Sticky Postings

All 242 fabric | rblg updated tags | #fabric|ch #wandering #reading

By fabric | ch

-----

As we continue to lack a decent search engine on this blog and as we don't use a "tag cloud" ... This post could help navigate through the updated content on | rblg (as of 09.2023), via all its tags!

FIND BELOW ALL THE TAGS THAT CAN BE USED TO NAVIGATE IN THE CONTENTS OF | RBLG BLOG:

(to be seen just below if you're navigating on the blog's html pages or here for rss readers)

--

Note that we had to hit the "pause" button on our reblogging activities a while ago (mainly because we ran out of time, but also because we received complaints from a major image stock company about some images that were displayed on | rblg, an activity that we felt was still "fair use" - we've never made any money or advertised on this site).

Nevertheless, we continue to publish from time to time information on the activities of fabric | ch, or content directly related to its work (documentation).

Wednesday, March 23. 2016

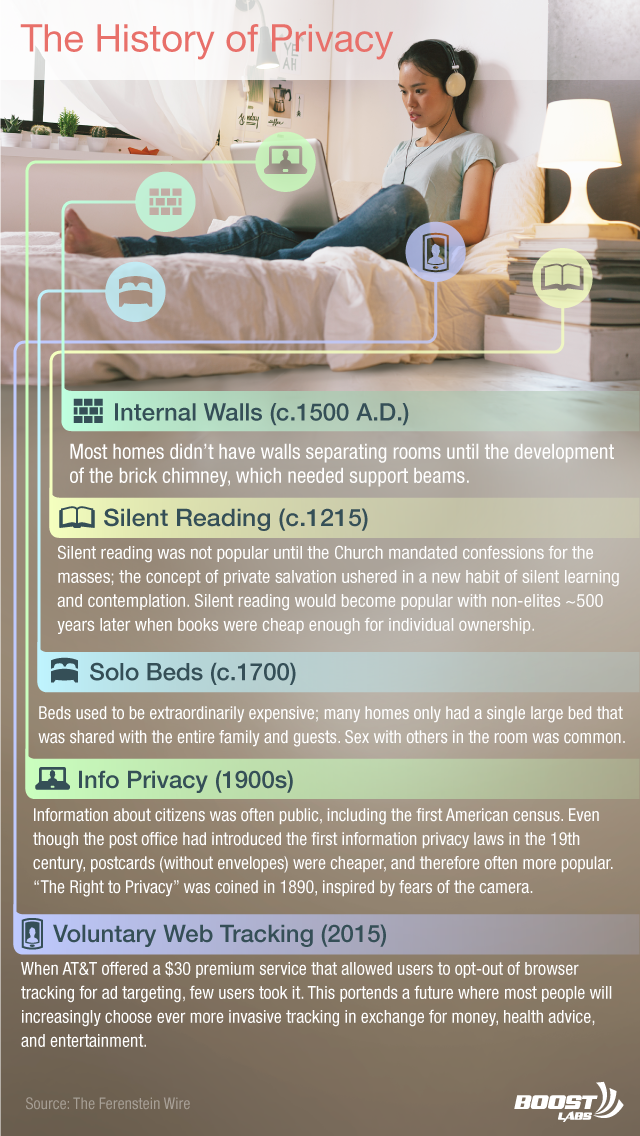

The Birth And Death Of Privacy: 3,000 Years of History Told Through 46 Images | #privacy #transparency #history

Note: to put things in perspective, especially in the private-public data debate, it is interesting to start digg into the history of privacy, or how, where and when it possibly came from... So as how, where and when it will possibly vanish...

The following article was found on Medium, written by journalist Greg Ferenstein. It has some flaws (or rather some quick shortcuts due to its format) and seems driven by the statement that the natural state of human beings is "transparency/no privacy", but it also doesn't pretend to be a scientific final story about privacy. It is rather instead a point of view and a relatively brief introduction by a writer, considering the large period adressed (to start digg in then). It is not a detailed paper by an historian specialized into this topic.

The article should be taken with a bit of critical distance therefore. Especially, to my reader's point of view, there are missing arguments regarding the fact that "privacy" is obviously not mainly "physical privacy" (walls, curtains, etc.), or not anymore for a long time. It certainly started as physical privacy -- as the author demonstrates it well -- but at a critcal point, this gained privacy, this evolution from a state of "no privacy" helped guarantee a certain freedom of thinking that became therefore highly related to the foundation of our "democratic" political system, to the "enlightenment" period as well.

And this is the main element regarding this question according to me. Loosing one could also clearly mean loosing the other... (if it's not already lost... a subject that could be debated as well, not to speculate further to know if a different system could emerge from this nor not, maybe even an "egalitarian" one).

Also, to state as a conclusion (last 7 lines) that our "natural state" is to be "transparent" (state of no privacy) and that the actual move toward "transparency" is just a manner to go "naturally" back to what it always was is a bit intellectually lazy: the current "transparency" that is pushed mainly by big corporations and also by States for security reasons --as stated, "law enforcements" of many sorts-- is not the old "passive" transparency but a highly "dynamic", computed, processed, and often merchandised one.

It has nothing to do with the old "all the family lives naked with their nurturing animals in the same room" sort of argument then... It is a different system, not democratc anymore but a mix of ultra liberalism and monitored surveillance. Not a funny thing at all...

So, all in all, the arguments in the article remain very interesting, related to many contemporary issues and there are several useful resources as well in there. But you should definitely keep your brain "switch on" while reading it!

Via Medium

-----

Jean-Leon Gerome, The Large Pool Of Bursa

2-Minute Summary ...

- Privacy, as we understand it, is only about 150 years old.

- Humans do have an instinctual desire for privacy. However, for 3,000 years, cultures have nearly always prioritized convenience and wealth over privacy.

- Section II will show how cutting edge health technology will force people to choose between an early, costly death and a world without any semblance of privacy. Given historical trends, the most likely outcome is that we will forgo privacy and return to our traditional, transparent existence.

*This post is part of an online book about Silicon Valley’s Political endgame. See all available chapters here.

SECTION I:

How privacy was invented slowly over 3,000 years

“Privacy may actually be an anomaly” ~ Vinton Cerf, Co-creator of the military’s early Internet prototype and Google executive.

Cerf suffered a torrent of criticism in the media for suggesting that privacy is unnatural. Though he was simply opining on what he believed was an under-the-radar gathering at the Federal Trade Commission in 2013, historically speaking, Cerf is right.

Privacy, as it is conventionally understood, is only about 150 years old. Most humans living throughout history had little concept of privacy in their tiny communities. Sex, breastfeeding, and bathing were shamelessly performed in front of friends and family.

The lesson from 3,000 years of history is that privacy has almost always been a back-burner priority. Humans invariably choose money, prestige or convenience when it has conflicted with a desire for solitude.

Tribal Life (~200,000 B.C. to 6,000 B.C)

Flickr user Rod Waddington

"Because hunter-gatherer children sleep with their parents, either in the same bed or in the same hut, there is no privacy. Children see their parents having sex. In the Trobriand Islands, Malinowski was told that parents took no special precautions to prevent their children from watching them having sex: they just scolded the child and told it to cover its head with a mat" - UCLA Anthropologist, Jared Diamond

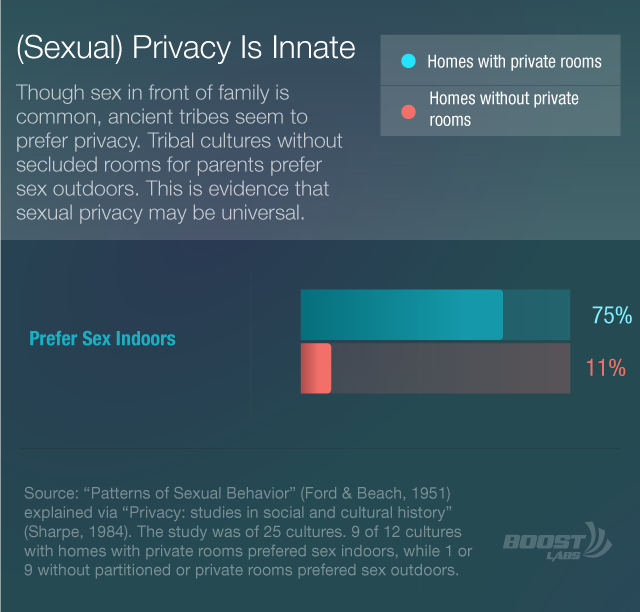

While extremely rare in tribal societies, privacy may, in fact, be instinctive. Evidence from tribal societies suggests that humans prefer to make love in solitude (In 9 of 12 societies where homes have separate bedrooms for parents, people prefer to have sex indoors. In those cultures without homes with separate rooms, sex is more often preferred outdoors).

However, in practice, the need for survival often eclipses the desire for privacy. For instance, among the modern North American Utku’s, a desire for solitude can seem profoundly rude:

Inuit family. Source: Wikipedia Ansgar Walk

...

"It dawned on me how forlorn I would be in the wildness if they forsook me. Far, far better to suffer loss of privacy” - Anthropologist Jean Briggs, on being ostracized by her host Utku family, after daring to explore the wilderness alone for a day.

...

