Thursday, April 30. 2009

Sarkozy veut «voir grand» pour le Grand Paris

Transports, logement, tours... Le chef de l'Etat a dessiné ce mercredi sa vision du Grand Paris, dont le chantier devra démarrer «avant 2012».

«Il faut voir grand. Il n'y a pas de fatalité de la métropole invivable.(...) Une ville n'est grande que si elle est grande aux yeux de tous ses hommes.» C'est un Nicolas Sarkozy aux accents lyriques qui a présenté ce mercredi après-midi sa vision du Grand Paris, à la Cité de l'Architecture à Paris.

Durant une quarantaine de minutes, le chef de l'Etat a détaillé les grands axes de ce projet qui a pour lui «une importance capitale»: architecture, transport, logement... Le tout étant placé sous la houlette de Christian Blanc, secrétaire d’Etat à la Région Capitale. Et le Président veut faire vite: le chantier devra démarrer «avant 2012», avec comme objectif de «faire le Grand Paris en dix ans».

Premier grand principe de cette agglomération remodelée: le développement de la vallée de la Seine, jusqu'au Havre, qui doit devenir «le port du grand Paris», «à une heure de la capitale». Le canal Seine-Nord «permettra de désenclaver la Seine dès 2010», a promis le chef de l'Etat, qui veut «reconquérir les berges de la Seine, de la Marne, du canal de l'Ourcq.»

Après quelques considérations sur Victor Hugo, «le vrai, le beau, le grand» et le relativisme de la beauté — «La beauté, on l'a trop oubliée. Sans doute le beau est-il subjectif... Mais ce n'est pas une raison pour éluder la question!» — Nicolas sarkozy s'est dit favorable à la construction de tours: «On peut construire haut, pourquoi s'interdire des tours si elle sont belles?» De même qu'à la réalisation à Roissy d'une forêt «d'un million d'arbres».

«70.000 nouveaux logements par an»

Le chef de l'Etat a également tranché sur la question du nouvel emplacement de la Cité judiciaire: «Elle doit s'installer aux Batignolles.» Avant les Batignolles (XVIIe arrondissement), le projet d'un déménagement du palais de justice, actuellement dans l'île de la Cité (Ier), avait tourné autour du XIIIe arrondissement et du nouveau quartier Paris Rive Gauche.

Mais les principales annonces du discours présidentiel concernent le logement et le transport.

S'agissant du logement, Sarkozy promet «la construction de 70.000 logements par an, soit le double du rythme actuel». Comment ? «Le problème n'est pas le foncier, c'est la réglementation, a-t-til martelé. Il faut déréglementer. Libérer l'ordre de l'urbanisme, élever le coefficient d'occupation des sols, rendre constructibles les zones inondables par des bâtiments adaptés, utiliser les interstices.»

Les transports, dans le Grand Paris tel que le conçoit le Président, seront d'autre part considérablement renforcé. «Se déplacer pour aller travailler est devenu un enfer pour des millions de gens. Ça ne peut plus durer.»

Le chef de l'Etat souhaite d'abord «optimiser le réseau existant»: faire fonctionner les transports la nuit, avoir une seule régulation du trafic pour le réseau RATP et celui de la SNCF. Et pourquoi pas une tarification unique: «On pourra pas faire l'économie de cette réflexion».

35 milliards d'euros

Mais il faut aussi, selon lui, compléter le réseau: prolonger la ligne 14, créer une liaison rapide Roissy-gare du Nord... Et, c'est l'un des grands points du volet transport, créer un un «nouveau système» pour relier, en boucle, les grands points de polarité, sur 130 km. Ce supermétro sera «si possible aérien, rêvons qu'il soit une vitrine mondiale de notre savoir-faire en matière de transport». Ce «grand huit» (21 milliards d'euros) reliera des pôles d'activité (Roissy, Orly, La Défense, Saclay, Massy, Clichy-Montfermeil, Noisy, grand hub multimodal à Saint-Denis/Pleyel...) et les principaux centres d'habitat.

Le financement de l'opération, que le chef de l'Etat chiffre à 35 milliards en tout, reposera sur «des investissements» mais aussi sur «la valorisation du foncier», «l'augmentation de la fréquentation des transports en commun» et les partenariats public-privé.

Un projet de loi sera déposé en octobre qui fixera les «modalités de maîtrise d'ouvrage des structures juridiques, et de modalités de financement».

-----

Via Libération

Related Links:

Personal comment:

Quelques idées intéressantes mais on est dans le réalisme et les idées "usual suspects" actuelles: densification, transports publics, connectivité aux réseaux (pensés plutôt réseaux physiques de transports), éco-quartiers ou éco-tours, quartiers-tours, etc.

