Sticky Postings

All 242 fabric | rblg updated tags | #fabric|ch #wandering #reading

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Tuesday, February 27. 2024

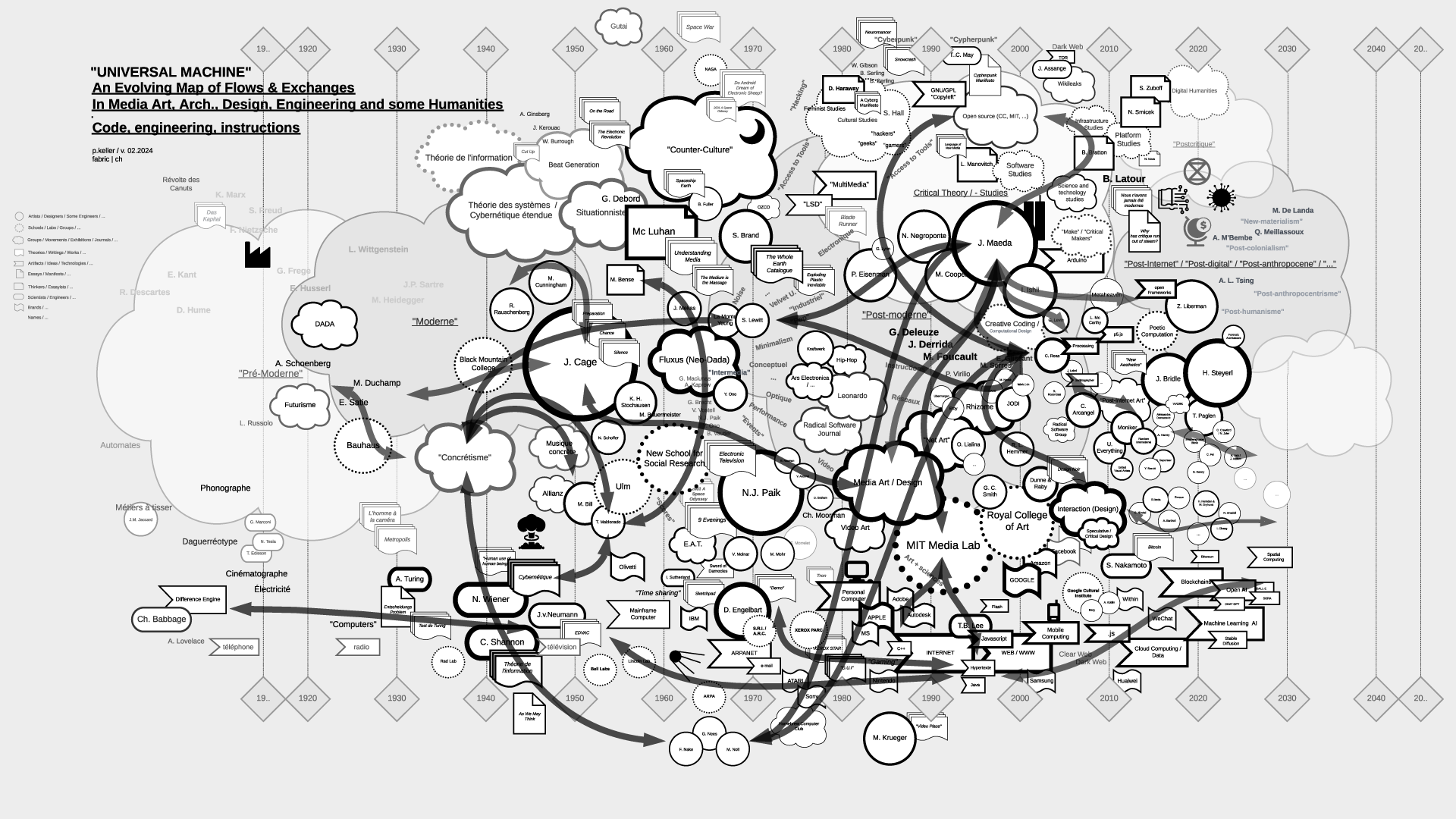

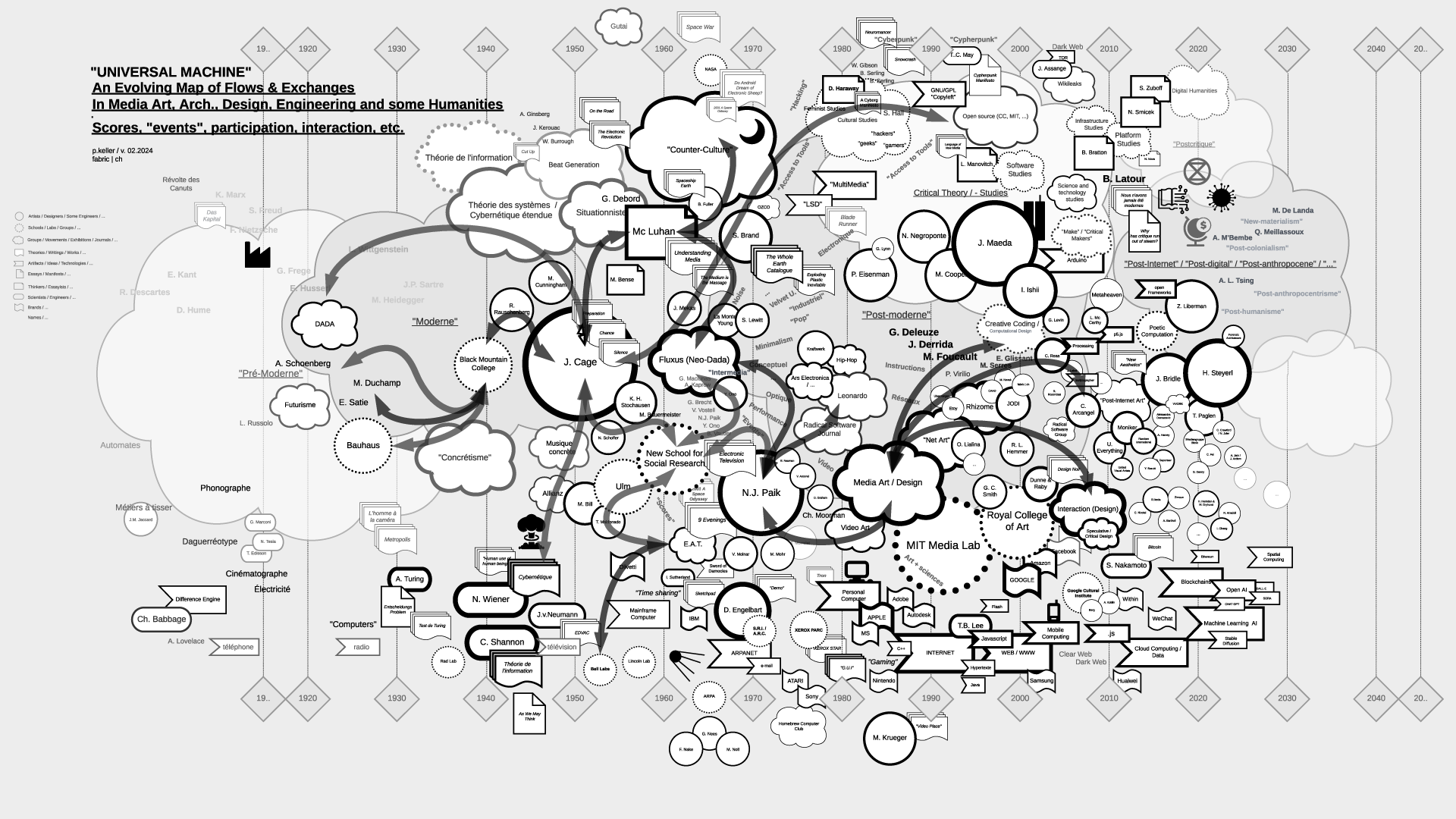

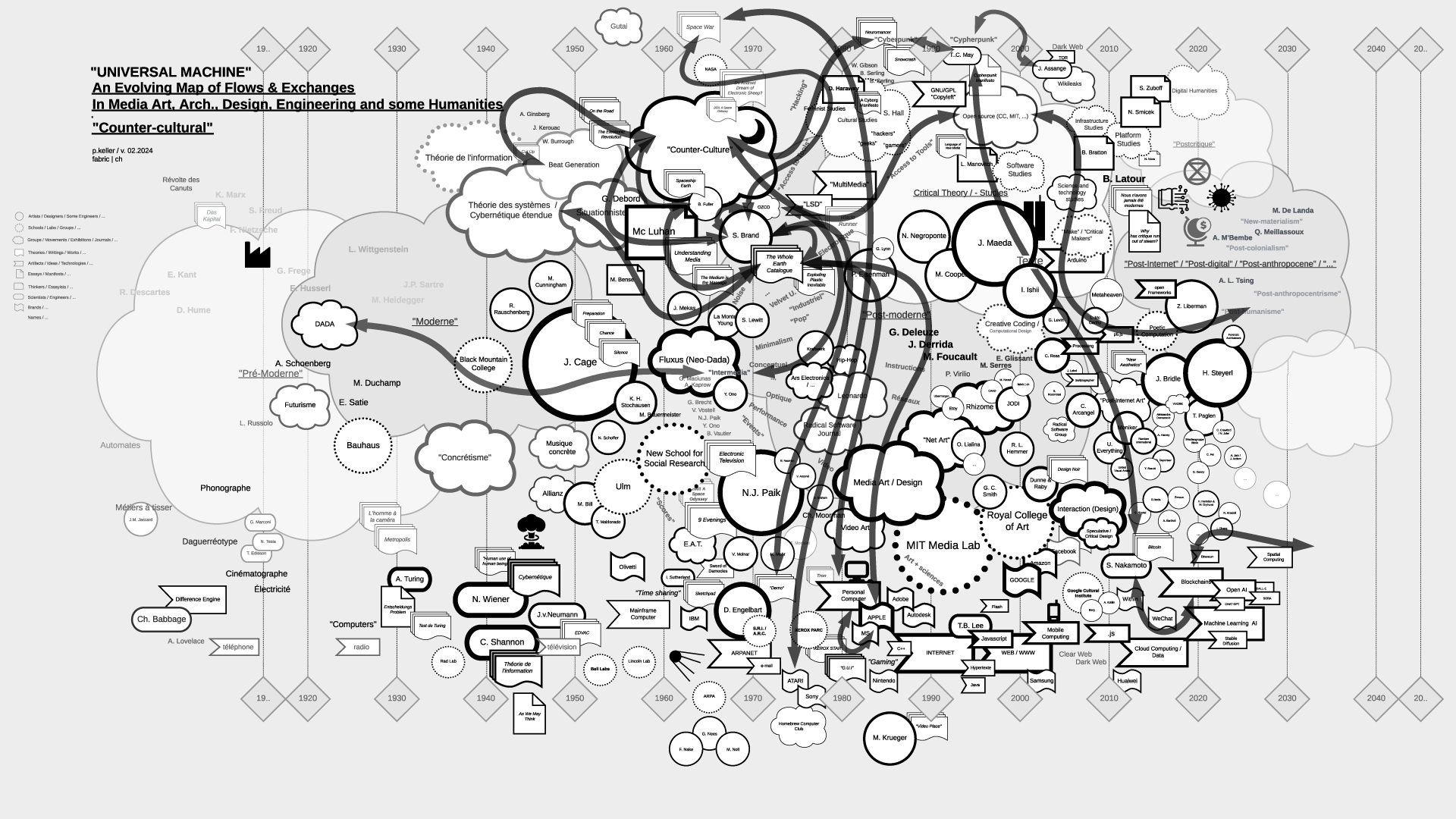

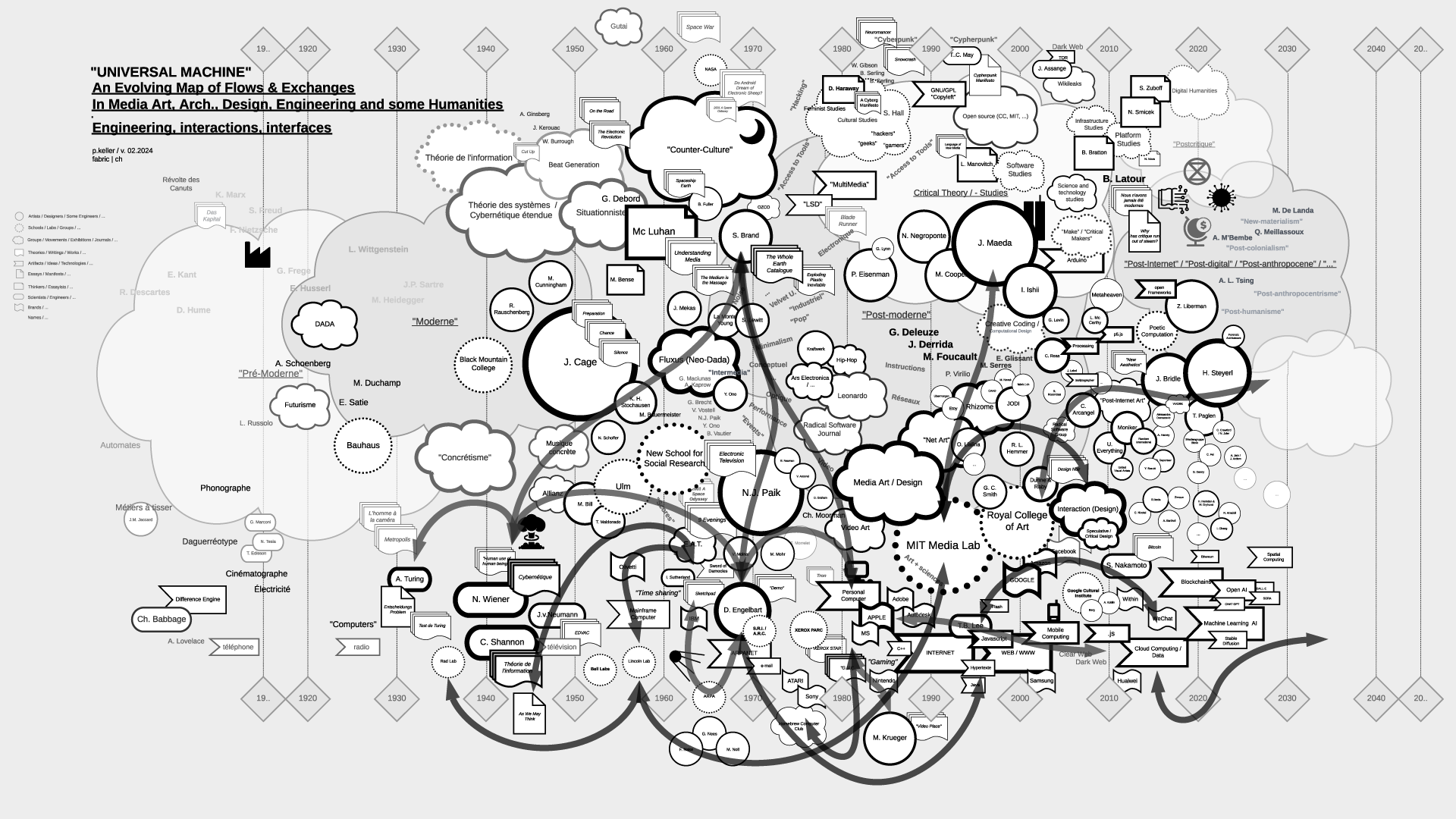

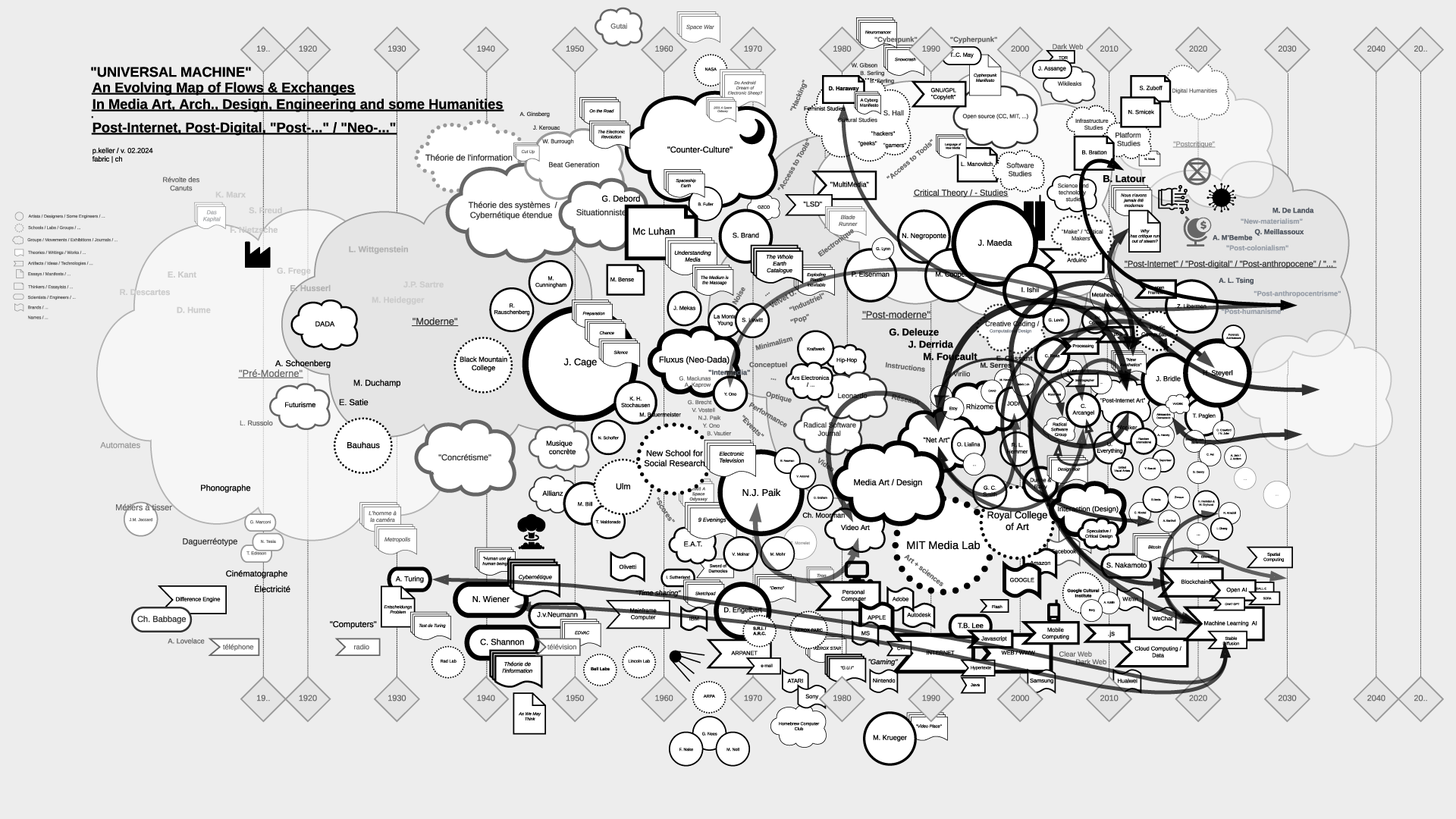

"Universal Machine": historical graphs on the relations and fluxes between art, architecture, design, and technology (19.. - 20..) | #art&sciences #history #graphs

Note (03.2024): The contents of the files (maps) have been updated as of 02.2024.

-

Note (07.2021): As part of my teaching at ECAL / University of Art and Design Lausanne (HES-SO), I've delved into the historical ties between art and science. This ongoing exploration focuses on the connection between creative processes in art, architecture, and design, and the information sciences, particularly the computer, also known as the "Universal Machine" as coined by A. Turing. This informs the title of the graphs below and this post.

Through my work at fabric | ch, and previously as an assistant at EPFL followed by a professorship at ECAL, to experience first hand some of these massive transformations in society and culture.

Thus, in my theory courses, I've aimed to create "maps" that aid in comprehending, visualizing, and elucidating the flux and timelines of interactions among individuals, artifacts, and disciplines. These maps, imperfect and constrained by size, are continuously evolving and open to interpretation beyond my own. I regularly update them as part of the process.

Yet, in the absence of a comprehensive written, visual, or sensitive history of these techno-cultural phenomena as a whole, these maps serve as valuable approximation tools for grasping the flows and exchanges that either unite or divide them. They offer a starting point for constructing personal knowledge and delving deeper into these subjects.

This is precisely why, despite their inherent fuzziness - or perhaps because of it - I choose to share them on this blog (fabric | rblg), in an informal manner. It's an invitation for other artists, designers, researchers, teachers, students, and so forth, to begin building upon them, to depict different flows, to develop pre-existing or subsequent ideas, or even more intriguingly, to diverge from them. If such advancements occur, I'm keen on featuring them on this platform. Feel free to reach out for suggestions, comments, or to share new developments.

...

