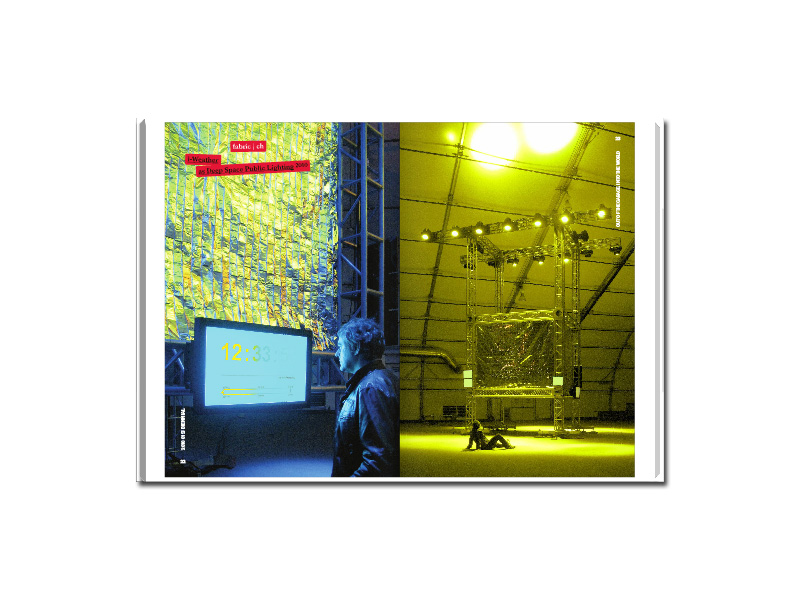

Sticky Postings

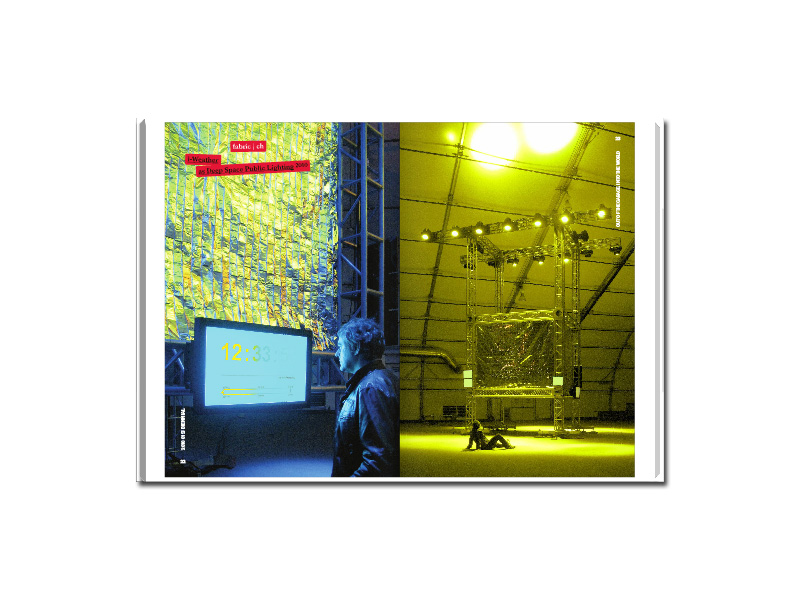

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Thursday, July 31. 2014

Via Archinect

-----

Scientists have discovered that scorpions design their burrows to include both hot and cold spots. A long platform provides a sunny place to warm up before they hunt, whilst a humid chamber acts as a cool refuge during the heat of the day.

This recent discovery of scorpion architecture adds to a sizeable list of impressive non-human architecture.

Anthills consist of a complex network of paths. Comparative to the size of an individual ant, these structures are mega-skyscrapers.

Likewise, termites build huge structures that have been dubbed "cathedrals." Reaching up to 6m high or more, termite cathedrals are clustered in large arrays that cover whole landscapes.

This complex web of branches was built by the vogelkop gardener bowerbird. In direct refutation of the "less is more" aesthetic exemplified by both ants and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, these birds embellish their structures with any bright things they can find.

Primates, including humans, are probably the most avid builders. For example, from an early age, orangutans learn to design and construct elaborately woven nests high in trees.

Far from trivial – and humor aside –, studying animal architectures helps destabilize the normative understanding of architecture as a strictly human domain of activity. Certain studios – like Animal Architecture – both draw inspiration from non-human design and develop collaborative practices with non-humans. Decentering the human as the center of architectural thinking is a necessary step in fostering a deeper understanding of the complex mesh of interconnectedness that is ecology. Without this step, humans will continue to practice architecture without regard for a larger context, which is why the profession already accounts for nearly half of US carbon emissions.

Thursday, July 25. 2013

Via MIT Technology Review via @chrstphggnrd

-----

New tricks will enable a life-logging app called Saga to figure out not only where you are, but what you’re doing.

