Sticky Postings

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Thursday, October 10. 2013

Via The Guardian

-----

By Christopher Fox

Whether in the 1950s studios of Paris or Cologne, the first electronic sounds of the future were forged through graft and experimentation. Now those works speak vividly of their time

Model lineup … Kraftwerk used electronic music to tell us that it was here and now. Photograph: Steffen Schmidt/AP

Nothing dates faster than the future. Listen to any pop record and the thing that places it most precisely in time is the thing that was once so shiny and new. The electronic future is particularly susceptible to this ageing process; the synthesiser solo at the end of Ike and Tina Turner's "Nutbush City Limits" is totally 1973; the Auto-Tune on Cher's "Believe" is a time capsule from 1998.

It seems like a paradox. Part of the appeal of electronic music has always been the supposed neutrality of its sounds. A note played on a cello is freighted with history, but a sine tone is a sound so simple that it seems to exist in the natural world. The electronic music studios of the 1950s, the analogue synthesisers of the 60s and 70s, and the computers that in turn have replaced them have all used these simple sounds as their basic building blocks, but pass a sine tone through an electronic circuit and it emerges date‑stamped with the age of the technology and the aspirations of the musicians using it.

The science-fiction film Return to the Forbidden Planet is a classic example. In 1956, when the film was made, the future was electric, so the film's soundtrack is full of oscillators humming, swooshing and bleeping as the space cruiser C57D circles planet Altair IV. It's difficult to tell where the sound effects end and the musical underscoring begins; indeed, the creators of the soundtrack, Louis and Bebe Barron, appear in the title credits not as "composers" but as creators of "electronic tonalities".

In 1956 the future was alien and otherworldly. By 1974, Kraftwerk were using electronic music to tell us that it was here and now, the robotic repetitions of "Autobahn" an expression of the grids within which we lived our lives. A decade later, in derelict warehouses, looping melodies, bass lines and drum tracks pumped out the message that there was no future: only now, only raving. More recently the future seems to have become a thing of the past. New music is full of old electronic sounds, none more ubiquitous than Auto-Tune, as we yearn for the future that we used to believe in.

It's not just the old sounds that are the subject of this disillusion-fuelled nostalgia; it's the machines that made them, too. The remorseless march of progress, from valve to chip, tape to hard disk, studio to laptop, has been paused while musicians rummage around in the back of the cupboard, pulling out ancient reel-to-reel tape recorders and revelling in the quaint mechanical aura they give to any sound that passes through them. In 2002 the White Stripes recorded their Elephant CD the old-fashioned way, on tape; this year, it has been rereleased on vinyl on Jack White's own label. He denies he's a Luddite: "It's like I can't be proud of it unless I know we overcame some kind of struggle."

In the 50s, tape machines were at the heart of every studio. For the first time in history, sounds could be measured not just in time but in centimetres, as lengths of magnetic tape travelling past the record and playback heads of tape recorders. Sounds could be reversed, slowed down, speeded up and layered over and over again. For his Williams Mix, John Cage spent three years sticking bits of magnetic tape together. The tapes were in six categories – "city", "country", "electronic", "manually produced", "wind" and "small" – and, tying a satisfactory knot in the fabric of music history, they were recorded for Cage by Louis and Bebe Barron, the Barrons of The Forbidden Planet. Everything else was determined by chance: from which of the six sound categories each bit of tape should come, how long it should be, and finally, into which of eight tape sequences it was to be stuck. By 1953 the collage was complete and all eight tapes were played simultaneously: four minutes and 15 seconds of sonic mayhem.

Cage's work was part of a privately funded "Project for Music for Magnetic Tape". In Europe, the use of tape machines was at its most adventurous in the state-sponsored radio stations, nowhere more so than in Paris and Cologne. But there was an ideological split: Paris was the home of musique concrète, music made by recording and transforming the sounds of the world around us; Cologne was the headquarters of elektronische musik, using the applied science of oscillators and filters to construct new sounds for a new world. It's an aesthetic axis around which musicians still orientate themselves. Do you start with a sound recorded from the real world, with all its intrinsic life, or do you build new sounds from scratch?