It's worth mentioning that the maps are structured horizontally along a linear timeline, spanning from the late 18th century to the mid-21st century, predominantly focusing on the industrial period. Vertically, they are organized around disciplines, with the bottom representing engineering, the middle encompassing art and design, and the top relating to humanities, social events, or movements.

Certainly, one might question this linear timeline, echoing the sentiments of writer B. Latour. What about considering a spiral timeline, for instance? Such a representation would still depict both the past and the future, while also illustrating the historical proximities of topics, connecting past centuries and subjects with our contemporary context in a circular manner. However, for the time being, and while recognizing its limitations, I adhere to the simplicity of the linear approach.

Countless narratives can emerge as inherent properties of the graphs, underscoring that they are not their origins but rather products thereof.

...

The selection of topics (code, scores-instructions, countercultural, network-related, interaction, "post-...") currently aligns with the themes of my teaching but is subject to expansion, possibly toward an underlying layer revealing the material conditions that underpinned and facilitated the entire process.

In any case, this could serve as a fruitful starting point for some further readings or perhaps a new "Where's Waldo/Wally" kind of game!

Via fabric | ch

-----

By Patrick Keller

Rem.: By clicking on the thumbnails below you'll get access to HD versions.

"Universal Machine", main map (late 18th to mid 21st centuries):

Flows in the map > "Code":

Flows in the map > "Scores, Partitions, ...":

Flows in the map > "Countercultural, Subcultural, ...":

Flows in the map > "Network Related":

Flows in the map > "Interaction":

Flows in the map > "Post-Internet/Digital, "Post -..." , "Neo -...", ML/AI":

...

To be continued (& completed) ...

Thursday, August 03. 2023

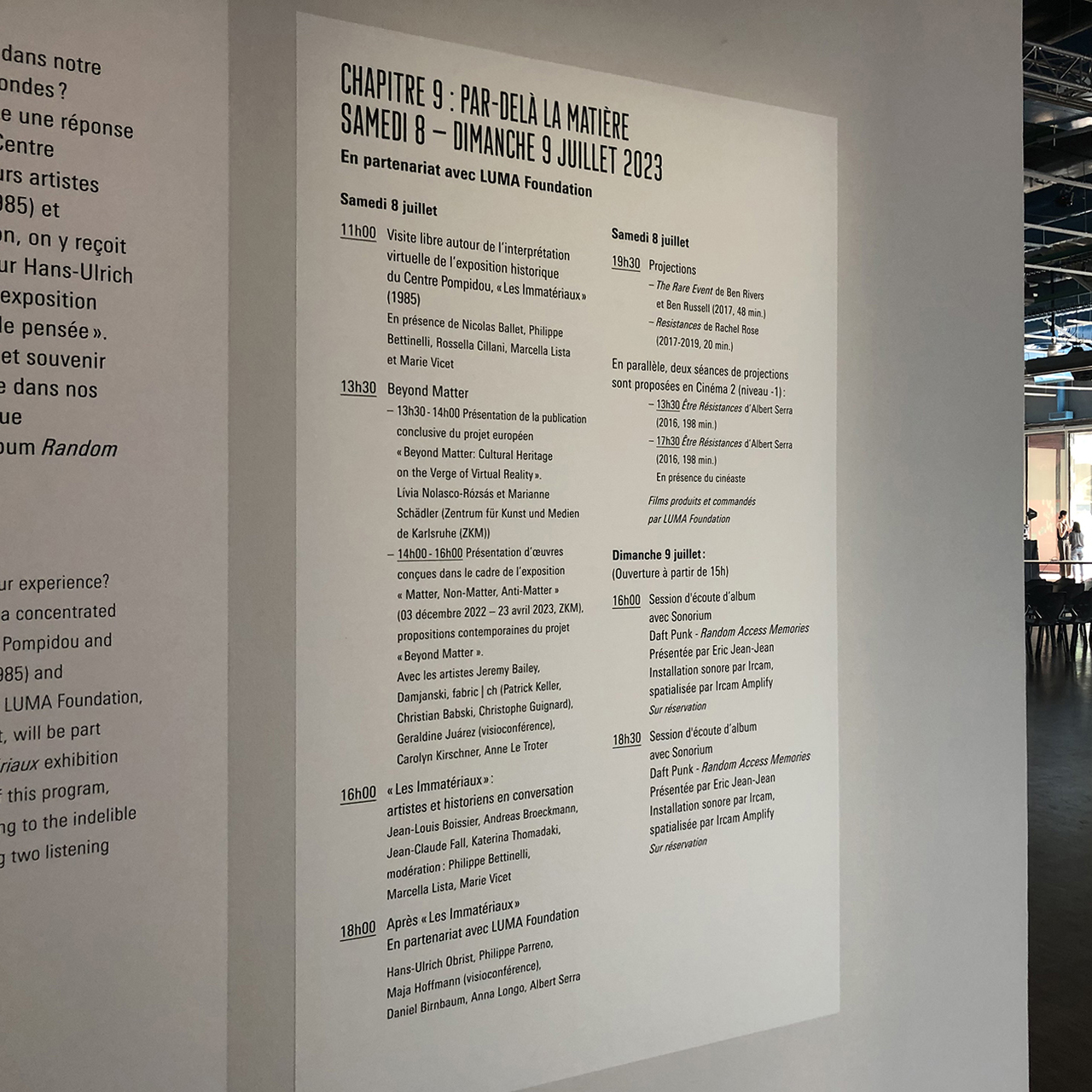

Moviment exhibition at the Centre Pompidou – fabric | ch during Chapter "Par-delà la matière" | #matter #non-matter #automated #exhibition #fabricch

Note: Early last July, fabric | ch took part in the Moviment exhibition-festival at Centre Pompidou, in Paris.

Organized in 10 chapters (Red thread; The bedroom, the house, the city; In the spotlight; Aloud, Here and elsewhere, Other-worldly; Of gesture and time; To the max; Beyond matter; The grand finale!), this was the occasion – following the words of the curators – to "reactivate the essence of the Centre Pompidou ideals: to assemble all the different ways of encountering creativity, understanding it, participating in it; to be a monument in motion, a "moviment."

It was truly a success, with outstanding guests and a very interesting hybrid museum format, somewhere in-between exhibition and performance, talks and workshops.

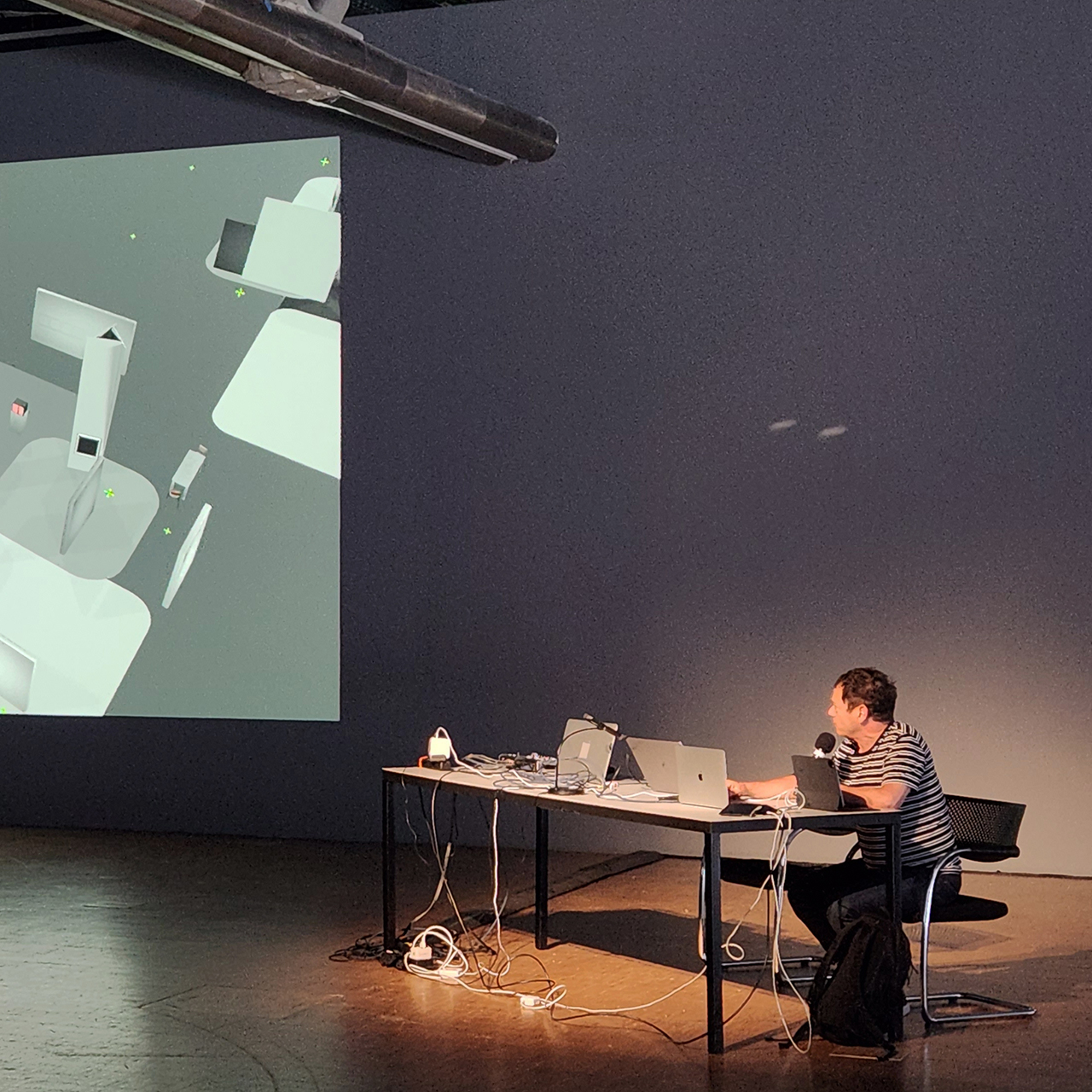

In this context and during "Chapitre 9: Par-delà la matière" curated by Marcella Lista & Philippe Bettinelli, fabric | ch presented recent works about digital exhibitions.

-----

By fabric | ch

![]()

A few pictures from Moviment / Chapter 9:

(with fabric | ch, M. Lista & Les Immatériaux, M. Klonaris & K. Thomadaki, H.U. Obrist – "Résistances" project with LUMA Foundation and P. Parreno, J.-L. Boissier - Electra / Pictures by C. Babski & H. Veronese)

Via Centre Pompidou

-----

Beyond Matter / Par-delà la matière

Moviment, chapter 9

Sat 8 – Sun 9 July 2023

Combining technology and memory, the penultimate chapter of Moviment looks back at two major cultural events in the world of art and music, and the ways in which they can be perpetuated, revived or experienced beyond their materiality and topicality.