By Tom Simonite

Having mobile devices closely monitoring our behavior could make them more useful, and open up new business opportunities.

Many of us already record the places we go and things we do by using our smartphone to diligently snap photos and videos, and to update social media accounts. A company called ARO is building technology that automatically collects a more comprehensive, automatic record of your life.

ARO is behind an app called Saga that automatically records every place that a person goes. Now ARO’s engineers are testing ways to use the barometer, cameras, and microphones in a device, along with a phone’s location sensors, to figure out where someone is and what they are up to. That approach should debut in the Saga app in late summer or early fall.

The current version of Saga, available for Apple and Android phones, automatically logs the places a person visits; it can also collect data on daily activity from other services, including the exercise-tracking apps FitBit and RunKeeper, and can pull in updates from social media accounts like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Once the app has been running on a person’s phone for a little while, it produces infographics about his or her life; for example, charting the variation in times when they leave for work in the morning.

Software running on ARO’s servers creates and maintains a model of each user’s typical movements. Those models power Saga’s life-summarizing features, and help the app to track a person all day without requiring sensors to be always on, which would burn too much battery life.

“If I know that you’re going to be sitting at work for nine hours, we can power down our collection policy to draw as little power as possible,” says Andy Hickl, CEO of ARO. Saga will wake up and check a person’s location if, for example, a phone’s accelerometer suggests he or she is on the move; and there may be confirmation from other clues, such as the mix of Wi-Fi networks in range of the phone. Hickl says that Saga typically consumes around 1 percent of a device’s battery, significantly less than many popular apps for e-mail, mapping, or social networking.

That consumption is low enough, says Hickl, that Saga can afford to ramp up the information it collects by accessing additional phone sensors. He says that occasionally sampling data from a phone’s barometer, cameras, and microphones will enable logging of details like when a person walked into a conference room for a meeting, or when they visit Starbucks, either alone or with company.

The Android version of Saga recently began using the barometer present in many smartphones to distinguish locations close to one another. “Pressure changes can be used to better distinguish similar places,” says Ian Clifton, who leads development of the Android version of ARO. “That might be first floor versus third floor in the same building, but also inside a vehicle versus outside it, even in the same physical space.”

ARO is internally testing versions of Saga that sample light and sound from a person’s environment. Clifton says that using a phone’s microphone to collect short acoustic fingerprints of different places can be a valuable additional signal of location, and allow inferences about what a person is doing. “Sometimes we’re not sure if you’re in Starbucks or the bar next door,” says Clifton. “With acoustic fingerprints, even if the [location] sensor readings are similar, we can distinguish that.”

Occasionally sampling the light around a phone using its camera provides another kind of extra signal of a person’s activity. “If you go from ambient light to natural light, that would say to us your context has changed,” says Hickl, and it should be possible for Saga to learn the difference between, say, the different areas of an office.

The end result of sampling light, sound, and pressure data will be Saga’s machine learning models being able to fill in more details of a users’ life, says Hickl. “[When] I go home today and spend 12 hours there, to Saga that looks like a wall of nothing,” he says, noting that Saga could use sound or light cues to infer when during that time at home he was, say, watching TV, playing with his kids, or eating dinner.

Andrew Campbell, who leads research into smartphone sensing at Dartmouth College, says that adding more detailed, automatic life-logging features is crucial for Saga or any similar app to have a widespread impact. “Automatic sensing relieves the user of the burden of inputting lots of data,” he says. “Automatic and continuous sensing apps that minimize user interaction are likely to win out.”

Campbell says that automatic logging coupled with machine learning should allow apps to learn more about users’ health and welfare, too. He recently started analyzing data from a trial in which 60 students used a life-logging app that Campbell developed called Biorhythm. It uses various data collection tricks, including listening for nearby voices to determine when a student is in a conversation. “We can see many interesting patterns related to class performance, personality, stress, sociability, and health,” says Campbell. “This could translate into any workplace performance situation, such as a startup, hospital, large company, or the home.”

Campbell’s project may shape how he runs his courses, but it doesn’t have to make money. ARO, funded by Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen, ultimately needs to make life-logging pay. Hickl says that he has already begun to rent out some of ARO’s technology to other companies that want to be able to identify their users’ location or activities. Aggregate data from Saga users should also be valuable, he says.

“Now we’re getting a critical mass of users in some areas and we’re able to do some trend-spotting,” he says. “The U.S. national soccer team was in Seattle, and we were able to see where activity was heating up around the city.” Hickl says the data from that event could help city authorities or businesses plan for future soccer events in Seattle or elsewhere. He adds that Saga could provide similar insights into many other otherwise invisible patterns of daily life.

Personal comment:

Or how to build up knowledge and minable data from low end "sensors". Finally, how some trivial inputs from low cost sensors can, combined with others, reveal deeper patterns in our everyday habits.

