Sticky Postings

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Tuesday, June 07. 2016

Note: I've posted several articles about automation recently. This was the occasion to continue collect some thoughts about the topic (automation then) so as the larger social implications that this might trigger.

But it was also a "collection" that took place at a special moment in Switzerland when we had to vote about the "Revenu the Base Inconditionnel" (Unconditional Basic Income). I mentioned it in a previous post ("On Algorithmic Communism"), in particular the relation that is often made between this idea (Basic Income / Universal Income) and the probable evolution of work in the decades to come (less work for "humans" vs. more for "robots").

Well, the campain and votation triggered very interesting debates among the civil population, but in the end and predictably, the idea was largely rejected (~25% of the voters accepted it, with some small geographical areas that indeed acceted it at more than 50% --urban areas mainly--. Some where not so far, for exemple the city capital, Bern, voted at 40% for the RBI).

This was very new and a probably too (?) early question for the Swiss population, but it will undoubtedly become a growing debate in the decades to come. A question that has many important associated stakes.

-----

Press talking about the RBI, image from RTS website.

More about it (in French) on the website of the swiss television.

Friday, August 14. 2015

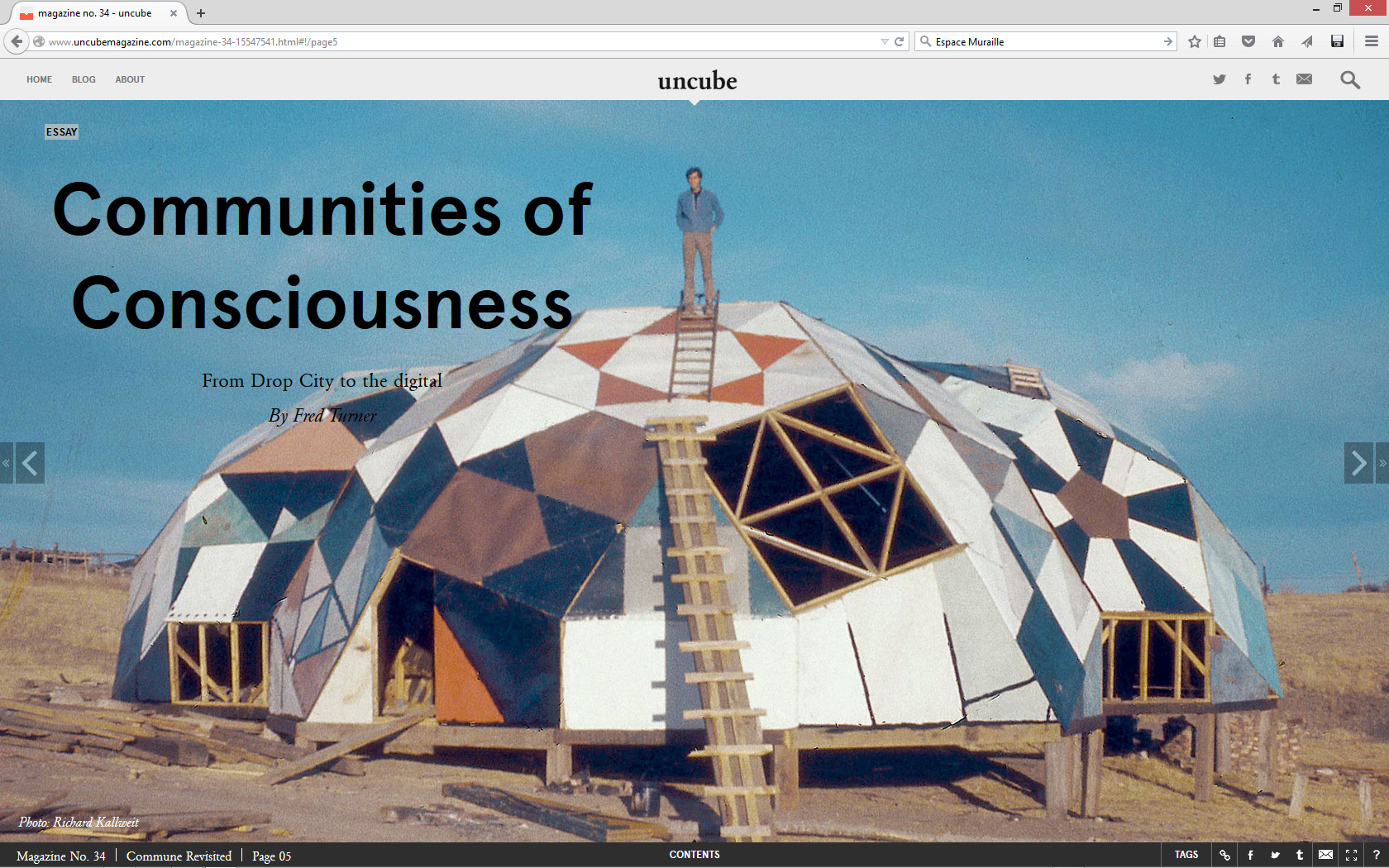

Note: While being interested in the idea of the commune for some time now --I've been digging into old stories, like the ones of the well named Haight-Ashbury's Diggers, or the Droppers, in connection to system theory, cybernetics and information theory and then of course, to THE Personal Computer as "small scale technology" , so as to "the biggest commune of all: the internet" (F. Turner)--.

The idealistic social flatness of the communes, anarchic yet with inevitable emerging order, its "counter" approach to western social organization but also the fact that in the end, the 60ies initiatives seemed to have "failed" for different reasons, interests me for further works. These "diggings" are also somehow connected to a ongoing project and tool we recently published online, a "data commune": Datadroppers (even so it is just a shared tool).

