Sticky Postings

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Monday, April 27. 2015

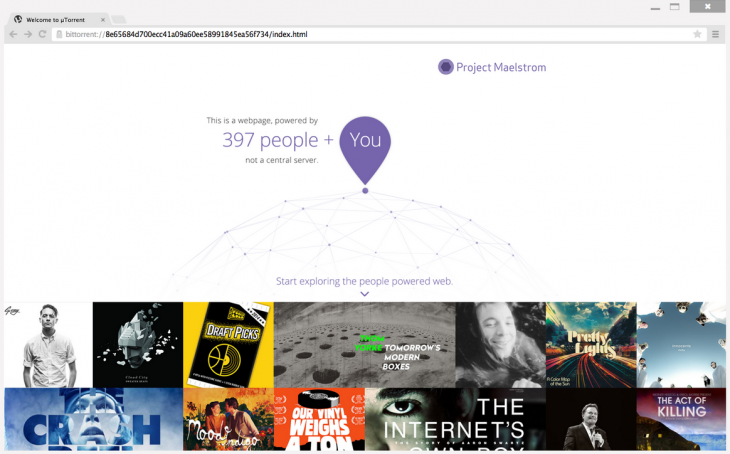

Note: we often complain on this blog about the centralization in progress (through the actions of corporations) within the "networked world", which is therefore less and less "horizontal" or distributed (and then more pyramidal, proprietary, etc.)

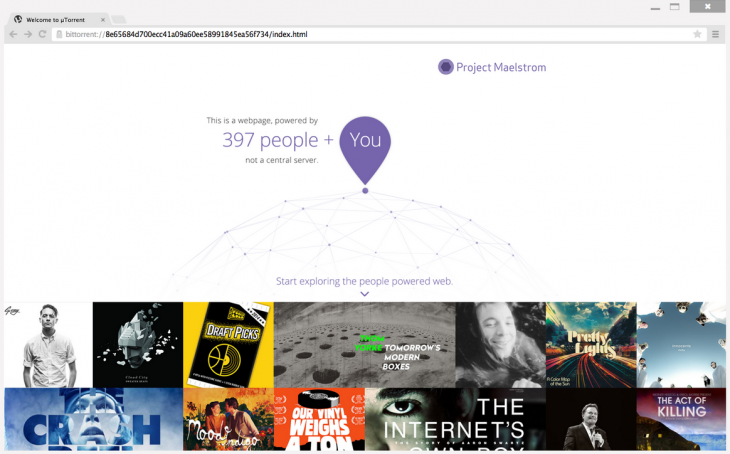

Here comes an interesting initiative by BitTorrent, following their previous distributed file storage/"cloud" system (Sync): a new browser, Maelstrom. This is interesting indeed, because instead of the "web image" --indexed web content-- being hosted in proprietary servers (i.e. the ones of Google), so as your browsing history and everything else, it seems that it will distribute this "web image" on as many "personal" devices as possible. Keeping it fully decentralized therefore. Well... let's wait and see, as the way it will really work has not been explained very well so far (we can speculate that the copy of the content will be distributed indeed, but we don't know much about their business model --what about the metadata aggregated by all the user's web searches and usages? this could still be centralized... Yet note even so they state that it will not be).

Undoubtedly, the BitTorrent architecture is an interesting one when it comes to speak about networked content and decentralization. Yet it is now also a big company... with several venture capital partners (including the ones of Facebook, Spotify, Dropbox, Jawbone, etc.). "Techno-capitalism" (as Eric Sadin names it) is unfortunately one of the biggest force of centralization and commodification. So this is a bit puzzling, but let's not be pessimistic and trust their words for now, until we don't?

Via TheNextWeb via Compouted·Blg

-----

Back in December, we reported on the alpha for BitTorrent’s Maelstrom, a browser that uses BitTorrent’s P2P technology in order to place some control of the Web back in users’ hands by eliminating the need for centralized servers.

Maelstrom is now in beta, bring it one step closer to official release. BitTorrent says more than 10,000 developers and 3,500 publishers signed up for the alpha, and it’s using their insights to launch a more stable public beta.

Along with the beta comes the first set of developer tools for the browser, helping publishers and programmers to build their websites around Maelstrom’s P2P technology. And they need to – Maelstrom can’t decentralize the Internet if there isn’t any native content for the platform.

It’s only available on Windows at the moment but if you’re interested and on Microsoft’s OS, you can download the beta from BitTorrent now.

Monday, January 27. 2014

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

By Evgeny Morozov

As Web companies and government agencies analyze ever more information about our lives, it’s tempting to respond by passing new privacy laws or creating mechanisms that pay us for our data. Instead, we need a civic solution, because democracy is at risk.

In 1967, The Public Interest, then a leading venue for highbrow policy debate, published a provocative essay by Paul Baran, one of the fathers of the data transmission method known as packet switching. Titled “The Future Computer Utility,” the essay speculated that someday a few big, centralized computers would provide “information processing … the same way one now buys electricity.”

Our home computer console will be used to send and receive messages—like telegrams. We could check to see whether the local department store has the advertised sports shirt in stock in the desired color and size. We could ask when delivery would be guaranteed, if we ordered. The information would be up-to-the-minute and accurate. We could pay our bills and compute our taxes via the console. We would ask questions and receive answers from “information banks”—automated versions of today’s libraries. We would obtain up-to-the-minute listing of all television and radio programs … The computer could, itself, send a message to remind us of an impending anniversary and save us from the disastrous consequences of forgetfulness.

It took decades for cloud computing to fulfill Baran’s vision. But he was prescient enough to worry that utility computing would need its own regulatory model. Here was an employee of the RAND Corporation—hardly a redoubt of Marxist thought—fretting about the concentration of market power in the hands of large computer utilities and demanding state intervention. Baran also wanted policies that could “offer maximum protection to the preservation of the rights of privacy of information”:

Highly sensitive personal and important business information will be stored in many of the contemplated systems … At present, nothing more than trust—or, at best, a lack of technical sophistication—stands in the way of a would-be eavesdropper … Today we lack the mechanisms to insure adequate safeguards. Because of the difficulty in rebuilding complex systems to incorporate safeguards at a later date, it appears desirable to anticipate these problems.

Sharp, bullshit-free analysis: techno-futurism has been in decline ever since.

All the privacy solutions you hear about are on the wrong track.

To read Baran’s essay (just one of the many on utility computing published at the time) is to realize that our contemporary privacy problem is not contemporary. It’s not just a consequence of Mark Zuckerberg’s selling his soul and our profiles to the NSA. The problem was recognized early on, and little was done about it.

Almost all of Baran’s envisioned uses for “utility computing” are purely commercial. Ordering shirts, paying bills, looking for entertainment, conquering forgetfulness: this is not the Internet of “virtual communities” and “netizens.” Baran simply imagined that networked computing would allow us to do things that we already do without networked computing: shopping, entertainment, research. But also: espionage, surveillance, and voyeurism.