In partnership with LUMA Foundation

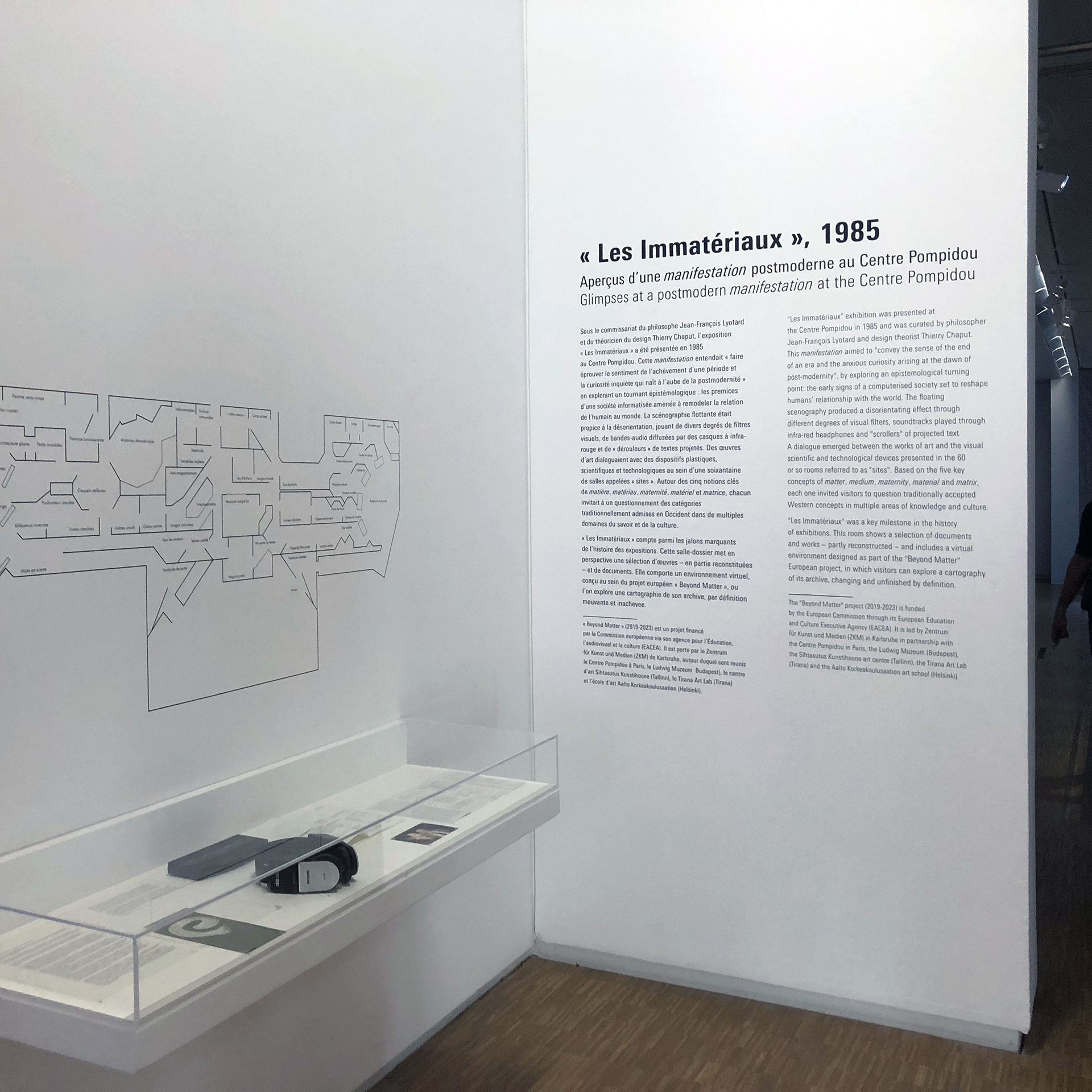

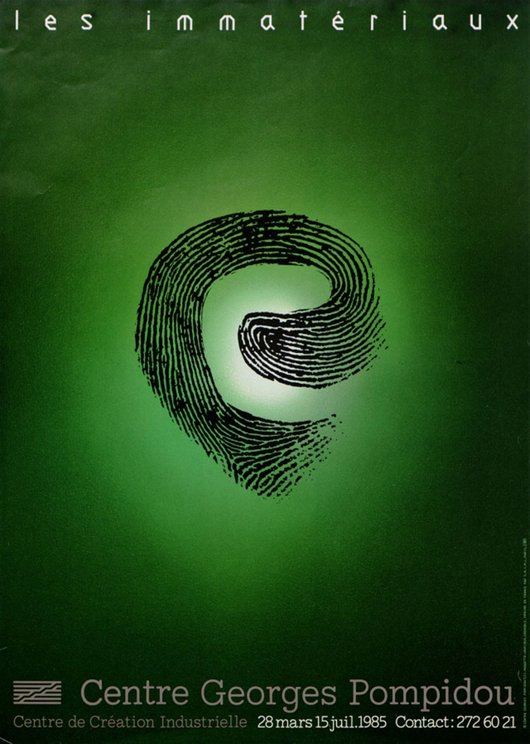

Affiche de l’exposition "Les Immatériaux", 1985 – © Centre Pompidou. Conception graphique : Grafibus.

Retour sur « Les Immatériaux »

Arts plastiques, Nouveaux médias Exposition, rencontres

Organisé par les commissaires Jean-François Lyotard et Thierry Chaput en 1985, « Les Immatériaux » était un essai aux fondements philosophiques adoptant l’exposition comme média ou interface. En faisant dialoguer œuvres d’art, technologies et documents scientifiques, les commissaires interrogeaient la condition humaine à l’ère des nouvelles technologies, dans différents domaines de la vie physique et psychique. La scénographie, particulièrement novatrice, privilégiait la désorientation, la stimulation de tous les sens et l’interactivité. Les visiteurs, dont le parcours n’était pas contraint mais « induit » par des écrans suspendus à l’opacité variable, étaient munis d’un casque diffusant une bande sonore variant au gré de leur déambulation dans la soixantaine de sites et les vingt-six zones audio de l’exposition.

Cette exposition historique a récemment fait l’objet d’une reconstitution virtuelle dans le cadre du projet de recherche « Beyond Matter ».

Exposition en continu, samedi 8 juillet 2023

« Beyond Matter »

Financé par la Commission européenne, le projet de recherche « Beyond Matter: Cultural Heritage on the Verge of Virtual Reality » vise à développer des outils technologiques et théoriques pour la reconstitution virtuelle d’expositions historiques et la documentation d’expositions en cours. Les recherches menées dans le cadre de ce projet ont notamment porté sur deux expositions pionnières : « Iconoclash » (4 mai–1er septembre 2002, ZKM) et « Les Immatériaux » (28 mars–15 juillet 1985, Centre Pompidou).

Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás et Marianne Schädler du Zentrum für Kunst und Medien de Karlsruhe (ZKM) présenteront la publication conclusive du projet européen.

Les artistes Jeremy Bailey, Damjanski, fabric | ch (Patrick Keller, Christian Babski, Christophe Guignard), Geraldine Juárez (en visioconférence), Carolyn Kirschner et Anne Le Troter présenteront ensuite les œuvres qu’ils et elles ont pu concevoir dans le cadre de l’exposition « Matter, Non-Matter, Anti-Matter » (3 décembre 2022–23 avril 2023, ZKM), restituant une partie des résultats du projet « Beyond Matter ».

Samedi 8 juillet 2023, 13h30–16h

« Les Immatériaux » : Artistes et historiens en conversation

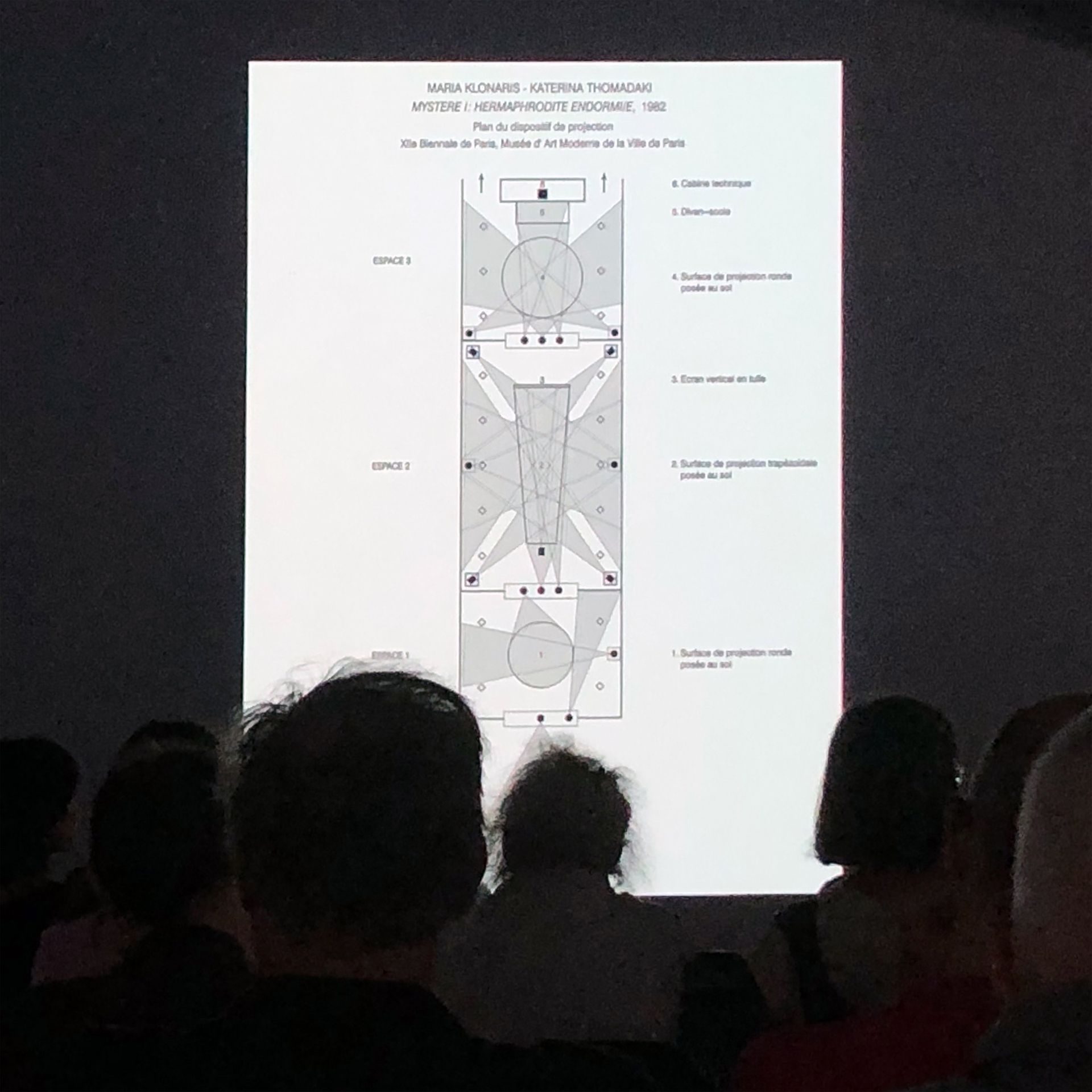

Le chercheur Andreas Broeckmann, ainsi que les artistes Katerina Thomadaki, Jean-Louis Boissier et Jean-Claude Fall reviennent sur « Les Immatériaux », exposition pionnière à laquelle ils ont participé.

