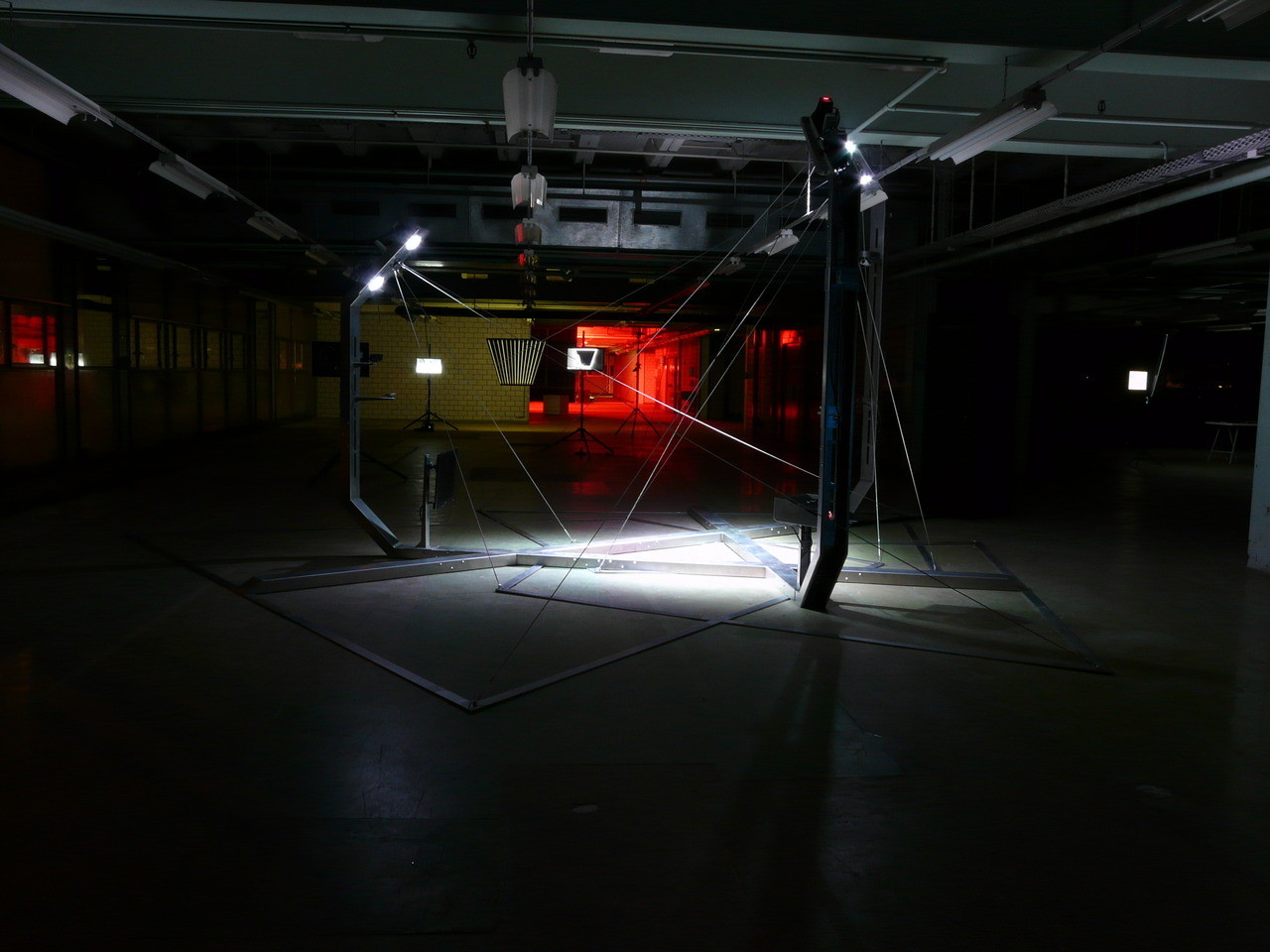

Note: j'avais évoqué récemment cette idée du sublime dans le cadre d'un workshop à l'ECAL, avec pour invités Random International. Il s'agissait alors d'intervenir dans le cadre d'un projet de recherche où nous visions à développer des "contre-propositions" à l'expression actuelle de quelques-unes de nos infrastructures contemporaines, "douces" et "dures". Le "cloud computing" et les data-centers en particulier (le projet en question, en cours et dont le processus est documenté sur un blog: Inhabiting & Interfacing the Cloud(s)). Un projet conduit en collaboration avec Nicolas Nova de la HEAD - Genève

Tout cela s'était développé autour du sentiment d'une technologie, qui mettant aujourd'hui de nouveau "à distance" ses utilisateurs, contribuerait au développement de "croyances" (dimension "magique") et dans certains cas, à la résurgence du sentiment de "sublime", cette fois non plus lié aux puissances natutrelles "terrifiantes", mais aux technologies développées par l'homme. Je n'avais pas fait le lien avec cette thématique très actuelle de l'Anthropocène, que nous avions toutefois déjà commentée et pointée sur ce blog.

