Sticky Postings

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Wednesday, January 27. 2016

Via Motherboard (via @jospeh_grima)

-----

Screengrab: The Torist

Anonymity is a breeding ground, be that for debate, creativity, or exploration. So where better to publish a socially-conscious, digitally focused literary journal (.onion link) than on a Tor hidden service.

Edited by Robert W. Gehl, associate professor at the University of Utah's Department of Communication, and pseudonymous creator GMH, the first issue of The Torist, a collection of fiction, poetry and non-fiction, launched on the dark web over the weekend.

The project started on Galaxy, a social network on the dark web, around 18 months ago, the pair told Motherboard in encrypted chats. GMH and Gehl, who was using his own pseudonym at this point, were discussing issues around feminism and literature.

“At the time, I was quite enthused about Galaxy and the way this social network had a different atmosphere from other social networks I'd used on the clearweb,” GMH said. “I thought that this different atmosphere/demographic could translate into a 'zine with interesting results.” People on Galaxy, GMH said, seemed to be dissatisfied with being constantly monetized, and not having a sense of other places to go.

The editors pose several questions in a preface to the journal: “If a magazine publishes itself via a Tor hidden service, what does the creative output look like? How might it contrast itself with its clearweb counterparts? Who indeed will gravitate towards a dark web literary maagzine?”

Indeed, reading the contents of the journal together, “I see the anxieties of life in a surveillance state,” Gehl said.

Gehl, after being pitched the idea of The Torist by GMH, decided to strip away his pseudonym, and work on the project under his own name. “I thought about that for a while,” Gehl said. “I thought that because GMH is anonymous/pseudonymous, and he's running the servers, I could be a sort of ‘clear’ liason.”

So while Gehl used his name, and added legitimacy to the project in that way, GMH could continue to work with the freedom the anonymity awards. “I guess it's easier to explore ideas and not worry as much how it turns out,” said GMH, who described himself as someone with a past studying the humanities, and playing with technology in his spare time.

One of the main reasons for publishing on a Tor hidden service was to emphasise that such sites have plenty of other applications besides those they might be commonly known for, such as drug markets. “It's an intriguing idea—to swim against the current popular conceptions of anonymity and encryption,” Gehl said.

As for GMH, “I go into it hoping to highlight what Tor can be used for: which is a way of using the internet as you already do, except preserving your dignity and right not to have your private life interfered with.” “I believe communication, especially reading things on the internet, should be private by default and that that should only be interfered with in very exceptional circumstances,” he added.

At the moment, the pair are taking a break from The Torist, but future issues might be in the pipeline soon.

“We'll accept submissions all year round,” GMH said.

Friday, January 15. 2016

Note: it is not too late to wish everybody a happy '16, so, here I do! ... even so the year started in such a sad way with the disappearance of this shiny artist called David Bowie.

Maybe is it then already the right time to bring back our good old '16 resolutions, so to conjure these bad vibes? For my part, some of them were about reading... like always (or adding books on my already too big pile I can guess) and while I was wandering here and there on the Net late last December, I stumble upon this interesting initiative of curated lists of books related to design and art. Curators of books include readers such as Peter Eisenman, Tonny Dunne, Sou Fujimoto, Massimo Vignelli, John Maeda and many others (177 designers to date, 34 commentators, 73 guests, etc.).

Well... interesting line up I must say! Have a good '16 reading ...

Via Designers & Books

-----

" Designers & Books is an advocate for books as an important source of inspiration for creativity, innovation, and invention. The main way we do this is by publishing lists of books that esteemed members of the international design community identify as important, meaningful, and formative—books that have shaped their values, their worldview, and their ideas about design. This provides the direction for our focus on books about architecture, fashion, graphic design, interactive design, interior design, landscape architecture, product and industrial design, and urban design. "

Friday, September 20. 2013

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

By The Physics arXiv Blog

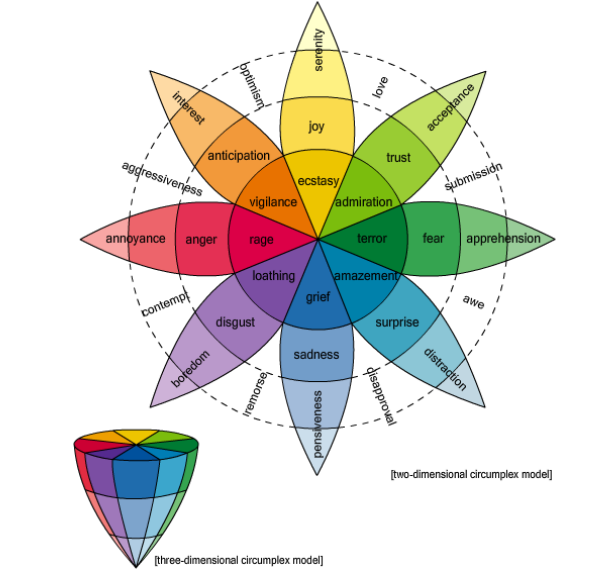

Sentiment analysis on the social web depends on how a person’s state of mind is expressed in words. Now a new database of the links between words and emotions could provide a better foundation for this kind of analysis.

