Thursday, October 04. 2012

Friday, June 15. 2012

-----

de noreply@blogger.com (Geoff Manaugh)

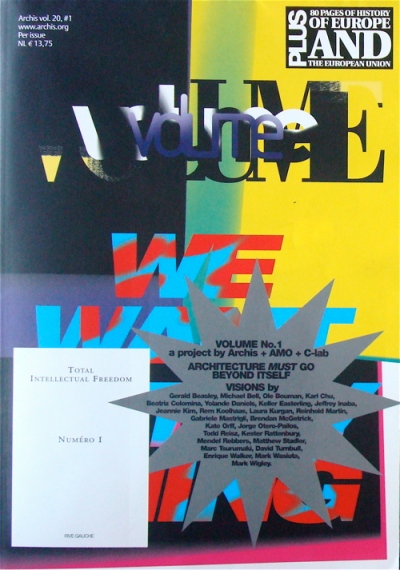

I'm excited to be launching a new project called Venue, a 16-month collaboration with the Nevada Museum of Art's Center for Art + Environment, Columbia University GSAPP's Studio-X NYC, and Future Plural, the small publishing and curatorial group I'm a part of with Nicola Twilley.

We kick things off this Friday, June 8, with a launch event at the Nevada Museum of Art in downtown Reno, from 6-8pm; if you're near Reno, consider stopping by!

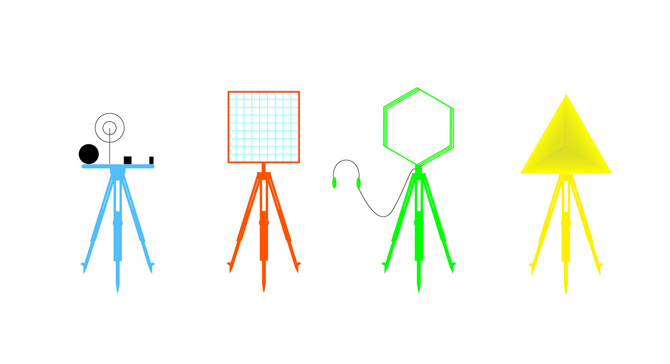

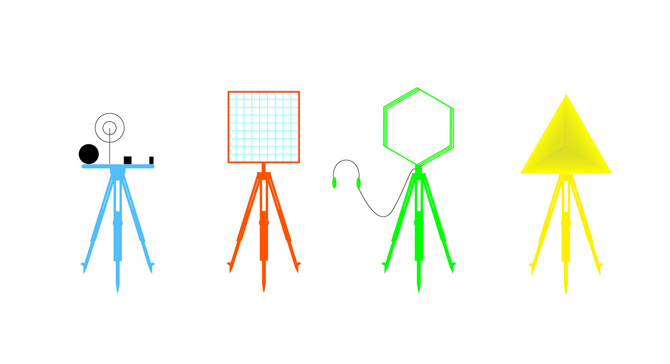

[Image: The tools and props of surveying; courtesy of the USGS]. [Image: The tools and props of surveying; courtesy of the USGS].

In brief, Venue is equal parts surveying expedition and forward-operating landscape research base, a DIY interview booth and media rig that will pop up at sites across North America through September 2013.

Nicola Twilley and I will be traveling on and off, in a series of discontinuous trips, over the next 16 months, visiting a variety of sites including infrastructural landmarks, science labs, factories, film sets, archaeological excavations, art installations, university departments, design firms, National Parks, urban farms, corporate offices, studios, town halls, and other locations across North America, where we'll both record and broadcast original interviews, tours, and site visits. From architects to scientists and novelists to mayors, from police officers to civil engineers and athletes to artists, Venue’s interview archive will form a cumulative, participatory, and media-rich core sample of the greater North American landscape.

[Image: Understanding landscapes by way of strange devices; courtesy of the USGS]. [Image: Understanding landscapes by way of strange devices; courtesy of the USGS].

While there will no doubt be regular updates here on BLDGBLOG, you can follow along, both online and off, by reading our latest dispatches, suggesting sites and people we should visit, and keeping an eye on our schedule (or signing up for our mailing list) to find out when we will be bringing Venue to a neighborhood near you. In addition, our best content will be syndicated on a dedicated channel online by The Atlantic, so keep your eye out for our first interviews or site visits—photos, short films, MP3s—as our travels get underway.

[Image: The Venue tripods, universal mounts for interchangeable devices; designed by Chris Woebken]. [Image: The Venue tripods, universal mounts for interchangeable devices; designed by Chris Woebken].

There's a lot more information available about the project at the Venue website—including some early images depicting the incredible array of devices designed for us by Chris Woebken, a gorgeous hand-made interview box custom-fabricated for Venue by Semigood, and the " Descriptive Camera" that we'll have on the first leg of our trip—so by all means stop by and see the ideas behind the project, from conceptual inspiration taken from historical survey expeditions to Ant Farm's Media Van.

[Image: The Venue box takes shape, custom-designed by Semigood]. [Image: The Venue box takes shape, custom-designed by Semigood].

And hopefully somewhere down the line, we can meet many of you in person.

Personal comment:

An interesting publishing project/initiative to follow and/or participate by Nicola Twilley and Geoff Manaugh.