C'est fait dorénavant avec beaucoup de nuances par Jean-Baptiste Fressoz. Non sans souligner que "(...) cette opération esthétique, au demeurant très réussie, n’est pas sans poser problème car ce qui est rendu sublime ce n’est évidemment pas l’humanité, mais c’est, de fait, le capitalisme".

...

On peut aussi se souvenir qu'en 1990 déjà, Michel Serres écrivait dans son livre Le Contrat Naturel:

"Voici maintenant formée la contemporaine société, qu'on peut appeler deux fois mondiale: occupant toute la terre, solidaire comme un bloc, par ses interrelations croisées, elle ne dispose d'aucun reste, de recul ni de recours, ou planter sa tente et dans quel extérieur. Elle sait, d'autre part, construire et utiliser des moyens techniques aux dimensions spatiales, temporelles, énergétiques des phénomènes du monde. Notre puissance collective atteint donc les limites de notre habitat global. Nous commençons à ressembler à la Terre."

Texte que nous avions par ailleurs cité avec fabric | ch dans l'un de nos premiers projets, Réalité Recombinée, en 1998.

Via Mouvements (via Nicolas Nova)

-----

Par Jean-Baptiste Fressoz

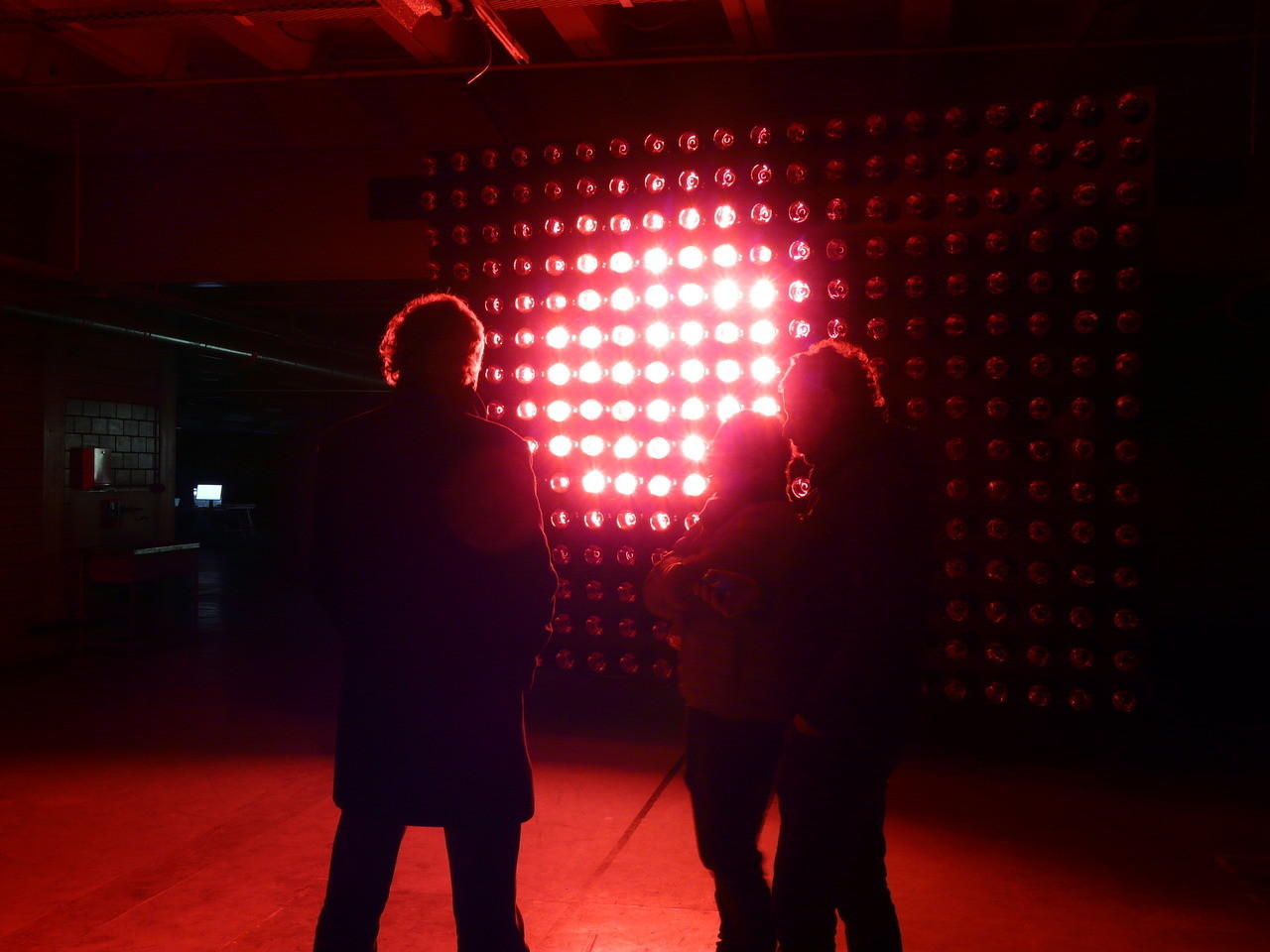

Olafur Eliasson à la Tate Modern.

Pour Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, la force de l’idée d’Anthropocène n’est pas conceptuelle, scientifique ou heuristique : elle est avant tout esthétique. Dans cet article, l’auteur revient, pour en pointer les limites, sur les ressorts réactivés de cette esthétique occidentale et bourgeoise par excellence [note: le sublime], vilipendée par différents courants critiques. Il souligne qu’avant d’embrasser complètement l’Anthropocène, il faut bien se rappeler que le sublime n’est qu’une des catégories de l’esthétique, qui en comprend d’autres (le tragique, le beau…) reposant sur d’autres sentiments (l’harmonie, la douleur, l’amour…), peut-être plus à même de nourrir une esthétique du soin, du petit, du local dont l’agir écologique a tellement besoin.

Aussi sidérant, spectaculaire ou grandiloquent qu’il soit, le concept d’Anthropocène ne désigne pas une découverte scientifique [1]. Il ne représente pas une avancée majeure ou récente des sciences du système-terre. Nom attribué à une nouvelle époque géologique à l’initiative du chimiste Paul Crutzen, l’Anthropocène est une simple proposition stratigraphique encore en débat parmi la communauté