Wednesday, March 12. 2025

Summoning the Ghosts of Modernity at MAMM (Medellin) | #exhibition #digital #algorithmic #matter #nonmatter

Note: fabric | ch is part of the exhibition Summoning the Ghosts of Modernity at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellin (MAMM), in Colombia.

The show constitutes a continuation of Beyond Matter that took place at the ZKM in 2022/23, and is curated by Lívia Nolasco-Rószás and Esteban Guttiérez Jiménez.

The exhibition will be open between the 13th of March and 15th of June 2025.

-----

By fabric | ch

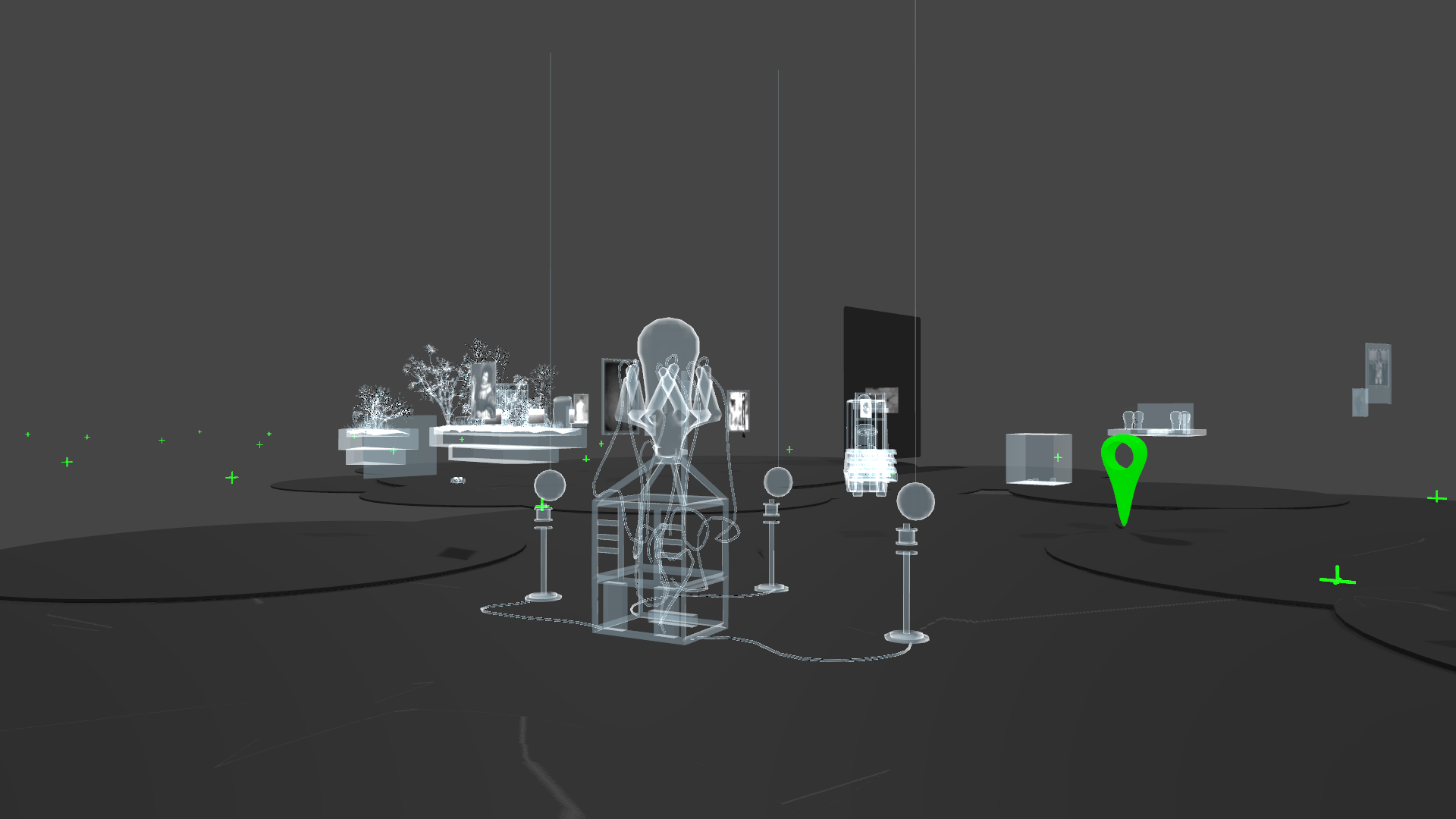

Atomized (re-)Staging (2022), by fabric | ch. Exhibited during Summing the Ghosts of Modernity at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellin (MAMM). March 13 to June 15 2025.

More pictures of the exhibtion on Pixelfed.