At its simplest it's a distinction between surrealism and abstraction. The microphone is a lens which allows the sounds around us to be captured, then cropped, stretched, juxtaposed. 'Art exists to help us to recover the sensation of life […] the technique […] is to make things "unfamiliar"', said Viktor Shklovsky in 1916, but it could have been the pioneer of musique concrète, Pierre Schaeffer, explaining the aesthetics of the Paris studio. Or it could have been Schaeffer's colleague Pierre Henry in 1963 explaining how he transformed the creak of a door-hinge and an exhalation into a series of 25 variations for a door and a sigh.

In fact, Shklovsky was writing Russian literary theory, introducing his concept of "ostranenie" (making strange) – an idea waiting for the technology to turn it from words into sounds. Record, cut, stick, loop – it's an endlessly fascinating technique that probably crossed over into mass consciousness in 1973 with Pink Floyd's cash-register riff on "Money". Certainly the university music text-books of the time were happy to claim the mix of synths and sound collage on The Dark Side of the Moon as an affirmation of electronic music and musique concrète's capacity to engage with a pop sensibility.

But sound recording is always a means of making strange. It's an act of selection: what sort of microphone, where to put it, when to begin, when to end? Opening and closing our eyes is easy; it's much harder to close our ears, so deciding to listen to just this, for just this long, is quite unnatural. Nevertheless, there are composers and sound artists who have devoted themselves to the illusion that the world recorded in sound is the world itself. It's an idea that keeps coming round: in the 1970s, Hildegard Westerkamp and R Murray Schafer tried to document disappearing 'acoustic ecologies' with their Soundscapes project. These days it's called "field recording" and the doyen is Chris Watson, who last year made In Britten's Footsteps, an audio recreation of the landscape around Benjamin Britten's home in Aldeburgh.

My favourite soundscape is a glorious hybrid, Luc Ferrari's Presque Rien (1967–70). It sounds like a field recording – early morning in a Croatian fishing village – but it can't be: first light of day is compressed into just over 20 minutes, artifice masquerading as nature. Perhaps hybrids flourish best. In the 1950s, Stockhausen worked in the Cologne studios of West German Radio and his first tape works, two Electronic Studies, were on the elektronische musik side of the great aesthetic divide. In 1955, however, he decided to embark on a hybrid, and his new work, Gesang der Jünglinge (Song of the Youths), combined pure electronic sounds with the recorded voice of a boy singing passages from the Old Testament story of the three young men who miraculously survived after being cast into King Nebuchadnezzar's fiery furnace.

It is an extraordinarily ambitious conception: at over 13 minutes, it is longer than any other electronic work of the period and, though composed at a time when stereo was still a novelty, it is in five-channel sound. Above all, it's full of life. Stockhausen – in those days a Roman Catholic – had intended to create an "electronic mass", but the vivid juxtaposition of the boy's voice, alone but resolute, amid the bubbling cauldron of electronic sound proved a much better idea. The humanity of a solo voice set in an abstract electronic landscape is a powerful and recurrent musical image, whether in Milton Babbit's 1964 Philomel for solo soprano and tape, or Donna Summer's "I feel love".

Aesthetic breakthroughs … Karlheinz Stockhausen in the mid 1960s. Photograph: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis

Gesang der Jünglinge was a technical and aesthetic breakthrough, but Stockhausen's next studio project was even more remarkable. In Kontakte (Contacts), the real-world sounds are live, played by a pianist and a percussionist, and Stockhausen brings off a series of spectacular aural illusions in which prerecorded tape sounds appear to imitate, anticipate and transform the sounds of the live instruments before taking off into another world of their own. That Stockhausen could bully the banks of oscillators, filters and modulators in the Cologne studio into producing such amazing trompes l'oreille is a tribute to his imagination and his industry: it took him more than two years to complete.

