Friday, April 24. 2009

The Vatican intends to spend 660 million dollars to create what will effectively be Europe’s largest solar power plant. This massive 100 megawatt photovoltaic installation will provide enough energy to make the Vatican the first solar powered nation state in the world. Inhabitat | previously

-----

Via Archinect

Personal comment:

Le Vatican, micro-nation à la fois complètement obsolète et à la pointe?

Wednesday, April 22. 2009

Dan Kildee, the county treasurer of Flint, Mich., in front of the home where he lived until he was 4. He is proposing the tearing down of entire blocks and even whole neighborhoods.

FLINT, Mich. — Dozens of proposals have been floated over the years to slow this city’s endless decline. Now another idea is gaining support: speed it up. Instead of waiting for houses to become abandoned and then pulling them down, local leaders are talking about demolishing entire blocks and even whole neighborhoods. The population would be condensed into a few viable areas. So would stores and services. A city built to manufacture cars would be returned in large measure to the forest primeval. “Decline in Flint is like gravity, a fact of life,” said Dan Kildee, the Genesee County treasurer and chief spokesman for the movement to shrink Flint. “We need to control it instead of letting it control us.”

The recession in Flint, as in many old-line manufacturing cities, is quickly making a bad situation worse. Firefighters and police officers are being laid off as the city struggles with a $15 million budget deficit. Many public schools are likely to be closed. “A lot of people remember the past, when we were a successful city that others looked to as a model, and they hope. But you can’t base government policy on hope,” said Jim Ananich, president of the Flint City Council. “We have to do something drastic.” In searching for a way out, Flint is becoming a model for a different era. Planned shrinkage became a workable concept in Michigan a few years ago, when the state changed its laws regarding properties foreclosed for delinquent taxes. Before, these buildings and land tended to become mired in legal limbo, contributing to blight. Now they quickly become the domain of county land banks, giving communities a powerful tool for change.

Indianapolis and Little Rock, Ark., have recently set up land banks, and other cities are in the process of doing so. “Shrinkage is moving from an idea to a fact,” said Karina Pallagst, director of the Shrinking Cities in a Global Perspective Program at the University of California, Berkeley. “There’s finally the insight that some cities just don’t have a choice.” While the shrinkage debate has been simmering in Flint for several years, it suddenly gained prominence last month with a blunt comment by the acting mayor, Michael K. Brown, who talked at a Rotary Club lunch about “shutting down quadrants of the city.” Nothing will happen immediately, but Flint has begun updating its master plan, a complicated task last done in 1965. Then it was a prosperous city of 200,000 looking to grow to 350,000. It now has 110,000 people, about a third of whom live in poverty.

Flint has about 75 neighborhoods spread out over 34 square miles. It will be a delicate process to decide which to favor, Mr. Kildee acknowledged from the driver’s seat of his Grand Cherokee. He will play a crucial role in those decisions. In addition to being the treasurer of Genesee County, whose largest city by far is Flint, Mr. Kildee is chief executive of the local land bank. In the last year, the county has acquired through tax foreclosure about 900 houses in the city, some of them in healthy neighborhoods. A block adjacent to downtown has the potential for renewal; it would make sense to fill in the vacant lots there, since it is a few steps from a University of Michigan campus.

A short distance away, the scene is more problematic. Only a few houses remain on the street; the sidewalk is so tattered it barely exists. “When was the last time someone walked on that?” Mr. Kildee said. “Most rural communities don’t have sidewalks.” But what about the people who do live here and might want their sidewalk fixed rather than removed? “Not everyone’s going to win,” he said. “But now, everyone’s losing.” On many streets, the weekly garbage pickup finds only one bag of trash. If those stops could be eliminated, Mr. Kildee said, the city could save $100,000 a year — one of many savings that shrinkage could bring.

Mr. Kildee was born in Flint in 1958. The house he lived in as a child has just been foreclosed on by the county, so he stopped to look. It is a little blue house with white trim, sad and derelict. So are two houses across the street. “If it’s going to look abandoned, let it be clean and green,” he said. “Create the new Flint forest — something people will choose to live near, rather than something that symbolizes failure.” Watching suspiciously from next door is Charlotte Kelly. Her house breaks the pattern: it is immaculate, all polished wood and fresh paint. When Ms. Kelly, a city worker, moved to the street in 2002, all the houses were occupied and the neighborhood seemed viable.

