Sticky Postings

All 242 fabric | rblg updated tags | #fabric|ch #wandering #reading

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Tuesday, April 18. 2017

Ghost in the Shell movie city design, Ash Thorp | #movie #3d #fiction #architecture

Note: following the post about the conference at Bartlett about game design and architecture, I also post this link (show reel) regarding the recent set & prop design for the movie Ghost in the Shell.

We can certainly discuss the quality of the movie indeed, or rather its necessity compared to the original japan anime (a funny remark about it though: if you have the questionable chance to be "reborned" or "ghosted" like the major in the remade movie, you'll transform from asian to caucasian white ... Which is the same fate as the movie in fact, if you have the chance to be "redone", you'll go from japan anime to Hollywood pimped movie...), but we can all agree about the quality of the environment and character design nonetheless. Even if conceptually, this future looks a lot like an "hyper-present" (more networks, more media, more digital, more robots, cyborgs and viruses, more hackers, etc. - that will not happen therefore).

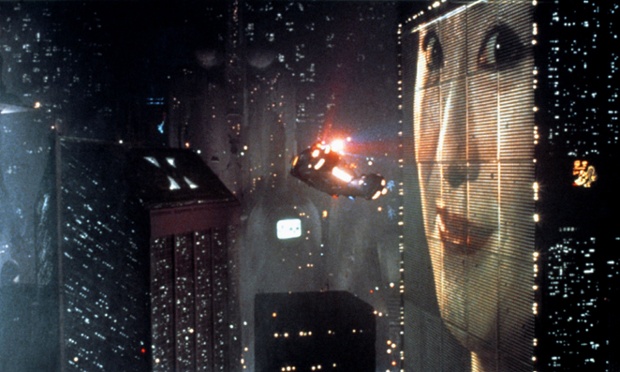

In particular for architects, the urban design of the "Hong Kong++" (or "Blade Runner++" ) style city, full of skyscrapers sized holograms, mostly publicities. A design in a kind of strange and brutal mish-mash with more regular yet buildings. This is the quite 3d graphical work ofAsh Thorp that i link below.

Considering these different exemples, we could wonder why architectural schools don't take more into consideration these kind of works? So as the ones present in literature. Couldn't we start thinking that architecture is a field that indeed and of course, build physical spaces and cities, but not only.

So, it should also take its part in the conceptualization and design of "networked", "virtual" or rather "mixed realities" (whatever further necessary debates we could have about the understanding of those words), environments for games and movies? Possibly also by extension non material spaces in general? And of course, all the probably more interesting "in betweens"? I truly believe architectural discourse could easily consider all these aspects of architecture and widen a bit its educational scope.

But I don't see this coming so much. Do you? (there are some discussion forums on Archinect for example)

Via Kotaku

-----

Some additionnal information about the conceptual work on the movie.

Another interesting and quite "space-graphical" short anime by Ash Thorp, "Epoch" - in a slightly "2001" style-, can be accessed on his site as well. And interestingly for 3d designers, he has created with fellow industry-artists a teaching platform led by professionals: Learn Squared (they are hosting a talk about the set design on Twitch next Wednesday btw). There can you learn "UI and Data Design for Film", "3D Concept Design", "Motion Design", etc.

More works about the movie HERE (in a post by Luke Plunkett).

Related Links:

Tuesday, September 23. 2014

Someone finally made a truly 3D movie | #messingwith3d

Note: Viva Jean-Luc!

Via The Verge

-----

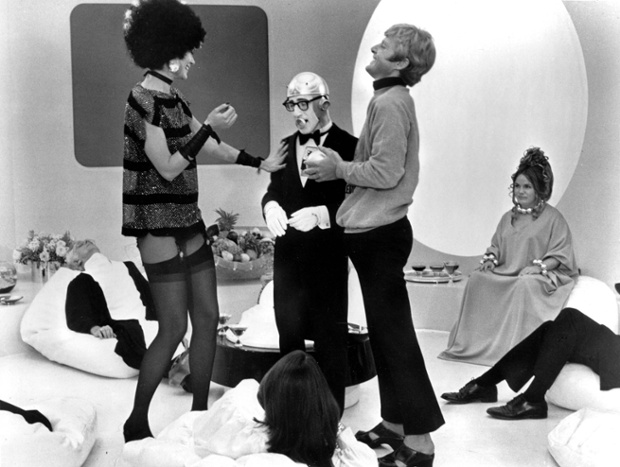

Jean-Luc Godard messes with 3D to wonderful results.