Wednesday, June 13. 2012

Via Archinect

-----

de MAGAZINEONURBANISM

“If you go into the hardcore urban or the hardcore rural, it is quite simple to define it, but that is not so relevant. It is more significant to talk about the condition in between. And this condition is extremely difficult to define.” – Urban planner Kees Christiaanse in conversation with Bernd Upmeyer and Beatriz Ramo on behalf of MONU Magazine

MONU’s call for submissions for its latest issue (#16, Non Urbanism) asked its participants to “investigate how non-urbanism may be defined and identified today, and how non-urban areas interact with and relate to urban areas.“ Fortunately for readers, the printed compendium seems to succeed in largely refuting the very existence of its themed subject matter. Or, if it doesn’t go so far as to refute the ‘non urban’, the content demonstrates how difficult it is to call out any place as not being deeply under the influence of it.

MONU #16’s agenda fits within mounting reactions to the geographic myopia found in some of the contemporary ‘urban age’ rhetoric. ‘Non Urbanism’ explores what happens when the inventory of urban moves beyond widget counts of human bodies for its reductive definition. It asks: what is non-urbanism when we approach the ‘built environment’ in a fully relational way? What happens when we see cities in the wider geographic field of their effects, borrowin...

Tuesday, March 20. 2012

Via cityofsound

-----

de Dan Hill

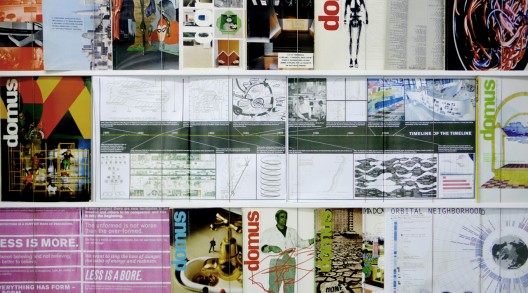

A quick word about a new series I’m curating for Domus, the Italian art, architecture and design magazine. Called SuperNormal, it’s an attempt to ‘sketch’ a different kind of technology journalism, recognised how cultural it is.

A few years ago, in response to the usual diminished depiction of contemporary technology as simply “IT”, someone—I forget who—said something like “Is a 14 year-old girl updating her Facebook status from her mobile phone as she walks down the street ‘IT’?” Of course it is, but more importantly, it isn’t. It is more than that; contemporary technology is deeply cultural. We might argue that all technology always has been “deeply cultural”, from the Stone Age axe onwards, but given that symbolic consumption and production—one definition of culture—is now actively and deliberately embedded in objects we design and build, and that these objects are embedded in the patterns, habits and rituals of everyday life—another definition of culture—we must now see technology for what it is.

So with Domus, Joseph Grima and I saw an opportunity to write in a different way about everyday technology. Domus has a long tradition of writing about such things, driven by the strong Italian heritage of post-war industrial design, covering Brionvega radios, Elica hoods, Vespa scooters, or Olivetti typewriters, for instance.

But as I suggest in my series opener (below), perhaps a culturally powerful contemporary equivalent of these things now exists in the form of social media, mobile phones, web services, information graphics, smart cards, personal informatics, robots, and so on.

It might be a stretch to suggest that these things are the equivalent of an Olivetti Valentine in a number of ways, but not in terms of the way such things now shape our lives. Yet the vast bulk of journalism concerning this everyday technology is dominated by the technology press, which is rarely critical in the sense that Domus is, rarely covers design aspects with any depth, and rarely attempts to place developments in a wider cultural context. While I have no problem with the likes of Engadget, Techcrunch, Wired and the rest—not that they’d notice either way if I did!—there did seem a gap in the market here.

Conversely, this was also a way to introduce discussion of the recent design disciplines of interaction design, experience design, service design and information design, to this more established strata of design media. For what it’s worth, my motive for doing this—discussing the technology in terms of culture, and discussing its design in the context of other design practices—is in order to try to understand it better; which is in turn in order to design it better, to realise it better, to procure it better, and so on.

(By the way, it’s a huge honour to work for Domus. There can have been few more influential titles in design history since its inception in 1928 and Joseph Grima, who I first worked with on Postopolis, has repositioned the magazine at the forefront of media once again, for me alongside Eye and Idea as the best design magazines out there. It’s also been a pleasure to work increasingly closely with the designers, Salottobuono, and particularly Marco Ferrari.)

The series will run in the magazine and online. We’re using the website to carry more in-depth versions of the print articles, and including video and other contextual information such as interviews where relevant.

I’ve written the first two articles to frame the series.

The first covered the Nokia N9 (and to some extent its successor, the Lumia running Windows Phone) but pitches that in the context of the wider skirmishes in the mobile phone market, tactility, sounds and ocularcentrism in cellphone design, the hegemonic power of Apple, the importance of materials and the “dark matter” of licensing and logistics, European design history and entrepreneurship, via Roland Barthes and the Citröen DS19.

The second piece concerns Facebook Timeline, and so timelines, information design, social graphs, identity and representation, and so on —but also the broader context of a shared social memory, and how that might affect the way we forget and function. (Additionally, Facebook were good enough to get us an interview with Timeline’s lead designer, Nicholas Felton—he of Feltron Annual Reports fame)—and his early mockups of Timeline, to accompany this article. Thanks to both Nicholas and Meredith Chin for that.)

These initial articles are markers, sketching out the trajectory and territory of the series to some extent. But as the series opener suggests below, the terrain should get increasingly rich, diverse and fertile and I’m lining up a set of great writers ready to explore it and map it. More on that to follow. I’ll pitch in from time to time too.

