Sticky Postings

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Thursday, December 12. 2013

(Joking) note: does somebody came up with some sort of Moore's law regarding the size of these ships? Will there be a "singularity" too with container boats? Maybe a point where they will be able to contain the "captive globe"?

-----

La taille des nouveaux porte-containers fait comprendre que la notion de Mega Mobil Factory n'est pas seulement une fiction comme certains très beaux projets pourraient le laisser croire - voir " New Offshore Nomadic City ?" ou " Salt Eater Moving Machine" - mais bien une réalité en marche.

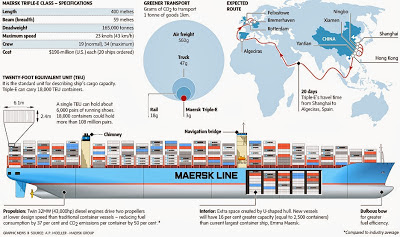

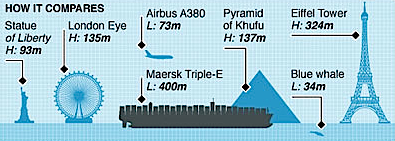

Avec la nouvelle classe des Triple-E et notamment le Maerks Mc-Kinney Moller, nous avons faire à un nouvelle catégorie de machines qui va peu à peu bouleverser nos façons de penser ce qui peut se réaliser sur un bateau, et donc ce à quoi pourraient devenir les navires dans futur. Car tout comme le paquebot de croisière a transformé un moyen de transport en un lieu de destination ( d'un bateau en un club de vacances), la mutation des porte-containers annoncent peut-être d'autres évolutions plus radicales tel le projet BlueSeed dont je vous ai parlé dans mon précédents post. Pourquoi, en effet, ne pas imaginer que le porte-containers passe du statut de moyen de transport à celui de lieu de production off shore ? Les containers passerait du statut de boite à celui de lieu de production - voir là, là et là -, soit sous sous forme de mini factory (un ou deux containers) soit de mega factory par l'assemblage de plusieurs dizaines de containers. On est loin d'être là aujourd'hui, mais la révolution industrielle en cours - voir " Micro-multinationale du futur ?" et là - va peut être changer les choses.

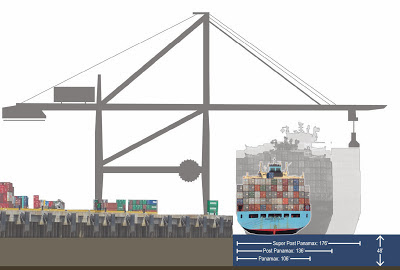

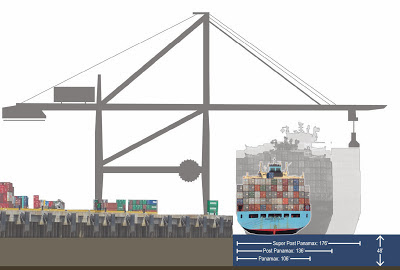

Ce qui est certain c'est que ces nouvelles classes de porte-containers perturbent tout, nos grilles de lectures, mais aussi les infrastructures terrestres. Les ports ont, en effet, de plus en plus de mal à adapter leurs équipement, et notamment leurs grues, à ce gonflement incessant de plus en plus rapide du gabarits des nouvelles générations de navires.

L'évolution est tellement rapide que certains ports, et pas forcément les moins performants, sont obligés de faire appel à des méga bateaux grues pour décharger les porte containers qui font escale chez eux - voir par exemple Miami, là.

Les ports qui avaient déjà perdu leurs bâtiments, les docks ou les hangars, depuis vingt ans avec l'apparition des containers vont peut-être bientôt perdre leurs grues. Pourquoi en effet continuer à investir dans des grues s'il faut les changer tous les 10 ans ? C'est quoi un port dans ces conditions là ? L’espace portuaire, entièrement dédié aux containers, ne tolère plus aujourd'hui tout ce qui est fixe ou impossible à déplacer. Mais demain c'est peut-être les ports qui seront nomade. En effet, on retrouve aujourd'hui à terre, les logiques portuaires que développe l' US Navy au large avec ses ports mobiles - voir " Quand les bateaux deviennent des ports".

