Sticky Postings

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Wednesday, December 14. 2016

Note: Interférences dimensionnelles 1, a 3d printed work by fabric | ch, becomes part of the online gallery collection ArtJaws. This piece was created at the occasion of an exhibition in Montreal (pdf) and is now edited in a slighty different version and in a limited and certificated serie of 20 pieces. The selection of works by different artists has been curated by Ewen Chardronnet, among a larger collection.

Well... It seems it comes at the perfect time for Christmas! ;)

By fabric | ch

-----

“Cosmos of Mutual Exchanges” is the collection curated by Ewen Chardronnet for the online gallery ArtJaws.

A few words by Ewen about it:

"Throughout my journey as an author, journalist, curator and member of collectives, meeting artists has always been a chance for me to develop my knowledge and theory around speculative fields that go well beyond the fixed borders of academic reflection.

As such, while curating exhibitions, art directing festivals, coordinating residencies and directing productions, I have always sought out a relationship between art practice and theory that, rather than merely being mutually beneficial, leads to a true exchange. I have always felt more enriched working with the artists, rather than simply writing about them. For me, an exhibition is not a final goal but a platform where each player enriches their sensory knowledge and collectively participates in opening up new ways of perceiving and acting in society, faced with our accelerated world. These are the mutual cosmic exchanges that give artworks their “value”… and can help us to rethink our politics of recombinatory commons.

So I took the opportunity of this online curation to revisit a decade of collaborating with artists and to see where this new perspective on mutual exchange (with the gallery, the collector) can lead us. During these years, Slovenian artistic life has been a major source of inspiration for me, and this is expressed in the selection, which is faithful to the community spirit. (...)"

More about the collection HERE.

Regarding the work of fabric | ch in the collection, Interférences dimensionnelles 1:

Created at the occasion of an exhibition in Montreal and revisited for this edition of 20 copies, Interference Dimensionnelle 1 is as a “matrix” in scale 1: X which instantly combines the spatial, temporal or even climatic dimensions/data of actual or virtual terrestrial locations.

Athens, Brasilia, Dubai, intersection of the Arctic Circle and Antemeridian, Montreal: 37 ° 58 ‘N / 23 ° 43’ E; 15 ° 46 ‘N / 47 ° 54’ W; 25 ° 16 ‘N / 55 ° 19’ E; 66 ° 33 ‘N / 180 ° 00’ E; 45 ° 30 ‘N / 73 ° 40’ W.

Five emblematic places representative of the architectural, territorial and energetic approaches of Western society and its history, five coordinates located on a world map and then gathered. These situations, when supplemented by the”original” mark 0,0,0, form a set of six interlaced benchmarks for new contemporary spatial situations.

21 x 18 x 18 cm, transparent and black acrylic polymer, edition of 20. €1200.-

Friday, October 24. 2014

Via BLDGBLOG

-----

Immaterials: Satellite Lamps from Satellite Lamps on Vimeo.

An interesting new project called Satellite Lamps, by Einar Sneve Martinussen, Jørn Knutsen, and Timo Arnall, attempts to visualize the ever-drifting, never exactly accurate workings of GPS.

As the above video shows, the project uses "a set of lamps that contain GPS receivers, that change brightness according to the accuracy of received GPS signals. When we photograph them in timelapse, they reveal how the accuracy changes over time."

You're basically watching the indirect effects of signal drift, transformed here into ambient mood lighting that acts secondarily as a graph of celestial geography.

[Image: From Satellite Lamps].

In what the group calls a "selective history of how a piece of the Space Program has ended up in our pockets," they explain that the everyday reception of signals coming down from the constellation of GPS satellites is always subject to temporary errors, inaccuracies, and misalignments; this can be seen easily enough by glancing at nothing more than your own physical location, as mapped on your cell phone.

They also point to an interesting observation, made by artist James Bridle, that "if you leave a running app such as Nike+ or Runkeeper on your bedside table while you sleep at night, you will wake up to see that the app reports that you ran a significant distance, without doing anything. This, we speculated, is due to the way in which these apps are recording the GPS inaccuracies and counting these as actual, physical movements. In reality, these odd asymmetrical star-shaped tracks offer a map of the shifts of the phone attempting to locate itself."

This ghostly movement is not "real" in any spatial or geographic sense, but it nonetheless leaves digital tracks in our information profiles, like phantom trips being taken by our data-shadows in secret.

[Image: From Satellite Lamps].

So why not visualize this ongoing slippage—these minor tectonics events taking place inside the tools of geography—in a different form, not with, say, an iPhone scooting around all over your neighborhood at night, trying to keep up with the haunted midnight fugues of an errant running app, but with something stationary, something all the more uncanny for the invisible movements that seem to pass through it like an aurora?

This, then, is the point of Satellite Lamps, which flicker and dim to help reveal the invisible glitches in earth-to-satellite coordination, paradoxically unmoving chandeliers that shine in a chiaroscuro of side-effects leaking in from a parallel world.

[Image: From Satellite Lamps].

In any case, the project is voluminously explained and documented. Considering reading about GPS itself, about the team's strategy for giving visual form to invisible information, and, finally, about the physical realization of the lamps.

