Tuesday, April 18. 2017

Ghost in the Shell movie city design, Ash Thorp | #movie #3d #fiction #architecture

Note: following the post about the conference at Bartlett about game design and architecture, I also post this link (show reel) regarding the recent set & prop design for the movie Ghost in the Shell.

We can certainly discuss the quality of the movie indeed, or rather its necessity compared to the original japan anime (a funny remark about it though: if you have the questionable chance to be "reborned" or "ghosted" like the major in the remade movie, you'll transform from asian to caucasian white ... Which is the same fate as the movie in fact, if you have the chance to be "redone", you'll go from japan anime to Hollywood pimped movie...), but we can all agree about the quality of the environment and character design nonetheless. Even if conceptually, this future looks a lot like an "hyper-present" (more networks, more media, more digital, more robots, cyborgs and viruses, more hackers, etc. - that will not happen therefore).

In particular for architects, the urban design of the "Hong Kong++" (or "Blade Runner++" ) style city, full of skyscrapers sized holograms, mostly publicities. A design in a kind of strange and brutal mish-mash with more regular yet buildings. This is the quite 3d graphical work ofAsh Thorp that i link below.

Considering these different exemples, we could wonder why architectural schools don't take more into consideration these kind of works? So as the ones present in literature. Couldn't we start thinking that architecture is a field that indeed and of course, build physical spaces and cities, but not only.

So, it should also take its part in the conceptualization and design of "networked", "virtual" or rather "mixed realities" (whatever further necessary debates we could have about the understanding of those words), environments for games and movies? Possibly also by extension non material spaces in general? And of course, all the probably more interesting "in betweens"? I truly believe architectural discourse could easily consider all these aspects of architecture and widen a bit its educational scope.

But I don't see this coming so much. Do you? (there are some discussion forums on Archinect for example)

Via Kotaku

-----

Some additionnal information about the conceptual work on the movie.

Another interesting and quite "space-graphical" short anime by Ash Thorp, "Epoch" - in a slightly "2001" style-, can be accessed on his site as well. And interestingly for 3d designers, he has created with fellow industry-artists a teaching platform led by professionals: Learn Squared (they are hosting a talk about the set design on Twitch next Wednesday btw). There can you learn "UI and Data Design for Film", "3D Concept Design", "Motion Design", etc.

More works about the movie HERE (in a post by Luke Plunkett).

Related Links:

Monday, February 20. 2017

The Ulm Model: a school and its pursuit of a critical design practice | #design #teaching

Via It's Nice That

-----

Words by Billie Muraben, photography by Connor Campbell

“My feeling is that the Bauhaus being conveniently located before the Second World War makes it safely historical,” says Dr. Peter Kapos. “Its objects have an antique character that is about as threatening as Arts and Crafts, whereas the problem with the Ulm School is that it’s too relevant. The questions raised about industrial design [still apply], and its project failed – its social project being particularly disappointing – which leaves awkward questions about where we are in the present.”

Kapos discovered the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm, or Ulm School, through his research into the German manufacturing company Braun, the representation of which is a specialism of his archive, das programm. The industrial design school had developed out of a community college founded by educationalist Inge Scholl and graphic designer Otl Aicher in 1946. It was established, as Kapos writes in the book accompanying the Raven Row exhibition, The Ulm Model, “with the express purpose of curbing what nationalistic and militaristic tendencies still remained [in post-war Germany], and making a progressive contribution to the reconstruction of German social life.”

The Ulm School closed in 1968, having undergone various forms of pedagogy and leadership, crises in structure and personality. Nor the faculty or student-body found resolution to the problems inherent to industrial design’s claim to social legitimacy – “how the designer could be thoroughly integrated within the production process at an operational level and at the same time adopt a critically reflective position on the social process of production.” But while the Ulm School and the Ulm Model collapsed, it remains an important resource, “it’s useful, even if the project can’t be restarted, because it was never going to succeed, the attempt is something worth recovering. Particularly today, under very difficult conditions.”