But who's Aro? Who founded it? Who are the "business angels" behind it and what are they up to? What does the technology exactly do? Where are its legal headquarters located (under which law)? That's the first questions you should ask yourself before eventually giving your data to a private company... (I know, this is usual suspects these days). But that's pretty hard to find! CEO is Mr Andy Hickl based in Seattle, having 1096 followers on Twitter and a "Sorry, this page isn't available" on Facebook, you can start to digg from there and mine for him on Google...

-

We are in need of some sort of efficient Creative Commons equivalent for data. But that would be respected by companies. As well as some open source equivalent for Facebook, Google, Dropbox, etc. (but also MS, Apple, etc.), located in countries that support these efforts through their laws and where these "Creative Commons" profiles and data would be implemented. Then, at least, we would have some choice.

In Switzerland, we had a term to describe how the landscape has been progressivily used since the 60ies to build small individual or holiday houses: "mitage du territoire" ("urban sprawl" sounds to be the equivalent in english, but "mitage" is related to "moths" to be precise, so rather ""mothed" landscape" if I could say so, which says what it says) and we had the opportunity to vote against it recently, with success. I believe that now the same thing is happening with personal and/or public sphere, with our lives: it is sprawled or "mothed" by private interests.

So, it is time to ask for the opportunity to "vote" (against it) everybody and have the choice between keeping the ownership of your data, releasing them as public or being paid for them (like a share in the company('s product))!

Friday, May 03. 2013

Via MIT technology Review

-----

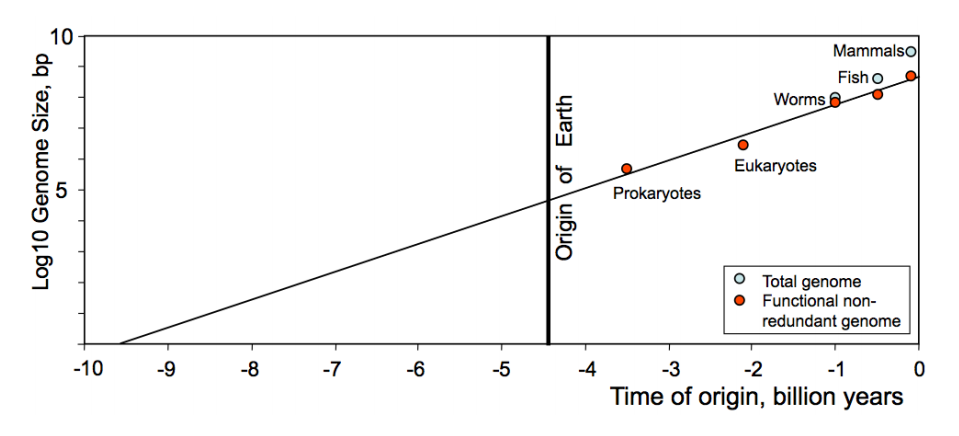

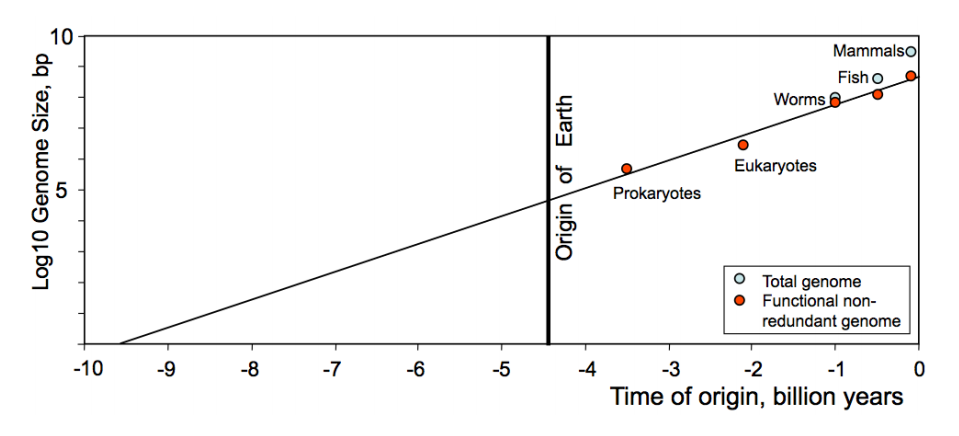

As life has evolved, its complexity has increased exponentially, just like Moore’s law. Now geneticists have extrapolated this trend backwards and found that by this measure, life is older than the Earth itself.

Here’s an interesting idea. Moore’s Law states that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit doubles every two years or so. That has produced an exponential increase in the number of transistors on microchips and continues to do so.

But if an observer today was to measure this rate of increase, it would be straightforward to extrapolate backwards and work out when the number of transistors on a chip was zero. In other words, the date when microchips were first developed in the 1960s.