You’re probably at least a bit of a film nerd if you’re familiar with Jean-Luc Godard, the biggest name of the ’60s French New Wave movement. Even if you don’t know him, you've definitely seen a lot of film techniques that he pioneered. He's credited with turning the jump cut from an editing accident into a legitimate tool. And you know Wes Anderson's playful use of on-screen text and standout bright colors? Godard was doing that 30 years earlier. He’s been incredibly influential when it comes to what modern films look like, so when he decides to play with something new, it's worth paying close attention.

The movie is obtuse. Its techniques are anything but.

Godard's latest picture, Goodbye to Language, is his first feature shot in 3D. It's an impressionistic film about an affair, and for Godard it's as unapproachable as ever, with little semblance of narrative, strange interactions, and characters that basically just make heady declarative statements like, "A woman can do no harm. She can annoy. She can kill. No more." But whether you're interested in his avant-garde musings or not, there's one big reason to see this film: it may be the first one that really uses 3D to do something new.

A lot of great directors have tried their hand at 3D, including Ridley Scott and Martin Scorsese. Notably, Werner Herzog earned plenty of accolade for his use of 3D to portray cave paintings. For the most part, though, 3D films haven't done much more than look like a cinematic pop-up book — a poor excuse to ask for 10 more dollars at the box office. It's fortunate then that Godard has tried his hand at one and come up with some truly interesting uses for it. Here are three big ways that Godard makes it work.

He actually makes 3D look good

Most 3D films either look almost indistinguishable from 2D, or they don't do much more than apply a basic layering effect between the foreground and the background. Godard, on the other hand, manages to film the world in 3D very much as we see it, using a long depth of field that makes the film’s world extend far into the distance. On top of that, many of the scenes are deeply layered, making the 3D effect more prominent than usual. In one scene, there's a good seven layers from front to back (not counting the actors): a potted plant, a chair, a bike, a barrier, a house, another house, and finally some trees. It’s one of the first times in a 3D film that the image truly looks like it has depth.

Another key aspect is that the film is often rolling at a higher-than-usual framerate. That does give Goodbye to Language something close to the much-dreaded "home video" look, but it's stylized enough with bright colors or contrasting highlights and shadows to not matter so much. The result is some gorgeous imagery that makes me really want to see a nature documentary in 3D.

He mixes 2D and 3D

This may not sound like succeeding at 3D, but it actually leads to a couple of interesting results. For one, it's kind of funny: one of the very first things that you see in the movie is the term "2D" printed in 2D with the term "3D" hovering over it in 3D. It's a little inexplicable, but it's sort of a necessary joke to get you in the mindset for this film.

The more interesting use of 2D, though, is when archival footage (or, at least, what looks to be archival footage) is interspersed with the newly shot 3D footage in the film. In many ways, this is a modernized equivalent to cutting back to a black-and-white flashback. The fact that it's 2D lets us know that it's out of the modern narrative.

He totally messes with your vision

Sometimes the 3D in Goodbye to Language looks crisp, clean, and downright gorgeous. Other times, it'll drive you cross-eyed — and that's exactly what Godard wants to do.

In what's easily the coolest use of 3D in this film, Godard actually splits the image in two. 3D movies are normally shot with two cameras that remain perfectly side-by-side, one capturing an image for your left eye, the other capturing an image for your right eye. But in two scenes of Goodbye to Language, Godard has the left camera remain stationary, pointed at an unmoving character, while the right camera pans to the side to follow another person's movements.

At first, you have no idea what's going on — your eyes twist in pain, you lift your 3D glasses up in confusion. Then, suddenly, you see it: close one eye, and you see 2D action of the character on the left; close the other eye, and you see 2D action of the character on the right; leave both eyes open, and the images play on top of one another, fighting for your attention and only letting you ever really see their essence. Ultimately, Godard has the two cameras rejoin again, completing the picture and relieving you of discomfort.

It's actually kind of uncomfortable to watch this film

That type of discomfort is used throughout the film in other ways as well. In many situations, the two cameras will be positioned slightly too far apart, once again turning your vision cross-eyed. Alternatively, it means that you can shut one eye and see farther around a corner than you might otherwise have seen. (In a maddening twist, this distortion effect even stretches over to the film's English subtitles on occasion.) One of the more clever uses is when this distortion occurs between two characters on either side of the screen, essentially creating a schism between them that twists your eyesight when you try to look. It makes for a very evocative separation between the two characters — a separation that’s so tangible you can quite literally feel it.

