Via Shrapnel Contemporary

-----

by pedrogadanho

While in Montreal, I had the opportunity to browse through some of the classics that made the notion of the “little magazine” so dear to us all. And so, from the exquisite CCA library I picked a few challenging inaugural issues on which to expand in this unending section of Shrapnel C. (Soundtrack here.)

Utopie, subtitled Sociologie de l’urbain, is probably most referential nowadays because in its editorial board was a bright sociological mind – one who became a reference for architects and other cultural producers: Jean Baudrillard.

As today one flips through this little French revue’s número un – brought out in May 1967 – one again realizes how some important architecture futures first crystallize in settings that are distant from architecture’s specialized media. Indeed, it is sometimes in other media that the first attempts to synthesize a particular moment in architecture comes about.

As such, along the “critical thinking” on urbanism, or timely notes on “marxisme et esthétique” and the consumption of objects, it is also in this outsider’s publication that one suddenly discovers early discussions on the ephemeral in architecture – with topics ranging from the boutiques and the emergency habitats to Cedric Price or Archigram. How more up-to-date can you be?

And while Utopies dwelled on the imagination of the villes de papier – with unexpectedly early insights of the role of graphic novels in the visualization of urban futures – on the other side of the channel or the ocean, architects themselves were still clipping photocopies in the fashion of Corbusier, or desperately clinging to classicize modernism in the fashion of Mies.

About the same time as Utopie was coming out in revolutionary Paris, in swinging London the conceptual grandfather of Clip, Stamp, Fold and other contemporary adventures, a small black-and-white assemblage of photocopies by the name of clip-kit again got together Cedric Price, Mike Webb, and Reyner Banham, with all of them trying to pin down their references outside architecture – from cars and industrial caravans to gas tanks and the machine logic.

While trying to legitimize new languages in the realm of popular production, and even if self-proclaiming their own revolutionary promise or the concern “with progressive architectural ideas,” architects somehow seemed unaware of the true impact of their images and concepts in other cultural realms of their time.

On the other hand, half a dozen years later in New York, such “progressive” images were being subsumed to the archive by an enduring intellectual attempt to institutionalize modernism as the true and only rule of the architectural field.

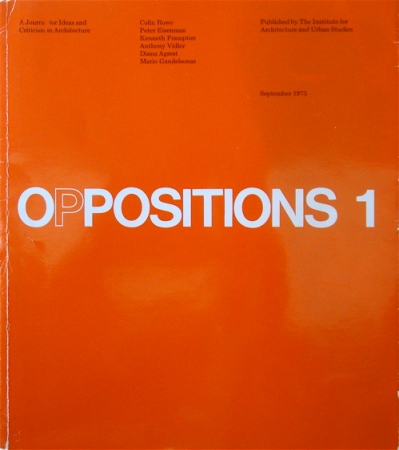

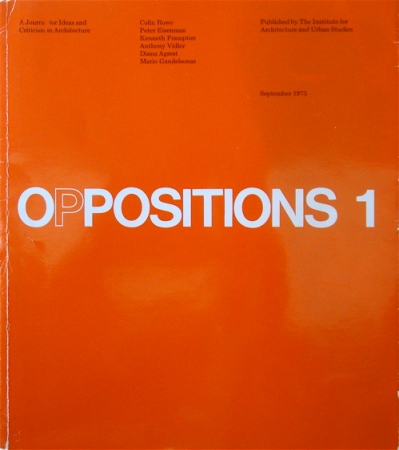

Oppositions 1, brought out in September 1973 as a “Journal for Ideas and Criticism in Architecture” by the guiding hands of Peter Eisenman, Keneth Frampton and Mario Gandelsonas, was to dictate where the tectonic avant-garde really lied – from Colin Rowe’s reading of neoclassicism in Modern Architecture, down to Anthony Vidler’s analysis of utopia or Diana Agrest and Mario Gandelsonas’ “Semiotics and Architecture: Ideological Consumption or Theoretical Work”.

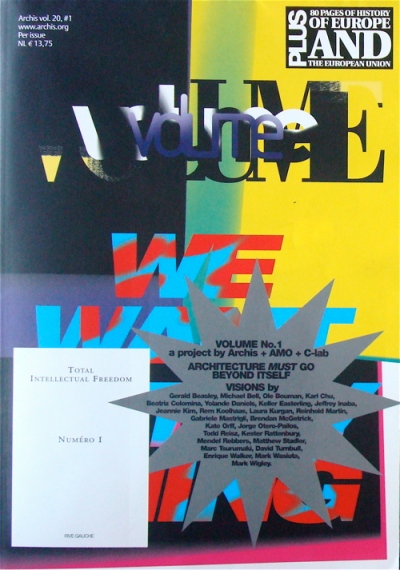

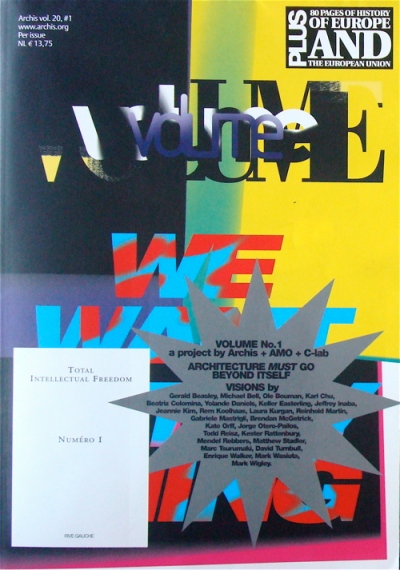

From then on, one could succinctly and polemically say that it took three decades for architectural media to again try and go “beyond architecture” – and its self-referential academic theories –as it happened with my last pick from the CCA’s collection: Volume #01, out in 2005 as a radical transformation of previous Archis magazine lead by Ole Bouman.

In this instance, blending AMO, the C-Lab and mysterious graphic insertions such as the Rive Gauche’s “Total Intellectual Freedom”, Volume was again to reset the coordinates of where the post-critical avant-garde should be – by fiercely committing to strong statements, visual liveliness and the notion of architecture as an expanded cultural field.

As Ole Bouman optimistically stated at this instance, architecture was again “a universal access code”, “a powerful kind of strategic intelligence”, “a medium for developing cultural concepts.” And yet, Beatriz Colomina funnily added elsewhere in the mag that as “our dentists suddenly think that architecture is important,” maybe it was about time “we should embrace its irrelevance.”

As architecture was strongly mediatized through other cultural media – from Time magazine to Wallpaper, you name it – so its theory and its specialized media had to move into the realm of communication, to again ground architecture’s relationship to a fast-moving society.

And in this respect – as in the respect of the stuff that makes magazines historically relevant – it is pretty amazing for me to realize as half a dozen years ago, in Volume’s pages one could already discern some of the questions that we are still currently enjoying to debate – from “unsolicited architecture” to “fiction,” and from “experimental writing” to all of today’s cherished “beyonds.”