Tuesday, April 18. 2017

Note: following the post about the conference at Bartlett about game design and architecture, I also post this link (show reel) regarding the recent set & prop design for the movie Ghost in the Shell.

We can certainly discuss the quality of the movie indeed, or rather its necessity compared to the original japan anime (a funny remark about it though: if you have the questionable chance to be "reborned" or "ghosted" like the major in the remade movie, you'll transform from asian to caucasian white ... Which is the same fate as the movie in fact, if you have the chance to be "redone", you'll go from japan anime to Hollywood pimped movie...), but we can all agree about the quality of the environment and character design nonetheless. Even if conceptually, this future looks a lot like an "hyper-present" (more networks, more media, more digital, more robots, cyborgs and viruses, more hackers, etc. - that will not happen therefore).

In particular for architects, the urban design of the "Hong Kong++" (or "Blade Runner++" ) style city, full of skyscrapers sized holograms, mostly publicities. A design in a kind of strange and brutal mish-mash with more regular yet buildings. This is the quite 3d graphical work ofAsh Thorp that i link below.

Considering these different exemples, we could wonder why architectural schools don't take more into consideration these kind of works? So as the ones present in literature. Couldn't we start thinking that architecture is a field that indeed and of course, build physical spaces and cities, but not only.

So, it should also take its part in the conceptualization and design of "networked", "virtual" or rather "mixed realities" (whatever further necessary debates we could have about the understanding of those words), environments for games and movies? Possibly also by extension non material spaces in general? And of course, all the probably more interesting "in betweens"? I truly believe architectural discourse could easily consider all these aspects of architecture and widen a bit its educational scope.

But I don't see this coming so much. Do you? (there are some discussion forums on Archinect for example)

Via Kotaku

-----

Some additionnal information about the conceptual work on the movie.

Another interesting and quite "space-graphical" short anime by Ash Thorp, "Epoch" - in a slightly "2001" style-, can be accessed on his site as well. And interestingly for 3d designers, he has created with fellow industry-artists a teaching platform led by professionals: Learn Squared (they are hosting a talk about the set design on Twitch next Wednesday btw). There can you learn "UI and Data Design for Film", "3D Concept Design", "Motion Design", etc.

More works about the movie HERE (in a post by Luke Plunkett).

Wednesday, December 14. 2016

Note: Interférences dimensionnelles 1, a 3d printed work by fabric | ch, becomes part of the online gallery collection ArtJaws. This piece was created at the occasion of an exhibition in Montreal (pdf) and is now edited in a slighty different version and in a limited and certificated serie of 20 pieces. The selection of works by different artists has been curated by Ewen Chardronnet, among a larger collection.

Well... It seems it comes at the perfect time for Christmas! ;)

By fabric | ch

-----

“Cosmos of Mutual Exchanges” is the collection curated by Ewen Chardronnet for the online gallery ArtJaws.

A few words by Ewen about it:

"Throughout my journey as an author, journalist, curator and member of collectives, meeting artists has always been a chance for me to develop my knowledge and theory around speculative fields that go well beyond the fixed borders of academic reflection.

As such, while curating exhibitions, art directing festivals, coordinating residencies and directing productions, I have always sought out a relationship between art practice and theory that, rather than merely being mutually beneficial, leads to a true exchange. I have always felt more enriched working with the artists, rather than simply writing about them. For me, an exhibition is not a final goal but a platform where each player enriches their sensory knowledge and collectively participates in opening up new ways of perceiving and acting in society, faced with our accelerated world. These are the mutual cosmic exchanges that give artworks their “value”… and can help us to rethink our politics of recombinatory commons.

So I took the opportunity of this online curation to revisit a decade of collaborating with artists and to see where this new perspective on mutual exchange (with the gallery, the collector) can lead us. During these years, Slovenian artistic life has been a major source of inspiration for me, and this is expressed in the selection, which is faithful to the community spirit. (...)"

More about the collection HERE.

Regarding the work of fabric | ch in the collection, Interférences dimensionnelles 1:

Created at the occasion of an exhibition in Montreal and revisited for this edition of 20 copies, Interference Dimensionnelle 1 is as a “matrix” in scale 1: X which instantly combines the spatial, temporal or even climatic dimensions/data of actual or virtual terrestrial locations.

Athens, Brasilia, Dubai, intersection of the Arctic Circle and Antemeridian, Montreal: 37 ° 58 ‘N / 23 ° 43’ E; 15 ° 46 ‘N / 47 ° 54’ W; 25 ° 16 ‘N / 55 ° 19’ E; 66 ° 33 ‘N / 180 ° 00’ E; 45 ° 30 ‘N / 73 ° 40’ W.

Five emblematic places representative of the architectural, territorial and energetic approaches of Western society and its history, five coordinates located on a world map and then gathered. These situations, when supplemented by the”original” mark 0,0,0, form a set of six interlaced benchmarks for new contemporary spatial situations.

21 x 18 x 18 cm, transparent and black acrylic polymer, edition of 20. €1200.-

Tuesday, November 01. 2016

Note: posted a few weeks ago on It's Nice That, those pictures by photographer Philippe Jarrigeon about mazes.

Where this out of date esthetic seems nowadays quite odd, with some "Marienbad" flavour in them, with colour and combined ... of ... course ... with some "Shining"!

Via It's Nice That

-----

More about it HERE.

Tuesday, October 04. 2016

Note: j'avais évoqué récemment cette idée du sublime dans le cadre d'un workshop à l'ECAL, avec pour invités Random International. Il s'agissait alors d'intervenir dans le cadre d'un projet de recherche où nous visions à développer des "contre-propositions" à l'expression actuelle de quelques-unes de nos infrastructures contemporaines, "douces" et "dures". Le "cloud computing" et les data-centers en particulier (le projet en question, en cours et dont le processus est documenté sur un blog: Inhabiting & Interfacing the Cloud(s)). Un projet conduit en collaboration avec Nicolas Nova de la HEAD - Genève

Tout cela s'était développé autour du sentiment d'une technologie, qui mettant aujourd'hui de nouveau "à distance" ses utilisateurs, contribuerait au développement de "croyances" (dimension "magique") et dans certains cas, à la résurgence du sentiment de "sublime", cette fois non plus lié aux puissances natutrelles "terrifiantes", mais aux technologies développées par l'homme. Je n'avais pas fait le lien avec cette thématique très actuelle de l'Anthropocène, que nous avions toutefois déjà commentée et pointée sur ce blog.

C'est fait dorénavant avec beaucoup de nuances par Jean-Baptiste Fressoz. Non sans souligner que "(...) cette opération esthétique, au demeurant très réussie, n’est pas sans poser problème car ce qui est rendu sublime ce n’est évidemment pas l’humanité, mais c’est, de fait, le capitalisme".

...

On peut aussi se souvenir qu'en 1990 déjà, Michel Serres écrivait dans son livre Le Contrat Naturel:

"Voici maintenant formée la contemporaine société, qu'on peut appeler deux fois mondiale: occupant toute la terre, solidaire comme un bloc, par ses interrelations croisées, elle ne dispose d'aucun reste, de recul ni de recours, ou planter sa tente et dans quel extérieur. Elle sait, d'autre part, construire et utiliser des moyens techniques aux dimensions spatiales, temporelles, énergétiques des phénomènes du monde. Notre puissance collective atteint donc les limites de notre habitat global. Nous commençons à ressembler à la Terre."

Texte que nous avions par ailleurs cité avec fabric | ch dans l'un de nos premiers projets, Réalité Recombinée, en 1998.

Via Mouvements (via Nicolas Nova)

-----

Par Jean-Baptiste Fressoz

Olafur Eliasson à la Tate Modern.

Pour Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, la force de l’idée d’Anthropocène n’est pas conceptuelle, scientifique ou heuristique : elle est avant tout esthétique. Dans cet article, l’auteur revient, pour en pointer les limites, sur les ressorts réactivés de cette esthétique occidentale et bourgeoise par excellence [note: le sublime], vilipendée par différents courants critiques. Il souligne qu’avant d’embrasser complètement l’Anthropocène, il faut bien se rappeler que le sublime n’est qu’une des catégories de l’esthétique, qui en comprend d’autres (le tragique, le beau…) reposant sur d’autres sentiments (l’harmonie, la douleur, l’amour…), peut-être plus à même de nourrir une esthétique du soin, du petit, du local dont l’agir écologique a tellement besoin.

Aussi sidérant, spectaculaire ou grandiloquent qu’il soit, le concept d’Anthropocène ne désigne pas une découverte scientifique [1]. Il ne représente pas une avancée majeure ou récente des sciences du système-terre. Nom attribué à une nouvelle époque géologique à l’initiative du chimiste Paul Crutzen, l’Anthropocène est une simple proposition stratigraphique encore en débat parmi la communauté des géologues. Faisant suite à l’Holocène (12 000 ans depuis la dernière glaciation), l’Anthropocène est marquée par la prédominance de l’être humain sur le système-terre. Plusieurs dates de départ et marqueurs stratigraphiques afférents sont actuellement débattus : 1610 (point bas du niveau de CO2 dans l’atmosphère causé par la disparition de 90% de la population amérindienne), 1830 (le niveau de CO2 sort de la fourchette de variabilité holocénique), 1945 date de la première explosion de la bombe atomique.

La force de l’idée d’Anthropocène n’est pas conceptuelle, scientifique ou heuristique : elle est avant tout esthétique. Le concept d’Anthropocène est une manière brillante de renommer certains acquis des sciences du système-terre. Il souligne que les processus géochimiques que l’humanité a enclenchés ont une inertie telle que la terre est en train de quitter l’équilibre climatique qui a eu cours durant l’Holocène. L’Anthropocène désigne un point de non retour. Une bifurcation géologique dans l’histoire de la planète Terre. Si nous ne savons pas exactement ce que l’Anthropocène nous réserve (les simulations du système-terre sont incertaines), nous ne pouvons plus douter que quelque chose d’importance à l’échelle des temps géologiques a eu lieu récemment sur Terre.

