Sticky Postings

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Monday, April 10. 2017

Note: this "car action" by James Bridle was largely reposted recently. Here comes an additionnal one...

Yet, in the context of this blog, it interests us because it underlines the possibilities of physical (or analog) hacks linked to digital devices that can see, touch, listen or produce sound, etc.

And they are several existing examples of "physical bugs" that come to mind: "Echo" recently tried to order cookies after listening and misunderstanding a american TV ad (it wasn't on Fox news though). A 3d print could be reproduced by listening and duplicating the sound of its printer, and we can now think about self-driving cars that could be tricked as well, mainly by twisting the elements upon which they base their understanding of the environment.

Interesting error potential...

Via Archinect

-----

By Julia Ingalls

James Bridle entraps a self-driving car in a "magic" salt circle. Image: Still from Vimeo, "Autonomous Trap 001."

As if the challenges of politics, engineering, and weather weren't enough, now self-driving cars face another obstacle: purposeful visual sabotage, in the form of specially painted traffic lines that entice the car in before trapping it in an endless loop. As profiled in Vice, the artist behind "Autonomous Trip 001," James Bridle, is demonstrating an unforeseen hazard of automation: those forces which, for whatever reason, want to mess it all up. Which raises the question: how does one effectively design for an impish sense of humor, or a deadly series of misleading markings?

Tuesday, December 23. 2014

Note: while I'm rather against too much security (therefore, not "Imposing security") and probably reticent to the fact that we, as human beings, are "delegating" too far our daily routines and actions to algorithms (which we wrote), this article stresses the importance of code in our everyday life as well as the fact that it goes down to the language which is used to code a program. Interesting to know that some coding languages are more likely to produce mistakes and errors.

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

Computer programmers won’t stop making dangerous errors on their own. It’s time they adopted an idea that makes the physical world safer.

By Simson Garfinkel

Three computer bugs this year exposed passwords, e-mails, financial data, and other kinds of sensitive information connected to potentially billions of people. The flaws cropped up in different places—the software running on Web servers, iPhones, the Windows operating system—but they all had the same root cause: careless mistakes by programmers.

Each of these bugs—the “Heartbleed” bug in a program called OpenSSL, the “goto fail” bug in Apple’s operating systems, and a so-called “zero-day exploit” discovered in Microsoft’s Internet Explorer—was created years ago by programmers writing in C, a language known for its power, its expressiveness, and the ease with which it leads programmers to make all manner of errors. Using C to write critical Internet software is like using a spring-loaded razor to open boxes—it’s really cool until you slice your fingers.

Alas, as dangerous as it is, we won’t eliminate C anytime soon—programs written in C and the related language C++ make up a large portion of the software that powers the Internet. New projects are being started in these languages all the time by programmers who think they need C’s speed and think they’re good enough to avoid C’s traps and pitfalls.

But even if we can’t get rid of that language, we can force those who use it to do a better job. We would borrow a concept used every day in the physical world.

Obvious in retrospect

Of the three flaws, Heartbleed was by far the most significant. It is a bug in a program that implements a protocol called Secure Sockets Layer/Transport Layer Security (SSL/TLS), which is the fundamental encryption method used to protect the vast majority of the financial, medical, and personal information sent over the Internet. The original SSL protocol made Internet commerce possible back in the 1990s. OpenSSL is an open-source implementation of SSL/TLS that’s been around nearly as long. The program has steadily grown and been extended over the years.

Today’s cryptographic protocols are thought to be so strong that there is, in practice, no way to break them. But Heartbleed made SSL’s encryption irrelevant. Using Heartbleed, an attacker anywhere on the Internet could reach into the heart of a Web server’s memory and rip out a little piece of private data. The name doesn’t come from this metaphor but from the fact that Heartbleed is a flaw in the “heartbeat” protocol Web browsers can use to tell Web servers that they are still connected. Essentially, the attacker could ping Web servers in a way that not only confirmed the connection but also got them to spill some of their contents. It’s like being able to check into a hotel that occasionally forgets to empty its rooms’ trash cans between guests. Sometimes these contain highly valuable information.

Heartbleed resulted from a combination of factors, including a mistake made by a volunteer working on the OpenSSL program when he implemented the heartbeat protocol. Although any of the mistakes could have happened if OpenSSL had been written in a modern programming language like Java or C#, they were more likely to happen because OpenSSL was written in C.

Many developers design their own reliability tests and then run the tests themselves. Even in large companies, code that seems to work properly is frequently not tested for lurking flaws.

