Sticky Postings

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Tuesday, February 27. 2024

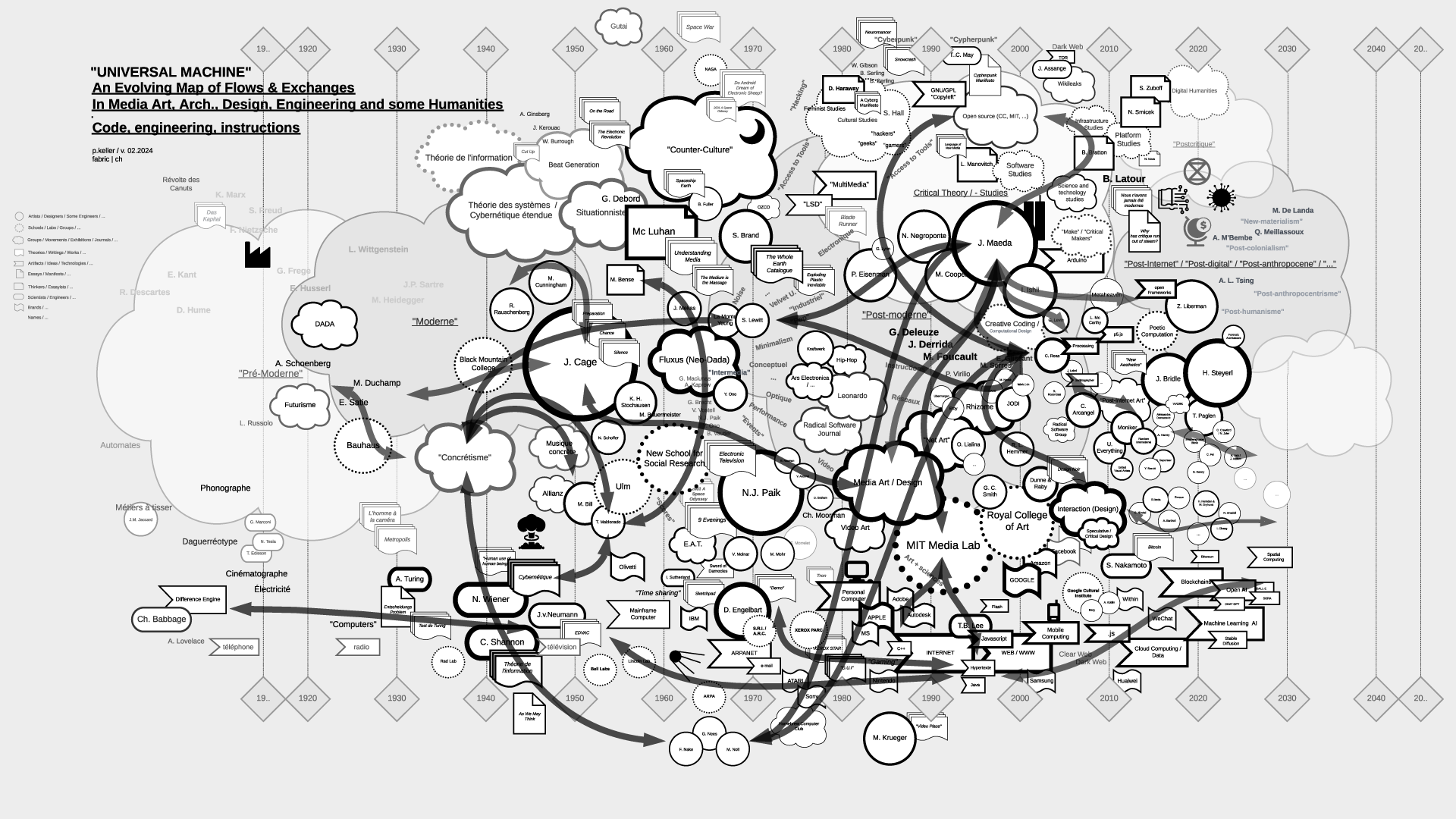

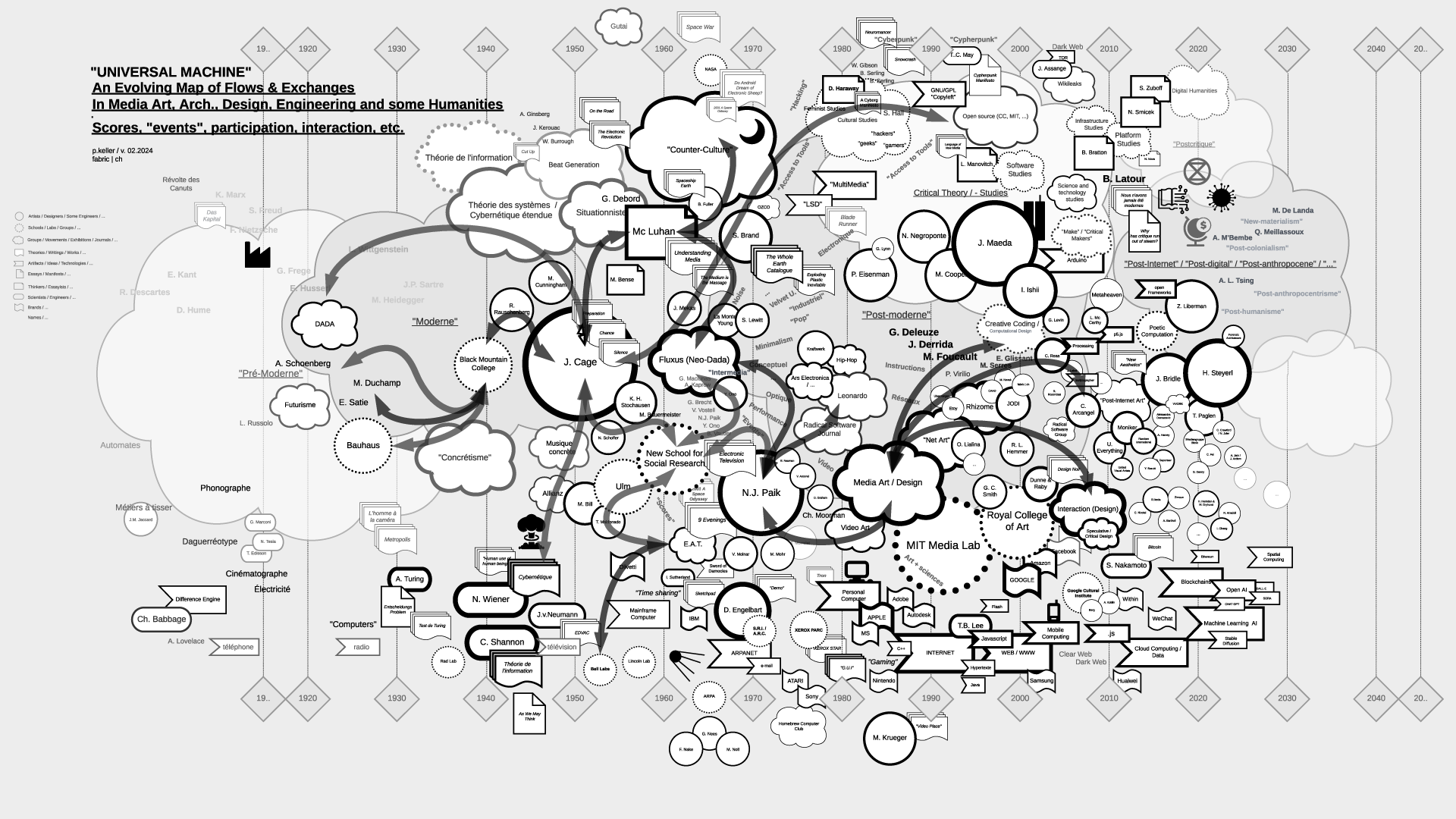

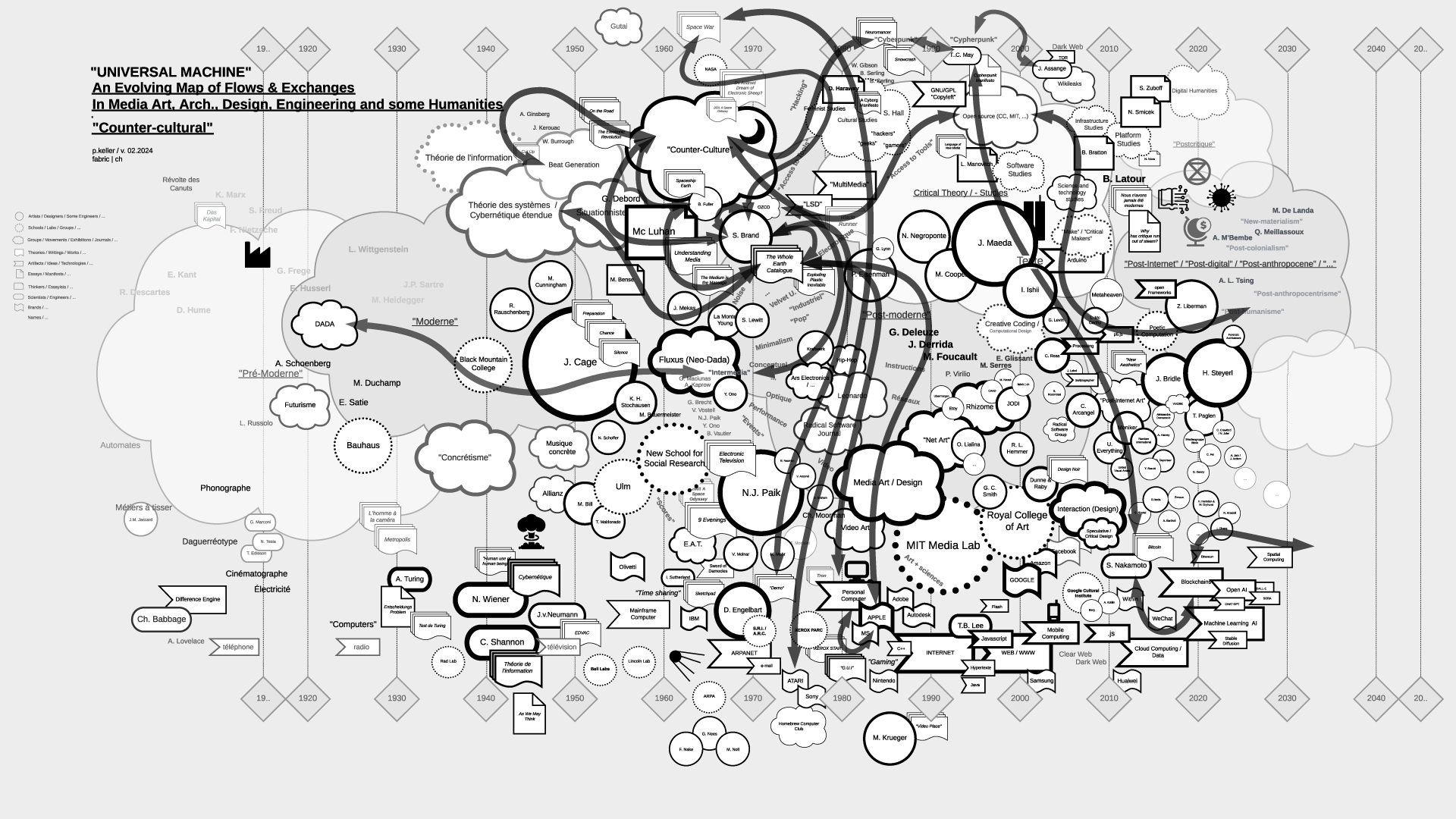

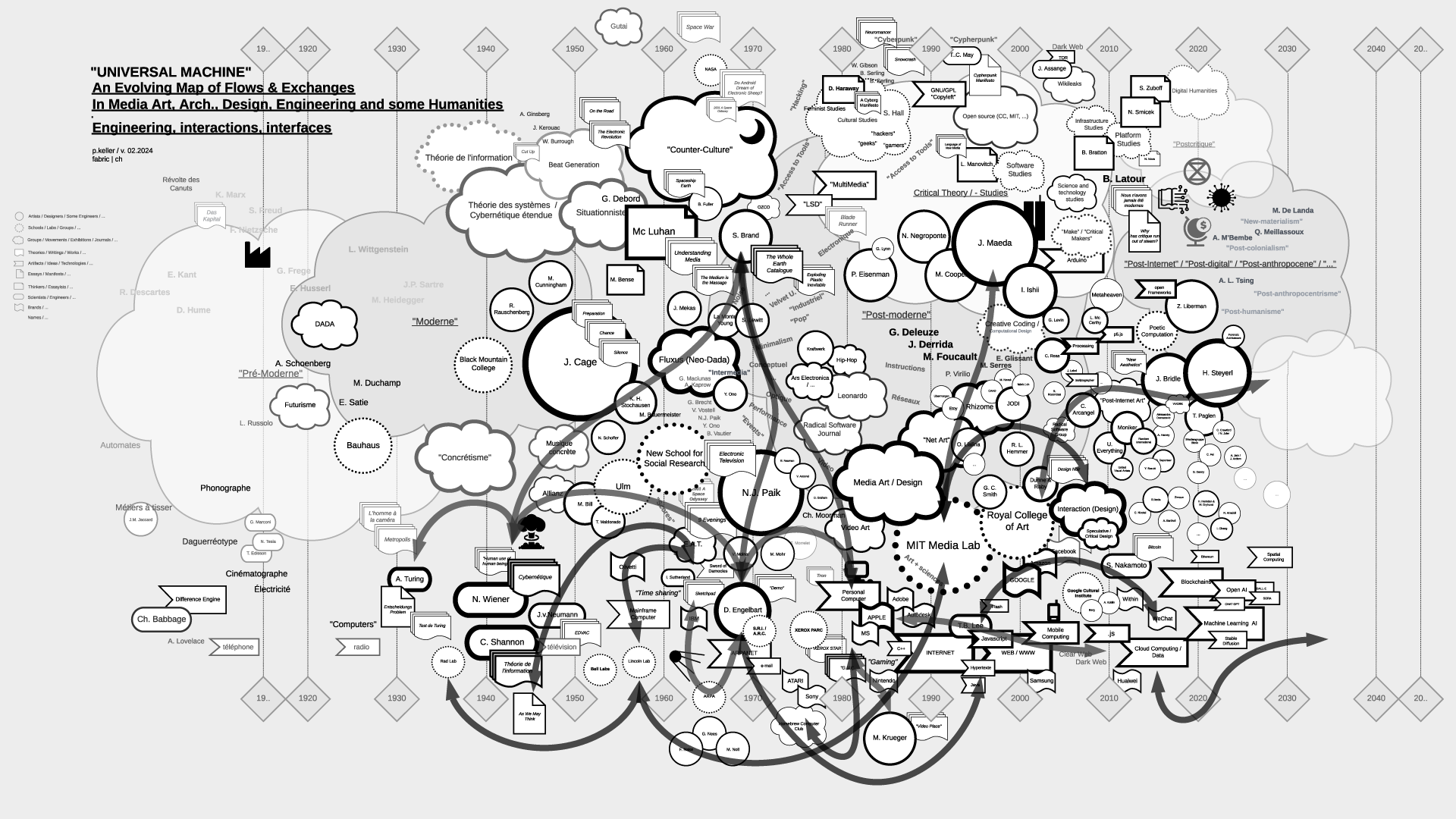

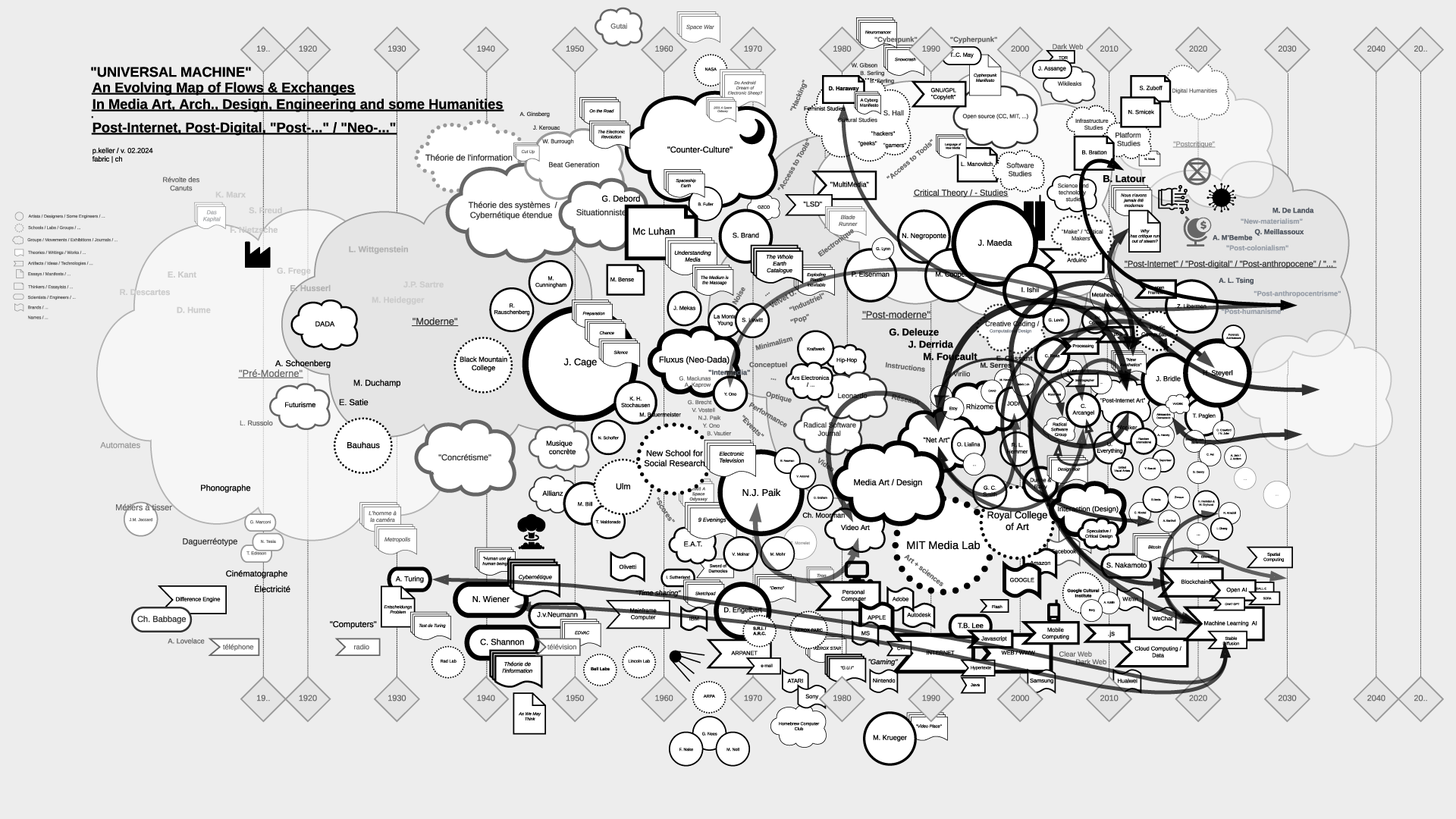

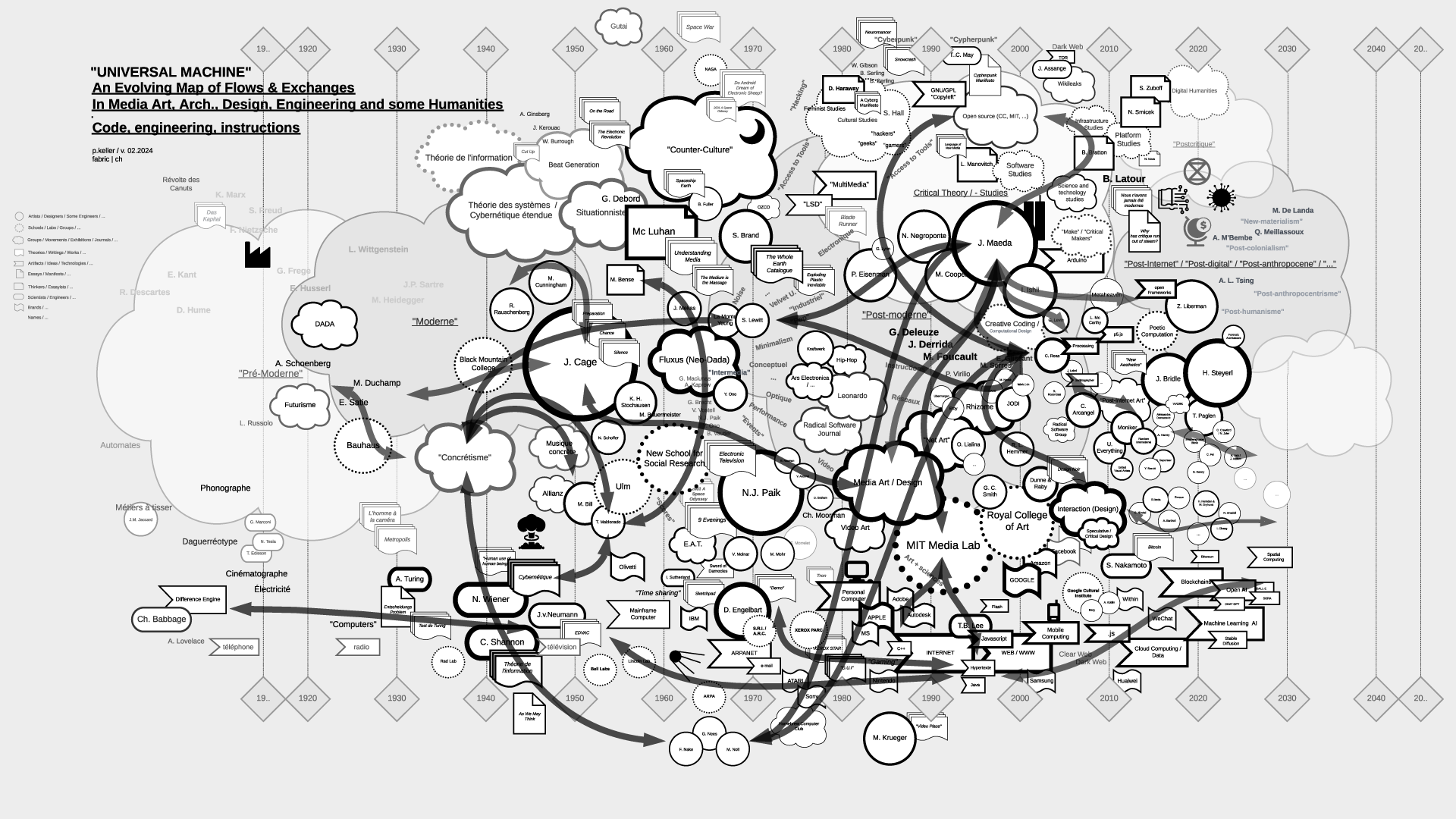

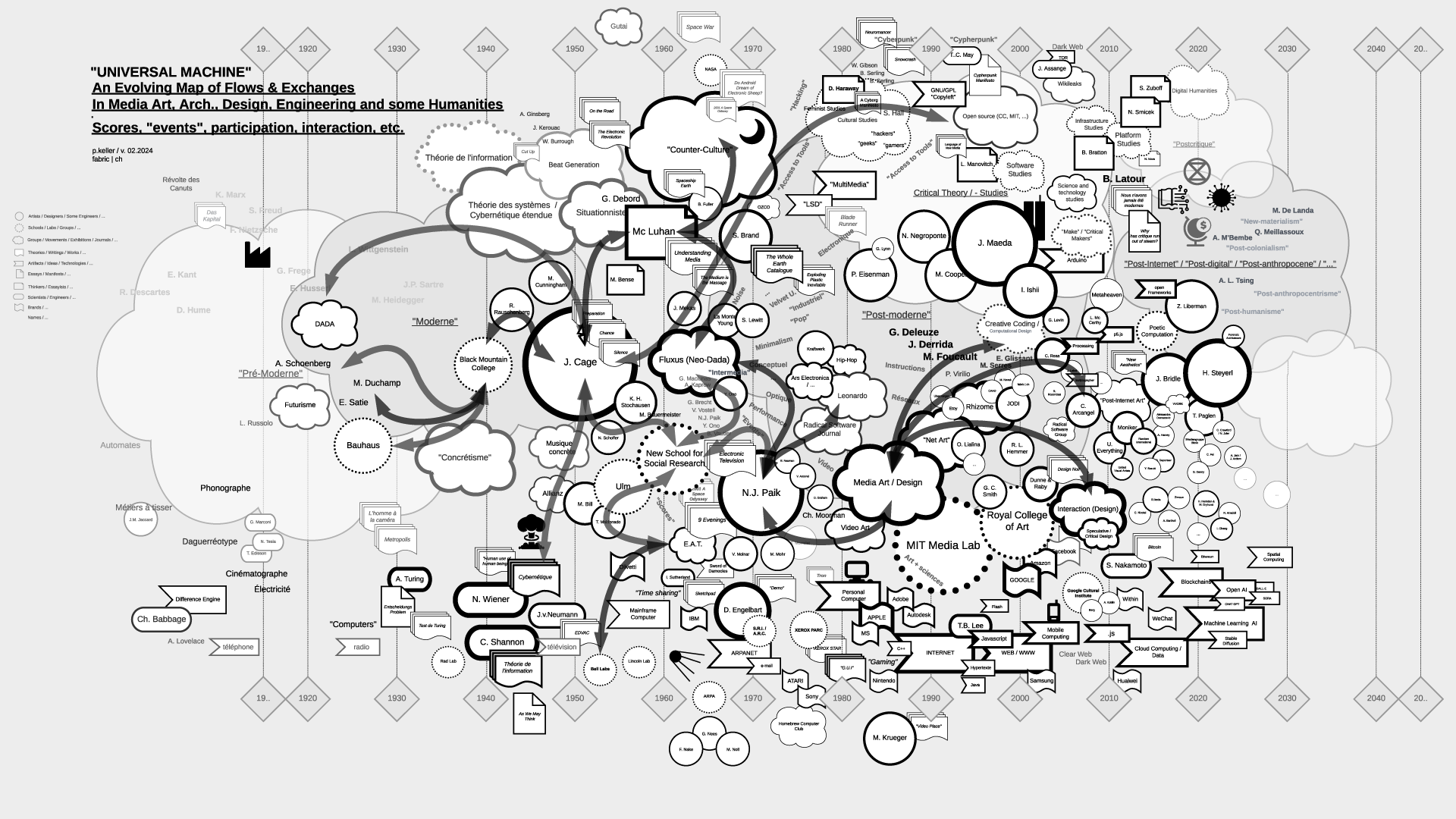

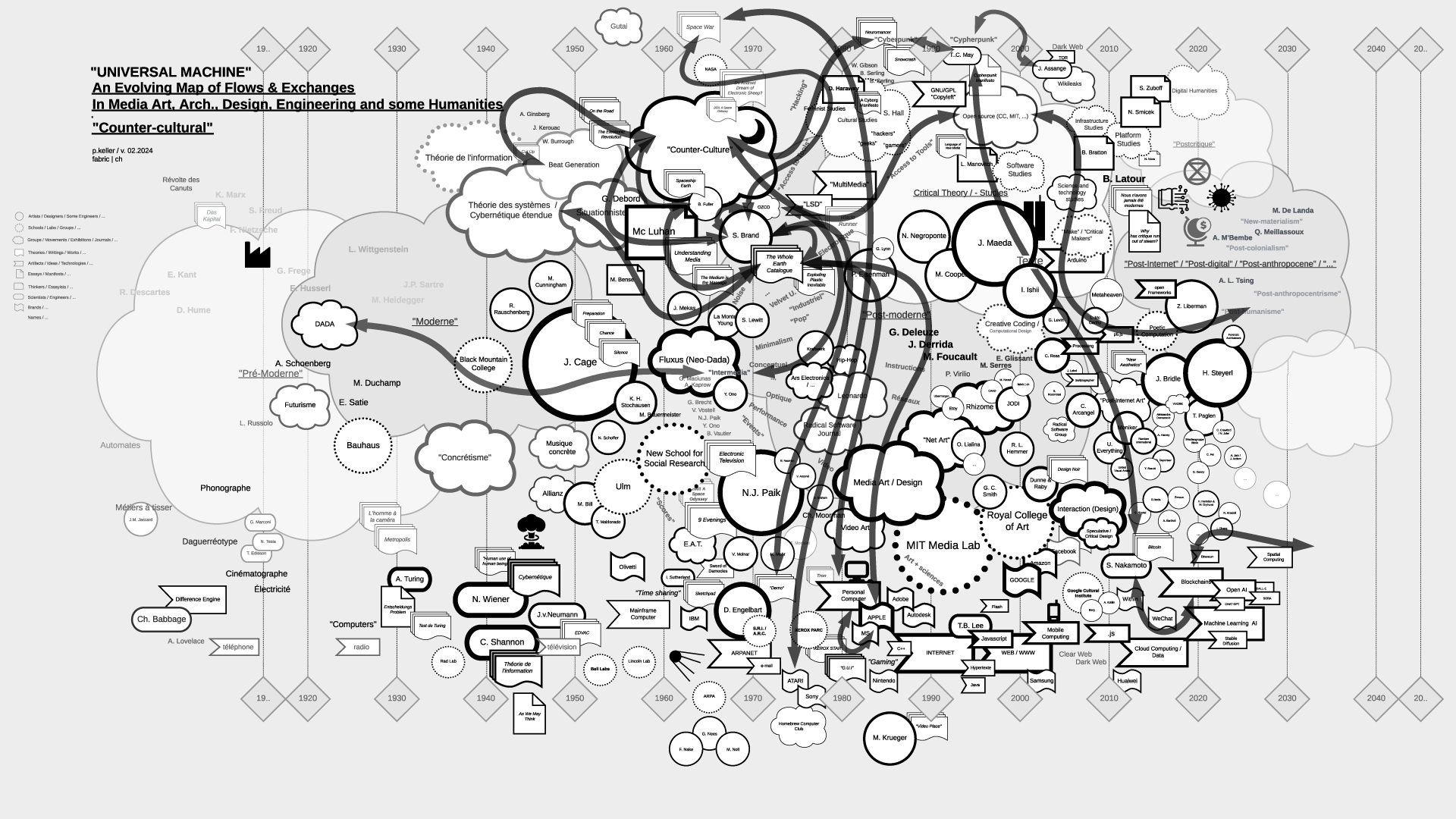

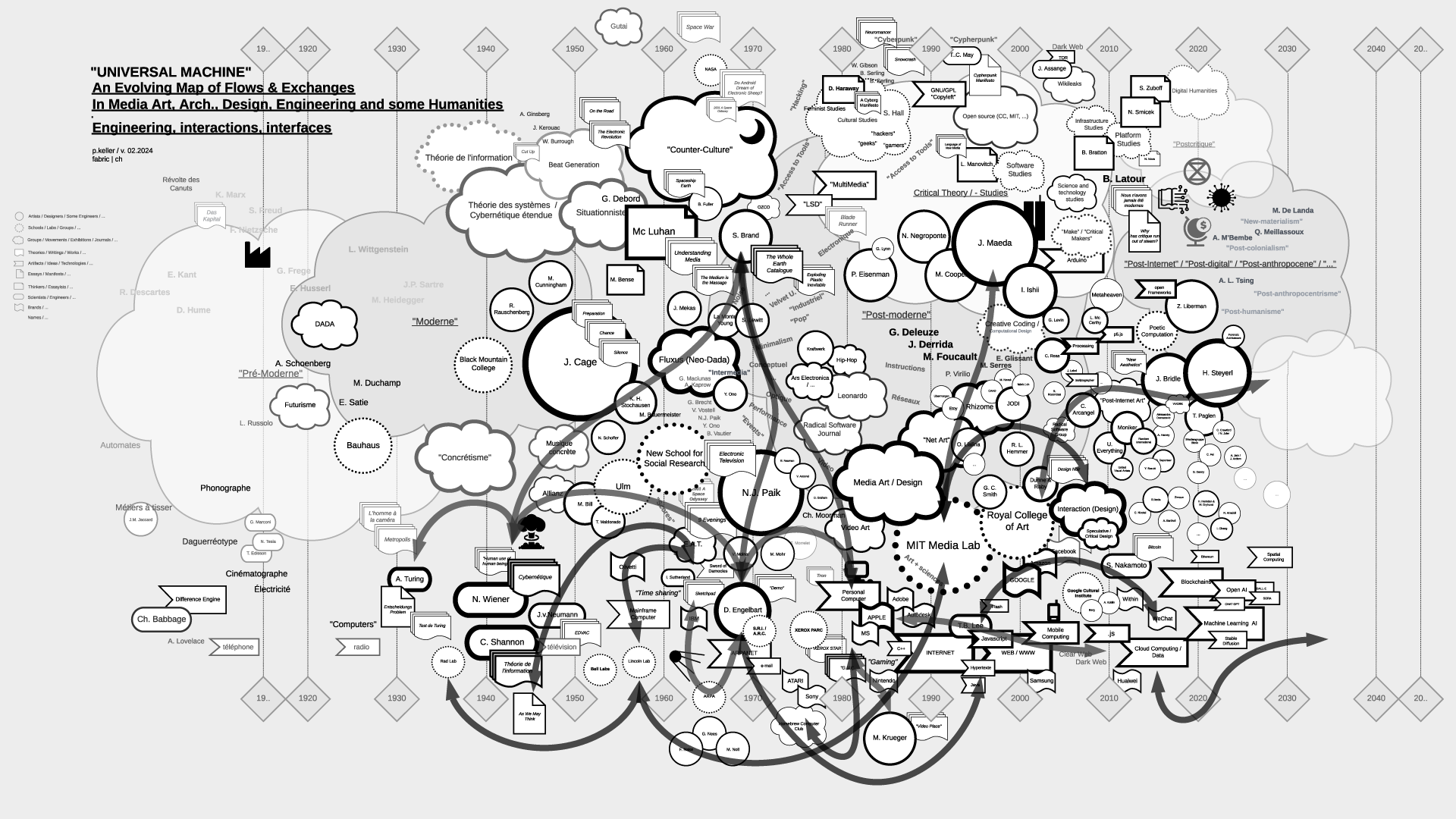

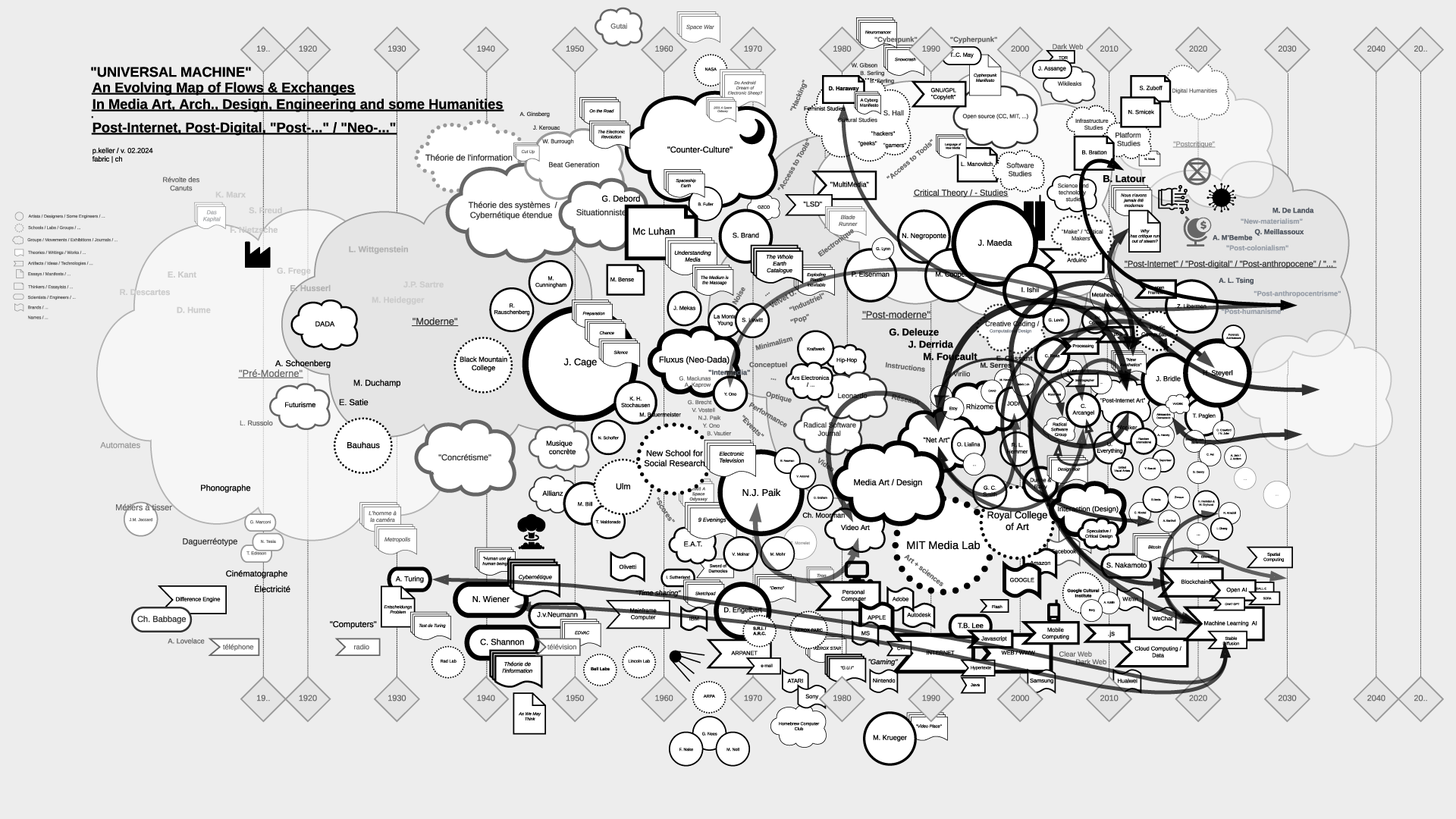

Note (03.2024): The contents of the files (maps) have been updated as of 02.2024.

-

Note (07.2021): As part of my teaching at ECAL / University of Art and Design Lausanne (HES-SO), I've delved into the historical ties between art and science. This ongoing exploration focuses on the connection between creative processes in art, architecture, and design, and the information sciences, particularly the computer, also known as the "Universal Machine" as coined by A. Turing. This informs the title of the graphs below and this post.

Through my work at fabric | ch, and previously as an assistant at EPFL followed by a professorship at ECAL, to experience first hand some of these massive transformations in society and culture.

Thus, in my theory courses, I've aimed to create "maps" that aid in comprehending, visualizing, and elucidating the flux and timelines of interactions among individuals, artifacts, and disciplines. These maps, imperfect and constrained by size, are continuously evolving and open to interpretation beyond my own. I regularly update them as part of the process.

