Monday, February 05. 2018

Note: 2017 was very busy (the reason why I wasn't able to post much on | rblg...), and the start of 2018 happens to be the same. Fortunately and unfortunatly!

I hope things will calm down a bit next Spring, but in the meantime, we're setting up an exhibition with fabric | ch. A selection of works retracing 20 years of activities, which purpose will be also to serve in the perspective of a photo shooting for a forthcoming book.

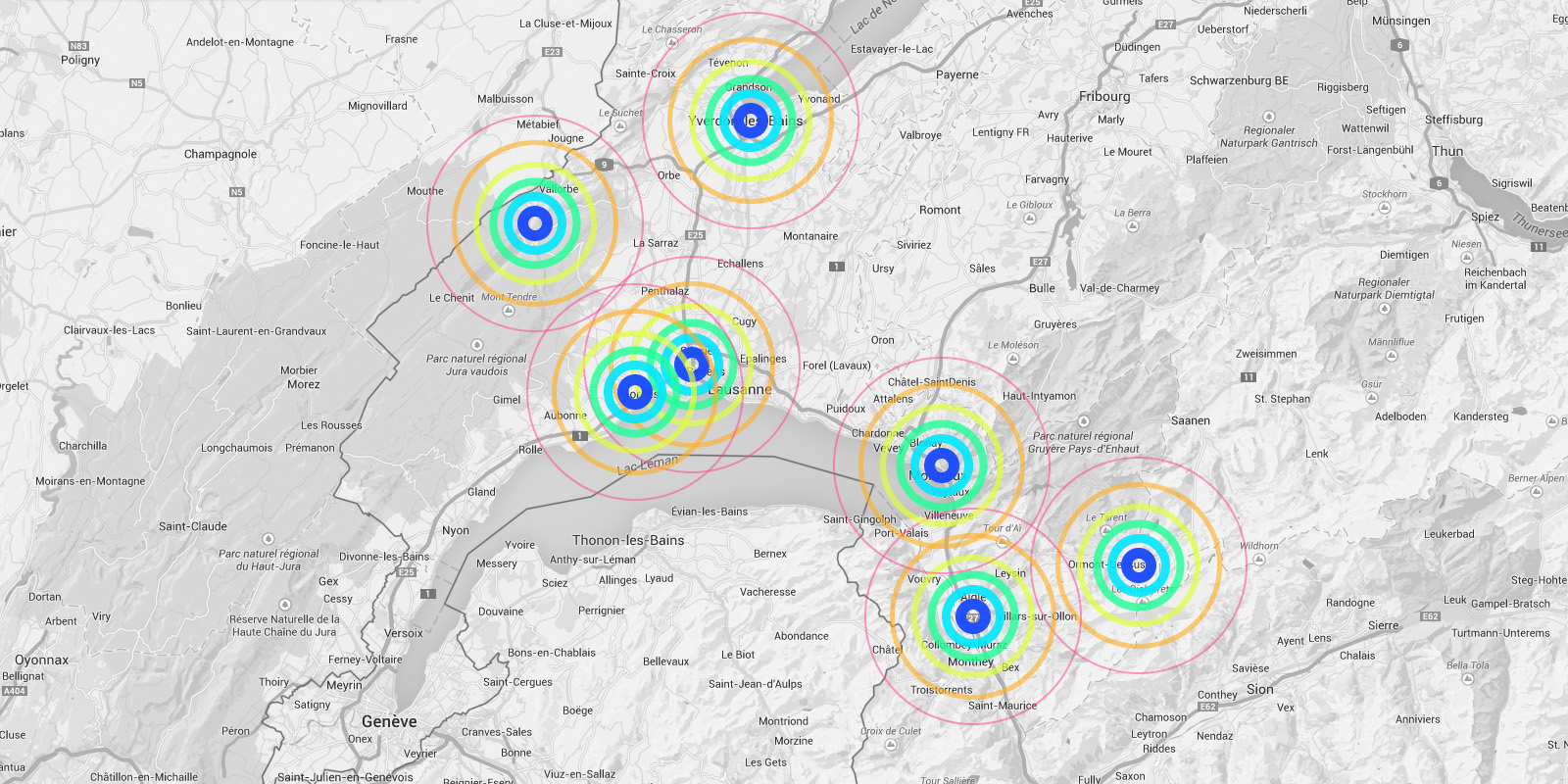

The event will take place in a disuse factory (yet a historical monument from the 2nd industrial era), near Lausanne.

If you are around, do not hesitate to knock at the door!

By fabric | ch

-----

Environmental Devices · Projets & expérimentations (1997-2017)

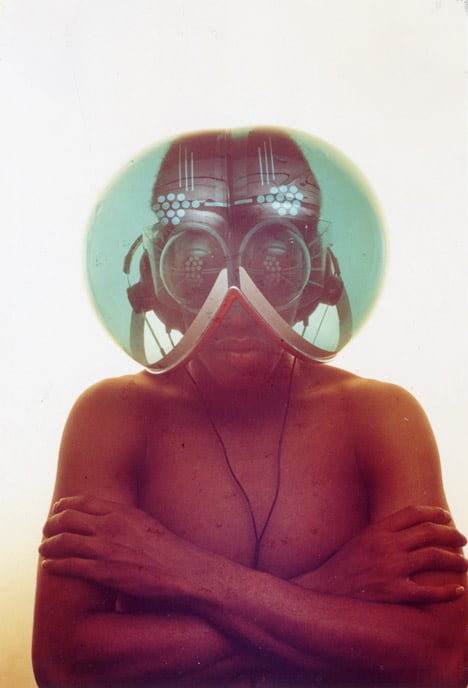

Image: Daniela & Tonatiuh.

During a few days, in the context of the preparation of a book, a selection of works retracing 20 years of activities of fabric | ch will be on display in a disused factory close to Lausanne.

·

Information: http://www.fabric.ch/xx/

·

Opening on February 9, 5.00-11.00pm

·

Visiting hours:

Saturday - Sunday 10-11.02, 4.00-8.00pm

Wednesday 14.02, 5.00-8.00pm

Friday-Saturday 16-17.02, 5.00-8.00pm.

·

Or by appointment: 021.3511021

Guided tours at 6.00pm

-----

Pendant quelques jours et dans le contexte de la création d'un livre monographique, accrochage d'une sélection de travaux retraçant 20 ans d'activités de fabric | ch.

·

Informations: http://www.fabric.ch/xx

·

Vernissage le 9 février, 17h-23h

·

Heures de visite:

Samedi - dimanche 10-11.02, 16h-20h

Mercredi 14.02, 17h-20h

Vendredi-samedi 16-17.02, 17h-20h00

·

Ou sur rendez-vous: 021.3511021

Visites commentées à 18h.

&

Event on Facebook.

Friday, December 15. 2017

Note: with a bit of delay (delay can be an interesting attitude nowadays), but the show is still open... and the content still very interesting!

Via Archpaper

-----

New MoMA show plots the impact of computers on architecture and design. Pictured here: “Menu 23" layout of Cedric Price's Generator Project. (Courtesy California College of the Arts archive)

The beginnings of digital drafting and computational design will be on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) starting November 13th, as the museum presents Thinking Machines: Art and Design in the Computer Age, 1959–1989. Spanning 30 years of works by artists, photographers, and architects, Thinking Machines captures the postwar period of reconciliation between traditional techniques and the advent of the computer age.

Organized by Sean Anderson, associate curator in the museum’s Department of Architecture and Design, and Giampaolo Bianconi, a curatorial assistant in the Department of Media and Performance Art, the exhibition examines how computer-aided design became permanently entangled with art, industrial design, and space planning.

Drawings, sketches, and models from Cedric Price’s 1978-80 Generator Project, the never-built “first intelligent building project” will also be shown. The response to a prompt put out by the Gilman Paper Corporation for its White Oak, Florida, site to house theater and dance performances alongside travelling artists, Price’s Generator proposal sought to stimulate innovation by constantly shifting arrangements.

Ceding control of the floor plan to a master computer program and crane system, a series of 13-by-13-foot rooms would have been continuously rearranged according to the users’ needs. Only constrained by a general set of Price’s design guidelines, Generator’s program would even have been capable of rearranging rooms on its own if it felt the layout hadn’t been changed frequently enough. Raising important questions about the interaction between a space and its occupants, Generator House laid the groundwork for computational architecture and smart building systems.

R. Buckminster Fuller’s 1970 work for Radical Hardware magazine will also appear. (Courtesy PBS)

Thinking Machines: Art and Design in the Computer Age, 1959–1989 will be running from November 13th to April 8th, 2018. MoMA members can preview the show from November 10th through the 12th.

Monday, October 09. 2017

Note: I'll have the great pleasure to be in discussion tomorrow with Fabio Gramazio, Prof. & Head for Digital fabrication at ETHZ and partner at Gramazio Kohler, during the much-awaited symposium "Research in Art and Design", at ECAL.

If you can attend, please do so! As we're expecting great presentations from the likes of Xavier Veilhan, Roel Wouters, Skylar Tibbits, Catherine Ince and several others... including Fabio Gramazio of course, who will speak about their rescent researches at the Swiss Institute of Technology / Department of Architecture in Zürich.

Via ECAL

-----

10+10 Research in Art & Design at ECAL

A symposium celebrating 10 years of Research in Art and Design

Tuesday 10 October 2017, 8.00–18.30

IKEA Auditorium, ECAL, Renens

www.researchday.ch

On the occasion of the 10 years since the moving of ECAL/University of Art and Design Lausanne to its current premises in Renens and marking the 10th anniversary of the foundation of EPFL+ECAL Lab, ECAL is hosting a symposium on Research in Art and Design, featuring artists, designers and scholars in these fields from all over the world, in conversation with ECAL faculty members.

Admission is free upon registration through the online RSVP form at www.researchday.ch

Due to the limited number of seats in the auditorium, the maximum number of participants is 350.

---

Programme

8.00–8.30 Registration

8.30–9.00 Welcome

Alexis Georgacopoulos director, ECAL

Introductory notes on Research in Art and Design in Switzerland

Davide Fornari professor, ECAL

Moderation

Vera Sacchetti design critic, Basel

Design Research: from Academia to the Real World

9.00–9.45 Alba Cappellieri professor, Politecnico di Milano, Milan

in conversation with Nicolas Henchoz director, EPFL+ECAL Lab

9.45–10.30 Sophie Pène vice president, Conseil National du Numérique, Paris

in conversation with Davide Fornari professor, ECAL

10.30–11.00 Coffee break

Research Through Art and Design: Materials and Forms

11.00–11.45 Xavier Veilhan artist, Paris

in conversation with Stéphanie Moisdon professor, ECAL

11.45–12.30 Fabio Gramazio co-founder, Gramazio + Kohler Architects, Zurich

in conversation with Patrick Keller professor, ECAL

-

12.30–13.30 Lunch

-

Research Practices in Curating Art and Design

13.30–14.15 Catherine Ince senior curator, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

in conversation with Anniina Koivu professor, ECAL

14.15–15.00 Astrid Welter head of programs, Fondazione Prada, Milan/Venice

in conversation with Federico Nicolao professor, ECAL

15.00–15.15 Coffee break

The Future of Art and Design Research

15.15–16.00 Roel Wouters co-founder, Moniker, Amsterdam

in conversation with Vincent Jacquier professor, ECAL

16.00–16.45 Skylar Tibbits co-founder, MIT Self-Assembly Lab, Cambridge (MA)

in conversation with Christophe Guberan professor, ECAL

16.45 Closing remarks, panel discussion

Alexis Georgacopoulos

Vera Sacchetti

Davide Fornari

---

17.30 Exhibition openings at Cinema Studio, Gallery l’elac and EPFL+ECAL Lab

- Caustics, curated by Mark Pauly, EPFL RAYFORM

- Projects for Victorinox, curated by Thilo Alex Brunner

- The Sausage of the Future, curated by Carolien Niebling (preview)

- Augmented Photography, curated by Milo Keller (preview)

- EPFL+ECAL Lab Research Land, curated by Nicolas Henchoz

- Rapid Liquid Printing, curated by Christophe Guberan, MIT Self-Assembly Lab, Steelcase

ECAL will launch the book Making Sense: 10 Years of Research in Art and Design at ECAL on the occasion of the symposium.

---

18.30 Cocktail

10+10 Research in Art and Design at ECAL

In collaboration with EPFL+ECAL Lab

With the support of HES-SO

Media partner Disegno

Ecole cantonale d’art de Lausanne

5, Avenue du Temple, Renens

Wednesday, February 08. 2017

Note: interesting exhibition and economic setup (by Fala Atelier) for an exhibition about the metabolists in Lisbon --Nagakin Capsule Tower specifically--, in one of the many marvelous yet rotten "palaces" of the City!

Via ArchDaily

-----

Finding a place to live in Tokyo isn't easy. Most of the available options are expensive and usually located far from the center. Typologically, the Nakagin Capsule Tower continues to prove that it makes sense. Designed by Kisho Kurokawa and built in 1972, it represented a new typology and a different approach to the idea of urban renewal.

Nevertheless, forty years later, it is clear that something went wrong along the way. The building is getting emptier and several of the capsules are abandoned, rotten, leaking. Some of the owners want to demolish it; a few offer resistance. Each capsule was supposed to last 20 years but twice the time has passed.

Metabolism’s biggest icon is sick and stands today only as a remembrance of a future that never happened.

Anticlimax was an exhibition about the contemporary routine of a fallen hero. While presenting its current condition, the exhibition intended to illustrate the contemporary daily life of one of the most iconic buildings of the 20th Century.

Exhibiting the former metabolist superstar in Portugal was also a provocation and the layout for the exhibition was a necessary curatorial dead-end: presenting the Nakagin in a traditional way would be conceptually wrong. The exhibition happens in an almost negligent way, reflecting the condition of the building, bringing its sense of scale and repetition to the Sinel de Cordes Palace.

All pictures © Fernando Guerra.

More images HERE.

