Tuesday, October 05. 2021

Note: an interview about the implications of AI in art and the work of fabric | ch in particular, between Nathalie Bachand (writer & independant curator), Christophe Guignard and myself (both fabric | ch). The exchange happened in the context of a publication in the art magazine Espace, it was fruitful and we had the opportunity to develop on recent projects, like the "Atomized" serie of architectural works that will continue to evolve, as well as our monographic exhibition at Kunshalle Éphémère, entitled Environmental Devices (1997 - 2017).

-----

By fabric | ch

Tuesday, August 31. 2021

Note: this publication was released at the occasion of the exhibition Entangled Realities - Living with Artificial Intelligence, curated by Sabine Himmelsbach & Boris Magrini at Haus der elektronischen Künste, in Basel.

The project Atomized (curatorial) Functioning (pdf), part of the Atomized (*) Functioning serie, was presented, used and debatedi n this context.

-----

By Patrick Keller

Monday, June 21. 2021

Note: an online talk with Patrick Keller, lead archivist and curator Sang Ae Park from Nam June Paik Art Center (NJPAC) in Seoul, and Christian Babski from fabric | ch.

The topic will be related to an ongoing design research into automated curating, jointly led between NJPAC, ECAL and fabric | ch.

-----

Via Nam June Paik Art Center

How would Augmented Reality change exhibition curating and design in the future? Join our June Science Club and learn how the ECAL and Nam June Paik Art Center are collaborating to develop a novel range of museums. This talk program is hosted by Swissnex and Embassy of Switzerland in the Republic of Korea. All talks shall be in English.

---

Date

June 24, 2021. 17:00 – 18:00

Venue

Zoom

Panels

Patrick Keller (Associate Professor, ECAL / University of Art and Design Lausanne (HES-SO))

Sang Ae Park (Archivist, Nam June Paik Art Center)

Christian Babski (Co-founder fabric | ch)

---

Inquiry

library@njpartcenter.kr

Friday, October 20. 2017

Note: More than a year ago, I posted about this move by Alphabet-Google toward becoming city designers... I tried to point out the problems related to a company which business is to collect data becoming the main investor in public space and common goods (the city is still part of the commons, isn't it?) But of course, this is, again, about big business ("to make the world a better place" ... indeed) and slick ideas.

But it is highly problematic that a company start investing in public space "for free". We all know what this mean now, don't we? It is not needed and not desired.

So where are the "starchitects" now? What do they say? Not much... Where are all the "regular" architects as well? Almost invisible, tricked in the wrong stakes, with -- I'm sorry...-- very few of them being only able to identify the problem.

This is not about building a great building for a big brand or taking a conceptual position, not even about "die Gestalt" anymore. It is about everyday life for 66% of Earth population by 2050 (UN study). It is, in this precise case, about information technologies and mainly information stategies and businesses that materialize into structures of life.

Shouldn't this be a major concern?

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

By Jamie Condliffe

fabric | rblg legend: this hand drawn image contains all the marketing clichés (green, blue, clean air, bikes, local market, public transportation, autonomous car in a happy village atmosphere... Can't be further from what it will be).

An 800-acre strip of Toronto's waterfront may show us how cities of the future could be built. Alphabet’s urban innovation team, Sidewalk Labs, has announced a plan to inject urban design and new technologies into the city's quayside to boost "sustainability, affordability, mobility, and economic opportunity."

Huh?

Picture streets filled with robo-taxis, autonomous trash collection, modular buildings, and clean power generation. The only snag may be the humans: as we’ve said in the past, people can do dumb things with smart cities. Perhaps Toronto will be different.

Monday, April 10. 2017

Note: this "car action" by James Bridle was largely reposted recently. Here comes an additionnal one...

Yet, in the context of this blog, it interests us because it underlines the possibilities of physical (or analog) hacks linked to digital devices that can see, touch, listen or produce sound, etc.

And they are several existing examples of "physical bugs" that come to mind: "Echo" recently tried to order cookies after listening and misunderstanding a american TV ad (it wasn't on Fox news though). A 3d print could be reproduced by listening and duplicating the sound of its printer, and we can now think about self-driving cars that could be tricked as well, mainly by twisting the elements upon which they base their understanding of the environment.

Interesting error potential...

Via Archinect

-----

By Julia Ingalls

James Bridle entraps a self-driving car in a "magic" salt circle. Image: Still from Vimeo, "Autonomous Trap 001."

As if the challenges of politics, engineering, and weather weren't enough, now self-driving cars face another obstacle: purposeful visual sabotage, in the form of specially painted traffic lines that entice the car in before trapping it in an endless loop. As profiled in Vice, the artist behind "Autonomous Trip 001," James Bridle, is demonstrating an unforeseen hazard of automation: those forces which, for whatever reason, want to mess it all up. Which raises the question: how does one effectively design for an impish sense of humor, or a deadly series of misleading markings?