Yet, in the absence of a comprehensive written, visual, or sensitive history of these techno-cultural phenomena as a whole, these maps serve as valuable approximation tools for grasping the flows and exchanges that either unite or divide them. They offer a starting point for constructing personal knowledge and delving deeper into these subjects.

This is precisely why, despite their inherent fuzziness - or perhaps because of it - I choose to share them on this blog (fabric | rblg), in an informal manner. It's an invitation for other artists, designers, researchers, teachers, students, and so forth, to begin building upon them, to depict different flows, to develop pre-existing or subsequent ideas, or even more intriguingly, to diverge from them. If such advancements occur, I'm keen on featuring them on this platform. Feel free to reach out for suggestions, comments, or to share new developments.

...

It's worth mentioning that the maps are structured horizontally along a linear timeline, spanning from the late 18th century to the mid-21st century, predominantly focusing on the industrial period. Vertically, they are organized around disciplines, with the bottom representing engineering, the middle encompassing art and design, and the top relating to humanities, social events, or movements.

Certainly, one might question this linear timeline, echoing the sentiments of writer B. Latour. What about considering a spiral timeline, for instance? Such a representation would still depict both the past and the future, while also illustrating the historical proximities of topics, connecting past centuries and subjects with our contemporary context in a circular manner. However, for the time being, and while recognizing its limitations, I adhere to the simplicity of the linear approach.

Countless narratives can emerge as inherent properties of the graphs, underscoring that they are not their origins but rather products thereof.

...

The selection of topics (code, scores-instructions, countercultural, network-related, interaction, "post-...") currently aligns with the themes of my teaching but is subject to expansion, possibly toward an underlying layer revealing the material conditions that underpinned and facilitated the entire process.

In any case, this could serve as a fruitful starting point for some further readings or perhaps a new "Where's Waldo/Wally" kind of game!

Via fabric | ch

-----

By Patrick Keller

Rem.: By clicking on the thumbnails below you'll get access to HD versions.

"Universal Machine", main map (late 18th to mid 21st centuries):

Flows in the map > "Code":

Flows in the map > "Scores, Partitions, ...":

Flows in the map > "Countercultural, Subcultural, ...":

Flows in the map > "Network Related":

Flows in the map > "Interaction":

Flows in the map > "Post-Internet/Digital, "Post -..." , "Neo -...", ML/AI":

...

To be continued (& completed) ...

Saturday, February 17. 2018

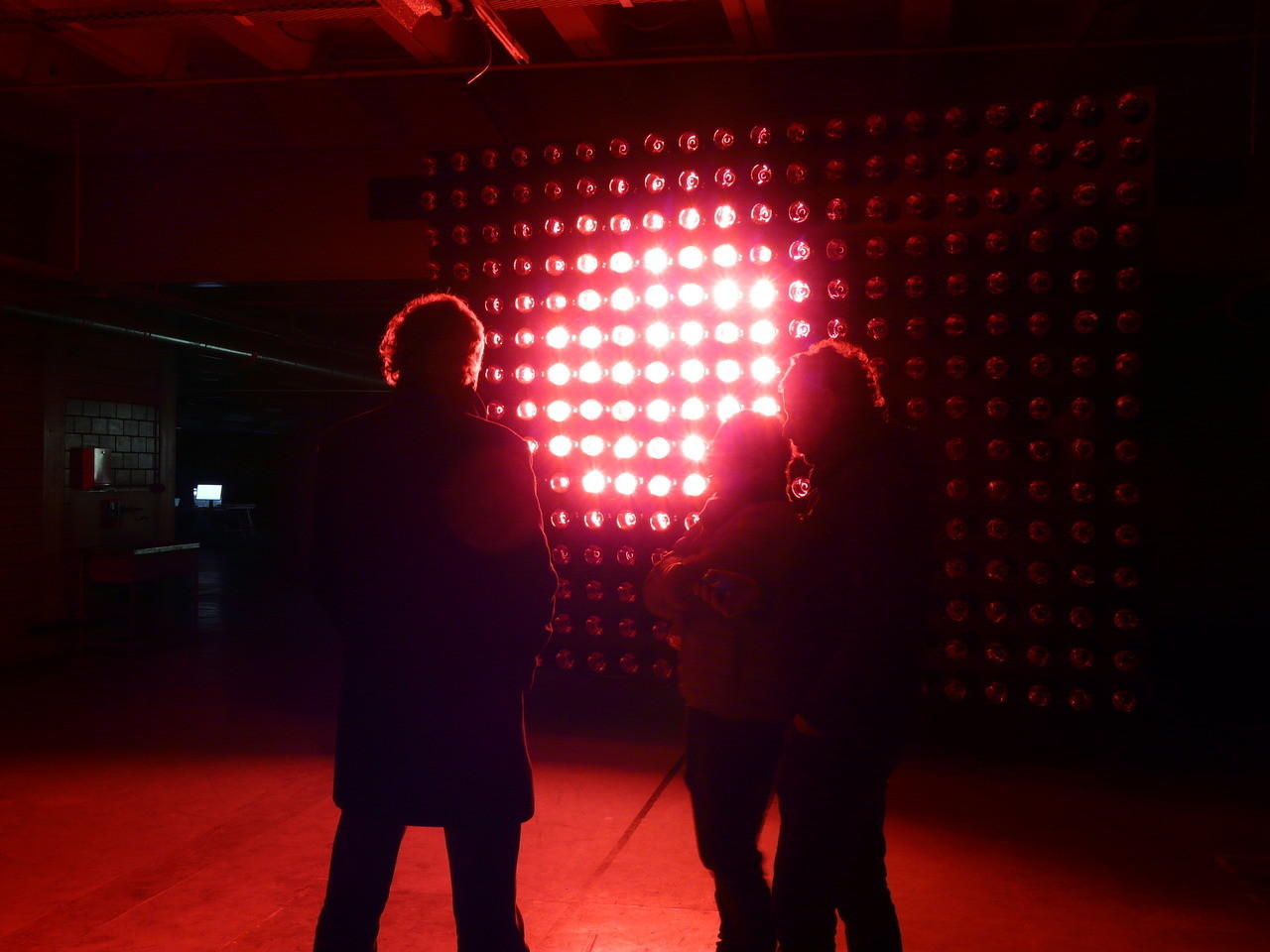

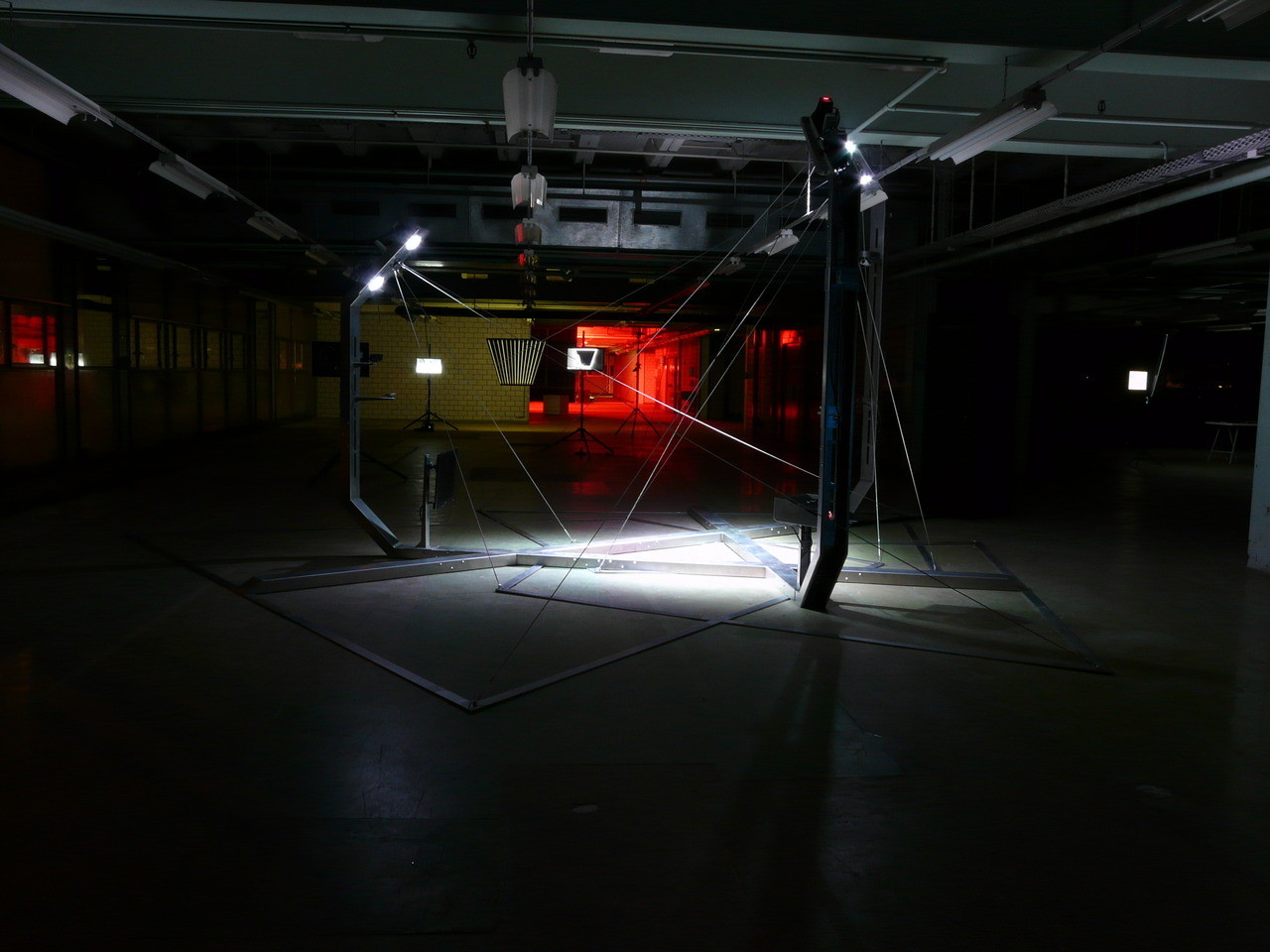

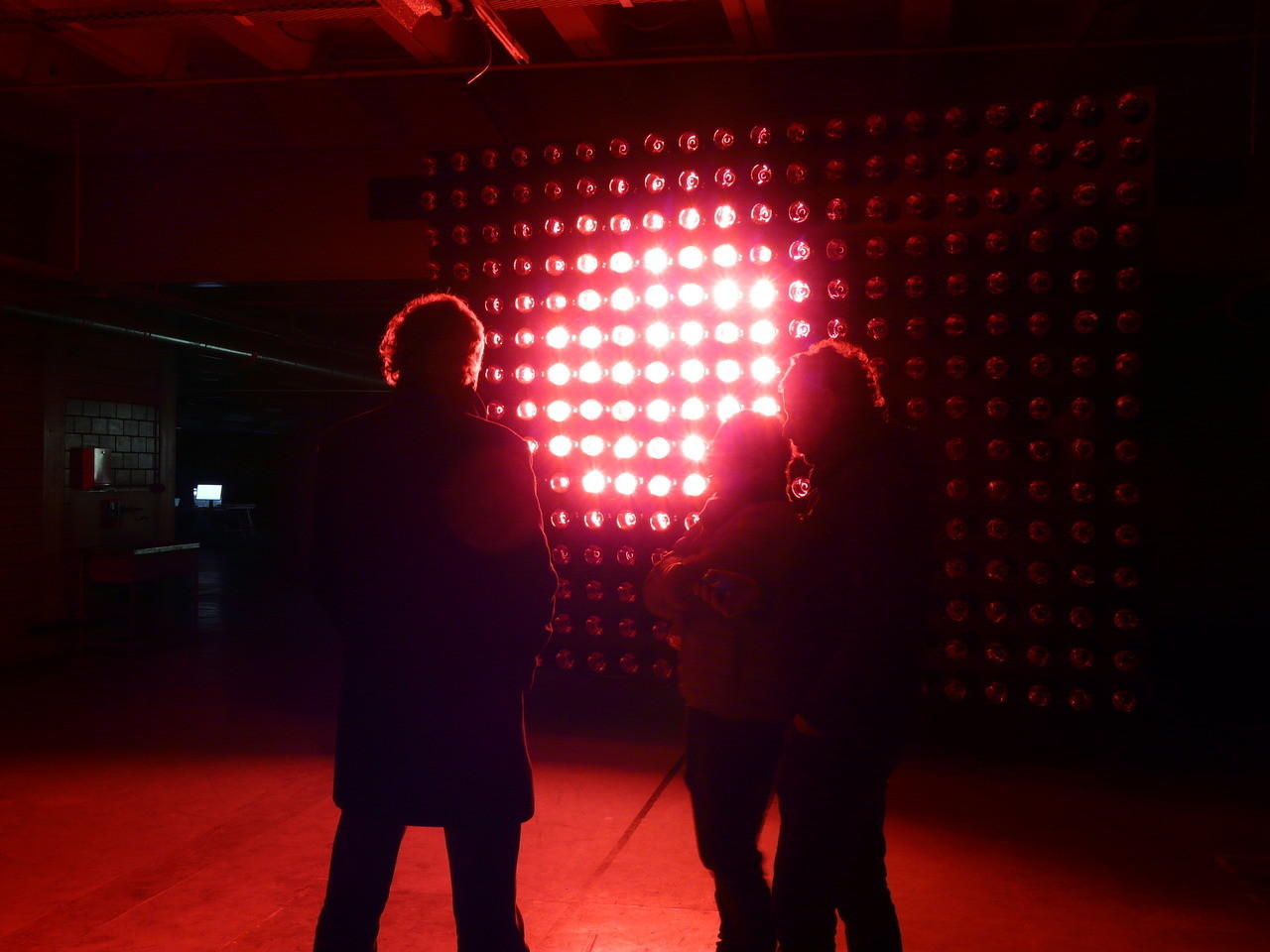

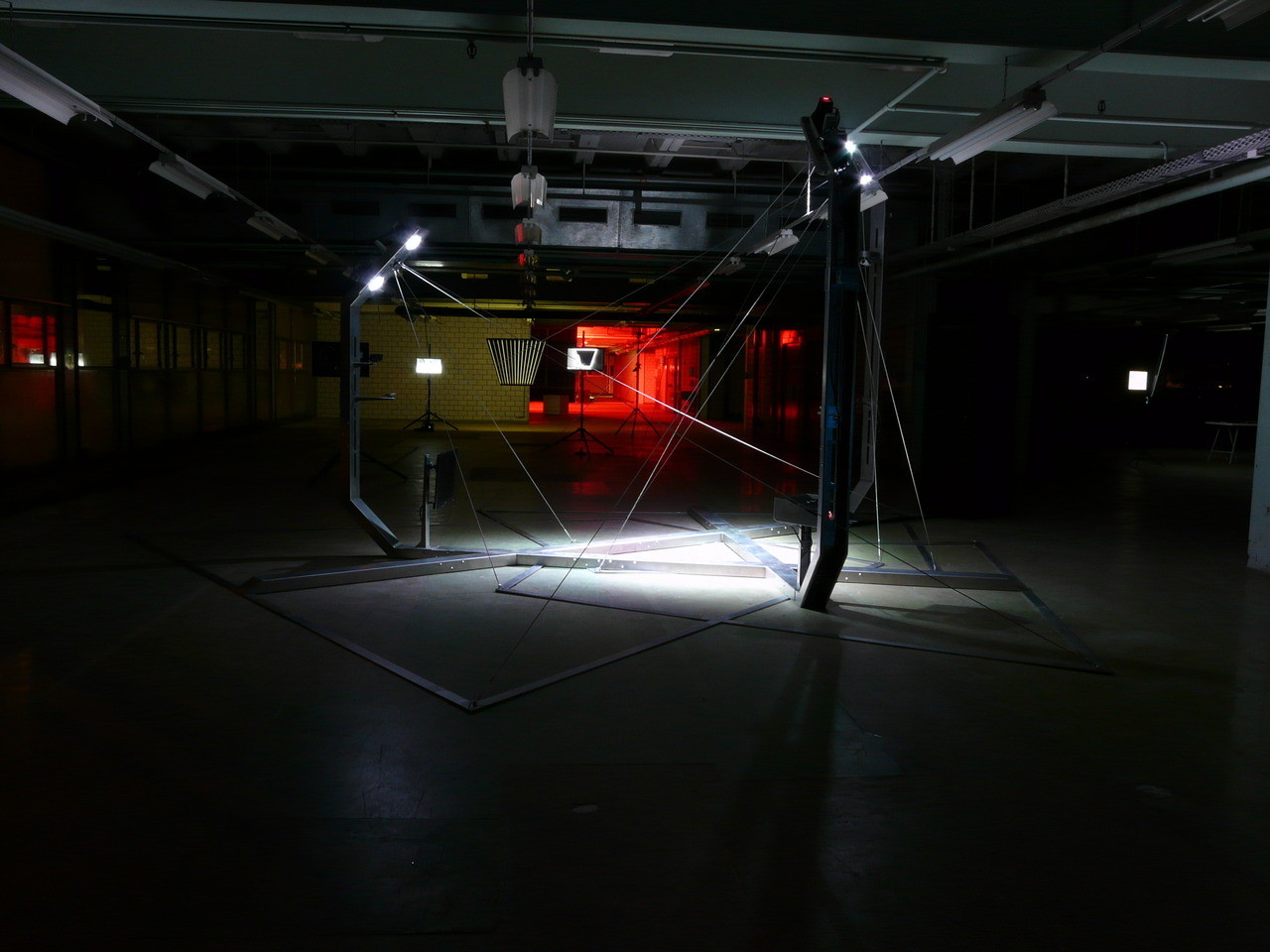

Note: a few pictures from fabric | ch retrospective at #EphemeralKunsthalleLausanne (disused factory Mayer & Soutter, nearby Lausanne in Renens).

The exhibition is being set up in the context of the production of a monographic book and is still open today (Saturday 17.02, 5.00-8.00 pm)!

By fabric | ch

-----

-

All images Ch. Guignard.

Tuesday, October 04. 2016

Note: j'avais évoqué récemment cette idée du sublime dans le cadre d'un workshop à l'ECAL, avec pour invités Random International. Il s'agissait alors d'intervenir dans le cadre d'un projet de recherche où nous visions à développer des "contre-propositions" à l'expression actuelle de quelques-unes de nos infrastructures contemporaines, "douces" et "dures". Le "cloud computing" et les data-centers en particulier (le projet en question, en cours et dont le processus est documenté sur un blog: Inhabiting & Interfacing the Cloud(s)). Un projet conduit en collaboration avec Nicolas Nova de la HEAD - Genève

Tout cela s'était développé autour du sentiment d'une technologie, qui mettant aujourd'hui de nouveau "à distance" ses utilisateurs, contribuerait au développement de "croyances" (dimension "magique") et dans certains cas, à la résurgence du sentiment de "sublime", cette fois non plus lié aux puissances natutrelles "terrifiantes", mais aux technologies développées par l'homme. Je n'avais pas fait le lien avec cette thématique très actuelle de l'Anthropocène, que nous avions toutefois déjà commentée et pointée sur ce blog.

C'est fait dorénavant avec beaucoup de nuances par Jean-Baptiste Fressoz. Non sans souligner que "(...) cette opération esthétique, au demeurant très réussie, n’est pas sans poser problème car ce qui est rendu sublime ce n’est évidemment pas l’humanité, mais c’est, de fait, le capitalisme".

...

On peut aussi se souvenir qu'en 1990 déjà, Michel Serres écrivait dans son livre Le Contrat Naturel:

"Voici maintenant formée la contemporaine société, qu'on peut appeler deux fois mondiale: occupant toute la terre, solidaire comme un bloc, par ses interrelations croisées, elle ne dispose d'aucun reste, de recul ni de recours, ou planter sa tente et dans quel extérieur. Elle sait, d'autre part, construire et utiliser des moyens techniques aux dimensions spatiales, temporelles, énergétiques des phénomènes du monde. Notre puissance collective atteint donc les limites de notre habitat global. Nous commençons à ressembler à la Terre."

Texte que nous avions par ailleurs cité avec fabric | ch dans l'un de nos premiers projets, Réalité Recombinée, en 1998.

Via Mouvements (via Nicolas Nova)

-----

Par Jean-Baptiste Fressoz

Olafur Eliasson à la Tate Modern.

Pour Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, la force de l’idée d’Anthropocène n’est pas conceptuelle, scientifique ou heuristique : elle est avant tout esthétique. Dans cet article, l’auteur revient, pour en pointer les limites, sur les ressorts réactivés de cette esthétique occidentale et bourgeoise par excellence [note: le sublime], vilipendée par différents courants critiques. Il souligne qu’avant d’embrasser complètement l’Anthropocène, il faut bien se rappeler que le sublime n’est qu’une des catégories de l’esthétique, qui en comprend d’autres (le tragique, le beau…) reposant sur d’autres sentiments (l’harmonie, la douleur, l’amour…), peut-être plus à même de nourrir une esthétique du soin, du petit, du local dont l’agir écologique a tellement besoin.

Aussi sidérant, spectaculaire ou grandiloquent qu’il soit, le concept d’Anthropocène ne désigne pas une découverte scientifique [1]. Il ne représente pas une avancée majeure ou récente des sciences du système-terre. Nom attribué à une nouvelle époque géologique à l’initiative du chimiste Paul Crutzen, l’Anthropocène est une simple proposition stratigraphique encore en débat parmi la communauté des géologues. Faisant suite à l’Holocène (12 000 ans depuis la dernière glaciation), l’Anthropocène est marquée par la prédominance de l’être humain sur le système-terre. Plusieurs dates de départ et marqueurs stratigraphiques afférents sont actuellement débattus : 1610 (point bas du niveau de CO2 dans l’atmosphère causé par la disparition de 90% de la population amérindienne), 1830 (le niveau de CO2 sort de la fourchette de variabilité holocénique), 1945 date de la première explosion de la bombe atomique.

La force de l’idée d’Anthropocène n’est pas conceptuelle, scientifique ou heuristique : elle est avant tout esthétique. Le concept d’Anthropocène est une manière brillante de renommer certains acquis des sciences du système-terre. Il souligne que les processus géochimiques que l’humanité a enclenchés ont une inertie telle que la terre est en train de quitter l’équilibre climatique qui a eu cours durant l’Holocène. L’Anthropocène désigne un point de non retour. Une bifurcation géologique dans l’histoire de la planète Terre. Si nous ne savons pas exactement ce que l’Anthropocène nous réserve (les simulations du système-terre sont incertaines), nous ne pouvons plus douter que quelque chose d’importance à l’échelle des temps géologiques a eu lieu récemment sur Terre.

Le concept d’Anthropocène a cela d’intéressant, mais aussi de très problématique pour l’écologie politique, qu’il réactive les ressorts de l’esthétique du sublime, esthétique occidentale et bourgeoise par excellence, vilipendée par les critiques marxistes, féministes et subalternistes, comme par les postmodernes. Le discours de l’Anthropocène correspond en effet assez fidèlement aux canons du sublime tels que définis par Edmund Burke en 1757. Selon ce philosophe anglais conservateur, surtout connu pour son rejet absolu de 1789, l’expérience du sublime est associée aux sensations de stupéfaction et de terreur ; le sublime repose sur le sentiment de notre propre insignifiance face à une nature lointaine, vaste, manifestant soudainement son omnipuissance. Écoutons maintenant les scientifiques promoteurs de l’Anthropocène :

« L’humanité, notre propre espèce, est devenue si grande et si active qu’elle rivalise avec quelques-unes des grandes forces de la Nature dans son impact sur le fonctionnement du système terre […]. Le genre humain est devenu une force géologique globale [2] ».

La thèse de l’Anthropocène repose en premier lieu sur les quantités phénoménales de matière mobilisées et émises par l’humanité au cours des XIXe et XXe siècles. L’esthétique de la gigatonne de CO2 et de la croissance exponentielle renvoie à ce que Burke avait noté : « la grandeur de dimension est une puissante cause du sublime [3] », et, ajoute-t-il, le sublime demande « le solide et les masses mêmes [4] ». De manière plus précise, l’Anthropocène reporte le sublime de la vaste nature vers « l’espèce humaine ». Tout en jouant du sublime, il en renverse les polarités classiques : la terreur sacrée de la nature est transférée à une humanité colosse géologique.

Or, cette opération esthétique, au demeurant très réussie, n’est pas sans poser problème car ce qui est rendu sublime ce n’est évidemment pas l’humanité, mais c’est, de fait, le capitalisme. L’Anthropocène n’est certainement pas l’affaire d’une « espèce humaine », d’un « anthropos » indifférencié, ce n’est même pas une affaire de démographie : entre 1800 et 2000 la population humaine a été multipliée par sept, la consommation d’énergie par 50 et le capital, si on reprend les chiffres de Thomas Picketty, par 134 [5]. Ce qui a fait basculer la planète dans l’Anthropocène, c’est avant tout une vaste technostructure orientée vers le profit, une « seconde nature », faite de routes, de plantations, de chemins de fer, de mines, de pipelines, de forages, de centrales électriques, de marchés à terme, de porte-containers, de places financières et de banques et bien d’autres choses encore qui structurent les flux de matière et d’énergie à l’échelle du globe selon une logique structurellement inégalitaire. Bref, le changement de régime géologique est bien sûr le fait de « l’âge du capital [6] » bien plus que le fait de « l’âge de l’être humain » dont nous rebattent les récits dominants [7]. Le premier problème du sublime de l’Anthropocène est qu’il renomme, esthétise et surtout naturalise le capitalisme, dont la force se mesure dorénavant à l’aune des manifestations de la première nature – les volcans, la tectonique des plaques ou les variations des orbites planétaires – que deux siècles d’esthétique du sublime nous avaient appris à craindre mais aussi à révérer.

Au sublime de la quantité, l’Anthropocène ajoute le sublime géologique des âges et des éons, duquel il tire ses effets les plus saisissants. La thèse de l’Anthropocène nous dit en substance que les traces de notre âge industriel resteront pour des millions d’années dans les archives géologiques de la planète. Le fait d’ouvrir une nouvelle époque taillée à la mesure de l’être humain signifie que c’est à l’échelle des temps géologiques seulement que l’on peut identifier des événements agissant avec autant de force sur la planète que nous-mêmes : le taux de dioxyde de carbone en 2015 est sans précédent depuis trois millions d’années, le taux actuel d’extinction des espèces, depuis 65 millions d’années, l’acidité des océans, depuis 300 millions d’années, etc. Ce que nous vivons n’est pas une simple « crise environnementale », mais une révolution géologique d’origine humaine. Loin de constituer un cours extérieur, impavide et gigantesque, le temps de la Terre est devenu commensurable au temps de l’agir humain. En deux siècles tout au plus, l’humanité a altéré la dynamique du système-terre pour l’éternité ou presque. « Tout ce qui fait transition n’excite aucune terreur [8] » écrivait Burke. Le discours de l’Anthropocène cultive cette esthétique de la soudaineté, de la bifurcation et de l’événement. Le sublime de l’Anthropocène réside précisément dans cette rencontre extraordinaire : deux siècles d’activité humaine, une durée infime, quasi-nulle au regard de l’histoire terrienne, auront suffi à provoquer une altération comparable au grand bouleversement de la fin du Mésozoïque il y a 65 millions d’années.

La troisième source du sublime anthropocénique est le sublime de la violence souveraine de la nature, celle des tremblements de terre, des tempêtes et des ouragans. Les promoteur·rice·s de l’Anthropocène mobilisent volontiers le sublime romantique des ruines, des civilisations disparues et des effondrements : « Les moteurs de l’Anthropocène pourraient bien menacer la viabilité de la civilisation contemporaine et peut-être même l’existence d’homo sapiens [9] ». Le succès artistique et médiatique du concept repose sur la « jouissance douloureuse », sur le « plaisir négatif » dont parle Burke :

« Nous jouissons à voir des choses que, bien loin de les occasionner, nous voudrions sincèrement empêcher… Je ne pense pas qu’il existe un·e ho·femme assez scélérat·e· pour désirer [que Londres] fût renversée par un tremblement de terre… Mais supposons ce funeste accident arrivé, quelle foule accourrait de toute part pour contempler ses ruines [10] ».

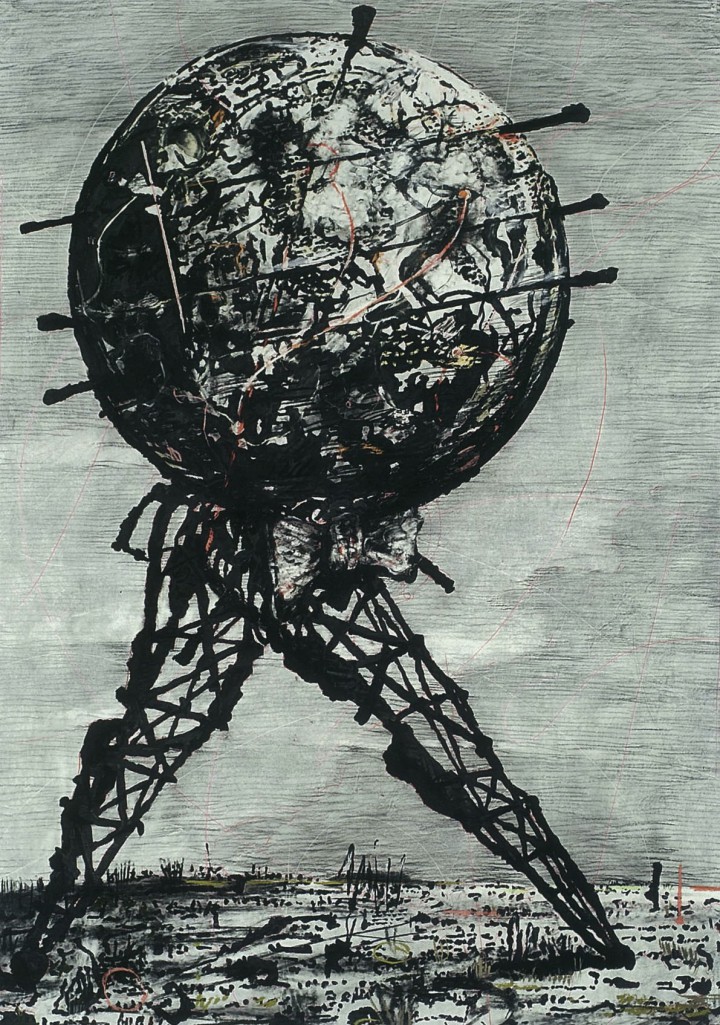

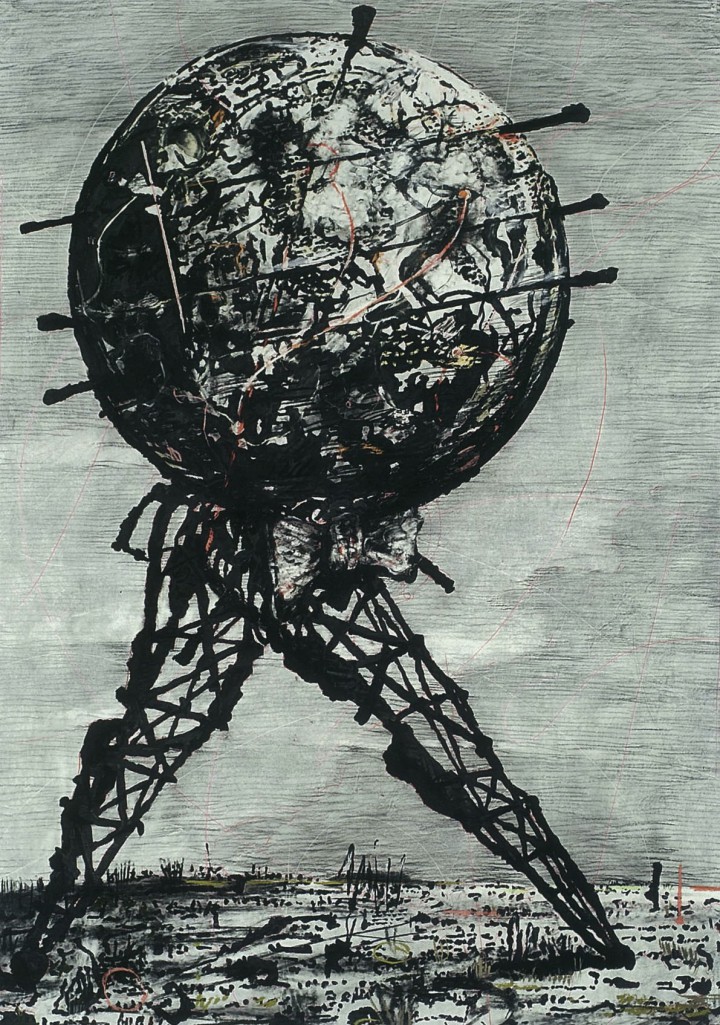

William Kentridge

L’Anthropocène s’appuie sur une culture de l’effondrement propre aux nations occidentales, qui, depuis deux siècles, admirent leur puissance en fantasmant les ruines de leur futur. L’Anthropocène joue des mêmes ressorts psychologiques que le plaisir pervers des décombres déjà décrit par Burke et qui nourrit la vogue actuelle du tourisme des catastrophes de Tchernobyl à ground zero.

La violence de l’Anthropocène est aussi celle de la science hautaine et froide qui nomme les époques et définit notre condition historique. Violence, tout d’abord, de son diagnostic irrévocable : « toi qui entre dans l’Anthropocène abandonne tout espoir » semblent nous dire les savant·e·s. Violence ensuite de la naturalisation, de la « mise en espèce » des sociétés humaines : les statistiques globales de consommation et d’émissions compactent les mille manières d’habiter la terre en quelques courbes, effaçant par la même l’immense variation des responsabilités entre les peuples et les classes sociales. Violence enfin du regard géologique tourné vers nous-mêmes, jaugeant toute l’histoire (empires, guerres, techniques, hégémonies, génocides, luttes, etc.) à l’aune des traces sédimentaires laissées dans la roche. Le géologue de l’Anthropocène est plus effroyable encore que l’ange de l’histoire de Walter Benjamin qui, là même où nous voyions auparavant progrès, ne voyait que catastrophe et désastre : lui n’y voit que fossiles et sédiments.

Que le sublime soit l’esthétique cardinale de l’Anthropocène n’est absolument pas fortuit : sublime et géologie se sont épaulés tout au long de leur histoire. En 1674, Nicolas Boileau traduit en français le traité de Longinus sur le sublime (1er siècle après J.-C.) introduisant ainsi cette notion dans l’Europe lettrée. Mais c’est seulement au milieu du XVIIIe siècle, après que la passion des montagnes et l’intérêt pour la géologie se sont cristallisés dans les classes supérieures, que la « grande nature » devient un objet de sublime [11]. Partis pour leur « grand tour », sur le chemin de l’Italie, les jeunes Anglais·es fortuné·e·s rencontrent en effet la chaîne des Alpes, ses pics vertigineux, ses glaciers terrifiants et ses panoramas immenses. Dans les récits de grands tours, l’expérience de l’effroi face à la nature représente le prix à payer pour goûter la beauté des trésors culturels de l’Italie. Le sublime joue ici un rôle de distinction : être capable de prendre du plaisir en contemplant les glaciers, ou les rochers arides, permettait aux touristes anglais·es de se différencier des guides et des paysan·e·s montagnard·e·s qui n’y voyaient que dangers et terres incultes. Mais c’est évidemment le tremblement de terre de Lisbonne de 1755 qui fournit le véritable coup d’envoi des réflexions sur le sublime : Burke, qui publie son traité l’année suivante, fait référence à la passion esthétique des décombres et des ruines qui saisit alors l’Europe entière. La même année, Emmanuel Kant publie également un court ouvrage sur le tremblement de terre de Lisbonne et, dans son essai ultérieur sur le sublime, il définit ce dernier comme un « plaisir négatif » pouvant procéder de deux manières : le sublime mathématique ressenti devant l’immensité de la nature (l’espace étoilé, l’océan etc.) et le « sublime dynamique » procuré par la violence de la nature (tornade, volcan, tremblement de terre).

Le sublime de l’Anthropocène, et sa mise en scène d’une humanité devenue force tellurique signe la rencontre historique du sublime naturel du XVIIIe siècle et du sublime technologique des XIXe et XXe siècles. Avec l’industrialisation de l’Occident, la puissance de la seconde nature fait l’objet d’une intense célébration esthétique. Le sublime transféré à la technique jouait un rôle central dans la diffusion de la religion du progrès : les gares, les usines et les gratte-ciels en constituaient les harangues permanentes [12]. Dès cette époque, l’idée d’un monde traversé par la technique, d’une fusion entre première et seconde natures fait l’objet de réflexions et de louanges. On s’émerveille des ouvrages d’art matérialisant l’union majestueuse des sublimes naturel et humain : viaducs enjambant les vallées, tunnels traversant les montagnes, canaux reliant les océans, etc. L’idée d’un globe remodelé pour les besoins de l’être humain et fertilisé par la technique constitue une trope classique du positivisme depuis Saint-Simon au moins, qui, dès 1820, écrivait :

« l’objet de l’industrie est l’exploitation du globe, c’est-à-dire l’appropriation de ses produits aux besoins de l’homme, et comme, en accomplissant cette tâche, elle modifie le globe, le transforme, change graduellement les conditions de son existence, il en résulte que par elle, l’homme participe, en dehors de lui-même en quelque sorte, aux manifestations successives de la divinité, et continue ainsi l’œuvre de la création. De ce point de vue, l’Industrie devient le culte [13] ».

De manière plus précise, l’Anthropocène s’inscrit dans une version du sublime technologique reconfigurée par la guerre froide. Il prolonge la vision spatiale de la planète produite par le système militaro-industriel américain, une vision déterrestrée de la Terre saisie depuis l’espace comme un système que l’on pourrait comprendre dans son entièreté, un « spaceship earth » dont on pourrait maîtriser la trajectoire grâce aux nouveaux savoirs sur le système-terre [14]. Le risque est que l’esthétique de l’Anthropocène nourrisse davantage l’hubris d’une géo-ingénierie brutale qu’un travail patient, à la fois modeste et ambitieux d’involution et d’adaptation du social. Pour mémoire, la géo-ingénierie désigne un ensemble de techniques visant à modifier artificiellement le pouvoir réfléchissant de l’atmosphère terrestre pour contrecarrer le réchauffement climatique. Cela peut constituer par exemple à injecter du dioxyde de soufre dans la haute atmosphère afin de réfléchir une partie du rayonnement solaire vers l’espace. L’échec des gouvernements à obtenir un accord international contraignant et ambitieux a contribué à mettre en avant la géo-ingénierie, en tant que « plan B ». Ces techniques potentiellement très risquées pourraient donc soudainement s’imposer en cas « d’urgence climatique ».

Pour ses promoteur·rice·s, l’Anthropocène est une révélation, un éveil, un changement de paradigme désorientant soudainement les représentations vulgaires du monde.

« Par le passé, du fait de la science, l’humanité a dû faire face à de profondes remises en cause de leurs systèmes de croyance. Un des exemples les plus important est la théorie de l’évolution… Le concept d’anthropocène pourrait susciter une réaction hostile similaire à celle que Darwin a produite [15] ».

On retrouve ici le trope romantique du·de la savant·e· payant de sa personne pour lutter contre la foule hostile. En se coupant ainsi du passé et de la décence environnementale commune, en rejetant comme dépassés les savoirs environnementaux qui le précèdent ainsi que les luttes sociales que ces savoirs ont nourries, l’Anthropocène dépolitise l’histoire longue de la destruction de la planète. Avant on ignorait les conséquences globales de l’agir humain, maintenant l’on sait, et, bien entendu, maintenant l’on peut agir. La prétention à la nouveauté des savoirs sur la Terre est aussi une prétention des savants à agir sur celle-ci. Ce n’est pas un hasard si l’inventeur du mot Anthropocène, le prix Nobel de chimie Paul Crutzen, est aussi l’un des avocat·e·s des techniques de géo-ingénierie. À l’Anthropocène inconscient issu de la révolution industrielle succéderait enfin le « bon Anthropocène » éclairé par les savoirs du système-terre. Comme toute forme de scientisme, l’esthétique de l’Anthropocène anesthésie le politique : les « expert·e·s », les autorités vont « faire quelque chose ».

Les expériences du sublime sont toujours à replacer dans un contexte historique et politique particulier. Elles renvoient à des émotions dépendantes des conditions culturelles, naturelles ou technologiques de chaque époque et ce sont ces conditions qui en fournissent les clés de compréhension politique. De la fin du XVIIIe siècle à la fin du siècle suivant, le sublime d’une nature violente et abstraite permettait aux classes bourgeoises urbaines de goûter à la violence de la nature, tout en étant relativement protégées de ses manifestations et de relativiser les dangers bien réels d’un mode de vie technologique et urbain. L’art du sublime nourrissait également le fantasme d’une nature immense et inépuisable au moment précis où l’impérialisme en exploitait les derniers recoins. Dans une culture prenant au sérieux le projet de maîtrise technique de la nature, l’esthétique du sublime fournissait aussi un plaisir légèrement coupable. Enfin, selon le critique marxiste Terry Eagleton, le sublime correspondait aux impératifs esthétiques du capitalisme naissant : contre l’esthétique émolliente du beau, risquant de transformer le sujet bourgeois en sensualiste décadent, le sublime réénergisait le sujet capitaliste comme exploiteur·se ou comme pourvoyeur de travail. Le beau devient à la fin du XVIIIe siècle l’harmonieux, le non-productif, le doux et le féminin ; le sublime : l’effort, le danger, la souffrance, l’élevé, le majestueux et le masculin. Au fond, le sublime, nous dit Eagleton, contenait la menace que la beauté faisait peser sur la productivité [16].

Au début des années 2000, le sublime de l’Anthropocène occupe également une fonction idéologique. Alors que les classes intellectuelles se convertissent au souci écologique, alors qu’elles rejettent les idéaux modernistes de maîtrise de la nature comme has been, alors qu’elles proclament « la fin des grands récits », la fin du progrès, de la lutte des classes, etc., l’Anthropocène procure le frisson coupable d’un nouveau récit sublime. Sur un fond d’agnosticisme quant au futur, l’Anthropocène paraît donner un nouvel horizon grandiose à l’humanité tout entière : prendre en charge collectivement le destin d’une planète. Dans le contexte idéologique terne de l’écologie politique, du développement durable et de la précaution, penser le mouvement d’une humanité devenue force tellurique paraît autrement plus excitant que penser l’involution d’un système économique. Au fond le sublime de l’Anthropocène rejoue assez exactement la scène finale du chef-d’œuvre de Stanley Kubrick, 2001 l’Odyssée de l’espace : l’embryon stellaire contemplant la terre figurant parfaitement l’avènement d’un agent géologique conscient, d’un corps planétaire réflexif. Et c’est bien pour cela que l’Anthropocène fait tressaillir théoricien·ne·s, philosophes et artistes en herbe : il semble désigner un événement métaphysique intéressant.

Pour l’écologie politique contemporaine, l’esthétique sublime de l’Anthropocène pose pourtant problème : en mettant en scène l’hybridation entre première et seconde natures, elle réénergise l’agir technologique des cold warriors (la géo-ingénierie) ; en déconnectant l’échelle individuelle et locale de ce qui importe vraiment (l’humanité force tellurique et les temps géologiques), elle produit sidération et cynisme (no future) ; enfin l’Anthropocène, comme tout autre sublime, est sujet à la loi des rendements décroissants : une fois que l’audience est préparée et conditionnée, son effet s’émousse. En ce sens, désigner une œuvre d’art comme « art de l’Anthropocène » serait absolument fatale à son efficacité esthétique. Le risque est que l’écologie du sublime soit alors appelée à une surenchère permanente, semblable en cela à la course à l’avant-garde dans l’art contemporain. Avant d’embrasser complètement l’Anthropocène, il faut bien se rappeler que le sublime n’est qu’une des catégories de l’esthétique, qui en comprend bien d’autres (le tragique, le beau, le pittoresque…) reposant sur d’autres sentiments (l’harmonie, l’ataraxie, la tristesse, la douleur, l’amour), qui sont peut-être plus à même de nourrir une esthétique du soin, du petit, du local, du contrôle, de l’ancien et de l’involution dont l’agir écologique a tellement besoin.

[1] Cet article reprend sous une forme modifiée un texte déjà paru dans le catalogue de l’exposition Sublime. Les tremblements du monde, Centre Pompidou-Metz, Metz, Centre Pompidou-Metz, 2016.

[2] W. Steffen, J. Grinevald, P. Crutzen, J. McNeill, « The Anthropocene : conceptual and historical perspectives », Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society A, 369, 2011, p. 842–867.

[3] E. Burke, Recherche philosophique sur l’origine de nos idées du sublime et du beau, Paris, Pichon, 1803 (1757), p. 129.

[4] Ibid., p. 225.

[5] T. Piketty, Le capital au XXIe siècle, Paris, Seuil, 2013.

[6] E. Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital : 1848-1975, London, Weindefeld, 1975.

[7] Voir le chapitre « capitalocène » de la nouvelle édition de C. Bonneuil, J.-B. Fressoz, L’événement Anthropocène. La terre, l’histoire et nous, Paris, Seuil, 2016.

[8] E. Burke, op. cit. p. 151.

[9] W. Steffen et al., art. cit.

[10] E. Burke, op. cit., p. 85.

[11] M. Hope Nicholson, Mountain gloom and mountain glory: The development of the aesthetics of the infinite, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1959.

[12] D. Nye, American technological sublime, Cambridge (MA), MIT Press, 1994.

[13] Saint-Simon, Doctrine de Saint-Simon, t. 2, Paris, Aux Bureaux de l’Organisateur, 1830, p. 219.

[14] C. Bonneuil, J.-B. Fressoz, op. cit. ; S. Grevsmühl, La Terre vue d’en haut. L’invention de l’environnement global, Paris, Seuil, 2014.

[15] W. Steffen et al., art. cit.

[16] Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic, Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1990.

Wednesday, September 21. 2016

Note: I would definitely like to do the same (or a bit differently with I-Weather --we almost did back in 2012 during 01SJ in San Francisco in fact, but we were missing a bit of light strength compared to the space--)!

Via Fubiz

-----

The artist Liz West continues inventing original and psychedelic installations, this time as part of the Bristol Biennal. Her project Our Colour is composed of filters that allow the lights to change and is a good way to study the reactions of the human brain when confronted to certain luminous atmospheres. After travelling through all the shades, each person usually ends up enjoying his or her favorite one.

Tuesday, December 23. 2014

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

A Columbia scientist and his startup think they have a plan to save the world. Now they have to convince the rest of us.

By Eli Kintish

CTO and co-founder Peter Eisenberger in front of Global Thermostat’s air-capturing machine.

Physicist Peter Eisenberger had expected colleagues to react to his idea with skepticism. He was claiming, after all, to have invented a machine that could clean the atmosphere of its excess carbon dioxide, making the gas into fuel or storing it underground. And the Columbia University scientist was aware that naming his two-year-old startup Global Thermostat hadn’t exactly been an exercise in humility.

But the reception in the spring of 2009 had been even more dismissive than he had expected. First, he spoke to a special committee convened by the American Physical Society to review possible ways of reducing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere through so-called air capture, which means, essentially, scrubbing it from the sky. They listened politely to his presentation but barely asked any questions. A few weeks later he spoke at the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory in West Virginia to a similarly skeptical audience. Eisenberger explained that his lab’s research involves chemicals called amines that are already used to capture concentrated carbon dioxide emitted from fossil-fuel power plants. This same amine-based technology, he said, also showed potential for the far more difficult and ambitious task of capturing the gas from the open air, where carbon dioxide is found at concentrations of 400 parts per million. That’s up to 300 times more diffuse than in power plant smokestacks. But Eisenberger argued that he had a simple design for achieving the feat in a cost-effective way, in part because of the way he would recycle the amines. “That didn’t even register,” he recalls. “I felt a lot of people were pissing on me.”

The next day, however, a manager from the lab called him excitedly. The DOE scientists had realized that amine samples sitting around the lab had been bonding with carbon dioxide at room temperature—a fact they hadn’t much appreciated until then. It meant that Eisenberger’s approach to air capture was at least “feasible,” says one of the DOE lab’s chemists, Mac Gray.

Five years later, Eisenberger’s company has raised $24 million in investments, built a working demonstration plant, and struck deals to supply at least one customer with carbon dioxide harvested from the sky. But the next challenge is proving that the technology could have a transformative impact on the world, befitting his company’s name.

The need for a carbon-sucking machine is easy to see. Most technologies for mitigating carbon dioxide work only where the gas is emitted in large concentrations, as in power plants. But air-capture machines, installed anywhere on earth, could deal with the 52 percent of carbon-dioxide emissions that are caused by distributed, smaller sources like cars, farms, and homes. Secondly, air capture, if it ever becomes practical, could gradually reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. As emissions have accelerated—they’re now rising at 2 percent per year, twice as rapidly as they did in the last three decades of the 20th century—scientists have begun to recognize the urgency of achieving so-called “negative emissions.”

The obvious need for the technology has enticed several other efforts to come up with various approaches that might be practical. For example, Climate Engineering, based in Calgary, captures carbon using a liquid solution of sodium hydroxide, a well-established industrial technique. A firm cofounded by an early pioneer of the idea, Eisenberg’s Columbia colleague Klaus Lackner, worked on the problem for several years before giving up in 2012.

“Negative emissions are definitely needed to restore the atmosphere given that we’re going to far exceed any safe limit for CO2, if there is one. The question in my mind is, can it be done in an economical way?”

A report released in April by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that avoiding the internationally agreed upon goal of 2 °C of global warming will likely require the global deployment of “carbon dioxide removal” strategies like air capture. (See “The Cost of Limiting Climate Change Could Double without Carbon Capture Technology.”) “Negative emissions are definitely needed to restore the atmosphere given that we’re going to far exceed any safe limit for CO2, if there is one,” says Daniel Schrag, director of the Harvard University Center for the Environment. “The question in my mind is, can it be done in an economical way?”

Most experts are skeptical. (See “What Carbon Capture Can’t Do.”) A 2011 report by the American Physical Society identified key physical and economic challenges. The fact that carbon dioxide will bind with amines, forming a molecule called a carbamate, is well known chemistry. But carbon dioxide still represents only one in 2,500 molecules in the air. That means an effective air-capture machine would need to push vast amounts of air past amines to get enough carbon dioxide to stick to them and then regenerate the amines to capture more. That would require a lot of energy and thus be very expensive, the 2011 report said. That’s why it concluded that air capture “is not currently an economically viable approach to mitigating climate change.”

The people at Global Thermostat understand these daunting economics but remain defiantly optimistic. The way to make air capture profitable, says Global Thermostat cofounder Graciela Chichilnisky, a Columbia University economist and mathematician, is to take advantage of the demand for the gas by various industries. There already exists a well-established, billion-dollar market for carbon dioxide, which is used to rejuvenate oil wells, make carbonated beverages, and stimulate plant growth in commercial greenhouses. Historically, the gas sells for around $100 per ton. But Eisenberger says his company’s prototype machine could extract a concentrated ton of the gas for far less than that. The idea is to first sell carbon dioxide to niche markets, such as oil-well recovery, to eventually create bigger ones, like using catalysts to make fuels in processes that are driven by solar energy. “Once capturing carbon from the air is profitable, people acting in their own self-interest will make it happen,” says Chichilnisky.

Warming up

Eisenberger and Chichilnisky were colleagues at Columbia in 2008 when they realized that they had complementary interests: his in energy, and hers in environmental economics, including work to help shape the 1991 Kyoto Protocol, the first global treaty on cutting emissions. Nations had pledged big cuts, says Chichilnisky, but economic and political realities had provided “no way to implement it.” The pair decided to create a business to tackle the carbon challenge.

They focused on air capture, which was first developed by Nazi scientists who used liquid sorbents to remove accumulations of CO2 in submarines. In the winter of 2008 Eisenberger sequestered himself in a quiet house with big glass windows overlooking the ocean in Mendocino County, California. There he studied existing literature on capturing carbon and made a key decision. Scientists developing techniques to capture CO2 have thus far sought to work at high concentrations of the gas. But Eisenberger and Chichilnisky focused on another term in those equations: temperature.

Engineers have previously deployed amines to scrub CO2 from flue gases, whose temperatures are around 70 °C when they exit power plants. Subsequently removing the CO2 from the amines—“regenerating” the amines—generally requires reactions at 120 °C. By contrast, Eisenberger calculated that his system would operate at roughly 85 °C, requiring less total energy. It would use relatively cheap steam for two purposes. The steam would heat the surface, driving the CO2 off the amines to be collected, while also blowing CO2 away from the surface.

"Even if air capture were to someday prove profitable, whether it should be scaled up is another question."

The upshot? With less heat-management infrastructure than what is required with amines in the smokestacks of power plants, the design of a scrubber could be simpler and therefore cheaper. Using data from their prototype, Eisenberger’s team figures the approach could cost between $15 and $50 per ton of carbon dioxide captured from air, depending on how long the amine surfaces last.

If Global Thermostat can achieve anywhere near the prices it’s touting, a number of niche markets beckon. The startup has partnered with a Carson City, Nevada-based company called Algae Systems to make biofuels using carbon dioxide and algae. Meanwhile the demand is rising for carbon dioxide to inject into depleted oil wells, a technique known as enhanced oil recovery. One study estimates that the application could require as much as 3 billion tons of carbon dioxide annually by 2021, a nearly tenfold increase over the 2011 market.

That still represents a drop in the bucket in terms of the amounts needed to reduce or even stabilize the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere. But Eisenberger says there are really no alternatives to air capture. Simply capturing carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants, he says, only extends society’s dependence on carbon-intensive coal.

Suck it up

It’s a warm December afternoon in Silicon Valley as Eisenberger and I make our way across SRI International’s concrete research center. It’s in these low-slung buildings where engineers first developed ARPAnet, Apple’s Siri software, and countless other technological advances. About a quarter mile from the entrance, a 40-foot-high tower of fans, steel, and silver tubes comes into view. This is the Global Thermostat demonstration plant. It’s imposing and clean. Eisenberger gazes at the quiet scene around the tower, which includes a tall tree. “It’s doing exactly what the tree is doing,” says Eisenberger. But then he corrects himself. “Well, actually, it’s doing it a lot better.”

After Eisenberger earned a PhD physics in 1967 at Harvard, stints at Bell Labs, Princeton, and Stanford followed. At Exxon in the 1980s he led work on solar energy, then served as director of Lamont-Doherty, the geosciences lab at Columbia. There he has taught a long-standing seminar called “The Earth/Human system.” It was in that seminar, in 2007, with Lackner as a guest lecturer, that Eisenberger first heard about air capture. After a year or so of preparation, he and Chichilnisky reached out to billionaire Edgar Bronfman Jr. “Sometimes when you hear something that must be too good to be true, it’s because it is,” was Bronfman’s reaction, according to his son, who was present at the meeting. But the scion implored his father: “If they’re right, this is one of the biggest opportunities out there.” The family invested $18 million.

That largesse has allowed the company to build its demonstration despite basically no federal support for air capture research. (Global Thermostat chose SRI as its site due to the facility’s prior experience with carbon-capture technology.) The rectangular tower uses fans to draw air in over alternating 10-foot-wide surfaces known as contactors. Each is comprised of 640 ceramic cubes embedded with the amine sorbent. The tower raises one contactor as another is lowered. That allows the cubes of one to collect CO2 from ambient air while the other is stripped of the gas by the application of the steam, at 85 °C. For now that gas is simply vented, but depending on the customer it could be injected into the ground, shipped by pipe, or transferred to a chemical plant for industrial use.

A key challenge facing the company is the ruggedness of the amine sorbent surfaces. They tend to decay rapidly when oxidized, and frequently replacing the sorbents could make the process much less cost-effective than Eisenberger projects.

False hope

None of the world’s thousands of coal plants have been outfitted for full-scale capture of their carbon pollution. And if it isn’t economical for use in power plants, with their concentrated source of carbon dioxide, the prospects of capturing it out of the air seem dim to many experts. “There’s really little chance that you could capture CO2 from ambient air more cheaply than from a coal plant, where the flue gas is 300 times more concentrated,” says Robert Socolow, director of the Princeton Environment Institute and co-director of the university’s carbon mitigation initiative.

Adding to the skepticism over the feasibility of air capture is that there are other, cheaper ways to create the so-called negative emissions. A more practical way to do it, Schrag says, would involve deriving fuels from biomass—which removes CO2 from the atmosphere as it grows. As that feedstock is fermented in a reactor to create ethanol, it produces a stream of pure carbon dioxide that can be captured and stored underground. It’s a proven technique and has been tested at a handful of sites worldwide.

Even if air capture were to someday prove profitable, whether it should be scaled up is another question. Say a solar power plant is built outside an existing coal plant. Should the energy the new solar plant produces be used to suck carbon out of the atmosphere, or to allow the coal plant to be shut down by replacing its energy output? The latter makes much more sense, says Socolow. He and others have another concern about air capture: that claims about its feasibility could breed complacency. “I don’t want us to give people the false hope that air capture can solve the carbon emissions problem without a strong focus on [reducing the use of] fossil fuels,” he says.

Eisenberger and Chichilnisky are adamant about the importance of sucking CO2 out of the atmosphere rather than focusing entirely on capturing it from coal plants. In 2010, the pair developed a version of their technology that mixes air with flue gas from a coal or gas-fired power plant. That approach provides a source of steam while capturing both atmospheric carbon and new emissions. It also could lower costs by providing a higher concentration of CO2 for the machine to capture. “It’s a very impressive system, a triumph,” says Socolow, who thinks scientific advances made in air capture will eventually be used primarily on coal and gas power plants.

Such an application could play a critical role in cleaning up greenhouse gas emissions. But Eisenberger has revealed even loftier goals. A patent granted to him and Chichilnisky in 2008 described air capture technology as, among other things, “a global thermostat for controlling average temperature of a planet’s atmosphere.”

Eli Kintisch is a correspondent for Science magazine.

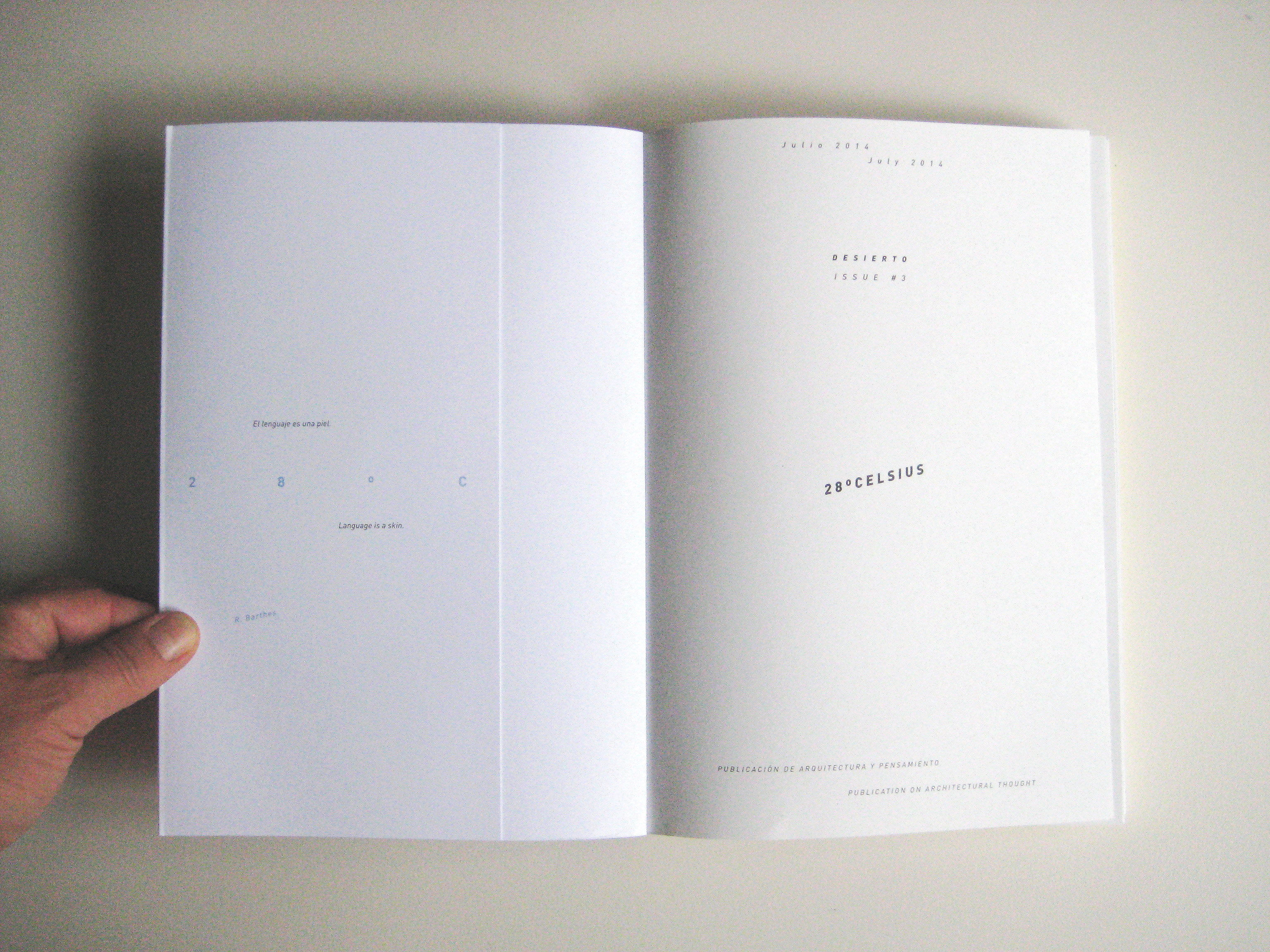

Wednesday, October 08. 2014

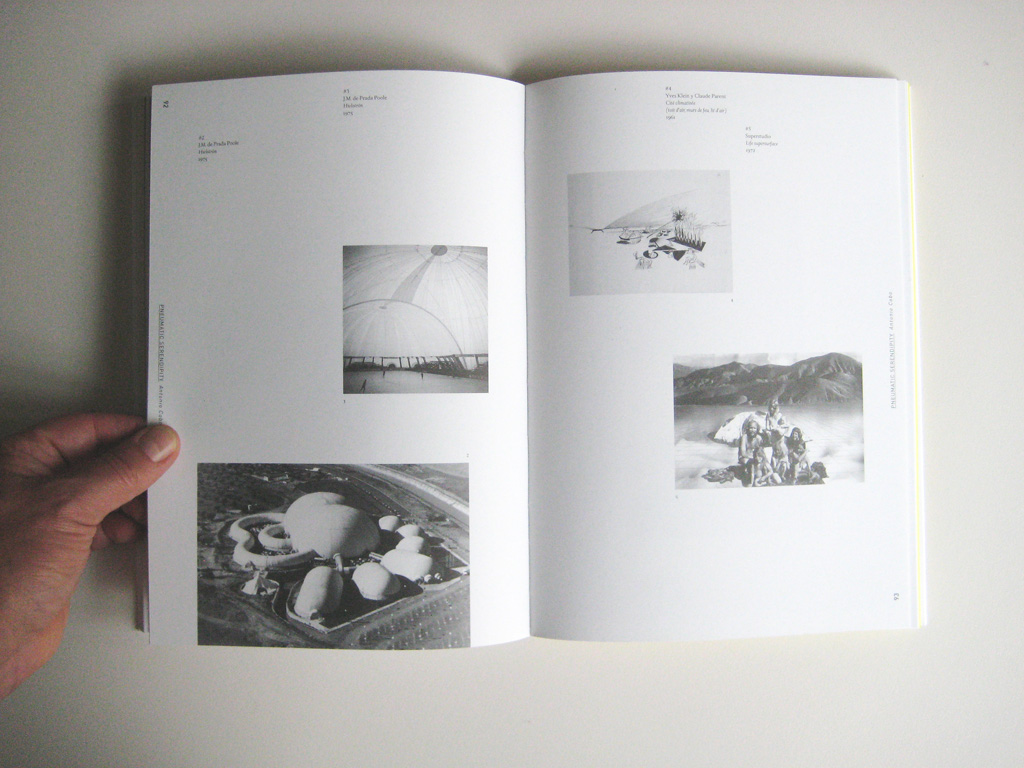

Note: a few of our recent works and exhibitions are included in this promising young publication related to architectural thinking, Desierto, edited by Paper - Architectural Histamine in Madrid. At the editorial team invitation, I had the occasion to write a paper about Deterritorialized Living and one of its physical installation last year in Pau (France), during Pau Acces(s). We also took the occasion of the publication to give a glimpse of a related research project called Algorithmic Atomized Functioning.

By fabric | ch

-----

From the editorial team:

"The temperature of the invisible and the desacralization of the air. 28° Celsius is the temperature at which protection becomes superfluous. It is also the temperature at which swimming pools are acclimatised.

Within the limits of the this hygrothermal comfort zone, we do not require the intervention of our body's thermoregulatory mechanisms nor that of any external artificial thermal controls in order to feel pleasantly comfortable while carrying out a sedentary activity without clothing.

28° Celsius is thus the temperature at which clothing can disappear, just as architecture could."

.jpg)

.jpg)

Authors are Gabriel Ruiz-Larrea, Sean Lally, Philippe Rahm, Nerea Calvillo, myself, Helen Mallinson, Antonio Cobo, José Vella Castillo and Pauly Garcia-Masedo.

.jpg)

Editorial by gabriel Ruiz-Larrea (editor in chief). Editorial team composed of Natalia David, Nuria Úrculo, María Buey, Daniel Lacasta Fitzsimmons.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Inhabiting Deterritorialization, by Patrick Keller, with images of Deterritorialized Living website, Deterritorialized Daylight installation (Pau, France) and Algorithmic Atomized Functioning.

Desierto #3 and past issues can be ordered online on Paper bookstore.

Monday, February 17. 2014

Via BLDGBLOG

-----

[Image: Photo by Danny Lane].

Earlier this winter, I missed an opportunity to travel over to Switzerland with architects Smout Allen and Kyle Buchanan who, at the time, were leading their students around the mountain landscapes of the Alps in order to learn about infrastructures of defense and national snow-production, among other things. It sounded like an amazing trip.

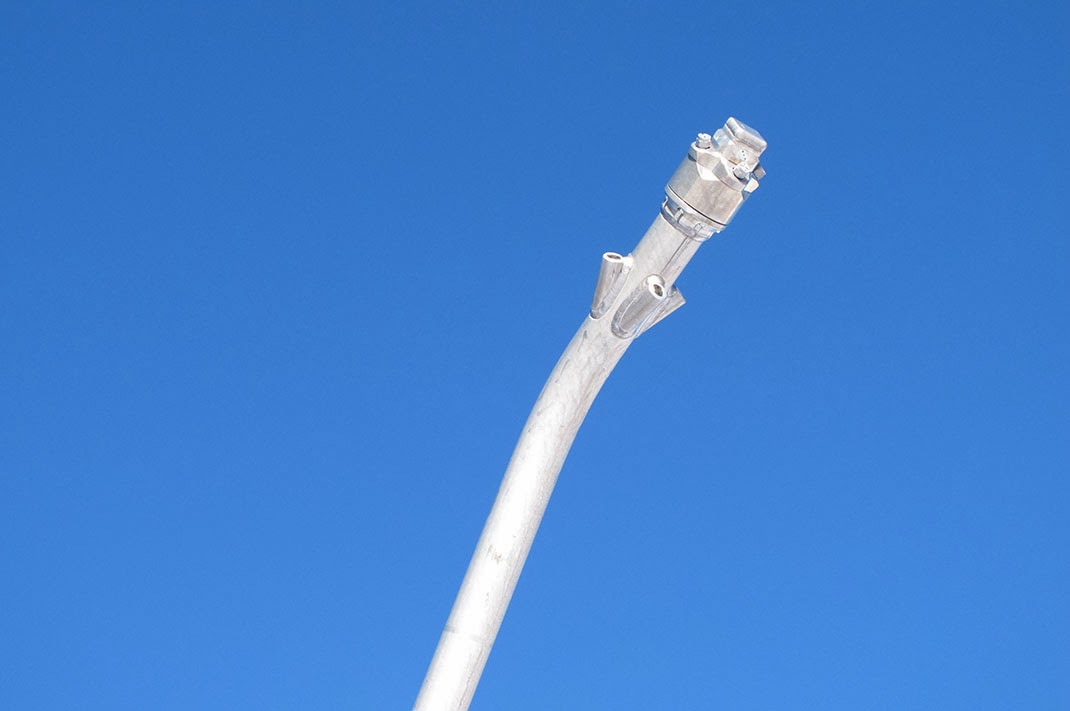

[Image: Photo by Kyle Buchanan].

However, I did get to see some photos sent back of the various and random things they visited in the resort city of Zermatt.

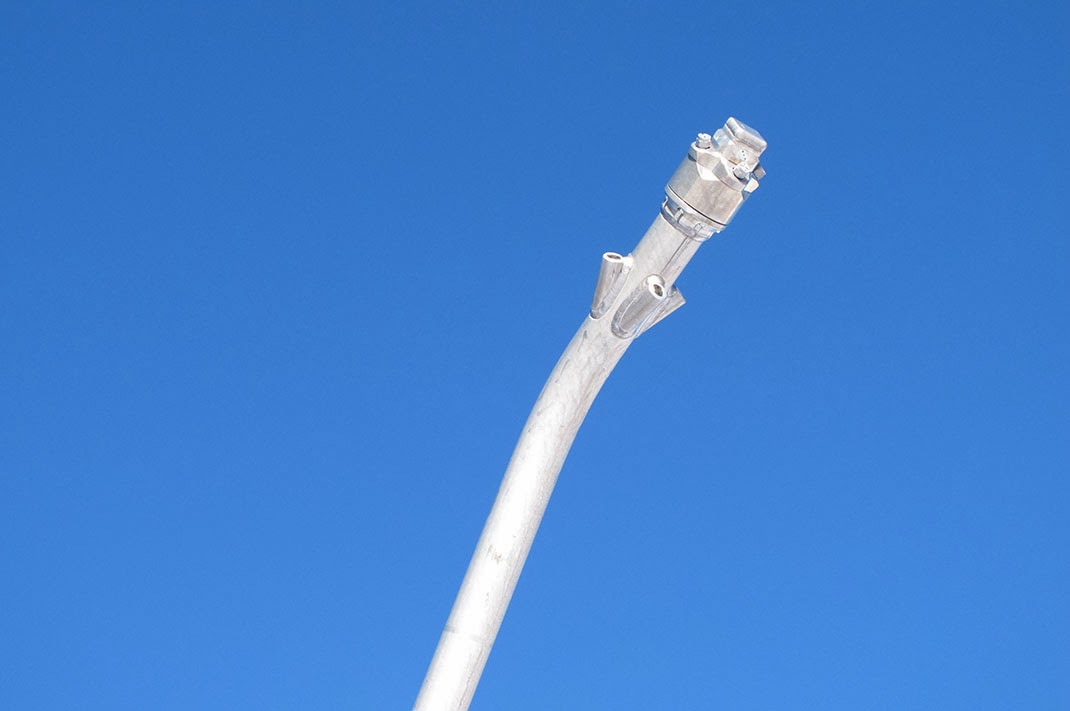

This included a huge machine known as The Snowmaker. Apparently originating in Israel, it was formerly used to cool South African diamond mines but since repurposed for spraying artificial snow onto ski slopes in the Alps.

[Images: Photos by Kyle Buchanan].

The carefully choreographed operation requires a fan-like array of buried water pipes, pipes that spread throughout the resort like capillaries.

Snow—or what passes for it—then sprays out of thin, reed-like valves called "lances"—

[Image: Photo by Kyle Buchanan].

—resulting in other-worldly piles of fresh white powder, perfectly sculpted domes that later require selective placement elsewhere.

[Images: Photos by Danny Lane].

The shaping of the mountain landscape—so easily mistaken for nature—exhibits obvious features of artificiality, including careful lines and striated grooves resulting from deposition, sculpting, and maintenance.

[Image: Photo by Danny Lane].

The machine is literally an oversized air-conditioning unit, waiting to be put to use by landscape-printing crews whose work is mistaken for winter. It so efficiently—though inadvertently—produced ice while cooling diamond mines in Africa that it has since been put to use 3D-printing popular tourist landscapes into existence, like something out of Dr. Seuss.

To at least some extent, The Snowmaker—and newer technology like it—has replaced older, fan-based snow machines. These thus now sit in a maintenance shed, like antique airplane engines, both derelict and obsolete.

[Image: Photo by Danny Lane].

This is all just part of the dramaturgical stagecraft of Switzerland: winter becomes a precisely choreographed thermal event that just happens to take on spatial characteristics amenable to downhill skiing.

