Sticky Postings

All 242 fabric | rblg updated tags | #fabric|ch #wandering #reading

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Thursday, September 21. 2017

Timothy Morton, “the philosopher prophet of the Anthropocene” | #hyperobjects #climate

Note: Timothy Morton introducing his concept of "hyperobjects" and "object-oriented philosophy".

Via e-flux via The Guardian (June 17)

-----

Image of Thimothy Morton.

The Guardian has a longread on the US-based British philosopher Timothy Morton, whose work combines object-oriented ontology and ecological concerns. The author of the piece, Alex Blasdel, discusses how Morton's ideas have spread far and wide—from the Serpentine Gallery to Newsweek magazine—and how his seemingly bleak outlook has a silver lining. Here's an excerpt:

Morton means not only that irreversible global warming is under way, but also something more wide-reaching. “We Mesopotamians” – as he calls the past 400 or so generations of humans living in agricultural and industrial societies – thought that we were simply manipulating other entities (by farming and engineering, and so on) in a vacuum, as if we were lab technicians and they were in some kind of giant petri dish called “nature” or “the environment”. In the Anthropocene, Morton says, we must wake up to the fact that we never stood apart from or controlled the non-human things on the planet, but have always been thoroughly bound up with them. We can’t even burn, throw or flush things away without them coming back to us in some form, such as harmful pollution. Our most cherished ideas about nature and the environment – that they are separate from us, and relatively stable – have been destroyed.

Morton likens this realisation to detective stories in which the hunter realises he is hunting himself (his favourite examples are Blade Runner and Oedipus Rex). “Not all of us are prepared to feel sufficiently creeped out” by this epiphany, he says. But there’s another twist: even though humans have caused the Anthropocene, we cannot control it. “Oh, my God!” Morton exclaimed to me in mock horror at one point. “My attempt to escape the web of fate was the web of fate.”

The chief reason that we are waking up to our entanglement with the world we have been destroying, Morton says, is our encounter with the reality of hyperobjects – the term he coined to describe things such as ecosystems and black holes, which are “massively distributed in time and space” compared to individual humans. Hyperobjects might not seem to be objects in the way that, say, billiard balls are, but they are equally real, and we are now bumping up against them consciously for the first time. Global warming might have first appeared to us as a bit of funny local weather, then as a series of independent manifestations (an unusually torrential flood here, a deadly heatwave there), but now we see it as a unified phenomenon, of which extreme weather events and the disruption of the old seasons are only elements.

It is through hyperobjects that we initially confront the Anthropocene, Morton argues. One of his most influential books, itself titled Hyperobjects, examines the experience of being caught up in – indeed, being an intimate part of – these entities, which are too big to wrap our heads around, and far too big to control. We can experience hyperobjects such as climate in their local manifestations, or through data produced by scientific measurements, but their scale and the fact that we are trapped inside them means that we can never fully know them. Because of such phenomena, we are living in a time of quite literally unthinkable change.

Friday, May 12. 2017

The World’s Largest Artificial Sun Could Help Generate Clean Fuel | #conditioning #energy

Note: an amazing climatic device.

For clean energy experimentation here. Would have loved to have that kind of devices (and budget ;)) when we put in place Perpetual Tropical Sunshine !

-----

Don’t lean against the light switch at the Synlight building in Jülich, Germany—if you do, things might get rather hotter than you can cope with.

The new facility is home to what researchers at the German Aerospace Center, known as DLR, have called the “world's largest artificial Sun.” Across a single wall in the building sit a series of Xenon short-arc lamps—the kind used in large cinemas to project movies. But in a huge cinema there would be one lamp. Here, spread across a surface 45 feet high and 52 feet wide, there are 140.

When all those lamps are switched on and focused on the same 20 by 20 centimeter spot, they create light that’s 10,000 times more intense than solar radiation anywhere on Earth. At the center, temperatures reach over 3,000 °C.

The setup is being used to mimic large concentrated solar power plants, which use a field full of adjustable mirrors to focus sunlight into a small incredibly hot area, where it melts salt that is then used to create steam and generate electricity.

Researchers at DLR, though, think that a similar mirror setup could be used to power a high-energy reaction where hydrogen is extracted from water vapor. In theory, that process could supply a constant and affordable source of liquid hydrogen fuel—something that clean energy researchers continue to lust after, because it creates no carbon emissions when burned.

Trouble is, folks at DLR don’t quite yet know how to make it happen. So they built a laboratory rig to allow them to tinker with the process using artificial light instead of reflected sunlight—a setup which, as Gizmodo notes, uses the equivalent of a household's entire year of electricity during just four hours of operation, somewhat belying its green aspirations.

Of course, it’s far from the first project to aim to create hydrogen fuel cheaply: artificial photosynthesis, seawater electrolysis, biomass reactions, and many other projects have all tried—and so far failed—to make it a cost-effective exercise. So now it’s over to the Sun. Or a fake one, for now.

(Read more: DLR, Gizmodo, “World’s Largest Solar Thermal Power Plant Delivers Power for the First Time,” “A Big Leap for an Artificial Leaf,” "A New Source of Hydrogen for Fuel-Cell Vehicles")

Tuesday, October 04. 2016

L’Anthropocène et l’esthétique du sublime | #stupéfaction #bourgeoisie

Note: j'avais évoqué récemment cette idée du sublime dans le cadre d'un workshop à l'ECAL, avec pour invités Random International. Il s'agissait alors d'intervenir dans le cadre d'un projet de recherche où nous visions à développer des "contre-propositions" à l'expression actuelle de quelques-unes de nos infrastructures contemporaines, "douces" et "dures". Le "cloud computing" et les data-centers en particulier (le projet en question, en cours et dont le processus est documenté sur un blog: Inhabiting & Interfacing the Cloud(s)). Un projet conduit en collaboration avec Nicolas Nova de la HEAD - Genève

Tout cela s'était développé autour du sentiment d'une technologie, qui mettant aujourd'hui de nouveau "à distance" ses utilisateurs, contribuerait au développement de "croyances" (dimension "magique") et dans certains cas, à la résurgence du sentiment de "sublime", cette fois non plus lié aux puissances natutrelles "terrifiantes", mais aux technologies développées par l'homme. Je n'avais pas fait le lien avec cette thématique très actuelle de l'Anthropocène, que nous avions toutefois déjà commentée et pointée sur ce blog.

C'est fait dorénavant avec beaucoup de nuances par Jean-Baptiste Fressoz. Non sans souligner que "(...) cette opération esthétique, au demeurant très réussie, n’est pas sans poser problème car ce qui est rendu sublime ce n’est évidemment pas l’humanité, mais c’est, de fait, le capitalisme".

...

On peut aussi se souvenir qu'en 1990 déjà, Michel Serres écrivait dans son livre Le Contrat Naturel:

"Voici maintenant formée la contemporaine société, qu'on peut appeler deux fois mondiale: occupant toute la terre, solidaire comme un bloc, par ses interrelations croisées, elle ne dispose d'aucun reste, de recul ni de recours, ou planter sa tente et dans quel extérieur. Elle sait, d'autre part, construire et utiliser des moyens techniques aux dimensions spatiales, temporelles, énergétiques des phénomènes du monde. Notre puissance collective atteint donc les limites de notre habitat global. Nous commençons à ressembler à la Terre."

Texte que nous avions par ailleurs cité avec fabric | ch dans l'un de nos premiers projets, Réalité Recombinée, en 1998.

Via Mouvements (via Nicolas Nova)

-----

Par Jean-Baptiste Fressoz

Olafur Eliasson à la Tate Modern.

Pour Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, la force de l’idée d’Anthropocène n’est pas conceptuelle, scientifique ou heuristique : elle est avant tout esthétique. Dans cet article, l’auteur revient, pour en pointer les limites, sur les ressorts réactivés de cette esthétique occidentale et bourgeoise par excellence [note: le sublime], vilipendée par différents courants critiques. Il souligne qu’avant d’embrasser complètement l’Anthropocène, il faut bien se rappeler que le sublime n’est qu’une des catégories de l’esthétique, qui en comprend d’autres (le tragique, le beau…) reposant sur d’autres sentiments (l’harmonie, la douleur, l’amour…), peut-être plus à même de nourrir une esthétique du soin, du petit, du local dont l’agir écologique a tellement besoin.

Aussi sidérant, spectaculaire ou grandiloquent qu’il soit, le concept d’Anthropocène ne désigne pas une découverte scientifique [1]. Il ne représente pas une avancée majeure ou récente des sciences du système-terre. Nom attribué à une nouvelle époque géologique à l’initiative du chimiste Paul Crutzen, l’Anthropocène est une simple proposition stratigraphique encore en débat parmi la communauté des géologues. Faisant suite à l’Holocène (12 000 ans depuis la dernière glaciation), l’Anthropocène est marquée par la prédominance de l’être humain sur le système-terre. Plusieurs dates de départ et marqueurs stratigraphiques afférents sont actuellement débattus : 1610 (point bas du niveau de CO2 dans l’atmosphère causé par la disparition de 90% de la population amérindienne), 1830 (le niveau de CO2 sort de la fourchette de variabilité holocénique), 1945 date de la première explosion de la bombe atomique.

La force de l’idée d’Anthropocène n’est pas conceptuelle, scientifique ou heuristique : elle est avant tout esthétique. Le concept d’Anthropocène est une manière brillante de renommer certains acquis des sciences du système-terre. Il souligne que les processus géochimiques que l’humanité a enclenchés ont une inertie telle que la terre est en train de quitter l’équilibre climatique qui a eu cours durant l’Holocène. L’Anthropocène désigne un point de non retour. Une bifurcation géologique dans l’histoire de la planète Terre. Si nous ne savons pas exactement ce que l’Anthropocène nous réserve (les simulations du système-terre sont incertaines), nous ne pouvons plus douter que quelque chose d’importance à l’échelle des temps géologiques a eu lieu récemment sur Terre.

Le concept d’Anthropocène a cela d’intéressant, mais aussi de très problématique pour l’écologie politique, qu’il réactive les ressorts de l’esthétique du sublime, esthétique occidentale et bourgeoise par excellence, vilipendée par les critiques marxistes, féministes et subalternistes, comme par les postmodernes. Le discours de l’Anthropocène correspond en effet assez fidèlement aux canons du sublime tels que définis par Edmund Burke en 1757. Selon ce philosophe anglais conservateur, surtout connu pour son rejet absolu de 1789, l’expérience du sublime est associée aux sensations de stupéfaction et de terreur ; le sublime repose sur le sentiment de notre propre insignifiance face à une nature lointaine, vaste, manifestant soudainement son omnipuissance. Écoutons maintenant les scientifiques promoteurs de l’Anthropocène :

« L’humanité, notre propre espèce, est devenue si grande et si active qu’elle rivalise avec quelques-unes des grandes forces de la Nature dans son impact sur le fonctionnement du système terre […]. Le genre humain est devenu une force géologique globale [2] ».

La thèse de l’Anthropocène repose en premier lieu sur les quantités phénoménales de matière mobilisées et émises par l’humanité au cours des XIXe et XXe siècles. L’esthétique de la gigatonne de CO2 et de la croissance exponentielle renvoie à ce que Burke avait noté : « la grandeur de dimension est une puissante cause du sublime [3] », et, ajoute-t-il, le sublime demande « le solide et les masses mêmes [4] ». De manière plus précise, l’Anthropocène reporte le sublime de la vaste nature vers « l’espèce humaine ». Tout en jouant du sublime, il en renverse les polarités classiques : la terreur sacrée de la nature est transférée à une humanité colosse géologique.

Or, cette opération esthétique, au demeurant très réussie, n’est pas sans poser problème car ce qui est rendu sublime ce n’est évidemment pas l’humanité, mais c’est, de fait, le capitalisme. L’Anthropocène n’est certainement pas l’affaire d’une « espèce humaine », d’un « anthropos » indifférencié, ce n’est même pas une affaire de démographie : entre 1800 et 2000 la population humaine a été multipliée par sept, la consommation d’énergie par 50 et le capital, si on reprend les chiffres de Thomas Picketty, par 134 [5]. Ce qui a fait basculer la planète dans l’Anthropocène, c’est avant tout une vaste technostructure orientée vers le profit, une « seconde nature », faite de routes, de plantations, de chemins de fer, de mines, de pipelines, de forages, de centrales électriques, de marchés à terme, de porte-containers, de places financières et de banques et bien d’autres choses encore qui structurent les flux de matière et d’énergie à l’échelle du globe selon une logique structurellement inégalitaire. Bref, le changement de régime géologique est bien sûr le fait de « l’âge du capital [6] » bien plus que le fait de « l’âge de l’être humain » dont nous rebattent les récits dominants [7]. Le premier problème du sublime de l’Anthropocène est qu’il renomme, esthétise et surtout naturalise le capitalisme, dont la force se mesure dorénavant à l’aune des manifestations de la première nature – les volcans, la tectonique des plaques ou les variations des orbites planétaires – que deux siècles d’esthétique du sublime nous avaient appris à craindre mais aussi à révérer.

Au sublime de la quantité, l’Anthropocène ajoute le sublime géologique des âges et des éons, duquel il tire ses effets les plus saisissants. La thèse de l’Anthropocène nous dit en substance que les traces de notre âge industriel resteront pour des millions d’années dans les archives géologiques de la planète. Le fait d’ouvrir une nouvelle époque taillée à la mesure de l’être humain signifie que c’est à l’échelle des temps géologiques seulement que l’on peut identifier des événements agissant avec autant de force sur la planète que nous-mêmes : le taux de dioxyde de carbone en 2015 est sans précédent depuis trois millions d’années, le taux actuel d’extinction des espèces, depuis 65 millions d’années, l’acidité des océans, depuis 300 millions d’années, etc. Ce que nous vivons n’est pas une simple « crise environnementale », mais une révolution géologique d’origine humaine. Loin de constituer un cours extérieur, impavide et gigantesque, le temps de la Terre est devenu commensurable au temps de l’agir humain. En deux siècles tout au plus, l’humanité a altéré la dynamique du système-terre pour l’éternité ou presque. « Tout ce qui fait transition n’excite aucune terreur [8] » écrivait Burke. Le discours de l’Anthropocène cultive cette esthétique de la soudaineté, de la bifurcation et de l’événement. Le sublime de l’Anthropocène réside précisément dans cette rencontre extraordinaire : deux siècles d’activité humaine, une durée infime, quasi-nulle au regard de l’histoire terrienne, auront suffi à provoquer une altération comparable au grand bouleversement de la fin du Mésozoïque il y a 65 millions d’années.

La troisième source du sublime anthropocénique est le sublime de la violence souveraine de la nature, celle des tremblements de terre, des tempêtes et des ouragans. Les promoteur·rice·s de l’Anthropocène mobilisent volontiers le sublime romantique des ruines, des civilisations disparues et des effondrements : « Les moteurs de l’Anthropocène pourraient bien menacer la viabilité de la civilisation contemporaine et peut-être même l’existence d’homo sapiens [9] ». Le succès artistique et médiatique du concept repose sur la « jouissance douloureuse », sur le « plaisir négatif » dont parle Burke :

« Nous jouissons à voir des choses que, bien loin de les occasionner, nous voudrions sincèrement empêcher… Je ne pense pas qu’il existe un·e ho·femme assez scélérat·e· pour désirer [que Londres] fût renversée par un tremblement de terre… Mais supposons ce funeste accident arrivé, quelle foule accourrait de toute part pour contempler ses ruines [10] ».

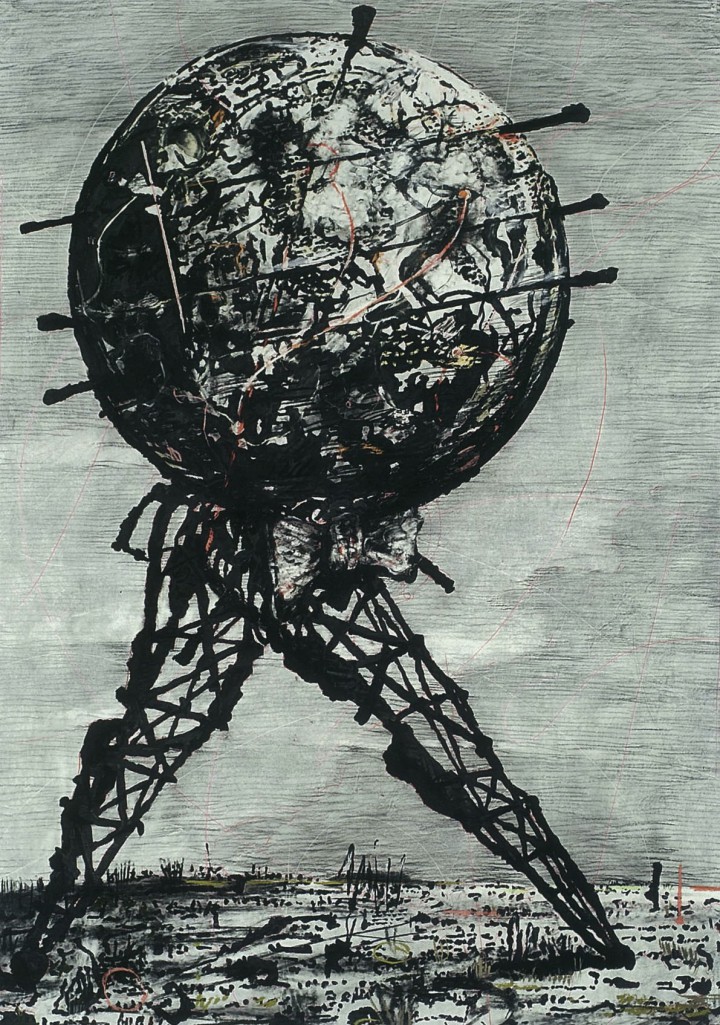

William Kentridge

L’Anthropocène s’appuie sur une culture de l’effondrement propre aux nations occidentales, qui, depuis deux siècles, admirent leur puissance en fantasmant les ruines de leur futur. L’Anthropocène joue des mêmes ressorts psychologiques que le plaisir pervers des décombres déjà décrit par Burke et qui nourrit la vogue actuelle du tourisme des catastrophes de Tchernobyl à ground zero.

La violence de l’Anthropocène est aussi celle de la science hautaine et froide qui nomme les époques et définit notre condition historique. Violence, tout d’abord, de son diagnostic irrévocable : « toi qui entre dans l’Anthropocène abandonne tout espoir » semblent nous dire les savant·e·s. Violence ensuite de la naturalisation, de la « mise en espèce » des sociétés humaines : les statistiques globales de consommation et d’émissions compactent les mille manières d’habiter la terre en quelques courbes, effaçant par la même l’immense variation des responsabilités entre les peuples et les classes sociales. Violence enfin du regard géologique tourné vers nous-mêmes, jaugeant toute l’histoire (empires, guerres, techniques, hégémonies, génocides, luttes, etc.) à l’aune des traces sédimentaires laissées dans la roche. Le géologue de l’Anthropocène est plus effroyable encore que l’ange de l’histoire de Walter Benjamin qui, là même où nous voyions auparavant progrès, ne voyait que catastrophe et désastre : lui n’y voit que fossiles et sédiments.

Que le sublime soit l’esthétique cardinale de l’Anthropocène n’est absolument pas fortuit : sublime et géologie se sont épaulés tout au long de leur histoire. En 1674, Nicolas Boileau traduit en français le traité de Longinus sur le sublime (1er siècle après J.-C.) introduisant ainsi cette notion dans l’Europe lettrée. Mais c’est seulement au milieu du XVIIIe siècle, après que la passion des montagnes et l’intérêt pour la géologie se sont cristallisés dans les classes supérieures, que la « grande nature » devient un objet de sublime [11]. Partis pour leur « grand tour », sur le chemin de l’Italie, les jeunes Anglais·es fortuné·e·s rencontrent en effet la chaîne des Alpes, ses pics vertigineux, ses glaciers terrifiants et ses panoramas immenses. Dans les récits de grands tours, l’expérience de l’effroi face à la nature représente le prix à payer pour goûter la beauté des trésors culturels de l’Italie. Le sublime joue ici un rôle de distinction : être capable de prendre du plaisir en contemplant les glaciers, ou les rochers arides, permettait aux touristes anglais·es de se différencier des guides et des paysan·e·s montagnard·e·s qui n’y voyaient que dangers et terres incultes. Mais c’est évidemment le tremblement de terre de Lisbonne de 1755 qui fournit le véritable coup d’envoi des réflexions sur le sublime : Burke, qui publie son traité l’année suivante, fait référence à la passion esthétique des décombres et des ruines qui saisit alors l’Europe entière. La même année, Emmanuel Kant publie également un court ouvrage sur le tremblement de terre de Lisbonne et, dans son essai ultérieur sur le sublime, il définit ce dernier comme un « plaisir négatif » pouvant procéder de deux manières : le sublime mathématique ressenti devant l’immensité de la nature (l’espace étoilé, l’océan etc.) et le « sublime dynamique » procuré par la violence de la nature (tornade, volcan, tremblement de terre).