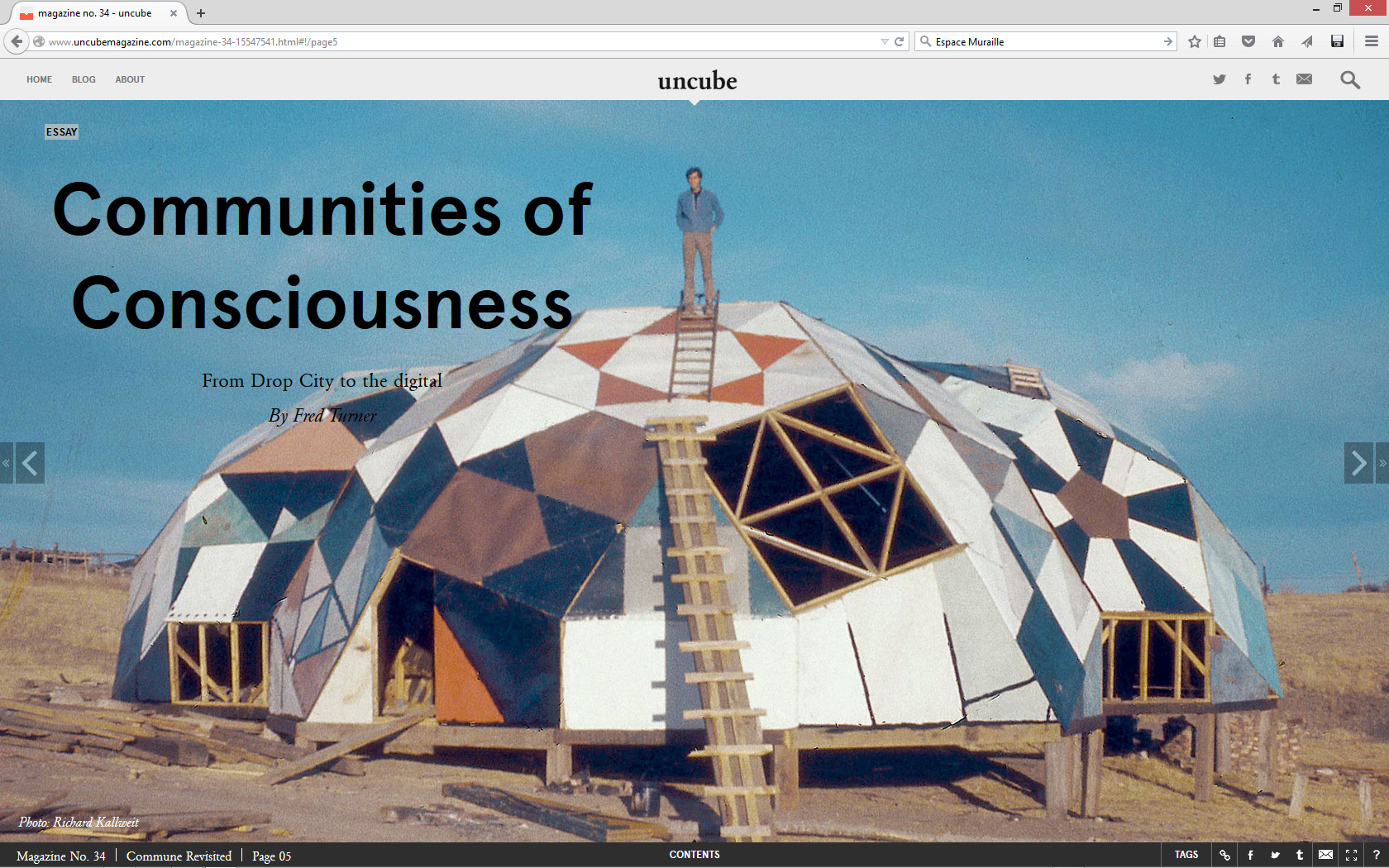

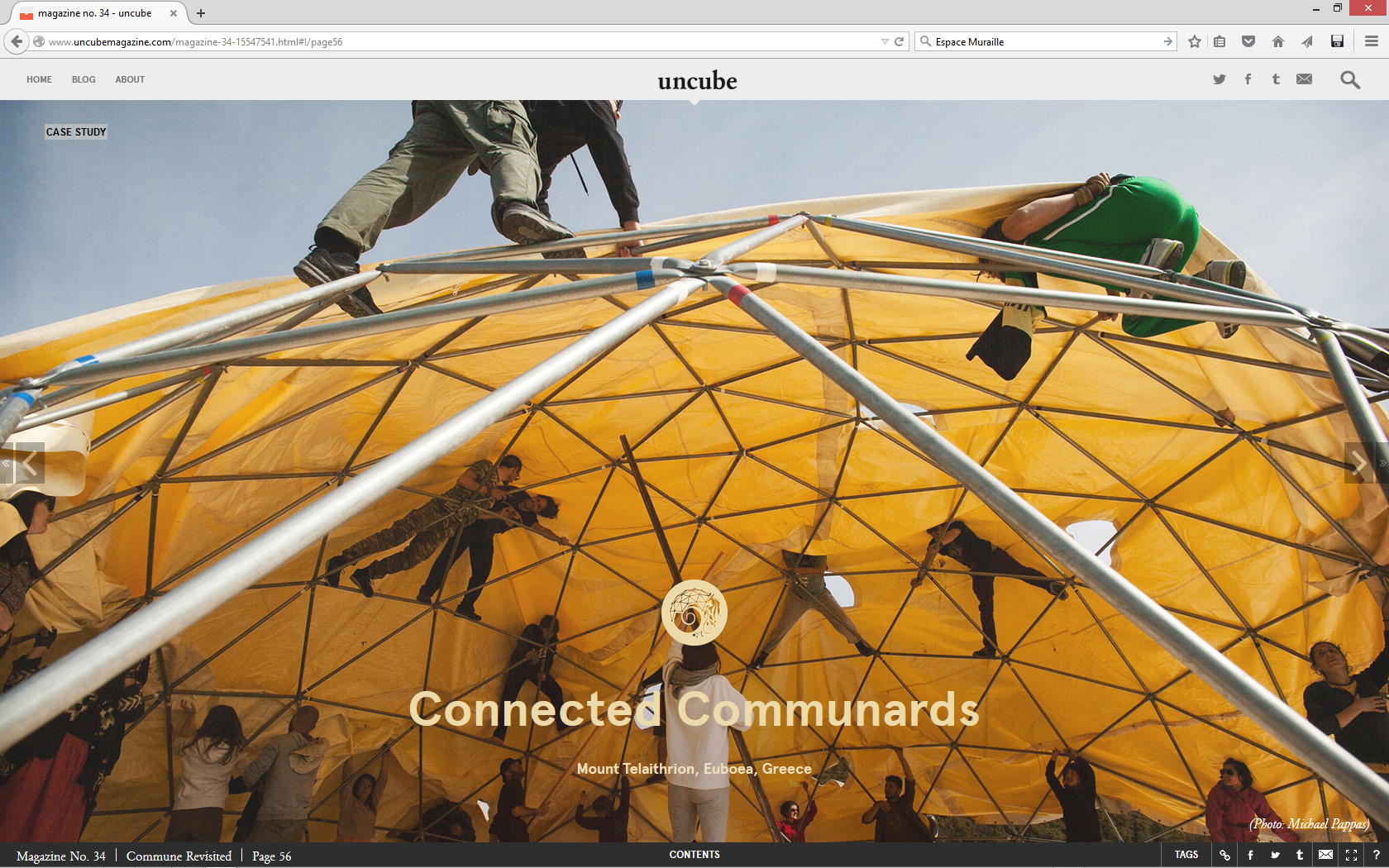

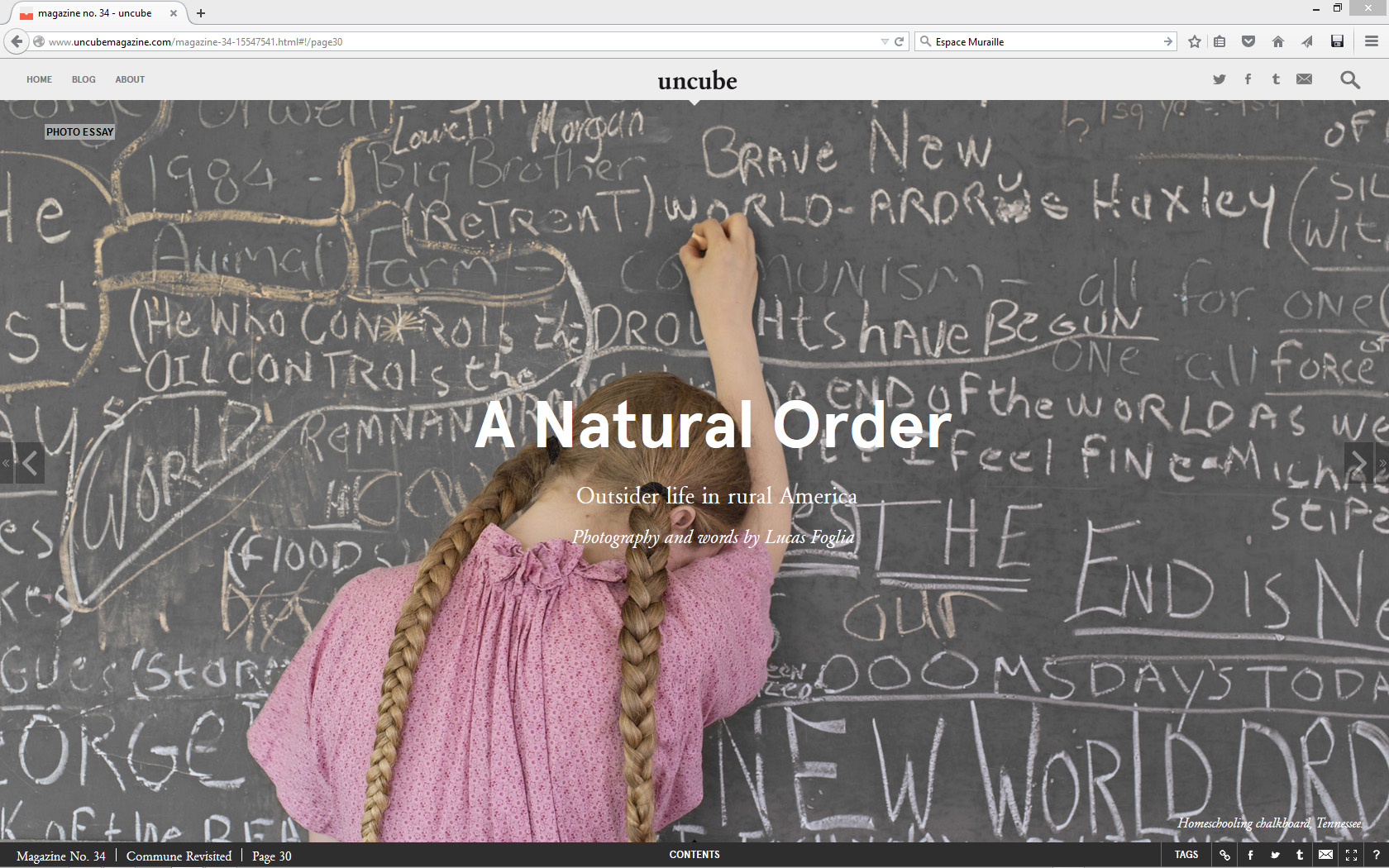

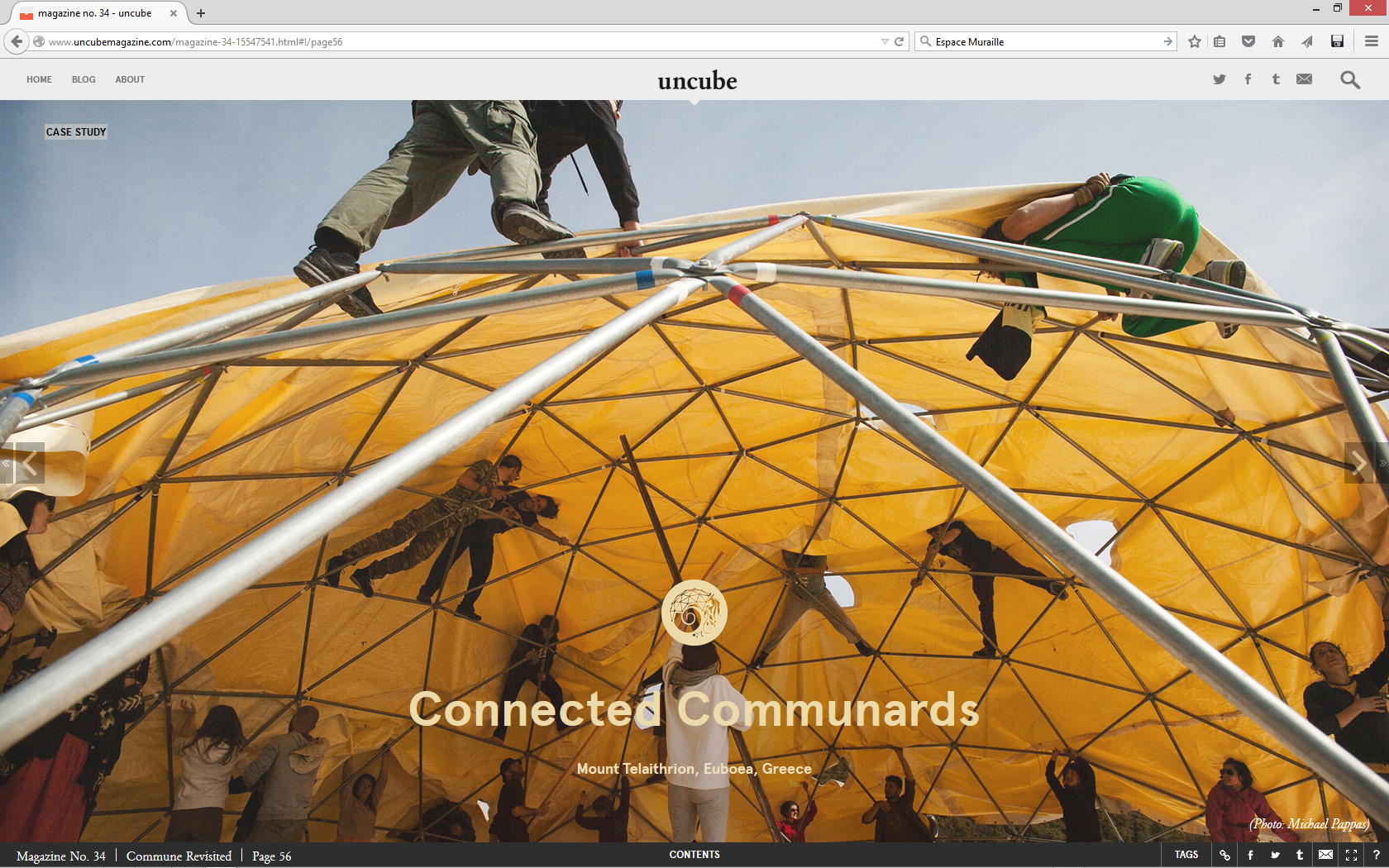

Following this interest, I came accross this latest online publication by uncube (Issue #34) about the Commune Revisited, which both have an historic approach to old experiments (like the one of Drop City), and to more recent ones, up to the "gated community" ... The idea of the editors being to investigate the diversity of the concepts. It brings an interesting contemporary twist and understanding to the general idea... In a time when we are totally fed up with neo liberalism.

Via Uncube

-----

"One year after our Urban Commons issue, we're returning to the idea of the communal, this time investigating just how diversly the concept of "commune" can be interpreted - and not always with entirely benevolent intentions or successful results.

Wether trying to escape a broken economy or an oppressive system via new forms of existence or looking to break the system itself via anarchic methodologies, forming a commune traditionnaly involves segregation or stepping "outside" society.

But no matter how off-grid and back-to-nature the contemporary communities that we investigate here are, it turns out they are far more connected than we think.

Turn on, tune out, drop in.

The editors"

Thursday, July 03. 2014

Note: I'm happy to learn that I'm not a "social capitalist"! I am not a "regular capitalist" either...

Via MIT Technology

-----

Social capitalists on Twitter are inadvertently ruining the network for ordinary users, say network scientists.

A couple of years, ago, network scientists began to study the phenomenon of “link farming” on Twitter and other social networks. This is the process in which spammers gather as many links or followers as possible to help spread their messages.

What these researchers discovered on Twitter was curious. They found that link farming was common among spammers. However, most of the people who followed the spam accounts came from a relatively small pool of human users on Twitter.

These people turn out to be individuals who are themselves trying to amass social capital by gathering as many followers as possible. The researchers called these people social capitalists.

That raises an interesting question: how do social capitalists emerge and what kind of influence do they have on the network? Today we get an answer of sorts, thanks to the work of Vincent Labatut at Galatasaray University in Turkey and a couple of pals who have carried out the first detailed study of social capitalists and how they behave.

These guys say that social capitalists fall into at least two different categories that reflect their success and the roles they play in linking together diverse communities. But they warn that social capitalists have a dark side too.

First, a bit of background. Twitter has around 600 million users who send 60 million tweets every day. On average, each Twitter user has around 200 followers and follows a similar number, creating a dynamic social network in which messages percolate through the network of links.

Many of these people use Twitter to connect with friends, family, news organizations, and so on. But a few, the social capitalists, use the network purely to maximize their own number of followers.