Le concept d’Anthropocène a cela d’intéressant, mais aussi de très problématique pour l’écologie politique, qu’il réactive les ressorts de l’esthétique du sublime, esthétique occidentale et bourgeoise par excellence, vilipendée par les critiques marxistes, féministes et subalternistes, comme par les postmodernes. Le discours de l’Anthropocène correspond en effet assez fidèlement aux canons du sublime tels que définis par Edmund Burke en 1757. Selon ce philosophe anglais conservateur, surtout connu pour son rejet absolu de 1789, l’expérience du sublime est associée aux sensations de stupéfaction et de terreur ; le sublime repose sur le sentiment de notre propre insignifiance face à une nature lointaine, vaste, manifestant soudainement son omnipuissance. Écoutons maintenant les scientifiques promoteurs de l’Anthropocène :

« L’humanité, notre propre espèce, est devenue si grande et si active qu’elle rivalise avec quelques-unes des grandes forces de la Nature dans son impact sur le fonctionnement du système terre […]. Le genre humain est devenu une force géologique globale [2] ».

La thèse de l’Anthropocène repose en premier lieu sur les quantités phénoménales de matière mobilisées et émises par l’humanité au cours des XIXe et XXe siècles. L’esthétique de la gigatonne de CO2 et de la croissance exponentielle renvoie à ce que Burke avait noté : « la grandeur de dimension est une puissante cause du sublime [3] », et, ajoute-t-il, le sublime demande « le solide et les masses mêmes [4] ». De manière plus précise, l’Anthropocène reporte le sublime de la vaste nature vers « l’espèce humaine ». Tout en jouant du sublime, il en renverse les polarités classiques : la terreur sacrée de la nature est transférée à une humanité colosse géologique.

Or, cette opération esthétique, au demeurant très réussie, n’est pas sans poser problème car ce qui est rendu sublime ce n’est évidemment pas l’humanité, mais c’est, de fait, le capitalisme. L’Anthropocène n’est certainement pas l’affaire d’une « espèce humaine », d’un « anthropos » indifférencié, ce n’est même pas une affaire de démographie : entre 1800 et 2000 la population humaine a été multipliée par sept, la consommation d’énergie par 50 et le capital, si on reprend les chiffres de Thomas Picketty, par 134 [5]. Ce qui a fait basculer la planète dans l’Anthropocène, c’est avant tout une vaste technostructure orientée vers le profit, une « seconde nature », faite de routes, de plantations, de chemins de fer, de mines, de pipelines, de forages, de centrales électriques, de marchés à terme, de porte-containers, de places financières et de banques et bien d’autres choses encore qui structurent les flux de matière et d’énergie à l’échelle du globe selon une logique structurellement inégalitaire. Bref, le changement de régime géologique est bien sûr le fait de « l’âge du capital [6] » bien plus que le fait de « l’âge de l’être humain » dont nous rebattent les récits dominants [7]. Le premier problème du sublime de l’Anthropocène est qu’il renomme, esthétise et surtout naturalise le capitalisme, dont la force se mesure dorénavant à l’aune des manifestations de la première nature – les volcans, la tectonique des plaques ou les variations des orbites planétaires – que deux siècles d’esthétique du sublime nous avaient appris à craindre mais aussi à révérer.

Au sublime de la quantité, l’Anthropocène ajoute le sublime géologique des âges et des éons, duquel il tire ses effets les plus saisissants. La thèse de l’Anthropocène nous dit en substance que les traces de notre âge industriel resteront pour des millions d’années dans les archives géologiques de la planète. Le fait d’ouvrir une nouvelle époque taillée à la mesure de l’être humain signifie que c’est à l’échelle des temps géologiques seulement que l’on peut identifier des événements agissant avec autant de force sur la planète que nous-mêmes : le taux de dioxyde de carbone en 2015 est sans précédent depuis trois millions d’années, le taux actuel d’extinction des espèces, depuis 65 millions d’années, l’acidité des océans, depuis 300 millions d’années, etc. Ce que nous vivons n’est pas une simple « crise environnementale », mais une révolution géologique d’origine humaine. Loin de constituer un cours extérieur, impavide et gigantesque, le temps de la Terre est devenu commensurable au temps de l’agir humain. En deux siècles tout au plus, l’humanité a altéré la dynamique du système-terre pour l’éternité ou presque. « Tout ce qui fait transition n’excite aucune terreur [8] » écrivait Burke. Le discours de l’Anthropocène cultive cette esthétique de la soudaineté, de la bifurcation et de l’événement. Le sublime de l’Anthropocène réside précisément dans cette rencontre extraordinaire : deux siècles d’activité humaine, une durée infime, quasi-nulle au regard de l’histoire terrienne, auront suffi à provoquer une altération comparable au grand bouleversement de la fin du Mésozoïque il y a 65 millions d’années.

La troisième source du sublime anthropocénique est le sublime de la violence souveraine de la nature, celle des tremblements de terre, des tempêtes et des ouragans. Les promoteur·rice·s de l’Anthropocène mobilisent volontiers le sublime romantique des ruines, des civilisations disparues et des effondrements : « Les moteurs de l’Anthropocène pourraient bien menacer la viabilité de la civilisation contemporaine et peut-être même l’existence d’homo sapiens [9] ». Le succès artistique et médiatique du concept repose sur la « jouissance douloureuse », sur le « plaisir négatif » dont parle Burke :

« Nous jouissons à voir des choses que, bien loin de les occasionner, nous voudrions sincèrement empêcher… Je ne pense pas qu’il existe un·e ho·femme assez scélérat·e· pour désirer [que Londres] fût renversée par un tremblement de terre… Mais supposons ce funeste accident arrivé, quelle foule accourrait de toute part pour contempler ses ruines [10] ».