Have a read of the first two—‘Portable Cathedrals’ on the Nokia N9 and ‘In Praise of Lost Time’ on Facebook Timeline—and let me know what you think: here; at Domus; or elsewhere.

And here, below, is the original text for the series—which I’ve dubbed SuperNormal, in respectful homage to Jasper Morrison and Naoto Fukasawa’s great book and exhibition, noting its title Super Normal: Sensations of the Ordinary. This text introduces and frames the venture, and is a slightly different version to that which appears on the Domus website and in the magazine.

SuperNormal

The humble form of the mobile phone galvanises culture and design like few other products ever have.

Well beyond its original brief of connecting voices in real-time, and now dissolved in social media substrate, the mobile phone is essentially a tool for cultural production and consumption, for the everyday projection, dissembling or articulation of identity itself. As such, the cellphone represents an entirely new form of industrial design; it is intimate physically, psychologically and culturally, as well as framing the city and its activities. It can only be understood in the context of the few genuinely new design disciplines of the last two decades: the overlapping circles of interaction design, experience design, service design.

And for mobile phones, read Facebook Timeline’s interface design, the organising principles underpinning operating systems like OSX and Google Chrome OS, the platform service ecosystem of iTunes+iPhone, an RFID-based airport check-in system, the architecture of Angry Birds, what XBox Live says about community; what transport data apps say about contemporary urbanism; what the Microsoft Word interface says about our approach to tools; how the design strategy of the New York Times sketches the future of journalism, how Spotify follows in a lineage of music experiences from Brionvega to Technics …

When Domus started, there was no equivalent of these kind of devices, these kind of platforms, these kind of issues, although Domus has a long history of reviewing the products of everyday life, particularly through its coverage of industrial design. The publication absorbed these daily objects from its earliest days, particularly placing domestic products, furniture and office equipment on its pages. These are technology too of course. But now we must see beyond furniture to the glowing devices lying upon them. The iPhone, Facebook and Chrome are the descendants of Sottsass’s Olivetti Lettera, in a way. Perhaps Sottsass sensed this:

“My furniture is a trivial thing and doesn't matter at all. But the idea would be to invent new total possibilities, new forms, new symbols …” (Ettore Sottsass, Domus, 1965)

It turns out that these are the new objects, products and services of everyday life, the “new total possibilities”. They are ‘Super Normal’, though perhaps not in the sense that Jasper Morrison and Naoto Fukasawa intended in their exhibitions of 2006-2007. Our reading of the situation attempts to move beyond the traditional frames for assessing industrial design, and assesses designs that are intended to be usable, functional, meaningful, personal, productive, strategic, participative.

In the introduction to the accompanying Super Normal: Sensations of the Ordinary book, Gerrit Terstiege mentioned the 1976 Darmstadt exhibition ‘Das gewöhnliche Design’, and in particular the opening talk by Bazon Brock, professor of Aesthetics in Wuppertal:

“We must analyze and understand our contemporary world as if it were the everyday world of a historical society”. (Bazon Brock, 1976)

This would entail critically unpicking the social and cultural meaning of everyday products, not simply assessing their form, material or technical characteristics, but getting to their point; what each product says about our time and place.

So the cultural potency—the sheer relevance—of products like mobile phones, social media, and operating systems, has prompted Domus to start a new form of technology criticism, in a series that politely and respectfully hacks the name ‘Super Normal’.

Our idea is to offer an alternative to a discourse dominated by the likes of Engadget, Techcrunch, DPReview, Gizmodo et al. Sites like these cover products and services in unparalleled levels of technical detail and with respected in-depth knowledge. Yet they rarely discuss design in any meaningful way or the wider cultural impact of such things.

Domus won’t cover technical details, as they are ably covered by those sites, but it will assess what these products say about contemporary design. It won’t pore over unboxing videos, but it will try to unpack the wider issues that these products imply for contemporary culture. It won’t attempt to second-guess business strategy, but will describe how products and services are now linked as never before to the spheres of economics, logistics, environment and community.

So this is no buyer’s guide, but it may be a user guide of sorts, to the key products and services of the 21st century; the things that surround us, yet are currently not on the radar of design criticism. Stay tuned.

“Super Normal is already out there, out in the open; it exists in the here and now; it is real and available. We have only to open our eyes.” (Gerrit Terstiege, 2007)

SuperNormal: series opener [Domus]

Nokia N9: Portable Cathedrals [Domus]

Facebook Timeline: In Praise of Lost Time [Domus]

Interview with Facebook's Nicholas Felton [Domus]

Personal comment:

We met Dan Hill during Postopolis!LA back in 2009, then collaborated on a project together with Philippe Rahm. We will now read his "SuperNormal" articles in Domus (which is certainly the most interesting architecture magazine at the moment) with great interest.

Tuesday, January 10. 2012

Via Pruned

-----

In case you need reminding, Bracket 3 is looking for critical articles and unpublished design projects that explore “architecture, infrastructure and technology [operating] in conditions of imbalance, negotiate tipping points and test limit states. In such conditions, the status quo is no longer possible; systems must extend performance and accommodate unpredictability. As new protocols emerge, new opportunities present themselves. Bracket [at Extremes] seeks innovative contributions interrogating extreme processes (technologies, operations) and extreme contexts (cultural, climatic). What is the breaking point of architecture at extremes?”

The deadline is 20 February 2012.

Also be on the lookout for Bracket [goes soft], scheduled to be available this month from Actar. Some of the projects in this second almanac sound like they also belong in the new one.

Personal comment:

Thanks for the reminder!