Foundation Course exercise

Student: Hans von Klier

Instructor: Helene Nonné-Schmidt 1955

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise

Student: Bertus Mulder

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise

Student: M. Buch

Instructor: Tomás Maldonado

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Max Bill, a graduate of the Bauhaus and then president of the Swiss Werkbund, arrived at Ulm in 1950, having been recruited partly in the hope that his international profile would attract badly needed funding. He tightened the previously broad curriculum, established by Marxist writer Hans Werner Richter, around design, mirroring the practices of his alma mater.

Bill’s rectorship ran from 1955-58, during which “there was no tension between the way he designed and the requirements of the market”. The principle of the designer as artist, a popular notion of the Bauhaus, curbed the “alienating nature of industrial production”. Due perhaps in part to the trauma of WW2, people hadn’t been ready to allow technology into the home that declared itself as technology.

“The result of that was record players and radios smuggled into the home, hidden in what looked like other pieces of furniture, with walnut veneers and golden tassels.” Bill’s way of thinking didn’t necessarily reflect the aesthetic, but it wasn’t at all challenging politically. “So in some ways that’s really straight-forward and unproblematic – and he’s a fantastic designer, an extraordinary architect, an amazing graphic designer, and a great artist – but he wasn’t radical enough. What he was trying to do with industrial design wasn’t taking up the challenge.”

Foundation Course exercise

Student: John Lottes

Instructor: Anthony Frøshaug

1958-59

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

In 1958 Bill stepped down having failed to “grasp the reality of industrial production simply at a technical and operational level… [or] recognise its emancipatory potential.” The industrial process had grown in complexity, and the prospect of rebuilding socially was too vast for single individuals to manage. It was no longer possible for the artist-designer to sit outside of the production process, because the new requirements were so complex. “You had to be absolutely within the process, and there had to be a team of disciplinary specialists — not only of material, but circulation and consumption, which was also partly sociological. It was a different way of thinking about form and its relation to product.”

After Bill’s departure, Tomás Maldonado, an instructor at the school, “set out the implications for a design education adequate to the realities of professional practice.” Changes were made to the curriculum that reflected a critically reflective design practice, which he referred to as ‘scientific operationalism’ and subjects such as ‘the instruction of colour’, were dropped. Between 1960-62, the Ulm Model was introduced: “a novel form of design pedagogy that combined formal, theoretical and practical instruction with work in so-called ‘Development Groups’ for industrial clients under the direction of lecturers.” And it was during this period that the issue of industrial design’s problematic relationship to industry came to a head.

“You had to be absolutely within the process, and there had to be a team of disciplinary specialists – not only of material, but circulation and consumption, which was also partly sociological. It was a different way of thinking about form and its relation to product.”

– Peter Kapos

In 1959, a year prior to the Ulm Model’s formal introduction, Herbert Lindinger, a student from a Development Group working with Braun, designed an audio system. A set of transistor equipment, it made no apologies for its technology, and looked like a piece of engineering. His audio system became the model for Braun’s 1960s audio programme, “but Lindinger didn’t receive any credit for it, and Braun’s most successful designs from the period derived from an implementation of his project. It’s sad for him but it’s also sad for Ulm design because this had been a collective project.”

The history of the Braun audio programme was written as being defined by Dieter Rams, “a single individual — he’s an important designer, and a very good manager of people, he kept the language consistent — but Braun design of the 60s is not a manifestation of his genius, or his vision.” And the project became an indication of why the Ulm project would ultimately fail, “when recalling it, you end up with a singular genius expressing the marvel of their mind, rather than something that was actually a collective project to achieve something social.”