If Baran’s “computer revolution” doesn’t sound very revolutionary, it’s in part because he did not imagine that it would upend the foundations of capitalism and bureaucratic administration that had been in place for centuries. By the 1990s, however, many digital enthusiasts believed otherwise; they were convinced that the spread of digital networks and the rapid decline in communication costs represented a genuinely new stage in human development. For them, the surveillance triggered in the 2000s by 9/11 and the colonization of these pristine digital spaces by Google, Facebook, and big data were aberrations that could be resisted or at least reversed. If only we could now erase the decade we lost and return to the utopia of the 1980s and 1990s by passing stricter laws, giving users more control, and building better encryption tools!

A different reading of recent history would yield a different agenda for the future. The widespread feeling of emancipation through information that many people still attribute to the 1990s was probably just a prolonged hallucination. Both capitalism and bureaucratic administration easily accommodated themselves to the new digital regime; both thrive on information flows, the more automated the better. Laws, markets, or technologies won’t stymie or redirect that demand for data, as all three play a role in sustaining capitalism and bureaucratic administration in the first place. Something else is needed: politics.

Even programs that seem innocuous can undermine democracy.

First, let’s address the symptoms of our current malaise. Yes, the commercial interests of technology companies and the policy interests of government agencies have converged: both are interested in the collection and rapid analysis of user data. Google and Facebook are compelled to collect ever more data to boost the effectiveness of the ads they sell. Government agencies need the same data—they can collect it either on their own or in coöperation with technology companies—to pursue their own programs.

Many of those programs deal with national security. But such data can be used in many other ways that also undermine privacy. The Italian government, for example, is using a tool called the redditometro, or income meter, which analyzes receipts and spending patterns to flag people who spend more than they claim in income as potential tax cheaters. Once mobile payments replace a large percentage of cash transactions—with Google and Facebook as intermediaries—the data collected by these companies will be indispensable to tax collectors. Likewise, legal academics are busy exploring how data mining can be used to craft contracts or wills tailored to the personalities, characteristics, and past behavior of individual citizens, boosting efficiency and reducing malpractice.

On another front, technocrats like Cass Sunstein, the former administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs at the White House and a leading proponent of “nanny statecraft” that nudges citizens to do certain things, hope that the collection and instant analysis of data about individuals can help solve problems like obesity, climate change, and drunk driving by steering our behavior. A new book by three British academics—Changing Behaviours: On the Rise of the Psychological State—features a long list of such schemes at work in the U.K., where the government’s nudging unit, inspired by Sunstein, has been so successful that it’s about to become a for-profit operation.

Thanks to smartphones or Google Glass, we can now be pinged whenever we are about to do something stupid, unhealthy, or unsound. We wouldn’t necessarily need to know why the action would be wrong: the system’s algorithms do the moral calculus on their own. Citizens take on the role of information machines that feed the techno-bureaucratic complex with our data. And why wouldn’t we, if we are promised slimmer waistlines, cleaner air, or longer (and safer) lives in return?

This logic of preëmption is not different from that of the NSA in its fight against terror: let’s prevent problems rather than deal with their consequences. Even if we tie the hands of the NSA—by some combination of better oversight, stricter rules on data access, or stronger and friendlier encryption technologies—the data hunger of other state institutions would remain. They will justify it. On issues like obesity or climate change—where the policy makers are quick to add that we are facing a ticking-bomb scenario—they will say a little deficit of democracy can go a long way.

Here’s what that deficit would look like: the new digital infrastructure, thriving as it does on real-time data contributed by citizens, allows the technocrats to take politics, with all its noise, friction, and discontent, out of the political process. It replaces the messy stuff of coalition-building, bargaining, and deliberation with the cleanliness and efficiency of data-powered administration.

This phenomenon has a meme-friendly name: “algorithmic regulation,” as Silicon Valley publisher Tim O’Reilly calls it. In essence, information-rich democracies have reached a point where they want to try to solve public problems without having to explain or justify themselves to citizens. Instead, they can simply appeal to our own self-interest—and they know enough about us to engineer a perfect, highly personalized, irresistible nudge.

Privacy is a means to democracy, not an end in itself.

Another warning from the past. The year was 1985, and Spiros Simitis, Germany’s leading privacy scholar and practitioner—at the time the data protection commissioner of the German state of Hesse—was addressing the University of Pennsylvania Law School. His lecture explored the very same issue that preoccupied Baran: the automation of data processing. But Simitis didn’t lose sight of the history of capitalism and democracy, so he saw technological changes in a far more ambiguous light.

He also recognized that privacy is not an end in itself. It’s a means of achieving a certain ideal of democratic politics, where citizens are trusted to be more than just self-contented suppliers of information to all-seeing and all-optimizing technocrats. “Where privacy is dismantled,” warned Simitis, “both the chance for personal assessment of the political … process and the opportunity to develop and maintain a particular style of life fade.”

Three technological trends underpinned Simitis’s analysis. First, he noted, even back then, every sphere of social interaction was mediated by information technology—he warned of “the intensive retrieval of personal data of virtually every employee, taxpayer, patient, bank customer, welfare recipient, or car driver.” As a result, privacy was no longer solely a problem of some unlucky fellow caught off-guard in an awkward situation; it had become everyone’s problem. Second, new technologies like smart cards and videotex not only were making it possible to “record and reconstruct individual activities in minute detail” but also were normalizing surveillance, weaving it into our everyday life. Third, the personal information recorded by these new technologies was allowing social institutions to enforce standards of behavior, triggering “long-term strategies of manipulation intended to mold and adjust individual conduct.”

Modern institutions certainly stood to gain from all this. Insurance companies could tailor cost-saving programs to the needs and demands of patients, hospitals, and the pharmaceutical industry. Police could use newly available databases and various “mobility profiles” to identify potential criminals and locate suspects. Welfare agencies could suddenly unearth fraudulent behavior.

But how would these technologies affect us as citizens—as subjects who participate in understanding and reforming the world around us, not just as consumers or customers who merely benefit from it?

In case after case, Simitis argued, we stood to lose. Instead of getting more context for decisions, we would get less; instead of seeing the logic driving our bureaucratic systems and making that logic more accurate and less Kafkaesque, we would get more confusion because decision making was becoming automated and no one knew how exactly the algorithms worked. We would perceive a murkier picture of what makes our social institutions work; despite the promise of greater personalization and empowerment, the interactive systems would provide only an illusion of more participation. As a result, “interactive systems … suggest individual activity where in fact no more than stereotyped reactions occur.”

If you think Simitis was describing a future that never came to pass, consider a recent paper on the transparency of automated prediction systems by Tal Zarsky, one of the world’s leading experts on the politics and ethics of data mining. He notes that “data mining might point to individuals and events, indicating elevated risk, without telling us why they were selected.” As it happens, the degree of interpretability is one of the most consequential policy decisions to be made in designing data-mining systems. Zarsky sees vast implications for democracy here:

A non-interpretable process might follow from a data-mining analysis which is not explainable in human language. Here, the software makes its selection decisions based upon multiple variables (even thousands) … It would be difficult for the government to provide a detailed response when asked why an individual was singled out to receive differentiated treatment by an automated recommendation system. The most the government could say is that this is what the algorithm found based on previous cases.

This is the future we are sleepwalking into. Everything seems to work, and things might even be getting better—it’s just that we don’t know exactly why or how.

Too little privacy can endanger democracy. But so can too much privacy.