These days, crime is brazen: two men recently stripped the siding off Mr. Kildee’s old house, “laughing like they were going to a picnic,” Ms. Kelly said. Down the street are many more abandoned houses, as well as a huge hand-painted sign that proclaims, “No prostitution zone.” “It saddens my heart,” she said. “I was born in Flint in 1955. I’ve seen it in the glory days, and every year it gets worse.” Mr. Kildee makes his pitch. Would she be interested in moving if the city offered her an equivalent or better house in a more stable and safer neighborhood? Despite her pride in her home, the calculation takes Ms. Kelly about a second. “Yes,” she said, “I would be willing.”

-----

Via The New York Times

Personal comment:

Le moment ou certaines villes (ex-industrielles) doivent planifier leur "rétrécissement". Ici Flint, Michigan (rappelez-vous le documentaire de Michael Moore --Roger & Me-- sur sa ville natale, fief de l'industrie automobile et de l'Amérique prospère dans les années 1950).

Intéressant d'un point de vue urbain mais aussi d'un point de vue conceptuel/durabilité. Will less be more (one more time)?

Tuesday, April 21. 2009

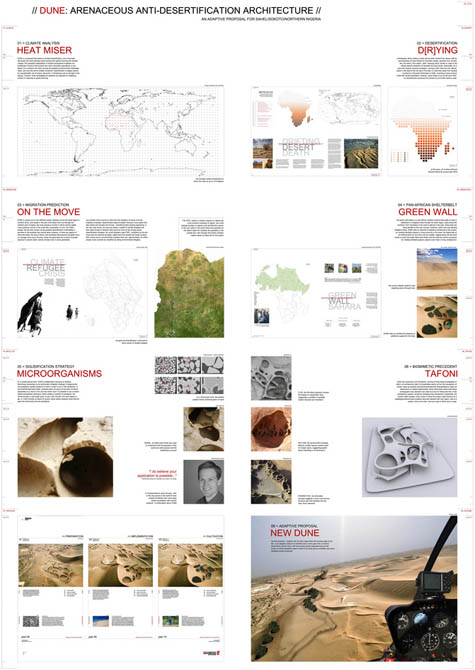

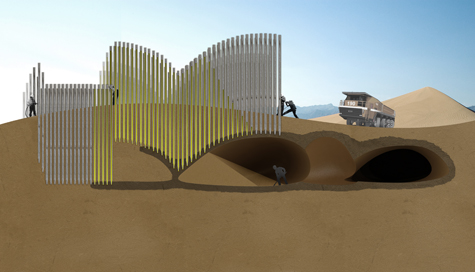

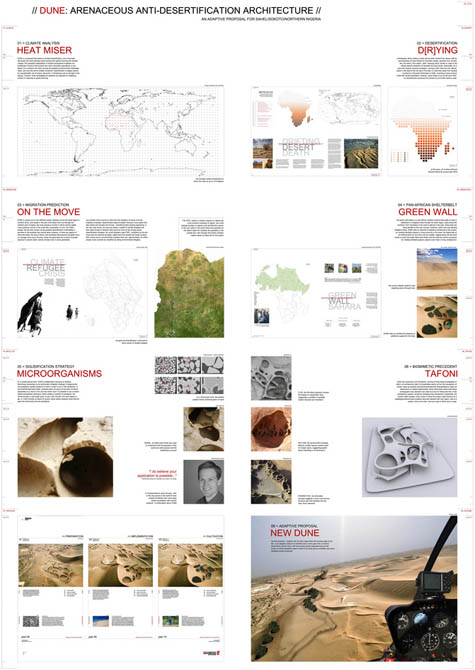

For an ambitious landscape design project, Magnus Larsson, a student at the Architectural Association in London, has proposed a 6,000km-long wall of artificially solidified sandstone architecture that would span the Sahara Desert, east to west, offering a combination of refugee housing and a "green wall" against the future spread of the desert.

[Image: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture]. [Image: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture].

Larsson's project deservedly won first prize last fall at the Holcim Foundation's Awards for Sustainable Construction held in Marrakech, Morocco.

