Sticky Postings

All 242 fabric | rblg updated tags | #fabric|ch #wandering #reading

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Tuesday, December 23. 2014

Can Sucking CO2 Out of the Atmosphere Really Work? | #atmosphere

-----

A Columbia scientist and his startup think they have a plan to save the world. Now they have to convince the rest of us.

By Eli Kintish

CTO and co-founder Peter Eisenberger in front of Global Thermostat’s air-capturing machine.

Physicist Peter Eisenberger had expected colleagues to react to his idea with skepticism. He was claiming, after all, to have invented a machine that could clean the atmosphere of its excess carbon dioxide, making the gas into fuel or storing it underground. And the Columbia University scientist was aware that naming his two-year-old startup Global Thermostat hadn’t exactly been an exercise in humility.

But the reception in the spring of 2009 had been even more dismissive than he had expected. First, he spoke to a special committee convened by the American Physical Society to review possible ways of reducing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere through so-called air capture, which means, essentially, scrubbing it from the sky. They listened politely to his presentation but barely asked any questions. A few weeks later he spoke at the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory in West Virginia to a similarly skeptical audience. Eisenberger explained that his lab’s research involves chemicals called amines that are already used to capture concentrated carbon dioxide emitted from fossil-fuel power plants. This same amine-based technology, he said, also showed potential for the far more difficult and ambitious task of capturing the gas from the open air, where carbon dioxide is found at concentrations of 400 parts per million. That’s up to 300 times more diffuse than in power plant smokestacks. But Eisenberger argued that he had a simple design for achieving the feat in a cost-effective way, in part because of the way he would recycle the amines. “That didn’t even register,” he recalls. “I felt a lot of people were pissing on me.”

The next day, however, a manager from the lab called him excitedly. The DOE scientists had realized that amine samples sitting around the lab had been bonding with carbon dioxide at room temperature—a fact they hadn’t much appreciated until then. It meant that Eisenberger’s approach to air capture was at least “feasible,” says one of the DOE lab’s chemists, Mac Gray.

Five years later, Eisenberger’s company has raised $24 million in investments, built a working demonstration plant, and struck deals to supply at least one customer with carbon dioxide harvested from the sky. But the next challenge is proving that the technology could have a transformative impact on the world, befitting his company’s name.

The need for a carbon-sucking machine is easy to see. Most technologies for mitigating carbon dioxide work only where the gas is emitted in large concentrations, as in power plants. But air-capture machines, installed anywhere on earth, could deal with the 52 percent of carbon-dioxide emissions that are caused by distributed, smaller sources like cars, farms, and homes. Secondly, air capture, if it ever becomes practical, could gradually reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. As emissions have accelerated—they’re now rising at 2 percent per year, twice as rapidly as they did in the last three decades of the 20th century—scientists have begun to recognize the urgency of achieving so-called “negative emissions.”

The obvious need for the technology has enticed several other efforts to come up with various approaches that might be practical. For example, Climate Engineering, based in Calgary, captures carbon using a liquid solution of sodium hydroxide, a well-established industrial technique. A firm cofounded by an early pioneer of the idea, Eisenberg’s Columbia colleague Klaus Lackner, worked on the problem for several years before giving up in 2012.

“Negative emissions are definitely needed to restore the atmosphere given that we’re going to far exceed any safe limit for CO2, if there is one. The question in my mind is, can it be done in an economical way?”

A report released in April by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that avoiding the internationally agreed upon goal of 2 °C of global warming will likely require the global deployment of “carbon dioxide removal” strategies like air capture. (See “The Cost of Limiting Climate Change Could Double without Carbon Capture Technology.”) “Negative emissions are definitely needed to restore the atmosphere given that we’re going to far exceed any safe limit for CO2, if there is one,” says Daniel Schrag, director of the Harvard University Center for the Environment. “The question in my mind is, can it be done in an economical way?”

Most experts are skeptical. (See “What Carbon Capture Can’t Do.”) A 2011 report by the American Physical Society identified key physical and economic challenges. The fact that carbon dioxide will bind with amines, forming a molecule called a carbamate, is well known chemistry. But carbon dioxide still represents only one in 2,500 molecules in the air. That means an effective air-capture machine would need to push vast amounts of air past amines to get enough carbon dioxide to stick to them and then regenerate the amines to capture more. That would require a lot of energy and thus be very expensive, the 2011 report said. That’s why it concluded that air capture “is not currently an economically viable approach to mitigating climate change.”

The people at Global Thermostat understand these daunting economics but remain defiantly optimistic. The way to make air capture profitable, says Global Thermostat cofounder Graciela Chichilnisky, a Columbia University economist and mathematician, is to take advantage of the demand for the gas by various industries. There already exists a well-established, billion-dollar market for carbon dioxide, which is used to rejuvenate oil wells, make carbonated beverages, and stimulate plant growth in commercial greenhouses. Historically, the gas sells for around $100 per ton. But Eisenberger says his company’s prototype machine could extract a concentrated ton of the gas for far less than that. The idea is to first sell carbon dioxide to niche markets, such as oil-well recovery, to eventually create bigger ones, like using catalysts to make fuels in processes that are driven by solar energy. “Once capturing carbon from the air is profitable, people acting in their own self-interest will make it happen,” says Chichilnisky.

Warming up

Eisenberger and Chichilnisky were colleagues at Columbia in 2008 when they realized that they had complementary interests: his in energy, and hers in environmental economics, including work to help shape the 1991 Kyoto Protocol, the first global treaty on cutting emissions. Nations had pledged big cuts, says Chichilnisky, but economic and political realities had provided “no way to implement it.” The pair decided to create a business to tackle the carbon challenge.

