Note: we remain in history for a little more time... It's now Ken Isaacs' turn to be praised for his work around micro inhabitable spaces and living structures! I post this with the iodea in mind that his work could serve as reference for a future workshop next November at ECAL, probably with rAndom International as guests and when we'll continue to work around "cloud computing" and its infrastructure (datacenter), looking for counter-proposals or rather "counter-designs".

Via Object Guerilla

-----

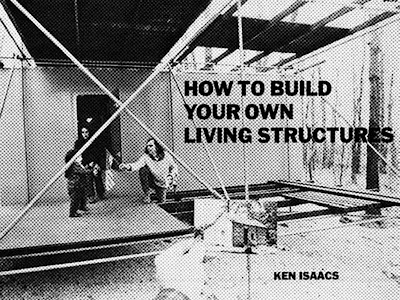

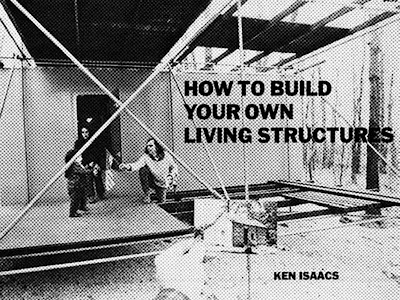

This week at work I picked up an old book, How to Build Your Own Living Structures, by Ken Isaacs, to read at lunch. I didn't finish it, so I brought it home. A little internet-ing revealed this book was out-of-print, rare, and selling for a good bit at various outlets. However, I think the copyright has lapsed, because it is available online as a PDF.

Isaacs was born in 1927 in Peoria, Illinois, and served in the military as a young man. After Korea, he studied architecture, and then began to craft a career as a designer, architect, and educator. In the late fifties, he became Head of Design at the Cranbrook Academy of Arts, birthplace of much notable mid-century modernism, including Eliel and Eero Saarinen Charles and Ray Eames, and Harry Weese. He also spent some time teaching at the Illinois Institute of Technology, founded by Mies van der Rohe as a sort of Bauhaus West.

During an itinerant period in the sixties, Isaacs began to develop what he called a Matrix system for home furnishing. He theorized (rightly and wrongly) that most of the interior volume of our homes and apartments lay unused, as most furniture only inhabits the 2-D floor plane. In his own words: "traditional furniture was never organized as a whole system. the pieces were a bunch of separate, unrelated objects determined by inertia & sentiment. feeble efforts were made to organize them "visually", but that was always just another trap. the old culture has always tried to make the unworkable endurable by overlaying it with whichever "good taste" is going at the moment. unfortunately this is like trying to make airplanes look like birds. that never worked either. that's because you can't make feathers out of aluminum." (p. 35 Liberated Space) Spoken like one fierce guerilla.

Cover, via Pop-Up City.

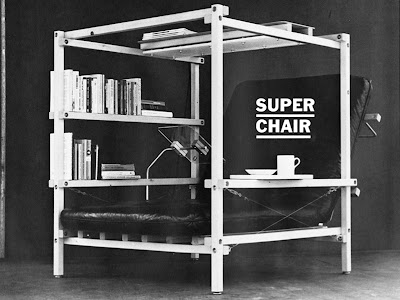

In order to conserve floor space and create flexible environments (somewhere between furniture and building) he and his wife put together matrices of 48" cubes made of 2" x 2" structural members. Each 2" x 2" was drilled with a regular pattern of holes, which allowed them to be bolted together in various configurations, accept accessories, and be disassembled. The basic idea, an Erector set for adults, has now been commercialized as "grid beams".

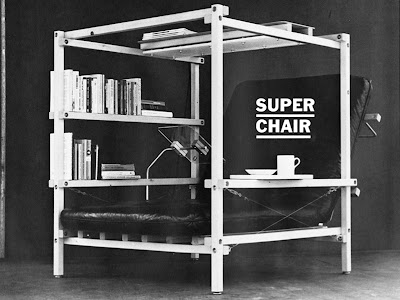

Matrix-based "super chair." Nowadays, most of that stuff can be replaced with an iPad... The next iterative leap in the Matrix was to do away with the framing altogether. Isaacs developed rigid stress-skin structures, using plywood and "L" brackets to make cubes. The cubes were built in modules: 16", 24", and eventually, 48". Smaller units were used for storage; mid-size ones could serve as desks and chairs; and the large units became the first Micro-Houses.

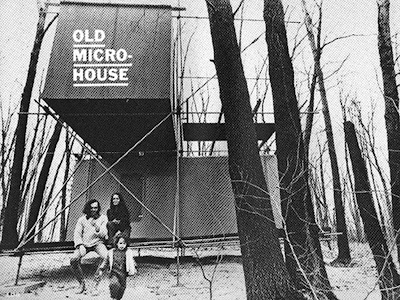

Today's term of art is "tiny house". The recession, amongst other converging trends, has exploded the popularity of tiny houses. These shelters are usually sub-500 square feet and built on trailers or temporary foundations, allowing them to escape most building codes and zoning regulations. Architecturally, most tiny houses seem to be shrunken big houses, resulting in a riotously cute dollhouse effect, like a Thomas Kinkaide painting come to life.