Wednesday, November 16. 2011

Via ArchDaily

-----

de Alison Furuto

Courtesy of Columbia University

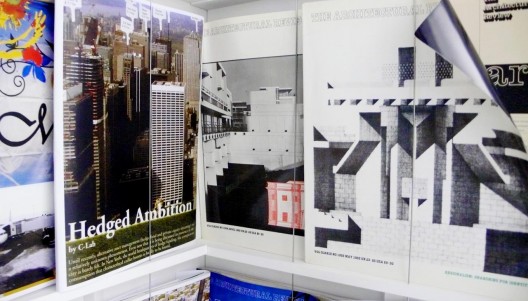

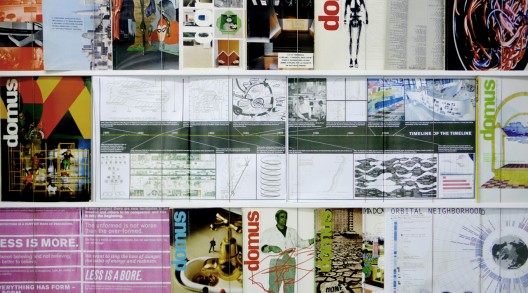

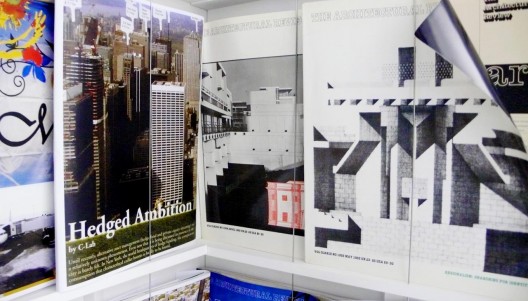

The work of C-Lab, Columbia University’s experimental urban and architecture think tank, is on display in Tokyo. Conceived as a temporary occupation, the exhibition presents C-Lab’s work alongside

magazines from Yoshioka Library’s archive of international architecture journals from the 1960s to today. Images of C-Lab analyses, planning projects, installations, and publications are positioned on the gallery’s shelves next to vintage issues of A+U, Japan Architect, Shinkenchiku, Space, Architectural Review, Domus, Abitare, and Casabella. More information on the exhibition after the break.

Courtesy of Columbia University

The exhibition is the first survey of C-Lab’s entire output and shows how the group gives form to content. With all the works, design is used to shape disparate facts into urban and architectural speculations, constructing information into findings about the patterns of urban development. Each project offers an urban proposition, the most overt being the master plans for Chengdu, China; Research Triangle Park, USA; and Saemangeum, South Korea. Also displayed are illustrated geographical and cultural case studies, and publications like the book World of Giving, issues of Volume Magazine, and C-Lab’s bootleg edition of Urban China. They too are designed to clarify urban conditions and outline planning strategies. As such, the diagrams, texts, and publications are forms that like the master plans activate an understanding of spatial relationships, and can be thought of as a kind of architecture.

Courtesy of Columbia University

Accompanying the exhibition is a tabloid-format publication that highlights four reappearing themes in the lab’s studies. The first involves processing mounds of cultural data to identify unexpected patterns of urbanization. With each project urban occurrences are harnessed into a visual matrix to convey a hypothesis about the operations of cities. Its supporting text articulates unforeseen consequences affecting urban design and policy.

Courtesy of Columbia University

The second describes the bonding of unrelated typologies into new, practical sensibilities for development. Conceptual readymades are mashed up into urban morphologies that re-imagine city environments. The familiar shape of the readymades lends an immediate legibility to the plans and affords an economy of means for transmitting their emergent character.

Courtesy of Columbia University

The third focuses on the communication of architectural ideas. Each one of the included illustrations is a unique design that telegraphs a C-Lab insight on urbanism. The drawings, modified photographs, analytical diagrams, curated data comparisons, and animations all function as communication instruments that express concepts about the city through a visual means rather than a text explanation. Typically appearing at the start of a publication, they are a condensation of the narrative that foretells the story about to unfold in words. At the same time, each graphic figure is a construction in its own right. The designs are presented here without their accompanying text to feature the logic that went into their making. Collectively, they represent the dimension of media used by C-Lab to leak information into the architectural subconscious.

Courtesy of Columbia University

The last method addresses the power of scale. Since architectural thinking can be applied to contexts of various size (furniture, exhibition, building, district, city, and media landscape), it is valuable to know the power of operating at each one. Sometimes, to achieve an intended result it may be more effective to work at a different scale than the one initially assumed or requested, or to work at multiple scales and leverage the effects of the forms across them. C-Lab believes that for the architect to be productive in the most beneficent sense requires understanding the power that lies in exercising architectural thinking at all registers of experience.

Courtesy of Columbia University

In this spirit, the publication itself functions at several scales of experience. It can be read in a standard tabloid format where projects of each category occupy a spread. Half pages can also be joined to make a single large image of one representative project from each category. And multiple copies of the publication can be assembled to create even bigger text and image compositions, such as the one arranged at the center of the exhibition that spells out, “C L A B.”