They focused on air capture, which was first developed by Nazi scientists who used liquid sorbents to remove accumulations of CO2 in submarines. In the winter of 2008 Eisenberger sequestered himself in a quiet house with big glass windows overlooking the ocean in Mendocino County, California. There he studied existing literature on capturing carbon and made a key decision. Scientists developing techniques to capture CO2 have thus far sought to work at high concentrations of the gas. But Eisenberger and Chichilnisky focused on another term in those equations: temperature.

Engineers have previously deployed amines to scrub CO2 from flue gases, whose temperatures are around 70 °C when they exit power plants. Subsequently removing the CO2 from the amines—“regenerating” the amines—generally requires reactions at 120 °C. By contrast, Eisenberger calculated that his system would operate at roughly 85 °C, requiring less total energy. It would use relatively cheap steam for two purposes. The steam would heat the surface, driving the CO2 off the amines to be collected, while also blowing CO2 away from the surface.

"Even if air capture were to someday prove profitable, whether it should be scaled up is another question."

The upshot? With less heat-management infrastructure than what is required with amines in the smokestacks of power plants, the design of a scrubber could be simpler and therefore cheaper. Using data from their prototype, Eisenberger’s team figures the approach could cost between $15 and $50 per ton of carbon dioxide captured from air, depending on how long the amine surfaces last.

If Global Thermostat can achieve anywhere near the prices it’s touting, a number of niche markets beckon. The startup has partnered with a Carson City, Nevada-based company called Algae Systems to make biofuels using carbon dioxide and algae. Meanwhile the demand is rising for carbon dioxide to inject into depleted oil wells, a technique known as enhanced oil recovery. One study estimates that the application could require as much as 3 billion tons of carbon dioxide annually by 2021, a nearly tenfold increase over the 2011 market.

That still represents a drop in the bucket in terms of the amounts needed to reduce or even stabilize the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere. But Eisenberger says there are really no alternatives to air capture. Simply capturing carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants, he says, only extends society’s dependence on carbon-intensive coal.

Suck it up

It’s a warm December afternoon in Silicon Valley as Eisenberger and I make our way across SRI International’s concrete research center. It’s in these low-slung buildings where engineers first developed ARPAnet, Apple’s Siri software, and countless other technological advances. About a quarter mile from the entrance, a 40-foot-high tower of fans, steel, and silver tubes comes into view. This is the Global Thermostat demonstration plant. It’s imposing and clean. Eisenberger gazes at the quiet scene around the tower, which includes a tall tree. “It’s doing exactly what the tree is doing,” says Eisenberger. But then he corrects himself. “Well, actually, it’s doing it a lot better.”

After Eisenberger earned a PhD physics in 1967 at Harvard, stints at Bell Labs, Princeton, and Stanford followed. At Exxon in the 1980s he led work on solar energy, then served as director of Lamont-Doherty, the geosciences lab at Columbia. There he has taught a long-standing seminar called “The Earth/Human system.” It was in that seminar, in 2007, with Lackner as a guest lecturer, that Eisenberger first heard about air capture. After a year or so of preparation, he and Chichilnisky reached out to billionaire Edgar Bronfman Jr. “Sometimes when you hear something that must be too good to be true, it’s because it is,” was Bronfman’s reaction, according to his son, who was present at the meeting. But the scion implored his father: “If they’re right, this is one of the biggest opportunities out there.” The family invested $18 million.

That largesse has allowed the company to build its demonstration despite basically no federal support for air capture research. (Global Thermostat chose SRI as its site due to the facility’s prior experience with carbon-capture technology.) The rectangular tower uses fans to draw air in over alternating 10-foot-wide surfaces known as contactors. Each is comprised of 640 ceramic cubes embedded with the amine sorbent. The tower raises one contactor as another is lowered. That allows the cubes of one to collect CO2 from ambient air while the other is stripped of the gas by the application of the steam, at 85 °C. For now that gas is simply vented, but depending on the customer it could be injected into the ground, shipped by pipe, or transferred to a chemical plant for industrial use.

A key challenge facing the company is the ruggedness of the amine sorbent surfaces. They tend to decay rapidly when oxidized, and frequently replacing the sorbents could make the process much less cost-effective than Eisenberger projects.

False hope

None of the world’s thousands of coal plants have been outfitted for full-scale capture of their carbon pollution. And if it isn’t economical for use in power plants, with their concentrated source of carbon dioxide, the prospects of capturing it out of the air seem dim to many experts. “There’s really little chance that you could capture CO2 from ambient air more cheaply than from a coal plant, where the flue gas is 300 times more concentrated,” says Robert Socolow, director of the Princeton Environment Institute and co-director of the university’s carbon mitigation initiative.

Adding to the skepticism over the feasibility of air capture is that there are other, cheaper ways to create the so-called negative emissions. A more practical way to do it, Schrag says, would involve deriving fuels from biomass—which removes CO2 from the atmosphere as it grows. As that feedstock is fermented in a reactor to create ethanol, it produces a stream of pure carbon dioxide that can be captured and stored underground. It’s a proven technique and has been tested at a handful of sites worldwide.

Even if air capture were to someday prove profitable, whether it should be scaled up is another question. Say a solar power plant is built outside an existing coal plant. Should the energy the new solar plant produces be used to suck carbon out of the atmosphere, or to allow the coal plant to be shut down by replacing its energy output? The latter makes much more sense, says Socolow. He and others have another concern about air capture: that claims about its feasibility could breed complacency. “I don’t want us to give people the false hope that air capture can solve the carbon emissions problem without a strong focus on [reducing the use of] fossil fuels,” he says.