Tuesday, July 05. 2016

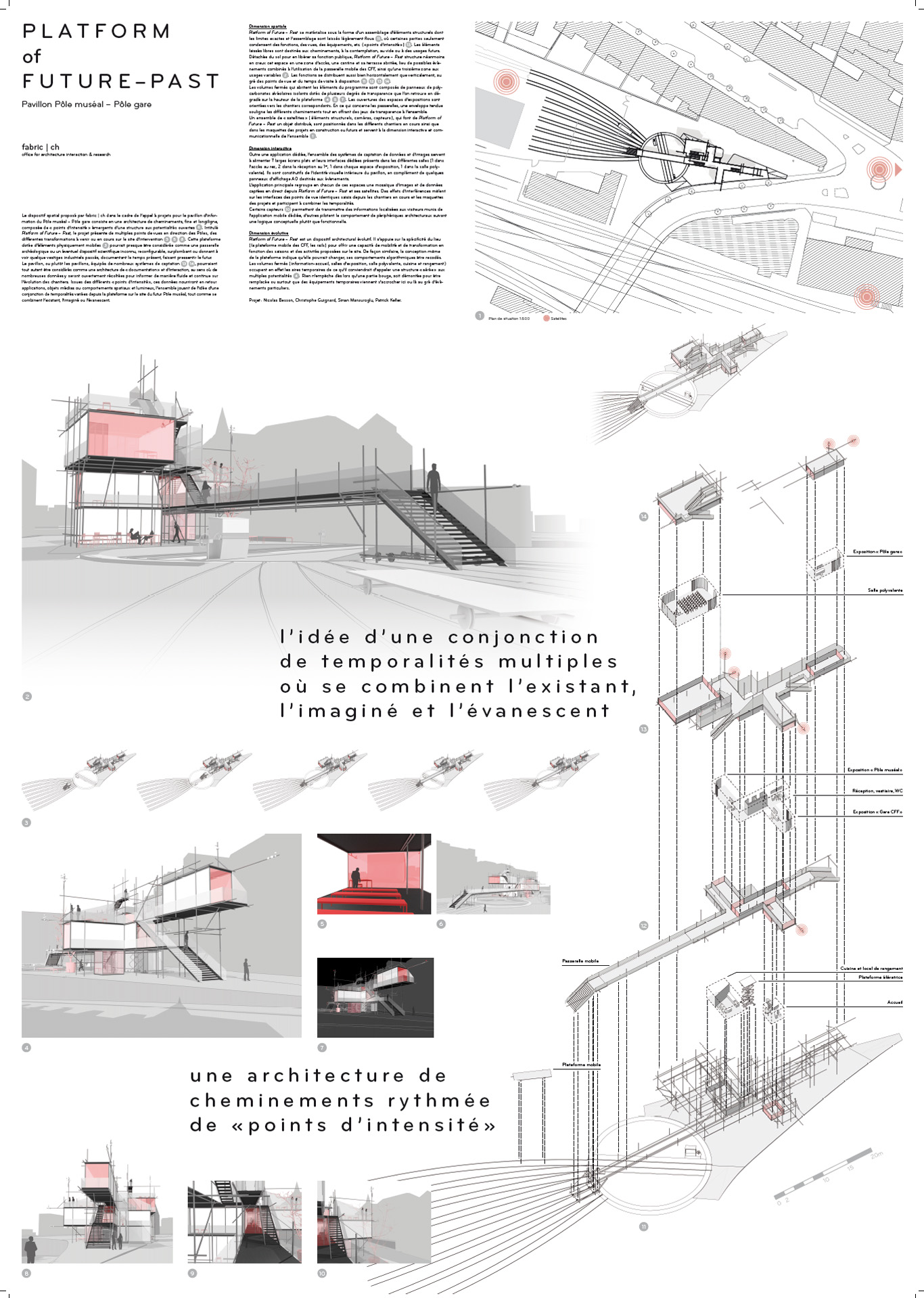

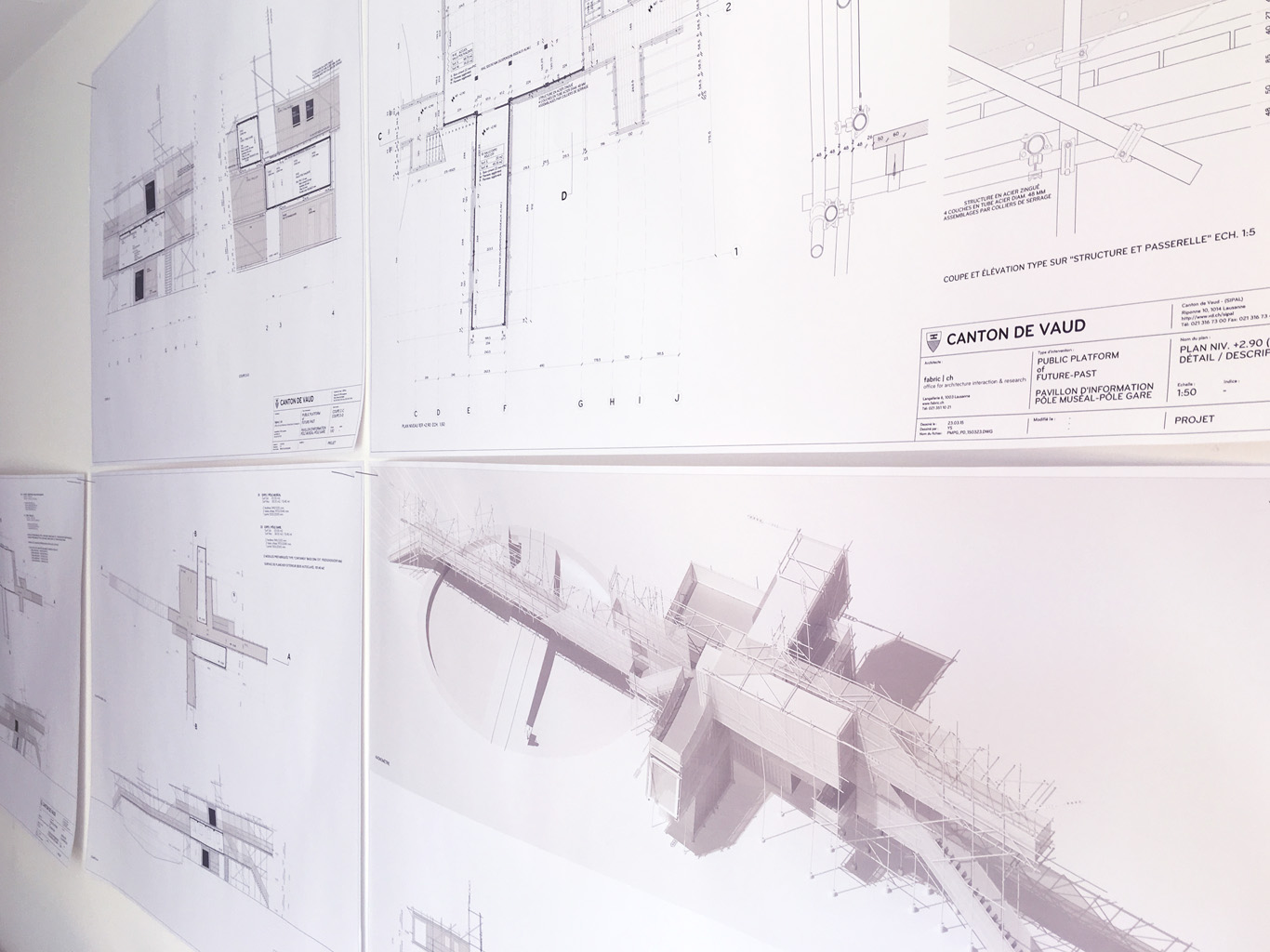

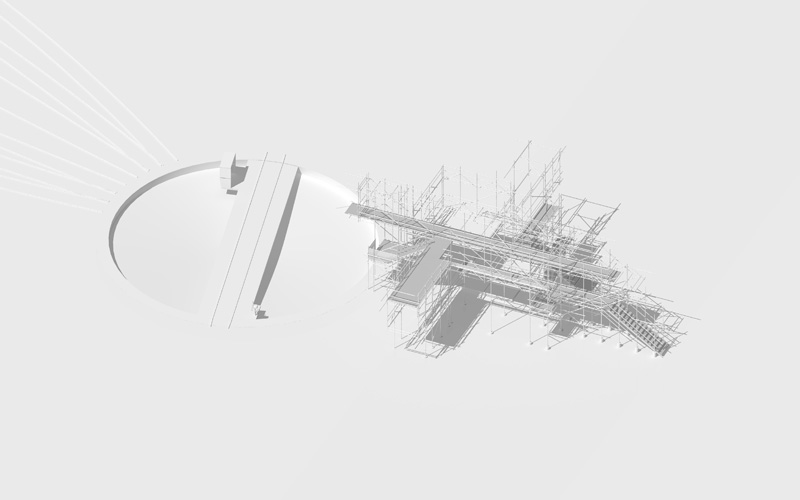

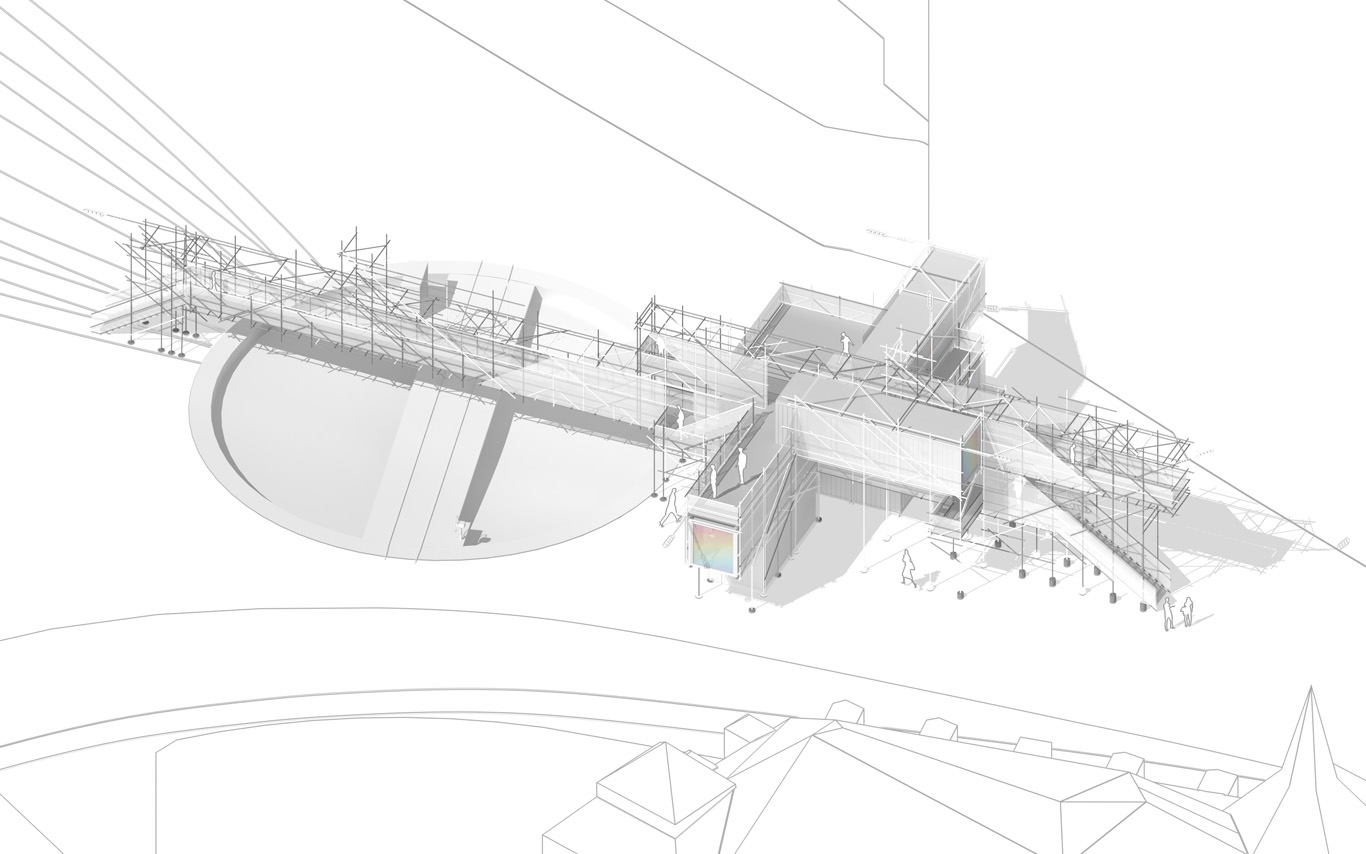

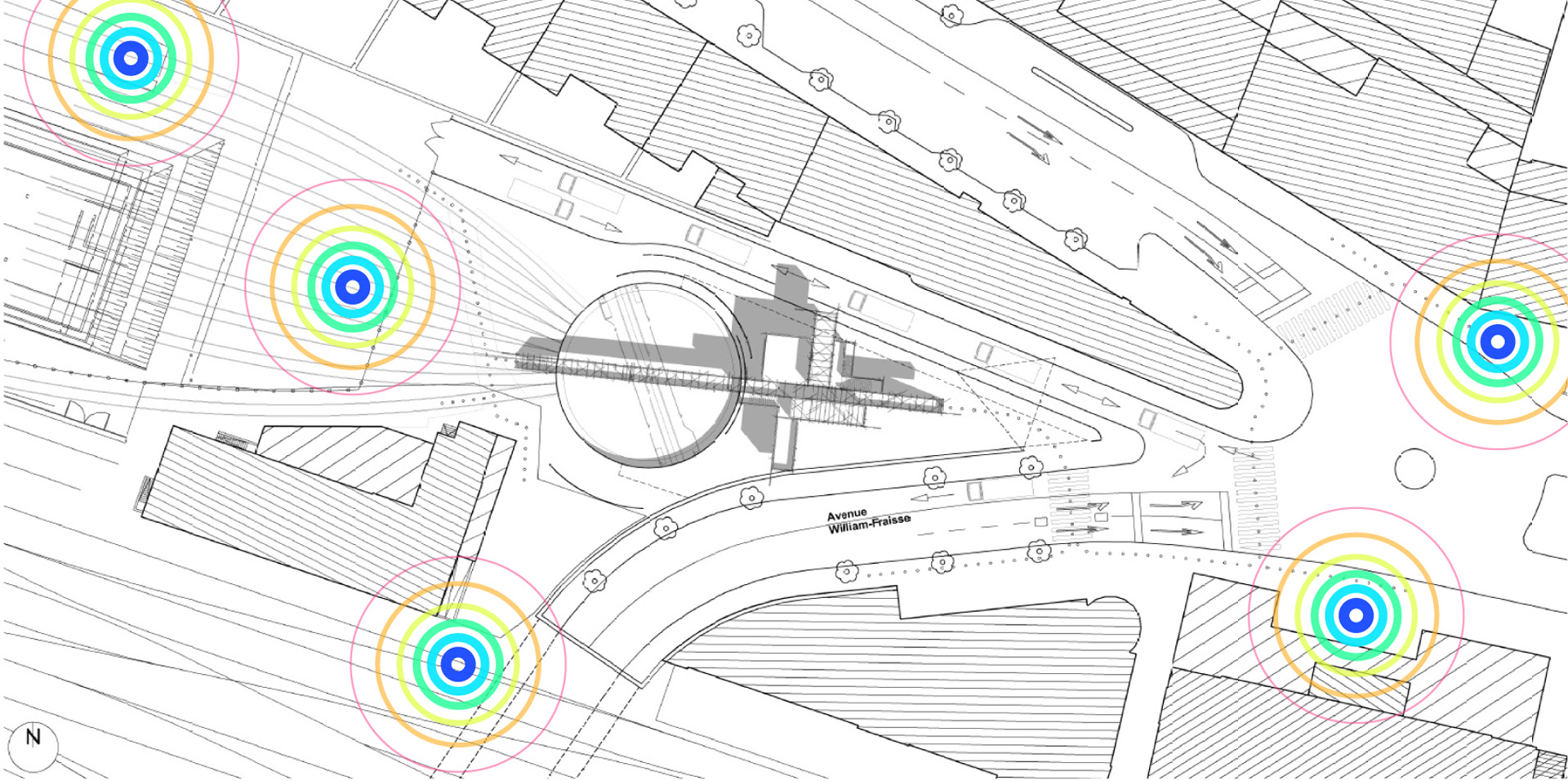

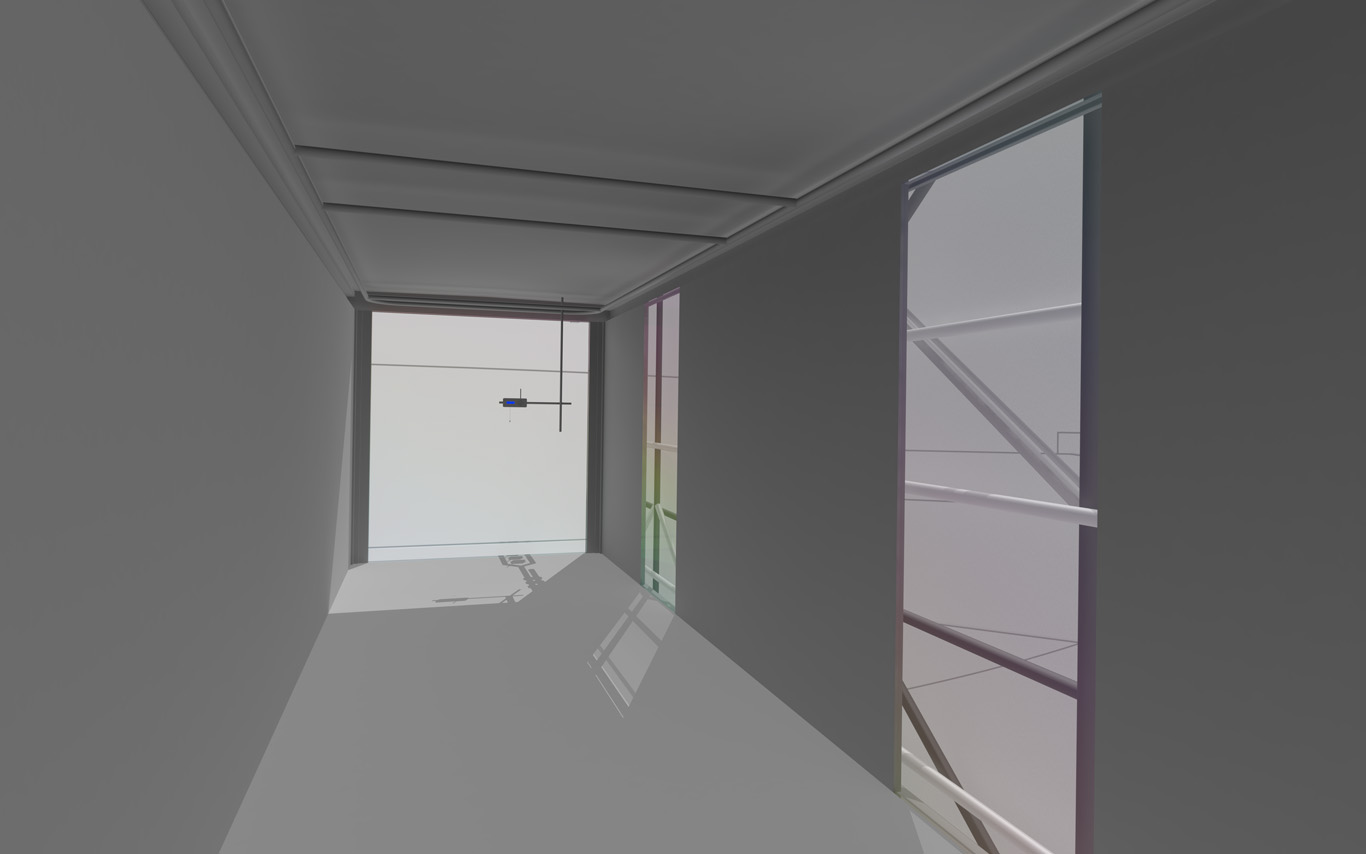

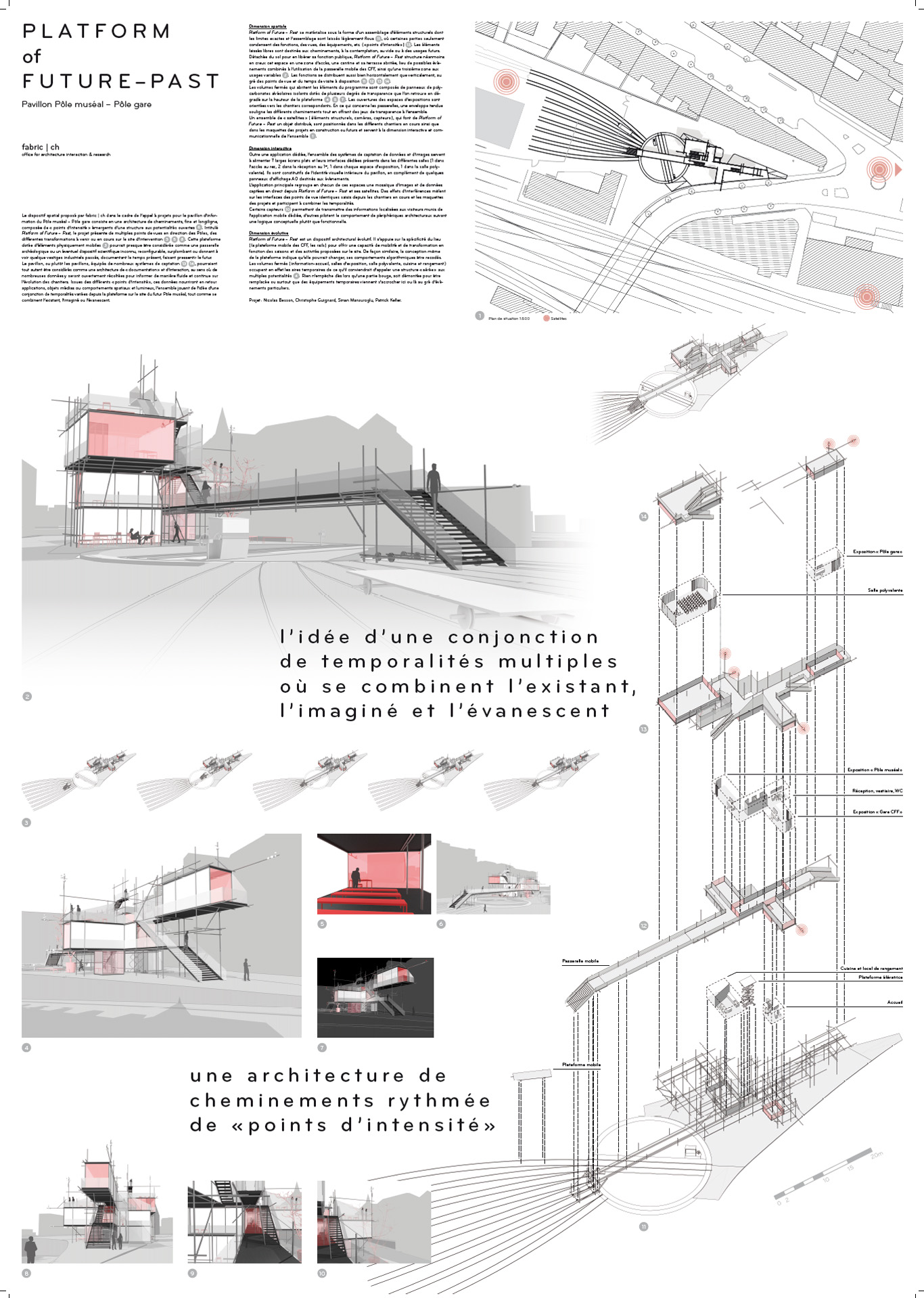

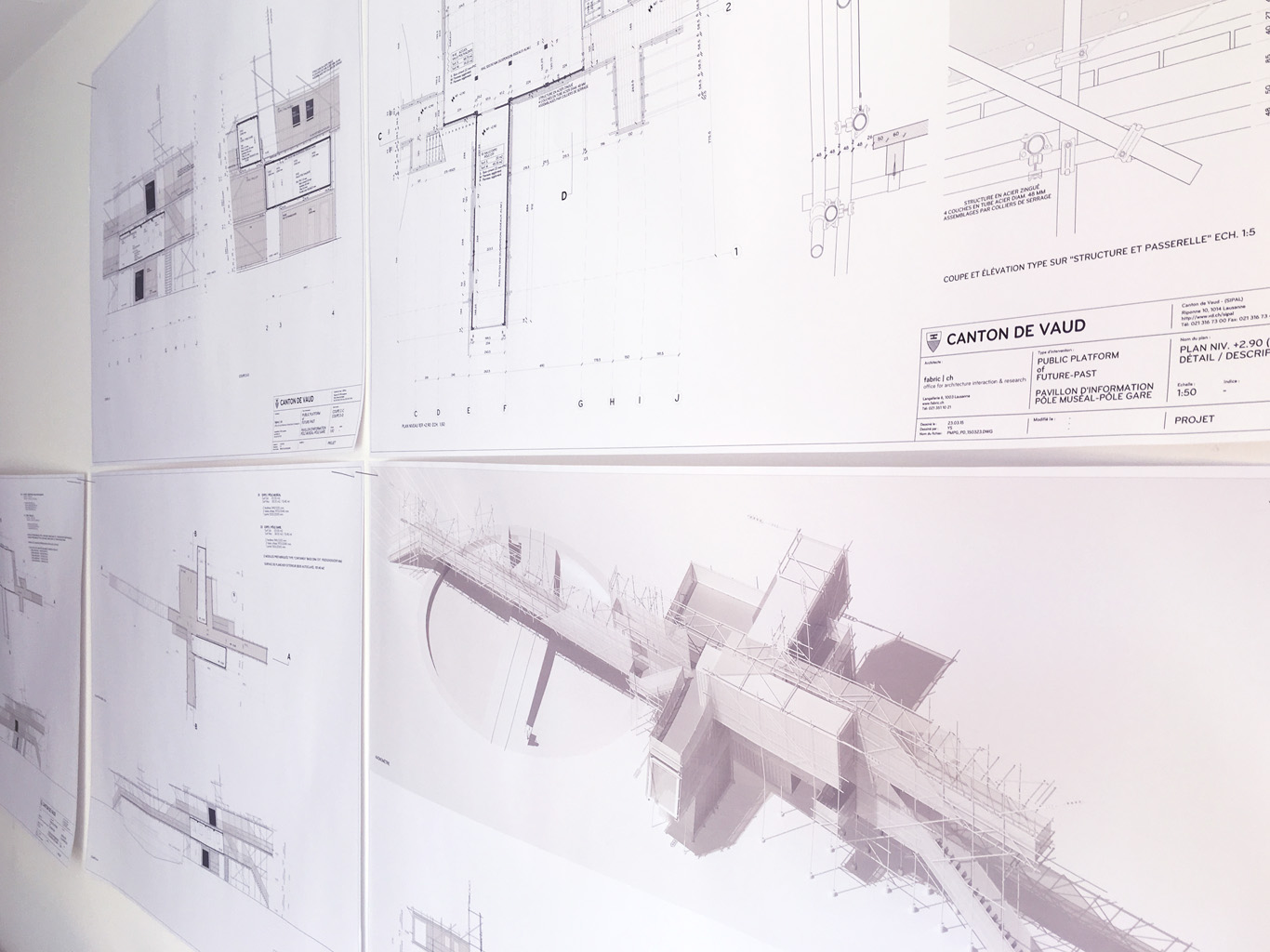

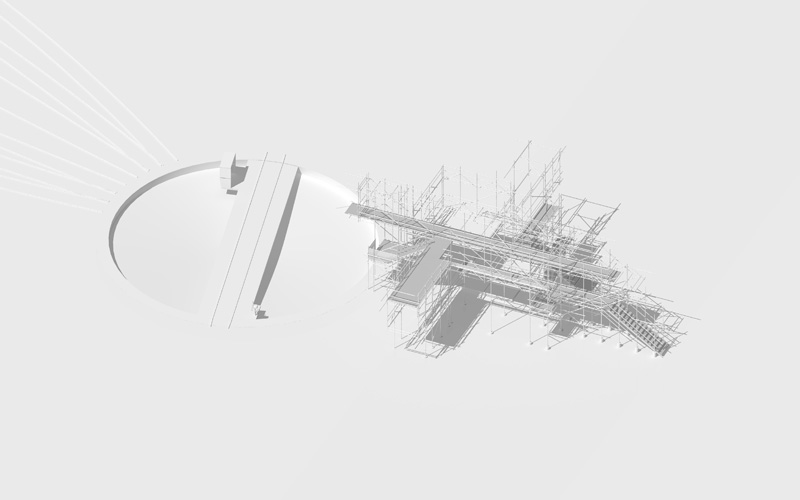

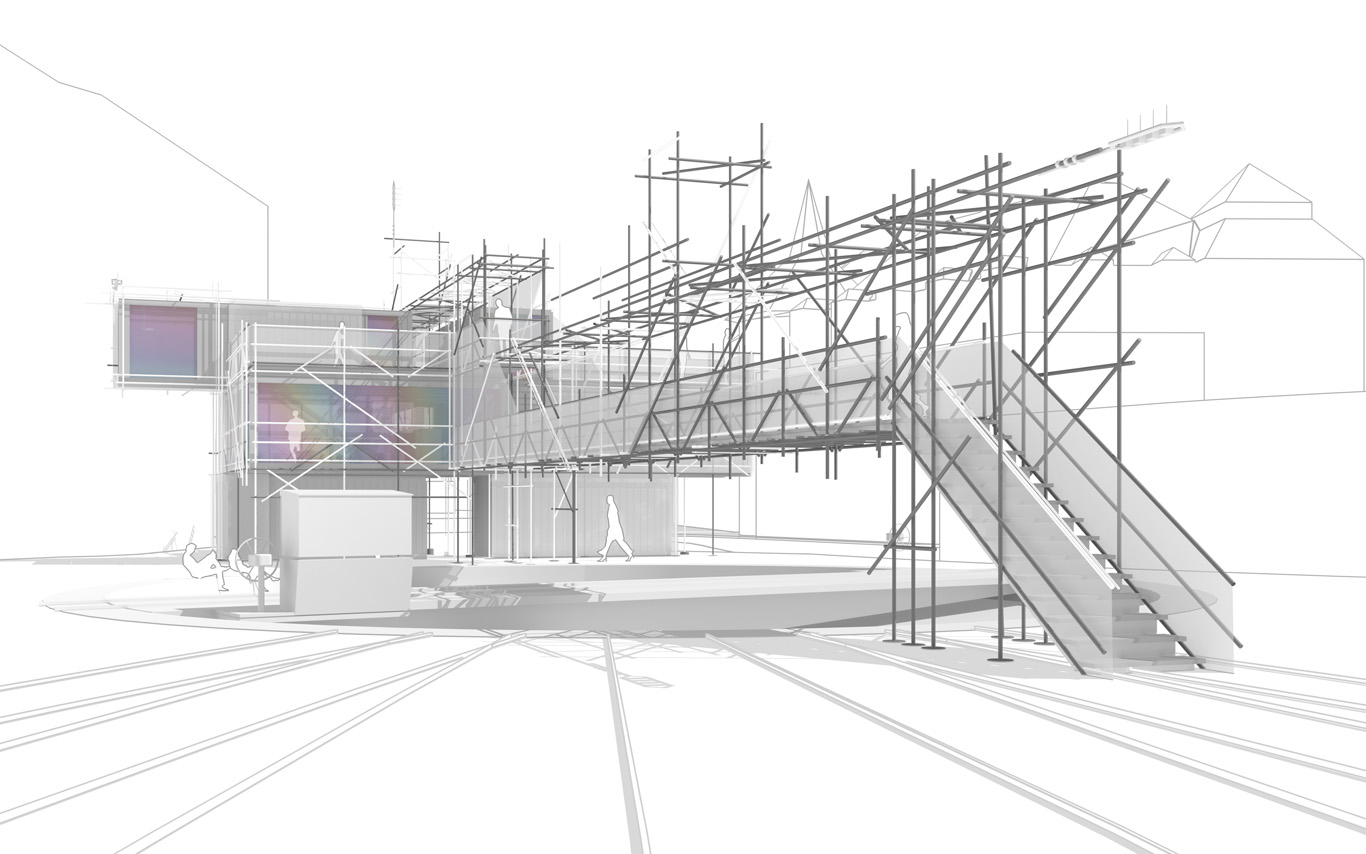

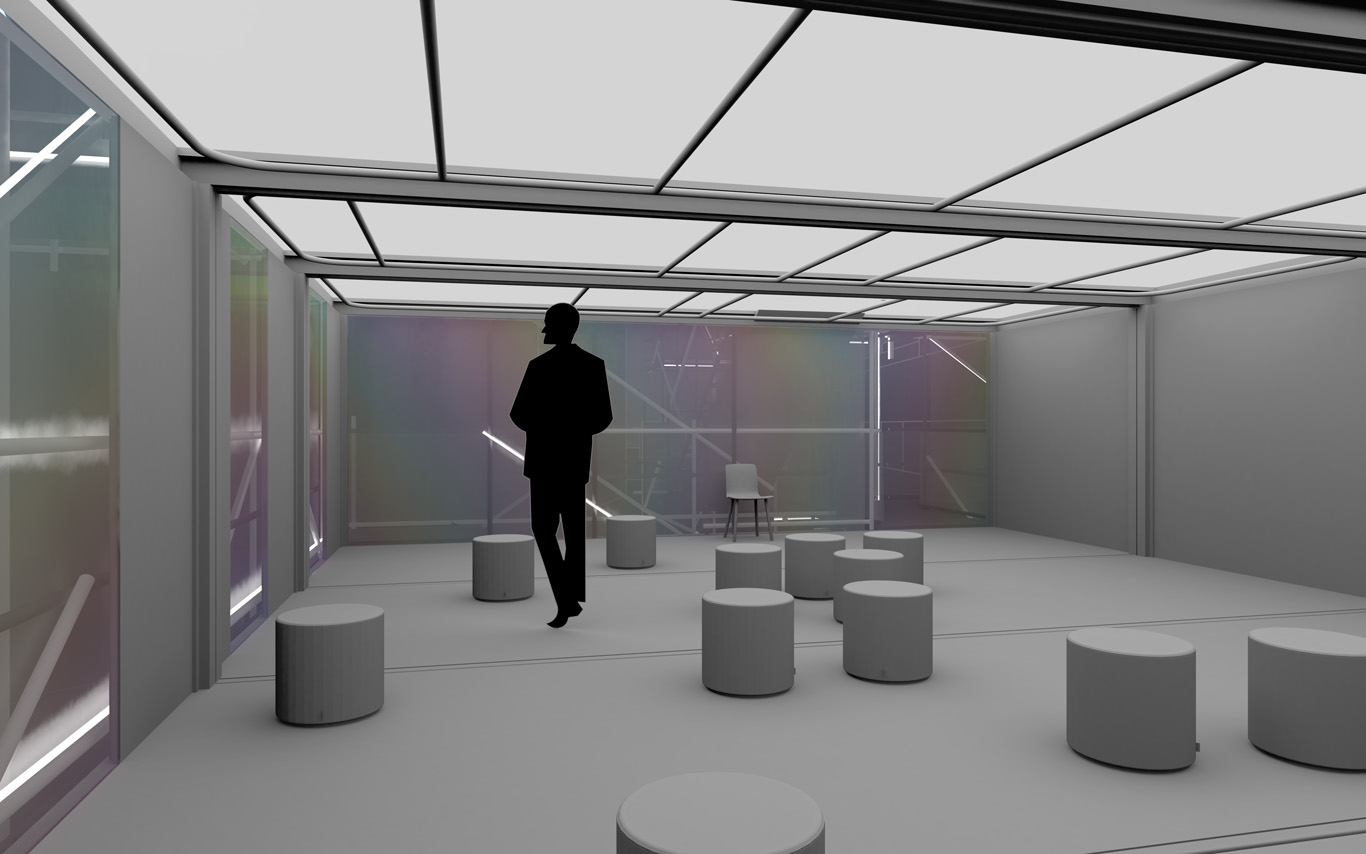

Note: in the continuity of my previous post/documentation concerning the project Platform of Future-Past (fabric | ch's recent winning competition proposal), I publish additional images (several) and explanations about the second phase of the Platform project, for which we were mandated by Canton de Vaud (SiPAL).

The first part of this article gives complementary explanations about the project, but I also take the opportunity to post related works and researches we've done in parallel about particular implications of the platform proposal. This will hopefully bring a neater understanding to the way we try to combine experimentations-exhibitions, the creation of "tools" and the design of larger proposals in our open and process of work.

Notably, these related works concerned the approach to data, the breaking of the environment into computable elements and the inevitable questions raised by their uses as part of a public architecture project.