These are obviously not all techniques that should be used by most (if any) mainstream films, but they turn 3D into much more of a marvel than it currently is. If all movies are going to be 3D one day, it'd be pretty disappointing if directors never figure out novel ways for using it to tell a story — and Godard is, unsurprisingly, quick to search for something new. This film is called Goodbye to Language, and you have to wonder: perhaps this is an ode to the end of one cinematic language, and the greeting of another.

-

Goodbye to Language is currently screening at the New York Film Festival. It opens in theaters on October 29th.

Wednesday, April 02. 2014

Why Her will dominate UI design ... (as an anti Minority Report) | #interaction #interface #ai

Via Wired

-----

The future we see in Her is one where technology has dissolved into everyday life.

A few weeks into the making of Her, Spike Jonze’s new flick about romance in the age of artificial intelligence, the director had something of a breakthrough. After poring over the work of Ray Kurzweil and other futurists trying to figure out how, exactly, his artificially intelligent female lead should operate, Jonze arrived at a critical insight: Her, he realized, isn’t a movie about technology. It’s a movie about people. With that, the film took shape. Sure, it takes place in the future, but what it’s really concerned with are human relationships, as fragile and complicated as they’ve been from the start.

Of course on another level Her is very much a movie about technology. One of the two main characters is, after all, a consciousness built entirely from code. That aspect posed a unique challenge for Jonze and his production team: They had to think like designers. Assuming the technology for AI was there, how would it operate? What would the relationship with its “user” be like? How do you dumb down an omniscient interlocutor for the human on the other end of the earpiece?

For production designer KK Barrett, the man responsible for styling the world in which the story takes place, Her represented another sort of design challenge. Barrett’s previously brought films like Lost in Translation, Marie Antoinette, and Where the Wild Things Are to life, but the problem here was a new one, requiring more than a little crystal ball-gazing. The big question: In a world where you can buy AI off the shelf, what does all the other technology look like?

Technology Shouldn’t Feel Like Technology

One of the first things you notice about the “slight future” of Her, as Jonze has described it, is that there isn’t all that much technology at all. The main character Theo Twombly, a writer for the bespoke love letter service BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com, still sits at a desktop computer when he’s at work, but otherwise he rarely has his face in a screen. Instead, he and his fellow future denizens are usually just talking, either to each other or to their operating systems via a discrete earpiece, itself more like a fancy earplug anything resembling today’s cyborgian Bluetooth headsets.

In this “slight future” world, things are low-tech everywhere you look. The skyscrapers in this futuristic Los Angeles haven’t turned into towering video billboards a la Blade Runner; they’re just buildings. Instead of a flat screen TV, Theo’s living room just has nice furniture.

This is, no doubt, partly an aesthetic concern; a world mediated through screens doesn’t make for very rewarding mise en scene. But as Barrett explains it, there’s a logic to this technological sparseness. “We decided that the movie wasn’t about technology, or if it was, that the technology should be invisible,” he says. “And not invisible like a piece of glass.” Technology hasn’t disappeared, in other words. It’s dissolved into everyday life.

Here’s another way of putting it. It’s not just that Her, the movie, is focused on people. It also shows us a future where technology is more people-centric. The world Her shows us is one where the technology has receded, or one where we’ve let it recede. It’s a world where the pendulum has swung back the other direction, where a new generation of designers and consumers have accepted that technology isn’t an end in itself–that it’s the real world we’re supposed to be connecting to. (Of course, that’s the ideal; as we see in the film, in reality, making meaningful connections is as difficult as ever.)

Theo still has a desktop display at work and at home, but elsewhere technology is largely invisible.

Jonze had help in finding the contours of this slight future, including conversations with designers from New York-based studio Sagmeister & Walsh and an early meeting with Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, principals at architecture firm DS+R. As the film’s production designer, Barrett was responsible for making it a reality.

Throughout that process, he drew inspiration from one of his favorite books, a visual compendium of futuristic predictions from various points in history. Basically, the book reminded Barrett what not to do. “It shows a lot of things and it makes you laugh instantly, because you say, ‘those things never came to pass!’” he explains. “But often times, it’s just because they over-thought it. The future is much simpler than you think.”

That’s easy to say in retrospect, looking at images of Rube Goldbergian kitchens and scenes of commute by jet pack. But Jonze and Barrett had the difficult task of extrapolating that simplification forward from today’s technological moment.

Theo’s home gives us one concise example. You could call it a “smart house,” but there’s little outward evidence of it. What makes it intelligent isn’t the whizbang technology but rather simple, understated utility. Lights, for example, turn off and on as Theo moves from room to room. There’s no app for controlling them from the couch; no control panel on the wall. It’s all automatic. Why? “It’s just a smart and efficient way to live in a house,” says Barrett.