Le sublime de l’Anthropocène, et sa mise en scène d’une humanité devenue force tellurique signe la rencontre historique du sublime naturel du XVIIIe siècle et du sublime technologique des XIXe et XXe siècles. Avec l’industrialisation de l’Occident, la puissance de la seconde nature fait l’objet d’une intense célébration esthétique. Le sublime transféré à la technique jouait un rôle central dans la diffusion de la religion du progrès : les gares, les usines et les gratte-ciels en constituaient les harangues permanentes [12]. Dès cette époque, l’idée d’un monde traversé par la technique, d’une fusion entre première et seconde natures fait l’objet de réflexions et de louanges. On s’émerveille des ouvrages d’art matérialisant l’union majestueuse des sublimes naturel et humain : viaducs enjambant les vallées, tunnels traversant les montagnes, canaux reliant les océans, etc. L’idée d’un globe remodelé pour les besoins de l’être humain et fertilisé par la technique constitue une trope classique du positivisme depuis Saint-Simon au moins, qui, dès 1820, écrivait :

« l’objet de l’industrie est l’exploitation du globe, c’est-à-dire l’appropriation de ses produits aux besoins de l’homme, et comme, en accomplissant cette tâche, elle modifie le globe, le transforme, change graduellement les conditions de son existence, il en résulte que par elle, l’homme participe, en dehors de lui-même en quelque sorte, aux manifestations successives de la divinité, et continue ainsi l’œuvre de la création. De ce point de vue, l’Industrie devient le culte [13] ».

De manière plus précise, l’Anthropocène s’inscrit dans une version du sublime technologique reconfigurée par la guerre froide. Il prolonge la vision spatiale de la planète produite par le système militaro-industriel américain, une vision déterrestrée de la Terre saisie depuis l’espace comme un système que l’on pourrait comprendre dans son entièreté, un « spaceship earth » dont on pourrait maîtriser la trajectoire grâce aux nouveaux savoirs sur le système-terre [14]. Le risque est que l’esthétique de l’Anthropocène nourrisse davantage l’hubris d’une géo-ingénierie brutale qu’un travail patient, à la fois modeste et ambitieux d’involution et d’adaptation du social. Pour mémoire, la géo-ingénierie désigne un ensemble de techniques visant à modifier artificiellement le pouvoir réfléchissant de l’atmosphère terrestre pour contrecarrer le réchauffement climatique. Cela peut constituer par exemple à injecter du dioxyde de soufre dans la haute atmosphère afin de réfléchir une partie du rayonnement solaire vers l’espace. L’échec des gouvernements à obtenir un accord international contraignant et ambitieux a contribué à mettre en avant la géo-ingénierie, en tant que « plan B ». Ces techniques potentiellement très risquées pourraient donc soudainement s’imposer en cas « d’urgence climatique ».

Pour ses promoteur·rice·s, l’Anthropocène est une révélation, un éveil, un changement de paradigme désorientant soudainement les représentations vulgaires du monde.

« Par le passé, du fait de la science, l’humanité a dû faire face à de profondes remises en cause de leurs systèmes de croyance. Un des exemples les plus important est la théorie de l’évolution… Le concept d’anthropocène pourrait susciter une réaction hostile similaire à celle que Darwin a produite [15] ».

On retrouve ici le trope romantique du·de la savant·e· payant de sa personne pour lutter contre la foule hostile. En se coupant ainsi du passé et de la décence environnementale commune, en rejetant comme dépassés les savoirs environnementaux qui le précèdent ainsi que les luttes sociales que ces savoirs ont nourries, l’Anthropocène dépolitise l’histoire longue de la destruction de la planète. Avant on ignorait les conséquences globales de l’agir humain, maintenant l’on sait, et, bien entendu, maintenant l’on peut agir. La prétention à la nouveauté des savoirs sur la Terre est aussi une prétention des savants à agir sur celle-ci. Ce n’est pas un hasard si l’inventeur du mot Anthropocène, le prix Nobel de chimie Paul Crutzen, est aussi l’un des avocat·e·s des techniques de géo-ingénierie. À l’Anthropocène inconscient issu de la révolution industrielle succéderait enfin le « bon Anthropocène » éclairé par les savoirs du système-terre. Comme toute forme de scientisme, l’esthétique de l’Anthropocène anesthésie le politique : les « expert·e·s », les autorités vont « faire quelque chose ».

Les expériences du sublime sont toujours à replacer dans un contexte historique et politique particulier. Elles renvoient à des émotions dépendantes des conditions culturelles, naturelles ou technologiques de chaque époque et ce sont ces conditions qui en fournissent les clés de compréhension politique. De la fin du XVIIIe siècle à la fin du siècle suivant, le sublime d’une nature violente et abstraite permettait aux classes bourgeoises urbaines de goûter à la violence de la nature, tout en étant relativement protégées de ses manifestations et de relativiser les dangers bien réels d’un mode de vie technologique et urbain. L’art du sublime nourrissait également le fantasme d’une nature immense et inépuisable au moment précis où l’impérialisme en exploitait les derniers recoins. Dans une culture prenant au sérieux le projet de maîtrise technique de la nature, l’esthétique du sublime fournissait aussi un plaisir légèrement coupable. Enfin, selon le critique marxiste Terry Eagleton, le sublime correspondait aux impératifs esthétiques du capitalisme naissant : contre l’esthétique émolliente du beau, risquant de transformer le sujet bourgeois en sensualiste décadent, le sublime réénergisait le sujet capitaliste comme exploiteur·se ou comme pourvoyeur de travail. Le beau devient à la fin du XVIIIe siècle l’harmonieux, le non-productif, le doux et le féminin ; le sublime : l’effort, le danger, la souffrance, l’élevé, le majestueux et le masculin. Au fond, le sublime, nous dit Eagleton, contenait la menace que la beauté faisait peser sur la productivité [16].

Au début des années 2000, le sublime de l’Anthropocène occupe également une fonction idéologique. Alors que les classes intellectuelles se convertissent au souci écologique, alors qu’elles rejettent les idéaux modernistes de maîtrise de la nature comme has been, alors qu’elles proclament « la fin des grands récits », la fin du progrès, de la lutte des classes, etc., l’Anthropocène procure le frisson coupable d’un nouveau récit sublime. Sur un fond d’agnosticisme quant au futur, l’Anthropocène paraît donner un nouvel horizon grandiose à l’humanité tout entière : prendre en charge collectivement le destin d’une planète. Dans le contexte idéologique terne de l’écologie politique, du développement durable et de la précaution, penser le mouvement d’une humanité devenue force tellurique paraît autrement plus excitant que penser l’involution d’un système économique. Au fond le sublime de l’Anthropocène rejoue assez exactement la scène finale du chef-d’œuvre de Stanley Kubrick, 2001 l’Odyssée de l’espace : l’embryon stellaire contemplant la terre figurant parfaitement l’avènement d’un agent géologique conscient, d’un corps planétaire réflexif. Et c’est bien pour cela que l’Anthropocène fait tressaillir théoricien·ne·s, philosophes et artistes en herbe : il semble désigner un événement métaphysique intéressant.

Pour l’écologie politique contemporaine, l’esthétique sublime de l’Anthropocène pose pourtant problème : en mettant en scène l’hybridation entre première et seconde natures, elle réénergise l’agir technologique des cold warriors (la géo-ingénierie) ; en déconnectant l’échelle individuelle et locale de ce qui importe vraiment (l’humanité force tellurique et les temps géologiques), elle produit sidération et cynisme (no future) ; enfin l’Anthropocène, comme tout autre sublime, est sujet à la loi des rendements décroissants : une fois que l’audience est préparée et conditionnée, son effet s’émousse. En ce sens, désigner une œuvre d’art comme « art de l’Anthropocène » serait absolument fatale à son efficacité esthétique. Le risque est que l’écologie du sublime soit alors appelée à une surenchère permanente, semblable en cela à la course à l’avant-garde dans l’art contemporain. Avant d’embrasser complètement l’Anthropocène, il faut bien se rappeler que le sublime n’est qu’une des catégories de l’esthétique, qui en comprend bien d’autres (le tragique, le beau, le pittoresque…) reposant sur d’autres sentiments (l’harmonie, l’ataraxie, la tristesse, la douleur, l’amour), qui sont peut-être plus à même de nourrir une esthétique du soin, du petit, du local, du contrôle, de l’ancien et de l’involution dont l’agir écologique a tellement besoin.

[1] Cet article reprend sous une forme modifiée un texte déjà paru dans le catalogue de l’exposition Sublime. Les tremblements du monde, Centre Pompidou-Metz, Metz, Centre Pompidou-Metz, 2016.

[2] W. Steffen, J. Grinevald, P. Crutzen, J. McNeill, « The Anthropocene : conceptual and historical perspectives », Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society A, 369, 2011, p. 842–867.

[3] E. Burke, Recherche philosophique sur l’origine de nos idées du sublime et du beau, Paris, Pichon, 1803 (1757), p. 129.

[4] Ibid., p. 225.

[5] T. Piketty, Le capital au XXIe siècle, Paris, Seuil, 2013.

[6] E. Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital : 1848-1975, London, Weindefeld, 1975.

[7] Voir le chapitre « capitalocène » de la nouvelle édition de C. Bonneuil, J.-B. Fressoz, L’événement Anthropocène. La terre, l’histoire et nous, Paris, Seuil, 2016.

[8] E. Burke, op. cit. p. 151.

[9] W. Steffen et al., art. cit.

[10] E. Burke, op. cit., p. 85.

[11] M. Hope Nicholson, Mountain gloom and mountain glory: The development of the aesthetics of the infinite, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1959.

[12] D. Nye, American technological sublime, Cambridge (MA), MIT Press, 1994.

[13] Saint-Simon, Doctrine de Saint-Simon, t. 2, Paris, Aux Bureaux de l’Organisateur, 1830, p. 219.

[14] C. Bonneuil, J.-B. Fressoz, op. cit. ; S. Grevsmühl, La Terre vue d’en haut. L’invention de l’environnement global, Paris, Seuil, 2014.

[15] W. Steffen et al., art. cit.

[16] Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic, Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1990.

Related Links:

Monday, October 07. 2013

Building Cities that Think Like Planets

-----

This essay is adapted from Marina Alberti Cities as Hybrid Ecosystems (Forthcoming) and from Marina Alberti “Anthropocene City”, forthcoming in The Anthropocene Project by the Deutsche Museum Special Exhibit 2014-1015

Cities face an important challenge: they must rethink themselves in the context of planetary change. What role do cities play in the evolution of Earth? From a planetary perspective, the emergence and rapid expansion of cities across the globe may represent another turning point in the life of our planet. Earth’s atmosphere, on which we all depend, emerged from the metabolic process of vast numbers of single-celled algae and bacteria living in the seas 2.3 billion years ago. These organisms transformed the environment into a place where human life could develop. Adam Frank, an Astrophysicist at the University of Rochesters, reminds us that the evolution of life has completely changed big important characteristics of the planet (NPR 13.7: Cosmos & Culture, 2012). Can humans now change the course of Earth’s evolution? Can the way we build cities determine the probability of crossing thresholds that will trigger non-linear, abrupt change on a planetary scale (Rockström et al 2009)?

For most of its history, Earth has been relatively stable, and dominated primarily by negative feedbacks that have kept it from getting into extreme states (Lenton and Williams 2013). Rarely has the earth experienced planetary-scale tipping points or system shifts. But the recent increase in positive feedback (i.e., climate change), and the emergence of evolutionary innovations (i.e. novel metabolisms), could trigger transformations on the scale of the Great Oxidation (Lenton and Williams 2013). Will we drive Earth’s ecosystems to unintentional collapse? Or will we consciously steer the Earth towards a resilient new era?

In my forthcoming book, Cities as Hybrid Ecosystems, I propose a co-evolutionary paradigm for building a science of cities that “think like planets” (see the Note at the bottom)— a view that focuses both on unpredictable dynamics and experimental learning and innovation in urban ecosystems. In the book I elaborate on some concepts and principles of design and planning that can emerge from such a perspective: self-organization, heterogeneity, modularity, feedback, and transformation.

How can thinking on a planetary scale help us understand the place of humans in the evolution of Earth and guide us in building a human habitat of the “long now”?

Planetary Scales

Humans make decisions simultaneously at multiple time and spatial scales, depending on the perceived scale of a given problem and scale of influence of their decision. Yet it is unlikely that this scale extends beyond one generation or includes the entire globe. The human experience of space and time has profound implications for our understanding of world phenomena and for making long- and short-term decisions. In his book What time is this place, Kevin Lynch (1972) eloquently told us that time is embedded in the physical world that we inhabit and build. Cities reflect our experience of time, and the way we experience time affects the way we view and change the environment. Thus our experience of time plays a crucial role in whether we succeed in managing environmental change. If we are to think like a planet, the challenge will be to deal with scales and events far removed from everyday human experience. Earth is 4.6 billion years old. That’s a big number to conceptualize and account for in our individual and collective decisions.

Thinking like a planet implies expanding the time and spatial scales of city design and planning, but not simply from local to global and from a few decades to a few centuries. Instead, we will have to include the scales of the geological and biological processes on which our planet operates. Thinking on a planetary scale implies expanding the idea of change. Lynch (1972) reminds us that “the arguments of planning all come down to the management of change.” But what is change?

Human experience of change is often confined to fluctuations within a relatively stable domain. However Planet Earth has displayed rare but abrupt changes and regime shifts in the past. Human experience of abrupt change is limited to marked changes in regional system dynamics, such as altered fire regimes, and extinctions of species. Yet, since the Industrial Revolution, humans have been pushing the planet outside a stability domain. Will human activities trigger such a global event? We can’t answer that, as we don’t understand enough about how regime shifts propagate across scales, but emerging evidence does suggest that if we continue to disrupt ecosystems and climate we face an increasing risk of crossing those thresholds that keep the earth in a relatively stable domain. Until recently our individual behaviors and collective institutions have been shaped primarily by change that we can envision relatively easily on a human time scale. Our behaviors are not tuned to the slow and imperceptible but systematic changes that can drive dramatic shifts in Earth’s systems.

Planetary shifts can be rapid: the glaciation of the Younger Dryas (abrupt climatic change resulting in severe cold and drought) occurred roughly 11,500 years ago, apparently over only a few decades. Or, it can unfold slowly: the Himalayas took over a million years to form. Shifts can emerge as the results of extreme events like volcanic eruptions, or relatively slow processes, like the movement of tectonic plates. Though we still don’t completely understand the subtle relationship between local and global stability in complex systems, several scientists hypothesize that the increasing complexity and interdependence of socio-economic networks can produce ‘tipping cascades’ and ‘domino dynamics’ in the Earth’s system, leading to unexpected regime shifts (Helbing 2013, Hughes et al 2013).

Planetary Challenges and Opportunities

A planetary perspective for envisioning and building cities that we would like to live in—cities that are livable, resilient, and exciting—provides many challenges and opportunities. To begin, it requires that we expand the spectrum of imaginary archetypes. Current archetypes reflect skewed and often extreme simplifications of how the universe works, ranging from biological determinism to techno-scientific optimism. At best they represent accurate but incomplete accounts of how the world works. How can we reconcile the messages contained in the catastrophic versus optimistic views of the future of Earth? And, how can we hold divergent explanations and arguments as plausibly true? Can we imagine a place where humans have co-evolved with natural systems? What does that world look like? How can we create that place in the face of limited knowledge and uncertainty, holding all these possible futures as plausible options?

Futures Archetypes. Credits: Upper left: 17th street canal, David Grunfeld Landov Media; Upper right: Qunli National Urban Wetland, Turenscape; Lower left: Hurricane Katrina – NOAA; Lower right: EDITT tower, Hamzah & Yeang

The concept of “planetary boundaries” offers a framework for humanity to operate safely on a planetary scale. Rockström et al (2009) developed the concept of planetary boundaries to inform us about the levels of anthropogenic change that can be sustained so we can avoid potential planetary regime shifts that would dramatically affect human wellbeing. The concept does not imply, and neither rules out, planetary-scale tipping points associated with human drivers. Hughes et al (2013) do address some the misconception surrounding planetary-scale tipping points that confuses a system’s rate of change with the presence or absence of a tipping point. To avoid the potential consequences of unpredictable planetary-scale regime shifts we will have to shift our attention towards the drivers and feedbacks rather than focus exclusively on the detectable system responses. Rockström et al (2009) identify nine areas that are most in need of set planetary boundaries: climate change; biodiversity loss; input of nitrogen and phosphorus in soils and waters; stratospheric ozone depletion; ocean acidification; global consumption of freshwater; changes in land use for agriculture; air pollution; and chemical pollution.

A different emphasis is proposed by those scientists who have advanced the concept of planetary opportunities: solution-oriented research to provide realistic, context-specific pathways to a sustainable future (DeFries et al. 2012). The idea is to shift our attention to how human ingenuity can expand the ability to enhance human wellbeing (i.e. food security, human health), while minimizing and reversing environmental impacts. The concept is grounded in human innovation and the human capacity to develop alternative technologies, implement “green” infrastructure, and reconfigure institutional frameworks. The potential opportunities to explore solution-oriented research and policy strategies are amplified in an urbanizing planet, where such solutions can be replicated and can transform the way we build and inhabit the Earth.

Imagining a Resilient Urban Planet

While these different images of the future are both plausible and informative, they speak about the present more than the future. They all represent an extension of the current trajectory as if the future would unfold along the path of our current way of asking questions, and our way of understanding and solving problems. Yes, these perspectives do account for uncertainty but it is defined by the confidence intervals around this trajectory. Both stories are grounded in the inevitable dichotomies of humans and nature, and technology vs. ecology. These views are at best an incomplete account of what is possible: they reflect a limited ability to imagine the future beyond such archetypes. Why can we imagine smart technologies and not smart behaviors, smart institutions, and smart societies? Why think only of technology and not of humans and their societies that co-evolve with Earth?

Understanding the co-evolution of human and natural systems is key to build a resilient society and transform our habitat. One of the greatest questions in biology today is whether natural selection is the only process driving evolution and what the other potential forces might be. To understand how evolution constructs the mechanisms of life, molecular biologists would argue that we also need to understand the self-organization of genes governing the evolution of cellular processes and influencing evolutionary change (Johnson and Kwan Lam 2010).

To function, life on Earth depends on the close cooperation of multiple elements. Biologists are curious about the properties of complex networks that supply resources, process waste, and regulate the system’s functioning at various scales of biological organization. West et al. (2005) propose that natural selection solved this problem by evolving hierarchical fractal-like branching. Other characteristics of evolvable systems are flexibility (i.e. phenotypic plasticity), and novelty. This capacity for innovation is an essential precondition for any system to function. Gunderson and Holling (2002) have noted that if systems lack the capacity for innovation and novelty, they may become over-connected and dynamically locked, unable to adapt. To be resilient and evolve, they must create new structures and undergo dynamic change. Differentiation, modularity, and cross-scale interactions of organizational structures have been described as key characteristics of systems that are capable of simultaneously adapting and innovating (Allen and Holling 2010).

To understand coevolution of human-natural systems will require advancement in the evolution and social theories that explain how complex societies and cooperation have evolved. What role does human ingenuity play? In Cities as Hybrid Ecosystems I propose that coupled human-natural systems are not governed only by either natural selection or human ingenuity alone, but by hybrid processes and mechanisms. It is their hybrid nature that makes them unstable and at the same time able to innovate. This novelty of hybrid systems is key to reorganization and renewal. Urbanization modifies the spatial and temporal variability of resources, creates new disturbances, and generates novel competitive interactions among species. This is particularly important because the distribution of ecological functions within and across scales is key to the system being able to regenerate and renew itself (Peterson et al. 1998).

The city that thinks like a planet: What does it look like?

In this blog article I have ventured to pose this question, but I will not venture to provide an answer. In fact no single individual can do that. The answer resides in the collective imagination and evolving behaviors of people of diverse cultures who inhabit a diversity of places on the planet. Humanity has the capacity to think in the long term. Indeed, throughout history, people in societies faced with the prospect of deforestation, or other environmental changes, have successfully engaged in long-term thinking, as Jared Diamond (2005) reminds us: consider Tokugawa shoguns, Inca emperors, New Guinea highlanders, or 16th-century German landowners. Or, more recently, the Chinese. Many countries in Europe, and the United States, have dramatically reduced their air pollution and meanwhile increased their use of energy and combustion of fossil fuels. Humans have the intellectual and moral capacity to do even more when tuned into challenging problems and engaged in solving them.

A city that thinks like a planet is not built on already set design solutions or planning strategies. Nor can we assume that the best solution would work equally well across the world regardless of place and time. Instead, such a city will be built on principles that expand its drawing board and collaborative action to include planetary processes and scales, to position humanity in the evolution of Earth. Such a view acknowledges the history of the planet in every element or building block of the urban fabric, from the building to the sidewalk, from the back yard to the park, from the residential street to the highway. It is a view that is curious about understanding who we are and about taking advantage of the novel patterns, processes, and feedbacks that emerge from human and natural interactions. It is a city grounded in the here and the now and simultaneously in the different time and spatial scales of human and natural processes that govern the Earth. A city that thinks like a planet is simultaneously resilient and able to change.

How can such a perspective guide decisions in practice? Urban planners and decision makers, making strategic decisions and investments in public infrastructure, want to know whether certain generic properties or qualities of a city’s architecture and governance could predict its capacity to adapt and transform itself. Can such a shift in perspective provide a new lens, a new way to interpret the evolution of human settlements, and to support humans in successfully adapting to change? Evidence emerging from the study of complex systems points to their key properties that expand adaptation capacity while enabling them to change: self organization, heterogeneity, modularity, redundancy, and cross-scale interactions.