des géologues. Faisant suite à l’Holocène (12 000 ans depuis la dernière glaciation), l’Anthropocène est marquée par la prédominance de l’être humain sur le système-terre. Plusieurs dates de départ et marqueurs stratigraphiques afférents sont actuellement débattus : 1610 (point bas du niveau de CO2 dans l’atmosphère causé par la disparition de 90% de la population amérindienne), 1830 (le niveau de CO2 sort de la fourchette de variabilité holocénique), 1945 date de la première explosion de la bombe atomique.

La force de l’idée d’Anthropocène n’est pas conceptuelle, scientifique ou heuristique : elle est avant tout esthétique. Le concept d’Anthropocène est une manière brillante de renommer certains acquis des sciences du système-terre. Il souligne que les processus géochimiques que l’humanité a enclenchés ont une inertie telle que la terre est en train de quitter l’équilibre climatique qui a eu cours durant l’Holocène. L’Anthropocène désigne un point de non retour. Une bifurcation géologique dans l’histoire de la planète Terre. Si nous ne savons pas exactement ce que l’Anthropocène nous réserve (les simulations du système-terre sont incertaines), nous ne pouvons plus douter que quelque chose d’importance à l’échelle des temps géologiques a eu lieu récemment sur Terre.

Le concept d’Anthropocène a cela d’intéressant, mais aussi de très problématique pour l’écologie politique, qu’il réactive les ressorts de l’esthétique du sublime, esthétique occidentale et bourgeoise par excellence, vilipendée par les critiques marxistes, féministes et subalternistes, comme par les postmodernes. Le discours de l’Anthropocène correspond en effet assez fidèlement aux canons du sublime tels que définis par Edmund Burke en 1757. Selon ce philosophe anglais conservateur, surtout connu pour son rejet absolu de 1789, l’expérience du sublime est associée aux sensations de stupéfaction et de terreur ; le sublime repose sur le sentiment de notre propre insignifiance face à une nature lointaine, vaste, manifestant soudainement son omnipuissance. Écoutons maintenant les scientifiques promoteurs de l’Anthropocène :

« L’humanité, notre propre espèce, est devenue si grande et si active qu’elle rivalise avec quelques-unes des grandes forces de la Nature dans son impact sur le fonctionnement du système terre […]. Le genre humain est devenu une force géologique globale [2] ».

