Tuesday, November 22. 2011

Via The Guardian via WMMNA

-----

Going to waste … Philips is bringing methane back in the kitchen design for its new Microbial Home, which features a bio-digester (centre)

"(...)

But if Bulthaup is modernism taken to its logical extreme, what if everything modernism taught us about the kitchen is wrong? What if bacteria and manual labour are the future of the kitchen? Philips recently unveiled a concept kitchen as part of its Microbial Home system, in which the central component is a bio-digester kitchen island. The idea is simple: bacteria digests food and toilet waste and turns it into methane gas for cooking and lighting. It's a self-sustaining domestic ecosystem, and it presents an alternative vision to the clinical kitchen, inviting the microbes and the rotting vegetable peel back in.

(...)"

More about it on The Guardian.

Personal comment:

An interesting and funny article by Justin McGuirck about modernism, Orwell, Reyner Banham and... the kitchen!

Tuesday, November 08. 2011

Via WMMNA

-----

Taken out from a post (Lemonade Igloo, salt deserts and other landscape wonders) by Régine Debatty about the work of photographer Scarlett Hooft Gaafland on WMMNA, this lemonade house make me think of houses that you could eventually drink before you move... providing the inhabitant with some sort of "house" nutrient...

As a reminder as well of some vernacular, farm type of architectures in the Alps, when in winter everything was in close(d) circuitry: the animals --mostly cows-- were living in the lower level of the house producing heat for the inhabitants, while also producing food. Inhabitants, animals and architecture were in a sort of symbiotic relationship.

Lemonade Igloo, Igloolik Series, Arctic Canada, 2007-2008

Friday, March 11. 2011

Via GOOD

-----

from GOOD by Nicola Twilley

Three-dimensional printers are getting a lot of hype at the moment. In February, MakerBot Industries started shipping its Thing-o-Matic desktop 3D printer, which, at just $1,225, "democratizes" 3D printing, allowing you to "live in the cutting-edge personal manufacturing future of tomorrow!" The same month, the typically restrained Economist headlined a story "Print me a Stradivarius: How a New Manufacturing Technology Will Change the World." Business Insider even called it "The Next Trillion Dollar Industry."

The idea, for those of you who aren't familiar with it, is pretty simple. You create a 3D design on your computer or download a premade blueprint. Then you press print. Your printer squirts materials out of a nozzle that is sort of like an ink jet printhead, and builds up the object gradually, one layer at a time. When it finishes and the object has cooled, you have a new thing. Not a picture of a thing, but the thing itself.

And people are already using the technology to print all sorts of things—pesticide-free plastic bug repellents, new ears, and videogame cars.

They're also printing food.

For example, both the BBC and the CBC have recently reported on the 3D food printer being tested at Cornell University's Computational Synthesis Lab (CCSL). So far, the team there have created miniature space shuttles made out of ground scallops and melted cheese, chocolate letters, and cubes of raw turkey and celery, mixed with hydrocolloids to create a gel.

Meanwhile, across the pond, tech company Bits from Bytes are collaborating with the University of the West of England to try to print mashed potatoes.

The somewhat underwhelming aesthetic results of these experiments do not discourage 3D food printing's proponents, who dream of the chance to rapidly prototype and tweak new flavor and texture combinations, the ability to digitally control nutrient intake and ensure food safety, and the possibility that, one day, your mom will be able to send you a slice of her apple pie over email. And, undoubtedly, if 3D food printers become as ubiquitous as personal computers, it will utterly change the way we think about food, as well as reshape the built environment, from kitchen design to supermarket layout.

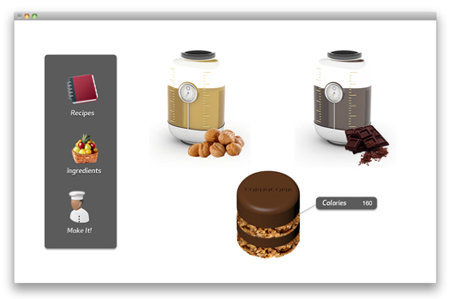

To find out more about how these 3D food printers actually work and how they might change our lives, I talked to Marcelo Coelho, an industrial designer with MIT Media Lab's Fluid Interfaces Group. Last year, he and Amit Zoran released a series of concept drawings for a digital gastronomy project they called Cornucopia. Now, Coelho has created a prototype digital chocolatier—a personal, 3D candy printer. Our conversation is below.