Today’s smartphones were another object of Barrett’s scrutiny. “They’re advanced, but in some ways they’re not advanced whatsoever,” he says. “They need too much attention. You don’t really want to be stuck engaging them. You want to be free.” In Barrett’s estimation, the smartphones just around the corner aren’t much better. “Everyone says we’re supposed to have a curved piece of flexible glass. Why do we need that? Let’s make it more substantial. Let’s make it something that feels nice in the hand.”

Theo’s smartphone was designed to be “substantial,” something that first and foremost “feels good in the hand.”

Theo’s phone in the film is just that–a handsome hinged device that looks more like an art deco cigarette case than an iPhone. He uses it far less frequently than we use our smartphones today; it’s functional, but it’s not ubiquitous. As an object, it’s more like a nice wallet or watch. In terms of industrial design, it’s an artifact from a future where gadgets don’t need to scream their sophistication–a future where technology has progressed to the point that it doesn’t need to look like technology.

All of these things contribute to a compelling, cohesive vision of the future–one that’s dramatically different from what we usually see in these types of movies. You could say that Her is, in fact, a counterpoint to that prevailing vision of the future–the anti-Minority Report. Imagining its world wasn’t about heaping new technology on society as we know it today. It was looking at those places where technology could fade into the background, integrate more seamlessly. It was about envisioning a future, perhaps, that looked more like the past. “In a way,” says Barrett, “my job was to undesign the design.”

The Holy Grail: A Discrete User Interface

The greatest act of undesigning in Her, technologically speaking, comes with the interface used throughout the film. Theo doesn’t touch his computer–in fact, while he has a desktop display at home and at work, neither have a keyboard. Instead, he talks to it. “We decided we didn’t want to have physical contact,” Barrett says. “We wanted it to be natural. Hence the elimination of software keyboards as we know them.”

Again, voice control had benefits simply on the level of moviemaking. A conversation between Theo and Sam, his artificially intelligent OS, is obviously easier for the audience to follow than anything involving taps, gestures, swipes or screens. But the voice-based UI was also a perfect fit for a film trying to explore what a less intrusive, less demanding variety of technology might look like.

Indeed, if you’re trying to imagine a future where we’ve managed to liberate ourselves from screens, systems based around talking are hard to avoid. As Barrett puts it, the computers we see in Her “don’t ask us to sit down and pay attention” like the ones we have today. He compares it to the fundamental way music beats out movies in so many situations. Music is something you can listen to anywhere. It’s complementary. It lets you operate in 360 degrees. Movies require you to be locked into one place, looking in one direction. As we see in the film, no matter what Theo’s up to in real life, all it takes to bring his OS into the fold is to pop in his ear plug.

Looking at it that way, you can see the audio-based interface in Her as a novel form of augmented reality computing. Instead of overlaying our vision with a feed, as we’ve typically seen it, Theo gets a one piped into his ear. At the same time, the other ear is left free to take in the world around him.

Barrett sees this sort of arrangement as an elegant end point to the trajectory we’re already on. Think about what happens today when we’re bored at the dinner table. We check our phones. At the same time, we realize that’s a bit rude, and as Barrett sees it, that’s one of the great promises of the smartwatch: discretion.

“They’re a little more invisible. A little sneakier,” he says. Still, they’re screens that require eyeballs. Instead, Barrett says, “imagine if you had an ear plug in and you were getting your feed from everywhere.” Your attention would still be divided, but not nearly as flagrantly.

Of course, a truly capable voice-based UI comes with other benefits. Conversational interfaces make everything easier to use. When every different type of device runs an OS that can understand natural language, it means that every menu, every tool, every function is accessible simply by requesting it.

That, too, is a trend that’s very much alive right now. Consider how today’s mobile operating systems, like iOS and ChromeOS, hide the messy business of file systems out of sight. Theo, with his voice-based valet as intermediary, is burdened with even less under-the-hood stuff than we are today. As Barrett puts it: “We didn’t want him fiddling with things and fussing with things.” In other words, Theo lives in a future where everything, not just his iPad, “just works.”

AI: the ultimate UX challenge

The central piece of invisible design in Her, however, is that of Sam, the artificially intelligent operating system and Theo’s eventual romantic partner. Their relationship is so natural that it’s easy to forget she’s a piece of software. But Jonze and company didn’t just write a girlfriend character, label it AI, and call it a day. Indeed, much of the film’s dramatic tension ultimately hinges not just on the ways artificial intelligence can be like us but the ways it cannot.

