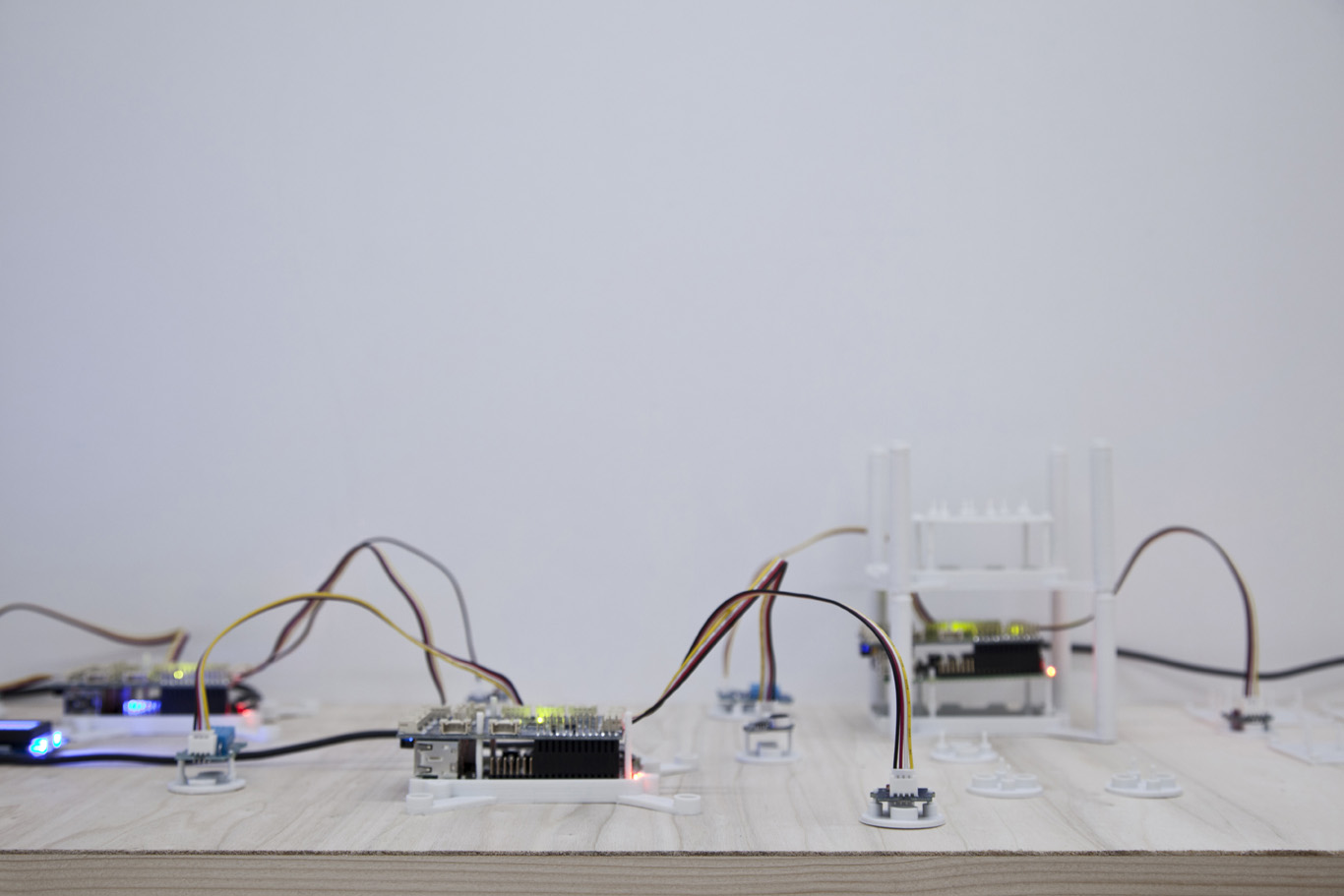

Note: last end of May was the opening of the exhibition Poetics & Politics of Data at the Haus der elektronischen Künste in Basel. This was the occasion to present the temporary results of the design research I'm leading at ECAL/University of Art & Design Lausanne, in collaboration with Nicolas Nova from HEAD - Genève, EPFL and EPFL-ECAL Lab. But for that matter, fabric | ch realized the scenography of the whole exhibition, in particular the "hidden" part hosting the presentation of the design research itself.

The whole spatial display we designed looks like some sort of "heterotopy": an archive and (computer) cabinet of curiosities within the white cube. A little bit like the "behind the scenes" of the exhibition, occupying its center, yet articulating it. It is basically made out of the modular elements that constitutes the "white cube" itself. Just that we maintained the hidden parts of these walls open and visible, widen and turn them in a pathway and an archive.