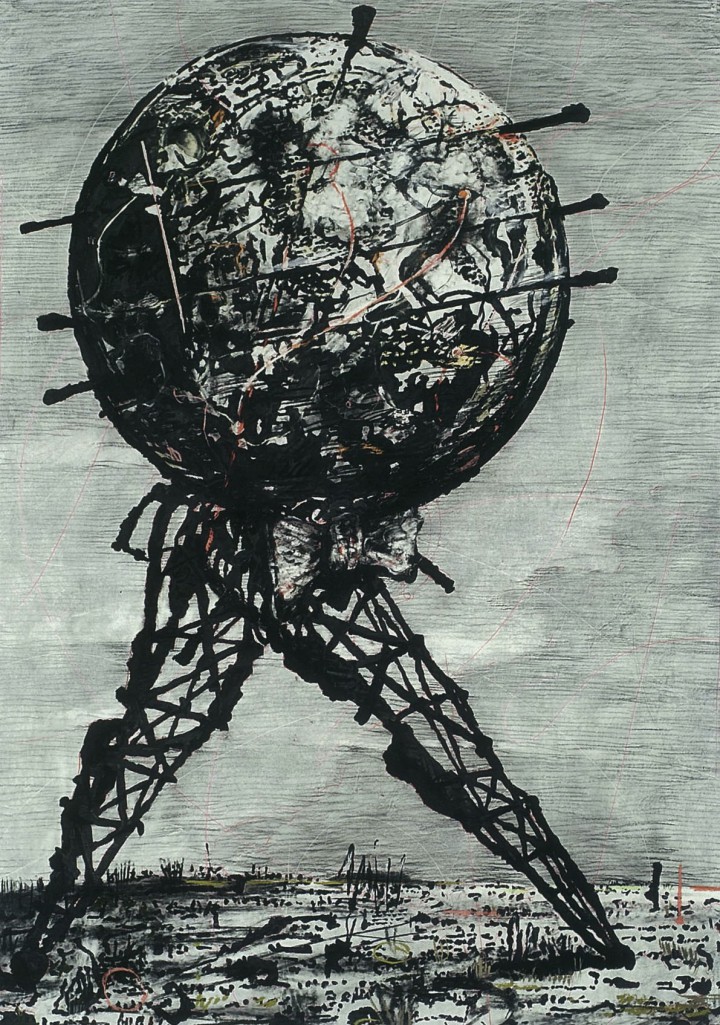

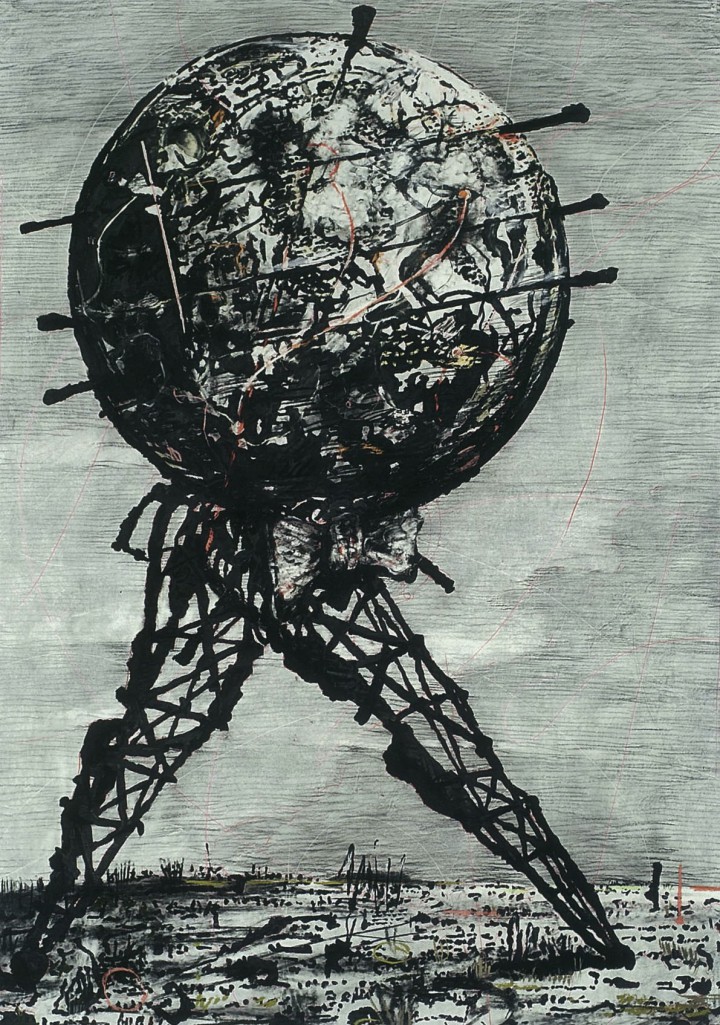

William Kentridge

L’Anthropocène s’appuie sur une culture de l’effondrement propre aux nations occidentales, qui, depuis deux siècles, admirent leur puissance en fantasmant les ruines de leur futur. L’Anthropocène joue des mêmes ressorts psychologiques que le plaisir pervers des décombres déjà décrit par Burke et qui nourrit la vogue actuelle du tourisme des catastrophes de Tchernobyl à ground zero.

La violence de l’Anthropocène est aussi celle de la science hautaine et froide qui nomme les époques et définit notre condition historique. Violence, tout d’abord, de son diagnostic irrévocable : « toi qui entre dans l’Anthropocène abandonne tout espoir » semblent nous dire les savant·e·s. Violence ensuite de la naturalisation, de la « mise en espèce » des sociétés humaines : les statistiques globales de consommation et d’émissions compactent les mille manières d’habiter la terre en quelques courbes, effaçant par la même l’immense variation des responsabilités entre les peuples et les classes sociales. Violence enfin du regard géologique tourné vers nous-mêmes, jaugeant toute l’histoire (empires, guerres, techniques, hégémonies, génocides, luttes, etc.) à l’aune des traces sédimentaires laissées dans la roche. Le géologue de l’Anthropocène est plus effroyable encore que l’ange de l’histoire de Walter Benjamin qui, là même où nous voyions auparavant progrès, ne voyait que catastrophe et désastre : lui n’y voit que fossiles et sédiments.

Que le sublime soit l’esthétique cardinale de l’Anthropocène n’est absolument pas fortuit : sublime et géologie se sont épaulés tout au long de leur histoire. En 1674, Nicolas Boileau traduit en français le traité de Longinus sur le sublime (1er siècle après J.-C.) introduisant ainsi cette notion dans l’Europe lettrée. Mais c’est seulement au milieu du XVIIIe siècle, après que la passion des montagnes et l’intérêt pour la géologie se sont cristallisés dans les classes supérieures, que la « grande nature » devient un objet de sublime [11]. Partis pour leur « grand tour », sur le chemin de l’Italie, les jeunes Anglais·es fortuné·e·s rencontrent en effet la chaîne des Alpes, ses pics vertigineux, ses glaciers terrifiants et ses panoramas immenses. Dans les récits de grands tours, l’expérience de l’effroi face à la nature représente le prix à payer pour goûter la beauté des trésors culturels de l’Italie. Le sublime joue ici un rôle de distinction : être capable de prendre du plaisir en contemplant les glaciers, ou les rochers arides, permettait aux touristes anglais·es de se différencier des guides et des paysan·e·s montagnard·e·s qui n’y voyaient que dangers et terres incultes. Mais c’est évidemment le tremblement de terre de Lisbonne de 1755 qui fournit le véritable coup d’envoi des réflexions sur le sublime : Burke, qui publie son traité l’année suivante, fait référence à la passion esthétique des décombres et des ruines qui saisit alors l’Europe entière. La même année, Emmanuel Kant publie également un court ouvrage sur le tremblement de terre de Lisbonne et, dans son essai ultérieur sur le sublime, il définit ce dernier comme un « plaisir négatif » pouvant procéder de deux manières : le sublime mathématique ressenti devant l’immensité de la nature (l’espace étoilé, l’océan etc.) et le « sublime dynamique » procuré par la violence de la nature (tornade, volcan, tremblement de terre).

Le sublime de l’Anthropocène, et sa mise en scène d’une humanité devenue force tellurique signe la rencontre historique du sublime naturel du XVIIIe siècle et du sublime technologique des XIXe et XXe siècles. Avec l’industrialisation de l’Occident, la puissance de la seconde nature fait l’objet d’une intense célébration esthétique. Le sublime transféré à la technique jouait un rôle central dans la diffusion de la religion du progrès : les gares, les usines et les gratte-ciels en constituaient les harangues permanentes [12]. Dès cette époque, l’idée d’un monde traversé par la technique, d’une fusion entre première et seconde natures fait l’objet de réflexions et de louanges. On s’émerveille des ouvrages d’art matérialisant l’union majestueuse des sublimes naturel et humain : viaducs enjambant les vallées, tunnels traversant les montagnes, canaux reliant les océans, etc. L’idée d’un globe remodelé pour les besoins de l’être humain et fertilisé par la technique constitue une trope classique du positivisme depuis Saint-Simon au moins, qui, dès 1820, écrivait :

« l’objet de l’industrie est l’exploitation du globe, c’est-à-dire l’appropriation de ses produits aux besoins de l’homme, et comme, en accomplissant cette tâche, elle modifie le globe, le transforme, change graduellement les conditions de son existence, il en résulte que par elle, l’homme participe, en dehors de lui-même en quelque sorte, aux manifestations successives de la divinité, et continue ainsi l’œuvre de la création. De ce point de vue, l’Industrie devient le culte [13] ».

De manière plus précise, l’Anthropocène s’inscrit dans une version du sublime technologique reconfigurée par la guerre froide. Il prolonge la vision spatiale de la planète produite par le système militaro-industriel américain, une vision déterrestrée de la Terre saisie depuis l’espace comme un système que l’on pourrait comprendre dans son entièreté, un « spaceship earth » dont on pourrait maîtriser la trajectoire grâce aux nouveaux savoirs sur le système-terre [14]. Le risque est que l’esthétique de l’Anthropocène nourrisse davantage l’hubris d’une géo-ingénierie brutale qu’un travail patient, à la fois modeste et ambitieux d’involution et d’adaptation du social. Pour mémoire, la géo-ingénierie désigne un ensemble de techniques visant à modifier artificiellement le pouvoir réfléchissant de l’atmosphère terrestre pour contrecarrer le réchauffement climatique. Cela peut constituer par exemple à injecter du dioxyde de soufre dans la haute atmosphère afin de réfléchir une partie du rayonnement solaire vers l’espace. L’échec des gouvernements à obtenir un accord international contraignant et ambitieux a contribué à mettre en avant la géo-ingénierie, en tant que « plan B ». Ces techniques potentiellement très risquées pourraient donc soudainement s’imposer en cas « d’urgence climatique ».

Pour ses promoteur·rice·s, l’Anthropocène est une révélation, un éveil, un changement de paradigme désorientant soudainement les représentations vulgaires du monde.

« Par le passé, du fait de la science, l’humanité a dû faire face à de profondes remises en cause de leurs systèmes de croyance. Un des exemples les plus important est la théorie de l’évolution… Le concept d’anthropocène pourrait susciter une réaction hostile similaire à celle que Darwin a produite [15] ».

On retrouve ici le trope romantique du·de la savant·e· payant de sa personne pour lutter contre la foule hostile. En se coupant ainsi du passé et de la décence environnementale commune, en rejetant comme dépassés les savoirs environnementaux qui le précèdent ainsi que les luttes sociales que ces savoirs ont nourries, l’Anthropocène dépolitise l’histoire longue de la destruction de la planète. Avant on ignorait les conséquences globales de l’agir humain, maintenant l’on sait, et, bien entendu, maintenant l’on peut agir. La prétention à la nouveauté des savoirs sur la Terre est aussi une prétention des savants à agir sur celle-ci. Ce n’est pas un hasard si l’inventeur du mot Anthropocène, le prix Nobel de chimie Paul Crutzen, est aussi l’un des avocat·e·s des techniques de géo-ingénierie. À l’Anthropocène inconscient issu de la révolution industrielle succéderait enfin le « bon Anthropocène » éclairé par les savoirs du système-terre. Comme toute forme de scientisme, l’esthétique de l’Anthropocène anesthésie le politique : les « expert·e·s », les autorités vont « faire quelque chose ».

Les expériences du sublime sont toujours à replacer dans un contexte historique et politique particulier. Elles renvoient à des émotions dépendantes des conditions culturelles, naturelles ou technologiques de chaque époque et ce sont ces conditions qui en fournissent les clés de compréhension politique. De la fin du XVIIIe siècle à la fin du siècle suivant, le sublime d’une nature violente et abstraite permettait aux classes bourgeoises urbaines de goûter à la violence de la nature, tout en étant relativement protégées de ses manifestations et de relativiser les dangers bien réels d’un mode de vie technologique et urbain. L’art du sublime nourrissait également le fantasme d’une nature immense et inépuisable au moment précis où l’impérialisme en exploitait les derniers recoins. Dans une culture prenant au sérieux le projet de maîtrise technique de la nature, l’esthétique du sublime fournissait aussi un plaisir légèrement coupable. Enfin, selon le critique marxiste Terry Eagleton, le sublime correspondait aux impératifs esthétiques du capitalisme naissant : contre l’esthétique émolliente du beau, risquant de transformer le sujet bourgeois en sensualiste décadent, le sublime réénergisait le sujet capitaliste comme exploiteur·se ou comme pourvoyeur de travail. Le beau devient à la fin du XVIIIe siècle l’harmonieux, le non-productif, le doux et le féminin ; le sublime : l’effort, le danger, la souffrance, l’élevé, le majestueux et le masculin. Au fond, le sublime, nous dit Eagleton, contenait la menace que la beauté faisait peser sur la productivité [16].