Tuesday, July 05. 2016

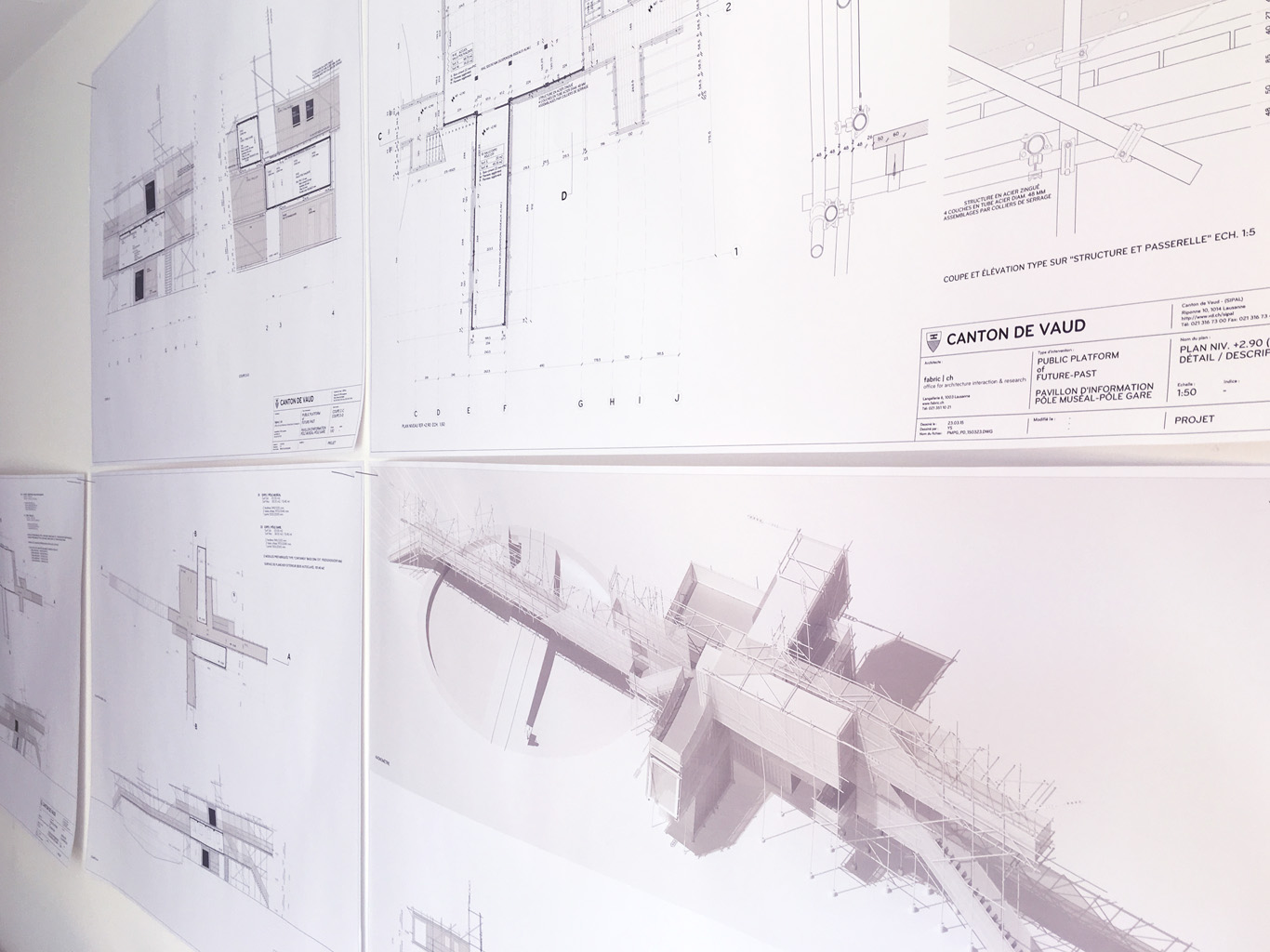

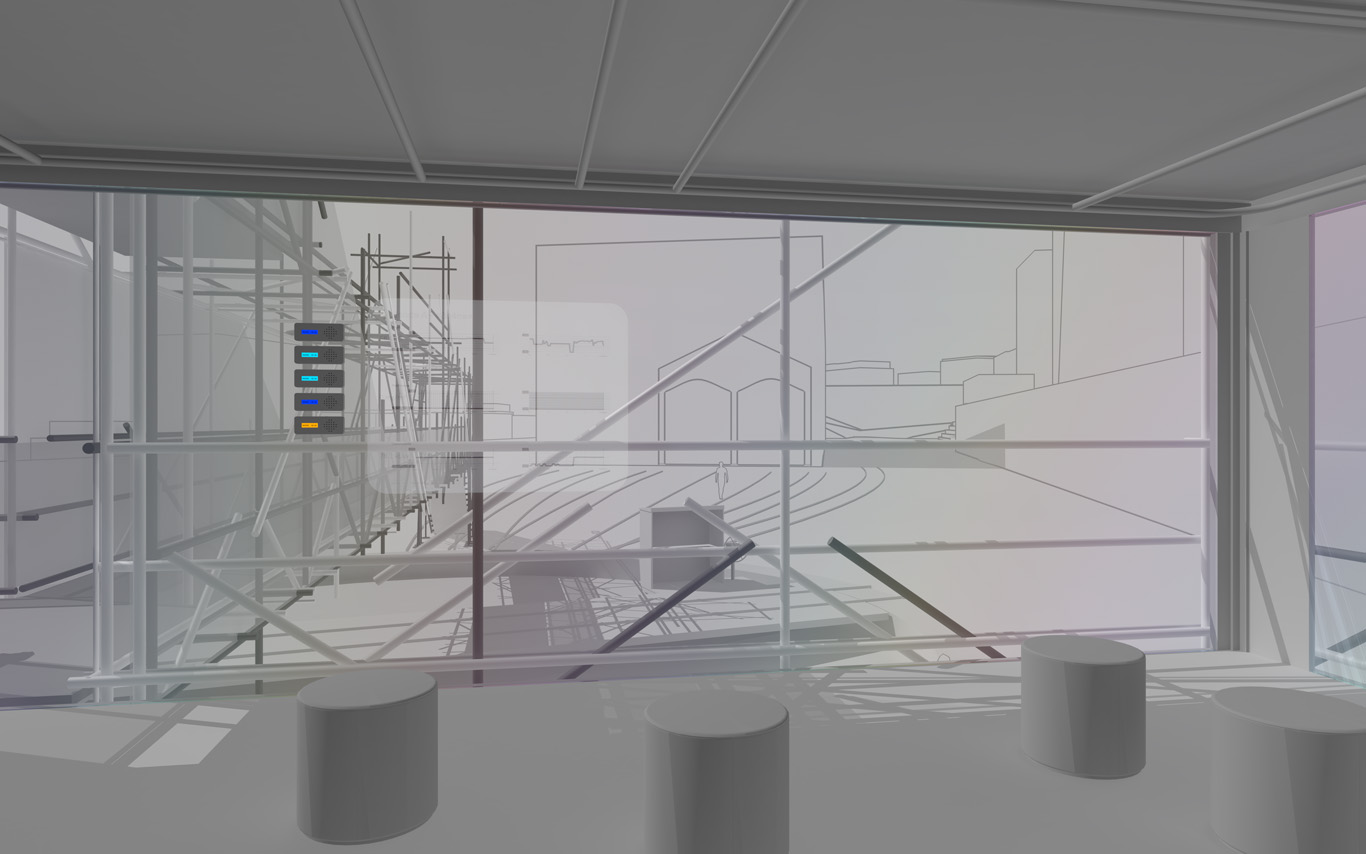

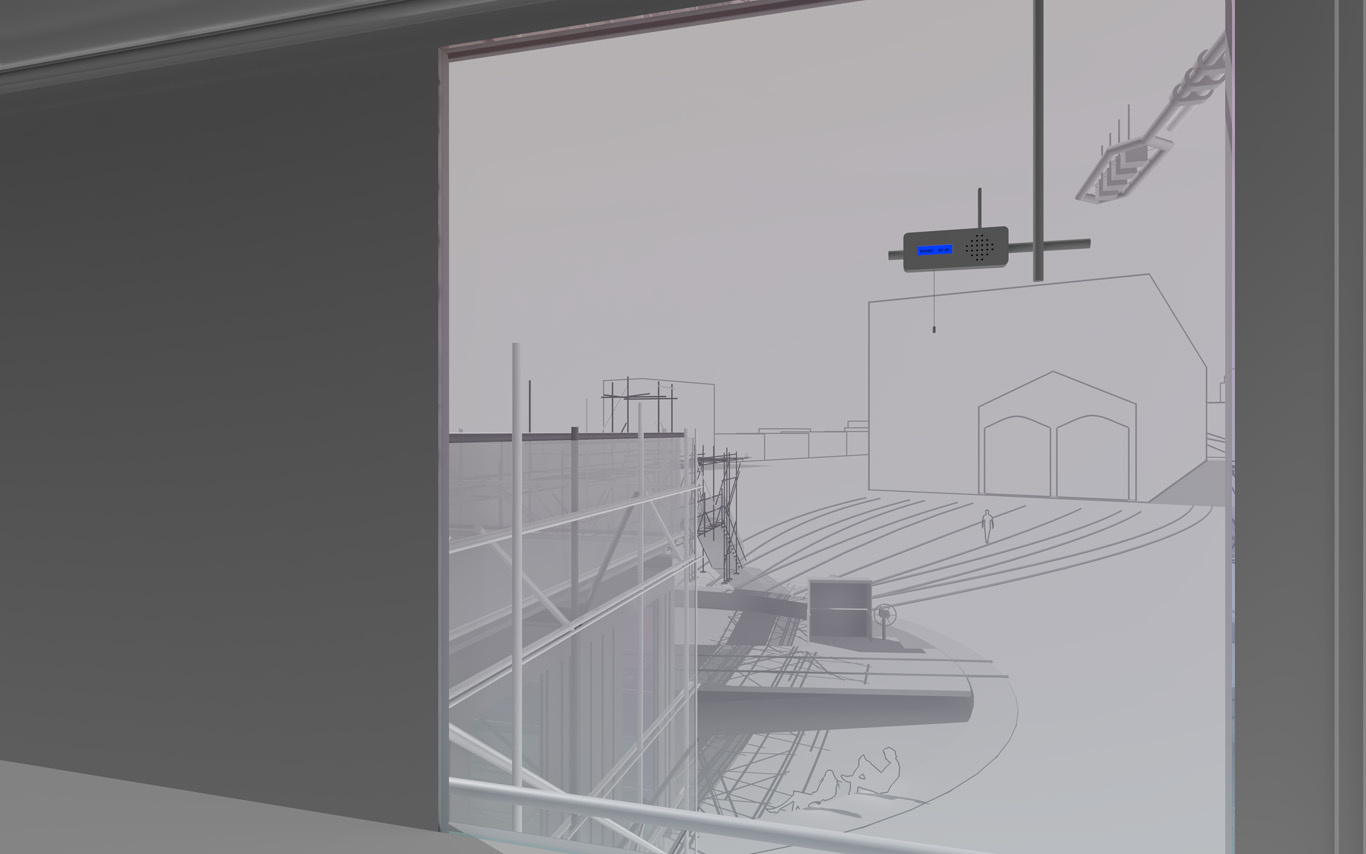

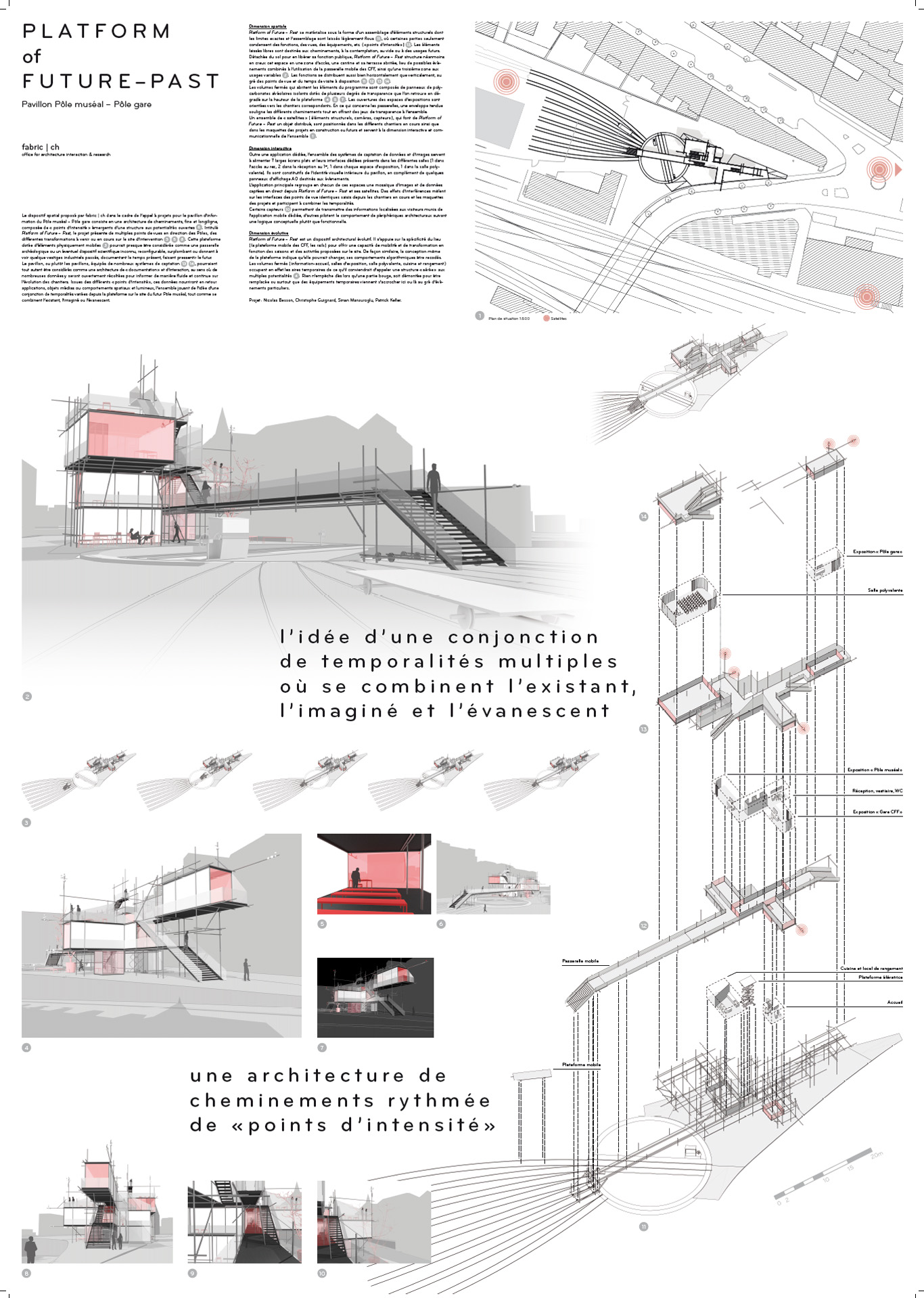

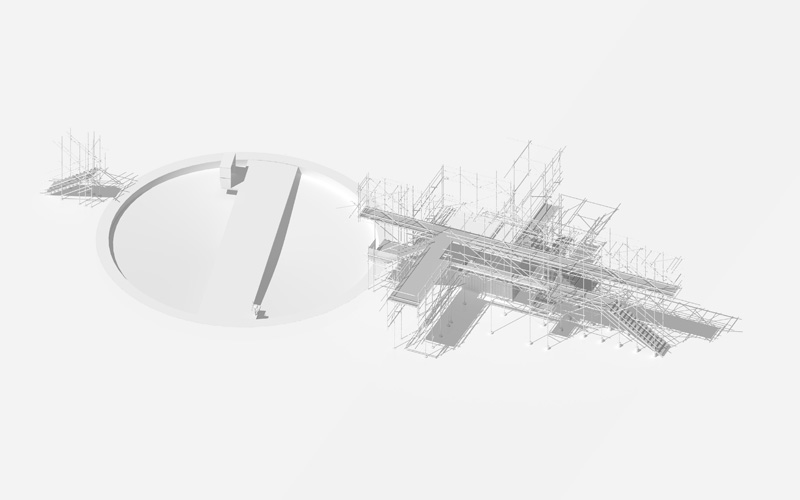

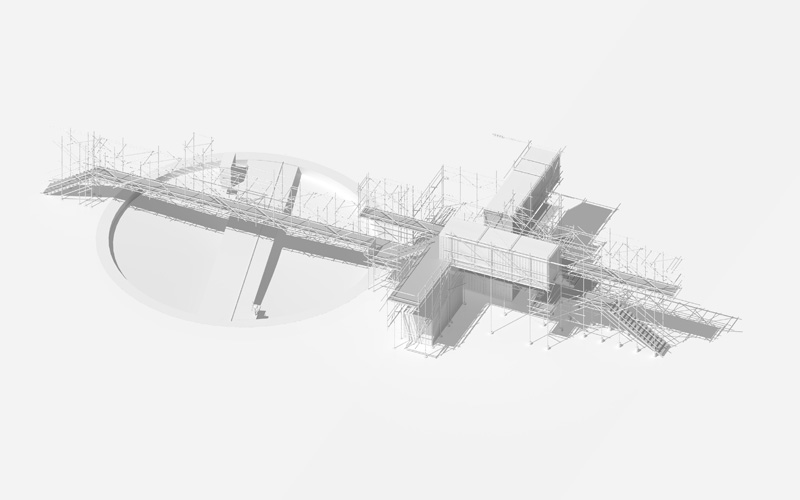

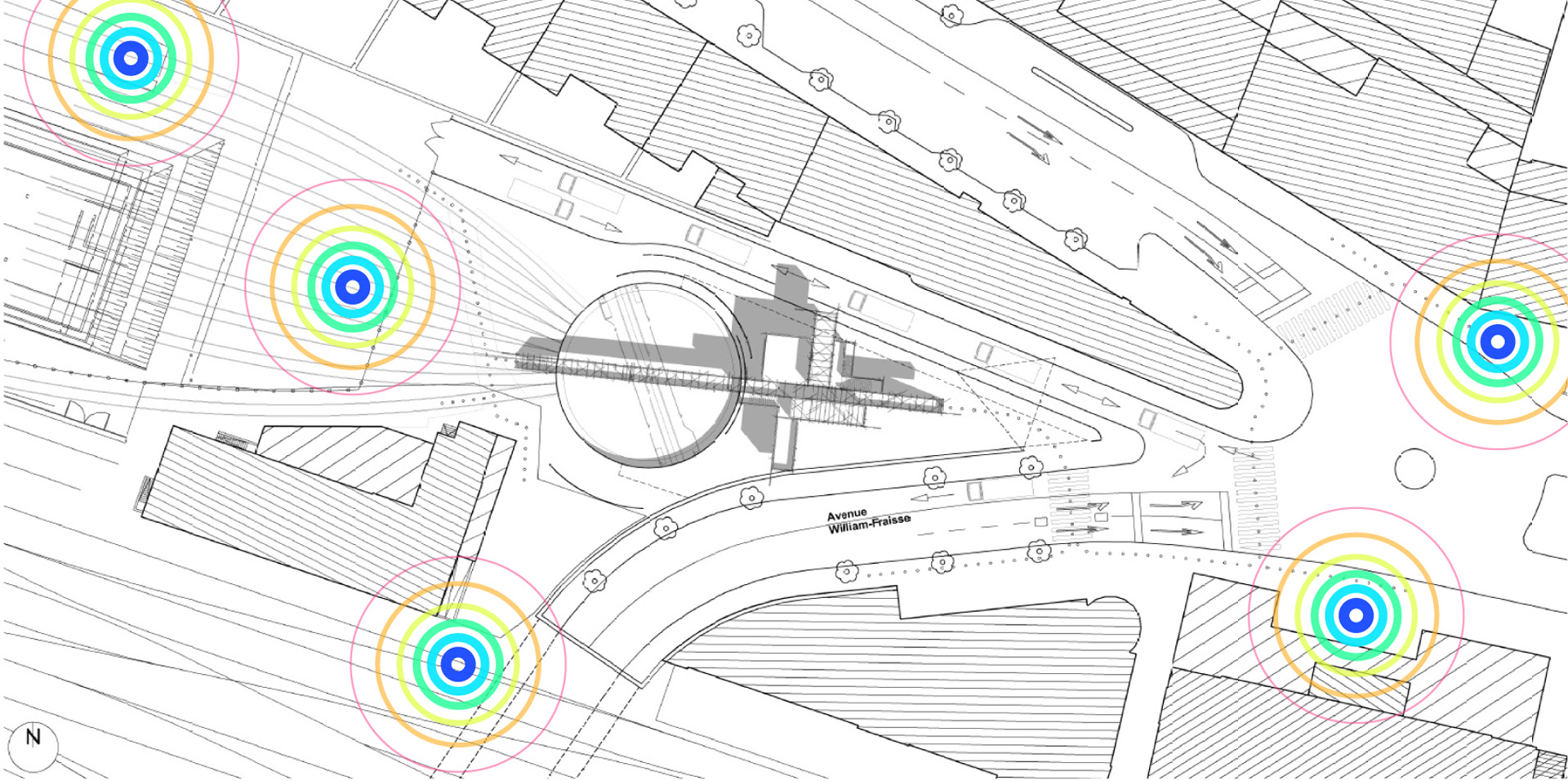

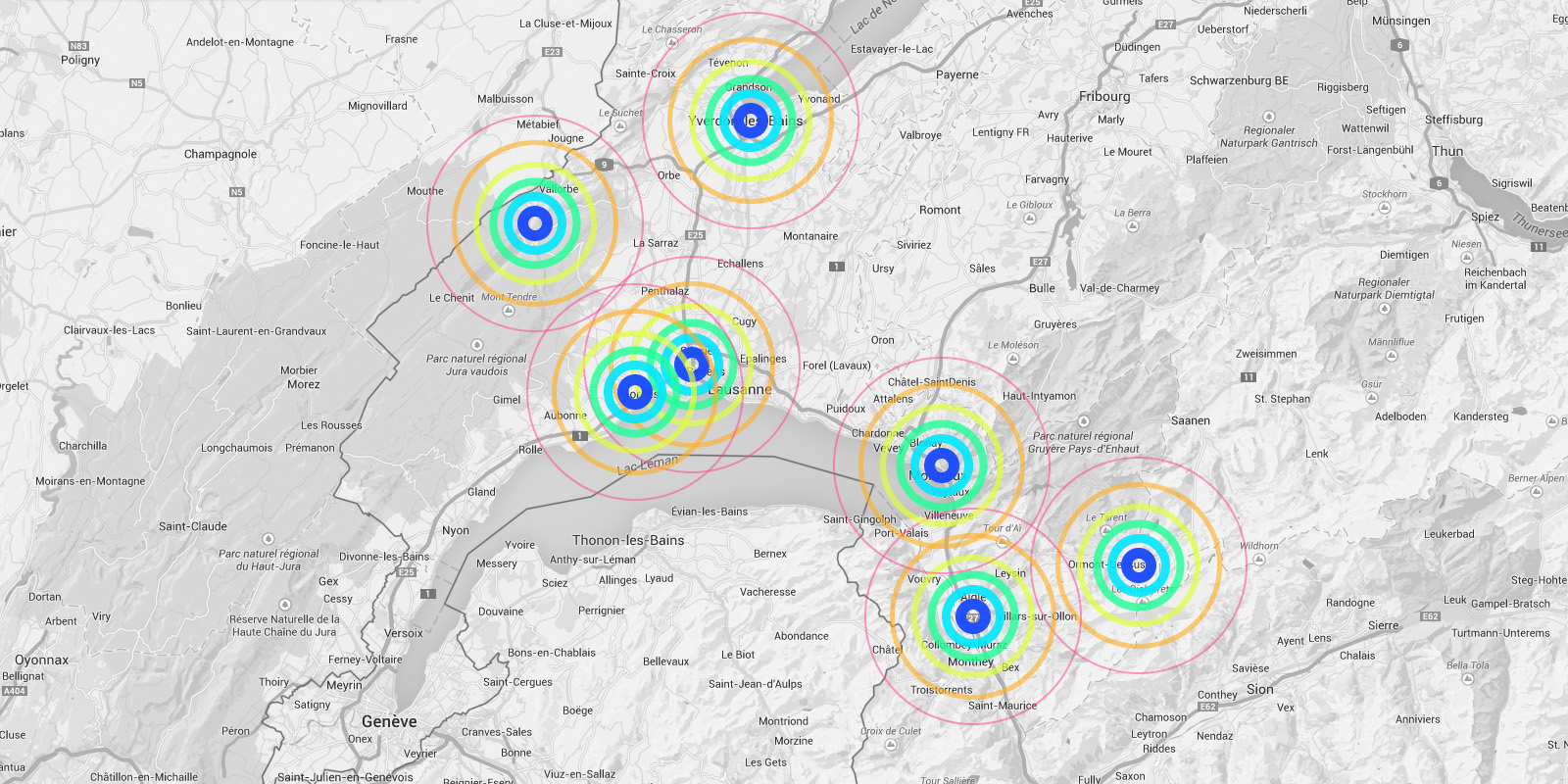

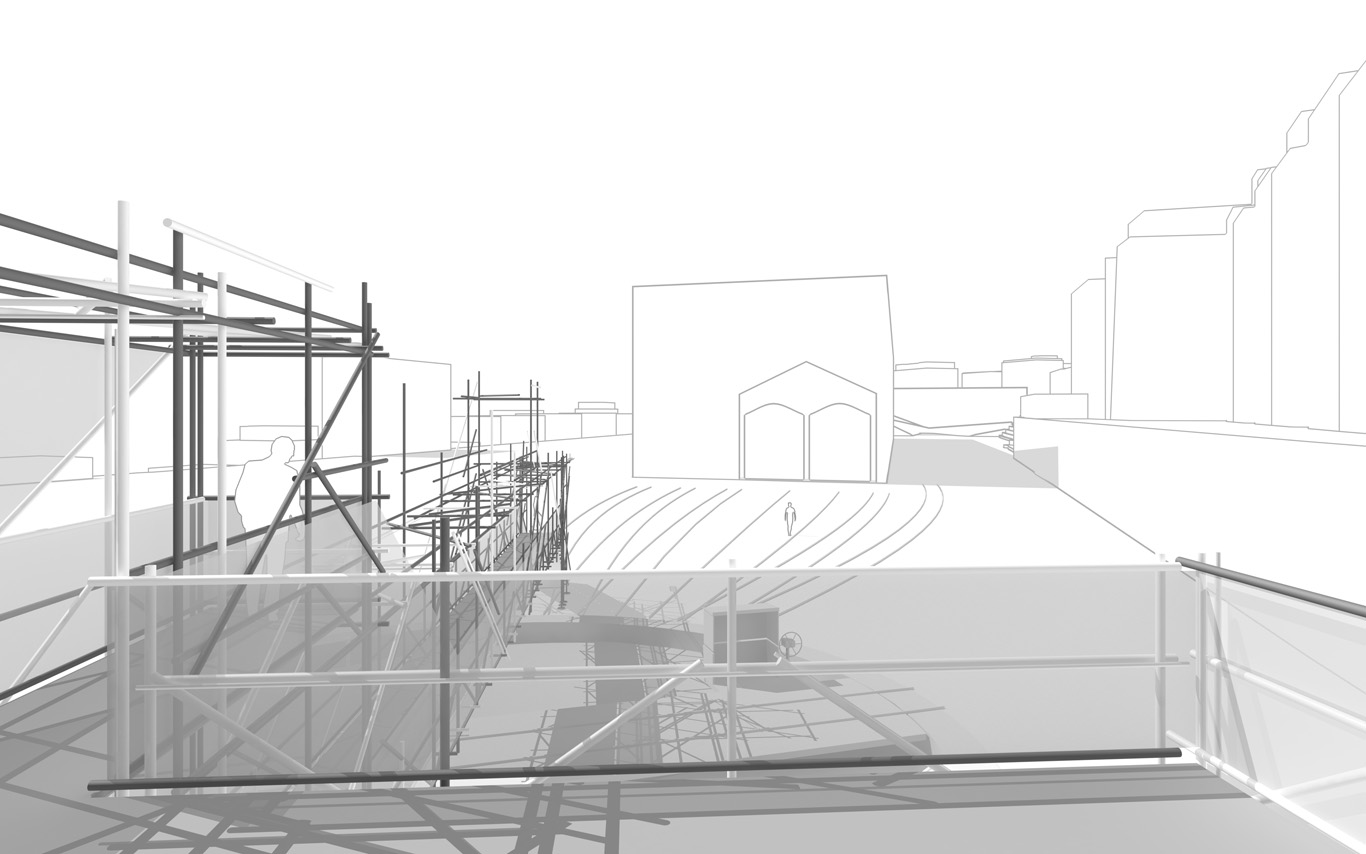

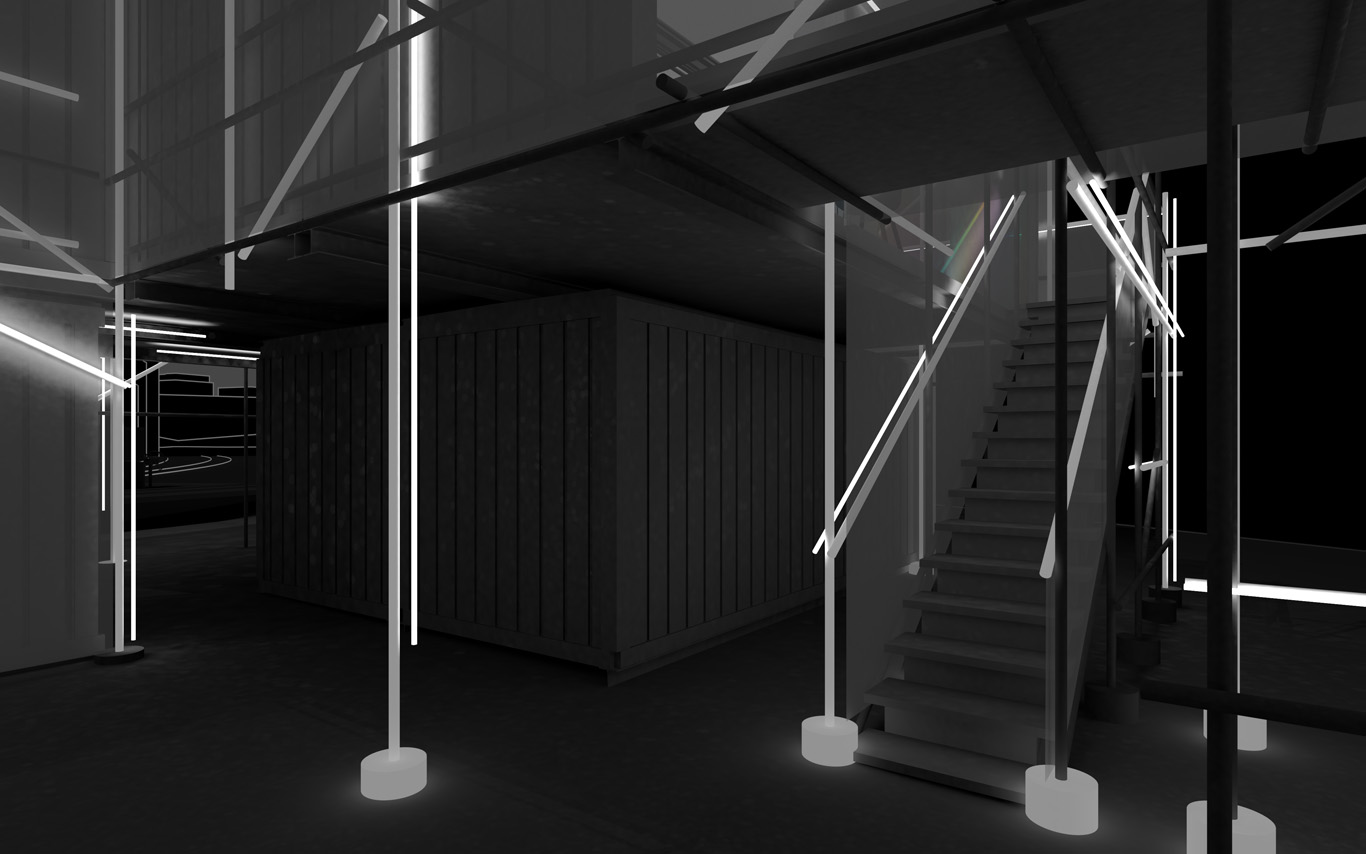

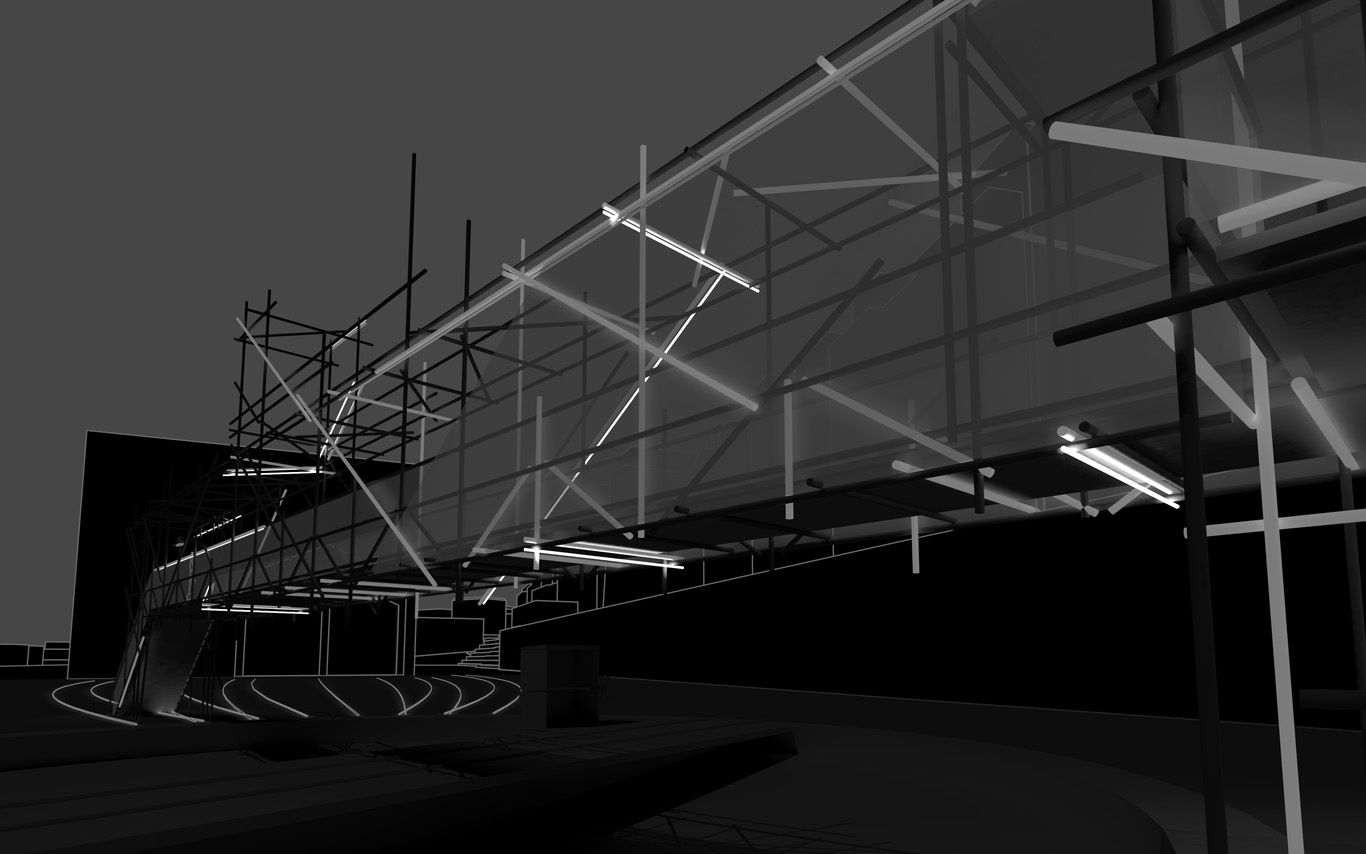

Note: in the continuity of my previous post/documentation concerning the project Platform of Future-Past (fabric | ch's recent winning competition proposal), I publish additional images (several) and explanations about the second phase of the Platform project, for which we were mandated by Canton de Vaud (SiPAL).