Eisenberger and Chichilnisky are adamant about the importance of sucking CO2 out of the atmosphere rather than focusing entirely on capturing it from coal plants. In 2010, the pair developed a version of their technology that mixes air with flue gas from a coal or gas-fired power plant. That approach provides a source of steam while capturing both atmospheric carbon and new emissions. It also could lower costs by providing a higher concentration of CO2 for the machine to capture. “It’s a very impressive system, a triumph,” says Socolow, who thinks scientific advances made in air capture will eventually be used primarily on coal and gas power plants.

Such an application could play a critical role in cleaning up greenhouse gas emissions. But Eisenberger has revealed even loftier goals. A patent granted to him and Chichilnisky in 2008 described air capture technology as, among other things, “a global thermostat for controlling average temperature of a planet’s atmosphere.”

Eli Kintisch is a correspondent for Science magazine.

Related Links:

Wednesday, October 08. 2014

Desierto Issue #3 - 28° Celsius is out! Deterritorialized Living included | #atmosphere

Note: a few of our recent works and exhibitions are included in this promising young publication related to architectural thinking, Desierto, edited by Paper - Architectural Histamine in Madrid. At the editorial team invitation, I had the occasion to write a paper about Deterritorialized Living and one of its physical installation last year in Pau (France), during Pau Acces(s). We also took the occasion of the publication to give a glimpse of a related research project called Algorithmic Atomized Functioning.

By fabric | ch

-----

From the editorial team:

"The temperature of the invisible and the desacralization of the air. 28° Celsius is the temperature at which protection becomes superfluous. It is also the temperature at which swimming pools are acclimatised.

Within the limits of the this hygrothermal comfort zone, we do not require the intervention of our body's thermoregulatory mechanisms nor that of any external artificial thermal controls in order to feel pleasantly comfortable while carrying out a sedentary activity without clothing.

28° Celsius is thus the temperature at which clothing can disappear, just as architecture could."

.jpg)

.jpg)

Authors are Gabriel Ruiz-Larrea, Sean Lally, Philippe Rahm, Nerea Calvillo, myself, Helen Mallinson, Antonio Cobo, José Vella Castillo and Pauly Garcia-Masedo.

.jpg)

Editorial by gabriel Ruiz-Larrea (editor in chief). Editorial team composed of Natalia David, Nuria Úrculo, María Buey, Daniel Lacasta Fitzsimmons.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

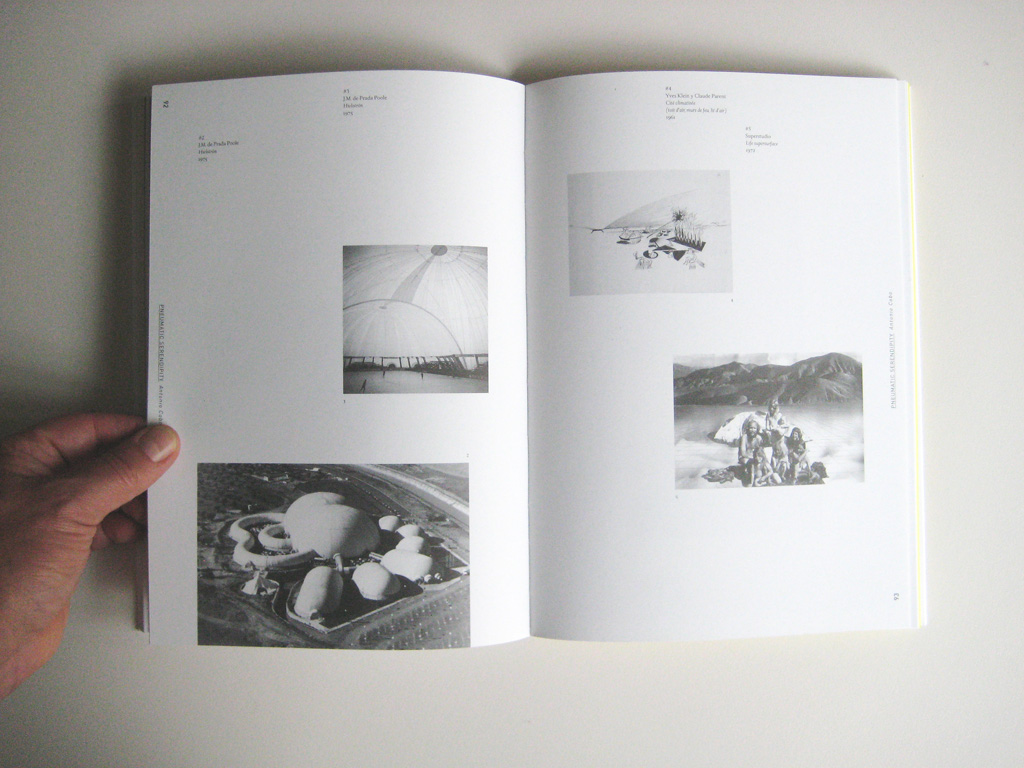

Inhabiting Deterritorialization, by Patrick Keller, with images of Deterritorialized Living website, Deterritorialized Daylight installation (Pau, France) and Algorithmic Atomized Functioning.

Desierto #3 and past issues can be ordered online on Paper bookstore.