Pas vraiment d'utopies ou de grandes idées même si le Grand Paris est probablement déjà en soi une grande idée...

Mediated Space. Or: How to translate the logic of media into architecture

Recently I visited a seminar on Mediated Space at the Harvard School of Design. The organizers turned the usual approach to this topic - how is our experience of space changing, now that media ranging from mobile phones to urban screens have all but colonized our every day urban life? - around. Rather they, asked, how have media technologies changed our conceptualizations of space, and how has architecture embraced these shifting conceptualizations; that is not so much by integrating media into built forms (let’s say by adding a screen to a facade), but by translating the logic of a new media technology (let’s say the logic of cinematic montage) into spatial design.

In her opening lecture, Eve Blau gave two interesting examples, one historical and one contemporary.

|

|

First she turned to the mutual exchange of ideas and concepts by modernist avant gardes such as architect Mies van der Rohe, artist/ filmmaker Hans Richter and painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, artists in different disciplines experimented with new modes of spatial representation brought about by cinema and photography. These experiments in turn made their way into architectural design.

Blau argued that the Tugendhat Villa in Brno designed by Van der Rohe - ‘the most cinematic architect of that era’ - was a manifestation of the spatial and sequential logic of film. There are no screens or moving parts in the villa, but Van der Rohe explores the idea of relational space in a way that, Blau argues, is reminiscent of cinema. The villa is layed out in a number of demarcated but linked spatial zones, such as the kitchen, the living room and the dining room. She imagined how the inhabitants, would move from one space on to the next as the rhythms of every day life would unfold. The rhythm of the spaces reminded her of the rhythms of Hans Richter’s abstract film experiments, and she connected the movement of time through the different spaces with a cinematic montage of shots.

In a similar way, in our time the computer and the internet provide us with new ways to visualize and conceptualize spatial relations. And also these new modes of thinking are making their way into architecture. This is best represented by the Toledo Glass Pavilion by SANAA, a museum building recently built in Spain.

|

As its website states, in this building …

… all exterior and nearly all interior walls consist of large panels of curved glass, resulting in a transparent structure that blurs the boundaries between interior and exterior spaces

The glass pavilion has incorporated the logic of digital media, not by assimilating it into the building, but by incorporating its logic: The glass structure of the pavilion inner and outer walls symbolize a new set of social relations, where everyone can observe and relate to everyone else anywhere in the building, and every piece of information is visible in multiple spaces. The space itself is not prescribed by the program, but open for multiple uses, its character determined not so much by its formal definitions, but by its uses. Even public and private spaces are not clearly demarcated, also this is a modality that is being defined by its usage rather than its programmatic function. Private space is being made by retreating, public by interaction and both can happen virtually anywhere in the building.

-----

Via The Mobile City

Related Links:

Personal comment:

Le terme "mediated space" ou "mediated relation to space" que nous utilisons dans nos conférences depuis 2-3 ans et qui fait ici l'objet d'un symposium à Harvard (School of Design), mais avec un "twist" dans l'approche.

Comme quoi...

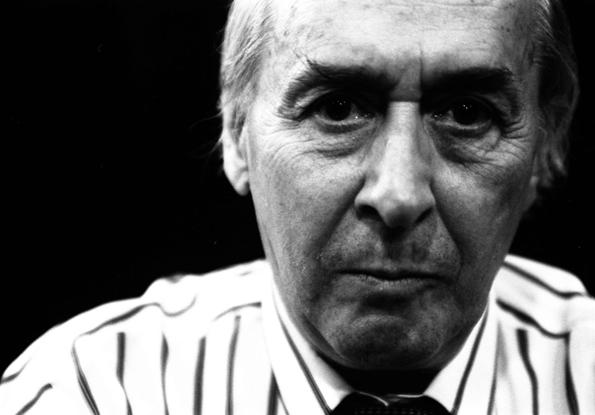

J G Ballard: 1930-2009

A homage to J G Ballard, the writer who saw terror and poetry in the city landscape

I am glad I didn’t ask to interview JG Ballard at his home in Shepperton in 2003, and instead chose to meet him at the Hilton hotel on Holland Park Avenue, West London - ironically a far more Ballardian building than his own home. “We could be anywhere!” he said to me, approvingly.