Au début des années 2000, le sublime de l’Anthropocène occupe également une fonction idéologique. Alors que les classes intellectuelles se convertissent au souci écologique, alors qu’elles rejettent les idéaux modernistes de maîtrise de la nature comme has been, alors qu’elles proclament « la fin des grands récits », la fin du progrès, de la lutte des classes, etc., l’Anthropocène procure le frisson coupable d’un nouveau récit sublime. Sur un fond d’agnosticisme quant au futur, l’Anthropocène paraît donner un nouvel horizon grandiose à l’humanité tout entière : prendre en charge collectivement le destin d’une planète. Dans le contexte idéologique terne de l’écologie politique, du développement durable et de la précaution, penser le mouvement d’une humanité devenue force tellurique paraît autrement plus excitant que penser l’involution d’un système économique. Au fond le sublime de l’Anthropocène rejoue assez exactement la scène finale du chef-d’œuvre de Stanley Kubrick, 2001 l’Odyssée de l’espace : l’embryon stellaire contemplant la terre figurant parfaitement l’avènement d’un agent géologique conscient, d’un corps planétaire réflexif. Et c’est bien pour cela que l’Anthropocène fait tressaillir théoricien·ne·s, philosophes et artistes en herbe : il semble désigner un événement métaphysique intéressant.

Pour l’écologie politique contemporaine, l’esthétique sublime de l’Anthropocène pose pourtant problème : en mettant en scène l’hybridation entre première et seconde natures, elle réénergise l’agir technologique des cold warriors (la géo-ingénierie) ; en déconnectant l’échelle individuelle et locale de ce qui importe vraiment (l’humanité force tellurique et les temps géologiques), elle produit sidération et cynisme (no future) ; enfin l’Anthropocène, comme tout autre sublime, est sujet à la loi des rendements décroissants : une fois que l’audience est préparée et conditionnée, son effet s’émousse. En ce sens, désigner une œuvre d’art comme « art de l’Anthropocène » serait absolument fatale à son efficacité esthétique. Le risque est que l’écologie du sublime soit alors appelée à une surenchère permanente, semblable en cela à la course à l’avant-garde dans l’art contemporain. Avant d’embrasser complètement l’Anthropocène, il faut bien se rappeler que le sublime n’est qu’une des catégories de l’esthétique, qui en comprend bien d’autres (le tragique, le beau, le pittoresque…) reposant sur d’autres sentiments (l’harmonie, l’ataraxie, la tristesse, la douleur, l’amour), qui sont peut-être plus à même de nourrir une esthétique du soin, du petit, du local, du contrôle, de l’ancien et de l’involution dont l’agir écologique a tellement besoin.

[1] Cet article reprend sous une forme modifiée un texte déjà paru dans le catalogue de l’exposition Sublime. Les tremblements du monde, Centre Pompidou-Metz, Metz, Centre Pompidou-Metz, 2016.

[2] W. Steffen, J. Grinevald, P. Crutzen, J. McNeill, « The Anthropocene : conceptual and historical perspectives », Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society A, 369, 2011, p. 842–867.

[3] E. Burke, Recherche philosophique sur l’origine de nos idées du sublime et du beau, Paris, Pichon, 1803 (1757), p. 129.

[4] Ibid., p. 225.

[5] T. Piketty, Le capital au XXIe siècle, Paris, Seuil, 2013.

[6] E. Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital : 1848-1975, London, Weindefeld, 1975.

[7] Voir le chapitre « capitalocène » de la nouvelle édition de C. Bonneuil, J.-B. Fressoz, L’événement Anthropocène. La terre, l’histoire et nous, Paris, Seuil, 2016.

[8] E. Burke, op. cit. p. 151.

[9] W. Steffen et al., art. cit.

[10] E. Burke, op. cit., p. 85.

[11] M. Hope Nicholson, Mountain gloom and mountain glory: The development of the aesthetics of the infinite, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1959.

[12] D. Nye, American technological sublime, Cambridge (MA), MIT Press, 1994.

[13] Saint-Simon, Doctrine de Saint-Simon, t. 2, Paris, Aux Bureaux de l’Organisateur, 1830, p. 219.

[14] C. Bonneuil, J.-B. Fressoz, op. cit. ; S. Grevsmühl, La Terre vue d’en haut. L’invention de l’environnement global, Paris, Seuil, 2014.

[15] W. Steffen et al., art. cit.

[16] Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic, Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1990.

Thursday, July 28. 2016

Note: not only photography is affected by digitizing, of course... residency and citizenship as well. In a different way than one could expect. "Crypto-residency" to come soon to help you invest your cryptocurrencies in a "crypto-land"?

Will "Brexiters" apply, cynically?

Via MIT technology Review

-----

By Nanette Byrnes

Estonia aims to bring 10 million people to its digital shores.

With 1.3 million citizens, Estonia is one of the smallest countries in Europe, but its ambition is to become one of the largest countries in the world. Not one of the largest geographically or even by number of citizens, however. Largest in e-residents, a category of digital affiliation that it hopes will attract people, especially entrepreneurs.

Started two years ago, e-residency gives citizens of any nation the opportunity to set up Estonian bank accounts and businesses that use a verified digital signature and are operated remotely, online. The program is an outgrowth of a digitization of government services that the country launched 15 years ago in a bid to save money on the staffing of government offices. Today Estonians use their mandatory digital identity to do everything from track their medical care to pay their taxes.

Now the country is marketing e-residency as a path by which any business owner can set up and run a business in the European Union, benefiting from low business costs, digital bureaucratic infrastructure, and in certain cases, from the country’s low tax rates.

“If you want to run a fully functional company in the EU, in a good business climate, from anyplace in the world, all you need is an e-residency and a computer,” says Estonian prime minister Taavi Rõivas.

Tallinn, capital city of Estonia

Things that don’t come with e-residency include a passport and citizenship. Nor do e-residents automatically owe taxes to the country, though digital companies that incorporate there and obtain a physical address can benefit from the country’s low tax rate. The chance to run a business out of Estonia has proven popular enough that almost 700 new businesses have been set up by the nearly 1,000 new e-residents, according to statistics from the government.

The government hopes to have 10 million e-residents by 2025, though others think that goal is a stretch.

Estonian officials describe e-residency as an early step toward a mobile future, one in which countries will compete for the best people. And they are not the only ones pursing this idea. Payment company Stripe recently launched a program called Atlas that it hopes will boost the number of companies using its services to accept payments. It helps global Internet businesses incorporate in the state of Delaware, open a bank account, and get tax and legal guidance.

Juan Pablo Vazquez Sampere, a professor at Madrid’s IE Business School, sees the Estonia program as enabling global entrepreneurs to operate in Europe at a fraction of the cost of living in the region.

Last year, Arvind Kumar, an electrical engineer who lives just outside Mumbai, left his 30-year-career in the steel industry to start Kaytek Solutions OÜ, which creates models to improve manufacturing quality and efficiency. Last September Kumar flew to Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, and spent half a day setting up a bank account and a virtual office. In addition to the price of the trip, initial setup costs were around $3,300 (€3,000), and he has ongoing expenses of about $480 (€440) a year. The Indian system of setting up a new business is “tedious” by contrast, says Kumar—time-consuming, difficult, and expensive.

Cost was also a factor for Vojkan Tasic, chairman of a high-end car service company called Limos4, in his decision to pick Estonia as a new home for the company. Started in his home country of Serbia six years ago, Limos4 has been paying credit-card processing fees of 7 percent. Limos4 operates in 20 large European cities as well as Dubai and Istanbul, and counts Saudi Arabian and Swedish royalty and U.S. and European celebrities among its clients.

After considering Delaware and Ireland, Tasic chose Estonia, where he can settle his credit-card transactions through PayPal subsidiary Braintree for 2.9 percent and where there is no tax on corporate profits so long as they remain invested in the business. Since getting his e-residency and moving the company to Estonia, profits are up 20 percent, Tasic says. Annual revenue is around $2 million.

For Estonia, the financial benefit comes from the fees e-residents pay to the government and the tax revenue local support services like accountants and law firms make.

To Tasic, who runs background checks on all his drivers, one of the best things about the e-residency is the fact that the Estonian police investigate every applicant. Since Kumar set up his company, Estonia has begun allowing e-residents to set up their bank accounts online, but there remains a level of security, because to pick up their residency card, applicants must go in person to one of Estonia’s 39 embassies around the world and prove their identity.

Some have raised concerns that the e-residence might attract shady characters who could shield themselves from prosecution and possible punishment by doing business in Estonia but residing outside of its jurisdiction. But with no serious cases of fraud or illicit activity to date, it is unclear whether this is a serious concern, says Karsten Staehr, a professor of international and public finance at Tallinn University of Technology.

As with any digital system, security is a major concern. Estonia, which sits just to the west of Russia and south of the Gulf of Finland, recently announced plans to back up much of its data, including banking credentials, birth records, and critical government information, in the United Kingdom.

In 2007 the country suffered a sustained denial-of-service cyberattack linked to Russia after moving a Soviet war memorial from Tallinn city center and has run a distributed system for some time with data centers in every embassy in the world.