The first part of this article gives complementary explanations about the project, but I also take the opportunity to post related works and researches we've done in parallel about particular implications of the platform proposal. This will hopefully bring a neater understanding to the way we try to combine experimentations-exhibitions, the creation of "tools" and the design of larger proposals in our open and process of work.

Notably, these related works concerned the approach to data, the breaking of the environment into computable elements and the inevitable questions raised by their uses as part of a public architecture project.

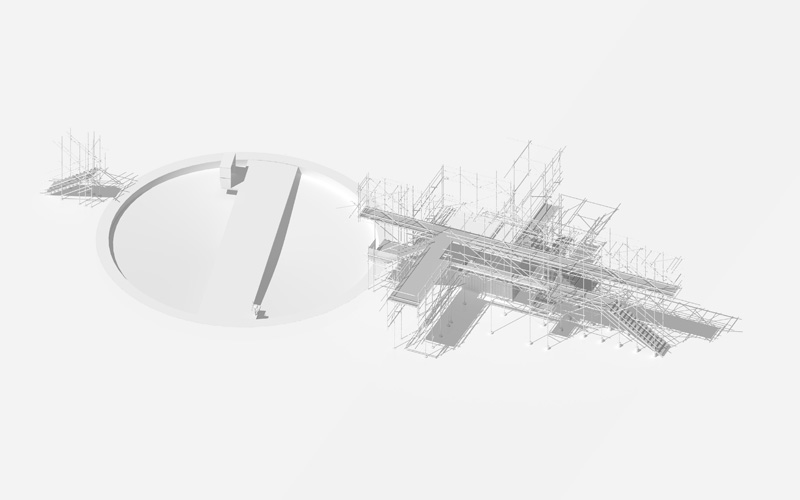

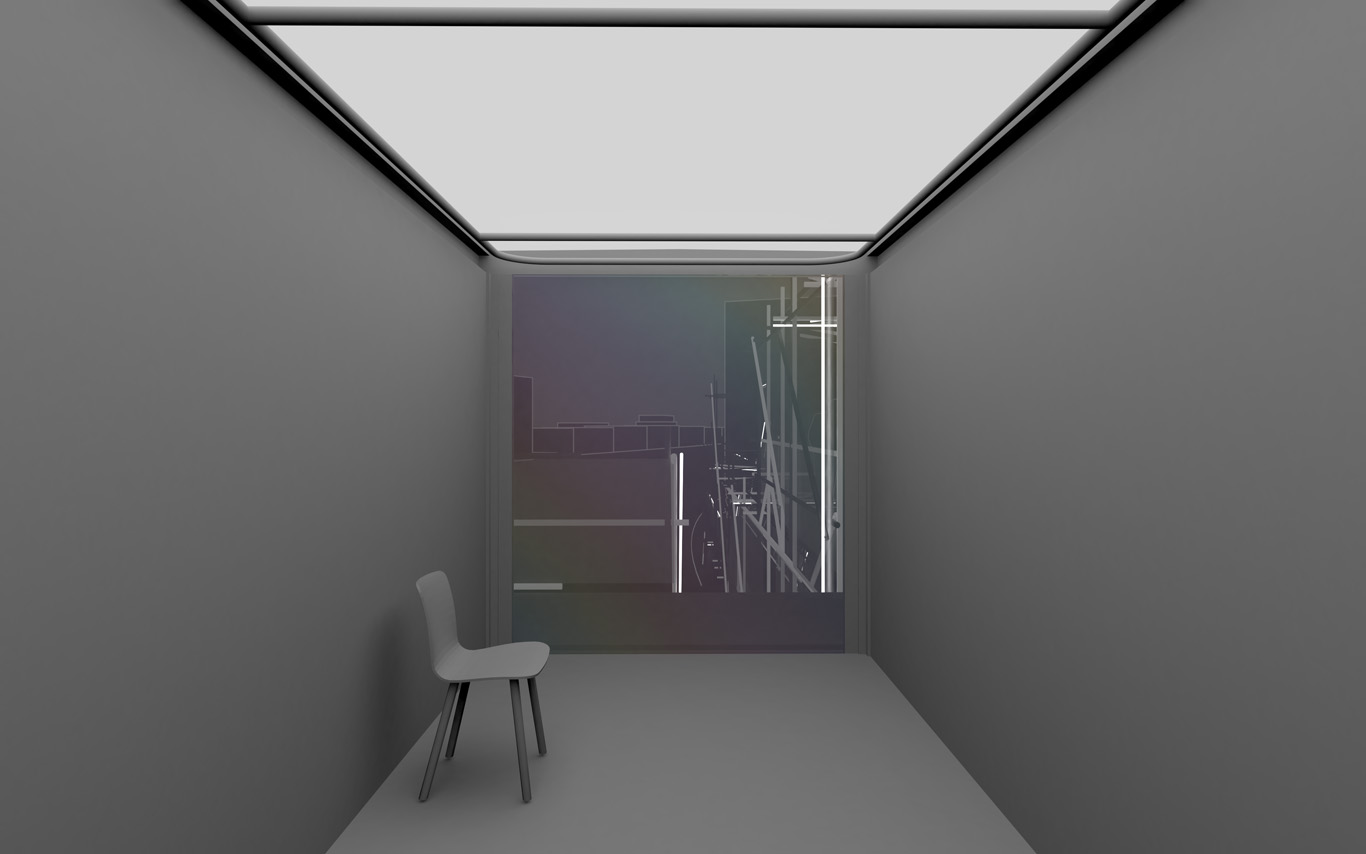

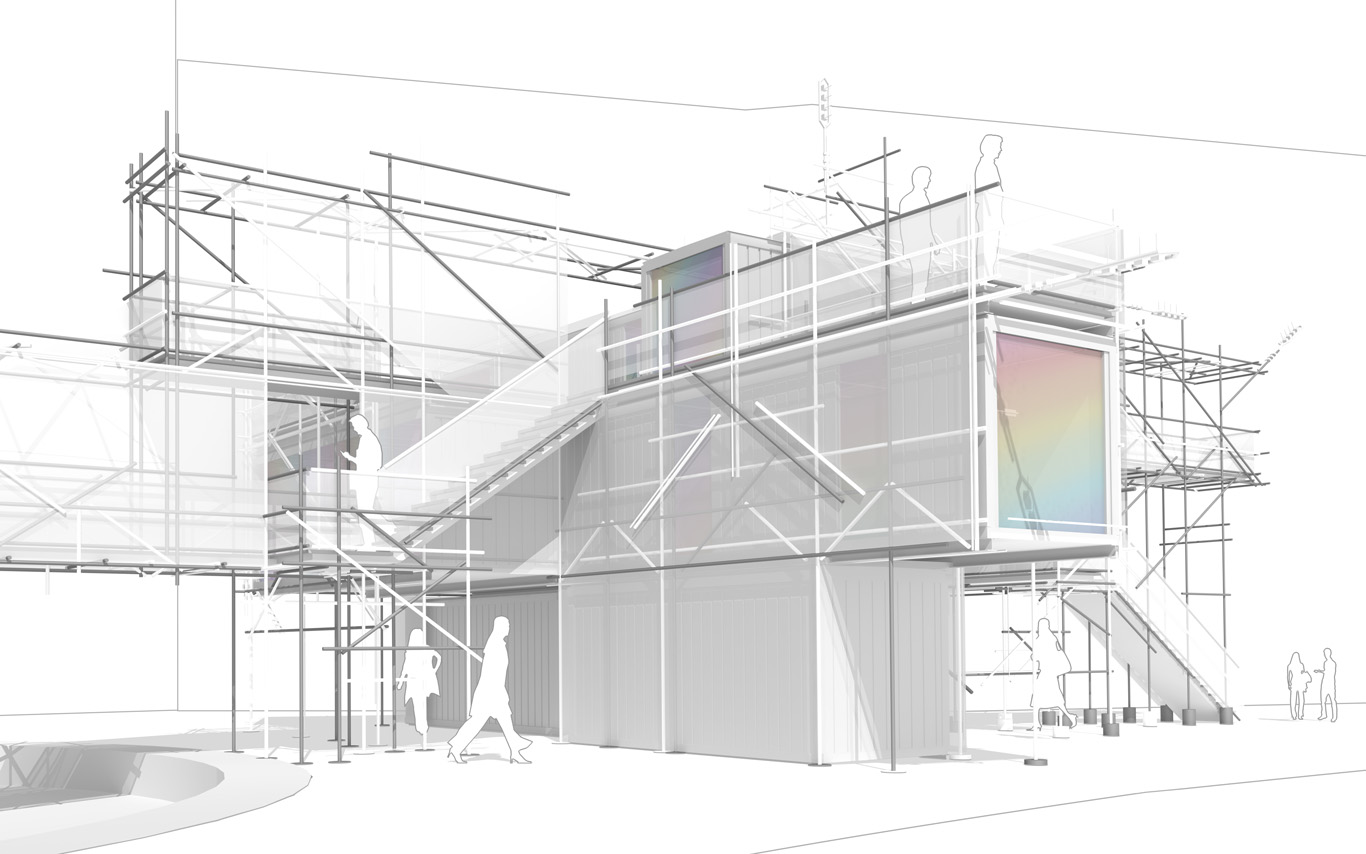

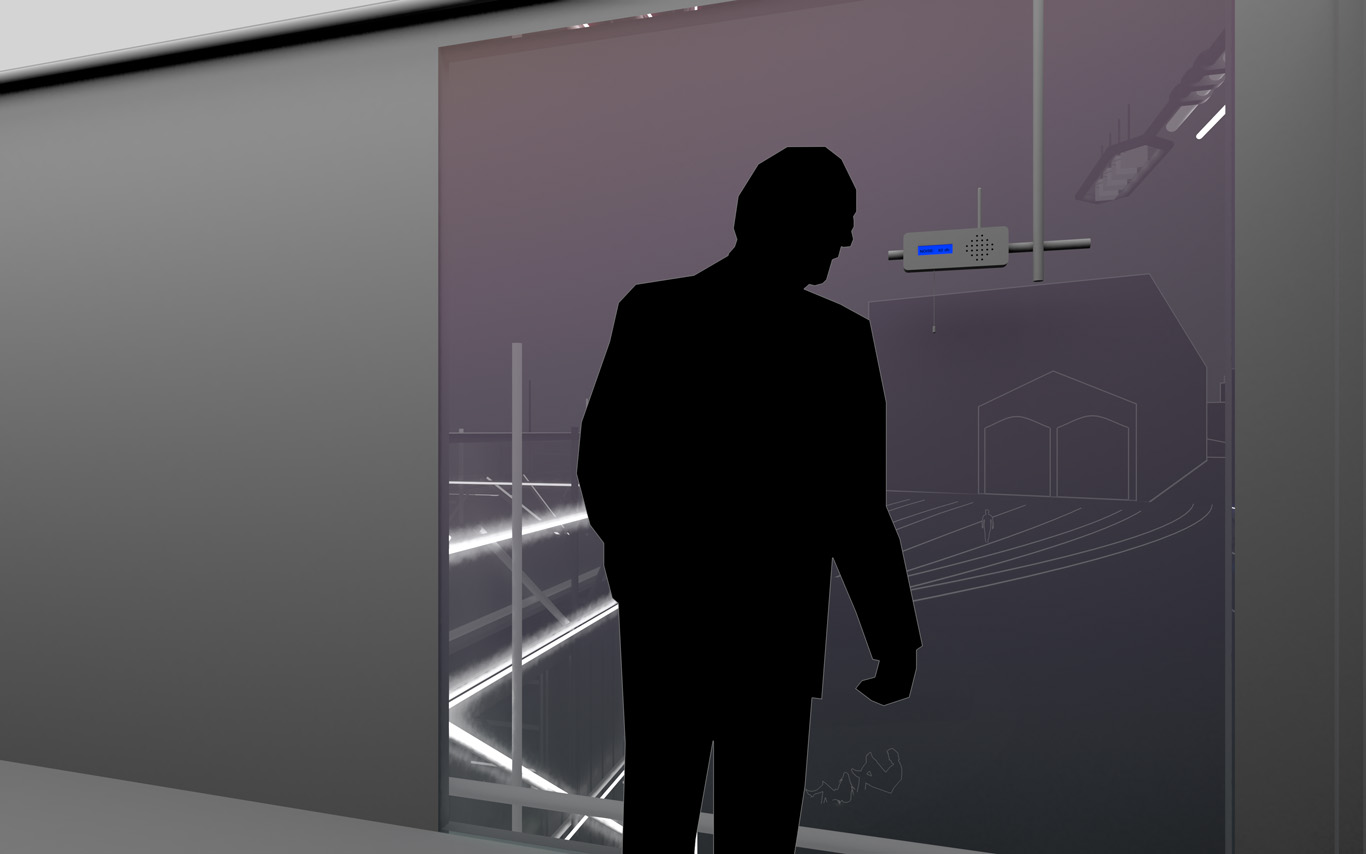

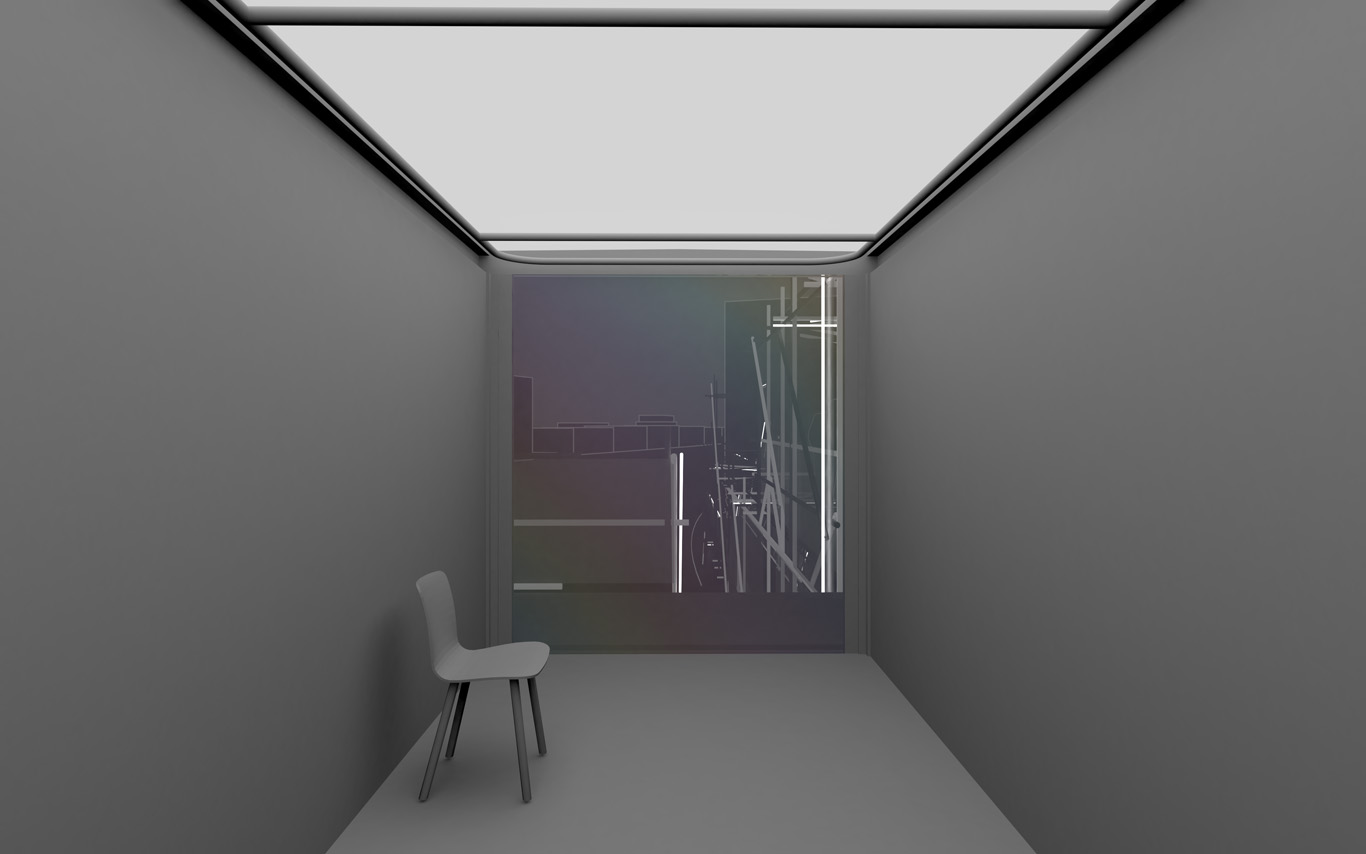

The information pavilion was potentially a slow, analog and digital "shape/experience shifter", as it was planned to be built in several succeeding steps over the years and possibly "reconfigure" to sense and look at its transforming surroundings.