These days, Kontakte would take weeks rather than years. The instrumental sounds could be sampled, analysed and remodelled in any one of a number of readily available software programmes, and perhaps that's another reason why the future isn't as interesting as it used to be. Computers started out in music in the 50s by emulating the simpler electronic devices of the period – oscillators and filters don't need much processing power – and in its early days, computer music was just that: music that sounded as if it had come out of a computer. But as computers grew quicker and stronger, they became more self-effacing; instead of buzzing and bleeping, they began to mimic familiar musical instruments. Yamaha's DX7, the smartest synth in town in the early 80s, used sophisticated maths to produce simulacra of acoustic instrumental sounds. It couldn't replicate them exactly, but, in the midst of a pop-song mix, the sounds were convincing enough, a sort of musical mock-Tudor.

These days, computers can recreate not only the instrument but the acoustic around it. Whether recording and editing the real world, or generating new sounds, it's all easy with a laptop; under the keyboard on which I'm typing this article there is space for the digital equivalent of rooms full of equipment from the old Cologne and Paris studios. All too easy? Possibly. Gesang der Jünglinge and Kontakte are masterpieces. That's why they're being featured in the Southbank Centre's year-long celebration of 20th-century music, The Rest is Noise. But, at least in part, they're masterpieces because of the resistance of the materials with which Stockhausen had to work, the intractability of all that old technology. Perhaps it's time to invent a new future.

• Christopher Fox will introduce Stockhausen's Gesang der Jünglinge and Kontakte in the Queen Elizabeth Hall, London SE1, tonight. southbankcentre.co.uk.

Tuesday, January 15. 2013

Via Wired

-----

By Noah Shachman

3-D printed organs. Brain chips providing superhuman abilities. Megacities, built from scratch. The U.S. intelligence community is taking a look at the world of 2030. And it is very, very sci-fi.

Every four or five years, the futurists at the National Intelligence Council take a stab at forecasting what the globe will be like two decades hence; the idea is to give some long-term, strategic guidance to the folks shaping America’s security and economic policies. (Full disclosure: I was once brought in as a consultant to evaluate one of the NIC’s interim reports.) On Monday, the Council released its newest findings, Global Trends 2030. Many of the prognostications are rather unsurprising: rising tides, a bigger data cloud, an aging population, and, of course, more drones. But tucked into the predictable predictions are some rather eye-opening assertions. Especially in the medical realm.

We’ve seen experimental prosthetics in recent years that are connected to the human neurological system. The Council says the link between man and machine is about to get way more cyborg-like. “As replacement limb technology advances, people may choose to enhance their physical selves as they do with cosmetic surgery today. Future retinal eye implants could enable night vision, and neuro-enhancements could provide superior memory recall or speed of thought,” the Council writes. “Brain-machine interfaces could provide ‘superhuman’ abilities, enhancing strength and speed, as well as providing functions not previously available.”

And if the machines can’t be embedded into the person, the person may embed himself in the robot. “Augmented reality systems can provide enhanced experiences of real-world situations. Combined with advances in robotics, avatars could provide feedback in the form of sensors providing touch and smell as well as aural and visual information to the operator,” the report adds. There’s no word about whether you’ll have to paint yourself blue to enjoy the benefits of this tech.

The Council’s futurists are less definitive about 3-D printing and other direct digital manufacturing processes. On one hand, they say that any changes brought about by these new ways of making things could be “relatively slow.” On the other, they rip a page out of Wired, comparing the emerging era of digital manufacturing to the “early days of personal computers and the internet.” Today, the machines may only be able to make simple objects. Tomorrow, that won’t be the case. And that shift will change not only manufacturing and electronics — but people, as well.

“By 2030, manufacturers may be able to combine some electrical components (such as electrical circuits, antennae, batteries, and memory) with structural components in one build, but integration with printed electronics manufacturing equipment will be necessary,” the Council writes. “Though printing of arteries or simple organs may be possible by 2030, bioprinting of complex organs will require significant technological breakthroughs.”

But not all of these biological developments will be good things, the Council notes. “Advances in synthetic biology also have the potential to be a double-edged sword and become a source of lethal weaponry accessible to do-it-yourself biologists or biohackers,” according to the report. Biology is becoming more and more like the open source software community, with “open-access repository of standardized and interchangeable building block or ‘biobrick’ biological parts that researchers can use” — for good or for bad. ”This will be particularly true as technology becomes more accessible on a global basis and, as a result, makes it harder to track, regulate, or mitigate bioterror if not ‘bioerror.’”