The big question: if privacy isn’t the norm, where did it start? Let’s start from the first cities:

Ancient Cities (6th Century B.C. — 4th Century AD)

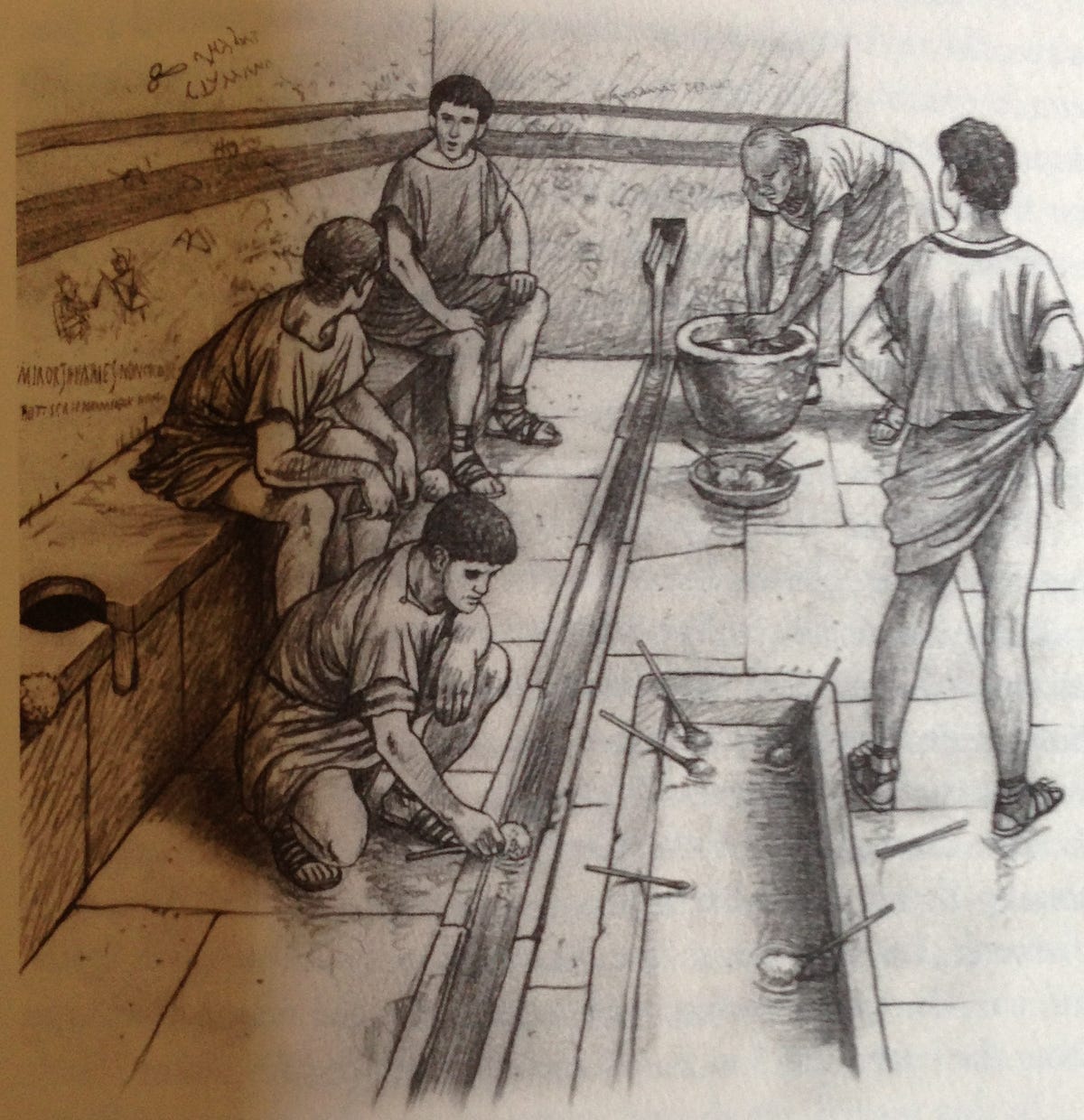

Image: Roman citizens engaged in conversation in a public restroom. Credit: A Day In The Life Of Ancient Rome

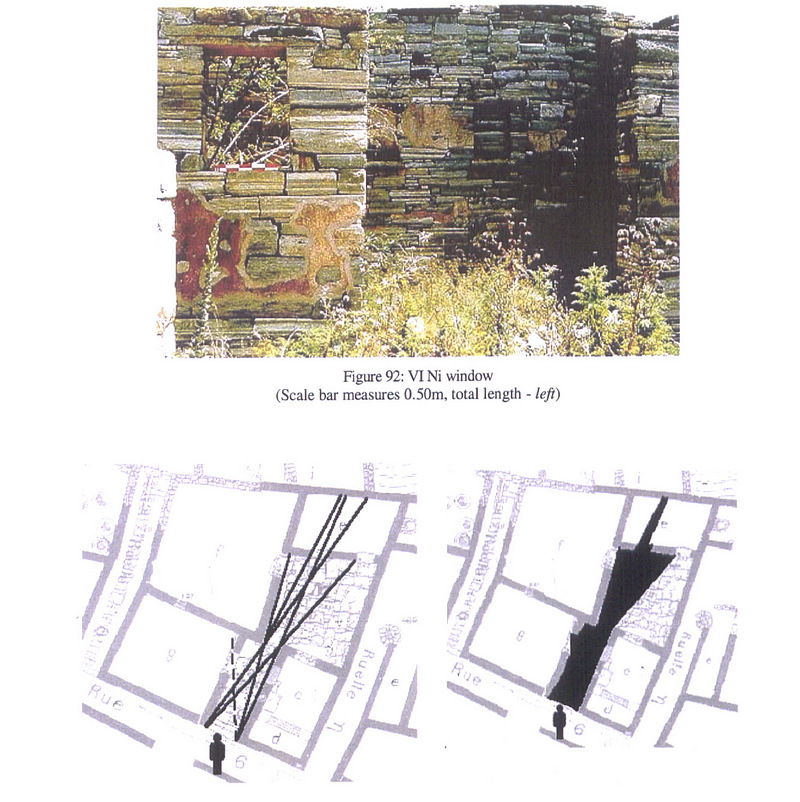

Like their tribal ancestors, the Greeks displayed some preference for privacy. And, unlike their primitive ancestors, the Greeks had the means to do something about it. University of Leicester’ Samantha Burke found that the Greeks used their sophisticated understanding of geometry to create housing with the mathematically minimum exposure to public view while maximizing available light.

Sightline analysis of maximum viewable space from the street. Burke (2000)

“For where men conceal their ways from one another in darkness rather than light, there no man will ever rightly gain either his due honour or office or the justice that is befitting” - Socrates

Athenian philosophy proved far more popular than their architecture. In Greece’s far less egalitarian successor, Rome, the landed gentry built their homes with wide open gardens. Turning one’s house into a public museum was an ostentatious display of wealth. Though, the rich seemed self-aware of their unfortunate trade-off:

“Great fortune has this characteristic, that it allows nothing to be concealed, nothing hidden; it opens up the homes of princes, and not only that but their bedrooms and intimate retreats, and it opens up and exposes to talk all the arcane secrets” ~ Pliny the Elder, ‘The Natural History’, circa 77 A.D

The majority of Romans lived in crowded apartments, with walls thin enough to hear every noise. “Think of Ancient Rome as a giant campground,” writes Angela Alberto in A Day in the life of Ancient Rome.

...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HhwXipv3tRU

...

And, thanks to the Rome’s embrace of public sex, there was less of a motivation to make it taboo—especially considering the benefits.

Sex art, Pompeii

“Baths, drink and sex corrupt our bodies, but baths, drink and sex make life worth living” - graffiti — Roman bath

Early Middle Ages (4th century AD-1,200 AD): Privacy As Isolation

Early Christian saints pioneered the modern concept of privacy: seclusion. The Christian Bible popularized the idea that morality was not just the outcome of an evil deed, but the intent to cause harm; this novel coupling of intent and morality led the most devout followers (monks) to remove themselves from society and focus obsessively on battling their inner demons free from the distractions of civilization.

“Just as fish die if they stay too long out of water, so the monks who loiter outside their cells or pass their time with men of the world lose the intensity of inner peace. So like a fish going towards the sea, we must hurry to reach our cell, for fear that if we delay outside we will lost our interior watchfulness” - St Antony of Egypt

It is rumored that on the island monastery of Nitria, a monk died and was found 4 days later. Monks meditated in isolation in stone cubicles, known as “Beehive” huts.

Even before the collapse of ancient Rome in 4th century A.D., humanity was mostly a rural species

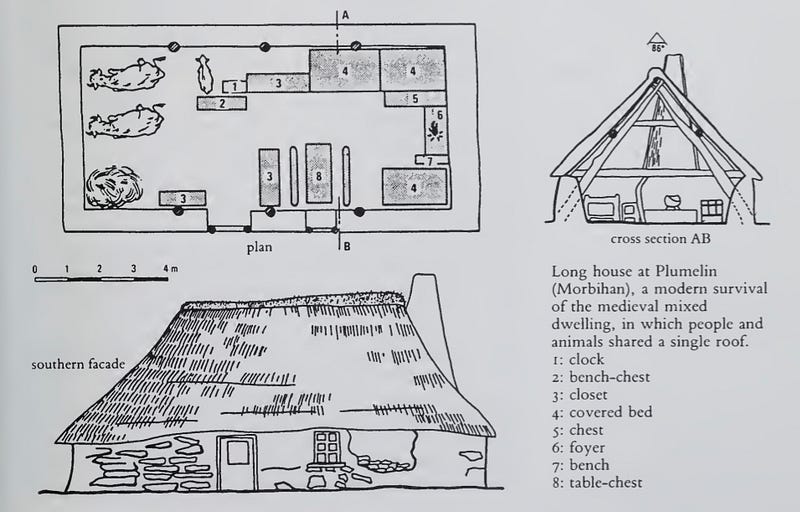

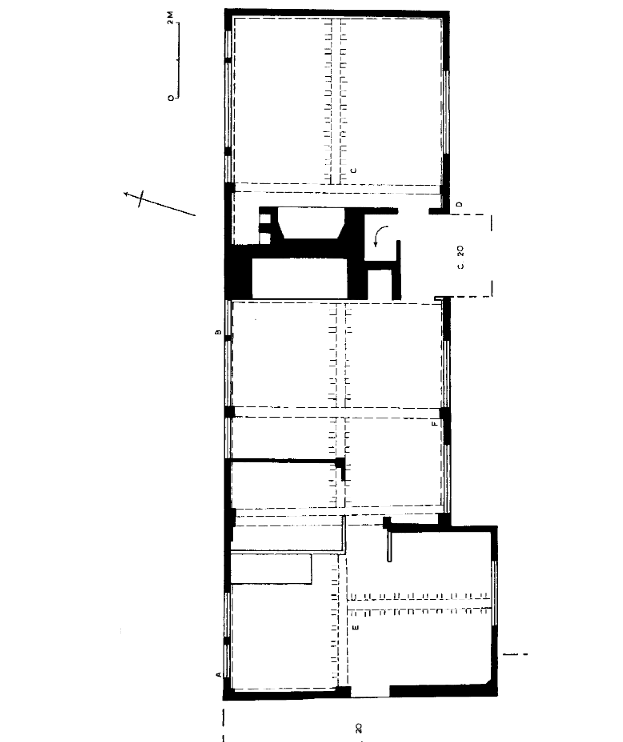

A stylized blueprint of the Lord Of The Rings-looking shire longhouses, which were popular for 1000 years, shows animals and humans sleeping under the same room—because, there was only one room.

Photo credit: Georges Duby, A History Of Private Life: Revelations of the Medieval World

“There was no classical or medieval latin word equivalent to ‘privacy’. privatio meant ‘a taking away’” - Georges Duby, author, ‘A History Of Private Life: Revelations of the Medieval World’

Late Medieval/Early Renaissance (1300–1600) — The Foundation Of Privacy Is Built

“Privacy — the ultimate achievement of the renaissance” - Historian Peter Smith

In 1215, the influential Fourth Council Of Lateran (the “Great Council”) declared that confessions should be mandatory for the masses. This mighty stroke of Catholic power instantly extended the concept of internal morality to much of Europe.

“The apparatus of moral governance was shifted inward, to a private space that no longer had anything to do with the community,” explained religious author, Peter Loy. Solitude had a powerful ally.

...

Fortunately for the church, some new technology would make quiet contemplation much less expensive: Guttenberg’s printing press.

Thanks to the printing presses invention after the Great Counsel’s decree, personal reading supercharged European individualism. Poets, artists, and theologians were encouraged in their pursuits of “abandoning the world in order to turn one’s heart with greater intensity toward God,” so recommended the influential canon of The Brethren of the Common Life.

To be sure, up until the 18th century, public readings were still commonplace, a tradition that extended until universal book ownership. Quiet study was an elite luxury for many centuries.

Citizens enjoy a public reading.

...

The Architecture of privacy

Individual beds are a modern invention. As one of the most expensive items in the home, a single large bed became a place for social gatherings, where guests were invited to sleep with the entire family and some servants.

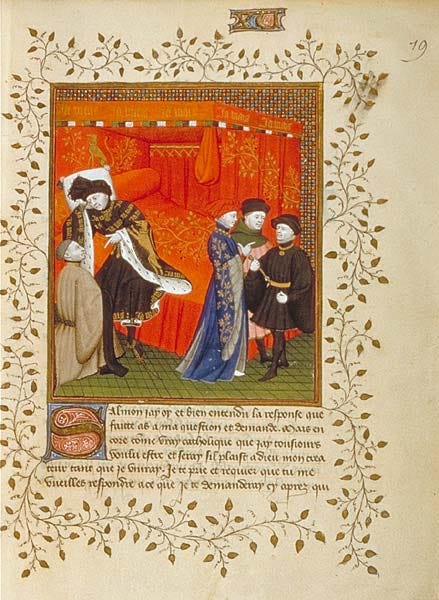

People gather around a large bed.

...

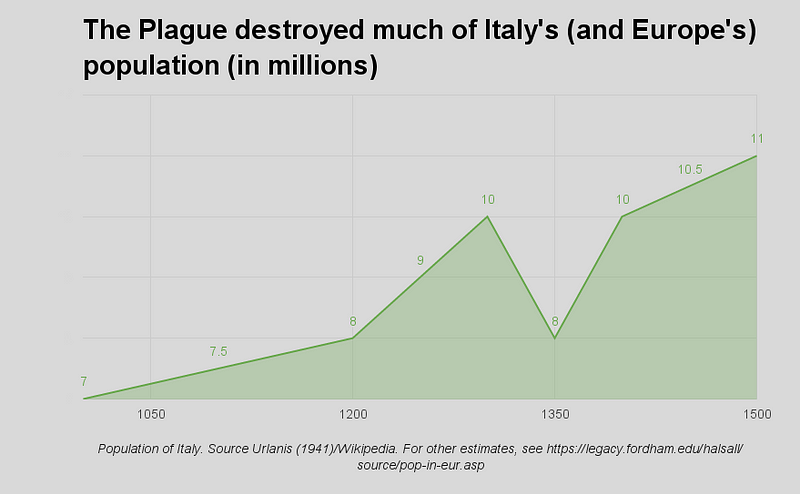

But, the uncleanness of urbanized life quickly caught up with the Europeans, when infectious diseases wiped out large swaths of newly crowded cities. The Black Death, alone, killed over 100 million people.

This profoundly changed hygiene attitudes, especially in hospitals, where it was once common for patients to sleep as close together as houseguests were accustomed to.

"Little children, both girls and boys, together in dangerous beds, upon which other patients died of contagious diseases, because there is no order and no private bed for the children, [who must] sleep six, eight, nine, ten, and twelve to a bed, at both head and foot" - notes of a nurse (circa 1500), lamenting the lack of modern medical procedures.

Though, just because individual beds in hospitals were coming into vogue, it did not mean that sex was any more private. Witnessing the consummation of marriage was common for both spiritual and logistical reasons:

“Newlyweds climbed into bed before the eyes of family and friends and the next day exhibit the sheets as proof that the marriage had been consummated” - Georges Duby, Editor, "A History of Private Life"

...

Few people demanded privacy while they slept because even separate beds wouldn’t have afforded them the luxury. Most homes only had one room. Architectural historians trace the origins of internal walls to the more basic human desire to be warm.

Below, in the video, is a Hollywood re-enactment of couples sleeping around the burning embers of a central fire pit, from the film, Beowulf. It’s a solid illustration of the grand hall open architecture that was pervasive before the popularization of internal walls circa 1,400 A.D.

...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UT4gELLPPzs > Couples sleep around the warmth of a fire (clip from Beowulf)

...

“Firstly, I propose that there be a room common to all in the middle, and at its centre there shall be a fire, so that many more people can get round it and everyone can see the others faces when engaging in their amusements and storytelling” - 15th century Italian Architect, Sebastian Serlio.

...

To disperse heat more efficiently without choking houseguests to death, fire-resistant chimney-like structures were built around central fire pits to reroute smoke outside. Below is an image of a “transitional” house during the 16th century period when back-to-back fireplaces broke up the traditional open hall architecture.

Source: Housing Culture: Traditional Architecture In An English Landscape (p. 78).

“A profound change in the very blueprint of the living space” - historian Sarti Raffaella, on the introduction of the chimney.

Pre-industrial revolution (1600–1840) — The home becomes private, which isn’t very private

The first recorded daily diary was composed by Lady Margaret Hoby, who lived just passed the 16th century. On February 4th, 1600, she writes that she retired “to my Closit, wher I praid and Writt some thinge for mine owne priuat Conscience’s”.

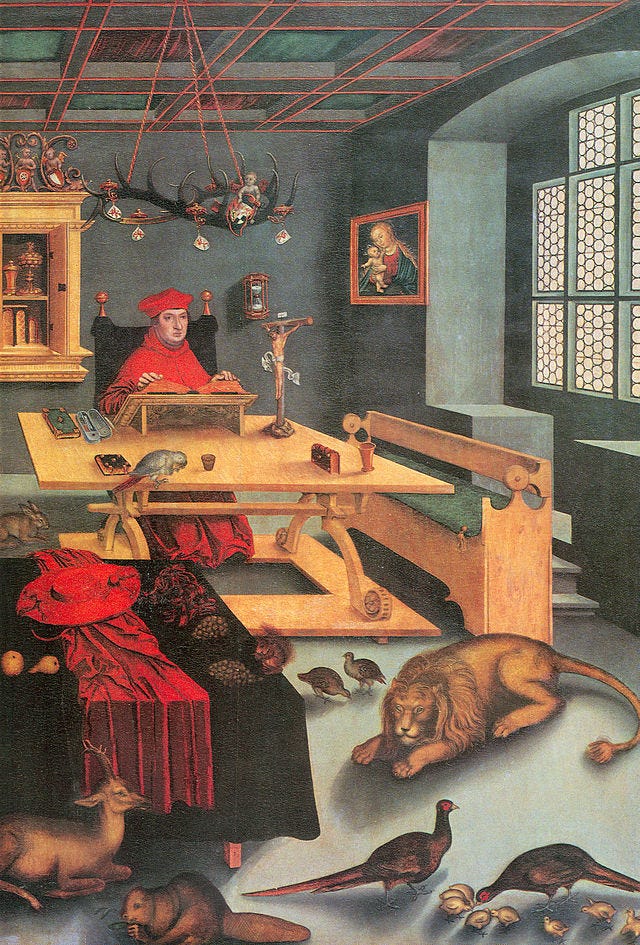

Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg in his study

By the renaissance, it was quite common for at least the wealthy to shelter themselves away in the home. Yet, even for those who could afford separate spaces, it was more logistically convenient to live in close quarters with servants and family.

“Having served in the capacity of manservant to his Excellency Marquis Francesco Albergati for the period of about eleven years, that I can say and give account that on three or four occasions I saw the said marquis getting out of bed with a perfect erection of the male organ” - 1751, Servant of Albergati Capacelli, testifying in court that his master did not suffer from incontinence, thus rebutting his wife’s legal suit for annulment.

...

Law

...

It was just prior to the industrial revolution that citizens, for the first time, demanded that the law begin to keep pace with the evolving need for secret activities.