Much of Sam’s unique flavor of AI was written into the script by Jonze himself. But her inclusion led to all sorts of conversations among the production team about the nature of such a technology. “Anytime you’re dealing with trying to interact with a human, you have to think of humans as operating systems. Very advanced operating systems. Your highest goal is to try to emulate them,” Barrett says. Superficially, that might mean considering things like voice pattern and sensitivity and changing them based on the setting or situation.

Even more quesitons swirled when they considered how an artificially intelligent OS should behave. Are they a good listener? Are they intuitive? Do they adjust to your taste and line of questioning? Do they allow time for you to think? As Barrett puts it, “you don’t want a machine that’s always telling you the answer. You want one that approaches you like, ‘let’s solve this together.’”

In essence, it means that AI has to be programmed to dumb itself down. “I think it’s very important for OSes in the future to have a good bedside manner.” Barrett says. “As politicians have learned, you can’t talk at someone all the time. You have to act like you’re listening.”

AI’s killer app, as we see in the film, is the ability to adjust to the emotional state of its user.

As we see in the film, though, the greatest asset of AI might be that it doesn’t have one fixed personality. Instead, its ability to figure out what a person needs at a given moment emerges as the killer app.

Theo, emotionally desolate in the midst of a hard divorce, is having a hard time meeting people, so Sam goads him into going on a blind date. When Theo’s friend Amy splits up with her husband, her own artificially intelligent OS acts as a sort of therapist. “She’s helping me work through some things,” Amy says of her virtual friend at one point.

In our own world, we may be a long way from computers that are able to sense when we’re blue and help raise our spirits in one way or another. But we’re already making progress down this path. In something as simple as a responsive web layout or iOS 7′s “Do Not Disturb” feature, we’re starting to see designs that are more perceptive about the real world context surrounding them–where or how or when they’re being used. Google Now and other types of predictive software are ushering in a new era of more personalized, more intelligent apps. And while Apple updating Siri with a few canned jokes about her Hollywood counterpart might not amount to a true sense of humor, it does serve as another example of how we’re making technology more human–a preoccupation that’s very much alive today.

Personal comment:

While I do agree with the idea that technology is becoming in some ways banal --or maybe, to use a better word, just common-- and that the future might not be about flying cars, fancy allover hologram interfaces or backup video cities populated with personal clones), that it might be "in service of", will "vanish" or "recede" into our daily atmospheres, environments, architectures, furnitures, clothes if not bodies or cells, we have to keep in mind that this could (will) make it even more intrusive.

When technology won't make debate anymore (when it will be common), when it will be both ambient and invisible, passively accepted if not undergone, then there will be lots of room for ... (gap to be filled by many names) to fulfill their wildest dreams.

We also have to keep in mind that when technology enters an untapped domain (let's say as an example social domain, for the last ten years), it engineers what was, in some cases and before, a common good (you didn't had to pay or trade some data to talk with somebody before). So to say, to engineer common goods (i.e. social relationships, but why not in the future love, air, genome --already the case--, etc.) turns them into products: commodification. Not always a good thing if I could say so... This definitely looks like a goal from the economy: how to turn everything into something you can sell, and information technology is quite good in helping do that.

-

And btw... even so technology might "recede", I'm not so keen with the rather "skeumorph" design of the "ai cell phone" in the movie so far (haven't seen the movie yet)..;). and oh my, I definitely hope this won't be our future. It looks like a Jobs design!

Tuesday, February 25. 2014

Top 10 future cities in film | #fiction

Via the guardian

-----

Is our urban future bright or bleak? Peter Bradshaw provides a selection of celluloid cities you might consider moving to - or avoiding - if you are looking to relocate any time in the next 200 years or so.

METROPOLIS (1927) (dir. Fritz Lang)

Metropolis is the architectural template for all futurist cities in the movies. It has glitzy skyscrapers; it has streets crowded with folk who swarm through them like ants; most importantly, it has high-up freeways linking the buildings, criss-crossing the sky, on which automobiles and trains casually run — the sine qua non of the futurist city. Metropolis is a gigantic 21st-century European city state, a veritable utopia for that elite few fortunate enough to live above ground in its gleaming urban spaces. But it’s awful for the untermensch race of workers who toil underground. Photograph: Ronald Grant Archive.

ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK (1981) (dir. John Carpenter)

Made when New York still had its tasty crime-capital reputation, Carpenter’s dystopian sci-fi presents us with the New York of the future, ie 1988, and imagines that the authorities have given up policing it entirely and simply walled the city off and established a 24/7 patrol for the perimeter, re-purposing the city as a licensed hellhole of Darwinian violence into which serious prisoners will just be slung and then forgotten about, to survive or not as they can. Then in 1997 the President’s plane goes down in the city and he has to be rescued. New York is re-imagined as a lawless, dimly-lit nightmare. Not a great place to live. Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext/MGM.