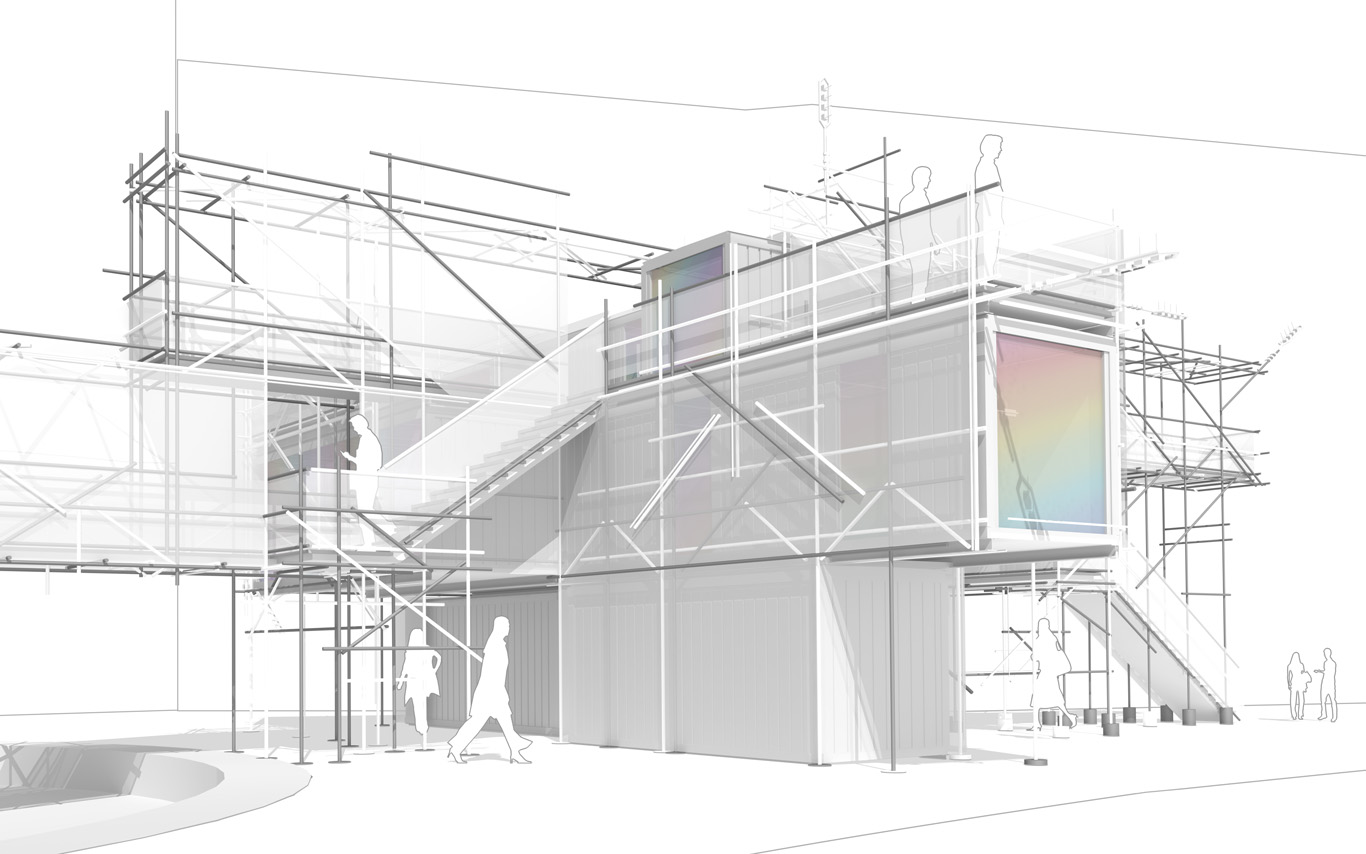

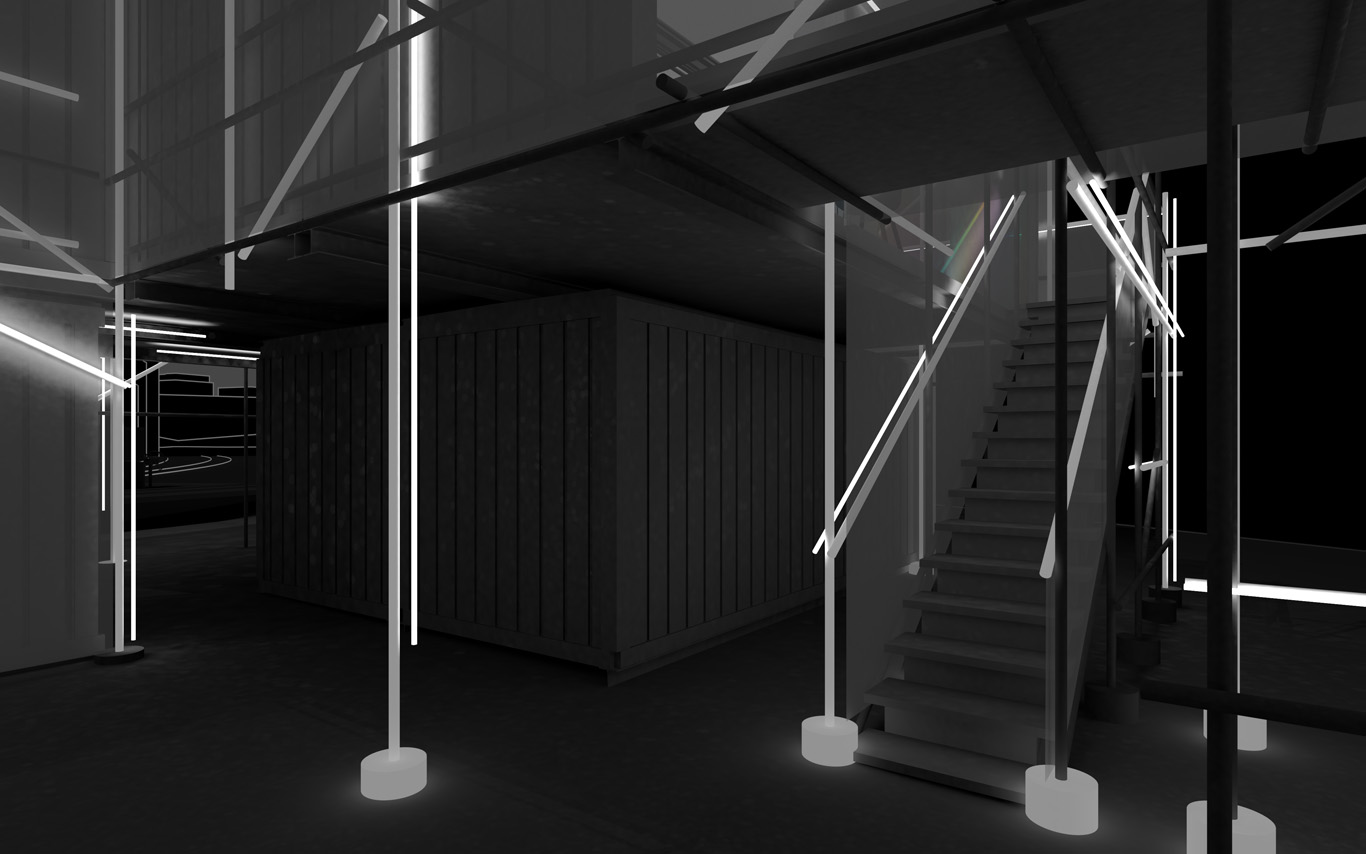

The pavilion conserved therefore an unfinished flavour as part of its DNA, inspired by these old kind of meshed constructions (bamboo scaffoldings), almost sketched. This principle of construction was used to help "shift" if/when necessary.

In a general sense, the pavilion answered the conventional public program of an observation deck about a construction site. It also served the purpose of documenting the ongoing building process that often comes along. By doing so, we turned the "monitoring dimension" (production of data) of such a program into a base element of our proposal. That's where a former experimental installation helped us: Heterochrony.

As it can be noticed, the word "Public" was added to the title of the project between the two phases, to become Public Platform of Future-Past (PPoFP) ... which we believe was important to add. This because it was envisioned that the PPoFP would monitor and use environmental data concerning the direct surroundings of the information pavilion (but NO DATA about uses/users). Data that we stated in this case Public, while the treatment of the monitored data would also become part of the project, "architectural" (more below about it).

For these monitored data to stay public, so as for the space of the pavilion itself that would be part of the public domain and physically extends it, we had to ensure that these data wouldn't be used by a third party private service. We were in need to keep an eye on the algorithms that would treat the spatial data. Or best, write them according to our design goals (more about it below).

That's were architecture meets code and data (again) obviously...

By fabric | ch

-----

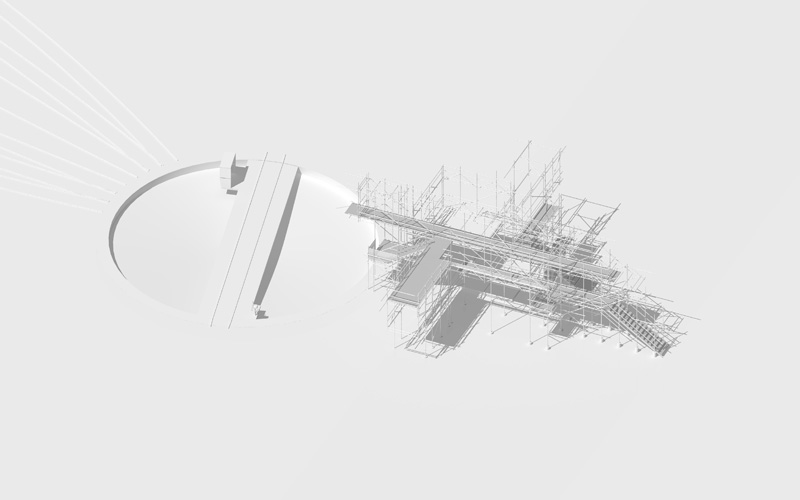

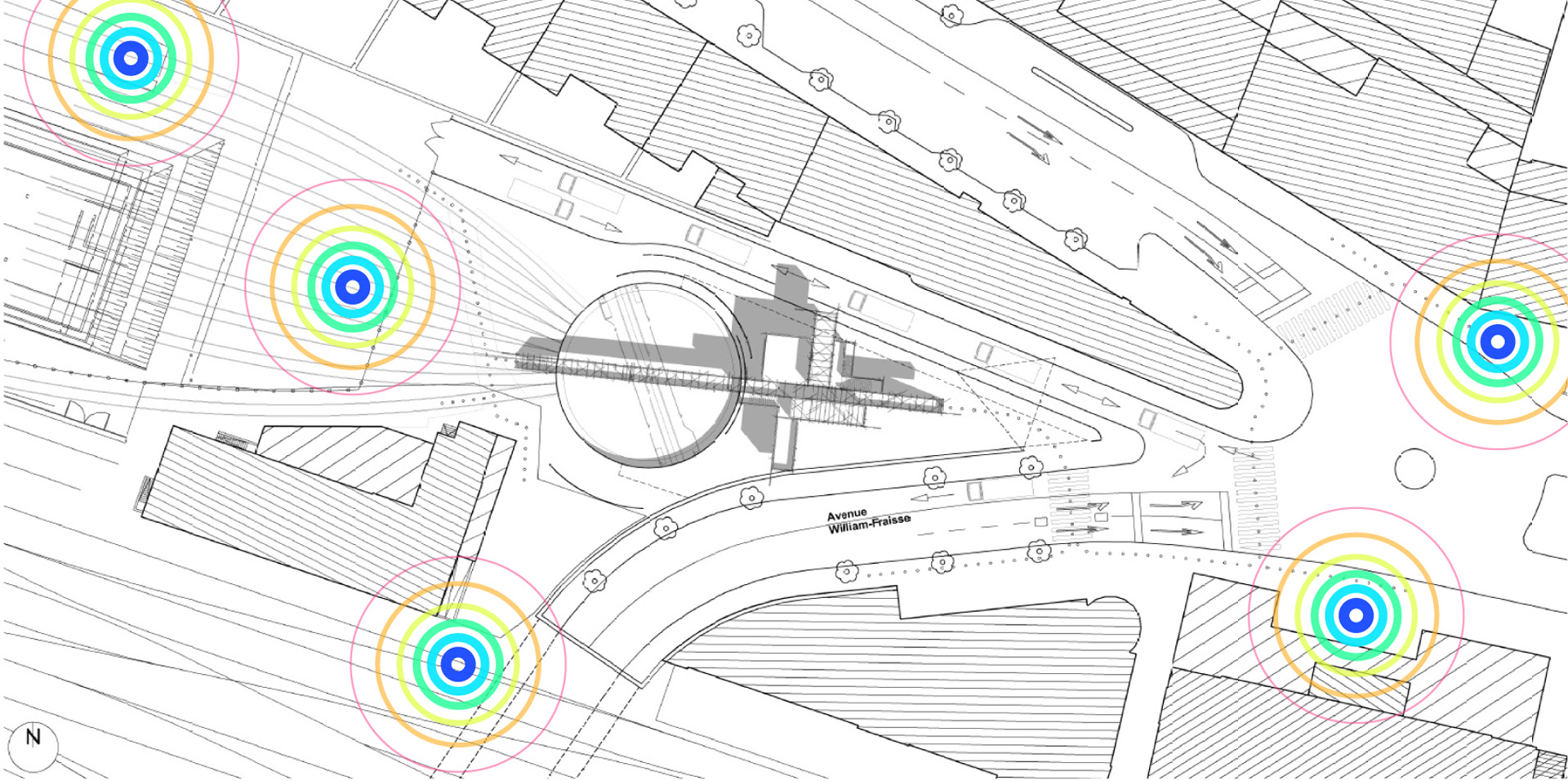

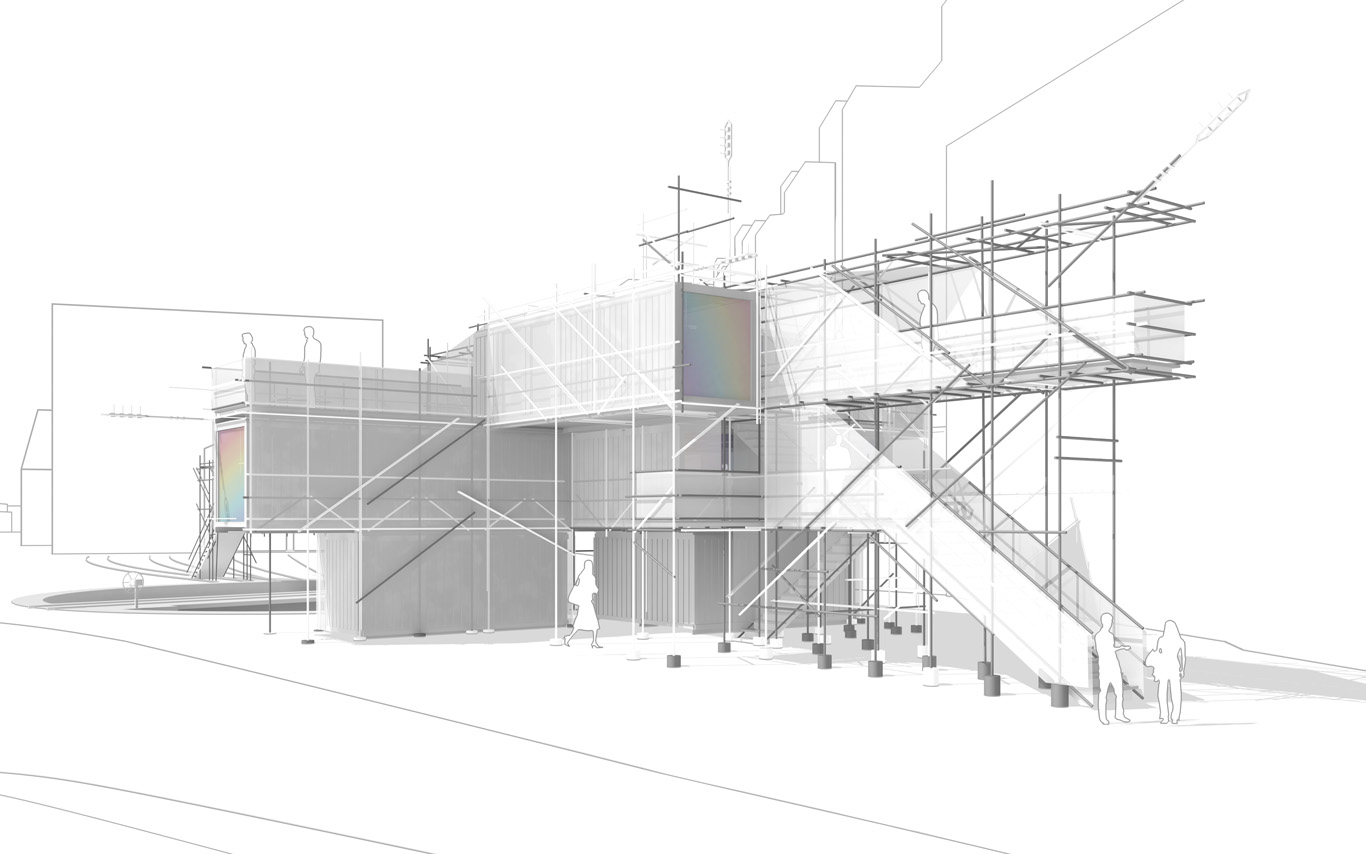

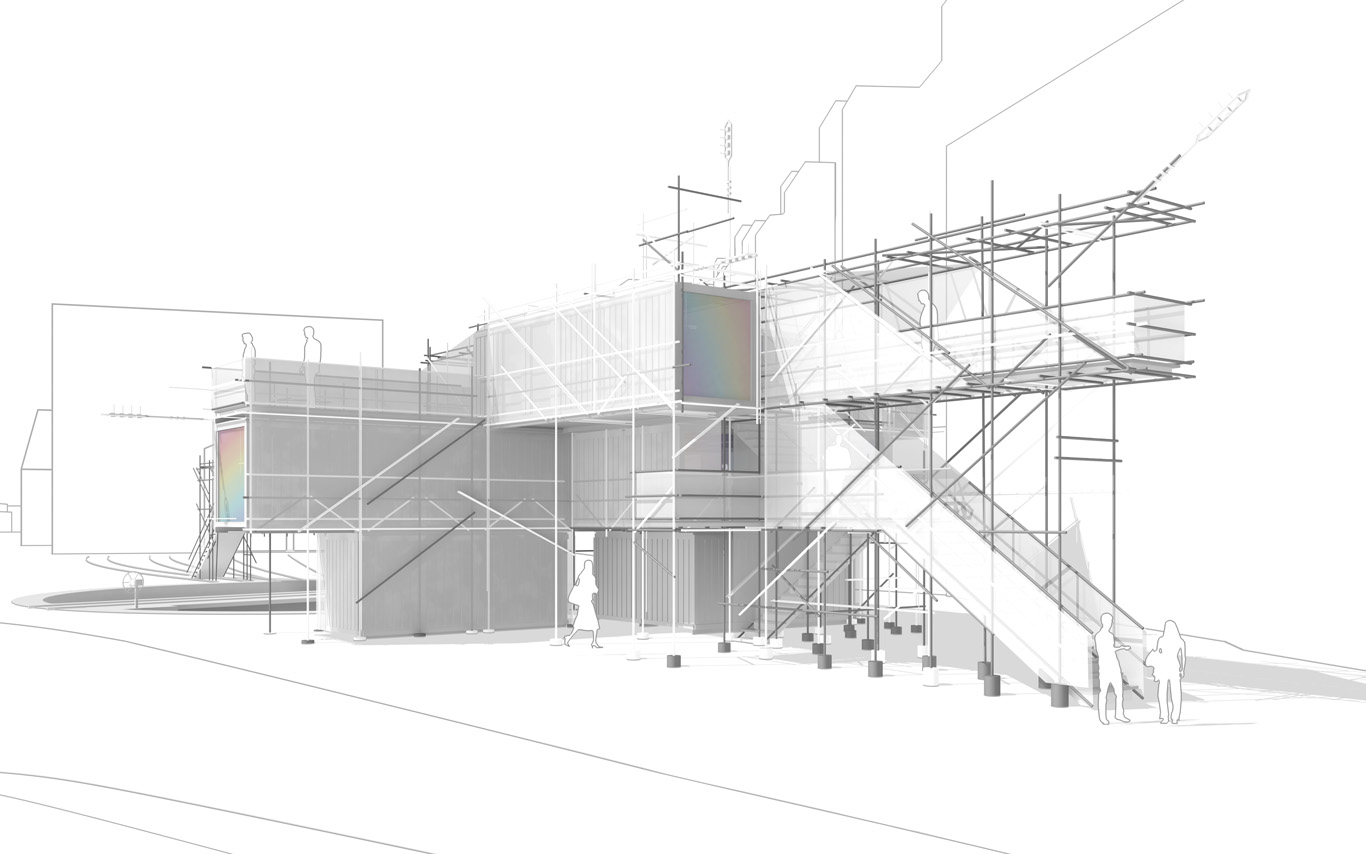

The Public Platform of Future-Past is a structure (an information and sightseeing pavilion), a Platform that overlooks an existing Public site while basically taking it as it is, in a similar way to an archeological platform over an excavation site.