Very few writers’ names coin an adjective, but Ballard’s has. ‘Ballardian’ has come to refer to ‘dystopian modernity, bleak manmade landscapes and the psychological effects of technological, social or environmental developments’, according to the Collins English Dictionary. His fiction has always taken inspiration from the built environment - particularly the utopian dream of modernist architecture - and he was especially interested in the latent content of buildings, what they represented psychologically (or “does the angle between two walls have a happy ending?” as he once obliquely put it), and was an original and brilliant architecture critic in his own right. He was the only writer, for example, to notice that before 9/11 no one had considered the World Trade Centre to be a symbolic target at all - indeed, he noted, that was the whole point, it was a meaningless act and it was this that people found so unsettling.

I first met Ballard in 1997 at a Soho press screening for David Cronenberg’s Crash at which, slightly unnervingly, he sat directly behind me. The novel that the film was based on, along with its precursor The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), is perhaps the most outre of his work, exploring the sexuality of the car crash and its psychotic protagonist Vaughan’s desire to drive off a motorway flyover and collide with Elizabeth Taylor’s car.

The handful of occasions I spoke to him since then were exhilarating autopsies of a whole host of subjects, including multi-storey car parks (‘One of the most mysterious buildings ever built. What effect does using these buildings have on us? Are the real myths of this century being written in terms of these huge unnoticed structures?’), and his favourite building in London, Michael Manser’s Heathrow Hilton (1992) (‘Sitting in its atrium one becomes a more advanced kind of human being. One feels no emotions and could never fall in love.’). When talking to him, I recalled Will Self’s observation that ‘Ballard rolls the phrases around in his mouth as if they were ironic boiled sweets’.

His disaster novels of the 1960s - The Wind From Nowhere (1961), The Drowned World (1962), The Burning World (1964) and The Crystal World (1966)- revelled in their environmental cataclysms, which now seem eerily prescient. It was in the early 1970s with the novels Concrete Island (1974), High Rise (1975) and Crash (1973) that Ballard became the ‘poet of the motorways’, in which his protagonists embrace their hostile surroundings. In Concrete Island, Ballard maroons ‘wealthy architect’ Robert Maitland - Crusoe-like - in a triangular interzone of a motorway intersection. Maitland decides to stay there rather than go back to his former life.

Ballard once famously said that ‘the future is going to be boring’ and that the whole world is ‘turning into a suburb of Dusseldorf’.

Ballard once famously said that ‘the future is going to be boring’ and that the whole world is ‘turning into a suburb of Dusseldorf’. In his later fiction, he turned to dissecting the infinite leisure that is awaiting us all, which he first wrote about in Vermilion Sands (1971) about an imaginary holiday resort. In Cocaine Nights (1996), Super-Cannes (2000) and Millennium People (2003), Ballard looked at gated communities and the nerve tonic of violence that was needed to shock his characters out of consumer capitalism. Ballard told me that whereas the 20th century was mediated through the car, the 21st century would be mediated through the home.

For Ballard, psychology and space were intertwined. His terrifying short story The Concentration City (1967) concerns a physics student, Franz, who tries to escape a seemingly illimitable city but who after 10 days of travelling realises he has arrived back to the same place and on the same day. Billennium is another superb short story about the psychological effects of overcrowding in which two young men discover a secret, larger-than-average room next to their own cubicle in a vast city. As they enjoy the extra personal space that they have never known, they allow their friends to share the space, which eventually ends up the same size as the room they were trying to escape from in the first place …

In a brilliant essay for The Guardian in 2006 in which he wrote about the blockhouses of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall on Utah beach, Ballard lamented the death of the utopian project of the ‘heroic period of modernism from 1920 to 1939’ – ‘We see its demise in 1960s kitchens and bathrooms, white-tiled laboratories that are above all clean and aseptic, as if human beings were some kind of disease. We see its death in motorways and autobahns, stone dreams that will never awake, and in the Turbine Hall at that middle-class disco, Tate Modern - a vast totalitarian space that Albert Speer would have admired, so authoritarian that it overwhelms any work of art inside it.’

Reading back my notes from an interview from 2003, I see how prescient he was about the speculative housing boom – ‘It’s our South Sea Bubble’ he told me (see online). Also, I see that we spoke about the inevitability of a terrorist attack in London. With Ballard gone, so is our early warning system.

-----

Personal comment:

Intéressant article publié par The Arhitect's Journal à propos de l'intérêt que J.-G. Ballard portait à l'architecture et en quoi celle-ci était centrale à sa pensée. Bien entendu, pas uniquement l'architecture, mais aussi la technologie, les sciences, la critique sociale, la psychologie et le dystopisme constituaient les ingrédients principaux de sa littérature.