A similar process works with scientific publications. Between 1990 and 1960, they doubled in number every 15 years or so. Extrapolating this backwards gives the origin of scientific publication as 1710, about the time of Isaac Newton.

Today, Alexei Sharov at the National Institute on Ageing in Baltimore and his mate Richard Gordon at the Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory in Florida, have taken a similar to complexity and life.

These guys argue that it’s possible to measure the complexity of life and the rate at which it has increased from prokaryotes to eukaryotes to more complex creatures such as worms, fish and finally mammals. That produces a clear exponential increase identical to that behind Moore’s Law although in this case the doubling time is 376 million years rather than two years.

That raises an interesting question. What happens if you extrapolate backwards to the point of no complexity–the origin of life?

Sharov and Gordon say that the evidence by this measure is clear. “Linear regression of genetic complexity (on a log scale) extrapolated back to just one base pair suggests the time of the origin of life = 9.7 ± 2.5 billion years ago,” they say.

And since the Earth is only 4.5 billion years old, that raises a whole series of other questions. Not least of these is how and where did life begin.

Of course, there are many points to debate in this analysis. The nature of evolution is filled with subtleties that most biologists would agree we do not yet fully understand.

For example, is it reasonable to think that the complexity of life has increased at the same rate throughout Earth’s history? Perhaps the early steps in the origin of life created complexity much more quickly than evolution does now, which will allow the timescale to be squeezed into the lifespan of the Earth.

Sharov and Gorden reject this argument saying that it is suspiciously similar to arguments that squeeze the origin of life into the timespan outlined in the biblical Book of Genesis.

Let’s suppose for a minute that these guys are correct and ask about the implications of the idea. They say there is good evidence that bacterial spores can be rejuvenated after many millions of years, perhaps stored in ice.

They also point out that astronomers believe that the Sun formed from the remnants of an earlier star, so it would be no surprise that life from this period might be preserved in the gas, dust and ice clouds that remained. By this way of thinking, life on Earth is a continuation of a process that began many billions of years earlier around our star’s forerunner.

Sharov and Gordon say their interpretation also explains the Fermi paradox, which raises the question that if the universe is filled with intelligent life, why can’t we see evidence of it.

However, if life takes 10 billion years to evolve to the level of complexity associated with humans, then we may be among the first, if not the first, intelligent civilisation in our galaxy. And this is the reason why when we gaze into space, we do not yet see signs of other intelligent species.

There’s no question that this is a controversial idea that will ruffle more than a few feathers amongst evolutionary theorists.

But it is also provocative, interesting and exciting. All the more reason to debate it in detail.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1304.3381: Life Before Earth

Tuesday, February 19. 2013

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

A leading neuroscientist says Kurzweil’s Singularity isn’t going to happen. Instead, humans will assimilate machines.

Miguel Nicolelis, a top neuroscientist at Duke University, says computers will never replicate the human brain and that the technological Singularity is “a bunch of hot air.”

“The brain is not computable and no engineering can reproduce it,” says Nicolelis, author of several pioneering papers on brain-machine interfaces.

The Singularity, of course, is that moment when a computer super-intelligence emerges and changes the world in ways beyond our comprehension.

Among the idea’s promoters are futurist Ray Kurzweil, recently hired on at Google as a director of engineering and who has been predicting that not only will machine intelligence exceed our own but that people will be able to download their thoughts and memories into computers (see “Ray Kurzweil Plans to Create a Mind at Google—and Have It Serve You”).

Nicolelis calls that idea sheer bunk. “Downloads will never happen,” Nicolelis said during remarks made at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Boston on Sunday. “There are a lot of people selling the idea that you can mimic the brain with a computer.”

The debate over whether the brain is a kind of computer has been running for decades. Many scientists think it’s possible, in theory, for a computer to equal the brain given sufficient computer power and an understanding of how the brain works.

Kurzweil delves into the idea of “reverse-engineering” the brain in his latest book, How to Create a Mind: The Secret of Human Thought Revealed, in which he says even though the brain may be immensely complex, “the fact that it contains many billions of cells and trillions of connections does not necessarily make its primary method complex.”

But Nicolelis is in a camp that thinks that human consciousness (and if you believe in it, the soul) simply can’t be replicated in silicon. That’s because its most important features are the result of unpredictable, non-linear interactions amongst billions of cells, Nicolelis says.

“You can’t predict whether the stock market will go up or down because you can’t compute it,” he says. “You could have all the computer chips ever in the world and you won’t create a consciousness.”

The neuroscientist, originally from Brazil, instead thinks that humans will increasingly subsume machines (an idea, incidentally, that’s also part of Kurzweil’s predictions).

In a study published last week, for instance, Nicolelis’ group at Duke used brain implants to allow mice to sense infrared light, something mammals can’t normally perceive. They did it by wiring a head-mounted infrared sensor to electrodes implanted into a part of the brain called the somatosensory cortex.