The asphalt ground floor remains virtually untouched, with traces of former uses kept as they are, some quite old (a train platform linked to an early XXth century locomotives hall), some less (painted parking spaces). The surrounding environment will move and change consideralby over the years while new constructions will go on. The pavilion will monitor and document these changes. Therefore the last part of its name: "Future-Past".

By nonetheless touching the site in a few points, the pavilion slightly reorganizes the area and triggers spaces for a small new outdoor cafe and a bikes parking area. This enhanced ground floor program can work by itself, seperated from the upper floors.

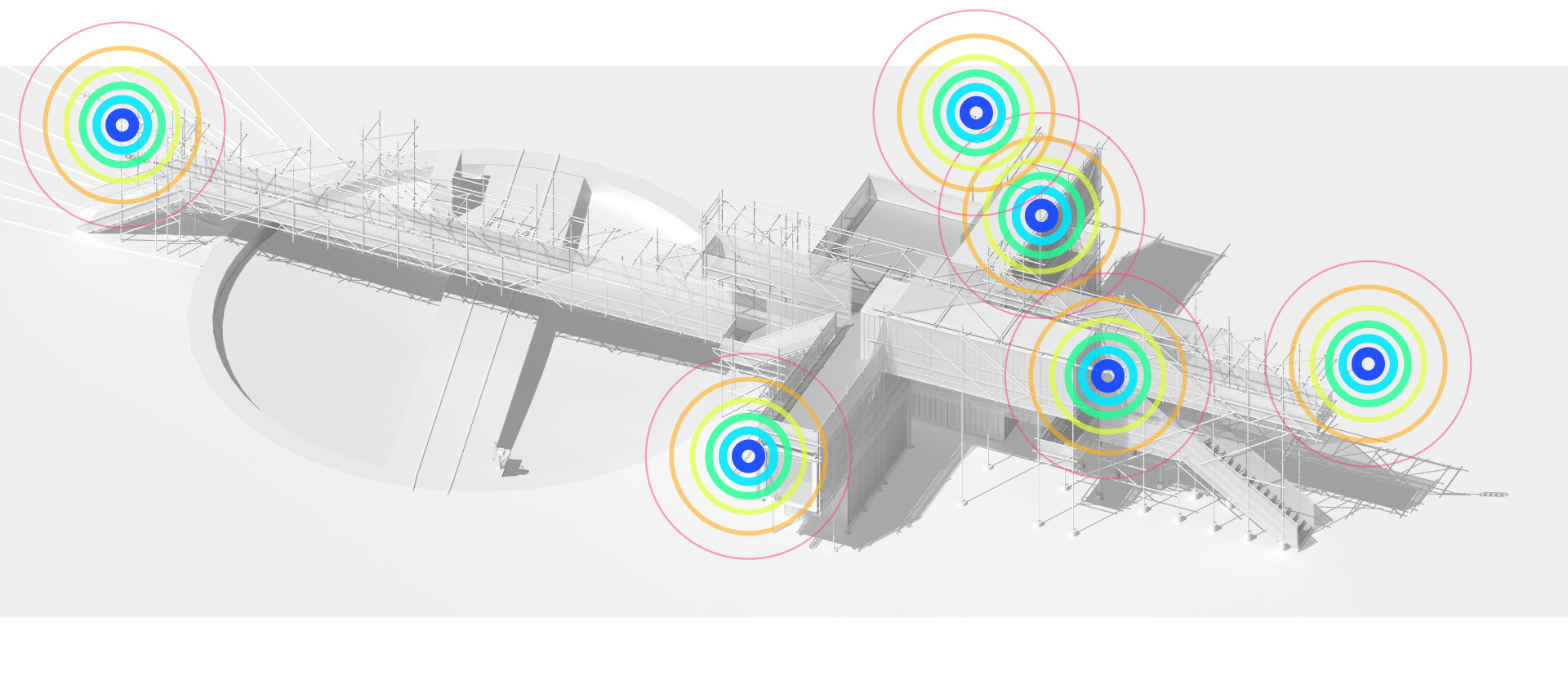

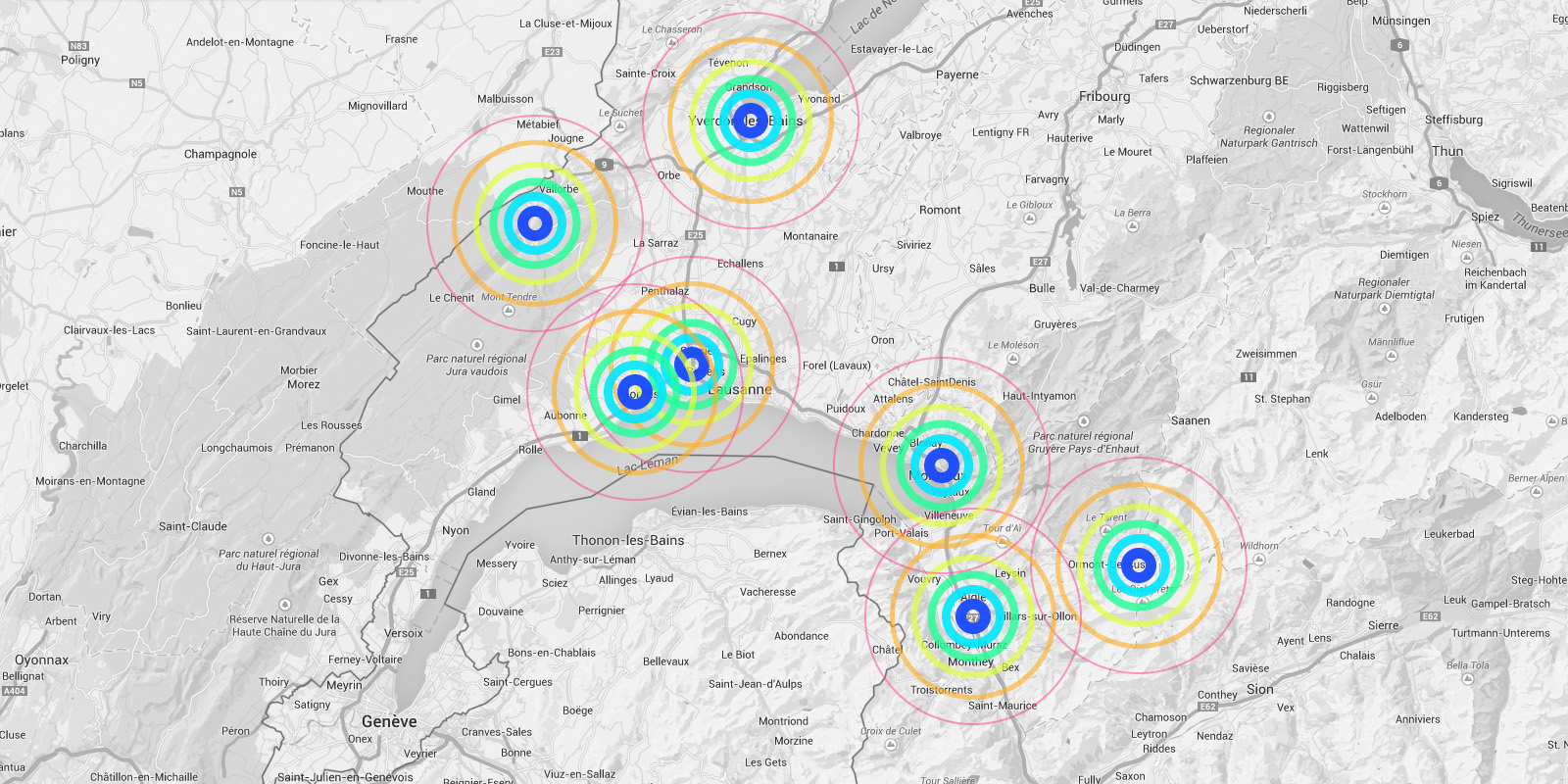

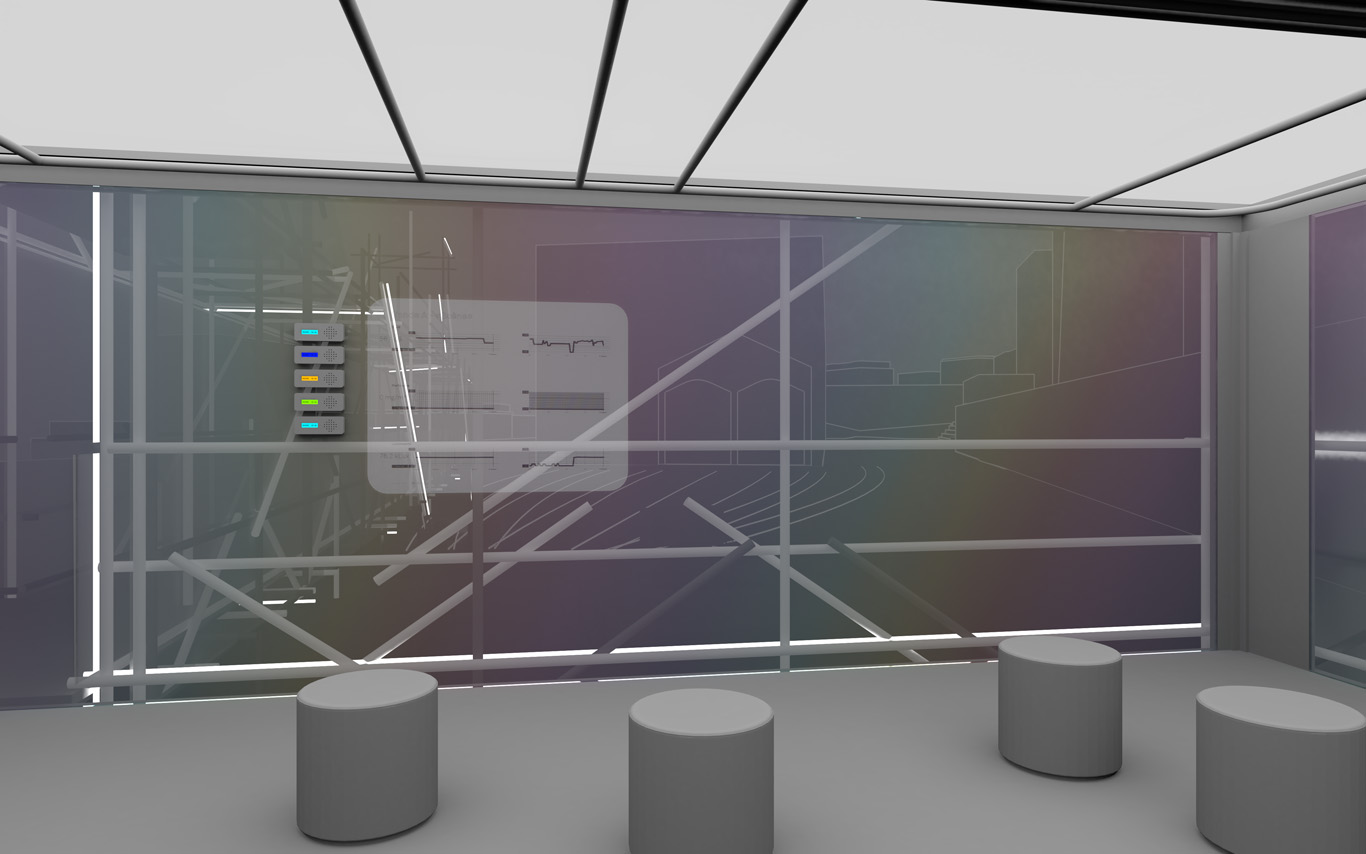

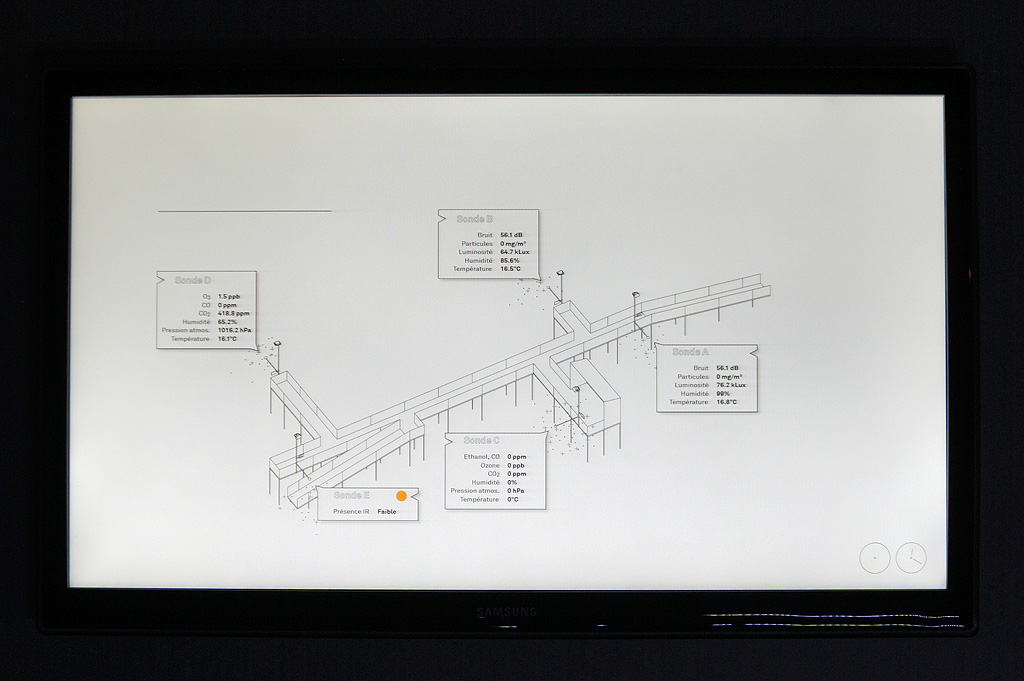

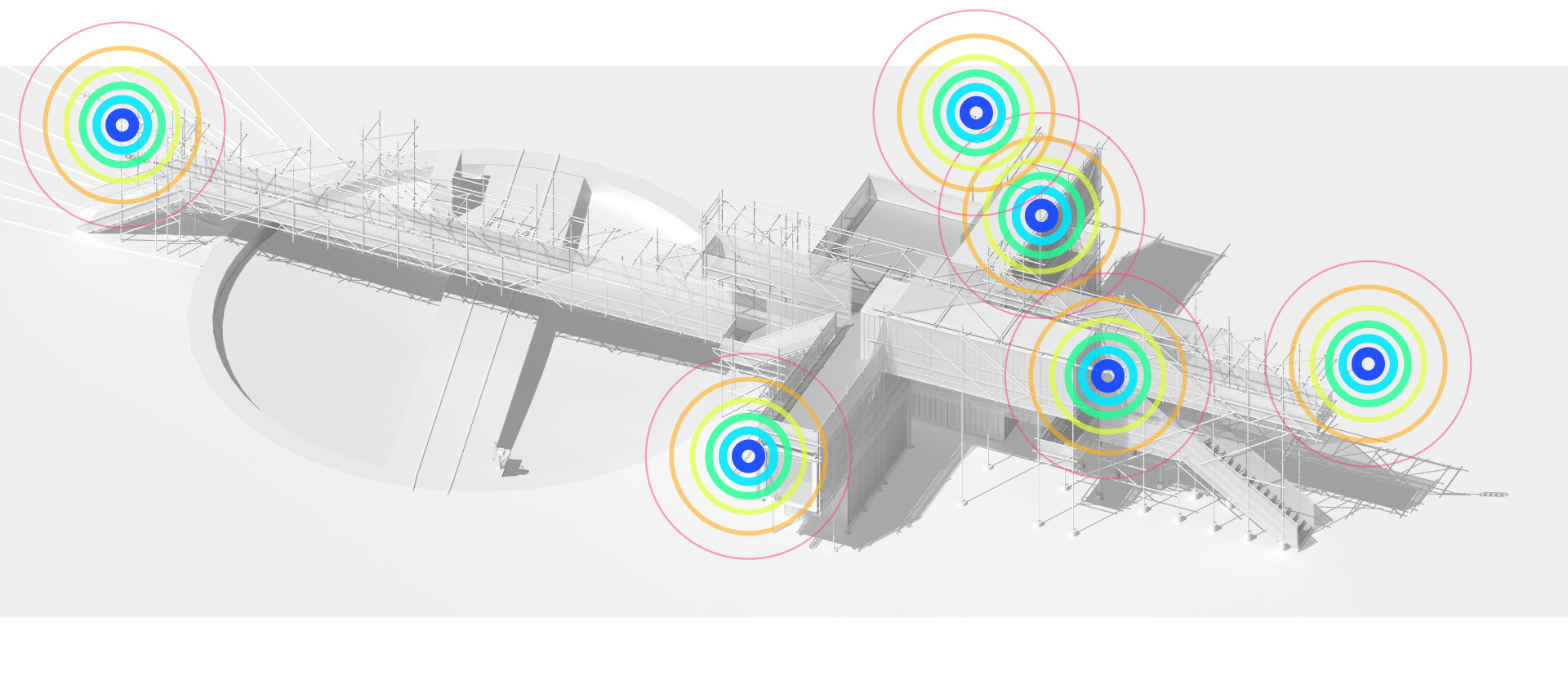

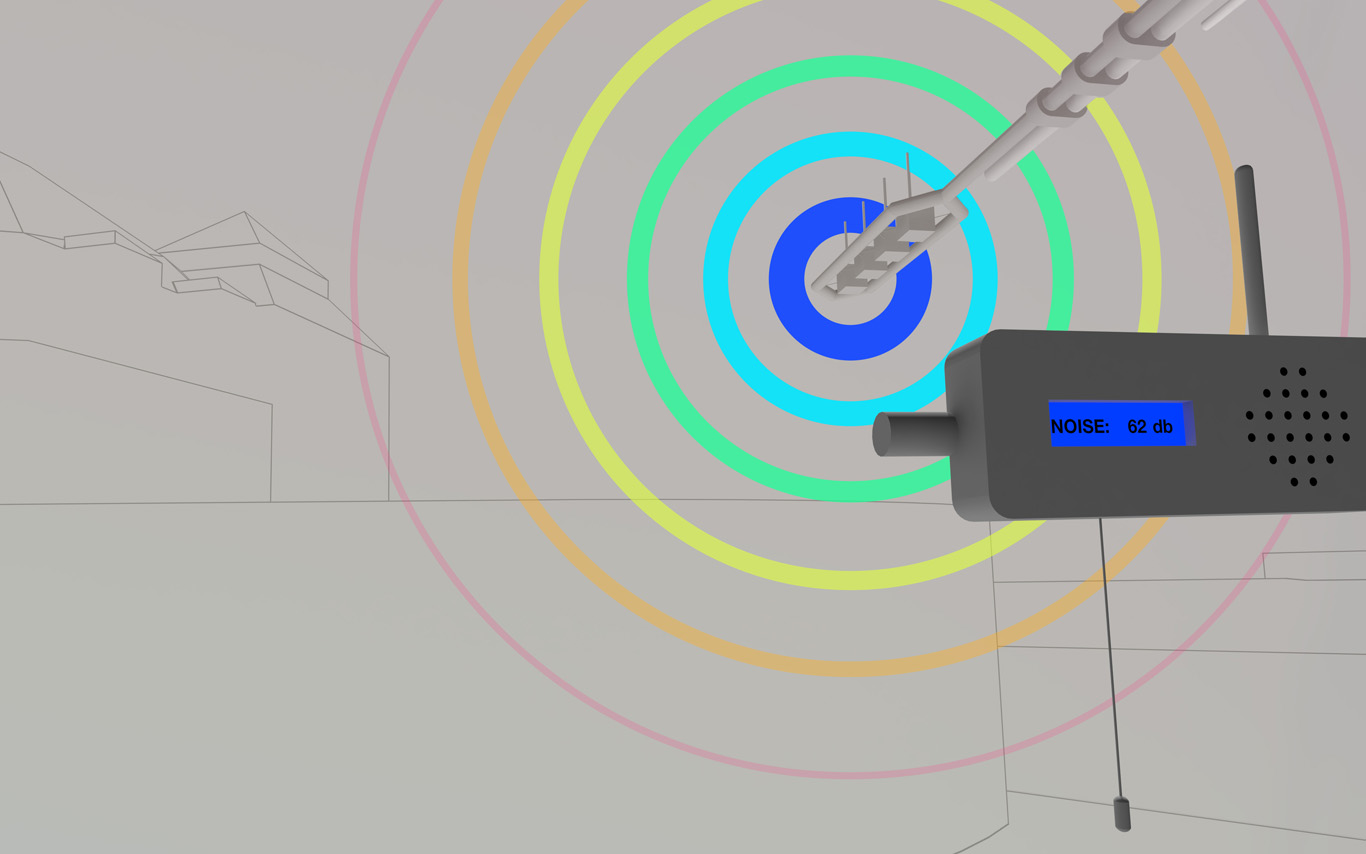

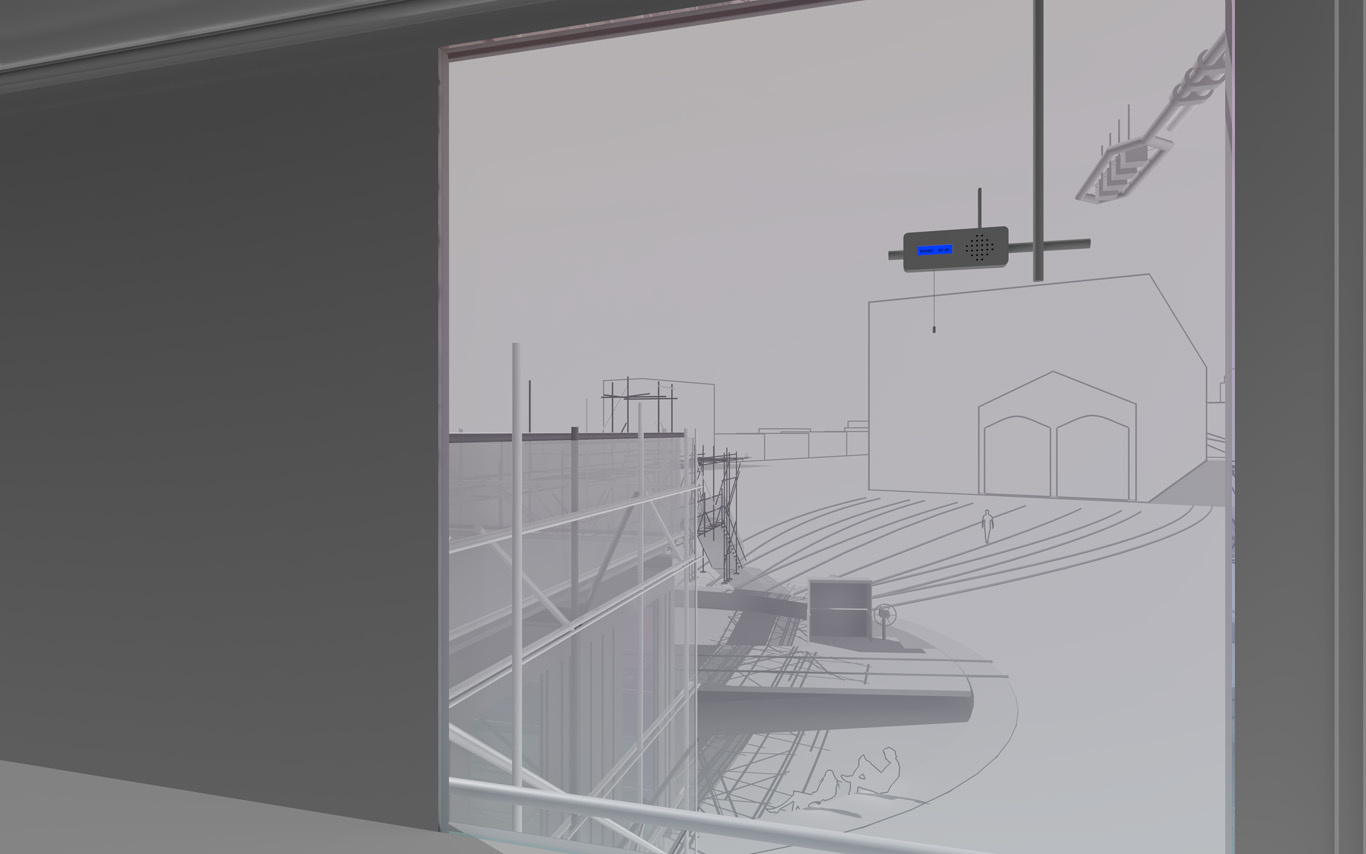

Several areas are linked to monitoring activities (input devices) and/or displays (in red, top -- that concern interests points and views from the platform or elsewhere --). These areas consist in localized devices on the platform itself (5 locations), satellite ones directly implented in the three construction sites or even in distant cities of the larger political area --these are rather output devices-- concerned by the new constructions (three museums, two new large public squares, a new railway station and a new metro). Inspired by the prior similar installation in a public park during a festival -- Heterochrony (bottom image) --, these raw data can be of different nature: visual, audio, integers from sensors (%, °C, ppm, db, lm, mb, etc.), ...

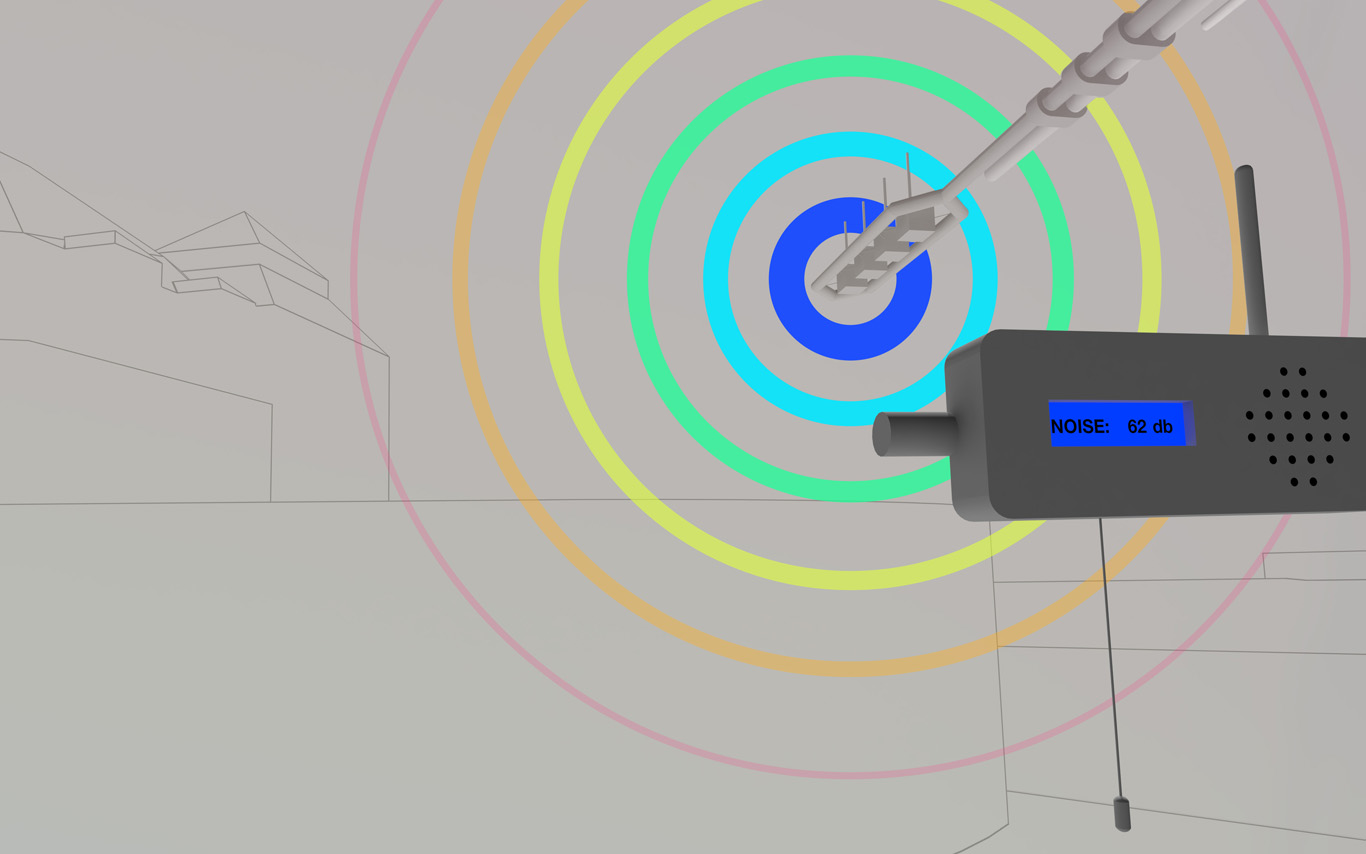

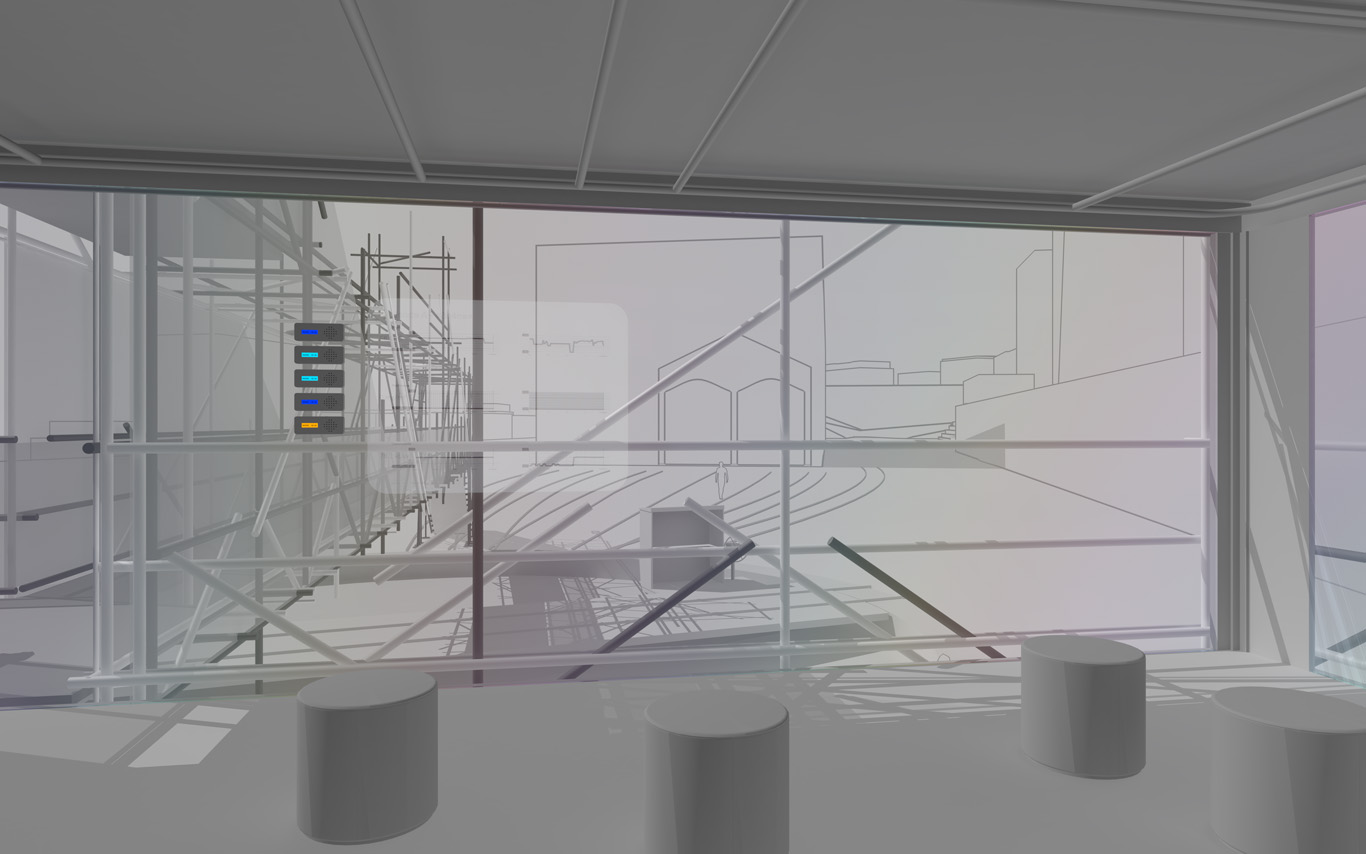

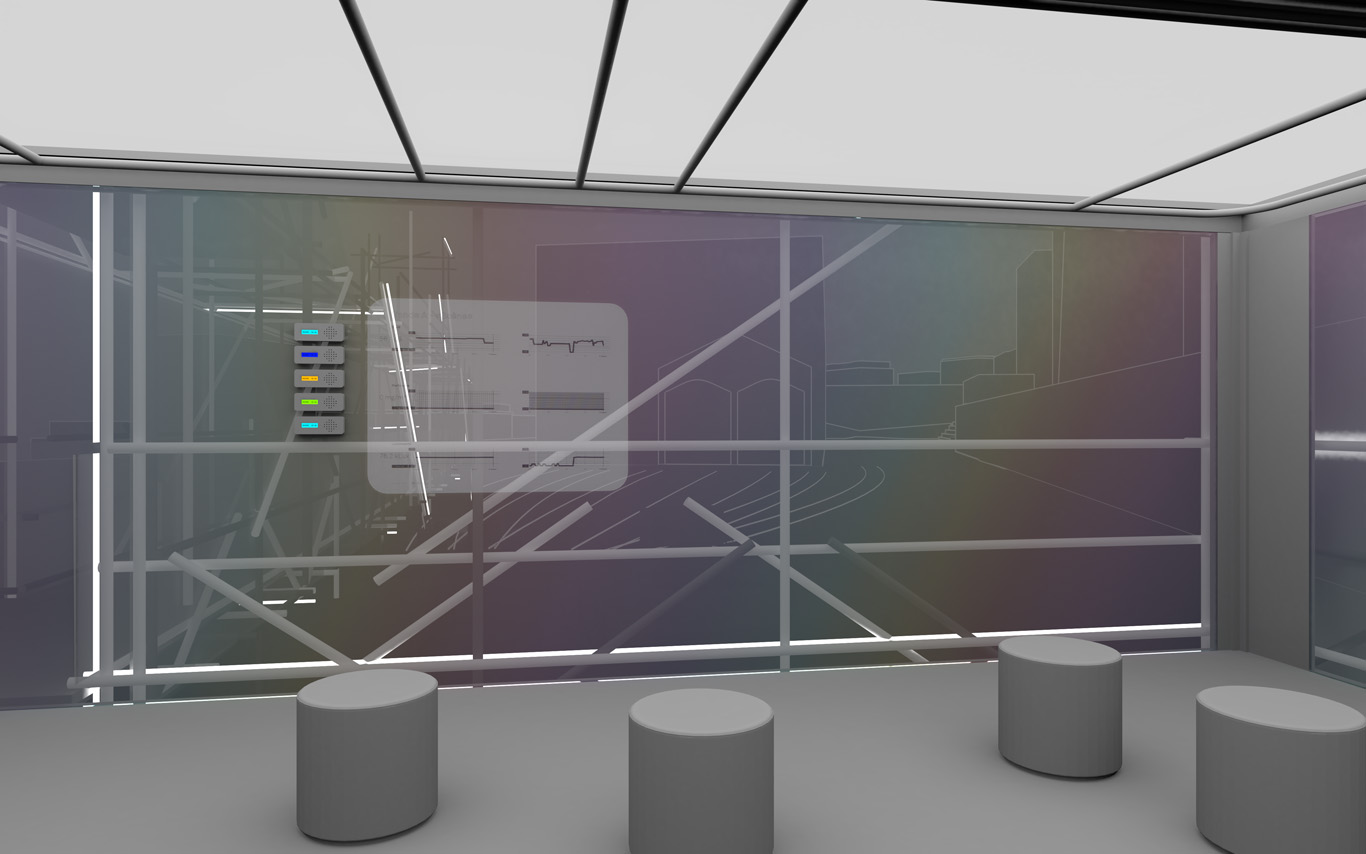

Input and output devices remain low-cost and simple in their expression: several input devices / sensors are placed outside of the pavilion in the structural elements and point toward areas of interest (construction sites or more specific parts of them). Directly in relation with these sensors and the sightseeing spots but on the inside are placed output devices with their recognizable blue screens. These are mainly voice interfaces: voice outputs driven by one bot according to architectural "scores" or algorithmic rules (middle image). Once the rules designed, the "architectural system" runs on its own. That's why we've also named the system based on automated bots "Ar.I." It could stand for "Architectural Intelligence", as it is entirely part of the architectural project.