A co-evolutionary perspective shifts the focus of planning towards human-natural interactions, adaptive feedback mechanisms, and flexible institutional settings. Instead of predefining “solutions,” that communities must implement, such perspective focuses on understanding the ‘rules of the game’, to facilitate self-organization and careful balance top-down and bottom-up managements strategies (Helbing 2013). Planning will then rely on principles that expand heterogeneity of forms and functions in urban structures and infrastructures that support the city. They support modularity (selected as opposed to generalized connectivity) to create interdependent decentralized systems with some level of autonomy to evolve.

In cities across the world, people are setting great examples that will allow for testing such hypotheses. Human perception of time and experience of change is an emerging key in the shift to a new perspective for building cities. We must develop reverse experiments to explore what works, what shifts the time scale of individual and collective behaviors. Several Northern European cities have adopted successful strategies to cut greenhouse gases, and combined them with innovative approaches that will allow them to adapt to the inevitable consequences of climate change. One example is the Copenhagen 2025 Climate Plan. It lays out a path for the city to become the first carbon-neutral city by 2025 through efficient zero-carbon mobility and building. The city is building a subway project that will place 85 percent of its inhabitants within 650 yards of a Metro station. Nearly three-quarters of the emissions reductions will come as people transition to less carbon-intensive ways of producing heat and electricity through a diverse supply of clean energy: biomass, wind, geothermal, and solar. Copenhagen is also one of the first cities to adopt a climate adaptation plan to reduce its vulnerability to the extreme storm events and rising seas expected in the next 100 years.

In the Netherlands, alternative strategies are being explored to allow people to live with the inevitable floods. These strategies involve building on water to develop floating communities and engineering and implementing adaptive beach protections that take advantage of natural processes. The experimental Sand Motor project uses a combination of wind, waves, tides, and sand to replenish the eroded coasts. The Dutch Rijkswaterstaat and the South Holland provincial authority placed a large amount of sand in an artificial 1 km long and 2 km wide peninsula into the sea, allowing for the wave and currents to redistribute it and build sand dunes and beaches to protect the coast over time.

New York is setting an example for long-term planning by combining adaptation and transformation strategies into its plan to build a resilient city, and Mayor Michael Bloomberg has outlined a $19.5 billion plan to defend the city against rising seas. In many rapidly growing cities of the Global South, similar leadership is emerging. For example, Johannesburg which adopted one of the first climate change adaptation plan, and so have Durban and Cape Town, in South Africa and Quito, Equador, along with Ho Chi Minh City Vietnam, where a partnership with the City of Rotterdam Netherlands has been established to develop a resilience strategy.

To think like a planet and explore what is possible we may need to reframe our questions. Instead of asking what is good for the planet, we must ask what is good for a planet inhabited by people. What is a good human habitat on Earth? And instead of seeking optimal solutions, we should identify principles that will inform the diverse communities across the world. The best choices may be temporary, since we do not fully understand the mechanisms of life, nor can we predict the consequences of human action. They may very well vary with place and depend on their own histories. But human action may constrain the choices available for life on earth.

Scenario Planning

Scenario planning offers a systematic and creative approach to thinking about the future by letting scientists and practitioners expand old mindsets of ecological sciences and decision making. It provides a tool we can use to deal with the limited predictability of changes on the planetary scale and to support decision-making under uncertainty. Scenarios help bring the future into present decisions (Schwartz 1996). They broaden perspectives, prompt new questions, and expose the possibilities for surprise.

Scenarios have several great features. We expect that they can shift people’s attention toward resilience, redefine decision frameworks, expand the boundaries of predictive models, highlight the risks and opportunities of alternative future conditions, monitor early warning signals, and identify robust strategies (Alberti et al 2013)

A fundamental objective of scenario planning is to explore the interactions among uncertain trajectories that would otherwise be overlooked. Scenarios highlight the risks and opportunities of plausible future conditions. The hypothesis is that if planners and decision makers look at multiple divergent scenarios, they will engage in a more creative process for imagining solutions that would be invisible otherwise. Scenarios are narratives of plausible futures; they are not predictions. But they are extremely powerful when combined with predictive modeling. They help expand boundary conditions and provide a systematic approach we can use to deal with intractable uncertainties and assess alternative strategic actions. Scenarios can help us modify model assumptions and assess the sensitivities of model outcomes. Building scenarios can help us highlight gaps in our knowledge and identify the data we need to assess future trajectories.

Scenarios can also shine spotlights on warning signals, allowing decision makers to anticipate unexpected regime shifts and to act in a timely and effective way. They can support decision making in uncertain conditions by providing us a systematic way to assess the robustness of alternative strategies under a set of plausible future conditions. Although we do not know the probable impacts of uncertain futures, scenarios will provide us the basis to assess critical sensitivities, and identify both potential thresholds and irreversible impacts so we can maximize the wellbeing of both humans and our environment.

A new ethic for a hybrid planet

More than half a century ago, Aldo Leopold (1949) introduced the concept of “thinking like a mountain”: he wanted to expand the spatial and temporal scale of land conservation by incorporating the dynamics of the mountain. Defining a Land Ethic was a first step in acknowledging that we are all part of larger community hat include soils, waters, plants, and animals, and all the components and processes that govern the land, including the prey and predators. Now, along the same lines, Paul Hirsch and Bryan Norton (2012) In Ethical Adaptation to Climate Change: Human Virtues of the Future, MIT Press, articulates a new environmental ethics by suggesting that we “think like a planet.” Building on Hirsch and Norton’s idea, we need to expand the dimensional space of our mental models of urban design and planning to the planetary scale.

Marina Alberti

Seattle

Note: The metaphor of “thinking like a planet” builds on the idea of cognitive transformation proposed by Paul Hirsch and Bryan Norton (2012) In Ethical Adaptation to Climate Change: Human Virtues of the Future, MIT Press.

Related Links:

