When New York City announced a plan to shut down parts of Times Square to traffic, New Yorkers’ reactions ranged from bemusement to mild hysteria.Despite reassurances from the Transportation Department that the changes would create a greener, more pedestrian-friendly city, some critics of the plan worried that it would sap the square of its chaotic energy. Others, apparently nostalgic for the seediness of the 1970s version of the square, denounced it as another step in New York’s transformation from the world’s greatest metropolis to a generic tourist trap.

Well, I’m happy to report that, a day after the stretch of Broadway between 42nd and 47th Streets was closed to cars, the soul of Times Square remains intact. The neon still sparkles. Tourists still wander around bewildered. The whiff of last night’s junk food still hangs in the air.

Nor is the new pedestrian mall a cataclysmic shift in New York’s identity. Cities as diverse as London, Copenhagen and Melbourne have managed to reduce the number of cars in the city center without losing their urban character. And part of Times Square’s value, from the days of its notoriety as a porn haven to the Walt Disney Company’s takeover of 42nd Street, has been as a kind of instant snapshot of how the city sees itself. Its next incarnation will have as much to do with broad economic and social changes that New York is undergoing as with a few planters and chairs.

But I worry about the character of the mall, with its string of disconnected plazas. While Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg has said the plazas are a work in progress — he will decide in December whether to transform them into something more permanent — they feel like odd leftover spaces. Until the city commissions a plan for a more detailed design, we won’t know what they will become.

The new five-block-long mall is the largest of a series of such spaces that now stretch from the Theater District down to Herald Square and Madison Square Park. Conceived by the city’s transportation commissioner, Janette Sadik-Khan, the plan is partly inspired by the redevelopment of downtown Copenhagen, many of whose medieval streets and plazas have been closed off to cars in the past decade.

Since becoming commissioner two years ago Ms. Sadik-Khan has also created some 200 miles of new bike paths throughout the city. A year ago she closed down traffic lanes between 42nd Street and Herald Square to create a series of public esplanades. This weekend she also closed off parts of Herald Square between 33rd and 35th streets to cars.

So far the pedestrian mall in Times Square is marked by little more than a few wobbly tables and metal chairs. A row of orange barriers frames the mall’s northern edge, where a half-dozen police officers patiently redirect traffic heading down Broadway. Workers have scattered a few potted plants across the street’s asphalt surface. (Seventh Avenue, which intersects Broadway at 45th Street, remains open to traffic.)

A large part of the design’s success stems from the altered relationship between the pedestrian and the structures that frame the square. Walking down the cramped, narrow sidewalks, a visitor could never get a feel for the vastness of the place. Now, standing in the middle of Broadway, you have the sense of being in a big public room, the towering billboards and digital screens pressing in on all sides.

This adds to the intimacy of the plaza itself, which, however undefined, can now function as a genuine social space: people can mill around, ogle one another and gaze up at the city around them without the fear of being caught under the wheels of a cab.

(As someone who has worked on and off near Times Square for decades, elbowing my way through the lunch hour crowds, I also appreciate the extra breathing room.)

Still, this is not the Piazza San Marco in Venice or even Trafalgar Square in London. A number of streets still cut across the square, carving it up into odd parcels of uneven sizes. The one between 45th and 47th Streets forms a generously scaled triangle at the northern end of the site. But as you travel farther south, the spaces become more awkwardly defined. A rectangular block between 42nd and 43rd Streets feels detached from the larger open areas to the north. The narrow esplanades below 42nd Street, which were created last year, are more or less lifeless.

Then there is the quality of the spaces themselves. The tables and chairs may work as temporary placeholders, but they are weirdly out of scale with their surroundings. They would make more sense in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris than in a busy intersection in the heart of a modern metropolis.

If the city decides to keep the plazas, it will have to design the spaces in a way that genuinely reflects the urban toughness of the city that feeds into them. It can’t simply recreate an image of a medieval European park. Or a mall in Southern California.

Will it work? The transformation of Copenhagen took decades, not years. And it involved constant tinkering. Some streets were closed to cars, then partially reopened years later. Parking in the city center was reduced slowly, over many years, so the changes were barely noticed.

As Jan Gehl, who worked on the Copenhagen plan and advised Ms. Sadik-Khan in New York, explained, the strategy allowed for a period of psychological adjustment.

Ms. Sadik-Khan seems to be working at a much faster pace. At times the process here seems clumsier.

She’s also working in a more impatient, less forgiving environment. What’s most encouraging about her vision is that it reasserts the positive role government can play in shaping the public realm after decades of sitting by and watching private interests take over. Now she has to prove that she can be as nimble in her design choices as she is at imposing her ideas on a skeptical city.

-----

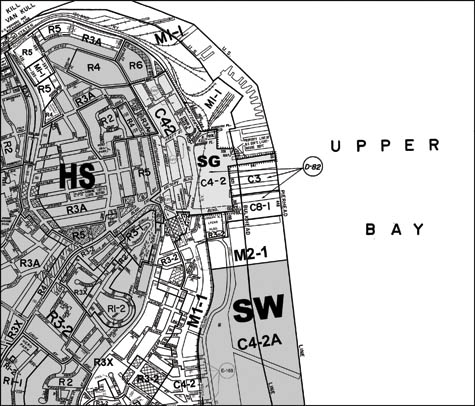

[Image: Detail of a zoning map for

[Image: Detail of a zoning map for  [Image: A Tribute to Sir Christopher Wren (1838) by

[Image: A Tribute to Sir Christopher Wren (1838) by

[Image: The Professor's Dream (1848) by Charles Robert Cockerell, courtesy of the

[Image: The Professor's Dream (1848) by Charles Robert Cockerell, courtesy of the

[Images: The Professor's Dream (1848), and several details thereof, by Charles Robert Cockerell, courtesy of the

[Images: The Professor's Dream (1848), and several details thereof, by Charles Robert Cockerell, courtesy of the