Some of the Council’s predictions may give a few of Washington’s more sensitive politicians a rash. Although the Council does allow for the possibility of a “decisive re-assertion of U.S. power,” the futurists seem pretty well convinced that America is, relatively speaking, on the decline and that China is on the ascent. In fact, the Council believes nation-states in general are losing their oomph, in favor of “megacities [that will] flourish and take the lead in confronting global challenges.” And we’re not necessarily talking New York or Beijing here; some of these megacities could be somehow “built from scratch.”

Unlike some Congressmen, the Council takes climate change as a given. Unlike many in the environmental movement, the futurists believe that the discovery of cheap ways to harvest natural gas are going to relegate renewables to bit-player status in the energy game.

But most of the findings are apolitical bets on which tech will leap out the furthest over the next 17 years. People can check back in 2030 to see if the intelligence agencies are right — that is, if you still call the biomodded cyborgs roaming the planet people.

Monday, April 02. 2012

-----

de Marion Wagner

A l’heure actuelle la demande en énergie croît plus vite que l’offre. Selon l’Agence internationale de l’énergie, à l’horizon 2030 les besoins de la planète seront difficiles à satisfaire, tous types d’énergies confondus. Il faudra beaucoup de créativité pour satisfaire la demande.

Vincent Schachter, directeur de la recherche et du développement pour les énergies nouvelles à Total commence son exposé sur la biologie de synthèse. “C’est important de préciser dans quel cadre nous travaillons”. Ses chercheurs redessinent le vivant. Ils s’échinent à mettre au point des organismes microscopiques, des bactéries, capables de produire de l’énergie.

En combinant ingénierie, chimie, informatique et biologie moléculaire, les scientifiques recréent la vie.

Ambition démiurgique

Aucune avancée scientifique n’a incarné tant de promesses : détourner des bactéries en usines biologiques capables de produire des thérapeutiques contre le cancer, des biocarburants ou des molécules capables de dégrader des substances toxiques.

Dans la salle Lamartine de l’Assemblée nationale ce 15 février, le parterre de spécialistes invités par l’Office parlementaire d’évaluation des choix scientifique et techniques (OPECST) est silencieux. L’audition publique intitulée Les enjeux de la biologie de synthèse s’attaque à cette discipline jeune, enjeu déjà stratégique. Geneviève Fioraso, députée de l’Isère, qui l’a organisée, confesse : “J’ai des collègues parlementaires à l’Office qui sont biologistes. Ils me disent qu’ils sont parfois dépassés par ce qui est présenté. Ce sont des questions très complexes d’un point de vue scientifique”.

L’Office, dont la mission est “d’informer le Parlement des conséquences des choix de caractère scientifique et technologique afin, notamment, d’éclairer ses décisions” est composé de parlementaires, députés et sénateurs. Dix-huit élus de chaque assemblée qui représentent proportionnellement l’équilibre politique du Parlement. Assistés d’un conseil scientifique ad hoc ils sont saisis des sujets scientifiques contemporains : la sûreté nucléaire en France, les effets sur la santé des perturbateurs endocriniens, les leçons à tirer de l’éruption du volcan Eyjafjöll…

Marc Delcourt, le PDG de la start-up Global Bioenergies, basée à Evry, prend la parole :

La biologie de synthèse, c’est créer des objets biologiques. Nous nous attachons à transformer le métabolisme de bactéries pour leur faire produire à partir de sucres une molécule jusqu’à maintenant uniquement issue du pétrole, et dont les applications industrielles sont énormes.

Rencontré quelques jours plus tard, Philippe Marlière, le cofondateur de l’entreprise, “s’excuse”. Il donne, lui, une définition “assez philosophique” de la biologie de synthèse : ” Pour moi c’est la discipline qui vise à faire des espèces biologiques, ou tout objet biologique, que la nature n’aurait pas pu faire. Ce n’est pas ‘qu’elle n’a pas fait’, c’est ‘qu’elle n’aurait pas pu faire. Il faut que ce soit notre gamberge qui change ce qui se passe dans le vivant”.