Wednesday, February 19. 2014

Via Frieze

-----

Fourteen30 Contemporary, Portland

In his video California Bloodlines (GPS Dozen) (all works 2013), California artist Jesse Sugarmann drives through a bright desert expanse in search of somewhere elusive. The camera is trained on the car’s dashboard and windshield, which are festooned with 12 GPS devices that relegate the dramatic landscape of sand and scrub, distant mountains and azure sky to a removed presence. As he drives, a chorus of robotic voices talk over one another, blurting out contradictory directions (‘Turn left!’, ‘Turn right!’, ‘Re-calculating!’). Sugarmann’s intended destination is California City, from which the artist’s exhibition at Fourteen30 Contemporary took its name: a place real enough to have assigned geo-positioning coordinates, yet not real enough for the dozen devices to reach consensus.

Geographically, California City is the third-largest city in the Golden State. Its 40- square-mile grid in the Mojave Desert was developed in the 1960s in tandem with the California Aqueduct, which would transform the arid terrain into a lush, cosmopolitan oasis, a two-hour drive north of Los Angeles. But when the aqueduct was rerouted to the west, development was abandoned. In the ensuing half-century, a population of 15,000 made California City home, leaving the unfinished infrastructure of sidewalks and roads to be slowly reclaimed by the desert. Today, the outskirts of this unrealized city play host to Air Force weapons testing and off-road motor sports.

Symbolically, the site evidences a kind of regional amnesia, in which the glitz and glamour of Southern California’s main cultural centre allows this also-ran destination to fade from collective memory. But Sugarmann leverages its metaphoric impact for more personal ends, using California City as a stage to contemplate his mother’s worsening Alzheimer’s. This place, which bears the fundamental shape of a city but conspicuously lacks the city itself, becomes an analogue for his mother’s frustrated attempts to recall and organize a past she knows exists, but can’t seem to access.

In a second video, California Bloodlines (Parts 1 and 2), the artist has arrived in California City, or at least one of its desolate cul-de-sacs. Joined by an assistant, Sugarmann performs a series of actions addressing the site’s past, present and the irreconcilable divide between them. Initially, they appear as stewards, attempting to restore the road to working condition. They patch a makeshift bonfire pit left by an off-road after-party, sweep sand off the weather-beaten pavement (as desert winds violently undo their efforts), and spread a new layer of asphalt. But with the appearance of a sand dragster, a vehicle equally at home on sand or tarmac, the site’s present-day activities creep in, creating a confused connection to its past: the duo spreads asphalt on the exterior of the dragster and sets it ablaze.

In California Bloodlines (Parts 1 and 2), Sugarmann interpolates scenes of his own ‘weapons testing’ in California City, drawing square-mile development tracts onto Perspex in liquid napalm and burning them into the surface. These works were displayed in the gallery like production stills or outtakes from the film, each image executed in thick black burn marks and feathery yellow flickers. It’s not hard to connect the geometric patterns of the tract with the mapping of the human brain in neuro-imaging techniques.

Sugarmann’s previous body of work focused almost exclusively on cars – as figurative bodies, ‘vehicles’ for projecting human desire and as ubiquitous monuments to the fact of obsolescence and mortality. With the California City videos, this connection between subjects and their automotive stand-ins is made more powerful by the artist’s equation of the landscape with memory. Here, the internal stage of mental function – or in the case of his mother, dysfunction – is depicted in physical, spatial terms. And, tragically, in the enacted folly of restoring unused roads, he illustrates how that which is forgotten can never be recovered.

John Motley

Wednesday, June 19. 2013

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

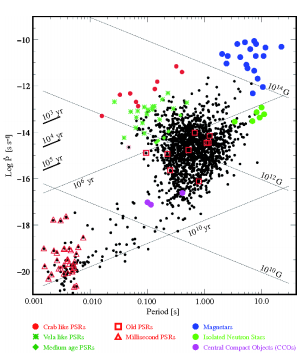

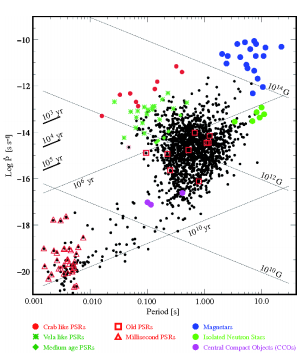

Spacecraft could determine their position anywhere in the solar system to within five kilometres using signals from x-ray pulsars, say astronomers.

Navigating in space is a tricky business. The usual method relies on Earth-based tracking stations to work out a spacecraft’s distance using radio waves, a process that is accurate to within a metre or so.

That’s fine for the radial distance, but tracking a spacecraft’s angular position is much harder because of the limited angular resolution of radio antennas. The current technology produces an uncertainty of about four kilometres per astronomical unit of distance between Earth and the spacecraft.

So for a spacecraft at the distance of Pluto, that’s an uncertainty of 200 kilometres and at the distance of Voyager 1, the uncertainty is 500 kilometres.

So a way for spacecraft to determine their own position accurately would clearly be useful.

Today, Werner Becker at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany and a couple of pals have worked out the practical details for an autonomous spacecraft navigation system using pulsars signals. They say that technology being developed now would allow spacecraft to work out their position to within five kilometres anywhere in the solar system.