One of the most interesting aspects of the project, I think, is that this solidified dunescape is created through a particularly novel form of "sustainable construction" – that is, through a kind of infection of the earth.

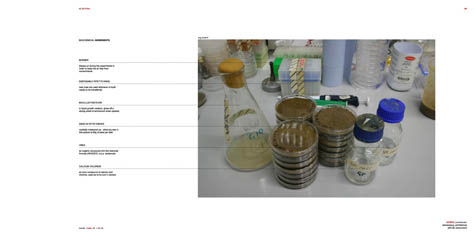

In other words, Larsson has proposed using bacillus pasteurii, a "microorganism, readily available in marshes and wetlands, [that] solidifies loose sand into sandstone," he explains.

[Image: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture]. [Image: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture].

Larsson points out the work of the Soil Interactions Lab at UC-Davis, which describes itself as "harnessing microbial activity to solidify problem soils."

But the idea of taking this research and applying it on a megascale – that is, to a 6,000km stretch of the Sahara Desert – boggles the mind. At the very least, the idea that this might be deployed for the wrong reasons, or by the wrong people, in some delirious hybrid of ice-nine, J.G. Ballard's The Crystal World, and perhaps a Roger Moore-era James Bond film, deserves further thought.

An epidemic of bacillus pasteurii infects all the loose sand in the world, forming great aerodynamic fins and waves in a kind of global Utah of glassine shapes.

[Images: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture]. [Images: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture].

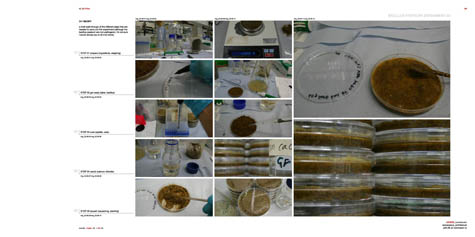

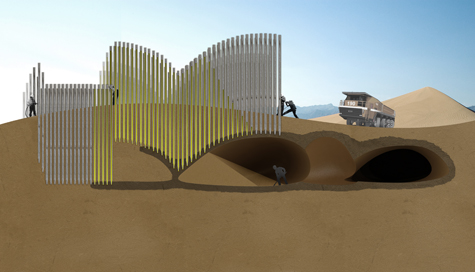

Clarifying the biochemical process through which his project could be realized, Larsson explained in a series of emails that his "structure is made straight from the dunescape by flushing a particular bacteria through the loose sand... which causes a biological reaction whereby the sand turns into sandstone; the initial reactions are finished within 24 hours, though it would take about a week to saturate the sand enough to make the structure habitable."

The project – a kind of bio-architectural test-landscape – would thus "go from a balloon-like pneumatic structure filled with bacillus pasteurii, which would then be released into the sand and allowed to solidify the same into a permacultural architecture."

[Image: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture]. [Image: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture].