The experiment, in which several mice were able to follow sensory cues from the infrared detector to obtain a reward, was the first ever to use a neural implant to add a new sense to an animal, Nicolelis says.

That’s important because the human brain has evolved to take the external world—our surroundings and the tools we use—and create representations of them in our neural pathways. As a result, a talented basketball player perceives the ball “as just an extension of himself” says Nicolelis.

Similarly, Nicolelis thinks in the future humans with brain implants might be able to sense X-rays, operate distant machines, or navigate in virtual space with their thoughts, since the brain will accommodate foreign objects including computers as part of itself.

Recently, Nicolelis’s Duke lab has been looking to put an exclamation point on these ideas. In one recent experiment, they used a brain implant so that a monkey could control a full-body computer avatar, explore a virtual world, and even physically sense it.

In other words, the human brain creates models of tools and machines all the time, and brain implants will just extend that capability. Nicolelis jokes that if he ever opened a retail store for brain implants, he’d call it Machines“R”Us.

But, if he’s right, us ain’t machines, and never will be.

Monday, January 14. 2013

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

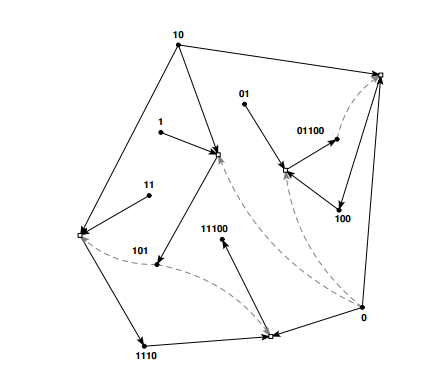

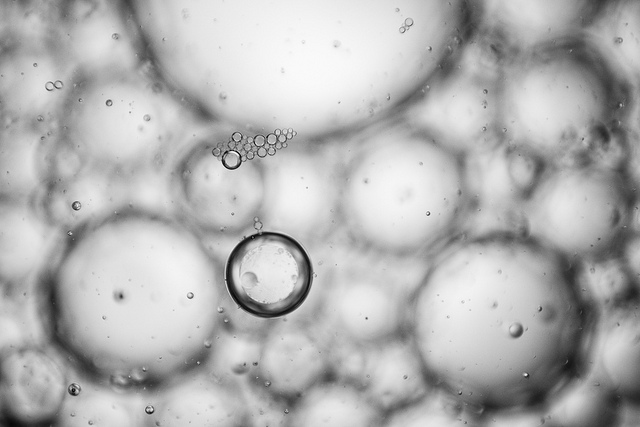

Biochemists have long imagined that autocatalytic sets can explain the origin of life. Now a new mathematical approach to these sets has even broader implications.

One of the most puzzling questions about the origin of life is how the rich chemical landscape that makes life possible came into existence.

This landscape would have consisted among other things of amino acids, proteins and complex RNA molecules. What’s more, these molecules must have been part of a rich network of interrelated chemical reactions which generated them in a reliable way.

Clearly, all that must have happened before life itself emerged. But how?

One idea is that groups of molecules can form autocatalytic sets. These are self-sustaining chemical factories, in which the product of one reaction is the feedstock or catalyst for another. The result is a virtuous, self-contained cycle of chemical creation.

Today, Stuart Kauffman at the University of Vermont in Burlington and a couple of pals take a look at the broader mathematical properties of autocatalytic sets. In examining this bigger picture, they come to an astonishing conclusion that could have remarkable consequences for our understanding of complexity, evolution and the phenomenon of emergence.

They begin by deriving some general mathematical properties of autocatalytic sets, showing that such a set can be made up of many autocatalytic subsets of different types, some of which can overlap.

In other words, autocatalytic sets can have a rich complex structure of their own.

They go on to show how evolution can work on a single autocatalytic set, producing new subsets within it that are mutually dependent on each other. This process sets up an environment in which newer subsets can evolve.

“In other words, self-sustaining, functionally closed structures can arise at a higher level (an autocatalytic set of autocatalytic sets), i.e., true emergence,” they say.

That’s an interesting view of emergence and certainly seems a sensible approach to the problem of the origin of life. It’s not hard to imagine groups of molecules operating together like this. And indeed, biochemists have recently discovered simple autocatalytic sets that behave in exactly this way.

But what makes the approach so powerful is that the mathematics does not depend on the nature of chemistry–it is substrate independent. So the building blocks in an autocatalytic set need not be molecules at all but any units that can manipulate other units in the required way.

These units can be complex entities in themselves. “Perhaps it is not too far-fetched to think, for example, of the collection of bacterial species in your gut (several hundreds of them) as one big autocatalytic set,” say Kauffman and co.

And they go even further. They point out that the economy is essentially the process of transforming raw materials into products such as hammers and spades that themselves facilitate further transformation of raw materials and so on. “Perhaps we can also view the economy as an (emergent) autocatalytic set, exhibiting some sort of functional closure,” they speculate.