Thursday, April 17. 2014

Air pollution now the world’s biggest environmental health risk with 7 million deaths per year | #air #health

Following last month catastrophic measures in Paris. Not a funny information, yet good to know. Air quality will undoubtedly become a very big (geo)political issue in the coming years, certainly an engineering one too.

Via Treehugger

-----

CC BY-ND 2.0 Flickr

The World Health Organization (WHO) released a report last year showing that air pollution killed more people than AIDS and malaria combined. It was based on 2010 figures, which were the latest available at the time. There's now a new study which looked at 2012 data, and it seems like things are even worse than we first believed.

“The risks from air pollution are now far greater than previously thought or understood, particularly for heart disease and strokes,” says Dr Maria Neira, Director of WHO’s Department for Public Health, Environmental and Social Determinants of Health. “Few risks have a greater impact on global health today than air pollution; the evidence signals the need for concerted action to clean up the air we all breathe.”

The WHO found that outdoor air pollution was linked to an estimated 3.7 million deaths in 2012 from urban and rural sources worldwide, and indoor air pollution, mostly caused by cooking (!) on inefficient coal and biomass stoves was linked to 4.3 million deaths in 2012.

Because many people are exposed to both indoor and outdoor air pollution, there is overlap in these two numbers, but the WHO estimates that the total number of victims from air pollution in 2012 was around 7 million, which is tragic since it would take relatively little in many of those cases to save livesFlickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

And it's not really a question of money, since the health costs and lost productivity caused by air pollution are higher in the long-term...

Here's how the health impacts break down for both indoor and outdoor air pollution:

Outdoor air pollution-caused deaths – breakdown by disease:

- 40% – ischaemic heart disease;

- 40% – stroke;

- 11% – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD);

- 6% - lung cancer; and

- 3% – acute lower respiratory infections in children.

Indoor air pollution-caused deaths – breakdown by disease:

- 34% - stroke;

- 26% - ischaemic heart disease;

- 22% - COPD;

- 12% - acute lower respiratory infections in children; and

- 6% - lung cancer

There are lots of big obvious things we can do, such as replace inefficient and pollution small stoves in poorer countries with better stoves or even better, electric cooking. Many countries, like China, could also do a lot to cut pollution at their coal plants and over time phase out coal (which isn't just a problem for air pollution, but also for water and ground pollution and global warming). There are all these low-hanging fruits that would make a huge difference. To see how dramatic the improvement could be, just look at these photos showing how bad the situation was in the US not so long ago (China is just repeating what has gone on elsewhere...).

One thing we can do to help: plant more trees! Recent studies show that they are even better at filtering the air in urban areas than we previously thought.

© Michael Graham Richard

Related on TreeHugger.com:

- Think Air Quality Regulations Don't Matter? Look at Pittsburgh in the 1940s!

- This scary map shows the health impacts of coal power plants in China

- The smog in Los Angeles doesn't quite sting like it used to, but there's still work to be done

- Coal pollution in China lowers life expectancy by 5 years

- What kills more people than AIDS and malaria combined? Air pollution

- Trees are awesome: Study shows tree leaves can capture 50%+ of particulate matter pollution

Tuesday, March 18. 2014

Airships and atmosphere | #airship #satellite

-----

Airships can patrol the upper atmosphere, monitoring the ground or peering at the stars for a fraction of a cost of satellites, according to a new report. All that’s needed is a prize to kick-start innovation.

The Naval Air Engineering Station in Lakehurst New Jersey must be one of the most famous airfields in the world. If you’ve ever watched the extraordinary footage of the German passenger airship Hindenburg catching fire as it attempted to moor, you’ll have seen Lakehurst. That’s where the disaster took place.

Despite its notorious past, Lakehurst is still a center of airship engineering and technology. In 2012, it was home to the Long Endurance Multi-Intelligence Vehicle, an airship designed and built for the U.S. military to use for surveillance purposes over Afghanistan.

The vehicle is colossal—91 meters long, 34 meters wide, and 26 meters high, about the size of a 30 story office block lying on its side. And it is designed to fly uncrewed at about 10 kilometers for up to three weeks at a time. (Last year, the program was canceled and the airship sold back to the British contractor that built it, which now intends to fly it commercially.)

This ambitious program and a few others like it mostly funded by the U.S. military, have attracted some jealous glances from scientists. The ability to fly at 20 kilometers or more for extended periods of time could be hugely useful.

Fitted with cameras that scan the ground, sensors that monitor the atmosphere or telescopes that point to the stars, these observatories could revolutionize the kind of data researchers are able to gather about the universe.

Today, Sarah Miller and few pals have prepared a report for the Keck Institute of Space Studies in Pasadena suggesting that scientists have unnecessarily ignored the advantages of airships and that the time is right for a new era of science based on this capability.

The problem, of course, is that airships capable of these missions have not yet been built. Most of the well-funded development has come from the military for long duration surveillance missions. But with the end of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the downsizing of the U.S. military machine, this funding has dried up.

But Miller and co have a suggestion. They say that innovation in this area could be stimulated by setting up a prize for the development of a next-generation airship, just as the X-Prize stimulated interest in reusable rocket flights. The goal, they say, should be to build a maneuverable, stationed-keeping airship that can stay aloft at an altitude of more than 20 km from least 20 hours while carrying a science payload of a least 20 kg.

That’s a significant challenge. One problem will be carrying or generating the power required to propel the airship. This increases with the cube of its airspeed and so will be the biggest drain on the vehicle’s resources.

Another challenge is to handle the thermal loads at this altitude, where temperatures can vary by as much as 50 °C and where there is little air to carry heat away.