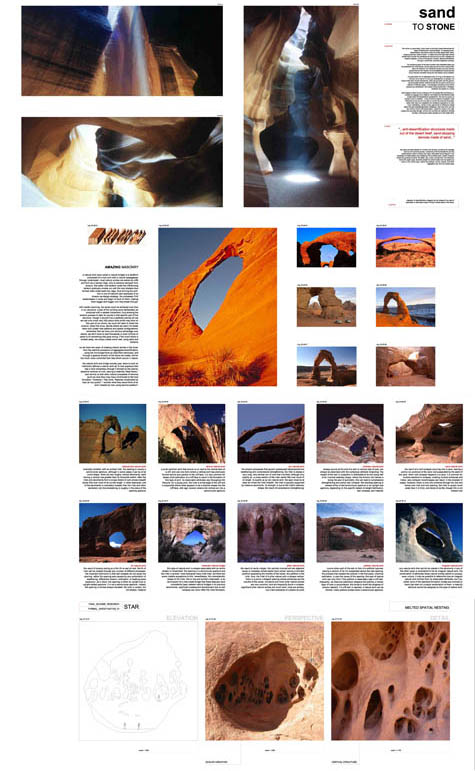

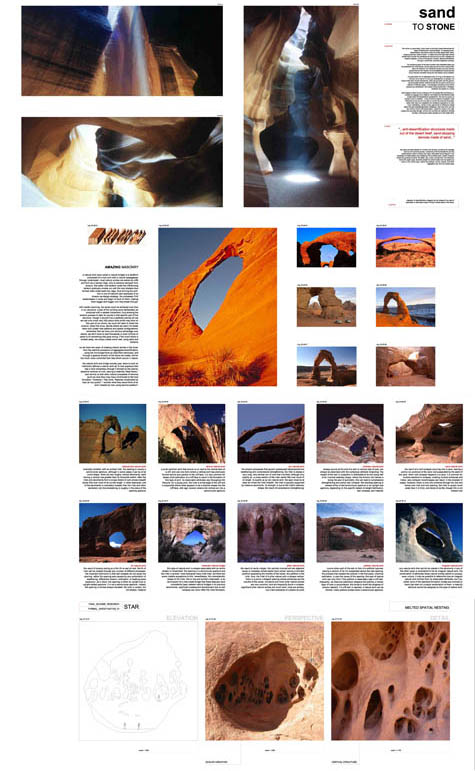

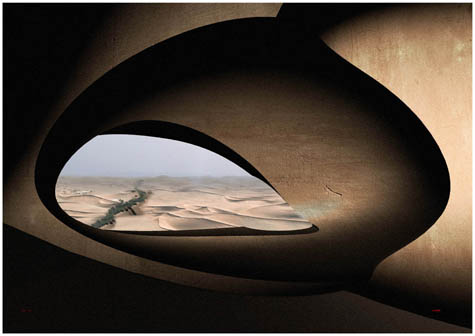

The "architectural form" of the resulting solidified sandscape is actually "derived from tafoni," Larsson writes, where tafoni is "a cavernous rock structure that formally ties the project back to notions of aggregation and erosion. On a conceptual scale, the project spans some 6,000km, putting it on a par with Superstudio's famous Continuous Monument – but with an environmental agenda."

[Images: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture]. [Images: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture].

I'm reminded of Michael Welland's recent book Sand. There, Welland describes "how deserts operate" (he compares them to "engines" of mechanical weathering); he points out that you can still find "sand-sized fragments of steel" on the D-Day beaches of Normandy, war having left behind a hidden desert of metal; and he mentions that the UK now maintains "the world's first database of sand" – but that it's used "specifically for police forensics."

Welland's descriptions of sand dune physics are particularly memorable. He writes, for instance, that an avalanche is really a sand dune being "overwhelmed by the huge number of very small events" on its surface, and that these "very small events" unpredictably lead to one decisive moment of cascading self-collapse.

[Image: A photomicrograph of sand grains]. [Image: A photomicrograph of sand grains].

Fantastically, though, and more relevant to this post, he then compares the internal structure of sand dunes to Gothic cathedrals: the grains of sand piled high form "microscopic chains and networks... in such a way that they carry most of the pressure from the weight of the material above them." This is the architecture of sand:

These chains seem to behave like the soaring arches of Gothic cathedrals, which serve to transmit the weight of the roof, perhaps a great dome, outward to the walls, which bear the load.

Briefly, though, this image can be sustained through Welland's descriptions of the great ergs, or sand seas, of today. These dune seas "are tangibly mobile, ever changing," Welland writes, "but there are larger areas of ergs past that are now fixed by vegetation."

Most of today's active sandy deserts are surrounded by vast stretches of old stabilized dunes, formed as the trade-wind belts and arid regions expanded in the cold, dry climate of the last ice age and immobilized as the climate changed. However, continuing shifts in the climate may bring these fixed ergs, granular reserves awaiting activation, back to life.

He mentions the Sand Hills of northwestern Nebraska, "formed originally from the debris of the glacial erosion of the Rocky Mountains."

The hills were stabilized eight hundred years ago but have had episodes of reincarnation since: a long drought toward the end of the eighteenth century resuscitated dunes on the Great Plains, whose activity caused problems for the westbound wagon trains decades earlier.

But if sand dunes are Gothic cathedrals, and if those dunes can come back to life, the resulting image of resuscitated Gothic cathedrals moving slowly over the American landscape is almost too incredible to contemplate.

[Images: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture]. [Images: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture].