One of the buzzphrases associated with the social web is sentiment analysis. This is the ability to determine a person’s opinion or state of mind by analysing the words they post on Twitter, Facebook or some other medium.

Much has been promised with this method—the ability to measure satisfaction with politicians, movies and products; the ability to better manage customer relations; the ability to create dialogue for emotion-aware games; the ability to measure the flow of emotion in novels; and so on.

The idea is to entirely automate this process—to analyse the firehose of words produced by social websites using advanced data mining techniques to gauge sentiment on a vast scale.

But all this depends on how well we understand the emotion and polarity (whether negative or positive) that people associate with each word or combinations of words.

Today, Saif Mohammad and Peter Turney at the National Research Council Canada in Ottawa unveil a huge database of words and their associated emotions and polarity, which they have assembled quickly and inexpensively using Amazon’s crowdsourcing Mechanical Turk website. They say this crowdsourcing mechanism makes it possible to increase the size and quality of the database quickly and easily.

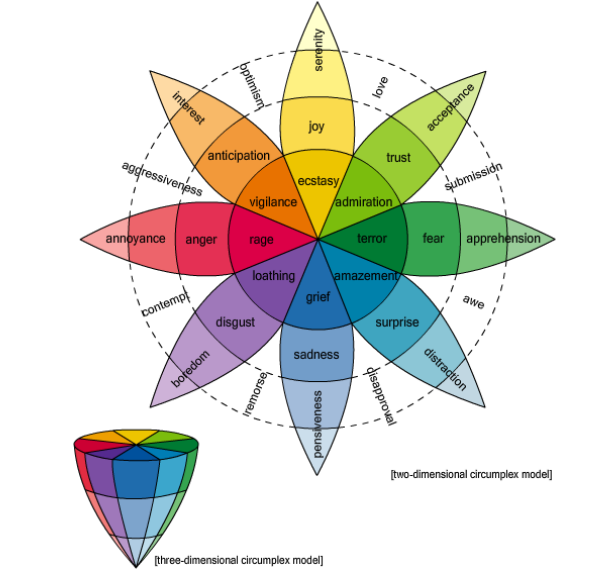

Most psychologists believe that there are essentially six basic emotions– joy, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and surprise– or at most eight if you include trust and anticipation. So the task of any word-emotion lexicon is to determine how strongly a word is associated with each of these emotions.

One way to do this is to use a small group of experts to associate emotions with a set of words. One of the most famous databases, created in the 1960s and known as the General Inquirer database, has over 11,000 words labelled with 182 different tags, including some of the emotions that psychologist now think are the most basic.

A more modern database is the WordNet Affect Lexicon, which has a few hundred words tagged in this way. This used a small group of experts to manually tag a set of seed words with the basic emotions. The size of this database was then dramatically increased by automatically associating the same emotions with all the synonyms of these words.

One of the problems with these approaches is the sheer time it takes to compile a large database so Mohammad and Turney tried a different approach.

These guys selected about 10,000 words from an existing thesaurus and the lexicons described above and then created a set of five questions to ask about each word that would reveal the emotions and polarity associated with it. That’s a total of over 50,000 questions.

They then asked these questions to over 2000 people, or Turkers, on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk website, paying 4 cents for each set of properly answered questions.

The result is a comprehensive word-emotion lexicon for over 10,000 words or two-word phrases which they call EmoLex.

One important factor in this research is the quality of the answers that crowdsourcing gives. For example, some Turkers might answer at random or even deliberately enter wrong answers.

Mohammad and Turney have tackled this by inserting test questions that they use to judge whether or not the Turker is answering well. If not, all the data from that person is ignored.

They tested the quality of their database by comparing it to earlier ones created by experts and say it compares well. “We compared a subset of our lexicon with existing gold standard data to show that the annotations obtained are indeed of high quality,” they say.

This approach has significant potential for the future. Mohammad and Turney say it should be straightforward to increase the size of the date database and at the same technique can be easily adapted to create similar lexicons in other languages. And all this can be done very cheaply—they spent $2100 on Mechanical Turk in this work.

The bottom line is that sentiment analysis can only ever be as good as the database on which it relies. With EmoLex, analysts have a new tool for their box of tricks.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1308.6297: Crowdsourcing a Word-Emotion Association Lexicon.

Thursday, October 04. 2012

Tuesday, September 04. 2012

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

Researchers at Harvard encode information in DNA at a density on par with any other experimental storage method.

DNA can be used to store information at a density about a million times greater than your hard drive, report researchers in Science today. George Church of Harvard Medical School and colleagues report that they have written an entire book in DNA, a feat that highlights the recent advances in DNA synthesis and sequencing.

The team encoded a draft HTML version of a book co-written by Church called Regenesis: How Synthetic Biology Will Reinvent Nature and Ourselves. In addition to the text, the biological bits included the information for modern formatting, images and Javascript, to show that “DNA (like other digital media) can encode executable directives for digital machines,” they write.

To do this, the authors converted the computational language of 0's and 1's into the language of DNA--the nucleotides typically represented by A's, T's G's and C's; the A’s and C’s took the place of 0's and T’s and G’s of 1's. They then used off-the-shelf DNA synthesizers to make 54,898 pieces of DNA, each 159 nucleotides long, to encode the book, which could then be decoded with DNA sequencing.

This is not the first time non-biological information has been stored in DNA, but Church's demonstration goes far beyond the amount of information stored in previous efforts. For example, in 2009, researchers encoded 1688 bits of text, music and imagery in DNA and in 2010, Craig Venter and colleagues encoded a watermarked, synthetic genome worth 7920 bits.

DNA synthesis and sequencing is still too slow and costly to be practical for most data storage, but the authors suggest DNA’s long-lived nature could make it a suitable medium for archival storage.

Erik Winfree, who studies DNA-based computation at Caltech and was a 1999 TR35 winner, hopes the study will stimulate a serious discussion about what roles DNA can play in information science and technology.

“The most remarkable thing about DNA is its information density, which is roughly one bit per cubic nanometer,” he writes in an email.

“Technology changes things, and many old ideas for DNA information storage and information processing deserve to be revisited now -- especially since DNA synthesis and sequencing technology will continue their remarkable advance.”

Personal comment:

Where the living binds to the machine / to computation and where information seems to be the key ingredient. Somehow what Wiener and Shannon told us half a century ago.

Monday, March 26. 2012

-----

de Léopold Lambert

Excerpt from Le Processus by Marc-Antoine Mathieu (Delcourt 1993)

Following the three last articles in which I was preparing my reference texts in addition of those that I have been already writing in the past, this following article is an attempt to reconstitute the small presentation I was kindly invited to give by Carla Leitão for her seminar about libraries and archives at Pratt Institute. This talk was trying to elaborate a small theory of the book as a subversive artifact based on six literary authors that have in common a dramatization of their own medium, the book, within their books. The predicate of this essay lies in the fact that books are indeed subversive -and therefore suppressed by authoritarian power- as they reveal the existence of other worlds.

REFERENCE TEXTS/DRAWINGS ON THE FUNAMBULIST FOR CHAPTER 1

In his series Julius Corentin Acquefacques, prisonnier des rêves, Marc-Antoine Mathieu continuously explores and questions graphic novel as the medium he uses for his narratives to exist, and therefore to acquire a certain autonomy as soon as they have been created. In reusing the constructive elements of drawings within the narrative (preparatory sketches, vanishing points, framing bars, anamorphoses etc.) he creates several layers of universes that include our own, and therefore makes us wonder if our reality couldn’t be the fiction of a higher degree of reality.

It is not innocent that he uses the terminology of the dream to bases his stories as dreams constitute the daily experience we make of another world within the world. The nightmare here, is based on the impossibility for the main character, Julius Corentin Acquefacques to distinguish what is dream, what is his reality, what is the reality of those other worlds he can see for short instants and eventually what is the reality of his creator, the author himself.

In The Trial written by Franz Kafka and published in 1929, the book as an artifact is not literally present. However, the existence of other worlds within the narrative can be found in the fact that the version we know is the one assembled by Kafka’s best friend, Max Brod who re-assembled the chapters of the unachieved book according to his own interpretation and on the contrary of his friend’s wishes who wanted it to be burnt. Brod, in a research for rationality starts the narrative by the scene in which K., the protagonist, learns that he will be judged for something he ignores, continues it by K.’s experience of the administrative labyrinth and eventually finishes it by K.’s execution. In Towards a Minor Literature, Felix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze criticize this order, cannot seem to accept that such chapter about K.’s death has been written by Kafka and eventually consider that this event is nothing more than an additional part of the character’s delirium or dream within the story. As I have been writing before in an essay entitled The Kafkian Immanent Labyrinth as a Post-Mortem Dream, my own interpretation consists in starting with this ‘last’ chapter in which K. is executed, thus attributing the following delirium to the visions that K. experiences before dying. In other words, K. never really dies for himself even though he dies in the point of view of others, of course (to read more about this topic read also my review of Gaspard Noe’s Enter the Void). His perception of time exponentially decelerates tending more and more towards the exact moment of his death without ever reaching it: this is the Kafkian nightmare.

The fact that one can counts three (and probably so many more) ways of assembling the ten chapters written by Kafka make the book itself a labyrinth allowing the existence of several parallel worlds which all share the same composing elements but presents different essences of meaning.

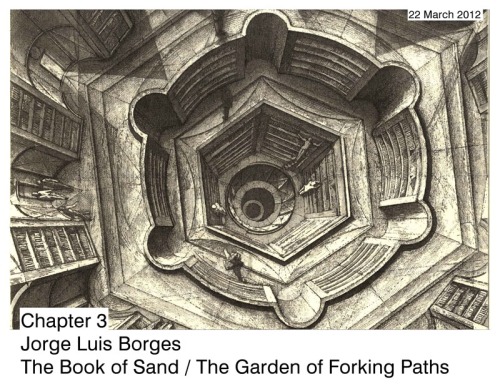

illustration by Erick Desmazieres

Jorge Luis Borges, whose filiation with Kafka is not to be demonstrated, is also well known for his quasi-Leibnizian (see previous article) invention of an infinity of parallel worlds through books. The Library of Babel (see previous post) is the most famous example as it introduces an infinite library containing every unique books that can be written in 410 pages with 25 symbols. At the end of this short story, Borges precises that this library could be in fact, contained in a single book which will be introduced later on in The Book of Sand (see the recent post about it): a book with an infinity of pages.

What is to be found in infinity seems to be indicated in the story The Secret Miracle (1943) in the following excerpt that could easily be used to essentialize Borges’ work and life:

Toward dawn he dreamed that he had concealed himself in one of the naves of the Clementine Library. A librarian wearing dark glasses asked him: “What are you looking for?” Hladik answered: “I am looking for God.” The librarian said to him: “God is in one of the letters on one of the pages of one of the four hundred thousand volumes of the Clementine. My fathers and the fathers of my fathers have searched for this letter; I have grown blind seeking it.”

in Labyrinths. New York: New Directions Book, 1962.

Many Borges’ readers will indeed know that himself lost his sight few decades after he wrote this story. What was this God that he was looking for in the many book of Buenos Aires’ National Library? Which kind of Kaballah did he create to find an esoteric meaning in the mathematics of the profane scriptures? Maybe did he have a glance to this infinity that he has been chanting for many years and became blind as a price to pay for it.

It is in fact, one thing to comprehend the infinity of contingencies that Borges presents, but it is another one to fathom it fully. Such transcendental understanding could indeed correspond to an encounter with what deserve to be called God. Borges gives us the chance, one more time, to experience such encounter through his story The Garden of Forking Paths (1941) which dramatizes a book in which the infinite combination of worlds constituted by a given sum of events since the dawn of times exists in parallel of each other:

“Here is Ts’ui Pên’s labyrinth,” he said, indicating a tall lacquered desk.

“An ivory labyrinth!” I exclaimed. “A minimum labyrinth.”

“A labyrinth of symbols,” he corrected. “An invisible labyrinth of time. To me, a barbarous Englishman, has been entrusted the revelation of this diaphanous mystery. After more than a hundred years, the details are irretrievable; but it is not hard to conjecture what happened. Ts’ui Pe must have said once: I am withdrawing to write a book. And another time: I am withdrawing to construct a labyrinth. Every one imagined two works; to no one did it occur that the book and the maze were one and the same thing. The Pavilion of the Limpid Solitude stood in the center of a garden that was perhaps intricate; that circumstance could have suggested to the heirs a physical labyrinth. Ts’ui Pên died; no one in the vast territories that were his came upon the labyrinth; the confusion of the novel suggested to me that it was the maze. Two circumstances gave me the correct solution of the problem. One: the curious legend that Ts’ui Pên had planned to create a labyrinth which would be strictly infinite. The other: a fragment of a letter I discovered.”

Albert rose. He turned his back on me for a moment; he opened a drawer of the black and gold desk. He faced me and in his hands he held a sheet of paper that had once been crimson, but was now pink and tenuous and cross-sectioned. The fame of Ts’ui Pên as a calligrapher had been justly won. I read, uncomprehendingly and with fervor, these words written with a minute brush by a man of my blood: I leave to the various futures (not to all) my garden of forking paths. Wordlessly, I returned the sheet.

in Labyrinths. New York: New Directions Book, 1962.

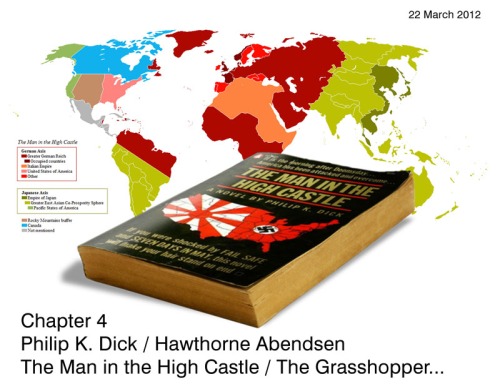

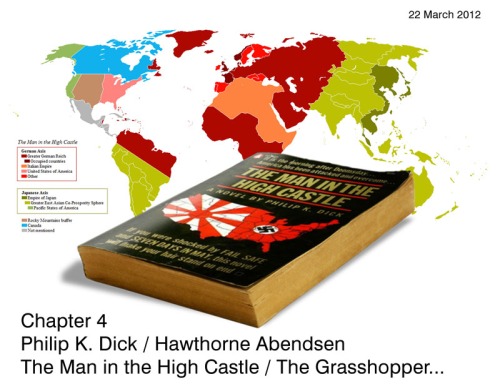

In 1962, Philip K. Dick writes a novel entitled The Man in the High Castle (see previous article) which dramatizes an uchronia for which Roosevelt died before ending his first mandate of President of the USA, replaced by an isolationist President who refuses to engage his county in the second World War. It results from this choice that the Nazis conquest Europe while the Japanese army colonizes East Asia (including Siberia) and eventually both combine their forces to invade the USA. Dick’s plot thus occurs in United States under nippo-nazi domination in which it is said to exist a book, The Grasshopper Lies Heavy written by a certain Hawthorne Abendsen who would describe in it a world in which the Allies won the over against the Axis. The book is, of course, forbidden as it allows the depiction of another reality than the one which is imposed by colonial empires:

At the bookcase she knelt. ‘Did you read this?’ she asked, taking a book out. Nearsightedly he peered. Lurid cover. Novel. ‘No,’ he said. ‘My wife got that. She reads a lot.’

‘You should read it.’

Still feeling disappointed, he grabbed the book, glanced at it. The Grasshopper Lies Heavy. ‘Isn’t this one of those banned-in-Boston books?’ he said.

‘Banned through the United States. And in Europe, of course.’ She had gone to the hall door and stood there now, waiting.

‘I’ve heard of this Hawthorne Abendsen.’ But actually he had not. All he could recall about the book was — what? That it was very popular right now. Another fad. Another mass craze. He bent down and stuck it back in the shelf. ‘I don’t have time to read popular fiction. I’m too busy with work.’ Secretaries, he thought acidly, read that junk, at home alone in bed at night. It stimulates them. Instead of the real thing. Which they’re afraid of. But of course really crave.

The Man in the High Castle. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962.

The ban of books depicted in Dick’s uchronia brings us to worlds in which books have been definitely suppressed from society. In the well known 1984, written in 1949 by Georges Orwell, the only remaining book is the dictionary of the Newspeak which, editions by editions becomes thinner and thinner as the language is subjected by a strict progressive purge. Language, indeed, allows the formulation of other worlds which can be punished as thoughtcrimes. The Book is therefore not destroyed literally but its principal material is voluntarily put in scarcity.

‘The Eleventh Edition is the definitive edition,’ he said. ‘We’re getting the language into its final shape — the shape it’s going to have when nobody speaks anything else. When we’ve finished with it, people like you will have to learn it all over again. You think, I dare say, that our chief job is inventing new words. But not a bit of it! We’re destroying words — scores of them, hundreds of them, every day. We’re cutting the language down to the bone. The Eleventh Edition won’t contain a single word that will become obsolete before the year 2050.’

He bit hungrily into his bread and swallowed a couple of mouthfuls, then continued speaking, with a sort of pedant’s passion. His thin dark face had become animated, his eyes had lost their mocking expression and grown almost dreamy.

‘It’s a beautiful thing, the destruction of words. Of course the great wastage is in the verbs and adjectives, but there are hundreds of nouns that can be got rid of as well. It isn’t only the synonyms; there are also the antonyms. After all, what justification is there for a word which is simply the opposite of some other word? A word contains its opposite in itself. Take “good”, for instance. If you have a word like “good”, what need is there for a word like “bad”? “Ungood” will do just as well — better, because it’s an exact opposite, which the other is not. Or again, if you want a stronger version of “good”, what sense is there in having a whole string of vague useless words like “excellent” and “splendid” and all the rest of them? “Plusgood” covers the meaning, or “doubleplusgood” if you want something stronger still. Of course we use those forms already. but in the final version of Newspeak there’ll be nothing else. In the end the whole notion of goodness and badness will be covered by only six words — in reality, only one word. Don’t you see the beauty of that, Winston? It was B.B.’s idea originally, of course,’ he added as an afterthought.

1984. New York : Signet Classics, 1949

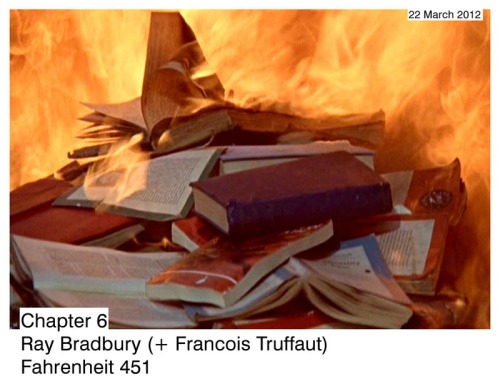

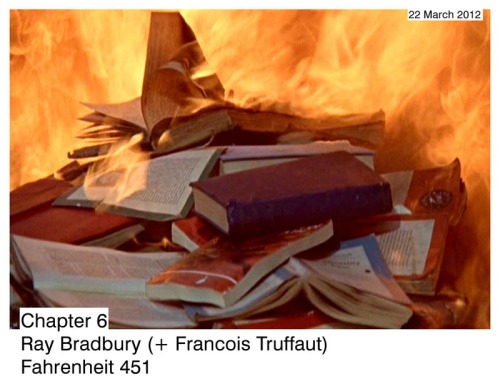

The quintessential narrative dramatizing the destruction of books is of course Fahrenheit 451 (see the recent article about it) written by Ray Bradbury in 1953. In this story, firemen are not people in charge of fighting against fire, but on the contrary, those in charge of inflaming books that have been banned as principal element of discord and inequality within society. Fahrenheit 451 (233 degrees Celsius) is indeed the temperature for which paper burns. Books are thus the object that allows the various human writings to remain archived for virtually eternity but which allow carry with them, their own fragility as their main material, paper, is vulnerable to the elements and fire in particular. Francois Truffaut, who released an excellent film adaptation of Bradbury’s novel in 1966, by showing a copy of Mein Kampf in his movie, did not miss to point out that a resistance movement that would undertake to save the books from fire could not possibly judge which books deserved to be kept and which one could be let to the institutional purge.

In the theater play Almansor that he wrote in 1820, Heinrich Heine makes the following tragic prophecy: Where we burn books, we will end up burning men. On May 10th 1933, the Nazis who recently reached the head of the executive and legislative power in Germany will burn thousands of books including Heine’s, which do not fit within the spirit of the new antisemitic/anti-communist politics they are willing to undertake. About a decade later, they will industrially kill eleven millions people (including six millions Jews) in what remains as the darkest moment of mankind’s history: the Holocaust.

Among the books burned in 1933, one could find the ones written by Marx, Freud, Brecht, Benjamin, Einstein, Kafka but also one of the father of science fiction, HG Wells. This last example illustrates well the will of the third Reich to annihilate any vision of the future that was not compliant with the one elaborated by the Nazis.

In latin, book burning ceremonies are called autodafé from Portuguese Acto da Fé (literally act of faith). Autodafé were common during the Spanish and Portuguese inquisition during the medieval era. Indeed, books listed in the Catholic Index (the list of books forbidden by the Church) and heretics were burned indistinctly in vast rituals of authoritarian religion. In 1933, this act of faith had been elaborated by Joseph Goebbels, minister of propaganda of the Reich and accomplished with great enthusiasm by hordes of students who collected and confiscated the books that have been listed as subversive. An important element in the principal autodafé of May 10th 1933 in Berlin was that the rain was preventing the flames to burn the book in such a way that firemen had to pour gasoline on the aggregation of books to set them ablaze. This significant ‘detail’ had probably a great influence on Bradbury in the elaboration of his narrative.

The books are therefore agents of infection in the point of view of an authoritarian ideological power. Their authors place in them the germs of subversion that are then spread to whoever read them. Knowledge is power as Foucault was insisting, imagination is, in fact, power to the same extent. The virtual access to other worlds via books is the possibility of a resistance in this given reality. For that, books have to be salvaged at any price. They constitute the archives of a civilization as much as they are the active agents of vitalization of a society that accepts the multiplicity of their narratives.

Tuesday, March 06. 2012

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

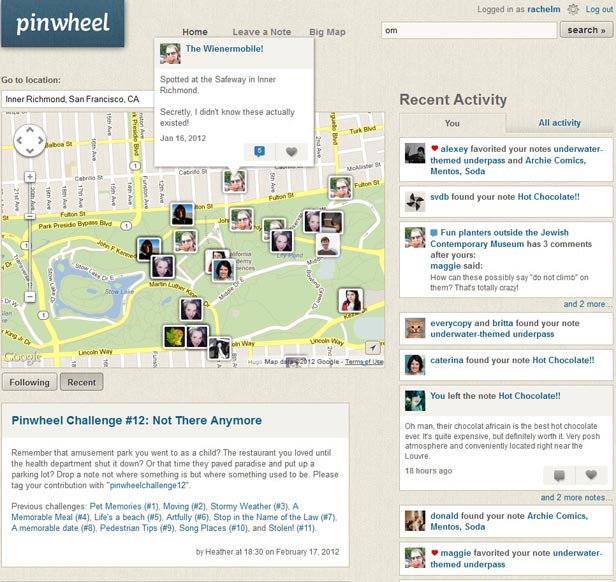

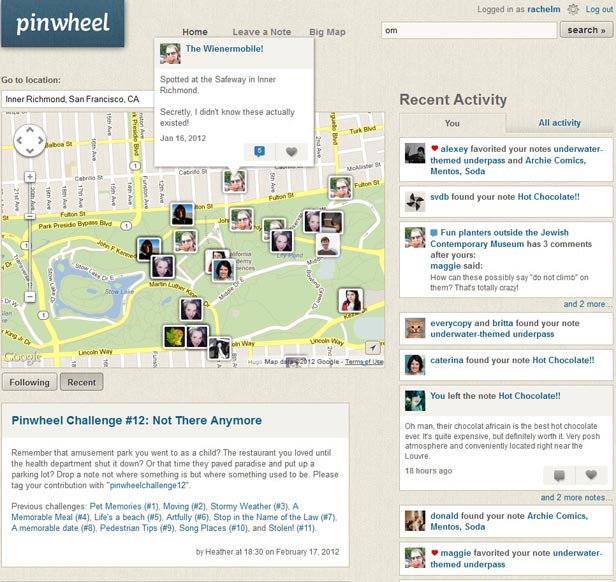

Pinwheel, a new site created by Flickr cofounder Caterina Fake, lets users post virtual notes anywhere.

By Rachel Metz

You've probably left plenty of notes for people in the past—on a kitchen counter, slipped through the slots of a locker, or even scrawled on a bathroom wall. But what if you could leave notes anywhere in the world for anyone to discover, and find ones posted by others?

That's the idea behind Pinwheel, the latest startup from Flickr cofounder Caterina Fake. Though the social site only recently emerged in a private beta testing phase, it's gaining buzz for its simple premise: letting people annotate a map with notes on any topic that can be shared with others.

Fake, a fan of the GPS treasure-hunting activity known as geocaching, says Pinwheel merges several ideas and inspirations. She first began toying with the idea of leaving virtual notes for others to find back in 1999, but the technology wasn't there to support it. And after cofounding Flickr in 2004, she was inspired by users of that site who would annotate satellite maps of their hometowns with notes about various locations. Now, as smart phones have become incredibly popular and location-based apps like Foursquare have blossomed, Fake is confident that the timing is right for Pinwheel, too.

The site's main page—which you need an invitation to see—shows a stream of recently posted notes, and users can browse a map there to check out public notes, leave notes, or search for notes or users.

Navigating the main map is like exploring a visual mash-up of a travel and restaurant guide peppered with memories of first kisses and apartments, event notices, historical facts, and more. There are burger and sushi recommendations, notes about good places to watch the sun set, and tags marking a long-gone movie theater and candy store. One user has been using Pinwheel to log crimes—including the kidnapping and return of Banana Sam, a squirrel monkey belonging to the San Francisco Zoo (now safely returned)—while another is recording historic facts in various cities.

"To me, when you are creating social software, the most exciting part of it is when people start using your tools for things you hadn't expected," Fake says.