Tuesday, February 27. 2024

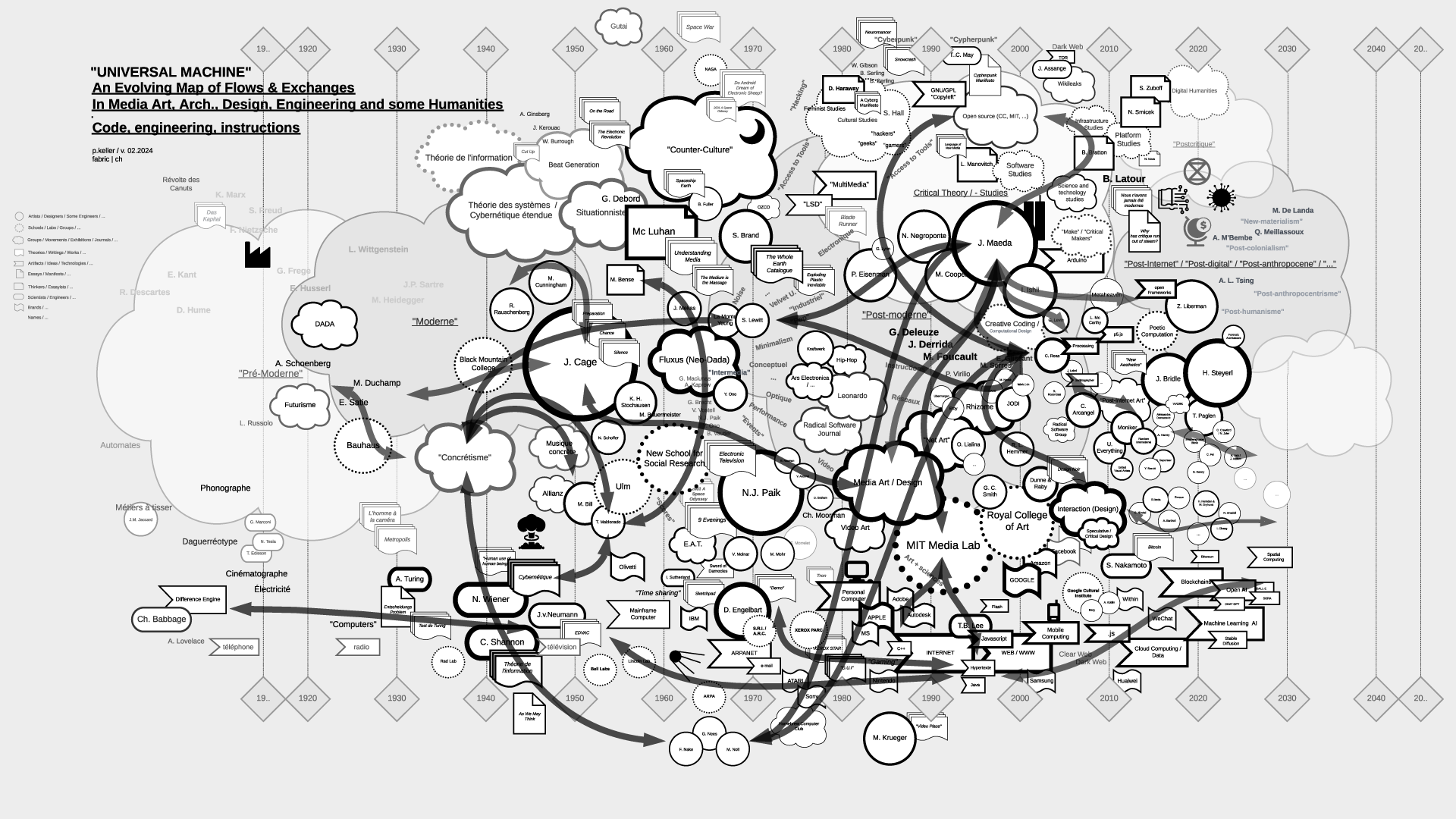

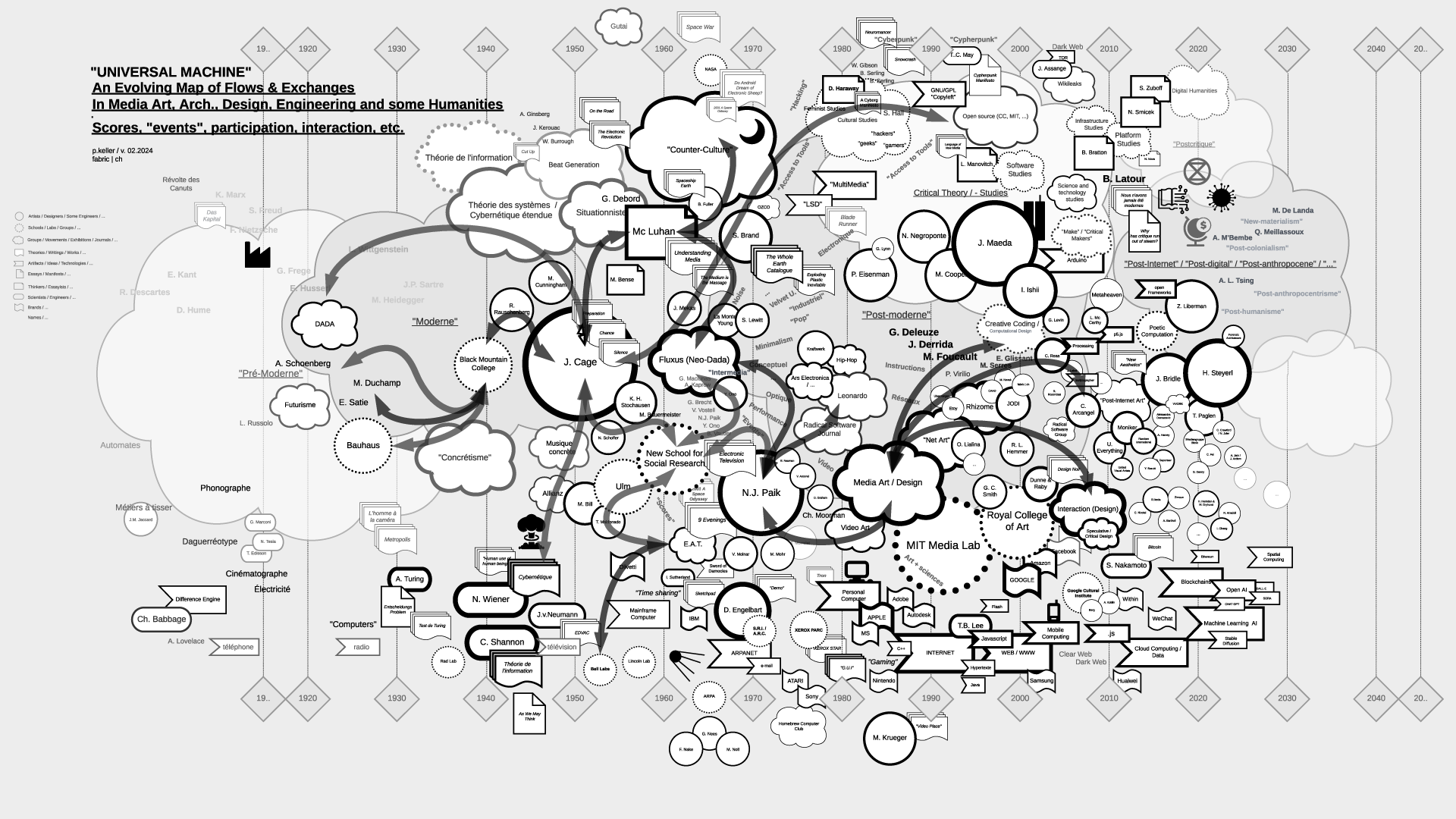

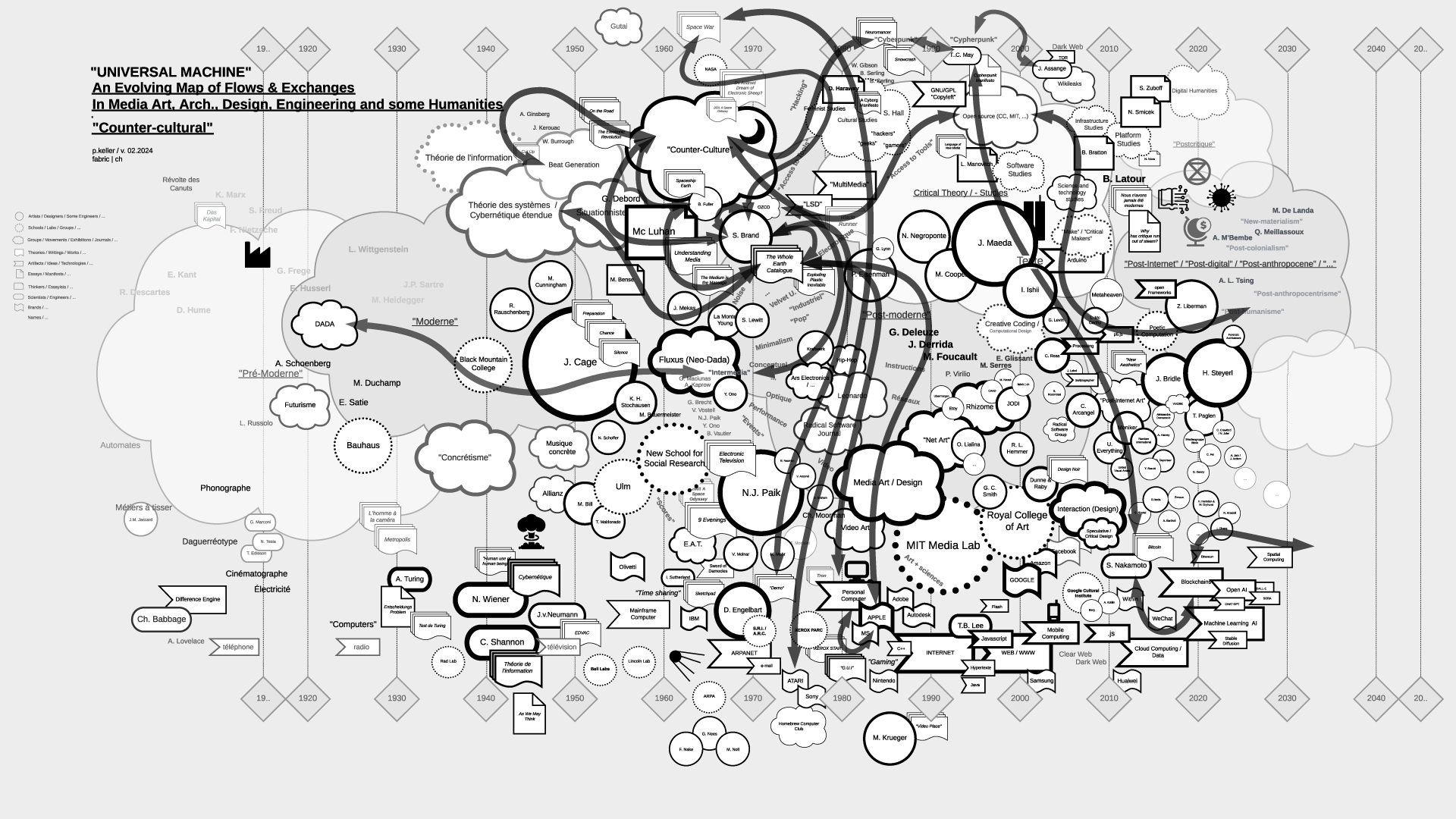

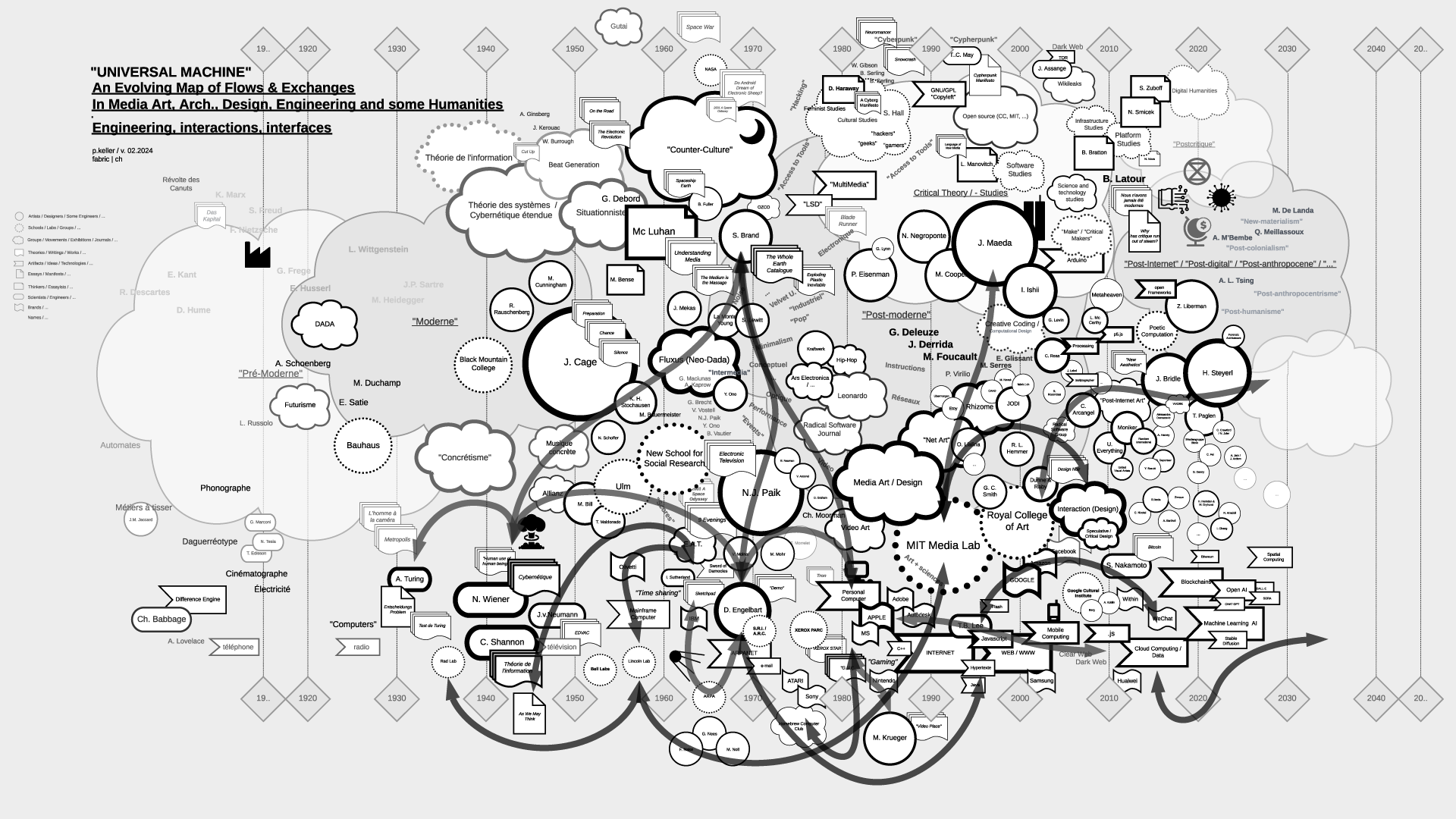

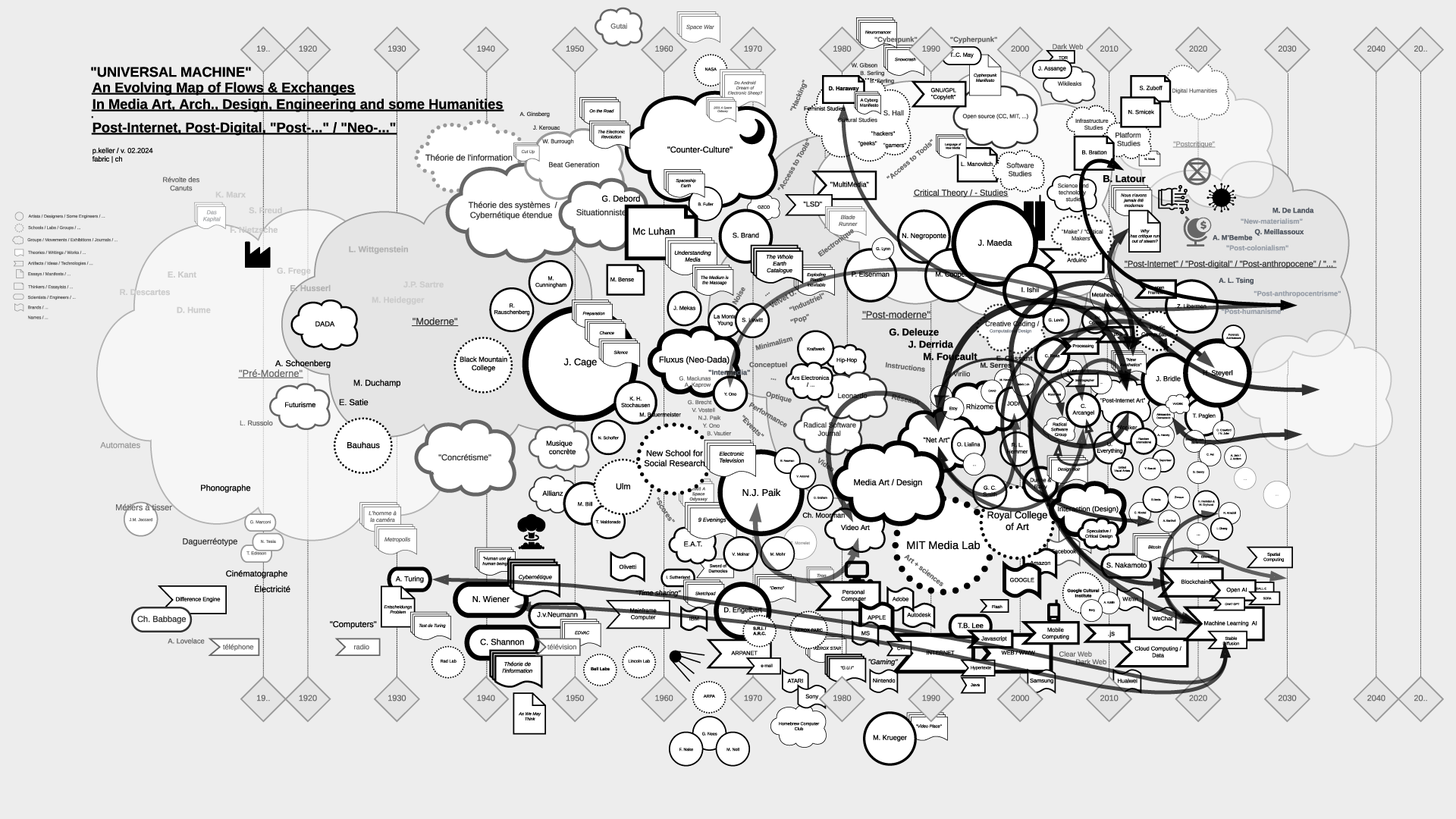

"Universal Machine": historical graphs on the relations and fluxes between art, architecture, design, and technology (19.. - 20..) | #art&sciences #history #graphs

Note (03.2024): The contents of the files (maps) have been updated as of 02.2024.

-

Note (07.2021): As part of my teaching at ECAL / University of Art and Design Lausanne (HES-SO), I've delved into the historical ties between art and science. This ongoing exploration focuses on the connection between creative processes in art, architecture, and design, and the information sciences, particularly the computer, also known as the "Universal Machine" as coined by A. Turing. This informs the title of the graphs below and this post.

Through my work at fabric | ch, and previously as an assistant at EPFL followed by a professorship at ECAL, to experience first hand some of these massive transformations in society and culture.

Thus, in my theory courses, I've aimed to create "maps" that aid in comprehending, visualizing, and elucidating the flux and timelines of interactions among individuals, artifacts, and disciplines. These maps, imperfect and constrained by size, are continuously evolving and open to interpretation beyond my own. I regularly update them as part of the process.

Yet, in the absence of a comprehensive written, visual, or sensitive history of these techno-cultural phenomena as a whole, these maps serve as valuable approximation tools for grasping the flows and exchanges that either unite or divide them. They offer a starting point for constructing personal knowledge and delving deeper into these subjects.

This is precisely why, despite their inherent fuzziness - or perhaps because of it - I choose to share them on this blog (fabric | rblg), in an informal manner. It's an invitation for other artists, designers, researchers, teachers, students, and so forth, to begin building upon them, to depict different flows, to develop pre-existing or subsequent ideas, or even more intriguingly, to diverge from them. If such advancements occur, I'm keen on featuring them on this platform. Feel free to reach out for suggestions, comments, or to share new developments.

...

It's worth mentioning that the maps are structured horizontally along a linear timeline, spanning from the late 18th century to the mid-21st century, predominantly focusing on the industrial period. Vertically, they are organized around disciplines, with the bottom representing engineering, the middle encompassing art and design, and the top relating to humanities, social events, or movements.

Certainly, one might question this linear timeline, echoing the sentiments of writer B. Latour. What about considering a spiral timeline, for instance? Such a representation would still depict both the past and the future, while also illustrating the historical proximities of topics, connecting past centuries and subjects with our contemporary context in a circular manner. However, for the time being, and while recognizing its limitations, I adhere to the simplicity of the linear approach.