Wednesday, September 18. 2013

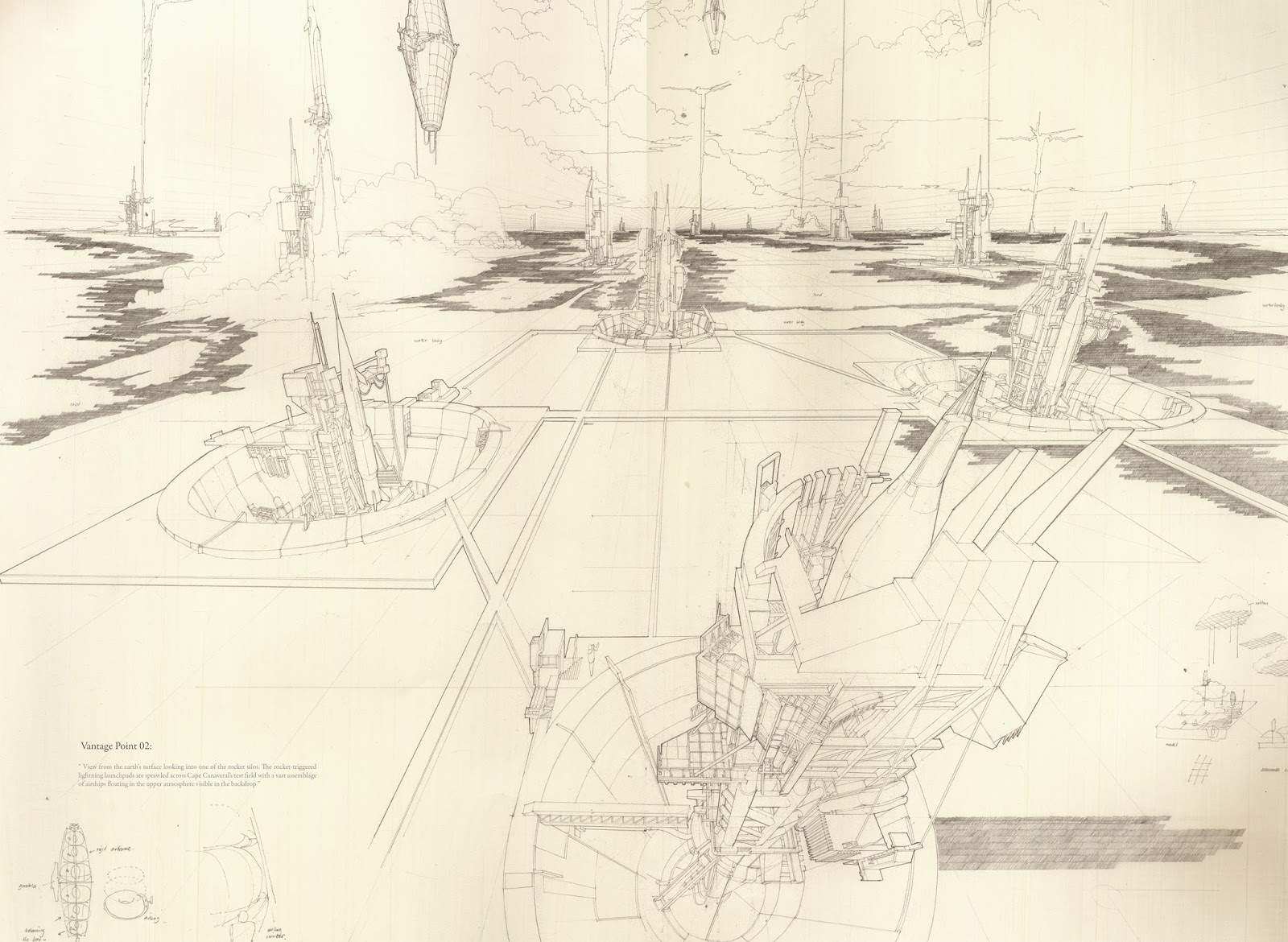

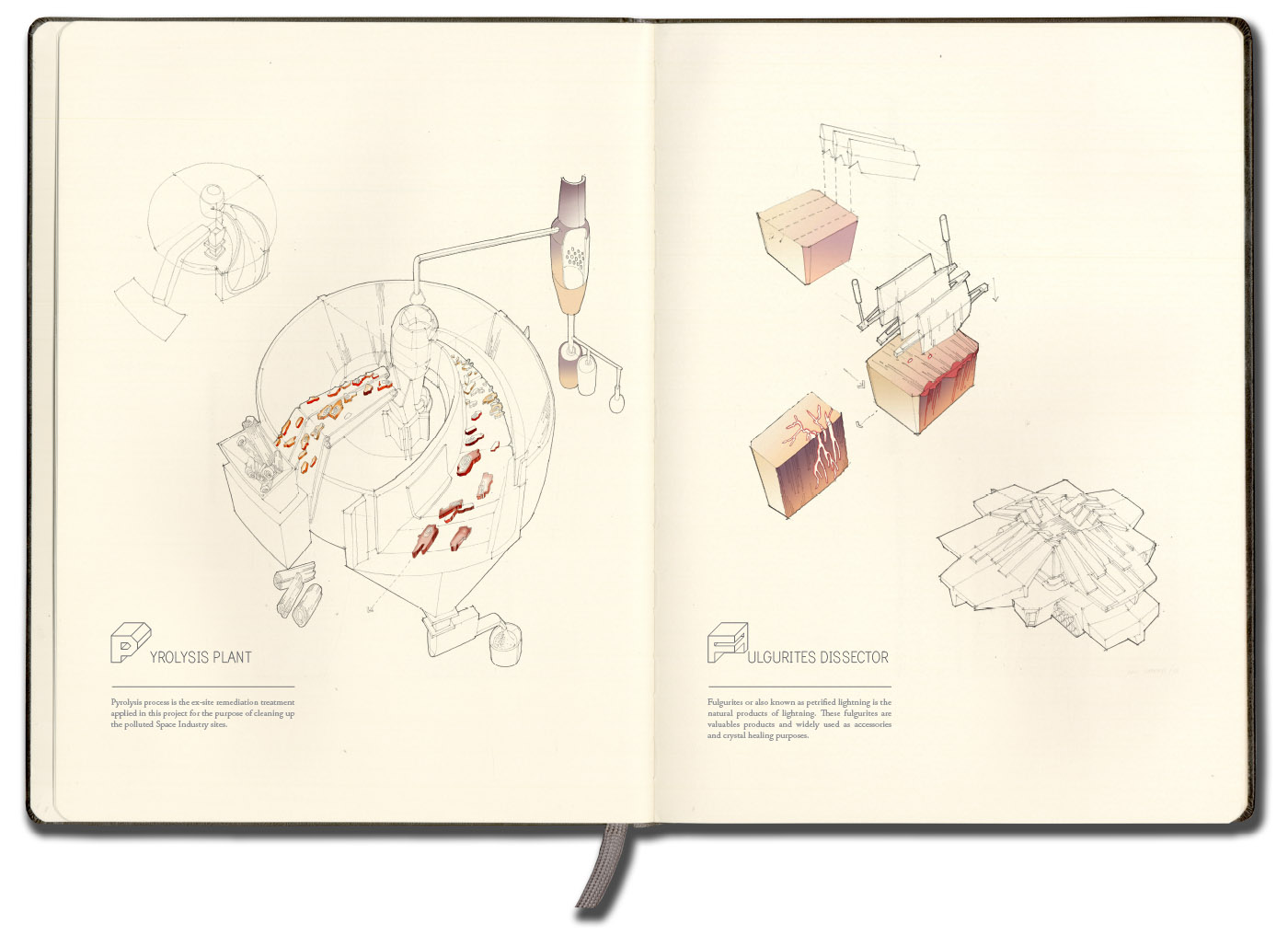

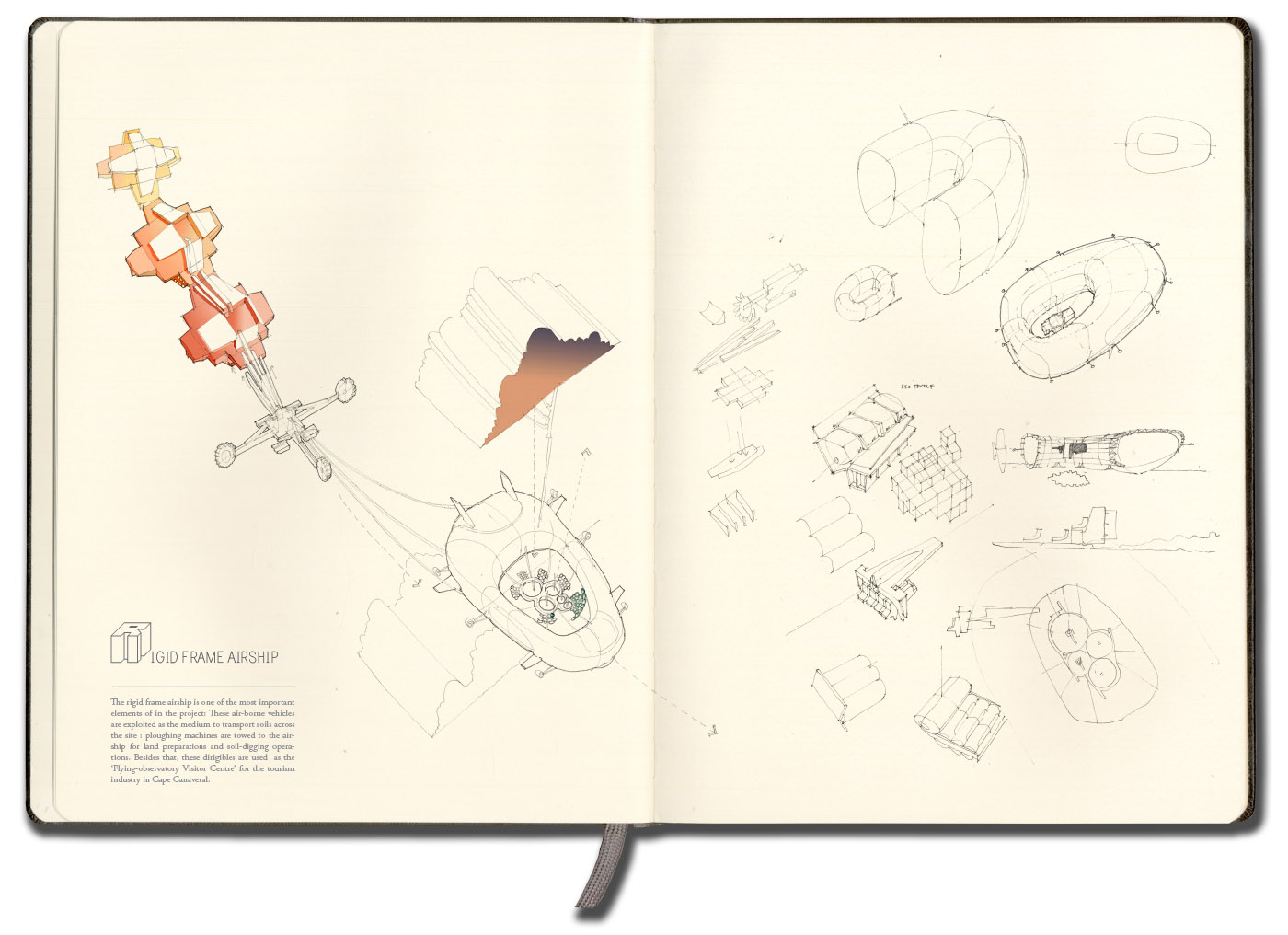

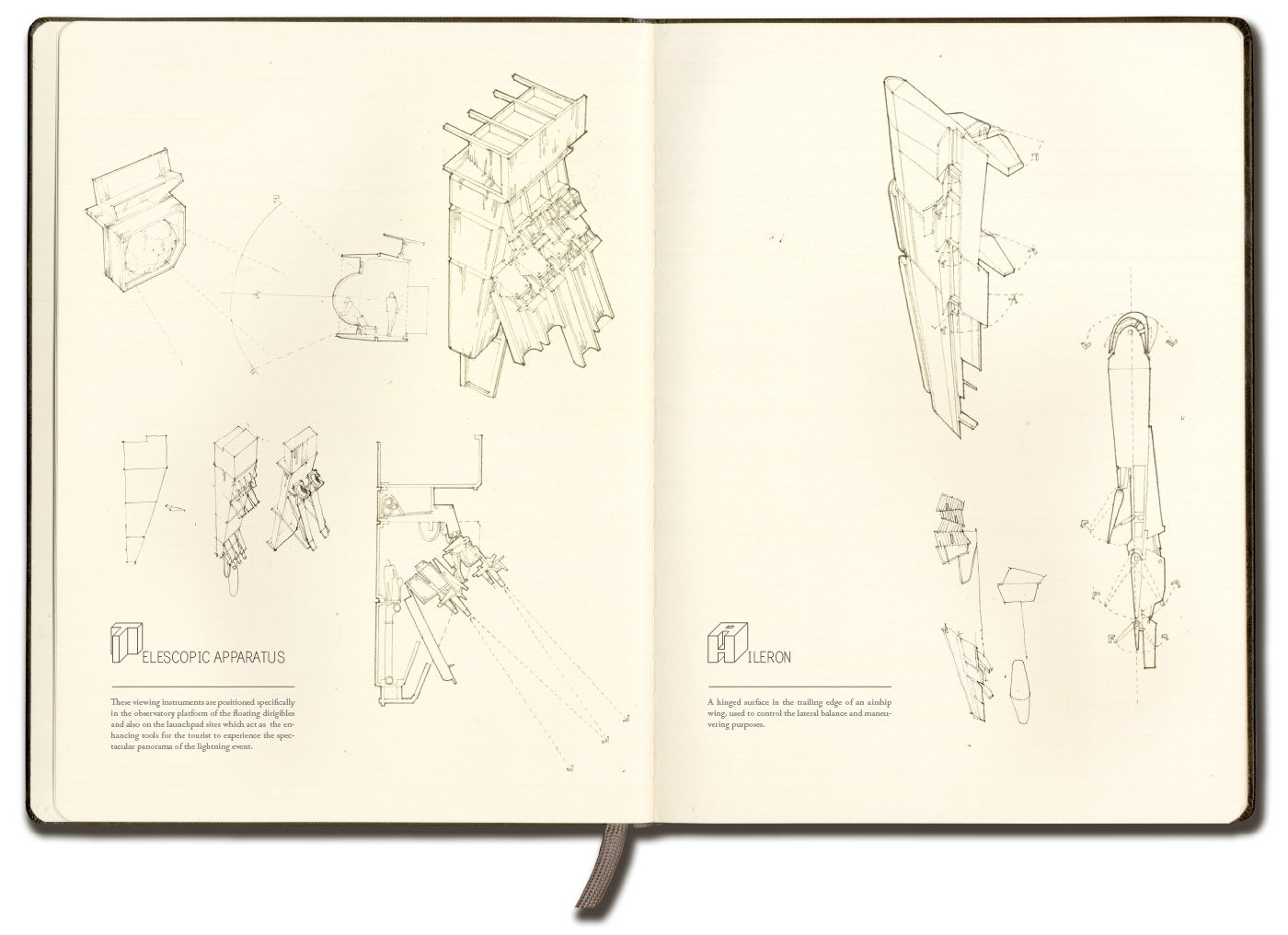

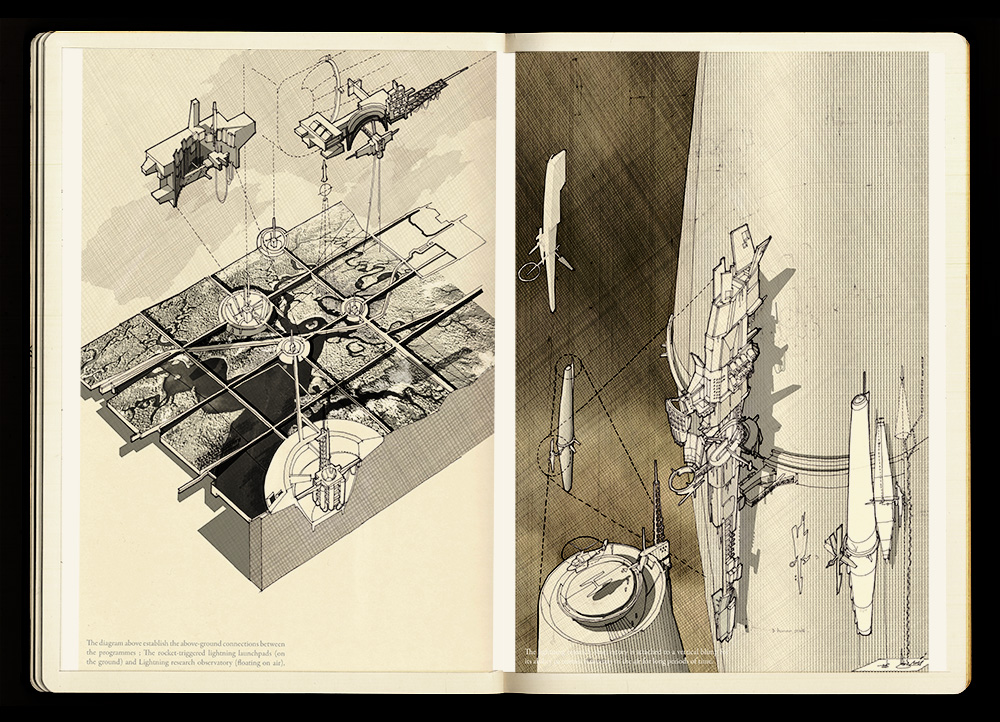

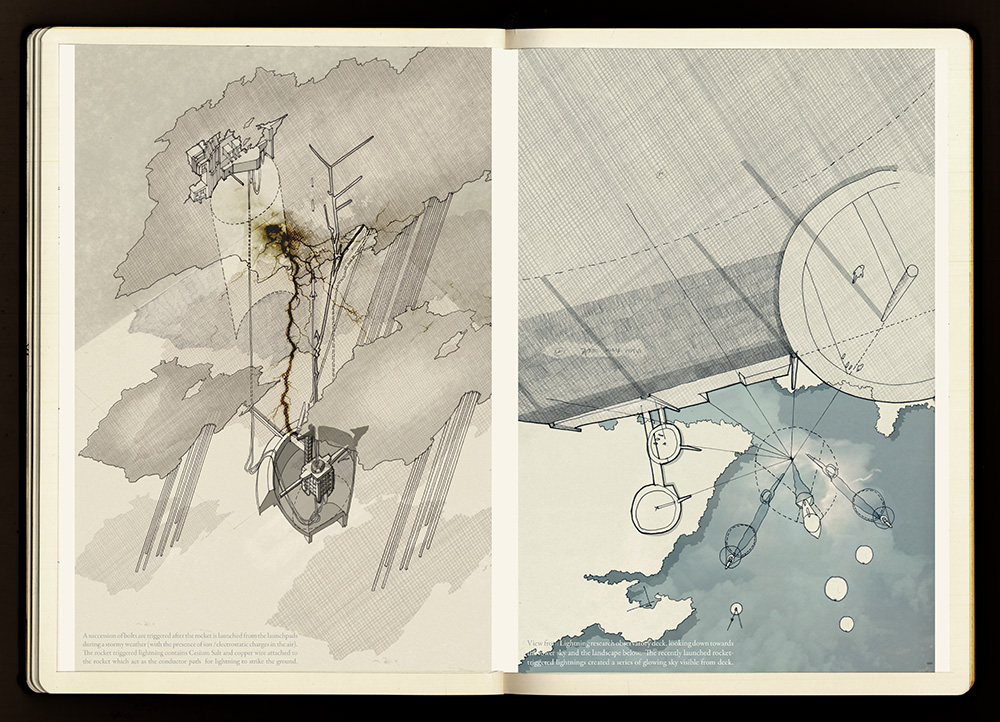

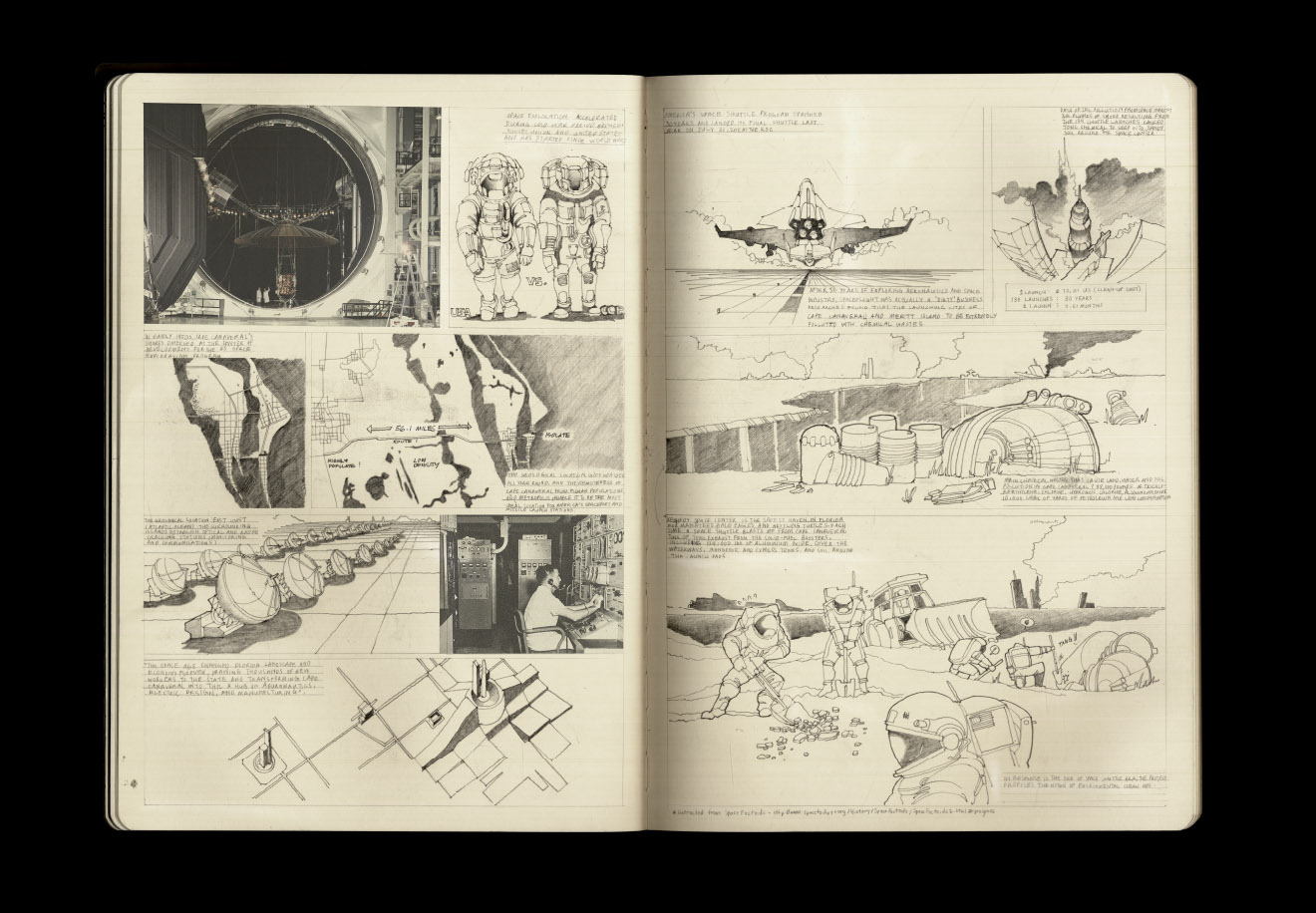

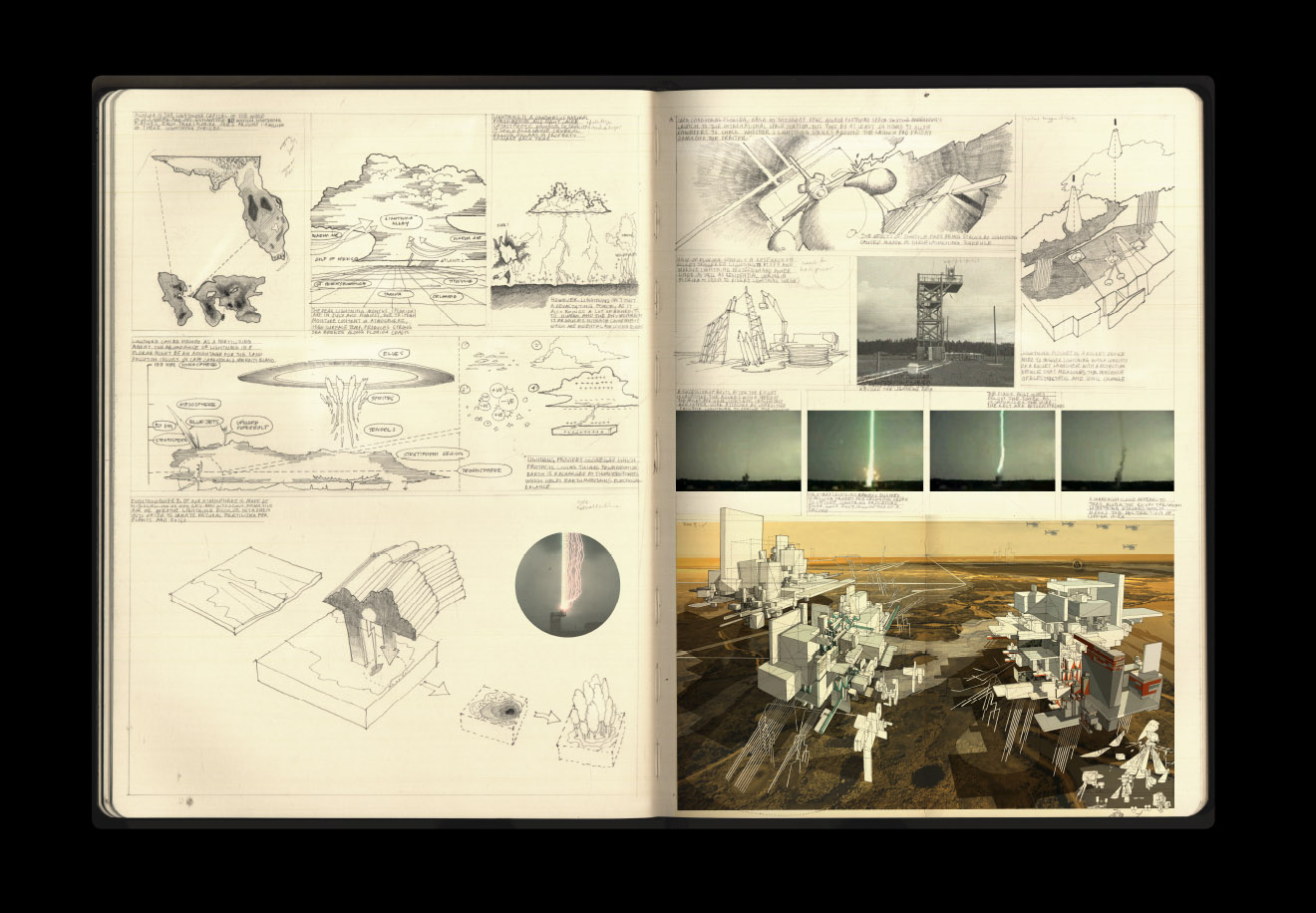

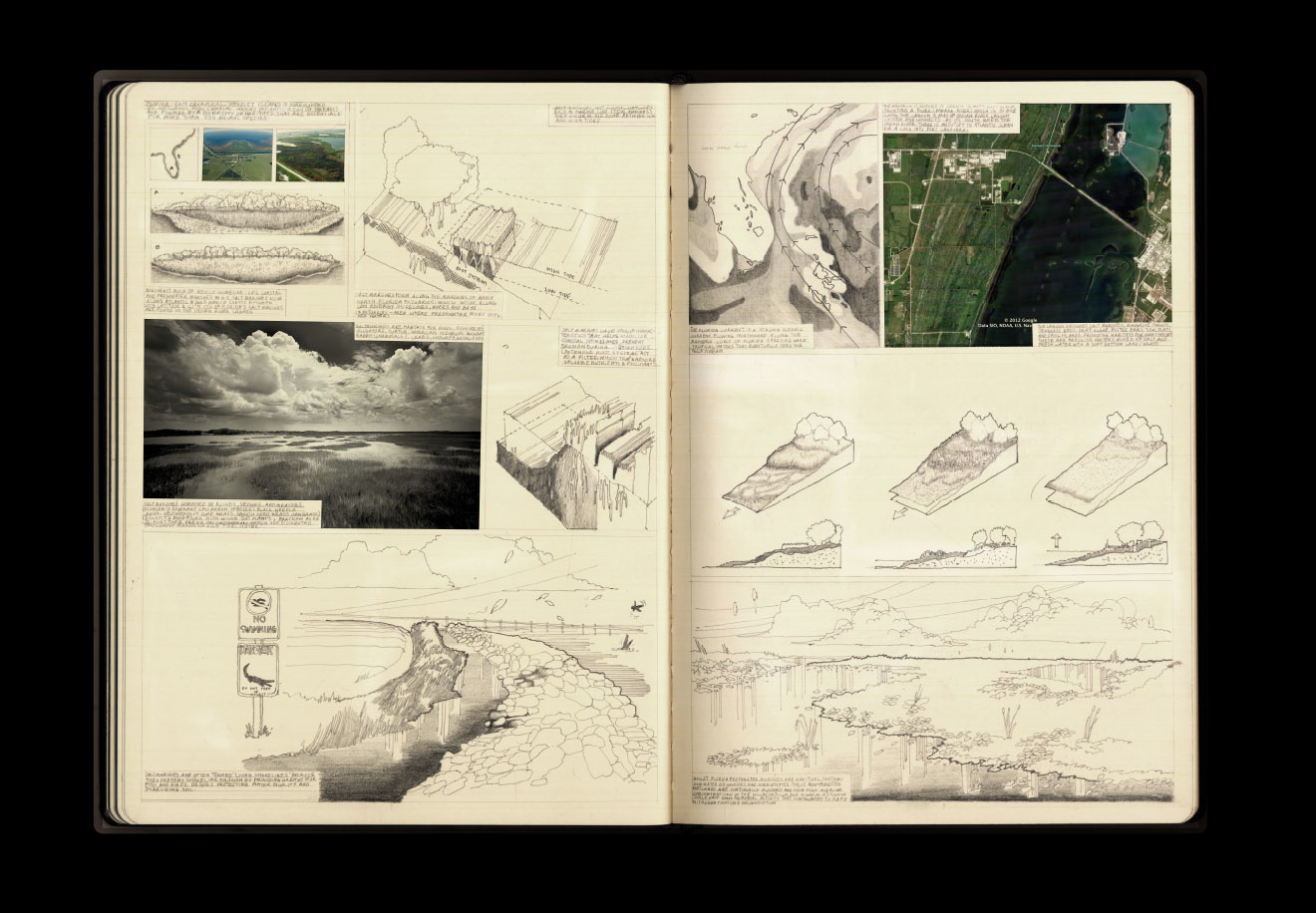

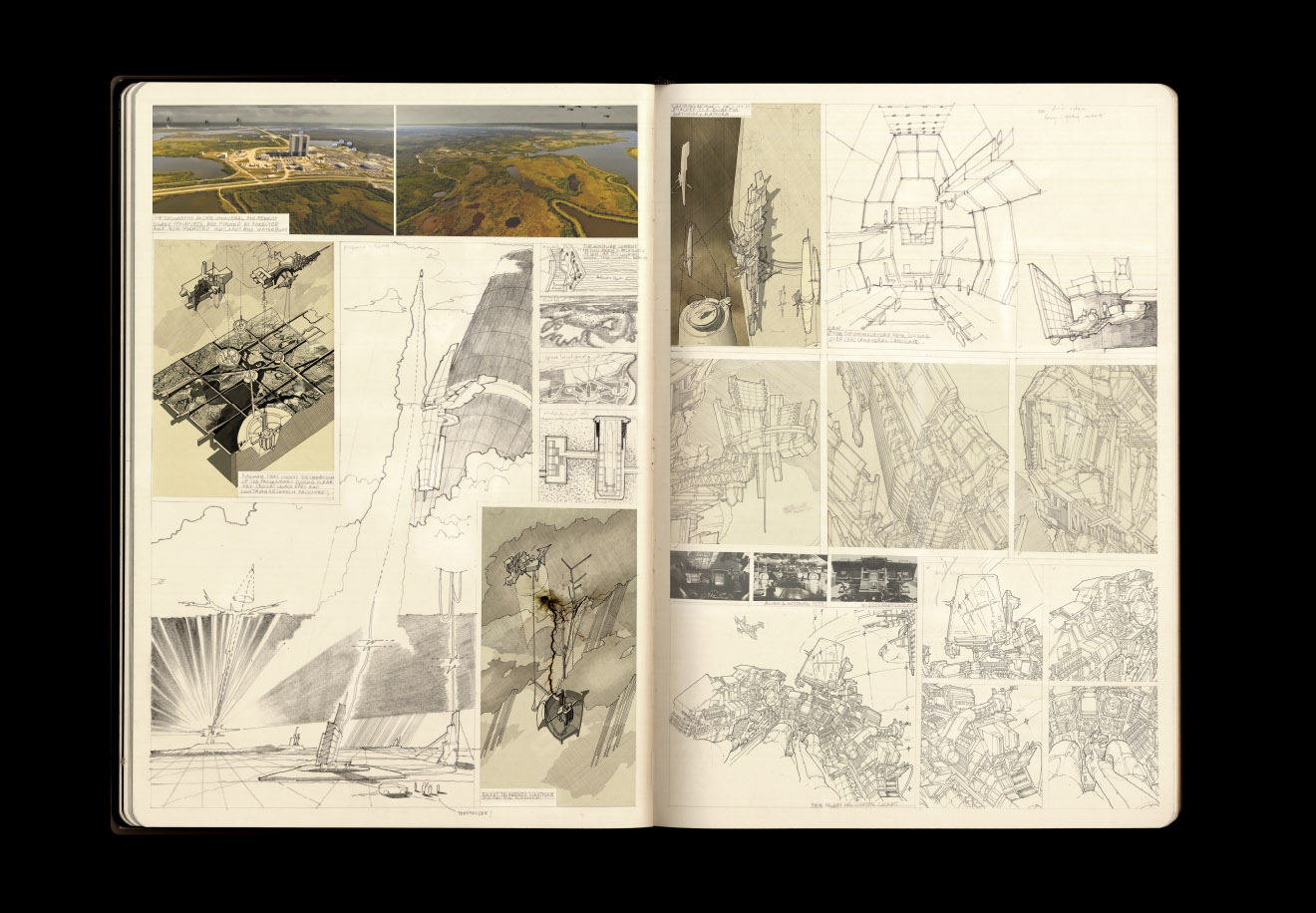

