Nothing dates faster than the future. Listen to any pop record and the thing that places it most precisely in time is the thing that was once so shiny and new. The electronic future is particularly susceptible to this ageing process; the synthesiser solo at the end of Ike and Tina Turner's "Nutbush City Limits" is totally 1973; the Auto-Tune on Cher's "Believe" is a time capsule from 1998.

It seems like a paradox. Part of the appeal of electronic music has always been the supposed neutrality of its sounds. A note played on a cello is freighted with history, but a sine tone is a sound so simple that it seems to exist in the natural world. The electronic music studios of the 1950s, the analogue synthesisers of the 60s and 70s, and the computers that in turn have replaced them have all used these simple sounds as their basic building blocks, but pass a sine tone through an electronic circuit and it emerges date‑stamped with the age of the technology and the aspirations of the musicians using it.

The science-fiction film Return to the Forbidden Planet is a classic example. In 1956, when the film was made, the future was electric, so the film's soundtrack is full of oscillators humming, swooshing and bleeping as the space cruiser C57D circles planet Altair IV. It's difficult to tell where the sound effects end and the musical underscoring begins; indeed, the creators of the soundtrack, Louis and Bebe Barron, appear in the title credits not as "composers" but as creators of "electronic tonalities".

In 1956 the future was alien and otherworldly. By 1974, Kraftwerk were using electronic music to tell us that it was here and now, the robotic repetitions of "Autobahn" an expression of the grids within which we lived our lives. A decade later, in derelict warehouses, looping melodies, bass lines and drum tracks pumped out the message that there was no future: only now, only raving. More recently the future seems to have become a thing of the past. New music is full of old electronic sounds, none more ubiquitous than Auto-Tune, as we yearn for the future that we used to believe in.

It's not just the old sounds that are the subject of this disillusion-fuelled nostalgia; it's the machines that made them, too. The remorseless march of progress, from valve to chip, tape to hard disk, studio to laptop, has been paused while musicians rummage around in the back of the cupboard, pulling out ancient reel-to-reel tape recorders and revelling in the quaint mechanical aura they give to any sound that passes through them. In 2002 the White Stripes recorded their Elephant CD the old-fashioned way, on tape; this year, it has been rereleased on vinyl on Jack White's own label. He denies he's a Luddite: "It's like I can't be proud of it unless I know we overcame some kind of struggle."

In the 50s, tape machines were at the heart of every studio. For the first time in history, sounds could be measured not just in time but in centimetres, as lengths of magnetic tape travelling past the record and playback heads of tape recorders. Sounds could be reversed, slowed down, speeded up and layered over and over again. For his Williams Mix, John Cage spent three years sticking bits of magnetic tape together. The tapes were in six categories – "city", "country", "electronic", "manually produced", "wind" and "small" – and, tying a satisfactory knot in the fabric of music history, they were recorded for Cage by Louis and Bebe Barron, the Barrons of The Forbidden Planet. Everything else was determined by chance: from which of the six sound categories each bit of tape should come, how long it should be, and finally, into which of eight tape sequences it was to be stuck. By 1953 the collage was complete and all eight tapes were played simultaneously: four minutes and 15 seconds of sonic mayhem.

Cage's work was part of a privately funded "Project for Music for Magnetic Tape". In Europe, the use of tape machines was at its most adventurous in the state-sponsored radio stations, nowhere more so than in Paris and Cologne. But there was an ideological split: Paris was the home of musique concrète, music made by recording and transforming the sounds of the world around us; Cologne was the headquarters of elektronische musik, using the applied science of oscillators and filters to construct new sounds for a new world. It's an aesthetic axis around which musicians still orientate themselves. Do you start with a sound recorded from the real world, with all its intrinsic life, or do you build new sounds from scratch?

At its simplest it's a distinction between surrealism and abstraction. The microphone is a lens which allows the sounds around us to be captured, then cropped, stretched, juxtaposed. 'Art exists to help us to recover the sensation of life […] the technique […] is to make things "unfamiliar"', said Viktor Shklovsky in 1916, but it could have been the pioneer of musique concrète, Pierre Schaeffer, explaining the aesthetics of the Paris studio. Or it could have been Schaeffer's colleague Pierre Henry in 1963 explaining how he transformed the creak of a door-hinge and an exhalation into a series of 25 variations for a door and a sigh.

In fact, Shklovsky was writing Russian literary theory, introducing his concept of "ostranenie" (making strange) – an idea waiting for the technology to turn it from words into sounds. Record, cut, stick, loop – it's an endlessly fascinating technique that probably crossed over into mass consciousness in 1973 with Pink Floyd's cash-register riff on "Money". Certainly the university music text-books of the time were happy to claim the mix of synths and sound collage on The Dark Side of the Moon as an affirmation of electronic music and musique concrète's capacity to engage with a pop sensibility.