Apple’s flaw came about because some programmer inadvertently duplicated a line of code that, appropriately, read “goto fail.” The result was that under some conditions, iPhones and Macs would silently ignore errors that might occur when trying to ascertain the legitimacy of a website. With knowledge of this bug, an attacker could set up a wireless access point that might intercept Internet communications between iPhone users and their banks, silently steal usernames and passwords, and then reëncrypt the communications and send them on their merry way. This is called a “man-in-the-middle” attack, and it’s the very sort of thing that SSL/TLS was designed to prevent.

Remarkably, “goto fail” happened because of a feature in the C programming language that was known to be problematic before C was even invented! The “goto” statement makes a computer program jump from one place to another. Although such statements are common inside the computer’s machine code, computer scientists have tried for more than 40 years to avoid using “goto” statements in programs that they write in so-called “high-level language.” Java (designed in the early 1990s) doesn’t have a “goto” statement, but C (designed in the early 1970s) does. Although the Apple programmer responsible for the “goto fail” problem could have made a similar mistake without using the “goto” statement, it would have been much less probable.

We know less about the third bug because the underlying source code, part of Microsoft’s Internet Explorer, hasn’t been released. What we do know is that it was a “use after free” error: the program tells the operating system that it is finished using a piece of memory, and then it goes ahead and uses that memory again. According to the security firm FireEye, which tracked down the bug after hackers started using it against high-value targets, the flaw had been in Internet Explorer since August 2001 and affected more than half of those who got on the Web through traditional PCs. The bug was so significant that the Department of Homeland Security took the unusual step of telling people to temporarily stop running Internet Explorer. (Microsoft released a patch for the bug on May 1.)

Automated inspectors

There will always be problems in anything designed or built by humans, of course. That’s why we have policies in the physical world to minimize the chance for errors to occur and procedures designed to catch the mistakes that slip through.

Home builders must follow building codes, which regulate which construction materials can be used and govern certain aspects of the building’s layout—for example, hallways must reach a minimum width, and fire exits are required. Building inspectors visit the site throughout construction to review the work and make sure that it meets the codes. Inspectors will make contractors open up walls if they’ve installed them before getting the work inside inspected.

The world of software development is completely different. It’s common for developers to choose the language they write in and the tools they use. Many developers design their own reliability tests and then run the tests themselves! Big companies can afford separate quality–assurance teams, but many small firms go without. Even in large companies, code that seems to work properly is frequently not tested for lurking security flaws, because manual testing by other humans is incredibly expensive—sometimes more expensive than writing the original software, given that testing can reveal problems the developers then have to fix. Such flaws are sometimes called “technical debt,” since they are engineering costs borrowed against the future in the interest of shipping code now.

The solution is to establish software building codes and enforce those codes with an army of unpaid inspectors.

Crucially, those unpaid inspectors should not be people, or at least not only people. Some advocates of open-source software subscribe to the “many eyes” theory of software development: that if a piece of code is looked at by enough people, the security vulnerabilities will be found. Unfortunately, Heartbleed shows the fallacy in this argument: though OpenSSL is one of the most widely used open-source security programs, it took paid security engineers at Google and the Finnish IT security firm Codenomicon to find the bug—and they didn’t find it until two years after many eyes on the Internet first got access to the code.

Instead, this army of software building inspectors should be software development tools—the programs that developers use to create programs. These tools can needle, prod, and cajole programmers to do the right thing.

This has happened before. For example, back in 1988 the primary infection vector for the world’s first Internet worm was another program written in C. It used a function called “gets()” that was common at the time but is inherently insecure. After the worm was unleashed, the engineers who maintained the core libraries of the Unix operating system (which is now used by Linux and Mac OS) modified the gets() function to make it print the message “Warning: this program uses gets(), which is unsafe.” Soon afterward, developers everywhere removed gets() from their programs.

The same sort of approach can be used to prevent future bugs. Today many software development tools can analyze programs and warn of stylistic sloppiness (such as the use of a “goto” statement), memory bugs (such as the “use after free” flaw), or code that doesn’t follow established good-programming standards. Often, though, such warnings are disabled by default because many of them can be merely annoying: they require that code be rewritten and cleaned up with no corresponding improvement in security. Other bug–finding tools aren’t even included in standard development tool sets but must instead be separately downloaded, installed, and run. As a result, many developers don’t even know about them, let alone use them.