LOGAN’S RUN (1976) (dir. Michael Anderson) This is set in an enclosed dome city in the post-apocalyptic world of 2274. It looks like an exciting, go-ahead place to live and it’s certainly a great city for twentysomethings. There are the much-loved overhead monorails and people wear the sleek, figure-hugging leotards, unitards, and miniskirts. The issue is that people here get killed on their 30th birthday. Some people escape the dome city to find themselves in deserted Washington DC, which is a wreck by comparison. Photograph: Ronald Grant Archive

BLADE RUNNER (1982) (dir. Ridley Scott)

This film presents us with Los Angeles 2019, a daunting megalopolis in which “replicants” may be hiding out — that is, super-sophisticated organically correct servant-robots indistinguishable from actual humans, who have defied the rules forbidding them to enter the city. Special cops called “blade runners” have to hunt them down. The city is colossal, headspinningly big, a virtual planet itself; it is cursed with terrible weather, with very rainy nights, but interestingly hints at the economic and cultural might of Asia with loads of billboard ads from the Far East. Again, the crime figures may make this city a bit of a no-no. Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext/Warner Bros.

ALPHAVILLE (1965) (dir. Jean-Luc Godard)

Alphaville is a city on a distant planet and a very grim place, subject to Orwellian repression and thought-control by its tyrannical ruler, an AI computer called Alpha 60. The city is seen largely at night, with drab buildings which have neither the techno-futurist furniture nor the obvious decay that you expect from sci-fi dystopia. This is because it was filmed in 1960s inner-city Paris: Alphaville is the French capital’s intergalactic banlieue twin-town. Again, this isn’t a great movie-futurist city to settle down in, although the property prices are probably reasonable. Photograph: British Film Institute.

THINGS TO COME (1936) (dir. William Cameron Menzies)

The state-of-the-urban-art British city of Everytown is here shown, from the year 1940 to 2036. A pleasant place is entirely ruined by a catastrophic war which lasts decades and plunges the city into the familiar future-city mode B: post-apocalyptic chaos. The city is basically rubble and hideous gas and poison warfare have made matters worse. Cynical and ambitious types aspire to control Everytown, but the place has been made the nexus for human vanity and ambition. Another future city with a bad reputation. Photograph: ITV/REX

AKIRA (1988) (dir. Katsuhiro Otomo)

Neo-Tokyo, 2019. This gigantic city is like an impossibly huge sentient robot life-form in itself. It was built to replace the “old” Tokyo which was immolated in a huge explosion. Now the new city is a teeming, prosperous, hi-tech place but more than a little anarchic and strange, always apparently on the verge of breaking down, and also incubating weird spiritual forces. Biker gangs do battle there: the Capsules versus the Clowns. An exciting place to settle down — seen in the right light.

SLEEPER (1973) (dir. Woody Allen)

Greenwich Village in 2173 is a startling place: part of the 22nd-century police state in which the people are kept in a placid condition with brainwashing. A nerdy bespectacled health-food-store owner, who has been cryogenically frozen in 1973 and awakened into this brave new world, must now battle against the forces of mind-control. This Huxleyan futureworld actually looks rather pleasant, the architecture, décor and public transport are all not bad, and these are cities with “Orgasmatrons” which are guaranteed to give sexual satistfaction to those inside them. Photograph: Ronald Grant Archive

MINORITY REPORT (2002) (dir. Steven Spielberg)

Washington in the year 2054 is eerie and disorientating: a shadowy, noir-y city which appears often to be underlit, and yet it certainly enjoys the benefits of the digital revolution. Moving posters are the norm (actually, they’re commonplace in cities now) and images, text and data on screens can be manipulated with extraordinary ease. The populace is policed by a specialist unit called “PreCrime” which can predict and pre-empt the lawbreakers, but their prophetic dominance has created a spiritual malaise in the city’s atmosphere.

BABELDOM (2013) (dir. Paul Bush) This cult cine-essay by Paul Bush is all about a fictional mega-city called Babeldom. Where this city is supposed to be is a moot point. It is everywhere and nowhere. At first it is glimpsed through a misty fog: it is the city of Babel imagined by the elder Breughel in his Tower Of Babel. Then Bush gives us glimpses of a place made up of actual cities and then computer graphic displays take us through how a city develops its distinctive lineaments and growth patterns. Of all the future-cities on this list, Babeldom is probably the weirdest.

