Wednesday, April 08. 2015

Via The Guardian

-----

By Steven Poole

Songdo in South Korea: a ‘smart city’ whose roads and water, waste and electricity systems are dense with electronic sensors. Photograph: Hotaik Sung/Alamy.

A woman drives to the outskirts of the city and steps directly on to a train; her electric car then drives itself off to park and recharge. A man has a heart attack in the street; the emergency services send a drone equipped with a defibrillator to arrive crucial minutes before an ambulance can. A family of flying maintenance robots lives atop an apartment block – able to autonomously repair cracks or leaks and clear leaves from the gutters.

Such utopian, urban visions help drive the “smart city” rhetoric that has, for the past decade or so, been promulgated most energetically by big technology, engineering and consulting companies. The movement is predicated on ubiquitous wireless broadband and the embedding of computerised sensors into the urban fabric, so that bike racks and lamp posts, CCTV and traffic lights, as well as geeky home appliances such as internet fridges and remote-controlled heating systems, become part of the so-called “internet of things” (the global market for which is now estimated at $1.7tn). Better living through biochemistry gives way to a dream of better living through data. You can even take an MSc in Smart Cities at University College, London.

Yet there are dystopian critiques, too, of what this smart city vision might mean for the ordinary citizen. The phrase itself has sparked a rhetorical battle between techno-utopianists and postmodern flâneurs: should the city be an optimised panopticon, or a melting pot of cultures and ideas?

And what role will the citizen play? That of unpaid data-clerk, voluntarily contributing information to an urban database that is monetised by private companies? Is the city-dweller best visualised as a smoothly moving pixel, travelling to work, shops and home again, on a colourful 3D graphic display? Or is the citizen rightfully an unpredictable source of obstreperous demands and assertions of rights? “Why do smart cities offer only improvement?” asks the architect Rem Koolhaas. “Where is the possibility of transgression?”

Smart beginnings: a crowd watches as new, automated traffic lights are erected at Ludgate Circus, London, in 1931. Photograph: Fox Photos/Getty Images

The smart city concept arguably dates back at least as far as the invention of automated traffic lights, which were first deployed in 1922 in Houston, Texas. Leo Hollis, author of Cities Are Good For You, says the one unarguably positive achievement of smart city-style thinking in modern times is the train indicator boards on the London Underground. But in the last decade, thanks to the rise of ubiquitous internet connectivity and the miniaturisation of electronics in such now-common devices as RFID tags, the concept seems to have crystallised into an image of the city as a vast, efficient robot – a vision that originated, according to Adam Greenfield at LSE Cities, with giant technology companies such as IBM, Cisco and Software AG, all of whom hoped to profit from big municipal contracts.

“The notion of the smart city in its full contemporary form appears to have originated within these businesses,” Greenfield notes in his 2013 book Against the Smart City, “rather than with any party, group or individual recognised for their contributions to the theory or practice of urban planning.”

Whole new cities, such as Songdo in South Korea, have already been constructed according to this template. Its buildings have automatic climate control and computerised access; its roads and water, waste and electricity systems are dense with electronic sensors to enable the city’s brain to track and respond to the movement of residents. But such places retain an eerie and half-finished feel to visitors – which perhaps shouldn’t be surprising. According to Antony M Townsend, in his 2013 book Smart Cities, Songdo was originally conceived as “a weapon for fighting trade wars”; the idea was “to entice multinationals to set up Asian operations at Songdo … with lower taxes and less regulation”.

In India, meanwhile, prime minister Narendra Modi has promised to build no fewer than 100 smart cities – a competitive response, in part, to China’s inclusion of smart cities as a central tenet of its grand urban plan. Yet for the near-term at least, the sites of true “smart city creativity” arguably remain the planet’s established metropolises such as London, New York, Barcelona and San Francisco. Indeed, many people think London is the smartest city of them all just now — Duncan Wilson of Intel calls it a “living lab” for tech experiments.

So what challenges face technologists hoping to weave cutting-edge networks and gadgets into centuries-old streets and deeply ingrained social habits and patterns of movement? This was the central theme of the recent “Re.Work Future Cities Summit” in London’s Docklands – for which two-day public tickets ran to an eye-watering £600.

The event was structured like a fast-cutting series of TED talks, with 15-minute investor-friendly presentations on everything from “emotional cartography” to biologically inspired buildings. Not one non-Apple-branded laptop could be spotted among the audience, and at least one attendee was seen confidently sporting the telltale fat cyan arm of Google Glass on his head.

“Instead of a smart phone, I want you all to have a smart drone in your pocket,” said one entertaining robotics researcher, before tossing up into the auditorium a camera-equipped drone that buzzed around like a fist-sized mosquito. Speakers enthused about the transport app Citymapper, and how the city of Zurich is both futuristic and remarkably civilised. People spoke about the “huge opportunity” represented by expanding city budgets for technological “solutions”.

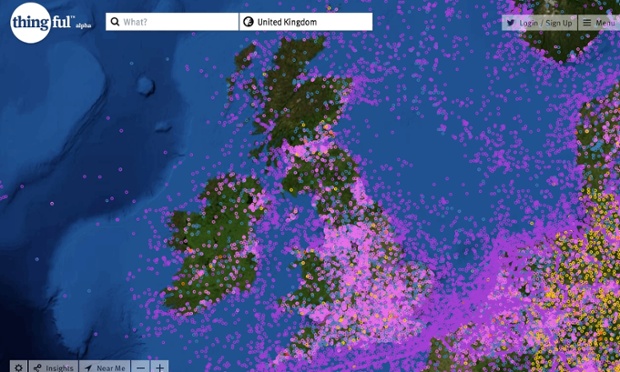

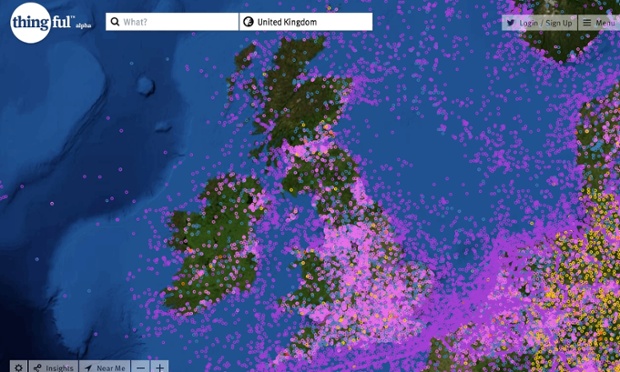

Usman Haque’s project Thingful is billed as a ‘search engine for the internet of things’

Strikingly, though, many of the speakers took care to denigrate the idea of the smart city itself, as though it was a once-fashionable buzzphrase that had outlived its usefulness. This was done most entertainingly by Usman Haque, of the urban consultancy Umbrellium. The corporate smart-city rhetoric, he pointed out, was all about efficiency, optimisation, predictability, convenience and security. “You’ll be able to get to work on time; there’ll be a seamless shopping experience, safety through cameras, et cetera. Well, all these things make a city bearable, but they don’t make a city valuable.”

As the tech companies bid for contracts, Haque observed, the real target of their advertising is clear: “The people it really speaks to are the city managers who can say, ‘It wasn’t me who made the decision, it was the data.’”

Of course, these speakers who rejected the corporate, top-down idea of the smart city were themselves demonstrating their own technological initiatives to make the city, well, smarter. Haque’s project Thingful, for example, is billed as a search engine for the internet of things. It could be used in the morning by a cycle commuter: glancing at a personalised dashboard of local data, she could check local pollution levels and traffic, and whether there are bikes in the nearby cycle-hire rack.

“The smart city was the wrong idea pitched in the wrong way to the wrong people,” suggested Dan Hill, of urban innovators the Future Cities Catapult. “It never answered the question: ‘How is it tangibly, materially going to affect the way people live, work, and play?’” (His own work includes Cities Unlocked, an innovative smartphone audio interface that can help visually impaired people navigate the streets.) Hill is involved with Manchester’s current smart city initiative, which includes apparently unglamorous things like overhauling the Oxford Road corridor – a bit of “horrible urban fabric”. This “smart stuff”, Hill tells me, “is no longer just IT – or rather IT is too important to be called IT any more. It’s so important you can’t really ghettoise it in an IT city. A smart city might be a low-carbon city, or a city that’s easy to move around, or a city with jobs and housing. Manchester has recognised that.”

One take-home message of the conference seemed to be that whatever the smart city might be, it will be acceptable as long as it emerges from the ground up: what Hill calls “the bottom-up or citizen-led approach”. But of course, the things that enable that approach – a vast network of sensors amounting to millions of electronic ears, eyes and noses – also potentially enable the future city to be a vast arena of perfect and permanent surveillance by whomever has access to the data feeds.

Inside Rio de Janeiro’s centre of operations: ‘a high-precision control panel for the entire city’. Photograph: David Levene

One only has to look at the hi-tech nerve centre that IBM built for Rio de Janeiro to see this Nineteen Eighty-Four-style vision already alarmingly realised. It is festooned with screens like a Nasa Mission Control for the city. As Townsend writes: “What began as a tool to predict rain and manage flood response morphed into a high-precision control panel for the entire city.” He quotes Rio’s mayor, Eduardo Paes, as boasting: “The operations centre allows us to have people looking into every corner of the city, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.”