To make the Internet safer, the most stringent checking will need to be enabled by default. This will cause programmers to write better code from the beginning. And because program analysis tools work better with modern languages like C# and Java and less well with programs written in C, programmers should avoid starting new projects in C or C++—just as it is unwise to start construction projects using old-fashioned building materials and techniques.

Programmers are only human, and everybody makes mistakes. Software companies need to accept this fact and make bugs easier to prevent.

Simson L. Garfinkel is a contributing editor to MIT Technology Review and a professor of computer science at the Naval Postgraduate School.

Tuesday, February 04. 2014

Via Creative Applications

-----

By Lauren McCarthy & Kyle McDonald

AIT (“Social Hacking”), taught for the first time this semester by Lauren McCarthy and Kyle McDonald at NYU’s ITP, explored the structures and systems of social interactions, identity, and self representation as mediated by technology. The semester was spent developing projects that altered or disrupted social space in an attempt to reveal existing patterns or truths about our experiences and technologies, and possibilities for richer interactions.

The class began by exploring the idea of “social glitch”, drawing on ideas from glitch theory, social psychology, and sociology, including Harold Garfinkel’s breaching experiments, Stanley Milgram’s subway experiments, and Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical analysis of social interaction. If “glitch” describes when a system breaks down and reveals something about its structure or self in the process, what might this look like in the context of social space?

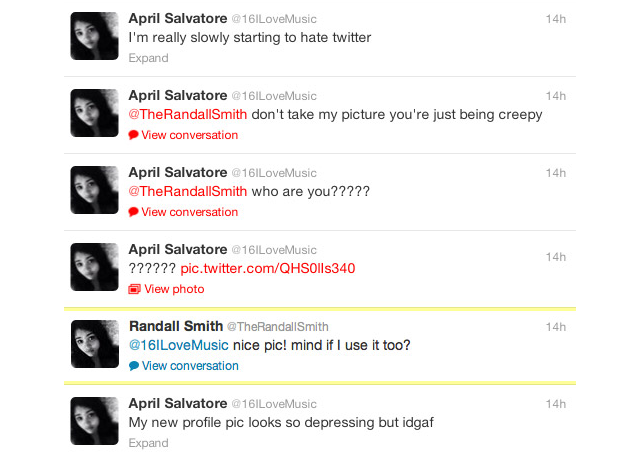

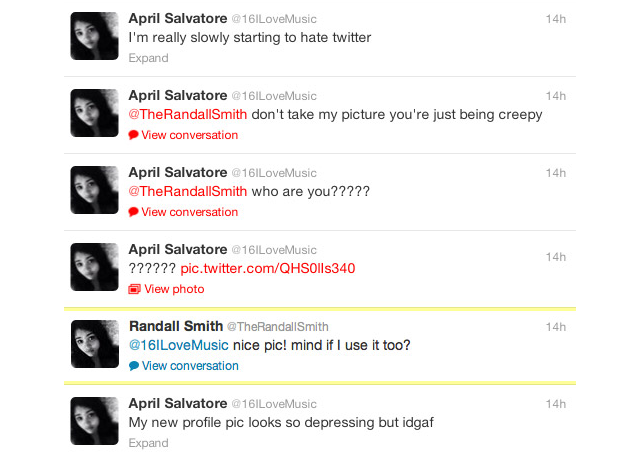

Bill Lindmeier wrote a Ruby script using the Twitter Stream API to listen for any Tweets containing “new profile pic.” When a Tweet was posted the script would download the user’s profile image, upload it to his own account and then reply to the user with a randomly selected Tweet, like “awesome pic!”. The reactions ranged from humored to furious.

Along similar lines, Ilwon Yoon implemented a script that searched for Tweets containing “I am all alone” and replied with cute images obtained from a Google image search and “you are not alone” text.

Mack Howell built on the in-class exercise of asking strangers to borrow their phone then doing something unexpected with it, asking to take pictures of strangers’ browsing history.

The class next turned it’s attention to social automation and APIs, and the potential for their creative misuse.