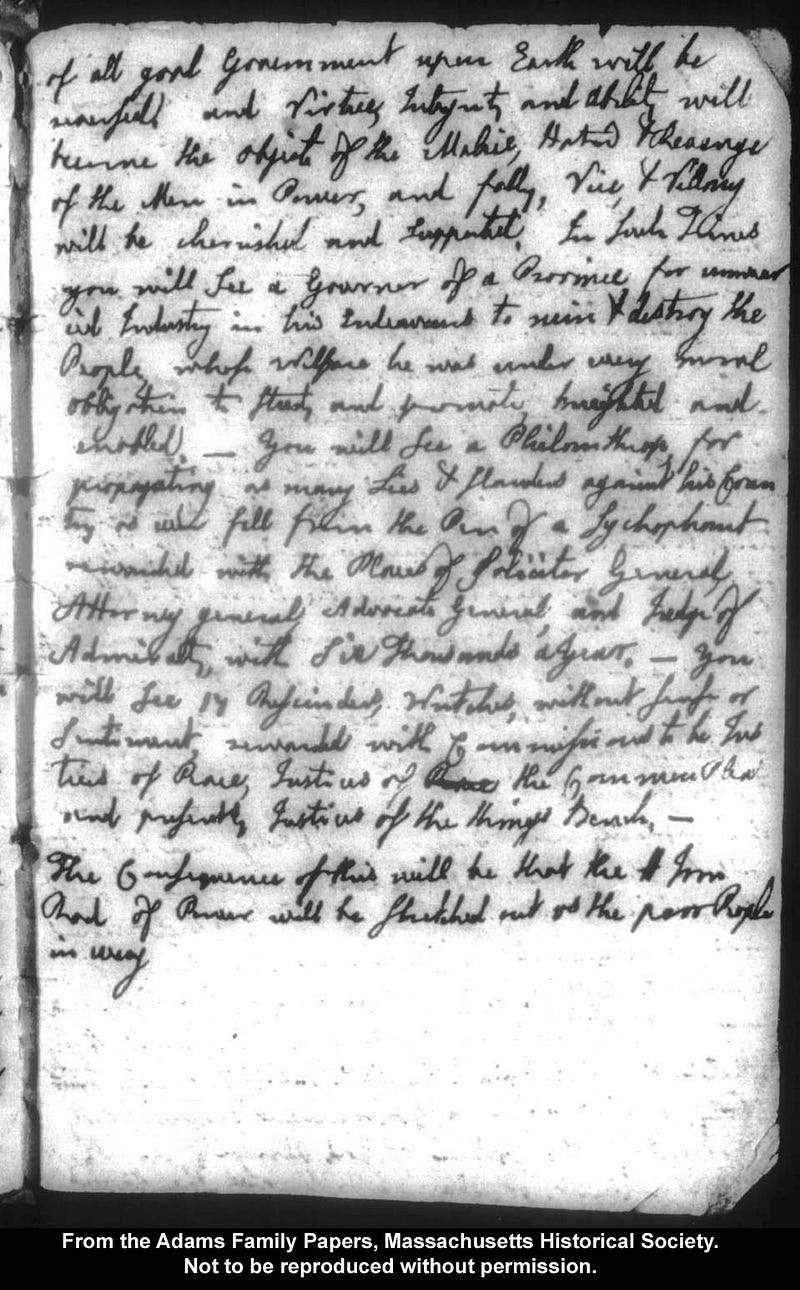

In this early handwritten note on August 20th, 1770, revolutionist and future President of the United States, John Adams, voiced his support for the concept of privacy.

“I am under no moral or other Obligation…to publish to the World how much my Expences or my Incomes amount to yearly.”

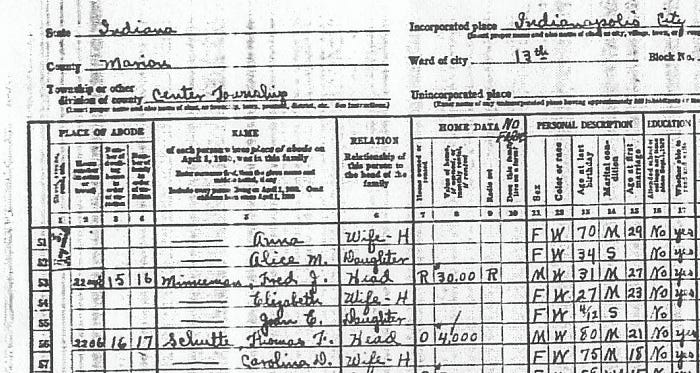

Despite some high-profile opposition, the first American Census was posted publicly, for logistics reasons, more than anything else. Transparency was the best way to ensure every citizen could inspect it for accuracy.

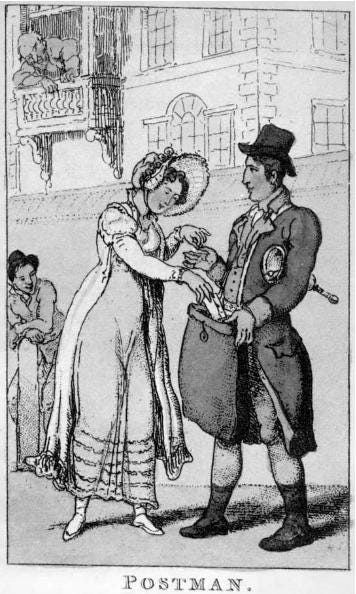

Privacy-conscious citizen did find more traction with what would become perhaps America’s first privacy law, the 1710 Post Office Act, which banned sorting through the mail by postal employees.

“I’ll say no more on this head, but When I have the Pleasure to See you again, shall Inform you of many Things too tedious for a Letter and which perhaps may fall into Ill hands, for I know there are many at Boston who dont Scruple to Open any Persons letters, but they are well known here.” - Dr. Oliver Noyes, lamenting the well-known fact that mail was often read.

This fact did not stop the mail’s popularity

Gilded Age: 1840–1950 — Privacy Becomes The Expectation

“Privacy is a distinctly modern product” - E.L. Godkin, 1890

“In The Mirror, 1890” by Auguste Toulmouche

By the time the industrial revolution began serving up material wealth to the masses, officials began recognizing privacy as the default setting of human life.

Source: Wikipedia user MattWade

“The material and moral well-being of workers depend, the health of the public, and the security of society depend on each family’s living in a separate, healthy, and convenient home, which it may purchase” - speaker at 1876 international hygiene congress in Brussels.

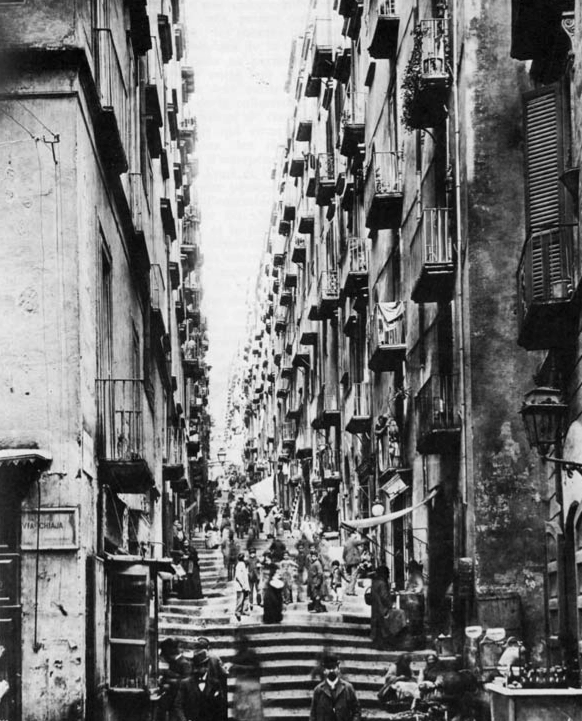

For the poor, however, life was still very much on display. The famous 20th-century existentialist philosopher Jean Paul-Satre observed the poor streets of Naples:

Crowded apartment dwellers spill on to the streets

“The ground floor of every building contains a host of tiny rooms that open directly onto the street and each of these tiny rooms contains a family…they drag tables and chairs out into the street or leave them on the threshold, half outside, half inside…outside is organically linked to inside…yesterday i saw a mother and a father dining outdoors, while their baby slept in a crib next to the parents’ bed and an older daughter did her homework at another table by the light of a kerosene lantern…if a woman falls ill and stays in bed all day, it’s open knowledge and everyone can see her.”

Insides of houses were no less cramped:

...

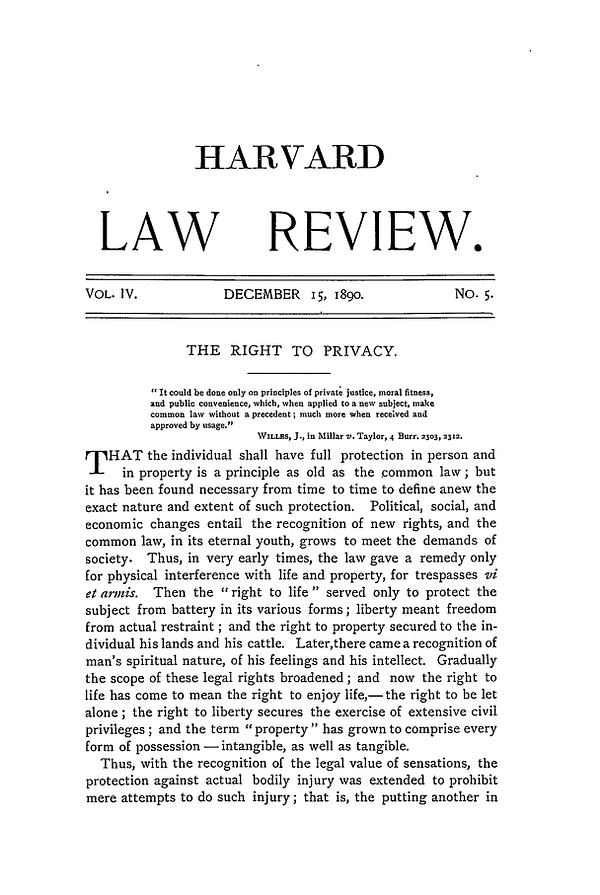

The “Right To Privacy “ is born

...

“The intensity and complexity of life, attendant upon advancing civilization, have rendered necessary some retreat from the world, and man, under the refining influence of culture, has become more sensitive to publicity, so that solitude and privacy have become more essential to the individual; but modern enterprise and invention have, through invasions upon his privacy, subjected him to mental pain and distress, far greater than could be inflicted by mere bodily injury.” - “The Right To Privacy” ~ December 15, 1890, Harvard Law Review.

Interestingly enough, the right to privacy was justified on the very grounds for which it is now so popular: technology’s encroachment on personal information.

However, the father of the right to privacy and future Supreme Court Justice, Louis Brandeis, was ahead of his time. His seminal article did not get much press—and the press it did get wasn’t all that glowing.

"The feelings of these thin-skinned Americans are doubtless at the bottom of an article in the December number of the Harvard Law Review, in which two members of the Boston bar have recorded the results of certain researches into the question whether Americans do not possess a common-law right of privacy which can be successfully defended in the courts." - Galveston Daily News on ‘The Right To Privacy’

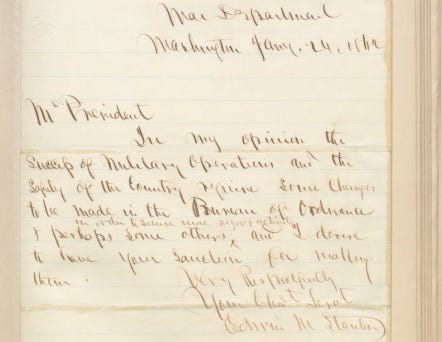

Privacy had not helped America up to this point in history. Brazen invasions into the public’s personal communications had been instrumental in winning the Civil War.

A request for wiretapping.

This is a letter from the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, requesting broad authority over telegraph lines; Lincoln simply scribbled on the back “The Secretary of War has my authority to exercise his discretion in the matter within mentioned. A. LINCOLN.”

It wasn’t until the industry provoked the ire of a different president that information privacy was codified into law. President Grover Cleveland had a wife who was easy on the eyes. And, easy access to her face made it ideal for commercial purposes.

The rampant use of President Grover Cleveland’s wife, Frances, on product advertisements, eventually led to the one of the nation’s first privacy laws. The New York legislature made it a penalty to use someone’s unauthorized likeness for commercial purposes in 1903, for a fine of up to $1,000.

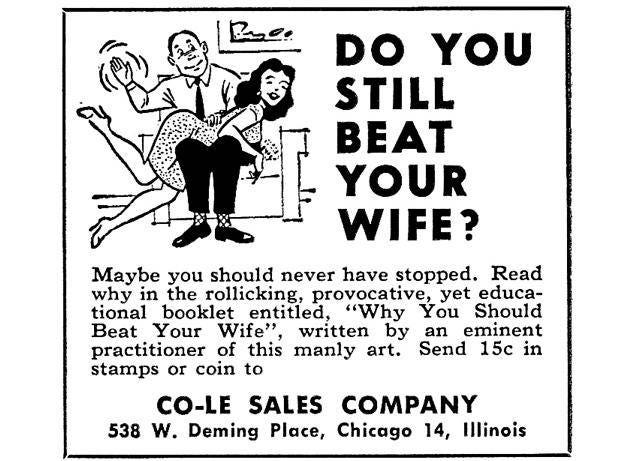

Indeed, for most of the 19th century, privacy was practically upheld as a way of maintaining a man’s ownership over his wife’s public and private life — including physical abuse.

“We will not inflict upon society the greater evil of raising the curtain upon domestic privacy, to punish the lesser evil of trifling violence”- 1868, State V. Rhodes, wherein the court decided the social costs of invading privacy was not greater than that of wife beating.

...

The Technology of Individualism

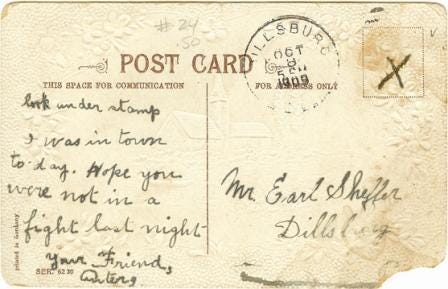

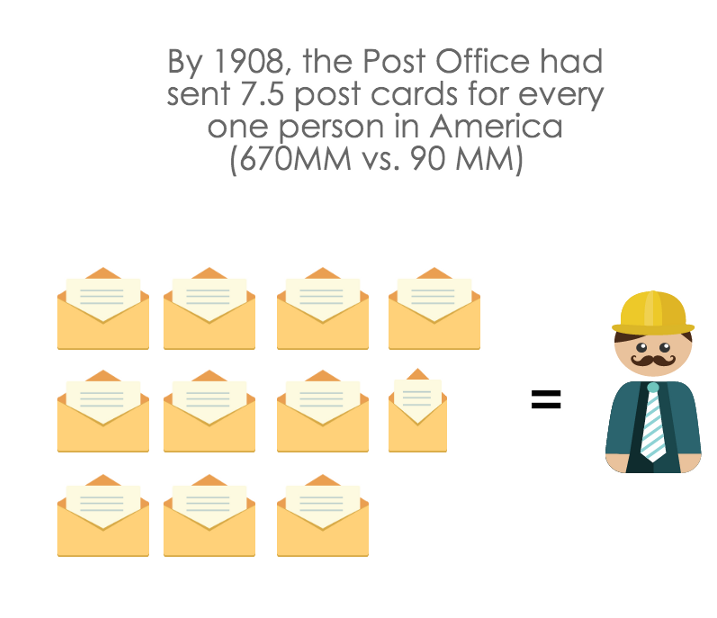

The first 150 years of American life saw an explosion of information technology, from the postcard to the telephone. As each new communication method gave a chance to peek at the private lives of strangers and neighbors, Americans often (reluctantly) chose whichever technology was either cheaper or more convenient.

Privacy was a secondary concern.

"There is a lady who conducts her entire correspondence through this channel. She reveals secrets supposed to be the most pro- found, relates misdemeanors and indiscretions with a reckless disregard of the consequences. Her confidence is unbounded in the integrity of postmen and bell-boys, while the latter may be seen any morning, sitting on the doorsteps of apartment houses, making merry over the post-card correspondence.” - Editor, the Atlantic Monthly, on Americas of love of postcards, 1905.

Even though postcards were far less private, they were convenient. More than 200,000 postcards were ordered in the first two hours they were offered in New York City, on May 15, 1873.

Source: American Privacy: The 400-year History of Our Most Contested Right

...

The next big advance in information technology, the telephone, was a wild success in the early 20th century. However, individual telephone lines were prohibitively expensive; instead, neighbors shared one line, known as “party lines.” Commercial ads urged neighbors to use the shared technology with “courtesy”.

But, as this comic shows, it was common to eavesdrop.

“Party lines could destroy relationships…if you were dating someone on the party line and got a call from another girl, well, the jig was up. Five minutes after you hung up, everybody in the neighborhood — including your girlfriend — knew about the call. In fact, there were times when the girlfriend butted in and chewed both the caller and the callee out. Watch what you say.” - Author, Donnie Johnson.

...

Where convenience and privacy found a happy co-existence, individualized gadgets flourished. Listening was not always an individual act. The sheer fact that audio was a form of broadcast made listening to conversations and music a social activity.

This all changed with the invention of the headphone.

“The triumph of headphones is that they create, in a public space, an oasis of privacy”- The Atlantic’s libertarian columnist, Derek Thompson.

Late 20th Century — Fear of a World Without Privacy

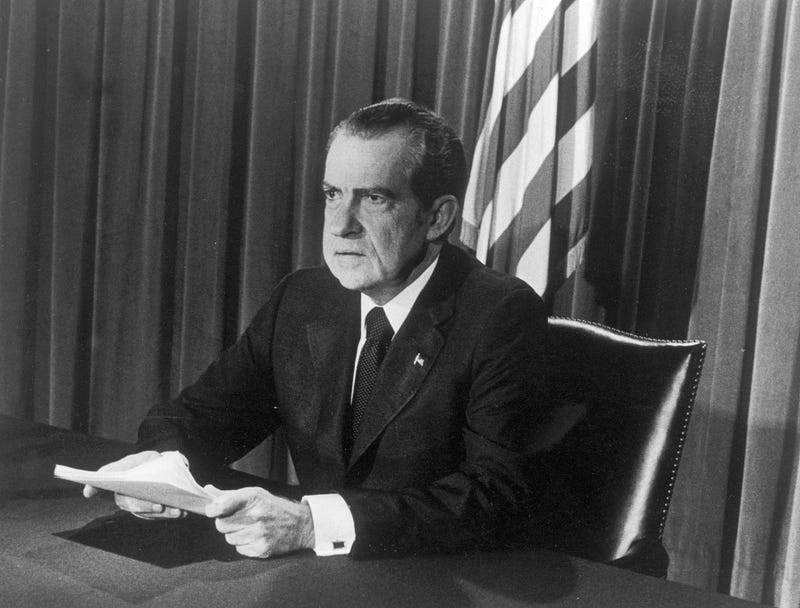

By the 60's, individualized phones, rooms, and homes became the norm. 100 years earlier, when Lincoln tapped all telegraph lines, few raised any questions. In the new century, invasive surveillance would bring down Lincoln’s distant successor, even though his spying was far less pervasive.

Upon entering office, the former Vice-President assured the American people that their privacy was safe.

“As Vice President, I addressed myself to the individual rights of Americans in the area of privacy…There will be no illegal tappings, eavesdropping, bugging, or break-ins in my administration. There will be hot pursuit of tough laws to prevent illegal invasions of privacy in both government and private activities.” - Gerald Ford.

Justice Brandeis had finally won

2,000 A.D. and beyond — a grand reversal

In the early 2,000s, young consumers were willing to purchase a location tracking feature that was once the stuff of 1984 nightmares.

“The magic age is people born after 1981…That’s the cut-off for us where we see a big change in privacy settings and user acceptance.” - Loopt Co-Founder Sam Altman, who pioneered paid geo-location features.

...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ew94okDkCwU

...

The older generations’ fear of transparency became a subject of mockery.

“My grandma always reminds me to turn my GPS off a few blocks before I get home “so that the man giving me directions doesn’t know where I live.” - a letter to the editor of College Humor’s “Parents Just Don’t Understand” series.

...

Increased urban density and skyrocketing rents in the major cities has put pressure on communal living.

A co-living space in San Francisco / Source: Sarah Buhr, TechCrunch

“We’re seeing a shift in consciousness from hyper-individualistic to more cooperative spaces…We have a vision to raise our families together.” - Jordan Aleja Grader, San Francisco resident

At the more extreme ends, a new crop of so-called “life bloggers” publicize intimate details about their days:

Blogger Robert Scoble takes A picture with Google Glass in the shower

At the edges of transparency and pornography, anonymous exhibitionism finds a home on the web, at the wildly popular content aggregator, Reddit, in the aptly titled community “Gone Wild”.

SECTION II:

How privacy will again fade away

For 3,000 years, most people have been perfectly willing to trade privacy for convenience, wealth or fame. It appears this is still true today.

AT&T recently rolled out a discounted broadband internet service, where customers could pay a mere $30 more a month to not have their browsing behavior tracked online for ad targeting.

“Since we began offering the service more than a year ago the vast majority have elected to opt-in to the ad-supported model.” - AT&T spokeswoman Gretchen Schultz (personal communication)

Performance artist Risa Puno managed to get almost half the attendees at an Brooklyn arts festival to trade their private data (image, fingerprints, or social security number) for a delicious cinnamon cookie. Some even proudly tweeted it out.

...

twitter.com/kskobac/status/515956363793821696/photo/1 > "Traded all my personal data for a social media cookie at #PleaseEnableCookies by @risapuno #DAF14" @kskobac

...

Tourists on Hollywood Blvd willing gave away their passwords to on live TV for a split-second of TV fame on Jimmy Kimmel Live. > https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=opRMrEfAIiI

Even for holdouts, the costs of privacy may be too great to bear. With the advance of cutting-edge health technologies, withholding sensitive data may mean a painful, early death.

For instance, researchers have already discovered that if patients of the deadly Vioxx drug had shared their health information publicly, statisticians could have detected the side effects earlier enough to save 25,000 lives.

As a result, Google’s Larry Page has embarked on a project to get more users to share their private health information with the academic research community. While Page told a crowd at the TED conference in 2013 that he believe such information can remain anonymous, statisticians are doubtful.

"We have been pretending that by removing enough information from databases that we can make people anonymous. We have been promising privacy, and this paper demonstrates that for a certain percent of a population, those promises are empty”- John Wilbanks of Sage Bionetworks, on a new academic paper that identified anonymous donors to a genetics database, based on public information

Speaking as a statistician, it is quite easy to identify people in anonymous datasets. There are only so many 5'4" jews living in San Francisco with chronic back pain. Every bit of information we reveal about ourselves will be one more disease that we can track, and another life saved.

If I want to know whether I will suffer a heart attack, I will have to release my data for public research. In the end, privacy will be an early death sentence.

Already, health insurers are beginning to offer discounts for people who wear health trackers and let others analyze their personal movements. Many, if not most, consumers in the next generation will choose cash and a longer life in exchange for publicizing their most intimate details.

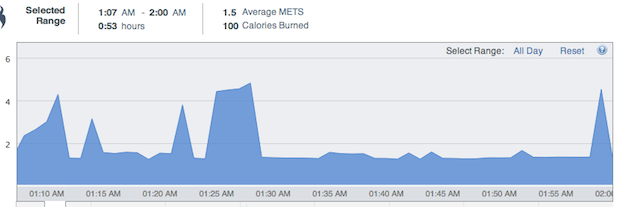

What can we tell with basic health information, such as calories burned throughout the day? Pretty much everything.

With a rudimentary step and calorie counter, I was able to distinguish whether I was having sex or at the gym, since the minute-by-minute calorie burn profile of sex is quite distinct (the image below from my health tracker shows lots of energy expended at the beginning and end, with few steps taken. Few activities besides sex have this distinct shape)

My late-night horizontal romp, as measured by calories burned per minute

...

More advanced health monitors used by insurers are coming, like embedded sensors in skin and clothes that detect stress and concentration. The markers of an early heart attack or dementia will be the same that correspond to an argument with a spouse or if an employee is dozing off at work.

No behavior will escape categorization—which will give us unprecedented superpowers to extend healthy life. Opting out of this tracking—if it is even possible—will mean an early death and extremely pricey health insurance for many.

If history is a guide, the costs and convenience of radical transparency will once again take us back to our roots as a species that could not even conceive of a world with privacy.

It’s hard to know whether complete and utter transparency will realize a techno-utopia of a more honest and innovative future. But, given that privacy has only existed for a sliver of human history, it’s disappearance is unlikely to doom mankind. Indeed, transparency is humanity’s natural state.

Tuesday, September 11. 2012

Essay: 21st Century Gestures Clip Art Collection

Via City of Sound

-----

By Dan Hill

A month or so ago, Nicolas Nova asked me to write an essay for a project he was doing. He said they'd been working on a catalogue of novel "gestures, postures and digital rituals" and could I write about that, please, as a kind of foreword.

"Curious Rituals is a research project conducted at Art Center College of Design (Pasadena) in July-August 2012 by Nicolas Nova (The Near Future Laboratory / HEAD-Genève), Katherine Miyake, Nancy Kwon and Walton Chiu from the media design program. (It) is about gestures, postures and digital rituals that typically emerged with the use of digital technologies..."

It so happens that, for some years now, I'd been collating a catalogue of novel gestures and interactions myself and had never got round to doing anything with it. So Nicolas's kind request gave me the chance to get it off my computer and onto the internet. Thanks Nicolas!

One outcome of their project is a rather nice short film; another is their book, here. My "preface" is reproduced below. Please note: as you'll see, this is not intended to be thorough, complete or even coherent—but you'll get the gist. I would guess many of us have such a list. It's probably more about noticing as a kind of practice rather than the particular gestures themselves, even though I spent a little too much time trying to get the hands right.

21st Century Gestures Clip Art Collection

1. A text file

For some years I’ve been collating a list in a text file, which has the banal filename “21st_century_gestures.txt”. These are a set of gestures, spatial patterns and physical, often bodily, interactions that seemed to me to be entirely novel. They all concern our interactions with The Network, and reflect how a particular Networked development, and its affordances, actually results in intriguing physical interactions. The intriguing aspect is that most of the gestures and movements here are undesigned, inadvertent, unintended, the accidental offcuts of design processes and technological development that are either forced upon the body, or adopted by bodies.

For a while, I have been “a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking”, simply compiling the list. As a list, it’s entirely subjective, incomplete, and essentially pointless. But I kept coming back to it. Some gestures, interactions or behaviours eventually disappeared from the text file; others were reinforced.

It turned out that Nicolas Nova and collaborators were pursuing a similar idea and asked, by chance, if I might write something about their project.

Rewriting the brief somewhat, I have instead used this essay to put my list to bed.

Walking around “eating the world with your eyes”, as the fictional design tutor in Chip Kidd’s novel The Cheese Monkeys puts it, you can’t help but observe the influence of The Network on our world. Yet The Network is often still spoken about as if it were somehow something separate to Us, as if it were an ethereal plane hovering above us, or perhaps something we might be increasingly immersed in but still separate to our bodies, to our selves. This doesn’t feel accurate now. There is no separate world, and this list indicates how we are even changing what our bodies do in entirely emergent, or at least unplanned, everyday fashion, in response to The Network’s demands.

Yet this isn’t a list of weak signals or extreme and extremely unnecessary positions—such as embedding an RFID chip in your arm, Kevin Warwick—but entirely vernacular conditions, performed by everyday people and created by everyday people.

Working on various projects for the State Library of Queensland in Brisbane, I had begun to informally assess how wifi users were inhabiting the space, not simply in terms of the locations they would flock to, or their patterns of social grouping, but how they draped themselves over furniture in new ways, found small pockets of space to hole up in, while cradling or propping up a laptop, or the newer netbooks that had emerged at that point. There were no iPads back then, but there was clearly a new physical relationship around computing that suddenly left the Library looking askance at its “computer labs” and “drop-in-centres” of “PC towers” secreted under rows of desks.

I drew sketches of the library users co-opting the spaces and objects, ascribing a name to each type as if they were yoga positions. Two laptop users sitting with their backs to each other was “Reverse Battleships”; two sitting facing each other was “Battleships”; one, watching a DVD whilst lying flat on her stomach, was “Front Crawl”; another, astride a bench, perpendicular to the designed stance, was “The Horse”, while swinging one’s legs over one side of the bench but twisting the torso to remain perpendicular would be “Side Saddle”, and so on. I also plotted where people were sitting in relation to wifi signals and building architecture, and discovered clear correlations between people, space, devices and Network.

I made a rough 3D model of the wifi itself, as if it were a physical phenomenon that we could more easily understand structurally, rather than simply connect to. (AHO’s “Immaterials: Light Painting WiFi” later articulated a similar idea in a far more sophisticated fashion.) These were all attempts to understand how The Network could be perceived in civic space. Yet in the yoga position sketches, I was also interested in how people’s movements changed.

The few examples collated here are a development of those sketches, and range from small gestures, to those involving the whole body, to those concerning bodies moving through spaces. Each example has a name and a sketch (below). The list in my text file has more examples than are listed here, but these should be enough to convey the idea. It’s interesting to compare with the much larger list independently collected by Nova and his colleagues. We are looking at the same thing, yet at different things also. What follows is not really a complete list or clip art collection at all—more a sketch of what one might be, in order to provoke more interesting questions.

Size S

In terms of small gestures, one which already seems to be dying out is the Google Map Smear.

Fig. 1 The Google Map Smear

In which a user momentarily activates international roaming data and caches adjacent map tiles by smearing the index finger around the user’s intended destination.

This you see when people are suffering from “roaming data” allowances condition on their smartphone’s payment plan, and so are anxious about expensive data transfer. When in a foreign place, the user will temporarily turn data roaming on and load up the cache in their phone’s memory by scooping up the immediately adjacent map tiles, downloading enough map to show them the way, and then quickly turn off the data. This scooping is performed in a series of “smearing” circular movements, as if scrubbing the map tiles into life, rubbing a magic lamp to conjure up some locally useful geography. It’s unlikely this tiny interaction will persist, as maps cease to be produced via tiling, and roaming data becomes less expensive.