La thèse de l’Anthropocène repose en premier lieu sur les quantités phénoménales de matière mobilisées et émises par l’humanité au cours des XIXe et XXe siècles. L’esthétique de la gigatonne de CO2 et de la croissance exponentielle renvoie à ce que Burke avait noté : « la grandeur de dimension est une puissante cause du sublime [3] », et, ajoute-t-il, le sublime demande « le solide et les masses mêmes [4] ». De manière plus précise, l’Anthropocène reporte le sublime de la vaste nature vers « l’espèce humaine ». Tout en jouant du sublime, il en renverse les polarités classiques : la terreur sacrée de la nature est transférée à une humanité colosse géologique.

Or, cette opération esthétique, au demeurant très réussie, n’est pas sans poser problème car ce qui est rendu sublime ce n’est évidemment pas l’humanité, mais c’est, de fait, le capitalisme. L’Anthropocène n’est certainement pas l’affaire d’une « espèce humaine », d’un « anthropos » indifférencié, ce n’est même pas une affaire de démographie : entre 1800 et 2000 la population humaine a été multipliée par sept, la consommation d’énergie par 50 et le capital, si on reprend les chiffres de Thomas Picketty, par 134 [5]. Ce qui a fait basculer la planète dans l’Anthropocène, c’est avant tout une vaste technostructure orientée vers le profit, une « seconde nature », faite de routes, de plantations, de chemins de fer, de mines, de pipelines, de forages, de centrales électriques, de marchés à terme, de porte-containers, de places financières et de banques et bien d’autres choses encore qui structurent les flux de matière et d’énergie à l’échelle du globe selon une logique structurellement inégalitaire. Bref, le changement de régime géologique est bien sûr le fait de « l’âge du capital [6] » bien plus que le fait de « l’âge de l’être humain » dont nous rebattent les récits dominants [7]. Le premier problème du sublime de l’Anthropocène est qu’il renomme, esthétise et surtout naturalise le capitalisme, dont la force se mesure dorénavant à l’aune des manifestations de la première nature – les volcans, la tectonique des plaques ou les variations des orbites planétaires – que deux siècles d’esthétique du sublime nous avaient appris à craindre mais aussi à révérer.

Au sublime de la quantité, l’Anthropocène ajoute le sublime géologique des âges et des éons, duquel il tire ses effets les plus saisissants. La thèse de l’Anthropocène nous dit en substance que les traces de notre âge industriel resteront pour des millions d’années dans les archives géologiques de la planète. Le fait d’ouvrir une nouvelle époque taillée à la mesure de l’être humain signifie que c’est à l’échelle des temps géologiques seulement que l’on peut identifier des événements agissant avec autant de force sur la planète que nous-mêmes : le taux de dioxyde de carbone en 2015 est sans précédent depuis trois millions d’années, le taux actuel d’extinction des espèces, depuis 65 millions d’années, l’acidité des océans, depuis 300 millions d’années, etc. Ce que nous vivons n’est pas une simple « crise environnementale », mais une révolution géologique d’origine humaine. Loin de constituer un cours extérieur, impavide et gigantesque, le temps de la Terre est devenu commensurable au temps de l’agir humain. En deux siècles tout au plus, l’humanité a altéré la dynamique du système-terre pour l’éternité ou presque. « Tout ce qui fait transition n’excite aucune terreur [8] » écrivait Burke. Le discours de l’Anthropocène cultive cette esthétique de la soudaineté, de la bifurcation et de l’événement. Le sublime de l’Anthropocène réside précisément dans cette rencontre extraordinaire : deux siècles d’activité humaine, une durée infime, quasi-nulle au regard de l’histoire terrienne, auront suffi à provoquer une altération comparable au grand bouleversement de la fin du Mésozoïque il y a 65 millions d’années.

La troisième source du sublime anthropocénique est le sublime de la violence souveraine de la nature, celle des tremblements de terre, des tempêtes et des ouragans. Les promoteur·rice·s de l’Anthropocène mobilisent volontiers le sublime romantique des ruines, des civilisations disparues et des effondrements : « Les moteurs de l’Anthropocène pourraient bien menacer la viabilité de la civilisation contemporaine et peut-être même l’existence d’homo sapiens [9] ». Le succès artistique et médiatique du concept repose sur la « jouissance douloureuse », sur le « plaisir négatif » dont parle Burke :

« Nous jouissons à voir des choses que, bien loin de les occasionner, nous voudrions sincèrement empêcher… Je ne pense pas qu’il existe un·e ho·femme assez scélérat·e· pour désirer [que Londres] fût renversée par un tremblement de terre… Mais supposons ce funeste accident arrivé, quelle foule accourrait de toute part pour contempler ses ruines [10] ».

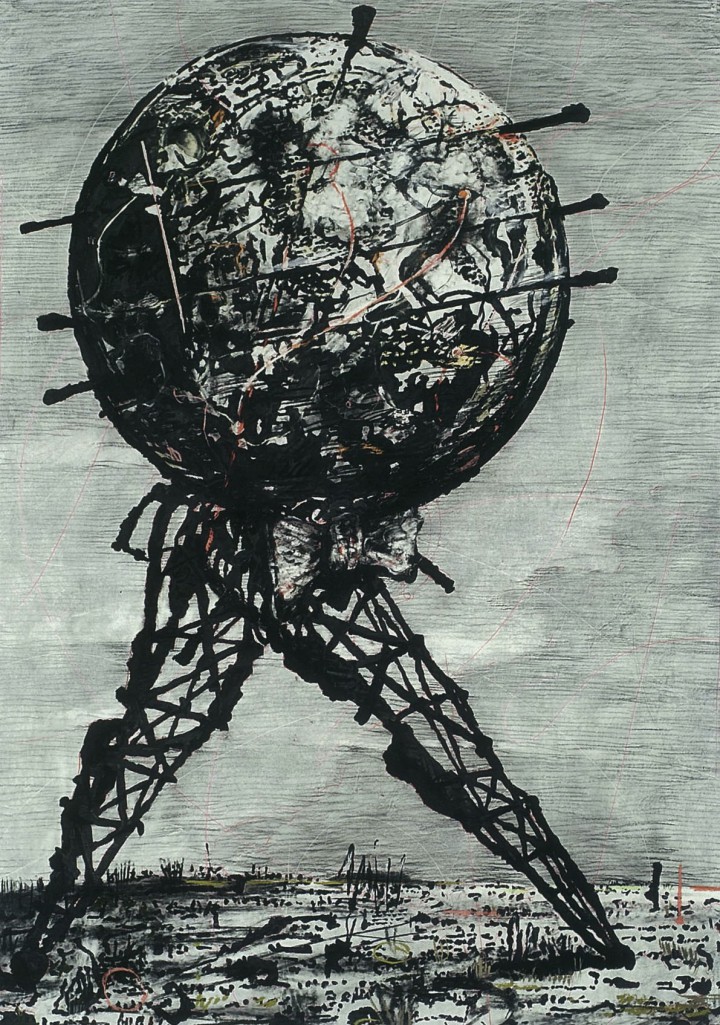

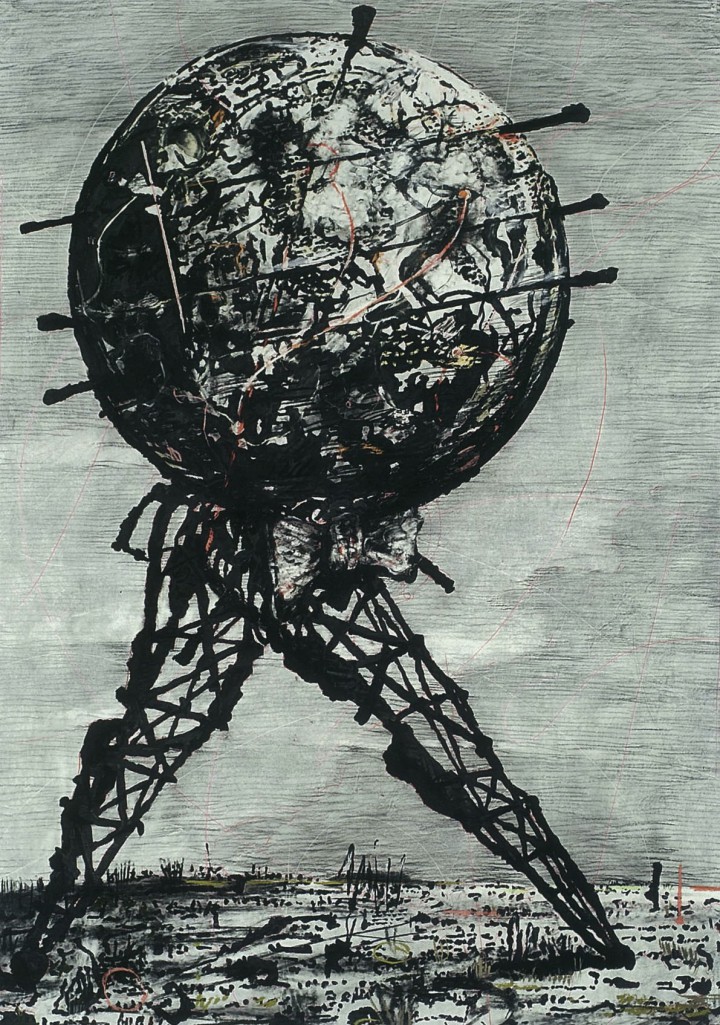

William Kentridge

L’Anthropocène s’appuie sur une culture de l’effondrement propre aux nations occidentales, qui, depuis deux siècles, admirent leur puissance en fantasmant les ruines de leur futur. L’Anthropocène joue des mêmes ressorts psychologiques que le plaisir pervers des décombres déjà décrit par Burke et qui nourrit la vogue actuelle du tourisme des catastrophes de Tchernobyl à ground zero.

La violence de l’Anthropocène est aussi celle de la science hautaine et froide qui nomme les époques et définit notre condition historique. Violence, tout d’abord, de son diagnostic irrévocable : « toi qui entre dans l’Anthropocène abandonne tout espoir » semblent nous dire les savant·e·s. Violence ensuite de la naturalisation, de la « mise en espèce » des sociétés humaines : les statistiques globales de consommation et d’émissions compactent les mille manières d’habiter la terre en quelques courbes, effaçant par la même l’immense variation des responsabilités entre les peuples et les classes sociales. Violence enfin du regard géologique tourné vers nous-mêmes, jaugeant toute l’histoire (empires, guerres, techniques, hégémonies, génocides, luttes, etc.) à l’aune des traces sédimentaires laissées dans la roche. Le géologue de l’Anthropocène est plus effroyable encore que l’ange de l’histoire de Walter Benjamin qui, là même où nous voyions auparavant progrès, ne voyait que catastrophe et désastre : lui n’y voit que fossiles et sédiments.

Que le sublime soit l’esthétique cardinale de l’Anthropocène n’est absolument pas fortuit : sublime et géologie se sont épaulés tout au long de leur histoire. En 1674, Nicolas Boileau traduit en français le traité de Longinus sur le sublime (1er siècle après J.-C.) introduisant ainsi cette notion dans l’Europe lettrée. Mais c’est seulement au milieu du XVIIIe siècle, après que la passion des montagnes et l’intérêt pour la géologie se sont cristallisés dans les classes supérieures, que la « grande nature » devient un objet de sublime [11]. Partis pour leur « grand tour », sur le chemin de l’Italie, les jeunes Anglais·es fortuné·e·s rencontrent en effet la chaîne des Alpes, ses pics vertigineux, ses glaciers terrifiants et ses panoramas immenses. Dans les récits de grands tours, l’expérience de l’effroi face à la nature représente le prix à payer pour goûter la beauté des trésors culturels de l’Italie. Le sublime joue ici un rôle de distinction : être capable de prendre du plaisir en contemplant les glaciers, ou les rochers arides, permettait aux touristes anglais·es de se différencier des guides et des paysan·e·s montagnard·e·s qui n’y voyaient que dangers et terres incultes. Mais c’est évidemment le tremblement de terre de Lisbonne de 1755 qui fournit le véritable coup d’envoi des réflexions sur le sublime : Burke, qui publie son traité l’année suivante, fait référence à la passion esthétique des décombres et des ruines qui saisit alors l’Europe entière. La même année, Emmanuel Kant publie également un court ouvrage sur le tremblement de terre de Lisbonne et, dans son essai ultérieur sur le sublime, il définit ce dernier comme un « plaisir négatif » pouvant procéder de deux manières : le sublime mathématique ressenti devant l’immensité de la nature (l’espace étoilé, l’océan etc.) et le « sublime dynamique » procuré par la violence de la nature (tornade, volcan, tremblement de terre).

Le sublime de l’Anthropocène, et sa mise en scène d’une humanité devenue force tellurique signe la rencontre historique du sublime naturel du XVIIIe siècle et du sublime technologique des XIXe et XXe siècles. Avec l’industrialisation de l’Occident, la puissance de la seconde nature fait l’objet d’une intense célébration esthétique. Le sublime transféré à la technique jouait un rôle central dans la diffusion de la religion du progrès : les gares, les usines et les gratte-ciels en constituaient les harangues permanentes [12]. Dès cette époque, l’idée d’un monde traversé par la technique, d’une fusion entre première et seconde natures fait l’objet de réflexions et de louanges. On s’émerveille des ouvrages d’art matérialisant l’union majestueuse des sublimes naturel et humain : viaducs enjambant les vallées, tunnels traversant les montagnes, canaux reliant les océans, etc. L’idée d’un globe remodelé pour les besoins de l’être humain et fertilisé par la technique constitue une trope classique du positivisme depuis Saint-Simon au moins, qui, dès 1820, écrivait :

« l’objet de l’industrie est l’exploitation du globe, c’est-à-dire l’appropriation de ses produits aux besoins de l’homme, et comme, en accomplissant cette tâche, elle modifie le globe, le transforme, change graduellement les conditions de son existence, il en résulte que par elle, l’homme participe, en dehors de lui-même en quelque sorte, aux manifestations successives de la divinité, et continue ainsi l’œuvre de la création. De ce point de vue, l’Industrie devient le culte [13] ».