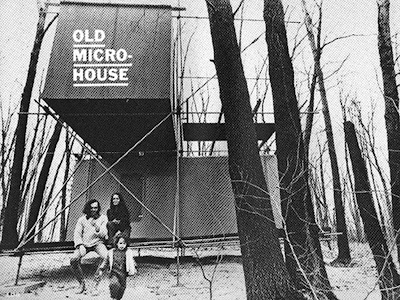

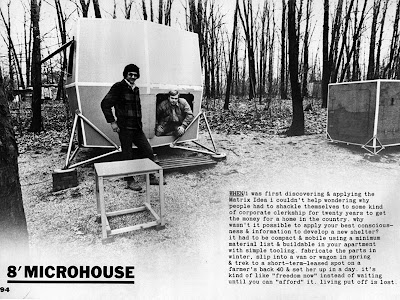

The Micro-House, circa late 60s, via Pop-Up City. Isaacs had the same idea, but he designed a modular, flat-pack, lightweight, re-configurable system. Combining the original beam-based Matrix and the stud-less panel structures, he built 8-foot modules out of 1" steel pipe and inserted plywood volumes into the matrix. Taking the classic modernist approach -- divorcing structure and skin -- he came up with a cheap, versatile house. The First Microhouse, built with a Graham Foundation grant in Groveland, Illinois, (near Carbondale, home of fellow light structure pioneer Buckminster Fuller), looks dated in the photos, but also startlingly fresh. I love the raw, stark geometry of it, everything stripped down to the margins.

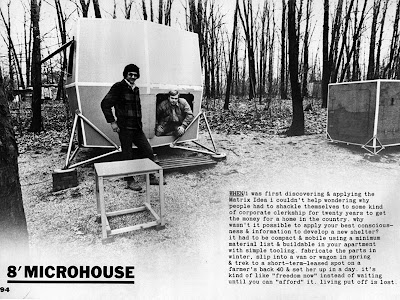

Another variation on the Microhouse -- it is infinitely reconfigurable. His 8' Microhouse is very of its era, but has nonetheless managed to inspire at least one modern imitator, in Glasgow. It creates an 8' volume based on a matrix of eight 4' volumes bolted together. The canted sides, tetrahedral feet, and hatch doors give it a real Apollo feel, minus the silvery skin.

The plywood stress-skin Microhouse. Throughout, wrapped in some seventies slang and general architectural hooliganism, Isaacs stresses pre-fabrication, modularity, simplicity, and off-the-shelf parts. None of the projects are particularly difficult to make with simple tools(a little time-consuming, perhaps). The book itself is a bit shambling, combining personal narrative, philosophical inquiry, and DIY instructions. In many ways, it seems like a blog, written with no caps and little editing. Some of the book sale listings I found online show the original as spiral-bound, in keeping with its guerilla nature.

It seems many of his designs were waiting for the technology to catch up. I was struck by the fact that everything in the book is very suited to modern micro-production techniques. With a stack of plywood and a CNC machine, you could be manufacturing flat-pack Micro-Houses on demand. A laser cutter could churn out his storage Matrix, and a MakerBot could very well print 3-axis connectors for steel pipe.

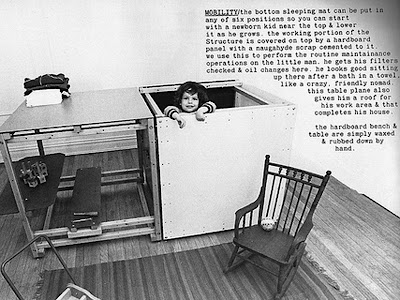

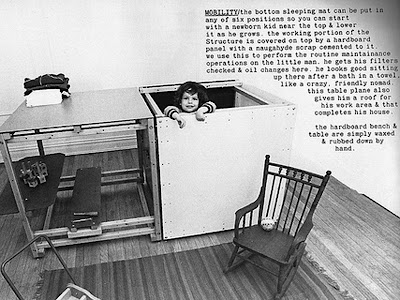

I'll end with a story from Isaacs, about getting a crib for his two year-old son. I often feel the same way: why buy when you can make?

"trouble in eden. one day i found myself in a suburban department store hallucinating Carole asking the lady if she could buy a crib. this immediately induced hyperventilation into my system & i got ready to demonstrate new audio highs for the very proper audience of clerks and matrons. together we managed a fair Wagnerian racket.

There was no other choice though. so we got the nifty crib & it hung there for quite a while like the albatross, a reminder of a monstrous negative act. it sure got us on for his Structure, though." (p. 43 Crisis and the Shoemaker's Child)

They were eventually able to replace the department-store albatross with this number.