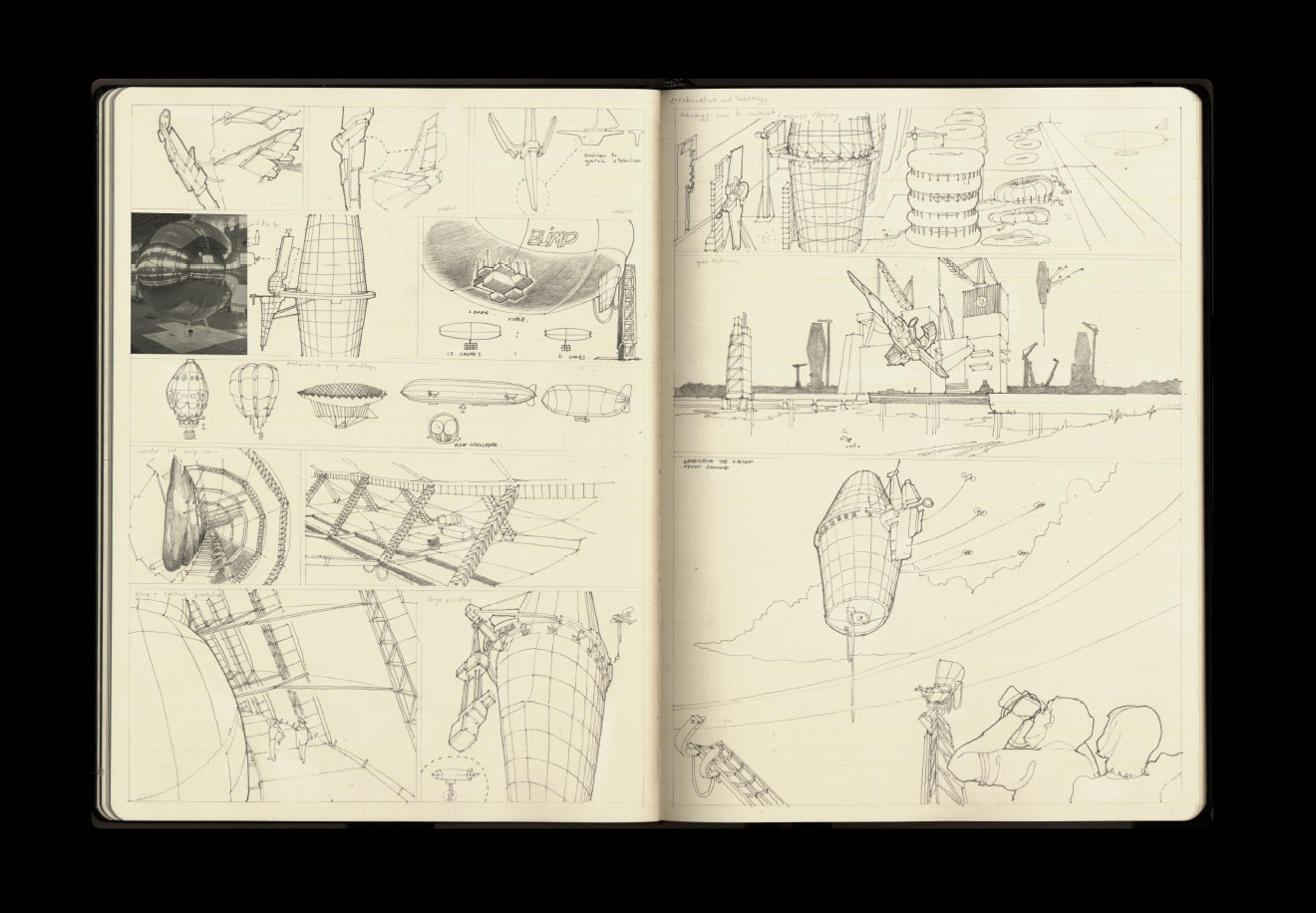

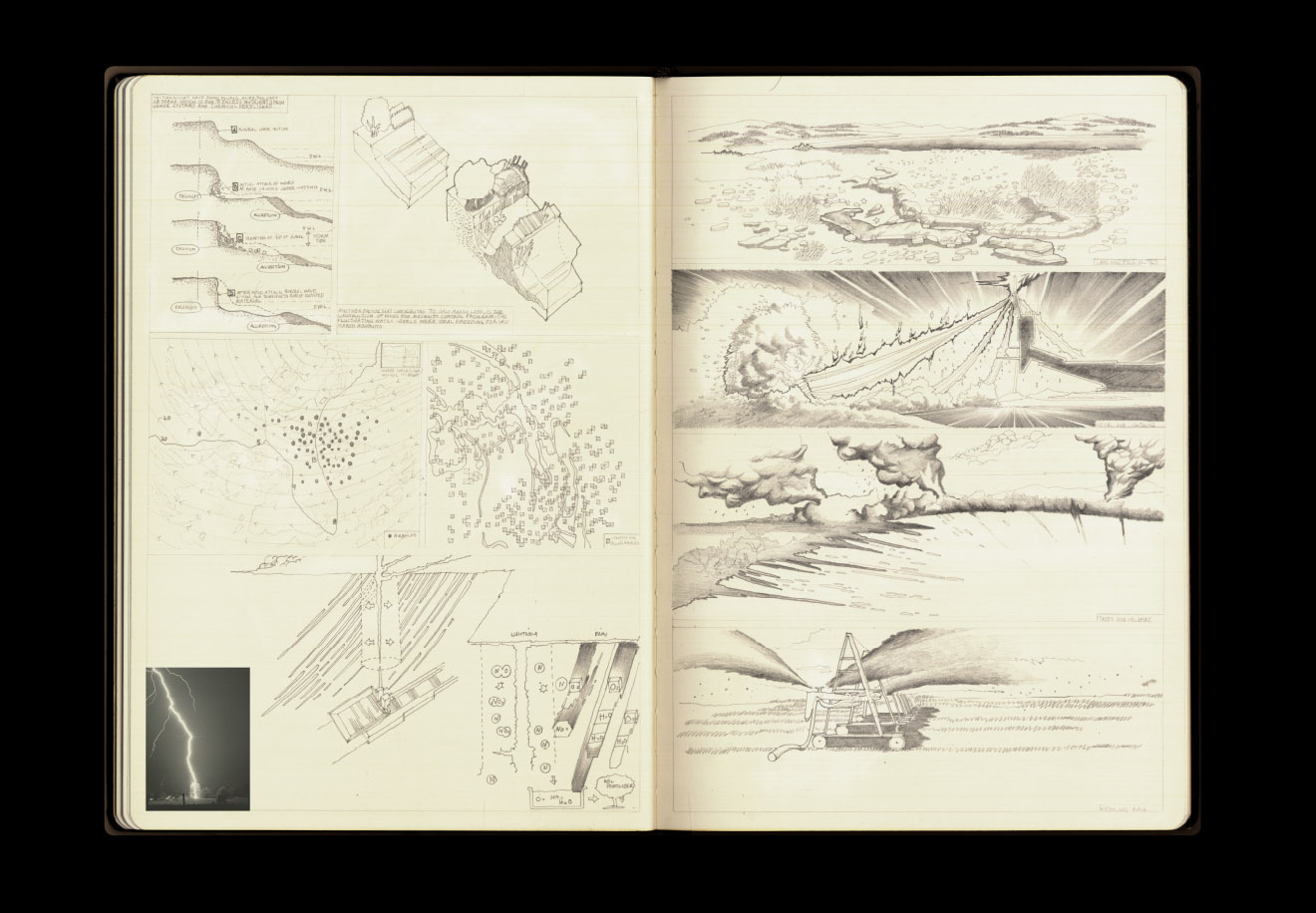

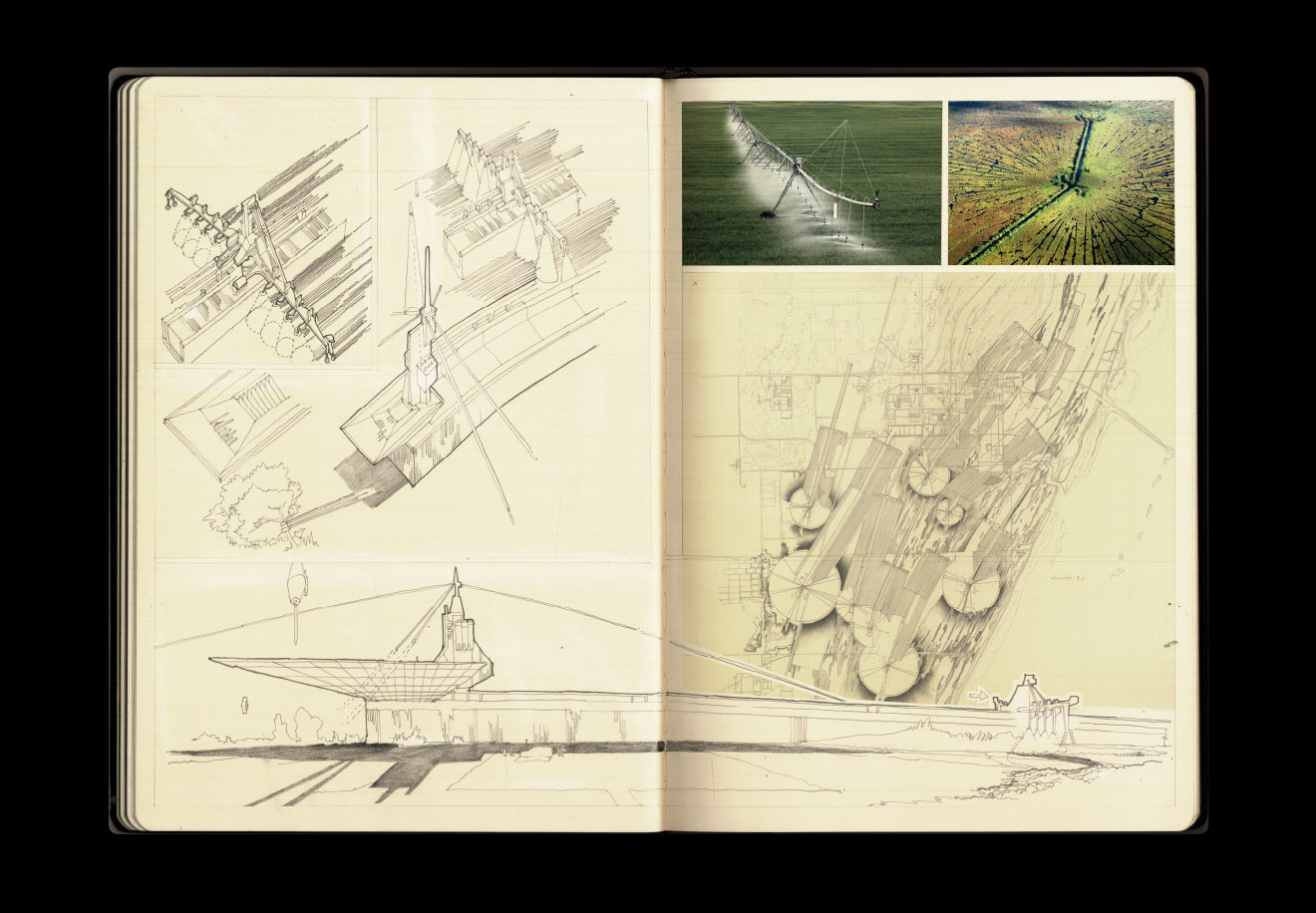

Lightning Farm

Via BLDGBLOG

-----

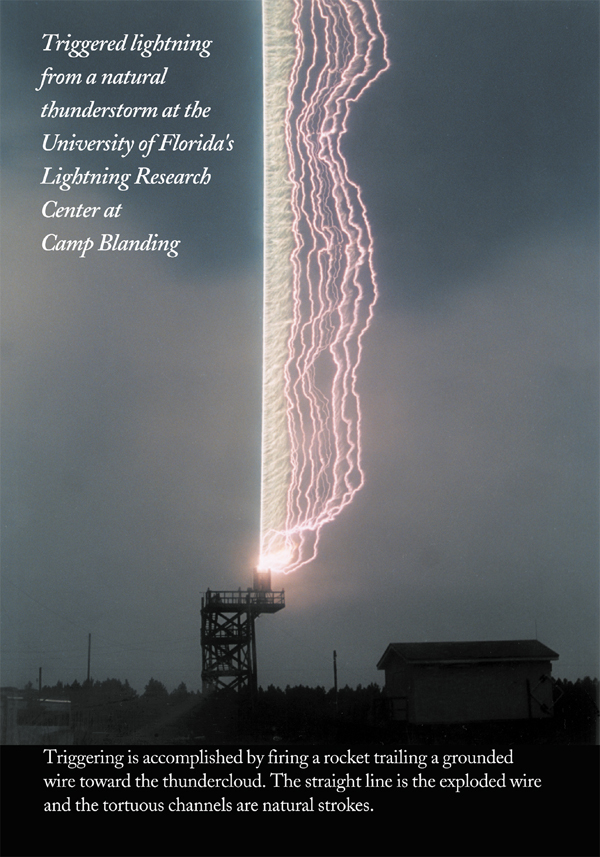

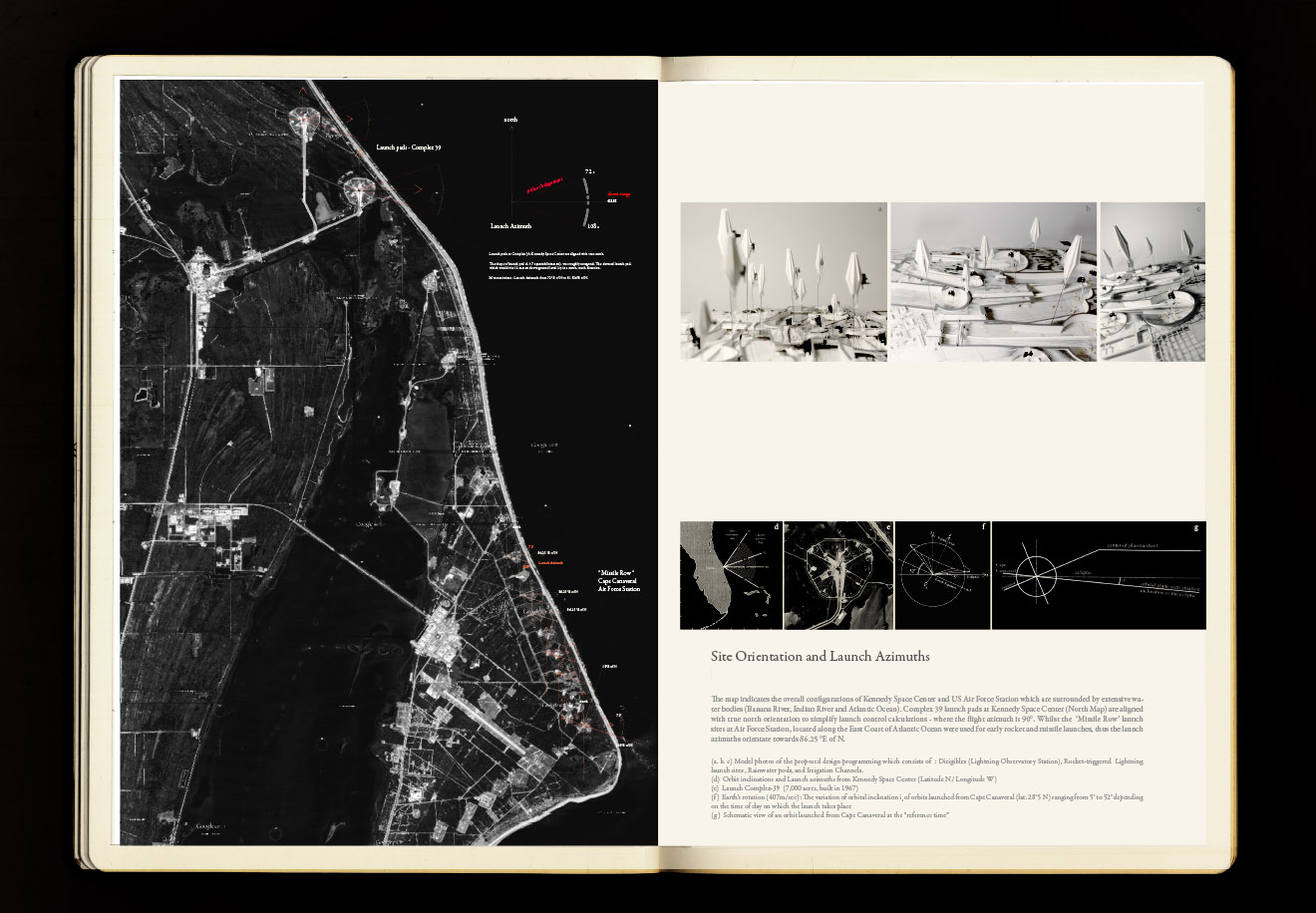

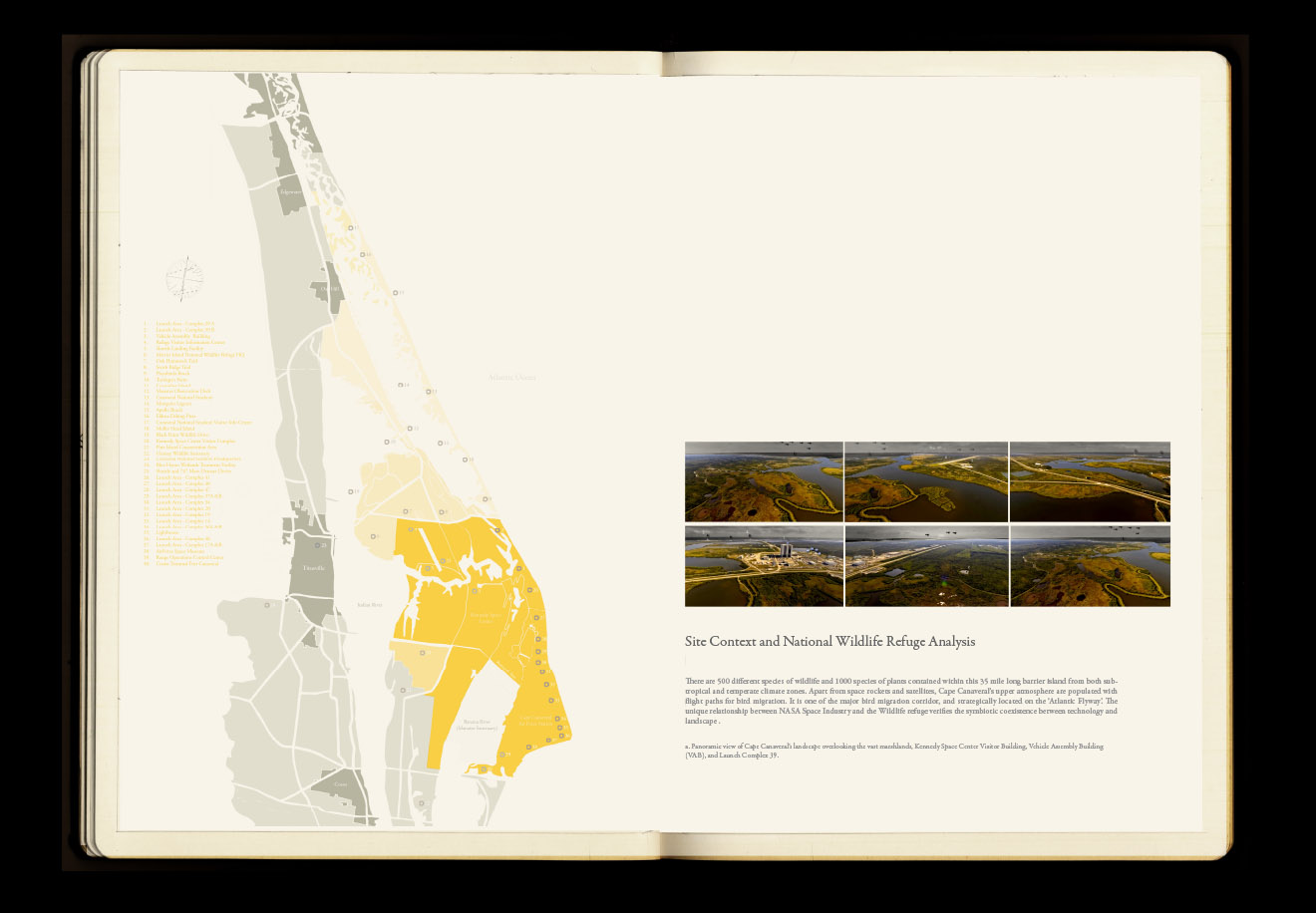

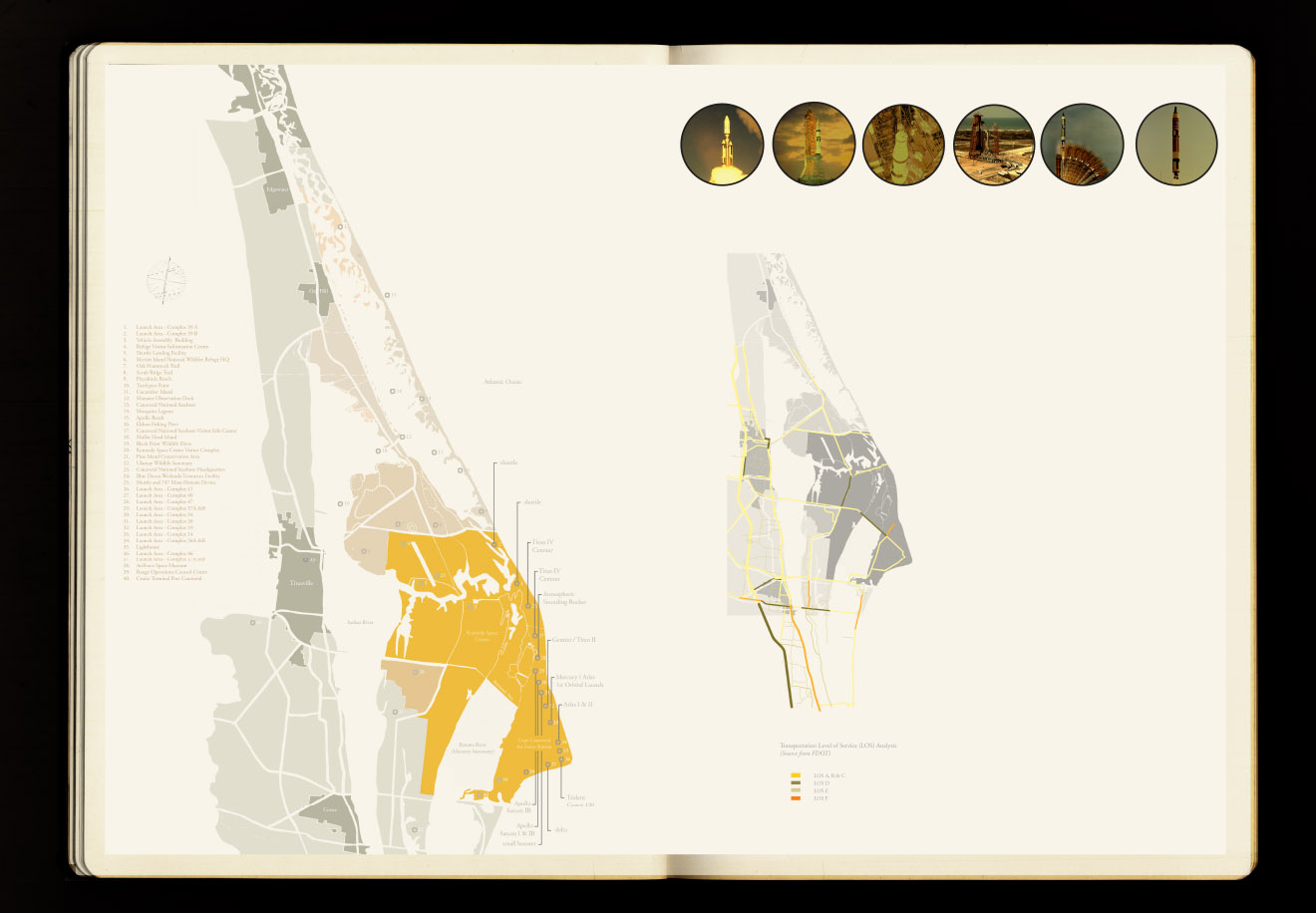

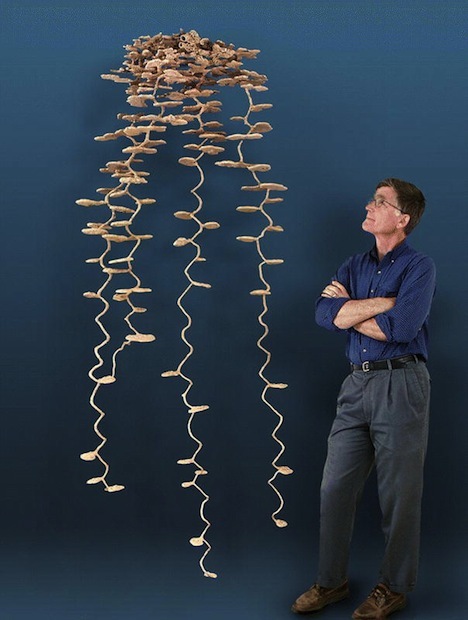

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida's Lightning Research Group].