Ce bio-chimiste, formé à l’École Normale Supérieure, assume sans fard une ambition de démiurge, il s’agit de créer la vie de manière synthétique pour supplanter la nature. Il ajoute :

Je ne suis pas naturaliste, je ne fais pas partie des gens qui pensent que la nature est harmonieuse et bonne. Au contraire, la biologie de synthèse pose la nature comme imparfaite et propose de l’améliorer .

Aussi provoquant que cela puisse paraître c’est l’objectif affiché et en partie atteint par la centaine de chercheurs qui s’adonne à la discipline depuis 10 ans en France. Il reprend : “Aussi vaste que soit la diversité des gènes à la surface de la terre, les industriels se sont déjà persuadés que la biodiversité naturelle ne suffira pas à procurer l’ensemble des procédés dont ils auront besoin pour produire de manière plus efficace des médicaments ou des biocarburants. Il va falloir que nous nous retroussions les manches et que nous nous occupions de créer de la bio-diversité radicalement nouvelle, nous-mêmes.”

Biologiste-ingénieur

L’évolution sur terre depuis 3 milliard et demi d’années telle que décrite par Darwin est strictement contingente. La sélection naturelle, écrit le prix Nobel de médecine François Jacob dans Le jeu des possibles “opère à la manière d’un bricoleur qui ne sait pas encore ce qu’il va produire, mais récupère tout ce qui lui tombe sous la main, les objets les plus hétéroclites, bouts de ficelle, morceaux de bois, vieux cartons pouvant éventuellement lui fournir des matériaux […] D’une vieille roue de voiture il fait un ventilateur ; d’une table cassée un parasol. Ce genre d’opération ne diffère guère de ce qu’accomplit l’évolution quand elle produit une aile à partir d’une patte, ou un morceau d’oreille avec un fragment de mâchoire”.

Le hasard de l’évolution naturelle, combiné avec la nécessité de l’adaptation a sculpté un monde “qui n’est qu’un parmi de nombreux possibles. Sa structure actuelle résulte de l’histoire de la terre. Il aurait très bien pu être différent. Il aurait même pu ne pas exister du tout”. Philippe Marlière ajoute, laconique : “A posteriori on a toujours l’impression que les choses n’auraient pas pu être autrement, mais c’est faux, le monde aurait très bien pu exister sans Beethoven”.

Cliquer ici pour voir la vidéo.

Comprendre que l’évolution n’a ni but, ni projet. Et la science est sur le point de pouvoir mettre un terme au bricolage inopérant de l’évolution. Le biologiste, ici, est aussi ingénieur. A partir d’un cahier des charges il définit la structure d’un organisme pour lui faire produire la molécule dont il a besoin. Si la biologie de synthèse en est à ses balbutiements, elle est aussi une révolution culturelle.

Il s’agit désormais de créer de nouvelles espèces dont l’existence même est tournée vers les besoins de l’humanité. “La limite à ne pas toucher pour moi c’est la nature humaine. Je suis un opposant acharné au transhumanisme“, met tout de suite en garde le généticien.

A, T, G, C

Depuis que Francis Crick, James Watson et Rosalind Franklin ont identifié l’existence de l’ADN, l’acide désoxyribonucléique, en 1953, une succession de découvertes ont permis de modifier cet l’alphabet du vivant.

On sait désormais lire, répliquer, mais surtout créer un génome et ses gènes, soit en remplaçant certaines de ses parties, soit en le synthétisant entièrement d’après un modèle informatique. Les gènes, quatre bases azotées, A, T, G et C qui se succèdent le long de chacun des deux brins d’ADN pour former la fameuse double hélice, illustre représentation du vivant. Quatre molécules chimiques qui codent la vie : A, pour adénine, T pour thymine, G pour guanine, et C pour cytosine. Leur agencement détermine l’activité du gène, la ou les protéines pour lesquelles il code, qu’il crée. Les protéines, ensuite, déterminent l’action des cellules au sein des organismes vivants : produire des cheveux blonds, des globules blancs, ou des bio-carburants.