What’s more, if an entire city has an “operating system”, what happens when it goes wrong? The one thing that is certain about software is that it crashes. The smart city, according to Hollis, is really just a “perpetual beta city”. We can be sure that accidents will happen – driverless cars will crash; bugs will take down whole transport subsystems or the electricity grid; drones could hit passenger aircraft. How smart will the architects of the smart city look then?

A less intrusive way to make a city smarter might be to give those who govern it a way to try out their decisions in virtual reality before inflicting them on live humans. This is the idea behind city-simulation company Simudyne, whose projects include detailed computerised models for planning earthquake response or hospital evacuation. It’s like the strategy game SimCity – for real cities. And indeed Simudyne now draws a lot of its talent from the world of videogames. “When we started, we were just mathematicians,” explains Justin Lyon, Simudyne’s CEO. “People would look at our simulations and joke that they were inscrutable. So five or six years ago we developed a new system which allows you to make visualisations – pretty pictures.” The simulation can now be run as an immersive first-person gameworld, or as a top-down SimCity-style view, where “you can literally drop policy on to the playing area”.

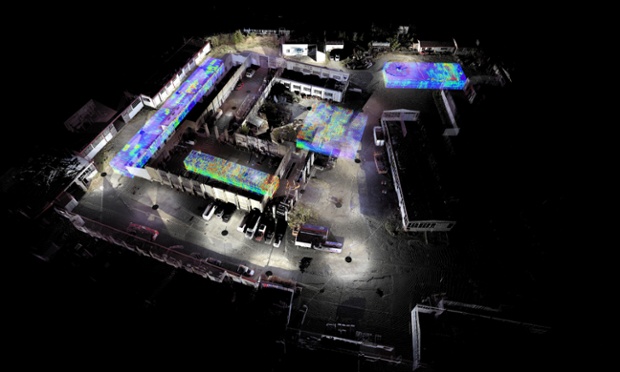

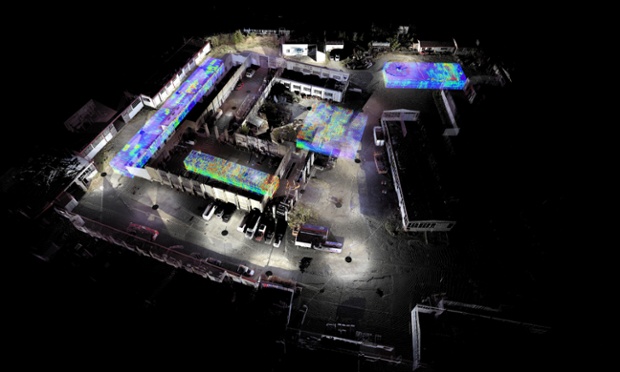

Another serious use of “pretty pictures” is exemplified by the work of ScanLAB Projects, which uses Lidar and ground-penetrating radar to make 3D visualisations of real places. They can be used for art installations and entertainment: for example, mapping underground ancient Rome for the BBC. But the way an area has been used over time, both above and below ground, can also be presented as a layered historical palimpsest, which can serve the purposes of archaeological justice and memory – as with ScanLAB’s Living Death Camps project with Forensic Architecture, on two concentration-camp sites in the former Yugoslavia.

The former German pavilion at Staro Sajmište, Belgrade – produced from terrestrial laser scanning and ground-penetrating radar as part of the Living Death Camps project. Photograph: ScanLAB Projects

For Simudyne’s simulations, meanwhile, the visualisations work to “gamify” the underlying algorithms and data, so that anyone can play with the initial conditions and watch the consequences unfold. Will there one day be convergence between this kind of thing and the elaborately realistic modelled cities that are built for commercial videogames? “There’s absolutely convergence,” Lyon says. A state-of-the art urban virtual reality such as the recreation of Chicago in this year’s game Watch Dogs requires a budget that runs to scores of millions of dollars. But, Lyon foresees, “Ten years from now, what we see in Watch Dogs today will be very inexpensive.”

What if you could travel through a visually convincing city simulation wearing the VR headset, Oculus Rift? When Lyon first tried one, he says, “Everything changed for me.” Which prompts the uncomfortable thought that when such simulations are indistinguishable from the real thing (apart from the zero possibility of being mugged), some people might prefer to spend their days in them. The smartest city of the future could exist only in our heads, as we spend all our time plugged into a virtual metropolitan reality that is so much better than anything physically built, and fail to notice as the world around us crumbles.

In the meantime, when you hear that cities are being modelled down to individual people – or what in the model are called “agents” – you might still feel a jolt of the uncanny, and insist that free-will makes your actions in the city unpredictable. To which Lyon replies: “They’re absolutely right as individuals, but collectively they’re wrong. While I can’t predict what you are going to do tomorrow, I can have, with some degree of confidence, a sense of what the crowd is going to do, what a group of people is going to do. Plus, if you’re pulling in data all the time, you use that to inform the data of the virtual humans.

“Let’s say there are 30 million people in London: you can have a simulation of all 30 million people that very closely mirrors but is not an exact replica of London. You have the 30 million agents, and then let’s have a business-as-usual normal commute, let’s have a snowstorm, let’s shut down a couple of train lines, or have a terrorist incident, an earthquake, and so on.” Lyons says you will get a highly accurate sense of how people, en masse, will respond to these scenarios. “While I’m not interested in a specific individual, I’m interested in the emergent behaviour of the crowd.”

City-simulation company Simudyne creates computerised models ‘with pretty pictures’ to aid disaster-response planning

But what about more nefarious bodies who are interested in specific individuals? As citizens stumble into a future where they will be walking around a city dense with sensors, cameras and drones tracking their every movement – even whether they are smiling (as has already been tested at the Cheltenham Jazz Festival) or feeling gloomy – there is a ticking time-bomb of arguments about surveillance and privacy that will dwarf any previous conversations about Facebook or even, perhaps, government intelligence agencies scanning our email. Unavoidable advertising spam everywhere you go, as in Minority Report, is just the most obvious potential annoyance. (There have already been “smart billboards” that recognised Minis driving past and said hello to them.) The smart city might be a place like Rio on steroids, where you can never disappear.

“If you have a mobile phone, and the right sensors are deployed across the city, people have demonstrated the ability to track those individual phones,” Lyon points out. “And there’s nothing that would prevent you from visualising that movement in a SimCity-like landscape, like in Watch Dogs where you see an avatar moving through the city and you can call up their social-media profile. If you’re trying to search a very large dataset about how someone’s moving, it’s very hard to get your head around it, but as soon as you fire up a game-style visualisation, it’s very easy to see, ‘Oh, that’s where they live, that’s where they work, that’s where their mistress must be, that’s where they go to drink a lot.’”

This is potentially an issue with open-data initiatives such as those currently under way in Bristol and Manchester, which is making publicly available the data it holds about city parking, procurement and planning, public toilets and the fire service. The democratic motivation of this strand of smart-city thinking seems unimpugnable: the creation of municipal datasets is funded by taxes on citizens, so citizens ought to have the right to use them. When presented in the right way – “curated”, if you will, by the city itself, with a sense of local character – such information can help to bring “place back into the digital world”, says Mike Rawlinson of consultancy City ID, which is working with Bristol on such plans.

But how safe is open data? It has already been demonstrated, for instance, that the openly accessible data of London’s cycle-hire scheme can be used to track individual cyclists. “There is the potential to see it all as Big Brother,” Rawlinson says. “If you’re releasing data and people are reusing it, under what purpose and authorship are they doing so?” There needs, Hill says, to be a “reframed social contract”.

The interface of Simudyne’s City Hospital EvacSim

Sometimes, at least, there are good reasons to track particular individuals. Simudyne’s hospital-evacuation model, for example, needs to be tied in to real data. “Those little people that you see [on screen], those are real people, that’s linking to the patient database,” Lyon explains – because, for example, “we need to be able to track this poor child that’s been burned.” But tracking everyone is a different matter: “There could well be a backlash of people wanting literally to go off-grid,” Rawlinson says. Disgruntled smart citizens, unite: you have nothing to lose but your phones.

In truth, competing visions of the smart city are proxies for competing visions of society, and in particular about who holds power in society. “In the end, the smart city will destroy democracy,” Hollis warns. “Like Google, they’ll have enough data not to have to ask you what you want.”

You sometimes see in the smart city’s prophets a kind of casual assumption that politics as we know it is over. One enthusiastic presenter at the Future Cities Summit went so far as to say, with a shrug: “Internet eats everything, and internet will eat government.” In another presentation, about a new kind of “autocatalytic paint” for street furniture that “eats” noxious pollutants such as nitrous oxide, an engineer in a video clip complained: “No one really owns pollution as a problem.” Except that national and local governments do already own pollution as a problem, and have the power to tax and regulate it. Replacing them with smart paint ain’t necessarily the smartest thing to do.