Fig. 2 The Wake-Up Waggle

In which a user must approach a sleeping PC in both an absent-minded and mildly aggressive fashion, and drum on the keyboard whilst rattling the mouse.

The Wake-Up Waggle, in which a user approaches a sleeping computer and attempts to rattle it into life by hammering the keyboard or aggressively waggling the mouse is at first so small as to be insignificant, but what kind of previous object would we interact with in this way? Perhaps kicking a lawnmower into life, or nudging a sleeping dog with your foot, but it feels disturbingly tied to the way we feel about computers; the mild frustration with which we often approach the device, as if it should by now be guessing when we’re about to use it. There’s a muted irritation here I find perversely appealing.

Note, I haven’t included the wipes, pinches, taps and double-taps common to gestures for touch screens. I’m not quite sure why. They are novel and inventive, clearly, but perhaps also deliberately familiar—they don’t feel odd at all, and instead mimic our previous interactions with sliders, paper or fabrics. They are also clearly designed.

Size M

In terms of bolder gestures and actions which require most of the body, we have the iPad Photographer, the Security Pass Hip Bump and the iPhone Compass Calibrator.

Fig. 3 The iPad Photographer

The iPad is held in both hands a little awkwardly and at arm’s length until the Camera app focuses on the intended subject, at which point a finger or thumb is bent onto the touch screen in order to attempt to hit the “shutter release” button.

The iPad Photographer is really a variant on existing ways of taking pictures, but feels awkward and transitional. While there needn’t be anything particularly odd about taking a picture with a largeish rectangular-shaped device, it does look and feel very peculiar indeed. The form factor of cameras has hovered around the hand for centuries, even when embedded in cellphones, yet this is a new body shape, requiring both hands holding the device at arm’s length while one thumb or finger gropes awkwardly for the in-software shutter button.

The Security Pass Hip Bump, which I first noticed a former client doing repeatedly in the library building she worked in, is particularly enjoyable. It occurs when someone carries their RFID-enabled security pass in their bag, and approaching a sensor, lifts the hip to angle the bag towards the sensor, creating a hands-free connection and activating the lock (the hands are often full of paper files, ironically enough.) It’s clearly an odd thing to do, when considered like this—to insouciantly cock your hips towards a small black rectangle on the wall as a form of greeting and personal identification—but it can be carried off with a certain panache. Try it.

Fig. 4 Security Pass Hip-Bump

In which a user opts to keep her RFID security pass in her bag and gains entrance to her office nonetheless, through lifting and angling the hip up towards the wall-mounted sensor, which unlocks the door upon successful “handshaking”.

When the same security passes are on extensible key fobs, they are articulated as if they were keys; when they are worn on lanyards, it’s as if they were simply identity cards from an earlier age, merely “shown” to a sensor rather than a security guard. Similarly, even something like retinal scans are a long-lost descendent of a family of gestures that might include the act of accessing a medieval walled city—put your face up to the grate for inspection—just as a spoken passphrase also has an ancient history. The Hip-Bump is different. It relies on a loose, instinctive, trial-and-errored understanding of the range of the radio waves involved, and the materials involved, and again feels like a form of interaction entirely unforeseen by the designers of security systems. (Note that Nova and team’s “Bag Swiping” is a close relation.)

Most famously, perhaps, is the iPhone Compass Calibrator, which perhaps shouldn’t be included as it clearly is designed. Yet the performance, often public, that it entails is appealing enough to warrant inclusion. To suddenly stand stock-still in the street and rotate the little rectangle through an arm’s length figure-8 feels almost like a physical incantation, the kind of activity that might lead you direct to the ducking stool were it 17th century Massachussets. One never stops to consider how it might calibrate the phone’s compass; we are simply following orders. What else would we do if Apple told us to? People have a frozen, absent, pretty vacant look on their face as their arm movements mechanically ape the figure-8 described on their iPhone—although some seem to realise the peculiarity of the gesture and offer up a wry smile. (You’ll sometimes also see iPhone users revolving in a circle as their compass finds its bearings, doing a little waggle-dance with the electronics.)

Fig. 5 The iPhone Compass Calibrator

Upon attempting to use Maps app, user is required to move the iPhone through a figure-8 pattern within a vertical plane in order to locate the compass.

Size L

Then there are the larger spatial conditions, in which a person interacts with others, and/or The Network, moving through a space.

Fig. 6 Cellphone Wake

In which user moves through busy street focusing solely on smartphone in hand, either reading or typing or both, such that the oncoming pedestrians are forced to grudgingly flow either side.

Cellphone Wake is probably not that novel. Walking down a city street reading a book or newspaper would have had the same effect on a moving crowd a century earlier, but perhaps few would have done it. Now, it occurs frequently, and due to the deeper cognitive load involved in reading, typing and walking simultaneously, we might expect the ballet of the sidewalk to now rely on a heightened sense of “civic proprioception”, an awareness of one’s body in a bounded space of constantly moving objects, constantly yet subconsciously scanning for collision detection. The agent-based pedestrian simulations used to model subways and streets on urban planning projects are only just beginning to incorporate a sense of these interlocking wakes.

While Cellphone Wake is irritating to observe, never mind get caught up in, when a Meeting Room Wake-Up Call occurs, it’s a delicious sight to behold. One of my perennial concerns is in designing systems that enable active citizens. Many technology-led “smart building” visions actually tend towards creating passive citizens, who outsource decision-making about their environment to software, with simple data derived from simple sensors. In this way, passive citizens also abdicate their conscious participation within an environmental system. Passivity of this type cannot create a “smart building” almost by definition, nor will it reverse the irresponsible decision-making culture that created unsustainable automated buildings and spaces in the first place.

Fig. 7 Meeting Room Wake-Up Call

. During business meetings, preferably serious ones, a moment’s stillness in the room can trigger over-active motion sensor meaning room is plunged into dark- ness. Meeting participants must re-activate motion sensor through sudden and impromptu performance of manic arm-waving.

So there’s a secret delight in seeing people interact with technology like this, in seeing the sheer physicality of their interactions—seeing a Serious Meeting of Businesspeople suddenly waving their hands in the arm like they just don’t care, in order to wake up a trigger-happy motion sensor. While it’s not particularly to do with The Network, this performance, when thought of more broadly, effortlessly reveals the absurdity in much of the “smart building” idea. (For more such absurdity, see the related toilet-based “Waving at Sensors” tactic in the Curious Rituals list.)

Fig. 8 Wi-Fi Dowser

In order to achieve maximum throughput over a wifi network, user meanders around a space, holding tablet or laptop out in front of them, occasionally watching the signal strength indicator, until opti- mum compromise of signal and space is located.

I first consciously noticed W-ifi Dowsing during that post-occupancy evaluation of the public wifi at the State Library of Queensland. As one section of the library closed for the day, visitors would wander out with their laptops still open in front of them, staying connected and looking for the strongest wifi signal. Ultimately, users gathered near largely anonymous wireless access points; located through trial and error, and watching their devices, they manoeuvred themselves towards the best position in terms of The Network rather than the best physical space (or at least, some good compromise of both.) This seemed redolent of the ancient act of dowsing, or doodlebugging, for water, a form of divining trying to perceive and locate a hidden flow—although with rather better results than that entirely spurious practice. Neither public spaces or laptops are designed with this movement in mind.

2. Clip art sociology

I’ve drawn these activities in a kind of 1950s newspaper illustration style, often seen in classified ads at the time, and now used as clip art (they’re actually adapted from scanned originals found on Flickr.) Those ads, and indeed clip art, often work as some kind of subconscious “training” for modern life. They prime what typical behaviours, are, or should be, given clip art’s often aspirational primary uses.

Clip art such as this usually describes a form of physical interaction, in space, bereft of backstory. They are simply “man sitting at desk”, “woman, smiling, answer phone”, “people dancing”, “office party”, “shop interaction”. They describe context but not content, so that they might be freely used to underscore numerous different narratives. They are a frozen moment of interaction, with no before or after.

So perhaps we might read clip art as an unwitting description and guide to the stereotypical environments and interactions of our world.

This is why David Rees’s legendary comic strip “My New Filing Technique Is Unstoppable” is quite so funny; in its crude clip-art bastardisations, it highlights the mismatch between an age lived on The Network (us) and the office culture of the near past (them). It freeze-frames people (mis)filing paper into filing cabinets and playfully and profanely deadpans them into an absurd alternate universe, which tells us as much about contemporary corporate-speke and the thrill of The Network as it does about the ‘80s or early ‘90s office environments its characters seem to be drawn from.

I transcribed some of the emerging behaviours of our modern world into this language of clip art to similarly freeze, distill, highlight and to provoke a discussion as to whether they are simply peculiar blips or transitional hints as to where we’re going next, taking an everyday performance and stripping it of its context, pinning the butterfly under the glass.

The sports jackets can only help in this regard.

3. Could have been contenders

We can argue about these particular examples all day. Some entrants on the list get removed upon consideration. A man stooping and pointing his phone to capture a QR code at the bottom of some advertising hoarding, as I saw in the street in Helsinki the other day, is really only a variation on a photo-taking pose, simply held a little longer due to machine vision’s poor acuity.

Certainly, the act of taking photographs has changed shape due to digital technology. Where once the camera was generally brought up to the eye, now it is more often active at arm’s length, thanks to LCD screens on the back, and the “fire and forget” sensibility enabled by cheap storage, or increasingly a cloud-based upload meaning storage isn’t even an afterthought. (Those of a certain age will remember how precious each of your 24 or 36 shots on the roll of film used to be.) The freedom of movement these developments have delivered have been exploited by professional cinematographers and the average punter alike. But again, it is only a variation on a previous mode, and equally, many photographers will have shot at arm’s length for as long as cameras have been light enough to do so. There is nothing to do with The Network about this performance. (How might the physicality of taking a photograph change due to The Network is a good question, however.)