On peut à l’heure actuelle, en quelques clics, acheter sur Internet une base azotée pour 30 cents. Un gène de taille moyenne, chez la bactérie, coûte entre 300 et 500 €, il est livré aux laboratoires dans de petits tubes en plastique translucide. Là il est intégré à un génome qui va générer de nouvelles protéines, en adéquation avec les besoins de l’industrie et de l’environnement.

L’être humain est devenu ingénieur du vivant, il peut transformer de simples êtres unicellulaires, levures ou bactéries en de petites usines qu’il contrôle. C’est le bio-entrepreneur américain Craig Venter qui sort la discipline des laboratoires en annonçant en juin 2010 avoir crée Mycoplasma mycoides, une bactérie totalement artificielle “fabriquée à partir de quatre bouteilles de produits chimiques dans un synthétiseur chimique, d’après des informations stockées dans un ordinateur”.

Si la création a été saluée par ses pairs et les médias, certains s’attachent toutefois à souligner que sa Mycoplasma mycoides n’a pas été crée ex nihilo, puisque le génome modifié a été inséré dans l’enveloppe d’une bactérie naturelle. Mais la manipulation est une grande première.

Tour de Babel génétique

Philippe Marlière a posé devant lui un petit cahier, format A5, où après avoir laissé dériver son regard il prend quelques notes. “Il y a longtemps qu’on essaye de changer le vivant en profondeur. Moi c’est l’aspect chimique du truc qui m’intéresse : où faut-il aller piocher dans la table de Mandeleiev pour faire des organismes vivants ? Jusqu’où sont-ils déformables ? Jusqu’à quel point peut-on les lancer dans des mondes parallèles sur terre ?”. Il jette un coup d’œil à son Schweppes :

Prenez l’exemple de l’eau lourde. C’est une molécule d’eau qui se comporte pratiquement comme de l’eau, et on peut forcer des organismes vivants à y vivre et évoluer. Or il n’y a d’eau lourde nulle part dans l’univers, il n’y a que les humains qui savent la concentrer. On peut créer un microcosme complètement artificiel et être sûr que l’évolution qui a lieu là-dedans n’a pas eu lieu dans l’univers. C’est l’évolution dans des conditions qui n’auraient pas pu se dérouler sur terre, c’est intéressant. La biologie de synthèse est une forme radicale d’alter-mondialisme, elle consiste à dire que d’autres vies sont vraiment possibles, en les changeant de fond en comble.

Ce n’est pas une provocation feinte, ce n’est même pas une provocation. L’homme a à cœur d’être bien compris. Il s’agit de venir à bout de l’évolution darwinienne, pathétiquement coincée à un stade qui n’assure plus les besoins en énergie des 10 milliards d’humains à venir. Il faut pour ça réécrire la vie, son code. Innover dans l’alphabet de quatre lettres, A, C, G et T. Créer une nouvelle biodiversité. Condition sine qua non : ces mondes, le nôtre, le naturel, et le nouveau, l’artificiel, devraient cohabiter sans pouvoir jamais échanger d’informations. Il appelle ça la tour de Babel génétique, où les croisements entre espèces seraient impossibles.

“Les écologistes exagèrent souvent, mais ils mettent en garde contre les risques de dissémination génétique et ils ont raison. Les croisements entre espèces vont très loin. J’ai lu récemment que le chat et le serval sont inter-féconds”. Il estime de la main la hauteur du serval, un félin tacheté, proche du guépard, qui vit en Afrique. Un mètre de haut environ.

Par ailleurs il fallait être superstitieux pour imaginer que le pollen des OGM n’allait pas se disséminer. Le pollen sert à la dissémination génétique ! D’où notre projet, il s’agit de faire apparaître des lignées vivantes pour lesquelles la probabilité de transmettre de l’information génétique est nulle.

Le concept tient en une phrase :

“The farther, the safer : plus la vie artificielle est éloignée de celle que nous connaissons, plus les risques d’échanges génétiques entre espèces diminuent. C’est là qu’il y a le plus de brevets et d’hégémonie technologique à prendre.”