The idea of using pulsars to navigate in space dates back several decades. But Becker and co say previous analyses have been hampered by a limited knowledge of pulsars and the relatively bulky technology that has been available to detect them. Both of those things have changed dramatically in recent years.

First, the number of known pulses is growing significantly. Astronomers are aware of well over 2,000 pulsars and the next generation of radio observatories are expected to reveal tens of thousands more.

The basic idea behind this interplanetary navigation system is to use the signals from these pulsars in essentially the same way that we use GPS satellites to navigate on Earth. By measuring the arrival time of pulses from at least three different pulsars and comparing this with their predicted arrival time, it is possible to work out a position in three-dimensional space.

(Since pulsars produce a stream of identical pulses, it is possible to generate any number of ambiguous solutions when doing this. But Becker and co point out that these can be eliminated by constraining the solutions to a finite volume around the assumed position.)

The feasibility of such a system depends on a number of important practical factors, largely determined by the wavelength of the pulsar radiation that the navigation system is designed to detect. This determines the antenna collecting area, the power consumption, the weight of the navigation system, and of course its cost.

Becker and co calculate that for 21-centimeter waves, the spacecraft would require an antenna with a collecting area of 150 square meters.

But a better idea, they say, is to use pulsars that emit x-rays since the technology for collecting and focusing x-rays has improved dramatically in recent years.

One measure of the performance of x-ray mirrors is their mass. The mirror used on the Chandra X-ray Observatory launched in 1999 had a mass of 18.5 tonnes per square metre of effective collecting area. By comparison, the state-of-the-art glass micropore optics being made today have a mass of only 25 kilograms for the same collecting area.

So x-ray optics make good sense for pulsar navigation, say Becker and co. “Using the X-ray signals from millisecond pulsars we estimated that navigation would be possible with an accuracy of ±5 km in the solar system and beyond,” they say.

It may not be necessary to have this accuracy for most missions envisaged in the short term. However Becker and pals are optimistic about its future potential: “It is clear already today that this navigation technique will find its applications in future astronautics.” As they say, to infinity and beyond …

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1305.4842: Autonomous Spacecraft Navigation With Pulsars

Wednesday, April 11. 2012

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

The chip achieves unprecedented accuracy by processing information from many different sensors.

By Christopher Mims

Broadcom has just rolled out a chip for smart phones that promises to indicate location ultra-precisely, possibly within a few centimeters, vertically and horizontally, indoors and out.

The unprecedented accuracy of the Broadcom 4752 chip results from the sheer breadth of sensors from which it can process information. It can receive signals from global navigation satellites, cell-phone towers, and Wi-Fi hot spots, and also input from gyroscopes, accelerometers, step counters, and altimeters.

The variety of location data available to mobile-device makers means that in our increasingly radio-frequency-dense world, location services will continue to become more refined.

In theory, the new chip can even determine what floor of a building you're on, thanks to its ability to integrate information from the atmospheric pressure sensor on many models of Android phones. The company calls abilities like this "ubiquitous navigation," and the idea is that it will enable a new kind of e-commerce predicated on the fact that shopkeepers will know the moment you walk by their front door, or when you are looking at a particular product, and can offer you coupons at that instant.

The integration of new kinds of location data opens up the possibility of navigating indoors, where GPS signals are weak or nonexistent.

Broadcom is already the largest provider of GPS chips to smart-phone makers. Its new integrated circuit relies on sensors that aren't present in every new smart phone, so it won't perform the same in all devices. The new chip, like a number of existing ones, has the ability to triangulate using Wi-Fi hot spots. Broadcom maintains a database of these hot spots for client use, but it says most of its clients maintain their own.

A company that pioneered the construction and maintenance of these kinds of Wi-Fi hot spot databases is SkyHook Wireless. Skyhook CEO Ted Morgan is skeptical that Broadcom can catch up to his company's software-based system allowing for precise indoor location. "Broadcom is just now talking about something we have been doing for seven to eight years, uncovering all the challenges," says Morgan. These include battery management and cataloging a new wave of mobile Wi-Fi hot spots. "Broadcom has never done major deployment," adds Morgan.

Scott Pomerantz, vice president of the GPS division at Broadcom, counters that "the big [mobile] operating systems all have a strategy in place" to create their own Wi-Fi databases. Pomerantz isn't allowed to name names, but one of Broadcom's biggest customers is Apple, which previously used Skyhook for location services in its iPhone but now employs its own, Apple-built location system.

At least one feature of Broadcom's new GPS chip is entirely forward-looking, and integrates data from a source that is not yet commercially deployed: Bluetooth beacons. (Bluetooth is the wireless standard used for short-range communications in devices like wireless keyboards and phone headsets.)

"The use case [for Bluetooth beacons] might be malls," says Pomerantz. "It would be a good investment for a mall to put up a deployment—perhaps put them up every 100 yards, and then unlock the ability for people walking around mall to get very precise couponing information."

"The density of these sensors will give you even finer location," says Charlie Abraham, vice president of engineering at Broadcom. "It could show you where the bananas are within a store—even on which shelf there's a specific brand."

Copyright Technology Review 2012.

Tuesday, March 06. 2012

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

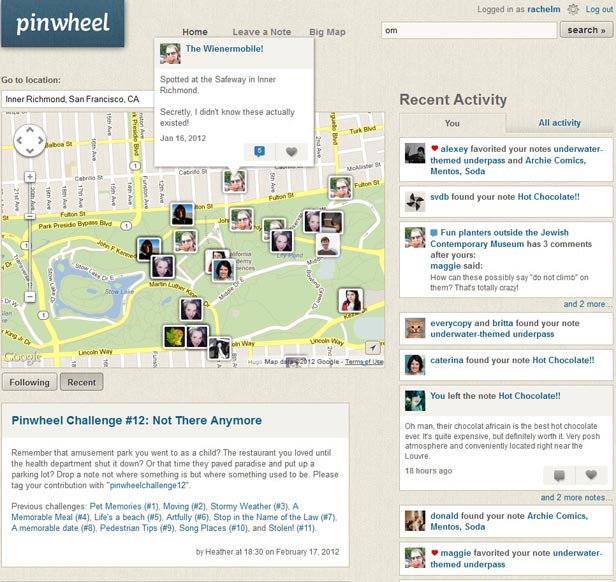

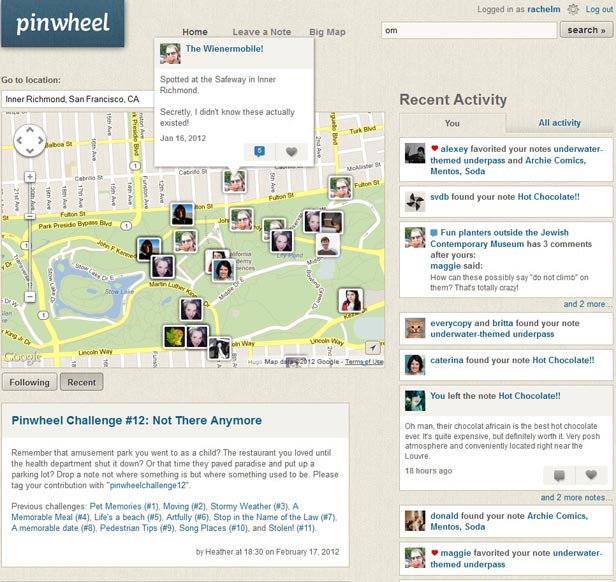

Pinwheel, a new site created by Flickr cofounder Caterina Fake, lets users post virtual notes anywhere.

By Rachel Metz

You've probably left plenty of notes for people in the past—on a kitchen counter, slipped through the slots of a locker, or even scrawled on a bathroom wall. But what if you could leave notes anywhere in the world for anyone to discover, and find ones posted by others?

That's the idea behind Pinwheel, the latest startup from Flickr cofounder Caterina Fake. Though the social site only recently emerged in a private beta testing phase, it's gaining buzz for its simple premise: letting people annotate a map with notes on any topic that can be shared with others.

Fake, a fan of the GPS treasure-hunting activity known as geocaching, says Pinwheel merges several ideas and inspirations. She first began toying with the idea of leaving virtual notes for others to find back in 1999, but the technology wasn't there to support it. And after cofounding Flickr in 2004, she was inspired by users of that site who would annotate satellite maps of their hometowns with notes about various locations. Now, as smart phones have become incredibly popular and location-based apps like Foursquare have blossomed, Fake is confident that the timing is right for Pinwheel, too.

The site's main page—which you need an invitation to see—shows a stream of recently posted notes, and users can browse a map there to check out public notes, leave notes, or search for notes or users.

Navigating the main map is like exploring a visual mash-up of a travel and restaurant guide peppered with memories of first kisses and apartments, event notices, historical facts, and more. There are burger and sushi recommendations, notes about good places to watch the sun set, and tags marking a long-gone movie theater and candy store. One user has been using Pinwheel to log crimes—including the kidnapping and return of Banana Sam, a squirrel monkey belonging to the San Francisco Zoo (now safely returned)—while another is recording historic facts in various cities.

"To me, when you are creating social software, the most exciting part of it is when people start using your tools for things you hadn't expected," Fake says.

At the moment, there is no Pinwheel smart-phone app to help you leave notes on the fly, so users simply log on to the Pinwheel website to do so (there is a mobile site, and Fake says an iPhone app is forthcoming).

Notes can be set as visible to any site user, or just to certain people that you've chosen to follow on the site. Currently, notes can only include text or photos, but Fake says this could eventually expand to audio or video clips as well.

As of early last week, only about 1,000 people were using the site, but Fake says tens of thousands of people have requested invites, and Pinwheel is now sending those out.

Jason Hong, an associate professor at Carnegie Mellon University who studies mobile social technology, sees interesting possibilities for Pinwheel as well as several challenges, including how to gain a critical mass of users and content given the popularity of existing tools like Yelp, Foursquare, and Twitter. "People are still struggling with what, exactly, they're using this for," he says.

Regardless, investors are confident Pinwheel is on to something. The site recently raised $7.5 million in a Series A funding round led by Redpoint Ventures, which added to the $2 million in funding Pinwheel had previously raised. Fake's past success helped, too—photo-sharing site Flickr sold to Yahoo in 2005 and the recommendation engine Hunch, which she also cofounded, sold to eBay in 2011, both for undisclosed amounts.