Countless narratives can emerge as inherent properties of the graphs, underscoring that they are not their origins but rather products thereof.

...

The selection of topics (code, scores-instructions, countercultural, network-related, interaction, "post-...") currently aligns with the themes of my teaching but is subject to expansion, possibly toward an underlying layer revealing the material conditions that underpinned and facilitated the entire process.

In any case, this could serve as a fruitful starting point for some further readings or perhaps a new "Where's Waldo/Wally" kind of game!

Via fabric | ch

-----

By Patrick Keller

Rem.: By clicking on the thumbnails below you'll get access to HD versions.

"Universal Machine", main map (late 18th to mid 21st centuries):

Flows in the map > "Code":

Flows in the map > "Scores, Partitions, ...":

Flows in the map > "Countercultural, Subcultural, ...":

Flows in the map > "Network Related":

Flows in the map > "Interaction":

Flows in the map > "Post-Internet/Digital, "Post -..." , "Neo -...", ML/AI":

...

To be continued (& completed) ...

Wednesday, November 29. 2023

Architecture & Landscape Award 2023 from Fondation Vaudoise pour la Culture (FVPC) | #award #fabricch #architecture #interaction #research

Note: fabric | ch was honored to receive this year the Award for Architecture and Landscape Culture from the Fondation vaudoise pour la culture (FVPC).

The price distinguishes an actor who is "involved in the design or promotion of built environment and who, through this commitment, contributes to the quality of our natural, [digital] and built environment".

A brief video portait of fabric | ch was produced on this occasion by director Pierre-Yves Borgeaud, as well as a small publication by Art Director Emmanuel Crivelli and photographic portraits by Matthieu Croizier (see below).

We'd like to thank the foundation and its jury for awarding our studio in 2023!

-----

By fabric | ch

---

---

---

... and for the record,

our bit of the award ceremony!

Thursday, August 03. 2023

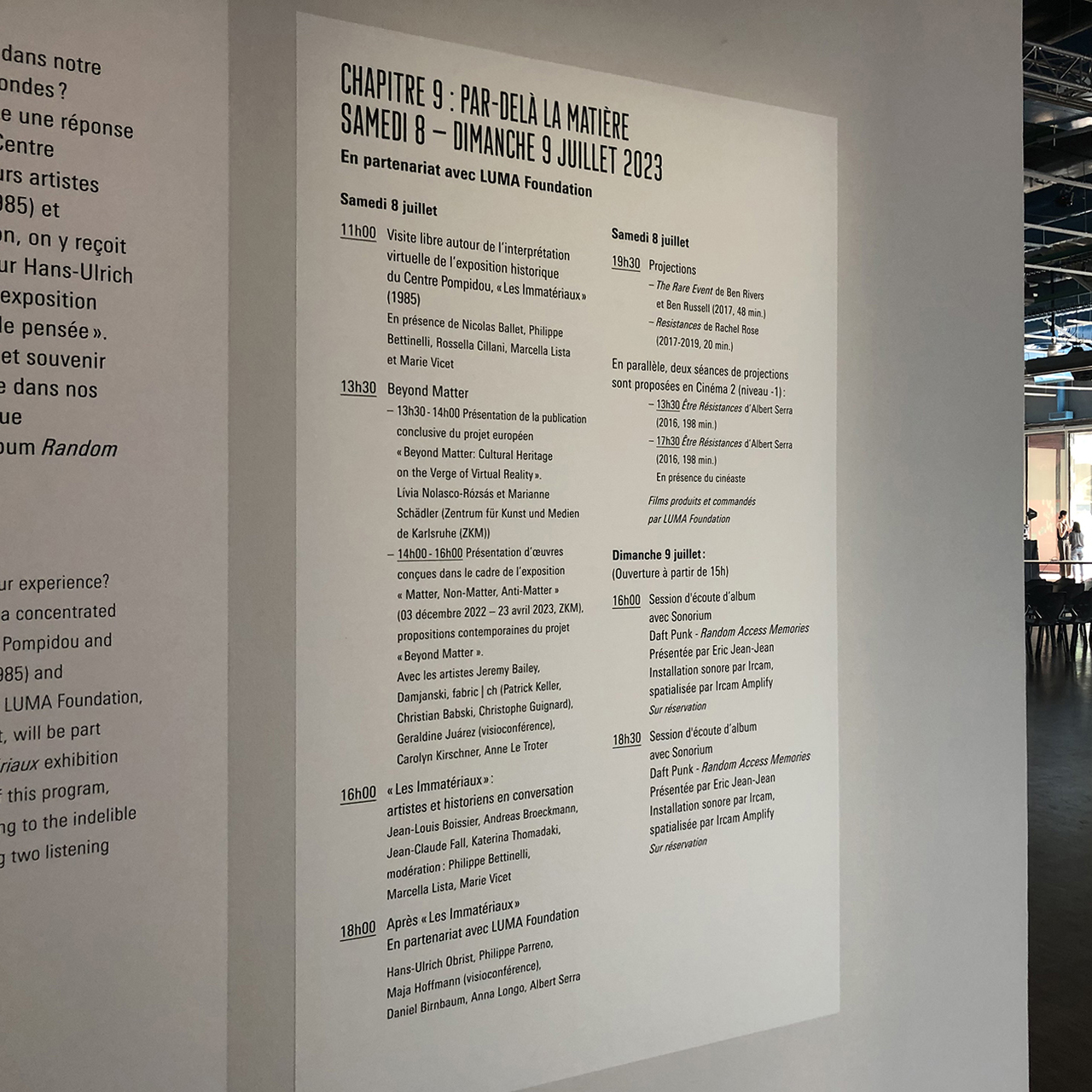

Moviment exhibition at the Centre Pompidou – fabric | ch during Chapter "Par-delà la matière" | #matter #non-matter #automated #exhibition #fabricch

Note: Early last July, fabric | ch took part in the Moviment exhibition-festival at Centre Pompidou, in Paris.

Organized in 10 chapters (Red thread; The bedroom, the house, the city; In the spotlight; Aloud, Here and elsewhere, Other-worldly; Of gesture and time; To the max; Beyond matter; The grand finale!), this was the occasion – following the words of the curators – to "reactivate the essence of the Centre Pompidou ideals: to assemble all the different ways of encountering creativity, understanding it, participating in it; to be a monument in motion, a "moviment."

It was truly a success, with outstanding guests and a very interesting hybrid museum format, somewhere in-between exhibition and performance, talks and workshops.

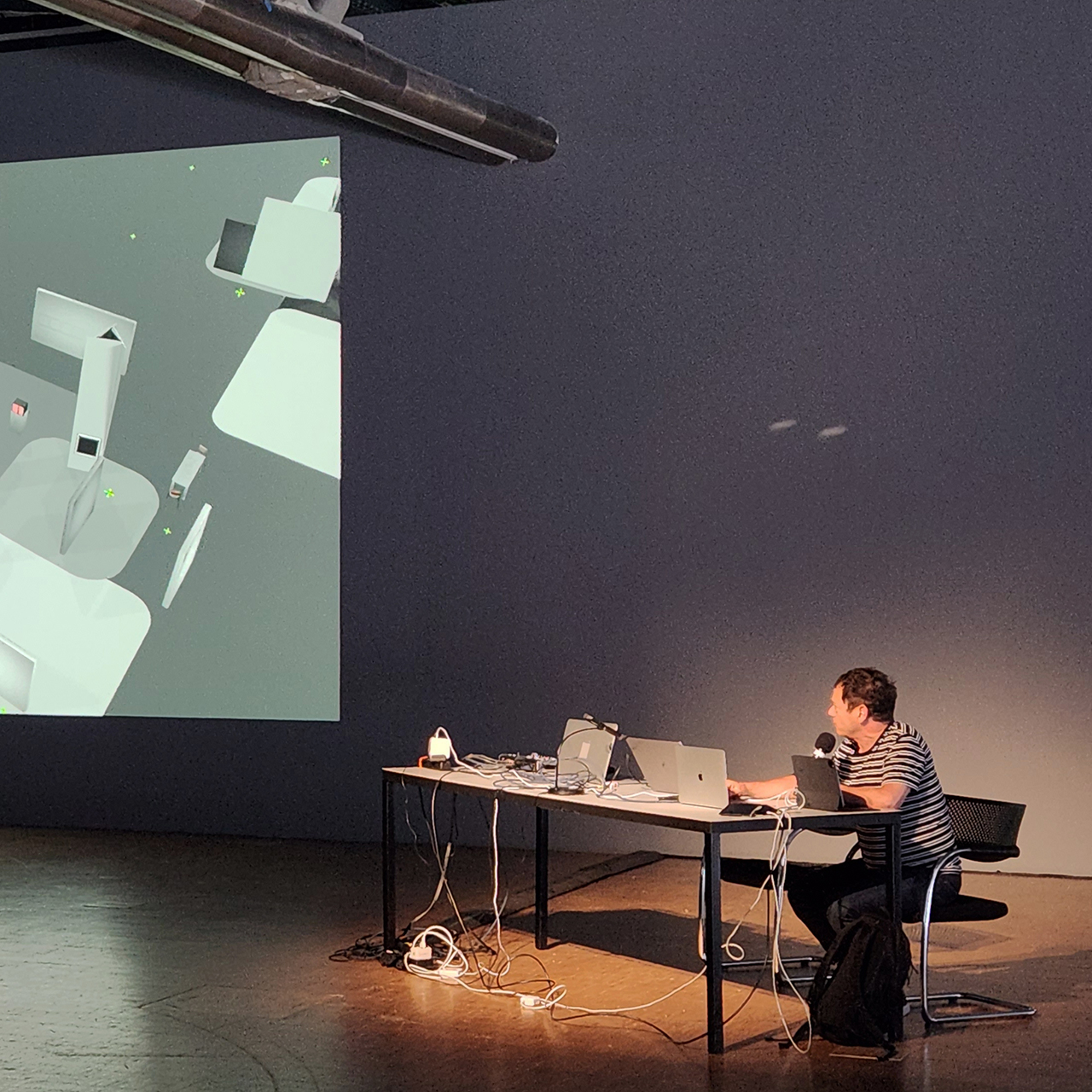

In this context and during "Chapitre 9: Par-delà la matière" curated by Marcella Lista & Philippe Bettinelli, fabric | ch presented recent works about digital exhibitions.

-----

By fabric | ch

![]()

A few pictures from Moviment / Chapter 9:

(with fabric | ch, M. Lista & Les Immatériaux, M. Klonaris & K. Thomadaki, H.U. Obrist – "Résistances" project with LUMA Foundation and P. Parreno, J.-L. Boissier - Electra / Pictures by C. Babski & H. Veronese)

Via Centre Pompidou

-----

Beyond Matter / Par-delà la matière

Moviment, chapter 9

Sat 8 – Sun 9 July 2023

Combining technology and memory, the penultimate chapter of Moviment looks back at two major cultural events in the world of art and music, and the ways in which they can be perpetuated, revived or experienced beyond their materiality and topicality.

In partnership with LUMA Foundation

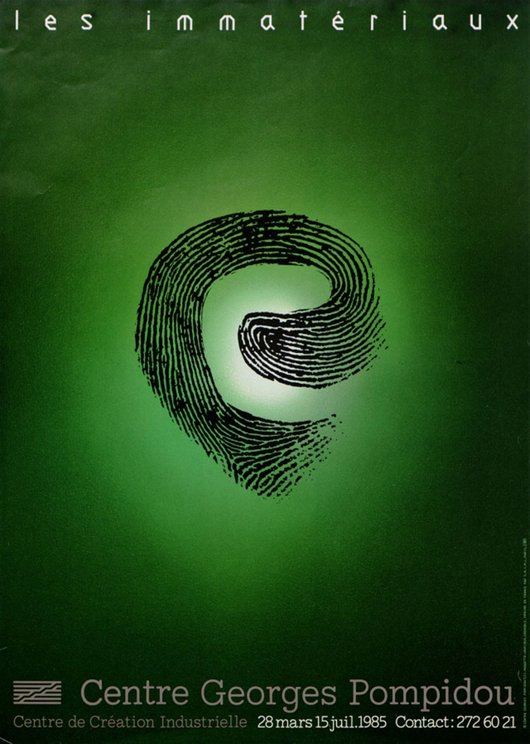

Affiche de l’exposition "Les Immatériaux", 1985 – © Centre Pompidou. Conception graphique : Grafibus.