And while some tech-boosters celebrate the power of companies such as Über – the smartphone-based unlicensed-taxi service now banned in Spain and New Delhi, and being sued in several US states – to “disrupt” existing transport infrastructure, Hill asks reasonably: “That Californian ideology that underlies that user experience, should it really be copy-pasted all over the world? Let’s not throw away the idea of universal service that Transport for London adheres to.”

Perhaps the smartest of smart city projects needn’t depend exclusively – or even at all – on sensors and computers. At Future Cities, Julia Alexander of Siemens nominated as one of the “smartest” cities in the world the once-notorious Medellin in Colombia, site of innumerable gang murders a few decades ago. Its problem favelas were reintegrated into the city not with smartphones but with publicly funded sports facilities and a cable car connecting them to the city. “All of a sudden,” Alexander said, “you’ve got communities interacting” in a way they never had before. Last year, Medellin – now the oft-cited poster child for “social urbanism” – was named the most innovative city in the world by the Urban Land Institute.

One sceptical observer of many presentations at the Future Cities Summit, Jonathan Rez of the University of New South Wales, suggests that “a smarter way” to build cities “might be for architects and urban planners to have psychologists and ethnographers on the team.” That would certainly be one way to acquire a better understanding of what technologists call the “end user” – in this case, the citizen. After all, as one of the tribunes asks the crowd in Shakespeare’s Coriolanus: “What is the city but the people?”

Friday, March 13. 2015

Via Rhizome

-----

"Computing has always been personal. By this I mean that if you weren't intensely involved in it, sometimes with every fiber in your body, you weren't doing computers, you were just a user."

Ted Nelson

Tuesday, December 23. 2014

Note: while I'm rather against too much security (therefore, not "Imposing security") and probably reticent to the fact that we, as human beings, are "delegating" too far our daily routines and actions to algorithms (which we wrote), this article stresses the importance of code in our everyday life as well as the fact that it goes down to the language which is used to code a program. Interesting to know that some coding languages are more likely to produce mistakes and errors.

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

Computer programmers won’t stop making dangerous errors on their own. It’s time they adopted an idea that makes the physical world safer.

By Simson Garfinkel

Three computer bugs this year exposed passwords, e-mails, financial data, and other kinds of sensitive information connected to potentially billions of people. The flaws cropped up in different places—the software running on Web servers, iPhones, the Windows operating system—but they all had the same root cause: careless mistakes by programmers.

Each of these bugs—the “Heartbleed” bug in a program called OpenSSL, the “goto fail” bug in Apple’s operating systems, and a so-called “zero-day exploit” discovered in Microsoft’s Internet Explorer—was created years ago by programmers writing in C, a language known for its power, its expressiveness, and the ease with which it leads programmers to make all manner of errors. Using C to write critical Internet software is like using a spring-loaded razor to open boxes—it’s really cool until you slice your fingers.

Alas, as dangerous as it is, we won’t eliminate C anytime soon—programs written in C and the related language C++ make up a large portion of the software that powers the Internet. New projects are being started in these languages all the time by programmers who think they need C’s speed and think they’re good enough to avoid C’s traps and pitfalls.

But even if we can’t get rid of that language, we can force those who use it to do a better job. We would borrow a concept used every day in the physical world.

Obvious in retrospect

Of the three flaws, Heartbleed was by far the most significant. It is a bug in a program that implements a protocol called Secure Sockets Layer/Transport Layer Security (SSL/TLS), which is the fundamental encryption method used to protect the vast majority of the financial, medical, and personal information sent over the Internet. The original SSL protocol made Internet commerce possible back in the 1990s. OpenSSL is an open-source implementation of SSL/TLS that’s been around nearly as long. The program has steadily grown and been extended over the years.

Today’s cryptographic protocols are thought to be so strong that there is, in practice, no way to break them. But Heartbleed made SSL’s encryption irrelevant. Using Heartbleed, an attacker anywhere on the Internet could reach into the heart of a Web server’s memory and rip out a little piece of private data. The name doesn’t come from this metaphor but from the fact that Heartbleed is a flaw in the “heartbeat” protocol Web browsers can use to tell Web servers that they are still connected. Essentially, the attacker could ping Web servers in a way that not only confirmed the connection but also got them to spill some of their contents. It’s like being able to check into a hotel that occasionally forgets to empty its rooms’ trash cans between guests. Sometimes these contain highly valuable information.

Heartbleed resulted from a combination of factors, including a mistake made by a volunteer working on the OpenSSL program when he implemented the heartbeat protocol. Although any of the mistakes could have happened if OpenSSL had been written in a modern programming language like Java or C#, they were more likely to happen because OpenSSL was written in C.

Many developers design their own reliability tests and then run the tests themselves. Even in large companies, code that seems to work properly is frequently not tested for lurking flaws.

Apple’s flaw came about because some programmer inadvertently duplicated a line of code that, appropriately, read “goto fail.” The result was that under some conditions, iPhones and Macs would silently ignore errors that might occur when trying to ascertain the legitimacy of a website. With knowledge of this bug, an attacker could set up a wireless access point that might intercept Internet communications between iPhone users and their banks, silently steal usernames and passwords, and then reëncrypt the communications and send them on their merry way. This is called a “man-in-the-middle” attack, and it’s the very sort of thing that SSL/TLS was designed to prevent.

Remarkably, “goto fail” happened because of a feature in the C programming language that was known to be problematic before C was even invented! The “goto” statement makes a computer program jump from one place to another. Although such statements are common inside the computer’s machine code, computer scientists have tried for more than 40 years to avoid using “goto” statements in programs that they write in so-called “high-level language.” Java (designed in the early 1990s) doesn’t have a “goto” statement, but C (designed in the early 1970s) does. Although the Apple programmer responsible for the “goto fail” problem could have made a similar mistake without using the “goto” statement, it would have been much less probable.

We know less about the third bug because the underlying source code, part of Microsoft’s Internet Explorer, hasn’t been released. What we do know is that it was a “use after free” error: the program tells the operating system that it is finished using a piece of memory, and then it goes ahead and uses that memory again. According to the security firm FireEye, which tracked down the bug after hackers started using it against high-value targets, the flaw had been in Internet Explorer since August 2001 and affected more than half of those who got on the Web through traditional PCs. The bug was so significant that the Department of Homeland Security took the unusual step of telling people to temporarily stop running Internet Explorer. (Microsoft released a patch for the bug on May 1.)

Automated inspectors

There will always be problems in anything designed or built by humans, of course. That’s why we have policies in the physical world to minimize the chance for errors to occur and procedures designed to catch the mistakes that slip through.

Home builders must follow building codes, which regulate which construction materials can be used and govern certain aspects of the building’s layout—for example, hallways must reach a minimum width, and fire exits are required. Building inspectors visit the site throughout construction to review the work and make sure that it meets the codes. Inspectors will make contractors open up walls if they’ve installed them before getting the work inside inspected.

The world of software development is completely different. It’s common for developers to choose the language they write in and the tools they use. Many developers design their own reliability tests and then run the tests themselves! Big companies can afford separate quality–assurance teams, but many small firms go without. Even in large companies, code that seems to work properly is frequently not tested for lurking security flaws, because manual testing by other humans is incredibly expensive—sometimes more expensive than writing the original software, given that testing can reveal problems the developers then have to fix. Such flaws are sometimes called “technical debt,” since they are engineering costs borrowed against the future in the interest of shipping code now.

The solution is to establish software building codes and enforce those codes with an army of unpaid inspectors.

Crucially, those unpaid inspectors should not be people, or at least not only people. Some advocates of open-source software subscribe to the “many eyes” theory of software development: that if a piece of code is looked at by enough people, the security vulnerabilities will be found. Unfortunately, Heartbleed shows the fallacy in this argument: though OpenSSL is one of the most widely used open-source security programs, it took paid security engineers at Google and the Finnish IT security firm Codenomicon to find the bug—and they didn’t find it until two years after many eyes on the Internet first got access to the code.

Instead, this army of software building inspectors should be software development tools—the programs that developers use to create programs. These tools can needle, prod, and cajole programmers to do the right thing.

This has happened before. For example, back in 1988 the primary infection vector for the world’s first Internet worm was another program written in C. It used a function called “gets()” that was common at the time but is inherently insecure. After the worm was unleashed, the engineers who maintained the core libraries of the Unix operating system (which is now used by Linux and Mac OS) modified the gets() function to make it print the message “Warning: this program uses gets(), which is unsafe.” Soon afterward, developers everywhere removed gets() from their programs.

The same sort of approach can be used to prevent future bugs. Today many software development tools can analyze programs and warn of stylistic sloppiness (such as the use of a “goto” statement), memory bugs (such as the “use after free” flaw), or code that doesn’t follow established good-programming standards. Often, though, such warnings are disabled by default because many of them can be merely annoying: they require that code be rewritten and cleaned up with no corresponding improvement in security. Other bug–finding tools aren’t even included in standard development tool sets but must instead be separately downloaded, installed, and run. As a result, many developers don’t even know about them, let alone use them.

To make the Internet safer, the most stringent checking will need to be enabled by default. This will cause programmers to write better code from the beginning. And because program analysis tools work better with modern languages like C# and Java and less well with programs written in C, programmers should avoid starting new projects in C or C++—just as it is unwise to start construction projects using old-fashioned building materials and techniques.