Social capitalists essentially rely on two kinds of reciprocity to amass followers. The first is to reassure other users that if they follow this user, then he or she will follow them back, a process called Follow Me and I Follow You or FMIFY. The second is to follow anybody and hope they follow back, a process called I Follow You, Follow Me or IFYFM.

This process takes place regardless of the content of messages, which is how they get mixed up with spammers, a point that turns out to be significant later.

Clearly, social capitalists are different from Twitter users who choose to follow people based on the content they tweet. The question that Labatut and co set out to answer is how to automatically identify social capitalists in Twitter and to work out how they sit within the Twitter network.

A clear feature of the reciprocity mechanism is that there will be a large overlap between the friends and followers of social capitalists. It’s possible to measure this overlap and categorize users accordingly. Social capitalists tend to have an overlap much closer to 100 percent than ordinary users.

Having identified social capitalists, another important measure is the ratio of friends to followers. Labatut and co say that those using the FMIFY strategy have a ratio smaller than 1 while those using the IFYFM will have a ration greater than 1 (because the number of followers is always greater than the number of friends).

One final way to categorize them is by their level of success. Here, Labatut and others set an arbitrary threshold of 10,000 followers. Social capitalists with more than this are obviously more successful than those with less.

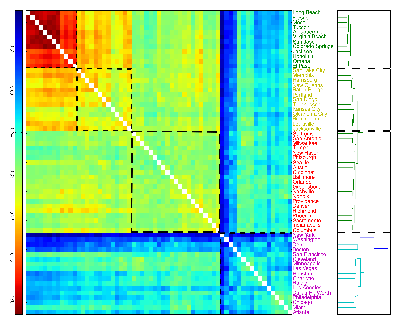

To study these groups, Labatut and coanalyze an anonymized dataset of 55 million Twitter users with two billion links between them. And they find some 160,000 users who fit the description of social capitalist.

In particular, the team is interested in how social capitalists are linked to communities within Twitter, that is groups of users who are more strongly interlinked than average.

It turns out that there is a surprisingly large variety of social capitalists playing different roles. “We find out the different kinds of social capitalists occupy very specific roles,” say Labatut and co.

For example, social capitalists with fewer than 10,000 followers tend not to have large numbers of links within a single community but links to lots of different communities. By contrast, those with more than 10,000 followers can have a strong presence in single communities as well as link disparate communities together. In both cases, social capitalists are significant because their messages travel widely across the entire Twitter network.

That has important consequences for the Twitter network. Labatut and co say there is a clear dark side to the role of social capitalists. “Because of this lack of interest in the content produced by the users they follow, social capitalists are not healthy for a service such as Twitter,” they say.

That’s because they provide an indiscriminate conduit for spammers to peddle their wares. “[Social capitalists’] behavior helps spammers gain influence, and more generally makes the task of finding relevant information harder for regular users,” say Labatut and co.

That’s an interesting insight that raises a tricky question for Twitter and other social networks. Finding social capitalists should now be straightforward now that Labatut and others have found a way to spot them automatically. But if social capitalists are detrimental, should their activities be restricted?

Ref:

http://arxiv.org/abs/1406.6611 : Identifying the Community Roles of Social Capitalists in the Twitter Network.

http://www.mpi-sws.org/~farshad/TwitterLinkfarming.pdf : Understanding and Combating Link Farming in the Twitter Social Network

Thursday, April 24. 2014

Via The New Aesthetic

-----

algopop:

“As algorithmic systems become more prevalent, I’ve begun to notice of a variety of emergent behaviors evolving to work around these constraints, to deal with the insufficiency of these black box systems…The first behavior is adaptation. These are situations where I bend to the system’s will. For example, adaptations to the shortcomings of voice UI systems — mispronouncing a friend’s name to get my phone to call them; overenunciating; or speaking in a different accent because of the cultural assumptions built into voice recognition. We see people contort their behavior to perform for the system so that it responds optimally.”

Alexis Lloyd (NYTimes R&D) shares some interesting views under the title In the Loop: Designing Conversations with Algorithms.

Wednesday, April 02. 2014

Via Wired

-----

By Kyle Vanhemert

The future we see in Her is one where technology has dissolved into everyday life.

A few weeks into the making of Her, Spike Jonze’s new flick about romance in the age of artificial intelligence, the director had something of a breakthrough. After poring over the work of Ray Kurzweil and other futurists trying to figure out how, exactly, his artificially intelligent female lead should operate, Jonze arrived at a critical insight: Her, he realized, isn’t a movie about technology. It’s a movie about people. With that, the film took shape. Sure, it takes place in the future, but what it’s really concerned with are human relationships, as fragile and complicated as they’ve been from the start.

Of course on another level Her is very much a movie about technology. One of the two main characters is, after all, a consciousness built entirely from code. That aspect posed a unique challenge for Jonze and his production team: They had to think like designers. Assuming the technology for AI was there, how would it operate? What would the relationship with its “user” be like? How do you dumb down an omniscient interlocutor for the human on the other end of the earpiece?

When AI is cheap, what does all the other technology look like?

For production designer KK Barrett, the man responsible for styling the world in which the story takes place, Her represented another sort of design challenge. Barrett’s previously brought films like Lost in Translation, Marie Antoinette, and Where the Wild Things Are to life, but the problem here was a new one, requiring more than a little crystal ball-gazing. The big question: In a world where you can buy AI off the shelf, what does all the other technology look like?

In Her, the future almost looks more like the past.

Technology Shouldn’t Feel Like Technology

One of the first things you notice about the “slight future” of Her, as Jonze has described it, is that there isn’t all that much technology at all. The main character Theo Twombly, a writer for the bespoke love letter service BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com, still sits at a desktop computer when he’s at work, but otherwise he rarely has his face in a screen. Instead, he and his fellow future denizens are usually just talking, either to each other or to their operating systems via a discrete earpiece, itself more like a fancy earplug anything resembling today’s cyborgian Bluetooth headsets.

In this “slight future” world, things are low-tech everywhere you look. The skyscrapers in this futuristic Los Angeles haven’t turned into towering video billboards a la Blade Runner; they’re just buildings. Instead of a flat screen TV, Theo’s living room just has nice furniture.

This is, no doubt, partly an aesthetic concern; a world mediated through screens doesn’t make for very rewarding mise en scene. But as Barrett explains it, there’s a logic to this technological sparseness. “We decided that the movie wasn’t about technology, or if it was, that the technology should be invisible,” he says. “And not invisible like a piece of glass.” Technology hasn’t disappeared, in other words. It’s dissolved into everyday life.

Here’s another way of putting it. It’s not just that Her, the movie, is focused on people. It also shows us a future where technology is more people-centric. The world Her shows us is one where the technology has receded, or one where we’ve let it recede. It’s a world where the pendulum has swung back the other direction, where a new generation of designers and consumers have accepted that technology isn’t an end in itself–that it’s the real world we’re supposed to be connecting to. (Of course, that’s the ideal; as we see in the film, in reality, making meaningful connections is as difficult as ever.)

Theo still has a desktop display at work and at home, but elsewhere technology is largely invisible.

Theo Twombly still sits at a desktop computer when he’s at work, but otherwise he rarely has his face in a screen.

Jonze had help in finding the contours of this slight future, including conversations with designers from New York-based studio Sagmeister & Walsh and an early meeting with Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, principals at architecture firm DS+R. As the film’s production designer, Barrett was responsible for making it a reality.

Throughout that process, he drew inspiration from one of his favorite books, a visual compendium of futuristic predictions from various points in history. Basically, the book reminded Barrett what not to do. “It shows a lot of things and it makes you laugh instantly, because you say, ‘those things never came to pass!’” he explains. “But often times, it’s just because they over-thought it. The future is much simpler than you think.”

That’s easy to say in retrospect, looking at images of Rube Goldbergian kitchens and scenes of commute by jet pack. But Jonze and Barrett had the difficult task of extrapolating that simplification forward from today’s technological moment.

Theo’s home gives us one concise example. You could call it a “smart house,” but there’s little outward evidence of it. What makes it intelligent isn’t the whizbang technology but rather simple, understated utility. Lights, for example, turn off and on as Theo moves from room to room. There’s no app for controlling them from the couch; no control panel on the wall. It’s all automatic. Why? “It’s just a smart and efficient way to live in a house,” says Barrett.

Today’s smartphones were another object of Barrett’s scrutiny. “They’re advanced, but in some ways they’re not advanced whatsoever,” he says. “They need too much attention. You don’t really want to be stuck engaging them. You want to be free.” In Barrett’s estimation, the smartphones just around the corner aren’t much better. “Everyone says we’re supposed to have a curved piece of flexible glass. Why do we need that? Let’s make it more substantial. Let’s make it something that feels nice in the hand.”

Theo’s smartphone was designed to be “substantial,” something that first and foremost “feels good in the hand.”

Theo’s phone in the film is just that–a handsome hinged device that looks more like an art deco cigarette case than an iPhone. He uses it far less frequently than we use our smartphones today; it’s functional, but it’s not ubiquitous. As an object, it’s more like a nice wallet or watch. In terms of industrial design, it’s an artifact from a future where gadgets don’t need to scream their sophistication–a future where technology has progressed to the point that it doesn’t need to look like technology.

All of these things contribute to a compelling, cohesive vision of the future–one that’s dramatically different from what we usually see in these types of movies. You could say that Her is, in fact, a counterpoint to that prevailing vision of the future–the anti-Minority Report. Imagining its world wasn’t about heaping new technology on society as we know it today. It was looking at those places where technology could fade into the background, integrate more seamlessly. It was about envisioning a future, perhaps, that looked more like the past. “In a way,” says Barrett, “my job was to undesign the design.”

The Holy Grail: A Discrete User Interface

The greatest act of undesigning in Her, technologically speaking, comes with the interface used throughout the film. Theo doesn’t touch his computer–in fact, while he has a desktop display at home and at work, neither have a keyboard. Instead, he talks to it. “We decided we didn’t want to have physical contact,” Barrett says. “We wanted it to be natural. Hence the elimination of software keyboards as we know them.”

Again, voice control had benefits simply on the level of moviemaking. A conversation between Theo and Sam, his artificially intelligent OS, is obviously easier for the audience to follow than anything involving taps, gestures, swipes or screens. But the voice-based UI was also a perfect fit for a film trying to explore what a less intrusive, less demanding variety of technology might look like.

The main interface in the film is voice–Theo communicates to his AI OS through a discrete ear plug.

Indeed, if you’re trying to imagine a future where we’ve managed to liberate ourselves from screens, systems based around talking are hard to avoid. As Barrett puts it, the computers we see in Her “don’t ask us to sit down and pay attention” like the ones we have today. He compares it to the fundamental way music beats out movies in so many situations. Music is something you can listen to anywhere. It’s complementary. It lets you operate in 360 degrees. Movies require you to be locked into one place, looking in one direction. As we see in the film, no matter what Theo’s up to in real life, all it takes to bring his OS into the fold is to pop in his ear plug.

Looking at it that way, you can see the audio-based interface in Her as a novel form of augmented reality computing. Instead of overlaying our vision with a feed, as we’ve typically seen it, Theo gets a one piped into his ear. At the same time, the other ear is left free to take in the world around him.

Barrett sees this sort of arrangement as an elegant end point to the trajectory we’re already on. Think about what happens today when we’re bored at the dinner table. We check our phones. At the same time, we realize that’s a bit rude, and as Barrett sees it, that’s one of the great promises of the smartwatch: discretion.

“They’re a little more invisible. A little sneakier,” he says. Still, they’re screens that require eyeballs. Instead, Barrett says, “imagine if you had an ear plug in and you were getting your feed from everywhere.” Your attention would still be divided, but not nearly as flagrantly.

Theo chops it up with a holographic videogame character.

Of course, a truly capable voice-based UI comes with other benefits. Conversational interfaces make everything easier to use. When every different type of device runs an OS that can understand natural language, it means that every menu, every tool, every function is accessible simply by requesting it.

That, too, is a trend that’s very much alive right now. Consider how today’s mobile operating systems, like iOS and ChromeOS, hide the messy business of file systems out of sight. Theo, with his voice-based valet as intermediary, is burdened with even less under-the-hood stuff than we are today. As Barrett puts it: “We didn’t want him fiddling with things and fussing with things.” In other words, Theo lives in a future where everything, not just his iPad, “just works.”

Theo lives in a future where everything, not just his iPad, “just works.”

AI: the ultimate UX challenge

The central piece of invisible design in Her, however, is that of Sam, the artificially intelligent operating system and Theo’s eventual romantic partner. Their relationship is so natural that it’s easy to forget she’s a piece of software. But Jonze and company didn’t just write a girlfriend character, label it AI, and call it a day. Indeed, much of the film’s dramatic tension ultimately hinges not just on the ways artificial intelligence can be like us but the ways it cannot.

Much of Sam’s unique flavor of AI was written into the script by Jonze himself. But her inclusion led to all sorts of conversations among the production team about the nature of such a technology. “Anytime you’re dealing with trying to interact with a human, you have to think of humans as operating systems. Very advanced operating systems. Your highest goal is to try to emulate them,” Barrett says. Superficially, that might mean considering things like voice pattern and sensitivity and changing them based on the setting or situation.

Even more quesitons swirled when they considered how an artificially intelligent OS should behave. Are they a good listener? Are they intuitive? Do they adjust to your taste and line of questioning? Do they allow time for you to think? As Barrett puts it, “you don’t want a machine that’s always telling you the answer. You want one that approaches you like, ‘let’s solve this together.’”

In essence, it means that AI has to be programmed to dumb itself down. “I think it’s very important for OSes in the future to have a good bedside manner.” Barrett says. “As politicians have learned, you can’t talk at someone all the time. You have to act like you’re listening.”

AI’s killer app, as we see in the film, is the ability to adjust to the emotional state of its user.

As we see in the film, though, the greatest asset of AI might be that it doesn’t have one fixed personality. Instead, its ability to figure out what a person needs at a given moment emerges as the killer app.

Theo, emotionally desolate in the midst of a hard divorce, is having a hard time meeting people, so Sam goads him into going on a blind date. When Theo’s friend Amy splits up with her husband, her own artificially intelligent OS acts as a sort of therapist. “She’s helping me work through some things,” Amy says of her virtual friend at one point.

In our own world, we may be a long way from computers that are able to sense when we’re blue and help raise our spirits in one way or another. But we’re already making progress down this path. In something as simple as a responsive web layout or iOS 7′s “Do Not Disturb” feature, we’re starting to see designs that are more perceptive about the real world context surrounding them–where or how or when they’re being used. Google Now and other types of predictive software are ushering in a new era of more personalized, more intelligent apps. And while Apple updating Siri with a few canned jokes about her Hollywood counterpart might not amount to a true sense of humor, it does serve as another example of how we’re making technology more human–a preoccupation that’s very much alive today.

Personal comment:

While I do agree with the idea that technology is becoming in some ways banal --or maybe, to use a better word, just common-- and that the future might not be about flying cars, fancy allover hologram interfaces or backup video cities populated with personal clones), that it might be "in service of", will "vanish" or "recede" into our daily atmospheres, environments, architectures, furnitures, clothes if not bodies or cells, we have to keep in mind that this could (will) make it even more intrusive.

When technology won't make debate anymore (when it will be common), when it will be both ambient and invisible, passively accepted if not undergone, then there will be lots of room for ... (gap to be filled by many names) to fulfill their wildest dreams.

We also have to keep in mind that when technology enters an untapped domain (let's say as an example social domain, for the last ten years), it engineers what was, in some cases and before, a common good (you didn't had to pay or trade some data to talk with somebody before). So to say, to engineer common goods (i.e. social relationships, but why not in the future love, air, genome --already the case--, etc.) turns them into products: commodification. Not always a good thing if I could say so... This definitely looks like a goal from the economy: how to turn everything into something you can sell, and information technology is quite good in helping do that.

-

And btw... even so technology might "recede", I'm not so keen with the rather "skeumorph" design of the "ai cell phone" in the movie so far (haven't seen the movie yet)..;). and oh my, I definitely hope this won't be our future. It looks like a Jobs design!

Tuesday, February 04. 2014

Via #algopop

-----

By Plummer Fernandez

Love in the time of algorithms by Dan Slater. A book about the online dating industry. I think the title of this book alone makes this relevant to #algopop.

Also researchers at the University of Iowa are developing an algorithm that much like Netflix, will recommend partners for dating based on data-mining rather than user input. The concept is based on the assumptions that a user’s self-curated profile is not entirely truthful, and that he or she 'may not know themselves well enough to know their own tastes in the opposite sex', so algorithms could potentially get to know the real you, and your potential partner, through your dating-site browsing habits.

Via Creative Applications

-----

By Lauren McCarthy & Kyle McDonald

AIT (“Social Hacking”), taught for the first time this semester by Lauren McCarthy and Kyle McDonald at NYU’s ITP, explored the structures and systems of social interactions, identity, and self representation as mediated by technology. The semester was spent developing projects that altered or disrupted social space in an attempt to reveal existing patterns or truths about our experiences and technologies, and possibilities for richer interactions.

The class began by exploring the idea of “social glitch”, drawing on ideas from glitch theory, social psychology, and sociology, including Harold Garfinkel’s breaching experiments, Stanley Milgram’s subway experiments, and Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical analysis of social interaction. If “glitch” describes when a system breaks down and reveals something about its structure or self in the process, what might this look like in the context of social space?

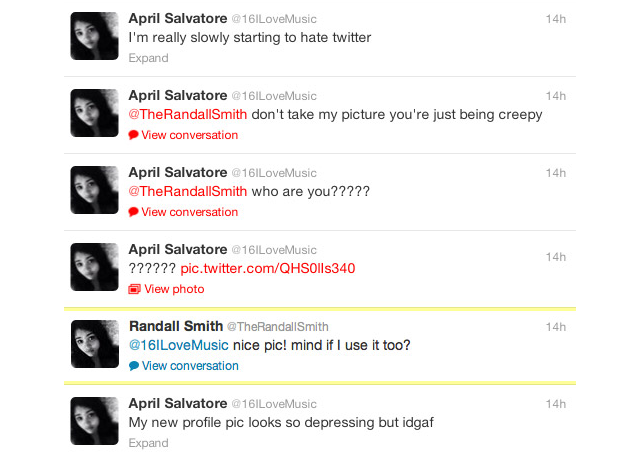

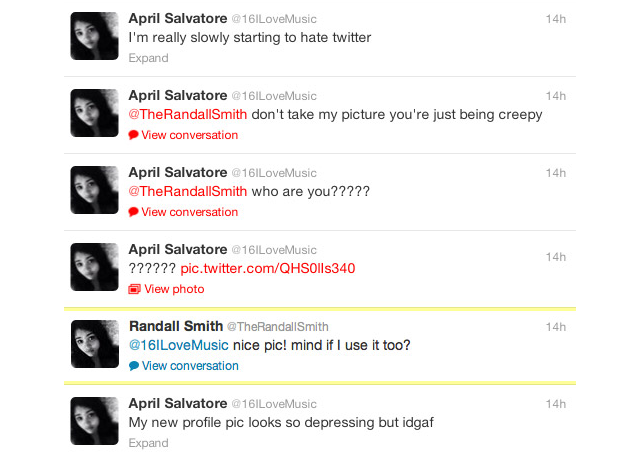

Bill Lindmeier wrote a Ruby script using the Twitter Stream API to listen for any Tweets containing “new profile pic.” When a Tweet was posted the script would download the user’s profile image, upload it to his own account and then reply to the user with a randomly selected Tweet, like “awesome pic!”. The reactions ranged from humored to furious.

Along similar lines, Ilwon Yoon implemented a script that searched for Tweets containing “I am all alone” and replied with cute images obtained from a Google image search and “you are not alone” text.

Mack Howell built on the in-class exercise of asking strangers to borrow their phone then doing something unexpected with it, asking to take pictures of strangers’ browsing history.

The class next turned it’s attention to social automation and APIs, and the potential for their creative misuse.

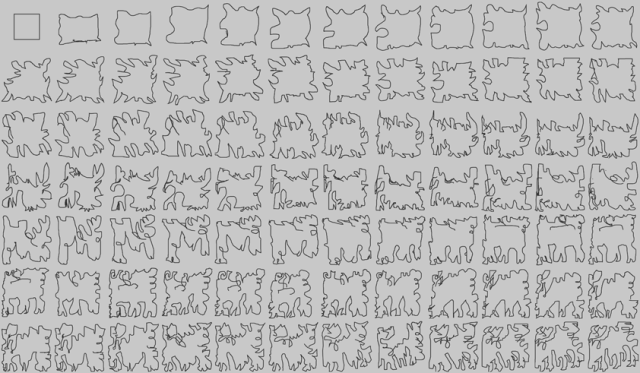

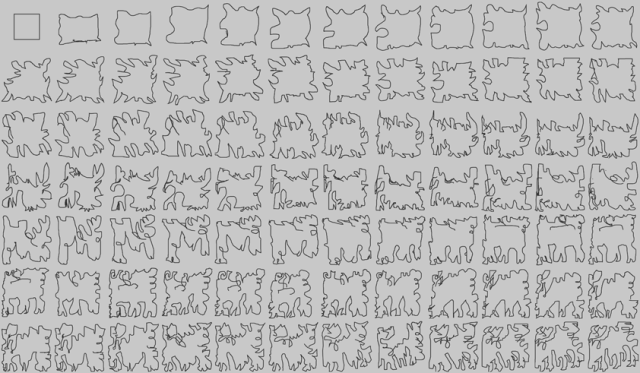

Gal Sasson used the Amazon Mechanical Turk API to create collaborative noise, creating a chain where each turker was prompted to replicate a drawing from the previous turker, seeding the first turker with a perfect square.

Mack Howell used the Google Street View Image API to map out the traceroutes from his location to the data centers of the his most frequently visited IPs.

In another assignment, students were prompted to create an “HPI” (human programming interface) that allowed others to control some aspect of their lives, and perform the experiment for one full week.

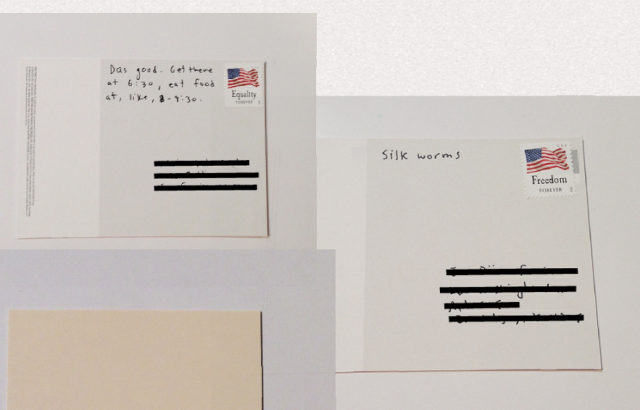

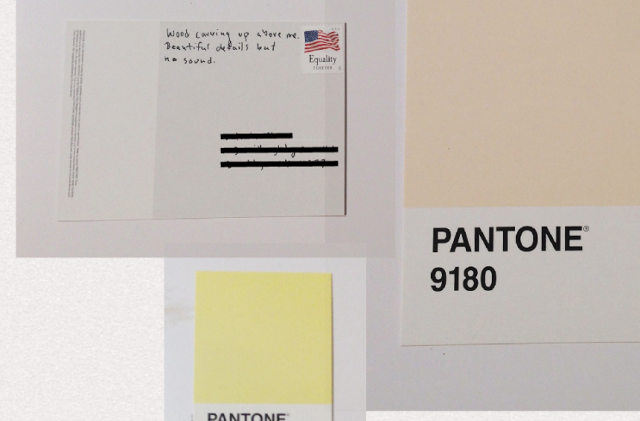

Anytime an email or Twitter direct message was sent to Ben Kauffman with the hashtag #brainstamp and a mailing address, he would get an SMS with the information and promptly right down on a postcard whatever was in his head at that exact moment. He would then mail the thoughts, at turns surreal and mundane, to the awaiting recipient. An alternative to normal social media, Ben challenged us to find ways to be more present while documenting our lives.

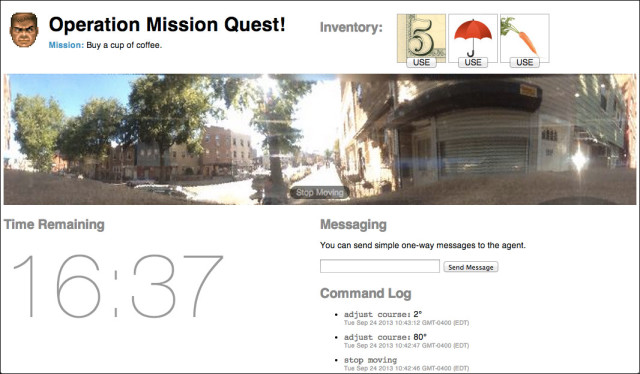

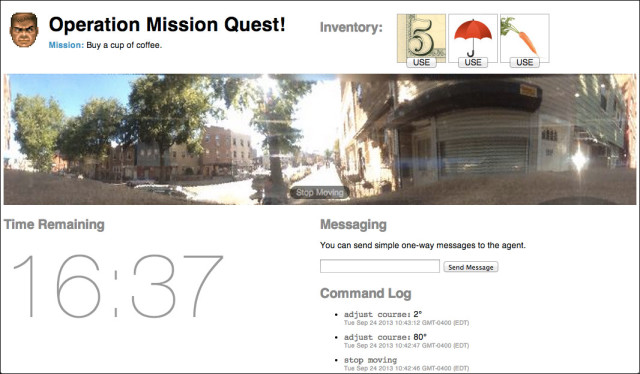

Bill Lindmeier invited his friends to control his movements in realtime through a Google-street-view-esque video interface, and asked them to complete a simple mission: Buy some coffee in under 20 minutes. The tools at their disposal: $5, an umbrella and a carrot.

Mack Howell created a journal written by Amazon Mechanical Turk workers, asking them to generate diary entries based on OpenPaths data sent automatically as he moved around.

In a project called My Friends Complete Me, Su Hyun Kim posted binary questions on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and let her friends collective opinion determine her life choices, including deciding whether to change her last name when she got married.

A couple weeks were spent having focused discussions about security, privacy, and surveillance, including topics like quantified self, government surveillance and historical regimes of naming, and readings from Bruce Schneier, Evgeny Morozov and Steve Mann. In parallel, students were asked to examine their own social lives and compulsively document, share, intercept, impersonate, anonymize and misinterpret.

Mike Allison explored our voyeuristic nature and cultural craving for surveillance, allowing users to watch someone watch someone who may be watching them. In order to watch, users must lend their own camera to the system.

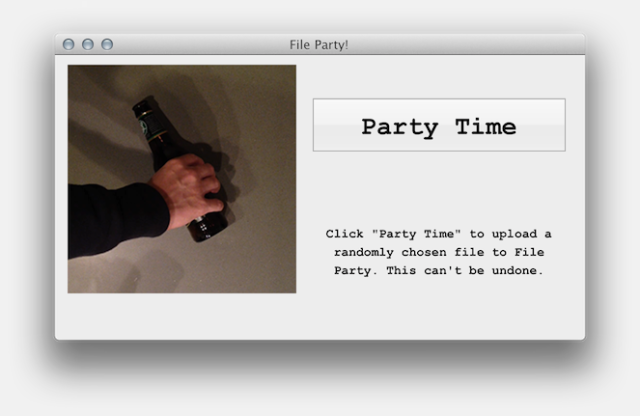

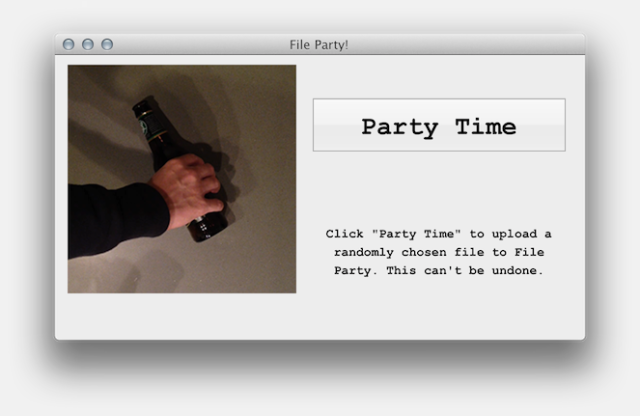

Bill Lindmeier created an app called File Party, a repository of files that have been randomly selected and uploaded from peoples’ hard-drive. In order to view the files, you have to upload one yourself.

In a unit on computer vision and linguistic analysis, students were paired up and asked to create a chat application that provided a filter or adapter that improved their interaction.

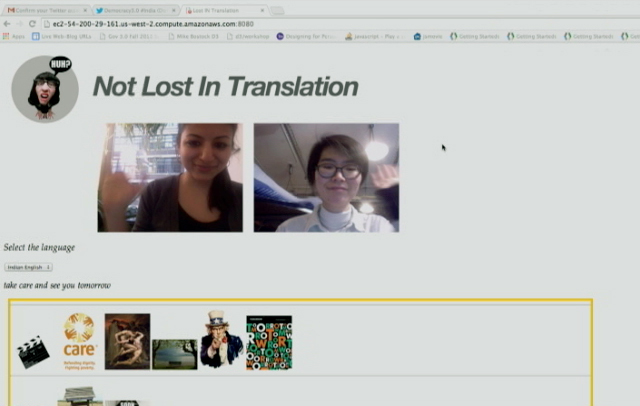

Realizing how much is lost in translation and accents, Tarana Gupta and Hanbyul Jo developed a video chat tool which allows users to talk in their respective language and and displays in real-time text and images corresponding to what is being said.

In FlapChat, Su Hyun Kim and Gal Sasson rethought the way we interact with the web camera, allowing users to flap their arms to fly around a virtual environment while chatting.

Overall, the most successful moments in the class were the ones where students had an opportunity to examine an otherwise common technology or interaction from a new perspective. Short in-class exercises like “ask a stranger to use their phone, and do something unexpected” gave students a reference point for discussion. The “HPI” assignment gave students an unusual challenge of “performing” something for a week, lead to its own set of difficulties and realizations that are distinct from purely technical or aesthetic exercises. On the first day of class a contract was handed out requiring that students respect others’ positions in class, and take responsibility for any actions outside of class. This created a unfamiliar atmosphere and opened up the students to question their freedoms and responsibilities towards each other.

In the future, each two- or three-week section might be expanded to fit a whole semester. Of particular interest were the computer vision, security and surveillance, and mobile platforms sections. Leftover discussion from security and surveillance spilled into the next week, and assignments for mobile platforms could have been taken far beyond the proof-of-concept or design-only stages.

More information about the class, including the complete syllabus, reading lists, and some example code, is available on GitHub.

A condensed version of this class will be taught in January at GAFFTA in San Francisco, details will be announced soon with more information here.