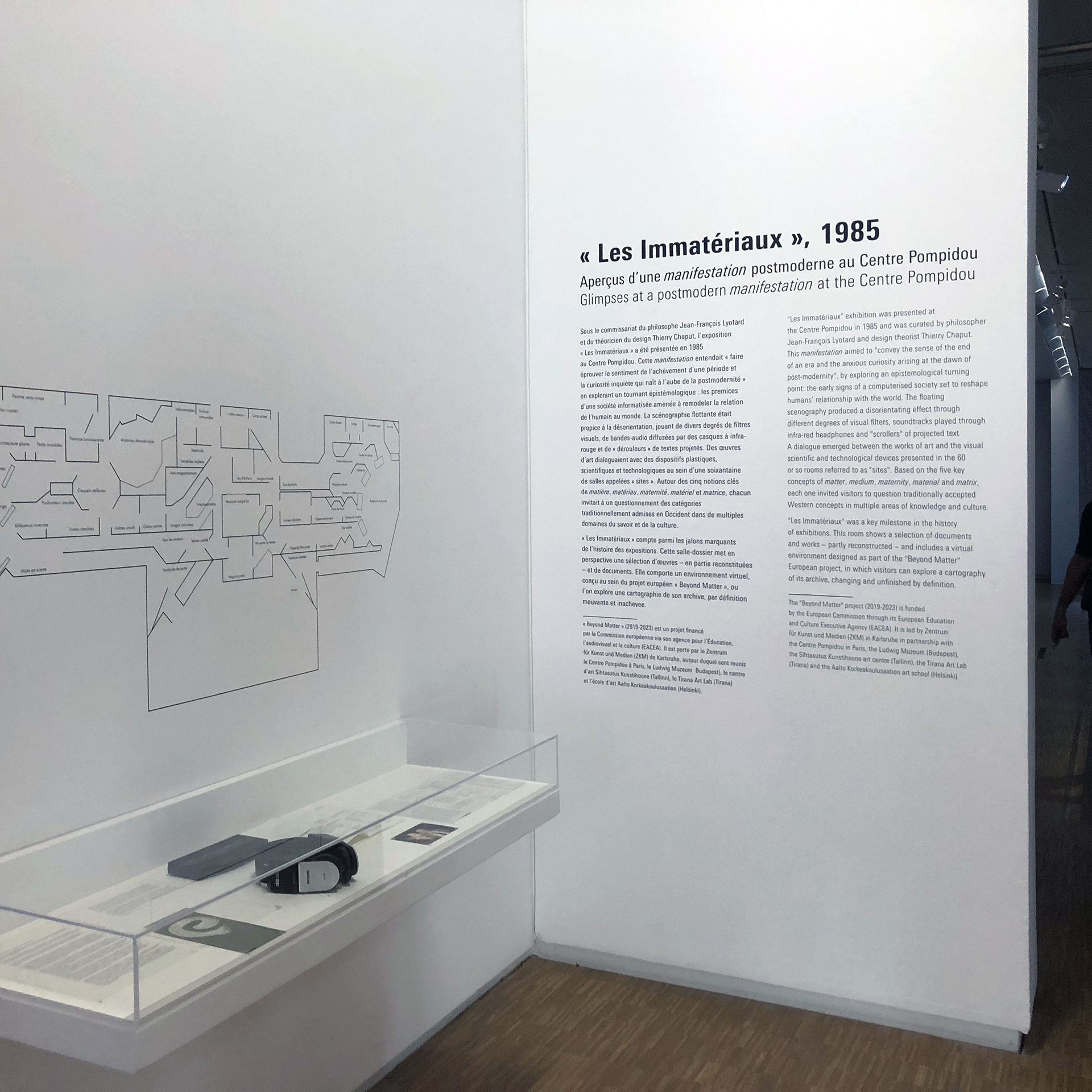

Retour sur « Les Immatériaux »

Arts plastiques, Nouveaux médias Exposition, rencontres

Organisé par les commissaires Jean-François Lyotard et Thierry Chaput en 1985, « Les Immatériaux » était un essai aux fondements philosophiques adoptant l’exposition comme média ou interface. En faisant dialoguer œuvres d’art, technologies et documents scientifiques, les commissaires interrogeaient la condition humaine à l’ère des nouvelles technologies, dans différents domaines de la vie physique et psychique. La scénographie, particulièrement novatrice, privilégiait la désorientation, la stimulation de tous les sens et l’interactivité. Les visiteurs, dont le parcours n’était pas contraint mais « induit » par des écrans suspendus à l’opacité variable, étaient munis d’un casque diffusant une bande sonore variant au gré de leur déambulation dans la soixantaine de sites et les vingt-six zones audio de l’exposition.

Cette exposition historique a récemment fait l’objet d’une reconstitution virtuelle dans le cadre du projet de recherche « Beyond Matter ».

Exposition en continu, samedi 8 juillet 2023

« Beyond Matter »

Financé par la Commission européenne, le projet de recherche « Beyond Matter: Cultural Heritage on the Verge of Virtual Reality » vise à développer des outils technologiques et théoriques pour la reconstitution virtuelle d’expositions historiques et la documentation d’expositions en cours. Les recherches menées dans le cadre de ce projet ont notamment porté sur deux expositions pionnières : « Iconoclash » (4 mai–1er septembre 2002, ZKM) et « Les Immatériaux » (28 mars–15 juillet 1985, Centre Pompidou).

Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás et Marianne Schädler du Zentrum für Kunst und Medien de Karlsruhe (ZKM) présenteront la publication conclusive du projet européen.

Les artistes Jeremy Bailey, Damjanski, fabric | ch (Patrick Keller, Christian Babski, Christophe Guignard), Geraldine Juárez (en visioconférence), Carolyn Kirschner et Anne Le Troter présenteront ensuite les œuvres qu’ils et elles ont pu concevoir dans le cadre de l’exposition « Matter, Non-Matter, Anti-Matter » (3 décembre 2022–23 avril 2023, ZKM), restituant une partie des résultats du projet « Beyond Matter ».

Samedi 8 juillet 2023, 13h30–16h

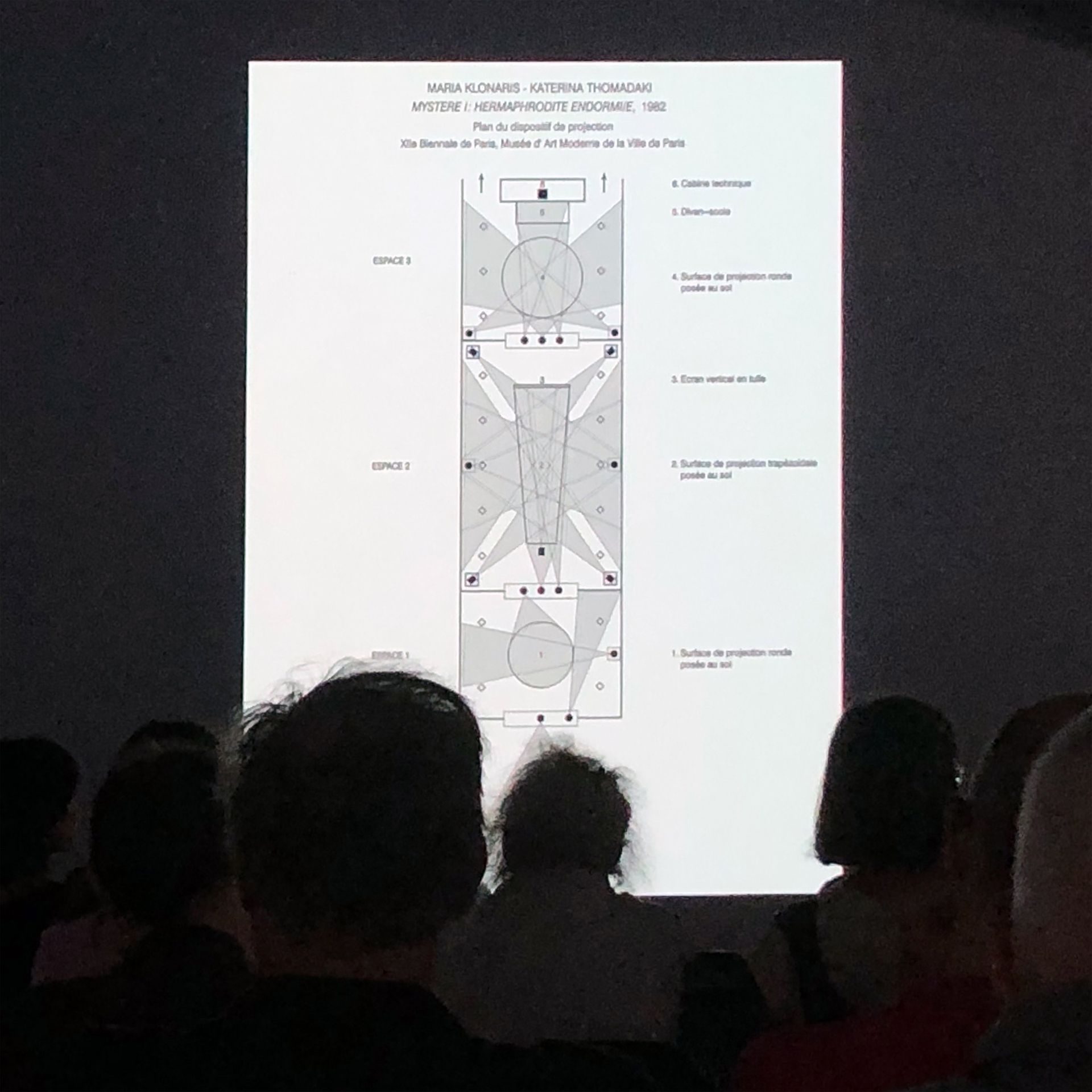

« Les Immatériaux » : Artistes et historiens en conversation

Le chercheur Andreas Broeckmann, ainsi que les artistes Katerina Thomadaki, Jean-Louis Boissier et Jean-Claude Fall reviennent sur « Les Immatériaux », exposition pionnière à laquelle ils ont participé.

Séance modérée par Marcella Lista, Philippe Bettinelli et Marie Vicet.

Samedi 8 juillet 2023, 16h-18h

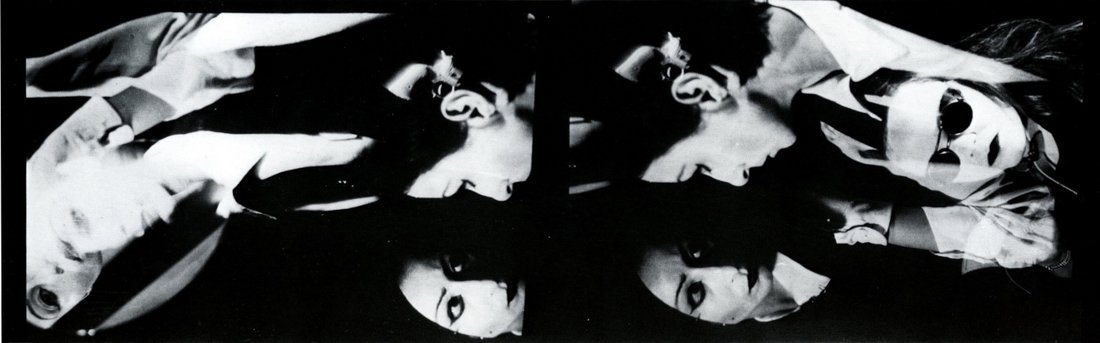

Maria Klonaris, Katerina Thomadaki, "Orlando-Hermaphrodite II", 1985, photographies noir et blanc sur panneau.

Courtesy Katerina Thomadaki.

Après « Les Immatériaux »

Projet porté par le curateur Hans Ulrich Obrist et l’artiste Philippe Parreno avec le soutien de LUMA Foundation, « Résistances » fait écho à l’exposition « Les Immatériaux » imaginée par Jean-François Lyotard. Resté inachevé, ce projet se trouve tout à la fois continué et réimaginé à travers des rencontres et la production de « films de pensée ».

Samedi 8 juillet 2023, 18h–19h30

La conversation se déroulera en français et en anglais, suivie d’une projection des « films de pensée ».

Films de pensée :

Produits et commandés par LUMA Foundation

Courtesy Maja Hoffmann / Luma Foundation Collection

- Être Résistances d’Albert Serra (2016, 198 min.)

« Être Résistances est un film qui résiste à en être un, c'est-à-dire qu'il résiste à la conscience et au langage cinématographique. C'est un film qui traite de théorie, de corps, de bruits, de discours, d'images, de jeu et d'ironie. C'est un film inspiré par son propre sujet invisible : l'exposition inexistante de Lyotard qui devrait résister à la communication. Le film est finalement cette exposition devenue réalité, mais comme un mirage et comme une illusion. » Albert Serra.

Séances, samedi 8 juillet 2023, à 13h30 et 17h30

Introduction par Albert Serra à 17h30

Cinéma 2, niveau –1

- The Rare Event de Ben Rivers et Ben Russell (2017, 48 min.) sous-titrage en français

Tourné dans un studio d'enregistrement parisien au plancher de bois grinçant, lors d'un « forum des idées » inaugural de trois jours consacré aux multiples possibilités de la Résistance – titre de l'exposition de Jean-François Lyotard qui devait faire suite à son exposition « Les Immatériaux » de 1985 –, les collaborateurs occasionnels Ben Rivers et Ben Russell (avec la contribution de l'artiste américain Peter Burr) ont produit ce qui apparaît d'abord comme un document structuraliste d'une discussion philosophique performée qui se transforme lentement en The Rare Event, un portail qui réunit toutes les dimensions en une seule.