But none of these problems look like showstoppers. Given the right kind of incentives, it should be possible to put one of these things in the air in the very near future, perhaps based on the technology developed for vehicles like the Long Endurance Multi-Intelligence Vehicle.

All that’s needed is a sponsor willing to cough up a few million dollars for a prize. Anybody with a few bucks to spare?

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1402.6706 : AIRSHIPS : A New Horizon for Science.

Related Links:

Personal comment:

In regard of the now necessary needs to monitor our man transformed atmosphere... (and not only to have universal Internet access provided by private companies), a fully artificial need, the creation of such blimp-drones would be interesting. Yet I totally disagree with the fact that this should be a private initiative. It is capital to my understanding that it remains public, in the hands of the public and driven by public technology (including the monitored data).

If this won't be the case, what I can see is the commodification of air and upper atmosphere, like human interactions have been commodified through social networks (you know, the "data problem") or many slightly modified genes are in the process to be. We can see the very problematic outcomes of this "neo-liberal only" attitude today, with data and our (digital) selves that are sold and turned into products.

So, please, let's keep it public infrastructrure.

Saturday, November 23. 2013

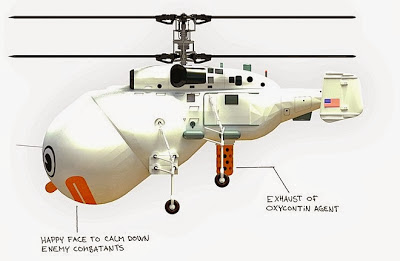

Vers une nouvelle approche du drone? | #drones

Note: here comes the "peace drone"!

Via Transit-City

-----

En découvrant ce projet je n'ai pas pu m'empêcher de penser à la parade imaginée par le Joker dans le Batman de Tim Burton, au cours de laquelle il espère pouvoir diffuser son fameux gaz vert, l'Hilarex, pour prendre le contrôle de Gotham City.

Ou quand une certaine pop culture permet d'aborder un peu autrement les nouvelles fonctions et les nouvelles formes possibles des drones et de leurs dérivés dans le futur. Pour rester dans le ludique, voir par exemple là pour les drones, et là pour les ballons.

Related Links:

Friday, June 14. 2013

Harmony cannot be obvious

Via Domusweb

-----

By Jack Self

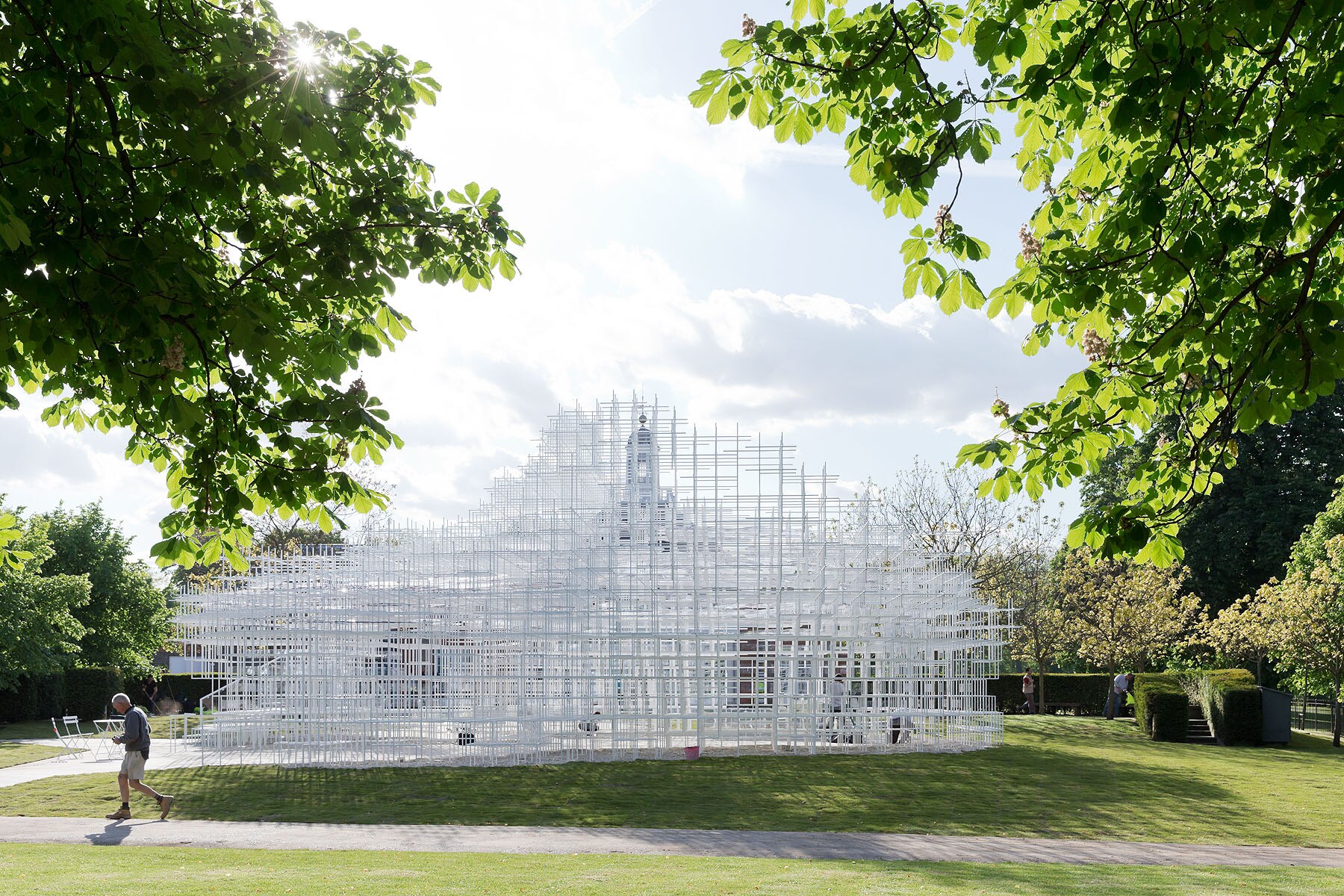

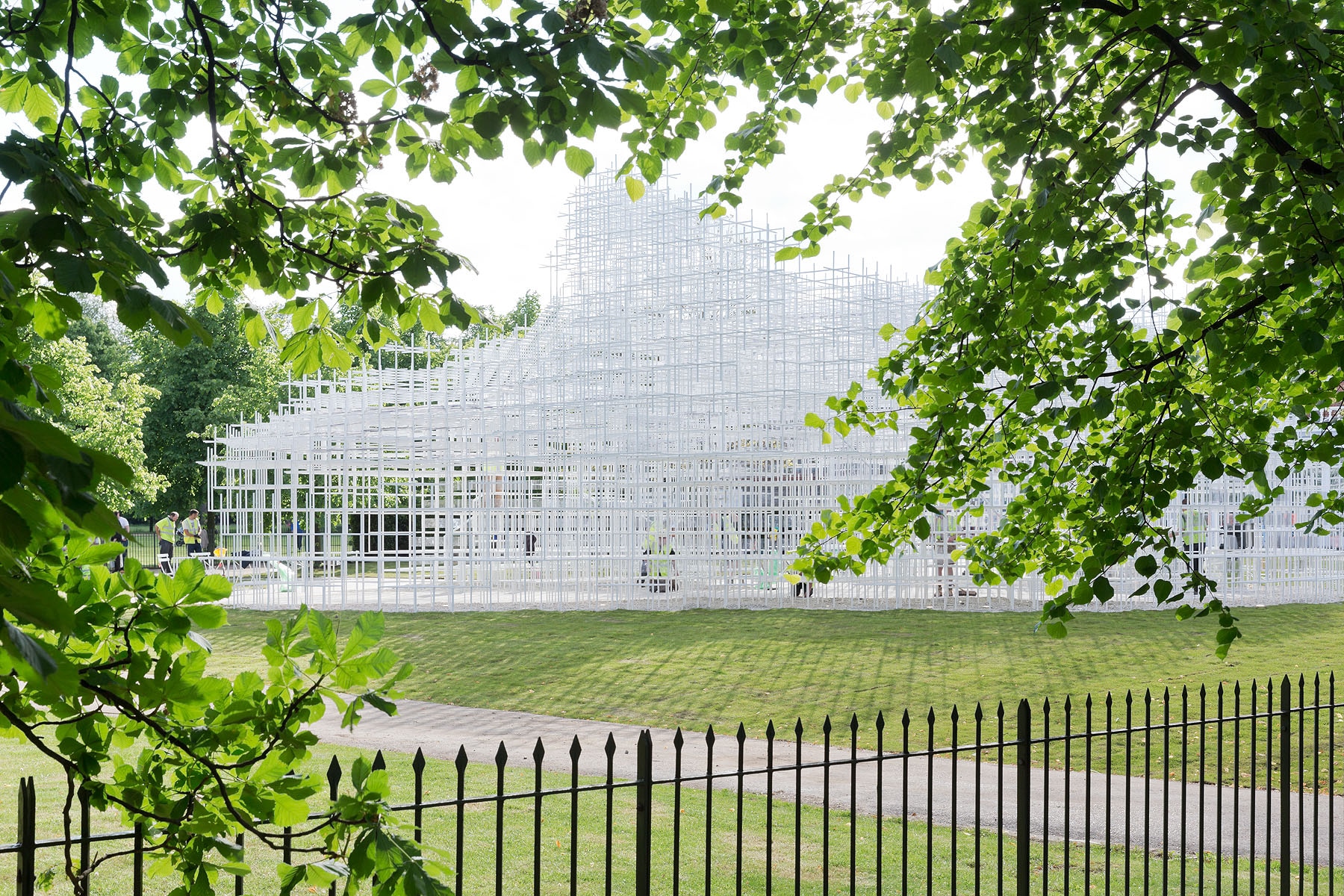

Rather than a mere folly, Sou Fujimoto's Serpentine Pavilion is sincere in his proposition about the future of architecture and its place in the world.

If Vivaldi’s Summer is the architectural high-season, then the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion is its opening refrain — a measured, majestic transition from the long British winter to the frenetic hyperactivity and crystalline skies of summer proper.

Perhaps for this reason the Pavilion always attracts a certain sleepy journalism, as though the whole press hadn’t yet had their morning coffee. One reads endless tales recounted as though written in a half-waking state — soggy with dream-like odes and fanciful metaphors, rambling and extravagant, but almost universally uncritical.

On the rare occasion that a pavilion does get bad press, it is invariably childish insults hurled at the architect with a kind of impertinent bad-temperedness: “Nouvel resembles an ageing bouncer,” (Edwin Heathcote, FT) “I smell Jean Nouvel before I see him,” (Tom Dykhoff, The Times) “A one idea building from a once extraordinary architect” (Ellis Woodman, The Telegraph). In fact, although Nouvel’s 2010 shape-shifting red pavilion was received terribly, it remains the only attempt to broaden public engagement beyond the over-priced Fortnum & Mason’s coffee bar. With free kite flying, table tennis, chess and checkers, it became for a short period the only building in all of Knightsbridge that didn’t force you to spend money to enjoy its amenities.

