Via ArchDaily

-----

By Eric Baldwin

“The modern architect is designing for the deaf.” Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer makes a valid point. [1] The topic of sound is practically non-existent in modern architectural discourse. Why? We, as architects, think in terms of form and space; we balance scientific understanding and artistic vision. The problem is, we have a tendency to give ample thought to objects rather than processes and systems. Essentially, our field is ocular-centric by nature. So how do we start to “see” sound? And more importantly, how do we use it to promote health, safety and well-being?

So why does designing for our ears matter? Well, even if you happen to find yourself in an anechoic chamber right now, you’re still surrounded by sound. In 1910, a medical doctor by the name of Robert Koch, considered to be the founder of modern bacteriology, stated that: “One day people will have to fight noise just as relentlessly as they fight cholera and plague.” [2] His prediction came true: studies have shown that sound has a direct impact on our educational system, healthcare, and productivity in the workplace. As Julian Treasure states in his enlightening TED talk, “sound affects us physiologically, psychologically, cognitively, and behaviorally, all at the time.” For this reason, sound must be a consideration in the way we design; it is a constant that can dramatically improve or ruin our quality of life.

Meanwhile, the topic of Public Interest Design has gained significant momentum in the past couple years. The keynote speaker at the national AIA convention this year was none other than Cameron Sinclair, the vanguard of service-minded architecture. Teams like MASS Design Group and Sam Mockbee’s Rural Studio have gained international recognition. But taking a glimpse at their magnificent work, one is often left to wonder, did they consider sound? Can sound become a major aspect of Public Interest Design?

Looking at the photo above taken in the Butaro Hospital designed by MASS Design Group, you can easily notice the “big ass fans,” as co-founder Michael Murphy calls them. A major success in the project is the consideration of ventilation, which helps to mitigate transmission of airborne diseases. It is an idea that directly saves lives. But what do those fans sound like? Does the vaulted ceiling increase or decrease the intelligibility of speech? And in turn, do these combined effects decrease hospital personnel accuracy and patient recovery rates? With noise levels in hospitals having doubled in the last 40 years, these are the questions that are becoming more and more relevant – although too frequently left unasked [3]. Perhaps we are afraid of the answers.

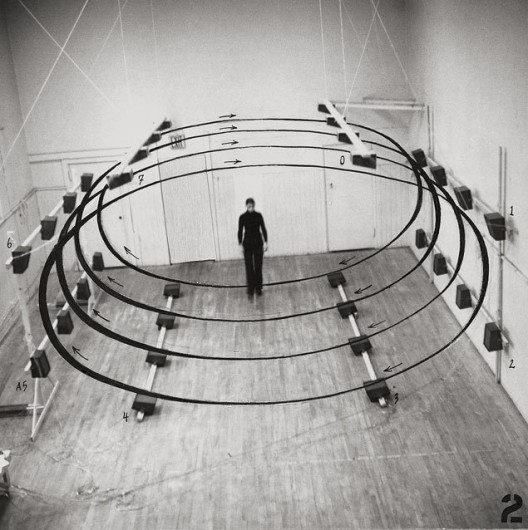

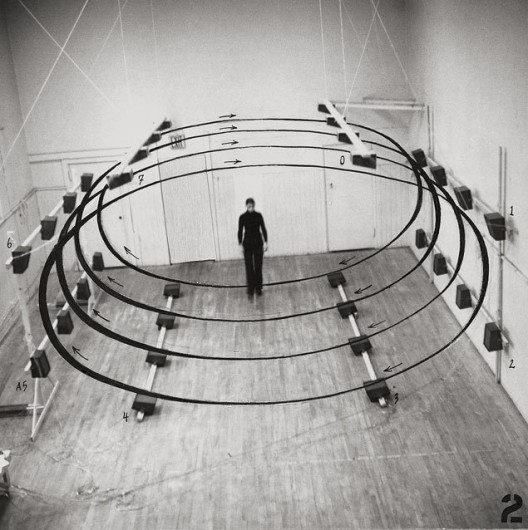

So where do we begin? How can we “see” sound? Louis Roberts, an architect out of California, noted that one way he thinks about a design element like light is by asking “how will natural light pull someone through space?” [4] What we can begin to do is inquire about the nature of sound, and how it can “pull us” through space, as Roberts said. What would happen if we imagine sound as a continual mass, if we as architects design according to the patterns by which sound travels around and through space.

For example, the University of Virginia’s Sound Lounge uses an aural understanding to create “pockets” of conversation and increased intelligibility within a larger space. These same ideas can be adapted to a larger scale, within the context of a city, to tackle the problem of urban noise. Expanding further, LMN Architects are using parametric modeling and digital fabrication in their School of Music project to create an integrated acoustic system where lighting, speakers, and sprinklers are all part of a single ceiling surface. We can imagine facades, streetscapes, and interior spaces in the same manner.

In essence, these are general, minor steps, but it is time for architects to take those first steps and begin to truly listen. Let us design schools where children can better hear their teachers, hospitals where patients can fall sound asleep, and offices where workers can hear themselves think. But first of all, let’s ask ourselves the vital questions of “sound” design, and begin by truly listening to the answers.

References

[1] Robinson, Sarah. Nesting: Body, Dwelling, Mind. Richmond, CA: William Stout, 2011. Print.

[2] Kleilein, Doris. Tuned City: Zwischen Klang- Und Raumspekulation = Between Sound and Space Speculation. Idstein: Kook, 2008. Print.

[3] Work Group 44. Rep. no. 512. ANSI, 21 May 2009

[4] Roberts, Louis O.Man between Earth and Sky: A Symbolic Awareness of Architecture through a Process of Creativity. Carmel, CA: Octavio Pub., 2009. Print.

Making Space Resonate: Incorporating Sound Into Public-Interest Design originally appeared on ArchDaily, the most visited architecture website on 13 Sep 2013.

Personal comment:

I agree with the observation by E. Baldwin, when speaking about architecture, that "Essentially, our field is ocular-centric by nature" (or by design habits?) and therefore architecture is often oriented toward this primary, strong sense. So as most of our designed (visual) environments. Unfortunately I would add.

But I disagree with the idea that we should "see" what is invisible (Baldwin puts the "", so it is of course not trivial "seeing" that he's thinking about I believe), materialize it in the form of images or objects. When it comes to physiological or invisible parts of our livable environment, it is interesting not to necessarily bring them, again, in the visible field, but to also work with invisibility and physiology. To literally architecture them and make them fully part of our projects, sometimes also just as they are.