- Resistances de Rachel Rose (2017-2019, 20 min.) VO en anglais

Ce court-métrage documente la deuxième rencontre sur les « Résistances » qui a eu lieu en février 2017 à New York, offrant ainsi un aperçu des conversations et des réflexions qui se sont déployées au cours de ce « forum des idées » organisé par Maja Hoffmann. Parmi les intervenants figurent Tyrone Hayes, Isabelle Thomas Fogiel, Reza Negarestani, Ariana Reines, Fred Moten, et de nombreux autres invités.

Projection, samedi 8 juillet 2023, à 19h30

Plan fixe du film "THE RARE EVENT" de Ben Rivers et Ben Russell.

Courtesy Maja Hoffmann / Luma Foundation Collection.

En lien avec la présentation temporaire au Musée, niveau 4, Espace de consultation des collections vidéos, films, sons et œuvres numériques :

« Les Immatériaux » (1985). Aperçus d'une manifestation postmoderne au Centre Pompidou. Du 5 juillet au 30 octobre 2023

Couverture de l'album Daft Punk, "Random Access Memories" © Zaina

Daft Punk, Random Access Memories

Session d’écoute avec Sonorium

Musique Session d'écoute, rencontre

5 Grammy Awards et un triomphe instantané, un tube planétaire ("Get Lucky"), une production incroyable de précision et des collaborations prestigieuses (Pharrell Williams, Julian Casablancas, Panda Bear, Giorgio Moroder…), Random Access Memories, le dernier album de Daft Punk, a marqué les esprits et installé le duo comme une figure majeure de la pop contemporaine.

À l'occasion de l'édition 10e anniversaire de l'album culte le 12 mai dernier, le Centre Pompidou et Sonorium vous invitent à une session d'écoute de l'album en intégralité, dans des conditions exceptionnelles grâce à une installation sonore immersive réalisée par l’Ircam et une nouvelle technologie immersive développée par sa filiale Ircam Amplify.

Dimanche 9 juillet 2023 – gratuit sur réservation

Sessions précédées d'une introduction par Éric Jean-Jean et suivies d'une discussion avec le public

Day-by-day program

Saturday, 8 July 2023

|

Continuous 11am-1pm |

Performance Christian Falsnaes, First (2016) |

|

Exhibition Reconstitution virtuelle de l'exposition « Les Immatériaux » |

|

| 1:30pm-2pm |

Meeting « Beyond Matter » Présentation de la publication conclusive du projet européen « Beyond Matter: Cultural Heritage on the Verge of Virtual Reality » |

| 1:30pm-5pm |

Screening Après « Les Immatériaux » : Films de pensée Être Résistances d’Albert Serra (2016, 198 min.) |

| 2pm-4pm |

Meeting « Beyond Matter » Présentation d'œuvres conçues dans le cadre de l'exposition « Matter, Non-matter, Anti-Matter » Avec les artistes Jeremy Bailey, Damjanski, fabric | ch (Patrick Keller, Christian Babski, Christophe Guignard), Geraldine Juárez (en visioconférence), Carolyn Kirschner et Anne Le Troter |

| 4pm-6pm |

Meeting « Les Immatériaux » : Artistes et historiens en conversation Avec Andreas Broeckmann, Katerina Thomadaki, Jean-Louis Boissier et Jean-Claude Fall Modérée par Marcella Lista, Philippe Bettinelli et Marie Vicet (Centre Pompidou) |

| 5:30pm-9pm |

Screening Après « Les Immatériaux » : Films de pensée Être Résistances d’Albert Serra (2016, 198 min.) En présence du cinéaste |

| 6pm-7:30pm |

Meeting Après « Les Immatériaux » : Rencontre en partenariat avec LUMA Foundation Avec Hans Ulrich Obrist, Philippe Parreno, Daniel Birnbaum, Anna Longo, Maja Hoffmann (en visioconférence) et Albert Serra |

| 7:30pm-9pm |

>Screening Après « Les Immatériaux » : Films de pensée

|

Sunday, 9 July 2023

|

Reconstitution virtuelle de l'exposition « Les Immatériaux »

|

Closing of the gallery 3 at the beginning of the day |

|

Continuous 3pm-9pm |

Performance Christian Falsnaes, First (2016) |

|

4pm-6pm 6:30pm-8:30pm |

Listening session, meeting Daft Punk, Random Access memories Introduction par Éric Jean-Jean Session d'écoute Discussion avec le public |

Guests

|

Hans Ulrich ObristVisual arts

|

Philippe ParrenoVisual arts

|

|

Jean-Louis BoissierNew media

|

Katerina ThomadakiNew media

|

Also in the presence of:

Jeremy Bailey, Daniel Birnbaum, Andreas Broeckmann, Damjanski, fabric | ch (Patrick Keller, Christian Babski, Christophe Guignard), Jean-Claude Fall, Maja Hoffmann, Éric Jean-Jean, Geraldine Juárez, Carolyn Kirschner, Anna Longo, Marianne Schädler, Albert Serra, Anne Le Troter.

Monday, March 13. 2023

Atomized (re-)Staging short video documentation | #fabricch #digital #hybrid #exhibition

Note: a brief video documentation about one of fabric | ch's latest project – Atomized (Re)Staging – that was exhibited at ZKM during Matter. Non-Matter. Anti-Matter.

The exhibition was curated by Lívía Nolasco-Roszás and Felix Koberstein and took place ibn the context of the European research project Beyond Matter.

![]()

-----

Wednesday, November 30. 2022

Past exhibitions as Digital Experiences @ZKM, fabric | ch | #digital #exhibition #experimentation

Note:

The exhibition related to the project and European research Beyond Matter - Past Exhibitions as Digital Experiences will open next week at ZKM, with the digital versions (or should I rather say "versioning"?) of two past and renowned exhibitions: Iconoclash, at ZKM in 2002 (with Bruno Latour among the multiple curators) and Les Immateriaux, at Beaubourg in 1985 (in this case with Jean-François Lyotard, not so long after the release of his Postmodern Condition). An unusual combination from two different times and perspectives.

The title of the exhibition will be Matter. Non-Matter. Anti-Matter, with an amazing contemporary and historic lineup of works and artists, as well as documentation material from both past shows.

Working with digitized variants of iconic artworks from these past exhibitions (digitization work under the supervision of Matthias Heckel), fabric | ch has been invited by Livia Nolasco-Roszas, ZKM curator and head of the research, to present its own digital take in the form of a combination on these two historic shows, and by using the digital models produced by their research team and made available.

The result, a new fabric | ch project entitled Atomized (re-)Staging, will be presented at the ZKM in Karlsruhe from this Saturday on (03.12.2022 - 23.04.2023).

Via ZKM

-----

Opening: Matter. Non-Matter. Anti-Matter.

© ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, Visual: AKU Collective / Mirjam Reili

Past exhibitions as Digital Experiences

Fri, December 02, 2022 7 pm CET, Opening

---

Free entry

---

When past exhibitions come to life digitally, the past becomes a virtual experience. What this novel experience can look like in concrete terms is shown by the exhibition »Matter. Non-Matter. Anti-Matter«.

As part of the project »Beyond Matter. Cultural Heritage on the Verge of Virtual Reality«, the ZKM | Karlsruhe and the Centre Pompidou, Paris, use the case studies »Les Immatériaux« (Centre Pompidou, 1985) and »Iconoclash« (ZKM | Karlsruhe, 2002) to investigate the possibility of reviving exhibitions through experiential methods of digital and spatial modeling.

The digital model as an interactive presentation of exhibition concepts is a novel approach to exploring exhibition history, curatorial methods, and representation and mediation. The goal is not to create »digital twins«, that is, virtual copies of past assemblages of artifacts and their surrounding architecture, but to provide an independent sensory experience.

On view will be digital models of past exhibitions, artworks and artifacts from those exhibitions, and accompanying contemporary commentary integrated via augmented reality. The exhibition will be accompanied by a conference on virtualizing exhibition histories.

The exhibition will be accompanied by numerous events, such as specialist workshops, webinars, online and offline guided tours, and a conference.

---

Program

7 – 7:30 p.m. Media Theater

Short lectures by

Sybille Krämer, Professor (emer.) at the Free University of Berlin

Siegfried Zielinski, media theorist with a focus on archaeology and variantology of arts and media, curator, author

Moderation: Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás, curator

7:30 – 8:15 p.m. Media Theater

Welcome

Olga Sismanidi, Representative Creative Europe Program of the European Commission (EACEA)

Arne Braun, State Secretary in the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts of Baden-Württemberg

Frank Mentrup, Lord Mayor of the City of Karlsruhe

Peter Weibel, Director of the ZKM | Karlsruhe

Xavier Rey, Director of the Centre Pompidou, Paris

8:15 – 8:30 p.m. Improvisation on the piano

Hymn Controversy by Bardo Henning

8:30 p.m.

Curator guided tour of the exhibition

---

The exhibition will be open from 8 to 10 p.m.

The mint Café is also looking forward to your visit.

---

Matter. Non-Matter. Anti-Matter.

Past Exhibitions as Digital Experiences.

Sat, December 03, 2022 – Sun, April 23, 2023

The EU project »Beyond Matter: Cultural Heritage on the Verge of Virtual Reality« researches ways to reexperience past exhibitions using digital and spatial modeling methods. The exhibition »Matter. Non-Matter. Anti-Matter.« presents the current state of the research project at ZKM | Karlsruhe.

At the core of the event is the digital revival of the iconic exhibitions »Les Immatériaux« of the Centre Pompidou Paris in 1985 and »Iconoclash: Beyond the Image Wars in Science, Religion, and Art« of the ZKM | Karlsruhe in 2002.

Based on the case studies of »Les Immatériaux« (Centre Pompidou, 1985) and »Iconoclash: Beyond the Image Wars in Science, Religion, and Art« (ZKM, 2002), ZKM | Karlsruhe and the Centre Pompidou Paris investigate possibilities of reviving exhibitions through experiential methods of digital and spatial modeling. Central to this is also the question of the particular materiality of the digital.

At the heart of the Paris exhibition »Les Immatériaux« in the mid-1980s was the question of what impact new technologies and materials could have on artistic practice. When philosopher Jean-François Lyotard joined as cocurator, the project's focus eventually shifted to exploring the changes in the postmodern world that were driven by a flood of new technologies.

The exhibition »Iconoclash« at ZKM | Karlsruhe focused on the theme of representation and its multiple forms of expression, as well as the social turbulence it generates. As emphasized by curators Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, the exhibition was not intended to be iconoclastic in its approach, but rather to present a synopsis of scholarly exhibits, documents, and artworks about iconoclasms – a thought experiment that took the form of an exhibition – a so-called »thought exhibition.«

»Matter. Non-Matter. Anti-Matter.« now presents in the 21st century the digital models of the two projects on the Immaterial Display, hardware that has been specially developed for exploring virtual exhibitions. On view are artworks and artifacts from the past exhibitions, as well as contemporary reflections and artworks created or expanded for this exhibition. These include works by Jeremy Bailey, damjanski, fabric|ch, Geraldine Juárez, Carolyn Kirschner, and Anne Le Troter that echo the 3D models of the two landmark exhibitions. They bear witness to the current digitization trend in the production, collection, and presentation of art.

Case studies and examples of the application of digital curatorial reconstruction techniques that were created as part of the Beyond Matter project complement the presentation.

The exhibition »Matter. Non-Matter. Anti-Matter.« is accompanied by an extensive program of events: A webinar series aimed at museum professionals and cultural practitioners will present examples of work in digital or hybrid museums; two workshops, coorganized with Andreas Broeckmann from Leuphana University Lüneburg, will focus on interdisciplinary curating and methods for researching historical exhibitions; workshops on »Performance-Oriented Design Methods for Audience Studies and Exhibition Evaluation« (PORe) will be held by Lily Díaz-Kommonen and Cvijeta Miljak from Aalto University.

After the exhibition ends at the ZKM, a new edition of »Matter. Non-Matter. Anti-Matter.« will be on view at the Centre Pompidou in Paris from May to July 2023.

>>>

Artists

Josef Albers, Giovanni Anselmo, Arman, Art & Language, Jeremy Bailey, Fiona Banner, DiMoDa featuring Banz & Bowinkel, Christiane Paul, Tamiko Thiel, Ricardo Miranda Zúñiga, Samuel Bianchini, Bio Design Lab (HfG Karlsruhe), Jean-Louis Boissier & Liliane Terrier, John Cage, Jacques-Élie Chabert & Camille Philibert, damjanski, Annet Dekker & Marialaura Ghidini & Gaia Tedone, Marcel Duchamp, fabric | ch, Eric J. Heller, Prof. Dr. Kai-Uwe Hemken (Art Studies Kunsthochschule Kassel / University of Kassel), Joasia Krysa, Leonardo Impett, Eva Cetinić, MetaObjects, Sui, Michel Jaffrennou, Geraldine Juárez, Martin Kippenberger, Carolyn Kirschner, Maria Klonaris & Katerina Thomadaki, Joseph Kosuth, Denis Laborde, Mark Lewis & Laura Mulvey, Kasimir Malevich, Pietro Manzoni, Gordon Matta-Clark, Peo Olsson, Katarina Sjögren, Jonas Williamsson, Roman Opalka, Nam June Paik, Readymades belong to everyone®, Jeffrey Shaw, Annegret Soltau, Daniel Soutif & Paule Zajderman, Klaus Staeck, Anne Le Troter, Manfred Wolff-Plottegg, Erwin Wurm

-

Curator

Livia Nolasco-RózsásCuratorial team

Felix Koberstein (ZKM)

Moritz Konrad (ZKM)

Marcella Lista (Centre Pompidou, Paris)

Philippe Bettinelli (Centre Pompidou, Paris)

Julie Champion (Centre Pompidou, Paris)Beyond Matter project team at ZKM

Marianne Schädler (managing editor)

Aurora Bertolli (communication)Exhibition team

Matthias Gommel (Scenography)

Janine Burger (Participation)

Thomas Schwab (Technical project management)Graphic design

AKU.coMuseum and Exhibition Technology

Martin Mangold - Organization / Institution

- Initiated by the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe and the Centre Pompidou, Paris, in collaboration with the Aalto University, Espoo, the Tallinn Art Hall, and the Tirana Art Lab.