This article was amended on 30 January 2014 to correct the spelling of Paul Bush's name.

Wednesday, November 06. 2013

The Making of an Avant Garde | #architecture #theory

Via The Architectural League NY

-----

The Making of an Avant Garde, film still, 2012

The Making of an Avant Garde: The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies 1967-1984

A documentary written, produced, and directed by Diana Agrest

1.5 AIA and New York State CEUs

This film screening is organized by The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture of The Cooper Union and co-sponsored by The Architectural League.

A screening of The Making of an Avant Garde: The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies 1967-1984.

The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, founded in 1967 with close ties to The Museum of Modern Art, made New York the global center for architectural debate and redefined architectural discourse in the United States. A place of immense energy and effervescence, its founders and participants were young and hardly known at the time but would ultimately shape architectural practice and theory for decades. Diana Agrest’s film documents and explores the Institute’s fertile beginnings and enduring significance as a locus for the avant-garde. The film features Mark Wigley, Peter Eisenman, Diana Agrest, Charles Gwathmey, Mario Gandelsonas, Richard Meier, Kenneth Frampton, Barbara Jakobson, Frank Gehry, Anthony Vidler, Deborah Berke, Rem Koolhaas, Stan Allen, Suzanne Stephens, Bernard Tschumi, Joan Ockman, among others.

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

7:00 p.m.

The Great Hall

The Cooper Union

7 East 7th Street

This event is free and open to all. Reservations neither needed nor accepted.

Personal comment:

Undoubtedly a documentary I'll look to get a copy!

Thursday, May 03. 2012

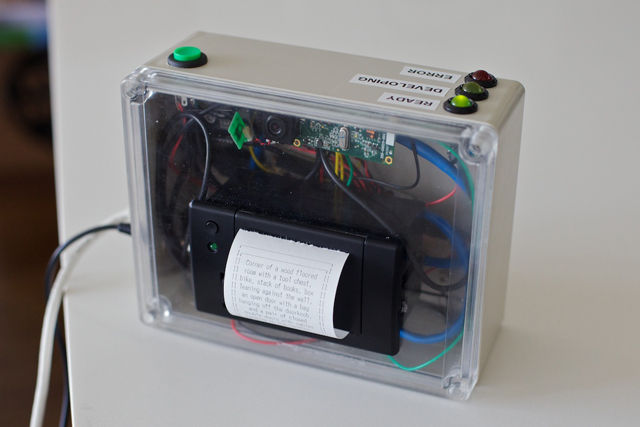

The Descriptive Camera turns your photos into someone else's words

-----

While most camera innovations are aimed at higher megapixel counts or new image capturing techniques, Matt Richardson is taking an entirely different route with the Descriptive Camera: creating a device that turns your captured imagery into words. Designed as part of a class for New York University's Interactive Telecommunications Program, the camera consists of a USB webcam, a shutter button, a small thermal printer, and an ethernet connection. When a picture is "snapped," it's sent off to humans for analysis via Amazon's Mechanical Turk API. The human on the other end then creates a written description of the image, which is sent back to the camera. The resulting text is printed with the thermal printer, framed by a Polaroid-style photo outline (an example Richardson provides reads "It's a dark room with a window. The image is quite pixelated."

According to Richardson's post about the project, the Amazon Human Intelligence Task — or HIT — cost is about $1.25 for each image, with results usually taking between three to six minutes to return. An "accomplice mode" actually lets the camera send out links to the image via instant messenger, providing a cheaper option for human interpretation. While the device currently requires external power from a 5-volt source, Richardson does hope to make a version at some point that runs off self-contained batteries and can use wireless data. It's certainly an interesting project, and we won't deny that we're smitten with the idea of taking images out and about in the world, and seeing them perceived through someone else's eyes.

Related Links:

Friday, April 15. 2011

Places, strange and quiet | Wim Wenders

Via dpr-barcelona

-----

The relationship between architecture and photography is so old as both disciplines. While Anne Elisabeth Toft asks “Is it possible to capture, translate and transmit architectural experience via representations?” we can recall to the most recent work of the filmmaker and artist Wim Wenders, called Places, strange and quiet which is based on a fascinating series of large-scale photographs taken in countries around the world from Salvador, Brazil; Palermo, Italy; Onomichi, Japan to Berlin, Germany; Brisbane, Australia, Armenia and the United States. Wenders pointed on his latest publication:

When you travel a lot, and when you love to just wander around and get lost, you can end up in the strangest spots. I have a huge attraction to places. Already when I look at a map, the names of mountains, villages, rivers, lakes or landscape formations excite me, as long as I don’t know them and have never been there … I seem to have sharpened my sense of place for things that are out of place. Everybody turns right, because that’s where it’s interesting, I turn left where there is nothing! And sure enough, I soon stand in front of my sort of place. I don’t know, it must be some sort of inbuilt radar that often directs me to places that are strangely quiet, or quietly strange.

But what about photographing not buildings, but landscape, urban voids and ruins? Can we talk about the same relationship as in between architecture and photography?

Most of Wim Wenders‘ photographs are created during his personal travels and while location-scouting for his films. From his iconic images of exteriors and buildings to his panoramic depictions of towns and landscapes, it’s not strange to find some of his movies accompanied by photo exhibitions and publications such as The Heart is a Sleeping Beauty as part of The Million Dollar Hotel or his 1999 film Buena Vista Social Club which was featured with the companion book by Wim Wenders and Donata Wenders.

Wim Wenders was a painter before he started working on film and photography, and he talked about this in an interview with Michael Coles:

I was heavily influenced by the so-called New American Underground. A lot of American painters made movies in the mid to late ’60s, Warhol being the most famous one. There was a whole retrospective traveling through Europe at the time. I saw these films in ’66 or ’67, and that was very important for me. I wrote about them, too. I wrote about Michael Snow especially, and a film that he had made called Wavelength (1967). It was the first article I wrote. Wavelength was a painter’s film. It was actually only one shot, a painstakingly slow zoom across a room toward the windows. Day and night were passing. Nothing much happened. It was very painterly. My first films were basically landscape paintings, except that they were shot with a movie camera. I never moved the frame. Nothing ever happened in them. Each scene lasted as long as a 16-millimeter daylight reel, which was about four minutes. There was no editing involved, other than attaching one reel to the other.

Wenders photographic work is obviously very cinematic. His approach to catch the right moment and the right place, his sensibility to transmit with images what a urban place can mean and the way he freezes different urban context is widely poetic and full of literary references.

Wenders points that he doesn’t think that any photographer has anything else in mind than that particular moment he is capturing. This is the main guideline of the photo-work of the exhibition that will take place at the Haunch of Venison, in London.

“…but a story,

from that story came a script,

and from the script a film -

which never wanted to conceal

that it might just as well have become a song:

a song about a different America

beyond that great big Dream,

where truly

everyone

is

equal.”

- Wim Wenders

As he said, “discovering the story that a place wants to tell. That’s my main concern, my attitude. Listening to the place. For me, taking a picture is more an act of listening, so to speak, than of seeing.” Now, the questions hidden in every picture are always the same:

What happened to that place? What happened to those people? How does this house or this street or this landscape look now, 10 or 30 years later?

—–

Image credits:

[1] Ferris Wheel, Armenia 2008, C-Print, 151,3 x 348 cm © Wenders Images GbR

[2] Open Air Screen, Palermo 2007, C-Print, 186×213 cm © Wenders Images GbR

[3] The Red Bench, Onomichi, 2005, C-Print, 186 x 200,6 cm © Wenders Images GbR

[4] Cemetery in the City, Tokyo 2008, C-Print, 132×133 cm © Wenders Images GbR

[5] Moscow Backyard, Moskau 2006, C-Print, 125×139 cm © Wenders Images GbR

[6] Ferris Wheel (Reverse Angle), Armenia 2008, C-Print, 151,3 x 348 cm © Wenders Images GbR

The book Places, strange and quiet has been published by Hatje Cantz Verlag. More info at their web-site

Monday, October 25. 2010

Video: “A Necessary Ruin: The Story of Buckminster Fuller and the Union Tank Car Dome”

Via Archdaily

-----

A Necessary Ruin: The Story of Buckminster Fuller and the Union Tank Car Dome from Evan Mather on Vimeo.

Upon its completion in October 1958, the Union Tank Car Dome, located north of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, was the largest clear-span structure in the world. Based on the engineering principles of the visionary design scientist and philosopher Buckminster Fuller, this geodesic dome was, at 384 feet in diameter, the first large scale example of this building type.

“A Necessary Ruin” tells the history of the Union Tank Car Dome via interviews with architects, engineers, preservationists, media, and artists; animated sequences demonstrating the operation of the facility; and hundreds of rare photographs and video segments taken during the dome’s construction, decline, and demolition.

Visit handcraftedfilms.com for more information and to purchase the DVD.

Related Links:

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.

Quicksearch

Categories

Calendar

|

|

July '25 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||