Note: Yet another dive into history of computer programming and algorithms, used for visual outputs ...

Via The New York Times (on Medium)

-----

By Siobhan Roberts

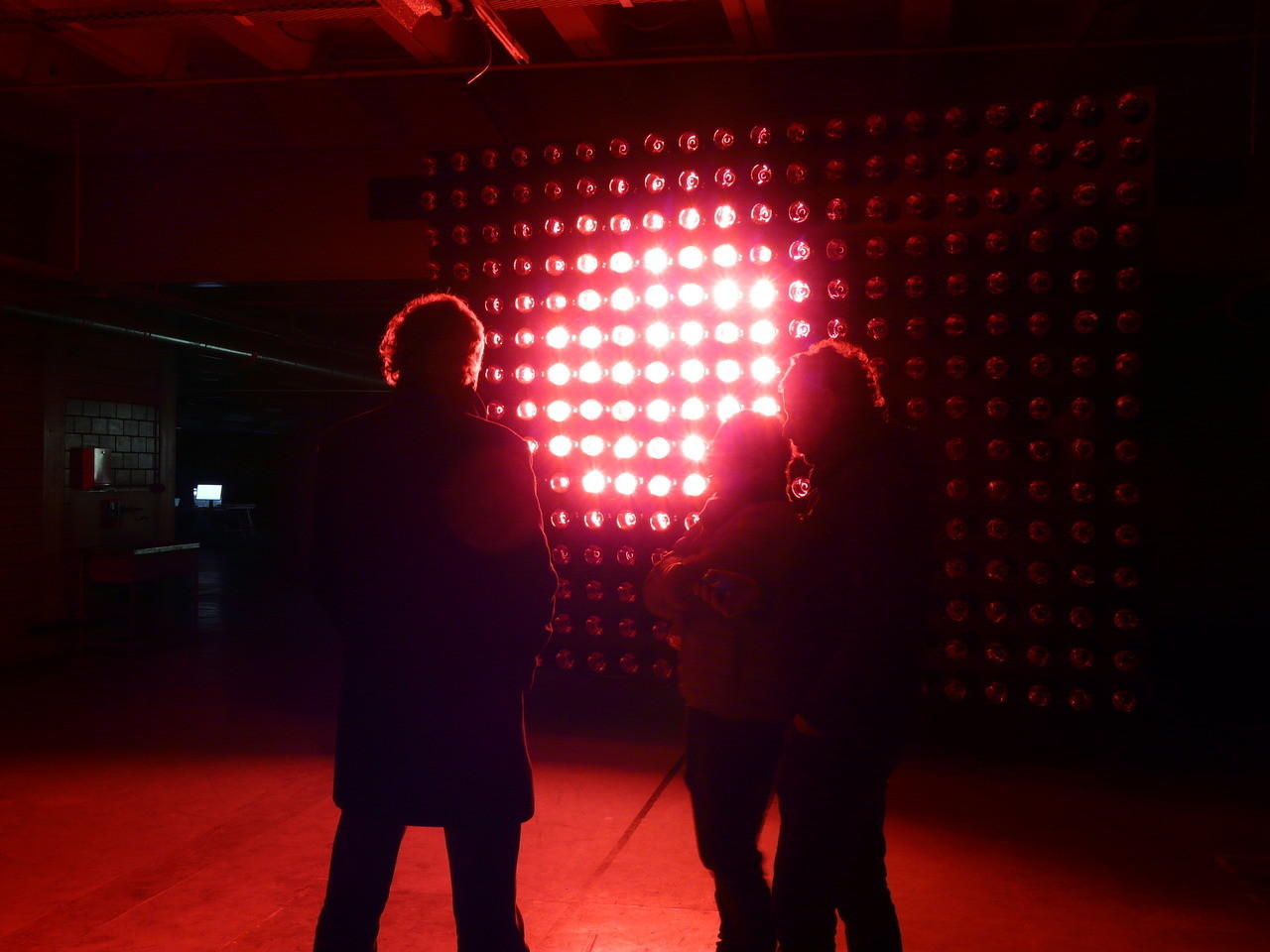

Donald Knuth at his home in Stanford, Calif. He is a notorious perfectionist and has offered to pay a reward to anyone who finds a mistake in any of his books. Photo: Brian Flaherty

For half a century, the Stanford computer scientist Donald Knuth, who bears a slight resemblance to Yoda — albeit standing 6-foot-4 and wearing glasses — has reigned as the spirit-guide of the algorithmic realm.

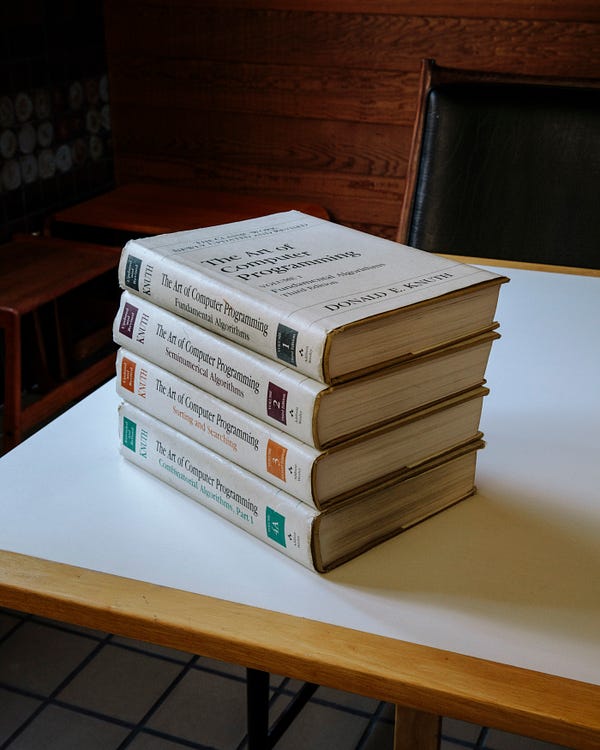

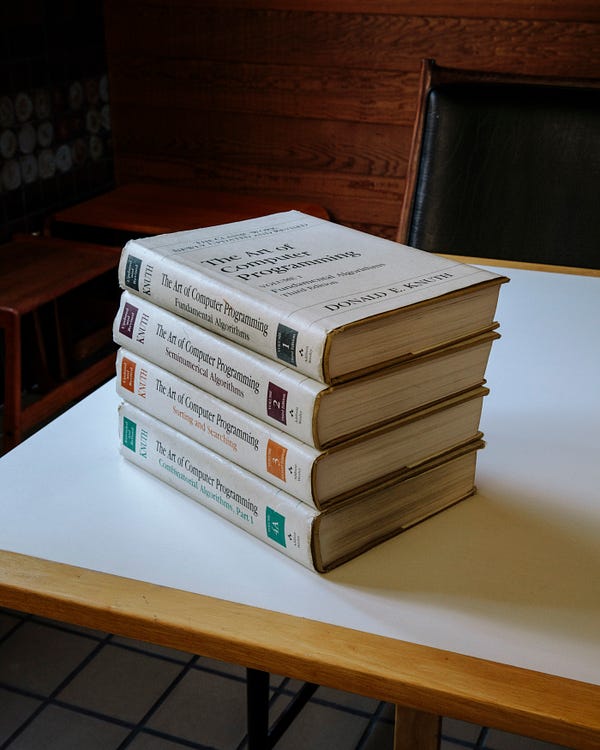

He is the author of “The Art of Computer Programming,” a continuing four-volume opus that is his life’s work. The first volume debuted in 1968, and the collected volumes (sold as a boxed set for about $250) were included by American Scientist in 2013 on its list of books that shaped the last century of science — alongside a special edition of “The Autobiography of Charles Darwin,” Tom Wolfe’s “The Right Stuff,” Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” and monographs by Albert Einstein, John von Neumann and Richard Feynman.

With more than one million copies in print, “The Art of Computer Programming” is the Bible of its field. “Like an actual bible, it is long and comprehensive; no other book is as comprehensive,” said Peter Norvig, a director of research at Google. After 652 pages, volume one closes with a blurb on the back cover from Bill Gates: “You should definitely send me a résumé if you can read the whole thing.”

The volume opens with an excerpt from “McCall’s Cookbook”:

Here is your book, the one your thousands of letters have asked us to publish. It has taken us years to do, checking and rechecking countless recipes to bring you only the best, only the interesting, only the perfect.

Inside are algorithms, the recipes that feed the digital age — although, as Dr.Knuth likes to point out, algorithms can also be found on Babylonian tablets from 3,800 years ago. He is an esteemed algorithmist; his name is attached to some of the field’s most important specimens, such as the Knuth-Morris-Pratt string-searching algorithm. Devised in 1970, it finds all occurrences of a given word or pattern of letters in a text — for instance, when you hit Command+F to search for a keyword in a document.

Now 80, Dr. Knuth usually dresses like the youthful geek he was when he embarked on this odyssey: long-sleeved T-shirt under a short-sleeved T-shirt, with jeans, at least at this time of year. In those early days, he worked close to the machine, writing “in the raw,” tinkering with the zeros and ones.

“Knuth made it clear that the system could actually be understood all the way down to the machine code level,” said Dr. Norvig. Nowadays, of course, with algorithms masterminding (and undermining) our very existence, the average programmer no longer has time to manipulate the binary muck, and works instead with hierarchies of abstraction, layers upon layers of code — and often with chains of code borrowed from code libraries. But an elite class of engineers occasionally still does the deep dive.

“Here at Google, sometimes we just throw stuff together,” Dr. Norvig said, during a meeting of the Google Trips team, in Mountain View, Calif. “But other times, if you’re serving billions of users, it’s important to do that efficiently. A 10-per-cent improvement in efficiency can work out to billions of dollars, and in order to get that last level of efficiency, you have to understand what’s going on all the way down.”

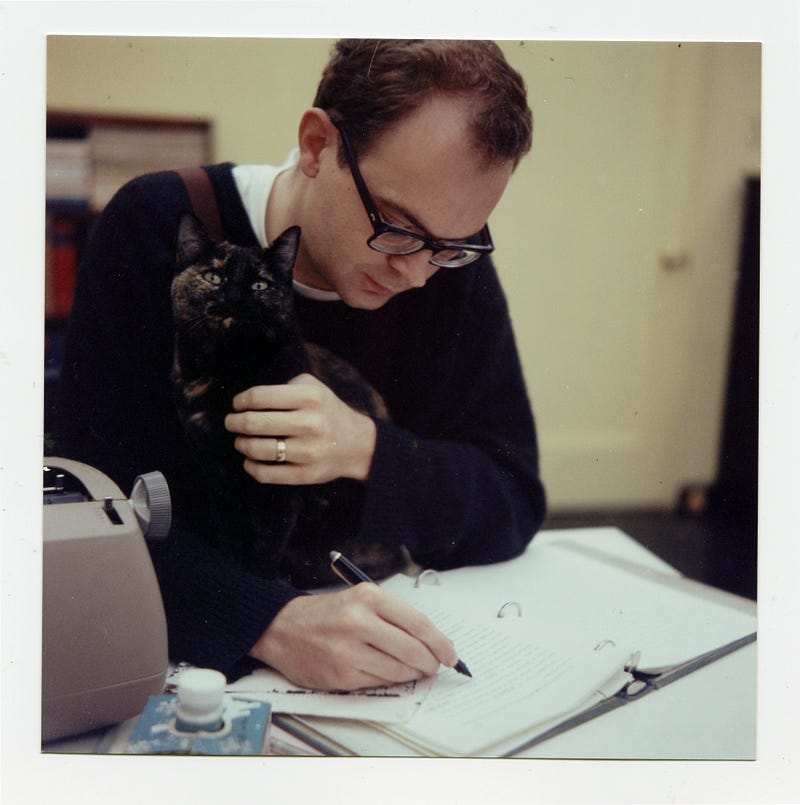

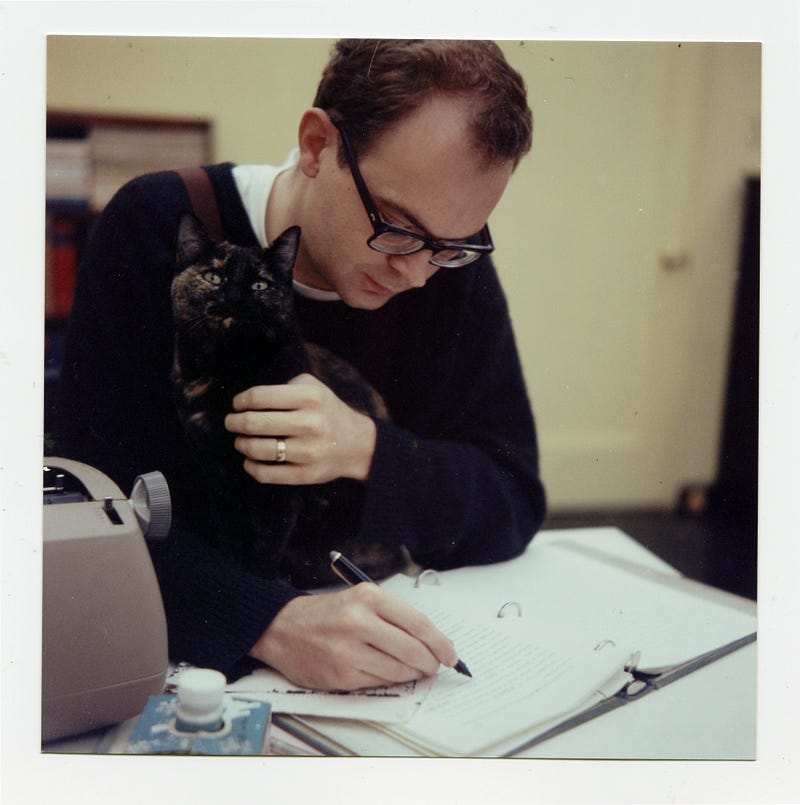

Dr. Knuth at the California Institute of Technology, where he received his Ph.D. in 1963. Photo: Jill Knuth

Or, as Andrei Broder, a distinguished scientist at Google and one of Dr. Knuth’s former graduate students, explained during the meeting: “We want to have some theoretical basis for what we’re doing. We don’t want a frivolous or sloppy or second-rate algorithm. We don’t want some other algorithmist to say, ‘You guys are morons.’”

The Google Trips app, created in 2016, is an “orienteering algorithm” that maps out a day’s worth of recommended touristy activities. The team was working on “maximizing the quality of the worst day” — for instance, avoiding sending the user back to the same neighborhood to see different sites. They drew inspiration from a 300-year-old algorithm by the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler, who wanted to map a route through the Prussian city of Königsberg that would cross each of its seven bridges only once. Dr. Knuth addresses Euler’s classic problem in the first volume of his treatise. (He once applied Euler’s method in coding a computer-controlled sewing machine.)

Following Dr. Knuth’s doctrine helps to ward off moronry. He is known for introducing the notion of “literate programming,” emphasizing the importance of writing code that is readable by humans as well as computers — a notion that nowadays seems almost twee. Dr. Knuth has gone so far as to argue that some computer programs are, like Elizabeth Bishop’s poems and Philip Roth’s “American Pastoral,” works of literature worthy of a Pulitzer.

He is also a notorious perfectionist. Randall Munroe, the xkcd cartoonist and author of “Thing Explainer,” first learned about Dr. Knuth from computer-science people who mentioned the reward money Dr. Knuth pays to anyone who finds a mistake in any of his books. As Mr. Munroe recalled, “People talked about getting one of those checks as if it was computer science’s Nobel Prize.”

Dr. Knuth’s exacting standards, literary and otherwise, may explain why his life’s work is nowhere near done. He has a wager with Sergey Brin, the co-founder of Google and a former student (to use the term loosely), over whether Mr. Brin will finish his Ph.D. before Dr. Knuth concludes his opus.

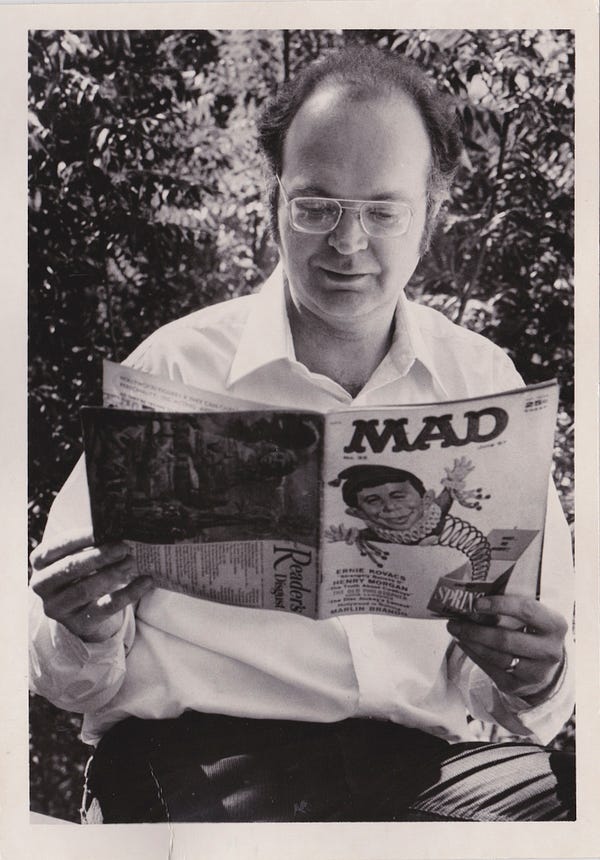

The dawn of the algorithm

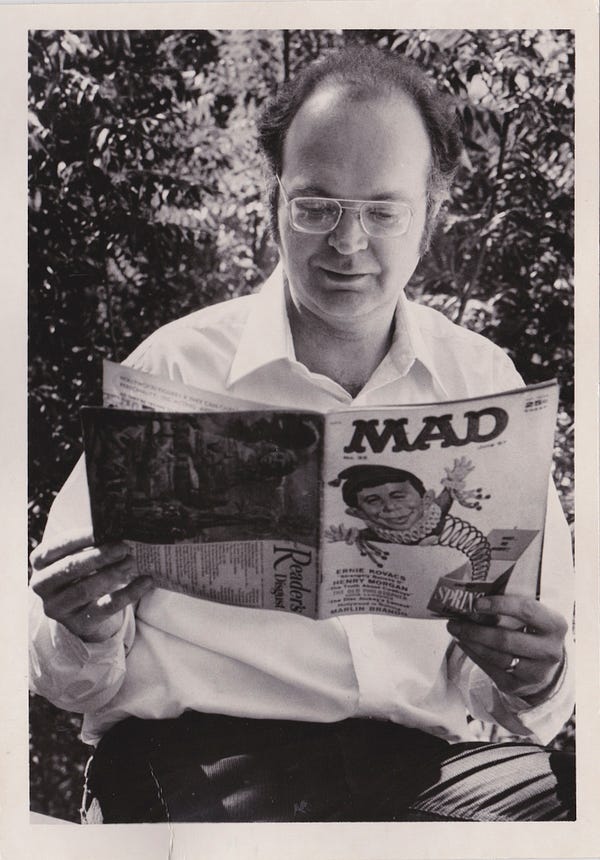

At age 19, Dr. Knuth published his first technical paper, “The Potrzebie System of Weights and Measures,” in Mad magazine. He became a computer scientist before the discipline existed, studying mathematics at what is now Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. He looked at sample programs for the school’s IBM 650 mainframe, a decimal computer, and, noticing some inadequacies, rewrote the software as well as the textbook used in class. As a side project, he ran stats for the basketball team, writing a computer program that helped them win their league — and earned a segment by Walter Cronkite called “The Electronic Coach.”

During summer vacations, Dr. Knuth made more money than professors earned in a year by writing compilers. A compiler is like a translator, converting a high-level programming language (resembling algebra) to a lower-level one (sometimes arcane binary) and, ideally, improving it in the process. In computer science, “optimization” is truly an art, and this is articulated in another Knuthian proverb: “Premature optimization is the root of all evil.”

Eventually Dr. Knuth became a compiler himself, inadvertently founding a new field that he came to call the “analysis of algorithms.” A publisher hired him to write a book about compilers, but it evolved into a book collecting everything he knew about how to write for computers — a book about algorithms.

Left: Dr. Knuth in 1981, looking at the 1957 Mad magazine issue that contained his first technical article. He was 19 when it was published. Photo: Jill Knuth. Right: “The Art of Computer Programming,” volumes 1–4. “Send me a résumé if you can read the whole thing,” Bill Gates wrote in a blurb. Photo: Brian Flaherty

“By the time of the Renaissance, the origin of this word was in doubt,” it began. “And early linguists attempted to guess at its derivation by making combinations like algiros [painful] + arithmos [number].’” In fact, Dr. Knuth continued, the namesake is the 9th-century Persian textbook author Abū ‘Abd Allāh Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī, Latinized as Algorithmi. Never one for half measures, Dr. Knuth went on a pilgrimage in 1979 to al-Khwārizmī’s ancestral homeland in Uzbekistan.

When Dr. Knuth started out, he intended to write a single work. Soon after, computer science underwent its Big Bang, so he reimagined and recast the project in seven volumes. Now he metes out sub-volumes, called fascicles. The next installation, “Volume 4, Fascicle 5,” covering, among other things, “backtracking” and “dancing links,” was meant to be published in time for Christmas. It is delayed until next April because he keeps finding more and more irresistible problems that he wants to present.

In order to optimize his chances of getting to the end, Dr. Knuth has long guarded his time. He retired at 55, restricted his public engagements and quit email (officially, at least). Andrei Broder recalled that time management was his professor’s defining characteristic even in the early 1980s.

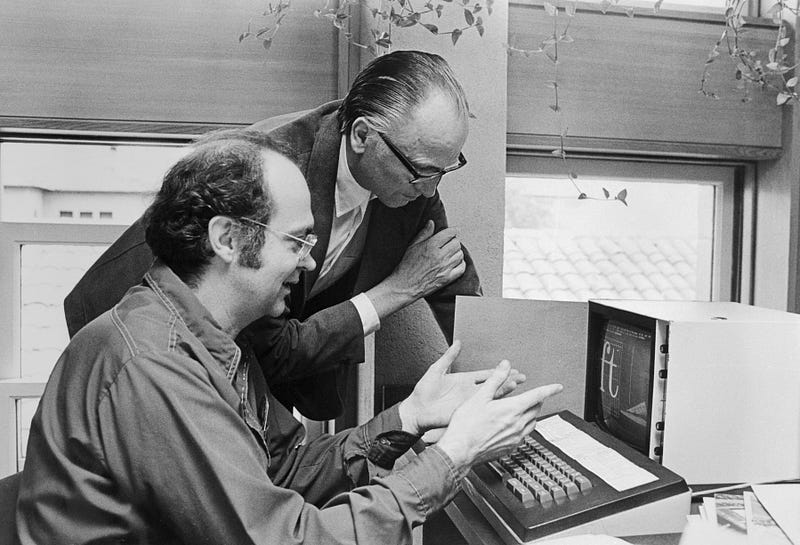

Dr. Knuth typically held student appointments on Friday mornings, until he started spending his nights in the lab of John McCarthy, a founder of artificial intelligence, to get access to the computers when they were free. Horrified by what his beloved book looked like on the page with the advent of digital publishing, Dr. Knuth had gone on a mission to create the TeX computer typesetting system, which remains the gold standard for all forms of scientific communication and publication. Some consider it Dr. Knuth’s greatest contribution to the world, and the greatest contribution to typography since Gutenberg.

This decade-long detour took place back in the age when computers were shared among users and ran faster at night while most humans slept. So Dr. Knuth switched day into night, shifted his schedule by 12 hours and mapped his student appointments to Fridays from 8 p.m. to midnight. Dr. Broder recalled, “When I told my girlfriend that we can’t do anything Friday night because Friday night at 10 I have to meet with my adviser, she thought, ‘This is something that is so stupid it must be true.’”

When Knuth chooses to be physically present, however, he is 100-per-cent there in the moment. “It just makes you happy to be around him,” said Jennifer Chayes, a managing director of Microsoft Research. “He’s a maximum in the community. If you had an optimization function that was in some way a combination of warmth and depth, Don would be it.”

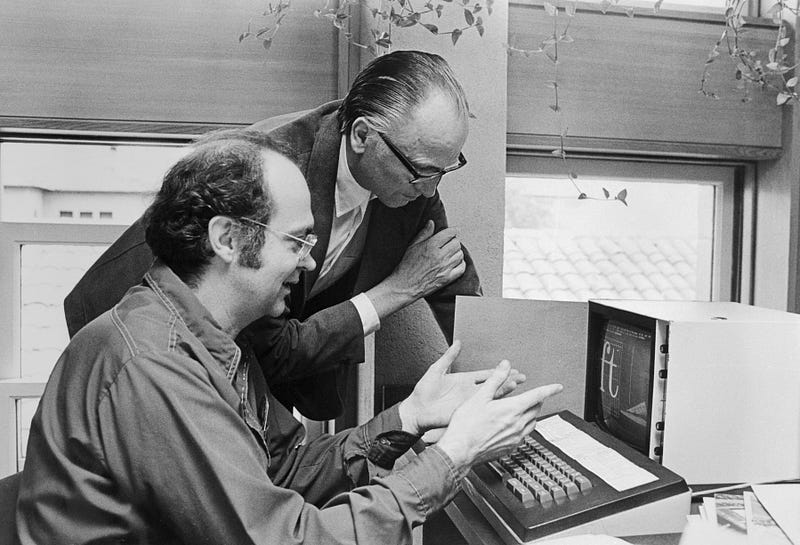

Dr. Knuth discussing typefaces with Hermann Zapf, the type designer. Many consider Dr. Knuth’s work on the TeX computer typesetting system to be the greatest contribution to typography since Gutenberg. Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images

Sunday with the algorithmist

Dr. Knuth lives in Stanford, and allowed for a Sunday visitor. That he spared an entire day was exceptional — usually his availability is “modulo nap time,” a sacred daily ritual from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. He started early, at Palo Alto’s First Lutheran Church, where he delivered a Sunday school lesson to a standing-room-only crowd. Driving home, he got philosophical about mathematics.

“I’ll never know everything,” he said. “My life would be a lot worse if there was nothing I knew the answers about, and if there was nothing I didn’t know the answers about.” Then he offered a tour of his “California modern” house, which he and his wife, Jill, built in 1970. His office is littered with piles of U.S.B. sticks and adorned with Valentine’s Day heart art from Jill, a graphic designer. Most impressive is the music room, built around his custom-made, 812-pipe pipe organ. The day ended over beer at a puzzle party.

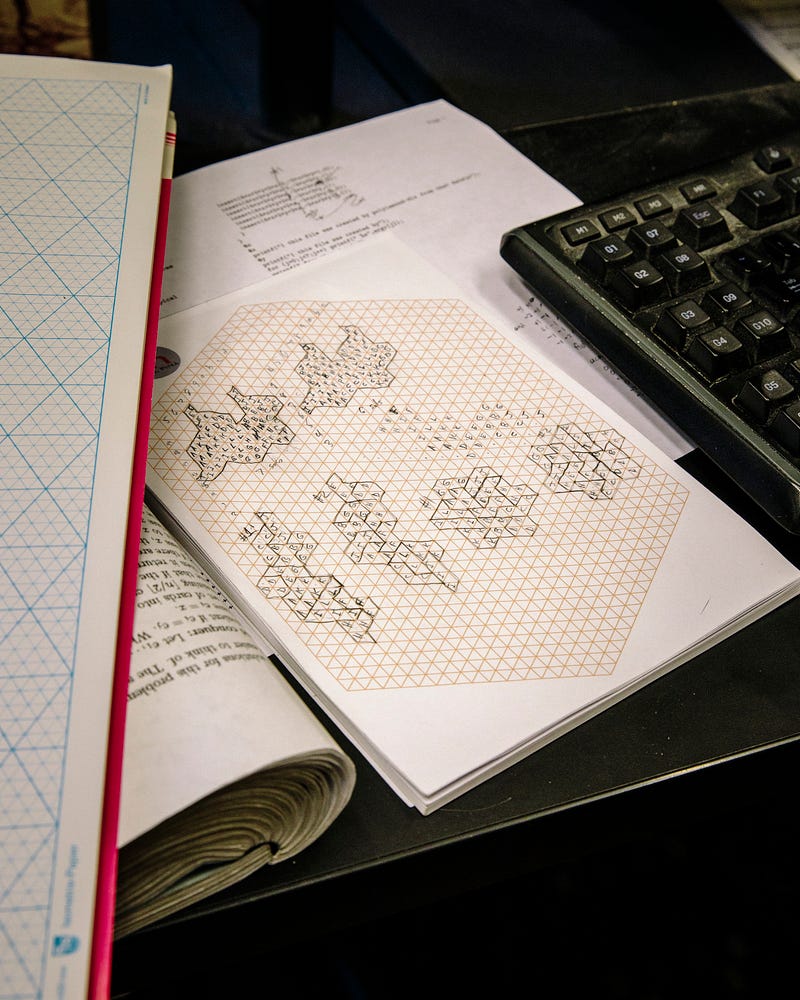

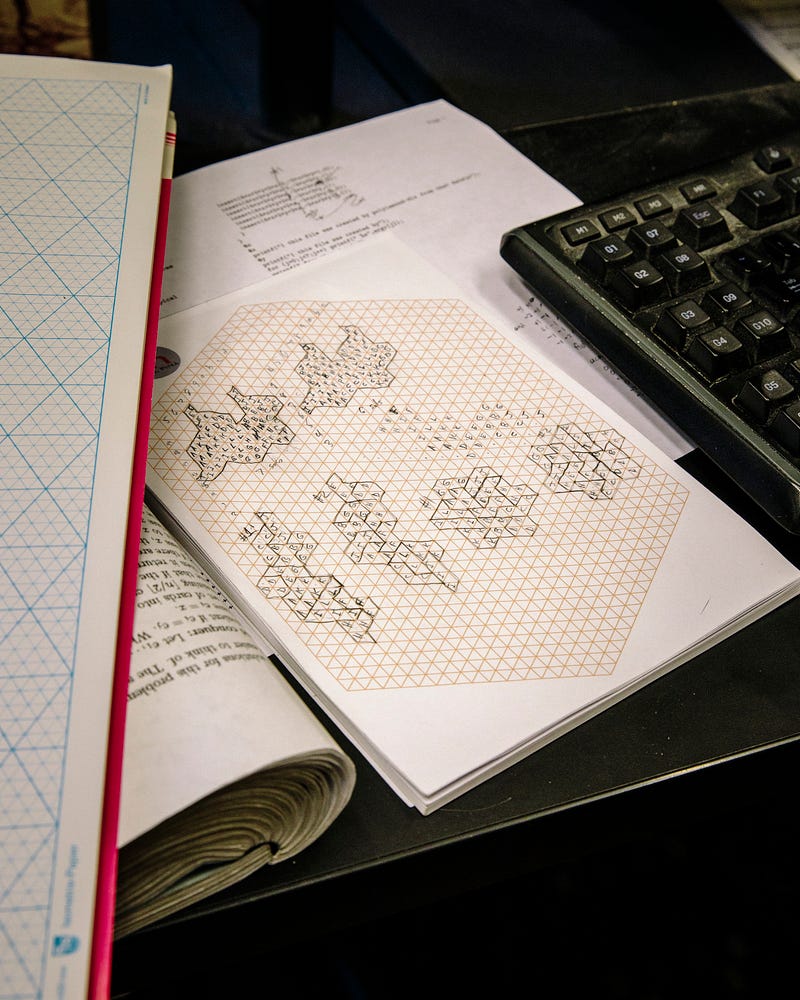

Puzzles and games — and penning a novella about surreal numbers, and composing a 90-minute multimedia musical pipe-dream, “Fantasia Apocalyptica” — are the sorts of things that really tickle him. One section of his book is titled, “Puzzles Versus the Real World.” He emailed an excerpt to the father-son team of Martin Demaine, an artist, and Erik Demaine, a computer scientist, both at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, because Dr. Knuth had included their “algorithmic puzzle fonts.”

“I was thrilled,” said Erik Demaine. “It’s an honor to be in the book.” He mentioned another Knuth quotation, which serves as the inspirational motto for the biannual “FUN with Algorithms” conference: “Pleasure has probably been the main goal all along.”

But then, Dr. Demaine said, the field went and got practical. Engineers and scientists and artists are teaming up to solve real-world problems — protein folding, robotics, airbags — using the Demaines’s mathematical origami designs for how to fold paper and linkages into different shapes.

Of course, all the algorithmic rigmarole is also causing real-world problems. Algorithms written by humans — tackling harder and harder problems, but producing code embedded with bugs and biases — are troubling enough. More worrisome, perhaps, are the algorithms that are not written by humans, algorithms written by the machine, as it learns.

Programmers still train the machine, and, crucially, feed it data. (Data is the new domain of biases and bugs, and here the bugs and biases are harder to find and fix). However, as Kevin Slavin, a research affiliate at M.I.T.’s Media Lab said, “We are now writing algorithms we cannot read. That makes this a unique moment in history, in that we are subject to ideas and actions and efforts by a set of physics that have human origins without human comprehension.” As Slavin has often noted, “It’s a bright future, if you’re an algorithm.”

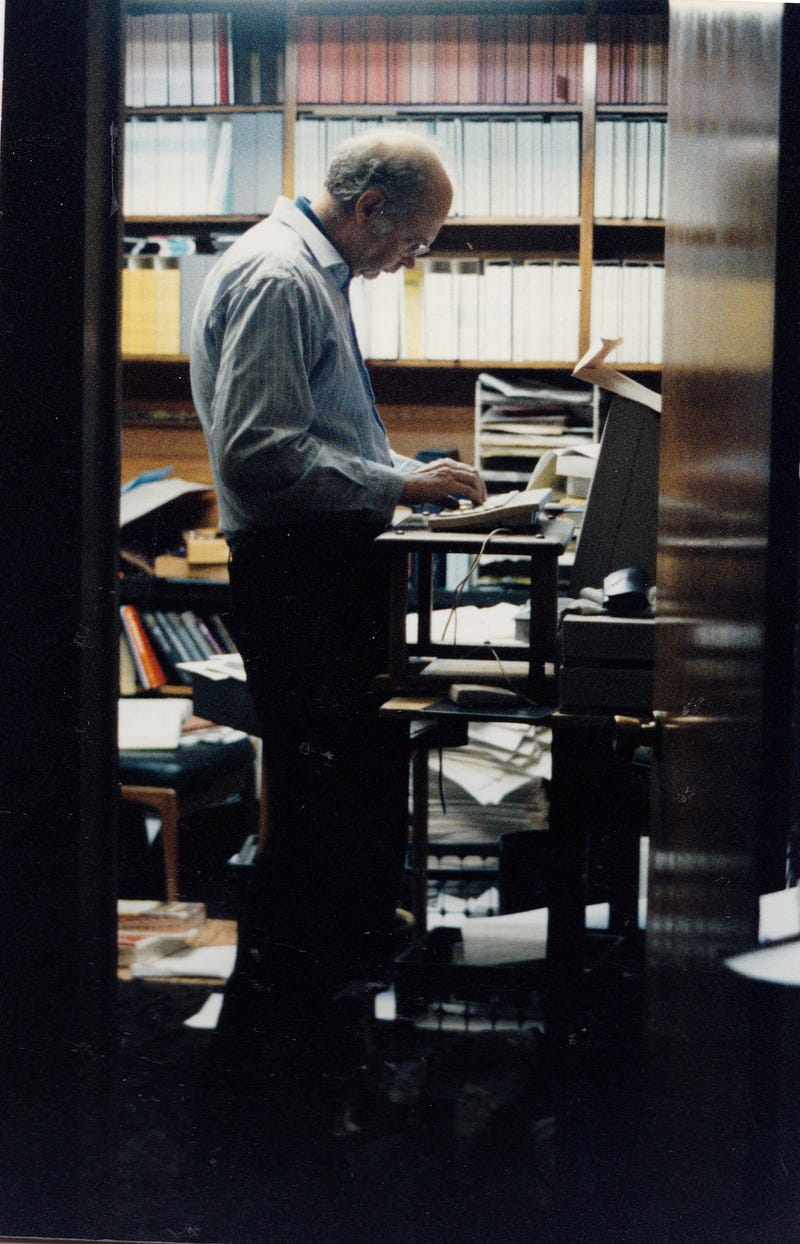

Dr. Knuth at his desk at home in 1999. Photo: Jill Knuth

A few notes. Photo: Brian Flaherty

All the more so if you’re an algorithm versed in Knuth. “Today, programmers use stuff that Knuth, and others, have done as components of their algorithms, and then they combine that together with all the other stuff they need,” said Google’s Dr. Norvig.

“With A.I., we have the same thing. It’s just that the combining-together part will be done automatically, based on the data, rather than based on a programmer’s work. You want A.I. to be able to combine components to get a good answer based on the data. But you have to decide what those components are. It could happen that each component is a page or chapter out of Knuth, because that’s the best possible way to do some task.”

Lucky, then, Dr. Knuth keeps at it. He figures it will take another 25 years to finish “The Art of Computer Programming,” although that time frame has been a constant since about 1980. Might the algorithm-writing algorithms get their own chapter, or maybe a page in the epilogue? “Definitely not,” said Dr. Knuth.

“I am worried that algorithms are getting too prominent in the world,” he added. “It started out that computer scientists were worried nobody was listening to us. Now I’m worried that too many people are listening.”

.jpg)