Programmers are only human, and everybody makes mistakes. Software companies need to accept this fact and make bugs easier to prevent.

Simson L. Garfinkel is a contributing editor to MIT Technology Review and a professor of computer science at the Naval Postgraduate School.

Sunday, December 14. 2014

Via iiclouds.org

-----

The third workshop we ran in the frame of I&IC with our guest researcher Matthew Plummer-Fernandez (Goldsmiths University) and the 2nd & 3rd year students (Ba) in Media & Interaction Design (ECAL) ended last Friday (| rblg note: on the 21st of Nov.) with interesting results. The workshop focused on small situated computing technologies that could collect, aggregate and/or “manipulate” data in automated ways (bots) and which would certainly need to heavily rely on cloud technologies due to their low storage and computing capacities. So to say “networked data objects” that will soon become very common, thanks to cheap new small computing devices (i.e. Raspberry Pis for diy applications) or sensors (i.e. Arduino, etc.) The title of the workshop was “Botcave”, which objective was explained by Matthew in a previous post.

The choice of this context of work was defined accordingly to our overall research objective, even though we knew that it wouldn’t address directly the “cloud computing” apparatus — something we learned to be a difficult approachduring the second workshop –, but that it would nonetheless question its interfaces and the way we experience the whole service. Especially the evolution of this apparatus through new types of everyday interactions and data generation.

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez (#Algopop) during the final presentation at the end of the research workshop.

Through this workshop, Matthew and the students definitely raised the following points and questions:

1° Small situated technologies that will soon spread everywhere will become heavy users of cloud based computing and data storage, as they have low storage and computing capacities. While they might just use and manipulate existing data (like some of the workshop projects — i.e. #Good vs. #Evil or Moody Printer) they will altogether and mainly also contribute to produce extra large additional quantities of them (i.e. Robinson Miner). Yet, the amount of meaningful data to be “pushed” and “treated” in the cloud remains a big question mark, as there will be (too) huge amounts of such data –Lucien will probably post something later about this subject: “fog computing“–, this might end up with the need for interdisciplinary teams to rethink cloud architectures.

2° Stored data are becoming “alive” or significant only when “manipulated”. It can be done by “analog users” of course, but in general it is now rather operated by rules and algorithms of different sorts (in the frame of this workshop: automated bots). Are these rules “situated” as well and possibly context aware (context intelligent) –i.e.Robinson Miner? Or are they somehow more abstract and located anywhere in the cloud? Both?

3° These “Networked Data Objects” (and soon “Network Data Everything”) will contribute to “babelize” users interactions and interfaces in all directions, paving the way for new types of combinations and experiences (creolization processes) — i.e. The Beast, The Like Hotline, Simon Coins, The Wifi Cracker could be considered as starting phases of such processes–. Cloud interfaces and computing will then become everyday “things” and when at “house”, new domestic objects with which we’ll have totally different interactions (this last point must still be discussed though as domesticity might not exist anymore according to Space Caviar).

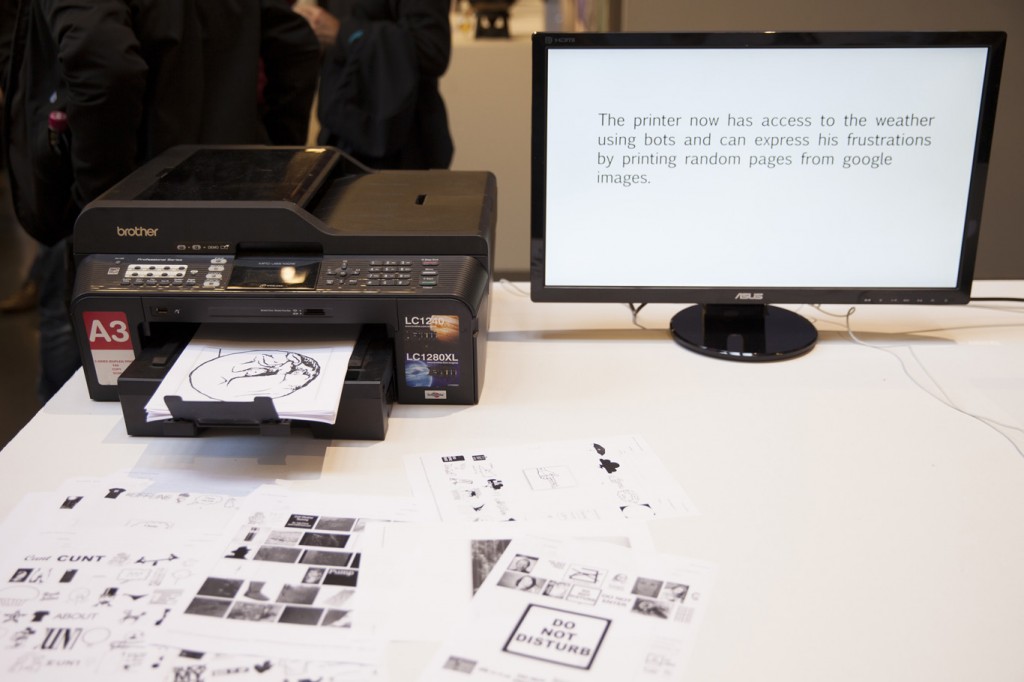

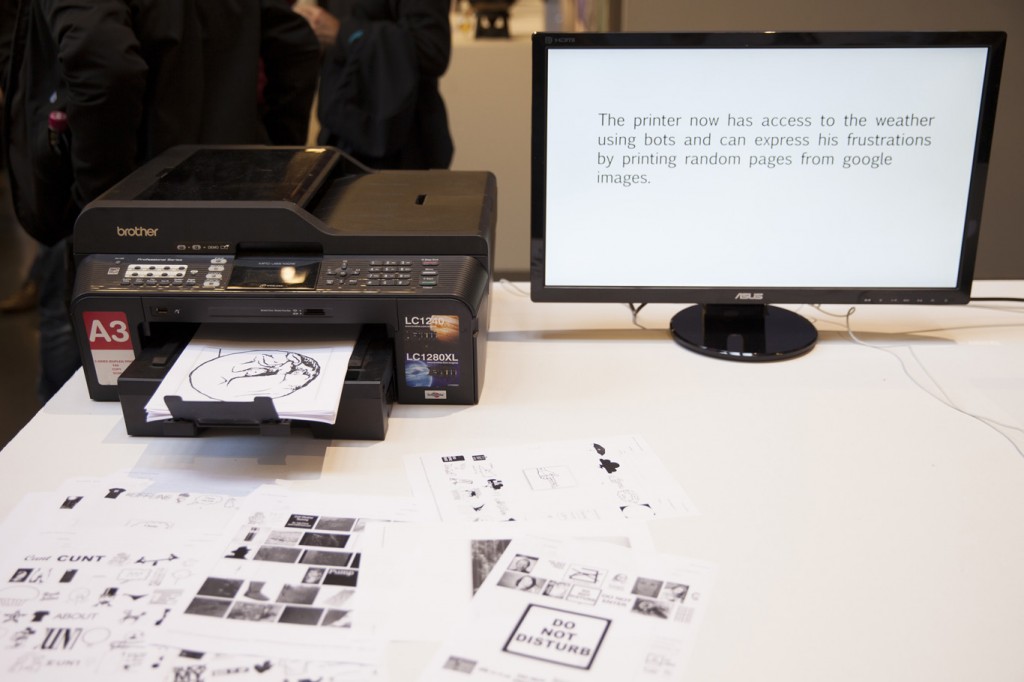

Moody Printer – (Alexia Léchot, Benjamin Botros)

Moody Printer remains a basic conceptual proposal at this stage, where a hacked printer, connected to a Raspberry Pi that stays hidden (it would be located inside the printer), has access to weather information. Similarly to human beings, its “mood” can be affected by such inputs following some basic rules (good – bad, hot – cold, sunny – cloudy -rainy, etc.) The automated process then search for Google images according to its defined “mood” (direct link between “mood”, weather conditions and exhaustive list of words) and then autonomously start to print them.

A different kind of printer combined with weather monitoring.

The Beast – (Nicolas Nahornyj)

Top: Nicolas Nahornyj is presenting his project to the assembly. Bottom: the laptop and “the beast”.

The Beast is a device that asks to be fed with money at random times… It is your new laptop companion. To calm it down for a while, you must insert a coin in the slot provided for that purpose. If you don’t comply, not only will it continue to ask for money in a more frequent basis, but it will also randomly pick up an image that lie around on your hard drive, post it on a popular social network (i.e. Facebook, Pinterest, etc.) and then erase this image on your local disk. Slowly, The Beast will remove all images from your hard drive and post them online…

A different kind of slot machine combined with private files stealing.

Robinson – (Anne-Sophie Bazard, Jonas Lacôte, Pierre-Xavier Puissant)

Top: Pierre-Xavier Puissant is looking at the autonomous “minecrafting” of his bot. Bottom: the proposed bot container that take on the idea of cubic construction. It could be placed in your garden, in one of your room, then in your fridge, etc.