This past winter, I had the pleasure of traveling around south Florida with Smout Allen, Kyle Buchanan, and nearly two dozen students from Unit 11 at the Bartlett School of Architecture.

Florida's variable terrains—of sink holes, swamps, and eroding beaches—and its Herculean infrastructure, from canals and freeways to theme parks and rocket facilities, served as the narrative backdrop for the many architectural projects ultimately produced by the class (in addition, of course, to the 2012 U.S. Presidential election, the results of which we watched live from the bar of a tropical-themed hotel near Cape Canaveral, next door to Ron Jon).

While there were many, many interesting projects resulting from the trip, and from the Unit in general, there is one that I thought I'd post here, by student Farah Aliza Badaruddin, particularly for the quality of its drawings.

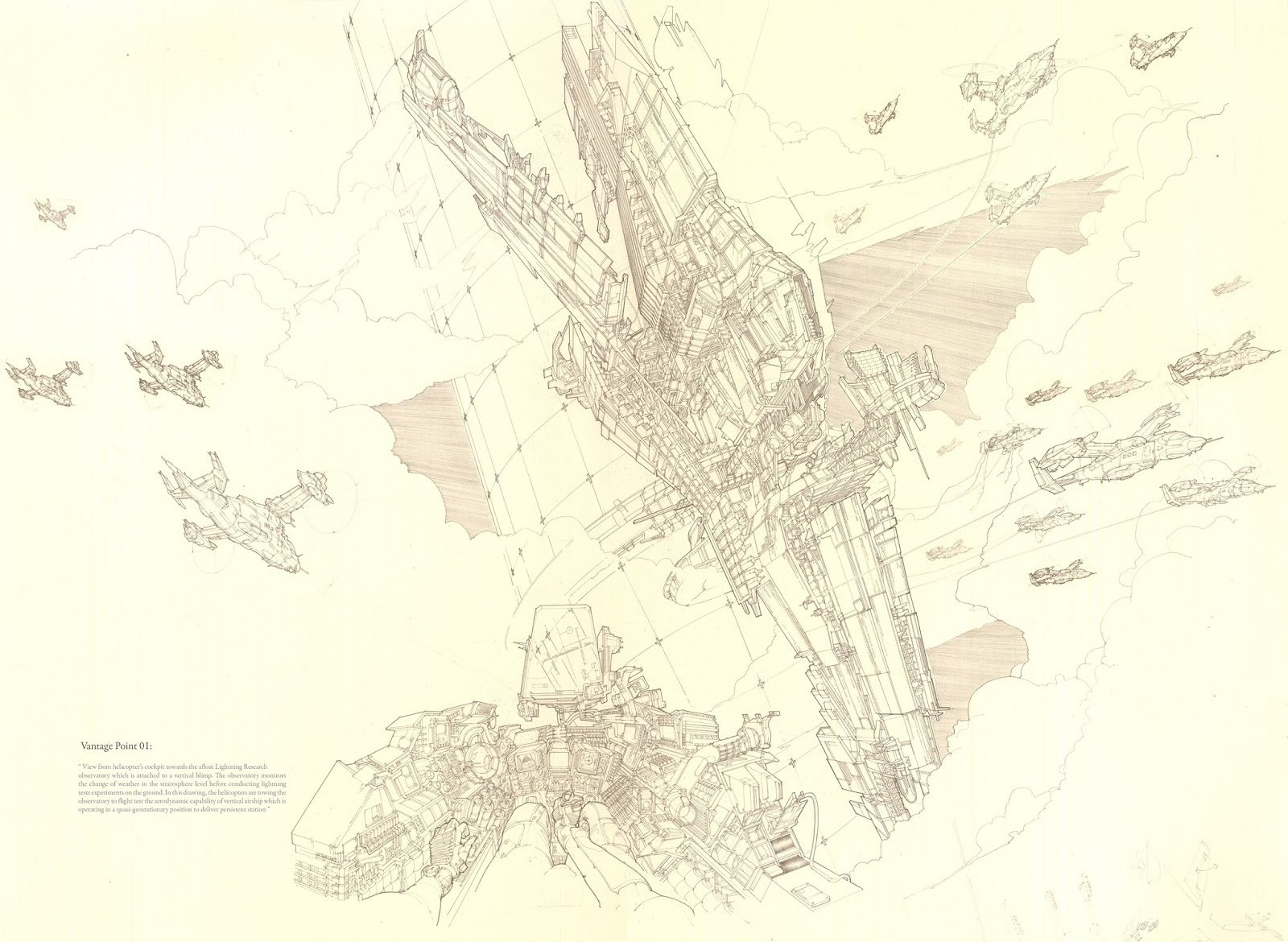

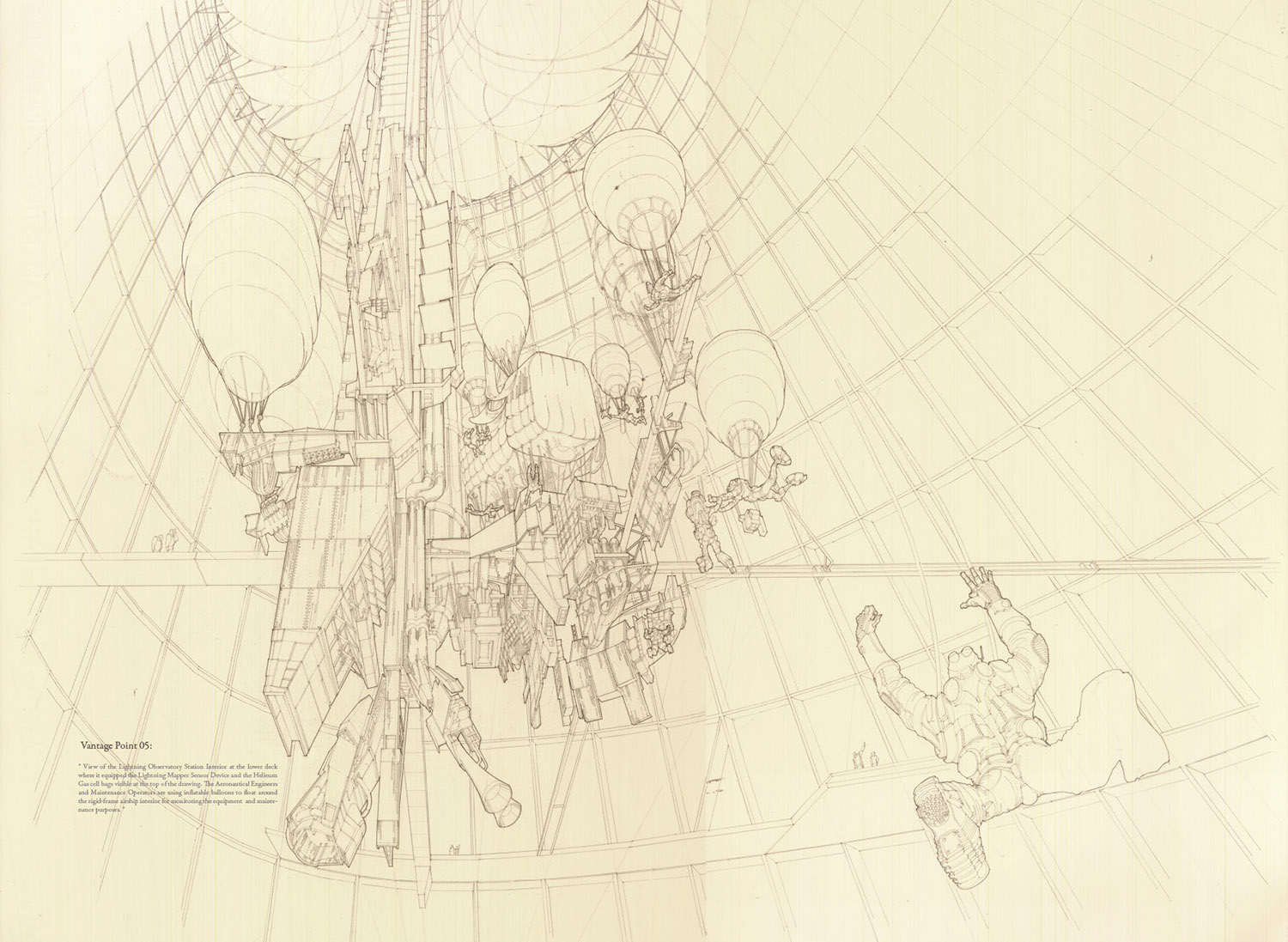