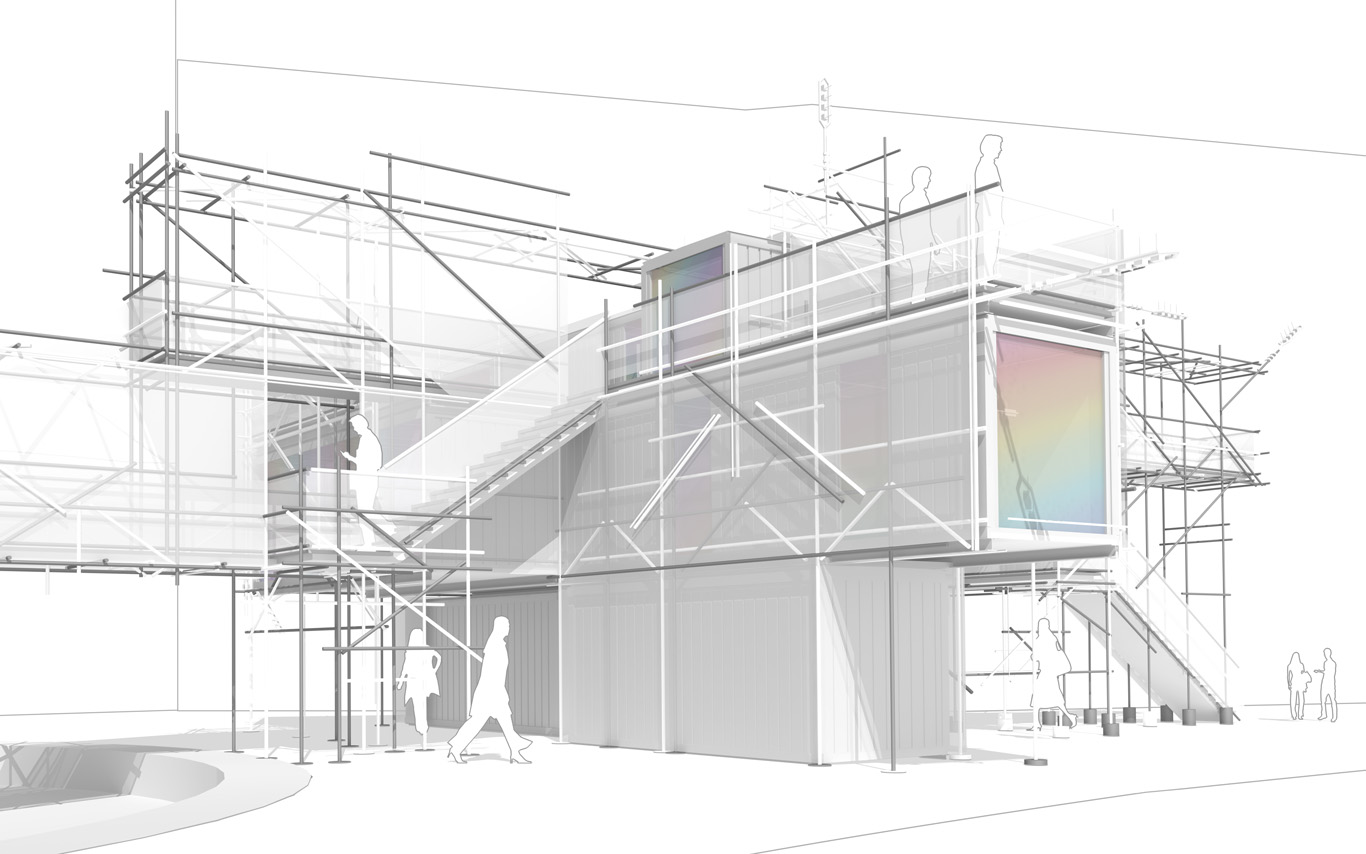

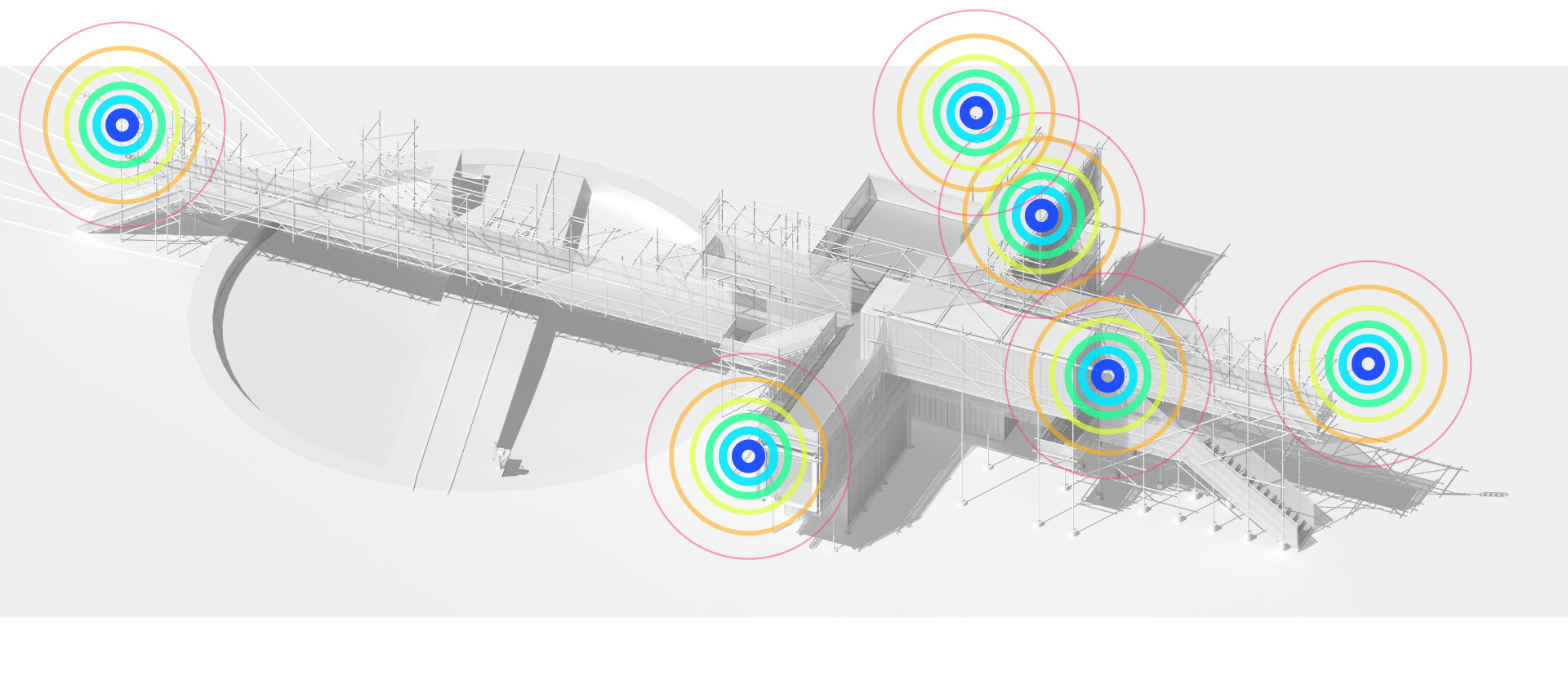

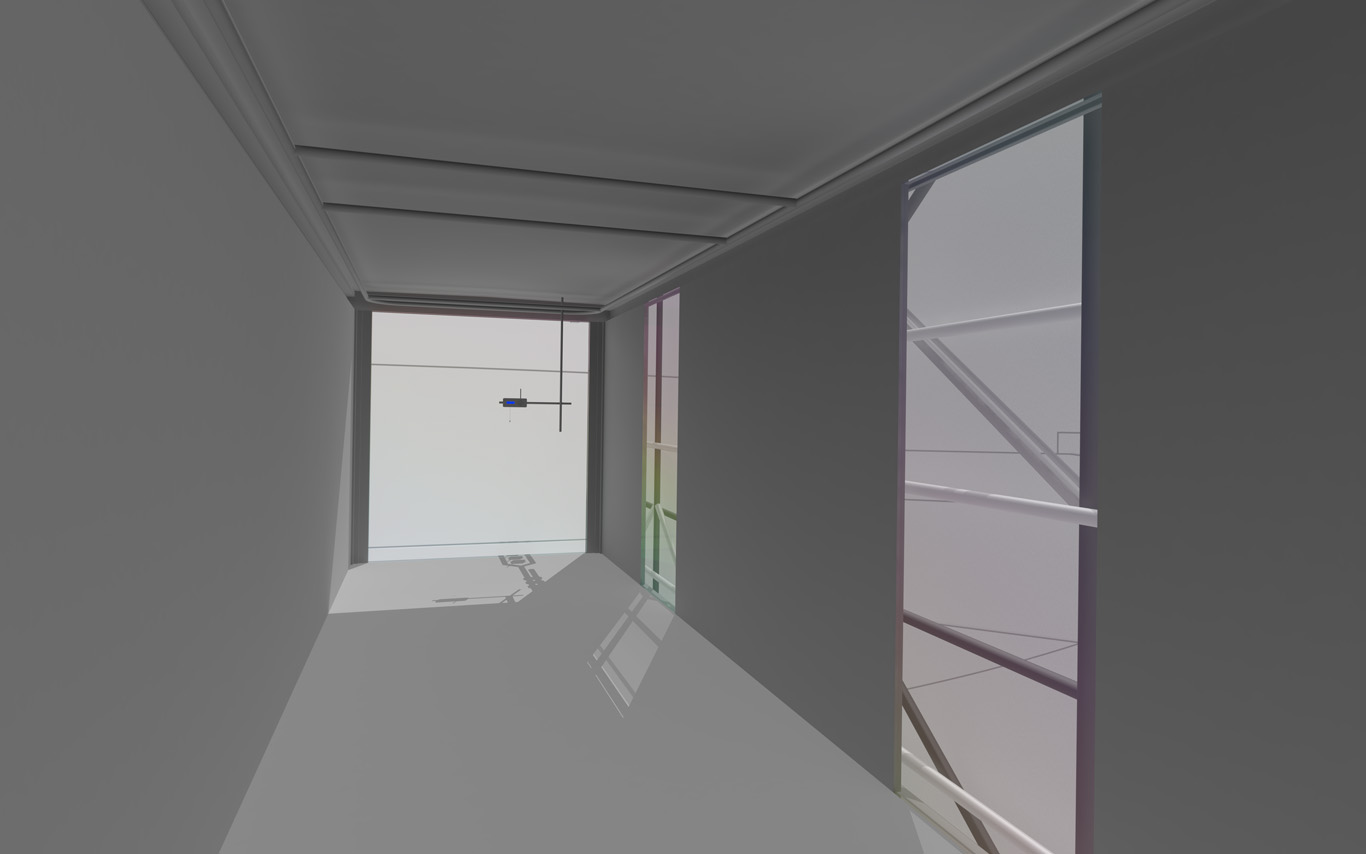

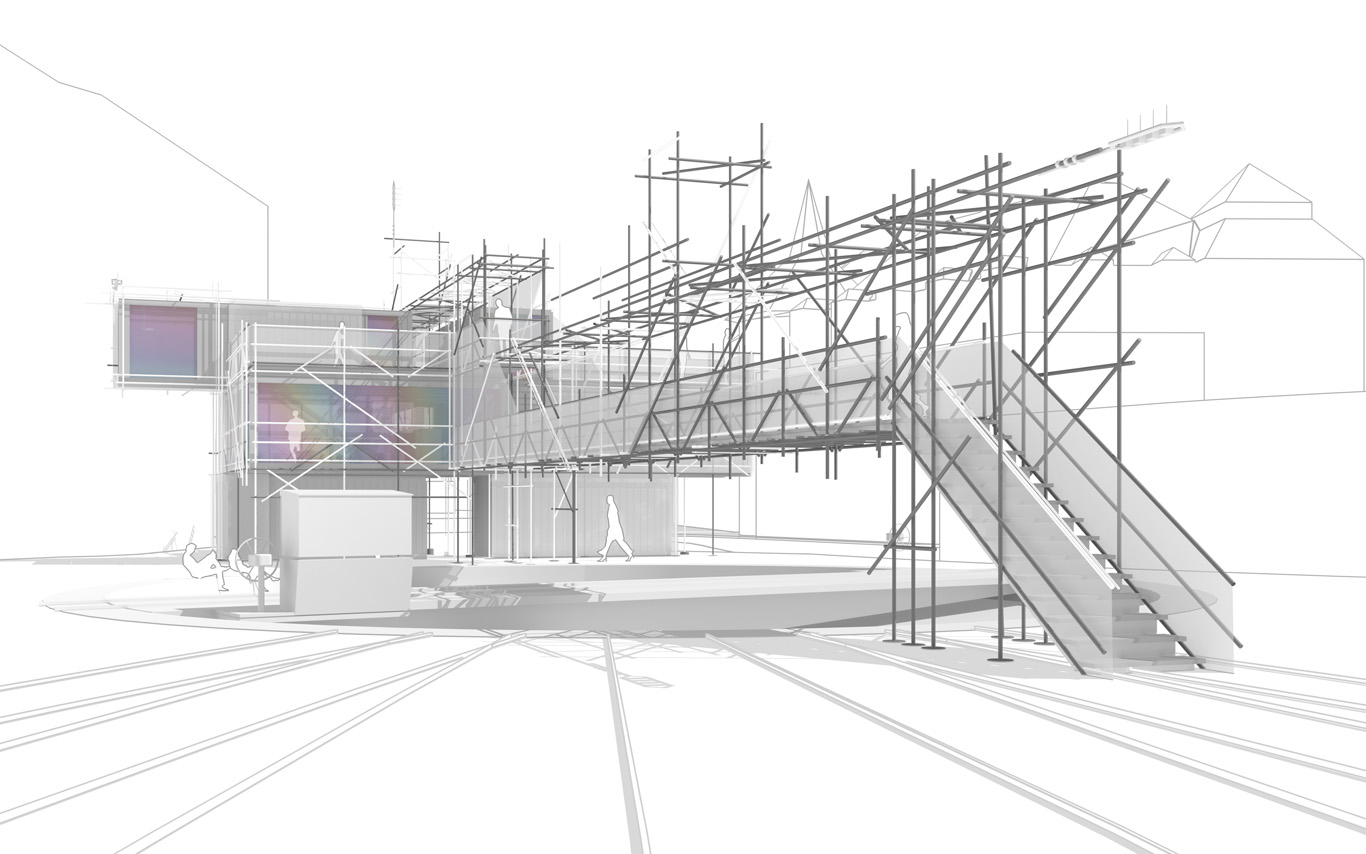

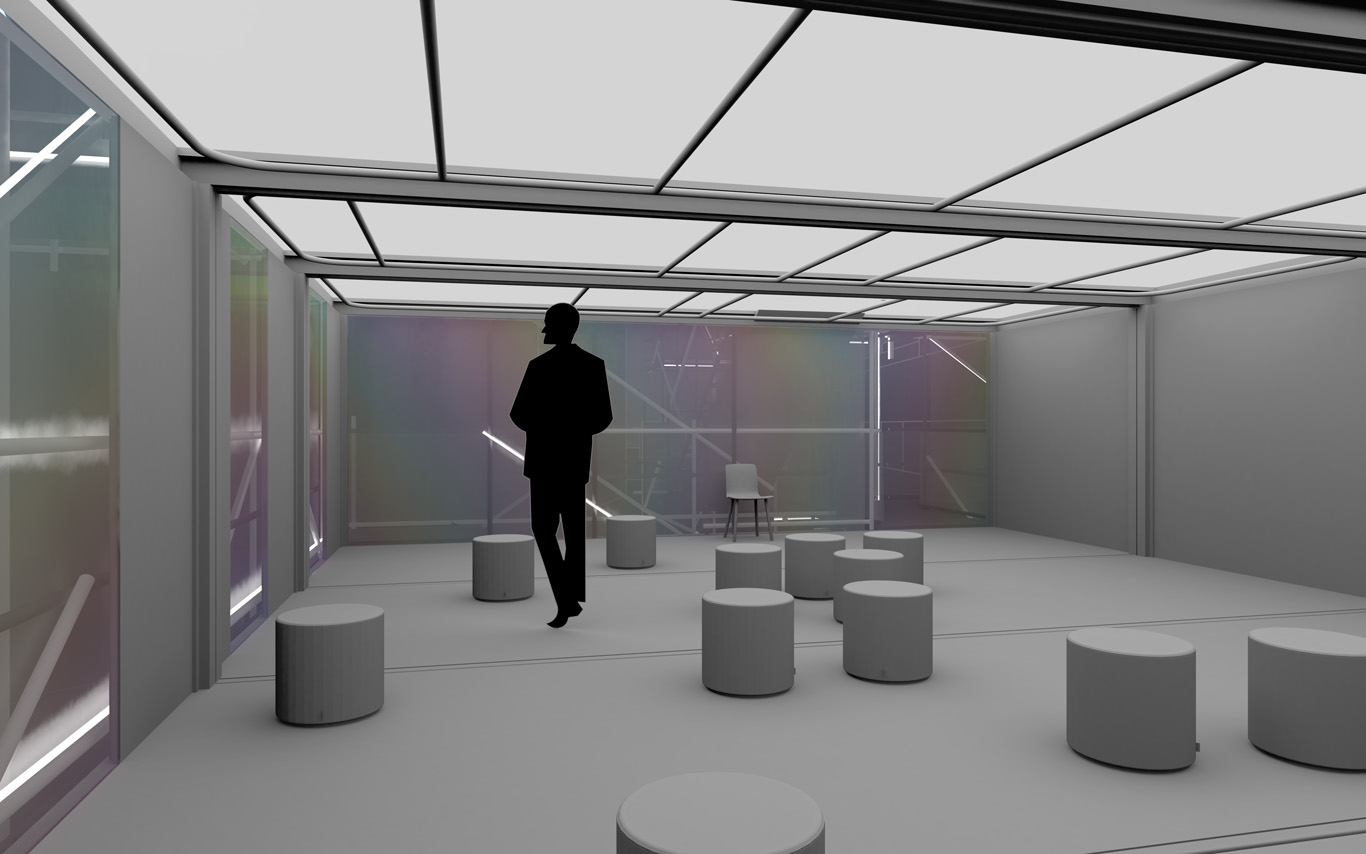

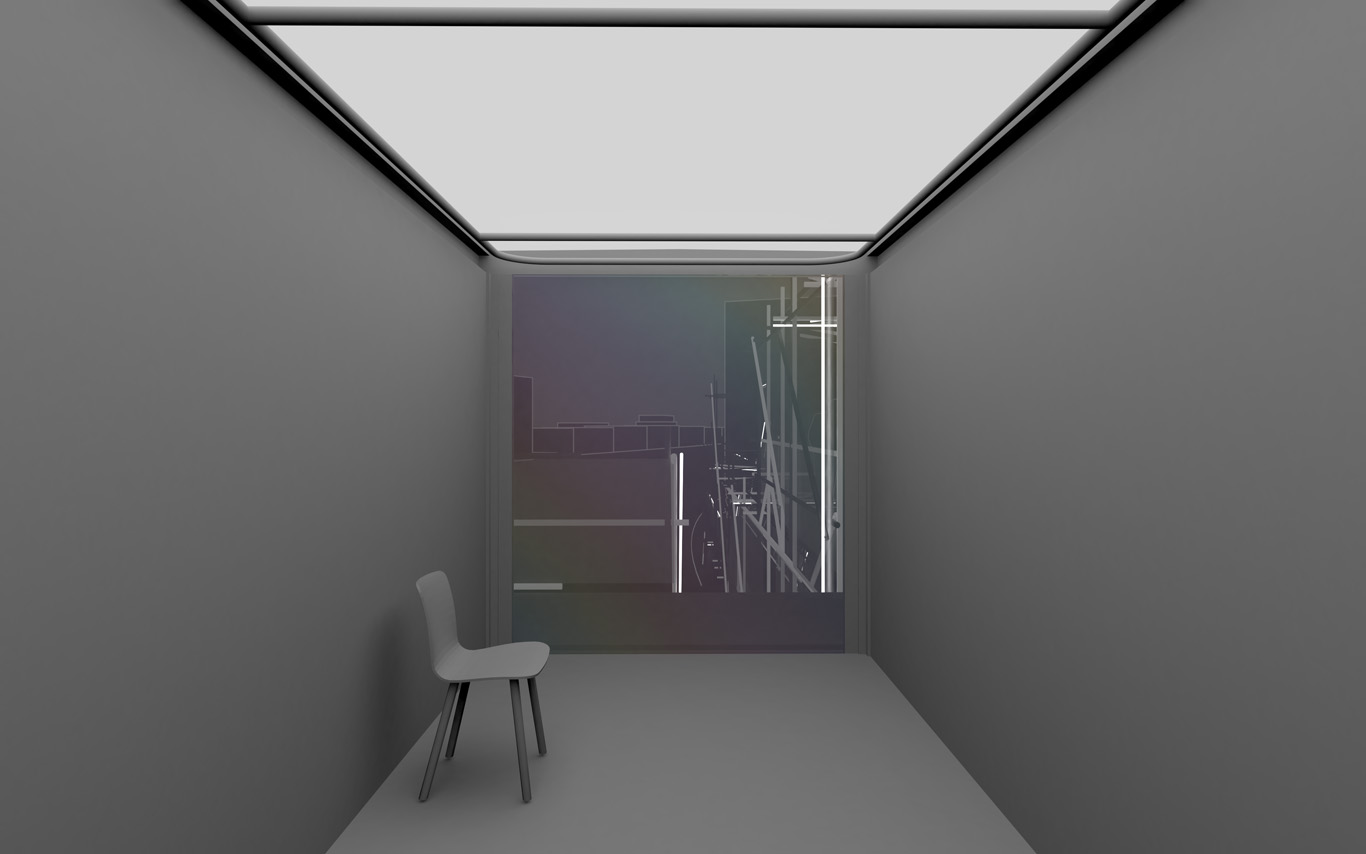

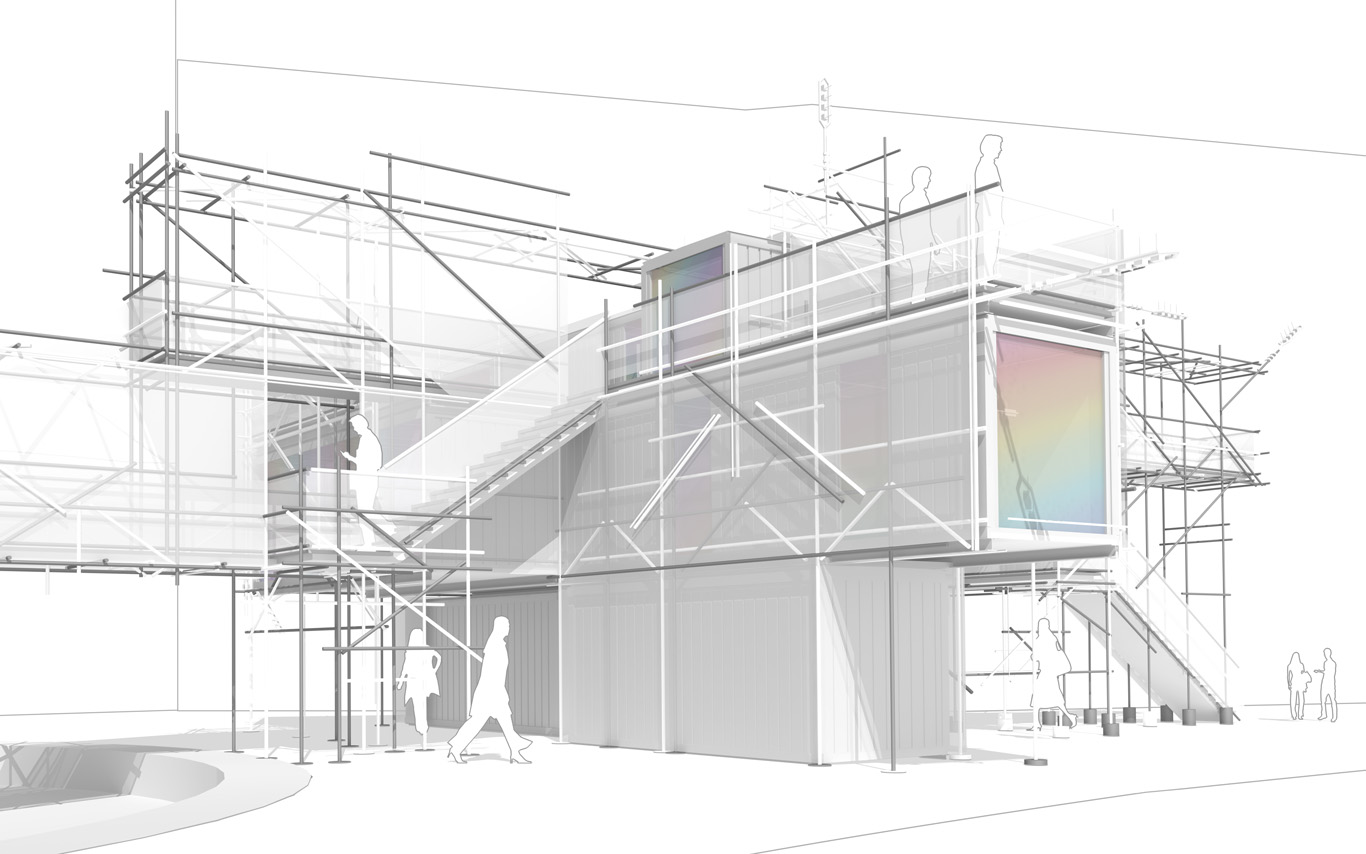

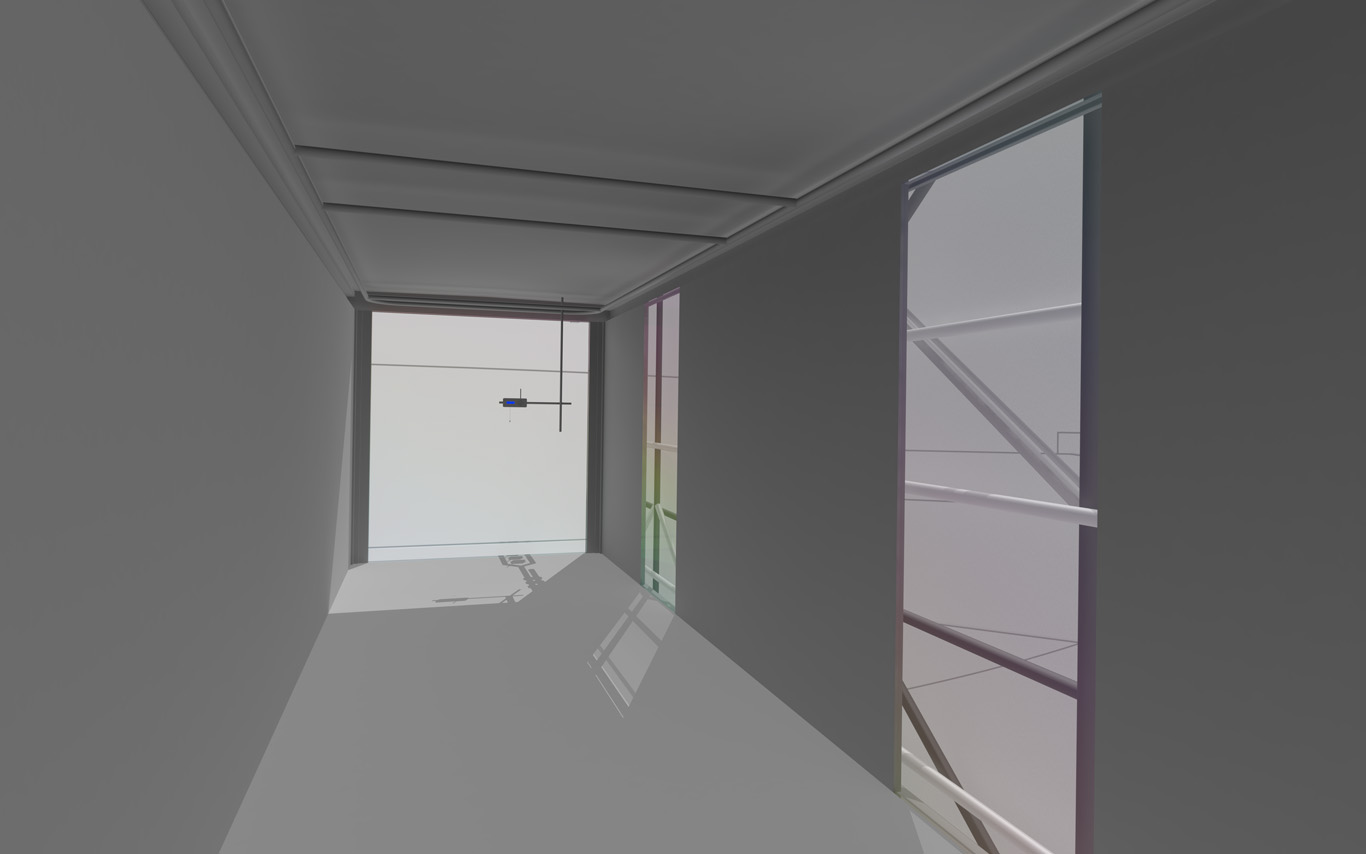

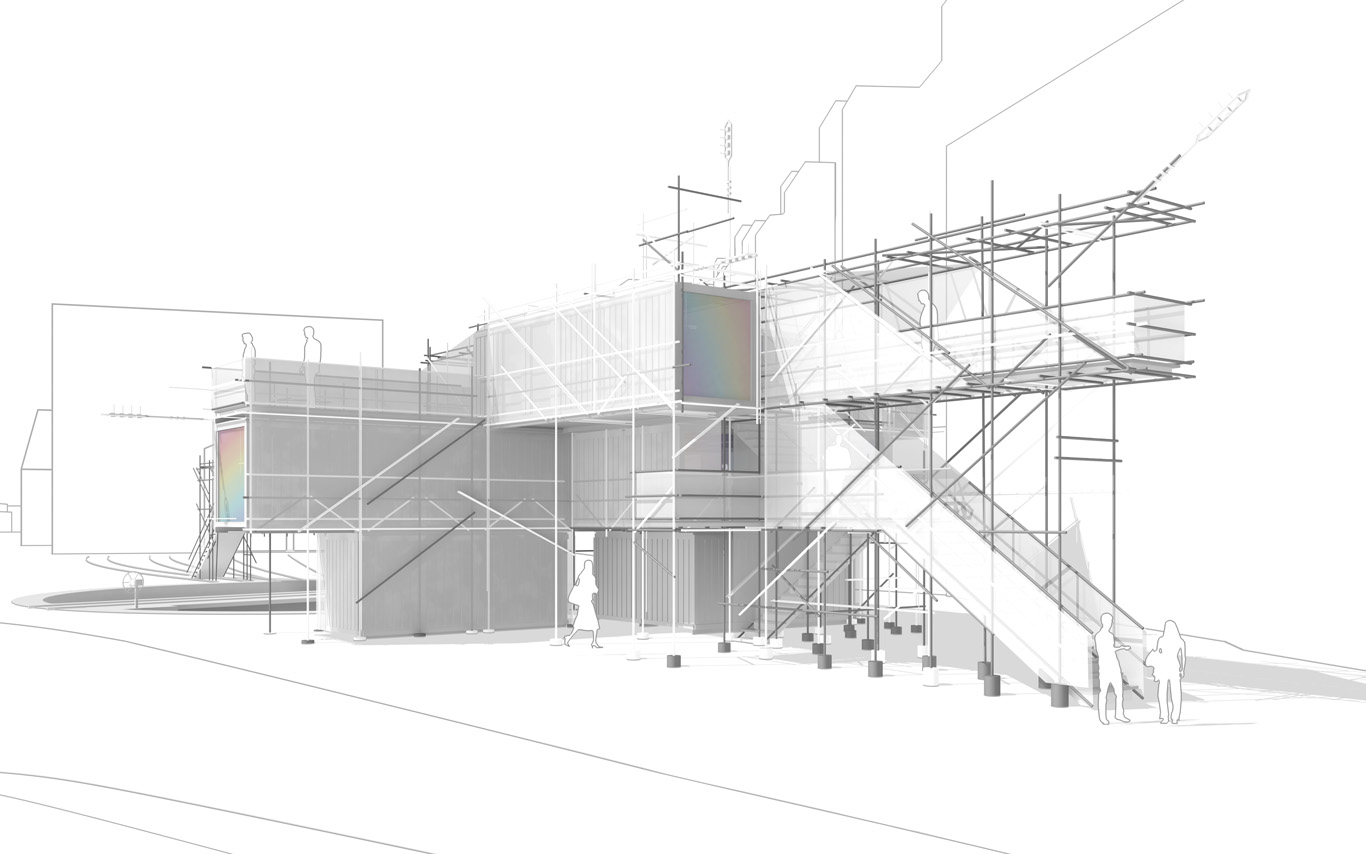

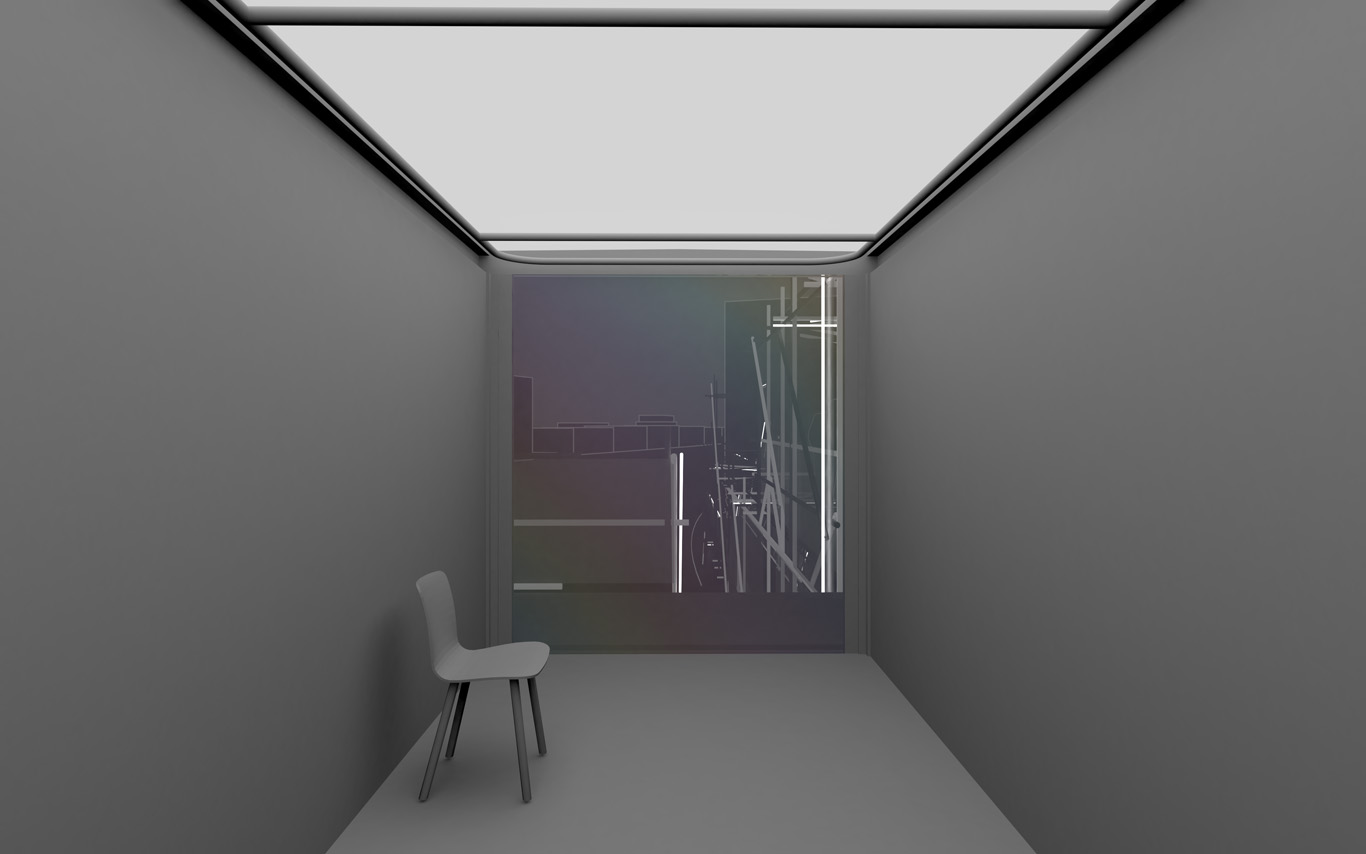

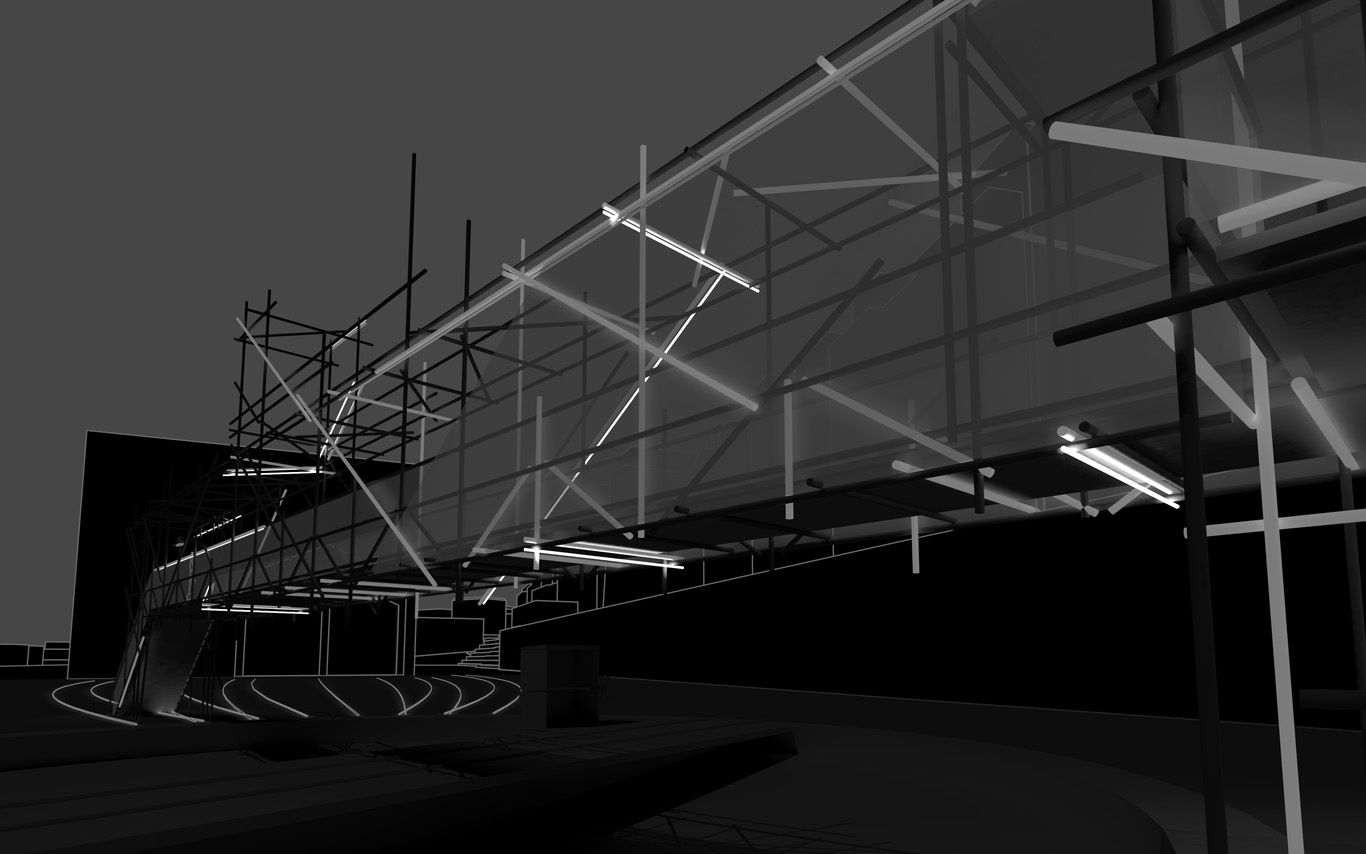

The information pavilion was potentially a slow, analog and digital "shape/experience shifter", as it was planned to be built in several succeeding steps over the years and possibly "reconfigure" to sense and look at its transforming surroundings.

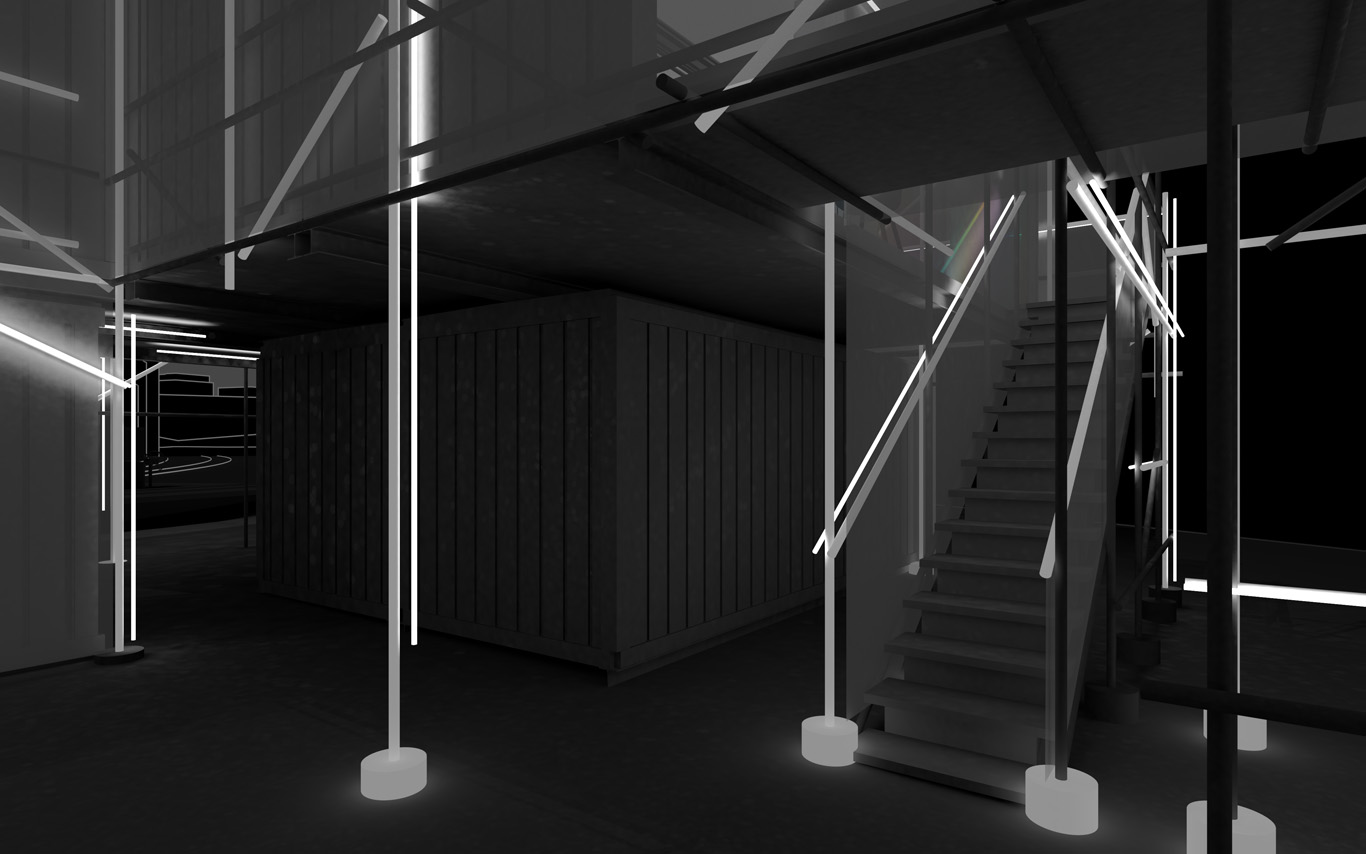

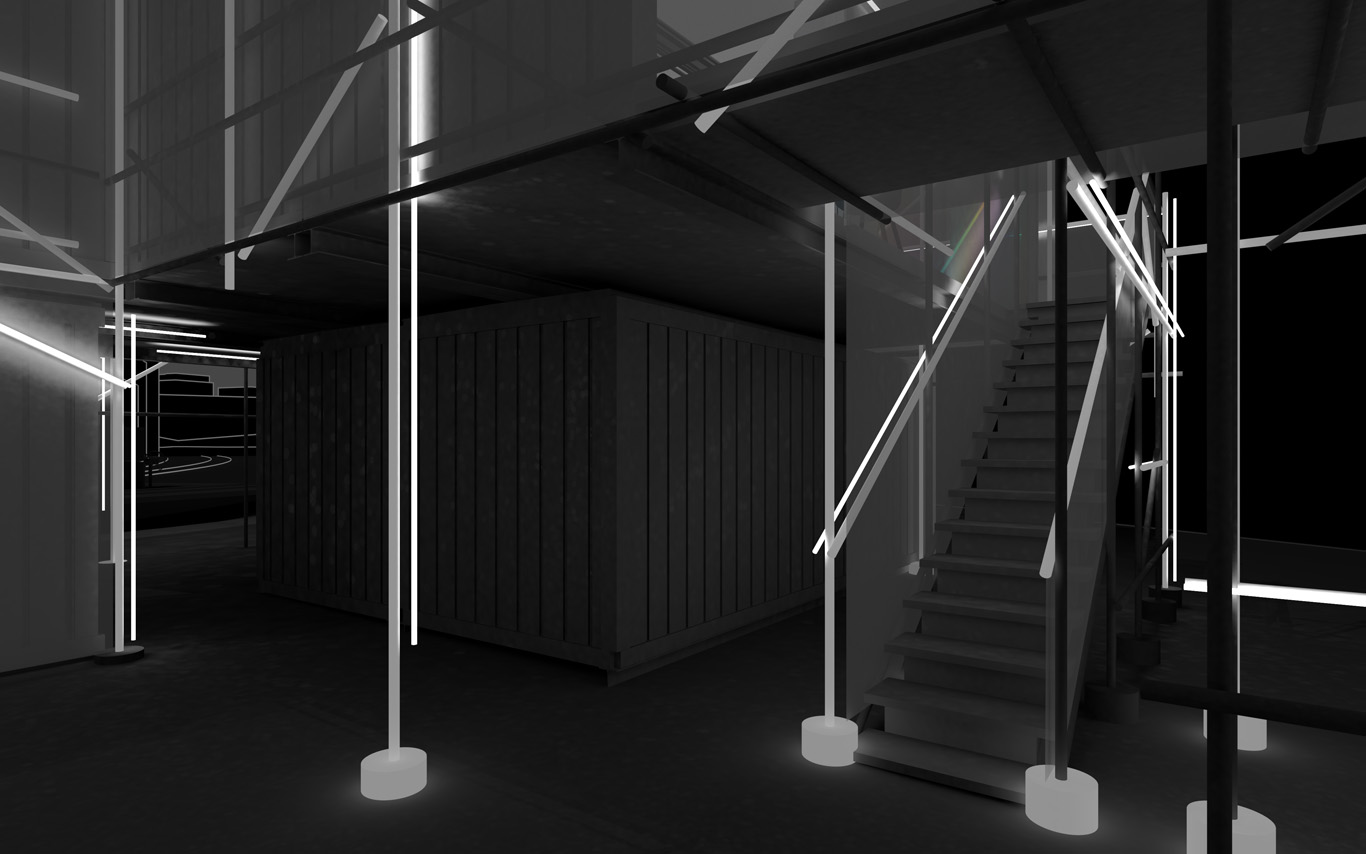

The pavilion conserved therefore an unfinished flavour as part of its DNA, inspired by these old kind of meshed constructions (bamboo scaffoldings), almost sketched. This principle of construction was used to help "shift" if/when necessary.

In a general sense, the pavilion answered the conventional public program of an observation deck about a construction site. It also served the purpose of documenting the ongoing building process that often comes along. By doing so, we turned the "monitoring dimension" (production of data) of such a program into a base element of our proposal. That's where a former experimental installation helped us: Heterochrony.

As it can be noticed, the word "Public" was added to the title of the project between the two phases, to become Public Platform of Future-Past (PPoFP) ... which we believe was important to add. This because it was envisioned that the PPoFP would monitor and use environmental data concerning the direct surroundings of the information pavilion (but NO DATA about uses/users). Data that we stated in this case Public, while the treatment of the monitored data would also become part of the project, "architectural" (more below about it).

For these monitored data to stay public, so as for the space of the pavilion itself that would be part of the public domain and physically extends it, we had to ensure that these data wouldn't be used by a third party private service. We were in need to keep an eye on the algorithms that would treat the spatial data. Or best, write them according to our design goals (more about it below).

That's were architecture meets code and data (again) obviously...