An advantage of Bill’s teaching model had been the space outside of the industrial process, “which is the space that offers the possibility of criticality. Not that he exercised it. But by relinquishing that space, [the Ulm School] ended up so integrated in the process that they couldn’t criticise it.” They realised the contradiction between Ulm design and consumer capitalism, which had been developing along the same timeline. “Those at the school became dissatisfied with the idea of design furnishing market positions, constantly producing cycles of consumptive acts, and they struggled to resolve it.”

The school’s project had been to make the world rational and complete, industrially-based and free. “Instead they were producing something prison-like, individuals were becoming increasingly separate from each other and unable to see over their horizon.” In the Ulm Journal, the school’s sporadic, tactically published magazine that covered happenings at, and the evolving thinking and pedagogical approach of Ulm, Marxist thinking had become an increasingly important reference. “It was key to their understanding the context they were acting in, and if that thinking had been developed it would have led to an interesting and different kind of design, which they never got round to filling in. But they created a space for it.”

Foundation Course exercise

Student: Hans von Klier

Instructor: Tomás Maldonado

1956

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise (detail)

Student: Hans von Klier

Instructor: Tomás Maldonado

1956

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

“[A Marxian approach] would inevitably lead you out of design in some way. And the Ulm Model, the title of the Raven Row exhibition, is slightly ironic because it isn’t really a model for anything, and I think they understood that towards the end. They started to consider critical design as something that had to not resemble design in its recognised form. It would be nominally designed, the categories by which it was generally intelligible would need to be dismantled.”

The school’s funding was equally problematic, while their independence from the state facilitated their ability to validate their social purpose, the private foundation that provided their income was funded by industry commissions and indirect government funding from the regional legislator. “Although they were only partially dependent on government money, they accrued so much debt that in the end they were entirely dependent on it. The school was becoming increasingly radical politically, and the more radical it became, the more its own relation to capitalism became problematic. Their industry commissions tied them to the market, the Ulm Model didn’t work out, and their numbers didn’t add up.”

The Ulm School closed in 1968, when state funding was entirely withdrawn, and its functionalist ideals were in crisis. Abraham Moles, an instructor at the school, had previously asserted the inconsistency arising from the practice of functionalism under the conditions of ‘the affluent society’, “which for the sake of ever expanding production requires that needs remain unsatisfied.” And although he had encouraged the school to anticipate and respond to the problem, so as to be the “subject instead of the object of a crisis”; he hadn’t offered concrete ideas on how that might be achieved.

But correcting the course of capitalist infrastructure isn’t something the Ulm School could have been expected to achieve, “and although the project was ill-construed, it is productive as a resource for thinking about what a critical design practice could be in relation to capitalism.” What’s interesting about the Ulm Model today is their consideration of the purpose of education, and their questioning of whether it should merely reflect the current state of things – “preparing a workforce for essentially increasing the GDP; and establishing the efficiency of contributing sectors in a kind of diabolical utilitarianism.”

Ulm Journal of the Hochschule für Gestaltung

Foundation Course exercise (detail)

Student: Bertus Mulder

1956-57

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise

Student: Hans von Klier

Instructor: Tomás Maldonado

1956

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise (detail)

Student: Bertus Mulder

Date unknown

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise

Student: Hans von Klier

Instructor: Tomás Maldonado

1956

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Foundation Course exercise (detail)

Student: Hans von Klier

Instructor: Helene Nonné-Schmidt

Date unknown

Courtesy HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Related Links:

Tuesday, November 01. 2016

Get lost in Philippe Jarrigeon’s photographs of mazes | #odd

Note: posted a few weeks ago on It's Nice That, those pictures by photographer Philippe Jarrigeon about mazes.

Where this out of date esthetic seems nowadays quite odd, with some "Marienbad" flavour in them, with colour and combined ... of ... course ... with some "Shining"!

Via It's Nice That

-----

More about it HERE.

Related Links:

Tuesday, September 13. 2016

Illusions ... | #andscience

Note: what about starting again after the Summer #farniente with some "illusions and science"? "Amazing" that's for sure.