Thursday, May 19. 2011

by Christopher Henry

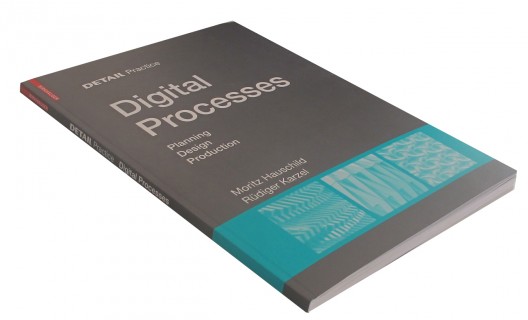

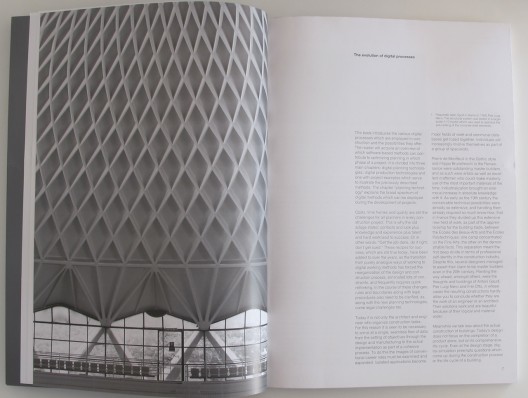

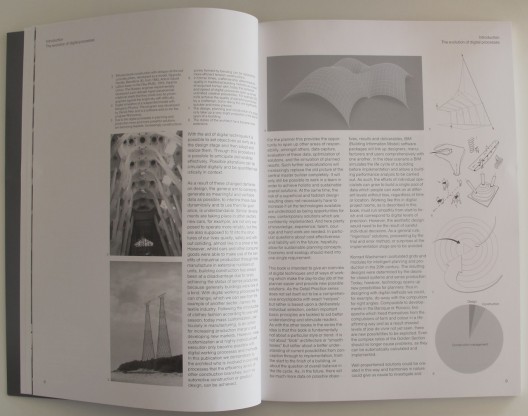

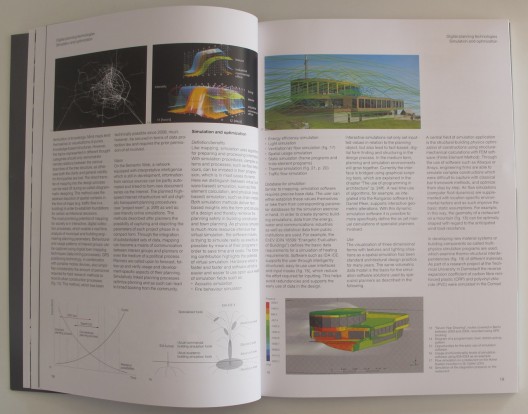

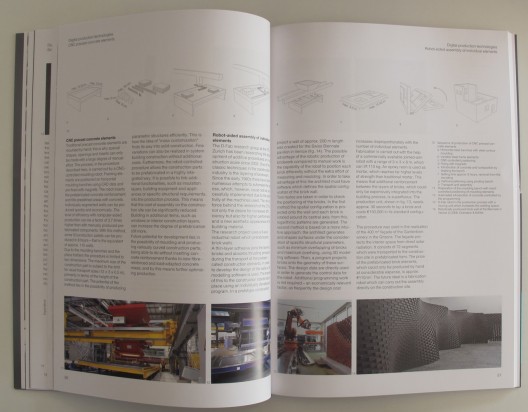

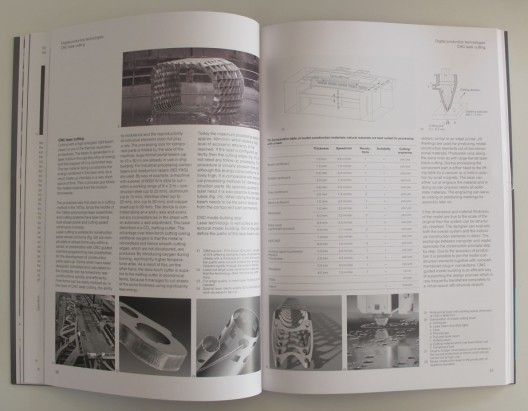

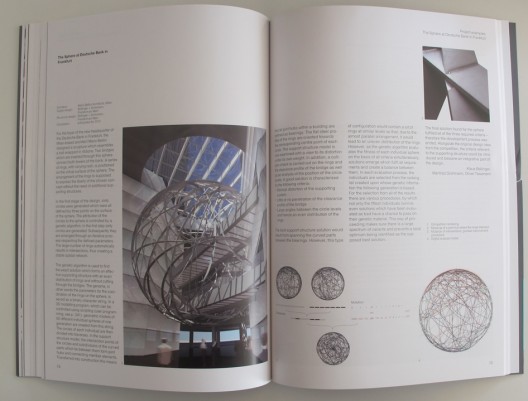

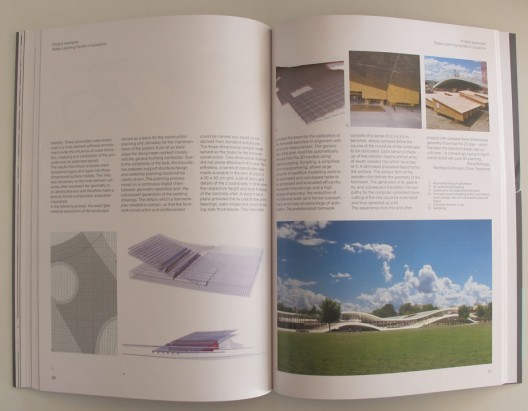

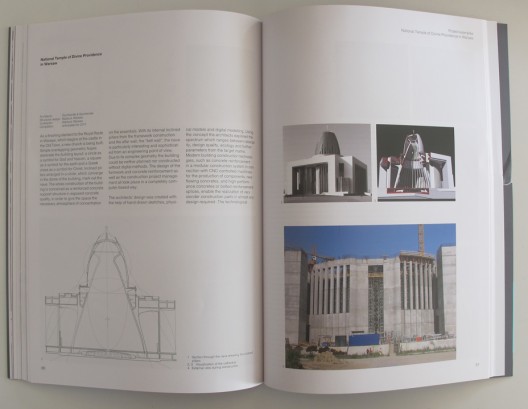

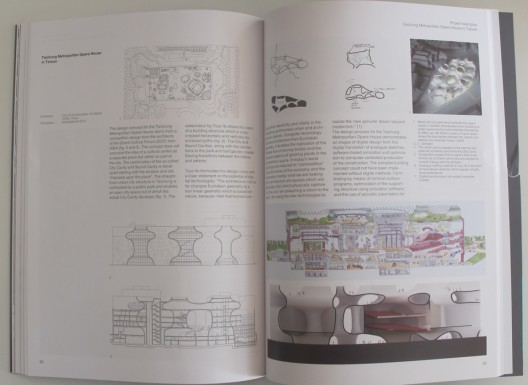

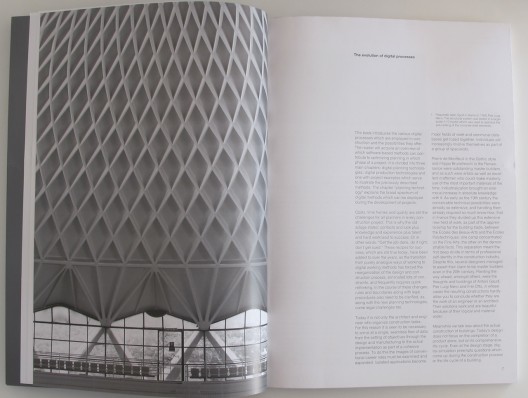

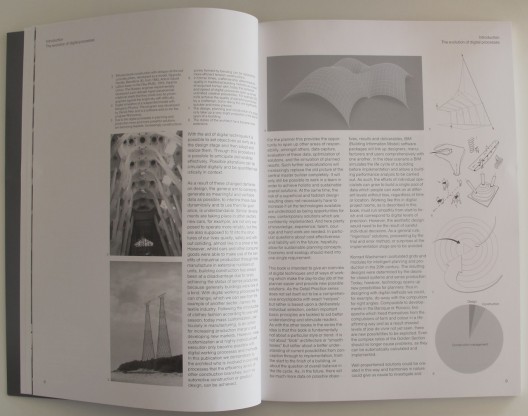

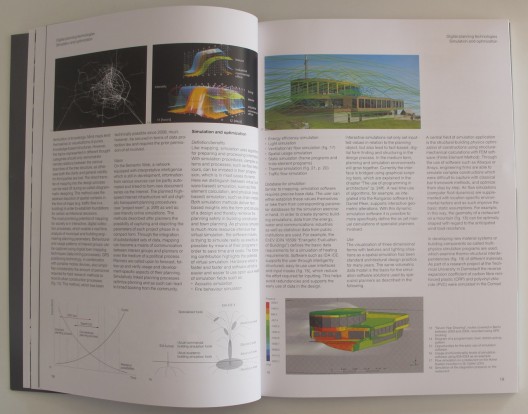

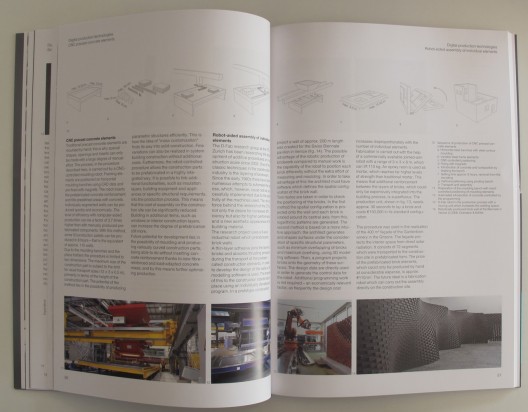

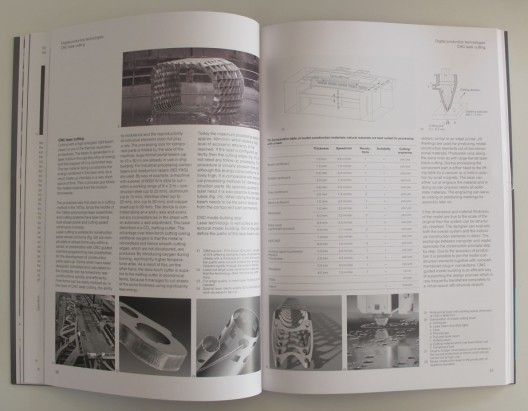

I recently read Detail Magazine’s latest issue about Digital Processes. The issue is divided into three parts. The first part deals with digital planning technologies that include mapping techniques for analysis, terrestrial laser scanning, and geographic information systems among others. The second section delves into digital production technologies such as CNC laser cutting, hot wire cutting, and jointed-arm robotics. The final piece brings these together by showcasing six projects that utilize these technologies. In its totality, the issue is a good overall look at the present and future opportunities digital technology offers the profession.