“I am convinced they are doing a good job,” says Tasic, who holds a PhD in information services. “But with increased attention, the attacks will increase, so let’s see what the future is.”

Monday, February 15. 2016

Note: we are --like many others I guess-- very interested in the work of Carribean writer Édouard Glissant here at the studio (fabric | ch). Concepts like "archipelagic thinking", "rhizomic identity", "Tout-Monde" (could be imperfectly translated as "Whole-World") and of course "creolization" are powerful yet poetic and positive tools to understand our interleaved world and possibly envision ways of action.

I recently followed a link posted by Nicolas Nova which drived me to a channel on Youtube (managed by Laure Braeckman) that gather different sources/talks by E. Glissant and where he speaks about the different concets that structure his thinking.

Below is the link to this resource that might be useful when you'll like to discover or come back to these ideas.

-----

By Laure Braeckman

"Imaginaire du monde" / "Tout-Monde" / "Imaginaire poétique" / "Pensée de l'opacité" / "Pensée archipélique" / Marronage" / "Trois étapes de la Relation" / "Identité rhizome" / "Négritude" / "Métissage" / "Europe en archipel" / ... and many more ...

by Édouard Glissant.

Thursday, January 28. 2016

Note: I'll move this afternoon to Grandhotel Giessbach (sounds like a Wes Anderson movie) to present later tonight the temporary results of the research I'm jointly leading with Nicolas Nova for ECAL & HEAD - Genève, in partnership with EPFL-ECAL Lab & EPFL: Inhabiting and Interfacing the Cloud(s). Looking forward to meet the Swiss design research community (mainly) at the hotel...

Via iiclouds.org

-----

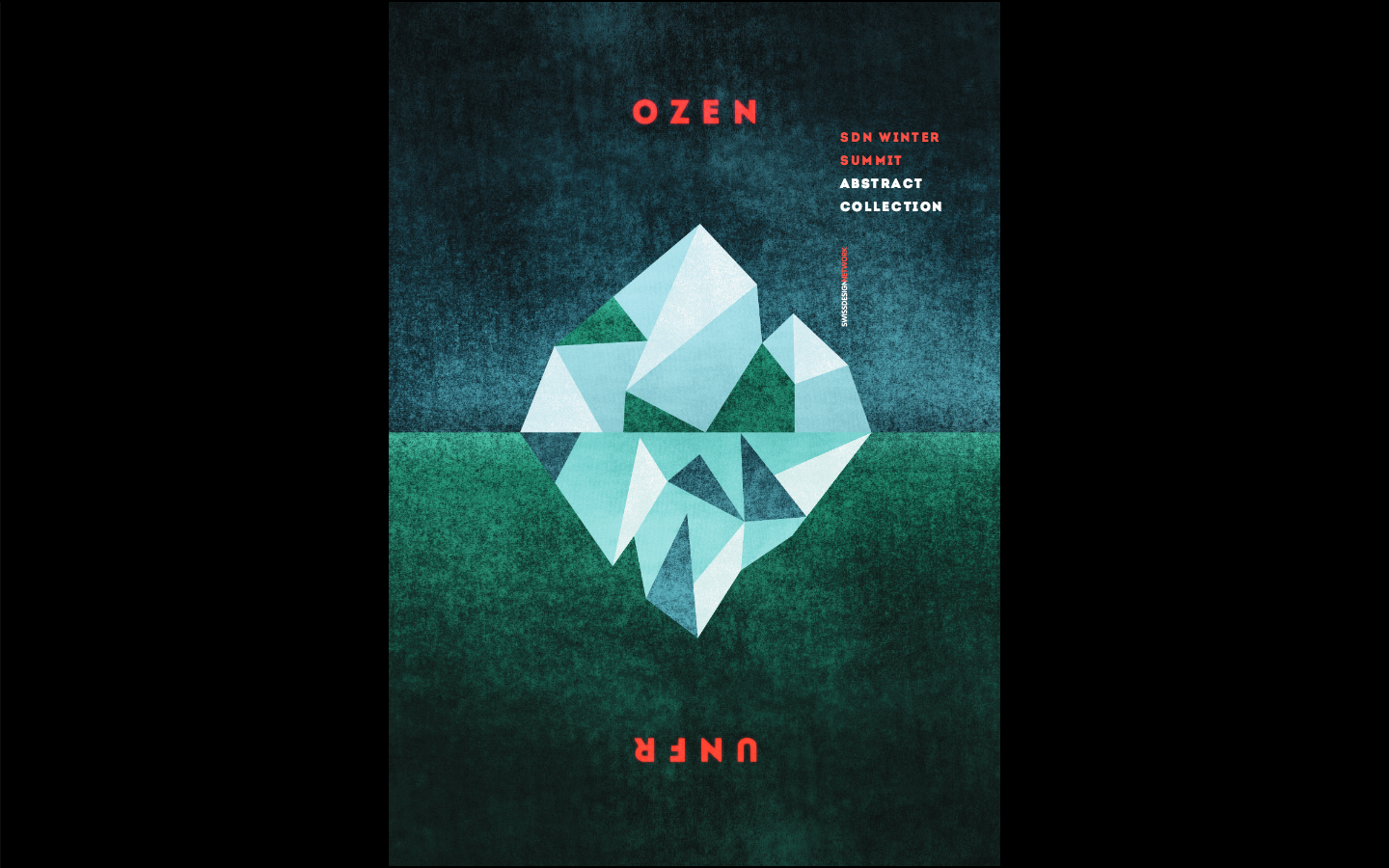

Christophe Guignard and myself will have the pleasure to present the temporary results of the design research Inhabiting & Interfacing the Cloud(s) next Thursday (28.01.2016) at the Swiss Design Network conference.

The conference will happen at Grandhotel Giessbach over the lake Brienz, where we'll focus on the research process fully articulated around the practice of design (with the participation of students in the case of I&IC) and the process of project.

This will apparently happen between "dinner" and "bar", as we'll present a "Fireside Talk" at 9pm. Can't wait to do and see that...

The full program and proceedings (pdf) of the conference can be accessed HERE.

As for previous events, we'll try to make a short "follow up" on this documentary blog after the event.

Monday, November 23. 2015

Note: this article was published a while ago and was rebloged here and there already. I kept it in my pile of "interesting articles to read later when I'll have time" for a long time as well therefore. But it make sense to post it in conjunction with the previous one about Norman Foster and by extension with the otehr one concerning the Chicago Biennial.

It is also sometimes interesting to read posts with delay, when the hype and buzzwords are gone. Written in the aftermath of the Tesla annoncement about its home battery (Powerwall), the article was all about energy revolution. But since then, what? We're definitely looking forward...

Via Gizmodo

-----

By Annalee Newitz

Photo: SpaceX

Nobody wants to say it outright, but the Apple Watch sucks. So do most smartwatches. Every time I use my beautiful Moto 360, its lack of functionality makes me despair. But the problem isn’t our gadgets. It’s that the future of consumer tech isn’t going to come from information devices. It’s going to come from infrastructure.

That’s why Elon Musk’s announcements of the new Tesla battery line last night were more revolutionary than Apple Watch and more exciting than Microsoft’s admittedly nifty HoloLens. Information tech isn’t dead — it has just matured to the point where all we’ll get are better iterations of the same thing. Better cameras and apps for our phones. VR that actually works. But these are not revolutionary gadgets. They are just realizations of dreams that began in the 1980s, when the information revolution transformed the consumer electronics market.

But now we’re entering the age of infrastructure gadgets. Thanks to devices like Tesla’s household battery, Powerwall, electrical grid technology that was once hidden behind massive barbed wire fences, owned by municipalities and counties, is now seeping slowly into our homes. And this isn’t just about alternative energy like solar. It’s about how we conceive of what technology is. It’s about what kinds of gadgets we’ll be buying for ourselves in 20 years.

It’s about how the kids of tomorrow won’t freak out over terabytes of storage. They’ll freak out over kilowatt-hours.

Beyond transforming our relationship to energy, though, the infrastructure age is about where we expect computers to live. The so-called internet of things is a big part of this. Our computers aren’t living in isolated boxes on our desktops, and they aren’t going to be inside our phones either. The apps in your phone won’t always suck you into virtual worlds, where you can escape to build treehouses and tunnels in Minecraft. Instead, they will control your home, your transit, and even your body.

Once you accept that the thing our ancestors called the information superhighway will actually be controlling cars on real-life highways, you start to appreciate the sea change we’re witnessing. The internet isn’t that thing in there, inside your little glowing box. It’s in your washing machine, kitchen appliances, pet feeder, your internal organs, your car, your streets, the very walls of your house. You use your wearable to interface with the world out there.

It makes perfect sense to me that a company like Tesla could be at the heart of the new infrastructure age. Musk’s focus has always been relentlessly about remolding the physical world, changing the way we power our transit — and, with SpaceX, where future generations might live beyond Earth. The opposite of cyberspace is, well, physical space. And that’s where Tesla is taking us.

But in the infrastructure age, physical space has been irrevocably transformed by cyberspace. Now we use computers to experience the world in ways we never could before computer networks and data analysis, using distributed sensor devices over fault lines to give people early warnings about earthquakes that are rippling beneath the ground — and using satellites like NASA’s SMAP to predict droughts years before they happen.

Of course, there are the inevitable dangers that come with infusing physical space with all the vulnerabilities of cyberspace. People will hack your house; they’ll inject malicious code into delivery drones; stealing your phone might become the same thing as stealing your car. We’ll still be mining unsustainably to support our glorious batteries and photovoltaics and smart dance clubs.

But we will also benefit enormously from personalizing the energy grid, creating a battery-powered hearth for every home. Plus the infrastructure age leads directly into outer space, to tackle big problems of human survival, and diverts our impoverished attention spans from gazing neurotically at the social scene unfolding in tiny glowing rectangles on our wrists.

