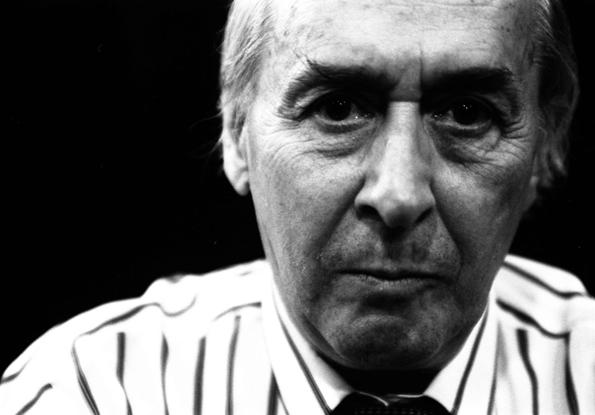

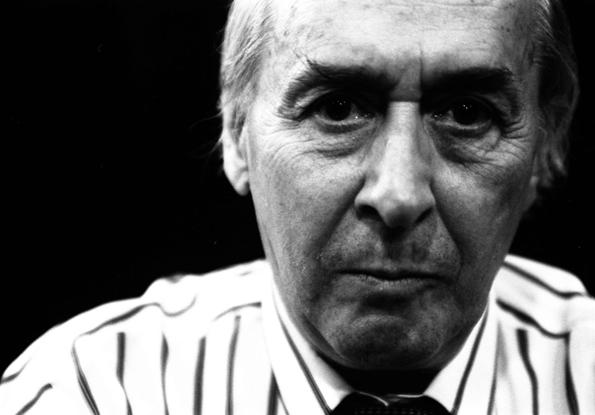

A homage to J G Ballard, the writer who saw terror and poetry in the city landscape

I am glad I didn’t ask to interview JG Ballard at his home in Shepperton in 2003, and instead chose to meet him at the Hilton hotel on Holland Park Avenue, West London - ironically a far more Ballardian building than his own home. “We could be anywhere!” he said to me, approvingly.

Very few writers’ names coin an adjective, but Ballard’s has. ‘Ballardian’ has come to refer to ‘dystopian modernity, bleak manmade landscapes and the psychological effects of technological, social or environmental developments’, according to the Collins English Dictionary. His fiction has always taken inspiration from the built environment - particularly the utopian dream of modernist architecture - and he was especially interested in the latent content of buildings, what they represented psychologically (or “does the angle between two walls have a happy ending?” as he once obliquely put it), and was an original and brilliant architecture critic in his own right. He was the only writer, for example, to notice that before 9/11 no one had considered the World Trade Centre to be a symbolic target at all - indeed, he noted, that was the whole point, it was a meaningless act and it was this that people found so unsettling.

I first met Ballard in 1997 at a Soho press screening for David Cronenberg’s Crash at which, slightly unnervingly, he sat directly behind me. The novel that the film was based on, along with its precursor The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), is perhaps the most outre of his work, exploring the sexuality of the car crash and its psychotic protagonist Vaughan’s desire to drive off a motorway flyover and collide with Elizabeth Taylor’s car.

The handful of occasions I spoke to him since then were exhilarating autopsies of a whole host of subjects, including multi-storey car parks (‘One of the most mysterious buildings ever built. What effect does using these buildings have on us? Are the real myths of this century being written in terms of these huge unnoticed structures?’), and his favourite building in London, Michael Manser’s Heathrow Hilton (1992) (‘Sitting in its atrium one becomes a more advanced kind of human being. One feels no emotions and could never fall in love.’). When talking to him, I recalled Will Self’s observation that ‘Ballard rolls the phrases around in his mouth as if they were ironic boiled sweets’.

His disaster novels of the 1960s - The Wind From Nowhere (1961), The Drowned World (1962), The Burning World (1964) and The Crystal World (1966)- revelled in their environmental cataclysms, which now seem eerily prescient. It was in the early 1970s with the novels Concrete Island (1974), High Rise (1975) and Crash (1973) that Ballard became the ‘poet of the motorways’, in which his protagonists embrace their hostile surroundings. In Concrete Island, Ballard maroons ‘wealthy architect’ Robert Maitland - Crusoe-like - in a triangular interzone of a motorway intersection. Maitland decides to stay there rather than go back to his former life.

Ballard once famously said that ‘the future is going to be boring’ and that the whole world is ‘turning into a suburb of Dusseldorf’.

Ballard once famously said that ‘the future is going to be boring’ and that the whole world is ‘turning into a suburb of Dusseldorf’. In his later fiction, he turned to dissecting the infinite leisure that is awaiting us all, which he first wrote about in Vermilion Sands (1971) about an imaginary holiday resort. In Cocaine Nights (1996), Super-Cannes (2000) and Millennium People (2003), Ballard looked at gated communities and the nerve tonic of violence that was needed to shock his characters out of consumer capitalism. Ballard told me that whereas the 20th century was mediated through the car, the 21st century would be mediated through the home.

For Ballard, psychology and space were intertwined. His terrifying short story The Concentration City (1967) concerns a physics student, Franz, who tries to escape a seemingly illimitable city but who after 10 days of travelling realises he has arrived back to the same place and on the same day. Billennium is another superb short story about the psychological effects of overcrowding in which two young men discover a secret, larger-than-average room next to their own cubicle in a vast city. As they enjoy the extra personal space that they have never known, they allow their friends to share the space, which eventually ends up the same size as the room they were trying to escape from in the first place …

In a brilliant essay for The Guardian in 2006 in which he wrote about the blockhouses of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall on Utah beach, Ballard lamented the death of the utopian project of the ‘heroic period of modernism from 1920 to 1939’ – ‘We see its demise in 1960s kitchens and bathrooms, white-tiled laboratories that are above all clean and aseptic, as if human beings were some kind of disease. We see its death in motorways and autobahns, stone dreams that will never awake, and in the Turbine Hall at that middle-class disco, Tate Modern - a vast totalitarian space that Albert Speer would have admired, so authoritarian that it overwhelms any work of art inside it.’

Reading back my notes from an interview from 2003, I see how prescient he was about the speculative housing boom – ‘It’s our South Sea Bubble’ he told me (see online). Also, I see that we spoke about the inevitability of a terrorist attack in London. With Ballard gone, so is our early warning system.

-----

Via The Architect's Journal

Personal comment:

Intéressant article publié par The Arhitect's Journal à propos de l'intérêt que J.-G. Ballard portait à l'architecture et en quoi celle-ci était centrale à sa pensée. Bien entendu, pas uniquement l'architecture, mais aussi la technologie, les sciences, la critique sociale, la psychologie et le dystopisme constituaient les ingrédients principaux de sa littérature.