Larsson's project descriptions maintain this somewhat hallucinatory feel:

I researched different types of construction methods involving pile systems and realised that injection piles could probably be used to get the bacteria down into the sand – a procedure that would be analogous to using an oversized 3D printer, solidifying parts of the dune as needed. The piles would be pushed through the dune surface and a first layer of bacteria spread out, solidifying an initial surface within the dune. They would then be pulled up, creating almost any conceivable (structurally sound) surface along their way, with the loose sand acting as a jig before being excavated to create the necessary voids. If we allow ourselves to dream, we could even fantasise about ways in which the wind could do a lot of this work for us: solidifying parts of the surface to force the grains of sand to align in certain patterns, certain shapes, having the wind blow out our voids, creating a structure that would change and change again over the course of a decade, a century, a millenium.

A vast 3D printer made of bacteria crawls undetectably through the deserts of the world, printing new landscapes into existence over the course of 10,000 years...

[Image: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture]. [Image: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture].

Larsson goes on to contrast his method with existing vernacular techniques of anti-desertification:

Traditional anti-desertification methods include the planting of trees and cacti, the cultivation of grasses and shrubs, and the construction of sand-catching fences and walls. More ambitious projects have ventured into the development of agriculture and livestock, water conservation, soil management, forestry, sustainable energy, improved land use, wildlife protection, poverty alleviation, and so on. This project, apart from utilising a completely new way of turning sand into sandstone, incorporates all of the above. Inside the dunes, we can take care of our plants and animals, find water and shade, help the soil remain fertile, care for the trees, and so on. In this way, it's an environmental project that hopefully provides an innovation for other architects/builders to use and copy time and time again.

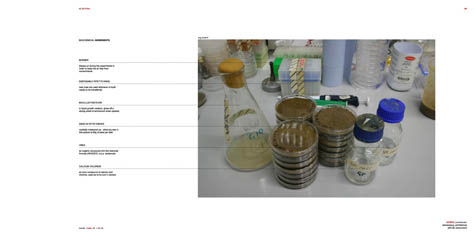

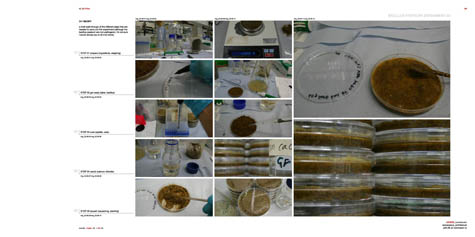

The following images show us the lab-based biochemical practices through which a landscape can be lithified. However, for me at least, these photos also come with the interesting implication that rogue basement chemists of the future won't be like Albert Hofmann or Ann & Alexander Shulgin; the heavily regulated underground rogue chemistry sets of the 21st century will instead synthesize new terrestrial compounds, counter-earths and other illegal geosimulants, rare earth anti-elements that might then catalyze a wholesale resurfacing of the world through radical landscape architecture.

Which leads me to ask: where is landscape architecture's Aleister Crowley, Madame Blavatsky, or even John Dee? Mystics of terrestrial form, hacking the periodic table of the elements inside makeshift labs.

[Images: Synthesizing rare earth compounds – bioterrestriality; from Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture]. [Images: Synthesizing rare earth compounds – bioterrestriality; from Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture].

In any case, Larsson's "solidified dunes," we read, would also "support the existing Green Wall Sahara initiative: 24 African countries coming together to plant a shelterbelt of trees right across the continent, from Mauritania in the west to Djibouti in the east, in order to mitigate against the encroaching desert."

[Images: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture]. [Images: From Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture].

Clearly having thought through the project in extraordinary detail, Larsson then points out that the structure itself would generate a "temperature difference between the interior of the solidified dunes and the exterior dune surface." This then "makes it possible to start building a permacultural network, the nodal points of which would support water harvesting and thermal comfort zones that can be inhabited."

[Image: The view from within; from Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture]. [Image: The view from within; from Magnus Larsson's Dune: Arenaceous Anti-Desertification Architecture].

Eventually, then, a 6000km-long wall of permaculturally active, inhabited architecture will span the Sahara.

Check out more images in this Flickr set for the project, or read a bit more about the project over at the Holcim Foundation.