Top and above: Sou Fujimoto, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2013

More importantly, critique of the Serpentine Pavilion as an institutional project is totally absent. Inasmuch as the media accept or reject this or that form, it amounts to whim. We must name the Serpentine Pavilion for what it is: a star factory whose elitist self-perpetuation typifies the vapid iconicity of the pre-Crash years. This is a massive work of architectural branding, or at best, architecture-as-sculpture.

At the core of the whole project is a profound question about the intended benefactor of all these pavilions. For architects, the project’s ambition of providing a platform for little-known practitioners operates like a last-chance saloon for the already established. The category of never having built in the UK only increases the uniqueness of the bijou. For visitors, the pavilions do not serve any obvious purpose beyond to be looked at. Yet most passers-by do not actually spend much time looking at all (about four to six minutes). Presumably many are put off by spaces always focussed around a hopelessly over-staffed bar of well-dressed waiters, patiently expecting you to buy a £3 Americano.

The only entity that really profits from the pavilions is of course the gallery itself. Beyond the empty rhetoric, it is publicity for the sake of publicity.

Sou Fujimoto, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2013

All this is unfortunate really, because Sou Fujimoto’s nebulous pavilion is possibly the finest yet. Rather than a mere folly, Fujimoto is sincere in his proposition about the future of architecture and its place in the world. A polite, quiet, deferential man, he speaks slowly, but explains himself with eloquence and a precise clarity. I quickly notice a pattern in the way he responds to questions: first a tactful and positive remark, then his opinion.

I asked him who the structure was really for, and what was its purpose. He said, “It is for the people of London, and visitors of many different nations, to behave nicely in this park.”

After a pause he added in a lower tone, “Of course, we have some other ideas which are not about today but about the future urban environment. A pavilion of this size should not be concerned with super-practical things, because that can limit its life to the present. It should not be for now, but for 20 or 50 years later. People can imagine how such a living environment could be the future city, or future house, or the future park. I like to create such imaginings, and I hope people just casually enjoy this dream of architecture’s potential.”

He spoke about Corbusier, and how influenced he had been by the Modular. A simple unit based on the body, he said, had great power to harmonise, or integrate, differing scales. Corbusier was also remarkable for how he used small projects to express powerful ideas. Then he spoke about how Toyo Ito’s 2002 pavilion generated a lot of interest in Japan, heightened by SANAA in 2009. I got the impression that for Fujimoto the pavilion represented a platform; a coded message; a statement of intent pointed at his own country (as much as to anywhere, or anyone, else). When I asked if he had plans to build again in Britain he gave me a look of slight bemusement. “I like the UK a lot, and I feel very welcomed here.” The pause. “I do not have any current intentions of building here.” Would you though? “My work for the moment is in Japan.”

Sou Fujimoto, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2013

For an outsider, Japan’s complex social order can be at times impenetrable. Certainly though, something that has always struck me is the traditional continuity between generations of architects — where in the West each younger generation has to forcefully overthrow, reject (even denounce) their elders, the Japanese seem harmonious and respectful.

On the contrary, Kengo Kuma told me recently that just because he goes for Sake and Karaoke with Ito and Sejima (his words), it doesn’t mean he won’t take advantage of any opportunity to distinguish himself and declare his independence. As the youngest Japanese architect to do a pavilion, how did Fujimoto relate to this type of culture, with respect to Ito and SANAA?

“Actually, we have a nice relationship between the generations. I myself didn’t work for Ito-san, or SANAA, but they are very open and generous. They appreciate and elevate the young. They like to know what’s next, and what is the younger energy. That’s really great. We get such nice support.” Pause. “At the same time, we discuss architecture.”

Sou Fujimoto, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2013

I asked if that made it difficult to disagree? “We don’t have to just say yes. Sometimes we propose our opinion or objections, and that makes the relationship founded on mutual trust. If you just say yes all the time, it means that in a different condition you might say no, and that damages trust. We can enjoy these types of talks. They’re not fights. I am now 41, and the younger generation is coming up, and some of them are quite talented. So we have a responsibility to those who are younger, to support them and encourage them, just as I have seen Ito-san, or Sejima-san’s attitude to make the whole atmosphere of architecture in Japan more energetic, and more active.”

As you manoeuvre around the pavilion the form changes quite radically, and in a sense it is quite hard to say what shape it is. Normally, the architectural press (and Serpentine Gallery) don’t like shapeless pavilions, as though each building must be reducible to its own 32-pixel icon. Unlike Nouvel, the response to Fujimoto has been overwhelmingly positive, which led me to think there might be different kinds of formlessness.

Sou Fujimoto, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2013

“I agree. I personally saw Nouvel’s pavilion,” says Fujimoto. “From far away, it was a red square on a green background; it was quite beautiful. Inside, you couldn’t easily understand the form, or how the structure worked, or how the spaces were made. It was just red, and then less red, and then more red... I really like such an approach to architecture, that doesn’t focus on the form of the object, but on the qualities of the subjective experience, and I was fascinated by that.”