Monday, April 27. 2009

Gramazio & Kohler Installation: West Fest, Zurich

The Digital Fabrication unit of Gramazio & Kohler at the ETH Zurich has just completed a wooden, robot-fabricated pavilion near Zurich. The research group was invited by the city to design and fabricate an 8 x 8 meter installation for the West Fest, a festival to celebrate the opening of a new tunnel.

-----

Via Jargon, etc.

Personal comment:

La plus grosse structure (volumétrique) réalisée à ce jour par Gramazio & Kohler avec leur robot. A ma connaissance en tout cas.

Bien que je trouve la démarche intéressante, je constate que la démarche aboutit de plus en plus à des "motifs", presque un caractère fondamentalement décoratif alors que le statut de l'espace n'est pas vraiment questionné.

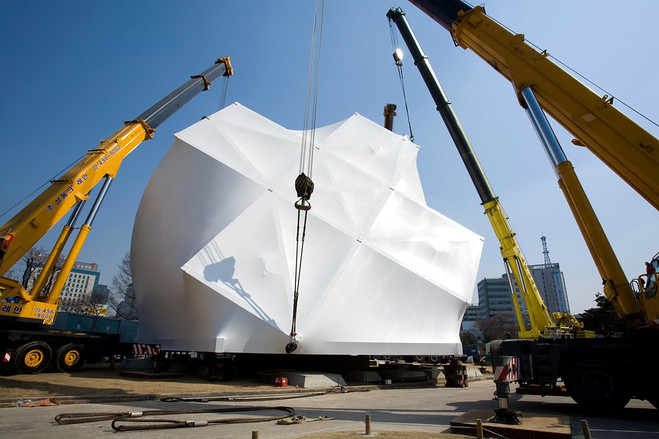

First Look: Prada Transformer

Rem Koolhaas’s rotating Prada Transformer structure in Seoul

By: Evan Ramstad

-

Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas turned a museum into a store for Prada in New York. And he built a store without a façade for Prada in Beverly Hills. Now, he’s created a building that moves for Prada on the grounds of a 500-year-old Korean palace.

Called the Prada Transformer, the four-sided, pyramid-like building will open Thursday night with a gala hosted by designer Miuccia Prada and Mr. Koolhaas. The building is a steel frame wrapped in a polyvinyl covering known as “cocoon” that was initially developed by the U.S. Army to protect aircraft and vehicles in storage. Even so, the structure weighs 160 tons and takes four cranes to lift and rotate.

The fashion house is using Transformer as a pavilion to house the company’s “Waist Down” exhibit, a series of twirling skirts that has already been shown in New York, Los Angeles and Tokyo, for the next month. Later, it will be used for a film festival, fashion shows and an art exhibit.

For each new purpose, the Transformer will be lifted up by cranes, rotated and set down on another of its four sides. For the “Waist Down” exhibit, the building sits on a hexagon. For the film festival, a rectangle; the fashion show, a circle; and the art exhibit, a cross.

“When you follow the concept form follows function, you want to express every program in the form of an entity. So we decided to make a movable object, which represents every single program in an ideal way,” says Alexander Reichert, senior architect for Koolhas’ Office for Metropolitan Architecture, the Rotterdam firm that has done numerous projects for Prada. “The concept really is that it has a life, which is expressed through its rotation,” Reichert says.

Prada decided two years ago she wanted to do an attention-getting project in South Korea, a growing market for luxury brands that is often overshadowed by nearby Japan and China. The country’s own fashion industry is still relatively small and South Koreans tend to be more communal than individual in style.

But Seoul’s university-age women and men are starting to display more flair. And the city’s mayor is behind a design campaign to both beautify its cluttered neighborhoods and build its reputation among the global architecture crowd. “There’s a lot of interest in this project,” says Ahn Song-eun, one of eight South Korean university students whose designs were selected to appear with Ms. Prada’s in the “Waist Down” exhibit. “Many Koreans are amazed this is happening in Seoul.”

Local officials initially suggested locating the Prada pavilion in the park that was the site of the 1988 Summer Olympics, off on the southeast edge of the city. But Koolhaas and Prada wanted it in a place closer to business and shopping areas.

The space between the outer and inner gates of the Gyeong-hui Palace, adjacent to the Seoul Museum of History, seemed perfect. The palace is the smallest and least-visited of three palaces near a giant boulevard in the heart of the city. But its setting, rising up a small hill on one side and looking down a street of new office buildings on the other, is by far best-suited to a visually-striking addition like the Transformer.

“You have a horizontal, very grounded palace and a modern, rotating object,” Reichert says. “Visually as well as conceptually, there are two worlds of architecture next to each other. The pavilion benefits from the palace and the palace gets something from the pavilion. It’s just a beautiful background, one way or the other.”