Simitis got the trends right. Free from dubious assumptions about “the Internet age,” he arrived at an original but cautious defense of privacy as a vital feature of a self-critical democracy—not the democracy of some abstract political theory but the messy, noisy democracy we inhabit, with its never-ending contradictions. In particular, Simitis’s most crucial insight is that privacy can both support and undermine democracy.

Traditionally, our response to changes in automated information processing has been to view them as a personal problem for the affected individuals. A case in point is the seminal article “The Right to Privacy,” by Louis Brandeis and Samuel Warren. Writing in 1890, they sought a “right to be let alone”—to live an undisturbed life, away from intruders. According to Simitis, they expressed a desire, common to many self-made individuals at the time, “to enjoy, strictly for themselves and under conditions they determined, the fruits of their economic and social activity.”

A laudable goal: without extending such legal cover to entrepreneurs, modern American capitalism might have never become so robust. But this right, disconnected from any matching responsibilities, could also sanction an excessive level of withdrawal that shields us from the outside world and undermines the foundations of the very democratic regime that made the right possible. If all citizens were to fully exercise their right to privacy, society would be deprived of the transparent and readily available data that’s needed not only for the technocrats’ sake but—even more—so that citizens can evaluate issues, form opinions, and debate (and, occasionally, fire the technocrats).

This is not a problem specific to the right to privacy. For some contemporary thinkers, such as the French historian and philosopher Marcel Gauchet, democracies risk falling victim to their own success: having instituted a legal regime of rights that allow citizens to pursue their own private interests without any reference to what’s good for the public, they stand to exhaust the very resources that have allowed them to flourish.

When all citizens demand their rights but are unaware of their responsibilities, the political questions that have defined democratic life over centuries—How should we live together? What is in the public interest, and how do I balance my own interest with it?—are subsumed into legal, economic, or administrative domains. “The political” and “the public” no longer register as domains at all; laws, markets, and technologies displace debate and contestation as preferred, less messy solutions.

But a democracy without engaged citizens doesn’t sound much like a democracy—and might not survive as one. This was obvious to Thomas Jefferson, who, while wanting every citizen to be “a participator in the government of affairs,” also believed that civic participation involves a constant tension between public and private life. A society that believes, as Simitis put it, that the citizen’s access to information “ends where the bourgeois’ claim for privacy begins” won’t last as a well-functioning democracy.

Thus the balance between privacy and transparency is especially in need of adjustment in times of rapid technological change. That balance itself is a political issue par excellence, to be settled through public debate and always left open for negotiation. It can’t be settled once and for all by some combination of theories, markets, and technologies. As Simitis said: “Far from being considered a constitutive element of a democratic society, privacy appears as a tolerated contradiction, the implications of which must be continuously reconsidered.”

Laws and market mechanisms are insufficient solutions.

In the last few decades, as we began to generate more data, our institutions became addicted. If you withheld the data and severed the feedback loops, it’s not clear whether they could continue at all. We, as citizens, are caught in an odd position: our reason for disclosing the data is not that we feel deep concern for the public good. No, we release data out of self-interest, on Google or via self-tracking apps. We are too cheap not to use free services subsidized by advertising. Or we want to track our fitness and diet, and then we sell the data.

Simitis knew even in 1985 that this would inevitably lead to the “algorithmic regulation” taking shape today, as politics becomes “public administration” that runs on autopilot so that citizens can relax and enjoy themselves, only to be nudged, occasionally, whenever they are about to forget to buy broccoli.

Habits, activities, and preferences are compiled, registered, and retrieved to facilitate better adjustment, not to improve the individual’s capacity to act and to decide. Whatever the original incentive for computerization may have been, processing increasingly appears as the ideal means to adapt an individual to a predetermined, standardized behavior that aims at the highest possible degree of compliance with the model patient, consumer, taxpayer, employee, or citizen.

What Simitis is describing here is the construction of what I call “invisible barbed wire” around our intellectual and social lives. Big data, with its many interconnected databases that feed on information and algorithms of dubious provenance, imposes severe constraints on how we mature politically and socially. The German philosopher Jürgen Habermas was right to warn—in 1963—that “an exclusively technical civilization … is threatened … by the splitting of human beings into two classes—the social engineers and the inmates of closed social institutions.”

The invisible barbed wire of big data limits our lives to a space that might look quiet and enticing enough but is not of our own choosing and that we cannot rebuild or expand. The worst part is that we do not see it as such. Because we believe that we are free to go anywhere, the barbed wire remains invisible. Worse, there’s no one to blame: certainly not Google, Dick Cheney, or the NSA. It’s the result of many different logics and systems—of modern capitalism, of bureaucratic governance, of risk management—that get supercharged by the automation of information processing and by the depoliticization of politics.

The more information we reveal about ourselves, the denser but more invisible this barbed wire becomes. We gradually lose our capacity to reason and debate; we no longer understand why things happen to us.

But all is not lost. We could learn to perceive ourselves as trapped within this barbed wire and even cut through it. Privacy is the resource that allows us to do that and, should we be so lucky, even to plan our escape route.

This is where Simitis expressed a truly revolutionary insight that is lost in contemporary privacy debates: no progress can be achieved, he said, as long as privacy protection is “more or less equated with an individual’s right to decide when and which data are to be accessible.” The trap that many well-meaning privacy advocates fall into is thinking that if only they could provide the individual with more control over his or her data—through stronger laws or a robust property regime—then the invisible barbed wire would become visible and fray. It won’t—not if that data is eventually returned to the very institutions that are erecting the wire around us.

Think of privacy in ethical terms.

If we accept privacy as a problem of and for democracy, then popular fixes are inadequate. For example, in his book Who Owns the Future?, Jaron Lanier proposes that we disregard one pole of privacy—the legal one—and focus on the economic one instead. “Commercial rights are better suited for the multitude of quirky little situations that will come up in real life than new kinds of civil rights along the lines of digital privacy,” he writes. On this logic, by turning our data into an asset that we might sell, we accomplish two things. First, we can control who has access to it, and second, we can make up for some of the economic losses caused by the disruption of everything analog.

Lanier’s proposal is not original. In Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace (first published in 1999), Lawrence Lessig enthused about building a property regime around private data. Lessig wanted an “electronic butler” that could negotiate with websites: “The user sets her preferences once—specifies how she would negotiate privacy and what she is willing to give up—and from that moment on, when she enters a site, the site and her machine negotiate. Only if the machines can agree will the site be able to obtain her personal data.”

It’s easy to see where such reasoning could take us. We’d all have customized smartphone apps that would continually incorporate the latest information about the people we meet, the places we visit, and the information we possess in order to update the price of our personal data portfolio. It would be extremely dynamic: if you are walking by a fancy store selling jewelry, the store might be willing to pay more to know your spouse’s birthday than it is when you are sitting at home watching TV.

The property regime can, indeed, strengthen privacy: if consumers want a good return on their data portfolio, they need to ensure that their data is not already available elsewhere. Thus they either “rent” it the way Netflix rents movies or sell it on the condition that it can be used or resold only under tightly controlled conditions. Some companies already offer “data lockers” to facilitate such secure exchanges.

