Via MIT Technology Review

-----

By Howard Rheingold

Computing pioneer Doug Engelbart’s inventions transformed computing, but he intended them to transform humans.

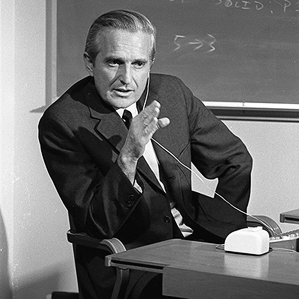

Peripheral vision: Engelbart rehearses for the “mother of all demos.”

Doug Engelbart knew that his obituaries would laud him as “Inventor of the Mouse.” I can see him smiling wistfully, ironically, at the thought. The mouse was such a small part of what Engelbart invented.

We now live in a world where people edit text on screens, command computers by pointing and clicking, communicate via audio-video and screen-sharing, and use hyperlinks to navigate through knowledge—all ideas that Engelbart’s Augmentation Research Center at Stanford Research Institute (SRI) invented in the 1960s. But Engelbart never got support for the larger part of what he wanted to build, even decades later when he finally got recognition for his achievements. When Stanford honored Engelbart with a two-day symposium in 2008, they called it “The Unfinished Revolution.”

To Engelbart, computers, interfaces, and networks were means to a more important end—amplifying human intelligence to help us survive in the world we’ve created. He listed the end results of boosting what he called “collective IQ” in a 1962 paper, Augmenting Human Intellect. They included “more-rapid comprehension … better solutions, and the possibility of finding solutions to problems that before seemed insoluble.” If you want to understand where today’s information technologies came from, and where they might go, the paper still makes good reading.

Engelbart’s vision for more capable humans, enabled by electronic computers, came to him in 1945, after reading inventor and wartime research director Vannevar Bush’s Atlantic Monthly article “As We May Think.” Bush wrote: “The summation of human experience is being expanded at a prodigious rate, and the means we use for threading through the consequent maze to the momentarily important item is the same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships.”

That inspired Engelbart, a young electrical engineer, to come up with the idea of people using screens and computers to collaboratively solve problems. He worked on his ideas for the rest of his life, despite being warned over and over by people in academia and the computer industry that his ideas of using computers for anything other than scientific computations or business data processing was “crazy” and “science fiction.”

Englebart knew right from the start that screens, input devices, hardware, and software could allow the necessary collaborative problem-solving only as part of a system that included cognitive, social, and institutional changes. But he found introducing new ways for people to work together more effectively, the lynchpin of his overall vision, more difficult than transforming the way humans and computers interact.

Engelbart labored for most of his life and career to get anyone to think seriously about his ideas, of which the mouse was an essential but low-level component. Only for one golden decade did he get significant backing. In 1963, the U.S. Defense Department provided the wherewithal for Engelbart to assemble a team, create the future, and blow the mind of every computer designer in the world by way of what has come to be known as “the mother of all demos.”

I first met Engelbart in 1983 in his Cupertino office in a small building that was completely surrounded by the Apple campus. A company that no longer exists, Tymshare, had purchased what was left of Engelbart’s lab and hired him after the Stanford Research Institute stopped supporting the Augmentation Research Center due to the Department of Defense withdrawing funding.

Engelbart noted with dismay that although the personal computer was evolving quickly, the other elements of his plan weren’t. At the time, personal computers weren’t networked to one another—as terminals of large computers could be at the time—and they lacked a mouse or point-and-click interface.

Engelbart told me in our first conversation, as I’m sure he must have told many others, that the computer and mouse were just the “artifacts” in a system that centered on “humans, using language, artifacts, methodology, and training.”

In the late 1980s, Engelbart set up his self-funded “Bootstrap Institute” to try and get his ideas about working more effectively the acceptance his artifacts had. He developed ways of analyzing how people acted inside an organization and specific techniques that he claimed would boost “collective IQ.” A set of detailed presentations on those methodologies started with what he called CODIAK. “Collective IQ is a measure of how effectively a collection of people can concurrently develop, integrate, and apply its knowledge toward its mission,” (emphasis Engelbart’s).

Mouse manufacturer Logitech provided office space, but the Bootstrap Institute – staffed by Engelbart and his daughter Christina—never sold bootstrapping, collective IQ, or CODIAK to any funder, major company, or government department.

Engelbart’s failure to spread the less tangible parts of his vision stems from several circumstances. He was an engineer at heart, and engineers’ utopian solutions don’t always account for the complexities of human social institutions. He only added a social scientist to his lab just before it was shut down.

What’s more, Engelbart’s pitches of linked leaps in technology and organizational behaviors probably sounded as crazy to 1980s corporate managers as augmenting human intellect with machines did in the early 1960s. In the end, the way Silicon Valley companies work changed radically in recent decades not through established companies going through the kind of internal transformations Engelbart imagined, but by their being displaced by radical new startups.

When I talked with him again in the mid-2000s, Engelbart marveled that people carry around in their pockets millions of times more computer power than his entire lab had in the 1960s, but the less tangible parts of his system had still not evolved so spectacularly.

Like Tim Berners-Lee, Engelbart never sought to own what he contributed to the world’s ability to know. But he was frustrated to the end by the way so many people had adopted, developed, and profited from the digital media he had helped create, while failing to pursue the important tasks he had created them to do.

Howard Rheingold, a visiting lecturer at Stanford University, has written since the early 1980s about how innovations in computers and networking change peoples’ thinking. He profiled Doug Engelbart’s work in his 1985 book, Tools for Thought and is most recently author of Net Smart: How to Thrive Online.