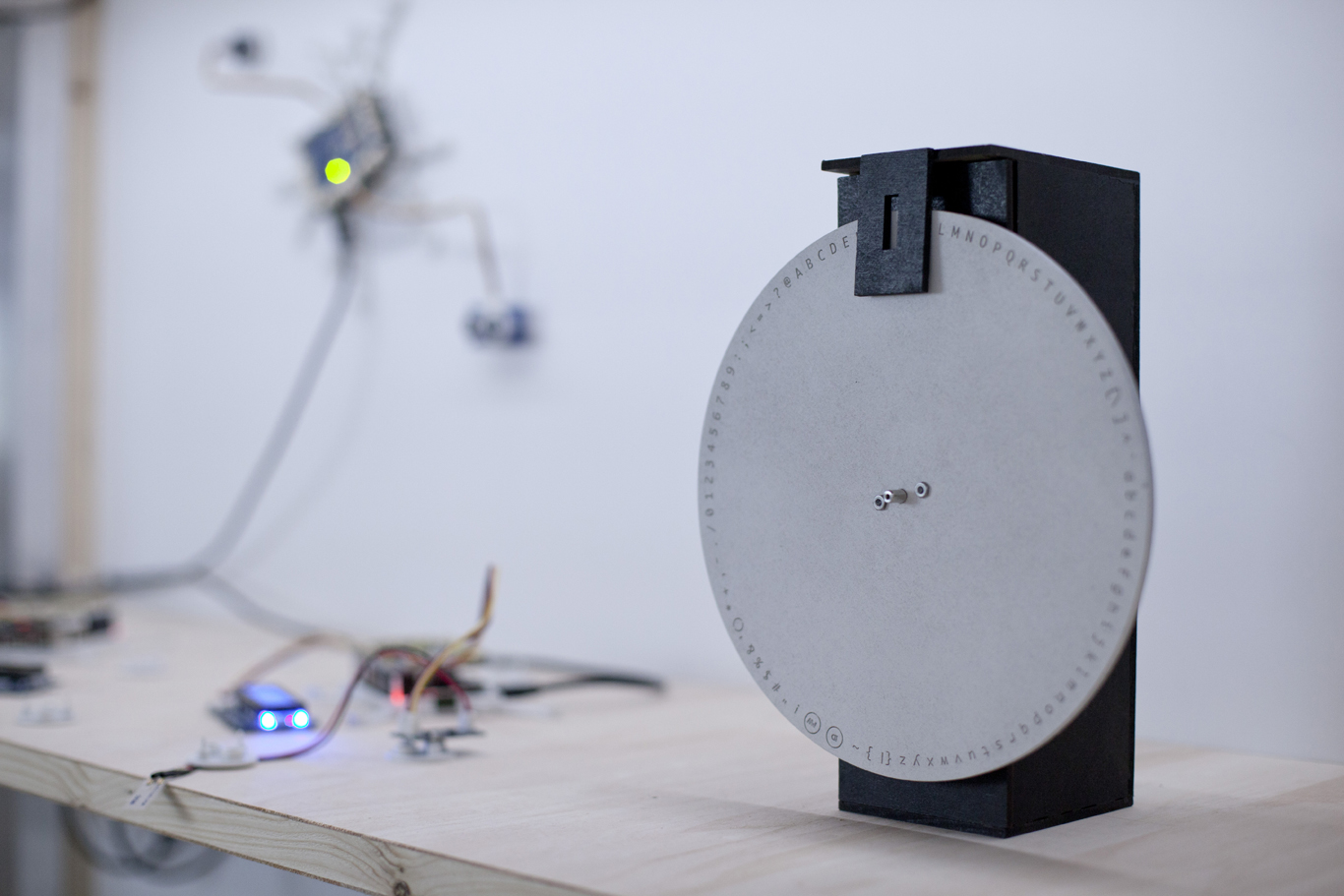

Also present in the space and scenography are different works from fabric | ch: Deterritorialized Daylight is used to drive the lighting of the inner part of the cabinet, a new work Datadroppers --an online data commune, reminiscence of the now dead Pachube-- is used to collect and re-use random data from the exhibition, several Raspberry Pis in their dedicated 3d printed casing are collecting these data (which includes, in addition to the traditional ones more surpising ones like "curiosity", "transgression", etc.) and "dropping" them on the online service. They are then searchable and be used in third parties applications.

The exhibition will still be on view until the end of August in Basel, with works by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Moniker, Aram Bartholl, Jennifer Lyn Morone, Rybn and several others.

Pictures by David Colombini and Marco Frauchiger

-

Intro text to the exhibition and credits:

Inhabiting & Interfacing the Cloud(s) is an ongoing design research about Cloud Computing. It explores the creation of counter-proposals to the current expression of this technological arrangement, particularly in its forms intended for private individuals and end users (Personal Cloud). Through its fully documented cross-disciplinary approach that connects the works of interaction designers, architects and ethnographers, this research project aims at producing alternative yet concrete models resulting from a more decentralized and citizen-oriented approach.

Halfway through the exploration process, the current status of the work is presented in the form of a (computer) cabinet (of curiosities).

Project leaders: Patrick Keller (ECAL), Nicolas Nova (HEAD)

Tutors: Christophe Guignard (ECAL), Dieter Dietz, Caroline Dionne, Manon Fantini, Thomas Favre-Bulle & Rudi Nieveen (EPFL), Nicolas Henchoz (EPFL-ECAL Lab)

Assistants: Lucien Langton (ECAL), Charles Chalas (HEAD), David Colombini

Partners: James Auger, Christian Babski, Stéphane Carion, Matthew Plummer-Fernandez

Students (ECAL): Anne-Sophie Bazard, Benjamin Botros, Caroline Buttet, Guillaume Cerdeira, Romain Cazier, Maxime Castelli, Mylène Dreyer, Bastien Girshig, Martin Hertig, Jonas Lacôte, Alexia Léchot, Nicolas Nahornyj, Pierre-Xavier Puissant

Students (HEAD): Sarah Bourquin, Hind Chamas, Marianne Czwodjdrak, Patrick Donaldson, Alexandra Gavrilova, Félicien Goguey, Eunni Sun Lee, Vanesa Lorenzo, Etienne Ndiaye, Mélissa Pisler, Camille Rattoni, Léa Thévenot, Saskia Vellas

Students (EPFL): Anne-Charlotte Astrup, Francesco Battaini, Tanguy Dyer, Delphine Passaquay

Scenography: fabric | ch

ECAL director: Alexis Georgacopoulos

HEAD – Genève director: Jean-Pierre Greff

ECAL/University of Art & Design Lausanne, HEAD – Genève, EPFL-ECAL Lab, HES-SO

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.

Quicksearch

Categories

Calendar

|

|

April '24 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

.jpg)