Robinson automates the procedural construction of MineCraft environments. To do so, the bot uses local weather information that is monitored by a weather sensor located inside the cubic box, attached to a Raspberry Pi located within the box as well. This sensor is looking for changes in temperature, humidity, etc. that then serve to change the building blocks and rules of constructions inside MineCraft (put your cube inside your fridge and it will start to build icy blocks, put it in a wet environment and it will construct with grass, etc.)

A different kind of thermometer combined with a construction game.

Note: Matthew Plummer-Fernandez also produced two (auto)MineCraft bots during the week of workshop. The first one is building environment according to fluctuations in the course of different market indexes while the second one is trying to build “shapes” to escape this first envirnment. These two bots are downloadable from theGithub repository that was realized during the workshop.

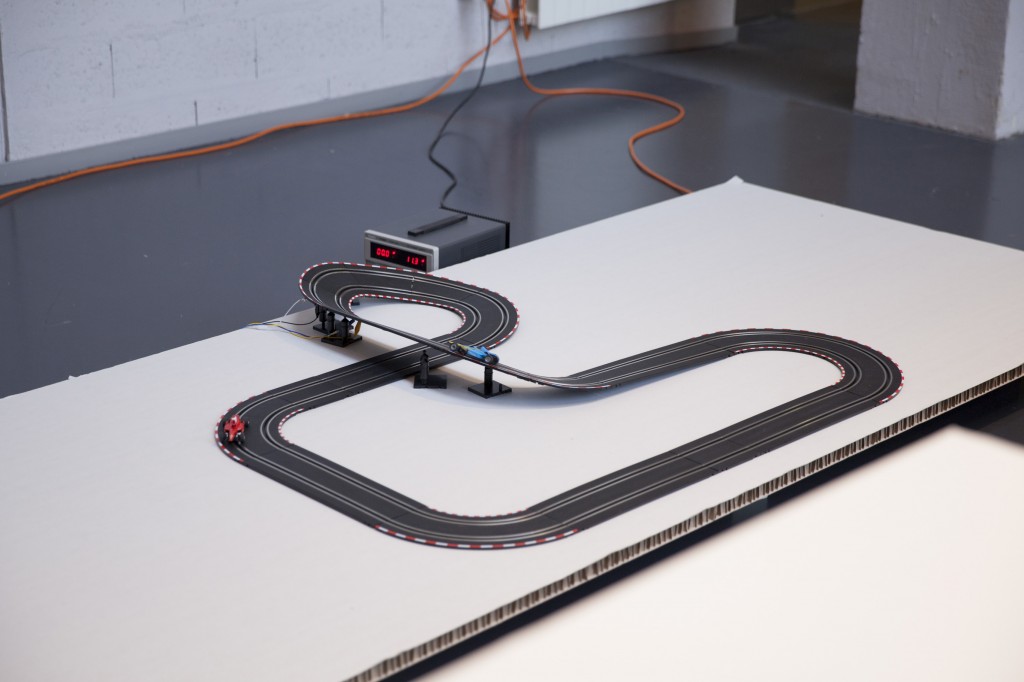

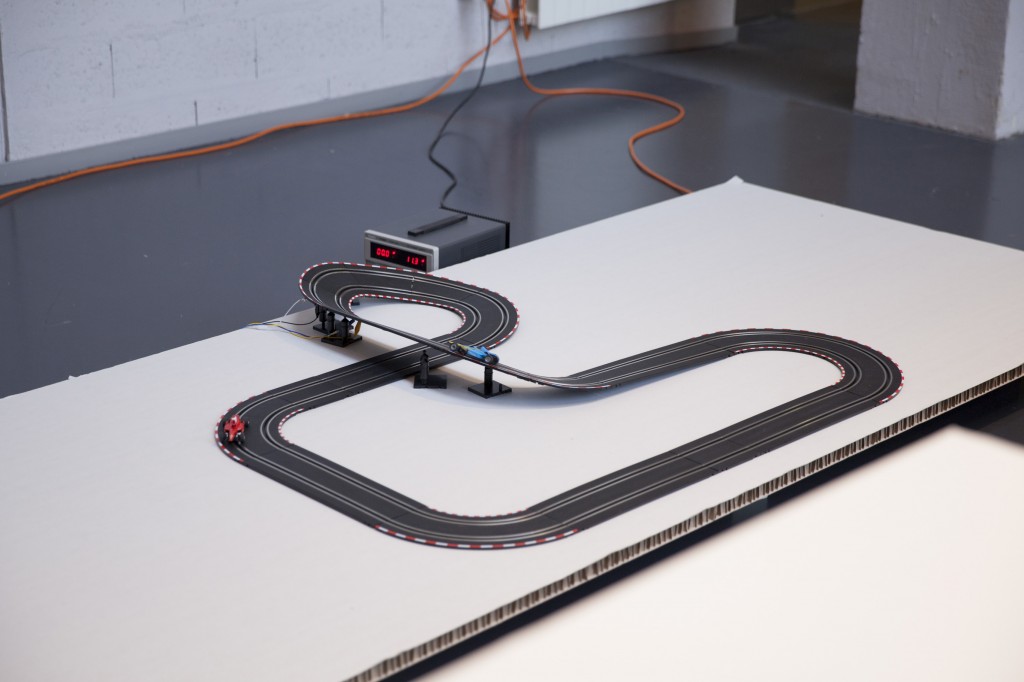

#Good vs. #Evil – (Maxime Castelli)

Top: a transformed car racing game. Bottom: a race is going on between two Twitter hashtags, materialized by two cars.

#Good vs. #Evil is a quite straightforward project. It is also a hack of an existing two racing cars game. Yet in this case, the bot is counting iterations of two hashtags on Twitter: #Good and #Evil. At each new iteration of one or the other word, the device gives an electric input to its associated car. The result is a slow and perpetual race car between “good” and “evil” through their online hashtags iterations.

A different kind of data visualization combined with racing cars.

The “Like” Hotline – (Mylène Dreyer, Caroline Buttet, Guillaume Cerdeira)

Top: Caroline Buttet and Mylène Dreyer are explaining their project. The screen of the laptop, which is a Facebook account is beamed on the left outer part of the image. Bottom: Caroline Buttet is using a hacked phone to “like” pages.

The “Like” Hotline is proposing to hack a regular phone and install a hotline bot on it. Connected to its online Facebook account that follows a few personalities and the posts they are making, the bot ask questions to the interlocutor which can then be answered by using the keypad on the phone. After navigating through a few choices, the bot hotline help you like a post on the social network.

A different kind of hotline combined with a social network.

Simoncoin – (Romain Cazier)

Top: Romain Cazier introducing its “coin” project. Bottom: the device combines an old “Simon” memory game with the production of digital coins.

Simoncoin was unfortunately not finished at the end of the week of workshop but was thought out in force details that would be too long to explain in this short presentation. Yet the main idea was to use the game logic of Simon to generate coins. In a parallel to the Bitcoins that are harder and harder to mill, Simon Coins are also more and more difficult to generate due to the game logic.

Another different kind of money combined with a memory game.

The Wifi Cracker – (Bastien Girshig, Martin Hertig)

Top: Bastien Girshig and Martin Hertig (left of Matthew Plummer-Fernandez) presenting. Middle and Bottom: the wifi password cracker slowly diplays the letters of the wifi password.

The Wifi Cracker is an object that you can independently leave in a space. It furtively looks a little bit like a clock, but it won’t display the time. Instead, it will look for available wifi networks in the area and start try to find their protected password (Bastien and Martin found a ready made process for that). The bot will test all possible combinations and it will take time. Once the device will have found the working password, it will use its round display to transmit the password. Letter by letter and slowly as well.

A different kind of cookoo clock combined with a password cracker.

Acknowledgments:

Lots of thanks to Matthew Plummer-Fernandez for its involvement and great workshop direction; Lucien Langton for its involvment, technical digging into Raspberry Pis, pictures and documentation; Nicolas Nova and Charles Chalas (from HEAD) so as Christophe Guignard, Christian Babski and Alain Bellet for taking part or helping during the final presentation. A special thanks to the students from ECAL involved in the project and the energy they’ve put into it: Anne-Sophie Bazard, Benjamin Botros, Maxime Castelli, Romain Cazier, Guillaume Cerdeira, Mylène Dreyer, Bastien Girshig, Jonas Lacôte, Alexia Léchot, Nicolas Nahornyj, Pierre-Xavier Puissant.

From left to right: Bastien Girshig, Martin Hertig (The Wifi Cracker project), Nicolas Nova, Matthew Plummer-Fernandez (#Algopop), a “mystery girl”, Christian Babski (in the background), Patrick Keller, Sebastian Vargas, Pierre Xavier-Puissant (Robinson Miner), Alain Bellet and Lucien Langton (taking the pictures…) during the final presentation on Friday.

Wednesday, October 01. 2014

Note: will the term "architect" be definitely overtaken by computer scientists? (rather the term "urbanist" in fact in this precise case, but still...). Will our environments be fully controlled by protocols, data sensing, bots and algorithms? Possibly... but who will design them? It makes me think that at one point, the music industry didn't think that their business would change so dramatically. We all know what happened but the good news is: we still need musicians!

