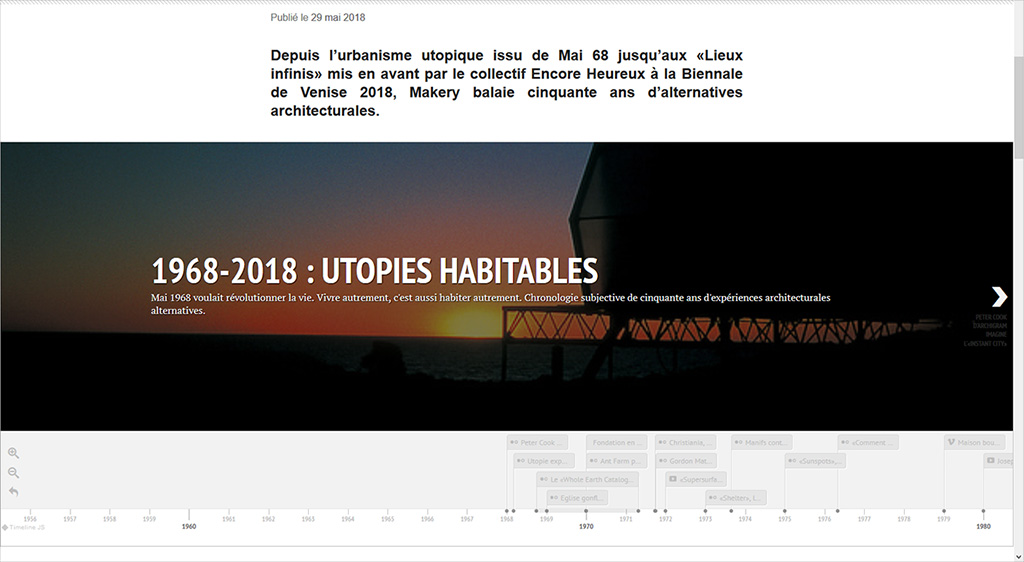

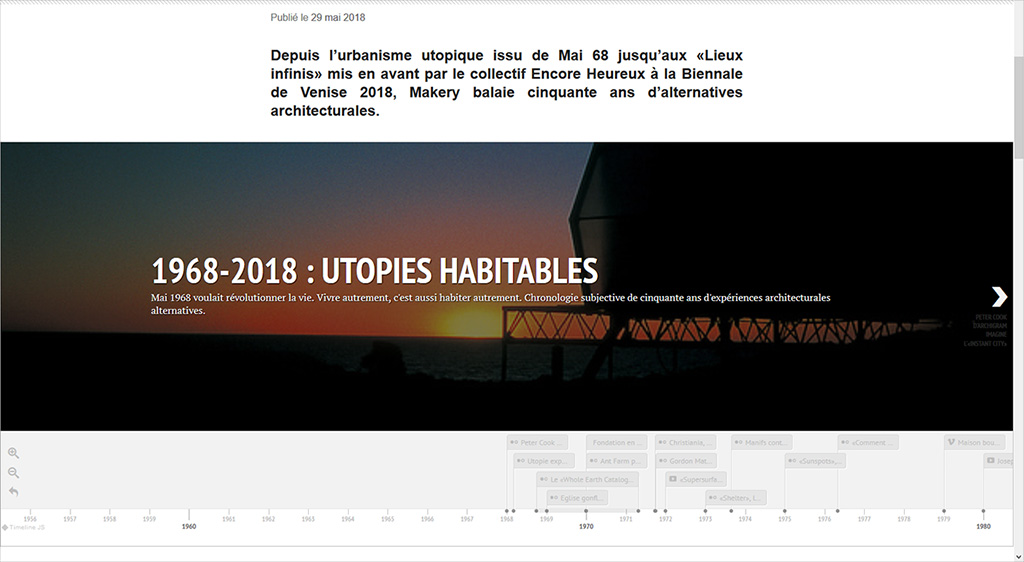

Note: As a direct follow-up to the May 1968 celebrations, Makery published (in French) an article retracing a history of "inhabitable utopias", or different architectures that have since been experimented with or thought about.

The short article is mainly illustrated with an interactive timeline presenting these experiments carried out over the past 50 years.

Via Makery

-----

Depuis l’urbanisme utopique issu de Mai 68 jusqu’aux «Lieux infinis» mis en avant par le collectif Encore Heureux à la Biennale de Venise 2018, Makery balaie cinquante ans d’alternatives architecturales.

En savoir plus:

La webographie suit le déroulé de la chronologie ci-dessus.

L’image qui ouvre cette chronologie est le Makrolab de Marko Peljhan, à Rottnest Island, en Australie, 2000.

---

Instant City, Peter Cook, Archigram, Royaume-Uni, 1968.

« Structures gonflables », exposition au musée d’Art moderne de la ville de Paris, du 1er au 28 mars 1968.

Whole Earth Catalog, édité par Stewart Brand, de 1968 à 1971 aux Etats-Unis.

L’église gonflable de Montigny-lès-Cormeilles, par Hans-Walter Müller, France, 1969.

Inflatocookbook, du collectif Ant Farm, Etats-Unis, 1970.

Le laboratoire urbain d’Arcosanti, Paolo Soleri, Arizona, Etats-Unis, 1970.

La « ville libre » de Christiania, Copenhague, Danemark, 1971.

Le restaurant FOOD de Gordon Matta-Clark, New York, 1971, exposition Gordon Matta-Clark, anarchitecte, musée du Jeu de Paume, du 5 juin au 23 septembre 2018.

Superstudio, agence d’architecture, Italie, 1966-1978.

Shelter, Lloyd Kahn, Etats-Unis, 1973.

Lutte du Larzac, France, 1973-1982.

Sunspots, Steve Baer, Zomeworks, Etats-Unis, 1975.