Contents

7 Introduction: The Evolution of Digital Processes

Digital Planning Technologies

14 Geographic Information Systems

16 Analysis Techniques—Mapping

18 Simulation and Optimization

21 Computer-aided Architectural Design (CAAD)

24 Rule-Based Planning—Parametrics

27 Digital Capture—Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS)

29 Project Room—The Transparent Project

33 Digital Interfaces in Construction

41 Legal Challenges in the Context of Digital Planning Processes

Digital Production Technologies

46 Generative Procedures

46 Rapid Procedures

50 CNC Precast Concrete Elements

50 Robot-aided Assembly of Individuals Elements

52 3D Printing on a Large Scale

54 Subtractive Procedures

56 CNC Laser Cutting

58 CNC Jet Cutting

59 CNC Hot Wire Cutting

60 CNC Milling

61 Jointed-arm Robotics

62 Forming Processes

64 CNC Bending Edges

66 CNC Punching and Nibbling

68 Pressure Forming

Project Examples

72 Digital Generation of a Supporting Structure

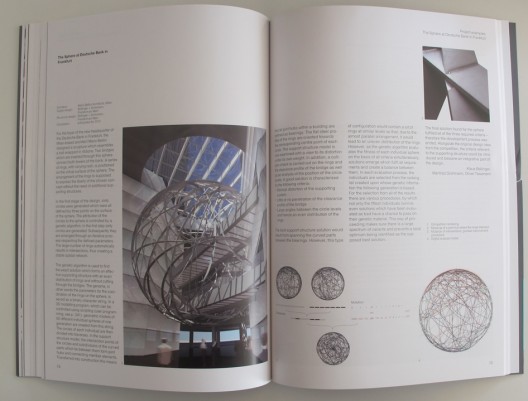

74 The Sphere at Deutshe Bank in Frankfurt

76 Pedestrian Bridge in Reden

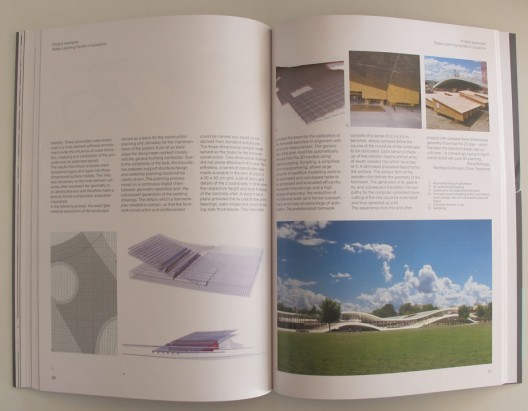

77 Rolex Learning Center in Lausanne

82 Hungerburg Funicular in Innsbruck

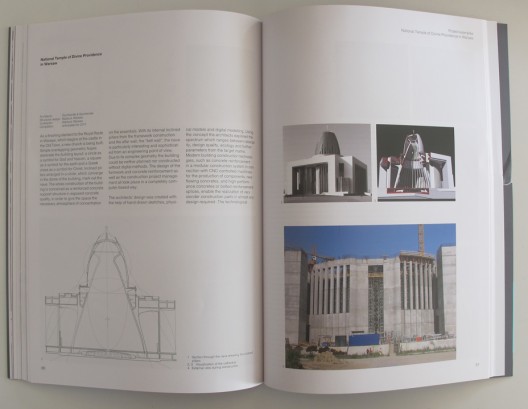

86 National Temple of Divine Providence in Warsaw

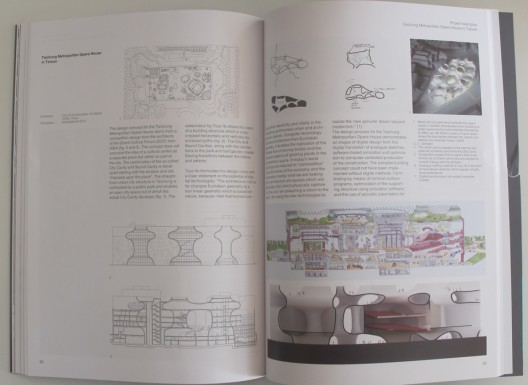

92 Taichung Metropolitan Opera House in Taiwan

Appendix

105 Glossary

107 Literature: Reference Books and Articles

108 Manufacturers, Companies and Academic Institutions

109 Picture Credits

110 Index

Authors:

Moritz Hauschild

Rüdiger Karzel

Co-Authors:

Martin Berchtold

Klaus Bollinger

Manfred Grohmann

Holger Heilmann

Philipp Krass

Arne Künstler

Martin Manegold

Heike Matcha

Shozo Motosugi

Christoph Motzko

Oliver Tessmann

Axel Wirth

Staff:

Ante Ljubas

Sara Darvish

Christoph Kühne

Editorial Services:

Cornelia Hellstern, Nicola Kollmann, Eva Schönbrunner

Editorial Assistants:

Katinka Johanning, Peter Popp, Verena Schmidt

Cover: Paperback

Pages: 111

ISBN: 978-3-0346-0725-4

Tuesday, April 26. 2011

Via @chrstphggnrd

-----

An exhibition at the MOMA about the Whole Earth Catalog of Stewart Brand:

Whole Earth Catalog, spring 1969

In 1968, Stewart Brand founded the Whole Earth Catalog. Brand’s goals were to make a variety of tools accessible to newly dispersed counterculture communities, back-to-the-land households, and innovators in the fields of technology, design, and architecture, and to create a community meeting-place in print. The catalogue quickly developed into a wide-ranging reference for new living spaces, sustainable design, and experimental media and community practices. After only a few years of publication it exploded in popularity, becoming a formidable cultural phenomenon.