The information age brought us together, for better or worse. It allowed us to understand our environment and our bodies in ways we never could before. But the infrastructure age is what will prevent us from killing ourselves as we grow up into a truly global civilization. That is far more important, and exciting, than any gold watch could ever be.

Thursday, August 06. 2015

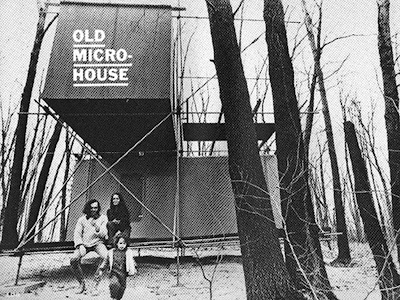

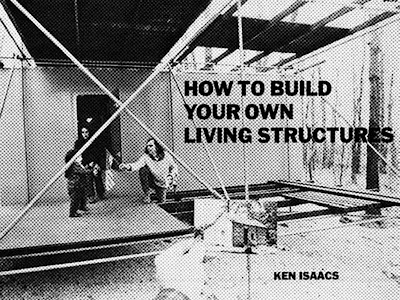

Note: we remain in history for a little more time... It's now Ken Isaacs' turn to be praised for his work around micro inhabitable spaces and living structures! I post this with the iodea in mind that his work could serve as reference for a future workshop next November at ECAL, probably with rAndom International as guests and when we'll continue to work around "cloud computing" and its infrastructure (datacenter), looking for counter-proposals or rather "counter-designs".

Via Object Guerilla

-----

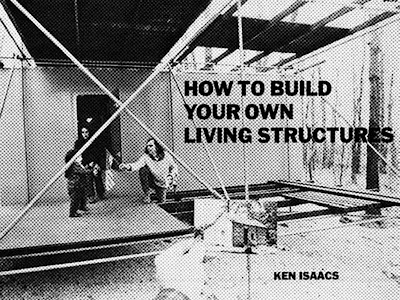

This week at work I picked up an old book, How to Build Your Own Living Structures, by Ken Isaacs, to read at lunch. I didn't finish it, so I brought it home. A little internet-ing revealed this book was out-of-print, rare, and selling for a good bit at various outlets. However, I think the copyright has lapsed, because it is available online as a PDF.

Isaacs was born in 1927 in Peoria, Illinois, and served in the military as a young man. After Korea, he studied architecture, and then began to craft a career as a designer, architect, and educator. In the late fifties, he became Head of Design at the Cranbrook Academy of Arts, birthplace of much notable mid-century modernism, including Eliel and Eero Saarinen Charles and Ray Eames, and Harry Weese. He also spent some time teaching at the Illinois Institute of Technology, founded by Mies van der Rohe as a sort of Bauhaus West.

During an itinerant period in the sixties, Isaacs began to develop what he called a Matrix system for home furnishing. He theorized (rightly and wrongly) that most of the interior volume of our homes and apartments lay unused, as most furniture only inhabits the 2-D floor plane. In his own words: "traditional furniture was never organized as a whole system. the pieces were a bunch of separate, unrelated objects determined by inertia & sentiment. feeble efforts were made to organize them "visually", but that was always just another trap. the old culture has always tried to make the unworkable endurable by overlaying it with whichever "good taste" is going at the moment. unfortunately this is like trying to make airplanes look like birds. that never worked either. that's because you can't make feathers out of aluminum." (p. 35 Liberated Space) Spoken like one fierce guerilla.

Cover, via Pop-Up City.

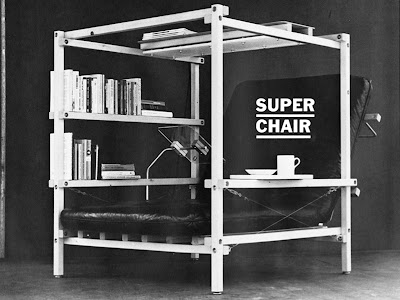

In order to conserve floor space and create flexible environments (somewhere between furniture and building) he and his wife put together matrices of 48" cubes made of 2" x 2" structural members. Each 2" x 2" was drilled with a regular pattern of holes, which allowed them to be bolted together in various configurations, accept accessories, and be disassembled. The basic idea, an Erector set for adults, has now been commercialized as "grid beams".

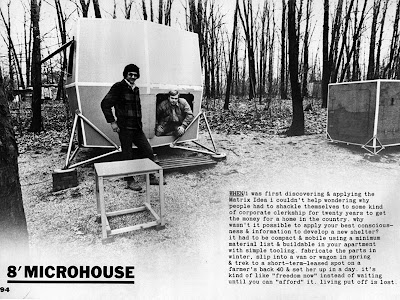

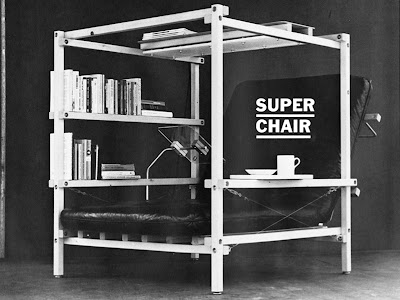

Matrix-based "super chair." Nowadays, most of that stuff can be replaced with an iPad... The next iterative leap in the Matrix was to do away with the framing altogether. Isaacs developed rigid stress-skin structures, using plywood and "L" brackets to make cubes. The cubes were built in modules: 16", 24", and eventually, 48". Smaller units were used for storage; mid-size ones could serve as desks and chairs; and the large units became the first Micro-Houses.

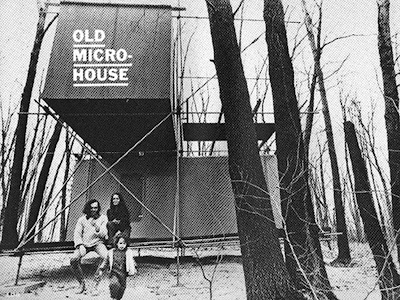

Today's term of art is "tiny house". The recession, amongst other converging trends, has exploded the popularity of tiny houses. These shelters are usually sub-500 square feet and built on trailers or temporary foundations, allowing them to escape most building codes and zoning regulations. Architecturally, most tiny houses seem to be shrunken big houses, resulting in a riotously cute dollhouse effect, like a Thomas Kinkaide painting come to life.

The Micro-House, circa late 60s, via Pop-Up City. Isaacs had the same idea, but he designed a modular, flat-pack, lightweight, re-configurable system. Combining the original beam-based Matrix and the stud-less panel structures, he built 8-foot modules out of 1" steel pipe and inserted plywood volumes into the matrix. Taking the classic modernist approach -- divorcing structure and skin -- he came up with a cheap, versatile house. The First Microhouse, built with a Graham Foundation grant in Groveland, Illinois, (near Carbondale, home of fellow light structure pioneer Buckminster Fuller), looks dated in the photos, but also startlingly fresh. I love the raw, stark geometry of it, everything stripped down to the margins.

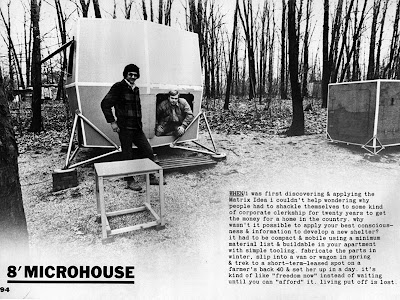

Another variation on the Microhouse -- it is infinitely reconfigurable. His 8' Microhouse is very of its era, but has nonetheless managed to inspire at least one modern imitator, in Glasgow. It creates an 8' volume based on a matrix of eight 4' volumes bolted together. The canted sides, tetrahedral feet, and hatch doors give it a real Apollo feel, minus the silvery skin.

The plywood stress-skin Microhouse. Throughout, wrapped in some seventies slang and general architectural hooliganism, Isaacs stresses pre-fabrication, modularity, simplicity, and off-the-shelf parts. None of the projects are particularly difficult to make with simple tools(a little time-consuming, perhaps). The book itself is a bit shambling, combining personal narrative, philosophical inquiry, and DIY instructions. In many ways, it seems like a blog, written with no caps and little editing. Some of the book sale listings I found online show the original as spiral-bound, in keeping with its guerilla nature.

It seems many of his designs were waiting for the technology to catch up. I was struck by the fact that everything in the book is very suited to modern micro-production techniques. With a stack of plywood and a CNC machine, you could be manufacturing flat-pack Micro-Houses on demand. A laser cutter could churn out his storage Matrix, and a MakerBot could very well print 3-axis connectors for steel pipe.

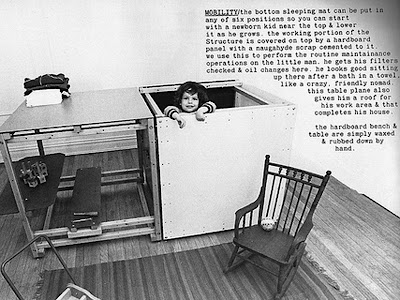

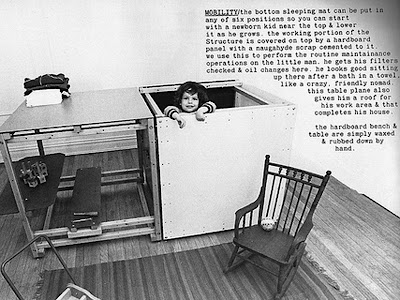

I'll end with a story from Isaacs, about getting a crib for his two year-old son. I often feel the same way: why buy when you can make?

"trouble in eden. one day i found myself in a suburban department store hallucinating Carole asking the lady if she could buy a crib. this immediately induced hyperventilation into my system & i got ready to demonstrate new audio highs for the very proper audience of clerks and matrons. together we managed a fair Wagnerian racket.