So, I probably believe that architects and the schools that form them should look carefully to what is about to happen (the now already famous -- but still to come -- "Internet of Everything"). New actors (in the building industry) are pushing hard for their place in this "still to come" field that include the construction, monitoring and control of cities, territories, buildings, houses, ... (IBM, Cisco, Google, Apple, etc.). Their hidden lines of code will become much more significant for the life of urban citizens (because of their increasing impact on "the way life goes") than any "new" 3d shape you can possibly imagine. Shape is over, code is coming in a street near you!

Via The Verge

-----

The world's got problems and the Google CEO is searching for solutions

By Vlad Savov

As if self-driving cars, balloon-carried internet, or the eradication of death weren't ambitious enough projects, Google CEO Larry Page has apparently been working behind the scenes to set up even bolder tasks for his company. The Information reports that Page started up a Google 2.0 project inside the company a year ago to look at the big challenges facing humanity and the ways Google can overcome them. Among the grand-scale plans discussed were Page's desire to build a more efficient airport as well as a model city. To progress these ideas to fruition, the Google chief has also apparently proposed a second research and development lab, called Google Y, to focus on even longer-term programs that the current Google X, which looks to support future technology and is headed up by his close ally Sergey Brin.

More about it HERE.

Monday, July 14. 2014

Note: it looks like many products we are using today were envisioned a long time ago (peak of expectations vs plateau)... back in the early years of personal computing (80ies). It funnily almost look like a lost utopian-future. Now that we are moving from personal computing to (personal) cloud computing (where personal must be framed into brackets, but should necessarily be a goal), we can possibly see how far personal computing was a utopian move rooted into the protest and experimental ideologies of the late 60ies and 70ies. So was the Internet in the mid 90ies. And now, what?