Il s’agit de modifier notre alphabet de 4 lettres, A, C, G et T, pour créer un nouvel ADN, le XNA, clé de la “xénobiologie”:

X pour Xeno, étranger, et biologie. Le sens de cet alphabet ne serait pas lisible par les organismes vivants, c’est ça le monde qu’on veut faire. C’est comme lancer un Spoutnik, c’est difficile. Mais comme disait Kennedy, ‘On ne va pas sur la lune parce que c’est facile, on y va parce que c’est difficile.’

Cliquer ici pour voir la vidéo.

Tuesday, March 27. 2012

-----

de Lloyd Alter

Everyday Science and Mechanics via Paleofuture/Public Domain

One of the benefits attributed to dome houses is that a sphere encloses the most volume for a given surface area. Of course much of that volume is useless, but that is another story. Back in 1934, Everyday Science and Mechanics suggested some other virtues of spheres: they roll. The Smithsonian's Paleofuture quotes them:

If spherical, the house of the future can be easily transported to its building lot, set in place, and the fixtures added. The shell is first pressed into shape; then windows are cut, and only a protective tire is need for moving.... Properly built-in fixtures would even stand such moving.

Just make sure there are not dishes in the kitchen cabinets.

Personal comment:

Very nice (& crazy) illustrations about past futures on this blog by the Smithsonian.

Thursday, March 22. 2012

-----

de Liv Siddall

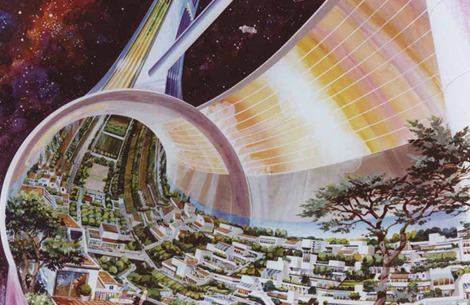

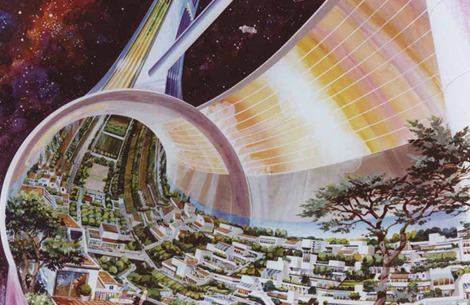

Ever sat at work daydreaming about living in space? Then you’ll be pleased to know that NASA has enormous teams working on space-habitation. In the likely case of us having to flee our planet, we’ll hopefully be able to whizz up to these pods where there are barbecues, golf, parks and suspension bridges waiting for us (Phew! Thank god they’ve got suspension bridges up there, I’d definitely miss those). Check out these insanely cool (though sadly rejected) designs for space houses from the 1970s and remember – these are not just musings, they are real designs, made by real NASA. (Read more)

www.settlement.arc.nasa.gov

Wednesday, January 04. 2012

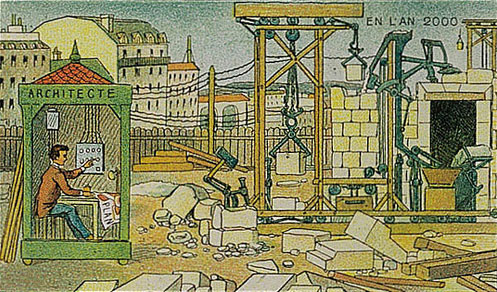

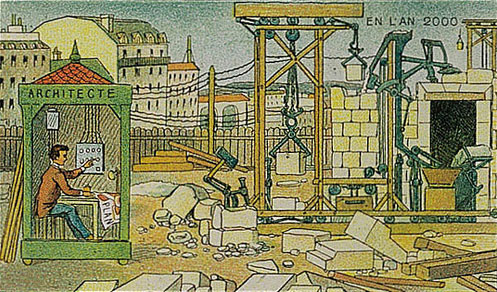

The future (years 2000) as seen by french illustrator Villemard in 1910:

Fits well with the previous post (sort of... digital fabrication with the architect-coder in command from its --remote-- location ... or "just" a regular construction with mechanical machines?)

You can see more images of Villemard here (obviously a lot of "flying stuff"^, but also some "video-telegraph", some "audio newspaper", "mail send via loudspeaker", etc.)

PS. Thank you Diana Malkosh for the tip.

|