About the Tutors:

Kyle McDonald is a media artist who works with code, with a background in philosophy and computer science. He creates intricate systems with playful realizations, sharing the source and challenging others to create and contribute. Kyle is a regular collaborator on arts-engineering initiatives such as openFrameworks, having developed a number of extensions which provide connectivity to powerful image processing and computer vision libraries. For the past few years, Kyle has applied these techniques to problems in 3D sensing, for interaction and visualization, starting with structured light techniques, and later the Kinect. Kyle’s work ranges from hyper-formal glitch experiments to tactical and interrogative installations and performance. He was recently Guest Researcher in residence at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media, Japan, and is currently adjunct professor at ITP.

http://kylemcdonald.net

Lauren McCarthy is an artist and programmer based in Brooklyn, NY. She is adjunct faculty at RISD and NYU ITP, and a current resident at Eyebeam. She holds an MFA from UCLA and a BS Computer Science and BS Art and Design from MIT. Her work explores the structures and systems of social interactions, identity, and self-representation, and the potential for technology to mediate, manipulate, and evolve these interactions. She is fascinated by the slightly uncomfortable moments when patterns are shifted, expectations are broken, and participants become aware of the system. Her artwork has been shown in a variety of contexts, including the Conflux Festival, SIGGRAPH, LACMA, the Japan Media Arts Festival, the File Festival, the WIRED Store, and probably to you without you knowing it at some point while interacting with her.

http://lauren-mccarthy.com

Monday, February 03. 2014

An interesting call for papers about "algorithmic living" at University of California, Davis.

Via The Programmable City

-----

Call for papers

Thursday and Friday – May 15-16, 2014 at the University of California, Davis

Submission Deadline: March 1, 2014 algorithmiclife (at) gmail.com

As algorithms permeate our lived experience, the boundaries and borderlands of what can and cannot be adapted, translated, or incorporated into algorithmic thinking become a space of contention. The principle of the algorithm, or the specification of the potential space of action, creates the notion of a universal mode of specification of all life, leading to discourses on empowerment, efficiency, openness, and inclusivity. But algorithms are ultimately only able to make intelligible and valuable that which can be discretized, quantified, operationalized, proceduralized, and gamified, and this limited domain makes algorithms necessarily exclusive.

Algorithms increasingly shape our world, our thought, our economy, our political life, and our bodies. The algorithmic response of NSA networks to threatening network activity increasingly brings privacy and political surveillance under algorithmic control. At least 30% of stock trading is now algorithmic and automatic, having already lead to several otherwise inexplicable collapses and booms. Devices such as the Fitbit and the NikeFuel suggest that the body is incomplete without a technological supplement, treating ‘health’ as a quantifiable output dependent on quantifiable inputs. The logic of gamification, which finds increasing traction in educational and pedagogical contexts, asserts that the world is not only renderable as winnable or losable, but is in fact better–i.e. more effective–this way. The increased proliferation of how-to guides, from HGTV and DIY television to the LifeHack website, demonstrate a growing demand for approaching tasks with discrete algorithmic instructions.

This conference seeks to explore both the specific uses of algorithms and algorithmic culture more broadly, including topics such as: gamification, the computational self, data mining and visualization, the politics of algorithms, surveillance, mobile and locative technology, and games for health. While virtually any discipline could have something productive to say about the matter, we are especially seeking contributions from software studies, critical code studies, performance studies, cultural and media studies, anthropology, the humanities, and social sciences, as well as visual art, music, sound studies and performance. Proposals for experimental/hybrid performance-papers and multimedia artworks are especially welcome.

Areas open for exploration include but are not limited to: daily life in algorithmic culture; gamification of education, health, politics, arts, and other social arenas; the life and death of big data and data visualization; identity politics and the quantification of selves, bodies, and populations; algorithm and affect; visual culture of algorithms; algorithmic materiality; governance, regulation, and ethics of algorithms, procedures, and protocols; algorithmic imaginaries in fiction, film, video games, and other media; algorithmic culture and (dis)ability; habit and addiction as biological algorithms; the unrule-able/unruly in the (post)digital age; limits and possibilities of emergence; algorithmic and proto-algorithmic compositional methods (e.g., serialism, Baroque fugue); algorithms and (il)legibility; and the unalgorithmic.

Please send proposals to algorithmiclife (at) gmail.com by March 1, 2014.

Decisions will be made by March 8, 2014.

Tuesday, November 05. 2013

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

Twitter data reveals the cities that set trends and those that follow. And the difference may be in the way air passengers carry information across the country, by-passing the Internet, say network scientists.

One of the defining properties of social networks is the ease with which information can spread across them. This flow leads to information avalanches in which videos or photographs or other content becomes viral across entire countries, continents and even the globe.

It’s easy to imagine that these trends are simply the result of the properties of the network. Indeed, there are plenty of studies that seem to show this.

But in recent years, researchers have become increasingly interested in the relationship between a network and the geography it is superimposed on. What role does geography play in the emergence and spread of trends? And which areas are trend setters and which are trend followers?

Today we get an answer of sorts thanks to the work of Emilio Ferrara and pals at Indiana University in Bloomington. These guys have examined the way trends emerge in cities across the US and how they spread to other cities and beyond.

Their research allows them to classify US cities as sources, those that lead the way in trends, or those that follow the trends which the team call sinks.

Their research also leads to a curious conclusion–that air travel plays a crucial role in the spread of information around the country This implies that trends spread from one part of the country to another not over the internet but via air passengers, just like diseases.

The method these guys use is straightforward. Twitter publishes a continuously updated list pf the the top ten most popular phrases or hashtags on its webpage. It also has webpages showing the trending topics for each of 63 US cities.

To capture the way these trends emerge and spread, Ferrra and co set up a web crawler to check each list every ten minutes between 12 April and 30 May 2013. In this way the collected over 11,000 different phrases and hashtags that became popular throughout these 50 days.

They then plotted the evolution of these trends in each US city over time. This allowed them to study how trends spread from one city to another and to look for clusters of cities in which the same topics trend together.

The results are revealing. They say most trends die away quickly–around 70 per cent of trends last only 20 minutes and only 0.3 per cent last more than a day.

Ferrara and co say they can see three distinct geographical regions that share similar trends–the East Coast, the Midwest and Southwest. It’s easy to imagine how trends arise at a low level and spread through the region through local links such as friends.

But these guys say there is also a fourth cluster of influential cities that also form a group where the emergence of trends is related. However, these place are not geographically related. They are metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles, New York, Atlanta, Chicago and so on.

What links these places is not geography but airports, say Ferrara and co. Their hypothesis is that topics trend in these places because of the influence of air passengers. In other words, trending topics spread just like diseases.

Ferrara and co have created a list of the cities that act as trend setters and those that act as trend followers.

The top five sources of trends are: Los Angeles, Cincinnati, Washington, Seattle and New York.

The top five trend followers (or sinks) are: Oklahoma City, Albuquerque, El Paso, Omaha and Kansas City.

That’s a fascinating result. In a sense it’s obvious that the large scale movement of people will influence the apread of information However, it’s not obvious that this should happen at a rate that is comparable to the spread of trends across the internet itself.

And it raises an interesting question that Ferrara and co hope to answer in future work. “Does information travel faster by airplane than over the Internet?” they ask.

We’ll be watching for when they reveal the answer.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1310.2671 : Traveling Trends: Social Butterflies or Frequent Fliers?

Personal comment:

Interesting results (information travels by plane either, like diseases...), yet when only 0.3% of "trends" last more than a day, we can wonder if it even matters to have concerns about the 99.7% other ones (just some crap lolcats stuff ?)... or that on the contrary, it could possibly be the revelator of incredible "short time" pulses of "things/memes/subjects" in and in-between cities?

Nonetheless, if being more picky about the trends that are analyzed, this could certainly reveal some interesting and spreading "mood" patterns between cities.

|