And, unlike many other Silicon Valley startups, Pinwheel does have a business model: it plans to make money by allowing sponsored notes, something that it's already testing out.

Redpoint partner Geoff Yang says he liked the notion of bringing an offline activity like leaving notes onto the Web, and he sees the site as the combination of social, mobile, and local trends. "I thought the idea was really interesting—the notion that Pinwheel, in many respects, makes places come alive," he says.

Copyright Technology Review 2012.

Personal comment:

An idea (and technology) of annotating the physical world with digital (geolocalized) notes that comes again.

Friday, February 24. 2012

Nick Bilton at the Times’s Bits Blog, hardly a site for speculation on vaporware, tells us to expect something remarkable from Google by the year’s end: heads-up display glasses “that will be able to stream information to the wearer’s eyeballs in real time.”

That’s right. Google’s going to turn us all into the Terminator. Minus the wanton killing, of course.

The Times post builds on the reporting of Seth Weintraub, who blogs at 9 to 5 Google. He had written about the glasses project in December, as well as this month. Weintraub had one tipster, who told him the glasses would look something like Oakley Thumps. Bilton cites “several Google employees familiar with the project,” who said the devices would cost between $250 and $600. The device is reportedly being built in Google’s “X offices,” a top-secret lab that is nonetheless not-top-secret-enough that you and I and other readers of the Times know about it. (X is favored letter for Google of late, when it comes to blue sky projects.)

A few other details about the glasses, that have emerged from either Bilton or Weintraub: they would be Andoid-based and feature a small screen that sits inches from the eye. They’d have access to a 3G or 4G network, and would have motion and GPS sensors. And, in wild, Terminator style, the glasses would even have a low-res camera “that will be able to monitor the world in real time and overlay information about locations, surrounding buildings and friends who might be nearby,” per Bilton. Google co-founder Sergey Brin is reportedly serving as a leader on the project, along with Steve Lee, who made Latitude, Google’s mapping software.

Though reportedly arriving for sale in 2012, the glasses may never reach a mass market. Google is said to be exploring ways to monetize the glasses should consumers take a liking to them. “If consumers take to the glasses when they are released later this year, then Google will explore possible revenue streams,” writes Bilton.

Google isn’t the first to dabble in the idea of heads-up display glasses. Way back in 2002, in fact, we wrote about how electronics could enable augmented reality glasses for soldiers. Though its ambitions are much more modest--hardly anything to hold a candle to The Terminator--a company called 4iiii Innovations has made some basic heads-up display glasses for athletes wanting to monitor their progress. And two years ago, TR took a pair of $2,000 augmented reality glasses from Vuzix for a spin, declaring them “dazzling”--but still wondering, “who’ll wear them?”

I’ve written before that smartwatches could represent a frontier of smartness-on-your-person. “They stand to transform your wrist into something akin to (if a wee bit short of) a heads-up display,” was how I put it. If the information Bilton and Weintraub have on Google is sound, I may have to dial back my enthusiasm on smartwatches--or at least stop likening them to heads-up displays, once the real thing exists.

Then again, smartwatches may still occupy a middle ground between utility and style. On the one hand, Oakley Thump-style smartglasses would be extraordinarily useful, for some. On the other hand, they would also be--let's face it--irredeemably geeky. As Bilton writes, “The glasses are not designed to be worn constantly — although Google expects some of the nerdiest users will wear them a lot.”

If you thought your smartwatch-sporting friend was a geek, just wait till he's flanked by people playing cyborg with Google’s forthcoming technology.

Personal comment:

Well, I'n not so sure if this is a good news... (in fact I don't --I don't like Oakley's...--, unless it would be an open project / open data with a more "design noir" approach), but Terminators will certainly be happy!

Tuesday, February 14. 2012

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

A startup believes combining LED technology and smart-phone apps will offer precise indoor location data.

By Rachel Metz

When you go to the grocery store, chances are you find yourself hunting for at least a couple of items on your list. Wouldn't it be easier if your smart phone could just give you turn-by-turn directions to that elusive can of tomato paste or bunch of cilantro, and maybe even offer you a discount on yogurt, too?

That's the idea behind ByteLight, a Cambridge, Massachusetts-based startup founded by Dan Ryan and Aaron Ganick. ByteLight aims to use LED bulbs—which will fit into standard bulb sockets—as indoor positioning tools for apps that help people navigate places such as museums, hospitals, and stores, and offer deals targeted to a person's location.

Accurate indoor navigation is currently lacking. While GPS is good for finding your way outdoors, it doesn't work as well inside. And technologies being used for indoor positioning, such as Wi-Fi, aren't accurate enough, Ryan and Ganick say.

Ryan and Ganick feel confident they're in the right space at the right time: there's not only been a boom in location-based services, but also in smart-phone apps such as Foursquare or Shopkick that use these services. Meanwhile, LEDs are increasingly popular as replacements for traditional lightbulbs (due to their energy efficiency and long life span).

ByteLight grew out of the National Science Foundation-funded Smart Lighting Engineering Research Center at Boston University, which Ganick and Ryan, both 24, took part in as electrical engineering undergrads.