By fabric | ch

-----

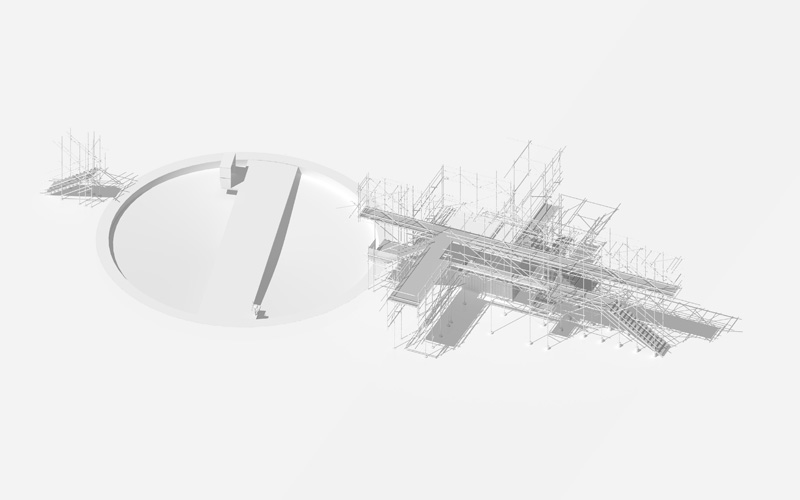

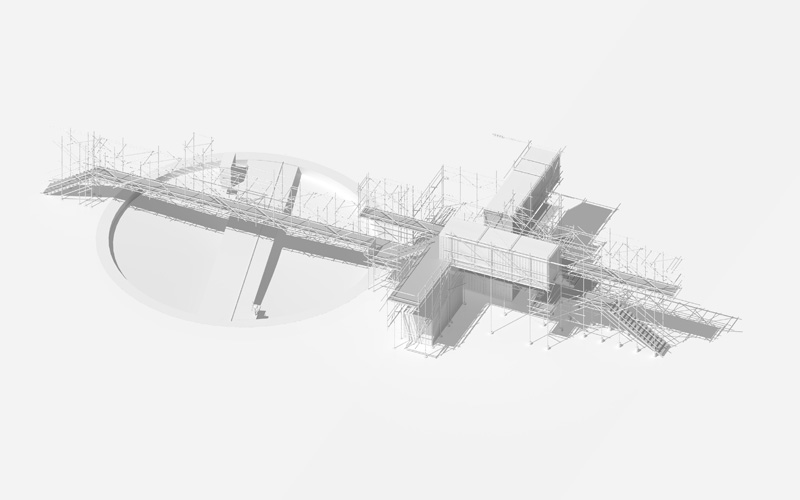

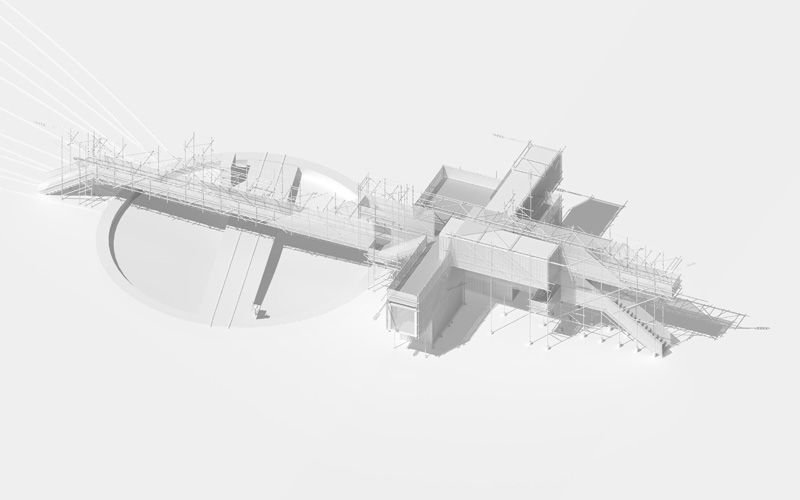

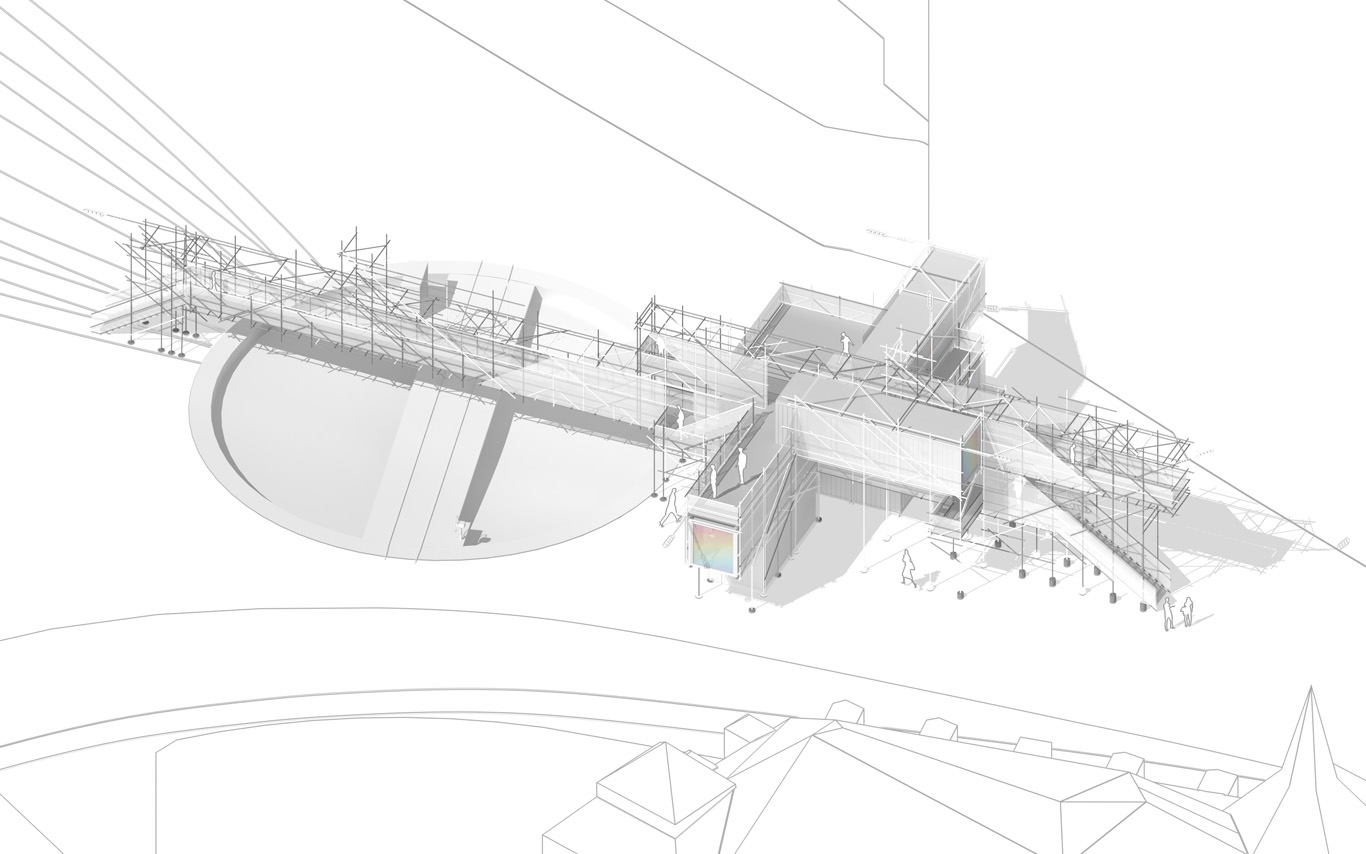

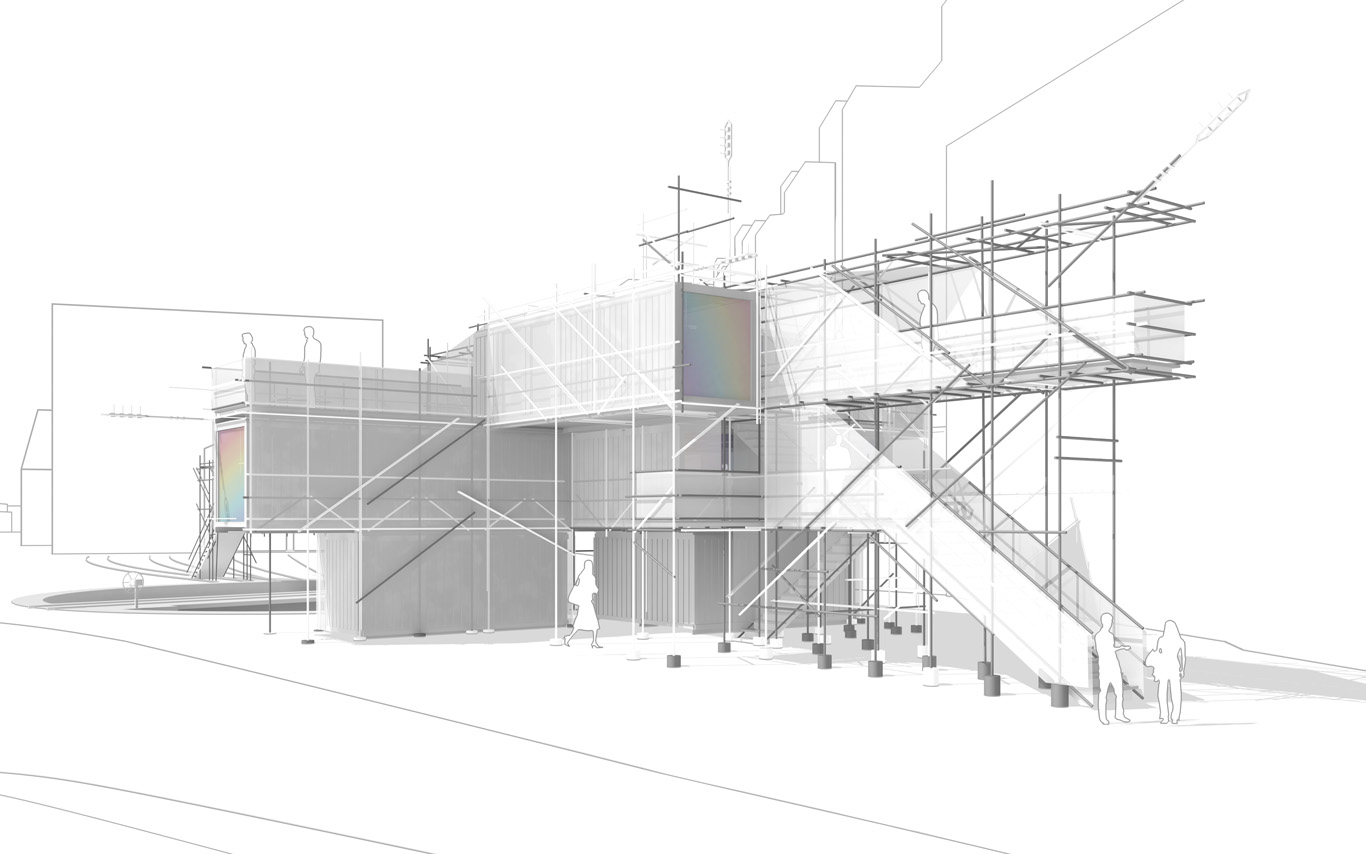

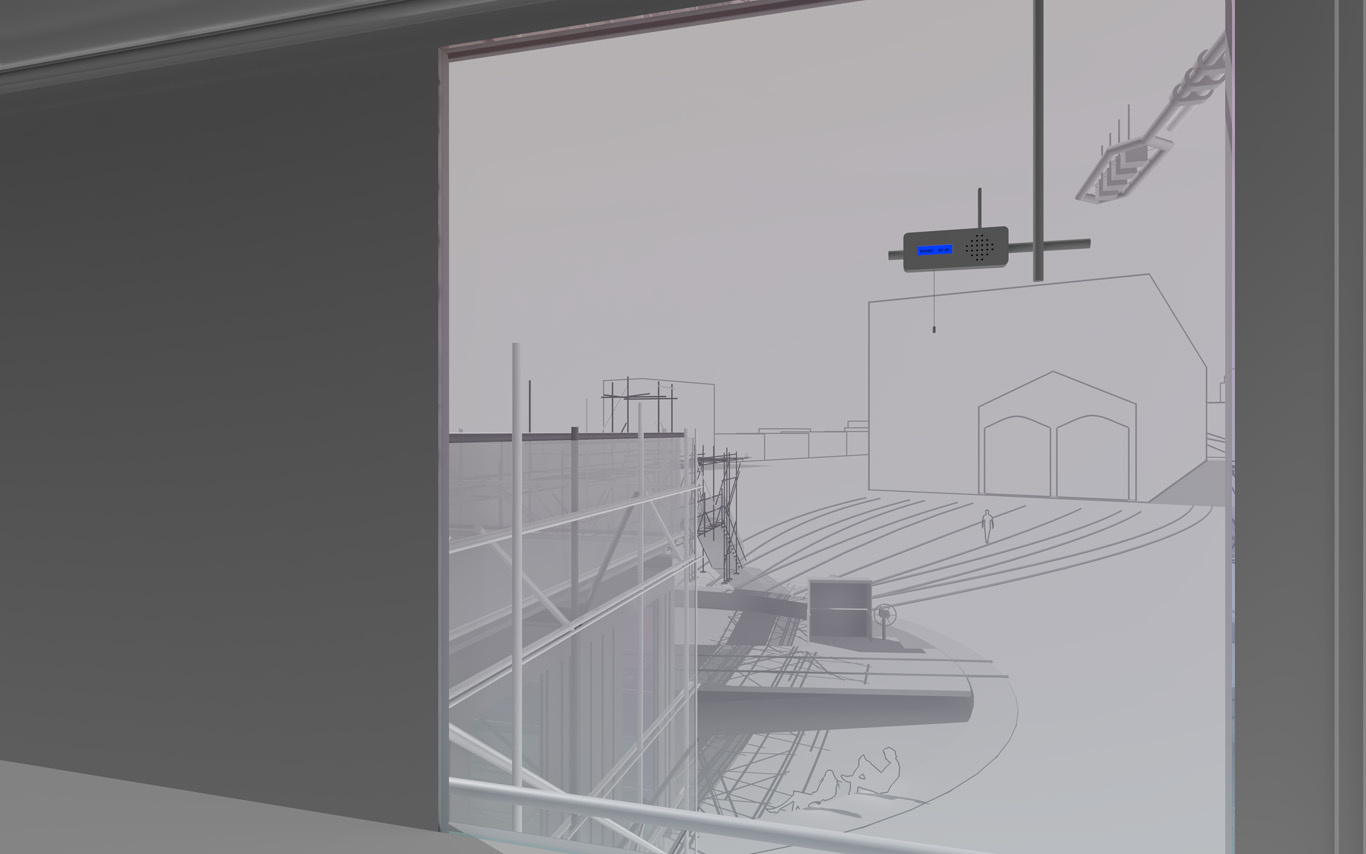

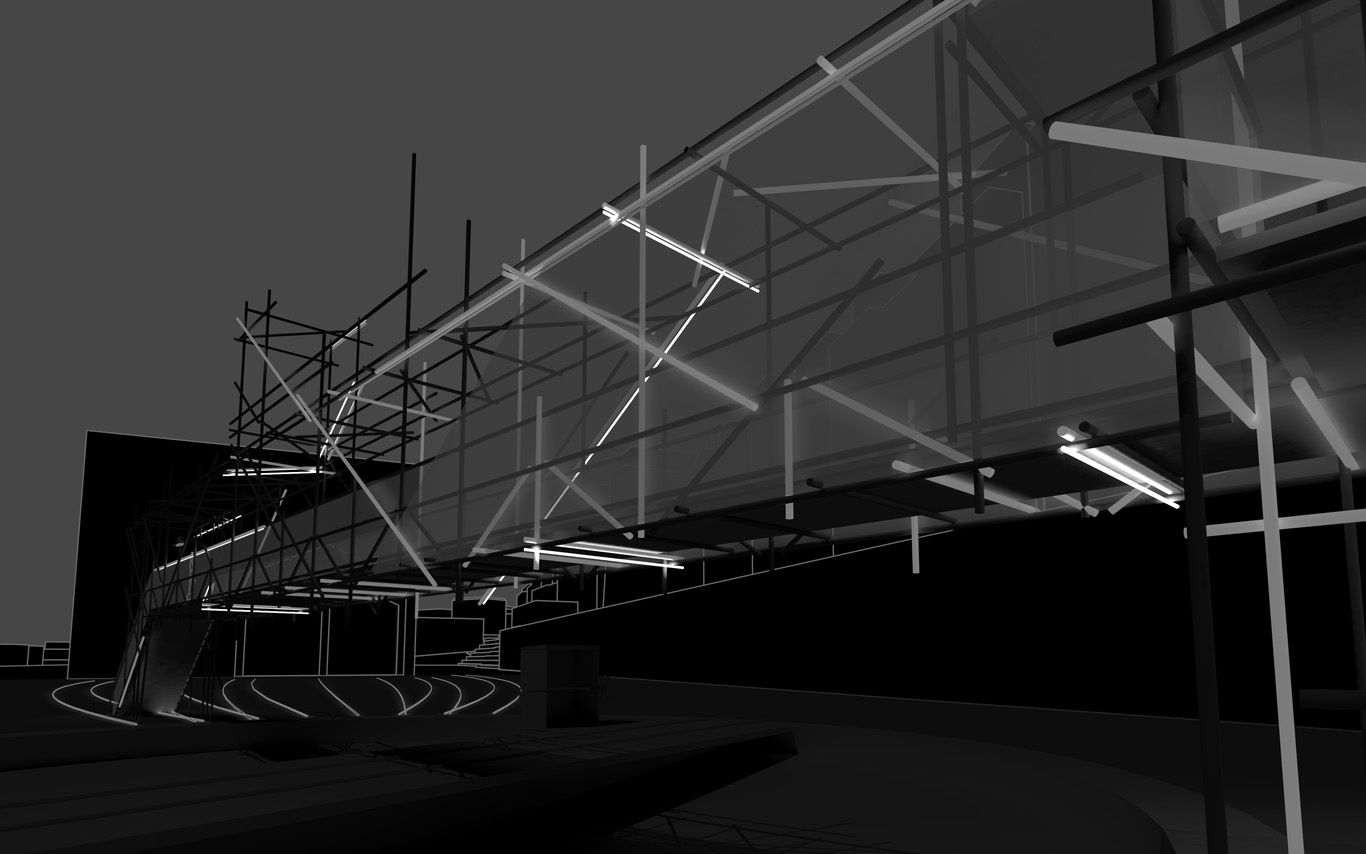

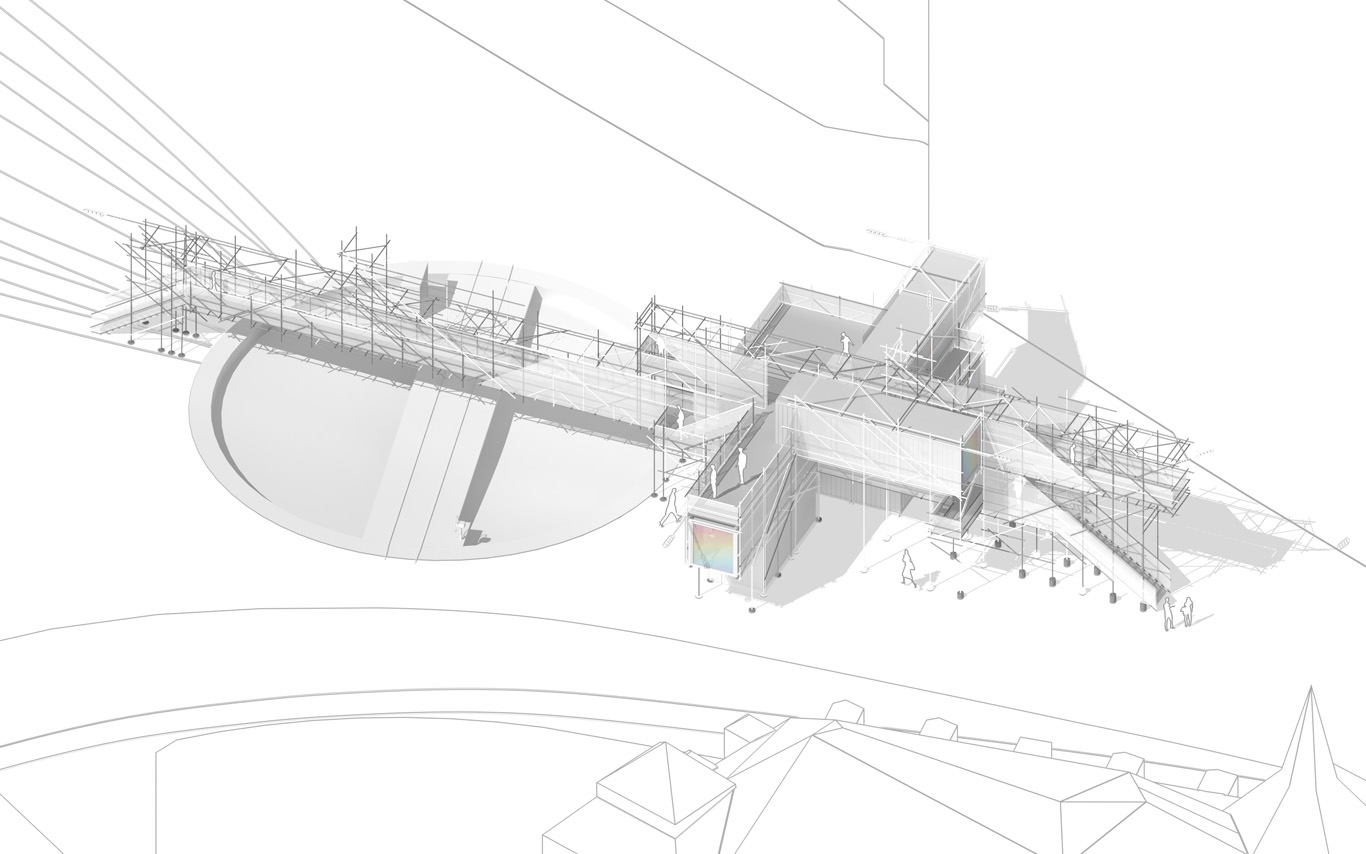

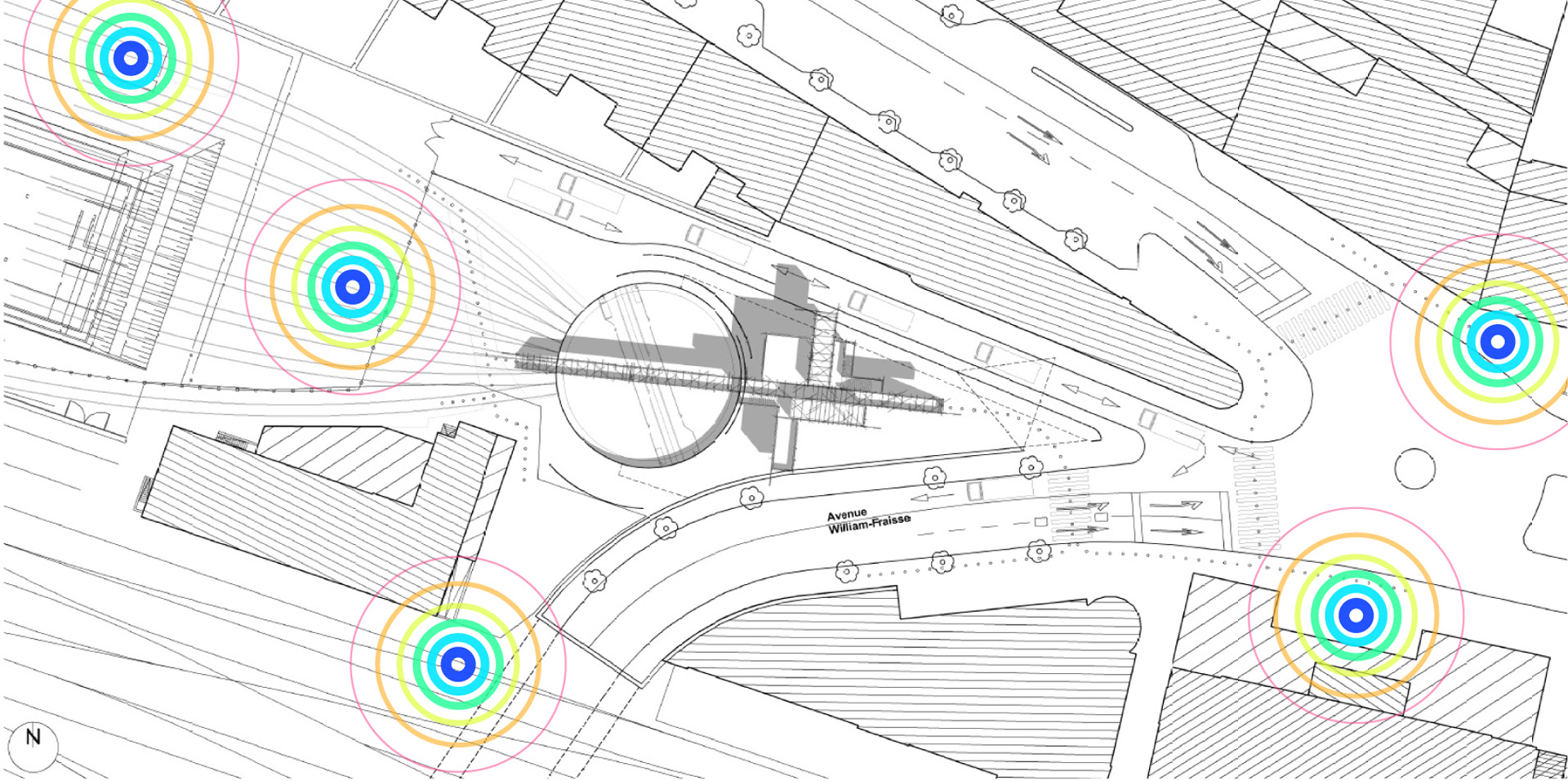

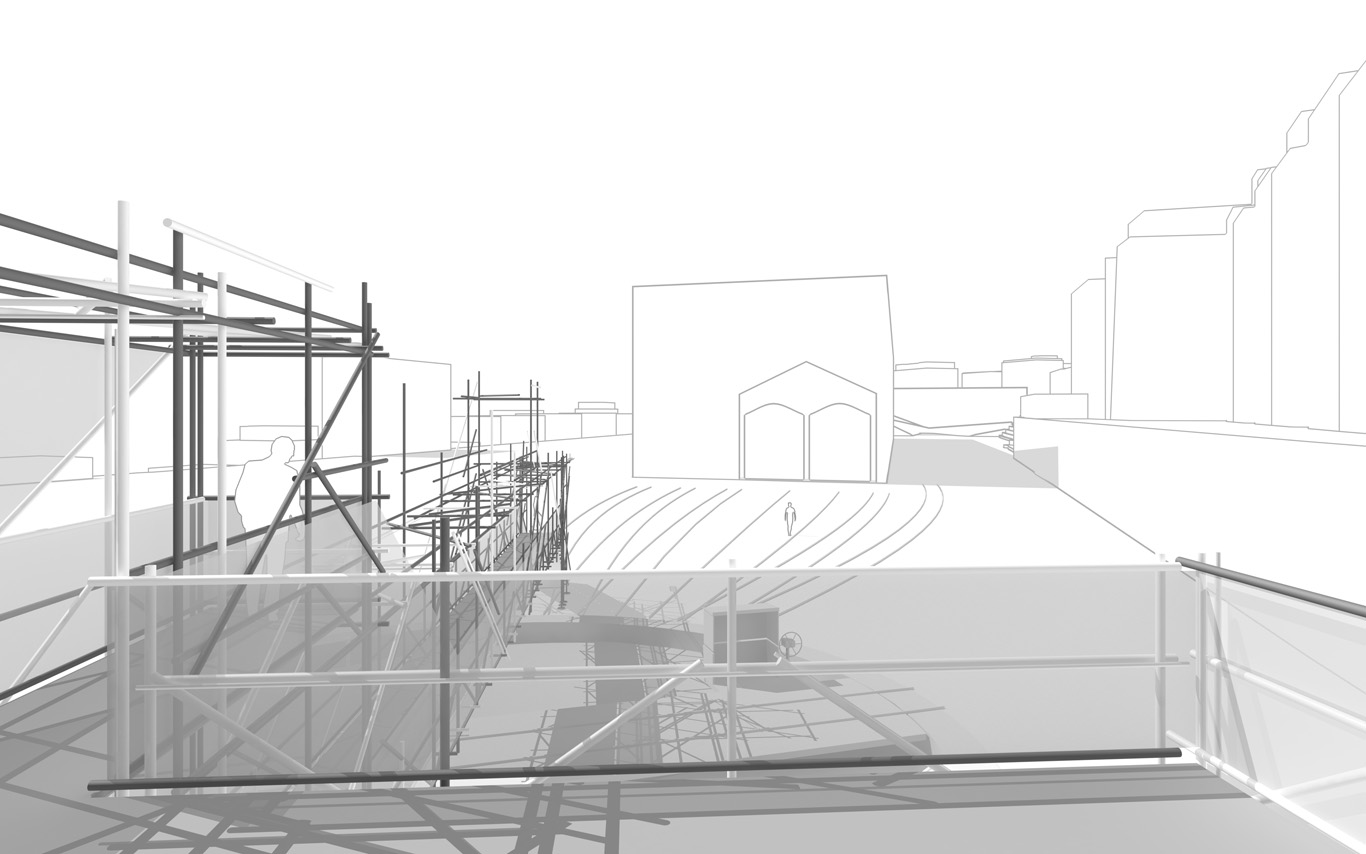

The Public Platform of Future-Past is a structure (an information and sightseeing pavilion), a Platform that overlooks an existing Public site while basically taking it as it is, in a similar way to an archeological platform over an excavation site.

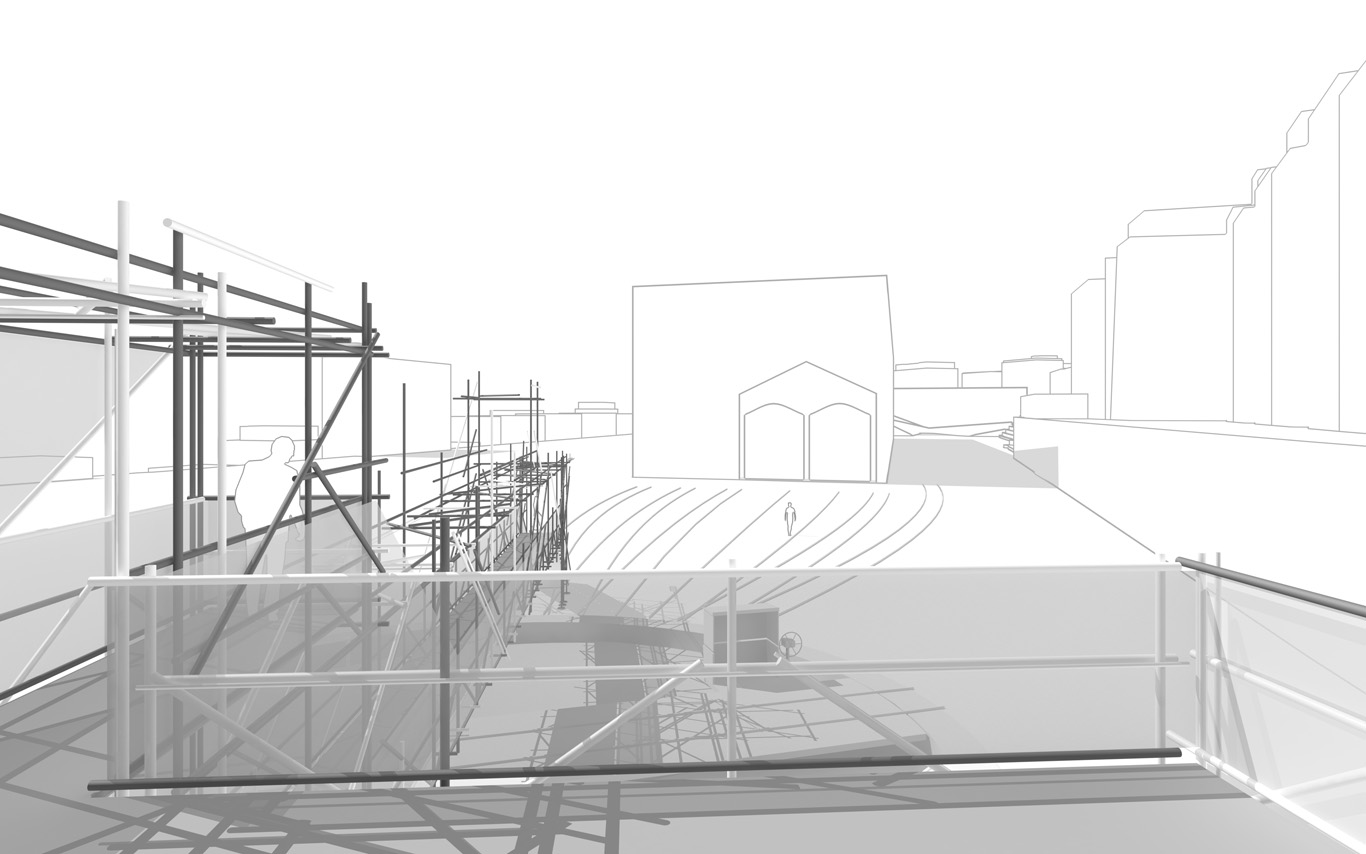

The asphalt ground floor remains virtually untouched, with traces of former uses kept as they are, some quite old (a train platform linked to an early XXth century locomotives hall), some less (painted parking spaces). The surrounding environment will move and change consideralby over the years while new constructions will go on. The pavilion will monitor and document these changes. Therefore the last part of its name: "Future-Past".

By nonetheless touching the site in a few points, the pavilion slightly reorganizes the area and triggers spaces for a small new outdoor cafe and a bikes parking area. This enhanced ground floor program can work by itself, seperated from the upper floors.

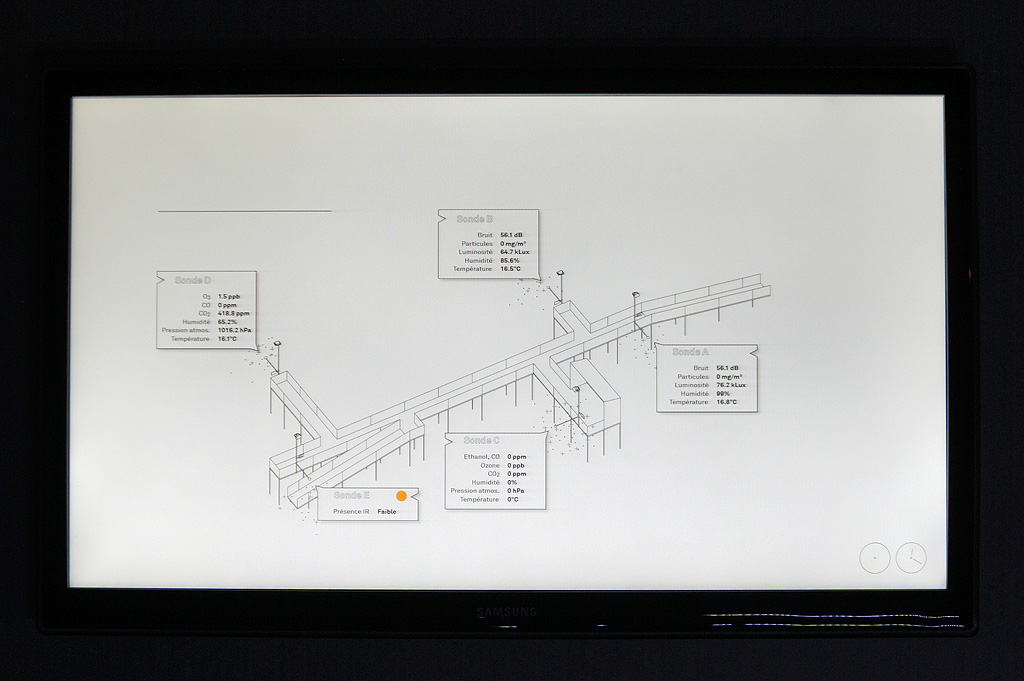

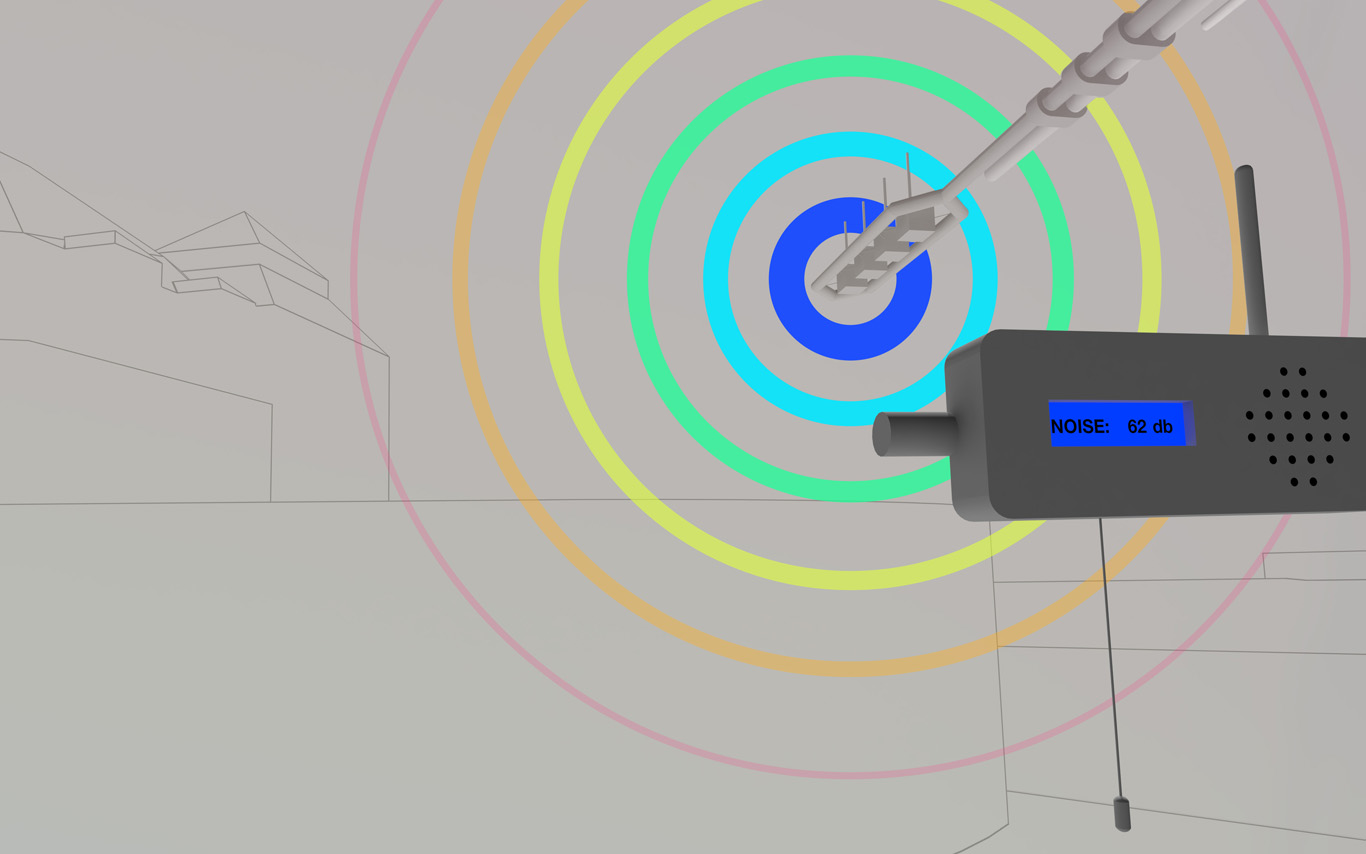

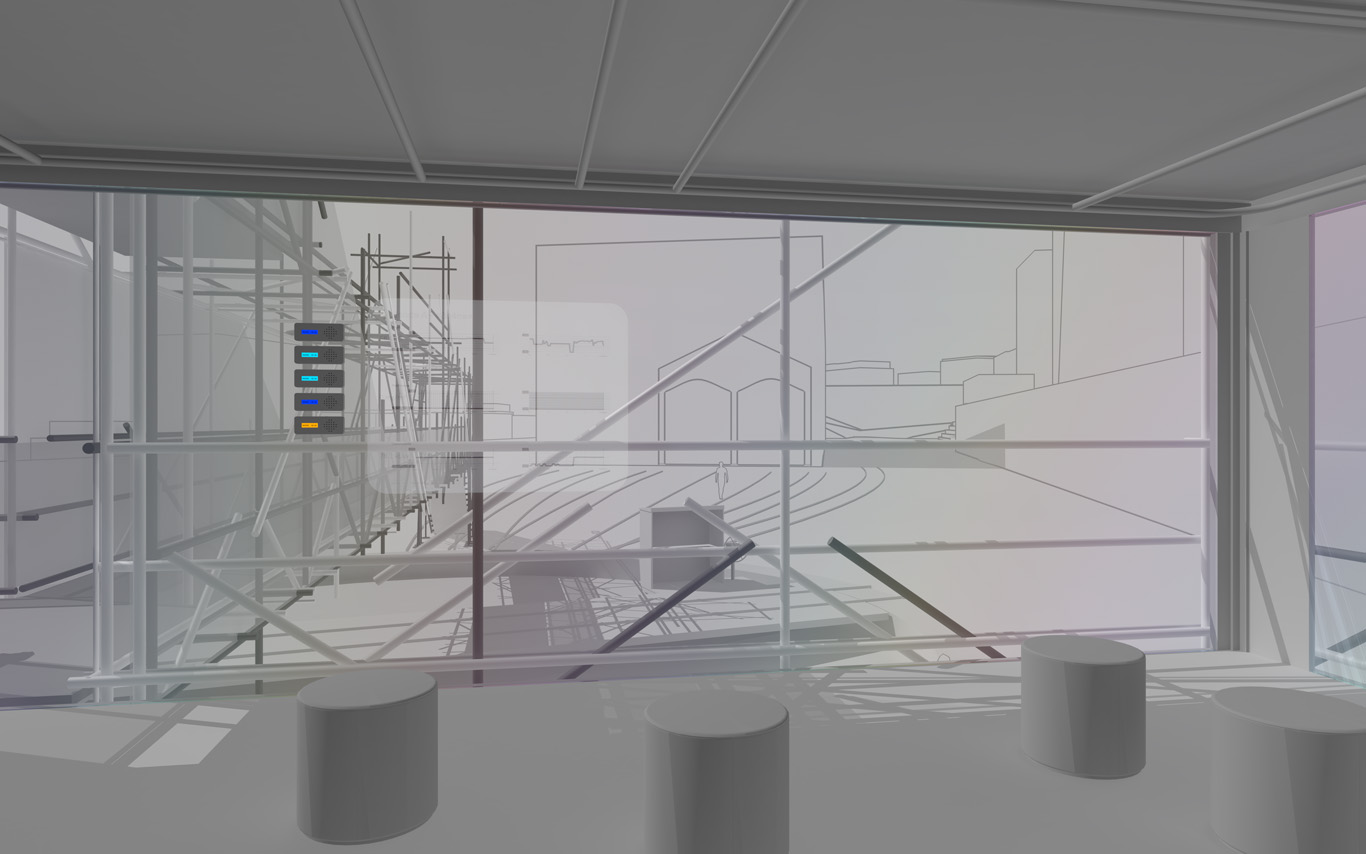

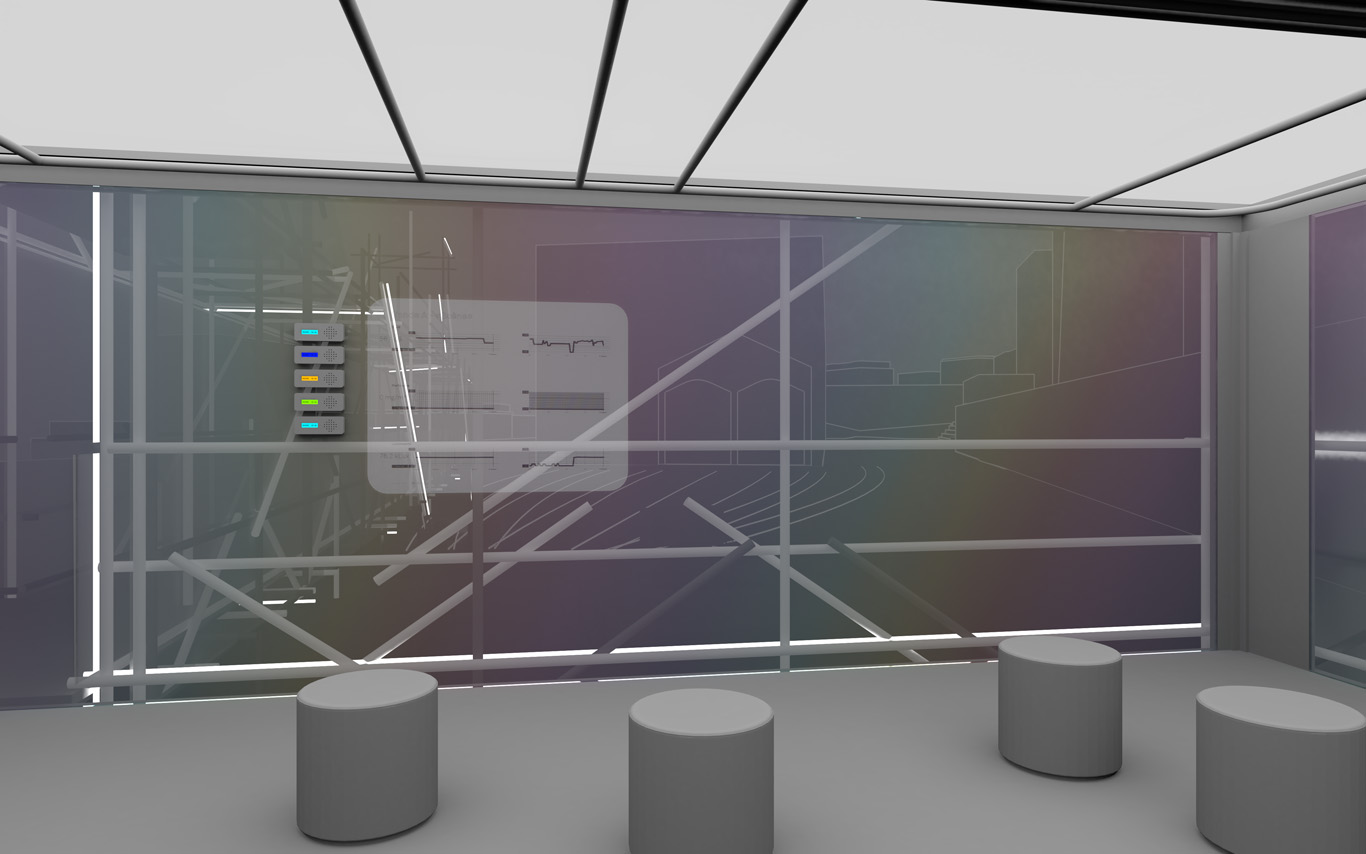

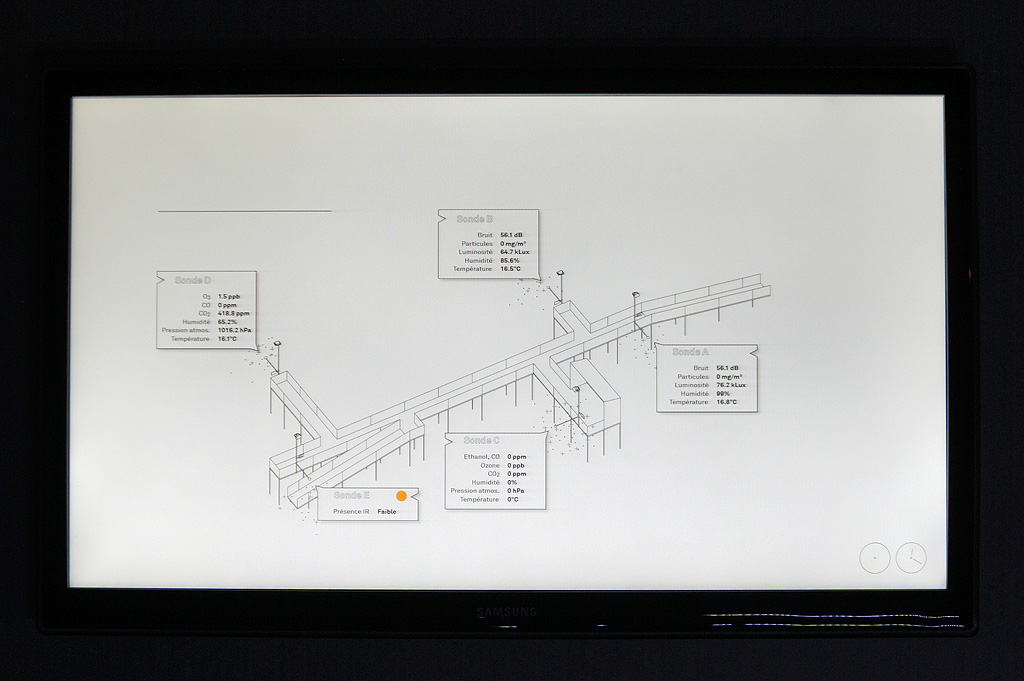

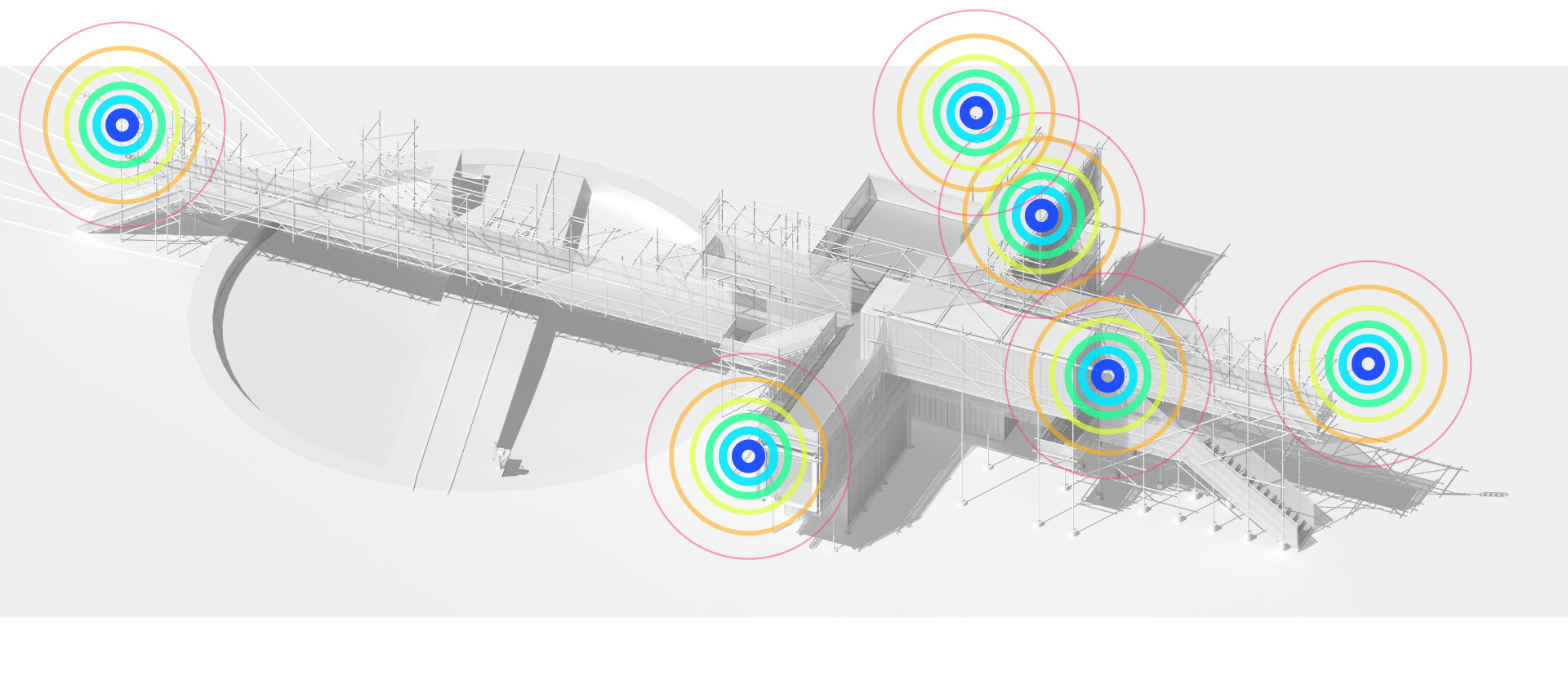

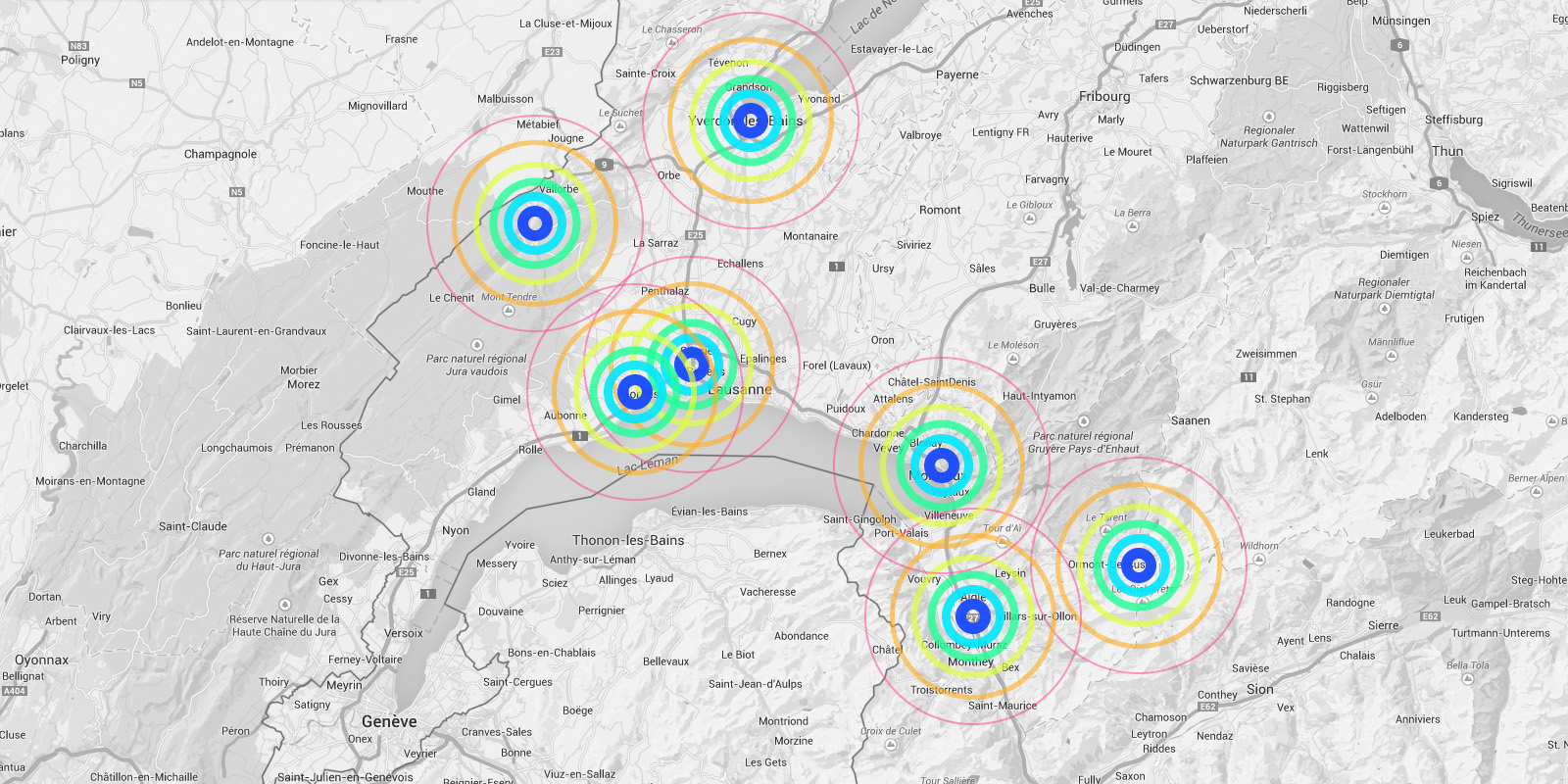

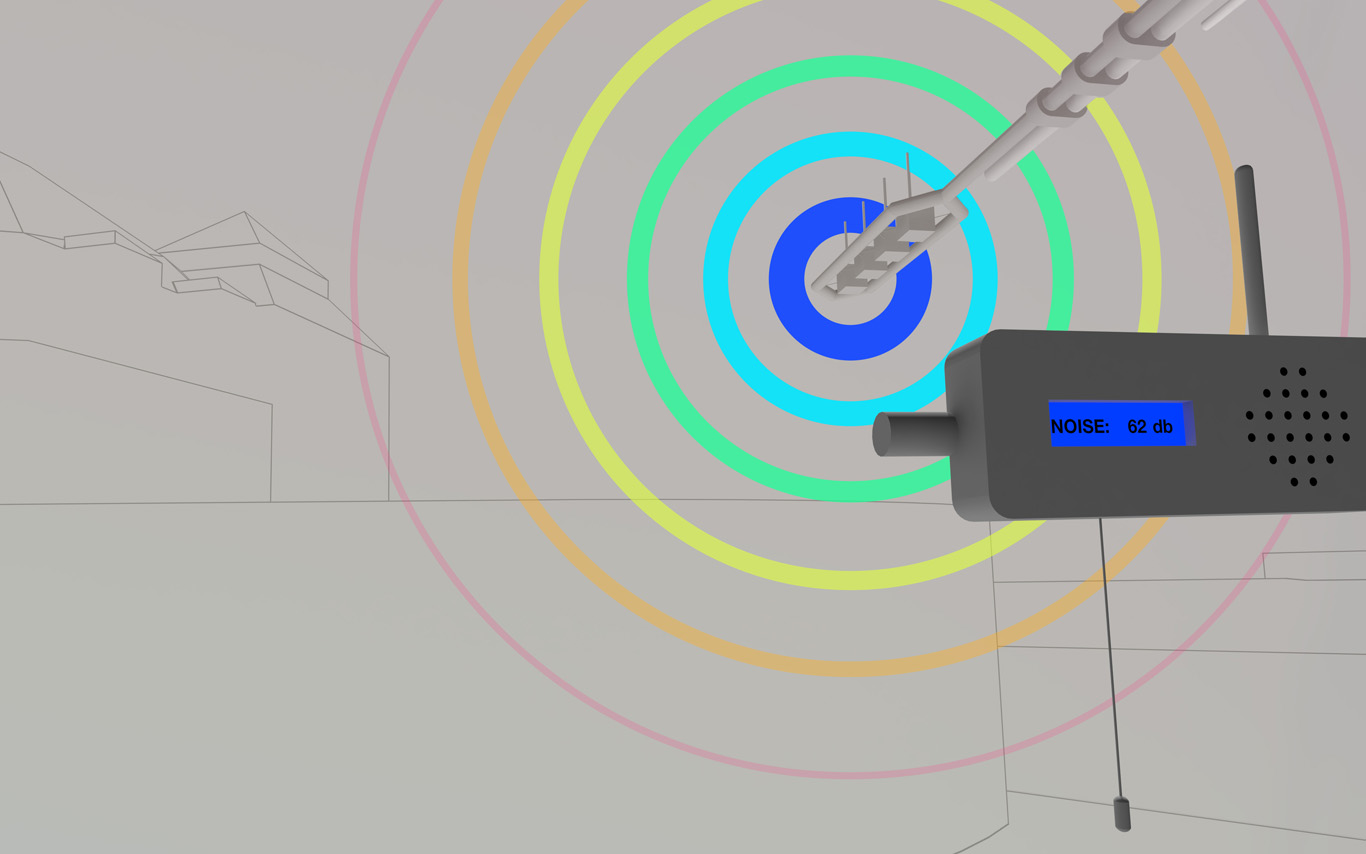

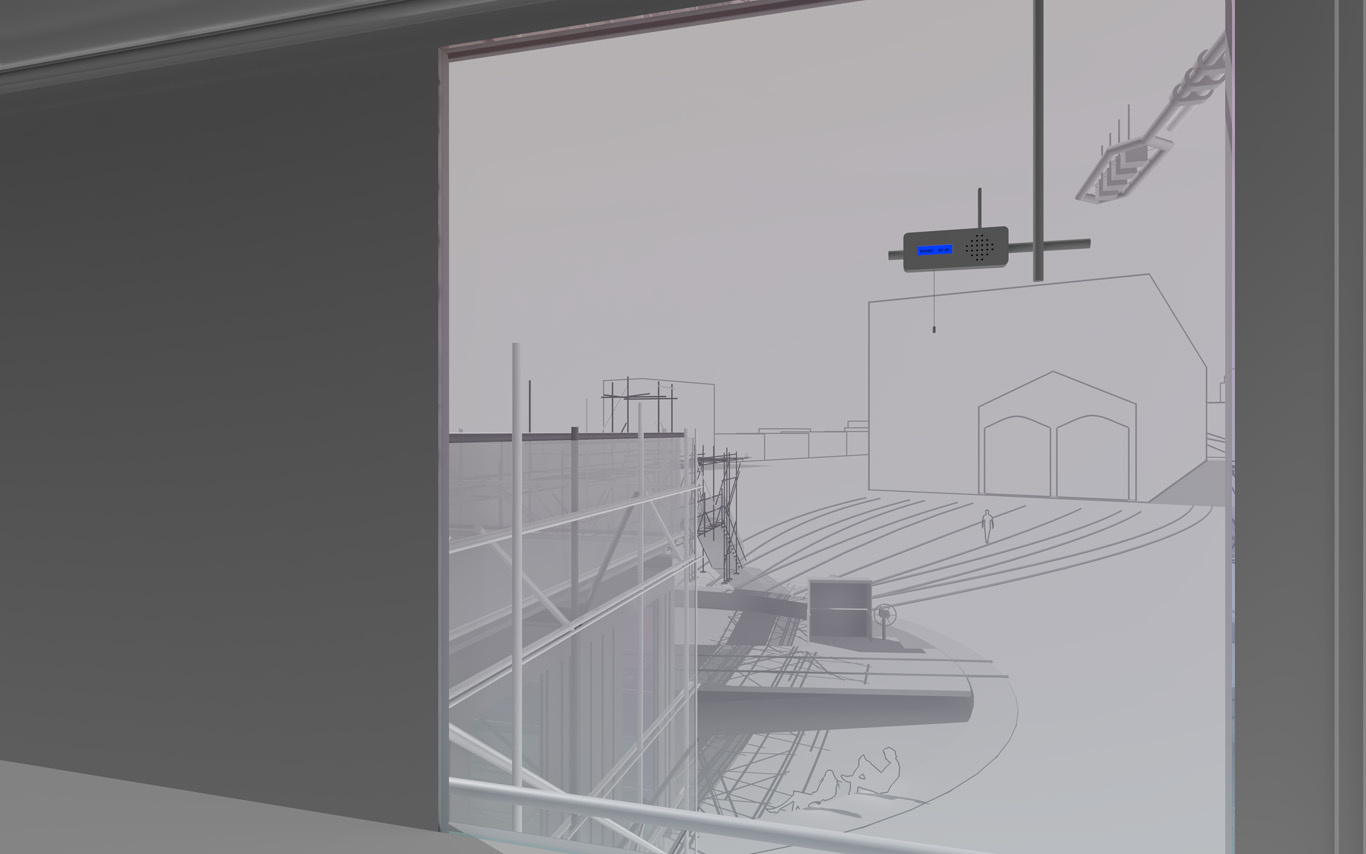

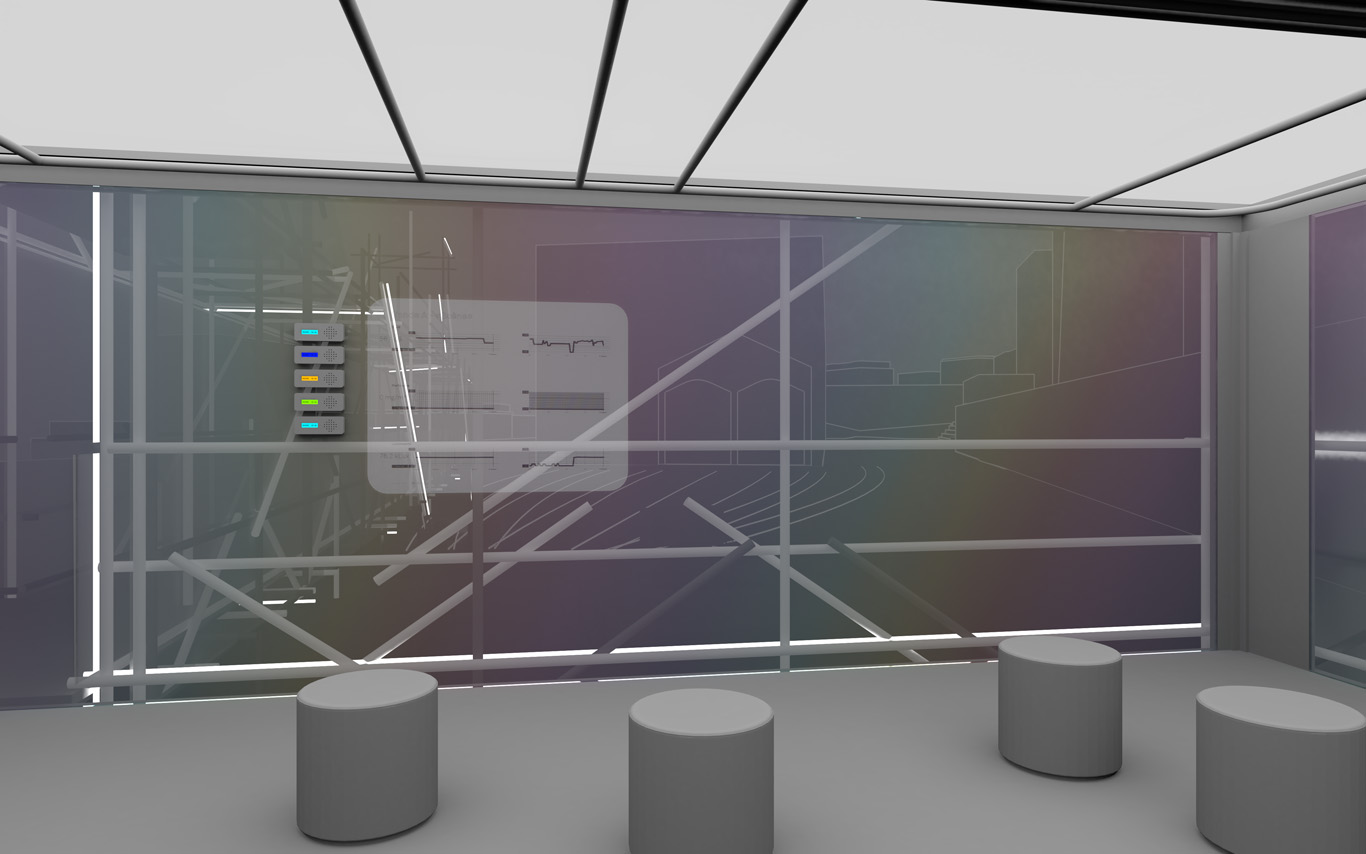

Several areas are linked to monitoring activities (input devices) and/or displays (in red, top -- that concern interests points and views from the platform or elsewhere --). These areas consist in localized devices on the platform itself (5 locations), satellite ones directly implented in the three construction sites or even in distant cities of the larger political area --these are rather output devices-- concerned by the new constructions (three museums, two new large public squares, a new railway station and a new metro). Inspired by the prior similar installation in a public park during a festival -- Heterochrony (bottom image) --, these raw data can be of different nature: visual, audio, integers from sensors (%, °C, ppm, db, lm, mb, etc.), ...