De manière plus précise, l’Anthropocène s’inscrit dans une version du sublime technologique reconfigurée par la guerre froide. Il prolonge la vision spatiale de la planète produite par le système militaro-industriel américain, une vision déterrestrée de la Terre saisie depuis l’espace comme un système que l’on pourrait comprendre dans son entièreté, un « spaceship earth » dont on pourrait maîtriser la trajectoire grâce aux nouveaux savoirs sur le système-terre [14]. Le risque est que l’esthétique de l’Anthropocène nourrisse davantage l’hubris d’une géo-ingénierie brutale qu’un travail patient, à la fois modeste et ambitieux d’involution et d’adaptation du social. Pour mémoire, la géo-ingénierie désigne un ensemble de techniques visant à modifier artificiellement le pouvoir réfléchissant de l’atmosphère terrestre pour contrecarrer le réchauffement climatique. Cela peut constituer par exemple à injecter du dioxyde de soufre dans la haute atmosphère afin de réfléchir une partie du rayonnement solaire vers l’espace. L’échec des gouvernements à obtenir un accord international contraignant et ambitieux a contribué à mettre en avant la géo-ingénierie, en tant que « plan B ». Ces techniques potentiellement très risquées pourraient donc soudainement s’imposer en cas « d’urgence climatique ».

Pour ses promoteur·rice·s, l’Anthropocène est une révélation, un éveil, un changement de paradigme désorientant soudainement les représentations vulgaires du monde.

« Par le passé, du fait de la science, l’humanité a dû faire face à de profondes remises en cause de leurs systèmes de croyance. Un des exemples les plus important est la théorie de l’évolution… Le concept d’anthropocène pourrait susciter une réaction hostile similaire à celle que Darwin a produite [15] ».

On retrouve ici le trope romantique du·de la savant·e· payant de sa personne pour lutter contre la foule hostile. En se coupant ainsi du passé et de la décence environnementale commune, en rejetant comme dépassés les savoirs environnementaux qui le précèdent ainsi que les luttes sociales que ces savoirs ont nourries, l’Anthropocène dépolitise l’histoire longue de la destruction de la planète. Avant on ignorait les conséquences globales de l’agir humain, maintenant l’on sait, et, bien entendu, maintenant l’on peut agir. La prétention à la nouveauté des savoirs sur la Terre est aussi une prétention des savants à agir sur celle-ci. Ce n’est pas un hasard si l’inventeur du mot Anthropocène, le prix Nobel de chimie Paul Crutzen, est aussi l’un des avocat·e·s des techniques de géo-ingénierie. À l’Anthropocène inconscient issu de la révolution industrielle succéderait enfin le « bon Anthropocène » éclairé par les savoirs du système-terre. Comme toute forme de scientisme, l’esthétique de l’Anthropocène anesthésie le politique : les « expert·e·s », les autorités vont « faire quelque chose ».

Les expériences du sublime sont toujours à replacer dans un contexte historique et politique particulier. Elles renvoient à des émotions dépendantes des conditions culturelles, naturelles ou technologiques de chaque époque et ce sont ces conditions qui en fournissent les clés de compréhension politique. De la fin du XVIIIe siècle à la fin du siècle suivant, le sublime d’une nature violente et abstraite permettait aux classes bourgeoises urbaines de goûter à la violence de la nature, tout en étant relativement protégées de ses manifestations et de relativiser les dangers bien réels d’un mode de vie technologique et urbain. L’art du sublime nourrissait également le fantasme d’une nature immense et inépuisable au moment précis où l’impérialisme en exploitait les derniers recoins. Dans une culture prenant au sérieux le projet de maîtrise technique de la nature, l’esthétique du sublime fournissait aussi un plaisir légèrement coupable. Enfin, selon le critique marxiste Terry Eagleton, le sublime correspondait aux impératifs esthétiques du capitalisme naissant : contre l’esthétique émolliente du beau, risquant de transformer le sujet bourgeois en sensualiste décadent, le sublime réénergisait le sujet capitaliste comme exploiteur·se ou comme pourvoyeur de travail. Le beau devient à la fin du XVIIIe siècle l’harmonieux, le non-productif, le doux et le féminin ; le sublime : l’effort, le danger, la souffrance, l’élevé, le majestueux et le masculin. Au fond, le sublime, nous dit Eagleton, contenait la menace que la beauté faisait peser sur la productivité [16].