-----

Via BLDBLOG

Personal comment:

Un de ces projets qui participent d'une nouvelle tendance d'"architecture-territoire" (et qui n'a pas forçément besoin de s'étaler à l'échelle du territoire, contrairement à ce projet).

Monday, April 20. 2009

[Image: Photo by Jonathan Brown. Brown reviewed the launch on his blog, Around Britain with a Paunch, writing that he and his friends "mingled in the mist, like shadows on the set of Hamlet"]. [Image: Photo by Jonathan Brown. Brown reviewed the launch on his blog, Around Britain with a Paunch, writing that he and his friends "mingled in the mist, like shadows on the set of Hamlet"].

Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley.

A former boutique storefront in London has become the temporary home for a pop-up bar with a twist: 2 Ganton Street is currently the U.K.'s "first walk in cocktail." Created by Bompas & Parr (known for their earlier experiments with glow-in-the-dark jello and scratch & sniff cinema), the "Alcoholic Architecture" bar features giant limes, over-sized straws, and most importantly, a gin-and-tonic mist.

Lucky ticket-holders (the event has now sold out) are equipped with plastic jumpsuits and encouraged to "breathe responsibly" before stepping into an alcoholic fog for up to 40 minutes – long enough to inhale "a fairly strong drink," according to Wired UK.

The Guardian noted that "as far as taste goes, this is the real deal," with some mouthfuls of air "sweeter with tonic and others nicely gin-heavy." Sam Bompas explained to Wired that they chose to vaporize gin and tonic (rather than, say, an appletini) because of its "nice smell, botanical flavours and freshness." St. John Ambulance volunteers are on hand, though the only reported casualties so far seem to have been hairstyles – victims of "gin-frizz". The Guardian concluded that, "With no sentient ice cubes able to confirm it, one can only assume that this is what the inside of a G and T feels like."

[Image: Antony Gormley's Blind Light, 2007, courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/White Cube, London, ©Stephen White]. [Image: Antony Gormley's Blind Light, 2007, courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/White Cube, London, ©Stephen White].

The project was inspired by Antony Gormley's Blind Light, a fog box installed at the Hayward Gallery in 2007. Bompas & Parr, who describe their world as operating in "the space between food and architecture," worked with the same company, JS Humidifiers, to adapt and install the ultrasonic humidifiers that create the thick, gin-based fog.

Though even typing "thick, gin-based fog" makes me feel a bit queasy, the experiment does seem to provide a perfect instantiation of London's social history, the city's prevailing damp, and its dense population. If the project is recreated elsewhere, perhaps local conditions will shape the installation: a freezing hail of neat vodka will form a layer of crystals on fur hoods and boots at a cavernous underground bar in Moscow; or a refreshing rum-and-coke mist will cool sunburned spring-breakers in the overcrowded hotel rooms of Daytona Beach.

[Image: JS Humidifiers]. [Image: JS Humidifiers].

Of course, the architectural manipulation of humidity is not limited to alcohol. As JS's website boasts: "For precise control of humidity and temperature, extreme outputs, specialist construction for controlled environments or unusual control, whatever the requirement JS will design and manufacture a solution." Existing clients for these bespoke humidification systems apparently include medical device manufacturing, offshore oil exploration, firearms production, specialist printing, pharmaceutical production and automotive manufacturing. It seems clear that custom atmosphere solutions are a product with endless applications: migrating from industry to art to retail, with the next step being high-end custom interior design for the very rich.

It can only be a matter of time before wealthy individuals are able to wake up to vaporized coffee, maintaining their multi-tasking edge by inhaling caffeine for that last half-hour of sleep, while the riders of Hollywood stars will routinely specify custom dressing rooms bathed in a fine mist of light-diffusing, age-defying elixirs.

[Earlier posts by Nicola Twilley include Park Stories, Park's Parks, Dark Sky Park and Zones of Exclusion].

-----

Via BLDBLOG

Personal comment:

Intéressant, mais à noter que Philippe Rahm avait déjà réalisé une installation similaire il y a quelques années au CCS de Paris, avec de l'absinthe.

En réalité cette installation fonctionnait comme une climatisation en puisant de l'air à l'extérieur qu'elle "nettoyait" à travers une solution d'eau et d'absinthe avant de l'injecter dans la pièce intérieure. Nom de l'installation: Absinth'Air.