But sound recording is always a means of making strange. It's an act of selection: what sort of microphone, where to put it, when to begin, when to end? Opening and closing our eyes is easy; it's much harder to close our ears, so deciding to listen to just this, for just this long, is quite unnatural. Nevertheless, there are composers and sound artists who have devoted themselves to the illusion that the world recorded in sound is the world itself. It's an idea that keeps coming round: in the 1970s, Hildegard Westerkamp and R Murray Schafer tried to document disappearing 'acoustic ecologies' with their Soundscapes project. These days it's called "field recording" and the doyen is Chris Watson, who last year made In Britten's Footsteps, an audio recreation of the landscape around Benjamin Britten's home in Aldeburgh.

My favourite soundscape is a glorious hybrid, Luc Ferrari's Presque Rien (1967–70). It sounds like a field recording – early morning in a Croatian fishing village – but it can't be: first light of day is compressed into just over 20 minutes, artifice masquerading as nature. Perhaps hybrids flourish best. In the 1950s, Stockhausen worked in the Cologne studios of West German Radio and his first tape works, two Electronic Studies, were on the elektronische musik side of the great aesthetic divide. In 1955, however, he decided to embark on a hybrid, and his new work, Gesang der Jünglinge (Song of the Youths), combined pure electronic sounds with the recorded voice of a boy singing passages from the Old Testament story of the three young men who miraculously survived after being cast into King Nebuchadnezzar's fiery furnace.

It is an extraordinarily ambitious conception: at over 13 minutes, it is longer than any other electronic work of the period and, though composed at a time when stereo was still a novelty, it is in five-channel sound. Above all, it's full of life. Stockhausen – in those days a Roman Catholic – had intended to create an "electronic mass", but the vivid juxtaposition of the boy's voice, alone but resolute, amid the bubbling cauldron of electronic sound proved a much better idea. The humanity of a solo voice set in an abstract electronic landscape is a powerful and recurrent musical image, whether in Milton Babbit's 1964 Philomel for solo soprano and tape, or Donna Summer's "I feel love".

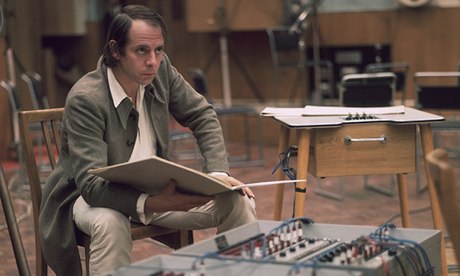

Aesthetic breakthroughs … Karlheinz Stockhausen in the mid 1960s. Photograph: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis

Gesang der Jünglinge was a technical and aesthetic breakthrough, but Stockhausen's next studio project was even more remarkable. In Kontakte (Contacts), the real-world sounds are live, played by a pianist and a percussionist, and Stockhausen brings off a series of spectacular aural illusions in which prerecorded tape sounds appear to imitate, anticipate and transform the sounds of the live instruments before taking off into another world of their own. That Stockhausen could bully the banks of oscillators, filters and modulators in the Cologne studio into producing such amazing trompes l'oreille is a tribute to his imagination and his industry: it took him more than two years to complete.

These days, Kontakte would take weeks rather than years. The instrumental sounds could be sampled, analysed and remodelled in any one of a number of readily available software programmes, and perhaps that's another reason why the future isn't as interesting as it used to be. Computers started out in music in the 50s by emulating the simpler electronic devices of the period – oscillators and filters don't need much processing power – and in its early days, computer music was just that: music that sounded as if it had come out of a computer. But as computers grew quicker and stronger, they became more self-effacing; instead of buzzing and bleeping, they began to mimic familiar musical instruments. Yamaha's DX7, the smartest synth in town in the early 80s, used sophisticated maths to produce simulacra of acoustic instrumental sounds. It couldn't replicate them exactly, but, in the midst of a pop-song mix, the sounds were convincing enough, a sort of musical mock-Tudor.

These days, computers can recreate not only the instrument but the acoustic around it. Whether recording and editing the real world, or generating new sounds, it's all easy with a laptop; under the keyboard on which I'm typing this article there is space for the digital equivalent of rooms full of equipment from the old Cologne and Paris studios. All too easy? Possibly. Gesang der Jünglinge and Kontakte are masterpieces. That's why they're being featured in the Southbank Centre's year-long celebration of 20th-century music, The Rest is Noise. But, at least in part, they're masterpieces because of the resistance of the materials with which Stockhausen had to work, the intractability of all that old technology. Perhaps it's time to invent a new future.

• Christopher Fox will introduce Stockhausen's Gesang der Jünglinge and Kontakte in the Queen Elizabeth Hall, London SE1, tonight. southbankcentre.co.uk.