>>>

Further locations and dates:

| Mar 14, 2022 – Mar 29, 2022 | Väre, Aalto University, Espoo |

| Apr 20, 2022 – Apr 25, 2022 | The Cube / Helsinki Central Library Oodi |

| Apr 25, 2022 – May 5, 2022 | Väre, Aalto University, Espoo |

| May 16, 2022 – May 22, 2022 | Design Museum Helsinki |

| June 25, 2022 – August 28, 2022 | Tirana Art Lab, Albanien |

| Dec 3, 2022 – Apr 23, 2023 | ZKM |

| Summer 2023 | Centre Pompidou, Paris |

---

Project

Cooperation partners

Supported by

Tuesday, September 21. 2021

"Essais climatiques" by P. Rahm, Ed. B2 (Paris, 2020) | #2ndaugmentation #essay #AR #VR

Note: it is with great pleasure and interest that I read recently one of Philippe Rahm's last publication, "Essais climatiques" (published in French, by Editions B2), which consists in fact in a collection of articles published in the past 10+ years in various magazines, journals and exhibition catalogs. It is certainly less developed than the even more recent book, "L'histoire naturelle de l'architecture" (ed. Pavillon de l'Arsenal, 2020), but nonetheless an excellent and brief introduction to his thinking and work.

Philippe Rahm's call for the "return" of an "objective architecture", climatic and free of narrative issues, is of great interest. Especially at a time when we need to reduce our CO2 emissions and will need to reach energy objectives of slenderness. The historical reading of the postmodern era (in architecture), in relation to oil, vaccines and antibiotics is also really valuable in this context, when we are all looking to move forward this time in cultural history.

I also had the good surprise, and joy, to see the text "L'âge de la deuxième augmentation" finally published! It was written by Philippe back in 2009 probably, about the works of fabric | ch at the time, when we were preparing a publication that finally never came out... Though this text will also be part of a monographic publication that is expected to be finalized and self-published in 2022.

Via fabric | ch

-----

Friday, August 28. 2020

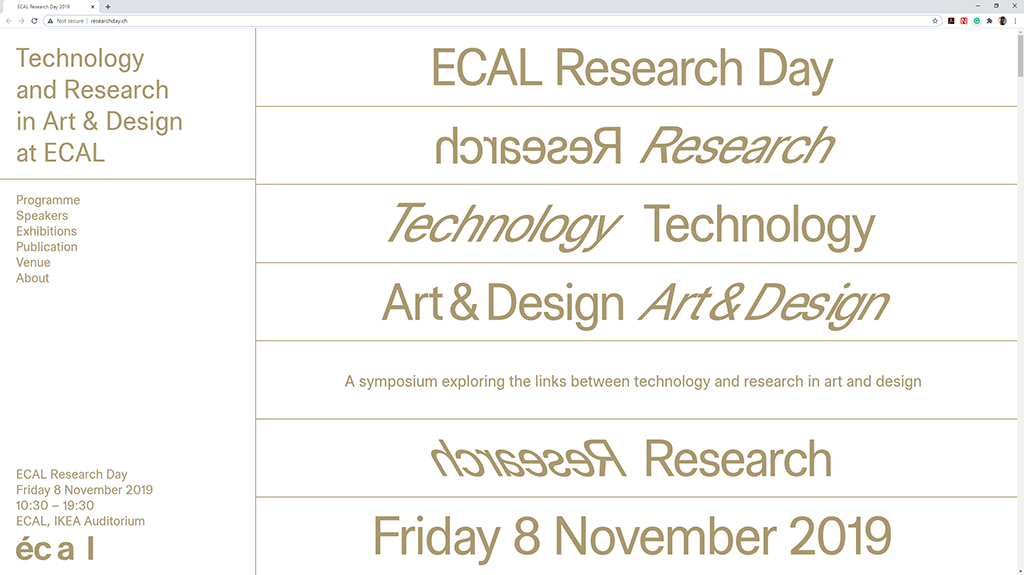

"Data Materialization", N. Kane (V&A) in discussion with P. Keller (ECAL, fabric | ch), ECAL website (Lausanne, 2020) | #data #research

Note: the discussion about "Data Materialization" between Nathalie Kane (V&A Museum, London) and Patrick Keller (fabric | ch, ECAL / University of Art and Design Lausanne (HES-SO)), on the occasion of the ECAL Research Day, has been published on the dedicated website, along with other interesting talks.

-----

Via ECAL

Research Day 2019 Natalie D. Kane from ECAL on Vimeo.

Friday, February 01. 2019

The Yoda of Silicon Valley | #NewYorkTimes #Algorithms

Note: Yet another dive into history of computer programming and algorithms, used for visual outputs ...

Via The New York Times (on Medium)

-----

By Siobhan Roberts

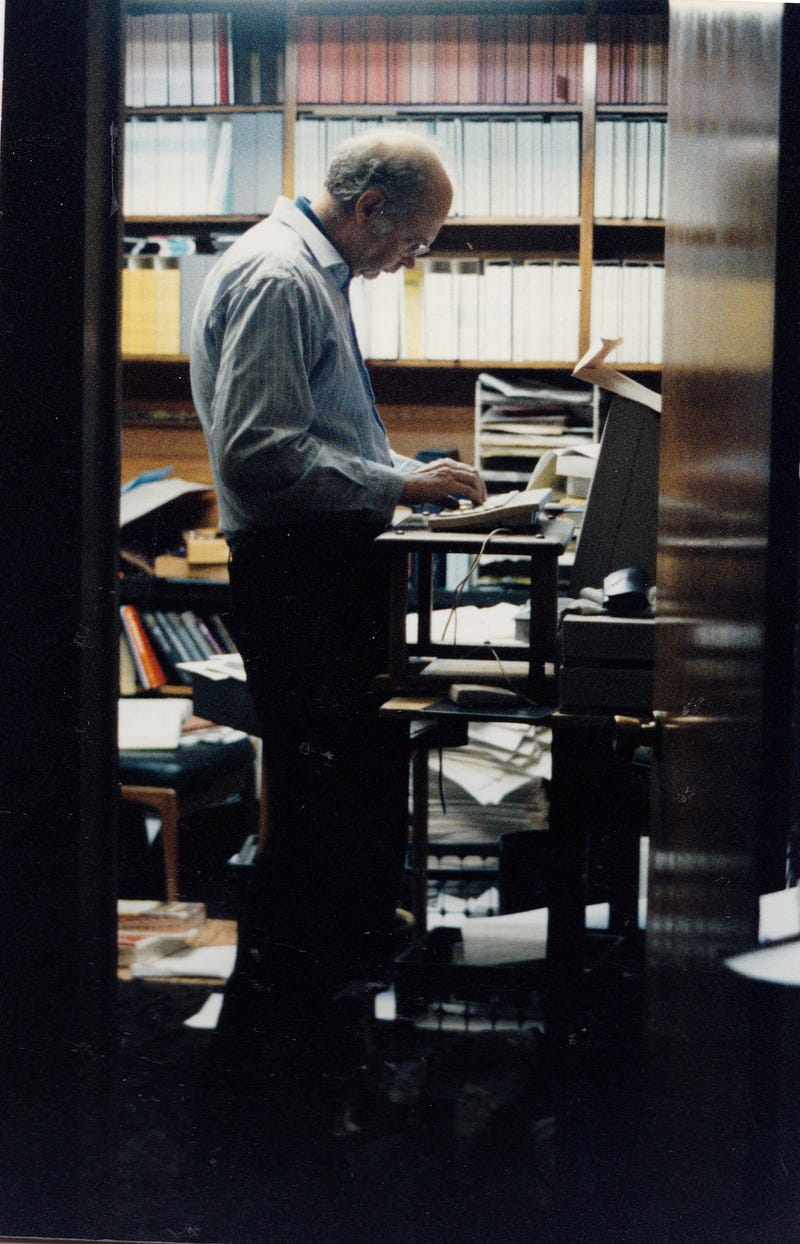

Donald Knuth at his home in Stanford, Calif. He is a notorious perfectionist and has offered to pay a reward to anyone who finds a mistake in any of his books. Photo: Brian Flaherty

For half a century, the Stanford computer scientist Donald Knuth, who bears a slight resemblance to Yoda — albeit standing 6-foot-4 and wearing glasses — has reigned as the spirit-guide of the algorithmic realm.

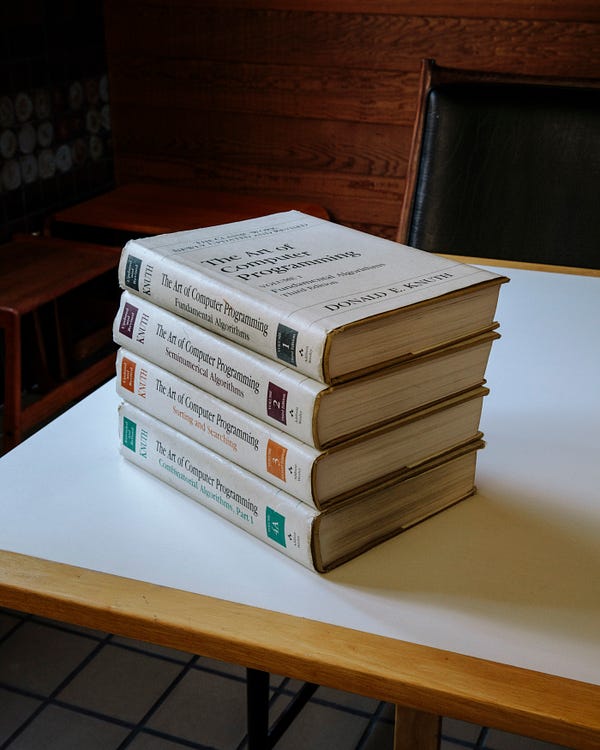

He is the author of “The Art of Computer Programming,” a continuing four-volume opus that is his life’s work. The first volume debuted in 1968, and the collected volumes (sold as a boxed set for about $250) were included by American Scientist in 2013 on its list of books that shaped the last century of science — alongside a special edition of “The Autobiography of Charles Darwin,” Tom Wolfe’s “The Right Stuff,” Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” and monographs by Albert Einstein, John von Neumann and Richard Feynman.

With more than one million copies in print, “The Art of Computer Programming” is the Bible of its field. “Like an actual bible, it is long and comprehensive; no other book is as comprehensive,” said Peter Norvig, a director of research at Google. After 652 pages, volume one closes with a blurb on the back cover from Bill Gates: “You should definitely send me a résumé if you can read the whole thing.”

The volume opens with an excerpt from “McCall’s Cookbook”:

Here is your book, the one your thousands of letters have asked us to publish. It has taken us years to do, checking and rechecking countless recipes to bring you only the best, only the interesting, only the perfect.

Inside are algorithms, the recipes that feed the digital age — although, as Dr.Knuth likes to point out, algorithms can also be found on Babylonian tablets from 3,800 years ago. He is an esteemed algorithmist; his name is attached to some of the field’s most important specimens, such as the Knuth-Morris-Pratt string-searching algorithm. Devised in 1970, it finds all occurrences of a given word or pattern of letters in a text — for instance, when you hit Command+F to search for a keyword in a document.

Now 80, Dr. Knuth usually dresses like the youthful geek he was when he embarked on this odyssey: long-sleeved T-shirt under a short-sleeved T-shirt, with jeans, at least at this time of year. In those early days, he worked close to the machine, writing “in the raw,” tinkering with the zeros and ones.

“Knuth made it clear that the system could actually be understood all the way down to the machine code level,” said Dr. Norvig. Nowadays, of course, with algorithms masterminding (and undermining) our very existence, the average programmer no longer has time to manipulate the binary muck, and works instead with hierarchies of abstraction, layers upon layers of code — and often with chains of code borrowed from code libraries. But an elite class of engineers occasionally still does the deep dive.

“Here at Google, sometimes we just throw stuff together,” Dr. Norvig said, during a meeting of the Google Trips team, in Mountain View, Calif. “But other times, if you’re serving billions of users, it’s important to do that efficiently. A 10-per-cent improvement in efficiency can work out to billions of dollars, and in order to get that last level of efficiency, you have to understand what’s going on all the way down.”