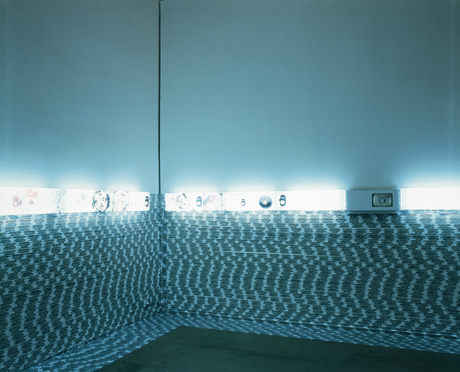

Would have certainly been a useful resource for the research workshop we led around "the cloud" with Random International, about ghost data presence (and to develop Ghost Data Interfaces). Especially as I pointed out the "sublime" dimension of technology in a related post.

-----

Via brusspup (channel on Youtube)

...

with some gyroscopes:

(remember that btw?)

...

or with some magnets:

...

or even with some hammer!

...

and many more tricks on Brussup channel, mainly in its "Cool science Tricks" playlist.

Monday, July 18. 2016

In the future, there will be no such thing as a "straight photograph" | #photography #data

Note: published a little while ago, this article from Time magazine ("The Next Revolution in Photography Is Coming") makes a fascinating point about the changing nature of photography. Even so the article mostly talks about journalism photography.

An interesting analysis by Stephen Mayes that shows how far photography is becoming data capture (sensing)... as much --or even more-- as it is visual capture. We should certainly discuss further around this question with the scientists that are writing the algorithms of photography. Yet as stated in the paper, a camera is slowly becoming primarily a "data-collecting device" and the image reconstructed from these data (by algorithms then) a last "grip on the belief in the image as an objective record".

This comes in resonance with our scholar understanding of photography as the media that was once believed or phantasized of being able to "capture reality", as it is. The early cinema carried later the same kind of beliefs. And we could then think again about this fantastic novel by Adolfo Bioy Casares (The Invention of Morel, 1940) that was extrapolating around these myths (of being able to fully record and register the "present", then replay it, entirely).

Today, this belief in our ability to "fully record the real" or digg into its recorded past (some big data projects) has a tendency to be transferred into data capture (and I obviously publish this post on purpose just after the presentation of an architecture project by fabric | ch that largely used and played around this idea of recording the present and that followed an installation around the same idea, through data).

So the connection that is made in this paper between photography and data capture is full of epistemological interests!

Via Time

-----

In the future, there will be no such thing as a "straight photograph"

It’s time to stop talking about photography. It’s not that photography is dead as many have claimed, but it’s gone.

Just as there’s a time to stop talking about girls and boys and to talk instead about women and men so it is with photography; something has changed so radically that we need to talk about it differently, think of it differently and use it differently. Failure to recognize the huge changes underway is to risk isolating ourselves in an historical backwater of communication, using an interesting but quaint visual language removed from the cultural mainstream.

The moment of photography’s “puberty” was around the time when the technology moved from analog to digital although it wasn’t until the arrival of the Internet-enabled smartphone that we really noticed a different behavior. That’s when adolescence truly set in. It was surprising but it all seemed somewhat natural and although we experienced a few tantrums along the way with arguments about promiscuity, manipulation and some inexplicable new behaviors, the photographic community largely accommodated the changes with some adjustments in workflow.

But these visible changes were merely the advance indicators of deeper transformations and it was only a matter of time before people’s imagination reached beyond the constraints of two dimensions to explore previously unimagined possibilities. And so it is that we find ourselves in a world where the digital image is almost infinitely flexible, a vessel for immeasurable volumes of information, operating in multiple dimensions and integrated into apps and technologies with purposes yet to be imagined.