GOOD: The last time we talked, in February 2010, you had come up with these concept drawings. Can you talk through the process of turning them into a working prototype.

Coelho: We started by looking at what was possible using real world technology. The biggest challenge in making a 3D food printer is controlling the food. We experimented with different types of ingredients and with different kinds of valve design. I’m definitely not a food engineer, so I went through a whole process of getting a better sense of the properties of the foodstuffs that I was working with and what sorts of devices have been invented to work with each of them on the industrial scale. I looked at a lot of books about the design of machines for food factories.

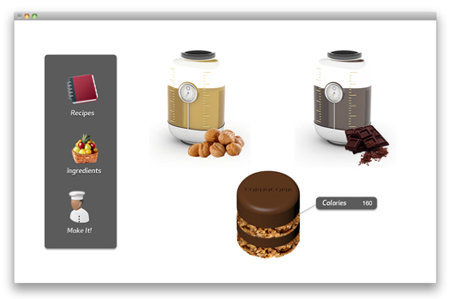

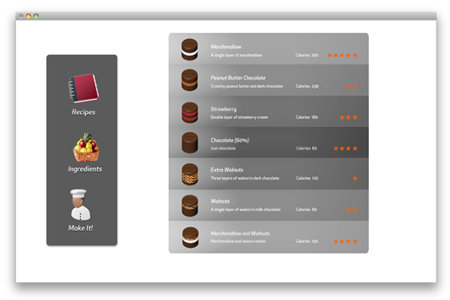

Eventually, I arrived at a prototype that combined chocolate and nuts in different amounts. The machine has a little carousel with two different types of chocolate and two different types of nuts—just regular chocolate, white chocolate, almonds, and walnuts, bought from a store. I designed a graphical user interface so you can just click on the food that you want and it gets added to the design. So, for example, you might click on the chocolate and a tiny little bit of chocolate gets added to that candy design. Then you might do a layer of nuts, and you keep selecting the amount and the arrangement of those layers. When you're done, you just hit the candy button, and the machine goes through the process of printing it out.

I really tried to show what happened while the machine was making the candy, so as the machine starts to extrude the chocolate and the walnuts, the graphic representation of the candy on the user interface also shows what’s happening—you see the layers appearing on the virtual candy as it's appearing on the physical candy. I think that's an important part of the process, so that people could see how the food is coming to be what it is.

GOOD: So do you actually have to design the whole candy before it even starts printing?

Coelho: No, you can do as much as you want, and then just hit the candy button and whatever you've created so far will get printed.

GOOD: That's good, because I can easily see how you would design something that looks good and then as it prints, realize, you know what, I want a little bit more chocolate…

Coelho: Absolutely. So you could print two layers of chocolate, stop and then put a marshmellow in the middle of this thing by hand and then print some more layers of chocolate and nuts. I think creating this symbiosis between the machine and the people using it is very important.

GOOD: When other people tested the prototype and printed candy for themselves, did they do things that you weren’t expecting with it?

Coelho: I think the most surprising things was how much people liked their candies. They tasted really good. I was a bit surprised. I don’t know why, because we used good chocolate and real nuts and we were just depositing them in different ways, but I thought the candy was going to taste funny. I also think people were just fascinated by the idea of making candy. There’s a lot of creative space in candy design.

GOOD: One practical question: How do you keep the chocolate at the right temperature so it can extrude? Do you add something to the mix, or is it just melted chocolate?

Coelho: It’s melted chocolate, and there’s a hidden film that goes in the chocolate tube with a heating element and a thermostat, so you can heat it and then keep it at a steady temperature. The heating is more localized at the bottom, near the valve.

GOOD: How do you top it up?

Coelho: You just buy a bag of chocolate chips from the grocery store and tip it into the tube.

GOOD: Given that this is a prototype, what are some of the things you would need to refine before production?

Coelho: There are a few things. Right now, it takes about a minute for the candy to harden. We could speed that up by putting the entire machine inside a little chamber, for better temperature control. Another thing is that over time the valves start getting clogged and you have to take the whole thing apart. I would like it to be super easy to detach the valves and just pop them into the dishwasher. But each of these things is a separate and really hard design challenge.

It does work pretty well, but the next step is to build it so it works reliably for a long time and also combine this printing carousel with a plotter, so that we can not only control the type and amount of food that is dispensed, but also create lines with it.

GOOD: In some ways, what a device like this is doing is putting the tools that are already in a factory into people’s houses. What’s the interest and value, for you, in taking these industrial food processing techniques and building them at the scale of the home kitchen.

Coelho: There are several layers to it, but I think it all comes down to idea of giving people more information. I think of information in two different ways: one is just learning about what you’re eating and the second is actually becoming a part of the information design process or part of the food production process.

So you’re right: There’s plenty of stuff at the grocery store that is made in a factory using these kinds of extruding devices at an industrial scale. But most people have no idea what goes in to making them. I wanted to create a machine that would let people have more information about what they're eating and how it's made, and then, on top of that, also be able to make choices and design their own food.

GOOD: I could see some people looking at this and saying, "Why not just eat a bar of chocolate and some nuts? What’s the point in going through this whole 3D printing process?"

Coelho: That’s a good question, and it goes back to where this project started. I noticed that every aspect of the design world has been really affected by 3D printers, and people spend a lot of time talking about the idea of these machines being in everyone’s homes one day and how it will revolutionize everything. Those conversations made me realize that right now, the only thing that most people really design or create in their own homes is the food they cook. For example, my parents never make anything ever—but they cook frequently, if not every day. So I thought that food would be a really interesting place to explore the potential of domestic digital design.

GOOD: So a 3D food printer is actually a vehicle for people to take something that they’re familiar with doing, which is cooking, and introduce them to design thinking.

Coelho: Exactly. I think it also unleashes an infinite amount of possibilities. When you think about the kinds of things you can do on your computer in terms of design—simple things, like a Photoshop blur filter, for instance—it makes you wonder what a blur filter for food would be? What would it do and taste like? I think there's a really exciting opportunity to give people the same sort of one-button design tools they have on their computer, but for food.

GOOD: Did you build this prototype just to experiment with the ideas, or are you interested in developing it into something I could actually buy at Williams Sonoma?

Coelho: I would love to take it into production! I actually think designers have a big responsibility to explain what's possible and what's not possible, as well as just coming up with creative ideas. When Amit and I put out our concept designs this time last year, people wrote about them as if they were real, and that was really frustrating to me. I had never created concept renderings before, and it made me realize the responsibility of creating a fantastically realistic image—people look at it and think it exists. I think it's important to make that distinction between concept and reality clear because it affects society's reaction to new technologies, as well as what kind of research gets funded and what doesn’t.

Anyway, that's the part of the design process that I really like, the part where you actually try making it and see what works and what doesn't.

Images: (1) Digital chocolatier, Marcelo Coelho; (2) Scallop and cheese spaceshuttle, Cornell University/French Culinary Institute, via the CBC; (3) Turkey and celery square, photo by Dan Cohen, via the BBC; (4) Printed mashed potatoes, via Fabbaloo; (5) Digital chocolatier, Marcelo Coelho; (6) Graphical User Interface, Marcelo Coelho; (7) Graphical User Interface, Marcelo Coelho; (8) Digital chocolatier, Marcelo Coelho; (9) Digital chocolatier, Marcelo Coelho; (10) Concept drawing for a digital fabricator, Marcelo Coelho.

Wednesday, February 16. 2011

Via GOOD

-----

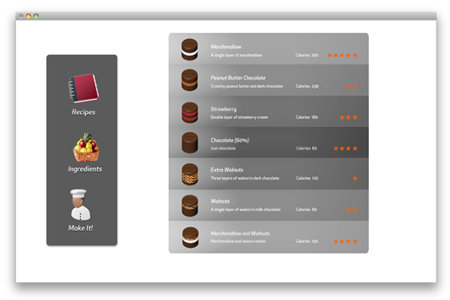

(...) -- Taken out from a longer post about food and architecture by Nicola Twilley --

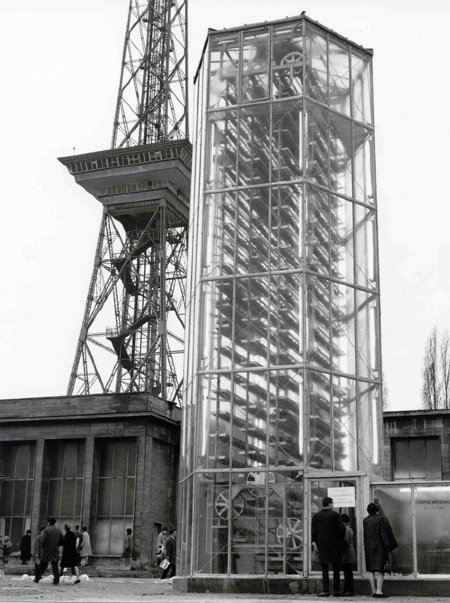

This vertical greenhouse from 1966 was apparently "a space-saving sensation," with a built-in automatic elevator to rotate crops. Eat your heart out, Dickson Despommier!

(...)

Personal comment:

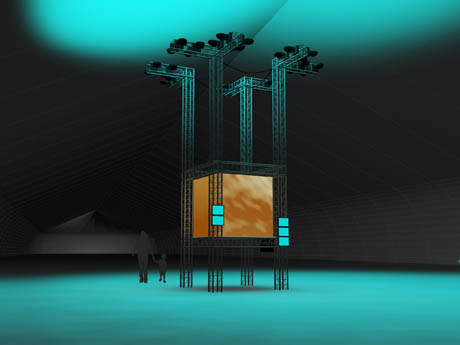

I just saw this picture in an article from Nicola Twilley that makes me think of a project we did back in 2008, Tower of Atmospheric Relations (and that in some other ways retro-confirm the project's hypothesis of a vertical greenhouse building / climate exhibition and clock).

Friday, September 17. 2010

Via Edible Geography

-----

By Nicola

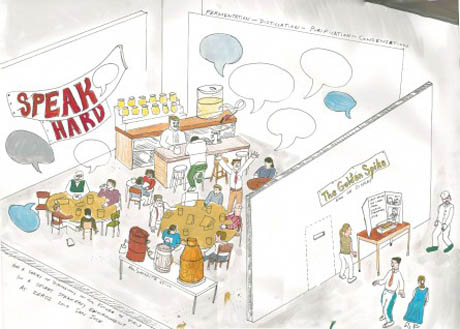

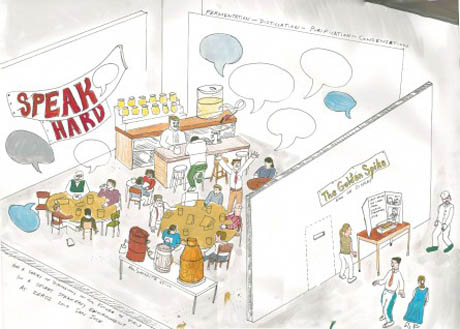

If you are in or near San Jose, California, this weekend, these are just some of the delights that await at this year’s 01SJ Biennial.

IMAGE: Transgenic Mosquitoes of California by the Center for PostNatural History.

Under the pioneering and Utopian instruction to “Build Your Own World,” the Biennial’s curators have assembled an enormous quantity of projects that, at a variety of scales, attempt to redesign our environment, infrastructure, atmosphere, and culture.

Unfortunately, some events have already come and gone — I would have loved to have been able to attend Tuesday’s Still Life with Banquet, in which media artist Grahame Weinbren partnered with chef Kitty Greenwald to serve a meal presented in Dutch still-life format, surrounded by video footage of the food’s decay.

IMAGE: Click for video. Still from A1 (Linard), by Grahame Weinbren. Timelapse presentation of a twelve-week shot, based on a still life by seventeenth-century French painter, Jacques Linard.

It’s a clever conceit, but also — I imagine — functioned as a visceral reminder that our obsession with only buying flawless fruit and vegetables over-prioritises a single, freeze-framed moment in an organic cycle.

Ongoing displays include a Seed Garden Library, arranged by micro-climate suitability, from artist Amy Franceschini’s lovely Victory Gardens project, as well as a transgenic mosquito from the collections of the fascinating Center for Post Natural History. The insect, which has been developed in a biosecurity level 3 laboratory at the University of Bamako, in Mali, is designed to resist the malaria parasite, and should be ready for industrial production as early as next year.

According to a report on SciDev.Net, “The researchers hope that resistant mosquitoes will one day take over wild populations, eventually wiping malaria out.”

IMAGE: Amy Franceschini, Victory Garden Seed Library. (Photo by Amy Franceschini).

The San Francisco-based Studio for Urban Projects (SPUR) have created Public Orchard, an installation that includes heritage fruit trees as well as a discussion space to explore creative solutions to overcome city government resistance to urban edible landscapes. SPUR notes that “fruit trees are discouraged in the permit process because of concerns about the mess on city streets,” while fruit picking in parks is often “technically illegal, as it encourages ‘the destruction of park property.’”

In response, their installation investigates low-maintenance models of urban edible landscapes, municipal codes that encourage public foraging, and collaborative opportunities to harvest and preserve food.

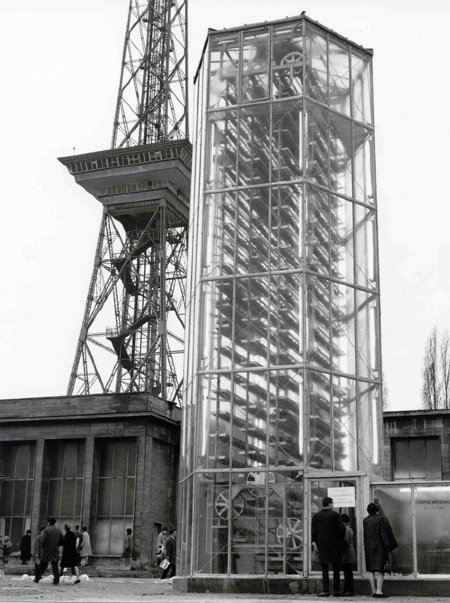

IMAGE: i-Weather, by fabric | ch, an installation at the Biennial that creates “an open-source artificial climate” — a parallel 25-hour day based on the most up-to-date knowledge of human metabolism, circadian rhythms, and the medical efficacy of light therapy.

IMAGE: Sunshine Still, an Biennial installation by futurefarmers that uses a converted moonshine still to convert organic waste and algae into “engine-ready ethanol fuel by day and drinkable ethyl alcohol by night.”

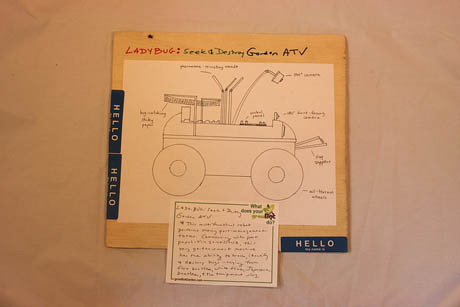

Rebar, the creative genius behind today’s PARKing Day, are also represented at the Biennial, with their FarmCycle, “a pedal-powered alternative to the fossil-fuel driven tractor,” better suited to the needs of urban farmers. On a similar note, my generous hosts from earlier this week, Georgia Tech, have collaborated with The Public Design Workshop to create the Growbot Garden, which investigates a scaled-down form of precision agriculture, incorporating robotics and sensing technology into community gardens and green roofs.

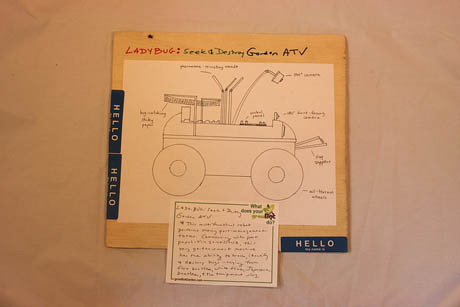

IMAGE: Ladybug board, part of the Growbot Garden Flickr set uploaded by Public Design Workshop.

Today’s events include a pop-up edition of the forageSF Underground Market, set up to skirt around legislation that keeps foraged produce out of farmers’ markets by restricting booths to “primary producers,” and not “gatherers,” as well as a not-to-be missed talk by Darrin Nordahl, author of Public Produce, on “municipal agriculture,” or practical strategies to encourage food production on public land (5:30 p.m., registration required).

Meanwhile, tomorrow’s highlights include a biodiesel bus tour of San Jose’s historic urban orchards, as well as an Imaginary Airforce Flight Attendant Training at designer Natalie Jeremijenko’s xAirport facility — your chance to glide along a zipline above the biodiverse riches of a constructed wetland (as opposed to squeezing into a fossil-fuel guzzling 747 on the environmental wasteland that is a runway built on “reclaimed” marsh).

IMAGE: xAirport, courtesy David Fletcher.

IMAGE: SLO DOG, a hot dog roller grill-inspired entry into Saturday’s Green Prix.

The Biennial closes on Sunday, September 19, accompanied by a Tomato Quintet (a “full set of tomato ripening data in a musification which is accelerated by a factor of 240X”) and accompanying fresh salsa. I wish I could be there — let me know what you think, if you go.