The coding of the "Ar.I." and use of data has the potential to easily become something more experimental, transformative and performative along the life of PPoFT.

Observers (users) and their natural "curiosity" play a central role: preliminary observations and monitorings are indeed the ones produced in an analog way by them (eyes and ears), in each of the 5 interesting points and through their wanderings. Extending this natural interest is a simple cord in front of each "output device" that they can pull on, which will then trigger a set of new measures by all the related sensors on the outside. This set new data enter the database and become readable by the "Ar.I."

The whole part of the project regarding interaction and data treatments has been subject to a dedicated short study (a document about this study can be accessed here --in French only--). The main design implications of it are that the "Ar.I." takes part in the process of "filtering" which happens between the "outside" and the "inside", by taking part to the creation of a variable but specific "inside atmosphere" ("artificial artificial", as the outside is artificial as well since the anthropocene, isn't it ?) By doing so, the "Ar.I." bot fully takes its own part to the architecture main program: triggering the perception of an inside, proposing patterns of occupations.

"Ar.I." computes spatial elements and mixes times. It can organize configurations for the pavilion (data, displays, recorded sounds, lightings, clocks). It can set it to a past, a present, but also a future estimated disposition. "Ar.I." is mainly a set of open rules and a vocal interface, at the exception of the common access and conference space equipped with visual displays as well. "Ar.I." simply spells data at some times while at other, more intriguingly, it starts give "spatial advices" about the environment data configuration.

In parallel to Public Platform of Future Past and in the frame of various research or experimental projects, scientists and designers at fabric | ch have been working to set up their own platform for declaring and retrieving data (more about this project, Datadroppers, here). A platform, simple but that is adequate to our needs, on which we can develop as desired and where we know what is happening to the data. To further guarantee the nature of the project, a "data commune" was created out of it and we plan to further release the code on Github.