Could it be that the same idea–the general theory of autocatalytic sets–can help explain the origin of life, the nature of emergence and provide a mathematical foundation for organisation in economics?

As Kauffman and friends say with just a little understatement: “We believe that these ideas are worth pursuing and developing further.”

We’ll look forward to following the work as it progresses.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1205.0584: The Structure of Autocatalytic Sets: Evolvability, Enablement, and Emergence

Tuesday, November 20. 2012

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

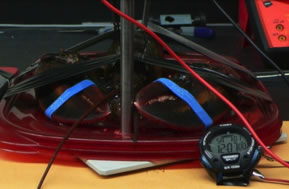

What two crustaceans and a timepiece have to do with the future of medical electronics.

In Evgeny Katz’s vision of the future, medical implants will use the human body as a battery. They’ll just run on the same juice that powers us human beings. His lab at Clarkson University has been building a biofuel cell—an energy harvester--that has successfully drawn electrical energy from glucose coursing the blood streams of snails, clams, and now, lobsters.

Human medical implants powered by what we eat are a long way away, but in a new paper, Katz and his team demonstrate how their technology is maturing towards such a reality. That’s where the lobsters come in. Researchers from Clarkson University and the University of Vermont College of Medicine explain how they’ve powered a watch using glucose from two lobsters, connected as batteries would be, in series. They also show that it’s possible to keep a pacemaker ticking with glucose levels usually seen in the human body.

The key to this setup is an enzyme stationed at implanted electrodes made of carbon nanotubes. Together, the two efficiently convert chemical energy from glucose in an animal’s circulatory system to electricity.

In the past, these energy-harvesting biofuel cells have been tested in the ear of rabbits, in the abdomen of insects, in the body cavity of snails and clams. But the lobsters are different. It’s the first time living organisms have powered up a piece of electronics.

With electrodes in their abdomen, the two lobsters powered the watch for an hour, until the lobsters’ glucose levels near the electrode dropped. (They don’t feel any pain, a member of the team has explained, because they don’t have nerve endings where the electrodes were implanted.) The voltage picked up though, and the crustaceans powered the watch for as long as they remained alive in the lab.

People with pacemakers are ideal bio-battery candidates. As an early test of the idea, the team hooked up a pacemaker to an artificial setup resembling the human circulatory system. It contained serum spiked with glucose at different levels--to represent glucose levels in the blood immediately after you hit the gym, or while sitting at your desk at work, or if you’re diabetic. (Serum is blood with the proteins and cells filtered out.)

With its battery removed, the pacemaker became the first of its kind to run solely on glucose derived from body fluid for five hours. It won’t be the last though, Katz and co. have a list of other medical devices waiting their turn.

Monday, April 02. 2012

-----

de Marion Wagner

A l’heure actuelle la demande en énergie croît plus vite que l’offre. Selon l’Agence internationale de l’énergie, à l’horizon 2030 les besoins de la planète seront difficiles à satisfaire, tous types d’énergies confondus. Il faudra beaucoup de créativité pour satisfaire la demande.

Vincent Schachter, directeur de la recherche et du développement pour les énergies nouvelles à Total commence son exposé sur la biologie de synthèse. “C’est important de préciser dans quel cadre nous travaillons”. Ses chercheurs redessinent le vivant. Ils s’échinent à mettre au point des organismes microscopiques, des bactéries, capables de produire de l’énergie.

En combinant ingénierie, chimie, informatique et biologie moléculaire, les scientifiques recréent la vie.

Ambition démiurgique

Aucune avancée scientifique n’a incarné tant de promesses : détourner des bactéries en usines biologiques capables de produire des thérapeutiques contre le cancer, des biocarburants ou des molécules capables de dégrader des substances toxiques.

Dans la salle Lamartine de l’Assemblée nationale ce 15 février, le parterre de spécialistes invités par l’Office parlementaire d’évaluation des choix scientifique et techniques (OPECST) est silencieux. L’audition publique intitulée Les enjeux de la biologie de synthèse s’attaque à cette discipline jeune, enjeu déjà stratégique. Geneviève Fioraso, députée de l’Isère, qui l’a organisée, confesse : “J’ai des collègues parlementaires à l’Office qui sont biologistes. Ils me disent qu’ils sont parfois dépassés par ce qui est présenté. Ce sont des questions très complexes d’un point de vue scientifique”.

L’Office, dont la mission est “d’informer le Parlement des conséquences des choix de caractère scientifique et technologique afin, notamment, d’éclairer ses décisions” est composé de parlementaires, députés et sénateurs. Dix-huit élus de chaque assemblée qui représentent proportionnellement l’équilibre politique du Parlement. Assistés d’un conseil scientifique ad hoc ils sont saisis des sujets scientifiques contemporains : la sûreté nucléaire en France, les effets sur la santé des perturbateurs endocriniens, les leçons à tirer de l’éruption du volcan Eyjafjöll…

Marc Delcourt, le PDG de la start-up Global Bioenergies, basée à Evry, prend la parole :

La biologie de synthèse, c’est créer des objets biologiques. Nous nous attachons à transformer le métabolisme de bactéries pour leur faire produire à partir de sucres une molécule jusqu’à maintenant uniquement issue du pétrole, et dont les applications industrielles sont énormes.

Rencontré quelques jours plus tard, Philippe Marlière, le cofondateur de l’entreprise, “s’excuse”. Il donne, lui, une définition “assez philosophique” de la biologie de synthèse : ” Pour moi c’est la discipline qui vise à faire des espèces biologiques, ou tout objet biologique, que la nature n’aurait pas pu faire. Ce n’est pas ‘qu’elle n’a pas fait’, c’est ‘qu’elle n’aurait pas pu faire. Il faut que ce soit notre gamberge qui change ce qui se passe dans le vivant”.

Ce bio-chimiste, formé à l’École Normale Supérieure, assume sans fard une ambition de démiurge, il s’agit de créer la vie de manière synthétique pour supplanter la nature. Il ajoute :

Je ne suis pas naturaliste, je ne fais pas partie des gens qui pensent que la nature est harmonieuse et bonne. Au contraire, la biologie de synthèse pose la nature comme imparfaite et propose de l’améliorer .

Aussi provoquant que cela puisse paraître c’est l’objectif affiché et en partie atteint par la centaine de chercheurs qui s’adonne à la discipline depuis 10 ans en France. Il reprend : “Aussi vaste que soit la diversité des gènes à la surface de la terre, les industriels se sont déjà persuadés que la biodiversité naturelle ne suffira pas à procurer l’ensemble des procédés dont ils auront besoin pour produire de manière plus efficace des médicaments ou des biocarburants. Il va falloir que nous nous retroussions les manches et que nous nous occupions de créer de la bio-diversité radicalement nouvelle, nous-mêmes.”

Biologiste-ingénieur

L’évolution sur terre depuis 3 milliard et demi d’années telle que décrite par Darwin est strictement contingente. La sélection naturelle, écrit le prix Nobel de médecine François Jacob dans Le jeu des possibles “opère à la manière d’un bricoleur qui ne sait pas encore ce qu’il va produire, mais récupère tout ce qui lui tombe sous la main, les objets les plus hétéroclites, bouts de ficelle, morceaux de bois, vieux cartons pouvant éventuellement lui fournir des matériaux […] D’une vieille roue de voiture il fait un ventilateur ; d’une table cassée un parasol. Ce genre d’opération ne diffère guère de ce qu’accomplit l’évolution quand elle produit une aile à partir d’une patte, ou un morceau d’oreille avec un fragment de mâchoire”.

Le hasard de l’évolution naturelle, combiné avec la nécessité de l’adaptation a sculpté un monde “qui n’est qu’un parmi de nombreux possibles. Sa structure actuelle résulte de l’histoire de la terre. Il aurait très bien pu être différent. Il aurait même pu ne pas exister du tout”. Philippe Marlière ajoute, laconique : “A posteriori on a toujours l’impression que les choses n’auraient pas pu être autrement, mais c’est faux, le monde aurait très bien pu exister sans Beethoven”.

Cliquer ici pour voir la vidéo.

Comprendre que l’évolution n’a ni but, ni projet. Et la science est sur le point de pouvoir mettre un terme au bricolage inopérant de l’évolution. Le biologiste, ici, est aussi ingénieur. A partir d’un cahier des charges il définit la structure d’un organisme pour lui faire produire la molécule dont il a besoin. Si la biologie de synthèse en est à ses balbutiements, elle est aussi une révolution culturelle.

Il s’agit désormais de créer de nouvelles espèces dont l’existence même est tournée vers les besoins de l’humanité. “La limite à ne pas toucher pour moi c’est la nature humaine. Je suis un opposant acharné au transhumanisme“, met tout de suite en garde le généticien.

A, T, G, C

Depuis que Francis Crick, James Watson et Rosalind Franklin ont identifié l’existence de l’ADN, l’acide désoxyribonucléique, en 1953, une succession de découvertes ont permis de modifier cet l’alphabet du vivant.

On sait désormais lire, répliquer, mais surtout créer un génome et ses gènes, soit en remplaçant certaines de ses parties, soit en le synthétisant entièrement d’après un modèle informatique. Les gènes, quatre bases azotées, A, T, G et C qui se succèdent le long de chacun des deux brins d’ADN pour former la fameuse double hélice, illustre représentation du vivant. Quatre molécules chimiques qui codent la vie : A, pour adénine, T pour thymine, G pour guanine, et C pour cytosine. Leur agencement détermine l’activité du gène, la ou les protéines pour lesquelles il code, qu’il crée. Les protéines, ensuite, déterminent l’action des cellules au sein des organismes vivants : produire des cheveux blonds, des globules blancs, ou des bio-carburants.