Séance modérée par Marcella Lista, Philippe Bettinelli et Marie Vicet.

Samedi 8 juillet 2023, 16h-18h

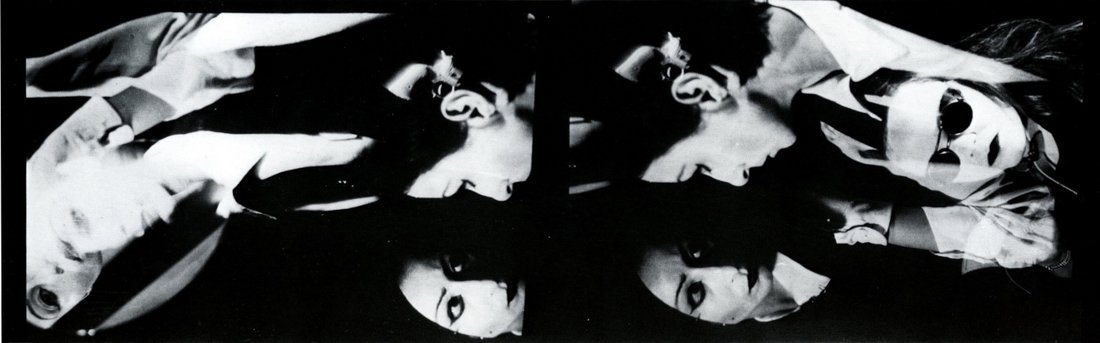

Maria Klonaris, Katerina Thomadaki, "Orlando-Hermaphrodite II", 1985, photographies noir et blanc sur panneau.

Courtesy Katerina Thomadaki.

Après « Les Immatériaux »

Projet porté par le curateur Hans Ulrich Obrist et l’artiste Philippe Parreno avec le soutien de LUMA Foundation, « Résistances » fait écho à l’exposition « Les Immatériaux » imaginée par Jean-François Lyotard. Resté inachevé, ce projet se trouve tout à la fois continué et réimaginé à travers des rencontres et la production de « films de pensée ».

Samedi 8 juillet 2023, 18h–19h30

La conversation se déroulera en français et en anglais, suivie d’une projection des « films de pensée ».

Films de pensée :

Produits et commandés par LUMA Foundation

Courtesy Maja Hoffmann / Luma Foundation Collection

- Être Résistances d’Albert Serra (2016, 198 min.)

« Être Résistances est un film qui résiste à en être un, c'est-à-dire qu'il résiste à la conscience et au langage cinématographique. C'est un film qui traite de théorie, de corps, de bruits, de discours, d'images, de jeu et d'ironie. C'est un film inspiré par son propre sujet invisible : l'exposition inexistante de Lyotard qui devrait résister à la communication. Le film est finalement cette exposition devenue réalité, mais comme un mirage et comme une illusion. » Albert Serra.

Séances, samedi 8 juillet 2023, à 13h30 et 17h30

Introduction par Albert Serra à 17h30

Cinéma 2, niveau –1

- The Rare Event de Ben Rivers et Ben Russell (2017, 48 min.) sous-titrage en français

Tourné dans un studio d'enregistrement parisien au plancher de bois grinçant, lors d'un « forum des idées » inaugural de trois jours consacré aux multiples possibilités de la Résistance – titre de l'exposition de Jean-François Lyotard qui devait faire suite à son exposition « Les Immatériaux » de 1985 –, les collaborateurs occasionnels Ben Rivers et Ben Russell (avec la contribution de l'artiste américain Peter Burr) ont produit ce qui apparaît d'abord comme un document structuraliste d'une discussion philosophique performée qui se transforme lentement en The Rare Event, un portail qui réunit toutes les dimensions en une seule.

- Resistances de Rachel Rose (2017-2019, 20 min.) VO en anglais

Ce court-métrage documente la deuxième rencontre sur les « Résistances » qui a eu lieu en février 2017 à New York, offrant ainsi un aperçu des conversations et des réflexions qui se sont déployées au cours de ce « forum des idées » organisé par Maja Hoffmann. Parmi les intervenants figurent Tyrone Hayes, Isabelle Thomas Fogiel, Reza Negarestani, Ariana Reines, Fred Moten, et de nombreux autres invités.

Projection, samedi 8 juillet 2023, à 19h30

Plan fixe du film "THE RARE EVENT" de Ben Rivers et Ben Russell.

Courtesy Maja Hoffmann / Luma Foundation Collection.

En lien avec la présentation temporaire au Musée, niveau 4, Espace de consultation des collections vidéos, films, sons et œuvres numériques :

« Les Immatériaux » (1985). Aperçus d'une manifestation postmoderne au Centre Pompidou. Du 5 juillet au 30 octobre 2023

Couverture de l'album Daft Punk, "Random Access Memories" © Zaina

Daft Punk, Random Access Memories

Session d’écoute avec Sonorium

Musique Session d'écoute, rencontre

5 Grammy Awards et un triomphe instantané, un tube planétaire ("Get Lucky"), une production incroyable de précision et des collaborations prestigieuses (Pharrell Williams, Julian Casablancas, Panda Bear, Giorgio Moroder…), Random Access Memories, le dernier album de Daft Punk, a marqué les esprits et installé le duo comme une figure majeure de la pop contemporaine.

À l'occasion de l'édition 10e anniversaire de l'album culte le 12 mai dernier, le Centre Pompidou et Sonorium vous invitent à une session d'écoute de l'album en intégralité, dans des conditions exceptionnelles grâce à une installation sonore immersive réalisée par l’Ircam et une nouvelle technologie immersive développée par sa filiale Ircam Amplify.

Dimanche 9 juillet 2023 – gratuit sur réservation

Sessions précédées d'une introduction par Éric Jean-Jean et suivies d'une discussion avec le public

Day-by-day program

Saturday, 8 July 2023

|

Continuous 11am-1pm |

Performance Christian Falsnaes, First (2016) |

|

Exhibition Reconstitution virtuelle de l'exposition « Les Immatériaux » |

|

| 1:30pm-2pm |

Meeting « Beyond Matter » Présentation de la publication conclusive du projet européen « Beyond Matter: Cultural Heritage on the Verge of Virtual Reality » |

| 1:30pm-5pm |

Screening Après « Les Immatériaux » : Films de pensée Être Résistances d’Albert Serra (2016, 198 min.) |

| 2pm-4pm |

Meeting « Beyond Matter » Présentation d'œuvres conçues dans le cadre de l'exposition « Matter, Non-matter, Anti-Matter » Avec les artistes Jeremy Bailey, Damjanski, fabric | ch (Patrick Keller, Christian Babski, Christophe Guignard), Geraldine Juárez (en visioconférence), Carolyn Kirschner et Anne Le Troter |

| 4pm-6pm |

Meeting « Les Immatériaux » : Artistes et historiens en conversation Avec Andreas Broeckmann, Katerina Thomadaki, Jean-Louis Boissier et Jean-Claude Fall Modérée par Marcella Lista, Philippe Bettinelli et Marie Vicet (Centre Pompidou) |

| 5:30pm-9pm |

Screening Après « Les Immatériaux » : Films de pensée Être Résistances d’Albert Serra (2016, 198 min.) En présence du cinéaste |

| 6pm-7:30pm |

Meeting Après « Les Immatériaux » : Rencontre en partenariat avec LUMA Foundation Avec Hans Ulrich Obrist, Philippe Parreno, Daniel Birnbaum, Anna Longo, Maja Hoffmann (en visioconférence) et Albert Serra |

| 7:30pm-9pm |

>Screening Après « Les Immatériaux » : Films de pensée

|

Sunday, 9 July 2023

|

Reconstitution virtuelle de l'exposition « Les Immatériaux »

|

Closing of the gallery 3 at the beginning of the day |

|

Continuous 3pm-9pm |

Performance Christian Falsnaes, First (2016) |

|

4pm-6pm 6:30pm-8:30pm |

Listening session, meeting Daft Punk, Random Access memories Introduction par Éric Jean-Jean Session d'écoute Discussion avec le public |

Guests

|

Hans Ulrich ObristVisual arts

|

Philippe ParrenoVisual arts

|

|

Jean-Louis BoissierNew media

|

Katerina ThomadakiNew media

|

Also in the presence of:

Jeremy Bailey, Daniel Birnbaum, Andreas Broeckmann, Damjanski, fabric | ch (Patrick Keller, Christian Babski, Christophe Guignard), Jean-Claude Fall, Maja Hoffmann, Éric Jean-Jean, Geraldine Juárez, Carolyn Kirschner, Anna Longo, Marianne Schädler, Albert Serra, Anne Le Troter.