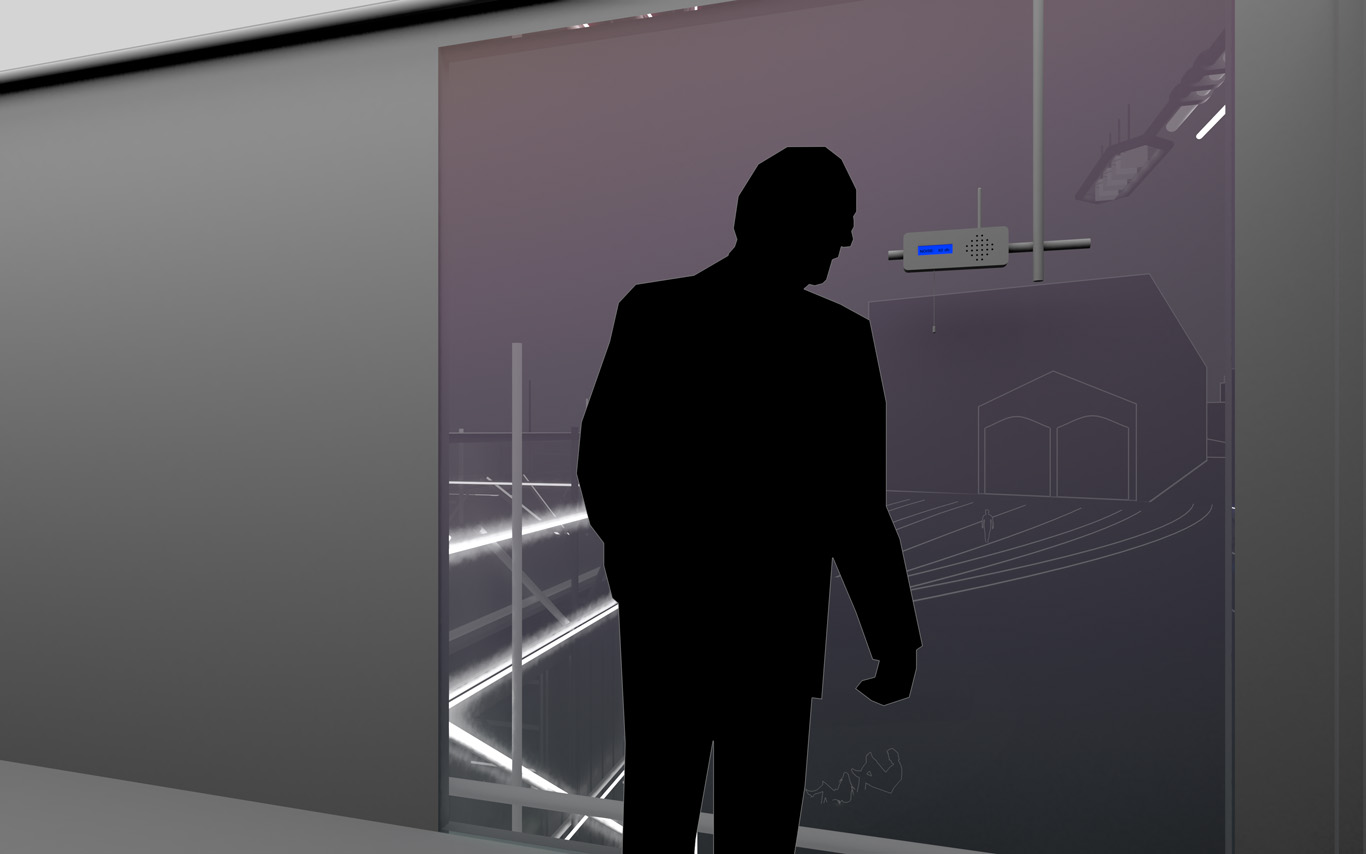

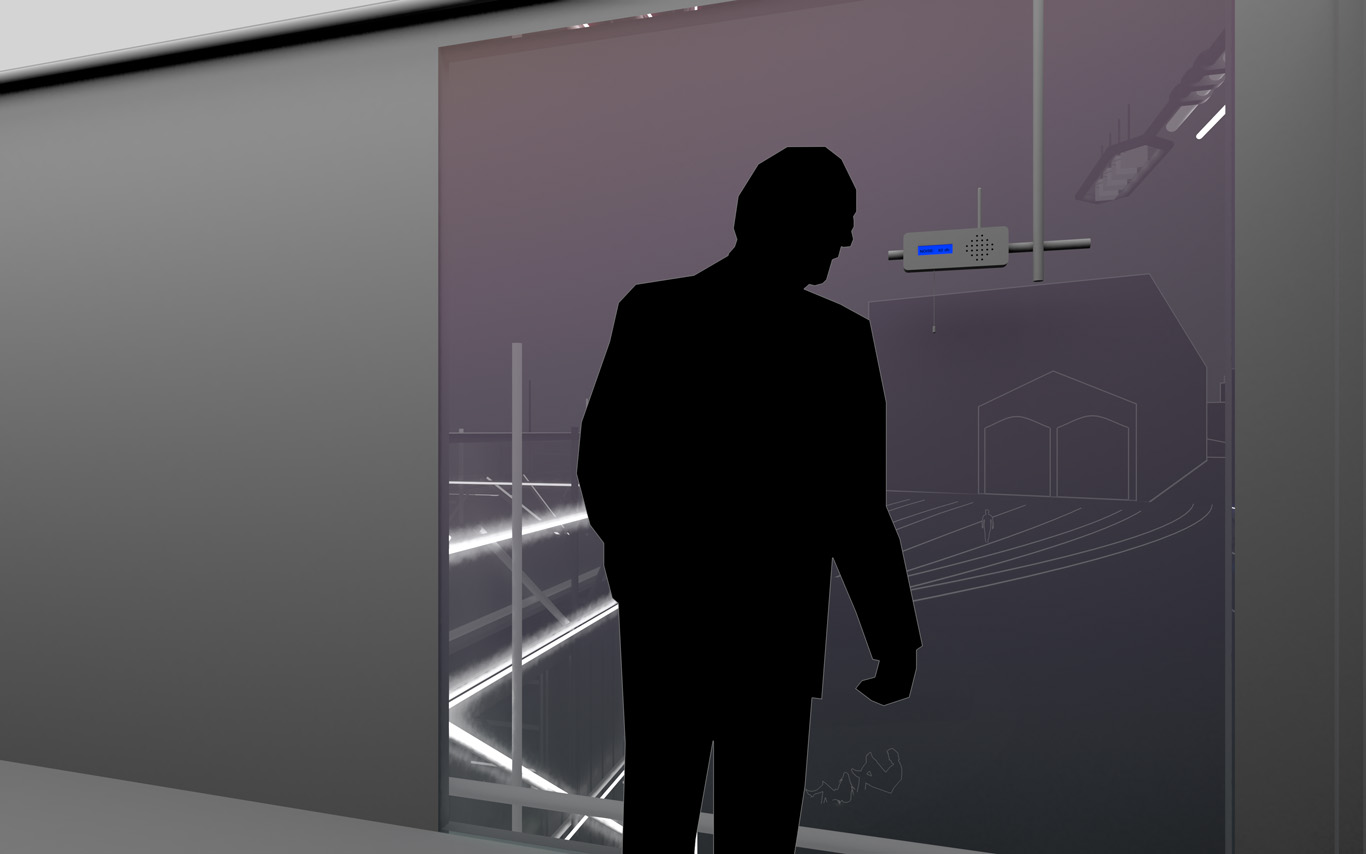

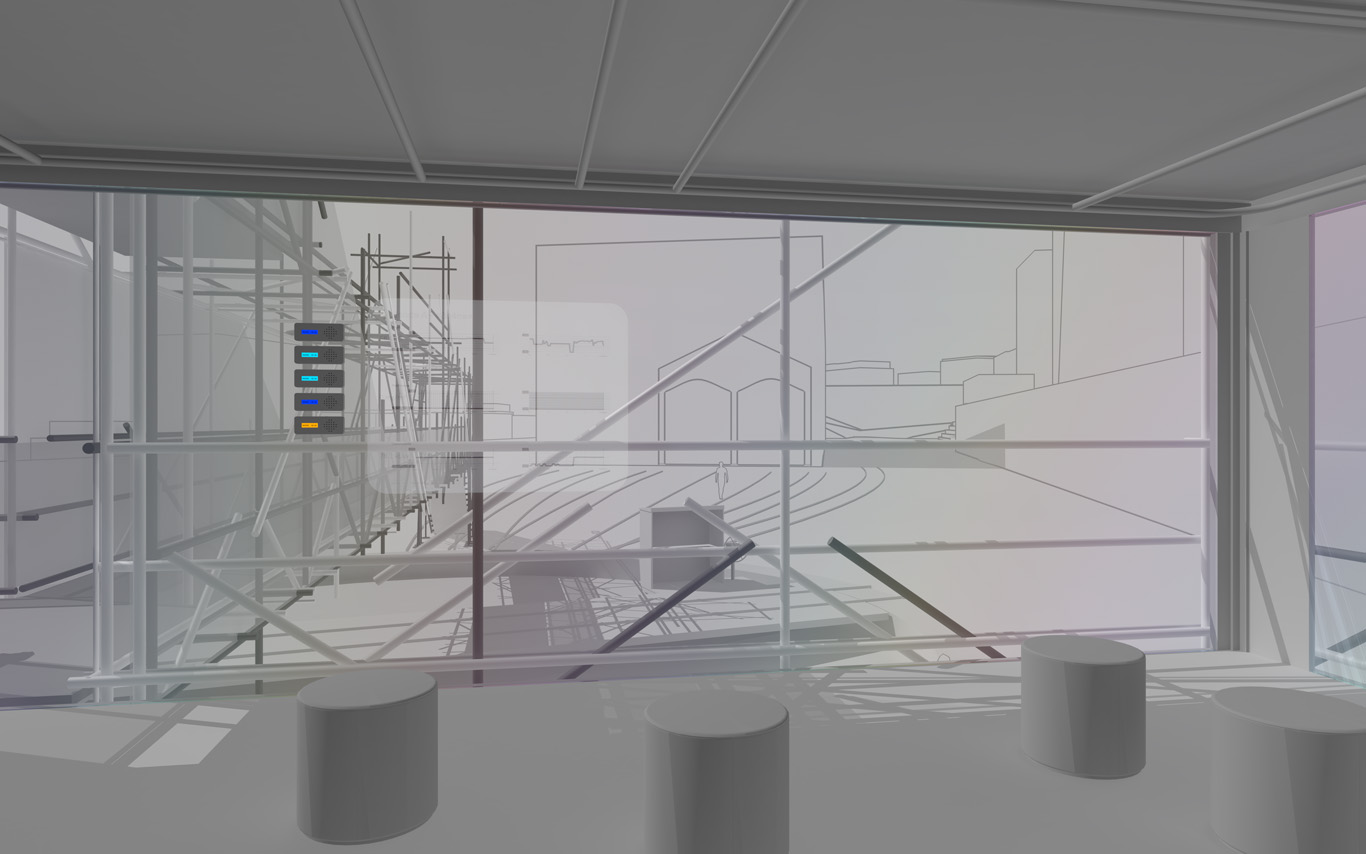

Input and output devices remain low-cost and simple in their expression: several input devices / sensors are placed outside of the pavilion in the structural elements and point toward areas of interest (construction sites or more specific parts of them). Directly in relation with these sensors and the sightseeing spots but on the inside are placed output devices with their recognizable blue screens. These are mainly voice interfaces: voice outputs driven by one bot according to architectural "scores" or algorithmic rules (middle image). Once the rules designed, the "architectural system" runs on its own. That's why we've also named the system based on automated bots "Ar.I." It could stand for "Architectural Intelligence", as it is entirely part of the architectural project.

The coding of the "Ar.I." and use of data has the potential to easily become something more experimental, transformative and performative along the life of PPoFT.

Observers (users) and their natural "curiosity" play a central role: preliminary observations and monitorings are indeed the ones produced in an analog way by them (eyes and ears), in each of the 5 interesting points and through their wanderings. Extending this natural interest is a simple cord in front of each "output device" that they can pull on, which will then trigger a set of new measures by all the related sensors on the outside. This set new data enter the database and become readable by the "Ar.I."

The whole part of the project regarding interaction and data treatments has been subject to a dedicated short study (a document about this study can be accessed here --in French only--). The main design implications of it are that the "Ar.I." takes part in the process of "filtering" which happens between the "outside" and the "inside", by taking part to the creation of a variable but specific "inside atmosphere" ("artificial artificial", as the outside is artificial as well since the anthropocene, isn't it ?) By doing so, the "Ar.I." bot fully takes its own part to the architecture main program: triggering the perception of an inside, proposing patterns of occupations.

"Ar.I." computes spatial elements and mixes times. It can organize configurations for the pavilion (data, displays, recorded sounds, lightings, clocks). It can set it to a past, a present, but also a future estimated disposition. "Ar.I." is mainly a set of open rules and a vocal interface, at the exception of the common access and conference space equipped with visual displays as well. "Ar.I." simply spells data at some times while at other, more intriguingly, it starts give "spatial advices" about the environment data configuration.

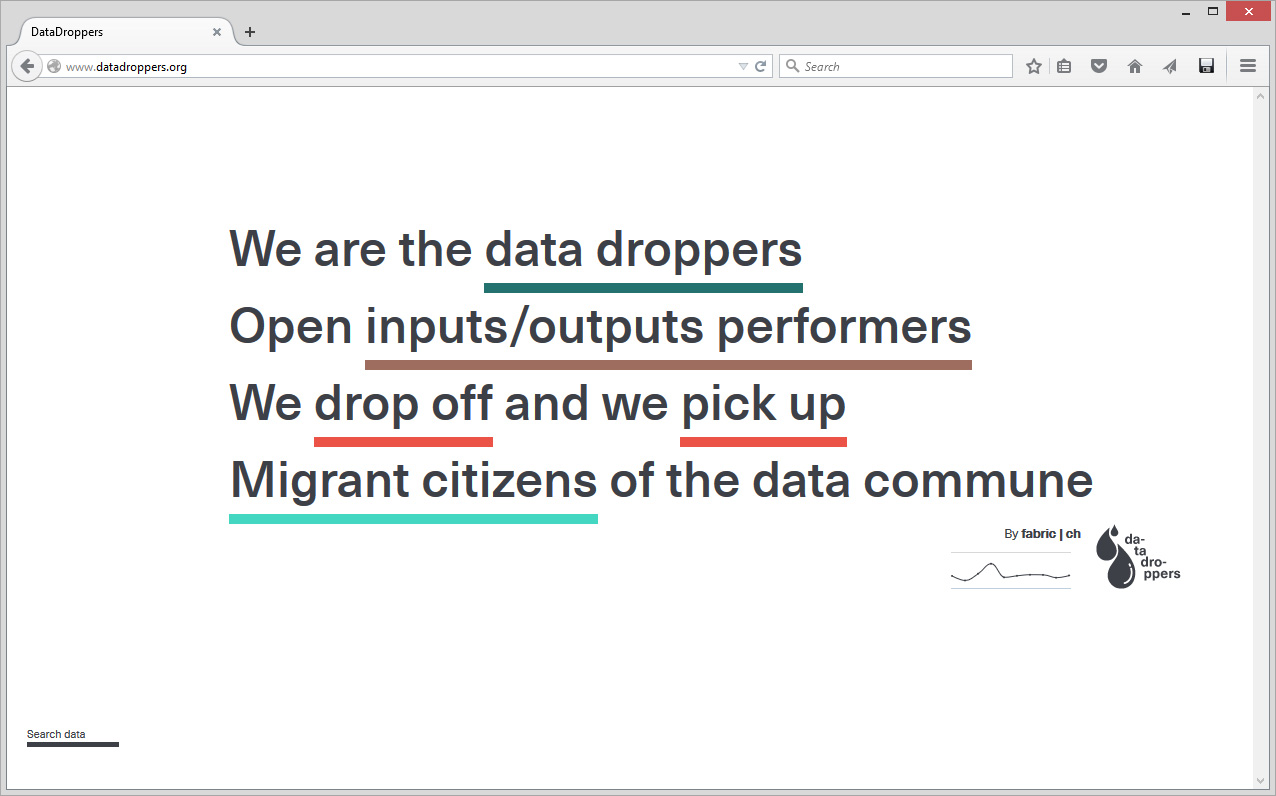

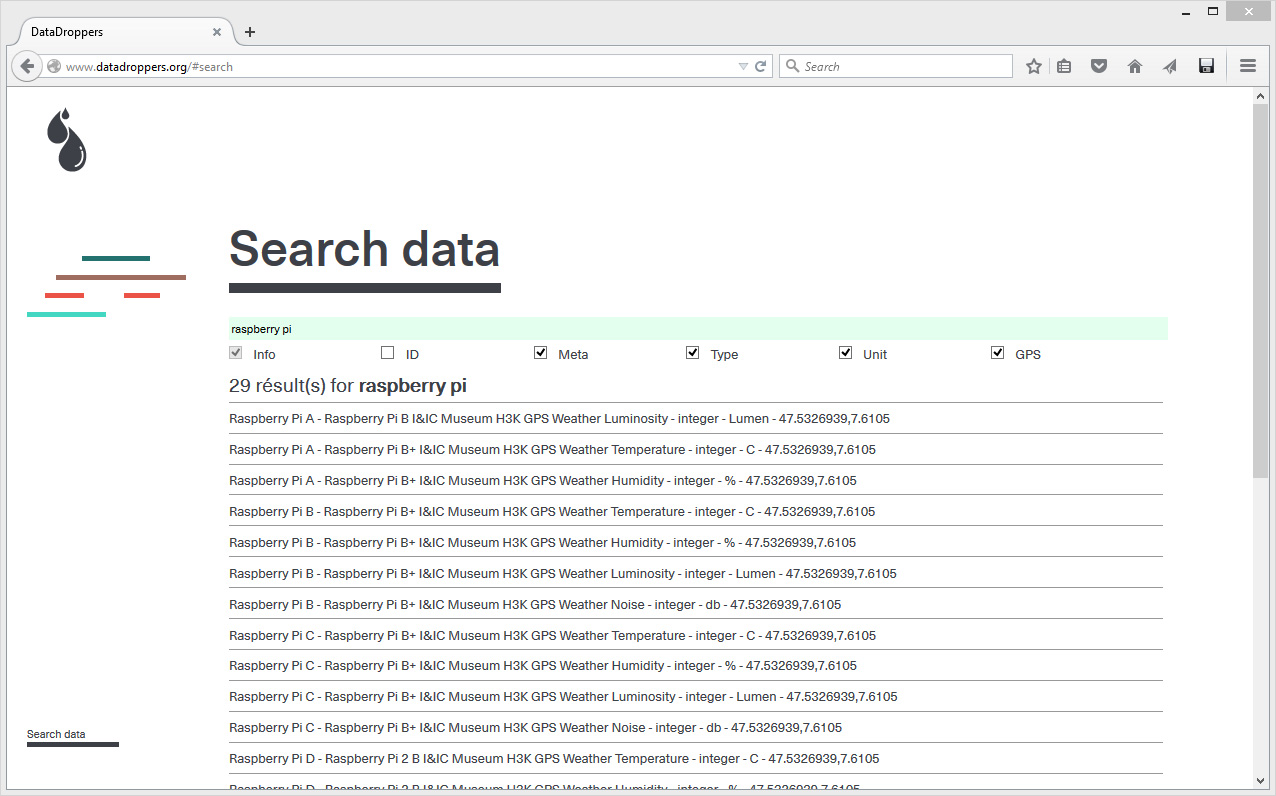

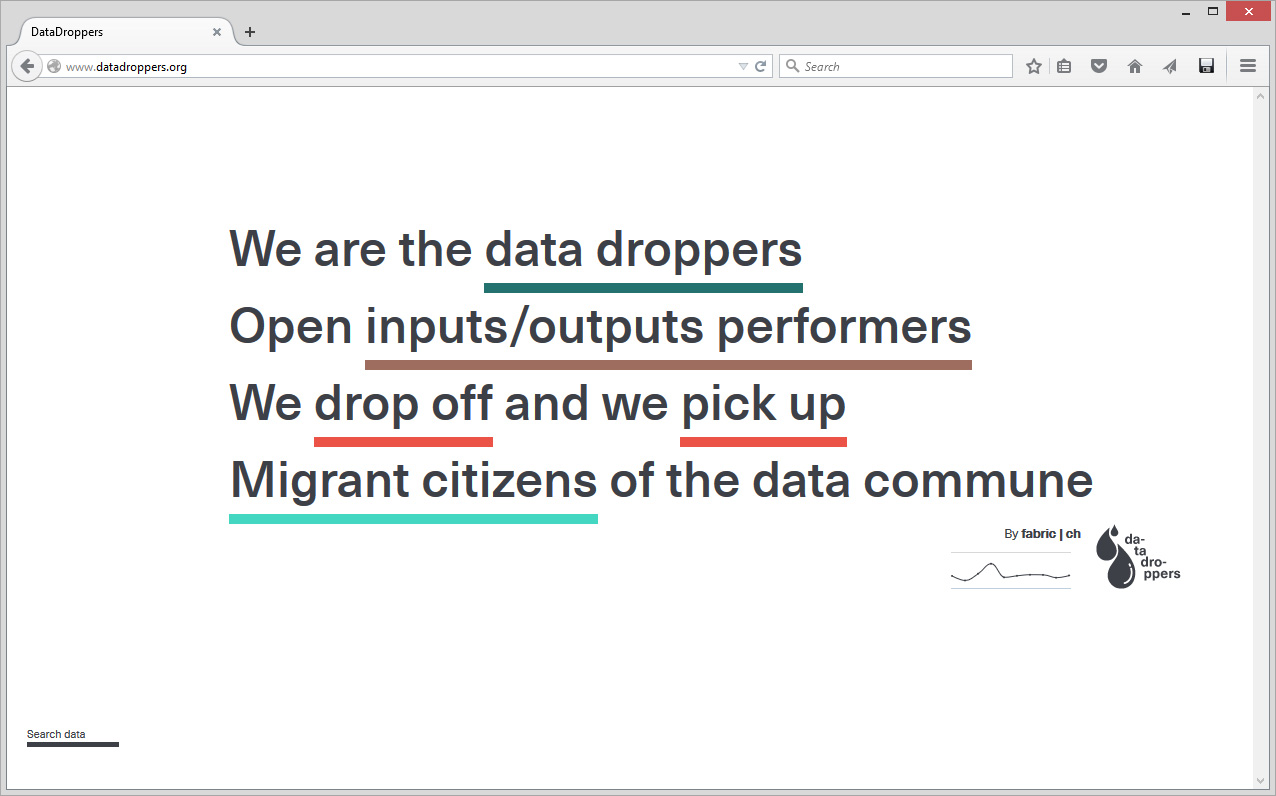

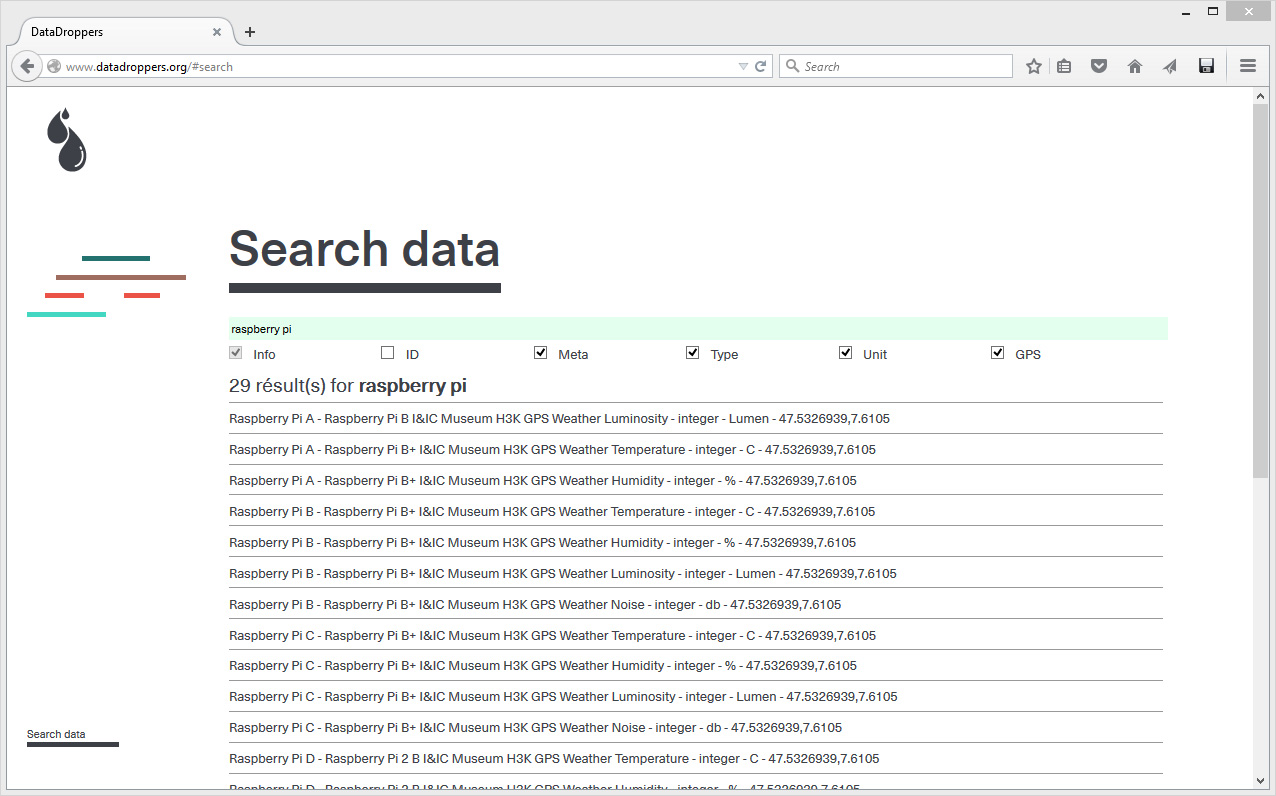

In parallel to Public Platform of Future Past and in the frame of various research or experimental projects, scientists and designers at fabric | ch have been working to set up their own platform for declaring and retrieving data (more about this project, Datadroppers, here). A platform, simple but that is adequate to our needs, on which we can develop as desired and where we know what is happening to the data. To further guarantee the nature of the project, a "data commune" was created out of it and we plan to further release the code on Github.

In tis context, we are turning as well our own office into a test tube for various monitoring systems, so that we can assess the reliability and handling of different systems. It is then the occasion to further "hack" some basic domestic equipments and turn them into sensors, try new functions as well, with the help of our 3d printer in tis case (middle image). Again, this experimental activity is turned into a side project, Studio Station (ongoing, with Pierre-Xavier Puissant), while keeping the general background goal of "concept-proofing" the different elements of the main project.

A common room (conference room) in the pavilion hosts and displays the various data. 5 small screen devices, 5 voice interfaces controlled for the 5 areas of interests and a semi-transparent data screen. Inspired again by what was experimented and realized back in 2012 during Heterochrony (top image).

----- ----- -----

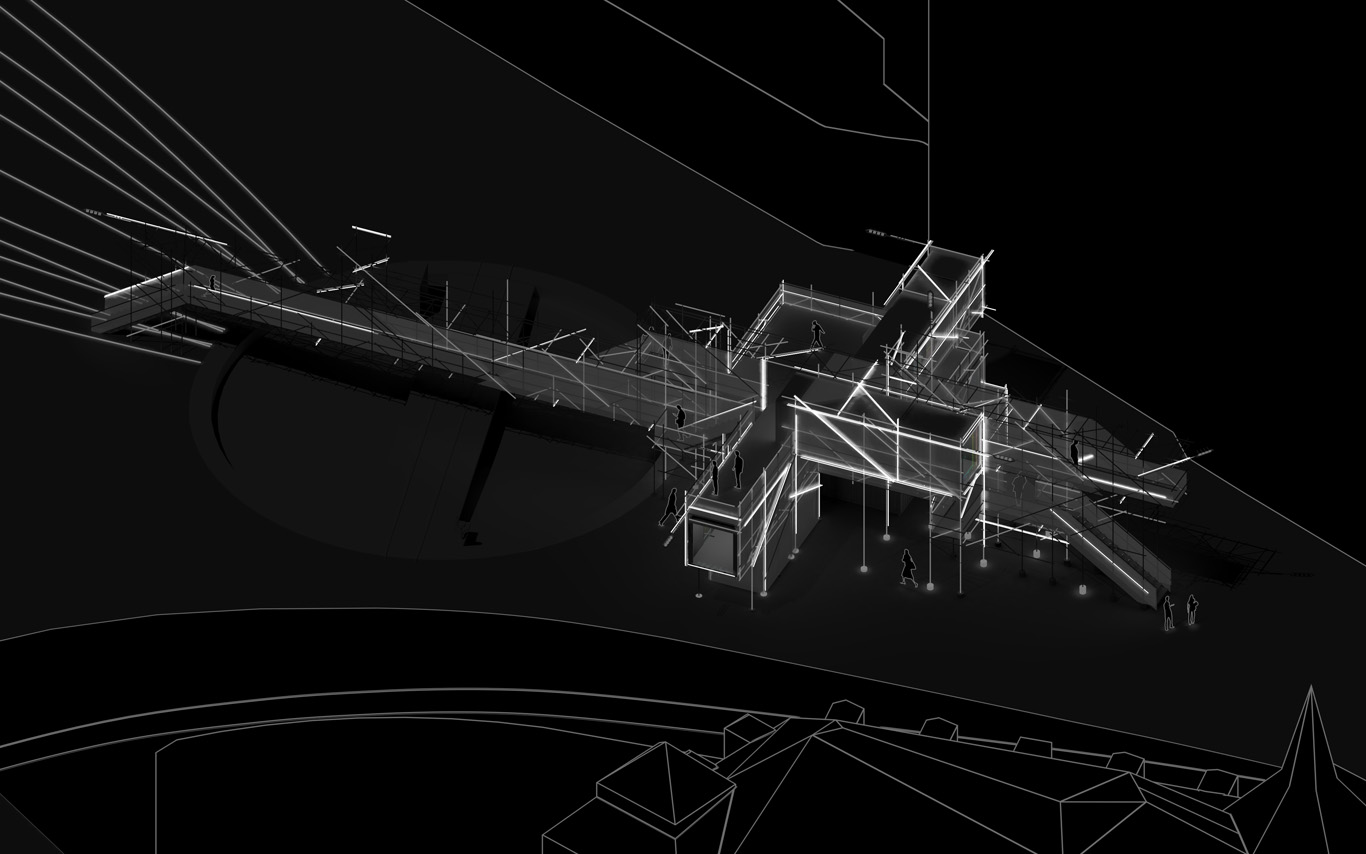

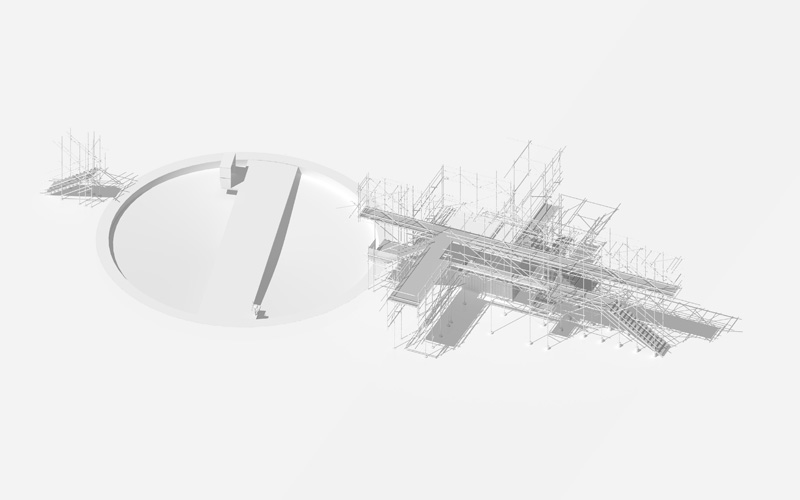

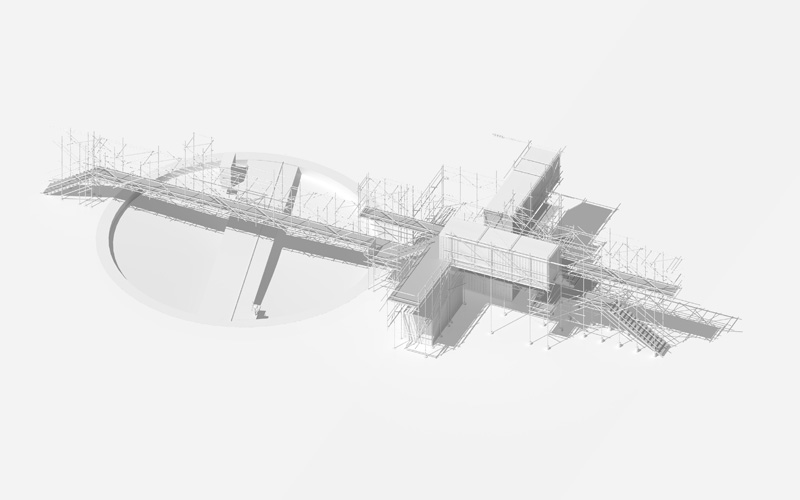

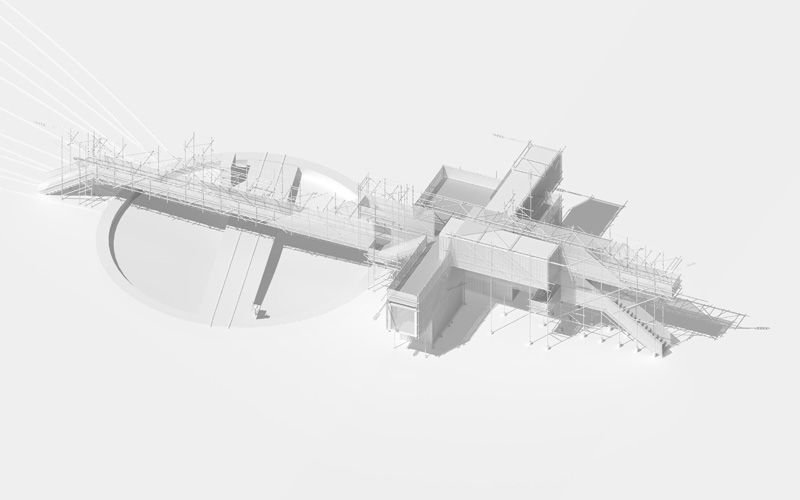

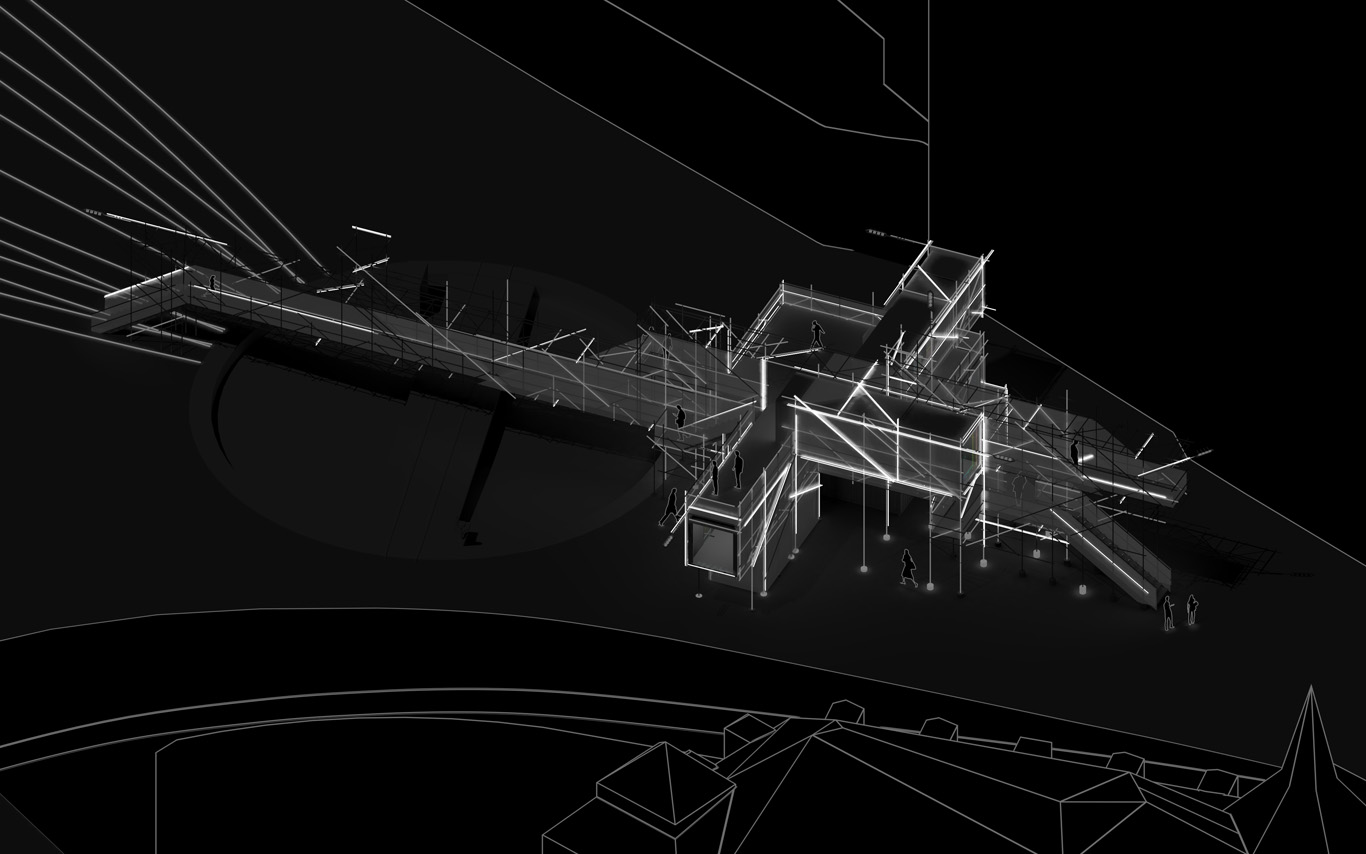

PPoFP, several images. Day, night configurations & few comments

Public Platform of Future-Past, axonometric views day/night.

