Sticky Postings

All 242 fabric | rblg updated tags | #fabric|ch #wandering #reading

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Monday, February 20. 2017

The Ulm Model: a school and its pursuit of a critical design practice | #design #teaching

Via It's Nice That

-----

Words by Billie Muraben, photography by Connor Campbell

“My feeling is that the Bauhaus being conveniently located before the Second World War makes it safely historical,” says Dr. Peter Kapos. “Its objects have an antique character that is about as threatening as Arts and Crafts, whereas the problem with the Ulm School is that it’s too relevant. The questions raised about industrial design [still apply], and its project failed – its social project being particularly disappointing – which leaves awkward questions about where we are in the present.”

Kapos discovered the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm, or Ulm School, through his research into the German manufacturing company Braun, the representation of which is a specialism of his archive, das programm. The industrial design school had developed out of a community college founded by educationalist Inge Scholl and graphic designer Otl Aicher in 1946. It was established, as Kapos writes in the book accompanying the Raven Row exhibition, The Ulm Model, “with the express purpose of curbing what nationalistic and militaristic tendencies still remained [in post-war Germany], and making a progressive contribution to the reconstruction of German social life.”

The Ulm School closed in 1968, having undergone various forms of pedagogy and leadership, crises in structure and personality. Nor the faculty or student-body found resolution to the problems inherent to industrial design’s claim to social legitimacy – “how the designer could be thoroughly integrated within the production process at an operational level and at the same time adopt a critically reflective position on the social process of production.” But while the Ulm School and the Ulm Model collapsed, it remains an important resource, “it’s useful, even if the project can’t be restarted, because it was never going to succeed, the attempt is something worth recovering. Particularly today, under very difficult conditions.”

Foundation Course exercise

Student: Hans von Klier

Instructor: Helene Nonné-Schmidt 1955

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise

Student: Bertus Mulder

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise

Student: M. Buch

Instructor: Tomás Maldonado

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Max Bill, a graduate of the Bauhaus and then president of the Swiss Werkbund, arrived at Ulm in 1950, having been recruited partly in the hope that his international profile would attract badly needed funding. He tightened the previously broad curriculum, established by Marxist writer Hans Werner Richter, around design, mirroring the practices of his alma mater.

Bill’s rectorship ran from 1955-58, during which “there was no tension between the way he designed and the requirements of the market”. The principle of the designer as artist, a popular notion of the Bauhaus, curbed the “alienating nature of industrial production”. Due perhaps in part to the trauma of WW2, people hadn’t been ready to allow technology into the home that declared itself as technology.

“The result of that was record players and radios smuggled into the home, hidden in what looked like other pieces of furniture, with walnut veneers and golden tassels.” Bill’s way of thinking didn’t necessarily reflect the aesthetic, but it wasn’t at all challenging politically. “So in some ways that’s really straight-forward and unproblematic – and he’s a fantastic designer, an extraordinary architect, an amazing graphic designer, and a great artist – but he wasn’t radical enough. What he was trying to do with industrial design wasn’t taking up the challenge.”

Foundation Course exercise

Student: John Lottes

Instructor: Anthony Frøshaug

1958-59

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

In 1958 Bill stepped down having failed to “grasp the reality of industrial production simply at a technical and operational level… [or] recognise its emancipatory potential.” The industrial process had grown in complexity, and the prospect of rebuilding socially was too vast for single individuals to manage. It was no longer possible for the artist-designer to sit outside of the production process, because the new requirements were so complex. “You had to be absolutely within the process, and there had to be a team of disciplinary specialists — not only of material, but circulation and consumption, which was also partly sociological. It was a different way of thinking about form and its relation to product.”

After Bill’s departure, Tomás Maldonado, an instructor at the school, “set out the implications for a design education adequate to the realities of professional practice.” Changes were made to the curriculum that reflected a critically reflective design practice, which he referred to as ‘scientific operationalism’ and subjects such as ‘the instruction of colour’, were dropped. Between 1960-62, the Ulm Model was introduced: “a novel form of design pedagogy that combined formal, theoretical and practical instruction with work in so-called ‘Development Groups’ for industrial clients under the direction of lecturers.” And it was during this period that the issue of industrial design’s problematic relationship to industry came to a head.

“You had to be absolutely within the process, and there had to be a team of disciplinary specialists – not only of material, but circulation and consumption, which was also partly sociological. It was a different way of thinking about form and its relation to product.”

– Peter Kapos

In 1959, a year prior to the Ulm Model’s formal introduction, Herbert Lindinger, a student from a Development Group working with Braun, designed an audio system. A set of transistor equipment, it made no apologies for its technology, and looked like a piece of engineering. His audio system became the model for Braun’s 1960s audio programme, “but Lindinger didn’t receive any credit for it, and Braun’s most successful designs from the period derived from an implementation of his project. It’s sad for him but it’s also sad for Ulm design because this had been a collective project.”

The history of the Braun audio programme was written as being defined by Dieter Rams, “a single individual — he’s an important designer, and a very good manager of people, he kept the language consistent — but Braun design of the 60s is not a manifestation of his genius, or his vision.” And the project became an indication of why the Ulm project would ultimately fail, “when recalling it, you end up with a singular genius expressing the marvel of their mind, rather than something that was actually a collective project to achieve something social.”

An advantage of Bill’s teaching model had been the space outside of the industrial process, “which is the space that offers the possibility of criticality. Not that he exercised it. But by relinquishing that space, [the Ulm School] ended up so integrated in the process that they couldn’t criticise it.” They realised the contradiction between Ulm design and consumer capitalism, which had been developing along the same timeline. “Those at the school became dissatisfied with the idea of design furnishing market positions, constantly producing cycles of consumptive acts, and they struggled to resolve it.”

The school’s project had been to make the world rational and complete, industrially-based and free. “Instead they were producing something prison-like, individuals were becoming increasingly separate from each other and unable to see over their horizon.” In the Ulm Journal, the school’s sporadic, tactically published magazine that covered happenings at, and the evolving thinking and pedagogical approach of Ulm, Marxist thinking had become an increasingly important reference. “It was key to their understanding the context they were acting in, and if that thinking had been developed it would have led to an interesting and different kind of design, which they never got round to filling in. But they created a space for it.”

Foundation Course exercise

Student: Hans von Klier

Instructor: Tomás Maldonado

1956

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise (detail)

Student: Hans von Klier

Instructor: Tomás Maldonado

1956

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

“[A Marxian approach] would inevitably lead you out of design in some way. And the Ulm Model, the title of the Raven Row exhibition, is slightly ironic because it isn’t really a model for anything, and I think they understood that towards the end. They started to consider critical design as something that had to not resemble design in its recognised form. It would be nominally designed, the categories by which it was generally intelligible would need to be dismantled.”

The school’s funding was equally problematic, while their independence from the state facilitated their ability to validate their social purpose, the private foundation that provided their income was funded by industry commissions and indirect government funding from the regional legislator. “Although they were only partially dependent on government money, they accrued so much debt that in the end they were entirely dependent on it. The school was becoming increasingly radical politically, and the more radical it became, the more its own relation to capitalism became problematic. Their industry commissions tied them to the market, the Ulm Model didn’t work out, and their numbers didn’t add up.”

The Ulm School closed in 1968, when state funding was entirely withdrawn, and its functionalist ideals were in crisis. Abraham Moles, an instructor at the school, had previously asserted the inconsistency arising from the practice of functionalism under the conditions of ‘the affluent society’, “which for the sake of ever expanding production requires that needs remain unsatisfied.” And although he had encouraged the school to anticipate and respond to the problem, so as to be the “subject instead of the object of a crisis”; he hadn’t offered concrete ideas on how that might be achieved.

But correcting the course of capitalist infrastructure isn’t something the Ulm School could have been expected to achieve, “and although the project was ill-construed, it is productive as a resource for thinking about what a critical design practice could be in relation to capitalism.” What’s interesting about the Ulm Model today is their consideration of the purpose of education, and their questioning of whether it should merely reflect the current state of things – “preparing a workforce for essentially increasing the GDP; and establishing the efficiency of contributing sectors in a kind of diabolical utilitarianism.”

Ulm Journal of the Hochschule für Gestaltung

Foundation Course exercise (detail)

Student: Bertus Mulder

1956-57

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise

Student: Hans von Klier

Instructor: Tomás Maldonado

1956

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise (detail)

Student: Bertus Mulder

Date unknown

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise

Student: Hans von Klier

Instructor: Tomás Maldonado

1956

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise (detail)

Student: Hans von Klier

Instructor: Helene Nonné-Schmidt

Date unknown

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Related Links:

Tuesday, June 07. 2016

Unconditional Basic Income, first national vote | #unconditional #income #automation

Note: I've posted several articles about automation recently. This was the occasion to continue collect some thoughts about the topic (automation then) so as the larger social implications that this might trigger.

But it was also a "collection" that took place at a special moment in Switzerland when we had to vote about the "Revenu the Base Inconditionnel" (Unconditional Basic Income). I mentioned it in a previous post ("On Algorithmic Communism"), in particular the relation that is often made between this idea (Basic Income / Universal Income) and the probable evolution of work in the decades to come (less work for "humans" vs. more for "robots").

Well, the campain and votation triggered very interesting debates among the civil population, but in the end and predictably, the idea was largely rejected (~25% of the voters accepted it, with some small geographical areas that indeed acceted it at more than 50% --urban areas mainly--. Some where not so far, for exemple the city capital, Bern, voted at 40% for the RBI).

This was very new and a probably too (?) early question for the Swiss population, but it will undoubtedly become a growing debate in the decades to come. A question that has many important associated stakes.

-----

Press talking about the RBI, image from RTS website.

More about it (in French) on the website of the swiss television.

Friday, May 27. 2016

What to Do When a Robot Is the Guilty Party | #ai #law #society #smart?

Note: "(...) For example, technologists might be held responsible if they use poor quality data to train AI systems, or fossilize prejudices based on race, age, or gender into the algorithms they design."

Mind your data and the ones you'll use to "fossilize", so to say (and as long as you'll already know what's in your data)... It is then no more about "if" you're collecting data, but "which" data you'll use to feed your AIs, and "how". Now that we clearly see that large corporations plan to use more and more of these kind of techs to also drive "domestic" applications (and by extension as we already know "personal" applications of all sorts), it will be important to understand the stakes behind them as it will become part of our social and design context.

An important problem that I can see for designers and architects is that if you don't agree with the principles --commercial, social, ethical and almost conceptual-- implied by the technologies (i.e. any "homekit" like platforms controlled by bots), you won't find many if any counter propositions/techs to work with (all large diffusion products will support iOS, Android and the likes). It is almost a dictatorship of products hidden behind a "participate" paradigma. Either you'll be in and accept the conditions (you might use an API provided with the service --FB, Twitter, IFTTT, Apple, Google, Wolfram, Siemens, MS, etc.--, but then feed the central company nonetheless), or out... or possibly develop you own solution(s) that will probably be a pain in the ass to use for your client because it/they will clearly be side products hard to maintain, update, etc.

"Some" open source projects driven by "some" communities could be/become (should be) alternative solutions of course, but for now these are good for prototyping and teaching, not for consistent "domestic" applications... And when they'll possibly do so, they might likely be bought. So we'll have "difficulties" as (interaction) designers, so to say: you'll work for your client(s) ... and the corp. that provides the services you'll use!

----

The Obama administration is vowing not to get left behind in the rush to artificial intelligence, but determining how to regulate it isn’t easy.

By Mark Harris

Should the government regulate artificial intelligence? That was the central question of the first White House workshop on the legal and governance implications of AI, held in Seattle on Tuesday.

“We are observing issues around AI and machine learning popping up all over the government,” said Ed Felten, White House deputy chief technology officer. “We are nowhere near the point of broadly regulating AI … but the challenge is how to ensure AI remains safe, controllable, and predictable as it gets smarter.”

One of the key aims of the workshop, said one of its organizers, University of Washington law professor Ryan Calo, was to help the public understand where the technology is now and where it’s headed. “The idea is not for the government to step in and regulate AI but rather to use its many other levers, like coördination among the agencies and procurement power,” he said. Attendees included technology entrepreneurs, academics, and members of the public.

In a keynote speech, Oren Etzioni, CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, noted that we are still in the Dark Ages of machine learning, with AI systems that generally only work well on well-structured problems like board games and highway driving. He championed a collaborative approach where AI can help humans to become safer and more efficient. “Hospital errors are the third-leading cause of death in the U.S.,” he said. “AI can help here. Every year, people are dying because we’re not using AI properly in hospitals.”

Oren Etzioni, CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, left, speaks with attendees at the White House workshop on artificial intelligence.

Nevertheless, Etzioni considers it far too early to talk about regulating AI: “Deep learning is still 99 percent human work and human ingenuity. ‘My robot did it’ is not an excuse. We have to take responsibility for what our robots, AI, and algorithms do.”

A panel on “artificial wisdom” focused on when these human-AI interactions go wrong, such as the case of an algorithm designed to predict future criminal offenders that appears to be racially biased. “The problem is not about the AI agents themselves, it’s about humans using technological tools to oppress other humans in finance, criminal justice, and education,” said Jack Balkin of Yale Law School.

Several academics supported the idea of an “information fiduciary”: giving people who collect big data and use AI the legal duties of good faith and trustworthiness. For example, technologists might be held responsible if they use poor quality data to train AI systems, or fossilize prejudices based on race, age, or gender into the algorithms they design.

As government institutions increasingly rely on AI systems for decision making, those institutions will need personnel who understand the limitations and biases inherent in data and AI technology, noted Kate Crawford, a social scientist at Microsoft Research. She suggested that students be taught ethics alongside programming skills.

Bryant Walker Smith from the University of South Carolina proposed regulatory flexibility for rapidly evolving technologies, such as driverless cars. “Individual companies should make a public case for the safety of their autonomous vehicles,” he said. “They should establish measures and then monitor them over the lifetime of their systems. We need a diversity of approaches to inform public debate.”

This was the first of four workshops planned for the coming months. Two will address AI for social good and issues around safety and control, while the last will dig deeper into the technology’s social and economic implications. Felten also announced that the White House would shortly issue a request for information to give the general public an opportunity to weigh in on the future of AI.

The elephant in the room, of course, was November’s presidential election. In a blog post earlier this month, Felten unveiled a new National Science and Technology Council Subcommittee on Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence, focused on using AI to improve government services “between now and the end of the Administration.”

Related Links:

Monday, April 04. 2016

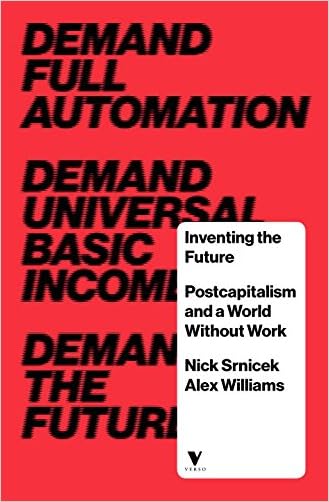

On Algorithmic Communism - Ian Lowrie on Inventing the Future : Postcapitalism and a World Without Work | #algorithms #future #postcapitalism

Note: in a time when we'll soon have for the first time a national vote in Switzeralnd about the Revenu de Base Inconditionnel ("Universal Basic Income") --next June, with a low chance of success this time, let's face it--, when people start to speak about the fact that they should get incomes to fuel global corporations with digital data and content of all sorts, when some new technologies could modify the current digital deal, this is a manifesto that is certainly more than interesting to consider. So as its criticism in this paper, as it appears truly complementary.

More generally, thinking the Future in different terms than liberalism is an absolute necessity. Especially in a context where, also as stated, "Automation and unemployment are the future, regardless of any human intervention".

Via Los Angeles Review of Books

-----

By Ian Lowrie

January 8th, 2016

IN THE NEXT FEW DECADES, your job is likely to be automated out of existence. If things keep going at this pace, it will be great news for capitalism. You’ll join the floating global surplus population, used as a threat and cudgel against those “lucky” enough to still be working in one of the few increasingly low-paying roles requiring human input. Existing racial and geographical disparities in standards of living will intensify as high-skill, high-wage, low-control jobs become more rarified and centralized, while the global financial class shrinks and consolidates its power. National borders will continue to be used to control the flow of populations and place migrant workers outside of the law. The environment will continue to be the object of vicious extraction and the dumping ground for the negative externalities of capitalist modes of production.

It doesn’t have to be this way, though. While neoliberal capitalism has been remarkably successful at laying claim to the future, it used to belong to the left — to the party of utopia. Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams’s Inventing the Future argues that the contemporary left must revive its historically central mission of imaginative engagement with futurity. It must refuse the all-too-easy trap of dismissing visions of technological and social progress as neoliberal fantasies. It must seize the contemporary moment of increasing technological sophistication to demand a post-scarcity future where people are no longer obliged to be workers; where production and distribution are democratically delegated to a largely automated infrastructure; where people are free to fish in the afternoon and criticize after dinner. It must combine a utopian imagination with the patient organizational work necessary to wrest the future from the clutches of hegemonic neoliberalism.

Strategies and Tactics

In making such claims, Srnicek and Williams are definitely preaching to the leftist choir, rather than trying to convert the masses. However, this choir is not just the audience for, but also the object of, their most vituperative criticism. Indeed, they spend a great deal of the book arguing that the contemporary left has abandoned strategy, universalism, abstraction, and the hard work of building workable, global alternatives to capitalism. Somewhat condescendingly, they group together the highly variegated field of contemporary leftist tactics and organizational forms under the rubric of “folk politics,” which they argue characterizes a commitment to local, horizontal, and immediate actions. The essentially affective, gestural, and experimental politics of movements such as Occupy, for them, are a retreat from the tradition of serious militant politics, to something like “politics-as-drug-experience.”

Whatever their problems with the psychodynamics of such actions, Srnicek and Williams argue convincingly that localism and small-scale, prefigurative politics are simply inadequate to challenging the ideological dominance of neoliberalism — they are out of step with the actualities of the global capitalist system. While they admire the contemporary left’s commitment to self-interrogation, and its micropolitical dedication to the “complete removal of all forms of oppression,” Srnicek and Williams are ultimately neo-Marxists, committed to the view that “[t]he reality of complex, globalised capitalism is that small interventions consisting of relatively non-scalable actions are highly unlikely to ever be able to reorganise our socioeconomic system.” The antidote to this slow localism, however, is decidedly not fast revolution.

Instead, Inventing the Future insists that the left must learn from the strategies that ushered in the currently ascendant neoliberal hegemony. Inventing the Future doesn’t spend a great deal of time luxuriating in pathos, preferring to learn from their enemies’ successes rather than lament their excesses. Indeed, the most empirically interesting chunk of their book is its careful chronicle of the gradual, stepwise movement of neoliberalism from the “fringe theory” of a small group of radicals to the dominant ideological consensus of contemporary capitalism. They trace the roots of the “neoliberal thought collective” to a diverse range of trends in pre–World War II economic thought, which came together in the establishment of a broad publishing and advocacy network in the 1950s, with the explicit strategic aim of winning the hearts and minds of economists, politicians, and journalists. Ultimately, this strategy paid off in the bloodless neoliberal revolutions during the international crises of Keynesianism that emerged in the 1980s.

What made these putsches successful was not just the neoliberal thought collective’s ability to represent political centrism, rational universalism, and scientific abstraction, but also its commitment to organizational hierarchy, internal secrecy, strategic planning, and the establishment of an infrastructure for ideological diffusion. Indeed, the former is in large part an effect of the latter: by the 1980s, neoliberals had already spent decades engaged in the “long-term redefinition of the possible,” ensuring that the institutional and ideological architecture of neoliberalism was already well in place when the economic crises opened the space for swift, expedient action.

Demands

Srnicek and Williams argue that the left must abandon its naïve-Marxist hopes that, somehow, crisis itself will provide the space for direct action to seize the hegemonic position. Instead, it must learn to play the long game as well. It must concentrate on building institutional frameworks and strategic vision, cultivating its own populist universalism to oppose the elite universalism of neoliberal capital. It must also abandon, in so doing, its fear of organizational closure, hierarchy, and rationality, learning instead to embrace them as critical tactical components of universal politics.

There’s nothing particularly new about Srnicek and Williams’s analysis here, however new the problems they identify with the collapse of the left into particularism and localism may be. For the most part, in their vituperations, they are acting as rather straightforward, if somewhat vernacular, followers of the Italian politician and Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci. As was Gramsci’s, their political vision is one of slow, organizationally sophisticated, passive revolution against the ideological, political, and economic hegemony of capitalism. The gradual war against neoliberalism they envision involves critique and direct action, but will ultimately be won by the establishment of a post-work counterhegemony.

In putting forward their vision of this organization, they strive to articulate demands that would allow for the integration of a wide range of leftist orientations under one populist framework. Most explicitly, they call for the automation of production and the provision of a basic universal income that would provide each person the opportunity to decide how they want to spend their free time: in short, they are calling for the end of work, and for the ideological architecture that supports it. This demand is both utopian and practical; they more or less convincingly argue that a populist, anti-work, pro-automation platform might allow feminist, antiracist, anticapitalist, environmental, anarchist, and postcolonial struggles to become organized together and reinforce one another. Their demands are universal, but designed to reflect a rational universalism that “integrates difference rather than erasing it.” The universal struggle for the future is a struggle for and around “an empty placeholder that is impossible to fill definitively” or finally: the beginning, not the end, of a conversation.

In demanding full automation of production and a universal basic income, Srnicek and Williams are not being millenarian, not calling for a complete rupture with the present, for a complete dismantling and reconfiguration of contemporary political economy. On the contrary, they argue that “it is imperative […] that [the left’s] vision of a new future be grounded upon actually existing tendencies.” Automation and unemployment are the future, regardless of any human intervention; the momentum may be too great to stop the train, but they argue that we can change tracks, can change the meaning of a future without work. In demanding something like fully automated luxury communism, Srnicek and Williams are ultimately asserting the rights of humanity as a whole to share in the spoils of capitalism.

Criticisms

Inventing the Future emerged to a relatively high level of fanfare from leftist social media. Given the publicity, it is unsurprising that other more “engagé” readers have already advanced trenchant and substantive critiques of the future imagined by Srnicek and Williams. More than a few of these critics have pointed out that, despite their repeated insistence that their post-work future is an ecologically sound one, Srnicek and Williams evince roughly zero self-reflection with respect either to the imbrication of microelectronics with brutally extractive regimes of production, or to their own decidedly antiquated, doctrinaire Marxist understanding of humanity’s relationship towards the nonhuman world. Similarly, the question of what the future might mean in the Anthropocene goes largely unexamined.

More damningly, however, others have pointed out that despite the acknowledged counterintuitiveness of their insistence that we must reclaim European universalism against the proliferation of leftist particularisms, their discussions of postcolonial struggle and critique are incredibly shallow. They are keen to insist that their universalism will embrace rather than flatten difference, that it will be somehow less brutal and oppressive than other forms of European univeralism, but do little of the hard argumentative work necessary to support these claims. While we see the start of an answer in their assertion that the rejection of universal access to discourses of science, progress, and rationality might actually function to cement certain subject-positions’ particularity, this — unfortunately — remains only an assertion. At best, they are being uncharitable to potential allies in refusing to take their arguments seriously; at worst, they are unreflexively replicating the form if not the content of patriarchal, racist, and neocolonial capitalist rationality.

For my part, while I find their aggressive and unapologetic presentation of their universalism somewhat off-putting, their project is somewhat harder to criticize than their book — especially as someone acutely aware of the need for more serious forms of organized thinking about the future if we’re trying to push beyond the horizons offered by the neoliberal consensus.

However, as an anthropologist of the computer and data sciences, it’s hard for me to ignore a curious and rather serious lacuna in their thinking about automaticity, algorithms, and computation. Beyond the automation of work itself, they are keen to argue that with contemporary advances in machine intelligence, the time has come to revisit the planned economy. However, in so doing, they curiously seem to ignore how this form of planning threatens to hive off economic activity from political intervention. Instead of fearing a repeat of the privations that poor planning produced in earlier decades, the left should be more concerned with the forms of control and dispossession successful planning produced. The past decade has seen a wealth of social-theoretical research into contemporary forms of algorithmic rationality and control, which has rather convincingly demonstrated the inescapable partiality of such systems and their tendency to be employed as decidedly undemocratic forms of technocratic management.

Srnicek and Williams, however, seem more or less unaware of, or perhaps uninterested in, such research. At the very least, they are extremely overoptimistic about the democratization and diffusion of expertise that would be required for informed mass control over an economy planned by machine intelligence. I agree with their assertion that “any future left must be as technically fluent as it is politically fluent.” However, their definition of technical fluency is exceptionally narrow, confined to an understanding of the affordances and internal dynamics of technical systems rather than a comprehensive analysis of their ramifications within other social structures and processes. I do not mean to suggest that the democratic application of machine learning and complex systems management is somehow a priori impossible, but rather that Srnicek and Williams do not even seem to see how such systems might pose a challenge to human control over the means of production.

In a very real sense, though, my criticisms should be viewed as a part of the very project proposed in the book. Inventing the Future is unapologetically a manifesto, and a much-overdue clarion call to a seriously disorganized metropolitan left to get its shit together, to start thinking — and arguing — seriously about what is to be done. Manifestos, like demands, need to be pointed enough to inspire, while being vague enough to promote dialogue, argument, dissent, and ultimately action. It’s a hard tightrope to walk, and Srnicek and Williams are not always successful. However, Inventing the Future points towards an altogether more coherent and mature project than does their #ACCELERATE MANIFESTO. It is hard to deny the persuasiveness with which the book puts forward the positive contents of a new and vigorous populism; in demanding full automation and universal basic income from the world system, they also demand the return of utopian thinking and serious organization from the left.

Related Links:

Monday, March 17. 2014

Air public | #atmosphere #health #public

Via Le Monde, via Philippe Rahm Architectes

-----

Par Philippe Rahm

A quelques semaines des élections municipales, il n'a jamais fait aussi beau à Paris. Le soleil brille, il fait chaud et pourtant on nous déconseille de sortir dehors à cause de la pollution de l'air qui atteint des sommets. Mauvaise nouvelle pourdéjeuner en terrasse. C'est assez paradoxal, ce beau temps qui ne l'est en réalité pas. Cela ne va pas de soi et il nous faudra réviser à l'avenir nos critère du beau et du laid, ne plus se fier au perceptible, au soleil, à la température et au ciel bleu, mais plutôt à l'invisible et se dire le matin qu'il fait beau seulement quand le bulletin météo annoncera pour la journée un taux bas de particules fines dans l'air.

Le nuage de pollution à Paris, jeudi 13 mars. | AP/Christophe Ena

Mais si le bulletin météo classique nous informait de l'état du ciel selon des forces naturelles qui nous dépassaient et contre lequel on ne pouvait choisir que de prendre ou pas son parapluie, le problème de la pollution des villes est une conséquence des activités humaines. Et parce qu'il nous concerne tous, parce qu'il définit la réalité chimique de nos rues et de nos places, parce qu'il menace notre santé, il est éminemment politique. J'affirmerai même qu'il est la raison d'être fondamentale du politique: celle de nous assurer à tous une bonne santé. Le politique est né de la gestion sanitaire de la ville et de la définition de ses valeurs publics que l'on retrouve inscrit aujourd'hui dans les règlements et les plans d'urbanisme: avoir de la lumière naturelle dans toutes les chambres, boire de l'eau potable, évacuer et traiter les déchets et les excréments. En-dessous de son interprétation culturelle, l'Histoire de l'urbanisme et du politique est finalement celle d'une conquête physiologique, pour les villes, pour les hommes, du bien-être, du confort, de la bonne santé.

Et respirer un air sain en ville ? Ne pourrait-on pas penser que c'est finalement cela que l'on demande aujourd'hui au politique ? La demande n'est pas neuve. Au début du XIXe siècle, Rambuteau, préfet de Paris, avait tracé la rue du même nom au coeur du Marais pour faire circuler l'air pour éviter le confinement des germes. Dans sa suite, le préfet Haussmann traçait les boulevards dans un même soucis d'hygiène, y plantait des arbres pour les tempérer, créaient des parcs (les Buttes-Chaumont, le bois de Boulogne, etc.) comme Olmsted avec Central Park à New-York, conçues à la manière de poumons verts pour rafraîchir la ville en été, absorber les poussières et la pollution, améliorer la qualité de l'air, parce qu'à l'époque, on mourrait réellement de tuberculoses et des autres maladies bactériennes dans les villes.

Mais toutes ces mesures sanitaires ont perdu leur légitimité avec la découverte de la pénicilline et la diffusion des antibiotique à partir les années 1950. À quoi cela servait-il encore de raser les petites rues sans air et obscures du Moyen-Âge, de déplacer les habitations dans de vastes parcs de verdure si l'on pouvait chasser la maladie simplement avec un antibiotique à avaler deux fois par jour durant une semaine. Etait-ce vraiment raisonnable d'élargir les petites fenêtres des vieilles maisons en pierre, d'enlever les toits en pentes pour en faire des toits terrasses, si en réalité, on pouvait éviter la maladie avec un peu de pénicilline ?

Si l'on a arrêté de démolir les vieux quartiers des villes européennes à partir des années 1970, si on a commencé à trouver du charme aux ruelles tortueuses et aux vieilles maisons étroites du Moyen-Âge, aux intérieurs sombres et humides des centres villes, si les prix des arrondissements historiques que tout le monde désertait jusqu'aux années 1970 ont commencé à grimper, si des mesures de protections du patrimoine ont été votées, si ces vielles pierres sont devenues des témoins de notre civilisation et un atout touristique et économique, si l'on est revenu habiter les vieux centres historiques, on le doit peut-être autant aux théories post-modernes de Bernard Huet, l'architecte des la place Stalingrad et des Champs-Elysées dans les années 1980, qu'à la découverte médicale des antibiotiques.

Mais les antibiotiques ne peuvent rien contre la pollution aux particules fines d'aujourd'hui. Cela veut-il dire que nous allons assister au même phénomène que durant la première partie du XXe siècle, celle d'une désertion des centre-villes, d'une perte de valeur immobilière des quartiers centraux de Paris, au profit des banlieues et des campagnes où l'air n'est pas polluée ? La ville que l'on a réappris à aimer et à habiter à la fin du XXe siècle va t-elle retombée dans la désolation ? On peut tenter de croire, dans un monde globalisé, que la mission de la politique locale est aujourd'hui de réduire le chômage ou de diminuer les impôts. Mais plus profondément, le politique se doit aujourd'hui de reprendre en main sa mission fondamentale, celle d'assurer la qualité de nos biens publics, celle de nous offrir en ville, après l'eau et la lumière, un air de qualité, seule garantie pour la prospérité sociale et économique future.

Philippe Rahm construit en ce moment un parc de 70 hectares pour la ville de Taichung à Taiwan, livré en décembre 2015 qui propose d'atténuer la chaleur, l'humidité et la pollution de l'air par l'emploi du végétal et de technologies vertes.

Philippe Rahm (Architecte et enseignant aux Universités de Princeton et Harvard (Etats-Unis))

Related Links:

Friday, February 28. 2014

Big Data, Big Questions | #smart? #data #monitoring

It looks like managing a "smart" city is similar to a moon mission! IBM Intelligent Operations Center in Rio de Janeiro.

Via Metropolis

-----

IBM, INTELLIGENT OPERATIONS CENTER, RIO DE JANEIRO

At the Intelligent Operations Center in Rio, workers manage the city from behind a giant wall of screens, which beam them data on how the city is doing— from the level of water in a street following a rainstorm to a recent mugging or a developing traffic jam. As the home to both the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics, the city hopes to prove it can be in control of itself, even under pressure. And IBM hopes to prove the power of its new Smarter Cities software to a global audience.

And an intersting post, long and detailed (including regarding recent IBM, CISCO, Siemens "solutions" and operations), about smart cities in the same article, by Alex Marshall:

"The smart-city movement spreading around the globe raises serious concerns about who controls the information, and for what purpose."

More about it HERE.

Tuesday, February 04. 2014

Appropriating Interaction Technologies (“Social Hacking”) at ITP | #code

-----

By Lauren McCarthy & Kyle McDonald

AIT (“Social Hacking”), taught for the first time this semester by Lauren McCarthy and Kyle McDonald at NYU’s ITP, explored the structures and systems of social interactions, identity, and self representation as mediated by technology. The semester was spent developing projects that altered or disrupted social space in an attempt to reveal existing patterns or truths about our experiences and technologies, and possibilities for richer interactions.

The class began by exploring the idea of “social glitch”, drawing on ideas from glitch theory, social psychology, and sociology, including Harold Garfinkel’s breaching experiments, Stanley Milgram’s subway experiments, and Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical analysis of social interaction. If “glitch” describes when a system breaks down and reveals something about its structure or self in the process, what might this look like in the context of social space?

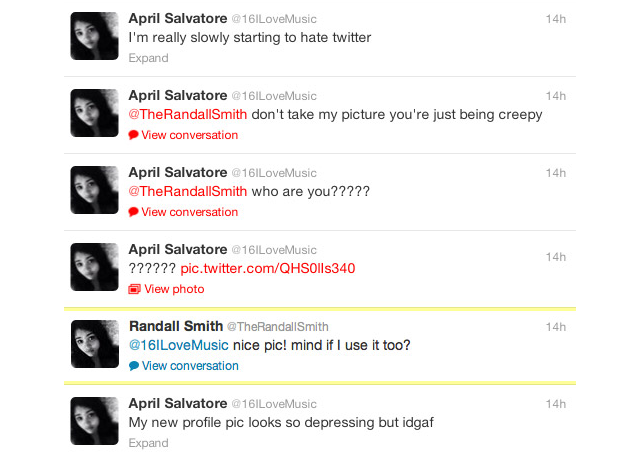

Bill Lindmeier wrote a Ruby script using the Twitter Stream API to listen for any Tweets containing “new profile pic.” When a Tweet was posted the script would download the user’s profile image, upload it to his own account and then reply to the user with a randomly selected Tweet, like “awesome pic!”. The reactions ranged from humored to furious.

Along similar lines, Ilwon Yoon implemented a script that searched for Tweets containing “I am all alone” and replied with cute images obtained from a Google image search and “you are not alone” text.

Mack Howell built on the in-class exercise of asking strangers to borrow their phone then doing something unexpected with it, asking to take pictures of strangers’ browsing history.

The class next turned it’s attention to social automation and APIs, and the potential for their creative misuse.

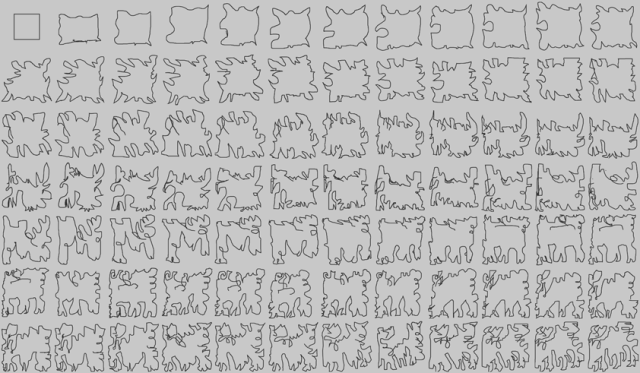

Gal Sasson used the Amazon Mechanical Turk API to create collaborative noise, creating a chain where each turker was prompted to replicate a drawing from the previous turker, seeding the first turker with a perfect square.

Mack Howell used the Google Street View Image API to map out the traceroutes from his location to the data centers of the his most frequently visited IPs.

In another assignment, students were prompted to create an “HPI” (human programming interface) that allowed others to control some aspect of their lives, and perform the experiment for one full week.

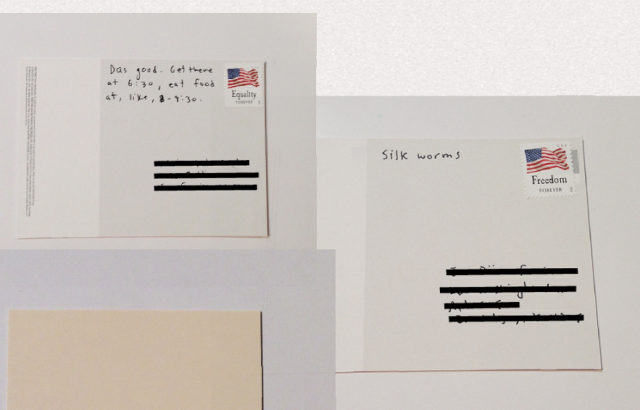

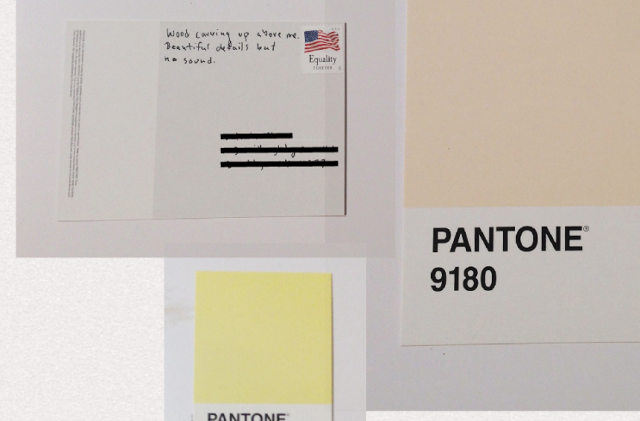

Anytime an email or Twitter direct message was sent to Ben Kauffman with the hashtag #brainstamp and a mailing address, he would get an SMS with the information and promptly right down on a postcard whatever was in his head at that exact moment. He would then mail the thoughts, at turns surreal and mundane, to the awaiting recipient. An alternative to normal social media, Ben challenged us to find ways to be more present while documenting our lives.

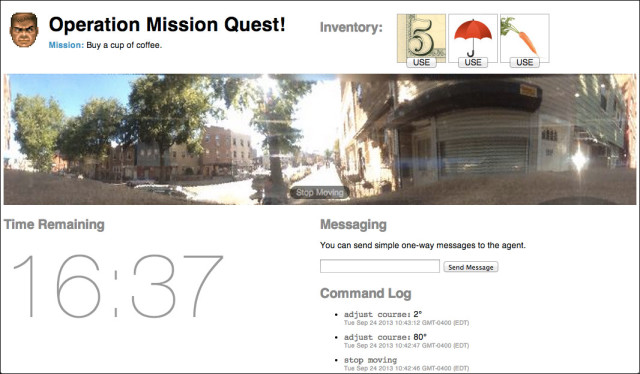

Bill Lindmeier invited his friends to control his movements in realtime through a Google-street-view-esque video interface, and asked them to complete a simple mission: Buy some coffee in under 20 minutes. The tools at their disposal: $5, an umbrella and a carrot.

Mack Howell created a journal written by Amazon Mechanical Turk workers, asking them to generate diary entries based on OpenPaths data sent automatically as he moved around.

In a project called My Friends Complete Me, Su Hyun Kim posted binary questions on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and let her friends collective opinion determine her life choices, including deciding whether to change her last name when she got married.

A couple weeks were spent having focused discussions about security, privacy, and surveillance, including topics like quantified self, government surveillance and historical regimes of naming, and readings from Bruce Schneier, Evgeny Morozov and Steve Mann. In parallel, students were asked to examine their own social lives and compulsively document, share, intercept, impersonate, anonymize and misinterpret.

Mike Allison explored our voyeuristic nature and cultural craving for surveillance, allowing users to watch someone watch someone who may be watching them. In order to watch, users must lend their own camera to the system.

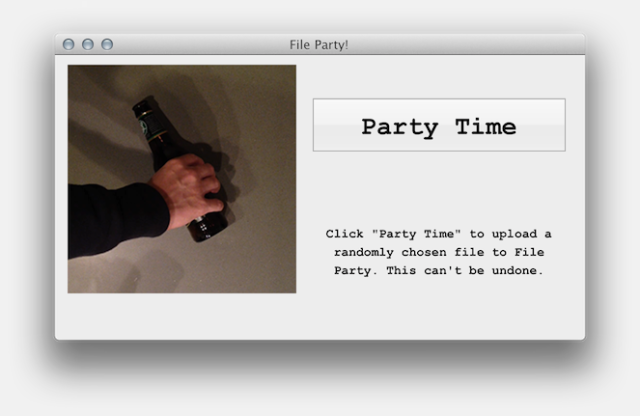

Bill Lindmeier created an app called File Party, a repository of files that have been randomly selected and uploaded from peoples’ hard-drive. In order to view the files, you have to upload one yourself.

In a unit on computer vision and linguistic analysis, students were paired up and asked to create a chat application that provided a filter or adapter that improved their interaction.

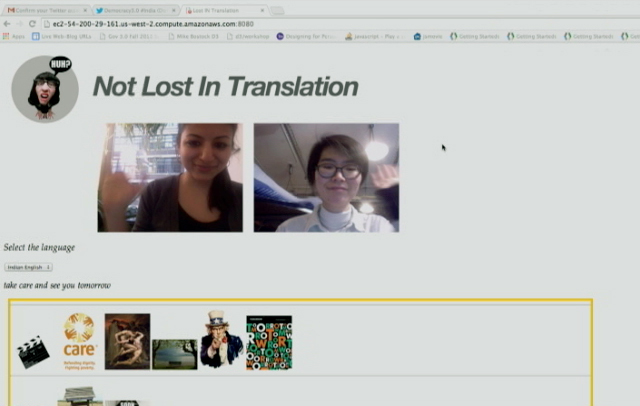

Realizing how much is lost in translation and accents, Tarana Gupta and Hanbyul Jo developed a video chat tool which allows users to talk in their respective language and and displays in real-time text and images corresponding to what is being said.

In FlapChat, Su Hyun Kim and Gal Sasson rethought the way we interact with the web camera, allowing users to flap their arms to fly around a virtual environment while chatting.

Overall, the most successful moments in the class were the ones where students had an opportunity to examine an otherwise common technology or interaction from a new perspective. Short in-class exercises like “ask a stranger to use their phone, and do something unexpected” gave students a reference point for discussion. The “HPI” assignment gave students an unusual challenge of “performing” something for a week, lead to its own set of difficulties and realizations that are distinct from purely technical or aesthetic exercises. On the first day of class a contract was handed out requiring that students respect others’ positions in class, and take responsibility for any actions outside of class. This created a unfamiliar atmosphere and opened up the students to question their freedoms and responsibilities towards each other.

In the future, each two- or three-week section might be expanded to fit a whole semester. Of particular interest were the computer vision, security and surveillance, and mobile platforms sections. Leftover discussion from security and surveillance spilled into the next week, and assignments for mobile platforms could have been taken far beyond the proof-of-concept or design-only stages.

More information about the class, including the complete syllabus, reading lists, and some example code, is available on GitHub.

A condensed version of this class will be taught in January at GAFFTA in San Francisco, details will be announced soon with more information here.

About the Tutors:

Kyle McDonald is a media artist who works with code, with a background in philosophy and computer science. He creates intricate systems with playful realizations, sharing the source and challenging others to create and contribute. Kyle is a regular collaborator on arts-engineering initiatives such as openFrameworks, having developed a number of extensions which provide connectivity to powerful image processing and computer vision libraries. For the past few years, Kyle has applied these techniques to problems in 3D sensing, for interaction and visualization, starting with structured light techniques, and later the Kinect. Kyle’s work ranges from hyper-formal glitch experiments to tactical and interrogative installations and performance. He was recently Guest Researcher in residence at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media, Japan, and is currently adjunct professor at ITP.

Lauren McCarthy is an artist and programmer based in Brooklyn, NY. She is adjunct faculty at RISD and NYU ITP, and a current resident at Eyebeam. She holds an MFA from UCLA and a BS Computer Science and BS Art and Design from MIT. Her work explores the structures and systems of social interactions, identity, and self-representation, and the potential for technology to mediate, manipulate, and evolve these interactions. She is fascinated by the slightly uncomfortable moments when patterns are shifted, expectations are broken, and participants become aware of the system. Her artwork has been shown in a variety of contexts, including the Conflux Festival, SIGGRAPH, LACMA, the Japan Media Arts Festival, the File Festival, the WIRED Store, and probably to you without you knowing it at some point while interacting with her.

Related Links:

Friday, January 24. 2014

Bracket [takes action] | #call

A new call by the very interesting Bracket magazine/books!

Via Bracket

-----

Bracket [takes action]

“When humans assemble, spatial conflicts arise. Spatial planning is often considered the management of spatial conflicts.” —Markus Miessen

Hannah Arendt’s 1958 treatise The Human Condition cites “action” as one of the three tenants, along with labor and work, of the vita active (active life). Action, she writes, is a necessary catalyst for the human condition of plurality, which is an expression of both the common public and distinct individuals. This reading of action requires unique and free individuals to act toward a collective project and is therefore simultaneously ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’. In the more than fifty years since Arendt’s claims, the public realm in which action materializes, and the means by which action is expressed, has dramatically transformed. Further, spatial practice’s role in anticipating, planning, or absorbing action(s) has been challenged, yielding difficulty in the design of the ‘space of appearance,’ Arendt’s public realm.

Our young century has already seen contested claims of design’s role in the public realm by George Baird, Lieven De Cauter, Markus Meissen, Jan Gehl, among others. Perhaps we could characterize these tensions as a ‘design deficit’, or a sense that design does not incite ‘action’, in the Arendtian sense. Amongst other things, this feeling is linked to the rise of neo-liberal pluralism, which marks the transition from public to publics, making a collective agenda in the public realm often illegible. Bracket [takes action] explores the complex relationship between spatial design, and the public(s) as well as action(s) it contains. How can design catalyze a public and incite platforms for action?

Consider two images indicative of contemporary action within the public realm of our present century: (i) the June 2009 opening of the High Line Park in New York City, and (ii) the January 2011 occupation of Tahrir Square in Cairo. These two spaces and their respective contemporary publics embody the range within today’s space of appearance. At the High Line, the urban public is now choreographed in a top-down manner along a designed, former infrastructure with an endless supply of vistas into an urban private realm. In Tahrir Square, an assembled swirling public occupies, and therefore re-designs, an infrastructural plaza overwhelming a government and communication networks. This example reveals a bottom-up, self-assembling public. But what role did spatial practice play in each of these scenarios and who were the spatial practitioners and public(s)? The contrast of two positions on action in a public realm offers an opening for wider investigations into spatial practice’s role and impact on today’s public(s) and their action(s).

Bracket [takes action] asks: What are the collective projects in the public realm to act on? How have recent design projects incited political or social action? How can design catalyze a public, as well as forums for that public to act? What is the role of spatial practice to instigate or resist public actions? Bracket 4 provokes spatial practice’s potential to incite and respond to action today.

The fourth edition of Bracket invites design work and papers that offer contemporary models of spatial design that are conscious of their public intent and actively engaged in socio-political conditions. It is encouraged, although not mandatory, that submissions documenting projects be realized. Positional papers should be projective and speculative or revelatory, if historical. Suggested subthemes include:

Participatory ACTION – interactive, crowd-sourced, scripted

Disputed PUBLICS – inconsistent, erratic, agonized

Deviant ACTION – subversive, loopholes, reactive

Distributed PUBLICS – broadcasted, networked, diffused

Occupy ACTION – defiant, resistant, upheaval

Mob PUBLICS – temporary, forceful, performative

Market ACTION – abandoning, asserting, selecting

The editorial board and jury for Bracket 4 includes Pier Vittorio Aureli, Vishaan Chakrabarti, Adam Greenfield, Belinda Tato, Yoshiharu Tsukamoto as well as co-editors Neeraj Bhatia and Mason White.

Deadline for Submissions: February 28, 2014

Please visit www.brkt.org for more info.

Related Links:

Wednesday, October 30. 2013

Le drone, objet violent non identifié | #drones

Via Le Temps (thx Nicolas Besson for the link)

-----

Par Réda Benkirane

Dans un livre pionnier, «Théorie du drone», le philosophe français Grégoire Chamayou analyse le rôle grandissant du drone dans la guerre moderne, et sur ce qu’il changera en termes de géopolitique et de surveillance globale.

Grégoire Chamayou, Editions La Fabrique, 363 pages.

Le drone est un «objet violent non identifié» qui est en train de miner le concept de guerre tel qu’on le connaît depuis Sun Tzu jusqu’à Clausewitz. Dans une œuvre de pionnier, le philosophe français Grégoire Chamayou décode cet objet qui soulève quantité de questions relatives à la stratégie, à la violence armée, à l’éthique de la guerre et de la paix, à la souveraineté et au droit. Le drone et ses clones robotiques ouvrent au sein des conflits violents une vaste terra incognita totalement impensée par le droit international et les lois immémoriales de la guerre.

Dans un ouvrage magistral, le philosophe entreprend la toute première réflexion sur cette nouvelle forme de violence, née de la généralisation d’un gadget militaire, le drone, ce véhicule terrestre, naval ou aéronautique sans homme à son bord (unmanned).

Les drones Predator et Reaper ont la particularité de voler à plus de 6000 mètres d’altitude et d’être télécommandés par des individus souvent civils (faut-il les considérer comme des combattants?) depuis une salle de contrôle informatique du Nevada. D’un clic de souris, un téléopérateur appuie sur une gâchette et déclenche un missile distant de milliers de kilomètres qui immédiatement s’abat sur un village du Pakistan, du Yémen ou de Somalie. Le drone est «l’œil de Dieu», il entend et intercepte toutes sortes de données qu’il fusionne (data fusion) et archive à la volée: en une année, il a généré l’équivalent de 24 années d’enregistrements vidéo.

Cette Théorie du drone a le mérite d’informer sur la mutation majeure des conflits violents entamée sous les présidences Bush et adoptée par l’administration d’Obama. Le drone et la suite des engins tueurs qui se profilent à l’horizon – les Etats-Unis disposent de 6000 drones et travaillent à des avions de chasse sans pilote pour 2030 – transforment une tactique adjacente en stratégie globale, et font de l’anti-terrorisme et de la politique sécuritaire leur doctrine de combat du siècle. Initiés par les Israéliens, premiers adeptes de l’euphémique devise «personne ne meurt sauf l’ennemi», puis repris par les «neocons» américains, les drones font le miel de l’équipe d’Obama, pour qui «tuer vaut mieux que capturer», liquider par avance les suspects terroristes étant préférable à leur enfermement à Guantanamo.

L’auteur poursuit sa démonstration sur l’imprécision et la contre-productivité du drone; du fait de l’altitude à laquelle il opère, son rayon létal est de 20 mètres, tandis que celui d’une grenade est de 3 mètres. Seule la munition classique peut être véritablement considérée comme une «arme chirurgicale» du point de vue de sa précision létale. Etant donné les milliers de morts civils qu’ils ont occasionnés, les drones ont aussi le désavantage de rallier toujours plus les populations locales aux groupuscules terroristes.

L’auteur montre comment la diminution croissante des morts des militaires et l’extension continue du «dommage collatéral» – ce mot qui cache depuis la fin de la Guerre froide la liquidation informelle de civils non combattants – procèdent de l’assomption suivante: dès qu’un actant de «l’axe du mal» est identifié, son réseau social fait de facto partie du c(h)amp du mal que l’on pourra vitrifier depuis une interface informatique. Certains avancent même l’idéal déréalisant que la robotique létale constituerait l’«arme humanitaire» par excellence et l’auteur fait observer combien l’euphémisation des enjeux militaires est légitimée par la rhétorique du care. Chamayou voit dans la novlangue sur le militaire humanitaire les débuts d’une politique «humilitaire».

La géopolitique est en train de laisser place à une aéropolitique. La guerre n’est plus un affrontement ni un duel entre parties combattantes sur un territoire délimité, mais une «chasse à l’homme», où un prédateur poursuit partout et tout le temps une proie humaine. Les notions de temporalité, de territorialité, de frontière, d’éthique guerrière et de droit humanitaire sont rendues obsolètes par ces armes low cost et high-tech.

L’auteur prédit un avenir fait de robots-insectes miniaturisés – les nanotechnologies aidant – concourant à la mise en place d’un système panoptique complet qui risque d’enserrer les Etats et les citoyens.

Cet ouvrage, d’ores et déjà incontournable, en appelle à une prise de conscience politique face à la déshumanisation en cours derrière ce nouvel art de surveiller, d’intercepter et d’anéantir.

Related Links:

Personal comment:

Following my recent post about drones (as scanning devices), there are obviously different types of drones and like any other technology, it looks like that this one too has two sides... We are now probably in need of some renewed "Contrat Social" that would take into account additional "parameters" (between humans and machines/technologies + between humans and our planet --Contrat naturel--).

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.

Quicksearch

Categories

Calendar

|

|

July '25 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||