At the moment, there is no Pinwheel smart-phone app to help you leave notes on the fly, so users simply log on to the Pinwheel website to do so (there is a mobile site, and Fake says an iPhone app is forthcoming).

Notes can be set as visible to any site user, or just to certain people that you've chosen to follow on the site. Currently, notes can only include text or photos, but Fake says this could eventually expand to audio or video clips as well.

As of early last week, only about 1,000 people were using the site, but Fake says tens of thousands of people have requested invites, and Pinwheel is now sending those out.

Jason Hong, an associate professor at Carnegie Mellon University who studies mobile social technology, sees interesting possibilities for Pinwheel as well as several challenges, including how to gain a critical mass of users and content given the popularity of existing tools like Yelp, Foursquare, and Twitter. "People are still struggling with what, exactly, they're using this for," he says.

Regardless, investors are confident Pinwheel is on to something. The site recently raised $7.5 million in a Series A funding round led by Redpoint Ventures, which added to the $2 million in funding Pinwheel had previously raised. Fake's past success helped, too—photo-sharing site Flickr sold to Yahoo in 2005 and the recommendation engine Hunch, which she also cofounded, sold to eBay in 2011, both for undisclosed amounts.

And, unlike many other Silicon Valley startups, Pinwheel does have a business model: it plans to make money by allowing sponsored notes, something that it's already testing out.

Redpoint partner Geoff Yang says he liked the notion of bringing an offline activity like leaving notes onto the Web, and he sees the site as the combination of social, mobile, and local trends. "I thought the idea was really interesting—the notion that Pinwheel, in many respects, makes places come alive," he says.

Copyright Technology Review 2012.

Personal comment:

An idea (and technology) of annotating the physical world with digital (geolocalized) notes that comes again.

Tuesday, January 10. 2012

Via Pruned

-----

In case you need reminding, Bracket 3 is looking for critical articles and unpublished design projects that explore “architecture, infrastructure and technology [operating] in conditions of imbalance, negotiate tipping points and test limit states. In such conditions, the status quo is no longer possible; systems must extend performance and accommodate unpredictability. As new protocols emerge, new opportunities present themselves. Bracket [at Extremes] seeks innovative contributions interrogating extreme processes (technologies, operations) and extreme contexts (cultural, climatic). What is the breaking point of architecture at extremes?”

The deadline is 20 February 2012.

Also be on the lookout for Bracket [goes soft], scheduled to be available this month from Actar. Some of the projects in this second almanac sound like they also belong in the new one.

Personal comment:

Thanks for the reminder!

Friday, January 07. 2011

Via ArchDaily

-----

by Alison Furuto

Moderated by Joseph Grima (Domus), all are invited to the free Critical Futures event starting at 6:30pm on January 13th, which will focus on a debate on the future of architecture criticism followed by complimentary drinks and further discussion after the talk. Participants include Charles Holland (author, Fantastic Journal), Peter Kelly (Blueprint), Kieran Long (architecture critic, Evening Standard), Geoff Manaugh (author, BLDGBLOG), and Beatrice Galilee (writer, curator, DomusWeb, The Gopher Hole). The event is located at The Gopher Hole, 350-354 Old Street, London, EC1V 9NQ. More event description after the break.

Over the past decade, epochal transformations have profoundly reshaped the context within which architecture is conceived and debated. The Internet has made images and information free and instantly ubiquitous; magazines, once the undisputed platforms for the criticism of architecture and design, have been challenged to redefine their purpose and economic model in the light of dwindling readerships; blogs have given a global audience, potentially of millions, to anyone with an Internet connection. In all of this, architecture criticism in the traditional sense appears to have all but vanished – not only from the Internet but from magazines themselves. As Peter Kelly, editor of Blueprint, wrote in a recent editorial, “As traditional publishing media and institutions become less influential, one wonders where architects can go to find informed, intelligent criticism of their work”.

Does, as author of BLDGBLOG Geoff Manaugh proposes, the designer of the videogame Grand Theft Auto have more influence as an architect than David Chipperfield? Is criticism in the traditional sense still relevant or useful? If the role of the print publication in contemporary production irreversibly declines, what is its future role? What forces will shape architectural production in a post-critical environment? Is, as Kelly writes, a more realistic and rigorous approach to architectural criticism online urgently needed?

As the first in a three-part series of debates on the future of architecture criticism organized by Domus in London, Milan and New York to celebrate the launch of its new website, this discussion will bring together writers, editors, bloggers and theorists active in the field today to address these and other questions.

The event will be hosted by The Gopher Hole, an exhibition and events space in Shoreditch, London.

|