Digital capture quietly but definitively severed the optical connection with reality, that physical relationship between the object photographed and the image that differentiated lens-made imagery and defined our understanding of photography for 160 years. The digital sensor replaced to optical record of light with a computational process that substitutes a calculated reconstruction using only one third of the available photons. That’s right, two thirds of the digital image is interpolated by the processor in the conversion from RAW to JPG or TIF. It’s reality but not as we know it.

For obvious commercial reasons camera manufacturers are careful to reconstruct the digital image in a form that mimics the familiar old photograph and consumers barely noticed a difference in the resulting image, but there are very few limitations on how the RAW data could be handled and reality could be reconstructed in any number of ways. For as long as there’s an approximate consensus on what reality should look like we retain a fingernail grip on the belief in the image as an objective record. But forces beyond photography and traditional publishing are already onto this new data resource, and culture will move with it whether photographers choose to follow or not.

As David Campbell has pointed out in his report on image integrity for the World Press Photo, this requires a profound reassessment of words like “manipulation” that assume the existence of a virginal image file that hasn’t already been touched by computational process. Veteran digital commentator Kevin Connor says, “The definition of computational photography is still evolving, but I like to think of it as a shift from using a camera as a picture-making device to using it as a data-collecting device.”

The differences contained in the structure and processing of a digital file are not the end of the story of photography’s transition from innocent childhood to knowing adulthood. There is so much more to grasp that very few people have yet grappled with the inevitable but as yet unimaginable impact on the photographic image. Taylor Davidson has described the camera of the future as an app, a software rather than a device that compiles data from multiple sensors. The smartphone’s microphone, gyroscope, accelerometer, thermometer and other sensors all contribute data as needed by whatever app calls on it and combines it with the visual data. And still that’s not the limit on what is already bundled with our digital imagery.

Our instruments are connected to satellites that contribute GPS data while connecting us to the Internet that links our data to all the publicly available information of Wikipedia, Google and countless other resources that know where we are, who was there before us and the associated economic, social and political activity. Layer on top of that the integration of LIDAR data (currently only in some specialist apps) then apply facial and object recognition software and consider the implication of emerging technologies such as virtual reality, semantic reality and artificial intelligence and one begins to realize the mind-boggling potential of computational imagery.

Things will go even further with the development of curved sensors that will allow completely different ways to interpret light, but that for the moment remains an idea rather than a reality. Everything else is already happening and will become increasingly evident as new technologies roll out, ushering us into a very different visual culture with expectations far beyond simple documentation.

Computational photography draws on all these resources and allows the visual image to create a picture of reality that is infinitely richer than a simple visual record, and with this comes the opportunity to incorporate deeper levels of knowledge. It won’t be long before photographers are making images of what they know, rather than only what they see. Mark Levoy, formerly of Stanford and now of Google puts it this way, “Except in photojournalism, there will be no such thing as a ‘straight photograph’; everything will be an amalgam, an interpretation, an enhancement or a variation – either by the photographer as auteur or by the camera itself.”

As we tumble forwards into these unknown territories there’s a curious throwback to a moment in art history when 100 years ago the Cubists revolutionized ways of seeing using a very similar (albeit analog) approach to what they saw. Picasso, Braque and others deconstructed the world and reassembled it not in terms of what they saw, but rather in terms of what they knew using multiple perspectives to depict a deeper understanding.

While the photographic world wrestles with even such basic tools as Photoshop there is no doubt that we’re moving into a space more aligned with Cubism than Modernism. It will not be long before our audiences demand more sophisticated imagery that is dynamic and responsive to change, connected to reality by more than a static two-dimensional rectangle of crude visual data isolated in space and time. We’ll look back at the black-and-white photograph that was the voice of truth for nearly a century, as a simplistic and incomplete source of information about what was happening in the world.