Au début des années 2000, le sublime de l’Anthropocène occupe également une fonction idéologique. Alors que les classes intellectuelles se convertissent au souci écologique, alors qu’elles rejettent les idéaux modernistes de maîtrise de la nature comme has been, alors qu’elles proclament « la fin des grands récits », la fin du progrès, de la lutte des classes, etc., l’Anthropocène procure le frisson coupable d’un nouveau récit sublime. Sur un fond d’agnosticisme quant au futur, l’Anthropocène paraît donner un nouvel horizon grandiose à l’humanité tout entière : prendre en charge collectivement le destin d’une planète. Dans le contexte idéologique terne de l’écologie politique, du développement durable et de la précaution, penser le mouvement d’une humanité devenue force tellurique paraît autrement plus excitant que penser l’involution d’un système économique. Au fond le sublime de l’Anthropocène rejoue assez exactement la scène finale du chef-d’œuvre de Stanley Kubrick, 2001 l’Odyssée de l’espace : l’embryon stellaire contemplant la terre figurant parfaitement l’avènement d’un agent géologique conscient, d’un corps planétaire réflexif. Et c’est bien pour cela que l’Anthropocène fait tressaillir théoricien·ne·s, philosophes et artistes en herbe : il semble désigner un événement métaphysique intéressant.

Pour l’écologie politique contemporaine, l’esthétique sublime de l’Anthropocène pose pourtant problème : en mettant en scène l’hybridation entre première et seconde natures, elle réénergise l’agir technologique des cold warriors (la géo-ingénierie) ; en déconnectant l’échelle individuelle et locale de ce qui importe vraiment (l’humanité force tellurique et les temps géologiques), elle produit sidération et cynisme (no future) ; enfin l’Anthropocène, comme tout autre sublime, est sujet à la loi des rendements décroissants : une fois que l’audience est préparée et conditionnée, son effet s’émousse. En ce sens, désigner une œuvre d’art comme « art de l’Anthropocène » serait absolument fatale à son efficacité esthétique. Le risque est que l’écologie du sublime soit alors appelée à une surenchère permanente, semblable en cela à la course à l’avant-garde dans l’art contemporain. Avant d’embrasser complètement l’Anthropocène, il faut bien se rappeler que le sublime n’est qu’une des catégories de l’esthétique, qui en comprend bien d’autres (le tragique, le beau, le pittoresque…) reposant sur d’autres sentiments (l’harmonie, l’ataraxie, la tristesse, la douleur, l’amour), qui sont peut-être plus à même de nourrir une esthétique du soin, du petit, du local, du contrôle, de l’ancien et de l’involution dont l’agir écologique a tellement besoin.

[1] Cet article reprend sous une forme modifiée un texte déjà paru dans le catalogue de l’exposition Sublime. Les tremblements du monde, Centre Pompidou-Metz, Metz, Centre Pompidou-Metz, 2016.

[2] W. Steffen, J. Grinevald, P. Crutzen, J. McNeill, « The Anthropocene : conceptual and historical perspectives », Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society A, 369, 2011, p. 842–867.

[3] E. Burke, Recherche philosophique sur l’origine de nos idées du sublime et du beau, Paris, Pichon, 1803 (1757), p. 129.

[4] Ibid., p. 225.

[5] T. Piketty, Le capital au XXIe siècle, Paris, Seuil, 2013.

[6] E. Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital : 1848-1975, London, Weindefeld, 1975.

[7] Voir le chapitre « capitalocène » de la nouvelle édition de C. Bonneuil, J.-B. Fressoz, L’événement Anthropocène. La terre, l’histoire et nous, Paris, Seuil, 2016.

[8] E. Burke, op. cit. p. 151.

[9] W. Steffen et al., art. cit.

[10] E. Burke, op. cit., p. 85.

[11] M. Hope Nicholson, Mountain gloom and mountain glory: The development of the aesthetics of the infinite, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1959.

[12] D. Nye, American technological sublime, Cambridge (MA), MIT Press, 1994.

[13] Saint-Simon, Doctrine de Saint-Simon, t. 2, Paris, Aux Bureaux de l’Organisateur, 1830, p. 219.

[14] C. Bonneuil, J.-B. Fressoz, op. cit. ; S. Grevsmühl, La Terre vue d’en haut. L’invention de l’environnement global, Paris, Seuil, 2014.

[15] W. Steffen et al., art. cit.

[16] Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic, Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1990.