In tis context, we are turning as well our own office into a test tube for various monitoring systems, so that we can assess the reliability and handling of different systems. It is then the occasion to further "hack" some basic domestic equipments and turn them into sensors, try new functions as well, with the help of our 3d printer in tis case (middle image). Again, this experimental activity is turned into a side project, Studio Station (ongoing, with Pierre-Xavier Puissant), while keeping the general background goal of "concept-proofing" the different elements of the main project.

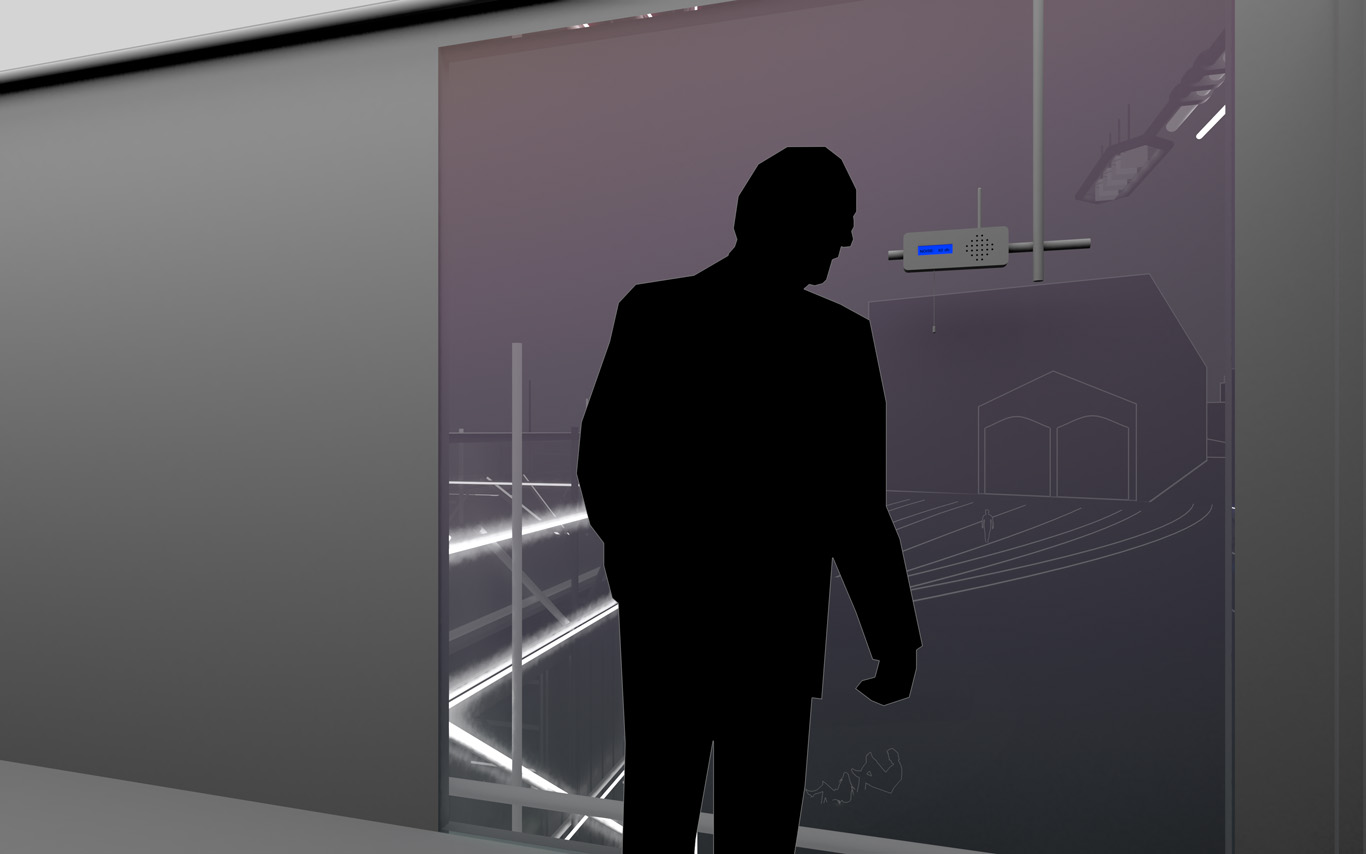

A common room (conference room) in the pavilion hosts and displays the various data. 5 small screen devices, 5 voice interfaces controlled for the 5 areas of interests and a semi-transparent data screen. Inspired again by what was experimented and realized back in 2012 during Heterochrony (top image).

----- ----- -----

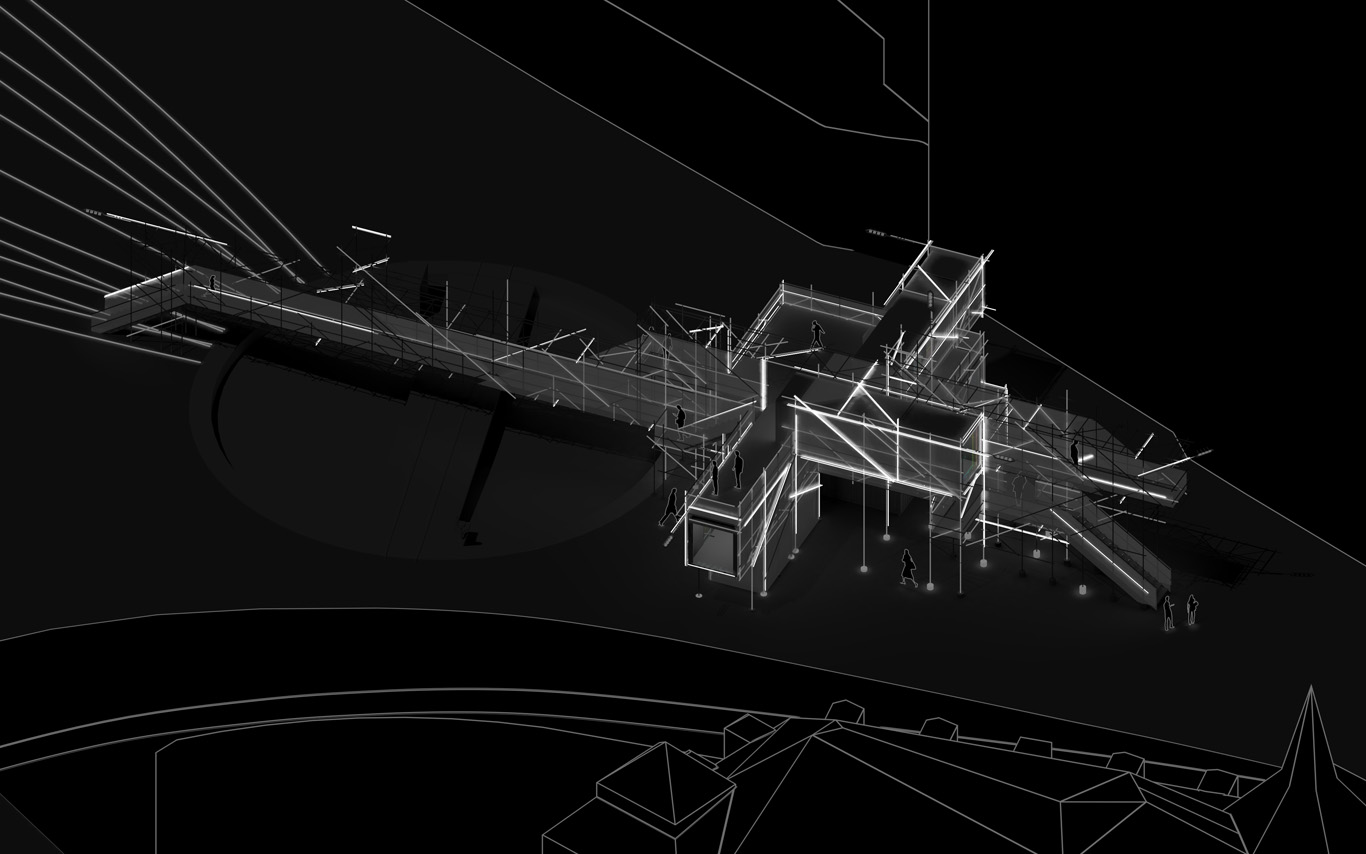

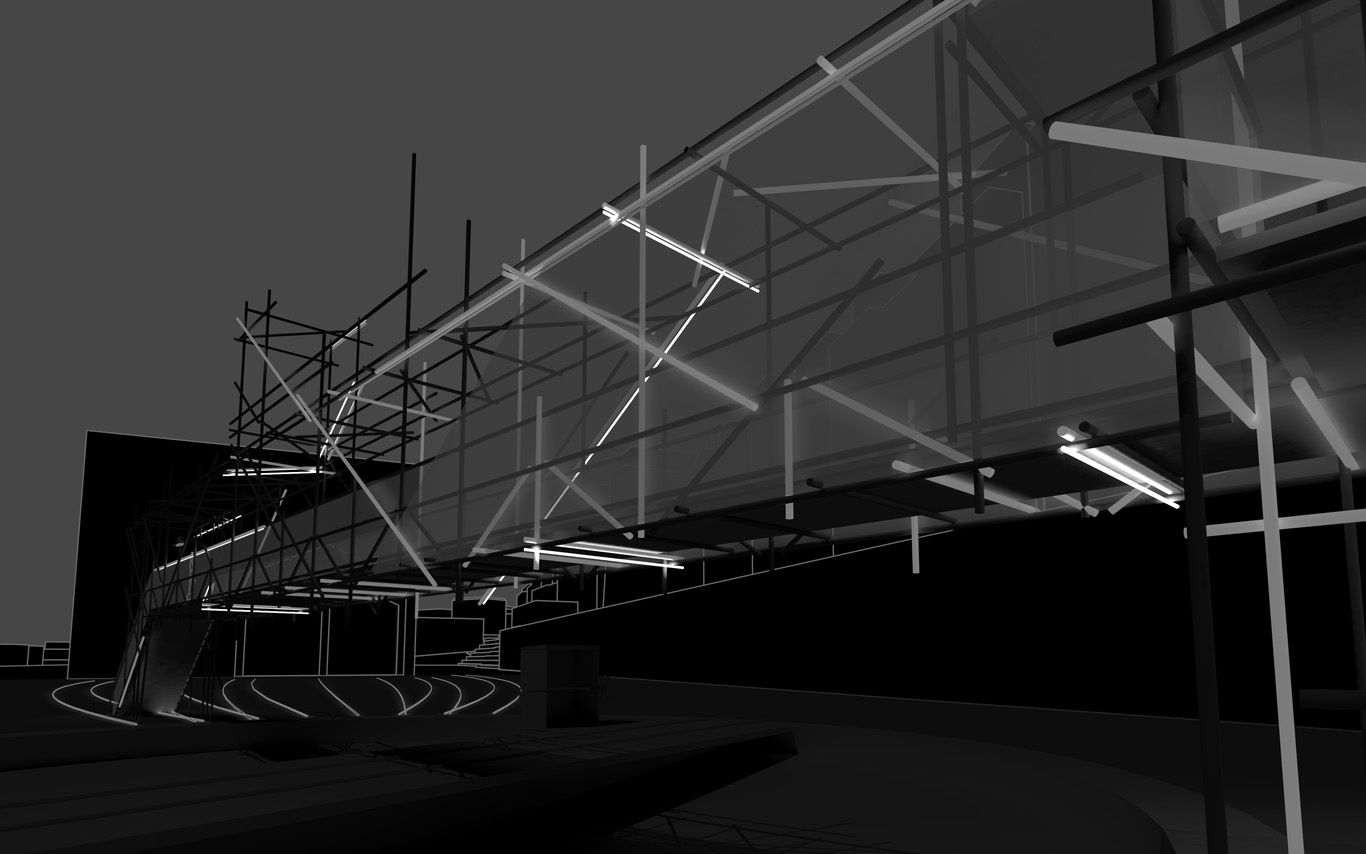

PPoFP, several images. Day, night configurations & few comments

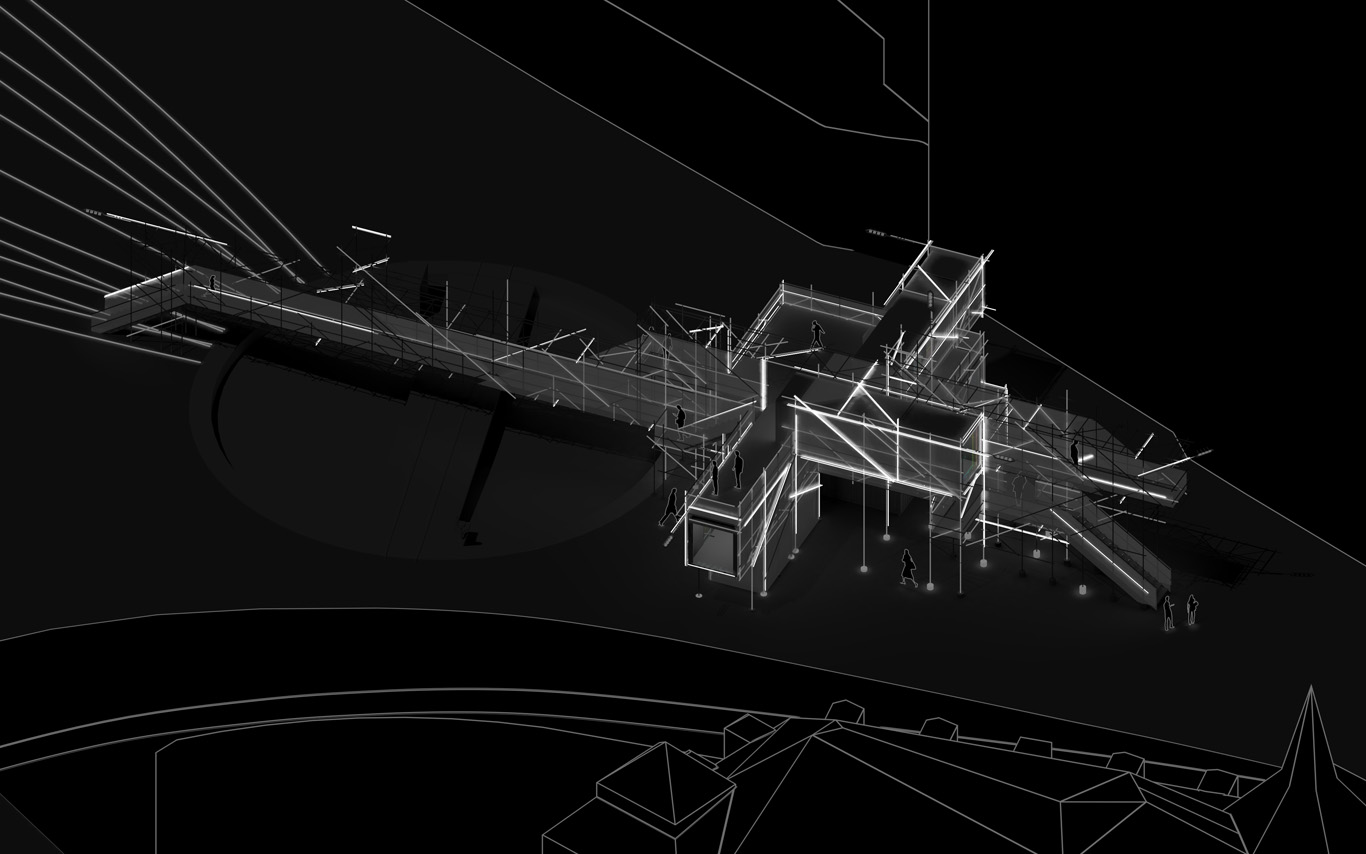

Public Platform of Future-Past, axonometric views day/night.

.jpg)

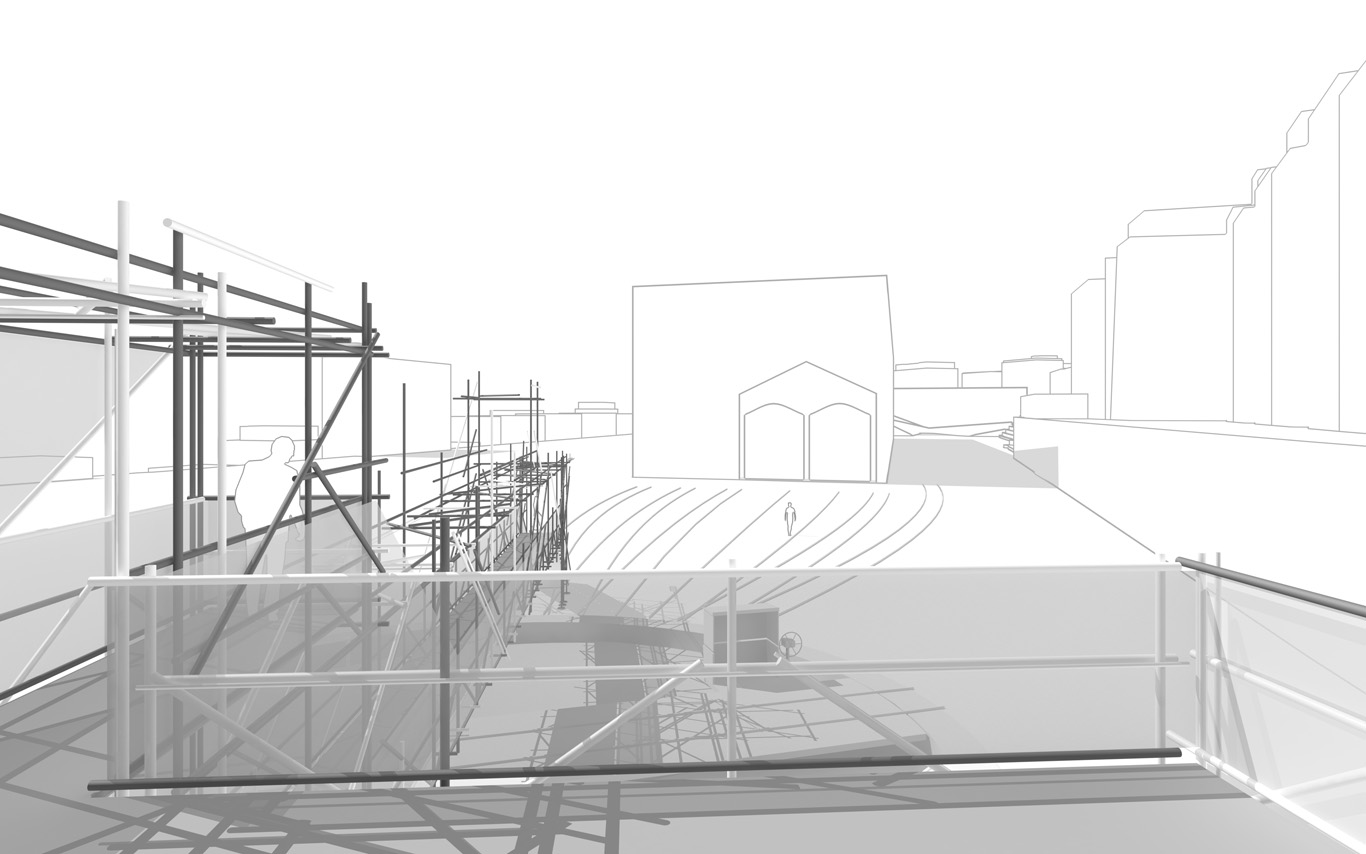

An elevated walkway that overlook the almost archeological site (past-present-future). The circulations and views define and articulate the architecture and the five main "points of interests". These mains points concentrates spatial events, infrastructures and monitoring technologies. Layer by layer, the suroundings are getting filtrated by various means and become enclosed spaces.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Walks, views over transforming sites, ...

Data treatment, bots, voice and minimal visual outputs.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Night views, circulations, points of view.

Night views, ground.