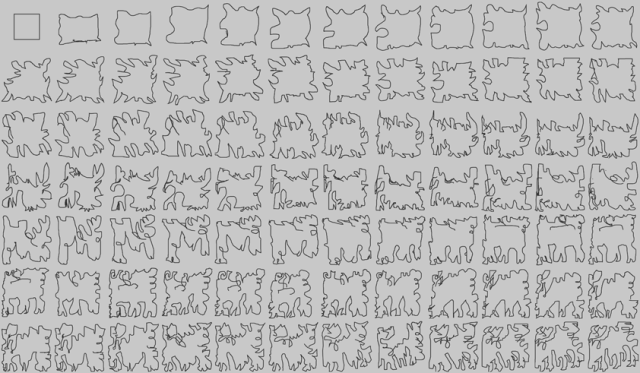

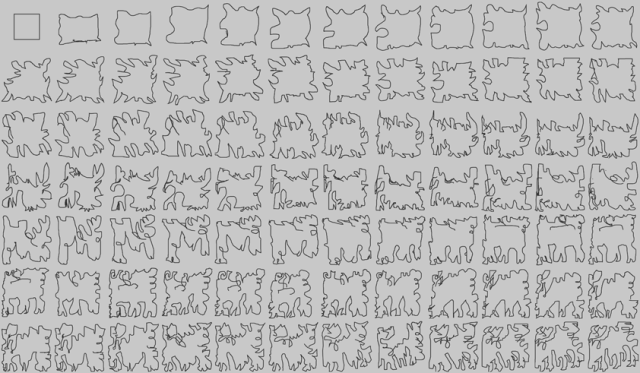

Gal Sasson used the Amazon Mechanical Turk API to create collaborative noise, creating a chain where each turker was prompted to replicate a drawing from the previous turker, seeding the first turker with a perfect square.

Mack Howell used the Google Street View Image API to map out the traceroutes from his location to the data centers of the his most frequently visited IPs.

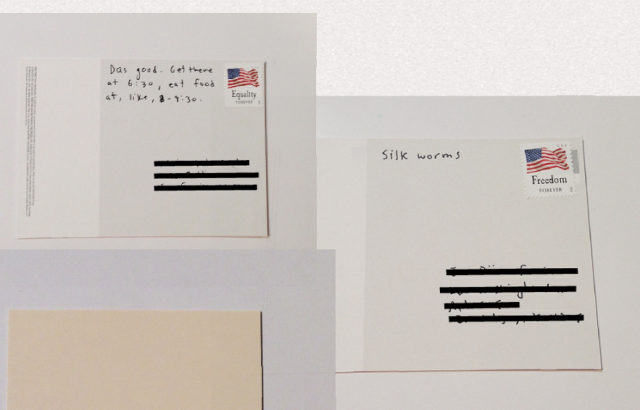

In another assignment, students were prompted to create an “HPI” (human programming interface) that allowed others to control some aspect of their lives, and perform the experiment for one full week.

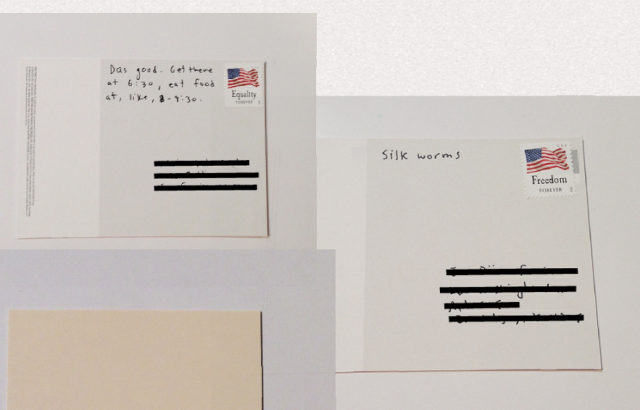

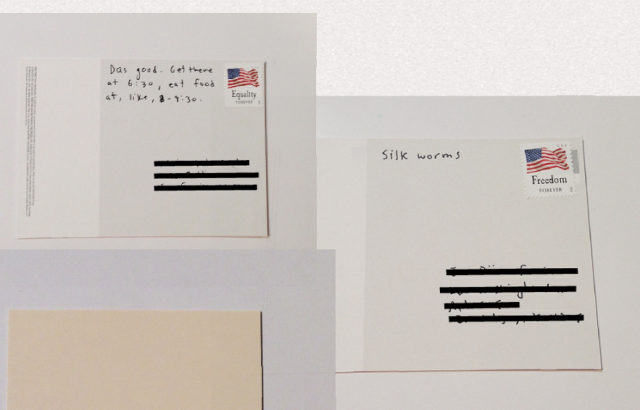

Anytime an email or Twitter direct message was sent to Ben Kauffman with the hashtag #brainstamp and a mailing address, he would get an SMS with the information and promptly right down on a postcard whatever was in his head at that exact moment. He would then mail the thoughts, at turns surreal and mundane, to the awaiting recipient. An alternative to normal social media, Ben challenged us to find ways to be more present while documenting our lives.

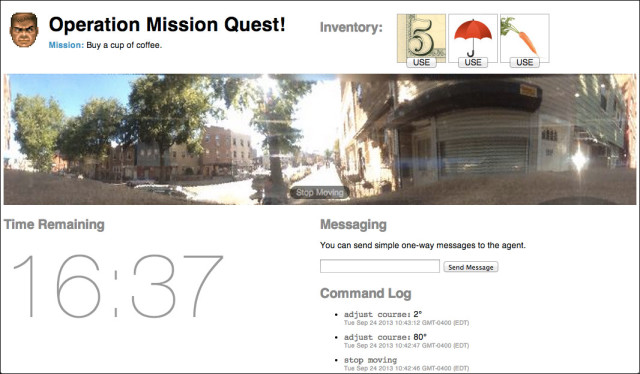

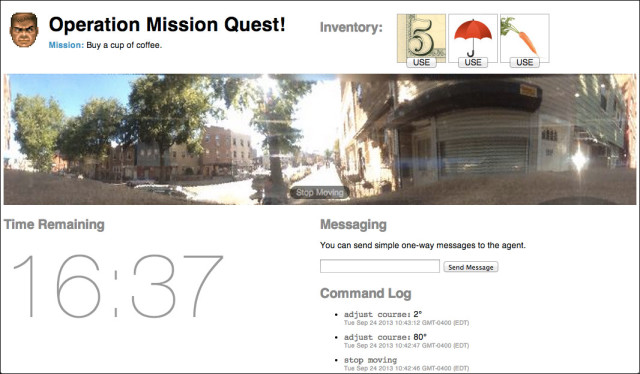

Bill Lindmeier invited his friends to control his movements in realtime through a Google-street-view-esque video interface, and asked them to complete a simple mission: Buy some coffee in under 20 minutes. The tools at their disposal: $5, an umbrella and a carrot.

Mack Howell created a journal written by Amazon Mechanical Turk workers, asking them to generate diary entries based on OpenPaths data sent automatically as he moved around.

In a project called My Friends Complete Me, Su Hyun Kim posted binary questions on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and let her friends collective opinion determine her life choices, including deciding whether to change her last name when she got married.

A couple weeks were spent having focused discussions about security, privacy, and surveillance, including topics like quantified self, government surveillance and historical regimes of naming, and readings from Bruce Schneier, Evgeny Morozov and Steve Mann. In parallel, students were asked to examine their own social lives and compulsively document, share, intercept, impersonate, anonymize and misinterpret.

Mike Allison explored our voyeuristic nature and cultural craving for surveillance, allowing users to watch someone watch someone who may be watching them. In order to watch, users must lend their own camera to the system.

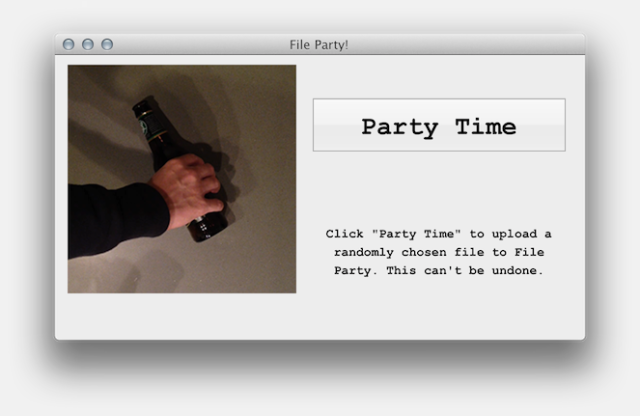

Bill Lindmeier created an app called File Party, a repository of files that have been randomly selected and uploaded from peoples’ hard-drive. In order to view the files, you have to upload one yourself.

In a unit on computer vision and linguistic analysis, students were paired up and asked to create a chat application that provided a filter or adapter that improved their interaction.

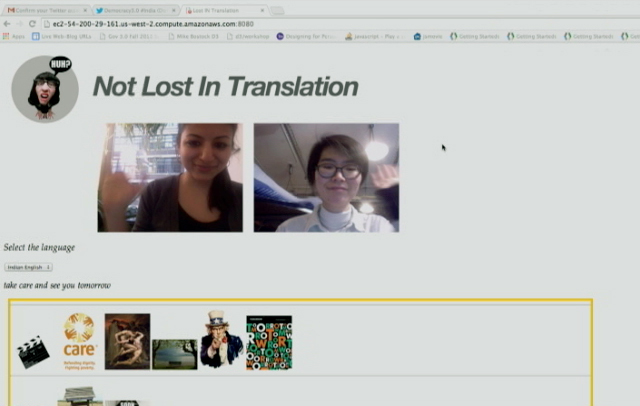

Realizing how much is lost in translation and accents, Tarana Gupta and Hanbyul Jo developed a video chat tool which allows users to talk in their respective language and and displays in real-time text and images corresponding to what is being said.

In FlapChat, Su Hyun Kim and Gal Sasson rethought the way we interact with the web camera, allowing users to flap their arms to fly around a virtual environment while chatting.

Overall, the most successful moments in the class were the ones where students had an opportunity to examine an otherwise common technology or interaction from a new perspective. Short in-class exercises like “ask a stranger to use their phone, and do something unexpected” gave students a reference point for discussion. The “HPI” assignment gave students an unusual challenge of “performing” something for a week, lead to its own set of difficulties and realizations that are distinct from purely technical or aesthetic exercises. On the first day of class a contract was handed out requiring that students respect others’ positions in class, and take responsibility for any actions outside of class. This created a unfamiliar atmosphere and opened up the students to question their freedoms and responsibilities towards each other.

In the future, each two- or three-week section might be expanded to fit a whole semester. Of particular interest were the computer vision, security and surveillance, and mobile platforms sections. Leftover discussion from security and surveillance spilled into the next week, and assignments for mobile platforms could have been taken far beyond the proof-of-concept or design-only stages.

More information about the class, including the complete syllabus, reading lists, and some example code, is available on GitHub.

A condensed version of this class will be taught in January at GAFFTA in San Francisco, details will be announced soon with more information here.

About the Tutors:

Kyle McDonald is a media artist who works with code, with a background in philosophy and computer science. He creates intricate systems with playful realizations, sharing the source and challenging others to create and contribute. Kyle is a regular collaborator on arts-engineering initiatives such as openFrameworks, having developed a number of extensions which provide connectivity to powerful image processing and computer vision libraries. For the past few years, Kyle has applied these techniques to problems in 3D sensing, for interaction and visualization, starting with structured light techniques, and later the Kinect. Kyle’s work ranges from hyper-formal glitch experiments to tactical and interrogative installations and performance. He was recently Guest Researcher in residence at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media, Japan, and is currently adjunct professor at ITP.

http://kylemcdonald.net

Lauren McCarthy is an artist and programmer based in Brooklyn, NY. She is adjunct faculty at RISD and NYU ITP, and a current resident at Eyebeam. She holds an MFA from UCLA and a BS Computer Science and BS Art and Design from MIT. Her work explores the structures and systems of social interactions, identity, and self-representation, and the potential for technology to mediate, manipulate, and evolve these interactions. She is fascinated by the slightly uncomfortable moments when patterns are shifted, expectations are broken, and participants become aware of the system. Her artwork has been shown in a variety of contexts, including the Conflux Festival, SIGGRAPH, LACMA, the Japan Media Arts Festival, the File Festival, the WIRED Store, and probably to you without you knowing it at some point while interacting with her.

http://lauren-mccarthy.com

Thursday, October 03. 2013

Note: Makezine is currently running a useful online program (tutorials, explorations, projects, etc. --Sept. 24 - Oct. 15) for a couple of weeks about the "make" approach that is typical of the magazine, this time linked to the "civic" use of urban sensors. Obviously, we should quickly multiply these kind of initiatives to offer alternatives approaches if we don't want to end up into big corporate/monetized monitored cities...

Via Makezine

-----

- Join our Urban Sensor Hacks Google+ community and connect with makers from all over who are exploring the world around them using off-the-shelf tech and their own ingenuity.

- Discover how sensor-based applications help us understand the urban environment and how people interact within it.

- Learn how sensor platforms make it easy and affordable to build and deploy numerous sensors in urban areas.

- Get started creating sensor-based applications to experiment and learn about the world you live in.

Upcoming online sessions:

10/3 – Sean Montgomery, Kipp Bradford – Bio-Sensing: Feeling the Pulse of a City. At the heart of urban life are people — what they do and communicate, how they think and feel. Bio-sensing is opening a window into people’s behaviors and motivations in a way that will change nearly every aspect of our lives from health to education to retail experience. Learn how you can hack the bio-sensing revolution and change the way you look at yourself and people around you.

10/8 – Tim Dye, Michael Heimbinder, Iem Heng, Raymond Yap – Join the AirCasting crew as they guide you through a step by step process for building your own air quality monitor, discuss the challenges involved in achieving accurate measurements, and detail their work with grassroots groups and schools to conduct environmental monitoring and advance STEAM education.

10/10 – Tomas Diez – Smart Citizen: The largest crowdsourced sensor platform and community on earth. How can we use the information that is surrounding us to improve our cities? Can I become a sensor in my city? Can communities make their neighbourhoods better by sensing and acting in their environment? Smart Citizen tries to tackle these questions by developing an open source and easy-to-use sensor kit connected with an online platform and mobile app. The projects starts with environmental sensors to capture data about air pollution, sound, temperature and humidity in the urban environment, but will grow to more applications in relation with energy, agriculture, health, and its use in the Internet of Things ecosystem. More about Smart Citizen.

Abour Maker Sessions:

Making and hacking: Live online events using a Google Plus community to bring together makers online and at physical locations for hacking and making. Maker Sessions are organized around a theme or a purpose – to look at technologies that enable new applications and to encourage people of all skill levels and interests to participate in the development of ideas and applications.

Hacking the hackathon: Bring makers together where they live and work – at home, at a university or at makerspaces. Explore opportunities to do something cool – something that perhaps nobody else is doing. Learn from master makers about an application area and discover cool maker projects.

Wednesday, September 04. 2013

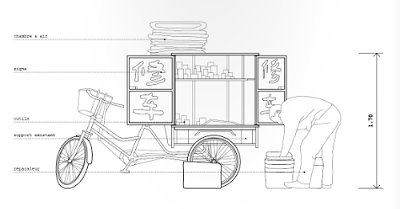

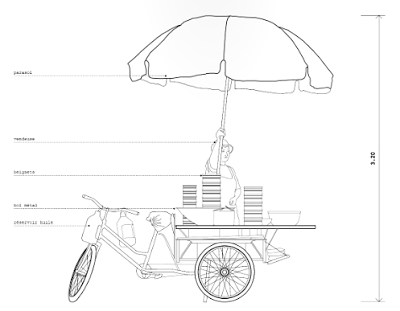

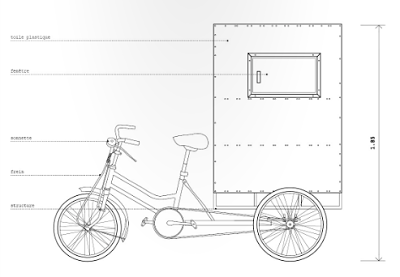

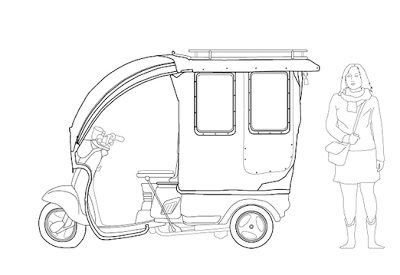

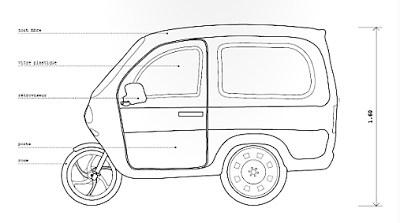

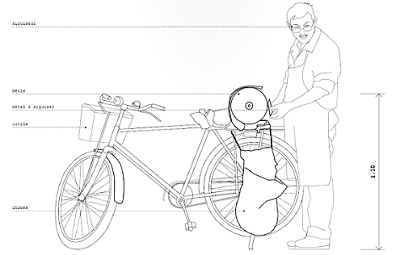

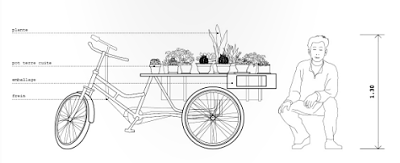

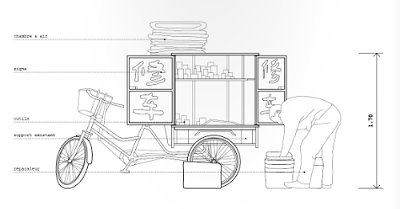

Via Transit-City / Urban & Mobile Think Tank

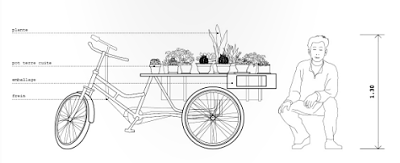

Si vous avez été à Beijing, vous avez forcément vu ces machines légères et hybrides. Leur esthétisme est souvent douteux, mais leur rôle bien réel car elles offrent une autre mobilité que certains considèrent comme dépassé. On peut au contraire imaginer qu'elles représentent l'avenir d'une nouvelle mobilité urbaine qui s'installera de plus en plus entre les voitures et les vélos, et ce aussi bien dans les pays riches que dans les pays pauvres.

Ces planches sont tirées du superbe "Anatomie d'une ville chinoise" réalisé par deux jeunes français qui ont voulu "aborder le contexte urbain chinois à l'échelle macroscopique, c'est à dire humaine". Je n'ai retenu pour ce post que les illustrations liées aux petits véhicules, mais il y a évidement bien d'autres lieux et objets qui sont décrits dans cette très belle réflexion.

Ce travail rappelle le passionnant " Micromachins" sur les services urbains décentralisés en Asie du sud, et qui est désormais téléchargeable, là.

Thursday, February 23. 2012

-----

While the subject of online piracy is certainly nothing new, the recent protests against SOPA and the federal raid on Megaupload have thrust the issue into mainstream media. More than ever, people are discussing the controversial topic while content creators scramble to find a way to try to either shut down or punish sites and individuals that take part in the practice. Despite these efforts, online piracy continues to be a thorn in Big Media’s side. With the digital media arena all but conquered by piracy, the infamous site The Pirate Bay (TPB) has begun looking to the next frontier to be explored and exploited. According to a post on its blog, TPB has declared that physical objects named “physibles” are the next area to be traded and shared across global digital smuggling routes.

TPB defines a physible as “data objects that are able (and feasible) to become physical.” Namely, items that can be created using 3D scanning and printing technologies, both of which have become much cheaper for you to actually own in your home. At CES this year, MakerBot Industries introduced its latest model which is capable of printing objects in two colors and costs under $2,000. With the price of such devices continuing to drop, 3D printing is going to be part of everyday life in the near future. Where piracy is going to come in is the exchange of the files (3D models) necessary to create these objects.

A 3D printer is essentially a “CAD-CAM” process. You use a computer-aided design (CAD) program to design a physical object that you want made, and then feed it into a computer-aided machining (CAM) device for creation. The biggest difference is that traditional CAM setups, the process is about milling an existing piece of metal, drilling holes and using water jets to carve the piece into the desired configuration. In 3D printing you use extrusion to actually create what is illustrated in the CAD file. Those CAD files are the physibles that TPB is talking about, since they are digital they are going to be as easily transferred as an MP3 or movie is right now.

It isn’t too far outside the realm of possibility that once 3D printing becomes a part of everyday life, companies will begin to sell the CAD files and the rights to be able to print proprietary items. If the technology continues to advance at the same rate, in 10 or 20 years you might be printing a new pair of Nikes for your child’s basketball game right in your home (kind of like the 3D printed sneakers pictured above). Instead of going to the mall and paying $120 for a physical pair of shoes in a retail outlet, you will pay Nike directly on the internet and receive the file necessary to direct your printer to create the sneakers. Of course, companies will do their level best to create DRM on these objects so that you can’t freely just print pair after pair of shoes, but like all digital media it will be broken be enterprising individuals.

TPB has already created a physibles category on its site, allowing you to download plans to be able to print out such things as the famous Pirate Bay Ship and a 1970 Chevy hot rod. For now it’s going to be filled with user-created content, but in the future you can count on it being stocked with plans for DRM-protected objects.

Monday, September 12. 2011

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

Researchers are developing hacking drones that could build a wireless botnet or track someone via cell phone.

By Robert Lemos

|

Hacking on high: The SkyNet drone, built from a toy quadricopter and a small computer, can fly for up to 13 minutes, or land and then operate for nearly two hours.

Credit: Stevens Institute of Technology |

The buzz starts low and quickly gets louder as a toy quadricopter flies in low over the buildings. It might look like flight enthusiasts having fun, but it could be a future threat to computer networks.

In two separate presentations last month, researchers showed off remote-controlled aerial vehicles loaded with technology designed to automatically detect and compromise wireless networks. The projects demonstrated that such drones could be used to create an airborne botnet controller for a few hundred dollars.

Attackers bent on espionage could use such drones to find a weak spot in corporate and home Internet connections, says Sven Dietrich, an assistant professor in computer science at the Stevens Institute of Technology who led development of one of the drones.

"You can bring the targeted attack to the location," says Dietrich. "[Our] drone can land close to the target and sit there—and if it has solar power, it can recharge—and continue to attack all the networks around it."

(...)

More about it on MIT Technology Review

|