Et l'on peut-être tenté de se demander si, tout comme le container a détruit le port en le transformant en un simple parking à boites, le porte-containers ne pourrait pas à terme détruire non seulement les ports mais aussi une partie du tissus industriel statique et terrestre en devenant lui-même une mega factory flottante via des containers transformés en mini-usines ?

Bref, et dit autrement, et si notre futur industriel s'écrivait entre cela et cela ?

L'hypothèse n'est aujourd'hui qu'une pure hypothèse, mais il ne faut jamais oublier le rôle défricheur des militaires dans l'évolution de la mobilité.

Et pour continuer à réfléchir sur le rôle des containers dans l'économie et le système productif mondial, je ne peux que vous inciter à regarder :

Tuesday, December 04. 2012

Via Cabinet

-----

By Nicola Twilley

More than three-quarters of the food consumed in the United States today is processed, packaged, shipped, stored, and sold under artificial refrigeration. The shiny, humming stainless steel box in your kitchen is just the tip of the iceberg, so to speak—a tiny fragment of the vast global network of temperature-controlled storage and distribution warehouses cumulatively capable of hosting uncounted billions of cubic feet of chilled flesh, fish, or fruit. Add to that an equally vast and immeasurable volume of thermally controlled space in the form of shipping containers, wine cellars, floating fish factories, international seed banks, meat-aging lockers, and livestock semen storage, and it becomes clear that the evolving architecture of coldspace is as ubiquitous as it is varied, as essential as it is overlooked.

(...)

More about it and about a "perpetual winter" on Cabinet's website.

Monday, June 04. 2012

-----

by rholmes

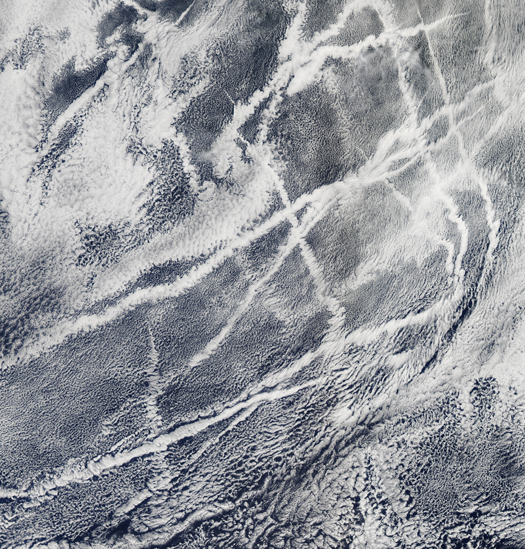

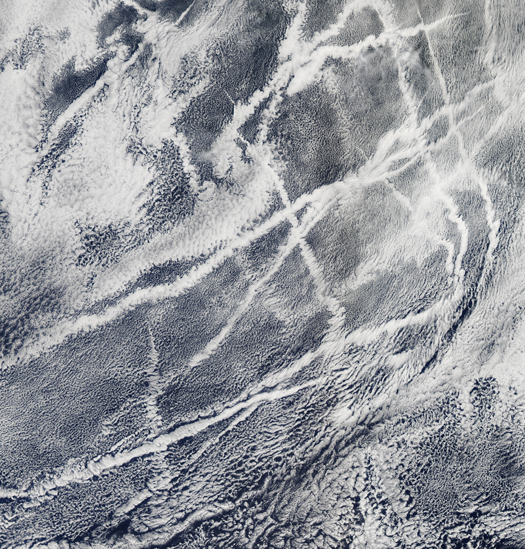

[Ship tracks -- "narrow clouds... form[ed] when water vapor condenses around tiny particles of pollution that ships either emit directly as exhaust or that form as a result of gases within the exhaust” — in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California, captured photographically by a NASA satellite; the atmospheric trace of the seaborne transfer of goods and materials between East and West.]

Monday, April 11. 2011

Via Treehugger

-----

Crowds gather at Guangzhou Railway Station for the New Year exodus in 'Last Train Home.' Image: Zeitgeist Films

Every year, 130 million people throng China's railway stations, frantically trying to obtain a seat on a train that will take them home for the lunar New Year -- a trip that is for many rural people living and working in the country's industrial cities their only chance to see the families, and even the children, they have left behind. In addition to the human drama, the trek, believed to constitute the largest human migration in the world, taxes the country's transportation systems to the limit.

The chaos at the train stations, the stark difference between urban and rural China, and the alienation among families of economic migrants are strikingly portrayed in the new documentary "Last Train Home" by Lixin Fan, who previously worked on the acclaimed film "Up The Yangtze," about the controversial Three Gorges Dam.

In his debut feature, which screened at this year's If! Istanbul Independent Film Festival, the director focuses on one couple who have been making the New Year's trip for 16 years, their sole break from a life of difficult factory labor. But, of course, they are not alone. In addition to their millions of counterparts in China, a similar migration occurs each year in Indonesia, where 30 million workers go home for the end of the Muslim month of Ramadan.

Mass Migrations Tax Transit Systems

Such mass migrations "present enormous logistical and safety challenges to local, state, and national governments," Jonna McKone wrote recently for the urban transportation blog The City Fix. "Transport systems are designed ideally to handle maximum capacity, but very few can deal with an additional yearly surge in migrants... [In Indonesia], this important holiday has become a nightmare, as millions of city dwellers attempt to return to their villages but face limited transport options."

According to the New York Times, Ramadan travelers in Indonesia "brave enormous jams, exhaustion, and bandits to make it back home," with hundreds dying on the road each year. Though the Indonesian government makes efforts ahead of the holiday to repair roads and carry out other initiatives to ease travel, McKone writes, the problem will remain as long as the world's massive cities continue to expand at the expense of investment in the environment and rural regions.

More On China's Cities

Water Shortages Could Slow China's Growth

China's Zero-Carbon City Dongtan Delayed, But Not Necessarily Dead, Says Planner

Beijing's Olympic Pollution Solution: Luck + Data Manipulation

Greening China's Mayors: A Q&A with Dr. Steve Hammer of the Mayoral Training Program on Energy

Urban China Magazine: 'An Encyclopedia of Chinese Cities in a Time of Junk'

A Video Clip Is Worth ... Linfen, China: The Most Polluted City in the World

Treading Heavily on the Environment: China's Growing Eco-Footprint

Wednesday, February 23. 2011

Via Mammoth

-----

by Stephen

Bridging the gap between mammoth’s interest in infrastructure, global logistics, economies, and really, really big things is this announcement from Moller-Maersk:

Danish shipper Moller-Maersk, the biggest container carrier, confirmed Monday it has signed a contract for a South Korean shipyard to build it 10 giant container ships over the next three years… The new container vessels, at 400 metres long, 59 metres wide and 73 metres tall, will be “the largest vessel of any type known to be in operation,” but emit half as much carbon dioxide as the industry average for Asia/Europe trade, the statement added.

Purchasing your own fleet of carriers will set you back $2bn.

[The Georg Maersk - 9074 TEU (twenty-foot equivalent units - typical shipping containers are forty feet long, meaning each count for 2 TEU). The new ships will be approximately 18,000 TEU.]

[Photos via Maersk, h/t to Telstar Logistic]

Monday, December 20. 2010

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

A visit to FedEx's SuperHub, where technology powers the global economy while you sleep.

By Jeffrey F. Rayport

|

| Move it: At the FedEx SuperHub in Memphis, chutes and conveyor belts carry more than 1.2 million packages each night. |

The retail season is in full swing for the holidays, and it couldn't happen without two giants of logistics, UPS and FedEx. As those brown UPS trucks remind us, the global economy thrives on "synchronizing the world of commerce."

Not long ago, I talked with FedEx founder Fred Smith at a World 50 meeting of executives in Memphis, Tennessee. More recently I visited the company's operations in the midst of holiday-season madness.

Here is some of what I learned:

Make no little plans. The great architect Daniel Burnham once said, "Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men's blood and probably will not themselves be realized."

Fred Smith's inspiration for FedEx involved no little plans. The result is the largest air-cargo company in the world: it employs 290,000 people, maintains a fleet of 75,000 trucks, and owns and operates 684 jets. It has more wide-body jets than any airline, including Boeing 777s that can fly from Shanghai to Memphis nonstop. The SuperHub, the heart of FedEx's operations, measures four by four miles and occupies 900 acres. Some 30,000 people are needed to run it.

In many ways, the SuperHub dwarfs its "big brother," Memphis International Airport. The SuperHub is a world unto itself, with a hospital, a fire station, a meteorology unit, and a private security force; it has branches of U.S. Customs and Homeland Security, plus anti-terror operations no one will talk about. It has 20 electric power generators as backup to keep it running if the power grid goes down.

Every weekday night at the SuperHub, FedEx lands, unloads (in just half an hour, even for a super-jumbo 777), reloads, and flies out 150 to 200 jets. Its aircraft take off and land every 90 seconds. This all happens between 11 p.m. and 4 a.m. Central Time. The SuperHub processes between 1.2 million and 1.6 million packages a night.

From Thanksgiving to Christmas, FedEx will ship 223 million packages worldwide. Last Monday, its busiest night ever, it moved 16 million packages.

Be a speed demon and a control freak. Walking the SuperHub, you can feel the need for speed. Planes land continually and disgorge oversized aluminum containers; parcels of all shapes and sizes zoom into processing centers on hyper-kinetic conveyor belts; and no fewer than 2,000 drivers of light trucks, forklifts, and small industrial vehicles swarm throughout the facility. To control it all, everything and everyone is UPC-tagged; everyone and everything is tracked.

Nothing illustrates the point better than the Small Package Sortation System, a vast, FedEx-designed machine that sits in its own warehouse. It cost $175 million to build and sorts an average of 1.2 million packages a night. It scans the bar code on every package at least 30 times. Any delays in the process can get detected in minutes. That's why the U.S. Postal Service has become one of FedEx's major accounts. FedEx's SmartPost operation delivers the "last mile" for much of the United States' daily mail.

Because FedEx is as disciplined and reliable as it is, standard items it ships include chemotherapy drugs, human hearts and other live human organs, artificial joints, contact lenses, surgical scalpels, fresh blood, heart monitors, circuit boards, auto bumpers, tractor parts, Swiss watch elements, rare manuscripts, aviation components, Maine lobsters, crickets, whales, snakes, Japanese cherries, Hawaiian flowers, tennis shoes, and European fragrances. Oh, and FedEx also transports the occasional Arabian race horse and antique automobile. Any large cargo, from 150 pounds to 2,000 pounds, is fair game.

It's about the information, stupid. IT both created demand for FedEx's services (Dell was one of FedEx's first tech customers) and enabled FedEx to thrive. Smith realized that tracking packages—knowing points of origin, movement through the system, and estimated times of arrival—was nearly as valuable as the packages themselves. Today's FedEx has made innovative uses of new data-tracking technologies, such as QR codes and RFID tags. The latter report on temperature and moisture conditions of individual packages as they move from origination point to destination.

If there were "Seven Wonders of the Industrial World," FedEx's SuperHub would easily rank among them, right up there with Toyota's production centers, Google's data centers, and NASA's Mission Control.

Jeffrey F. Rayport is a former faculty member at Harvard Business School and the author of several books about electronic commerce. He is the founder of Marketspace LLC, a strategic advisory company. Currently, he is an operating partner at Castanea Partners, a Boston-based private equity firm.

Copyright Technology Review 2010.

|