Wednesday, April 08. 2009

[Dubai comes to Los Angeles / photo: Dan Hill]

I'm still trying to make sense of the whirlwind that was Postopolis! LA. The event provided the most wonderful kind of sensory overload and reveled in variety, contradiction and cognitive dissonance. Between jetlag, academic administration and a nasty fever I've been tied up since arriving back in Toronto late Sunday night but my mind still hasn't stopped racing. What follows is a personal highlight reel from the multitude of architects, interface designers, geographers, activists and vampire fiction/gentrification experts (!!) that presented during the first half of the event. I'll share my notes for the remainder of the proceedings sometime over the next several days.

fabric | ch / Atmospheric Relations / 2008

Fritz Haeg of Fritz Haeg Studio gave an overview of his landscape architecture, and park and garden design. Haeg highlighted his Gardenlab project and positioned garden design as a "counterpoint to the spectacle of architecture". Over the last several years Haeg has produced a series of Edible Estates that reconsider "green" space in both public and private contexts. Thus far eight prototype gardens have been developed in cities including Salina, Kansas, Los Angeles and London (as part of the Tate Modern's Global Cities exhibit in 2007).

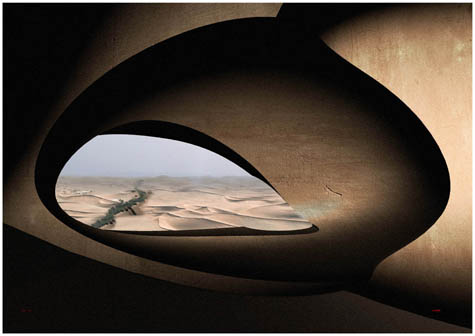

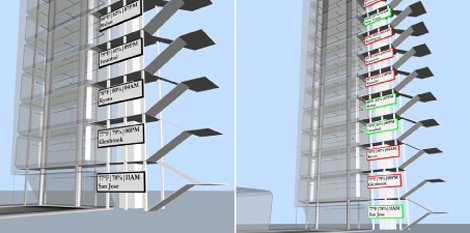

Patrick Keller of fabric | ch delivered a fascinating presentation on their work in developing and considering micro-climates. Fabric | ch describes itself as an "architecture, interaction & research" based practice and browsing their portfolio reveals some very exciting thinking (I'm definitely going to investigate and post about one of their earlier projects in the coming weeks). Keller discussed design projects such as their "informatic facade" for Atmospheric Relations and the interface for Philippe Rahm's Météorologie d'intérieur which was exhibited at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in 2006. A large portion of the presentation revolved around Real Rooms, a 2005 proposal that breaks down climates into discrete, modular units that play out across a larger "programmable" complex. Fabric | ch is an edgy, precise practice experimenting on archi-fundamentals (time, space) with very sophisticated considerations of the environment and information systems - exciting stuff! [See Dan Hill's detailed summary of this presentation]

Next up was Yo-Ichiro Hakomori of wHY Architecture who was interviewed by David Basulto and David Assael. This meandering conversation touched on a number of projects by the firm including the Grand Rapids Arts Museum and an Art Bridge. The latter project is an infrastructural intervention that provides pedestrian movement across the L.A. River while framing views of the water below and an expansive public mural. Midway through the discussion Hakomori mentioned that he considered Louis Kahn's Salk Institute one of his favourite project and this makes sense as wHY Architecture has developed a similar restrained monumentality.

The next session featured Dwayne Oyler and Jenny Wu of Oyler Collaborative, also fielding questions from Basulto and Assael. This experimental practice has executed some stunning installation work and the studio was commissioned by Ai Wei Wei to produce a residence as part of the Ordos 100 Villa project. As evidenced by projects like their 2008 Live Wire exhibit at SCI-Arc, it wasn't too surprising to learn that Oyler has collaborated with Lebbeus Woods in the past.