He continues. “For me, it was important to produce a structure that definitely had a shape, but one that was ambiguous. If you are outside the pavilion, this shape should be blurry. From different directions you should have completely different impressions. If you are inside, the object should disappear, it should be a gradient of shifting densities and transparencies. From some directions it is more like a floating cloud, and then from others more of a forest, or a group of trees. These are harmonious qualities, but they must be approached very carefully, it cannot be too strong. Harmony cannot be obvious.” Jack Self (@jack_self)

Sou Fujimoto, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2013

Related Links:

Friday, January 18. 2013

The Cloud Machine – A Personalized Weather Modification Prototype

While airship construction is not generally within the purview of media artists, a recent project by Karolina Sobecka makes a compelling case for floating personalized weather modification devices up towards the stratosphere. The Cloud Machine is a composite weather balloon and rudimentary cloud seeding apparatus that can create small clouds and make subtle alterations to the atmosphere in the process.

More about it on Creative Applications.

Related Links:

Monday, December 31. 2012

Here are some balloons, they are floating

William Forsythe: Scattered Crowds

We’ve seen some fantastic installation art recently, ranging from the Interactive Thunderstorm in Philadelphia, to The Rain Room in London. And now – joy of joys – we’re reflecting on more amazing installation art for y’all to dive into. This time we’re in the Bockenhelmer Depot, in Frankfurt, Germany. Ready? Right, let’s GO!

The magical spacial installation Scattered Crowds was conceived of by multi-disciplinary artist William Forsythe. Thousands of white balloons are suspended in the air, accompanied by a wash of music, emphasising “the air-borne landscape of relationships, distance, of humans and emptiness, of coalescence and decision”. Obviously, keep your eyes open and finish reading my little post, but this installation is well worth taking five; Put some tunes on and visualise your world surrounded by balloons. What would you do? How would you move?

And that’s the physical point of the installation – you’re forced to interact with each balloon which requires effort to manoeuvre, dodge, dance pass, or simply run headlong through like a sexually charged elephant. William’s installation draws this out of everybody who interacts with it, replicating the emotions and decisions of people. With this in mind, please – no pins!

William Forsythe: Scattered Crowds

William Forsythe: Scattered Crowds

William Forsythe: Scattered Crowds

William Forsythe: Scattered Crowds

William Forsythe: Scattered Crowds

Related Links:

Friday, December 21. 2012

A portrait of Earth’s dirty atmosphere

Via ExtremTech

-----

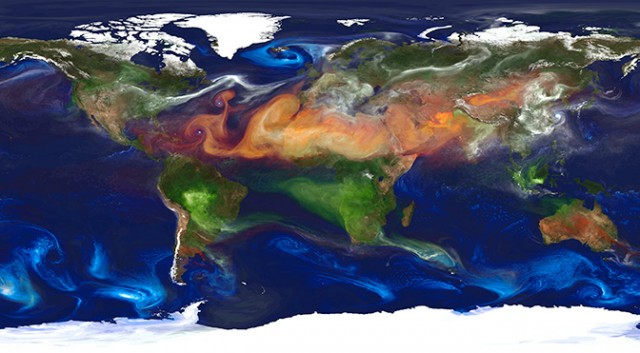

Here’s a mind-blowing view of the Earth that you’ve probably never seen — or even thought of — before. Dubbed “Portrait of Global Aerosols” by NASA, this is the kind of imagery that climate scientists use to analyze the Earth’s atmosphere, the weather, and trends such as global climate change.

Now, first things first: The Earth doesn’t actually look like this from space (alas). Rather, this is an image output by the Goddard Earth Observation System Model, version 5 (GEOS-5). GEOS-5 is an almighty piece of software that runs on a supercomputer at NASA’s Center for Climate Simulation in Maryland.

In the case of this image, GEOS-5 is modeling the presence of aerosols (solid or liquid particles suspended in gas) across the Earth’s atmosphere. Each of the colors represents a different aerosol: Red is dust (swept up from deserts, like the Sahara); Blue is sea salt, swirling inside cyclones; Green is smoke from forest fires; and white is sulfates, which bubble forth from volcanoes — and from burning fossil fuels. The full-size version of the image is particularly mesmerizing, with beautiful swirls of Saharan sand in the Atlantic, and perhaps the tail end of the Gulf Stream circling around Iceland.

It’s hard to be certain, but it seems like the US east coast, central Europe, and east Asia are burning a lot of fossil fuels. Japan, of course, sits on the edge of the Pacific Ring of Fire, so the sulfates there could be from volcanoes. The smoke in Australia is probably from forest fires — but the large volume of smoke from the Amazon rain forest and sub-Saharan Africa is curious. Are these forest fires, or the large-scale burning of wood for heat and power?

As you can imagine, the amount of raw data required to produce such imagery is immense. Weather modeling is still one of the primary uses of supercomputers. To create the Portrait of Global Aerosols, GEOS-5 will have aggregated the measurements from hundreds of weather stations across Earth, along with data from the four NASA/NOAA GOES weather satellites. So you have some idea of the complexity of the GEOS-5 model, the resolution of this image is 10 kilometers (6 miles) — meaning the Earth has been split into regions (“pixels”) of 10km2, and then the atmospheric conditions are simulated for each region. The surface area of the Earth is 510,072,000km2, which means the total number of regions is around 5 million.

Each of these 5 million pixels might have megabytes or gigabytes of weather data associated with it — and of course, in any given area, the weather in each pixel interacts with those around it. This gives you some idea of how much data needs to be processed and moved around — and it only becomes exponentially more complex as sensors improve (producing more data) and as you increase the depth of your analysis. In the case of climate change, for example, scientists are modeling decades or even centuries of data to try and divine some kind of pattern — a task that taxes even the most powerful supercomputers. If you’ve ever wondered why we keep building faster and faster supercomputers, now you know why.

Now read: What can you actually do with a supercomputer?

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.

Quicksearch

Categories

Calendar

|

|

July '25 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||