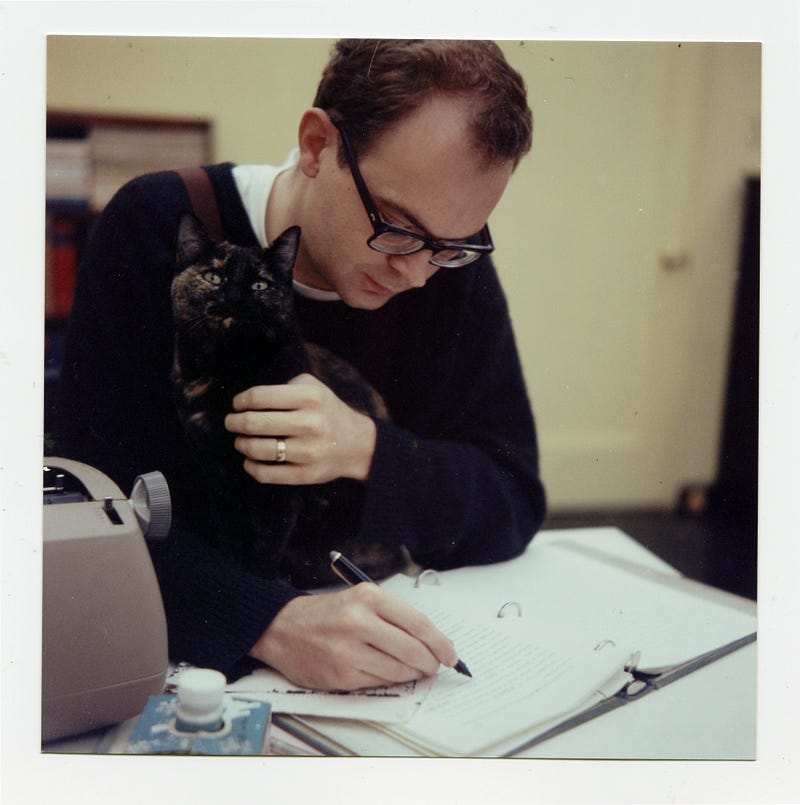

Dr. Knuth at the California Institute of Technology, where he received his Ph.D. in 1963. Photo: Jill Knuth

Or, as Andrei Broder, a distinguished scientist at Google and one of Dr. Knuth’s former graduate students, explained during the meeting: “We want to have some theoretical basis for what we’re doing. We don’t want a frivolous or sloppy or second-rate algorithm. We don’t want some other algorithmist to say, ‘You guys are morons.’”

The Google Trips app, created in 2016, is an “orienteering algorithm” that maps out a day’s worth of recommended touristy activities. The team was working on “maximizing the quality of the worst day” — for instance, avoiding sending the user back to the same neighborhood to see different sites. They drew inspiration from a 300-year-old algorithm by the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler, who wanted to map a route through the Prussian city of Königsberg that would cross each of its seven bridges only once. Dr. Knuth addresses Euler’s classic problem in the first volume of his treatise. (He once applied Euler’s method in coding a computer-controlled sewing machine.)

Following Dr. Knuth’s doctrine helps to ward off moronry. He is known for introducing the notion of “literate programming,” emphasizing the importance of writing code that is readable by humans as well as computers — a notion that nowadays seems almost twee. Dr. Knuth has gone so far as to argue that some computer programs are, like Elizabeth Bishop’s poems and Philip Roth’s “American Pastoral,” works of literature worthy of a Pulitzer.

He is also a notorious perfectionist. Randall Munroe, the xkcd cartoonist and author of “Thing Explainer,” first learned about Dr. Knuth from computer-science people who mentioned the reward money Dr. Knuth pays to anyone who finds a mistake in any of his books. As Mr. Munroe recalled, “People talked about getting one of those checks as if it was computer science’s Nobel Prize.”

Dr. Knuth’s exacting standards, literary and otherwise, may explain why his life’s work is nowhere near done. He has a wager with Sergey Brin, the co-founder of Google and a former student (to use the term loosely), over whether Mr. Brin will finish his Ph.D. before Dr. Knuth concludes his opus.

The dawn of the algorithm

At age 19, Dr. Knuth published his first technical paper, “The Potrzebie System of Weights and Measures,” in Mad magazine. He became a computer scientist before the discipline existed, studying mathematics at what is now Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. He looked at sample programs for the school’s IBM 650 mainframe, a decimal computer, and, noticing some inadequacies, rewrote the software as well as the textbook used in class. As a side project, he ran stats for the basketball team, writing a computer program that helped them win their league — and earned a segment by Walter Cronkite called “The Electronic Coach.”

During summer vacations, Dr. Knuth made more money than professors earned in a year by writing compilers. A compiler is like a translator, converting a high-level programming language (resembling algebra) to a lower-level one (sometimes arcane binary) and, ideally, improving it in the process. In computer science, “optimization” is truly an art, and this is articulated in another Knuthian proverb: “Premature optimization is the root of all evil.”

Eventually Dr. Knuth became a compiler himself, inadvertently founding a new field that he came to call the “analysis of algorithms.” A publisher hired him to write a book about compilers, but it evolved into a book collecting everything he knew about how to write for computers — a book about algorithms.

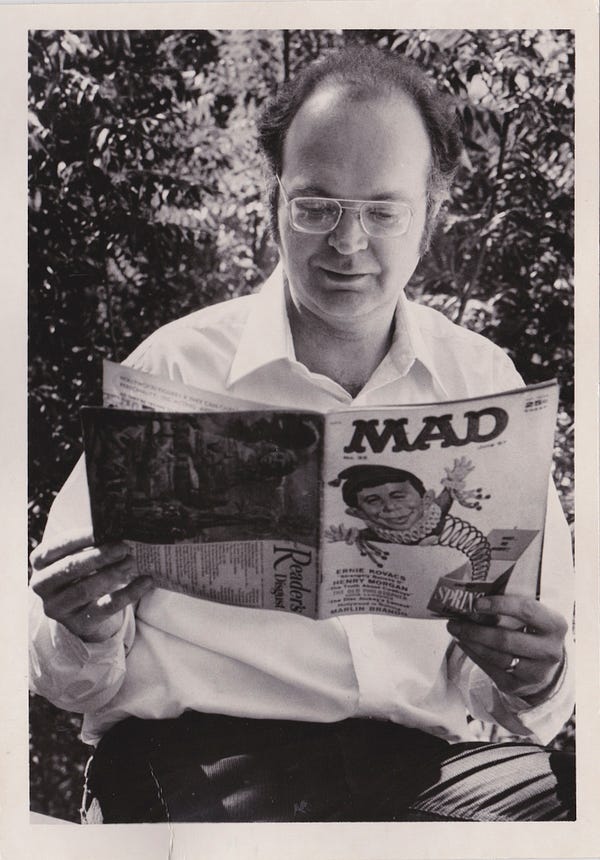

Left: Dr. Knuth in 1981, looking at the 1957 Mad magazine issue that contained his first technical article. He was 19 when it was published. Photo: Jill Knuth. Right: “The Art of Computer Programming,” volumes 1–4. “Send me a résumé if you can read the whole thing,” Bill Gates wrote in a blurb. Photo: Brian Flaherty

“By the time of the Renaissance, the origin of this word was in doubt,” it began. “And early linguists attempted to guess at its derivation by making combinations like algiros [painful] + arithmos [number].’” In fact, Dr. Knuth continued, the namesake is the 9th-century Persian textbook author Abū ‘Abd Allāh Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī, Latinized as Algorithmi. Never one for half measures, Dr. Knuth went on a pilgrimage in 1979 to al-Khwārizmī’s ancestral homeland in Uzbekistan.

When Dr. Knuth started out, he intended to write a single work. Soon after, computer science underwent its Big Bang, so he reimagined and recast the project in seven volumes. Now he metes out sub-volumes, called fascicles. The next installation, “Volume 4, Fascicle 5,” covering, among other things, “backtracking” and “dancing links,” was meant to be published in time for Christmas. It is delayed until next April because he keeps finding more and more irresistible problems that he wants to present.

In order to optimize his chances of getting to the end, Dr. Knuth has long guarded his time. He retired at 55, restricted his public engagements and quit email (officially, at least). Andrei Broder recalled that time management was his professor’s defining characteristic even in the early 1980s.

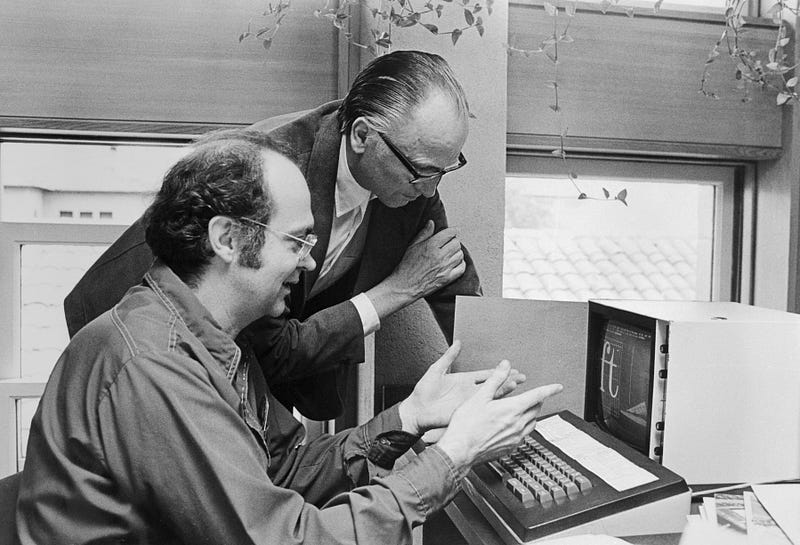

Dr. Knuth typically held student appointments on Friday mornings, until he started spending his nights in the lab of John McCarthy, a founder of artificial intelligence, to get access to the computers when they were free. Horrified by what his beloved book looked like on the page with the advent of digital publishing, Dr. Knuth had gone on a mission to create the TeX computer typesetting system, which remains the gold standard for all forms of scientific communication and publication. Some consider it Dr. Knuth’s greatest contribution to the world, and the greatest contribution to typography since Gutenberg.

This decade-long detour took place back in the age when computers were shared among users and ran faster at night while most humans slept. So Dr. Knuth switched day into night, shifted his schedule by 12 hours and mapped his student appointments to Fridays from 8 p.m. to midnight. Dr. Broder recalled, “When I told my girlfriend that we can’t do anything Friday night because Friday night at 10 I have to meet with my adviser, she thought, ‘This is something that is so stupid it must be true.’”

When Knuth chooses to be physically present, however, he is 100-per-cent there in the moment. “It just makes you happy to be around him,” said Jennifer Chayes, a managing director of Microsoft Research. “He’s a maximum in the community. If you had an optimization function that was in some way a combination of warmth and depth, Don would be it.”

Dr. Knuth discussing typefaces with Hermann Zapf, the type designer. Many consider Dr. Knuth’s work on the TeX computer typesetting system to be the greatest contribution to typography since Gutenberg. Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images

Sunday with the algorithmist

Dr. Knuth lives in Stanford, and allowed for a Sunday visitor. That he spared an entire day was exceptional — usually his availability is “modulo nap time,” a sacred daily ritual from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. He started early, at Palo Alto’s First Lutheran Church, where he delivered a Sunday school lesson to a standing-room-only crowd. Driving home, he got philosophical about mathematics.

“I’ll never know everything,” he said. “My life would be a lot worse if there was nothing I knew the answers about, and if there was nothing I didn’t know the answers about.” Then he offered a tour of his “California modern” house, which he and his wife, Jill, built in 1970. His office is littered with piles of U.S.B. sticks and adorned with Valentine’s Day heart art from Jill, a graphic designer. Most impressive is the music room, built around his custom-made, 812-pipe pipe organ. The day ended over beer at a puzzle party.