Via The Verge

-----

By Jacob Kastrenakes

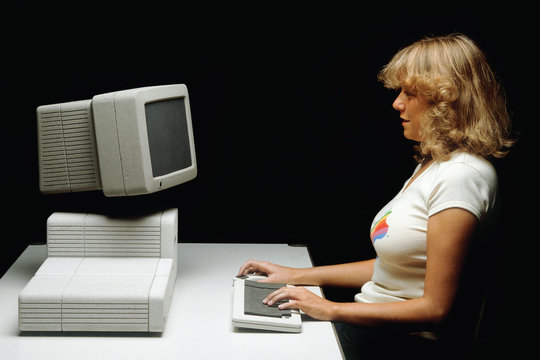

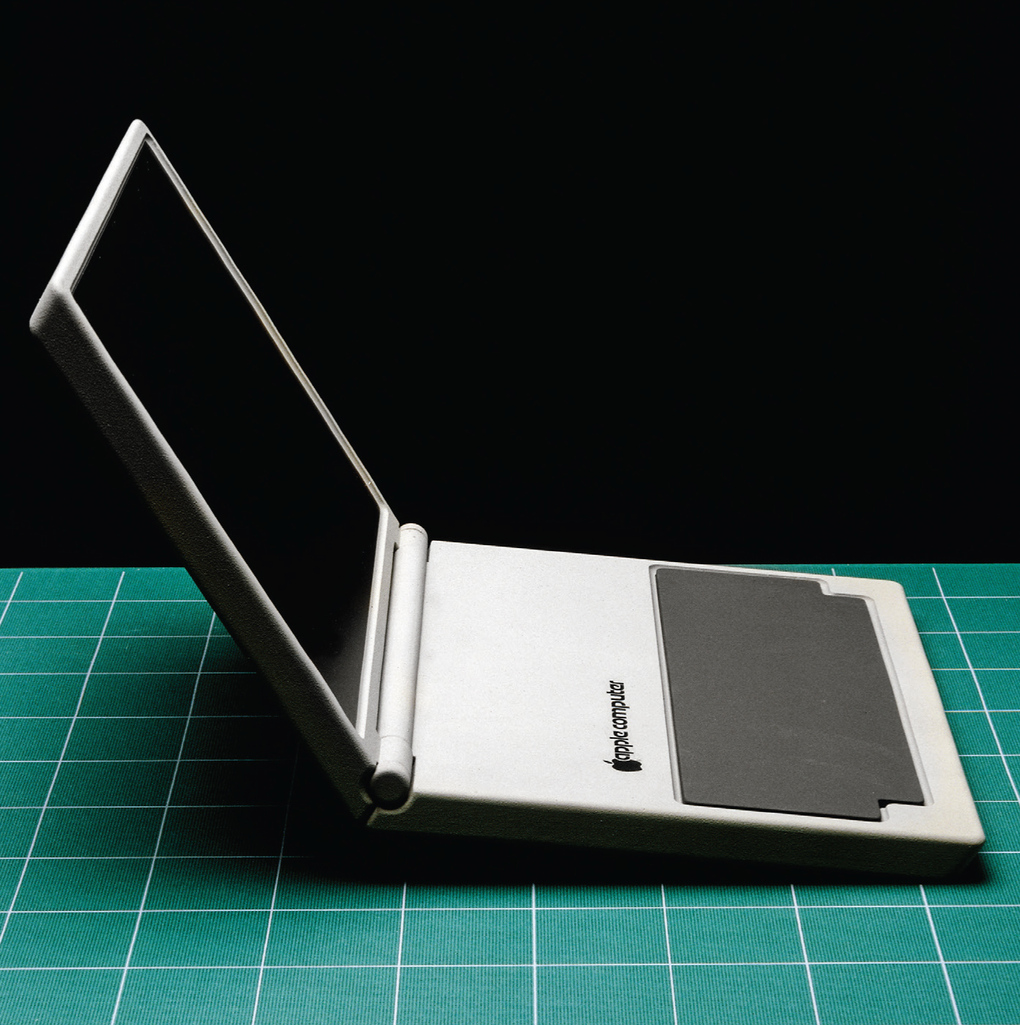

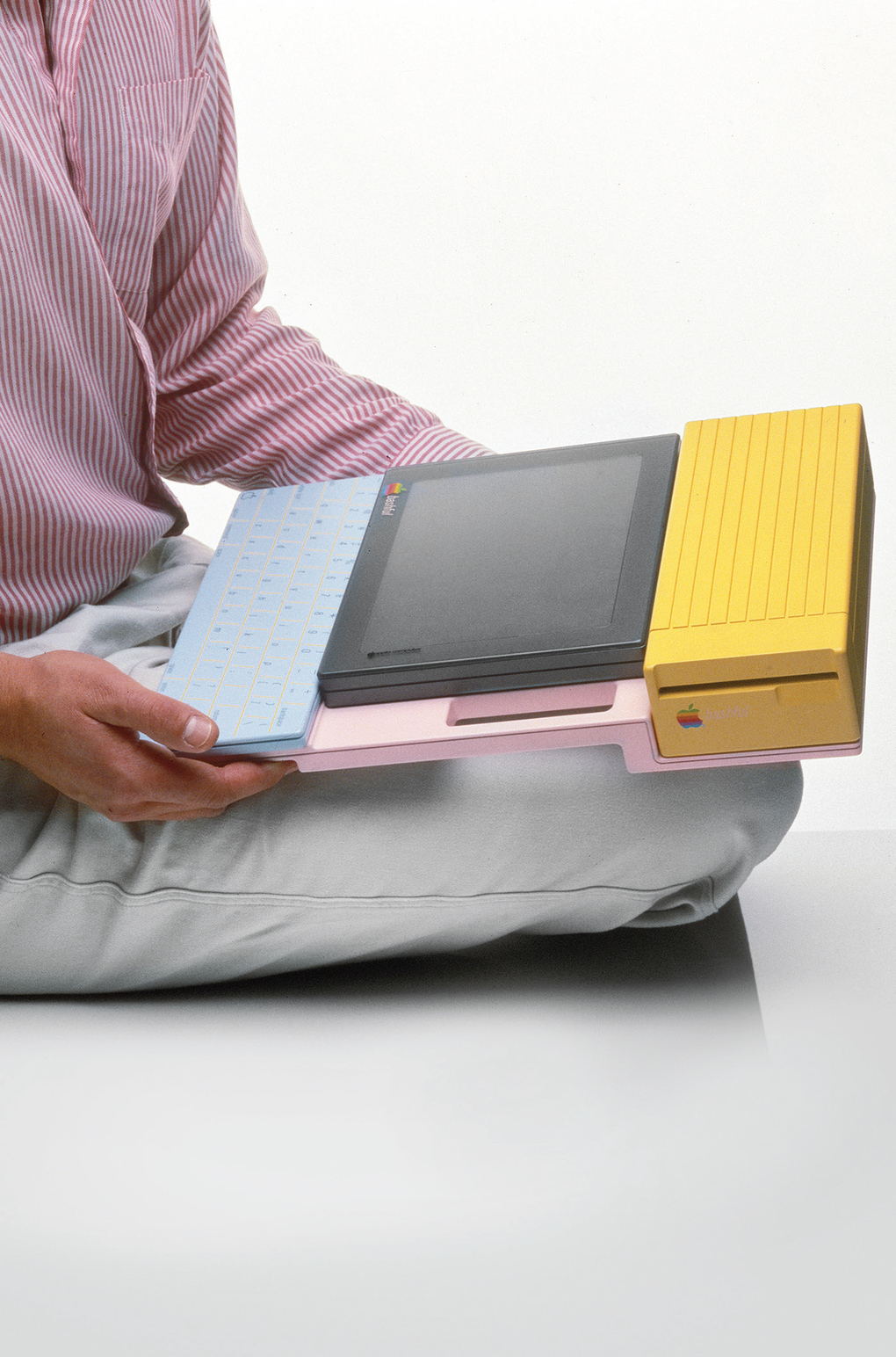

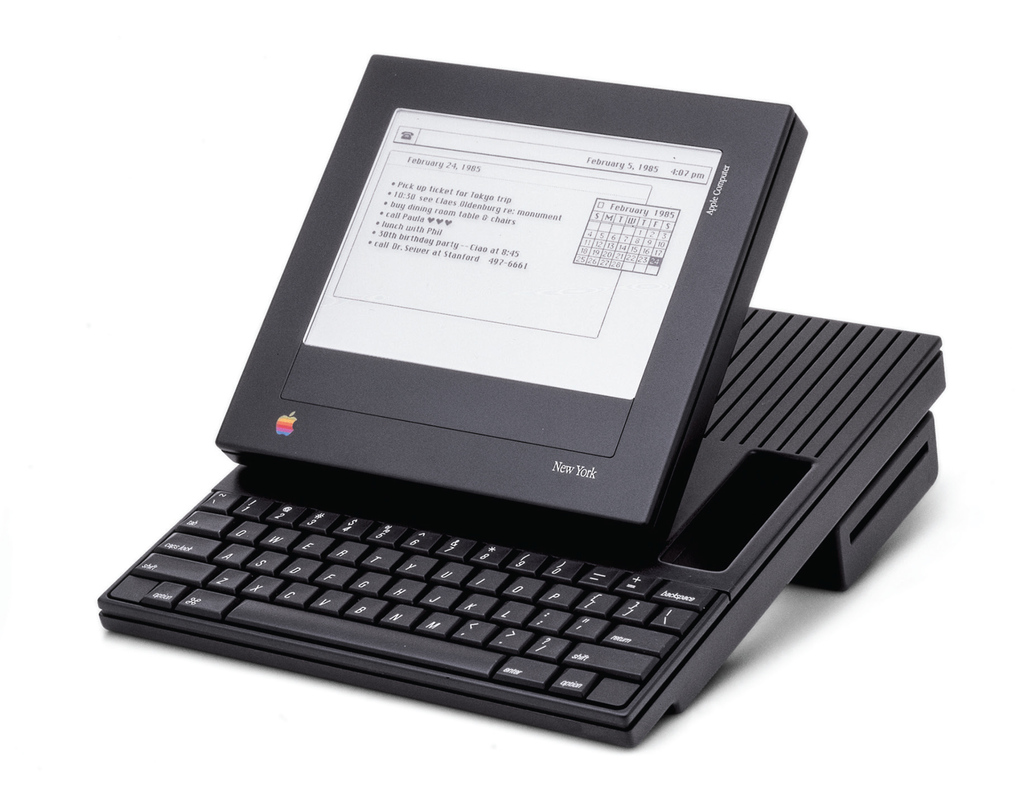

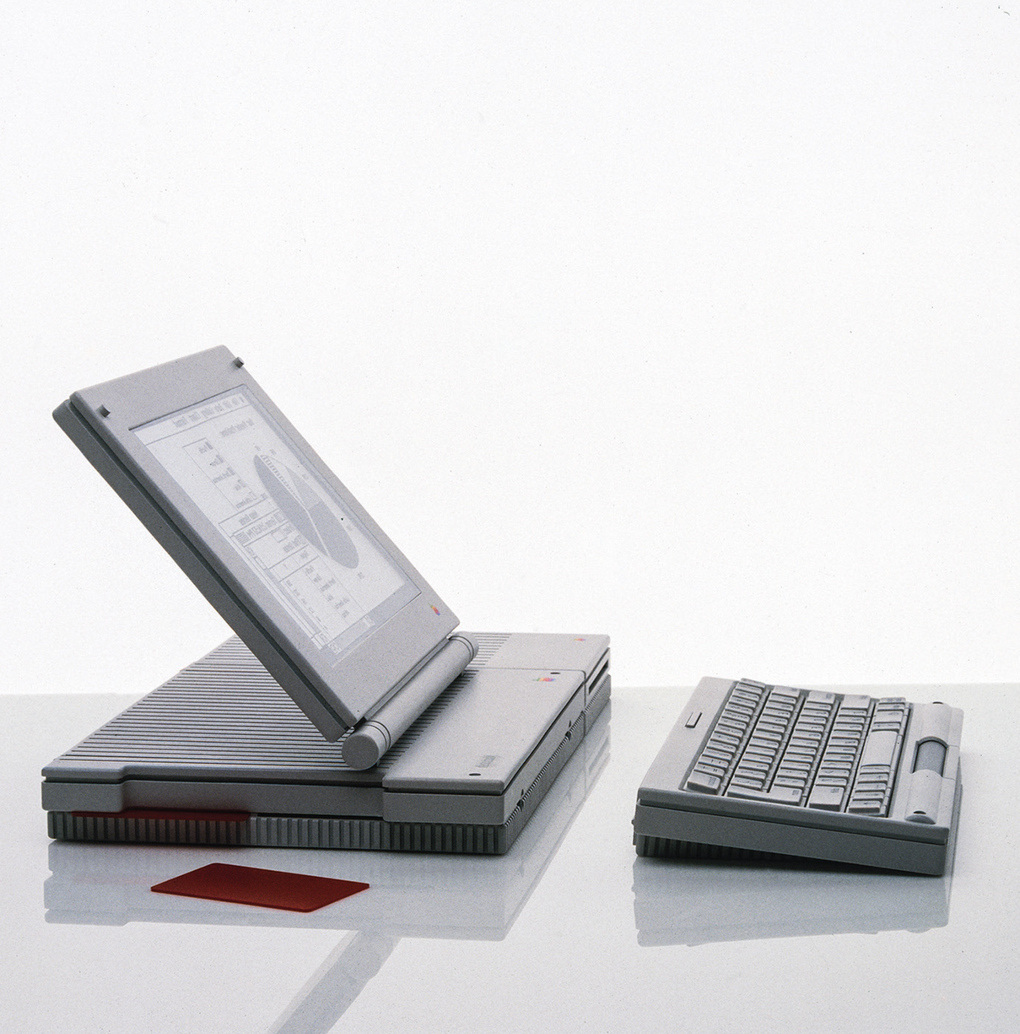

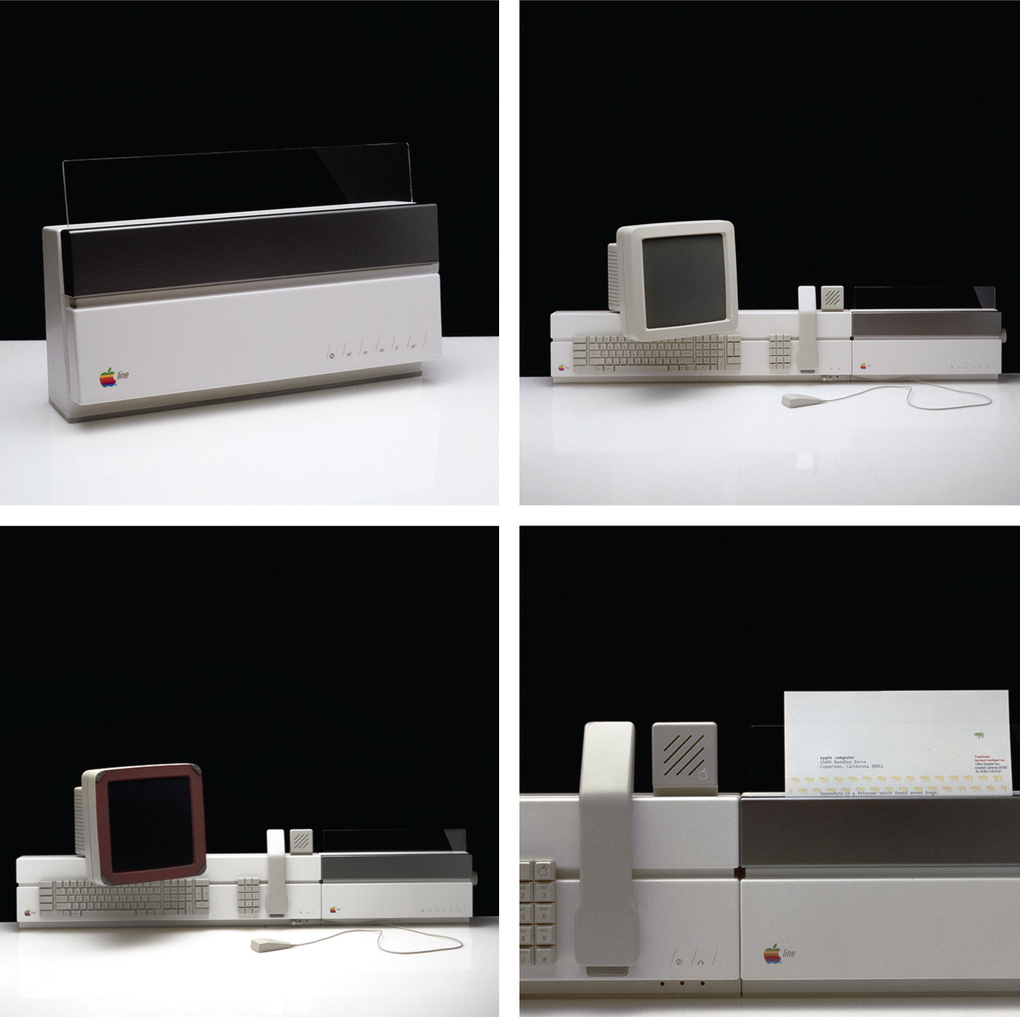

Apple's focus on design has long been one of the key factors that set its computers apart. Some of its earliest and most iconic designs, however, didn't actually come from inside of Apple, but from outside designers at Frog. In particular, credit goes to Frog's founder, Hartmut Esslinger, who was responsible for the "Snow White" design language that had Apple computers of the ’80s colored all white and covered in long stripes and rounded corners meant to make the machines appear smaller.