.jpg)

Random yet controllable lights at night. Underlined areas of interests, points of "spatial densities".

Project: fabric | ch

Team: Patrick Keller, Christophe Guignard, Christian Babski, Sinan Mansuroglu, Yves Staub, Nicolas Besson.

Thursday, June 23. 2016

Note: we've been working recently at fabric | ch on a project that we couldn't publish or talk about for contractual reasons... It concerned a relatively large information pavilion we had to create for three new museums in Switzerland (in Lausanne) and a renewed public space (railway station square). This pavilion was supposed to last for a decade, or a bit longer. The process was challenging, the work was good (we believed), but it finally didn't get build...

Sounds sad but common isn't it?

...

We'll see where these many "..." will lead us, but in the meantime and as a matter of documentation, let's stick to the interesting part and publish a first report about this project.

It consisted in an evolution of a prior spatial installation entitled Heterochrony (pdf). A second post will follow soon with the developments of this competition proposal. Both posts will show how we try to combine small size experiments (exhibitions) with more permanent ones (architecture) in our work. It also marks as well our desire at fabric | ch to confront more regularly our ideas and researches with architectural programs.

This first post only consists in a few snapshots of the competition documents, while the following one should present the "final" project and ideas linked to it.

By fabric | ch

-----

.jpg)

.jpg) .jpg)

On the jury paper was written, under "price" -- as we didn't get paid for the 1st price itself -- : "Réalisation" (realization).

Just below in the same letter, "according to point 1.5 of the competition", no realization will be attributed... How ironic! We did work further on an extended study though.

A few words about the project taken from its presentation:

" (...) This platform with physically moving parts could almost be considered an archaeological footbridge or an unknown scientific device, reconfigurable and shiftable, overlooking and giving to see some past industrial remains, allowing to document the present, making foresee the future.

The pavilion, or rather pavilions, equipped with numerous sensor systems, could equally be considered an "architecture of documentation" and interaction, in the sense that there will be extensive data collected to inform in an open and fluid manner over the continuous changes on the sites of construction and tranformations. Taken from the various "points of interets' on the platform, these data will feed back applications ("architectural intelligence"?), media objects, spatial and lighting behaviors. The ensemble will play with the idea of a combination of various time frames and will combine the existing, the imagined and the evanescent. (...) "

Heterochrony, a previous installation that followed similar goals, back in 2012. http://www.heterochronie.cc

Download pdf (14 mb).

-----

Project: fabric | ch

Team: Patrick Keller, Christophe Guignard, Sinan Mansuroglu, Nicolas Besson.

Tuesday, June 07. 2016

Note: I've posted several articles about automation recently. This was the occasion to continue collect some thoughts about the topic (automation then) so as the larger social implications that this might trigger.

But it was also a "collection" that took place at a special moment in Switzerland when we had to vote about the "Revenu the Base Inconditionnel" (Unconditional Basic Income). I mentioned it in a previous post ("On Algorithmic Communism"), in particular the relation that is often made between this idea (Basic Income / Universal Income) and the probable evolution of work in the decades to come (less work for "humans" vs. more for "robots").

Well, the campain and votation triggered very interesting debates among the civil population, but in the end and predictably, the idea was largely rejected (~25% of the voters accepted it, with some small geographical areas that indeed acceted it at more than 50% --urban areas mainly--. Some where not so far, for exemple the city capital, Bern, voted at 40% for the RBI).

This was very new and a probably too (?) early question for the Swiss population, but it will undoubtedly become a growing debate in the decades to come. A question that has many important associated stakes.

-----

Press talking about the RBI, image from RTS website.

More about it (in French) on the website of the swiss television.

Tuesday, May 24. 2016

Note: even people developing automation will be automated, so to say...

Do you want to change this existing (and predictable) future? This would be the right time to come with counter-proposals then...

But I'm quite surprized by the absence of nuanced analysis in the Wired article btw (am I? further than "make the workd a better place" I mean): indeed, this is a scientific achievement, but then what? no stakes? no social issues? It seems to be the way things should go then... (and some people know pretty well how "The Way Things Go", always wrong ;)), to the point that " No, Asimo isn’t quite as advanced—or as frightening—as Skynet." Good to know!

Via Wired

-----

By Cade Metz

Deep neural networks are remaking the Internet. Able to learn very human tasks by analyzing vast amounts of digital data, these artificially intelligent systems are injecting online services with a power that just wasn’t viable in years past. They’re identifying faces in photos and recognizing commands spoken into smartphones and translating conversations from one language to another. They’re even helping Google choose its search results. All this we know. But what’s less discussed is how the giants of the Internet go about building these rather remarkable engines of AI.

Part of it is that companies like Google and Facebook pay top dollar for some really smart people. Only a few hundred souls on Earth have the talent and the training needed to really push the state-of-the-art forward, and paying for these top minds is a lot like paying for an NFL quarterback. That’s a bottleneck in the continued progress of artificial intelligence. And it’s not the only one. Even the top researchers can’t build these services without trial and error on an enormous scale. To build a deep neural network that cracks the next big AI problem, researchers must first try countless options that don’t work, running each one across dozens and potentially hundreds of machines.

“It’s almost like being the coach rather than the player,” says Demis Hassabis, co-founder of DeepMind, the Google outfit behind the history-making AI that beat the world’s best Go player. “You’re coaxing these things, rather than directly telling them what to do.”

That’s why many of these companies are now trying to automate this trial and error—or at least part of it. If you automate some of the heavily lifting, the thinking goes, you can more rapidly push the latest machine learning into the hands of rank-and-file engineers—and you can give the top minds more time to focus on bigger ideas and tougher problems. This, in turn, will accelerate the progress of AI inside the Internet apps and services that you and I use every day.

In other words, for computers to get smarter faster, computers themselves must handle even more of the grunt work. The giants of the Internet are building computing systems that can test countless machine learning algorithms on behalf of their engineers, that can cycle through so many possibilities on their own. Better yet, these companies are building AI algorithms that can help build AI algorithms. No joke. Inside Facebook, engineers have designed what they like to call an “automated machine learning engineer,” an artificially intelligent system that helps create artificially intelligent systems. It’s a long way from perfection. But the goal is to create new AI models using as little human grunt work as possible.

Feeling the Flow

After Facebook’s $104 billion IPO in 2012, Hussein Mehanna and other engineers on the Facebook ads team felt an added pressure to improve the company’s ad targeting, to more precisely match ads to the hundreds of millions of people using its social network. This meant building deep neural networks and other machine learning algorithms that could make better use of the vast amounts of data Facebook collects on the characteristics and behavior of those hundreds of millions of people.

According to Mehanna, Facebook engineers had no problem generating ideas for new AI, but testing these ideas was another matter. So he and his team built a tool called Flow. “We wanted to build a machine-learning assembly line that all engineers at Facebook could use,” Mehanna says. Flow is designed to help engineers build, test, and execute machine learning algorithms on a massive scale, and this includes practically any form of machine learning—a broad technology that covers all services capable of learning tasks largely on their own.

Basically, engineers could readily test an endless stream of ideas across the company’s sprawling network of computer data centers. They could run all sorts of algorithmic possibilities—involving not just deep learning but other forms of AI, including logistic regression to boosted decision trees—and the results could feed still more ideas. “The more ideas you try, the better,” Mehanna says. “The more data you try, the better.” It also meant that engineers could readily reuse algorithms that others had built, tweaking these algorithms and applying them to other tasks.

Soon, Mehanna and his team expanded Flow for use across the entire company. Inside other teams, it could help generate algorithms that could choose the links for your Faceboook News Feed, recognize faces in photos posted to the social network, or generate audio captions for photos so that the blind can understand what’s in them. It could even help the company determine what parts of the world still need access to the Internet.

With Flow, Mehanna says, Facebook trains and tests about 300,000 machine learning models each month. Whereas it once rolled a new AI model onto its social network every 60 days or so, it can now release several new models each week.

The Next Frontier

The idea is far bigger than Facebook. It’s common practice across the world of deep learning. Last year, Twitter acquired a startup, WhetLab, that specializes in this kind of thing, and recently, Microsoft described how its researchers use a system to test a sea of possible AI models. Microsoft researcher Jian Sun calls it “human-assisted search.”

Mehanna and Facebook want to accelerate this. The company plans to eventually open source Flow, sharing it with the world at large, and according to Mehanna, outfits like LinkedIn, Uber, and Twitter are already interested in using it. Mehanna and team have also built a tool called AutoML that can remove even more of the burden from human engineers. Running atop Flow, AutoML can automatically “clean” the data needed to train neural networks and other machine learning algorithms—prepare it for testing without any human intervention—and Mehanna envisions a version that could even gather the data on its own. But more intriguingly, AutoML uses artificial intelligence to help build artificial intelligence.

As Mehana says, Facebook trains and tests about 300,000 machine learning models each month. AutoML can then use the results of these tests to train another machine learning model that can optimize the training of machine learning models. Yes, that can be a hard thing to wrap your head around. Mehanna compares it to Inception. But it works. The system can automatically chooses algorithms and parameters that are likely to work. “It can almost predict the result before the training,” Mehanna says.

Inside the Facebook ads team, engineers even built that automated machine learning engineer, and this too has spread to the rest of the company. It’s called Asimo, and according to Facebook, there are cases where it can automatically generate enhanced and improved incarnations of existing models—models that human engineers can then instantly deploy to the net. “It cannot yet invent a new AI algorithm,” Mehanna says. “But who knows, down the road…”

It’s an intriguing idea—indeed, one that has captivated science fiction writers for decades: an intelligent machine that builds itself. No, Asimo isn’t quite as advanced—or as frightening—as Skynet. But it’s a step toward a world where so many others, not just the field’s sharpest minds, will build new AI. Some of those others won’t even be human.

Thursday, April 21. 2016

Note: the idea of automation is very present again recently. And it is more and more put together with the related idea of a society without work, or insufficient work for everyone --which is already the case in the liberal way of thinking btw--, as most of it would be taken by autonomous machines, AIs, etc.

Many people are warning about this (Bill Gates among them, talking precisely about "software substitution"), some think about a "universal income" as a possible response, some say we shouldn't accept this and use our consumer power to reject such products (we spoke passionatey about it with my good old friend Eric Sadin last week during a meal at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, while drinking --almost automatically as well-- some good wine), some say it is almost too late and we should plan and have visions for what is coming upon us...

Now comes also an exhibition about the same subject at Kunsthalle Wien that tries to articulate the questions: "Technical devices that were originally designed to serve and assist us and are now getting smarter and harder to control and comprehend. Does their growing autonomy mean that the machines will one day overpower us? Or will they remain our subservient little helpers, our gateway to greater knowledge and sovereignty?"

Via WMMNA

-----

Installation view The Promise of Total Automation. Image Kunsthalle Wien

Cécile B. Evans, How happy a Thing Can Be, 2014. Image Kunsthalle Wien

The word ‘automation’ is appearing in places that would have seemed unlikely to most people less than a decade ago: journalism, art, design or law. Robots and algorithms are being increasingly convincing at doing things just like humans. And sometimes even better than humans.

The Promise of Total Automation, an exhibition recently opened at Kunsthalle Wien in Vienna, looks at our troubled relationship with machines. Technical devices that were originally designed to serve and assist us and are now getting smarter and harder to control and comprehend. Does their growing autonomy mean that the machines will one day overpower us? Or will they remain our subservient little helpers, our gateway to greater knowledge and sovereignty?

The “promise of total automation” was the battle cry of Fordism. What we nowadays call “technology” is an already co-opted version of it, being instrumentalised for production, communication, control and body-enhancements, that is for a colonisation and rationalisation of space, time and minds. Still technology cannot be reduced to it. In the exhibition, automation, improvisation and sense of wonder are not opposed but sustain each other. The artistic positions consider technology as complex as it is, animated at the same time by rational and irrational dynamics.

The Promise of Total Automation is an intelligent, inquisitive and engrossing exhibition. Its investigation into the tensions and dilemmas of human/machines relationship explore themes that go from artificial intelligence to industrial aesthetics, from bio-politics to theories of conspiracy, from e-waste to resistance to innovation, from archaeology of digital communication to utopias that won’t die.

The show is dense in information and invitations to ponder so don’t forget to pick up one of the free information booklet at the entrance of the show. You’re going to need it!

A not-so-quick walk around the show:

James Benning, Stemple Pass, 2012

James Benning‘s film Stemple Pass is made of four static shots, each from the same angle and each 30 minutes long, showing a cabin in the middle of a forest in spring, fall, winter and summer. The modest building is a replica of the hideout of anti-technology terrorist Ted Kaczynski. The soundtrack alternates between the ambient sound of the forest and Benning reading from the Unabomber’s journals, encrypted documents and manifesto.

Kaczynski’s texts hover between his love for nature and his intention to destroy and murder. Between his daily life in the woods and his fears that technology is going to turn into an instrument that enables the powerful elite to take control over society. What is shocking is not so much the violence of his words because you expect them. It’s when he gets it right that you get upset. When he expresses his distrust of the merciless rise of technology, his doubts regarding the promises of innovation and it somehow makes sense to you.

Konrad Klapheck, Der Chef, 1965. Photo: © Museum Kunstpalast – ARTOTHEK

Konrad Klapheck’s paintings ‘portray’ devices that were becoming mainstream in 1960s households: vacuum cleaner, typewriters, sewing machines, telephones, etc. In his works, the objects are abstracted from any context, glorified and personified. In the typewriter series, he even assigns roles to the objects. They are Herrscher (ruler), Diktator, Gesetzgeber (lawgiver) or Chef (boss.) These titles allude to the important role that the instruments have taken in administrative and economic systems.

Tyler Coburn, Sabots, 2016, courtesy of the artist, photo: David Avazzadeh

This unassuming small pair of 3D-printed clogs alludes to the workers struggles of the Industrial Revolution. The title of the piece, Sabots, means clogs in french. The word sabotage allegedly comes from it. The story says that when French farmers left the countryside to come and work in factories they kept on wearing their peasant clogs. These shoes were not suited for factory works and as a consequence, the word ‘saboter’ came to mean ‘to work clumsily or incompetently’ or ‘to make a mess of things.’ Another apocryphal story says that disgruntled workers blamed the clogs when they damaged or tampered machinery. Another version saw the workers throwing their clogs at the machine to destroy it.

In the early 20th century, labor unions such as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) advocated withdrawal of efficiency as a means of self-defense against unfair working conditions. They called it sabotage.

Tyler Coburn, Waste Management, 2013-15

Tyler Coburn contributed another work to the show. Waste Management looks like a pair of natural stones but the rocks are actually made out of electronic waste, more precisely the glass from old computer monitors and fiber powder from printed circuit boards that were mixed with epoxy and then molded in an electronic recycling factory in Taiwan. The country is not only a leader in the export of electronics, but also in the development of e-waste processing technologies that turn electronic trash into architectural bricks, gold potassium cyanide, precious metals—and even artworks such as these rocks. Coburn bought them there as a ready made. They evoke the Chinese scholar’s rocks. By the early Song dynasty (960–1279), the Chinese started collecting small ornamental rocks, especially the rocks that had been sculpted naturally by processes of erosion.

Coburn’s rocks are thus artificial objects that crave an aesthetic value that can only come from natural objects.

Accompanying these objects is a printed broadsheet which narrates the circulation and transformation of a CRT monitor into the stone artworks. The story follows from the “it-narrative” or novel of circulation, a sub-genre of 18th Century literature, in which currencies and commodities narrated their circulation within a then-emerging global economy.

Osborne & Felsenstein, Personal Computer Osborne 1a and Monitor NEC, 1981, Loan Vienna Technical Museum, photo: David Avazzadeh

Adam Osborne and Lee Felsenstein, Personal Computer Osborne 1a, 1981, Courtesy Technisches Museum, Wien

Several artifacts ground the exhibition into the technological and cultural history of automation: A mechanical Jacquard loom, often regarded as a key step in the history of computing hardware because of the way it used punched cards to control operations. A mysterious-looking arithmometer, the first digital mechanical calculator reliable enough to be used at the office to automate mathematical calculations. A Morse code telegraph, the first invention to effectively exploit electromagnetism for long-distance communication and thus a pioneer of digital communication. A cybernetic model from 1956 (see further below) and the first ‘portable’ computer.

Released in 1981 by Osborne Computer Corporation, the Osborne 1 was the first commercially successful portable microcomputer. It weighed 10.7 kg (23.5 lb), cost $1,795 USD, had a tiny screen (5-inch/13 cm) and no battery.

At the peak of demand, Osborne was shipping over 10,000 units a month. However, Osborne Computer Corporation shot itself in the foot when they prematurely announced the release of their next generation models. The news put a stop to the sales of the current unit, contributing to throwing the company into bankruptcy. This has comes to be known as the Osborne effect.

Kybernetisches Modell Eier: Die Maus im Labyrinth (Cybernetics Model Eier: The Mouse in the Maze), 1956. Image Kunsthalle Wien

Around 1960, scientists started to build cybernetic machines in order to study artificial intelligence. One of these machines was a maze-solving mouse built by Claude E. Shannon to study the labyrinthian path that a call made using telephone switching systems should take to reach its destination. The device contained a maze that could be arranged to create various paths. The system followed the idea of Ariadne’s thread, the mouse marking each field with the path information, like the Greek mythological figure did when she helped Theseus find his way out of the Minotaur’s labyrinth. Richard Eier later re-built the maze-solving mouse and improved Shannon’s method by replacing the thread with two two-bits memory units.

Régis Mayot, JEANNE & CIE, 2015. Image Kunsthalle Wien

In 2011, the CIAV (the international center for studio glass in Meisenthal, France) invited Régis Mayot to work in their studios. The designer decided to explore the moulds themselves, rather than the objects that were produced using them. By a process of sand moulding, the designer revealed the mechanical beauty of some of these historical tools, producing prints of a selection of moulds that were then blown by craftsmen in glass.

Jeanne et Cie (named after one of the moulds chosen by the designer) highlights how the aesthetics of objects are the result of the industrial instruments and processes that enter into their manufacturing.

Bureau d’études, ME, 2013, © Léonore Bonaccini and Xavier Fourt

Bureau d’Etudes, Electromagnetic Propaganda, 2010

The exhibition also presented a selection of Bureau d´Études‘ intricate and compelling cartographies that visualize covert connections between actors and interests in contemporary political, social and economic systems. Because knowledge is power, the maps are meant as instruments that can be used as part of social movements. The ones displayed at Kunsthalle Wien included the maps of Electro-Magnetic Propaganda, Government of the Agro-Industrial System and the 8th Sphere.

I fell in love with Mark Leckey‘s video. So much that i’ll have to dedicate another post to his work. One day.

David Jourdan, Untitled, 2016, © David Jourdan

David Jourdan’s poster alludes to an ad in which newspaper Der Standard announced that its digital format was ‘almost as good as paper.’

More images from the exhibition:

Magali Reus, Leaves, 2015

Thomas Bayrle, Kleiner koreanischer Wiper

Juan Downey, Nostalgic Item, 1967, Estate of Joan Downey courtesy of Marilys B. Downey, photo: David Avazzadeh

Judith Fegerl, still, 2013, © Judith Fegerl, Courtesy Galerie Hubert Winter, Wien

Wesley Meuris, Biotechnology & Genetic Engineering, 2014. Image Kunsthalle Wien

Installation view The Promise of Total Automation. Image Kunsthalle Wien

Installation view. Image Kunsthalle Wien

Installation view. Image Kunsthalle Wien

More images on my flickr album.

Also in the exhibition: Prototype II (after US patent no 6545444 B2) or the quest for free energy.

The Promise of Total Automation was curated by Anne Faucheret. The exhibition is open until 29 May at Kunsthalle Wien in Vienna. Don’t miss it if you’re in the area.

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)