Tuesday, October 05. 2021

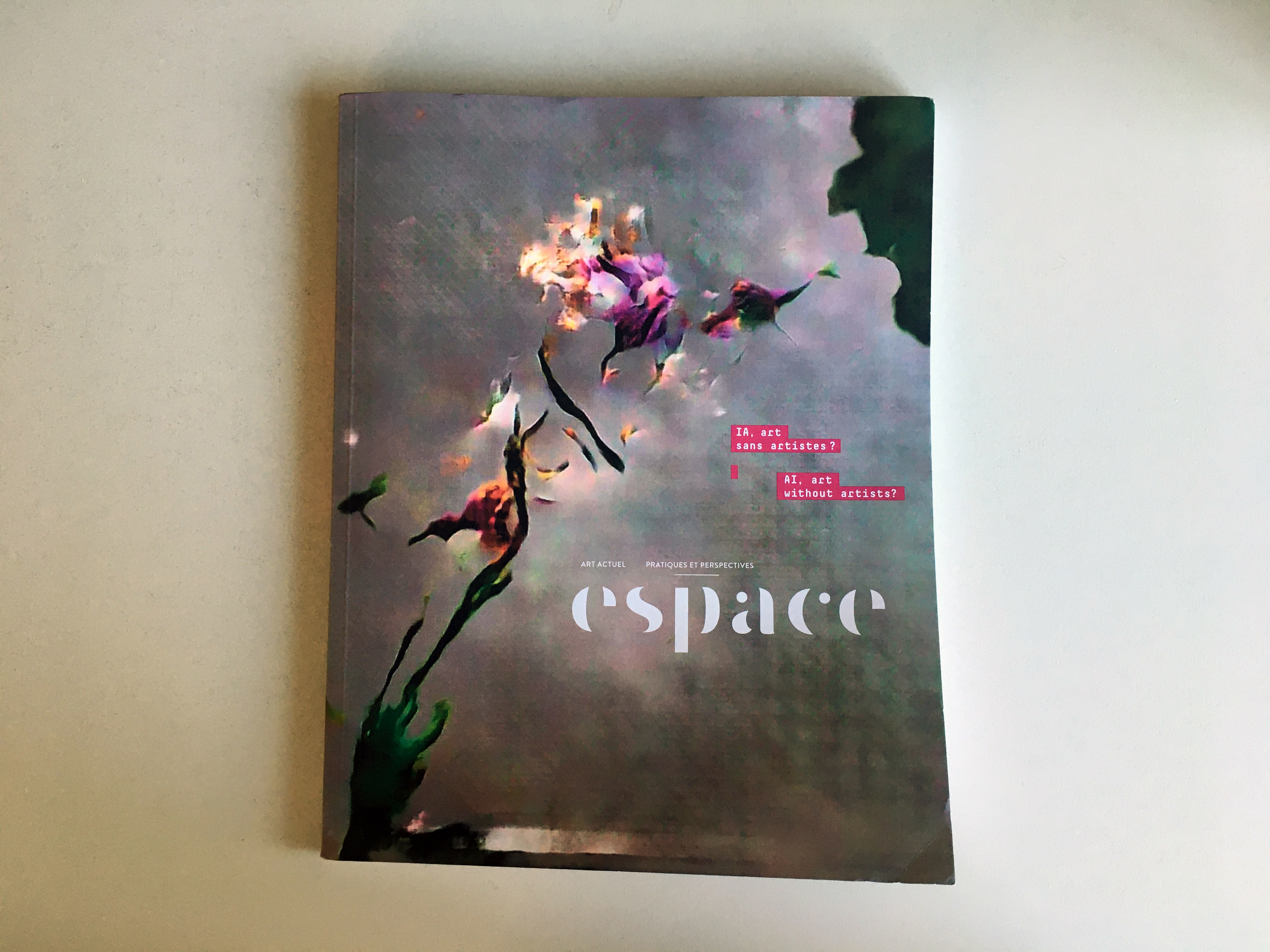

"Automation algorithmiques et créolisations", revue Espace (Montréal, 2020) | #publications #AI #algorithms #automated

Note: an interview about the implications of AI in art and the work of fabric | ch in particular, between Nathalie Bachand (writer & independant curator), Christophe Guignard and myself (both fabric | ch). The exchange happened in the context of a publication in the art magazine Espace, it was fruitful and we had the opportunity to develop on recent projects, like the "Atomized" serie of architectural works that will continue to evolve, as well as our monographic exhibition at Kunshalle Éphémère, entitled Environmental Devices (1997 - 2017).

-----

By fabric | ch

Tuesday, September 21. 2021

"Essais climatiques" by P. Rahm, Ed. B2 (Paris, 2020) | #2ndaugmentation #essay #AR #VR

Note: it is with great pleasure and interest that I read recently one of Philippe Rahm's last publication, "Essais climatiques" (published in French, by Editions B2), which consists in fact in a collection of articles published in the past 10+ years in various magazines, journals and exhibition catalogs. It is certainly less developed than the even more recent book, "L'histoire naturelle de l'architecture" (ed. Pavillon de l'Arsenal, 2020), but nonetheless an excellent and brief introduction to his thinking and work.

Philippe Rahm's call for the "return" of an "objective architecture", climatic and free of narrative issues, is of great interest. Especially at a time when we need to reduce our CO2 emissions and will need to reach energy objectives of slenderness. The historical reading of the postmodern era (in architecture), in relation to oil, vaccines and antibiotics is also really valuable in this context, when we are all looking to move forward this time in cultural history.

I also had the good surprise, and joy, to see the text "L'âge de la deuxième augmentation" finally published! It was written by Philippe back in 2009 probably, about the works of fabric | ch at the time, when we were preparing a publication that finally never came out... Though this text will also be part of a monographic publication that is expected to be finalized and self-published in 2022.

Via fabric | ch

-----

Friday, June 22. 2018

The empty brain | #neurosciences #nometaphor

Via Aeon

-----

Your brain does not process information, retrieve knowledge or store memories. In short: your brain is not a computer

Img. by Jan Stepnov (Twenty20).

No matter how hard they try, brain scientists and cognitive psychologists will never find a copy of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony in the brain – or copies of words, pictures, grammatical rules or any other kinds of environmental stimuli. The human brain isn’t really empty, of course. But it does not contain most of the things people think it does – not even simple things such as ‘memories’.

Our shoddy thinking about the brain has deep historical roots, but the invention of computers in the 1940s got us especially confused. For more than half a century now, psychologists, linguists, neuroscientists and other experts on human behaviour have been asserting that the human brain works like a computer.

To see how vacuous this idea is, consider the brains of babies. Thanks to evolution, human neonates, like the newborns of all other mammalian species, enter the world prepared to interact with it effectively. A baby’s vision is blurry, but it pays special attention to faces, and is quickly able to identify its mother’s. It prefers the sound of voices to non-speech sounds, and can distinguish one basic speech sound from another. We are, without doubt, built to make social connections.

A healthy newborn is also equipped with more than a dozen reflexes – ready-made reactions to certain stimuli that are important for its survival. It turns its head in the direction of something that brushes its cheek and then sucks whatever enters its mouth. It holds its breath when submerged in water. It grasps things placed in its hands so strongly it can nearly support its own weight. Perhaps most important, newborns come equipped with powerful learning mechanisms that allow them to change rapidly so they can interact increasingly effectively with their world, even if that world is unlike the one their distant ancestors faced.

Senses, reflexes and learning mechanisms – this is what we start with, and it is quite a lot, when you think about it. If we lacked any of these capabilities at birth, we would probably have trouble surviving.

But here is what we are not born with: information, data, rules, software, knowledge, lexicons, representations, algorithms, programs, models, memories, images, processors, subroutines, encoders, decoders, symbols, or buffers – design elements that allow digital computers to behave somewhat intelligently. Not only are we not born with such things, we also don’t develop them – ever.

We don’t store words or the rules that tell us how to manipulate them. We don’t create representations of visual stimuli, store them in a short-term memory buffer, and then transfer the representation into a long-term memory device. We don’t retrieve information or images or words from memory registers. Computers do all of these things, but organisms do not.

Computers, quite literally, process information – numbers, letters, words, formulas, images. The information first has to be encoded into a format computers can use, which means patterns of ones and zeroes (‘bits’) organised into small chunks (‘bytes’). On my computer, each byte contains 8 bits, and a certain pattern of those bits stands for the letter d, another for the letter o, and another for the letter g. Side by side, those three bytes form the word dog. One single image – say, the photograph of my cat Henry on my desktop – is represented by a very specific pattern of a million of these bytes (‘one megabyte’), surrounded by some special characters that tell the computer to expect an image, not a word.

Computers, quite literally, move these patterns from place to place in different physical storage areas etched into electronic components. Sometimes they also copy the patterns, and sometimes they transform them in various ways – say, when we are correcting errors in a manuscript or when we are touching up a photograph. The rules computers follow for moving, copying and operating on these arrays of data are also stored inside the computer. Together, a set of rules is called a ‘program’ or an ‘algorithm’. A group of algorithms that work together to help us do something (like buy stocks or find a date online) is called an ‘application’ – what most people now call an ‘app’.

Forgive me for this introduction to computing, but I need to be clear: computers really do operate on symbolic representations of the world. They really store and retrieve. They really process. They really have physical memories. They really are guided in everything they do, without exception, by algorithms.

Humans, on the other hand, do not – never did, never will. Given this reality, why do so many scientists talk about our mental life as if we were computers?

In his book In Our Own Image (2015), the artificial intelligence expert George Zarkadakis describes six different metaphors people have employed over the past 2,000 years to try to explain human intelligence.

In the earliest one, eventually preserved in the Bible, humans were formed from clay or dirt, which an intelligent god then infused with its spirit. That spirit ‘explained’ our intelligence – grammatically, at least.

The invention of hydraulic engineering in the 3rd century BCE led to the popularity of a hydraulic model of human intelligence, the idea that the flow of different fluids in the body – the ‘humours’ – accounted for both our physical and mental functioning. The hydraulic metaphor persisted for more than 1,600 years, handicapping medical practice all the while.

By the 1500s, automata powered by springs and gears had been devised, eventually inspiring leading thinkers such as René Descartes to assert that humans are complex machines. In the 1600s, the British philosopher Thomas Hobbes suggested that thinking arose from small mechanical motions in the brain. By the 1700s, discoveries about electricity and chemistry led to new theories of human intelligence – again, largely metaphorical in nature. In the mid-1800s, inspired by recent advances in communications, the German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz compared the brain to a telegraph.

"The mathematician John von Neumann stated flatly that the function of the human nervous system is ‘prima facie digital’, drawing parallel after parallel between the components of the computing machines of the day and the components of the human brain"

Each metaphor reflected the most advanced thinking of the era that spawned it. Predictably, just a few years after the dawn of computer technology in the 1940s, the brain was said to operate like a computer, with the role of physical hardware played by the brain itself and our thoughts serving as software. The landmark event that launched what is now broadly called ‘cognitive science’ was the publication of Language and Communication (1951) by the psychologist George Miller. Miller proposed that the mental world could be studied rigorously using concepts from information theory, computation and linguistics.

This kind of thinking was taken to its ultimate expression in the short book The Computer and the Brain (1958), in which the mathematician John von Neumann stated flatly that the function of the human nervous system is ‘prima facie digital’. Although he acknowledged that little was actually known about the role the brain played in human reasoning and memory, he drew parallel after parallel between the components of the computing machines of the day and the components of the human brain.