(...)

More about it HERE.

Thursday, March 03. 2011

Via Shrapnel Contemporary

-----

by pedrogadanho

While in Montreal, I had the opportunity to browse through some of the classics that made the notion of the “little magazine” so dear to us all. And so, from the exquisite CCA library I picked a few challenging inaugural issues on which to expand in this unending section of Shrapnel C. (Soundtrack here.)

Utopie, subtitled Sociologie de l’urbain, is probably most referential nowadays because in its editorial board was a bright sociological mind – one who became a reference for architects and other cultural producers: Jean Baudrillard.

As today one flips through this little French revue’s número un – brought out in May 1967 – one again realizes how some important architecture futures first crystallize in settings that are distant from architecture’s specialized media. Indeed, it is sometimes in other media that the first attempts to synthesize a particular moment in architecture comes about.

As such, along the “critical thinking” on urbanism, or timely notes on “marxisme et esthétique” and the consumption of objects, it is also in this outsider’s publication that one suddenly discovers early discussions on the ephemeral in architecture – with topics ranging from the boutiques and the emergency habitats to Cedric Price or Archigram. How more up-to-date can you be?

And while Utopies dwelled on the imagination of the villes de papier – with unexpectedly early insights of the role of graphic novels in the visualization of urban futures – on the other side of the channel or the ocean, architects themselves were still clipping photocopies in the fashion of Corbusier, or desperately clinging to classicize modernism in the fashion of Mies.

About the same time as Utopie was coming out in revolutionary Paris, in swinging London the conceptual grandfather of Clip, Stamp, Fold and other contemporary adventures, a small black-and-white assemblage of photocopies by the name of clip-kit again got together Cedric Price, Mike Webb, and Reyner Banham, with all of them trying to pin down their references outside architecture – from cars and industrial caravans to gas tanks and the machine logic.

While trying to legitimize new languages in the realm of popular production, and even if self-proclaiming their own revolutionary promise or the concern “with progressive architectural ideas,” architects somehow seemed unaware of the true impact of their images and concepts in other cultural realms of their time.

On the other hand, half a dozen years later in New York, such “progressive” images were being subsumed to the archive by an enduring intellectual attempt to institutionalize modernism as the true and only rule of the architectural field.

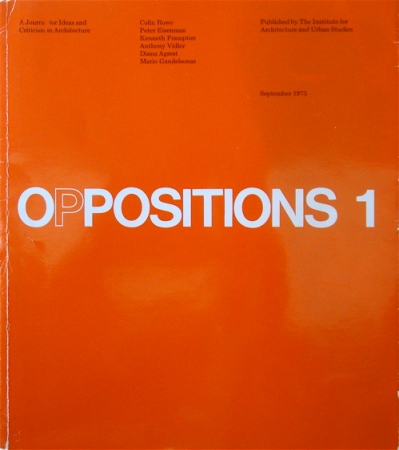

Oppositions 1, brought out in September 1973 as a “Journal for Ideas and Criticism in Architecture” by the guiding hands of Peter Eisenman, Keneth Frampton and Mario Gandelsonas, was to dictate where the tectonic avant-garde really lied – from Colin Rowe’s reading of neoclassicism in Modern Architecture, down to Anthony Vidler’s analysis of utopia or Diana Agrest and Mario Gandelsonas’ “Semiotics and Architecture: Ideological Consumption or Theoretical Work”.

From then on, one could succinctly and polemically say that it took three decades for architectural media to again try and go “beyond architecture” – and its self-referential academic theories –as it happened with my last pick from the CCA’s collection: Volume #01, out in 2005 as a radical transformation of previous Archis magazine lead by Ole Bouman.

In this instance, blending AMO, the C-Lab and mysterious graphic insertions such as the Rive Gauche’s “Total Intellectual Freedom”, Volume was again to reset the coordinates of where the post-critical avant-garde should be – by fiercely committing to strong statements, visual liveliness and the notion of architecture as an expanded cultural field.

As Ole Bouman optimistically stated at this instance, architecture was again “a universal access code”, “a powerful kind of strategic intelligence”, “a medium for developing cultural concepts.” And yet, Beatriz Colomina funnily added elsewhere in the mag that as “our dentists suddenly think that architecture is important,” maybe it was about time “we should embrace its irrelevance.”

As architecture was strongly mediatized through other cultural media – from Time magazine to Wallpaper, you name it – so its theory and its specialized media had to move into the realm of communication, to again ground architecture’s relationship to a fast-moving society.

And in this respect – as in the respect of the stuff that makes magazines historically relevant – it is pretty amazing for me to realize as half a dozen years ago, in Volume’s pages one could already discern some of the questions that we are still currently enjoying to debate – from “unsolicited architecture” to “fiction,” and from “experimental writing” to all of today’s cherished “beyonds.”

|

[Image: The tools and props of surveying; courtesy of the

[Image: The tools and props of surveying; courtesy of the  [Image: Understanding landscapes by way of strange devices; courtesy of the

[Image: Understanding landscapes by way of strange devices; courtesy of the  [Image: The Venue tripods, universal mounts for interchangeable devices; designed by Chris Woebken].

[Image: The Venue tripods, universal mounts for interchangeable devices; designed by Chris Woebken]. [Image: The Venue box takes shape, custom-designed by

[Image: The Venue box takes shape, custom-designed by