There was no other choice though. so we got the nifty crib & it hung there for quite a while like the albatross, a reminder of a monstrous negative act. it sure got us on for his Structure, though." (p. 43 Crisis and the Shoemaker's Child)

They were eventually able to replace the department-store albatross with this number.

Friday, June 26. 2015

By fabric | ch

-----

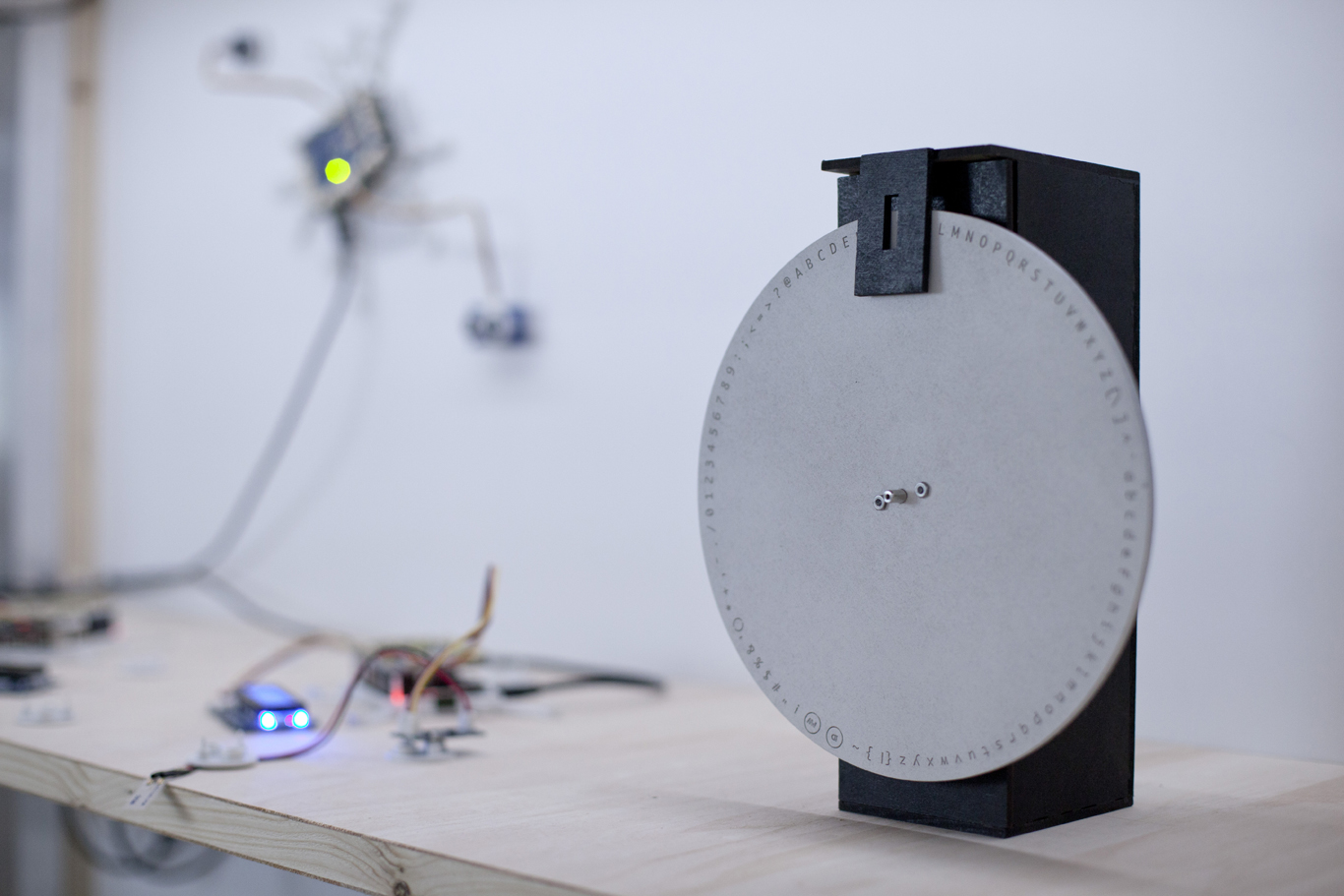

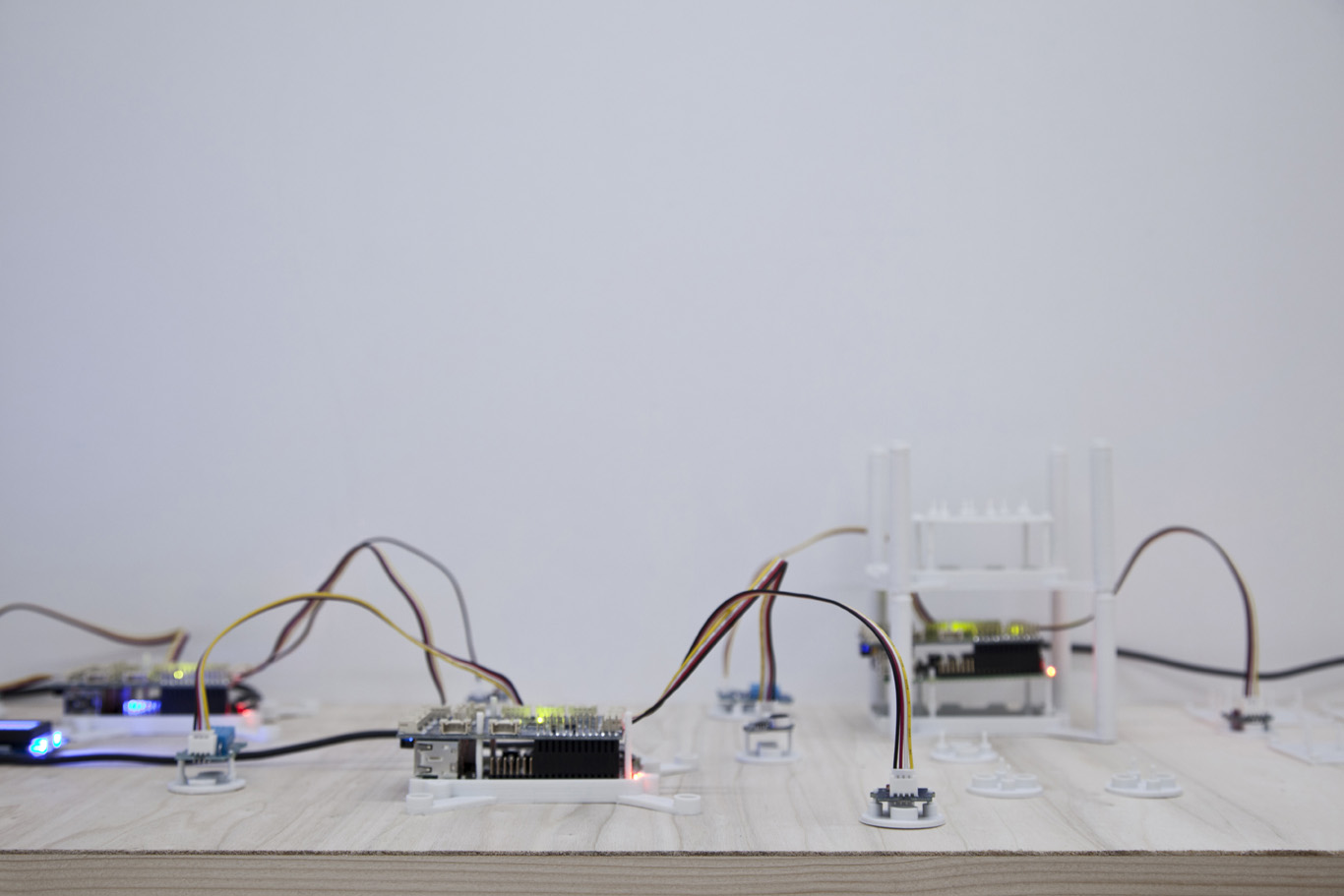

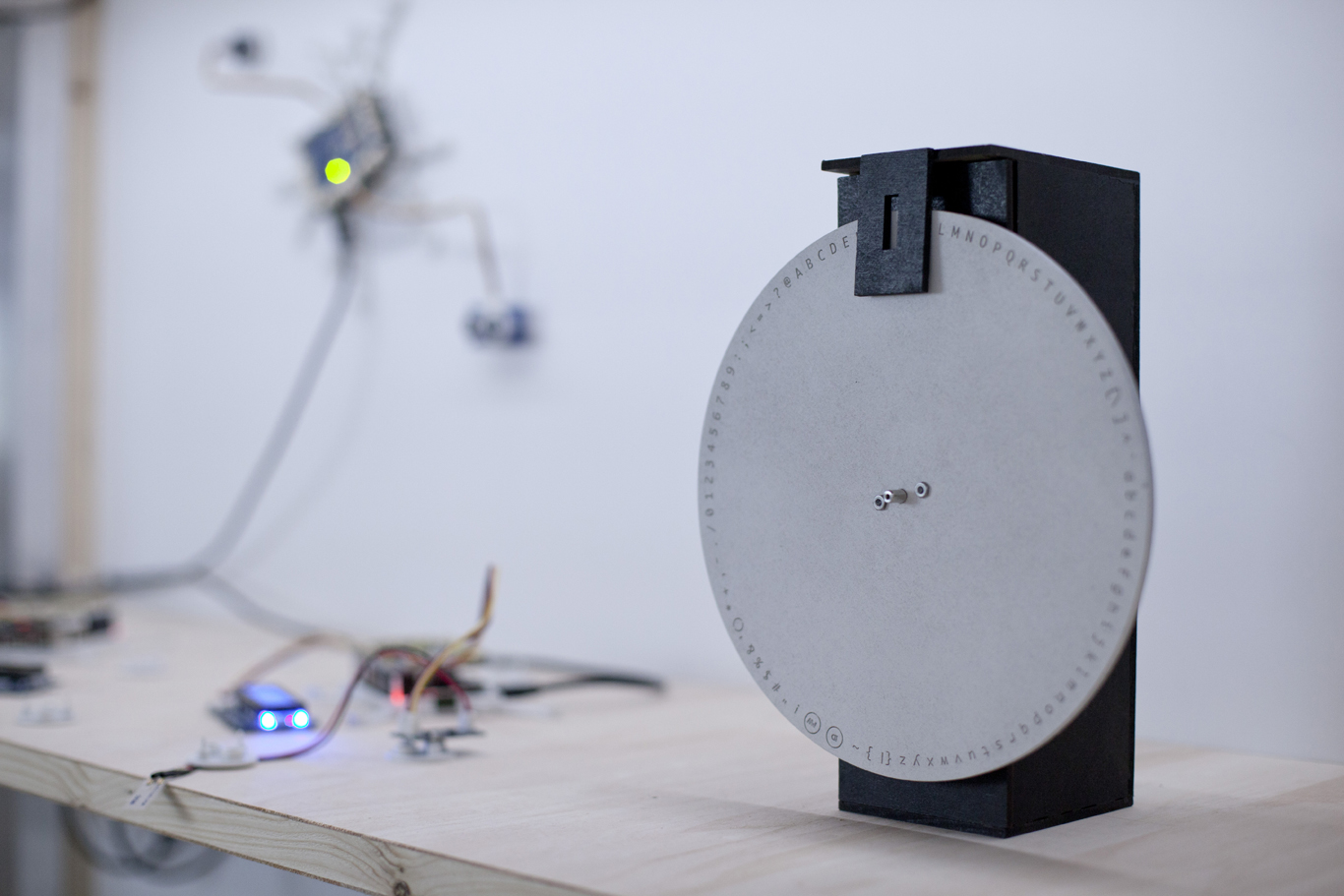

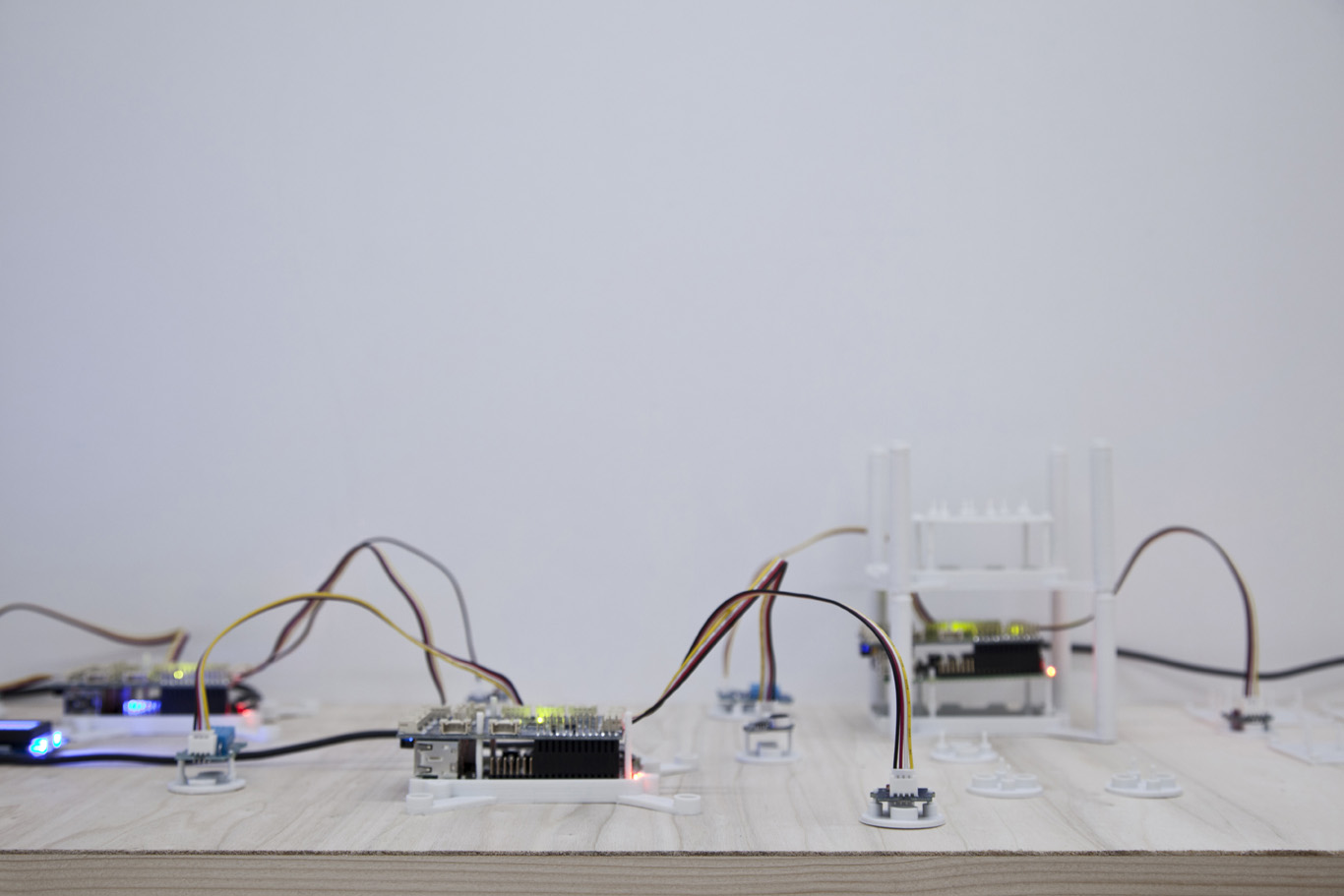

Note: last end of May was the opening of the exhibition Poetics & Politics of Data at the Haus der elektronischen Künste in Basel. This was the occasion to present the temporary results of the design research I'm leading at ECAL/University of Art & Design Lausanne, in collaboration with Nicolas Nova from HEAD - Genève, EPFL and EPFL-ECAL Lab. But for that matter, fabric | ch realized the scenography of the whole exhibition, in particular the "hidden" part hosting the presentation of the design research itself.

The whole spatial display we designed looks like some sort of "heterotopy": an archive and (computer) cabinet of curiosities within the white cube. A little bit like the "behind the scenes" of the exhibition, occupying its center, yet articulating it. It is basically made out of the modular elements that constitutes the "white cube" itself. Just that we maintained the hidden parts of these walls open and visible, widen and turn them in a pathway and an archive.

Also present in the space and scenography are different works from fabric | ch: Deterritorialized Daylight is used to drive the lighting of the inner part of the cabinet, a new work Datadroppers --an online data commune, reminiscence of the now dead Pachube-- is used to collect and re-use random data from the exhibition, several Raspberry Pis in their dedicated 3d printed casing are collecting these data (which includes, in addition to the traditional ones more surpising ones like "curiosity", "transgression", etc.) and "dropping" them on the online service. They are then searchable and be used in third parties applications.