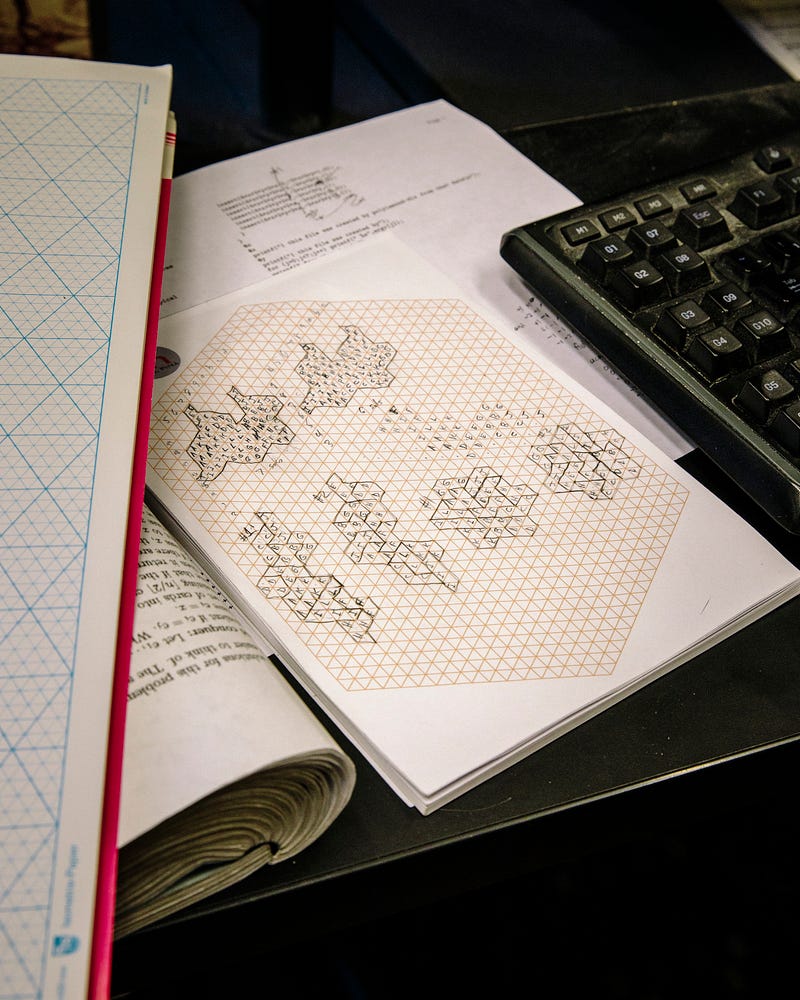

Puzzles and games — and penning a novella about surreal numbers, and composing a 90-minute multimedia musical pipe-dream, “Fantasia Apocalyptica” — are the sorts of things that really tickle him. One section of his book is titled, “Puzzles Versus the Real World.” He emailed an excerpt to the father-son team of Martin Demaine, an artist, and Erik Demaine, a computer scientist, both at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, because Dr. Knuth had included their “algorithmic puzzle fonts.”

“I was thrilled,” said Erik Demaine. “It’s an honor to be in the book.” He mentioned another Knuth quotation, which serves as the inspirational motto for the biannual “FUN with Algorithms” conference: “Pleasure has probably been the main goal all along.”

But then, Dr. Demaine said, the field went and got practical. Engineers and scientists and artists are teaming up to solve real-world problems — protein folding, robotics, airbags — using the Demaines’s mathematical origami designs for how to fold paper and linkages into different shapes.

Of course, all the algorithmic rigmarole is also causing real-world problems. Algorithms written by humans — tackling harder and harder problems, but producing code embedded with bugs and biases — are troubling enough. More worrisome, perhaps, are the algorithms that are not written by humans, algorithms written by the machine, as it learns.

Programmers still train the machine, and, crucially, feed it data. (Data is the new domain of biases and bugs, and here the bugs and biases are harder to find and fix). However, as Kevin Slavin, a research affiliate at M.I.T.’s Media Lab said, “We are now writing algorithms we cannot read. That makes this a unique moment in history, in that we are subject to ideas and actions and efforts by a set of physics that have human origins without human comprehension.” As Slavin has often noted, “It’s a bright future, if you’re an algorithm.”

Dr. Knuth at his desk at home in 1999. Photo: Jill Knuth

A few notes. Photo: Brian Flaherty

All the more so if you’re an algorithm versed in Knuth. “Today, programmers use stuff that Knuth, and others, have done as components of their algorithms, and then they combine that together with all the other stuff they need,” said Google’s Dr. Norvig.

“With A.I., we have the same thing. It’s just that the combining-together part will be done automatically, based on the data, rather than based on a programmer’s work. You want A.I. to be able to combine components to get a good answer based on the data. But you have to decide what those components are. It could happen that each component is a page or chapter out of Knuth, because that’s the best possible way to do some task.”

Lucky, then, Dr. Knuth keeps at it. He figures it will take another 25 years to finish “The Art of Computer Programming,” although that time frame has been a constant since about 1980. Might the algorithm-writing algorithms get their own chapter, or maybe a page in the epilogue? “Definitely not,” said Dr. Knuth.

“I am worried that algorithms are getting too prominent in the world,” he added. “It started out that computer scientists were worried nobody was listening to us. Now I’m worried that too many people are listening.”

Monday, December 17. 2018

In 1968, computers got personal | #demo #newdemo?

Note: we went a bit historical recently on | rblg, digging into history of computing in relation to design/architecture/art. And the following one is certainly far from being the less know... History of computing, or rather personal computing. Yet the article by Maraget O'Mara bring new insights about Engelbart's "mother of all demos", asking in particular for a new "demo".

It is also interesting to consider how some topics that we'd believe are very contemporary, were in fact already popping up pretty early in the history of the media.

Questiond about the status of the machine in relation to us, humans, or about the collection of data, etc. If you go back to the early texts by Wiener and Turing (vulgarization texts... for my part), you might see that the questions we still have were already present.

Via The Conversation

-----

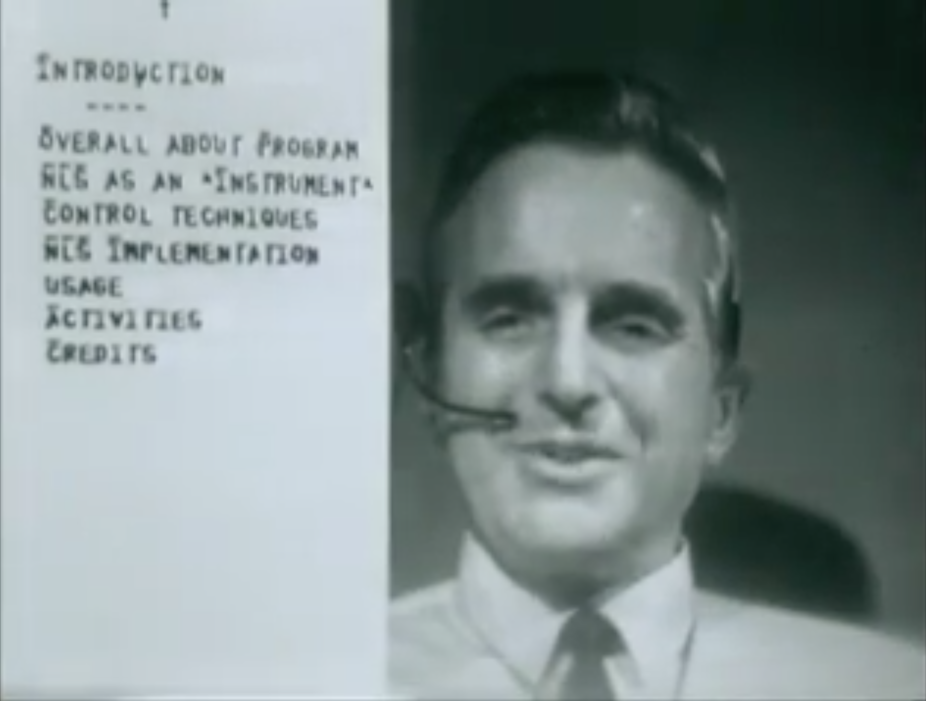

On a crisp California afternoon in early December 1968, a square-jawed, mild-mannered Stanford researcher named Douglas Engelbart took the stage at San Francisco’s Civic Auditorium and proceeded to blow everyone’s mind about what computers could do. Sitting down at a keyboard, this computer-age Clark Kent calmly showed a rapt audience of computer engineers how the devices they built could be utterly different kinds of machines – ones that were “alive for you all day,” as he put it, immediately responsive to your input, and which didn’t require users to know programming languages in order to operate.

The prototype computer mouse Doug Engelbart used in his demo. Michael Hicks, CC BY

Engelbart typed simple commands. He edited a grocery list. As he worked, he skipped the computer cursor across the screen using a strange wooden box that fit snugly under his palm. With small wheels underneath and a cord dangling from its rear, Engelbart dubbed it a “mouse.”

The 90-minute presentation went down in Silicon Valley history as the “mother of all demos,” for it previewed a world of personal and online computing utterly different from 1968’s status quo. It wasn’t just the technology that was revelatory; it was the notion that a computer could be something a non-specialist individual user could control from their own desk.

The first part of the "mother of all demos."

Shrinking the massive machines

In the America of 1968, computers weren’t at all personal. They were refrigerator-sized behemoths that hummed and blinked, calculating everything from consumer habits to missile trajectories, cloistered deep within corporate offices, government agencies and university labs. Their secrets were accessible only via punch card and teletype terminals.

The Vietnam-era counterculture already had made mainframe computers into ominous symbols of a soul-crushing Establishment. Four years before, the student protesters of Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement had pinned signs to their chests that bore a riff on the prim warning that appeared on every IBM punch card: “I am a UC student. Please don’t bend, fold, spindle or mutilate me.”

Hear Prof. O'Mara discuss this topic on our Heat and Light podcast.

Earlier in 1968, Stanley Kubrick’s trippy “2001: A Space Odyssey” mined moviegoers’ anxieties about computers run amok with the tale of a malevolent mainframe that seized control of a spaceship from its human astronauts.

Voices rang out on Capitol Hill about the uses and abuses of electronic data-gathering, too. Missouri Senator Ed Long regularly delivered floor speeches he called “Big Brother updates.” North Carolina Senator Sam Ervin declared that mainframe power posed a threat to the freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution. “The computer,” Ervin warned darkly, “never forgets.” As the Johnson administration unveiled plans to centralize government data in a single, centralized national database, New Jersey Congressman Cornelius Gallagher declared that it was just another grim step toward scientific thinking taking over modern life, “leaving as an end result a stack of computer cards where once were human beings.”

The zeitgeist of 1968 helps explain why Engelbart’s demo so quickly became a touchstone and inspiration for a new, enduring definition of technological empowerment. Here was a computer that didn’t override human intelligence or stomp out individuality, but instead could, as Engelbart put it, “augment human intellect.”

While Engelbart’s vision of how these tools might be used was rather conventionally corporate – a computer on every office desk and a mouse in every worker’s palm – his overarching notion of an individualized computer environment hit exactly the right note for the anti-Establishment technologists coming of age in 1968, who wanted to make technology personal and information free.

The second part of the "mother of all demos."

Over the next decade, technologists from this new generation would turn what Engelbart called his “wild dream” into a mass-market reality – and profoundly transform Americans’ relationship to computer technology.

Government involvement

In the decade after the demo, the crisis of Watergate and revelations of CIA and FBI snooping further seeded distrust in America’s political leadership and in the ability of large government bureaucracies to be responsible stewards of personal information. Economic uncertainty and an antiwar mood slashed public spending on high-tech research and development – the same money that once had paid for so many of those mainframe computers and for training engineers to program them.

Enabled by the miniaturizing technology of the microprocessor, the size and price of computers plummeted, turning them into affordable and soon indispensable tools for work and play. By the 1980s and 1990s, instead of being seen as machines made and controlled by government, computers had become ultimate expressions of free-market capitalism, hailed by business and political leaders alike as examples of what was possible when government got out of the way and let innovation bloom.

There lies the great irony in this pivotal turn in American high-tech history. For even though “the mother of all demos” provided inspiration for a personal, entrepreneurial, government-is-dangerous-and-small-is-beautiful computing era, Doug Engelbart’s audacious vision would never have made it to keyboard and mouse without government research funding in the first place.

Engelbart was keenly aware of this, flashing credits up on the screen at the presentation’s start listing those who funded his research team: the Defense Department’s Advanced Projects Research Agency, later known as DARPA; the National Aeronautics and Space Administration; the U.S. Air Force. Only the public sector had the deep pockets, the patience and the tolerance for blue-sky ideas without any immediate commercial application.

Although government funding played a less visible role in the high-tech story after 1968, it continued to function as critical seed capital for next-generation ideas. Marc Andreessen and his fellow graduate students developed their groundbreaking web browser in a government-funded university laboratory. DARPA and NASA money helped fund the graduate research project that Sergey Brin and Larry Page would later commercialize as Google. Driverless car technology got a jump-start after a government-sponsored competition; so has nanotechnology, green tech and more. Government hasn’t gotten out of Silicon Valley’s way; it remained there all along, quietly funding the next generation of boundary-pushing technology.

The third part of the "mother of all demos."

Today, public debate rages once again on Capitol Hill about computer-aided invasions of privacy. Hollywood spins apocalyptic tales of technology run amok. Americans spend days staring into screens, tracked by the smartphones in our pockets, hooked on social media. Technology companies are among the biggest and richest in the world. It’s a long way from Engelbart’s humble grocery list.

But perhaps the current moment of high-tech angst can once again gain inspiration from the mother of all demos. Later in life, Engelbart described his life’s work as a quest to “help humanity cope better with complexity and urgency.” His solution was a computer that was remarkably different from the others of that era, one that was humane and personal, that augmented human capability rather than boxing it in. And he was able to bring this vision to life because government agencies funded his work.

Now it’s time for another mind-blowing demo of the possible future, one that moves beyond the current adversarial moment between big government and Big Tech. It could inspire people to enlist public and private resources and minds in crafting the next audacious vision for our digital future.

-

Our new podcast “Heat and Light” features Prof. O'Mara discussing this story in depth.

Related Links:

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.

Quicksearch

Categories

Calendar

|

|

July '25 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||