IMAGE: Tomato Quintet, in the recording studio. Photo by Greg Niemeyer.

Monday, January 18. 2010

Everyone is talking about local food, farmers markets and like, cooking? Who has time for that? And really, is Michael Pollan serious with his Rule #2- "Don't eat anything your great-grandmother wouldn't recognize as food." Why bother even having an MIT if you are going to think that way?

Make shows us how Marcelo Coelho and Amit Zoran of the Fluid Interfaces Group at MIT propose a much greener, more efficient, waste-free process: Print out your dinner.

Cornucopia is a concept design for a personal food factory that brings the versatility of the digital world to the realm of cooking. In essence, it is a three dimensional printer for food, which works by storing, precisely mixing, depositing and cooking layers of ingredients.

Cornucopia's cooking process starts with an array of food canisters, which refrigerate and store a user's favorite ingredients. These are piped into a mixer and extruder head that can accurately deposit elaborate combinations of food. While the deposition takes place, the food is heated or cooled by Cornucopia's chamber or the heating and cooling tubes located on the printing head.

Just imagine the impact this would have. Real food rots. It has peels. Half of it is wasted. The whole infrastructure of food stores with their refrigerated cases becomes unnecessary. And imagine, no more pesky farmers markets occupying valuable parking lots. This is truly green.

More at MIT's Fluid Interfaces Group

-----

Via Treehugger

Personal comment:

Looks like a future hybrid between old food artifacts dedicated to the conquest of space (pills and paste in tubes tasting like food) and 3d model printing. Maybe will be go toward a new type of room in our living spaces. Instead of the kitchen, we will have the printing room (where we'll print food, objects and magazines...)

Monday, December 07. 2009

[Greenhouses being erected in Jittu, Ethiopia via NYT] Two weeks ago, in an article entitled ‘Is There Such a Thing as Agro-Imperialism‘, the New York Times reported that financially wealthy but resource-poor nations in the Middle East and Asia are attempting to ensure food security by buying up large tracks of arable land in Africa, “seeking to outsource their food production to places where fields are cheap and abundant.”

The rising food prices last year left many wealthy nations feeling vulnerably aware of their food insecurity. Some fluctuations, such as the spike in food prices, may be transitory, but others, such as global population growth and water scarcity, show not signs of abaiting, and have created a global market for farmland.

The article points out that “because much of the world’s arable land is already in use — almost 90 percent by some accounts – if one excludes forests and fragile ecosystems — the search has led to the countries least touched by development, in Africa, which contains one of the earth’s last large reserves of underused land.” Research by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), the International Institute for Environment and Development and advocacy groups such as Grain, suggests that huge tracts of Africa’s agricultural lands are being sold, off the radar.

![[Satellite measurements of vegetation. Map by Robert Simmon, based on GIMMS vegetation data and World Wildlife Fund ecoregions data.]](http://blog.fabric.ch/fabric/images/1149_1260223207_1.jpg)

[Satellite measurements of vegetation. Map by Robert Simmon, based on GIMMS vegetation data and World Wildlife Fund ecoregions data.]

There is, of course, an irony that a continent which is persistently beset by large-scale famine is seeing its land sold off, in order to sustain wealthy neighboring nations.

Foreign investors — some governments, some private interests — are promising to construct infrastructure, bring new technologies, create jobs and boost the productivity of underused land so that it not only feeds overseas markets but also more Africans. It remains to be seen, however, whether local farmers and African citizens will reap any of the benefit of this agro-imperialism.

Other nations, including China, India, South Korea and the UAE are also joining the global land-buy.

![[Land buyers and sellers, via mongabay.com]](http://blog.fabric.ch/fabric/images/1149_1260223208_2.jpg)

[Land buyers and sellers, via mongabay.com]

Great interactive map of global land transactions found here. The first green revolution, which began in 1945, enabled developing nations to achieve food independence. Mexico was the first ‘test site’ of this green revolution, through programs largely funded by the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, and India was the second poster child of the green revolution. There have been numerous attempts to introduce the versions of the Mexican and Indian project into Africa, but these programs have generally been less successful, due in small part to environmental factors, and in large part to political and economic instability.

This second version of an African green revolution seems far more ominous, leaving poorer nations to sell off the rights to their own survival.