Propelled by subsequent advances in both computer technology and brain research, an ambitious multidisciplinary effort to understand human intelligence gradually developed, firmly rooted in the idea that humans are, like computers, information processors. This effort now involves thousands of researchers, consumes billions of dollars in funding, and has generated a vast literature consisting of both technical and mainstream articles and books. Ray Kurzweil’s book How to Create a Mind: The Secret of Human Thought Revealed (2013), exemplifies this perspective, speculating about the ‘algorithms’ of the brain, how the brain ‘processes data’, and even how it superficially resembles integrated circuits in its structure.

The information processing (IP) metaphor of human intelligence now dominates human thinking, both on the street and in the sciences. There is virtually no form of discourse about intelligent human behaviour that proceeds without employing this metaphor, just as no form of discourse about intelligent human behaviour could proceed in certain eras and cultures without reference to a spirit or deity. The validity of the IP metaphor in today’s world is generally assumed without question.

But the IP metaphor is, after all, just another metaphor – a story we tell to make sense of something we don’t actually understand. And like all the metaphors that preceded it, it will certainly be cast aside at some point – either replaced by another metaphor or, in the end, replaced by actual knowledge.

Just over a year ago, on a visit to one of the world’s most prestigious research institutes, I challenged researchers there to account for intelligent human behaviour without reference to any aspect of the IP metaphor. They couldn’t do it, and when I politely raised the issue in subsequent email communications, they still had nothing to offer months later. They saw the problem. They didn’t dismiss the challenge as trivial. But they couldn’t offer an alternative. In other words, the IP metaphor is ‘sticky’. It encumbers our thinking with language and ideas that are so powerful we have trouble thinking around them.

The faulty logic of the IP metaphor is easy enough to state. It is based on a faulty syllogism – one with two reasonable premises and a faulty conclusion. Reasonable premise #1: all computers are capable of behaving intelligently. Reasonable premise #2: all computers are information processors. Faulty conclusion: all entities that are capable of behaving intelligently are information processors.

Setting aside the formal language, the idea that humans must be information processors just because computers are information processors is just plain silly, and when, some day, the IP metaphor is finally abandoned, it will almost certainly be seen that way by historians, just as we now view the hydraulic and mechanical metaphors to be silly.

If the IP metaphor is so silly, why is it so sticky? What is stopping us from brushing it aside, just as we might brush aside a branch that was blocking our path? Is there a way to understand human intelligence without leaning on a flimsy intellectual crutch? And what price have we paid for leaning so heavily on this particular crutch for so long? The IP metaphor, after all, has been guiding the writing and thinking of a large number of researchers in multiple fields for decades. At what cost?

In a classroom exercise I have conducted many times over the years, I begin by recruiting a student to draw a detailed picture of a dollar bill – ‘as detailed as possible’, I say – on the blackboard in front of the room. When the student has finished, I cover the drawing with a sheet of paper, remove a dollar bill from my wallet, tape it to the board, and ask the student to repeat the task. When he or she is done, I remove the cover from the first drawing, and the class comments on the differences.

Because you might never have seen a demonstration like this, or because you might have trouble imagining the outcome, I have asked Jinny Hyun, one of the student interns at the institute where I conduct my research, to make the two drawings. Here is her drawing ‘from memory’ (notice the metaphor):

And here is the drawing she subsequently made with a dollar bill present:

Jinny was as surprised by the outcome as you probably are, but it is typical. As you can see, the drawing made in the absence of the dollar bill is horrible compared with the drawing made from an exemplar, even though Jinny has seen a dollar bill thousands of times.

What is the problem? Don’t we have a ‘representation’ of the dollar bill ‘stored’ in a ‘memory register’ in our brains? Can’t we just ‘retrieve’ it and use it to make our drawing?

Obviously not, and a thousand years of neuroscience will never locate a representation of a dollar bill stored inside the human brain for the simple reason that it is not there to be found.

"The idea that memories are stored in individual neurons is preposterous: how and where is the memory stored in the cell?"

A wealth of brain studies tells us, in fact, that multiple and sometimes large areas of the brain are often involved in even the most mundane memory tasks. When strong emotions are involved, millions of neurons can become more active. In a 2016 study of survivors of a plane crash by the University of Toronto neuropsychologist Brian Levine and others, recalling the crash increased neural activity in ‘the amygdala, medial temporal lobe, anterior and posterior midline, and visual cortex’ of the passengers.

The idea, advanced by several scientists, that specific memories are somehow stored in individual neurons is preposterous; if anything, that assertion just pushes the problem of memory to an even more challenging level: how and where, after all, is the memory stored in the cell?

So what is occurring when Jinny draws the dollar bill in its absence? If Jinny had never seen a dollar bill before, her first drawing would probably have not resembled the second drawing at all. Having seen dollar bills before, she was changed in some way. Specifically, her brain was changed in a way that allowed her to visualise a dollar bill – that is, to re-experience seeing a dollar bill, at least to some extent.

The difference between the two diagrams reminds us that visualising something (that is, seeing something in its absence) is far less accurate than seeing something in its presence. This is why we’re much better at recognising than recalling. When we re-member something (from the Latin re, ‘again’, and memorari, ‘be mindful of’), we have to try to relive an experience; but when we recognise something, we must merely be conscious of the fact that we have had this perceptual experience before.

Perhaps you will object to this demonstration. Jinny had seen dollar bills before, but she hadn’t made a deliberate effort to ‘memorise’ the details. Had she done so, you might argue, she could presumably have drawn the second image without the bill being present. Even in this case, though, no image of the dollar bill has in any sense been ‘stored’ in Jinny’s brain. She has simply become better prepared to draw it accurately, just as, through practice, a pianist becomes more skilled in playing a concerto without somehow inhaling a copy of the sheet music.

From this simple exercise, we can begin to build the framework of a metaphor-free theory of intelligent human behaviour – one in which the brain isn’t completely empty, but is at least empty of the baggage of the IP metaphor.

As we navigate through the world, we are changed by a variety of experiences. Of special note are experiences of three types: (1) we observe what is happening around us (other people behaving, sounds of music, instructions directed at us, words on pages, images on screens); (2) we are exposed to the pairing of unimportant stimuli (such as sirens) with important stimuli (such as the appearance of police cars); (3) we are punished or rewarded for behaving in certain ways.

We become more effective in our lives if we change in ways that are consistent with these experiences – if we can now recite a poem or sing a song, if we are able to follow the instructions we are given, if we respond to the unimportant stimuli more like we do to the important stimuli, if we refrain from behaving in ways that were punished, if we behave more frequently in ways that were rewarded.

Misleading headlines notwithstanding, no one really has the slightest idea how the brain changes after we have learned to sing a song or recite a poem. But neither the song nor the poem has been ‘stored’ in it. The brain has simply changed in an orderly way that now allows us to sing the song or recite the poem under certain conditions. When called on to perform, neither the song nor the poem is in any sense ‘retrieved’ from anywhere in the brain, any more than my finger movements are ‘retrieved’ when I tap my finger on my desk. We simply sing or recite – no retrieval necessary.

A few years ago, I asked the neuroscientist Eric Kandel of Columbia University – winner of a Nobel Prize for identifying some of the chemical changes that take place in the neuronal synapses of the Aplysia (a marine snail) after it learns something – how long he thought it would take us to understand how human memory works. He quickly replied: ‘A hundred years.’ I didn’t think to ask him whether he thought the IP metaphor was slowing down neuroscience, but some neuroscientists are indeed beginning to think the unthinkable – that the metaphor is not indispensable.

A few cognitive scientists – notably Anthony Chemero of the University of Cincinnati, the author of Radical Embodied Cognitive Science (2009) – now completely reject the view that the human brain works like a computer. The mainstream view is that we, like computers, make sense of the world by performing computations on mental representations of it, but Chemero and others describe another way of understanding intelligent behaviour – as a direct interaction between organisms and their world.

My favourite example of the dramatic difference between the IP perspective and what some now call the ‘anti-representational’ view of human functioning involves two different ways of explaining how a baseball player manages to catch a fly ball – beautifully explicated by Michael McBeath, now at Arizona State University, and his colleagues in a 1995 paper in Science. The IP perspective requires the player to formulate an estimate of various initial conditions of the ball’s flight – the force of the impact, the angle of the trajectory, that kind of thing – then to create and analyse an internal model of the path along which the ball will likely move, then to use that model to guide and adjust motor movements continuously in time in order to intercept the ball.

That is all well and good if we functioned as computers do, but McBeath and his colleagues gave a simpler account: to catch the ball, the player simply needs to keep moving in a way that keeps the ball in a constant visual relationship with respect to home plate and the surrounding scenery (technically, in a ‘linear optical trajectory’). This might sound complicated, but it is actually incredibly simple, and completely free of computations, representations and algorithms.

"We will never have to worry about a human mind going amok in cyberspace, and we will never achieve immortality through downloading."

Two determined psychology professors at Leeds Beckett University in the UK – Andrew Wilson and Sabrina Golonka – include the baseball example among many others that can be looked at simply and sensibly outside the IP framework. They have been blogging for years about what they call a ‘more coherent, naturalised approach to the scientific study of human behaviour… at odds with the dominant cognitive neuroscience approach’. This is far from a movement, however; the mainstream cognitive sciences continue to wallow uncritically in the IP metaphor, and some of the world’s most influential thinkers have made grand predictions about humanity’s future that depend on the validity of the metaphor.

One prediction – made by the futurist Kurzweil, the physicist Stephen Hawking and the neuroscientist Randal Koene, among others – is that, because human consciousness is supposedly like computer software, it will soon be possible to download human minds to a computer, in the circuits of which we will become immensely powerful intellectually and, quite possibly, immortal. This concept drove the plot of the dystopian movie Transcendence (2014) starring Johnny Depp as the Kurzweil-like scientist whose mind was downloaded to the internet – with disastrous results for humanity.

Fortunately, because the IP metaphor is not even slightly valid, we will never have to worry about a human mind going amok in cyberspace; alas, we will also never achieve immortality through downloading. This is not only because of the absence of consciousness software in the brain; there is a deeper problem here – let’s call it the uniqueness problem – which is both inspirational and depressing.

Because neither ‘memory banks’ nor ‘representations’ of stimuli exist in the brain, and because all that is required for us to function in the world is for the brain to change in an orderly way as a result of our experiences, there is no reason to believe that any two of us are changed the same way by the same experience. If you and I attend the same concert, the changes that occur in my brain when I listen to Beethoven’s 5th will almost certainly be completely different from the changes that occur in your brain. Those changes, whatever they are, are built on the unique neural structure that already exists, each structure having developed over a lifetime of unique experiences.