On peut à l’heure actuelle, en quelques clics, acheter sur Internet une base azotée pour 30 cents. Un gène de taille moyenne, chez la bactérie, coûte entre 300 et 500 €, il est livré aux laboratoires dans de petits tubes en plastique translucide. Là il est intégré à un génome qui va générer de nouvelles protéines, en adéquation avec les besoins de l’industrie et de l’environnement.

L’être humain est devenu ingénieur du vivant, il peut transformer de simples êtres unicellulaires, levures ou bactéries en de petites usines qu’il contrôle. C’est le bio-entrepreneur américain Craig Venter qui sort la discipline des laboratoires en annonçant en juin 2010 avoir crée Mycoplasma mycoides, une bactérie totalement artificielle “fabriquée à partir de quatre bouteilles de produits chimiques dans un synthétiseur chimique, d’après des informations stockées dans un ordinateur”.

Si la création a été saluée par ses pairs et les médias, certains s’attachent toutefois à souligner que sa Mycoplasma mycoides n’a pas été crée ex nihilo, puisque le génome modifié a été inséré dans l’enveloppe d’une bactérie naturelle. Mais la manipulation est une grande première.

Tour de Babel génétique

Philippe Marlière a posé devant lui un petit cahier, format A5, où après avoir laissé dériver son regard il prend quelques notes. “Il y a longtemps qu’on essaye de changer le vivant en profondeur. Moi c’est l’aspect chimique du truc qui m’intéresse : où faut-il aller piocher dans la table de Mandeleiev pour faire des organismes vivants ? Jusqu’où sont-ils déformables ? Jusqu’à quel point peut-on les lancer dans des mondes parallèles sur terre ?”. Il jette un coup d’œil à son Schweppes :

Prenez l’exemple de l’eau lourde. C’est une molécule d’eau qui se comporte pratiquement comme de l’eau, et on peut forcer des organismes vivants à y vivre et évoluer. Or il n’y a d’eau lourde nulle part dans l’univers, il n’y a que les humains qui savent la concentrer. On peut créer un microcosme complètement artificiel et être sûr que l’évolution qui a lieu là-dedans n’a pas eu lieu dans l’univers. C’est l’évolution dans des conditions qui n’auraient pas pu se dérouler sur terre, c’est intéressant. La biologie de synthèse est une forme radicale d’alter-mondialisme, elle consiste à dire que d’autres vies sont vraiment possibles, en les changeant de fond en comble.

Ce n’est pas une provocation feinte, ce n’est même pas une provocation. L’homme a à cœur d’être bien compris. Il s’agit de venir à bout de l’évolution darwinienne, pathétiquement coincée à un stade qui n’assure plus les besoins en énergie des 10 milliards d’humains à venir. Il faut pour ça réécrire la vie, son code. Innover dans l’alphabet de quatre lettres, A, C, G et T. Créer une nouvelle biodiversité. Condition sine qua non : ces mondes, le nôtre, le naturel, et le nouveau, l’artificiel, devraient cohabiter sans pouvoir jamais échanger d’informations. Il appelle ça la tour de Babel génétique, où les croisements entre espèces seraient impossibles.

“Les écologistes exagèrent souvent, mais ils mettent en garde contre les risques de dissémination génétique et ils ont raison. Les croisements entre espèces vont très loin. J’ai lu récemment que le chat et le serval sont inter-féconds”. Il estime de la main la hauteur du serval, un félin tacheté, proche du guépard, qui vit en Afrique. Un mètre de haut environ.

Par ailleurs il fallait être superstitieux pour imaginer que le pollen des OGM n’allait pas se disséminer. Le pollen sert à la dissémination génétique ! D’où notre projet, il s’agit de faire apparaître des lignées vivantes pour lesquelles la probabilité de transmettre de l’information génétique est nulle.

Le concept tient en une phrase :

“The farther, the safer : plus la vie artificielle est éloignée de celle que nous connaissons, plus les risques d’échanges génétiques entre espèces diminuent. C’est là qu’il y a le plus de brevets et d’hégémonie technologique à prendre.”

Il s’agit de modifier notre alphabet de 4 lettres, A, C, G et T, pour créer un nouvel ADN, le XNA, clé de la “xénobiologie”:

X pour Xeno, étranger, et biologie. Le sens de cet alphabet ne serait pas lisible par les organismes vivants, c’est ça le monde qu’on veut faire. C’est comme lancer un Spoutnik, c’est difficile. Mais comme disait Kennedy, ‘On ne va pas sur la lune parce que c’est facile, on y va parce que c’est difficile.’

Cliquer ici pour voir la vidéo.

Thursday, July 15. 2010

Via fabric | ch

-----

---

|