Initially, ByteLight focused on using LEDs to provide high-speed data communications—a technology referred to as Li-Fi. But Ryan and Ganick felt their technology was better suited to helping people find their way around large indoor spaces.

Here's how it might work: you're in a department store that has replaced a number of its traditional lightbulbs with ByteLights. The lights, flickering faster than the eye can see, would emit a signal to passing smart phones. Your phone would read the signal through its camera, which would direct the smart phone to pull up a deal offering a discount on a shirt on a nearby rack.

While Wi-Fi can only accurately determine your position indoors to within about five to 10 meters, Ryan and Ganick say, ByteLight's technology cuts this down to less than a meter—close enough for you to easily figure out which shirt the deal is referring to.

ByteLight is working on a functioning prototype, and hopes to have the first products available within a year. Ryan and Ganick say a number of developers are working on smart-phone apps that would include the technology, which, they feel, could also work as an additional (or smarter) location-finding feature within existing apps.

The company is talking to retailers about installing its equipment in stores, too. Ryan and Ganick think businesses will warm to ByteLight because installation mainly requires buying and screwing in their lightbulbs. Once a business installs the lights, they'll need to use a ByteLight mobile app to determine which light corresponds to which spot in their building, Ganick says. An app developer could then use that data to tag deals to different lights.

And while LED bulbs are more costly than standard lightbulbs, they've been falling in price. ByteLight says its bulbs will be only "marginally" more expensive than existing LEDs.

Jeffrey Grau, an analyst with digital marketing company eMarketer, believes ByteLight may be on to something. If the customers are already inside a store, showing them an exclusive offer makes it more likely they'll buy something.

But will shoppers find ByteLight's targeting creepy? Ryan and Ganick don't think so. They say an app on your smart phone would be "listening" for nearby ByteLights, not the other way around. So users can control their own experience. And the LED bulbs' positioning capabilities could help people inside a large building solve the common problem of figuring out where they are. "We want people to think about lightbulbs in an entirely new way," Ganick says.

Copyright Technology Review 2012.

Personal comment:

The technology of transmitting bit information through light is known and was used already with neon tubes (or if you look for older technologies, the morse code was already the same technology, but dedicated to the human eye instead of the digital and quick one of a camera), it is now just a shift to combine very rapid variations in lighting (information transmission that remain invisible --to the human eye--) with micro-geo-location.

Thursday, January 27. 2011

Via Change Observer via Dan Hill

-----

By John Thackara

Gram junkies are those fanatical hikers and climbers who fret about every gram of weight that might be carried — in everything from titanium cook pans to toothbrush covers. Excess weight is not just an objective performance issue for these guys; they take it personally. In the matter of mobility and modern transportation, we all need to become gram junkies. We need to obsess not about speed, or about exotic power sources, but about the weight of every step taken, every vehicle used, every infrastructure investment contemplated.

Why? Because modern mobility not only damages the biosphere, our only home, but also global systems of air. Rail and road travel are also greedy in their use of space, matter, energy, biodiversity and land. Designers around the world are busily developing a dazzling array of solutions to deal with these complex challenges. The website Newmobility.org, for example, has identified 177 different projects and approaches to sustainable mobility. These include bus rapid transit (BRT), car free days, demand-responsive transport (DRT), hitch-hiking, pedestrianization, smart parking strategies and van-pooling.

The trouble is that every solution that assumes our current or increased levels of transport intensity, once whole system costs are calculated, turns out not to be viable. Many transport strategies help solve one or two problems — but exacerbate others. The best-known example is the way that the expansion of highways reduces congestion for a time, but tends to increase total vehicle traffic. Another rebound effect: increased vehicle fuel efficiency conserves energy; but, because it reduces vehicle operating costs, it tends to increase total vehicle travel. The growth of the US Interstate Highway System changed fundamental relationships between time, cost and space. These, in turn, enabled forms of economic development that have proved devastating to the biosphere.

Todd Litman, who runs the Victoria Transport Policy Institute in Canada, points out that depreciation, insurance, registration and residential parking are not directly affected by how much a vehicle is driven. Motorists maximize their vehicle travel to get their money’s worth from such expenditures and receive no incentives to drive less. Litman describes these market distortions as "economic traps" in which competition for resources creates conflicts between individual interests and the common good.

The effects of these economic traps are "cumulative and synergistic" in Litman's words: total impact is greater than the sum of individual effects and these distortions skew countless travel decisions and contribute to a long-term cycle of automobile dependency.

Modern mobility kills people too — but without fuss. The total number of people killed on 9/11 was 2,819. And yes, that was a tragedy. But consider this: An average of 3,242 people die worldwide on the roads each day of the year, year after year. Children are especially vulnerable; traffic accident deaths account for 41 percent of all child deaths by injury.

Even if it doesn't kill you outright, modern mobility contributes to poor health. The highest rates of obesity correlate 1:1 with the proportion of journeys children take by car — and the costs of obesity are heading for 10 percent of US GDP. Increased auto dependency and air pollution also contribute to respiratory illnesses, cardiovascular disease and hospital admissions.