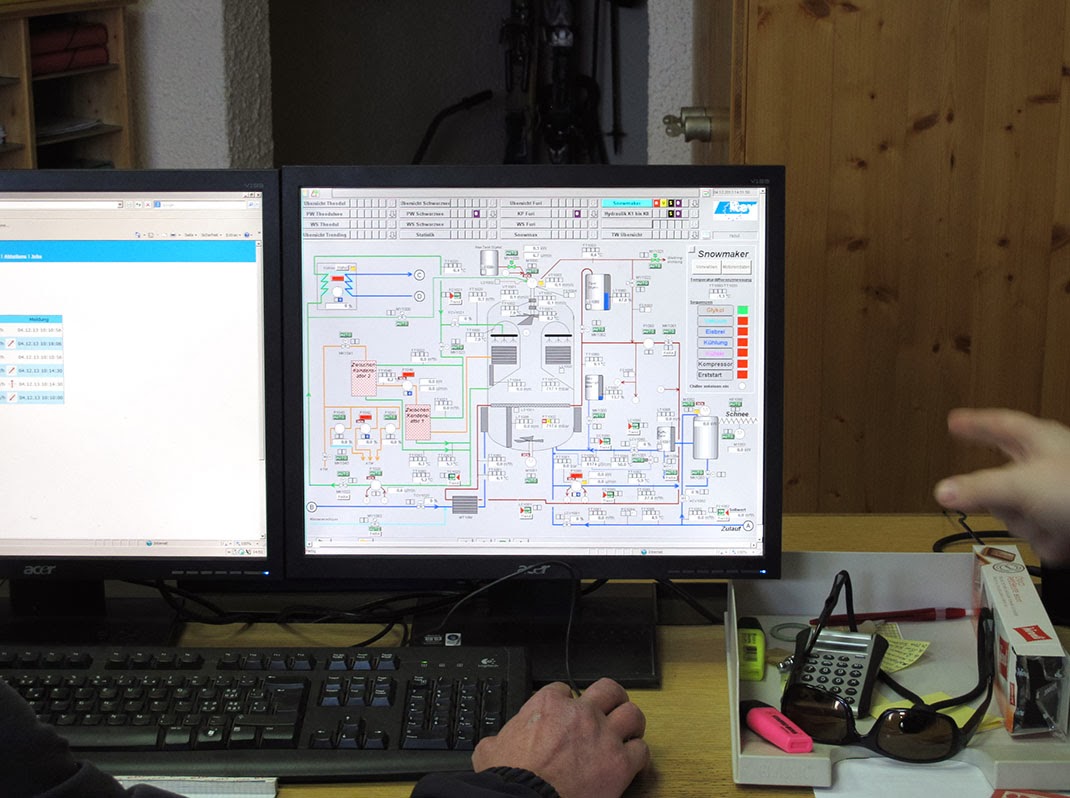

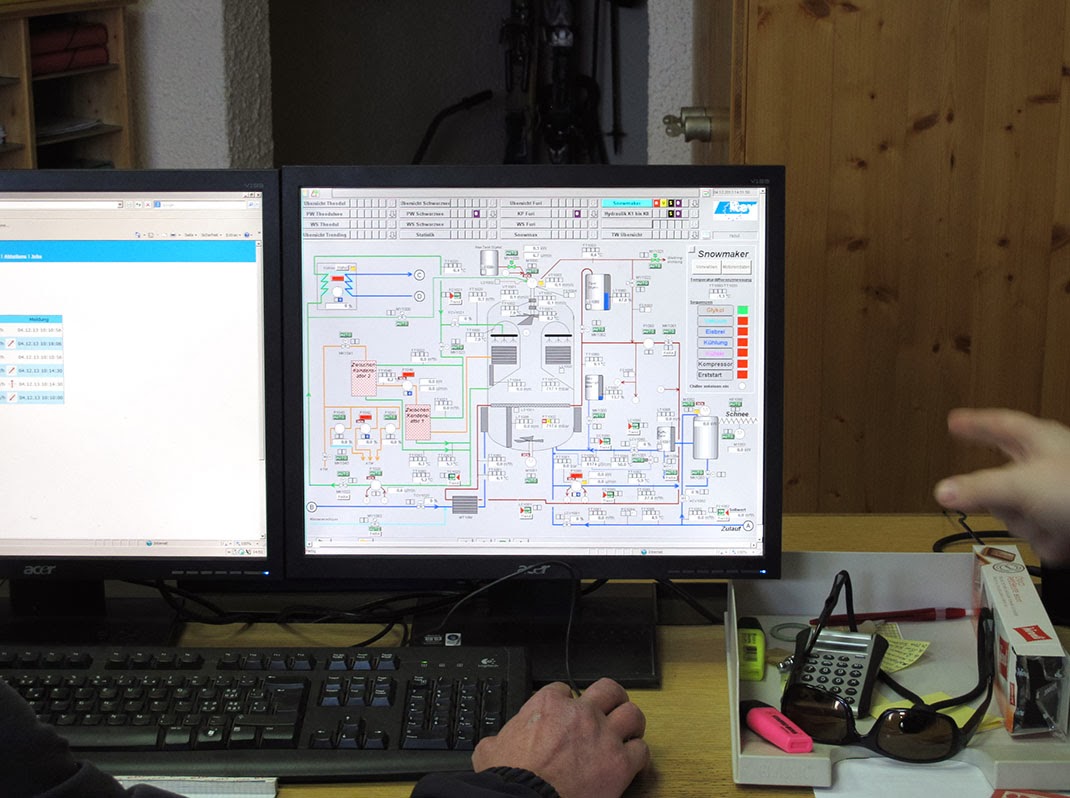

In any case, there are nearly 1,000 individual snow-production machines in Zermatt, only one of which is The Snowmaker. The whole system is controlled from a central computer, apparently operated by one wizard-like figure who is really just a stoned twentysomething in a wool hat, turning different parameters on and off and spraying whole new European landscapes into existence outside.

[Images: (top) Photo by Danny Lane; (bottom) photo by Kyle Buchanan].

It's like the Sorcerer's Apprentice at the top of the world, 3D-printing recreational mountainscapes. The landscape is a computer he alone knows how to use.

Imagine if Thomas Mann's Magic Mountain had taken place amidst a massive, artificially maintained and 3D-printed winter, and you might begin to grasp the unearthly strangeness here, the surreal mechanical goings-on at great altitude.

What appears, at first glance, to be a simple ski holiday actually turns out, upon later inspection, to be a landscape-scale encounter with artificiality and snow-based 3D-printing.

(See also Gizmodo, where these photographs were first published; thanks to Mara Kanthak for her help with translation in Switzerland).

Wednesday, February 12. 2014

While browsing around on the Internet, I found the remnants of this exhibition that took place in Yamaguchi Center for the Arts and Media in Tokyo back in 2010. To my big ignorance, I didn't know the work of Fujiko Nakaya dating back from the 1970ies. Now I do and I can see how far Blur, Diller & Scofidio's famous building (during Expo.01 in Switzerland back in 2001), was pushing Nakaya's ideas one step further/bigger.

Via Yamaguchi Center for the Arts & Media

-----

Artistic environmental spheres formed by fog, light and sound

Large-scale project unveiled simultaneously in three public spaces in and around YCAM

The upcoming CLOUD FOREST exhibition at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM] presents examples of newly discovered environmental creation, realized with an "artistic environments" themed fusion of artistic expression and information technology. Currently on show in three different public spaces in and around YCAM will be a large-scale collaborative project featuring "fog sculptures" by Fujiko Nakaya, an artist whose works have gained much attention at various occasions in Japan and overseas, along with the original light and sound art of Shiro Takatani.

These commissioned installations conceived in-residence at YCAM combine artificial fog, sunlight and sound, orchestrating with the help of originally developed devices and responding to changing weather conditions a variety of impressive sceneries. Visitors can experience transformations in their perception as they interact with artworks incorporating information technology while walking in the fog in the patios or surrounding park. While introducing and reevaluating foresighted art and science projects originally presented at the EXPO'70 Osaka, which eventually inspired this new project, the exhibition anticipates the future of environmental creation, "informational spheres" of tomorrow, and possible creative quests through art.

Related events

Opening events

Demonstrative Performance

August 7 (sat) 19:00 - 20:00

Venue: Foyer, Patios Admission free

Artists: Fujiko Nakaya, Shiro Takatani, softpad (Takuya Minami, Tomohiro Ueshiba, Hiroshi Toyama) In addition to Fujiko Nakaya and Shiro Takatani, the members of Kyoto-based art/design collective softpad, who took charge of the sound design for this exhibition, participate in a special experimental live performance incorporating the fog, light and sound installations in the patios and foyer.

Artist Talk

August 8 (san) 14:00-16:00

Venue: Studio B Admission free

Guests: Fujiko Nakaya, Shiro Takatani Moderator: Akira Asada

Artists involved in this exhibition appear as special guests in a casual talk session that gives them the opportunity to introduce their works. Moderator will be Akira Asada, a specialist in the field who is familiar with each artist's endeavors to date. While referring to the work of E.A.T. at the 1970 Osaka Expo's Pepsi Pavilion, which inspired this project in the first place, the artists will look back at such trailblazing achievements as Nakaya's "fog sculptures" and David Tudor's soundscapes originally presented at the Expo, and discuss the developments and prospects now, four decades later.

* There will be guided gallery tours offered during the period of the exhibition. Please check the exhibition website for more information on additional event.

Cloud Forest

Prospects of art-inspired new environmental creation

Rather than addressing "environmental" issues only from an ecological point of view, this "artistic environmental spheres" themed exhibition focuses on the mutual relationships between natural, social, mental and informational environments. Aiming to provide a stage for such diverse aspects of the subject matter to function as interfaces for each other, CLOUD FOREST pursues a contemporary form of environmental creation triggered off by transformations in human perception. The shifting perceptual experience of interacting with artworks incorporating information technology and YCAM's architectural characteristics makes the visitor aware of spatial transfigurations, and ultimately commands ideas related to "environments" of the future.

Fujiko Nakaya "Fog Sculpture #47773" Pepsi Pavilion Commissioned by Experiments in Art and Technology (EXPO' 70, Osaka, Japan 1970). Photo: ©Takeyoshi Tanuma

Environment as an art form

This exhibition is based on a definition of "environment" as a compound of mutually generative, penetrative and reflective areas. While there have been various movements in the past that proposed environments as stages for or components of art, such as land art or earth art, this exhibition aims to explore the creative aspects of media art for possible new forms of "environments". Think of it as an attempt to generate with the help of information technology open environments embracing multiple interlinked, mutually "environmental spheres". In this day and age, the concept of "environments" manifested through spatial transformations is surely going to write its own quiet yet forceful story.

40 years after the EXPO'70 Osaka: E.A.T. reinterpreted from a contemporary point of view

E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) attracted worldwide attention when the American experimental collective presented their work in the Pepsi Pavilion at the EXPO'70 Osaka. At this huge international event, the group of collaborating artists and scientists presented the astonishing results of their pioneering exploration of the relationship between environment and art, driven by the participating artists' innovative ideas. Considering the 40 years between then and the present day as a fundamental period of transition from the material productivity-based viewpoints of progressive science to invisible information capitalism, this exhibition attempts a critical review of the ideas and accomplishments of E.A.T. By interpreting such forward-thinking approaches of art and science with an eye on contemporary information society and perspectives of environmental creation, we aim to disclose a contemporary form of reality and its new environmental components.

"Island Eye Island Ear" Project by Experiments in Art & Technology (Knavelskar Island, Sweden 1974). Photo: Fujiko Nakaya

Environments emerging out of human perception and networking technology

This exhibition couples the "fog sculptures" of Fujiko Nakaya with the creative ideas of the late David Tudor, who was in charge of interactive sound when Nakaya's works were first introduced at the EXPO'70 Osaka's Pepsi Pavilion. The "fog sculptures" take on a variety of appearances at the main venues in and around YCAM, shown alongside a new installation piece incorporating Tudor's original concept of soundscapes based on environmental reverberation. Altogether, the displays can be considered as a collaborative attempt of new environmental creation, undertaken by Fujiko Nakaya together with the YCAM staff and such post-Expo generation artists as Shiro Takatani. These works utilizing information technology to incorporate in various ways transformations of both natural surroundings and human perception communicate a sensory idea of critical, totally new "spheres of artistic environments".

Fujiko Nakaya "GREENLAND GLACIAL MORAINE GARDEN" (Nakaya Ukichiro Museum of Snow and Ice,Kaga City, Japan 1994). Photo: Rokuro Yoshida

Cloud Forest

The exhibition's title, "CLOUD FOREST" is borrowed from the name of a subtropical forestal area that is characterized by a frequent formation of mist about the canopy level. It is a place that can be considered as a peculiar zone of active interpenetration right in the middle between wild nature and the realm of human society.

At the same time, the title is a reference to David Tudor's sound installation/performance piece "Rainforest". Approaching the laws of nature by means of cutting-edge technology, this exhibition pays deep homage also to the innovativeness of the "Island Eye Island Ear" project that Fujiko Nakaya conceived with Jacqueline Monnier back in the 1970s.

Environmental spheres in three installations

Patios... Interfaces of fog, light and sound

The entirely glass-walled patios - high open spaces that allow wind, rain and sunlight to fall in - are intermediate places combining/connecting the outside (natural environment) with the inside (artificial environment). This exhibition includes large-scale installations involving artificial fog, light (reflected sunlight) and sound, which transform the Center's two patios into interfaces between two different types of environments.

Influenced by the surrounding interior and exterior environments, the artificial fog that is emitted in varying intervals from multiple directions forms convections of various modes and configurations. In addition, a special mirror device is used to redirect sunbeams into the fog. As optical effects will vary significantly according to the fog's configuration, meteorological conditions, and the position of the sun, the displays will continue to take on different appearances depending on the time, position and angle. As locations, sizes, and positions of installed apparatus are different in both patios, visitors can appreciate two completely different installations. Furthermore, special sound systems installed inside the exhibition spaces allows visitors to perceive the soundscapes locally while walking.

"Cloud Forest" [Patio] (YCAM 2010)

"Cloud Forest" [Central Park] (YCAM 2010)

Also on display are photographs and video footage of previous works related to this exhibition (Fujiko Nakaya & David Tudor, EXPO'70 Osaka "Pepsi Pavilion", etc.)

Friday, January 31. 2014

With some delay...

Via Mammoth

-----

[The Audubon Society's micro-dredger, the John James, making new land in the Paul J. Rainey Wildlife Sanctuary in South Louisiana. Karen Westphal, Audubon’s Atchafalaya Basin program manager, will be speaking about this participatory micro-dredging project at DredgeFest Louisiana's symposium, which is this Saturday and Sunday at Loyola University in New Orleans.]

Tim Maly and I explain why we’re holding DredgeFest in Louisiana this coming weekend (and following week) for Gizmodo:

…south Louisiana is disappearing—terrifyingly fast. Sea-level rise, salt water intrusion, and canal excavation for industrial purposes have all combined with the constrainment of the river via flood control infrastructures to radically alter the balance between deposition, subsidence, and erosion. Instead of growing, the delta is now shrinking. Louisiana has lost over 1700 square miles of land (an area greater than the state of Rhode Island) since 1930. Without a change in course, it is anticipated to double that loss in the next fifty years. By 2100, subsidence, erosion, and sea level rise are projected to combine to leave New Orleans little more than an island fortress, effectively isolated in the rising Gulf of Mexico.

Moreover, even where the land itself may not be entirely submerged, the loss of barrier islands and coastal marshes exposes human settlements ever more precariously to the vicious effects of hurricanes and tropical storms, including the destructive waves known as storm surge.

This situation is entirely untenable. You thought Katrina was a terrible disaster? (It was.) Imagine what happens to New Orleans when a Category 6 hurricane hits in 2086, when even the highest ground in the French Quarter and the Garden District is barely above sea level and well below the ever-thickening barriers the Army Corps will throw up to protect America’s newest island.

In response to this apocalyptic but plausible threat, Louisiana is engaging in the world’s first large-scale experiment in restoration sedimentology. With the aid of components of the federal government like the Army Corps of Engineers and a bounty of funds earmarked for coastal restoration and protection as a result of payments owed by BP for the damages wrought by the 2010 Deep Horizon oil disaster, Louisiana has accelerated its nascent crash-program in experimental land-making machines, rapidly prototyping a wide array of weird and wonderful techno-infrastructural strategies for building land. This is an effort to cobble together a synthetic analog to the land-making machine that the Mississippi once was. If you want to understand the future of coastlines and deltas in a world of rising seas and surging storms, you should pay close attention to what is happening in Louisiana.

Read the full piece at Gizmodo. (And, if you’re able, come to DredgeFest Louisiana!)

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)