.jpg)

An elevated walkway that overlook the almost archeological site (past-present-future). The circulations and views define and articulate the architecture and the five main "points of interests". These mains points concentrates spatial events, infrastructures and monitoring technologies. Layer by layer, the suroundings are getting filtrated by various means and become enclosed spaces.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Walks, views over transforming sites, ...

Data treatment, bots, voice and minimal visual outputs.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Night views, circulations, points of view.

Night views, ground.

.jpg)

Random yet controllable lights at night. Underlined areas of interests, points of "spatial densities".

Project: fabric | ch

Team: Patrick Keller, Christophe Guignard, Christian Babski, Sinan Mansuroglu, Yves Staub, Nicolas Besson.

Thursday, June 23. 2016

Note: we've been working recently at fabric | ch on a project that we couldn't publish or talk about for contractual reasons... It concerned a relatively large information pavilion we had to create for three new museums in Switzerland (in Lausanne) and a renewed public space (railway station square). This pavilion was supposed to last for a decade, or a bit longer. The process was challenging, the work was good (we believed), but it finally didn't get build...

Sounds sad but common isn't it?

...

We'll see where these many "..." will lead us, but in the meantime and as a matter of documentation, let's stick to the interesting part and publish a first report about this project.

It consisted in an evolution of a prior spatial installation entitled Heterochrony (pdf). A second post will follow soon with the developments of this competition proposal. Both posts will show how we try to combine small size experiments (exhibitions) with more permanent ones (architecture) in our work. It also marks as well our desire at fabric | ch to confront more regularly our ideas and researches with architectural programs.

This first post only consists in a few snapshots of the competition documents, while the following one should present the "final" project and ideas linked to it.

By fabric | ch

-----

.jpg)

.jpg) .jpg)

On the jury paper was written, under "price" -- as we didn't get paid for the 1st price itself -- : "Réalisation" (realization).

Just below in the same letter, "according to point 1.5 of the competition", no realization will be attributed... How ironic! We did work further on an extended study though.

A few words about the project taken from its presentation:

" (...) This platform with physically moving parts could almost be considered an archaeological footbridge or an unknown scientific device, reconfigurable and shiftable, overlooking and giving to see some past industrial remains, allowing to document the present, making foresee the future.

The pavilion, or rather pavilions, equipped with numerous sensor systems, could equally be considered an "architecture of documentation" and interaction, in the sense that there will be extensive data collected to inform in an open and fluid manner over the continuous changes on the sites of construction and tranformations. Taken from the various "points of interets' on the platform, these data will feed back applications ("architectural intelligence"?), media objects, spatial and lighting behaviors. The ensemble will play with the idea of a combination of various time frames and will combine the existing, the imagined and the evanescent. (...) "

Heterochrony, a previous installation that followed similar goals, back in 2012. http://www.heterochronie.cc

Download pdf (14 mb).

-----

Project: fabric | ch

Team: Patrick Keller, Christophe Guignard, Sinan Mansuroglu, Nicolas Besson.

Monday, December 21. 2015

Monday, November 23. 2015

Note: Meanwhile, on the "big architects" end of the spectrum... Where I enjoyed to read the sentence " Foster is delighted that Britain now has an infrastructure commission, chaired by Andrew Adonis, which he says gives the opportunity to plan in 30-year cycles and remove the politics from infrastructure."

Via The Guardian

-----

By Rowan Moore

Norman Foster’s Millau viaduct in France, which has ‘cut out five-hour traffic jams’. Photograph: Michael Reinhard/Corbis

“Do you believe in infrastructure?” asks Norman Foster, with challenge in his voice. He does. Infrastructure, he says, is about “investing not to solve the problems of today but to anticipate the issues of future generations”. He cites his hero, Joseph Bazalgette, who, in solving Victorian London’s sewage problems, “thought holistically to integrate drains with below-ground public transportation and above-ground civic virtue”.

Foster is delighted that Britain now has an infrastructure commission, chaired by Andrew Adonis, which he says gives the opportunity to plan in 30-year cycles and remove the politics from infrastructure. He will expound these views this week at the Urban Age 10th anniversary Global Debates, Urban Age being the LSE’s Deutsche Bank-sponsored series of conferences in which high-powered and highly powerful people travel the world exchanging views on city building.

Statistics spin out of him about sustainability. “If you take the carbon footprint of London, that’s one seventh of that of Atlanta, so there’s a relationship between density and emissions. The whole climate change issue, which many would argue is about the survival of the species, comes down to urbanism.

Foster’s proposed design for the Thames Hub airport. Photograph: dbox/Foster & Partners

“When I was in Harvard recently, I said that each of us in this room, the energy that we consume in one year would equal the energy consumed by two Japanese, 13 Chinese, 31 Indians and 370 Ethiopians. So you start to take the relationship between energy consumed by a society and infant mortality, life expectancy, sexual freedom, academic freedom, freedom from violence. So those societies that consume more energy have more of those desirable qualities, so all those issues are inseparable from the nature of the infrastructure.” The connections between these points are not always clear, but the argument seems to be that better use of energy through better infrastructure will enable more people to live better.

Of his own work, Foster says that many of the most important projects are not what are normally considered buildings, but things such as the Millennium Bridge, the pedestrianisation of Trafalgar Square in London, the Millau viaduct in southern France and the remaking of the Marseille waterfront. More statistics: “Millau cut out five-hour traffic jams, which meant that the saving in CO2 from the 10% of traffic that is heavy good vehicles had an effect equivalent to a forest of 40,000 trees.”

He has campaigned vigorously for the Thames Hub, a new airport in the Thames estuary with an associated network of huge ambition: an orbital railway around London, a flood barrier, tidal energy generation. He is profoundly disappointed that his plan is likely to be rejected in favour of an expanded Heathrow: “The reality of a hub airport is that you can never ever do that at Heathrow. If you do that at Heathrow now you can absolutely guarantee that we will still be pedalling furiously to stand still. You can never accommodate long-term needs there.”

Norman Foster: ‘The whole climate change issue comes down to urbanism.’ Photograph: Manolo Yllera

But given what he just said about sustainability, should we be expanding airports at all? “Do you eat meat?” he asks scathingly. “You’re probably going to have your hamburger in spite of the fact that you’re going to make a much greater impact than any travel.” Air travel, he says, “compares well statistically with the amount of methane produced by cows and the amount of energy and water needed to produce a hamburger”.

“The reality is that all society is embedded in mobility. You’re going to take that flight. You’d be better to take the flight out of an airport that is driven by tidal power and which uses natural light, and which anticipates the day when air travel will be more sustainable.” He talks of solar-powered flight and planes made of lightweight composite materials.

It could also be asked what is the role of the architect in what is generally the province of engineers, planners and politicians. Around us is evidence of his practice’s apparent potency – towers in China and India, a model of the giant circle, one mile in circumference, which will be Apple’s new headquarters, images of a concept for habitats on Mars – but Foster says: “I have no power as an architect, none whatsoever. I can’t even go on to a building site and tell people what to do.” Advocacy, he says, is the only power an architect ever has.

To write about Foster presents a particular challenge to an architecture critic. The scale of his achievement is immense and he has created many outstanding buildings. A wise man recently pointed out that if Foster had only built his 20 or 30 best works, critical admiration would be virtually unqualified. It is largely because his practice has designed many more projects than this that he sometimes gets a bad press. But would it really have been better if he had confined himself to a boutique practice in order to preserve his architectural purity?

It can seem peevish and petty to question his work, but it is not beyond criticism. In particular, it can become weaker the more it makes contact with realities outside itself. If you look upwards in the Great Court he designed in the British Museum, you will see an impressive structure of steel and glass, but at your own level it becomes bland and sometimes clumsy. The Gherkin is a memorable presence on the London skyline, but awkward at pavement level. The Millennium Bridge, even with the modifications necessary to stop it wobbling, is confident and elegant except at its landing, where the overhang of its cantilever creates spaces that are plain nasty.

In the context of infrastructure, the question is also whether it adapts to the political, social and physical conditions that surround it. In answer to Foster’s question, yes, I do believe in infrastructure. Or, rather, I’d compare it to water: essential to existence, life-enhancing and sometimes beautiful, but with the power to damage and destroy if misused.

Design for the proposed drone-port project in Rwanda. Photograph: Foster & Partners

All this makes a new drone-port project in Rwanda one of Foster and Partners’ most intriguing. Conceived with Jonathan Ledgard, the director of Afrotech, who describes himself as a thinker on the future of Africa, it is a plan to create a network of cargo drones that can bring medical supplies and blood, plus spare parts, electronics and e-commerce, to hard-to-access parts of Africa. The drones have ports – shelters where they can safely land and unload, but which also serve as “a health clinic, a digital fabrication shop, a post and courier room, and an e-commerce trading hub, allowing it to become part of local community life”. Because of their inaccessible locations, they have to be built using materials close to hand, so techniques have been developed for efficiently making local earth into bricks and stones into foundations.

It is impossible at this point and at this distance to know if the drone-port project will achieve what it hopes, but its ambition to adapt to local conditions seems absolutely to the point. The interesting question is then how to bring the same thinking to infrastructure in a developed country, such as Britain. What is the right infrastructure for the society and culture of this country, at this point? Has it changed since Foster’s Victorian heroes, such as Bazalgette, did their work? Can we import the large-scale thinking of modern China and, if so, with what modification? These are good questions for an architect to address.

Urban Age Global Debates run until 3 December; lsecities.net/ua

Wednesday, August 26. 2015

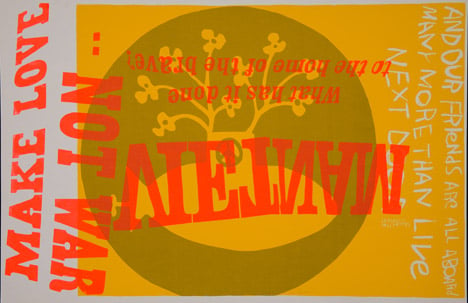

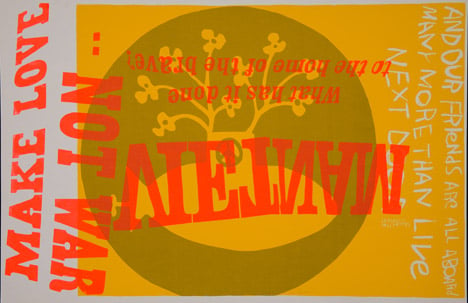

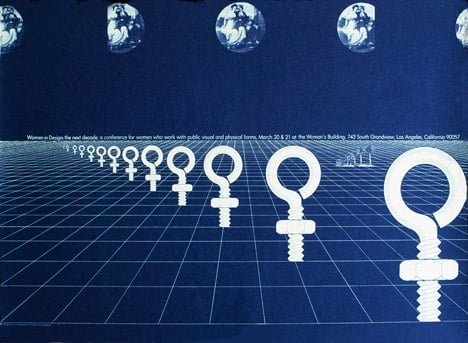

Note: In parallel with the exhibition about the work of E.A.T at the Museum der Moderne in Salzburg, another exhibition: Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia that will certainly be worth a detour at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis later this autumn.

Via Dezeen

-----

The architecture and design of the counterculture era has been overlooked, according to the curator of an upcoming exhibition dedicated to "Hippie Modernism".

Yellow submarine by Corita Kent, 1967. Photograph by Joshua White

The radical output of the 1960s and 1970s has had a profound influence on contemporary life but has been "largely ignored in official histories of art, architecture and design," said Andrew Blauvelt, curator of the exhibition that opens at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis this autumn.

"It's difficult to identify another period of history that has exerted more influence on contemporary culture and politics," he said.

"Much of what was produced in the creation of various countercultures did not conform to the traditional definitions of art, and thus it has largely been ignored in official histories of art, architecture, and design," he said. "This exhibition and book seeks to redress this oversight."

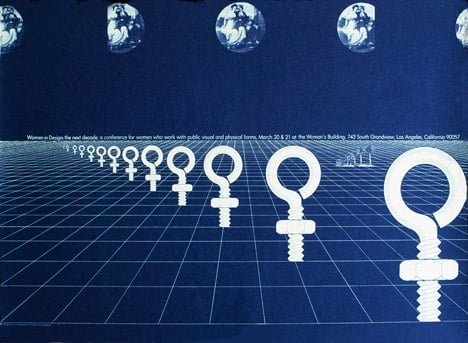

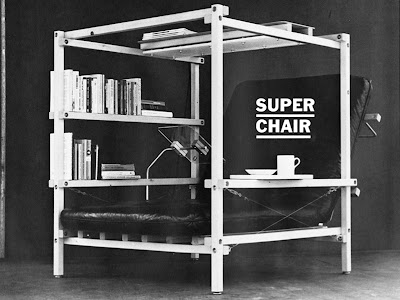

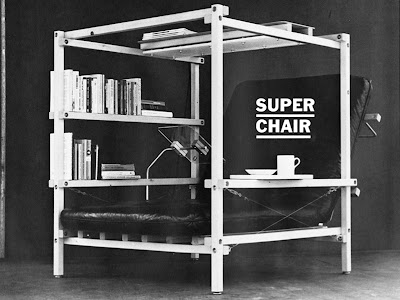

Superchair by Ken Isaacs, 1967

Women in Design: The Next Decade by Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, 1975. Courtesy of Sheila Levrant de Bretteville

While not representative of a formal movement, the works in Hippie Modernism challenged the establishment and high Modernism, which had become fully assimilated as a corporate style, both in Europe and North America by the 1960s.

The exhibition, entitled Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia will centre on three themes taken from taken from American psychologist and psychedelic drug advocate Timothy Leary's era-defining mantra: Turn on, tune in, drop out.

Organised with the participation of the Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive, it will cover a diverse range of cultural objects including films, music posters, furniture, installations, conceptual architectural projects and environments.

Hendrixwar/Cosmococa Programa-in-Progress, 1973. Courtesy of the Walker Art Center collection, Minneapolis

Jimi Hendrix, Ira Cohen, 1968. Photograph from the Mylar Chamber, courtesy of the Ira Cohen Archive

The Turn On section of the show will focus on altered perception and expanded individual awareness. It will include conceptual works by British avant-garde architectural group Archigram, American architecture collective Ant Farm, and a predecessor to the music video by American artist Bruce Conner – known for pioneering works in assemblage and video art.

Tune In will look at media as a device for raising collective consciousness and social awareness around issues of the time, many of which resonate today, like the powerful graphics of the US-based black nationalist party Black Panther Movement.

Untitled [the Cockettes] by Clay Geerdes, 1972. Courtesy of the estate of Clay Geerdes

Drop Out includes alternative structures that allowed or proposed ways for individuals and groups to challenge norms or remove themselves from conventional society, with works like the Drop City collective's recreation dome – a hippie version of a Buckminster Fuller dome – and Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison's Portable Orchard, a commentary on the loss of agricultural lands to the spread of suburban sprawl.

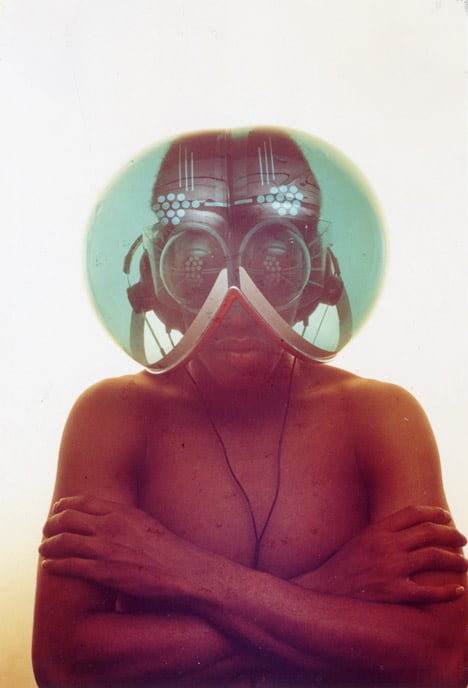

Environment Transformer/Flyhead Helmet by Haus-Rucker-Co, 1968. Photograph courtesy of Haus-Rucker-Co and Gerald Zugmann

The issues raised by the projects in Hippie Modernism – racial justice, women's and LGBT rights, environmentalism, and localism among many other – continue to shape culture and politics today.

Blauvelt sees the period's ongoing impact in current practices of public-interest design and social-impact design, where the authorship of the building or object is less important than the need that it serves.

Payne's Gray by Judith Williams, circa 1966. Photograph courtesy of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia

Superonda Sofa by Archizoom Associati, 1966. Photograph courtesy of Dario Bartolini, Archizoom Associati

Many of the exhibited artists, designers, and architects created immersive environments that challenged notions of domesticity, inside/outside, and traditional limitations on the body, like the Italian avant-garde design group Superstudio's Superonda: conceptual furniture which together creates an architectural landscape that suggests new ways of living and socialising.

Hello Dali by Isaac Abrams, 1965

Blauvelt sees the period's utopian project ending with the OPEC oil crisis of the mid 1970s, which helped initiate the more conservative consumer culture of the late 1970s and 1980s.

Organised in collaboration with the Berkeley Art Museum and the Pacific Film Archive, Hippie Modernism will run from 24 October 2015 to 28 February 2016 at the Walker Art Center.

Thursday, August 06. 2015

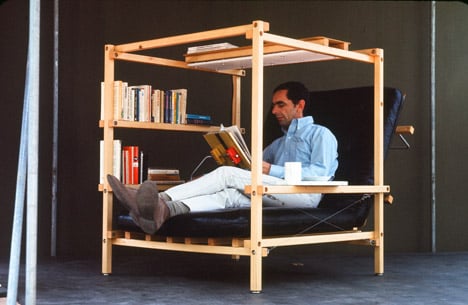

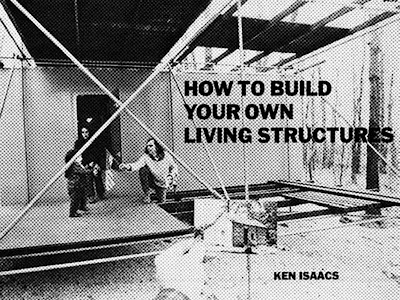

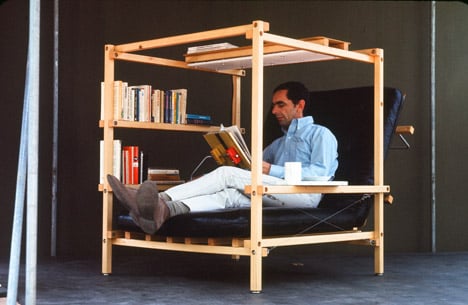

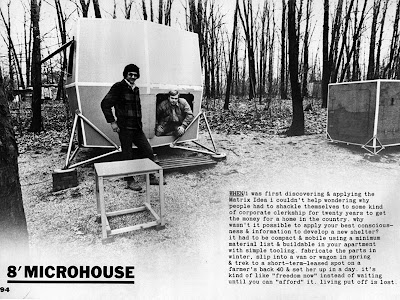

Note: we remain in history for a little more time... It's now Ken Isaacs' turn to be praised for his work around micro inhabitable spaces and living structures! I post this with the iodea in mind that his work could serve as reference for a future workshop next November at ECAL, probably with rAndom International as guests and when we'll continue to work around "cloud computing" and its infrastructure (datacenter), looking for counter-proposals or rather "counter-designs".

Via Object Guerilla

-----

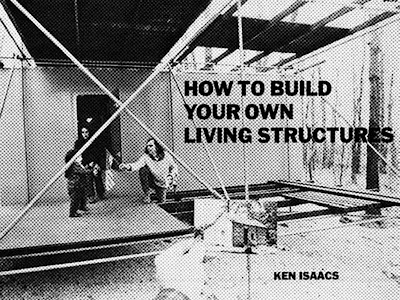

This week at work I picked up an old book, How to Build Your Own Living Structures, by Ken Isaacs, to read at lunch. I didn't finish it, so I brought it home. A little internet-ing revealed this book was out-of-print, rare, and selling for a good bit at various outlets. However, I think the copyright has lapsed, because it is available online as a PDF.

Isaacs was born in 1927 in Peoria, Illinois, and served in the military as a young man. After Korea, he studied architecture, and then began to craft a career as a designer, architect, and educator. In the late fifties, he became Head of Design at the Cranbrook Academy of Arts, birthplace of much notable mid-century modernism, including Eliel and Eero Saarinen Charles and Ray Eames, and Harry Weese. He also spent some time teaching at the Illinois Institute of Technology, founded by Mies van der Rohe as a sort of Bauhaus West.

During an itinerant period in the sixties, Isaacs began to develop what he called a Matrix system for home furnishing. He theorized (rightly and wrongly) that most of the interior volume of our homes and apartments lay unused, as most furniture only inhabits the 2-D floor plane. In his own words: "traditional furniture was never organized as a whole system. the pieces were a bunch of separate, unrelated objects determined by inertia & sentiment. feeble efforts were made to organize them "visually", but that was always just another trap. the old culture has always tried to make the unworkable endurable by overlaying it with whichever "good taste" is going at the moment. unfortunately this is like trying to make airplanes look like birds. that never worked either. that's because you can't make feathers out of aluminum." (p. 35 Liberated Space) Spoken like one fierce guerilla.

Cover, via Pop-Up City.

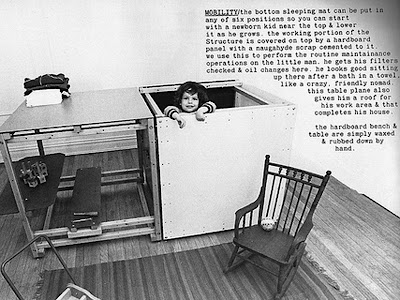

In order to conserve floor space and create flexible environments (somewhere between furniture and building) he and his wife put together matrices of 48" cubes made of 2" x 2" structural members. Each 2" x 2" was drilled with a regular pattern of holes, which allowed them to be bolted together in various configurations, accept accessories, and be disassembled. The basic idea, an Erector set for adults, has now been commercialized as "grid beams".

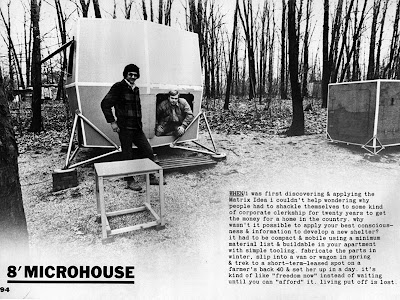

Matrix-based "super chair." Nowadays, most of that stuff can be replaced with an iPad... The next iterative leap in the Matrix was to do away with the framing altogether. Isaacs developed rigid stress-skin structures, using plywood and "L" brackets to make cubes. The cubes were built in modules: 16", 24", and eventually, 48". Smaller units were used for storage; mid-size ones could serve as desks and chairs; and the large units became the first Micro-Houses.

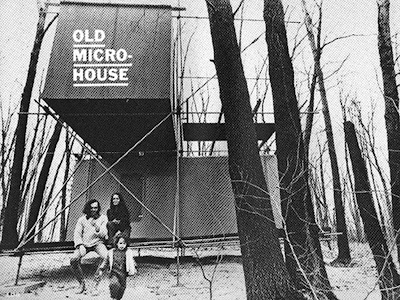

Today's term of art is "tiny house". The recession, amongst other converging trends, has exploded the popularity of tiny houses. These shelters are usually sub-500 square feet and built on trailers or temporary foundations, allowing them to escape most building codes and zoning regulations. Architecturally, most tiny houses seem to be shrunken big houses, resulting in a riotously cute dollhouse effect, like a Thomas Kinkaide painting come to life.

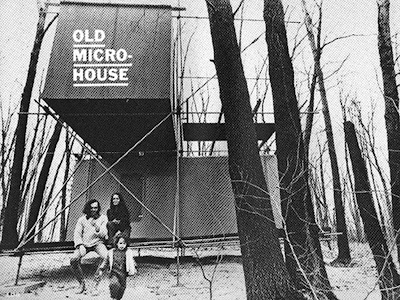

The Micro-House, circa late 60s, via Pop-Up City. Isaacs had the same idea, but he designed a modular, flat-pack, lightweight, re-configurable system. Combining the original beam-based Matrix and the stud-less panel structures, he built 8-foot modules out of 1" steel pipe and inserted plywood volumes into the matrix. Taking the classic modernist approach -- divorcing structure and skin -- he came up with a cheap, versatile house. The First Microhouse, built with a Graham Foundation grant in Groveland, Illinois, (near Carbondale, home of fellow light structure pioneer Buckminster Fuller), looks dated in the photos, but also startlingly fresh. I love the raw, stark geometry of it, everything stripped down to the margins.

Another variation on the Microhouse -- it is infinitely reconfigurable. His 8' Microhouse is very of its era, but has nonetheless managed to inspire at least one modern imitator, in Glasgow. It creates an 8' volume based on a matrix of eight 4' volumes bolted together. The canted sides, tetrahedral feet, and hatch doors give it a real Apollo feel, minus the silvery skin.

The plywood stress-skin Microhouse. Throughout, wrapped in some seventies slang and general architectural hooliganism, Isaacs stresses pre-fabrication, modularity, simplicity, and off-the-shelf parts. None of the projects are particularly difficult to make with simple tools(a little time-consuming, perhaps). The book itself is a bit shambling, combining personal narrative, philosophical inquiry, and DIY instructions. In many ways, it seems like a blog, written with no caps and little editing. Some of the book sale listings I found online show the original as spiral-bound, in keeping with its guerilla nature.

It seems many of his designs were waiting for the technology to catch up. I was struck by the fact that everything in the book is very suited to modern micro-production techniques. With a stack of plywood and a CNC machine, you could be manufacturing flat-pack Micro-Houses on demand. A laser cutter could churn out his storage Matrix, and a MakerBot could very well print 3-axis connectors for steel pipe.

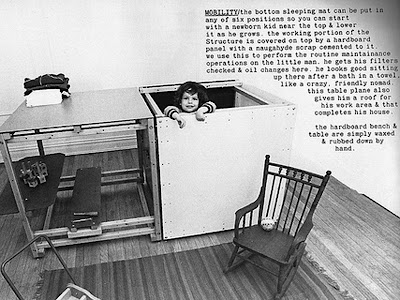

I'll end with a story from Isaacs, about getting a crib for his two year-old son. I often feel the same way: why buy when you can make?

"trouble in eden. one day i found myself in a suburban department store hallucinating Carole asking the lady if she could buy a crib. this immediately induced hyperventilation into my system & i got ready to demonstrate new audio highs for the very proper audience of clerks and matrons. together we managed a fair Wagnerian racket.

There was no other choice though. so we got the nifty crib & it hung there for quite a while like the albatross, a reminder of a monstrous negative act. it sure got us on for his Structure, though." (p. 43 Crisis and the Shoemaker's Child)

They were eventually able to replace the department-store albatross with this number.

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)