Some will consider this a threat, seeing only the danger of distortion and undetectable fakery and it’s certainly true that we’ll need to develop new measures by which to read imagery. We’re already highly skilled in distinguishing probable and improbable information and we know how to read written journalism (which is driven entirely by the writer’s imaginative ability to interpret reality in symbolic form) and we don’t confuse advertising imagery with documentary, nor the photo illustration on a magazine’s cover with the reportage inside. Fraud will always be a risk but with over a century of experience we’ve learned that we can’t rely on the mechanical process to protect us. New conventions will emerge and all the artistry that’s been developed since the invention of photography will find richer and deeper opportunities to express information, ideas and emotions with no greater risk to truth than we currently experience. The enriched opportunities for storytelling will allow greater complexity that’s closer to reality than the thinned-down simplification of 20th Century journalism and will open unprecedented connection between the subject and the viewer.

The twist is that new forces will be driving the process. The clue is in what already occurred with the smartphone. The revolutionary change in photography’s cultural presence wasn’t led by photographers, nor publishers or camera manufacturers but by telephone engineers, and this process will repeat as business grasps the opportunities offered by new technology to use visual imagery in extraordinary new ways, throwing us into new and wild territory. It’s happening already and we’ll see the impact again and again as new apps, products and services hit the market.

We owe it to the medium that we’ve nurtured into adolescence to stand by it and support it in adulthood even though it might seem unrecognizable in its new form. We know the alternative: it will be out the door and hanging with the wrong crowd while we sit forlornly in the empty nest wondering what we did wrong. The first step is to stop talking about the child it once was and to put away the sentimental memories of photography as we knew it for all these years.

It’s very far from dead but it’s definitely left the building.

Tuesday, June 14. 2016

Breatheable Food | #air #food #particles

Note: the architecture (of atmospheres) could become atomized into fine particles that aggregate in different manners along time, following different "rules" (these "rules" being the ones to be designed by the architect).

While we digg into sensors than monitor elements of the atmosphere (physical and non physical elements), we're definitely looking for a kind of architecture that would "deal" with these elements/particles and recompose them.

Via Cabinet (Spring 2001)

-----

By David Gissen

In the history of architecture and design there have only been a few "effects"—electric light, forced air—that have had the capacity to cause massive environmental and behavioral shifts. Last year at Barcelona's annual design fair, the Catalonian designer Marti Guixe presented another—breathable food. "Pharma-food, a system of nourishment by breathing," is an appliance that was developed by Guixe to explore the transformation of food into pure information.

Dust Food Muesli. Photos: Inga Knölke.

Pharma-food joins the work of other, primarily European, designers who are exploring alternative regimens for such activities as washing or eating. One of Guixe's Catalonian contemporaries, Ana Mir, is exploring a technology that allows one to wash without water. Like Guixe's approach, this project would allow washing to occur anywhere. In their work, these designers not only free regimens from their fixed location in relation to certain products; they also free these activities from their traditional engagement with the body. Unlike designers such as Philippe Starck or Richard Sapper, who strive to revise traditional technologies, Guixe has discovered that the problem of eating does not involve the design of a new type of stove, sink, or refrigerator—the problem of eating requires finding a new mouth.

Pharma-BAR. Photo: Inga Knölke.

Guixe, who has been studying alternative forms of eating for several years, realized that the breathing of "food" already occurs via the inhalation of dust that hangs in the air at work and at home. Guixe hypothesized that this form of eating, from which one gains a miniscule amount of minerals and vitamins, could be trans-formed into a more potent meal, a "dust-muesli," that would supply a powerful dose of nutrients. The Pharma-Food appliance, which sprays this ærosolized nutrition, connects to a computer and requires Microsoft Excel to enter exact values for such things as riboflavin, vitamin C, and protein. The combination of these nutrients are saved on the computer as documents with names such as "SPAMT," which has the nutrient "language" of tomatoes and bread, and "Costa Brova," a "seafood" dish that is heavy on the iodine and light on carbohydrates. Guixe imagines diners composing these "meals" and sending them as e-mail attachments to other owners of the Pharma-food emitter. "Like MP3," says Guixe.