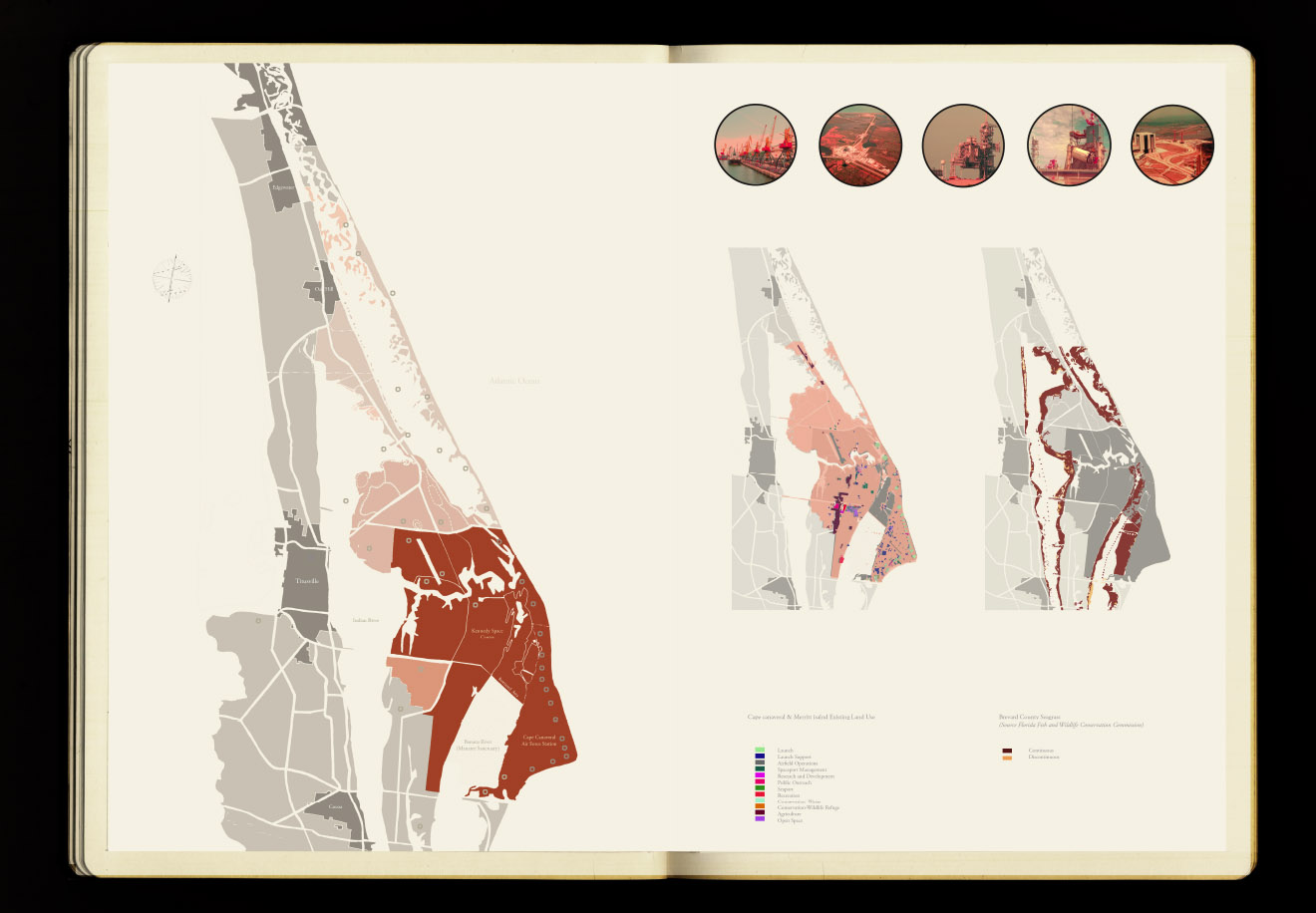

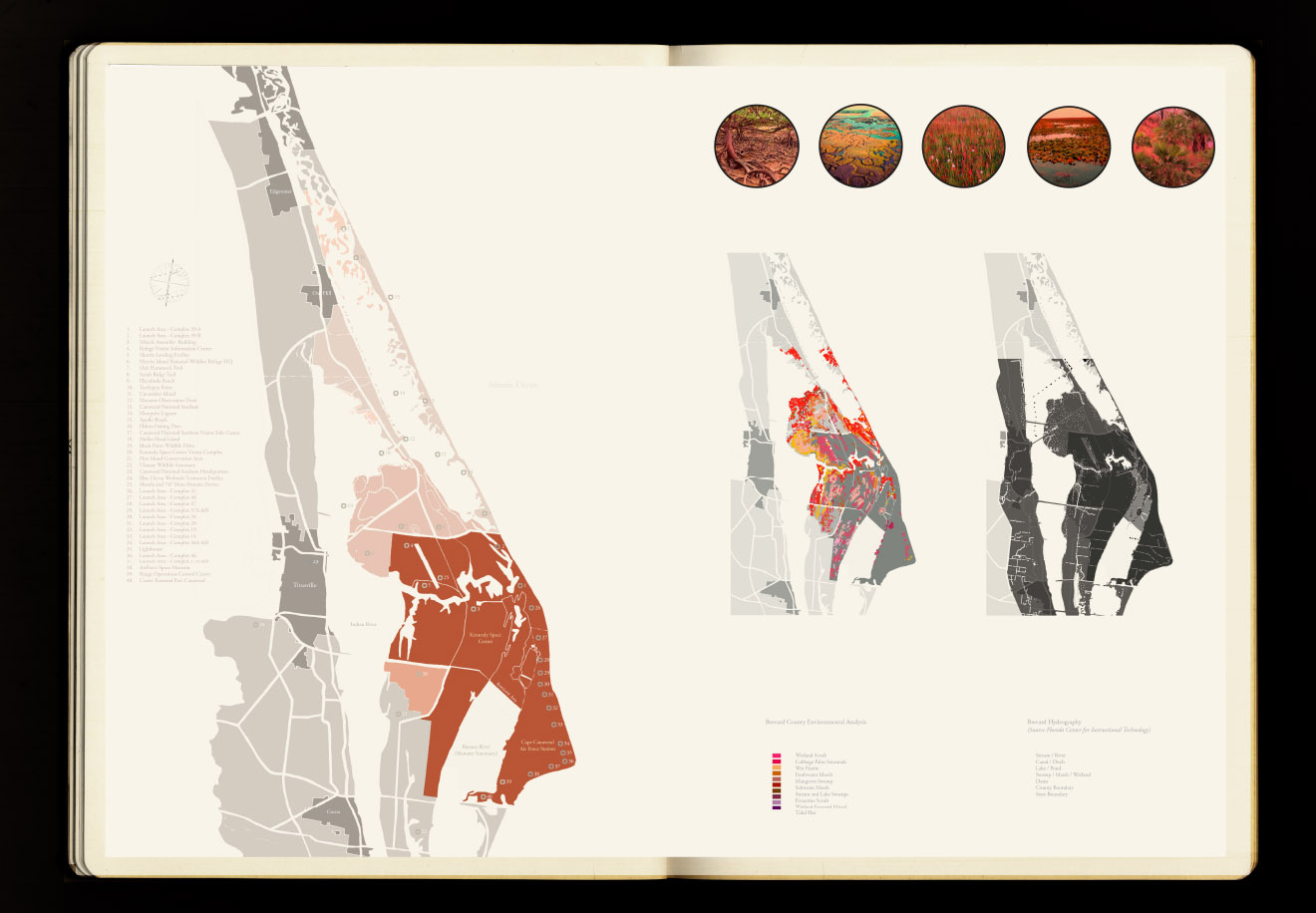

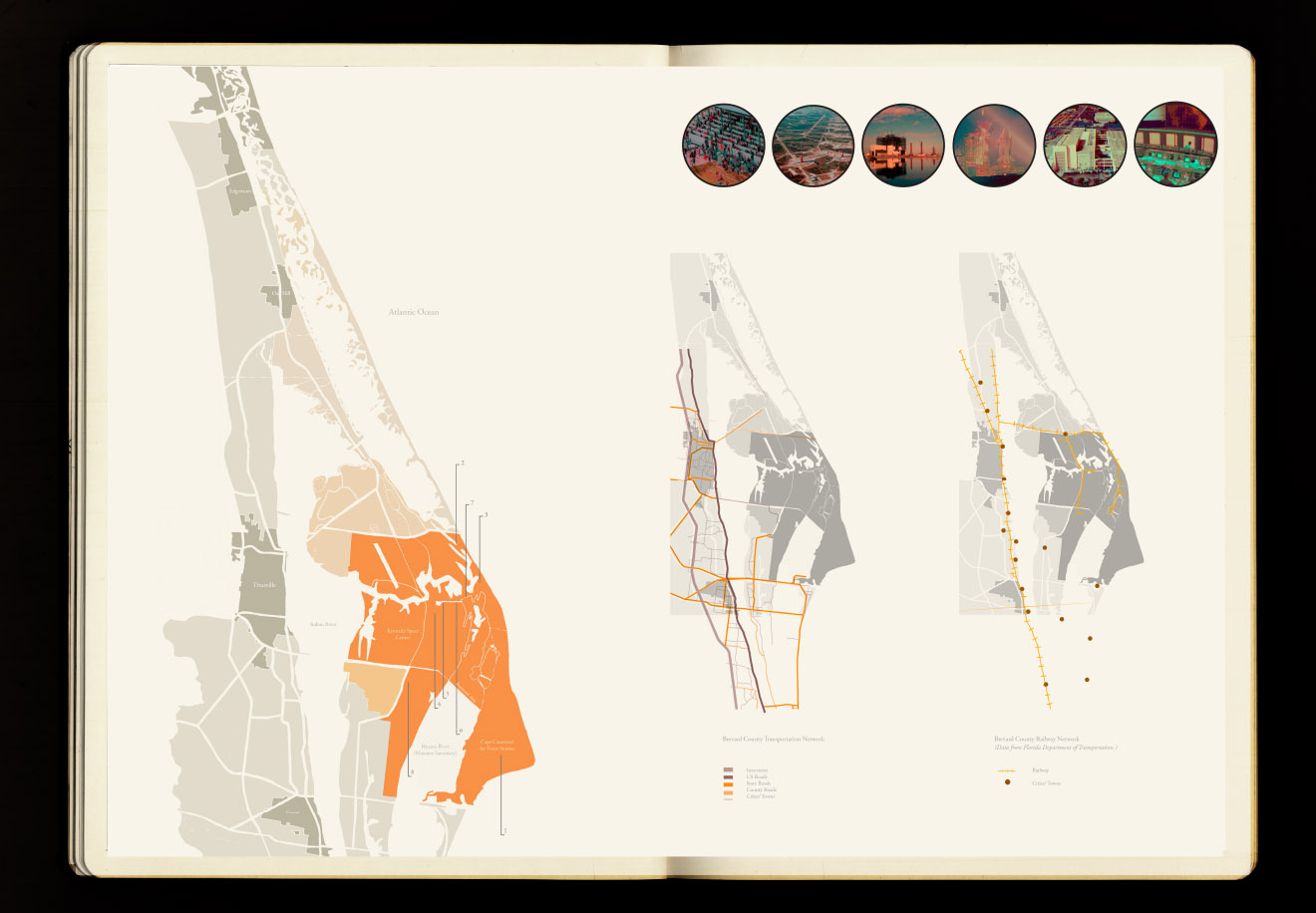

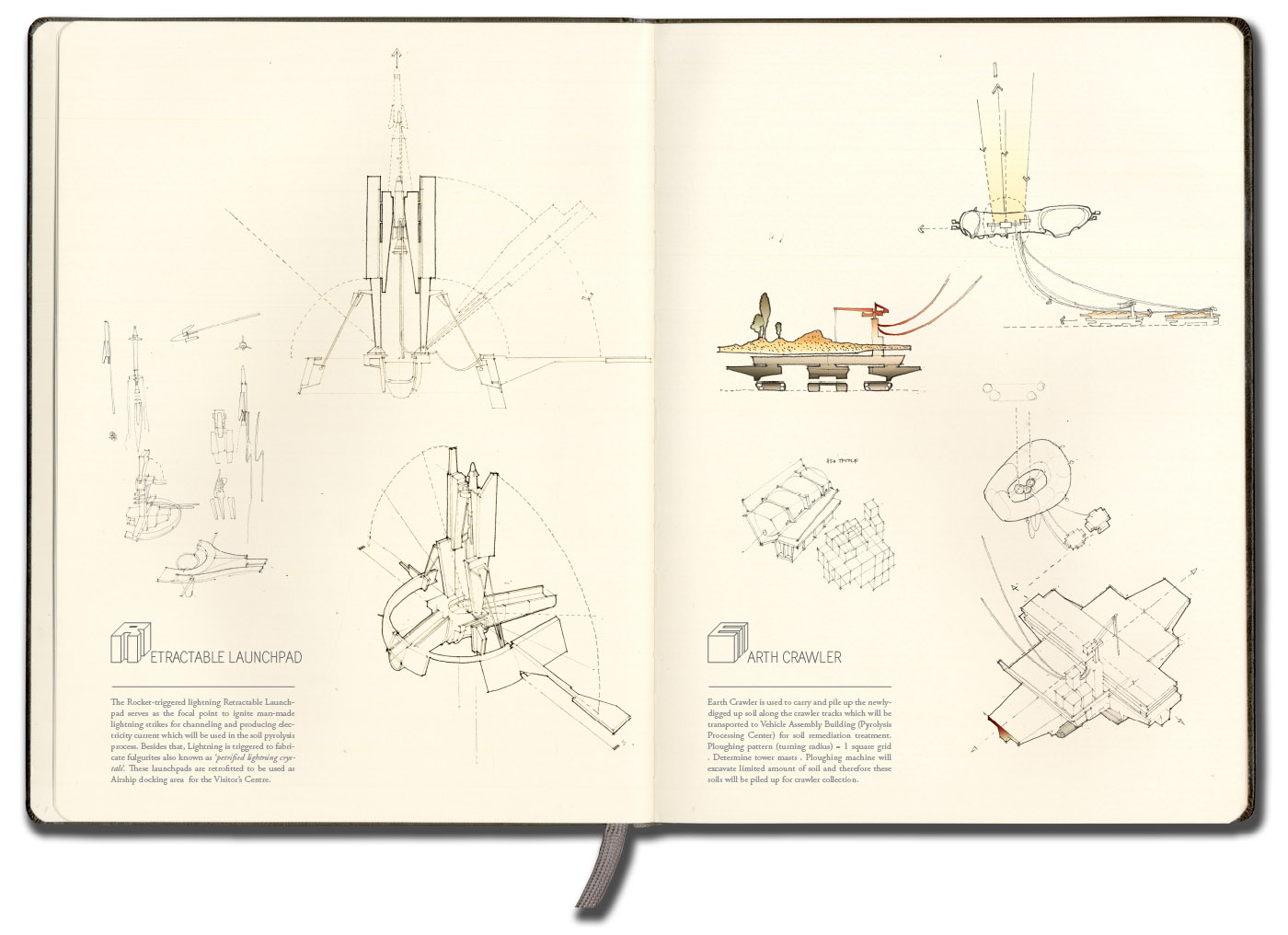

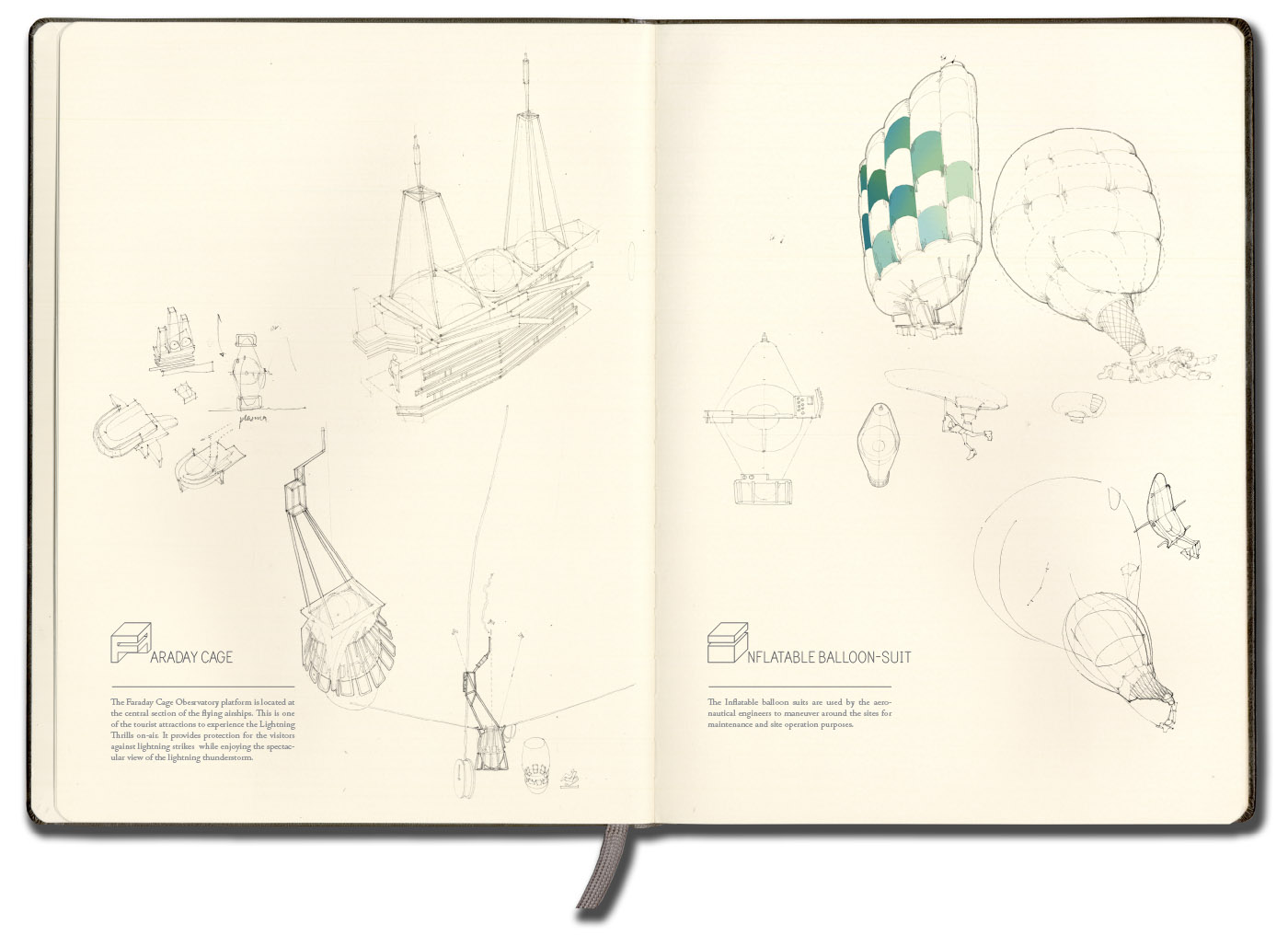

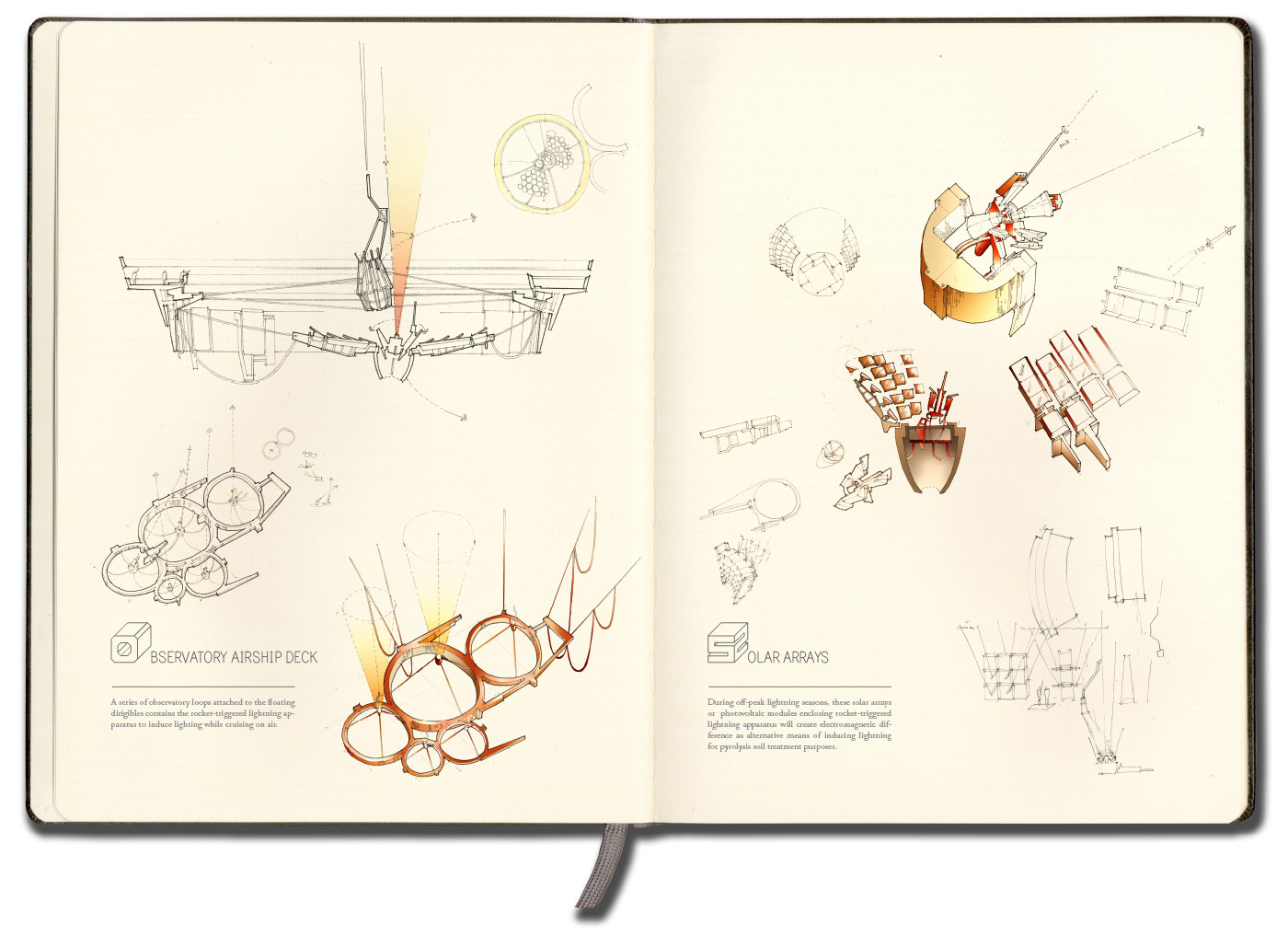

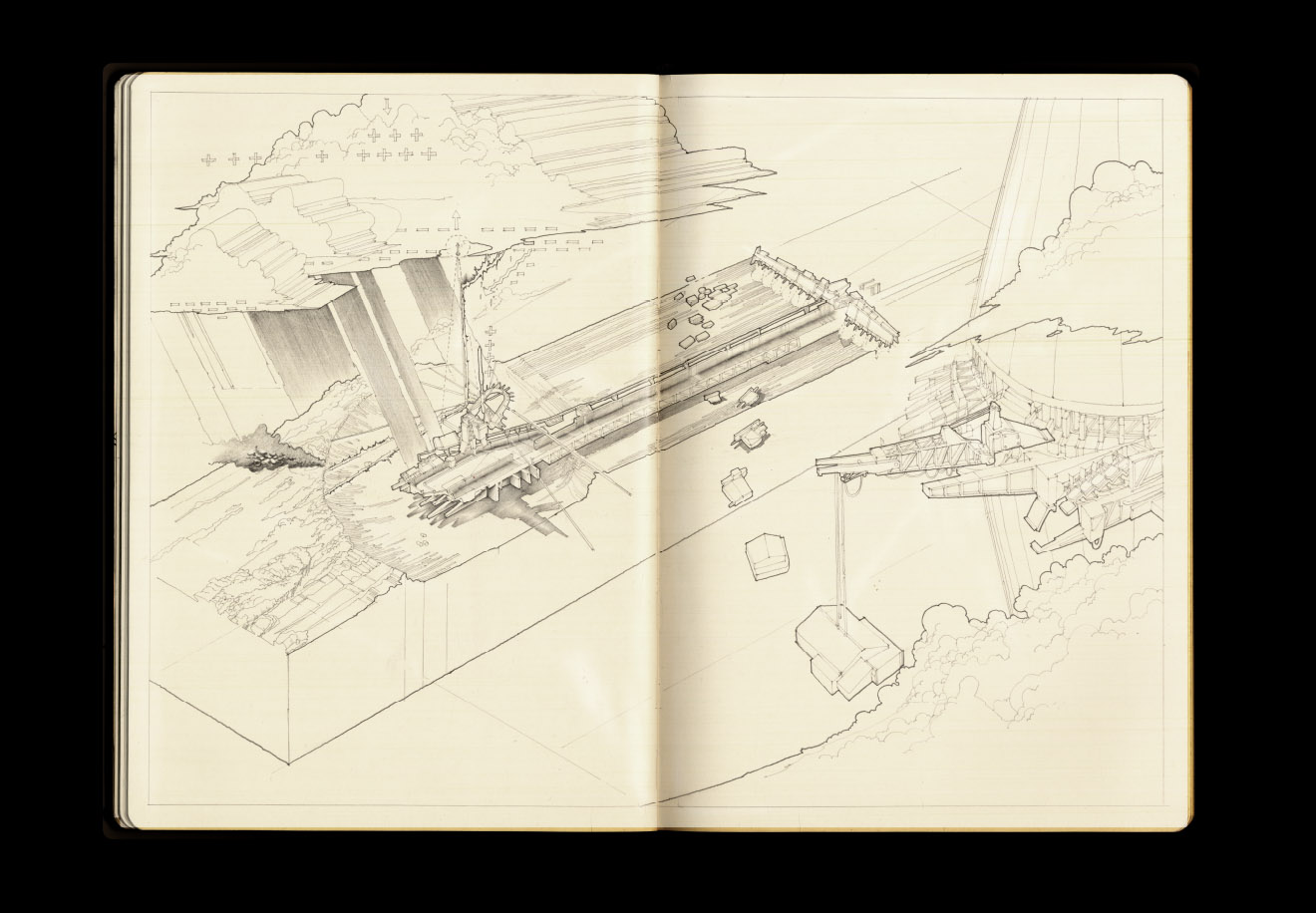

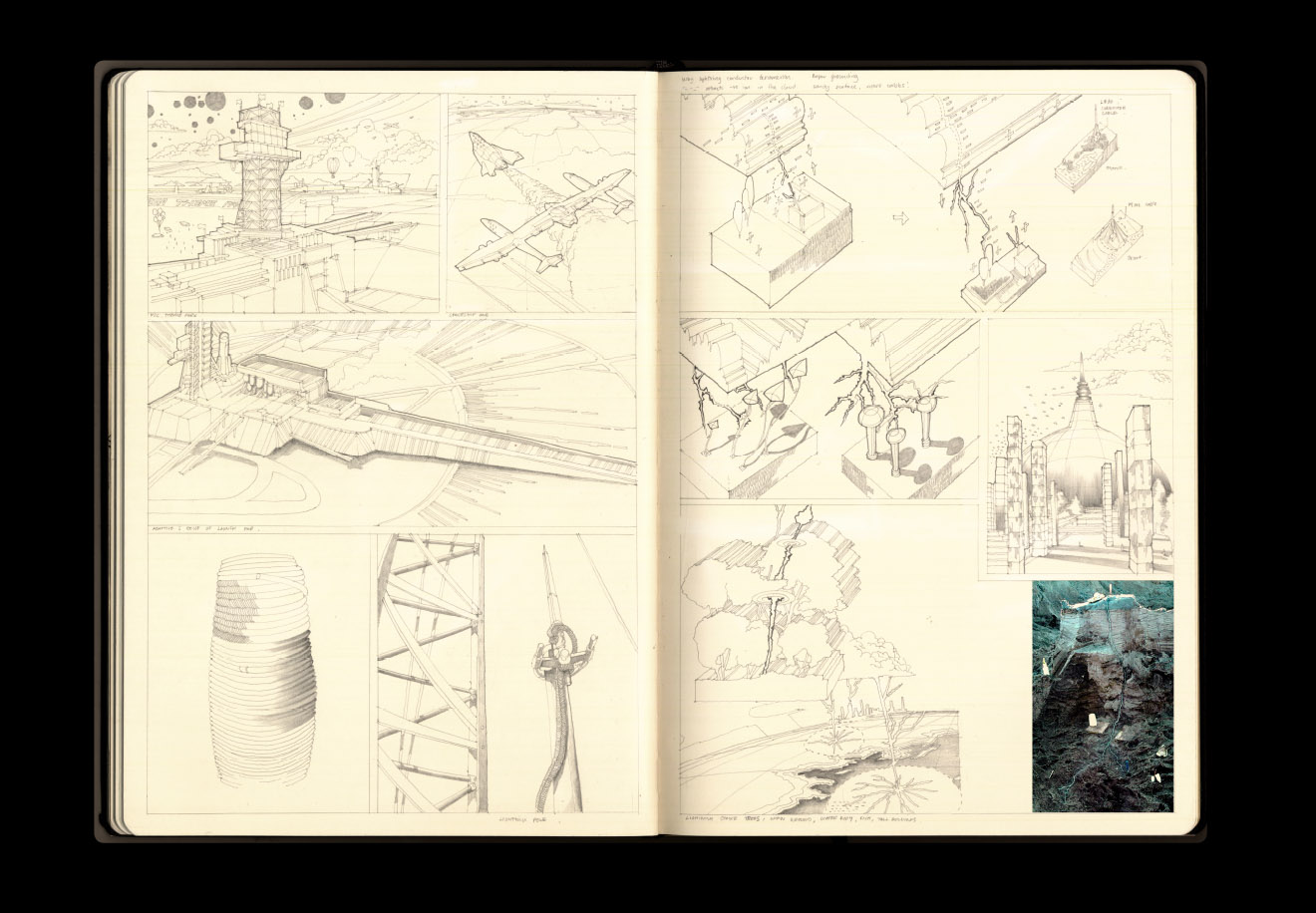

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

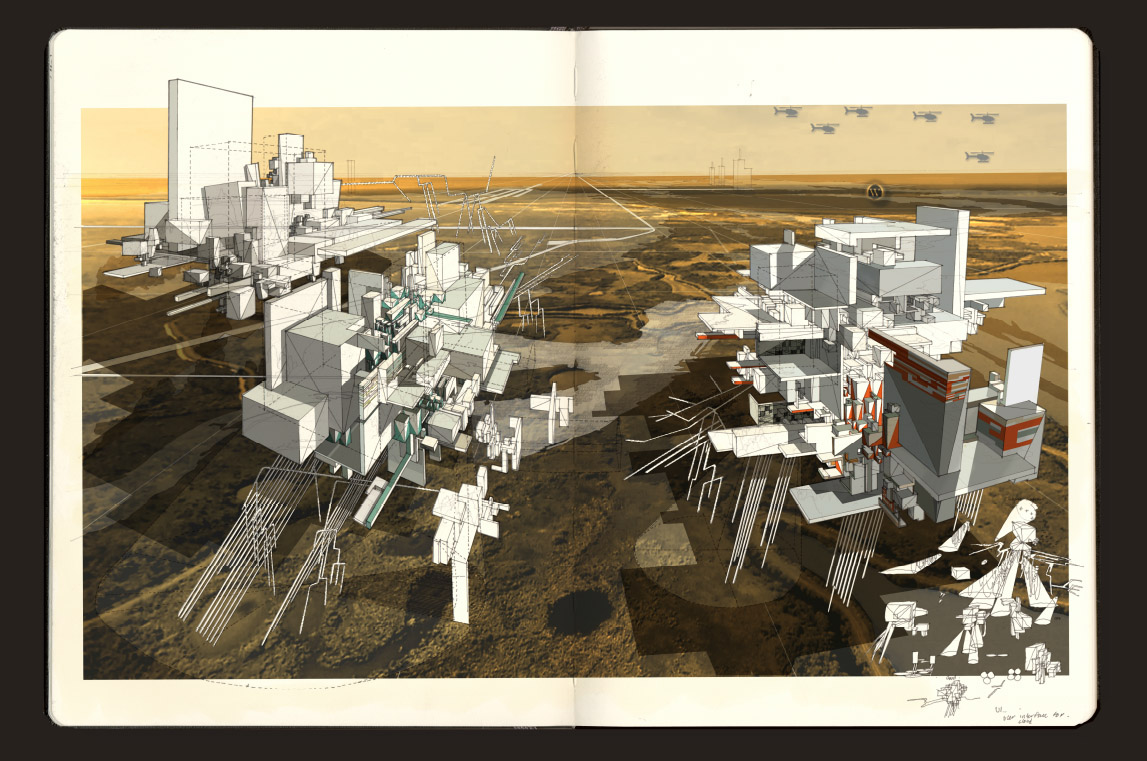

Badaruddin's project explored the large-scale architectural implications of applying radical weather technologies to the task of landscape remediation, asking specifically if Cape Canaveral's highly contaminated ground water—polluted by a "viscous toxic goo" made from tens of thousands of pounds of rocket fuels, chemical plumes, solvents, and other industrial waste products over the decades—could be decontaminated through pyrolysis, using guided and controlled bursts of lightning.