The exhibition will still be on view until the end of August in Basel, with works by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Moniker, Aram Bartholl, Jennifer Lyn Morone, Rybn and several others.

Pictures by David Colombini and Marco Frauchiger

-

Intro text to the exhibition and credits:

Inhabiting & Interfacing the Cloud(s) is an ongoing design research about Cloud Computing. It explores the creation of counter-proposals to the current expression of this technological arrangement, particularly in its forms intended for private individuals and end users (Personal Cloud). Through its fully documented cross-disciplinary approach that connects the works of interaction designers, architects and ethnographers, this research project aims at producing alternative yet concrete models resulting from a more decentralized and citizen-oriented approach.

Halfway through the exploration process, the current status of the work is presented in the form of a (computer) cabinet (of curiosities).

http://www.iiclouds.org

Project leaders: Patrick Keller (ECAL), Nicolas Nova (HEAD)

Tutors: Christophe Guignard (ECAL), Dieter Dietz, Caroline Dionne, Manon Fantini, Thomas Favre-Bulle & Rudi Nieveen (EPFL), Nicolas Henchoz (EPFL-ECAL Lab)

Assistants: Lucien Langton (ECAL), Charles Chalas (HEAD), David Colombini

Partners: James Auger, Christian Babski, Stéphane Carion, Matthew Plummer-Fernandez

Students (ECAL): Anne-Sophie Bazard, Benjamin Botros, Caroline Buttet, Guillaume Cerdeira, Romain Cazier, Maxime Castelli, Mylène Dreyer, Bastien Girshig, Martin Hertig, Jonas Lacôte, Alexia Léchot, Nicolas Nahornyj, Pierre-Xavier Puissant

Students (HEAD): Sarah Bourquin, Hind Chamas, Marianne Czwodjdrak, Patrick Donaldson, Alexandra Gavrilova, Félicien Goguey, Eunni Sun Lee, Vanesa Lorenzo, Etienne Ndiaye, Mélissa Pisler, Camille Rattoni, Léa Thévenot, Saskia Vellas

Students (EPFL): Anne-Charlotte Astrup, Francesco Battaini, Tanguy Dyer, Delphine Passaquay

Scenography: fabric | ch

ECAL director: Alexis Georgacopoulos

HEAD – Genève director: Jean-Pierre Greff

ECAL/University of Art & Design Lausanne, HEAD – Genève, EPFL-ECAL Lab, HES-SO

|