While Guixe has explored the experience of eating this information, less explored and of equal significance is where this type of eating can now take place. Guixe imagines Pharma-food in a special "Pharma-bar," essentially a simple room with tables and chairs and several emitters. But why is this necessary when he has liberated food from kitchens and from forms of ingestion that require utensils and dishes? Pharma-food will allow eating to occur anywhere at any time; on subways, in cars, in our beds, while exercising, sleeping, or making love. Most interesting is what effect this device will have on the home, particularly the American home, which is dominated by the kitchen. While technologies are given free range at work and in other public spheres, the home is typically the place where devices such as Pharma-food are tamed and held in balance by a previous technology that the new device is meant to replace. Central heat did not eliminate the fireplace; it allowed this formerly grimy, soot-filled artifact to become an æsthetic symbol and heart of the American home. People began using fireplaces less, but when they did, they burned wood in them again instead of coal. Similarly, cooking the monthly meal may involve stoking a wood-fueled, cast-iron stove while simultaneously breathing a few appetizers with friends.

-

David Gissen is associate curator for architecture and design at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. He is currently developing an exhibition on human conveyance (elevators, escalators and moving sidewalks) and one on flying buildings.

Related Links:

Friday, January 15. 2016

Designers & Books | #readings

Note: it is not too late to wish everybody a happy '16, so, here I do! ... even so the year started in such a sad way with the disappearance of this shiny artist called David Bowie.

Maybe is it then already the right time to bring back our good old '16 resolutions, so to conjure these bad vibes? For my part, some of them were about reading... like always (or adding books on my already too big pile I can guess) and while I was wandering here and there on the Net late last December, I stumble upon this interesting initiative of curated lists of books related to design and art. Curators of books include readers such as Peter Eisenman, Tonny Dunne, Sou Fujimoto, Massimo Vignelli, John Maeda and many others (177 designers to date, 34 commentators, 73 guests, etc.).

Well... interesting line up I must say! Have a good '16 reading ...

-----

" Designers & Books is an advocate for books as an important source of inspiration for creativity, innovation, and invention. The main way we do this is by publishing lists of books that esteemed members of the international design community identify as important, meaningful, and formative—books that have shaped their values, their worldview, and their ideas about design. This provides the direction for our focus on books about architecture, fashion, graphic design, interactive design, interior design, landscape architecture, product and industrial design, and urban design. "

Wednesday, December 30. 2015

Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957 | #exhibition #radicalpedagogies #book

Note: could a perfect ending for this year be this post about (yet another) new exhibition (in Boston)? It is about the fantastic, the radical and the utopian Black Mountain College in North Carolina that became an important school for a large part of the post-war avant-garde in the United States/East coast.

It was an "adventure in progressive education" which points again how schools, when they remain "wild" enough, can become important structures to crystalize creative energies and momentum (and that is therefore also logically listed in Beatriz Colomina's research project about historical "Radical Pedagogies" in architecture).

Via MIT Press

-----

"Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957," an exhibition currently showing at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, focuses on how Black Mountain College (BMC) became a seminal meeting place for many of the artists, musicians, poets, and thinkers who would become the principal practitioners in their fields of the postwar period. "Leap Before You Look," the first exhibition in the US to examine BMC as a hotbed for the American avant garde, opened on October 10, 2015 and will show through January 24, 2016. Senior Production Coordinator Christine Savage recently checked it out and shares the following insights:

The story of Black Mountain College (BMC) serves as an excellent reminder of how brilliant, prolific, and innovative people can be. The school was an idyll, an embodiment of a progressive, collaborative, utopian future. The college was also an absolute anomaly, and serves possibly as an even better reminder of how rarely we come together to achieve such promise.

If only it hadn’t gone broke and closed after only 24 years.

“Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957” is a remarkable exhibit that does a wonderful job of illustrating BMC’s proud stature among the great artistic moments in the last century. The collection features music and dance performances, as well as over 200 pieces of artwork created at the college. A history of the school and the art created there can be found in the MIT Press book, Black Mountain College: Experiment in Art edited by Vincent Katz, which documents the brief—but influential—existence of the school, and offers a fascinating glimpse of campus life.

BMC was a tiny school with a disproportionate influence on art and culture in the 20th century. (A partial—yet still absurdly impressive—list of artists who taught and studied there includes Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, Josef and Anni Albers, Jacob Lawrence, Ruth Asawa, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Cy Twombly, Kenneth Noland, Vera B. Williams, Franz Kline, Buckminster Fuller, Francine du Plessix Gray, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Dorothea Rockburne, and Walter Gropius.)

Founded in 1933 at a former summer camp with 22 students in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, BMC was an adventure in progressive education. Less an art school than a perpetually broke experimental liberal arts college, the program’s philosophy centered around the belief that artistic experience was instrumental to all aspects of learning and grew students into better—and more curious—democratic citizens. Fortunately for art lovers the world around, BMC’s college life and curriculum revolved around the artistic process at a critical moment when American Progressivism combined with European Modernism.

Photographs at the start of the exhibit show the communal, egalitarian style of living and working at the school. The faculty owned and operated the college, and governed it together with students. In the early 1930s, sweat equity was more useful than tuition—they grew their own food, cooked their own meals, and built their own classrooms.

The founders of BMC kicked off their utopian educational experiment by hiring Bauhaus artists Josef and Anni Albers, who brought with them a healthy dose of enthusiasm for communal idealism and experimentation. These values remain evident in the profoundly interdisciplinary art created at the college during its brief existence, spanning painting, sculpture, ceramics, textiles, poetry, dance, music, and theater.

The exhibit begins with the colorful geometric paintings and prints of Josef, and the striking, modernist weavings and jewelry of Anni. In nearby rooms, photographs and models showing Buckminster Fuller’s experimental architecture—and the oftentimes unsuccessful attempts at constructing it—sit in conversation with the geometric and organic drawings and sculptures of Ruth Asawa, as well as the vibrant, expressionistic paintings of Elaine and Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline.

Later in the exhibit, the artistic creations of Merce Cunningham, John Cage, and Robert Rauschenberg showcase the collaborative, bodily nature of the work at BMC. Displays and performances using their choreography, music, and set decorations—schedules of which are available on the ICA website—allow museum visitors to share in an experience that, well, grew from shared experience.

As one might expect from the school’s summer camp beginnings, it was a perfect storm of intense closeness, idealism, freedom, and collaboration. Throughout the ICA’s galleries, the works of art from BMC seem to speak to each other, and to be in their presence is to get a glimpse of how their creators exemplified the school’s motto of “learning through doing.”

It’s an education in the importance of experimentation and exposure to difference, and a chance for (oft-maligned) utopian idealism—however short-lived—to get a little vindication.

Monday, December 21. 2015

Gramazio Kohler celebrates 10 years of research in digital fabrication at ETHZ in a video | #digitalfabrication #researchbydesign

-----

One decade of Gramazio Kohler Research at ETH Zurich – The Architecture of Digital Fabrication from Gramazio Kohler Research on Vimeo.

Friday, October 02. 2015

I&IC at Renewable Futures Conference in Riga | #thinking #speculation #futures

Via iiclouds.org

-----

The design research Inhabiting and Interfacing the Cloud(s) will be presented during the peer reviewed Renewable Futures Conference next week in Riga (Estonia), which will be the first edition of a serie that promiss to scout for radical approaches.

Christophe Guignard will introduce the participants to the stakes and the progresses of our ongoing experimental work. There will be profiled and inspiring speakers such as Lev Manovitch, John Thackara, Andreas Brockmann, etc.

Christophe Guignard will make a short “follow up” about the conference on this blog once he’ll be back from Riga.

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.

Quicksearch

Categories

Calendar

|

|

July '25 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||