In fact, Esslinger goes so far as to say in his recent book, Keep it Simple, that he was the one who taught Steve Jobs to put design first. First published late last year, the book recounts Esslinger's famous collaboration with Jobs, and it includes amazing photos of some of the many, many prototypes to come out of it. They're incredibly wide ranging, from familiar-looking computers to bizarre tablets to an early phone and even a watch, of sorts.

This is far from the first time that Esslinger has shared early concepts from Apple, but these show not only a variety of styles for computers but also a variety of forms for them. Some of the mockups still look sleek and stylish today, but few resemble the reality of the tablets, laptops, and phones that Apple would actually come to make two decades later, after Jobs' return. You can see more than a dozen of these early concepts below, and even more are on display in Esslinger's book.

Wednesday, April 02. 2014

Meanwhile ...

Makes me think about this interview with Bill Gates about software substitution.

Via algopop (via Reuters)

-----

Computers dethrone humans in European stock trading - via reuters

European equity investors are placing more orders via computers than through human traders for the first time as new market rules drive more money managers to go high-tech and low cost. The widespread regulatory changes has made electronic trading spread across the industry.

Last year, European investors put 51 percent of their orders through computers directly connected to the stock exchange or by using algorithms, a study by consultants TABB showed. The TABB study revealed that of 58 fund managers controlling 14.6 trillion euros in assets, a majority intended to funnel much more of their business through electronic “low touch” channels, which can cut trade costs by two-thirds. Pioneer Investments, which trades 500 billion euros ($695 billion) worth of assets every year and has cut the number of brokers it uses from 300 to around 100. Thats a lot of money in the non-hands of algorithms.

Friday, February 28. 2014

It looks like managing a "smart" city is similar to a moon mission! IBM Intelligent Operations Center in Rio de Janeiro.

Via Metropolis

-----

IBM, INTELLIGENT OPERATIONS CENTER, RIO DE JANEIRO

At the Intelligent Operations Center in Rio, workers manage the city from behind a giant wall of screens, which beam them data on how the city is doing— from the level of water in a street following a rainstorm to a recent mugging or a developing traffic jam. As the home to both the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics, the city hopes to prove it can be in control of itself, even under pressure. And IBM hopes to prove the power of its new Smarter Cities software to a global audience.

And an intersting post, long and detailed (including regarding recent IBM, CISCO, Siemens "solutions" and operations), about smart cities in the same article, by Alex Marshall:

"The smart-city movement spreading around the globe raises serious concerns about who controls the information, and for what purpose."

More about it HERE.

Wednesday, February 26. 2014

Three years ago we published a post by Nicolas Nova about Salvator Allende's project Cybersyn. A trial to build a cybernetic society (including feedbacks from the chilean population) back in the early 70ies.

Here is another article and picture piece about this amazing projetc on Frieze. You'll need to buy the magazione to see the pictures, though!

-----

Via Frieze

Phograph of Cybersyn, Salvador Allende's attempt to create a 'socialist internet, decades ahead of its time'

This is a tantalizing glimpse of a world that could have been our world. What we are looking at is the heart of the Cybersyn system, created for Salvador Allende’s socialist Chilean government by the British cybernetician Stafford Beer. Beer’s ambition was to ‘implant an electronic nervous system’ into Chile. With its network of telex machines and other communication devices, Cybersyn was to be – in the words of Andy Beckett, author of Pinochet in Piccadilly (2003) – a ‘socialist internet, decades ahead of its time’.

Capitalist propagandists claimed that this was a Big Brother-style surveillance system, but the aim was exactly the opposite: Beer and Allende wanted a network that would allow workers unprecedented levels of control over their own lives. Instead of commanding from on high, the government would be able to respond to up-to-the-minute information coming from factories. Yet Cybersyn was envisaged as much more than a system for relaying economic data: it was also hoped that it would eventually allow the population to instantaneously communicate its feelings about decisions the government had taken.

In 1973, General Pinochet’s cia-backed military coup brutally overthrew Allende’s government. The stakes couldn’t have been higher. It wasn’t only that a new model of socialism was defeated in Chile; the defeat immediately cleared the ground for Chile to become the testing-ground for the neoliberal version of capitalism. The military takeover was swiftly followed by the widespread torture and terrorization of Allende’s supporters, alongside a massive programme of privatization and de-regulation. One world was destroyed before it could really be born; another world – the world in which there is no alternative to capitalism, our world, the world of capitalist realism – started to emerge.

There’s an aching poignancy in this image of Cybersyn now, when the pathological effects of communicative capitalism’s always-on cyberblitz are becoming increasingly apparent. Cloaked in a rhetoric of inclusion and participation, semio-capitalism keeps us in a state of permanent anxiety. But Cybersyn reminds us that this is not an inherent feature of communications technology. A whole other use of cybernetic sytems is possible. Perhaps, rather than being some fragment of a lost world, Cybersyn is a glimpse of a future that can still happen.

Monday, February 03. 2014

An interesting call for papers about "algorithmic living" at University of California, Davis.

Via The Programmable City

-----

Call for papers

Thursday and Friday – May 15-16, 2014 at the University of California, Davis

Submission Deadline: March 1, 2014 algorithmiclife (at) gmail.com

As algorithms permeate our lived experience, the boundaries and borderlands of what can and cannot be adapted, translated, or incorporated into algorithmic thinking become a space of contention. The principle of the algorithm, or the specification of the potential space of action, creates the notion of a universal mode of specification of all life, leading to discourses on empowerment, efficiency, openness, and inclusivity. But algorithms are ultimately only able to make intelligible and valuable that which can be discretized, quantified, operationalized, proceduralized, and gamified, and this limited domain makes algorithms necessarily exclusive.

Algorithms increasingly shape our world, our thought, our economy, our political life, and our bodies. The algorithmic response of NSA networks to threatening network activity increasingly brings privacy and political surveillance under algorithmic control. At least 30% of stock trading is now algorithmic and automatic, having already lead to several otherwise inexplicable collapses and booms. Devices such as the Fitbit and the NikeFuel suggest that the body is incomplete without a technological supplement, treating ‘health’ as a quantifiable output dependent on quantifiable inputs. The logic of gamification, which finds increasing traction in educational and pedagogical contexts, asserts that the world is not only renderable as winnable or losable, but is in fact better–i.e. more effective–this way. The increased proliferation of how-to guides, from HGTV and DIY television to the LifeHack website, demonstrate a growing demand for approaching tasks with discrete algorithmic instructions.

This conference seeks to explore both the specific uses of algorithms and algorithmic culture more broadly, including topics such as: gamification, the computational self, data mining and visualization, the politics of algorithms, surveillance, mobile and locative technology, and games for health. While virtually any discipline could have something productive to say about the matter, we are especially seeking contributions from software studies, critical code studies, performance studies, cultural and media studies, anthropology, the humanities, and social sciences, as well as visual art, music, sound studies and performance. Proposals for experimental/hybrid performance-papers and multimedia artworks are especially welcome.

Areas open for exploration include but are not limited to: daily life in algorithmic culture; gamification of education, health, politics, arts, and other social arenas; the life and death of big data and data visualization; identity politics and the quantification of selves, bodies, and populations; algorithm and affect; visual culture of algorithms; algorithmic materiality; governance, regulation, and ethics of algorithms, procedures, and protocols; algorithmic imaginaries in fiction, film, video games, and other media; algorithmic culture and (dis)ability; habit and addiction as biological algorithms; the unrule-able/unruly in the (post)digital age; limits and possibilities of emergence; algorithmic and proto-algorithmic compositional methods (e.g., serialism, Baroque fugue); algorithms and (il)legibility; and the unalgorithmic.

Please send proposals to algorithmiclife (at) gmail.com by March 1, 2014.

Decisions will be made by March 8, 2014.

|