Daivd Gissen / Reconstruction - Smoke / 2006

Mary-Ann Ray of StudioWorks kicked off the second day of talks with a presentation on Chinese urbanism entitled "Towards Ruralpolitanism". Ray is working on an illustrated lexicon that indexes the intersection of massive Chinese cities with villages as there is no North American or European point of reference for understanding how cities and villages engage and interpenetrate one another in China. This research also extended into the cultural realm as Ray discussed a variety of principles pertaining to land ownership and management that roughly translated as "stir fried land" or "illegal mess" - she's trying to catalog these phenomena and engage them critically. Since there is no "suburbia" in Urban China, how do rural and urban systems respond to industrialism and agriculture? How does the population float back and forth between these urban typologies?

The next presenter was David Gissen of the excellent HTC Experiments blog. A historian and theorist at the California College of the Arts, Gissen expressed frustration with the gap between theory and and the practice of everyday life. He highlighted work such as Michael Caratzas' proposed preservation of the Cross-Bronx Expressways as being emblematic of ways that architectural historians might more directly engage the systemic nature of the city rather than just cordoning off specific buildings. Urban Ice Core - Indoor Air Archive, 2003-2008 is a "fantasy archive" in which Gissen proposed to collect and store indoor air for future analysis. Gissen closed his presentation with an utterly fascinating anecdote about his neighbour's parrot, and how it functioned as a mimetic device and imitated the ambient soundscape of the city - perhaps historians need to operate in a similar manner?

Robert Miles Kemp of Variate Labs presented a stellar body of work that blurred the lines between interface design, robotics and architecture. Kemp highlighted the impending fusion of physical and informational systems and identified an interest in thinking of software as "artifact" rather than control and robots as "systems" rather than anthropomorphic entities. Kemp showed a flurry of interfaces, dashboards and a homebrew multitouch display but what struck me the most was his 2006 thesis project Meta-morphic Architecture which proposed not just parametric design, but parametric space. Kemp maintains a research blog Spatial Robots - interactive systems fans take note.

Next up was an overview of Polar Intertia, the self described "journal of nomadic and popular culture" as edited by Ted Kane. Los Angeles is an idiosyncratic city full of storefront churches, mobile taco trucks, cell towers masquerading as palm trees and the like. Rather than homogenize discourse about the city (and urbanism in general) Kane parses the logic of these networks and phenomena. He presented an exciting overview of the politics of RV parked residences in Santa Monica and Venice and detailed how local legislation was creating a migrant population within these municipalities. Kane's journal looks quite exciting and I look forward to digging into it further.

The final presentation on Tuesday was Stephanie Smith of Ecoshack. Smith presented Wanna Start a Commune? which, by my reading, applies a veneer of revolutionary thinking and social activism from the 1960s (she identified The Diggers as a key influence) on top of a generic technology startup. The project aspires to monetize the toolkit required for microcommunity building, but I couldn't get past Smith's marketing rhetoric and ascertain a tangible position on what community was, let alone any kind of political stance. I wasn't at all surprised to learn she studied under Rem Koolhaas but her take on the intersection of capital, space and utopia seemed more crass than nuanced.

Stay tuned for my notes on the second half of Postpolis! LA. I'm also planning to provide some commentary on the organization and context of the event in relation to online media.

|

[Image: From Magnus Larsson's

[Image: From Magnus Larsson's  [Image: From Magnus Larsson's

[Image: From Magnus Larsson's  [Images: From Magnus Larsson's

[Images: From Magnus Larsson's  [Image: From Magnus Larsson's

[Image: From Magnus Larsson's

[Images: From Magnus Larsson's

[Images: From Magnus Larsson's  [Image: A photomicrograph of sand grains].

[Image: A photomicrograph of sand grains]. [Images: From Magnus Larsson's

[Images: From Magnus Larsson's  [Image: From Magnus Larsson's

[Image: From Magnus Larsson's

[Images: Synthesizing rare earth compounds – bioterrestriality; from Magnus Larsson's

[Images: Synthesizing rare earth compounds – bioterrestriality; from Magnus Larsson's

[Images: From Magnus Larsson's

[Images: From Magnus Larsson's  [Image: The view from within; from Magnus Larsson's

[Image: The view from within; from Magnus Larsson's  [Image: Photo by Jonathan Brown. Brown reviewed the launch on his blog,

[Image: Photo by Jonathan Brown. Brown reviewed the launch on his blog,  [Image: Antony Gormley's Blind Light, 2007, courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/

[Image: Antony Gormley's Blind Light, 2007, courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/ [Image:

[Image: