Monday, April 04. 2011

Via Lift via Contemporary Spaces

-----

When one of the world's prominent thinker about global thinking takes a look at "smart cities", the result differs from what most of the Industry tends to say - and that's why we like it:

"I have long thought that all the major infrastructures in a city—from sewage to electricity and broadband—should be encased in transparent walls and floors at certain crossroads, such as bus stops or public squares. If you can actually see it all, you can get engaged. Today, when walls are pregnant with software, why not make this visible? (...) The challenge for intelligent cities is to urbanize the technologies they deploy, to make them responsive and available to the people whose lives they affect. Today, the tendency is to make them invisible, hiding them beneath platforms or behind walls—hence putting them in command rather than in dialogue with users. One effect will be to reduce the possibility that intelligent cities can promote open-source urbanism, and that is a pity. It will cut their lives short. They will become obsolete sooner. Urbanizing these intelligent cities would help them live longer because they would be open systems, subject to ongoing changes and innovations. After all, that ability to adapt is how our good old cities have outlived the rise and fall of kingdoms, republics, and corporations."

Cities are the places where Lift France '11's five key topics (OPEN, CARE, GREEN, LEARN, SLOW) will congregate. We're therefore especially happy that Saskia Sassen has agreed to give the opening speech.

Thursday, March 31. 2011

Via BLGDBLOG

-----

by noreply@blogger.com (Geoff Manaugh)

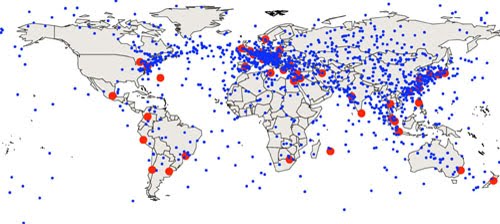

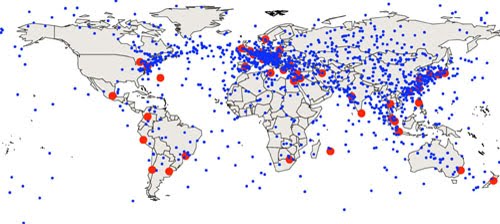

A recent paper published in the Physical Review has some astonishing suggestions for the geographic future of financial markets. Its authors, Alexander Wissner-Grossl and Cameron Freer, discuss the spatial implications of speed-of-light trading. Trades now occur so rapidly, they explain, and in such fantastic quantity, that the speed of light itself presents limits to the efficiency of global computerized trading networks.

These limits are described as "light propagation delays."

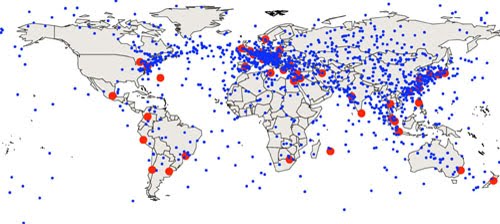

[Image: Global map of "optimal intermediate locations between trading centers," based on the earth's geometry and the speed of light, by Alexander Wissner-Grossl and Cameron Freer]. [Image: Global map of "optimal intermediate locations between trading centers," based on the earth's geometry and the speed of light, by Alexander Wissner-Grossl and Cameron Freer].

It is thus in traders' direct financial interest, they suggest, to install themselves at specific points on the Earth's surface—a kind of light-speed financial acupuncture—to take advantage both of the planet's geometry and of the networks along which trades are ordered and filled. They conclude that "the construction of relativistic statistical arbitrage trading nodes across the Earth’s surface" is thus economically justified, if not required.

Amazingly, their analysis—seen in the map, above—suggests that many of these financially strategic points are actually out in the middle of nowhere: hundreds of miles offshore in the Indian Ocean, for instance, on the shores of Antarctica, and scattered throughout the South Pacific (though, of course, most of Europe, Japan, and the U.S. Bos-Wash corridor also make the cut).

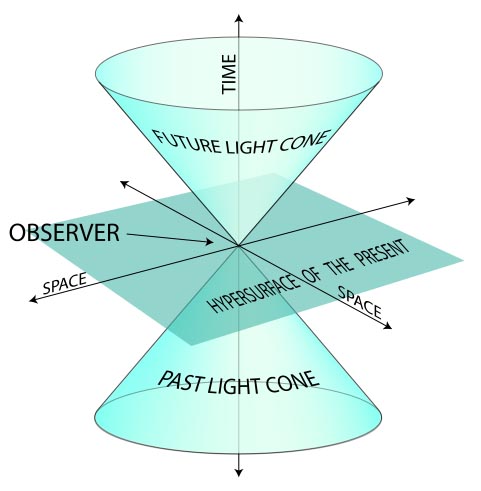

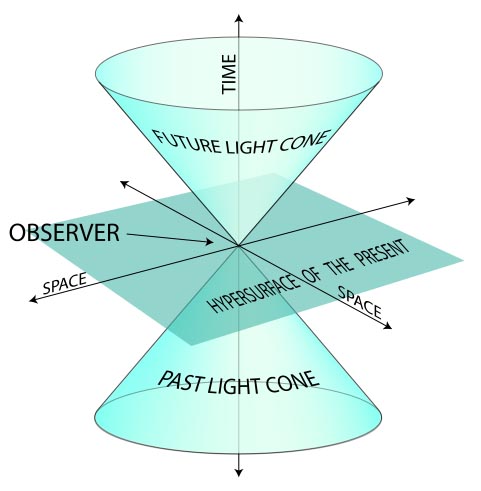

These nodes exist in what the authors refer to as "the past light cones" of distant trading centers—thus the paper's multiple references to relativity. Astonishingly, this thus seems to elide financial trading networks with the laws of physics, implying the eventual emergence of what we might call quantum financial products. Quantum derivatives! (This also seems to push us ever closer to the artificially intelligent financial instruments described in Charles Stross's novel Accelerando). Erwin Schrödinger meets the Dow.

It's financial science fiction: when the dollar value of a given product depends on its position in a planet's light-cone.

[Image: Diagrammatic explanation of a "light cone," courtesy of Wikipedia]. [Image: Diagrammatic explanation of a "light cone," courtesy of Wikipedia].

These points scattered along the earth's surface are described as "optimal intermediate locations between trading centers," each site "maximiz[ing] profit potential in a locally auditable manner."

Wissner-Grossl and Freer then suggest that trading centers themselves could be moved to these nodal points: "we show that if such intermediate coordination nodes are themselves promoted to trading centers that can utilize local information, a novel econophysical effect arises wherein the propagation of security pricing information through a chain of such nodes is effectively slowed or stopped." An econophysical effect.

In the end, then, they more or less explicitly argue for the economic viability of building artificial islands and inhabitable seasteads—i.e. the "construction of relativistic statistical arbitrage trading nodes"—out in the middle of the ocean somewhere as a way to profit from speed-of-light trades. Imagine, for a moment, the New York Stock Exchange moving out into the mid-Atlantic, somewhere near the Azores, onto a series of New Babylon-like platforms, run not by human traders but by Watson-esque artificially intelligent supercomputers housed in waterproof tombs, all calculating money at the speed of light.

[Image: An otherwise unrelated image from NOAA featuring a geodetic satellite triangulation network]. [Image: An otherwise unrelated image from NOAA featuring a geodetic satellite triangulation network].

"In summary," the authors write, "we have demonstrated that light propagation delays present new opportunities for statistical arbitrage at the planetary scale, and have calculated a representative map of locations from which to coordinate such relativistic statistical arbitrage among the world’s major securities exchanges. We furthermore have shown that for chains of trading centers along geodesics, the propagation of tradable information is effectively slowed or stopped by such arbitrage."

Historically, technologies for transportation and communication have resulted in the consolidation of financial markets. For example, in the nineteenth century, more than 200 stock exchanges were formed in the United States, but most were eliminated as the telegraph spread. The growth of electronic markets has led to further consolidation in recent years. Although there are advantages to centralization for many types of transactions, we have described a type of arbitrage that is just beginning to become relevant, and for which the trend is, surprisingly, in the direction of decentralization. In fact, our calculations suggest that this type of arbitrage may already be technologically feasible for the most distant pairs of exchanges, and may soon be feasible at the fastest relevant time scales for closer pairs.

Our results are both scientifically relevant because they identify an econophysical mechanism by which the propagation of tradable information can be slowed or stopped, and technologically significant, because they motivate the construction of relativistic statistical arbitrage trading nodes across the Earth’s surface.

For more, read the original paper: PDF.

(Thanks to Nicola Twilley for the tip!)

Wednesday, March 16. 2011

Via BLDGBLOG

-----

by noreply@blogger.com (Geoff Manaugh)

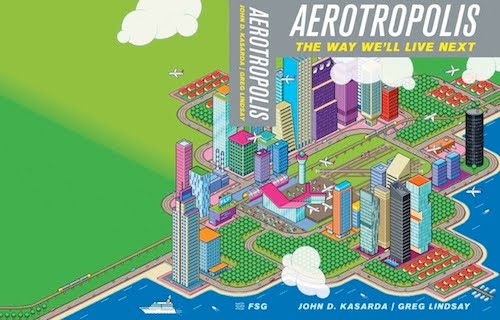

In his book London Orbital, Iain Sinclair writes that Heathrow Airport—with its "inscrutable geometry," surrounded by "international hotels, storage facilities, [and] semi-private roads"—is utterly "detached from the shabby entropy" of London. Indeed, "Heathrow is its own city, a Vatican of the western suburbs."

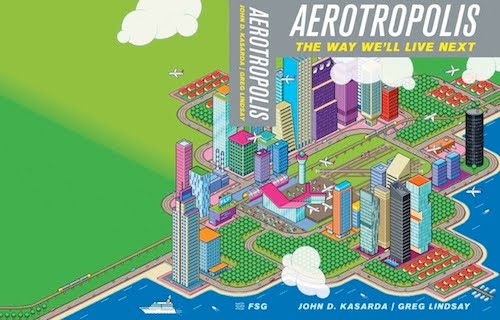

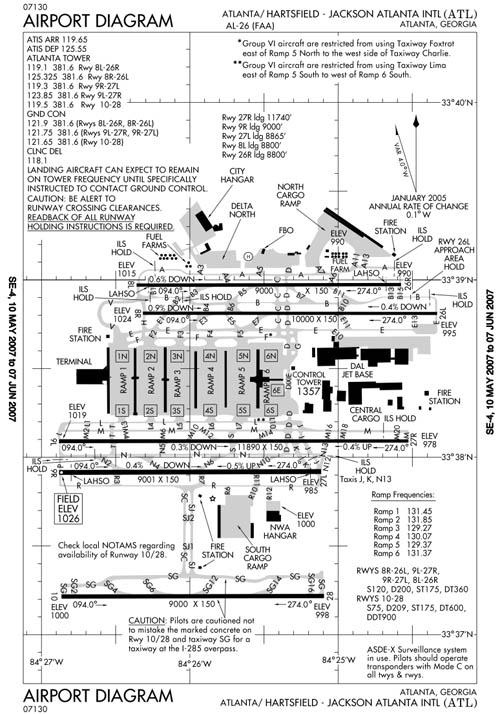

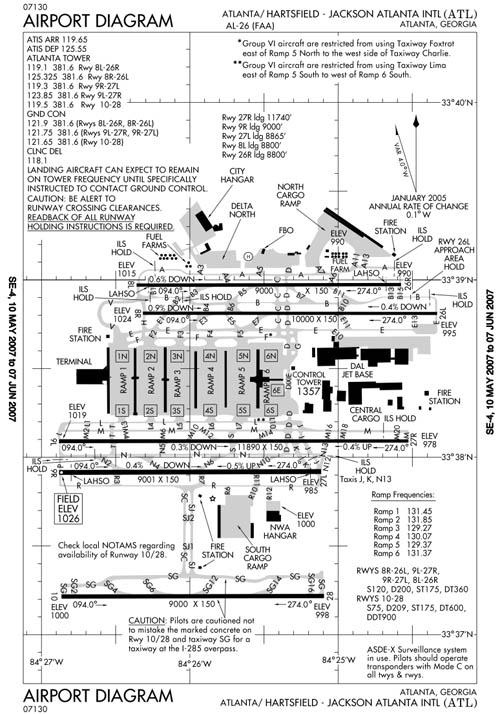

If Atlanta's Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport were to become its own country, its annual workforce and user base would make it "the twelfth most populous nation on Earth," as John Kasarda and Greg Lindsey explain in Aerotropolis; even today, it is the largest employer in the state of Georgia. If Atlanta's Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport were to become its own country, its annual workforce and user base would make it "the twelfth most populous nation on Earth," as John Kasarda and Greg Lindsey explain in Aerotropolis; even today, it is the largest employer in the state of Georgia.

As J.G. Ballard once wrote, and as is quoted on the frontispiece of Aerotropolis:

I suspect that the airport will be the true city of the 21st century. The great airports are already the suburbs of an invisible world capital, a virtual metropolis whose fauborgs are named Heathrow, Kennedy, Charles de Gaulle, Nagoya, a centripetal city whose population forever circles its notional center, and will never need to gain access to its dark heart.

The remarkable claims of John Kasarda's and Greg Lindsay's new book are made evident by its subtitle: the aerotropolis, or airport-city, is nothing less than "the way we'll live next." It is a new kind of human settlement, they suggest, one that "represents the logic of globalization made flesh in the form of cities." Through a kind of spatial transubstantiation, the aerotropolis turns abstract economic flows—disembodied currents of raw capital—into the shining city form of tomorrow.

The world of the aerotropolis is a world of instant cities—urbanization-on-demand—where nations like China and Saudi Arabia can simply "roll out cities" one after the other. "Each will be built faster, better, and more cheaply than the ones that came before," Aerotropolis suggests: whole cities created by the warehousing demands of international shipping firms. In fact, they are "cities that shipping and handling built," Lindsay and Kasarda quip—urbanism in the age of Amazon Prime.

The world of the aerotropolis, then, is a world where "a metropolitan area's position in the airline network determine[s] its employment growth and not, as commonly supposed, the other way around." Or, as a representative from FedEx explains to Greg Lindsay, "Not every great city will be an aerotropolis, but those cities which are an aerotropolis will be great ones."

Surely, though, this kind of breathless rhetoric is a reliable sign of hype. What are the real political and economic conditions of the aerotropolis; what transformations might it undergo in an age of peak oil and climate change; and who, in the end, will actually live there and manage it? This latter question seems particularly urgent: does the aerotropolis represent the culmination of the city's slow depoliticization—an urban form without mayors or democracy—run instead by a managerial class of logistics professionals and CFOs?

Or do these very questions reveal a misconception about what the aerotropolis is and will be?

[Image: A plan of Atlanta's Hartsfield-Jackson Airport, via Wikipedia]. [Image: A plan of Atlanta's Hartsfield-Jackson Airport, via Wikipedia].

To begin to answer these questions, and in preparation for a live interview that will take place in Los Angeles on Tuesday, April 5, at the A+D Museum, I spoke to Aerotropolis co-author Greg Lindsay about these and many other topics, from the aerotropolis itself to instant cities, the appeal of the urban realm for today's technology firms, and metropolitan futurism circa Le Corbusier. The resulting conversation, included below, shows Lindsay to be both frank and refreshingly candid about the book. He is also someone clearly excited to talk about the future of the city, aerotropolis or not: simply to transcribe this interview, I had to slow the audio file down to nearly 85% of its original speed just to unpack Lindsay's jet stream of ideas and references.

Consider this a teaser, then, for the event on April 5. Until that time, pick up a copy of Kasarda's and Lindsay's book to see what you think; and, if you get a chance, take a look at the second half of this conversation, during which the tables are turned and Lindsay interviews me for Work in Progress, the newsletter of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. There, we discuss the role of the architect in a world of smart cities and instant urbanism, the fate of criticism in the context of architecture blogs, and where we might turn next for tomorrow's spatial ideas.

• • •

BLDGBLOG: Let’s start with the most basic question of all: what is an aerotropolis?

Greg Lindsay: John Kasarda, of the University of North Carolina, came up with the idea twenty years ago—though, in researching the book, I found that word’s original appearance in print was actually in Rem Koolhaas’s Great Leap Forward, quoting a local Chinese official. Kasarda first heard it in China, as well.

In terms of vision, I think there are really two definitions of it, depending on which of the two authors you speak to—Kasarda or myself.

Kasarda’s notion of an aerotropolis is basically a city or a region planned around an airport. In his mind’s eye, everything is spatially divided by usage: hangars, cargo terminals, office parks, business hotels, six-lane highways, merchandise marts. There’s no real urban form at all. On one level, it’s like Edge City: the form is dictated by development money and the respective need for access to the airport at the center. But, on another, the design is glossed over or left out. In models and renderings, they never achieve a resolution above little white boxes.

He sees the aerotropolis purely in terms of time/cost equations. Density and design is secondary. A layperson would describe it as sprawl. It’s an urban vision without any real urbanity.

Then there’s my definition of it—and I think I take a broader view. I would describe the aerotropolis as any city that has a closer relationship to the air, and to other cities accessible through the air, than to its immediate hinterlands. It’s a city that was basically invented because of the necessities of air travel.

Dubai, to me, is a perfect example of that. Thirty years ago, of course, there was nothing there; Dubai had little oil and even fewer people. But, basically through sheer will, it used its airport and its airline, Emirates, to build itself into a hub. It transformed itself legally and regulatory-wise, and made itself the freezone of the Middle East—and the pleasure den, and all the things it’s become.

Dubai’s also interesting because it illustrates the grander vision of the book, which is that transportation always defines the shape and look of cities. Joel Garreau made this point twenty years ago, that cities are defined by the state of the art of transportation at the time. I think many of the cities we love today are classic railroad cities—such as New York, built around Grand Central Station, and Chicago, where the first skyscrapers sprang up across the street from the Illinois Central’s railyard.

But the idea now is: if you’re building a city from scratch in the middle of China or India, then you’re building it around an airport. The airport is the city’s economic reason for being. You’re trying to connect to a global economy, starting from zero.

Dubai is interesting in that regard. Nobody really understood what Dubai was about, or what they were trying to do there, but its plans make sense if you look at it from the perspective that there’s this theoretical population all dispersed across the Middle East and southeast Asia, and they’re all flying in to use the city in bits at a time.

The notion of the aerotropolis, then, is basically that air travel is what globalization looks like in urban form. It is about flows of people and goods and capital, and it implies that to be connected to a city on the far side of the world matters more than to be connected to your immediate region. The aerotropolis spatializes what people like Saskia Sassen have been writing about for twenty years in books like The Global City.

[Images: Dubai International Airport promotional images; vertical distortion is in the originals. Courtesy of the Dubai International Airport Media Center].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Dubai International Airport promotional images; vertical distortion is in the originals. Courtesy of the Dubai International Airport Media Center].

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious about the political requirements for making an aerotropolis happen. On the level of regulation, zoning, and so on, what needs to occur for an aerotropolis to become realizable?

Lindsay: Well, I always say that we built our airports in the United States before we knew what they were for. We didn’t really understand the scale of future operations or the geographic footprint they would need, so we built them within footprints that were never going to be sustainable for the levels of traffic they would ultimately absorb.

So we ended up with places like LAX. One of the things I love noting is that, when LAX was first built, it was criticized because the field was seen as too far from downtown—whereas, today, you have an airport that’s basically landlocked on all sides, and has been for almost fifty years. This puts LAX and Los Angeles in an intractable situation, considering the economics of air travel, which require concentration for hubbing, for operational efficiency, for all of that. It’s in the best interests of an airline to concentrate in one place—and LAX is a place that just cannot expand.

The next stage is understanding the scale you need to operate on: you need to plan for a larger region. We talk about regional planning in the United States, but we do so little of it. We hardly even understand how economies cross what are almost arbitrary borders at this point, between counties and cities. I had difficulty finding reliable gross metropolitan product numbers, and Richard Florida had to go so far as to measure light pollution from space in one of his books.

In Los Angeles, because of the failure of Orange County to build a second airport, if you’re going to fly internationally, and if you’re basically anywhere from Malibu to the Mexico border, you’re going to pass through LAX—which is a hell of a catchment area and an incredible strain to put on one airport. That’s partly due to when Orange County tried to build an airport at the former El Toro Marine base and ended up in a bizarre civil war: you had the right-leaning NIMBY interests on the side of the environmentalists, and you had the Chamber of Commerce siding with the poor immigrants of Orange County, because they wanted the jobs. It made for this schizoid conflict.

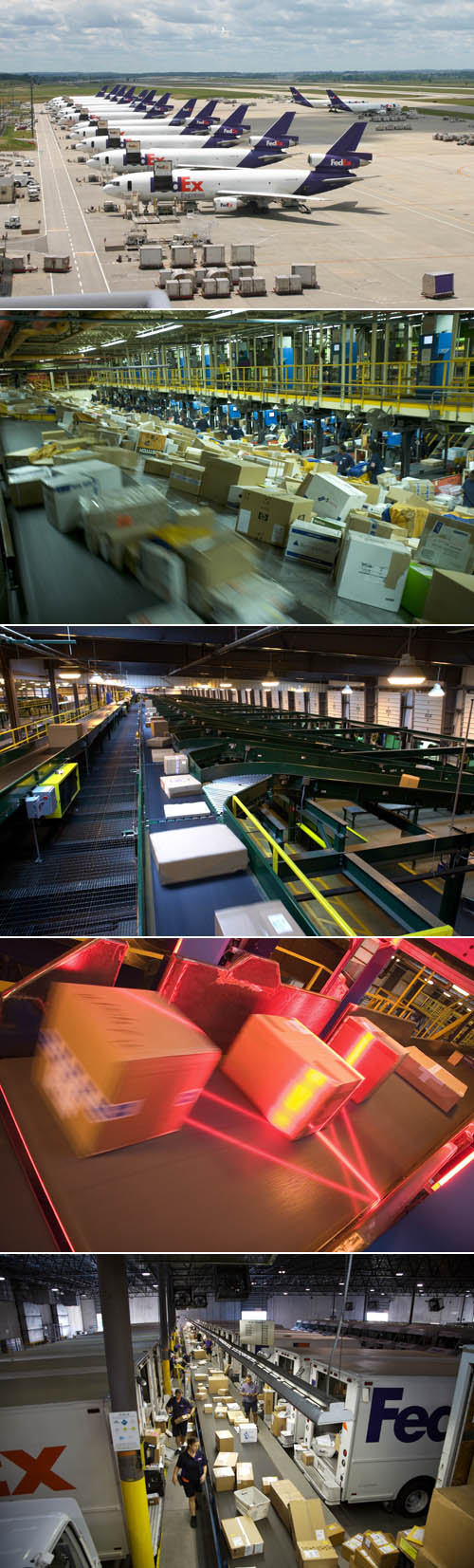

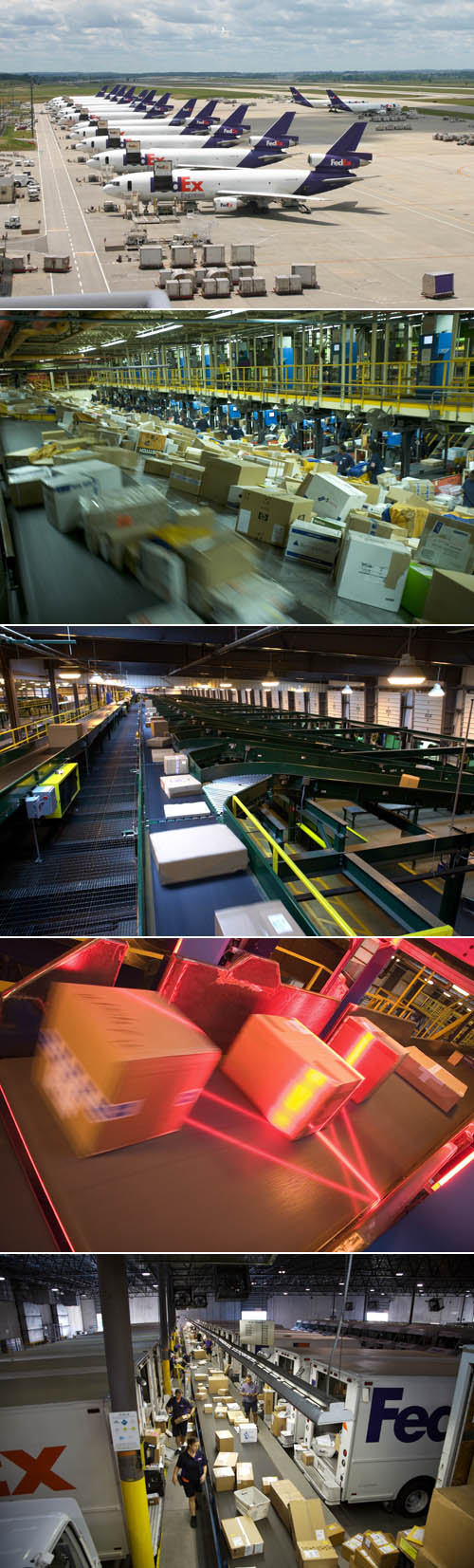

To continue from a narrow American perspective, I think the examples of Memphis and Louisville are fascinating, where the sheer economic force of FedEx and UPS basically willed them into being.

Those cities used to be river-trading towns—cotton and tobacco, respectively—before they became basically southern rustbelt towns. But then, in the 1970s and 80s, they were reborn as company towns of FedEx and UPS. In a sense, their economics—for better or for worse, and that’s very much up for debate—are held hostage by our e-commerce habits: every time we press the one-click button on Amazon, it leads to this gigantic logistical mechanism which, in turn, has led to the creation of vast warehouse districts around the airports of these two cities.

One of the things I tried to touch on in the book is that even actions we think of as primarily virtual lead to the creation of gigantic physical systems and superstructures without us even knowing it.

[Images: Laser-guided FedEx hub urbanism at work; all images courtesy of FedEx. Meanwhile, it is about UPS—not FedEx—but John McPhee's essay "Out in the Sort" is a minor classic in what I might call the logistical humanities].

BLDGBLOG [Images: Laser-guided FedEx hub urbanism at work; all images courtesy of FedEx. Meanwhile, it is about UPS—not FedEx—but John McPhee's essay "Out in the Sort" is a minor classic in what I might call the logistical humanities].

BLDGBLOG: In this context, you point out in the book that Kasarda “proposes building cities by corporations for corporations, guaranteeing their survival by tailoring them to clients’ specifications—beginning with the airport.” The city is not an expression of human culture, so to speak, but a kind of 3-dimensional graph of economic activity.

Lindsay: Yes, the aerotropolis—as Kasarda preaches it and as has been implemented in places like Dubai and elsewhere—is less about urbanity than repurposing the city as a “machine for living,” to quote Le Corbusier.

The aerotropolis is basically an economic engine. Planners are looking for ways to make these cities as frictionless as possible in terms of doing business—which means that, in places like Dubai, the tax-free zones and enclaves such as Dubai Media City and Dubai Internet City and the Jebel Ali Free Zone can basically wage an economic war of all against all when it comes to competing cities. They were designed as weapons for fighting trade wars, and their charter—to be duty-free and hyper-efficient—reflects this. So it’s interesting in the sense that these cities are infrastructure-as-weaponry, which Rem Koolhaas wrote about in “The Generic City” [ PDF]—“City X builds an airport to kill City Y.” They’re competing rather than complementing.

China’s cities, in particular, are building infrastructure not as a way to improve urban living across these larger regions, but basically so that they can do battle against one another for attention and investment.

BLDGBLOG: Sticking with Dubai, at one point you write: “High-functioning dictatorships such as Dubai’s don’t faze [Kasarda]. If anything, they’re the only ones who move fast enough.” This sounds quite ominous. In some ways, I’m reminded of recent architectural debates in which people seemed to side either with a revival of Jane Jacobs or with a revival of Robert Moses—where the latter camp claims that what we really need now is a kind of infrastructural dictator, someone who will get the job done, whether that’s high-speed rail or a new tunnel between New Jersey and Manhattan. But what are the political implications of the aerotropolis—and is a “high-functioning dictatorship” really the most appropriate form of government for such a city?

Lindsay: Well, it’s obvious if you look at the projects under way that a great many of them are being realized by authoritarian governments, whether that’s China or the Middle East monarchies.

Basically, the aerotropolis, or any kind of instant city project, seems to be enabled by autocracy. That’s the case whether you’re building an aerotropolis in Dubai or whether you’re building one in Beijing, or whether you’re building smart cities in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia is building six “economic cities,” quote-unquote, which will double as aerotropoli. The Saudis are trying to revamp their whole air system, develop their national airline, and then also make these smart cites into job magnets, thinking that they could basically build a society from scratch.

It’s funny that you’d mention Robert Moses, though, because I didn’t even really think of him in the context of this book. It’s gone beyond the scale of Moses. Moses was a regional planner operating in what is ultimately a democratic government. But you have planners—in fact, you have technocrats—who are commissioning and building whole cities now. I think Robert Moses would be a fantastic figure today—because he would be a vast improvement over some of the secret decisions being made in China over what they’re going to build, where, and to what end.

This goes back to what I was saying about the war between cities. I was reading a description by Steven Cheung, a Chicago School economist who taught in Hong Kong. He presented a paper in Beijing in 2008 that was partially translated in Richard McGregor’s The Party, where he discusses the economic model that has driven China. His notion is that every city there is at total war with each other economically, in order to attract foreign investment. They’ll promise you everything, and they’ll move as fast as possible, and they’ll build whatever you need to make it happen. And that’s the same impulse behind the people who are building aerotropoli. You end up with a city like Chongqing, with 32 million people, where they’re building a massive new airport that will create hundreds of thousands of new jobs for the millions of people who were displaced by the Three Gorges Dam.

On some level, I think in America we don’t even understand the level and the pace of change that is happening in China, where, because of decisions made by central planners, millions of people are being urbanized—literally at the flip of a switch, because they’re simply changing their legal status from “rural” to “urban.” Suddenly, three million farmers turn into three million urbanites, and now you have to find jobs for them, and situate them, and do all these things.

For an autocrat, it’s easy to will that into existence—and the pleasures of doing so are well known. I mean, Thomas Friedman in Hot, Flat, and Crowded has a whole section on “if only we could be China just for one day…”

In terms of the aerotropolis, maybe the most interesting developments will be in India. They intend to build, I don’t know, a hundred airports from scratch, and they are actively planning a few in the mold of Kasarda’s aerotropoli. And considering India is a democracy, it’s led to some massive political battles. They’re fighting over the land; they’re fighting over whether to build one above coalfields. It will be very interesting to see at what rapidity they can move forward with a true democratic process.

But I think the classic example in the book is in Thailand, where Kasarda has been a teacher and government advisor for years and where he sold his vision of the aerotropolis to Thaksin Shinawatra—who was then the elected prime minister but was almost universally considered an oligarch. People who were involved in that process are still unsure that Thaksin ever understood what Kasarda was trying to tell him, or whether Thaksin simply saw it as a land grab—a way to install his own family members in development companies and reap huge profits from it.

The flipside is Dubai. They screwed up a lot of things there but, through several generations of rulers now, they’ve understood that investing in infrastructure and investing in trade was the key to long-term success.

[Image: The now-erased runways of Denver's old Stapleton Airport; the airfield has since become a New Urbanist residential development. Photo courtesy of the Colorado Department of Transportation].

BLDGBLOG [Image: The now-erased runways of Denver's old Stapleton Airport; the airfield has since become a New Urbanist residential development. Photo courtesy of the Colorado Department of Transportation].

BLDGBLOG: A few times now, you’ve mentioned the prospect of a failed aerotropolis—or at least an aerotropolis that is incorrectly implemented. I’m really curious about that—about what might happen to an aerotropolis if the growth of air freight and business travel doesn’t actually pan out as expected. In the book, you do touch on things like climate change and peak oil—but is it short-sighted, in a way, to build cities specifically around one form of transportation, one that might someday prove inaccessible?

Lindsay: In terms of building a city around an airport, there’s a common misconception that we’ll be building homes right up to the fence of the airport. But the airports we build today are massive, and they have huge noise buffers around them, which isn’t the case at older airports. Denver’s old Stapleton Airport is a classic example of this, where people actually did live a couple hundred yards away from the runways, with all of the piercing noise. But when they built the new Denver International out beyond the city, it’s two miles from the runway to the border of the airport, and it floats on this sea of grass that nothing can ever get close to—though developers are trying.

So, even though you’ll have fast access to the airport, it’s not like you’re going to look across the street and see planes landing. Then again, I live in brownstone Brooklyn under a flight path, eight miles from LaGuardia, and, on rainy nights, it sounds like planes are about to land on my desk. It’s all relative.

As for peak oil and climate change, I devoted a whole chapter to them in the book. I believe wholeheartedly in peak oil—you simply cannot geometrically increase consumption of a finite resource—but I do believe that biofuels, likely harvested from micro-organism production platforms, can produce sustainable, replenishable jet fuel. The science is sound; the scale of production is what’s in question.

But even if you think climate change is inescapable, or that peak oil will do us in first, and even if you think that aviation will go away and that globalization will stop, for good or for bad—but probably for good—to me, the question is: Are you willing to bet the future on that?

Because what’s interesting to me is that, in China, India, and the Middle East—and anywhere else in the developing world whose cities have been cut out of globalization so far—they’re building these cities to connect themselves to the global economy, in which they intend to participate, if not someday to dominate.

The more unsettling question that I wanted to raise in this book—rather than just cheerlead for airport cities, as some critics have accused me of doing—is ask whether we need to do the same to keep pace. Do we need to build or re-build our cities to more efficiently process goods and people? Or will these places collapse under their own weight?

In China, the answer may be both. But this is the world we made—one-click shopping creating giant hubs in Louisville and Memphis—and this the world they’re making. It may end in disaster, or it could lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty—and hurt our own economy further in the process.

These are questions I wanted to leave to the reader. The reasons autocracies are so eager to embrace an aerotropolis or an instant city is because they’re willing basically to throw money and people at the problem in an attempt to catch up to us in an incredibly rapid timeframe.

I was just reading the other day about Kangbashi, the “ ghost city” of Ordos, China. It was built in five years flat for a million people. It’s interesting to me that they’re willing to work at this speed in an attempt to catch up, even regardless of the consequences.

[Image: A rendering of New Songdo City, courtesy of Kohn Peterson Fox].

BLDGBLOG [Image: A rendering of New Songdo City, courtesy of Kohn Peterson Fox].

BLDGBLOG: I’d like to discuss the idea of the “instant city” more generally. It’s an evergreen vision, in many ways, and an ideologically promiscuous one, appealing both to the 1960s architectural avant-gardes and to the overseas forward-operating bases of military planners. In your own work, you’ve covered things like the “ City in a Box,” New Songdo City, and Russia’s “ silicon forest” where cities are basically treated as products that you can buy—like customizing a BMW off a website and then hitting the purchase button. Where is this sort of instant urbanism going, and who or what is driving it?

Lindsay: The thread I see going through the book and the work I’ve been doing for Fast Company is the notion that the people who are planning cities today, and who have really gotten interested in urbanism over the last few years, are people who are neither architects nor planners. The city is experiencing a white-hot moment, and this is converging from a bunch of different areas.

You have the whole camp coming out of Richard Florida’s work, for example, who have gone through the economic effects of cities and the cultural spillover of knowledge and training—basically, the notion that cities are engines of creativity and engines of ideas and job skills. Harvard’s Edward Glaeser is deservedly enjoying his moment in the sun for his academic work around these issues. To him, the key economic actor of the future is the city.

Then you have the technology companies who have been piling in, led by IBM. This is what really led to the resurrection of the “ smart city” a couple years ago, which is the notion that, coupled with the " internet of things"—assuming we reach a point of ubiquitous sensors and constant data flows—the city becomes the next computing paradigm. This has been discussed academically for decades, but now it might actually happen—or at least there’s a lot of money and corporate support behind it.

Then you get to the notion, again, of infrastructure—of Kasarda, of the aerotropolis, and of people who are building cities as competitive weapons.

Some of the most interesting things I like writing about are places like New Songdo City. Songdo is billed today as a smart, green aerotropolis, but it was invented by the Korean government at the insistence of the International Monetary Fund following the 1997-98 financial crisis, when the IMF bailed out Korea to the tune of $58 billion—which seems like nothing now. The IMF insisted the country open itself up to foreign direct investment. So its leaders decided to build a city for foreigners, and that led to finding an American— Stan Gale and his partners—to build a whole city from scratch off the coast of Korea. It was basically willed into existence by the necessity of paying back the IMF; that’s why Songdo was born.

Or there are the smart cities being planned. Masdar, for example, is supposed to be a smart eco-city. Masdar basically exists to be an incubator and an R&D park so that Abu Dhabi can dominate clean-tech technology. Again, this is basically the city as an economic weapon, not a utopian vision.

I find the people drawn to these projects equally fascinating. For example, Stan Gale is your classic story of American real-estate development. He’s a third-generation developer who got his own start in Orange County in the 1980s, and he witnessed the master planning and the financialization of real estate that began there; he then worked in New Jersey in the 1990s, where the market evolved into edge cities; and now here he is working at the global scale, trying to convince more Chinese mayors to help him build cities for them. He’s got a whole consortium of companies, like Cisco and United Technology Corporation—which, incidentally, builds more pieces of the city than I think anyone really knows. Otis Elevators, fuel-cells—all these things that you need for a project being built at the city scale.

Someone else I find equally fascinating is Paul Romer, the economist who’s pitching the idea of the charter city. I’d like to think he’ll win the Nobel Prize for the work he did in the 1990s on what’s been called New Growth theory, which described increasing returns to scale. Paul basically decided that the best way to raise people out of poverty—the best instrument—is to build a city from scratch and use it as a tool for developing skills, trade and everything else. And it appears that he’s actually now found a country willing to let him do it, in Honduras. This is a man who has absolutely no urban planning background. Urbanism to him is secondary—he cares, but he’ll leave it to the experts. The urbanism itself is not paramount to him.

It’s interesting to me that these outside elements—whether it’s a technology company or an economist or a developer—feel like the architecture and the urban planning is just—you know, we can get experts to do that for us. And it’ll be great. Architects like Kohn Peterson Fox, who are responsible for Songdo, rather than build a perfect city from scratch, basically borrow the best pieces of every city they can find to create a new city. And, you know, having been there a couple of times, I feel like it may actually work; I don’t know what the completed city will be like, but I feel like it’s working. Gale uses the phrase “city in a box,” which you mentioned, but they’re also saying things like “we’ve cracked the code of urbanism”—which is a hell of a statement to make. To think you’ve solved 9,000 years of urban practice and that you can just move on is quite dramatic.

So those are some of the things I find particularly interesting: that the city has become this nexus of interests for so many people, only it’s being made or stimulated by people who aren’t architects or urban planners.

[Image: Le Corbusier's infamous Plan Voisin, meant to replace the heart of Paris, France]. [Image: Le Corbusier's infamous Plan Voisin, meant to replace the heart of Paris, France].

BLDGBLOG: It’s easy to see how all this can sound quite technocratic and dystopian—which makes it all the more interesting that you open the book with an unexpected pair of quotations. One is from Le Corbusier, the other from novelist J.G. Ballard. To anyone familiar with Ballard’s work, in particular, I might say, this seems like a strangely subversive gesture against the book's own premise; it's like opening a golf course community and saying you were inspired by Super-Cannes. Why did you choose these quotations, and what effect were you hoping they would have?

Lindsay: I’m so glad you brought that up. I’ve been curious what people would make of it. What I love about Ballard is the kind of dark irony of his work, which is something I find in Koolhaas’s writing as well. They know the future is slick and disposable, and they revel in modernity’s contradictions. They know how dark globalization’s undercurrents are, but go on despite—or even because of—them. The book reviewers who said the aerotropolis had “forgotten” a soul completely missed the point—these cities never had souls to begin with. That’s why I find them fascinating!

The Ballard and Le Corbusier quotes should be read as a flashing red light, signaling to the reader: Caution: Unreliable Narrator Ahead. You’ve been warned. Especially that Le Corbusier quote: anyone who knows anything about urbanism who encounters that quote should immediately have their guard up—which was my intention all along.

• • •

Thanks again to Greg Lindsay for having this conversation—including the second half, which you can read over at Work in Progress—and to Stephen Weil for all his help in setting this up.

Finally, I hope to see some of you in Los Angeles at the A+D Museum on April 5th, when Greg Lindsay and I will pick up this conversation in person. The event is free and open to the public, and it kicks off at 6pm.

Wednesday, February 23. 2011

Via Mammoth

-----

by Stephen

Bridging the gap between mammoth’s interest in infrastructure, global logistics, economies, and really, really big things is this announcement from Moller-Maersk:

Danish shipper Moller-Maersk, the biggest container carrier, confirmed Monday it has signed a contract for a South Korean shipyard to build it 10 giant container ships over the next three years… The new container vessels, at 400 metres long, 59 metres wide and 73 metres tall, will be “the largest vessel of any type known to be in operation,” but emit half as much carbon dioxide as the industry average for Asia/Europe trade, the statement added.

Purchasing your own fleet of carriers will set you back $2bn.

[The Georg Maersk - 9074 TEU (twenty-foot equivalent units - typical shipping containers are forty feet long, meaning each count for 2 TEU). The new ships will be approximately 18,000 TEU.]

[Photos via Maersk, h/t to Telstar Logistic]

Thursday, February 17. 2011

Via Shrapnel Contemporary

-----

by pedrogadanho

A stranger in a strange place, you land on a snow-covered city and this suddenly feels as refreshing as being slapped without warning. Like sleep deprivation, you remember you need these abrupt changes to take you out of a lukewarm, pleasing state of hibernation. You feel privileged. You are part of an apparently disappearing sect: travelers of rare bliss, exchangers of precisely located, yet homeless knowledges – the yesteryear voyagers who have been slowly, but surely, substituted by passive tourists and predatory traders.

Anri Sala, Long Sorrow, 2005. Via Mousse Magazine.

Like if entering a proper nuit blanche, as soon as you arrive to the core of this city you find yourself visiting a contemporary art museum at 1.00 am – this hour still being your unquestionable biological time. And this museum is full of people, and you enjoyably rediscover the powerful work of Anri Sala, or come across artists like Young & Giroux. Mostly, you take in pieces that you’ve never seen before, and yet feel pleasantly close to home. A satisfying cultural acclimation, as it would be.

A few hours later, you will remember being in Tokyo on a reverse timetable. You will remember assaulting the streets for food at around 4.00 am, a harmless vampire looking out for the nearest 24/7. You will recall feeling sleepy at 7.00 pm and abandoning yourself to the same chronological cycle, over and over again. As it were, in this unexpected enclave of French language in America you find yourself reading Barthes between 4.00 and 8.00 am. You register the light coming in. Then you write. Just another way of getting lost – and found – in the delights of translation.

© Pedro Gadanho, “5.00 am (Hotel room with a view, #12)”, 2011

This one time you refuse to change the hour in you mobile phone. You stubbornly stick with your time zone. You will experience four days of a slightly dislocated timetable. As such, your panel conversation takes place at 11.00 pm, and by 1.30 am you are still discussing if and why architectural writing is undergoing a fictional turn. (A member of the audience suggests that maybe we are no longer interested in the truth. You counter that we may solely be bored or, even worse, giving in to the perverse logic that entertainment must take the lead in even pedagogical and disciplinary matters.) Dinner finishes at 5.00 am.

Two days after, you are still waking up at 4.00 am, local time. It is Saturday and four hours until breakfast. You make the usual morning skype call to your family. Then you head for Stereo, like a 12 year-old who skips Sunday school to join the after hours crowd. It turns out that Montreal has an interesting electronic scene and is twinned to your own city by a legendary sound system. And as they used to say, M.A.N.D.Y and Troy Pierce are in the house.

It’s a long time since you’ve been clubbing on your own. In this dance floor sunglasses after dark are obviously fashionable. A guy wears a T-shirt that says: “Egypt woke me up.” Did it really? Fortunately, at this stage social interaction is no longer required. As ever in the past, you are here exclusively for the acoustic engineering. As the sound involves you, your mind fills with words you will eventually write down. You reflect that bad techno is like any other form of porn, too lastingly engaged in some basic arrangement. Then again, the most layered electronica of post-Reich crop is the be-bop of our era.

Music is probably the clearest way to understand the fundamental play of novelty and obsolescence in our mental life. Novelty is an addiction. Even if it would be repetition that, as Barthes put it, “engendrerait elle-même la jouissance.” As architects like to believe in durability, they mostly reject novelty as a motor of their own doings. Nonetheless, architecture too is subject to rules of cultural consumption. And those dictate that we want our brain cells constantly rearranged by new arrangements of old and new fragments.

Three hours listening to music that you had never heard before and you are ready for the last, long day you will spend in town. The hypnotic beats have made you strangely apt to appreciate Buckminster Fuller’s Biosphere and Moshe Safdie’s still surprising Habitat 67 – even if you are walking from one to the other alone under a severe snow blizzard. The trance-like quality of those “rythmes obsessionels” have opened your mind to the Mile End’s graphic novel stores and the weird and wonderful ephemera shops of Boulevard St. Laurent – even if you are long past your regular dinnertime.

© Pedro Gadanho, “Ruins of the Future (Habitat 67)”, 2011

The morning you leave town you are woken up by the alarm clock at 5.30 am. Local time is catching up with your body. It is forcing you to conform. You timely escape into the airport. By 10.00 am you are in New York. One of those places, if not the place, which crisply illuminates how precious it is to breathe the air of the city. A few hours are enough.

Just before you definitely head home, five hours is what it takes to once again verify how a city can remain itself and yet retain an ever-unbelievable degree of new stimuli. Indeed, what Georg Simmel has once dubbed the mental life of the metropolis here translates in the peculiar feeling that the spur of the new it too can be enduringly inscribed into the flesh of stones.

Monday, January 31. 2011

Via BLDGBLOG

-----

by noreply@blogger.com (Geoff Manaugh)

[Image: Courtesy of Terremark, via the Atlantic]. [Image: Courtesy of Terremark, via the Atlantic].

Andrew Blum has a short piece up at the Atlantic today about the geography of "internet choke points," and the threat of a "kill switch" that would allow countries (like Egypt) to turn off the internet on a national scale.

After all, Blum writes, "it's worth remembering that the Internet is a physical network," with physical vulnerabilities. "It matters who controls the nodes." Indeed, he adds, "what's often forgotten is that those networks actually have to physically connect—one router to another—often through something as simple and tangible as a yellow-jacketed fiber-optic cable. It's safe to suspect a network engineer in Egypt had a few of them dangling in his hands last night.

Blum specifically refers to a high-security building in Miami owned by Terremark; it is "the physical meeting point for more than 160 networks from around the world," and thus just one example of what Blum calls an internet "choke point." These international networks "meet there because of the building's excellent security, its redundant power systems, and its thick concrete walls, designed to survive a category 5 hurricane. But above all, they meet there because the building is 'carrier-neutral.' It's a Switzerland of the Internet, an unallied territory where competing networks can connect to each other."

But, as he points out, this neutrality is by no means guaranteed—and is even now subject to change.

Thursday, January 27. 2011

Via Change Observer via Dan Hill

-----

By John Thackara

Gram junkies are those fanatical hikers and climbers who fret about every gram of weight that might be carried — in everything from titanium cook pans to toothbrush covers. Excess weight is not just an objective performance issue for these guys; they take it personally. In the matter of mobility and modern transportation, we all need to become gram junkies. We need to obsess not about speed, or about exotic power sources, but about the weight of every step taken, every vehicle used, every infrastructure investment contemplated.

Why? Because modern mobility not only damages the biosphere, our only home, but also global systems of air. Rail and road travel are also greedy in their use of space, matter, energy, biodiversity and land. Designers around the world are busily developing a dazzling array of solutions to deal with these complex challenges. The website Newmobility.org, for example, has identified 177 different projects and approaches to sustainable mobility. These include bus rapid transit (BRT), car free days, demand-responsive transport (DRT), hitch-hiking, pedestrianization, smart parking strategies and van-pooling.

The trouble is that every solution that assumes our current or increased levels of transport intensity, once whole system costs are calculated, turns out not to be viable. Many transport strategies help solve one or two problems — but exacerbate others. The best-known example is the way that the expansion of highways reduces congestion for a time, but tends to increase total vehicle traffic. Another rebound effect: increased vehicle fuel efficiency conserves energy; but, because it reduces vehicle operating costs, it tends to increase total vehicle travel. The growth of the US Interstate Highway System changed fundamental relationships between time, cost and space. These, in turn, enabled forms of economic development that have proved devastating to the biosphere.

Todd Litman, who runs the Victoria Transport Policy Institute in Canada, points out that depreciation, insurance, registration and residential parking are not directly affected by how much a vehicle is driven. Motorists maximize their vehicle travel to get their money’s worth from such expenditures and receive no incentives to drive less. Litman describes these market distortions as "economic traps" in which competition for resources creates conflicts between individual interests and the common good.

The effects of these economic traps are "cumulative and synergistic" in Litman's words: total impact is greater than the sum of individual effects and these distortions skew countless travel decisions and contribute to a long-term cycle of automobile dependency.

Modern mobility kills people too — but without fuss. The total number of people killed on 9/11 was 2,819. And yes, that was a tragedy. But consider this: An average of 3,242 people die worldwide on the roads each day of the year, year after year. Children are especially vulnerable; traffic accident deaths account for 41 percent of all child deaths by injury.

Even if it doesn't kill you outright, modern mobility contributes to poor health. The highest rates of obesity correlate 1:1 with the proportion of journeys children take by car — and the costs of obesity are heading for 10 percent of US GDP. Increased auto dependency and air pollution also contribute to respiratory illnesses, cardiovascular disease and hospital admissions.

We squander time on mobility. We spend the same amount of time traveling today as we did 50 years ago — but we use that time to travel longer distances. The average German citizen today drives 15,000 km (9,320 miles) a year; in 1950, she covered just 2,000 km (1,242 miles). A lot of our travel time is commuting time and work-related travel that we believe we cannot avoid. We also spend a lot of time traveling in order to shop and to take the kids to distant schools.

Even if modern mobility were not a climate change or social problem, the fact that global mobility depends on a finite energy source — oil — means it is fundamentally not resilient. Whether oil and gas are at a peak, or on a plateau, increasing consumption means that the 9 million gallons of gasoline people currently use in the U.S. each day simply will not be availabl in the future. Ninety-five percent of all transportation depends on oil — and with that, food systems in all developed countries are vulnerable to any disruption in the prevailing logistical system.

To a car company, replacing the chrome wing mirror on an SUV with one made of carbon fiber is a step toward sustainable transportation. To a radical ecologist, all motorized movement is unsustainable. So when is transportation sustainable, and when is it not?

Motorized horse cart featured on the French website Traits en Savoie.

Meterus Horse Power, in France, is modernizing animal traction with an approach that combines technology, ecology, profitability and horse wellness. From Equishop website (Switzerland).

Chris Bradshaw, a transport economist, emphasizes that “light” transport systems are not, per se, sustainable — only less unsustainable than commuting by car. “Light rail supports far-flung suburbs; street cars support, well, street-car suburbs,” Bradshaw says. “A smaller, more efficient, or alternative-fuel vehicle is only less unsustainable than another private vehicle. It will still take up space on the road and in parking lots, it will still threaten the life and limb of others, it will still create noise, and it still will require lots of energy and resources to manufacture, transport to a dealer and dispose of when its life ends.”

Bradshaw wants planners and designers to respect what he calls “the scalar hierarchy.” This is when trips taken most frequently are short enough to be made by walking (even if pulling a small cart), while the next more frequent trips require a bike or street car and so on. “If one adheres to this, then there are so few trips to be made by car, that owning one is foolish.”

Investments in high-speed trains such as they are, is another non-solution. Europeans believe that high-speed trains are environmentally far friendlier than aircraft — but they're not. When researchers at Martin Luther University studied the construction, use and disposal of the high-speed rail infrastructure in Germany, they found that 48 kilograms (about a hundred pounds) of solid primary resources is needed for one passenger to travel 100 kilometers.

China's proposed "straddling" bus would use existing infrastructure to greatly increase capacity along arterial routes.

Is one answer to go by banana boat? Not really. The world's merchant fleet contributes nearly 4.5 percent of all global emissions — a huge amount, up there with cars, housing, agriculture and industry. (Like aviation, shipping emissions are omitted from European targets for cutting global warming.)

Electric cars are the biggest distraction of all. The assumption in European and U.S. policy is that renewable energy-powered smart grids will power millions of electric or hybrid vehicles. Unfortunately, these technology-driven solutions are not viable once the economics of electrical grid modernization are factored in. The German branch of the World Wildlife Foundation (WWF) published a study in May 2009 (conducted with IZES, a German institute for future energy systems). Electric cars only reduce greenhouse gases marginally, they found. The manufacturing processes of both the hybrid and the fully electric car require more energy than those of any conventional petrol-powered car. A worst-case (and frankly most likely) scenario is that most electric cars will be run on electricity from coal instead of from renewable sources.

The least talked about obstacle to electric transportation concerns the raw materials needed to manufacture the vehicles. Rare earth metals are key to global efforts to switch to cleaner energy and therefore transportation. But mining and processing the metals causes immense environmental damage. China’s rare earth industry each year produces more than five times the amount of waste gas, including deadly fluorine and sulfur dioxide, than the total flared annually by all miners and oil refiners in the U.S. Alongside that 13 billion cubic meters of gas is 25 million tons of wastewater laced with cancer-causing heavy metals such as cadmium. And, just as we already have a problem with peak oil, a shortfall looks likely in the world’s capacity to produce lithium. One rare metals expert, William Tahil, claims the production of hybrid and electric cars will soon tax the world’s production of lithium carbonate.

Think More, Move Less

Politicians tend to dissemble or lie, or both, whenever the subject of transportation strategy crops up. Despite proof that transportation damages the biosphere, costs a fortune and kills people, the policy establishment is in thrall to the belief that transportation-enabled economic growth takes priority over all else. This false belief is based on inadequate ecological accounting, and the power of the myriad industries involved. Every aspect of the aviation industry, for example — airplane manufacturers, airlines, airports — is subsidized by direct grants and tax breaks. Remove these hidden subsidies and also charge aviation the true costs of its environmental impact and the whole enterprise becomes un-economic even on its own terms.

Politicians are also scared that no voter will tolerate a curtailment of air travel. The better way to put it is that no rich voter will do so. Only 5 percent of the world’s population has ever flown. Aviation is overwhelmingly an activity of the rich, and strong measures to combat the environmental impact of aviation would not adversely effect poor people.

We once hoped that the internet would replace trips to the mall; that air travel would give way to teleconferencing; and that digital transmission would replace the physical delivery of books and videos. In the event, technology has indeed enabled some of these new kinds of mobility — but in addition to, not as replacements for, the old kinds. The internet has increased transport intensity in the economy as a whole. Rhetoric of a “weightless” economy, the “death of distance” and the “displacement of “matter by mind” sound ridiculous in retrospect.

Rather than tinker with symptoms — such as inventing hydrogen-powered vehicles, or turning gas stations into battery stations — the more interesting and pertinent design task is to re-think the way we use time and space and to reduce the movement of matter — whether goods or people — by changing the word "faster" to "closer."

Our transportation challenge can be compared to distributed computing. The speed-obsessed computer world, in which network designers rail against delays measured in milliseconds, is years ahead of the rest of us in rethinking space-time issues. It can teach us how to rethink relationships between place and time in the real world, too. Embedded on microchips, computer operations entail careful accounting for the speed of light. The problem geeks struggle constantly with is called latency — the delay caused by the time it takes for a remote request to be serviced, or for a message to travel between two processing nodes. Another key word, attenuation, describes the loss of transmitted signal strength as a result of interference — a weakening of the signal as it travels farther from its source — much as the taste of strawberries grown in Spain weakens as they are trucked to faraway places. The brick walls of latency and attenuation prompt computer designers to talk of a “light-speed crisis” in microprocessor design. The clever design solution to the light-speed crisis is to move processors closer to the data — in ecological terms, to re-localize the economy.

Network designers are good localizers. Striving to reduce geodesic distance, they have developed the so-called store-width paradigm or “cache and carry.” They focus on copying, replicating and storing web pages as close as possible to their final destination, at content access points. Thus, if you go online to retrieve a large software update from an online file library, you are often given a choice of countries from which to download it. This technique is called “load balancing” — even though the loads in question, packets of information, don’t actually weigh anything in real-world terms. Cache-and-carry companies maintain tens of thousand of such caches around the world.

By monitoring demand for each item downloaded and making more copies available in its caches when demand rises and fewer when demand falls, operators help to smooth out huge fluctuations in traffic. Other companies combine the cache-and-carry approach with smart file sharing, or "portable shared memory parallel programming." Users’ own computers, anywhere on the internet, are used as shared memory systems so that recently accessed content can be delivered quickly when needed to other users nearby on the network.

The Law of Locality

My favorite example of decentralized production concerns drinks. The weight of beer and other beverages, especially mineral water, trucked from one rich nation to another is a large component of the freight flood that threatens to overwhelm us. But first Coca-Cola and now a boom in microbreweries demonstrate a radically lighter approach: Export the recipe and sometimes the production equipment, but source raw material and distribute locally.

People and information want to be closer. When planning where to put capacity, network designers are guided by the law of locality; this law states that network traffic is at least 80 percent local, 95 percent continental and only 5 percent intercontinental. Communication network designers use another rule that we can learn from in the analogue world: “The less the space, the more the room.” In silicon, the trade-off between speed and heat generated improves dramatically as size diminishes: Small transistors run faster, cooler and cheaper. Hence the development of the so-called processor-in-memory (PIM) — an integrated circuit that contains both memory and logic on the same chip.

So, too, in the analogue world: radically decentralized architectures of production and distribution can radically reduce the material costs of production. We need to build systems that take advantage of the power of networks — but that do so in ways that optimize local-ness.

This design principle — “the less the space, the more the room” — is nowhere better demonstrated than in the human brain. The brain, in Edward O. Wilson's words, is “like one hundred billion squids linked together... an intricately-wired system of nerve cells, each a few millionths of a meter wide, that are connected to other nerve cells by hundreds of thousands of endings. Information transfer in brains is improved when neuron circuits, filling specialized functions, are placed together in clusters.”

Neurobiologists have discovered an extraordinary array of such functions: sensory relay stations, integrative centers, memory modules, emotional control centers, among others. The ideal brain case is spherical or close to it, Wilson observes, because a sphere has the smallest surface relative to volume of any geometric form. A sphere also allows more circuits to be placed close together; the average length of circuits can thus be minimized, which raises the speed of transmission while lowering the energy cost for their construction and maintenance.

Like gram junkies, the mobility dilemma is not as hard to solve as it looks once one replaces the word “speed” with the word “weight.” By changing the success measurement from faster to closer, it becomes possible to borrow from other domains, such as microprocessor design, network topography and the geodesy of the human brain. The biosphere itself is the result of 3.8 billion years of iterative, trial-and-error design — so we can safely assume it’s an optimized solution. As Janine Benyus explains in her wonderful book Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature, biological communities, by and large, are localized or relatively closely connected in time and space. Their energy flux is low, distances covered are proximate. With the exception of a few high-flying species, in other words, “nature does not commute to work.”

Personal comment:

A documented essay from John Thackara about the different forms of mobility and their footprints. With some consideration on the "immobile mobility" or rather "mediated mobility" and an interesting proposal about the "law of locality" taking its inspiration in network computing.

Monday, December 20. 2010

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

A visit to FedEx's SuperHub, where technology powers the global economy while you sleep.

By Jeffrey F. Rayport

|

| Move it: At the FedEx SuperHub in Memphis, chutes and conveyor belts carry more than 1.2 million packages each night. |

The retail season is in full swing for the holidays, and it couldn't happen without two giants of logistics, UPS and FedEx. As those brown UPS trucks remind us, the global economy thrives on "synchronizing the world of commerce."

Not long ago, I talked with FedEx founder Fred Smith at a World 50 meeting of executives in Memphis, Tennessee. More recently I visited the company's operations in the midst of holiday-season madness.

Here is some of what I learned:

Make no little plans. The great architect Daniel Burnham once said, "Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men's blood and probably will not themselves be realized."

Fred Smith's inspiration for FedEx involved no little plans. The result is the largest air-cargo company in the world: it employs 290,000 people, maintains a fleet of 75,000 trucks, and owns and operates 684 jets. It has more wide-body jets than any airline, including Boeing 777s that can fly from Shanghai to Memphis nonstop. The SuperHub, the heart of FedEx's operations, measures four by four miles and occupies 900 acres. Some 30,000 people are needed to run it.

In many ways, the SuperHub dwarfs its "big brother," Memphis International Airport. The SuperHub is a world unto itself, with a hospital, a fire station, a meteorology unit, and a private security force; it has branches of U.S. Customs and Homeland Security, plus anti-terror operations no one will talk about. It has 20 electric power generators as backup to keep it running if the power grid goes down.

Every weekday night at the SuperHub, FedEx lands, unloads (in just half an hour, even for a super-jumbo 777), reloads, and flies out 150 to 200 jets. Its aircraft take off and land every 90 seconds. This all happens between 11 p.m. and 4 a.m. Central Time. The SuperHub processes between 1.2 million and 1.6 million packages a night.

From Thanksgiving to Christmas, FedEx will ship 223 million packages worldwide. Last Monday, its busiest night ever, it moved 16 million packages.

Be a speed demon and a control freak. Walking the SuperHub, you can feel the need for speed. Planes land continually and disgorge oversized aluminum containers; parcels of all shapes and sizes zoom into processing centers on hyper-kinetic conveyor belts; and no fewer than 2,000 drivers of light trucks, forklifts, and small industrial vehicles swarm throughout the facility. To control it all, everything and everyone is UPC-tagged; everyone and everything is tracked.

Nothing illustrates the point better than the Small Package Sortation System, a vast, FedEx-designed machine that sits in its own warehouse. It cost $175 million to build and sorts an average of 1.2 million packages a night. It scans the bar code on every package at least 30 times. Any delays in the process can get detected in minutes. That's why the U.S. Postal Service has become one of FedEx's major accounts. FedEx's SmartPost operation delivers the "last mile" for much of the United States' daily mail.

Because FedEx is as disciplined and reliable as it is, standard items it ships include chemotherapy drugs, human hearts and other live human organs, artificial joints, contact lenses, surgical scalpels, fresh blood, heart monitors, circuit boards, auto bumpers, tractor parts, Swiss watch elements, rare manuscripts, aviation components, Maine lobsters, crickets, whales, snakes, Japanese cherries, Hawaiian flowers, tennis shoes, and European fragrances. Oh, and FedEx also transports the occasional Arabian race horse and antique automobile. Any large cargo, from 150 pounds to 2,000 pounds, is fair game.

It's about the information, stupid. IT both created demand for FedEx's services (Dell was one of FedEx's first tech customers) and enabled FedEx to thrive. Smith realized that tracking packages—knowing points of origin, movement through the system, and estimated times of arrival—was nearly as valuable as the packages themselves. Today's FedEx has made innovative uses of new data-tracking technologies, such as QR codes and RFID tags. The latter report on temperature and moisture conditions of individual packages as they move from origination point to destination.

If there were "Seven Wonders of the Industrial World," FedEx's SuperHub would easily rank among them, right up there with Toyota's production centers, Google's data centers, and NASA's Mission Control.

Jeffrey F. Rayport is a former faculty member at Harvard Business School and the author of several books about electronic commerce. He is the founder of Marketspace LLC, a strategic advisory company. Currently, he is an operating partner at Castanea Partners, a Boston-based private equity firm.

Copyright Technology Review 2010.

Wednesday, October 27. 2010

Via Mammoth

-----

by rholmes

[Murmansk in polar night, photographed by flickr user euno.]

The Wall Street Journal recently ran a fascinating excerpt from geoscientist Laurence Smith’s new book, The World in 2050, which looks at how four global “megatrends” — “human population growth and migration; growing demand for control over such natural resource ’services’ as photosynthesis and bee pollination; globalization; and climate change” — are fueling both international involvement and urban growth in the Arctic:

Much of the planet’s northern quarter of latitude, including the Arctic, is poised to undergo tremendous transformation over the next century. As a booming population increases the demand for the Earth’s natural resources, and as lands closer to the equator face the prospect of rising water demand, droughts and other likely changes, the prominence of northern countries will rise along with their projected milder winters…

[In 2050, this] New North… might be something like America in 1803, just after the Louisiana Purchase from France. It, too, possessed major cities fueled by foreign immigration, with a vast, inhospitable frontier distant from the major urban cores. Its deserts, like Arctic tundra, were harsh, dangerous and ecologically fragile. It, too, had rich resource endowments of metals and hydrocarbons. It, too, was not really an empty frontier but already occupied by indigenous peoples who had been living there for millennia.

Flying over the American West today, one still sees landscapes that are barren and sparsely populated. Its towns and cities are relatively few, scattered across miles of empty desert. Yet its population is growing, its cities like Phoenix and Salt Lake and Las Vegas humming economic forces with cultural and political significance. This is how I imagine the coming human expansion in the New North. We’re not all about to move there, but it will integrate with the rest of the world in some very important ways.

I imagine the high Arctic, in particular, will be rather like Nevada—a landscape nearly empty but with fast-growing towns. Its prime socioeconomic role in the 21st century will not be homestead haven but economic engine, shoveling gas, oil, minerals and fish into the gaping global maw.

Read the full article at the Wall Street Journal.

Personal comment:

Of course, this makes me think of the project we've done last summer, Arctic Opening. The arctic region will certainly be the area where the fate of all "sustainable" approaches will finally be decided... And for my part, I'm not very optimistic about it unfortunately.

If we fail there (a new run for oil, gaz and natural ressources --not to mention for human living spaces-- that will possibly destroy the land), we'll probably fail everywhere else.

Thursday, October 07. 2010

How Globalization Is Bad for the World Economy

Evolutionary theory predicts that globalization should increase the risk of recession and slow recovery rates, a phenomenon borne out by real data, say econophysicists.

Biologists have long puzzled over the modular structure of living things, a module being a structure that can function relatively independently from other parts of the system. So a module might be an ecology, a society within that ecology, an individual animal, an organ, a cell within that organ, a gene within that cell, and so on.

Nature simply wreaks of modularity throughout its hierarchy. The question, until recently, was why. A couple of years back, Jun Sun and Michael Deem, a couple of of physicists at Rice University in Houston, came up with an answer. They said modularity allows a system to more easily evolve and reduces the chances of catastrophic collapse due to some kind of outside influence, such as climate change or disease.

They went to show that modularity emerges spontaneously in a evolutionary algorithms that change relatively slowly and swap information.

Today Deem and Jiankui He, also at Rice, apply this idea to the global trade network. Their hypothesis is that this network evolves in exactly the same way as natural systems, or at least, that it is constrained in the same way by the rate at which it changes, the fact that information flows within it.

That implies that modular structures ought to form spontaneously on all kinds of scales within this network. And indeed they do in the form of companies, trade groups, countries and so on.

However, globalization is a process that reduces modularity because it encourages an equality of trade between entities in different parts of the world. But in naturally evolved systems, far from increasing the robustness of the system to perturbations, a drop in modularity decreases it. Deem and He hypothesise that the same thing happens in the gobal trade network.

What's surprising is that their idea is actually borne out by the data. They've studied the nature of various global recessions since 1969 and say that the increase in globalization makes the global economy less stable. What's more, when a recession does hit, the recovery becomes slower as globalization increases.

The explanation is that modularity allows a hierarchy to form within a system and this helps a system to recover when trouble strikes. If this structure is absent or reduced in form, then the recovery is slower. Globalization seems to discourage the formation of the kind of trade groups that would form these structures.

Deem and He say the global economy is actually more fragile today than it was 40 years ago.

They also make a prediction. They say that a recession should encourage the formation hierarchies at least temporarily. What they mean is the formation of trade groups who trade preferentially with each other.

That doesn't sound too far fetched and given that the global economy is currently attempting to lift itself out of recession it shouldn't be too hard to test either.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1010.0410: Structure and Response in the World Trade Network

Personal comment:

Again, how globalization is considered to create depletion (in societies, ecologies, culture, etc.). And it looks to be true in most contexts.

On the other side, if we try to look for positive things, globalization and somehow the possibility to be mobile both physically and virtually also creates knowledge (the possibility to discover and experience other cultures, biotopes & enviroments, spaces, climates, contents, etc.) and miscgenation/creolization (a "recent" type of culture and spaces that is far from depletion). It does create (interesting things) too.

We won't go back to a fully "local world" I believe (would you like to be stuck in your little fragment of the world again? I don't and probably most people that went mobile and discovered others won't), as the globe is shrinking for centuries now.

So, the challenge would be rather to develop a "sustainable and culturally diversified/diversifying hyper localization --in the sense of a very connected (both immaterially and physically) local environment--, with all sorts of mobile and immobile --in the sense of mediated-- mobilities". At least this is what we are working on and trying to do at fabric | ch.

The concepts of "modules" and "modularity" in this article from the MIT, the flow of information within it and with its environment, etc. even if taken from economic's theory... is therefore quite interesting when one starts to think about "very connected local environment".

|

[Image: Diagrammatic explanation of a "light cone," courtesy of

[Image: Diagrammatic explanation of a "light cone," courtesy of  [Image: An otherwise unrelated image from NOAA featuring a geodetic

[Image: An otherwise unrelated image from NOAA featuring a geodetic  If Atlanta's Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport were to become its own country, its annual workforce and user base would make it "the twelfth most populous nation on Earth," as John Kasarda and Greg Lindsey explain in

If Atlanta's Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport were to become its own country, its annual workforce and user base would make it "the twelfth most populous nation on Earth," as John Kasarda and Greg Lindsey explain in  [Image: A plan of Atlanta's Hartsfield-Jackson Airport, via

[Image: A plan of Atlanta's Hartsfield-Jackson Airport, via

[Images: Dubai International Airport promotional images; vertical distortion is in the originals. Courtesy of the

[Images: Dubai International Airport promotional images; vertical distortion is in the originals. Courtesy of the  [Images: Laser-guided FedEx hub urbanism at work; all images courtesy of

[Images: Laser-guided FedEx hub urbanism at work; all images courtesy of  [Image: The now-erased runways of Denver's old Stapleton Airport; the airfield has since become a New Urbanist

[Image: The now-erased runways of Denver's old Stapleton Airport; the airfield has since become a New Urbanist  [Image: A rendering of

[Image: A rendering of  [Image: Le Corbusier's infamous Plan Voisin, meant to replace the heart of Paris, France].

[Image: Le Corbusier's infamous Plan Voisin, meant to replace the heart of Paris, France].

[Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of