People certainly move in a distinctive fashion when they’re talking on the phone. I observed our two year-old daughter talking into her plastic Hello Kitty pretend-phone and airily meandering around the apartment, brushing her fingers absent-mindedly over surfaces, just as her mother does, as she talked to her mythical mystery companion. You might argue the Bluetooth headset or the iPhone’s earbud-based mic has freed up one hand, but the essential stance of Being On The Phone hasn’t changed as a result of The Network.

Even a intrinsically contemporary product like the Nike Fuelband is interacted with like a wristwatch, just as the laptop is essentially operated like a typewriter. Even what the body does in an achingly new game like “Tearaway” on the PS Vita, which features a riot of interaction design breakthroughs, would essentially be familiar to a 1950s child’s imagination—blowing on characters or tilting platforms to knock them over, or using fingers as puppets, for example. The novelty is in the fact that the characters are digital and Networked, rather than in the gestures themselves. It’s why these interactions work, and again, they’re entirely designed this way. All would be familiar, one way or another, to someone magically transported from 1965, say, even if the outcomes of those gestures would be largely beyond their comprehension.

4. Immaterial weightlifting

But the interactions in the text file should seem odd to the time traveller, just as they seem slightly odd to us when highlighted in this way.

These physical acts all make it evident that there is no separate “virtual world”; our very bodies are shaping our digital interactions. We are part of The Network, and not just intellectually, in terms of our projected persona and identity, but physically. The body is making The Network visible, legible. Tracing the articulation of the hips, hands and arms is sometimes tracing the seams of The Network.

We have a long understanding of how the body creatively interacts with invisible forces. If you watch footage of Jimi Hendrix, you can see how he used his body to shape his guitar’s feedback; the sound is produced by the interplay of his guitar, especially its pickup, the speakers, the room, and his body within electric fields, in space, over time. Sensors and actuators, in contemporary language, at play within invisible fields, but shaped by the body, as well as objects and spaces. We need to think in terms of these fluid immersive interactions, material and immaterial—or “transmaterial as Mitchell Whitelaw would say—which we are part of physically as well as intellectually. This implies the conceptual separations of Hardware and Software, Them and Us no longer stand.

Unlike the objects that are being interacted with—here deliberately represented as characterless rectangles—the bodies reveal the patterns of information exchange. Rather than passive users in meaningless space with screens bringing all the action from elsewhere, these interactions foreground the idea of “Screen as object in the world, rather than window to somewhere else“, as Mitchell Whitelaw puts it. “Window to somewhere else” has been around for a long time, yet as Whitelaw’s essay “After the screen” suggests, we are now working with “glowing rectangles” in a new way, and sometimes interacting with The Network via objects in the world that are without screens, rectangles without the glow.

The kinetic energy expended in the extravagant contortions of the Security Pass Hip Bump, or even the subtle twitches of the Map Smear, suggest the transactions at play rather more the objects themselves do. You can almost viscerally feel the tiles being created during the Map Smear.

As Bruce Sterling put it in “Shaping Things”, the objects are merely “material instantiations of an immaterial system”, and relatively faceless ones at that, whereas the immaterial system is the aspect which is “so overwhelmingly extensive and rich.” Perhaps it’s in the body that we sense that weight of information elsewhere?

In 1985 Italo Calvino wrote “It is true that software cannot exercise its powers of lightness except through the weight of hardware.” Time has passed, and the heaviness of hardware has dissolved into lightness, as a counterpoint to the increased weight of associated information on The Network. But the body has also become a weighty vessel for software, a site for the Network to express its dynamics, well before we explore the next wave of wearable computing.

5. YouTube: “early flying machines”

Speaking of lightness, when we look back at old movies of early flying machines, we see frail bodies trapped in awkward wooden frames, some of which hop unpredictably in and out of the air, as if a plastic bag blown along by the wind, while others plummet headlong from jetty to water with all the sense of purpose that gravity can muster. Those bruised and soggy aviators caught flapping articulated arms we can now discount as pursuing a developmental dead-end, though it was probably worth a try at the time. In others, we can see the blueprints of successful subsequent flights emerging before our eyes.

These contemporary actions are similarly unpredictable. We don’t know if the Security Pass Hip Bump is actually a precursor of what happens when our clothes are made of smart fabric derived from nanocellulose fibres, and we use the combination of body and fabric to receive, transmit and display data. Is it a form of prototype, or is it simply an absurd contortion inflicted upon us by a building contractor placing an sensor slightly too high?

They leave us to wonder whether we have designed “things which are in harmony with the human being and organically suited to the little man in the street”, as Alvar Aalto put it. Perhaps these all too human responses indicate we actually have designed in such harmony, totally inadvertently? Or that, just as the street finds its own use for things, our stereotypical physical movements simply adapt, if the promise of The Network is worth it.

6. Learning from wooden spoons

You might argue over these choices; that’s the point. Such behaviours come and go every day. The point is only to observe, perhaps. These are all transitional, and at this point they tell us about here and now. In other words: at this point, they tell us about this point.

But over time, when you watch enough, and log the iterations, they might hint at where we’re going, at our future physical interactions. Bruno Munari once wrote that the repeated use of a wooden spoon for stirring and testing soup not only wears the spoon down, but also “it eventually shows us what shape a spoon for stirring soup should be.”

We can’t easily see that creative wear and tear taking its effect upon The Network and our interactions with it. Unless we discuss it, we can’t recognise the shifts in physical and social interaction occurring as a result of something that is often invisible, or leaves little trace either way, and whose objects are discarded with a frequency that would make Munari wince, and the simple wooden spoon feel quietly triumphant.

What we’re witnessing here are tentative vernacular sketches as to how we might physically interact with The Network. Just as those early films of flying machines are equally absurd and prescient, these contortions and behaviours might contain the clues of our future interactions.

Building an unfinished catalogue of them, as I have here, is also absurd, clearly; I leave it to you to do the prescient bit.

---

Some references Alvar Aalto, speech in London, 1957.

Italo Calvino, "Six Memos for the Next Millennium", 1985

Chip Kidd, "The Cheese Monkeys", 2002

Bruno Munari, "Design as Art", 1966

David Rees, "My New Filing Technique Is Unstoppable"

2002 Bruce Sterling, "Shaping Things", 2005

Clip-art sketches inspired by the "Bart&Co. Historic Clip Art Collection"

Monday, January 31. 2011

Free Download: Impact of Light on Human Beiings

Via Luminapolis

-----

by wk

Scientists have been studying the biological impacts of light perceived by the human eye since as long ago as the 1980s. But it was not until 2002 that they discovered ganglion cells in the retina of mammals that are not used for “seeing”. The newly identified cells respond most sensitively to visible blue light and set the “master clock” that synchronises the system of internal clocks with the external cycle of day and night. This booklet provides a practical and user-oriented summary of what science knows today about the non-visual impact of light on human beings. It is not a final, authoritative work but an ambitious attempt to describe the nascent, fast-growing field of research examining light, health and efficiency. More>

Related Links:

Tuesday, January 05. 2010

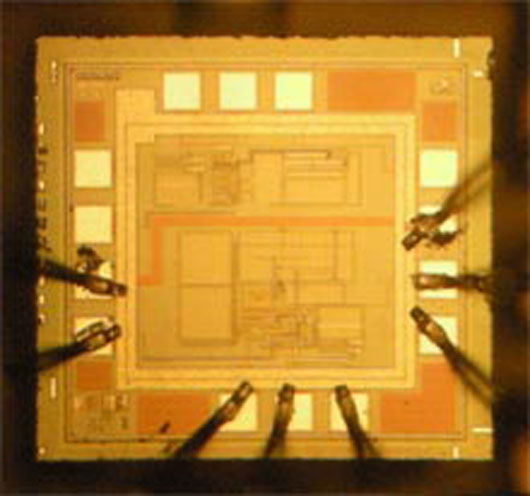

Battery-Free Implantable Neural Sensor

The shrinking size of electronics allows for the implantation of increasingly sophisticated electronic devices in the human body, paving the way for new prosthetics and brain-machine interfaces – think of the speculative phone tooth, conductive body paint or the brain-twitter interface. But so far a big challenge has been how to deliver power to electronic components embedded within the body.

While currently applied devices, such as cochlea or retinal implants, rely on inductive coupling, which means the power source needs to be centimeters away, engineers at Brown University have now developed an implantable neural sensing chip that is powered via a radio source that can be up to a meter away. The technology is similar to the equipment used to power and read information from radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags.

So far, the technology has only been tested to measure neural activity in moths, but of course “the real challenges and application potential emerge in work with primates.” says Arto Nurmikko, professor of engineering at Brown University. Another small step in the diminishing of the border between people and products.

Via Techreview. Image credit: Brian Otis. Related: Implantable Silk Electronics, phone tooth, Metalosis Maligna.

-----

Via NextNature

Wednesday, November 18. 2009

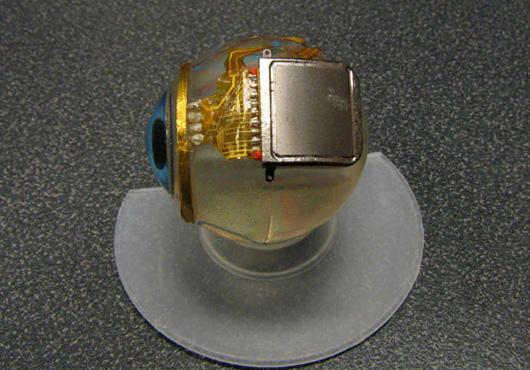

The Eye of a Cyber Sapien

An earlier post on this blog already displayed the possible future of sight using augmented contact lenses. Researchers at MIT take this second sight to a next level by creating a retinal implant that could help blind people regain much of their vision.

People receiving the implant would wear a pair of glasses with a built-in camera that wirelessly powers the implant and sends images to a micro-controller on the eye-ball. These are then processed and send to electrodes implanted below the retina.

Besides the immense value for blind people imagine the future possibilities for truly virtual and augmented reality. Always wanted infrared sight? Or would you prefer to hook it up to your Second Life account? You can also just watch a movie.

-----

Via Next Nature

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.

Quicksearch

Categories

Calendar

|

|

July '25 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||