The elastic membrane around the around the structure brings a level of abstraction to the Transformer that Reichert describes as between art and architecture. “There are elements in there like the air conditioner that make the structure very sophisticated,” he says. “Even though it is sophisticated, it doesn’t appear as such. That’s why I think it’s like something in between.”

Of course, on another level, the Transformer is also a giant engineering problem: a four-story object that’s supposed to be rotated every two months or so.

Construction crews earlier this month held three practice sessions doing just that. Preparation takes a few hours but, by the third session, the crane operators could do the actual rotation in just 20 minutes.

While that had been the idea since the project’s conception, seeing it happen still awed Reichert. “They were sitting in the crane, smoking cigarettes and playing with a building like it’s a big toy,” he says.

For an eyewitness account of the Transformer’s opening night, see Part 2 of Evan’s report tomorrow.

---

The Prada Transformer got its name because architect Rem Koolhaas designed it to be lifted up and placed on a new side for each of four different shows that Miuccia Prada has designed for it over the next six months.

But at its debut gala Thursday night, the 66-foot-tall pavilion showed a different reason for the name – its high-tech translucent skin, which casts shadows inside during the day, sends them out at night. The changing silhouettes of party-goers inside the pavilion gave a sense of performance to those outside on the grounds of Gyeong-hui Palace, where the building will stand for the next six months.

Prada’s namesake designer was joined by Patrizio Bertelli, the CEO of Prada, and Koolhaas in hosting about 1,500 people at the opening night of “Waist Down in Seoul,” the exhibition of Prada skirts that has previously visited New York, Los Angeles, Tokyo and Shanghai. The party drew some of South Korea’s A-list models, actors, designers and other artists.

I watched as strikingly tall cover girls Song Kyung-ah and Jang Yoon-ju hung out together, taking pictures of each other and friends at the champagne bar. Jang has been called Korea’s Carla Bruni after recording her first album last year.

Actor Daniel Henney, a Korean-American who has been in TV shows and movies in both countries, says it was his last night in the country before heading back to the U.S. to do more promotion for “X-Men Origins: Wolverine” in which he co-stars. Henney and the movie’s star, Hugh Jackman, drew a huge crowd earlier this month at an event in a city park just a few blocks from the palace.

Among the most excited to be there were eight students from fashion design programs around South Korea who were chosen to exhibit their work with Prada’s, the first time the “Waist Down” show has expanded in such a way. Ahn Song-eun, of Seoul’s Ewha University, designed a skirt based on traditional Korean ink painting with strands of shiny silk to give it a futuristic edge. “I think it fits in this modern exhibition,” she says, looking off at the hidden machinery that spun and flapped Prada’s skirts.

The 500-year-old palace provided a striking counter-point to the steel and polyvinyl-wrapped pavilion and the exhibit of Prada skirts. Opening night capped two-and-a-half months of construction.

Among the people celebrating the opening with Koolhaas’ architects and technical crew was a group of executives and engineers from Cocoon Holland BV, whose business cards boast of “coatings, conservation and mothballing.”

About a year ago, Koolhaas’ people called Cocoon to ask whether its plastic-leathery fabric, which can be sprayed into shape and is usually used to cover parked airplanes and tanks, could be used as the skin of a building. When they said yes, the Koolhaas team pushed Cocoon to come up with a translucent version of the fabric, an innovation that now seems to be one of the most far-sighted ideas of the Prada Transformer. In the daytime, bright light from outside sends shadows of trees through the fabric and into the pavilion. At night, the opposite happens as lights inside cast silhouettes on the pavilion’s walls.

Cocoon managing director Alexander van der Zee never thought his business would be associated with a project such as this. And the gala was even more removed from his imagination. “We preserve airplanes, oil rigs, big spare parts for oil tankers,” he says. “Usually when we’re done with something, people just say ‘See you next time.’”

Later this year, the pyramid-like pavilion will be rotated three times – its rectangle side used for a cinema, its circle side for a fashion show and its cross side for an art gallery. In October, construction crews will take it apart and recycle the membrane and steel to be used elsewhere.

All photos courtesy of Prada and Evan Ramstad.

-----

Via The Wall Street Journal

Related Links:

Personal comment:

The coming back of the old radical idea of a "movable", "variable" architecture (dated back from the "radical architectures" period of the late 1960ies --Archigram, Superstudio, Haus Rücker Co, etc.). In this specific case, it consist of a rotating structure (4 sides) dedicated to four different programs. Noticably, it is also a "communicating architecture" as it serves for the promotion of Prada's campain and shows in Seoul.

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.