So if you want to defend the “right to privacy” for its own sake, turning data into a tradable asset could resolve your misgivings. The NSA would still get what it wanted; but if you’re worried that our private information has become too liquid and that we’ve lost control over its movements, a smart business model, coupled with a strong digital-rights-management regime, could fix that.

Meanwhile, government agencies committed to “nanny statecraft” would want this data as well. Perhaps they might pay a small fee or promise a tax credit for the privilege of nudging you later on—with the help of the data from your smartphone. Consumers win, entrepreneurs win, technocrats win. Privacy, in one way or another, is preserved also. So who, exactly, loses here? If you’ve read your Simitis, you know the answer: democracy does.

It’s not just because the invisible barbed wire would remain. We also should worry about the implications for justice and equality. For example, my decision to disclose personal information, even if I disclose it only to my insurance company, will inevitably have implications for other people, many of them less well off. People who say that tracking their fitness or location is merely an affirmative choice from which they can opt out have little knowledge of how institutions think. Once there are enough early adopters who self-track—and most of them are likely to gain something from it—those who refuse will no longer be seen as just quirky individuals exercising their autonomy. No, they will be considered deviants with something to hide. Their insurance will be more expensive. If we never lose sight of this fact, our decision to self-track won’t be as easy to reduce to pure economic self-interest; at some point, moral considerations might kick in. Do I really want to share my data and get a coupon I do not need if it means that someone else who is already working three jobs may ultimately have to pay more? Such moral concerns are rendered moot if we delegate decision-making to “electronic butlers.”

Few of us have had moral pangs about data-sharing schemes, but that could change. Before the environment became a global concern, few of us thought twice about taking public transport if we could drive. Before ethical consumption became a global concern, no one would have paid more for coffee that tasted the same but promised “fair trade.” Consider a cheap T-shirt you see in a store. It might be perfectly legal to buy it, but after decades of hard work by activist groups, a “Made in Bangladesh” label makes us think twice about doing so. Perhaps we fear that it was made by children or exploited adults. Or, having thought about it, maybe we actually do want to buy the T-shirt because we hope it might support the work of a child who would otherwise be forced into prostitution. What is the right thing to do here? We don’t know—so we do some research. Such scrutiny can’t apply to everything we buy, or we’d never leave the store. But exchanges of information—the oxygen of democratic life—should fall into the category of “Apply more thought, not less.” It’s not something to be delegated to an “electronic butler”—not if we don’t want to cleanse our life of its political dimension.

Sabotage the system. Provoke more questions.

We should also be troubled by the suggestion that we can reduce the privacy problem to the legal dimension. The question we’ve been asking for the last two decades—How can we make sure that we have more control over our personal information?—cannot be the only question to ask. Unless we learn and continuously relearn how automated information processing promotes and impedes democratic life, an answer to this question might prove worthless, especially if the democratic regime needed to implement whatever answer we come up with unravels in the meantime.

Intellectually, at least, it’s clear what needs to be done: we must confront the question not only in the economic and legal dimensions but also in a political one, linking the future of privacy with the future of democracy in a way that refuses to reduce privacy either to markets or to laws. What does this philosophical insight mean in practice?

First, we must politicize the debate about privacy and information sharing. Articulating the existence—and the profound political consequences—of the invisible barbed wire would be a good start. We must scrutinize data-intensive problem solving and expose its occasionally antidemocratic character. At times we should accept more risk, imperfection, improvisation, and inefficiency in the name of keeping the democratic spirit alive.

Second, we must learn how to sabotage the system—perhaps by refusing to self-track at all. If refusing to record our calorie intake or our whereabouts is the only way to get policy makers to address the structural causes of problems like obesity or climate change—and not just tinker with their symptoms through nudging—information boycotts might be justifiable. Refusing to make money off your own data might be as political an act as refusing to drive a car or eat meat. Privacy can then reëmerge as a political instrument for keeping the spirit of democracy alive: we want private spaces because we still believe in our ability to reflect on what ails the world and find a way to fix it, and we’d rather not surrender this capacity to algorithms and feedback loops.

Third, we need more provocative digital services. It’s not enough for a website to prompt us to decide who should see our data. Instead it should reawaken our own imaginations. Designed right, sites would not nudge citizens to either guard or share their private information but would reveal the hidden political dimensions to various acts of information sharing. We don’t want an electronic butler—we want an electronic provocateur. Instead of yet another app that could tell us how much money we can save by monitoring our exercise routine, we need an app that can tell us how many people are likely to lose health insurance if the insurance industry has as much data as the NSA, most of it contributed by consumers like us. Eventually we might discern such dimensions on our own, without any technological prompts.

Finally, we have to abandon fixed preconceptions about how our digital services work and interconnect. Otherwise, we’ll fall victim to the same logic that has constrained the imagination of so many well-meaning privacy advocates who think that defending the “right to privacy”—not fighting to preserve democracy—is what should drive public policy. While many Internet activists would surely argue otherwise, what happens to the Internet is of only secondary importance. Just as with privacy, it’s the fate of democracy itself that should be our primary goal.

After all, back in 1967 Paul Baran was lucky enough not to know what the Internet would become. That didn’t stop him from seeing the benefits of utility computing and its dangers. Abandon the idea that the Internet fell from grace over the last decade. Liberating ourselves from that misreading of history could help us address the antidemocratic threats of the digital future.

Evgeny Morozov is the author of The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom and To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism.

Monday, August 12. 2013

Via ericsadin.org via Le Monde

-----

Following all these recent posts aboutths nsa, algorithms, surveillance/monitoring, etc., I take here the opportunity to reblog what our very good friend Eric Sadin published in Le Monde last month about this question (the article is only in French, it was following the publication of a new book by Eric: L'humanité augmentée - L'administration numérique du monde -, éd. L'échapée). It is also the occasion to remind that we did a work in common about this last year, Globale surveillance, that will be on stage again later this year!

Le 5 juin, Glenn Greenwald, chroniqueur au quotidien britannique The Guardian, révèle sur son blog que l'Agence de sécurité nationale (NSA) américaine bénéficie d'un accès illimité aux données de Verizon, un des principaux opérateurs téléphoniques et fournisseurs d'accès Internet américains. La copie de la décision de justice confidentielle est publiée, attestant de l'obligation imposée à l'entreprise de fournir les relevés détaillés des appels de ses abonnés. "Ce document démontre pour la première fois que, sous l'administration Obama, les données de communication de millions de citoyens sont collectées sans distinction et en masse, qu'ils soient ou non suspects", commente-t-il sur la même page.

Dès le lendemain, Glenn Greenwald relate dans un article cosigné avec un journaliste du Guardian d'autres faits décisifs : neuf des plus grands acteurs américains d'Internet (Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Apple, Yahoo, AOL, YouTube, Skype et PalTalk) permettraient au FBI (la police fédérale) et à la NSA d'avoir directement accès aux données de leurs utilisateurs, par le biais d'un système hautement sophistiqué baptisé "Prism", dont l'usage régulier serait à l'oeuvre depuis 2007. Informations confidentielles à l'origine livrées par Edward

Snowden, jeune informaticien ex-employé de l'Agence centrale du renseignement (CIA), officiant pour différents sous-traitants de la NSA. Le "lanceur d'alerte" affirme que de telles pratiques mettent en péril la vie privée, engageant en toute conscience son devoir de citoyen de les divulguer, malgré les risques de poursuites encourues. Les entreprises incriminées ont aussitôt démenti cette version, laissant néanmoins supposer que des négociations sont en cours en vue de créer un cadre coopératif "viable" élaboré d'un commun accord.