In her own words, Badaruddin explains that the would test "the idea that lightning can be harnessed on-site to pyrolyse highly contaminated groundwater as an approach to remediate the polluted site."

These controlled and repetitive lightning strikes would also, in turn, help fertilize the soil, producing a kind of bio-electro-agricultural event of truly cosmic (or at least Miller-Ureyan) proportions.

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida Lightning Research Group].

Her maps of the area—which she presents as if drawn in a Moleskine notebook—show the terrestrial borders of the proposal (although volumetric maps of the sky, showing the project's fully three-dimensional engagement with regional weather systems, would have been an equally, if not more, effective way of showing the project's spatial boundaries).

This raises the awesome question of how you should most accurately represent an architectural project whose central goal is to wield electrical influence on the atmosphere around it.

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

In short, her design proposes a new infrastructure of "rocket-triggered lightning technology," assisted and supervised by a peripheral network of dirigibles—floating airships that "surround the site and serve as the observatory platform for a proposed lightning visitor centre and the weather research center."

The former was directly inspired by real-world lightning research equipment found at the University of Florida's Lightning Research Group.

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida's Lightning Research Group].

Badaruddin's own rocket triggers would be used both to attract and "to provide direct lightning strikes to the proposed sites," thus pyrolizing the landscape and purifying both ground water and soil.

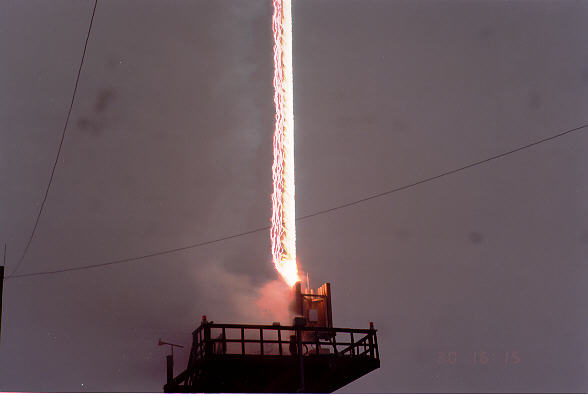

[Image: Aerial collage view of the lightning farm, by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

The result would be a lightning farm, a titanic landscape tuned to the sky, flashing with controlled lightning strikes as the ground conditions are gradually remediated—an unmoving, nearly permanent, artificial electrical storm like something out of Norse mythology, cleansing the earth of toxic chemicals and preparing the site for future reuse.

[Image: Collage of the lightning farm, by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

I should say that my own interest in these kinds of proposals is less in their future workability and more in what it means to see a technology taken out of context, picked apart for its spatial implications, and then re-scaled and transformed into a speculative work of landscape architecture. The value, in other words, is in re-thinking existing technologies by placing them at unexpected scales in unexpected conditions, simultaneously extracting an architectural proposal from that and perhaps catalyzing innovative new ways for the original technology itself to be redeveloped or used.

[Image: Farah Aliza Badaruddin].

It's not a question of whether or not something can be immediately realized or built; it's a question of how open-ended, fictional design proposals can change the way someone thinks about an entire field or class of technologies.

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

But I'll let Badaruddin's own extraordinary visual skills tell the story. Most if not all of these images can be seen in a much larger size if you open the images in their own windows; they're well worth a closer look—

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

—including what amount to a short graphic novel telling the story of her proposed controlled-lightning landscape-decontamination facility.

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

All in all, whether or not architecturally-controlled lightning storms will ever purify the land and water of south Florida, it's a wonderfully realized and highly imaginative project, and I hope Badaruddin finds more opportunities, post-Bartlett, to showcase and develop her skills.

Wednesday, June 26. 2013

Ant architecture

Following my previous post mentioning the printing of insects based food, could we also start to ask ants to design our own buildings?

Via Archinect

-----

Personal comment:

Not a friendly way to map the ant's constructions, but quite fascinating resulting metallic structures nonetheless. Something in between a bioinspired design, an amorphous (alien) organisation and a structrured, repetitive architectural pattern.

Thursday, February 07. 2013

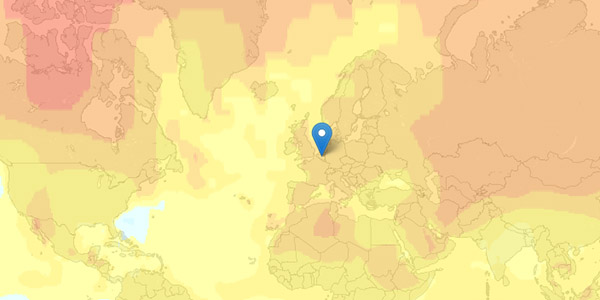

One degree (Celsius) of separation, huge differences

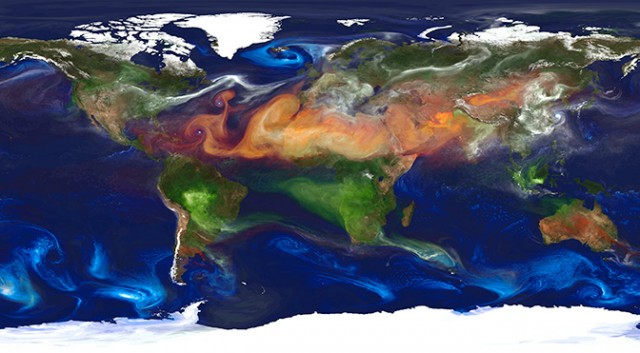

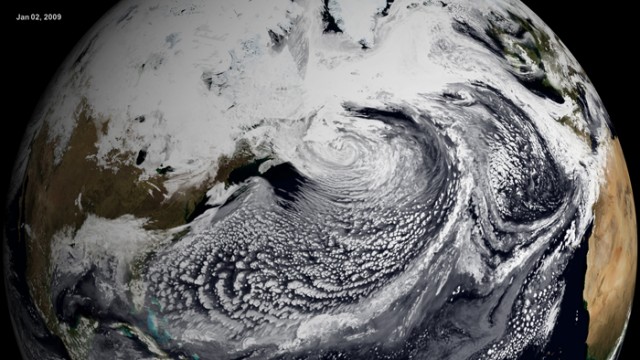

Note: I'm again here joining two recent posts. First, what it could climatically and therefore spatially, geographically, energetically, socialy, ... mean, degree after degree to increase the average temperature of the Earth and second, an information map about our warming world...

It is an unsigned paper, so it certainly need to be cross-checked, which I haven't done (time, time...)! But I post it nevertheless as it points out some believable consequences, yet very dark. As many people say now, we don't have much time left to start acting, strong (7-10 years).

Via Berens Finance (!)

-----

A degree by degree explanation of what will happen when the earth warms

-

Even if greenhouse emissions stopped overnight the concentrations already in the atmosphere would still mean a global rise of between 0.5 and 1C. A shift of a single degree is barely perceptible to human skin, but it’s not human skin we’re talking about. It’s the planet; and an average increase of one degree across its entire surface means huge changes in climatic extremes.

Six thousand years ago, when the world was one degree warmer than it is now, the American agricultural heartland around Nebraska was desert. It suffered a short reprise during the dust- bowl years of the 1930s, when the topsoil blew away and hundreds of thousands of refugees trailed through the dust to an uncertain welcome further west. The effect of one-degree warming, therefore, requires no great feat of imagination.

“The western United States once again could suffer perennial droughts, far worse than the 1930s. Deserts will reappear particularly in Nebraska, but also in eastern Montana, Wyoming and Arizona, northern Texas and Oklahoma. As dust and sandstorms turn day into night across thousands of miles of former prairie, farmsteads, roads and even entire towns will be engulfed by sand.”

What’s bad for America will be worse for poorer countries closer to the equator. It has beencalculated that a one-degree increase would eliminate fresh water from a third of the world’s land surface by 2100. Again we have seen what this means. There was an incident in the summer of 2005: One tributary fell so low that miles of exposed riverbank dried out into sand dunes, with winds whipping up thick sandstorms. As desperate villagers looked out onto baking mud instead of flowing water, the army was drafted in to ferry precious drinking water up the river – by helicopter, since most of the river was too low to be navigable by boat. The river in question was not some small, insignificant trickle in Sussex. It was the Amazon.

While tropical lands teeter on the brink, the Arctic already may have passed the point of no return. Warming near the pole is much faster than the global average, with the result that Arctic icecaps and glaciers have lost 400 cubic kilometres of ice in 40 years. Permafrost – ground that has lain frozen for thousands of years – is dissolving into mud and lakes, destabilising whole areas as the ground collapses beneath buildings, roads and pipelines. As polar bears and Inuits are being pushed off the top of the planet, previous predictions are starting to look optimistic. Earlier snowmelt means more summer heat goes into the air and ground rather than into melting snow, raising temperatures in a positive feedback effect. More dark shrubs and forest on formerly bleak tundra means still more heat is absorbed by vegetation.

Out at sea the pace is even faster. Whilst snow-covered ice reflects more than 80% of the sun’s heat, the darker ocean absorbs up to 95% of solar radiation. Once sea ice begins to melt, in other words, the process becomes self-reinforcing. More ocean surface is revealed, absorbing solar heat, raising temperatures and making it unlikelier that ice will re-form next winter. The disappearance of 720,000 square kilometres of supposedly permanent ice in a single year testifies to the rapidity of planetary change. If you have ever wondered what it will feel like when the Earth crosses a tipping point, savour the moment.

Mountains, too, are starting to come apart. In the Alps, most ground above 3,000 metres is stabilised by permafrost. In the summer of 2003, however, the melt zone climbed right up to 4,600 metres, higher than the summit of the Matterhorn and nearly as high as Mont Blanc. With the glue of millennia melting away, rocks showered down and 50 climbers died. As temperatures go on edging upwards, it won’t just be mountaineers who flee. Whole towns and villages will be at risk. Some towns, like Pontresina in eastern Switzerland, have already begun building bulwarks against landslides.

At the opposite end of the scale, low-lying atoll countries such as the Maldives will be preparing for extinction as sea levels rise, and mainland coasts – in particular the eastern US and Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean and Pacific islands and the Bay of Bengal – will be hit by stronger and stronger hurricanes as the water warms. Hurricane Katrina, which in 2005 hit New Orleans with the combined impacts of earthquake and flood, was a nightmare precursor of what the future holds.

Most striking of all was seeing how people behaved once the veneer of civilisation had been torn away. Most victims were poor and black, left to fend for themselves as the police either joined in the looting or deserted the area. Four days into the crisis, survivors were packed into the city’s Superdome, living next to overflowing toilets and rotting bodies as gangs of young men with guns seized the only food and water available. Perhaps the most memorable scene was a single military helicopter landing for just a few minutes, its crew flinging food parcels and water bottles out onto the ground before hurriedly taking off again as if from a war zone. In scenes more like a Third World refugee camp than an American urban centre, young men fought for the water as pregnant women and the elderly looked on with nothing. Don’t blame them for behaving like this, I thought. It’s what happens when people are desperate.

Chance of avoiding one degree of global warming: zero.

BETWEEN ONE AND TWO DEGREES OF WARMING

At this level, expected within 40 years, the hot European summer of 2003 will be the annual norm. Anything that could be called a heatwave thereafter will be of Saharan intensity. Even in average years, people will die of heat stress.

The first symptoms may be minor. A person will feel slightly nauseous, dizzy and irritable. It needn’t be an emergency: an hour or so lying down in a cooler area, sipping water, will cure it. But in Paris, August 2003, there were no cooler areas, especially for elderly people.

Once body temperature reaches 41C (104F) its thermoregulatory system begins to break down. Sweating ceases and breathing becomes shallow and rapid. The pulse quickens, and the victim may lapse into a coma. Unless drastic measures are taken to reduce the body’s core temperature, the brain is starved of oxygen and vital organs begin to fail. Death will be only minutes away unless the emergency services can quickly get the victim into intensive care.

These emergency services failed to save more than 10,000 French in the summer of 2003. Mortuaries ran out of space as hundreds of dead bodies were brought in each night. Across Europe as a whole, the heatwave is believed to have cost between 22,000 and 35,000 lives. Agriculture, too, was devastated. Farmers lost $12 billion worth of crops, and Portugal alone suffered $12 billion of forest-fire damage. The flows of the River Po in Italy, Rhine in Germany and Loire in France all shrank to historic lows. Barges ran aground, and there was not enough water for irrigation and hydroelectricity. Melt rates in the Alps, where some glaciers lost 10% of their mass, were not just a record – they doubled the previous record of 1998. According to the Hadley centre, more than half the European summers by 2040 will be hotter than this. Extreme summers will take a much heavier toll of human life, with body counts likely to reach hundreds of thousands. Crops will bake in the fields, and forests will die off and burn. Even so, the short-term effects may not be the worst:

From the beech forests of northern Europe to the evergreen oaks of the Mediterranean, plant growth across the whole landmass in 2003 slowed and then stopped. Instead of absorbing carbon dioxide, the stressed plants began to emit it. Around half a billion tonnes of carbon was added to the atmosphere from European plants, equivalent to a twelfth of global emissions from fossil fuels. This is a positive feedback of critical importance, because it suggests that, as temperatures rise, carbon emissions from forests and soils will also rise. If these land-based emissions are sustained over long periods, global warming could spiral out of control.

In the two-degree world, nobody will think of taking Mediterranean holidays. The movement of people from northern Europe to the Mediterranean is likely to reverse, switching eventually into a mass scramble as Saharan heatwaves sweep across the Med. People everywhere will think twice about moving to the coast. When temperatures were last between 1 and 2C higher than they are now, 125,000 years ago, sea levels were five or six metres higher too. All this “lost” water is in the polar ice that is now melting. Forecasters predict that the “tipping point” for Greenland won’t arrive until average temperatures have risen by 2.7C. The snag is that Greenland is warming much faster than the rest of the world – 2.2 times the global average. “Divide one figure by the other,” says Lynas, “and the result should ring alarm bells across the world. Greenland will tip into irreversible melt once global temperatures rise past a mere 1.2C. The ensuing sea-level ?rise will be far more than the half-metre that ?the IPCC has predicted for the end of the century. Scientists point out that sea levels at the end of the last ice age shot up by a metre every 20 years for four centuries, and that Greenland’s ice, in the words of one glaciologist, is now thinning like mad and flowing much faster than it ought to. Its biggest outflow glacier, Jakobshavn Isbrae, has thinned by 15 metres every year since 1997, and its speed of flow has doubled. At this rate the whole Greenland ice sheet would vanish within 140 years. Miami would disappear, as would most of Manhattan. Central London would be flooded. Bangkok, Bombay and Shanghai would lose most of their area. In all, half of humanity would have to move to higher ground.

Not only coastal communities will suffer. As mountains lose their glaciers, so people will lose their water supplies. The entire Indian subcontinent will be fighting for survival. As the glaciers disappear from all but the highest peaks, their runoff will cease to power the massive rivers that deliver vital freshwater to hundreds of millions. Water shortages and famine will be the result, destabilising the entire region. And this time the epicentre of the disaster won’t be India, Nepal or Bangladesh, but nuclear-armed Pakistan.

Everywhere, ecosystems will unravel as species either migrate or fall out of synch with each other. By the time global temperatures reach two degrees of warming in 2050, more than a third of all living species will face extinction.

Chance of avoiding two degrees of global warming: 93%, but only if emissions of greenhouse gases are reduced by 60% over the next 10 years.

BETWEEN TWO AND THREE DEGREES OF WARMING

Up to this point, assuming that governments have planned carefully and farmers have converted to more appropriate crops, not too many people outside subtropical Africa need have starved. Beyond two degrees, however, preventing mass starvation will be as easy as halting the cycles of the moon. First millions, then billions, of people will face an increasingly tough battle to survive.

To find anything comparable we have to go back to the Pliocene – last epoch of the Tertiary period, 3m years ago. There were no continental glaciers in the northern hemisphere (trees grew in the Arctic), and sea levels were 25 metres higher than today’s. In this kind of heat, the death of the Amazon is as inevitable as the melting of Greenland. The paper spelling it out is the very one whose apocalyptic message so shocked in 2000. Scientists at the Hadley centre feared that earlier climate models, which showed global warming as a straightforward linear progression, were too simplistic in their assumption that land and the oceans would remain inert as their temperatures rose. Correctly as it would turn out, they predicted positive feedback.

Warmer seas absorb less carbon dioxide, leaving more to accumulate in the atmosphere and intensify global warming. On land, matters would be even worse. Huge amounts of carbon are stored in the soil, the half-rotted remains of dead vegetation. The generally accepted estimate is that the soil carbon reservoir contains some 1600 gigatonnes, more than double the entire carbon content of the atmosphere. As soil warms, bacteria accelerate the breakdown of this stored carbon, releasing it into the atmosphere.

The end of the world is nigh. A three-degree increase in global temperature – possible as early as 2050 – would throw the carbon cycle into reverse. Instead of absorbing carbon dioxide, vegetation and soils start to release it. So much carbon pours into the atmosphere that it pumps up atmospheric concentrations by 250 parts per million by 2100, boosting global warming by another 1.5C. In other words, the Hadley team had discovered that carbon-cycle feedbacks could tip the planet into runaway global warming by the middle of this century – much earlier than anyone had expected.

Confirmation came from the land itself. Climate models are routinely tested against historical data. In this case, scientists checked 25 years’ worth of soil samples from 6,000 sites across the UK. The result was another black joke. As temperatures gradually rose the scientists found that huge amounts of carbon had been released naturally from the soils. They totted it all up and discovered – irony of ironies – that the 13m tonnes of carbon British soils were emitting annually was enough to wipe out all the country’s efforts to comply with the Kyoto Protocol.” All soils will be affected by the rising heat, but none as badly as the Amazon’s. “Catastrophe” is almost too small a word for the loss of the rainforest. Its 7m square kilometres produce 10% of the world’s entire photosynthetic output from plants. Drought and heat will cripple it; fire will finish it off. In human terms, the effect on the planet will be like cutting off oxygen during an asthma attack.

In the US and Australia, people will curse the climate-denying governments of Bush and Howard. No matter what later administrations may do, it will not be enough to keep the mercury down. With new “super-hurricanes” growing from the warming sea, Houston could be destroyed by 2045, and Australia will be a death trap. “Farming and food production will tip into irreversible decline. Salt water will creep up the stricken rivers, poisoning ground water. Higher temperatures mean greater evaporation, further drying out vegetation and soils, and causing huge losses from reservoirs. In state capitals, heat every year is likely to kill between 8,000 and 15,000 mainly elderly people.

It is all too easy to visualise what will happen in Africa. In Central America, too, tens of millions will have little to put on their tables. Even a moderate drought there in 2001 meant hundreds of thousands had to rely on food aid. This won’t be an option when world supplies are stretched to breaking point (grain yields decline by 10% for every degree of heat above 30C, and at 40C they are zero). Nobody need look to the US, which will have problems of its own. As the mountains lose their snow, so cities and farms in the west will lose their water and dried-out forests and grasslands will perish at the first spark.

The Indian subcontinent meanwhile will be choking on dust. All of human history shows that, given the choice between starving in situ and moving, people move. In the latter part of the century tens of millions of Pakistani citizens may be facing this choice. Pakistan may find itself joining the growing list of failed states, as civil administration collapses and armed gangs seize what little food is left.

As the land burns, so the sea will go on rising. Even by the most optimistic calculation, 80% of Arctic sea ice by now will be gone, and the rest will soon follow. New York will flood; the catastrophe that struck eastern England in 1953 will become an unremarkable regular event; and the map of the Netherlands will be torn up by the North Sea. Everywhere, starving people will be on the move – from Central America into Mexico and the US, and from Africa into Europe, where resurgent fascist parties will win votes by promising to keep them out.

Chance of avoiding three degrees of global warming: poor if the rise reaches two degrees and triggers carbon-cycle feedbacks from soils and plants.

BETWEEN THREE AND FOUR DEGREES OF WARMING

The stream of refugees will now include those fleeing from coasts to safer interiors – millions at a time when storms hit. Where they persist, coastal cities will become fortified islands. The world economy, too, will be threadbare. As direct losses, social instability and insurance payouts cascade through the system, the funds to support displaced people will be increasingly scarce. Sea levels will be rampaging upwards – in this temperature range, both poles are certain to melt, causing an eventual rise of 50 metres. “I am not suggesting it would be instantaneous. In fact it would take centuries, and probably millennia, to melt all of the Antarctic’s ice. But it could yield sea-level rises of a metre or so every 20 years – far beyond our capacity to adapt.Oxford would sit on one of many coastlines in a UK reduced to an archipelago of tiny islands.