Comment habiter la terre, Yona Friedman, 1976.

Casa Bola, Eduardo Longo, São Paulo, Brésil, 1979.

Les cabanes de Josep Pujiula à Argelaguer, province de Gérone, Catalogne, Espagne, 1980-2016.

Bolo’Bolo, P.M., 1983.

Le Jardin en mouvement de Gilles Clément, 1985.

Le Magasin à Grenoble, Patrick Bouchain, 1986.

Future Shack, Sean Godsell, Australie, 1985.

Brevétisation du container en habitat par Philip C. Clark, Etats-Unis, 1987.

Black Rock City, la ville éphémère du festival Burning Man, Nevada, Etats-Unis, 1990- .

Le projet A.G. Gleisdreieck, Berlin, Allemagne, 1990- .

Reclaim The Streets, Londres, 1991- .

Castlemorton Common Festival, Royaume-Uni, 1992.

Les maisons en carton de Shigeru Ban, Kobe, Japon, 1995.

Muf (Londres), Stalker (Italie), Coloco (Paris), Bruit du Frigo (Bordeaux), créés en 1996.

Makrolab, Marko Peljhan, Projekt Atol, Slovénie, 1997-2007.

Manifestations de Seattle contre l’Organisation mondiale du commerce, Etats-Unis, 1999.

Ecobox, Atelier d’architecture autogérée, Paris, 2002.

L’architecture du RAB, Exyzt, Paris, France, 2003.

Parking Day, Rebar, San Francisco, Etats-Unis, 2006.

Zone à Défendre, Notre-Dame-des-Landes, France, 2008- .

Tactical Urbanism, Mike Lydon et Anthony Garcia, Island Press, 2015.

Cloud City, Tomás Saraceno, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Etats-Unis, 2012.

Fab City Global, création en 2014 et Fab City Summit, à Paris du 11 au 13 juillet 2018.

Assemble Studio (Royaume-Uni), Turner Prize 2015.

Elemental, Pritzker Prize 2016.

Accueil des migrants porte de la Chapelle, Julien Beller, Paris, 2016-2018.

Mai 68. L’architecture aussi !, Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, Paris, du 16 mai au 17 septembre 2018.

Lieux infinis, agence Encore Heureux, Pavillon français de la Biennale internationale d’architecture de Venise 2018.

----

Direct translation with DeepL (no links):

To know more about it

The webography follows the chronology above.

The image that opens this chronology is Marko Peljhan's Makrolab, Rottnest Island, Australia, 2000.

---

Instant City, Peter Cook, Archigram, United Kingdom, 1968.

"Inflatable structures", exhibition at the Musée d'Art moderne de la ville de Paris, from 1 to 28 March 1968.

Whole Earth Catalog, published by Stewart Brand, from 1968 to 1971 in the United States.

The inflatable church of Montigny-lès-Cormeilles, by Hans-Walter Müller, France, 1969.

Inflatocookbook, by the Ant Farm collective, United States, 1970.

The Arcosanti Urban Laboratory, Paolo Soleri, Arizona, USA, 1970.

The "Free City" of Christiania, Copenhagen, Denmark, 1971.

The FOOD restaurant of Gordon Matta-Clark, New York, 1971, Gordon Matta-Clark exhibition, an architect, Jeu de Paume museum, from June 5 to September 23, 2018.

Superstudio, architectural firm, Italy, 1966-1978.

Shelter, Lloyd Kahn, United States, 1973.

Larzac struggle, France, 1973-1982.

Sunspots, Steve Baer, Zomeworks, USA, 1975.

How to Live on the Earth, Yona Friedman, 1976.

Casa Bola, Eduardo Longo, São Paulo, Brazil, 1979.

Josep Pujiula's huts in Argelaguer, province of Girona, Catalonia, Spain, 1980-2016.

Bolo'Bolo, P.M., 1983.

Le Jardin en mouvement by Gilles Clément, 1985.

Le Magasin à Grenoble, Patrick Bouchain, 1986.

Future Shack, Sean Godsell, Australia, 1985.

Patenting of the container in housing by Philip C. Clark, United States, 1987.

Black Rock City, the ephemeral city of the Burning Man festival, Nevada, USA, 1990- .

The A.G. Gleisdreieck project, Berlin, Germany, 1990- .

Reclaim The Streets, London, 1991- .

Castlemorton Common Festival, United Kingdom, 1992.

The cardboard houses of Shigeru Ban, Kobe, Japan, 1995.

Muf (London), Stalker (Italy), Coloco (Paris), Bruit du Frigo (Bordeaux), created in 1996.

Makrolab, Marko Peljhan, Projekt Atol, Slovenia, 1997-2007.

Seattle demonstrations against the World Trade Organization, United States, 1999.

Ecobox, Atelier d'architecture autogérée, Paris, 2002.

L'architecture du RAB, Exyzt, Paris, France, 2003.

Parking Day, Rebar, San Francisco, USA, 2006.

Zone à Défendre, Notre-Dame-des-Landes, France, 2008- .

Tactical Urbanism, Mike Lydon and Anthony Garcia, Island Press, 2015.

Cloud City, Tomás Saraceno, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, United States, 2012.

Fab City Global, created in 2014 and Fab City Summit, in Paris from 11 to 13 July 2018.

Assemble Studio (United Kingdom), Turner Prize 2015.

Elemental, Pritzker Prize 2016.

Reception of migrants at Porte de la Chapelle, Julien Beller, Paris, 2016-2018.

May 68. Architecture too, Cité de l'architecture et du patrimoine, Paris, from 16 May to 17 September 2018.

Lieux infinis, Encore Heureux agency, French Pavilion at the 2018 Venice International Architecture Biennale.

More about it HERE.

.jpg)