This is why, as Sir Frederic Bartlett demonstrated in his book Remembering (1932), no two people will repeat a story they have heard the same way and why, over time, their recitations of the story will diverge more and more. No ‘copy’ of the story is ever made; rather, each individual, upon hearing the story, changes to some extent – enough so that when asked about the story later (in some cases, days, months or even years after Bartlett first read them the story) – they can re-experience hearing the story to some extent, although not very well (see the first drawing of the dollar bill, above).

This is inspirational, I suppose, because it means that each of us is truly unique, not just in our genetic makeup, but even in the way our brains change over time. It is also depressing, because it makes the task of the neuroscientist daunting almost beyond imagination. For any given experience, orderly change could involve a thousand neurons, a million neurons or even the entire brain, with the pattern of change different in every brain.

Worse still, even if we had the ability to take a snapshot of all of the brain’s 86 billion neurons and then to simulate the state of those neurons in a computer, that vast pattern would mean nothing outside the body of the brain that produced it. This is perhaps the most egregious way in which the IP metaphor has distorted our thinking about human functioning. Whereas computers do store exact copies of data – copies that can persist unchanged for long periods of time, even if the power has been turned off – the brain maintains our intellect only as long as it remains alive. There is no on-off switch. Either the brain keeps functioning, or we disappear. What’s more, as the neurobiologist Steven Rose pointed out in The Future of the Brain (2005), a snapshot of the brain’s current state might also be meaningless unless we knew the entire life history of that brain’s owner – perhaps even about the social context in which he or she was raised.

Think how difficult this problem is. To understand even the basics of how the brain maintains the human intellect, we might need to know not just the current state of all 86 billion neurons and their 100 trillion interconnections, not just the varying strengths with which they are connected, and not just the states of more than 1,000 proteins that exist at each connection point, but how the moment-to-moment activity of the brain contributes to the integrity of the system. Add to this the uniqueness of each brain, brought about in part because of the uniqueness of each person’s life history, and Kandel’s prediction starts to sound overly optimistic. (In a recent op-ed in The New York Times, the neuroscientist Kenneth Miller suggested it will take ‘centuries’ just to figure out basic neuronal connectivity.)

Meanwhile, vast sums of money are being raised for brain research, based in some cases on faulty ideas and promises that cannot be kept. The most blatant instance of neuroscience gone awry, documented recently in a report in Scientific American, concerns the $1.3 billion Human Brain Project launched by the European Union in 2013. Convinced by the charismatic Henry Markram that he could create a simulation of the entire human brain on a supercomputer by the year 2023, and that such a model would revolutionise the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders, EU officials funded his project with virtually no restrictions. Less than two years into it, the project turned into a ‘brain wreck’, and Markram was asked to step down.

We are organisms, not computers. Get over it. Let’s get on with the business of trying to understand ourselves, but without being encumbered by unnecessary intellectual baggage. The IP metaphor has had a half-century run, producing few, if any, insights along the way. The time has come to hit the DELETE key.

Thursday, April 12. 2018

Vlatko Vedral - Decoding Reality | #quantum #information #thermodynamics

More about Quantum Information by Vlatko Vedral and his book Decoding Reality.

Via Legalise Freedom

-----

Listen to the discussion online HERE (Youtube, 1h02).

...

Vlatko Vedral on Decoding Reality -- The Universe as Quantum Information. What is the nature of reality? Why is there something rather than nothing? These are the deepest questions that human beings have asked, that thinkers East and West have pondered over millennia. For a physicist, all the world is information. The Universe and its workings are the ebb and flow of information. We are all transient patterns of information, passing on the blueprints for our basic forms to future generations using a digital code called DNA.

Decoding Reality asks some of the deepest questions about the Universe and considers the implications of interpreting it in terms of information. It explains the nature of information, the idea of entropy, and the roots of this thinking in thermodynamics. It describes the bizarre effects of quantum behaviour such as 'entanglement', which Einstein called 'spooky action at a distance' and explores cutting edge work on harnessing quantum effects in hyperfast quantum computers, and how recent evidence suggests that the weirdness of the quantum world, once thought limited to the tiniest scales, may reach up into our reality.

The book concludes by considering the answer to the ultimate question: where did all of the information in the Universe come from? The answers considered are exhilarating and challenge our concept of the nature of matter, of time, of free will, and of reality itself.

Tuesday, April 10. 2018

I’m building a machine that breaks the rules of reality | #information #thermodynamics

Note: the title and beginning of the article is very promissing or teasing, so to say... But unfortunately not freely accessible without a subscription on the New Scientist. Yet as it promisses an interesting read, I do archive it on | rblg for record and future readings.

In the meantime, here's also an interesting interview (2010) from Vlatko, at the time when he published his book Decoding Reality () about Information with physicist Vlatko Vedral for The Guardian.

Via The Guardian

-----

...

And an extract from the article on the New Scientist:

I’m building a machine that breaks the rules of reality

We thought only fools messed with the cast-iron laws of thermodynamics – but quantum trickery is rewriting the rulebook, says physicist Vladko Vedral.

Martin Leon Barreto

By Vlatko Vedral

A FEW years ago, I had an idea that may sound a little crazy: I thought I could see a way to build an engine that works harder than the laws of physics allow.

You would be within your rights to baulk at this proposition. After all, the efficiency of engines is governed by thermodynamics, the most solid pillar of physics. This is one set of natural laws you don’t mess with.

Yet if I leave my office at the University of Oxford and stroll down the corridor, I can now see an engine that pays no heed to these laws. It is a machine of considerable power and intricacy, with green lasers and ions instead of oil and pistons. There is a long road ahead, but I believe contraptions like this one will shape the future of technology.

Better, more efficient computers would be just the start. The engine is also a harbinger of a new era in science. To build it, we have had to uncover a field called quantum thermodynamics, one set to retune our ideas about why life, the universe – everything, in fact – are the way they are.

Thermodynamics is the theory that describes the interplay between temperature, heat, energy and work. As such, it touches on pretty much everything, from your brain to your muscles, car engines to kitchen blenders, stars to quasars. It provides a base from which we can work out what sorts of things do and don’t happen in the universe. If you eat a burger, you must burn off the calories – or …

Related Links:

Monday, February 05. 2018

Environmental Devices · Projets & expérimentations (1997-2017) | #fabric|ch #exhibition

Note: 2017 was very busy (the reason why I wasn't able to post much on | rblg...), and the start of 2018 happens to be the same. Fortunately and unfortunatly!

I hope things will calm down a bit next Spring, but in the meantime, we're setting up an exhibition with fabric | ch. A selection of works retracing 20 years of activities, which purpose will be also to serve in the perspective of a photo shooting for a forthcoming book.

The event will take place in a disuse factory (yet a historical monument from the 2nd industrial era), near Lausanne.

If you are around, do not hesitate to knock at the door!

By fabric | ch

-----

Environmental Devices · Projets & expérimentations (1997-2017)

Image: Daniela & Tonatiuh.

During a few days, in the context of the preparation of a book, a selection of works retracing 20 years of activities of fabric | ch will be on display in a disused factory close to Lausanne.

·

Information: http://www.fabric.ch/xx/

·

Opening on February 9, 5.00-11.00pm

·

Visiting hours:

Saturday - Sunday 10-11.02, 4.00-8.00pm

Wednesday 14.02, 5.00-8.00pm

Friday-Saturday 16-17.02, 5.00-8.00pm.

·

Or by appointment: 021.3511021

Guided tours at 6.00pm

-----

Pendant quelques jours et dans le contexte de la création d'un livre monographique, accrochage d'une sélection de travaux retraçant 20 ans d'activités de fabric | ch.

·

Informations: http://www.fabric.ch/xx

·

Vernissage le 9 février, 17h-23h

·

Heures de visite:

Samedi - dimanche 10-11.02, 16h-20h

Mercredi 14.02, 17h-20h

Vendredi-samedi 16-17.02, 17h-20h00

·

Ou sur rendez-vous: 021.3511021

Visites commentées à 18h.

&

Thursday, September 21. 2017

Timothy Morton, “the philosopher prophet of the Anthropocene” | #hyperobjects #climate

Note: Timothy Morton introducing his concept of "hyperobjects" and "object-oriented philosophy".

Via e-flux via The Guardian (June 17)

-----

Image of Thimothy Morton.

The Guardian has a longread on the US-based British philosopher Timothy Morton, whose work combines object-oriented ontology and ecological concerns. The author of the piece, Alex Blasdel, discusses how Morton's ideas have spread far and wide—from the Serpentine Gallery to Newsweek magazine—and how his seemingly bleak outlook has a silver lining. Here's an excerpt:

Morton means not only that irreversible global warming is under way, but also something more wide-reaching. “We Mesopotamians” – as he calls the past 400 or so generations of humans living in agricultural and industrial societies – thought that we were simply manipulating other entities (by farming and engineering, and so on) in a vacuum, as if we were lab technicians and they were in some kind of giant petri dish called “nature” or “the environment”. In the Anthropocene, Morton says, we must wake up to the fact that we never stood apart from or controlled the non-human things on the planet, but have always been thoroughly bound up with them. We can’t even burn, throw or flush things away without them coming back to us in some form, such as harmful pollution. Our most cherished ideas about nature and the environment – that they are separate from us, and relatively stable – have been destroyed.

Morton likens this realisation to detective stories in which the hunter realises he is hunting himself (his favourite examples are Blade Runner and Oedipus Rex). “Not all of us are prepared to feel sufficiently creeped out” by this epiphany, he says. But there’s another twist: even though humans have caused the Anthropocene, we cannot control it. “Oh, my God!” Morton exclaimed to me in mock horror at one point. “My attempt to escape the web of fate was the web of fate.”

The chief reason that we are waking up to our entanglement with the world we have been destroying, Morton says, is our encounter with the reality of hyperobjects – the term he coined to describe things such as ecosystems and black holes, which are “massively distributed in time and space” compared to individual humans. Hyperobjects might not seem to be objects in the way that, say, billiard balls are, but they are equally real, and we are now bumping up against them consciously for the first time. Global warming might have first appeared to us as a bit of funny local weather, then as a series of independent manifestations (an unusually torrential flood here, a deadly heatwave there), but now we see it as a unified phenomenon, of which extreme weather events and the disruption of the old seasons are only elements.

It is through hyperobjects that we initially confront the Anthropocene, Morton argues. One of his most influential books, itself titled Hyperobjects, examines the experience of being caught up in – indeed, being an intimate part of – these entities, which are too big to wrap our heads around, and far too big to control. We can experience hyperobjects such as climate in their local manifestations, or through data produced by scientific measurements, but their scale and the fact that we are trapped inside them means that we can never fully know them. Because of such phenomena, we are living in a time of quite literally unthinkable change.

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.

Quicksearch

Categories

Calendar

|

|

July '25 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||