Divulgations qui ont aussitôt suscité un afflux de commentaires de tous ordres, relatifs à l'ampleur des informations interceptées par les agences de renseignement, autant qu'à l'impérieuse nécessité de préserver les libertés individuelles.

S'il demeure de nombreuses zones d'ombre et des incertitudes quant aux procédés employés et à l'implication de chacun des acteurs, ces affaires confirment manifestement, aux yeux du monde, qu'un des enjeux cruciaux actuels renvoie à l'épineuse question de la récolte et de l'usage des données à caractère personnel. Ces événements, s'ils sont confirmés dans leur version initiale, sont éminemment répréhensibles, néanmoins, pour ma part, je ne veux y voir qu'une forme de "banalité de la surveillance contemporaine", qui dans les faits se déploie à tout instant, en tout lieu et sous diverses formes, la plupart du temps favorisée par notre propre consentement.

Car ce qui se joue ici ne relève pas de faits isolés, principalement "localisés" aux Etats-Unis et conduits par de seules instances gouvernementales, dont il faudrait s'offusquer au rythme des révélations successives. C'est dans leur valeur symptomale qu'ils doivent être saisis, en tant qu'exemples de phénomènes aujourd'hui globalisés, rendus possibles par la conjonction de trois facteurs hétérogènes et concomitants. Sorte de "bouillon de culture" qui se serait formé vers le début de la première décennie du XXIe siècle, et qui a "autorisé" l'extension sans cesse croissante de procédures de surveillance, suivant une ampleur et une profondeur sans commune mesure historique.

D'abord, c'est l'expansion ininterrompue du numérique depuis le début des années 1980, plus tard croisée aux réseaux de télécommunication, qui a rendu possible vers le milieu des années 1990 la généralisation d'Internet, soit l'interconnexion globalisée en temps réel.

Ensuite, l'intensification de la concurrence économique a encouragé l'instauration de stratégies marketing agressives, cherchant à capter et à pénétrer toujours plus profondément les comportements des consommateurs, un objectif facilité par la dissémination croissante de données grâce au suivi des navigations, ou autres achats par cartes de crédit ou de fidélisation.

Enfin, les événements du 11 septembre 2001 ont contribué à amplifier un profilage sécuritaire indifférencié du plus grand nombre d'individus possible. Ce qui est désormais nommé " Big Data ", soit la profusion de données disséminées par les corps et les choses, se substitue en quelque sorte à la figure unique et omnipotente de Big Brother, en une fragmentation éparpillée de serveurs et d'organismes, qui concourent ensemble et séparément à affiner la connaissance des personnes, en vue d'une multiplicité de fonctionnalités à exploitations prioritairement sécuritaires ou commerciales.

Le lien charnel, tactile ou quasi ombilical que nous entretenons avec nos prothèses numériques miniaturisées - particulièrement emblématique dans le smartphone - bouleverse les conditions historiques de l'expérience humaine. La géolocalisation intégrée aux dispositifs transforme ou "élargit" notre appréhension sensorielle de l'espace ; la portabilité expose une forme d'ubiquité induisant une perception de la durée au rythme de la vitesse des flux électroniques reçus et transmis ; les applications traitent des magmas d'informations à des vitesses infiniment supérieures à celles de nos capacités cérébrales, et sont dotées de miraculeux pouvoirs cognitifs et suggestifs, qui peu à peu infléchissent la courbe de nos quotidiens.

C'est un nouveau mode d'intelligibilité du réel qui s'est peu à peu constitué, fondé sur une transparence généralisée, qui réduit la part de vide séparant les êtres entre eux et les êtres aux choses. "Tournant numérico-cognitif" engendré par l'intelligence croissante acquise par la technique, capable d'évaluer les situations, d'alerter, de suggérer et de prendre dorénavant des décisions à notre place (à l'instar du récent prototype de la Google Car, ou du trading à haute fréquence).

Le mouvement généralisé de numérisation du monde, dont Google constitue le levier principal, vise à instaurer une "rationalisation algorithmique de l'existence", à redoubler le réel logé au sein de "fermes de serveurs" hautement sécurisées, en vue de le quantifier et de l'orienter en continu à des fins d'"optimisation" sécuritaire, commerciale, thérapeutique ou relationnelle. C'est une rupture anthropologique qui actuellement se trame par le fait de notre condition de toute part interconnectée et robotiquement assistée, qui s'est déployée avec une telle rapidité qu'elle nous a empêchés d'en saisir la portée civilisationnelle.

Les récentes révélations mettent en lumière un enjeu crucial de notre temps, auquel nos sociétés dans leur ensemble doivent se confronter activement, devant engager à mon sens trois impératifs éthiques catégoriques. Le premier consiste à élaborer des lois viables à échelles nationale et internationale, visant à marquer des limites, et à rendre autant que possible transparents les processus à l'oeuvre, souvent dérobés à notre perception.

Dimensions complexes dans la mesure où les développements techniques et les logiques économiques se déploient suivant des vitesses qui dépassent celle de la délibération démocratique, et ensuite parce que les rapports de force géopolitiques tendent à ralentir ou à freiner toute velléité d'harmonisation transnationale (voir à ce sujet la récente offensive de lobbying américain cherchant à contrarier ou à empêcher la mise en place d'un projet visant à améliorer la protection des données personnelles des Européens : The Data Protection Regulation - DPR - ).

Le deuxième requiert un devoir d'enseignement et d'apprentissage des disciplines informatiques à l'école et à l'université, visant à faire comprendre "de l'intérieur" les fonctionnements complexes du code, des algorithmes et des systèmes. Disposition susceptible de positionner chaque citoyen comme un artisan actif de sa vie numérique, à l'instar de certains hackeurs qui en appellent à comprendre les processus à l'oeuvre, à se réapproprier les dispositifs ou à en inventer de singuliers, en vue d'usages "libres" et partagés en toute connaissance des choses.

Le troisième mobilise l'enjeu capital visant à maintenir une forme de "veille mutualisée" à l'égard des protocoles et de nos pratiques, grâce à des initiatives citoyennes s'emparant sous de multiples formes de ces questions, afin de les exposer dans le domaine public au fur et à mesure des évolutions et innovations successives. Nous devons espérer que l'admirable courage d'Edward Snowden ou la remarquable ténacité de Glenn Greenwald soient annonciateurs d'un "printemps globalisé", appelé à faire fleurir de toute part et pour le meilleur les champs de nos consciences individuelles et collectives.

Citons les propos énoncés par Barack Obama lors de sa conférence de presse du 7 juin : "Je pense qu'il est important de reconnaître que vous ne pouvez pas avoir 100 % de sécurité, mais aussi 100 % de respect de la vie privée et zéro inconvénient. Vous savez, nous allons devoir faire des choix de société." Dont acte, et sans plus tarder.

A l'aune de l'incorporation annoncée de puces électroniques à l'intérieur de nos tissus biologiques, qui témoignerait alors sans rupture spatio-temporelle de l'intégralité de nos gestes et de la nature de nos relations, la mise en place d'un "Habeas corpus numérique" relève à coup sûr d'un enjeu civilisationnel majeur de notre temps.

Eric Sadin

© Le Monde

Friday, July 26. 2013

Via Digital Trends

-----

By Kate Knibbs

Facebook leaking user information, a dust-up over Facebook shadow profiles has relaunched. A “shadow profile” sounds like something a CIA operative would have – but if you’re a Facebook user, you have a shadow profile, whether you’re a real-life James Bond or just an accountant from Des Moines.

So what is a Facebook shadow profile, and where does yours lurk?

A Facebook shadow profile is a file that Facebook keeps on you containing data it pulls up from looking at the information that a user’s friends voluntarily provide. You’re not supposed to see it, or even know it exists. This collection of information can include phone numbers, e-mail addresses, and other pertinent data about a user that they don’t necessarily put on their public profile. Even if you never gave Facebook your second email address or your home phone number, they may still have it on file, since anyone who uses the “Find My Friends” feature allows Facebook to scan their contacts. So if your friend has your contact info on her phone and uses that feature, Facebook can match your name to that information and add it to your file.

“When people use Facebook, they may store and share information about you.”

Facebook recently announced that it fixed a bug that inadvertently revealed this hidden contact information for six million users. Their mea culpa was not particularly well-received, since this security breach revealed that the social network had been collecting this data on all of its users and compiling it into shadow profiles for years. Some people who use Facebook’s Download Your Information (DYI) tool could see the dossiers Facebook had been collecting as well as information their friends put up themselves. So, if I downloaded my information and was affected by the bug, I’d see some of the email addresses and phone numbers of my friends who did not make that information public.

Although Facebook corrected the bug, it hasn’t stopped this program of accumulating extra information on people. And researchers looking at the numbers say the breach is actually more involved than Facebook initially claimed, with four pieces of data released for a user that Facebook said had one piece of data leaked.

This snafu won’t come as a surprise to researchers who brought up Facebook’s shadow profiles long before this most recent breach. In 2011, an Irish advocacy group filed a complaint against Facebook for collecting information like email addresses, phone numbers, work details, and other data to create shadow profiles for people who don’t use the service. Since it actually takes moral fortitude to resist the social pull of Facebook, this is a slap in the face for people who make a point to stay off the network: The group claimed that Facebook still has profiles for non-Facebookers anyway.

Though the decision to publicly own up to the bug was a step in the right direction, this leak is disturbing because it illustrates just how little control we have over our data when we use services like Facebook. And it illustrates that Facebook isn’t apologizing for collecting information – it’s just apologizing for the bug. The shadow profile will live another day.

Most people understand that Facebook can see, archive, and data-mine the details you voluntarily put up on the site. The reason people are disturbed by shadow profiles is the information was collected in a roundabout way, and users had no control over what was collected (which is how even people who abstain from Facebook may have ended up with dossiers despite their reluctance to get involved with the site). Now we don’t just need to worry about what we choose to share; we also have to worry that the friends we trust with personal information will use programs that collect our data.

To Facebook’s credit, they do make this clear in the privacy policy, it’s just that no one bothers to read it:

“We receive information about you from your friends and others, such as when they upload your contact information, post a photo of you, tag you in a photo or status update, or at a location, or add you to a group. When people use Facebook, they may store and share information about you and others that they have, such as when they upload and manage their invites and contacts.”

Now, the Facebook shadow profiles contain information that many people make public anyways; plenty of people have made their phone numbers and addresses discoverable via a simple Google Search (not that they should, but that’s another story). But if you make a point to keep that kind of information private, this shadow profile business will sting. And even if you don’t mind the fact that Facebook creeped on your phone number via your friends, you should be concerned that next time these shadow profiles make it into the news, it will be over other data-mining that could be potential harmful. Imagine if your credit card information or PIN number ended up going public.

The way Facebook worded its apology is interesting because it doesn’t say that they don’t collect that type of information.

“Additionally, no other types of personal or financial information were included and only people on Facebook – not developers or advertisers – have access to the DYI tool.”

The fact that they said “were included” instead of “were collected” leaves open the possibility that Facebook does have this kind of information on file – it just wasn’t part of this particular mix-up.

Facebook hasn’t reassured users by saying they don’t collect this kind of data, and that’s awfully suspicious; if their shadow data collection was really limited to phone numbers and email addresses, your would think they would’ve explicitly said so, to ameliorate critics. What Facebook isn’t saying here versus what they are saying speaks volumes. The site is sorry for the bug, but not sorry for surreptitiously collecting data on you. And they’re admitting the data that was released in the bug, but not explaining the exact scope of the shadow profile amalgamation.

Facebook’s shadow profiles aren’t uniquely or especially nefarious, but this incident makes it all the more obvious that the amount of data companies are collecting on you far surpasses what you might suspect. And unless there are legislative changes, this will continue unabated.

Personal comment:

To read also another article by MIT Tech Review: "What Facebook Knows"

Thursday, July 25. 2013

Via MIT Technology Review via @chrstphggnrd

-----

New tricks will enable a life-logging app called Saga to figure out not only where you are, but what you’re doing.

By Tom Simonite

Having mobile devices closely monitoring our behavior could make them more useful, and open up new business opportunities.

Many of us already record the places we go and things we do by using our smartphone to diligently snap photos and videos, and to update social media accounts. A company called ARO is building technology that automatically collects a more comprehensive, automatic record of your life.

ARO is behind an app called Saga that automatically records every place that a person goes. Now ARO’s engineers are testing ways to use the barometer, cameras, and microphones in a device, along with a phone’s location sensors, to figure out where someone is and what they are up to. That approach should debut in the Saga app in late summer or early fall.

The current version of Saga, available for Apple and Android phones, automatically logs the places a person visits; it can also collect data on daily activity from other services, including the exercise-tracking apps FitBit and RunKeeper, and can pull in updates from social media accounts like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Once the app has been running on a person’s phone for a little while, it produces infographics about his or her life; for example, charting the variation in times when they leave for work in the morning.

Software running on ARO’s servers creates and maintains a model of each user’s typical movements. Those models power Saga’s life-summarizing features, and help the app to track a person all day without requiring sensors to be always on, which would burn too much battery life.

“If I know that you’re going to be sitting at work for nine hours, we can power down our collection policy to draw as little power as possible,” says Andy Hickl, CEO of ARO. Saga will wake up and check a person’s location if, for example, a phone’s accelerometer suggests he or she is on the move; and there may be confirmation from other clues, such as the mix of Wi-Fi networks in range of the phone. Hickl says that Saga typically consumes around 1 percent of a device’s battery, significantly less than many popular apps for e-mail, mapping, or social networking.

That consumption is low enough, says Hickl, that Saga can afford to ramp up the information it collects by accessing additional phone sensors. He says that occasionally sampling data from a phone’s barometer, cameras, and microphones will enable logging of details like when a person walked into a conference room for a meeting, or when they visit Starbucks, either alone or with company.

The Android version of Saga recently began using the barometer present in many smartphones to distinguish locations close to one another. “Pressure changes can be used to better distinguish similar places,” says Ian Clifton, who leads development of the Android version of ARO. “That might be first floor versus third floor in the same building, but also inside a vehicle versus outside it, even in the same physical space.”

ARO is internally testing versions of Saga that sample light and sound from a person’s environment. Clifton says that using a phone’s microphone to collect short acoustic fingerprints of different places can be a valuable additional signal of location, and allow inferences about what a person is doing. “Sometimes we’re not sure if you’re in Starbucks or the bar next door,” says Clifton. “With acoustic fingerprints, even if the [location] sensor readings are similar, we can distinguish that.”

Occasionally sampling the light around a phone using its camera provides another kind of extra signal of a person’s activity. “If you go from ambient light to natural light, that would say to us your context has changed,” says Hickl, and it should be possible for Saga to learn the difference between, say, the different areas of an office.

The end result of sampling light, sound, and pressure data will be Saga’s machine learning models being able to fill in more details of a users’ life, says Hickl. “[When] I go home today and spend 12 hours there, to Saga that looks like a wall of nothing,” he says, noting that Saga could use sound or light cues to infer when during that time at home he was, say, watching TV, playing with his kids, or eating dinner.

Andrew Campbell, who leads research into smartphone sensing at Dartmouth College, says that adding more detailed, automatic life-logging features is crucial for Saga or any similar app to have a widespread impact. “Automatic sensing relieves the user of the burden of inputting lots of data,” he says. “Automatic and continuous sensing apps that minimize user interaction are likely to win out.”

Campbell says that automatic logging coupled with machine learning should allow apps to learn more about users’ health and welfare, too. He recently started analyzing data from a trial in which 60 students used a life-logging app that Campbell developed called Biorhythm. It uses various data collection tricks, including listening for nearby voices to determine when a student is in a conversation. “We can see many interesting patterns related to class performance, personality, stress, sociability, and health,” says Campbell. “This could translate into any workplace performance situation, such as a startup, hospital, large company, or the home.”

Campbell’s project may shape how he runs his courses, but it doesn’t have to make money. ARO, funded by Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen, ultimately needs to make life-logging pay. Hickl says that he has already begun to rent out some of ARO’s technology to other companies that want to be able to identify their users’ location or activities. Aggregate data from Saga users should also be valuable, he says.

“Now we’re getting a critical mass of users in some areas and we’re able to do some trend-spotting,” he says. “The U.S. national soccer team was in Seattle, and we were able to see where activity was heating up around the city.” Hickl says the data from that event could help city authorities or businesses plan for future soccer events in Seattle or elsewhere. He adds that Saga could provide similar insights into many other otherwise invisible patterns of daily life.

Personal comment:

Or how to build up knowledge and minable data from low end "sensors". Finally, how some trivial inputs from low cost sensors can, combined with others, reveal deeper patterns in our everyday habits.

But who's Aro? Who founded it? Who are the "business angels" behind it and what are they up to? What does the technology exactly do? Where are its legal headquarters located (under which law)? That's the first questions you should ask yourself before eventually giving your data to a private company... (I know, this is usual suspects these days). But that's pretty hard to find! CEO is Mr Andy Hickl based in Seattle, having 1096 followers on Twitter and a "Sorry, this page isn't available" on Facebook, you can start to digg from there and mine for him on Google...

-

We are in need of some sort of efficient Creative Commons equivalent for data. But that would be respected by companies. As well as some open source equivalent for Facebook, Google, Dropbox, etc. (but also MS, Apple, etc.), located in countries that support these efforts through their laws and where these "Creative Commons" profiles and data would be implemented. Then, at least, we would have some choice.

In Switzerland, we had a term to describe how the landscape has been progressivily used since the 60ies to build small individual or holiday houses: "mitage du territoire" ("urban sprawl" sounds to be the equivalent in english, but "mitage" is related to "moths" to be precise, so rather ""mothed" landscape" if I could say so, which says what it says) and we had the opportunity to vote against it recently, with success. I believe that now the same thing is happening with personal and/or public sphere, with our lives: it is sprawled or "mothed" by private interests.

So, it is time to ask for the opportunity to "vote" (against it) everybody and have the choice between keeping the ownership of your data, releasing them as public or being paid for them (like a share in the company('s product))!

Monday, January 09. 2012

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

New system detects emotions based on variables ranging from typing speeds to the weather.

By Duncan Graham-Rowe

Researchers at Samsung have developed a smart phone that can detect people's emotions. Rather than relying on specialized sensors or cameras, the phone infers a user's emotional state based on how he's using the phone.

For example, it monitors certain inputs, such as the speed at which a user types, how often the "backspace" or "special symbol" buttons are pressed, and how much the device shakes. These measures let the phone postulate whether the user is happy, sad, surprised, fearful, angry, or disgusted, says Hosub Lee, a researcher with Samsung Electronics and the Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology's Intelligence Group, in South Korea. Lee led the work on the new system. He says that such inputs may seem to have little to do with emotions, but there are subtle correlations between these behaviors and one's mental state, which the software's machine-learning algorithms can detect with an accuracy of 67.5 percent.

The prototype system, to be presented in Las Vegas next week at the Consumer Communications and Networking Conference, is designed to work as part of a Twitter client on an Android-based Samsung Galaxy S II. It enables people in a social network to view symbols alongside tweets that indicate that person's emotional state. But there are many more potential applications, says Lee. The system could trigger different ringtones on a phone to convey the caller's emotional state or cheer up someone who's feeling low. "The smart phone might show a funny cartoon to make the user feel better," he says.

Further down the line, this sort of emotion detection is likely to have a broader appeal, says Lee. "Emotion recognition technology will be an entry point for elaborate context-aware systems for future consumer electronics devices or services," he says. "If we know the emotion of each user, we can provide more personalized services."

Samsung's system has to be trained to work with each individual user. During this stage, whenever the user tweets something, the system records a number of easily obtained variables, including actions that might reflect the user's emotional state, as well as contextual cues, such as the weather or lighting conditions, that can affect mood, says Lee. The subject also records his or her emotion at the time of each tweet. This is all fed into a type of probabilistic machine-learning algorithm known as a Bayesian network, which analyzes the data to identify correlations between different emotions and the user's behavior and context.

The accuracy is still pretty low, says Lee, but then the technology is still at a very early experimental stage, and has only been tested using inputs from a single user. Samsung won't say whether it plans to commercialize this technology, but Lee says that with more training data, the process can be greatly improved. "Through this, we will be able to discover new features related to emotional states of users or ways to predict other affective phenomena like mood, personality, or attitude of users," he says.

Reading emotion indirectly through normal cell phone use and context is a novel approach, and, despite the low accuracy, one worth pursuing, says Rosalind Picard, founder and director of MIT's Affective Computing Research Group, and cofounder of Affectiva, which last year launched a commercial product to detect human emotions. "There is a huge growing market for technology that can help businesses show higher respect for customer feelings," she says. "Recognizing when the customer is interested or bored, stressed, confused, or delighted is a vital first step for treating customers with respect," she says.

Copyright Technology Review 2012.

Personal comment:

While we can doubt a little about the accuracy of so few inputs to determine someone's emotions, context aware (a step further from "geography" aware) devices seems a way to go for technology manufacturers.

Transposed into the field of environement design and architecture (sensors, probes) it could lead to some designs where there is a sort of collaboration between the environment and it's users (participants? ecology of co-evolutive functions?). We mentioned this in a previous post (The measured life): "could we think of a data based architecture (open data from health and Real Life monitoring --in addition to environmental sensors and online data--) that would collaborate with those health inputs?" and now with those emotional inputs? A sensitive environment?

We worked on something related a few years ago within the frame of a research project between EPFL (Swiss Institute of Technology, Lausanne) and ECAL (University of Art and Design, Lausanne), it was rather a robotized proof of concept at a small scale than a full environment though: The Rolling Microfunctions. The idea in this case was not that "function follows context", but rather that "function understand context and triggers open/sometimes disruptive patterns of usage, base on algorithmic and semi-autonomous rules"... Functions as a creative environment. Sort of... The result was a bit disapointing of course, but it was the idea behind it that we thought was interesting.

And of course, all these projects should be backed up by a very rigourous policy about user's, function's and space's data: they belong either to the user (privacy), to the public (open data) or why not, to the space..., but not to a company (googlacy, facebookacy, twitteracy, etc.) unless the space belong's to them, like in a shop (see "La ville franchisée", by David Mangin) .

Monday, May 23. 2011

Via OWNI.eu

-----

What do Pandora for music, Zite for news, or Amazon for shopping — along with many Silicon Valley startups I’m meeting these days — have in common?

• They are all offering the user a personalized experience by leveraging his/her social network.

• They also provide a social experience in line with every single user’s personal taste and identity.

Overall, there’s an increasing focus on the person and his/her environment versus the simple social media aspect.

These are only the premises of what I would call the persocial web — a new generation of digital products and services where personal and social dimensions melt together to put every person at the center of the game. The consequences of this trend will be extremely broad for the way we approach the Internet both from a sociological and business viewpoint.

A Socratic revolution

A similar kind of re-focus on the individual is physiological for humanity. It happened in the history of philosophy too, when Socrates put the man at the center of his intellectual quest after decades of philosophical thinking about nature, environment and physics.

In general, the fluctuation between holistic and individualistic eras is also very familiar to the history of ideas. Think about what happened in Europe from the 18th century to the 19th and beyond with the Age of Enlightment, followed by the Romantic Era and then by the Naturalistic movement. It’s just a dialectic and continuous evolution.

From the PC to the Social Media era. And beyond.

While these movements embrace more than one hundred years, my generation has already lived many of these ‘eras’ thanks to the time acceleration provided by information technologies.

The personal computer represents for people like me who are in their 30s the very first approach with computer technology. It was a very personal and sometimes solitary experience of writing and gaming. It was all about you. Well, you, the machine and the rest (games, floppy disks, your docs, etc).

Then the Internet came. First, we felt extremely powerless. We could interconnect and learn in the ‘cyberspace’ thanks to email, portals and chats. But we felt disoriented, until the point when Google figured out a way to have the individual navigating easily through all the amount of data, services and content that were out there in a more effective way than portals or email could do. But even at that stage, we lived in a personal web era. It was all about you, your Web browser and the rest. Beyond bi-lateral exchanges, multi-lateral interactions were difficult and sporadic.

Then Facebook disrupted that paradigm by creating a lasting and robust environment for sharing data and nurturing relationships. Our social life was, and is mirrored — sometimes diminished, sometimes augmented — on Facebook. It’s all about you, your social network and the rest.

I believe the next paradigm that is being formed today is going to envision the individual as the real center of a social environment (Facebook). Digital services and products will increasingly ‘talk’ to the individual in a personal way, by guessing his/her tastes and preferences in an intimate and closer relationship. Borrowing an expression from one of my professors at Stanford, Clifford Nass, they will become “adaptive and personalized systems“.

Leveraging what your social network (Facebook) or other random people (Amazon) do, read or buy to generate an experience that is more relevant to you is good. But designing a whole persocial experience is even better. That means taking into account countless personal data: sex, location, age, education, political and religious views, cultural tastes, all sort of affiliations, groups etc. and melting them with your social graph to offer a better user experience.

Facebook OpenGraph or Twitter API already enable such a personalization but its implementation has been so far more focused on real time and very much instant data (the feed of articles that my friends or people I follow read) than on more long-run information about my tastes (taking into account who I actually am, my background, sex, location etc.).

Towards a persocial news experience?

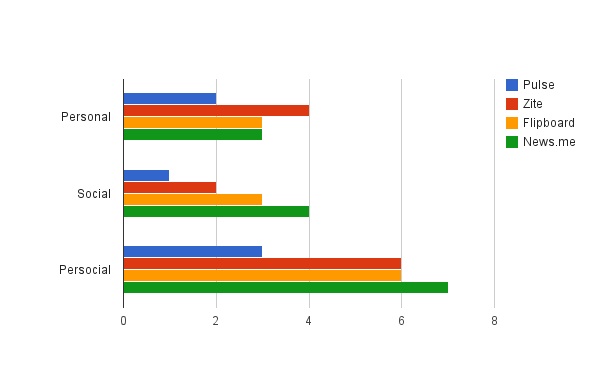

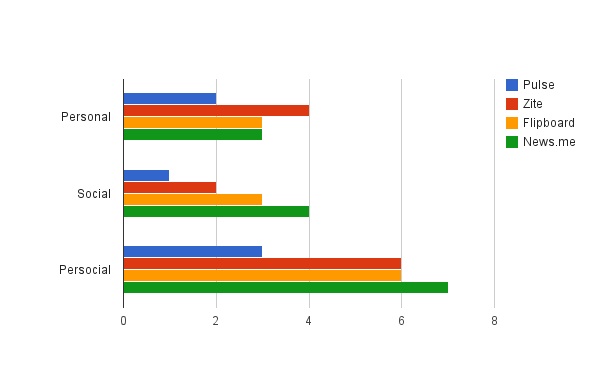

In the news industry, for instance, many are the news readers that are offering to improve the news experience by persocializing it. I tried to rate them by their personalization (1 to 5 points) and socialization (1 to 5 points) effort.

Thanks to its great feature on ‘what my friends are reading,’ News.me, developed by Betaworks and The New York Times, is so far the more persocial news reader, and also the only paid app among the ones we’re analyzing here. In reality, it offers a more social than personal experience. The best personalized features are so far provided by Zite, a Canadian news reader for the iPad, which recently received a ‘cease or desist’ letter from several U.S. publishers. While Flipboard is a fair trade-off in terms of persocialization, Pulse, conceived by smart Stanford students, is intentionally closer to a traditional and yet very clean news reader experience.

Overall, an iPad app that would combine the social features of News.me with the personalization of Zite, would probably be fully persocial.

In general, these new ventures are all part of an overall phenomenon that will reshape the way we consume and engage with web products and services. New privacy issues will raise of course but overall, thanks to persocialization, the web user will become a person again.

—

Photo Credits: Flicke CC Johan Larsson

Thursday, February 09. 2006

|