We squander time on mobility. We spend the same amount of time traveling today as we did 50 years ago — but we use that time to travel longer distances. The average German citizen today drives 15,000 km (9,320 miles) a year; in 1950, she covered just 2,000 km (1,242 miles). A lot of our travel time is commuting time and work-related travel that we believe we cannot avoid. We also spend a lot of time traveling in order to shop and to take the kids to distant schools.

Even if modern mobility were not a climate change or social problem, the fact that global mobility depends on a finite energy source — oil — means it is fundamentally not resilient. Whether oil and gas are at a peak, or on a plateau, increasing consumption means that the 9 million gallons of gasoline people currently use in the U.S. each day simply will not be availabl in the future. Ninety-five percent of all transportation depends on oil — and with that, food systems in all developed countries are vulnerable to any disruption in the prevailing logistical system.

To a car company, replacing the chrome wing mirror on an SUV with one made of carbon fiber is a step toward sustainable transportation. To a radical ecologist, all motorized movement is unsustainable. So when is transportation sustainable, and when is it not?

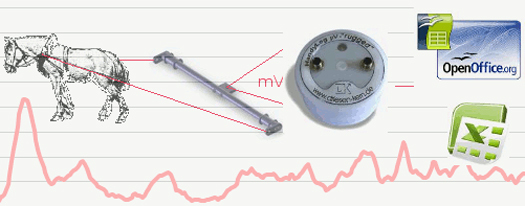

Motorized horse cart featured on the French website Traits en Savoie.

Meterus Horse Power, in France, is modernizing animal traction with an approach that combines technology, ecology, profitability and horse wellness. From Equishop website (Switzerland).

Chris Bradshaw, a transport economist, emphasizes that “light” transport systems are not, per se, sustainable — only less unsustainable than commuting by car. “Light rail supports far-flung suburbs; street cars support, well, street-car suburbs,” Bradshaw says. “A smaller, more efficient, or alternative-fuel vehicle is only less unsustainable than another private vehicle. It will still take up space on the road and in parking lots, it will still threaten the life and limb of others, it will still create noise, and it still will require lots of energy and resources to manufacture, transport to a dealer and dispose of when its life ends.”

Bradshaw wants planners and designers to respect what he calls “the scalar hierarchy.” This is when trips taken most frequently are short enough to be made by walking (even if pulling a small cart), while the next more frequent trips require a bike or street car and so on. “If one adheres to this, then there are so few trips to be made by car, that owning one is foolish.”

Investments in high-speed trains such as they are, is another non-solution. Europeans believe that high-speed trains are environmentally far friendlier than aircraft — but they're not. When researchers at Martin Luther University studied the construction, use and disposal of the high-speed rail infrastructure in Germany, they found that 48 kilograms (about a hundred pounds) of solid primary resources is needed for one passenger to travel 100 kilometers.

China's proposed "straddling" bus would use existing infrastructure to greatly increase capacity along arterial routes.

Is one answer to go by banana boat? Not really. The world's merchant fleet contributes nearly 4.5 percent of all global emissions — a huge amount, up there with cars, housing, agriculture and industry. (Like aviation, shipping emissions are omitted from European targets for cutting global warming.)

Electric cars are the biggest distraction of all. The assumption in European and U.S. policy is that renewable energy-powered smart grids will power millions of electric or hybrid vehicles. Unfortunately, these technology-driven solutions are not viable once the economics of electrical grid modernization are factored in. The German branch of the World Wildlife Foundation (WWF) published a study in May 2009 (conducted with IZES, a German institute for future energy systems). Electric cars only reduce greenhouse gases marginally, they found. The manufacturing processes of both the hybrid and the fully electric car require more energy than those of any conventional petrol-powered car. A worst-case (and frankly most likely) scenario is that most electric cars will be run on electricity from coal instead of from renewable sources.

The least talked about obstacle to electric transportation concerns the raw materials needed to manufacture the vehicles. Rare earth metals are key to global efforts to switch to cleaner energy and therefore transportation. But mining and processing the metals causes immense environmental damage. China’s rare earth industry each year produces more than five times the amount of waste gas, including deadly fluorine and sulfur dioxide, than the total flared annually by all miners and oil refiners in the U.S. Alongside that 13 billion cubic meters of gas is 25 million tons of wastewater laced with cancer-causing heavy metals such as cadmium. And, just as we already have a problem with peak oil, a shortfall looks likely in the world’s capacity to produce lithium. One rare metals expert, William Tahil, claims the production of hybrid and electric cars will soon tax the world’s production of lithium carbonate.

Think More, Move Less

Politicians tend to dissemble or lie, or both, whenever the subject of transportation strategy crops up. Despite proof that transportation damages the biosphere, costs a fortune and kills people, the policy establishment is in thrall to the belief that transportation-enabled economic growth takes priority over all else. This false belief is based on inadequate ecological accounting, and the power of the myriad industries involved. Every aspect of the aviation industry, for example — airplane manufacturers, airlines, airports — is subsidized by direct grants and tax breaks. Remove these hidden subsidies and also charge aviation the true costs of its environmental impact and the whole enterprise becomes un-economic even on its own terms.

Politicians are also scared that no voter will tolerate a curtailment of air travel. The better way to put it is that no rich voter will do so. Only 5 percent of the world’s population has ever flown. Aviation is overwhelmingly an activity of the rich, and strong measures to combat the environmental impact of aviation would not adversely effect poor people.

We once hoped that the internet would replace trips to the mall; that air travel would give way to teleconferencing; and that digital transmission would replace the physical delivery of books and videos. In the event, technology has indeed enabled some of these new kinds of mobility — but in addition to, not as replacements for, the old kinds. The internet has increased transport intensity in the economy as a whole. Rhetoric of a “weightless” economy, the “death of distance” and the “displacement of “matter by mind” sound ridiculous in retrospect.

Rather than tinker with symptoms — such as inventing hydrogen-powered vehicles, or turning gas stations into battery stations — the more interesting and pertinent design task is to re-think the way we use time and space and to reduce the movement of matter — whether goods or people — by changing the word "faster" to "closer."

Our transportation challenge can be compared to distributed computing. The speed-obsessed computer world, in which network designers rail against delays measured in milliseconds, is years ahead of the rest of us in rethinking space-time issues. It can teach us how to rethink relationships between place and time in the real world, too. Embedded on microchips, computer operations entail careful accounting for the speed of light. The problem geeks struggle constantly with is called latency — the delay caused by the time it takes for a remote request to be serviced, or for a message to travel between two processing nodes. Another key word, attenuation, describes the loss of transmitted signal strength as a result of interference — a weakening of the signal as it travels farther from its source — much as the taste of strawberries grown in Spain weakens as they are trucked to faraway places. The brick walls of latency and attenuation prompt computer designers to talk of a “light-speed crisis” in microprocessor design. The clever design solution to the light-speed crisis is to move processors closer to the data — in ecological terms, to re-localize the economy.

Network designers are good localizers. Striving to reduce geodesic distance, they have developed the so-called store-width paradigm or “cache and carry.” They focus on copying, replicating and storing web pages as close as possible to their final destination, at content access points. Thus, if you go online to retrieve a large software update from an online file library, you are often given a choice of countries from which to download it. This technique is called “load balancing” — even though the loads in question, packets of information, don’t actually weigh anything in real-world terms. Cache-and-carry companies maintain tens of thousand of such caches around the world.

By monitoring demand for each item downloaded and making more copies available in its caches when demand rises and fewer when demand falls, operators help to smooth out huge fluctuations in traffic. Other companies combine the cache-and-carry approach with smart file sharing, or "portable shared memory parallel programming." Users’ own computers, anywhere on the internet, are used as shared memory systems so that recently accessed content can be delivered quickly when needed to other users nearby on the network.

The Law of Locality

My favorite example of decentralized production concerns drinks. The weight of beer and other beverages, especially mineral water, trucked from one rich nation to another is a large component of the freight flood that threatens to overwhelm us. But first Coca-Cola and now a boom in microbreweries demonstrate a radically lighter approach: Export the recipe and sometimes the production equipment, but source raw material and distribute locally.

People and information want to be closer. When planning where to put capacity, network designers are guided by the law of locality; this law states that network traffic is at least 80 percent local, 95 percent continental and only 5 percent intercontinental. Communication network designers use another rule that we can learn from in the analogue world: “The less the space, the more the room.” In silicon, the trade-off between speed and heat generated improves dramatically as size diminishes: Small transistors run faster, cooler and cheaper. Hence the development of the so-called processor-in-memory (PIM) — an integrated circuit that contains both memory and logic on the same chip.

So, too, in the analogue world: radically decentralized architectures of production and distribution can radically reduce the material costs of production. We need to build systems that take advantage of the power of networks — but that do so in ways that optimize local-ness.

This design principle — “the less the space, the more the room” — is nowhere better demonstrated than in the human brain. The brain, in Edward O. Wilson's words, is “like one hundred billion squids linked together... an intricately-wired system of nerve cells, each a few millionths of a meter wide, that are connected to other nerve cells by hundreds of thousands of endings. Information transfer in brains is improved when neuron circuits, filling specialized functions, are placed together in clusters.”

Neurobiologists have discovered an extraordinary array of such functions: sensory relay stations, integrative centers, memory modules, emotional control centers, among others. The ideal brain case is spherical or close to it, Wilson observes, because a sphere has the smallest surface relative to volume of any geometric form. A sphere also allows more circuits to be placed close together; the average length of circuits can thus be minimized, which raises the speed of transmission while lowering the energy cost for their construction and maintenance.

Like gram junkies, the mobility dilemma is not as hard to solve as it looks once one replaces the word “speed” with the word “weight.” By changing the success measurement from faster to closer, it becomes possible to borrow from other domains, such as microprocessor design, network topography and the geodesy of the human brain. The biosphere itself is the result of 3.8 billion years of iterative, trial-and-error design — so we can safely assume it’s an optimized solution. As Janine Benyus explains in her wonderful book Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature, biological communities, by and large, are localized or relatively closely connected in time and space. Their energy flux is low, distances covered are proximate. With the exception of a few high-flying species, in other words, “nature does not commute to work.”

Personal comment:

A documented essay from John Thackara about the different forms of mobility and their footprints. With some consideration on the "immobile mobility" or rather "mediated mobility" and an interesting proposal about the "law of locality" taking its inspiration in network computing.

|