Pruned posted a while back describing how European nations were considering spending upward of “£5bn on a string of giant solar power stations along the Mediterranean desert shores of northern Africa and the Middle East, with the hopes that Africa could provide part of their energy needs, basically turning the continent into one giant solar power plant.”

In an optimistic scenario, Africa nations will see lush fields of food supported by a robust infrastructure of water and electricity delivery – an African ‘Broadacre City’. However, if the resource imperialism of the 19th and early 20th centuries is anything to judge by, the outlook for Africa isn’t rosy, both in terms of environmental impact and the possibility of wealth trickling down to local farmers.

Nations as global supermarket?

-----

Via InfraNet Lab

Saturday, September 26. 2009

Recueilli par PHILIPPE BROCHEN

Dans un magasin de Lucknow, dans le nord de l'Inde, le 6 juillet. (REUTERS)

Aurélie Trouvé, docteur en économie et ingénieur agronome, est enseignante-chercheuse à l'Agrosup Dijon et copréside la branche française d'Attac. Elle réagit aux déclarations de la FAO (Organisation des Nations unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture) selon laquelle il y aura 2,3 milliards de bouches de plus à nourrir en 2050 - soit 9 milliards d'être humains - et qu'en conséquence une hausse de 70% de la production agricole est nécessaire.

Les chiffres fournis par la FAO vous étonnent-ils?

Pour l'augmentation de la production agricole de 70%, non, il n'y a rien d'étonnant s'il n'y a pas de prise de conscience et de transformation de notre mode de consommation alimentaire, notamment dans les pays du Nord.

Pour des néophytes de la question il est difficile de comprendre qu'une augmentation de la population mondiale d'environ un tiers nécessite d'augmenter la production agricole de 70% pour pouvoir nourrir tout le monde.

Dans les pays du Sud, notamment en Asie et en Afrique, il y aura une augmentation des besoins pour des raisons démographiques et aussi parce qu'on assiste actuellement à une transformation du modèle alimentaire. Il tend notamment à imiter les pays du nord, notamment en ce qui concerne l'alimentation carnée. Et il ne faut pas oublier que pour produire une kilocalorie animale, il faut plusieurs plusieurs kilocalories végétales. C'est une des explications de la disproportion entre l'augmentation des besoins alimentaires de 70% et la hausse de la population qui n'est que d'un tiers.

Une telle augmentation de la production agricole en si peu d'années vous semble-t-elle possible?

C'est une question qui fait couler beaucoup de salive et d'encre parmi les agronomes et les scientifiques. Cela doit surtout amener à une prise de conscience, parce qu'aujourd'hui le modèle de consommation alimentaire des pays du nord est non soutenable à une échelle mondiale. Si toute la population planétaire se nourissait comme un habitant des Etats-Unis, on ne pourrait nourrir que 2 milliards d'être humains au lieu des 6 qui peuplent actuellement la Terre.

Parmi les enjeux, il y a donc une question culturelle liée à la mondialisation, mais aussi des raisons politiques. Non?

Evidemment, et ces raisons politiques ont induit des choix. Aujourd'hui, la plupart de la viande vient d'Amérique à des prix qui sont artificiellement très bas. Parce que cette viande provient de très grandes exploitations qui produisent massivement et qui, pour beaucoup, ont des coûts sociaux et environnementaux très faibles. Notre alimentation très carnée s'appuie aussi sur une production qui induit un accaparement de plus en plus important des terres dans ces pays et concurrence directement l'agriculture vivrière. Au Brésil, il y a ainsi des millions de paysans sans terre.

L'UE est-t-elle aussi responsable de cette situation?

En Europe, on a mis des droits de douane proches de zéro sur la question de l'alimentation animale. L'UE a donc avantagé l'importation alors que l'on aurait pu avoir une production locale liée à l'herbe. Plus globalement, l'UE a développé une logique exportatrice, à l'opposé d'une logique d'autonomie alimentaire et de relocalisation des activités. Résultat: nous ne sommes pas autosuffisants sur le plan alimentaire, puisque nous importons plus que nous n'exportons, malgré des conditions agronomiques très favorables.

Que préconisez-vous?

Il faut réinterroger profondément la libéralisation des marchés qui est le dogme actuel des négociations internationales. Cette libéralisation des marchés est orchestrée par le FMI, la Banque mondiale et l'OMC depuis les années 80. Elle est toujours en marche et est soutenue par les pays les plus puissants.

La crise alimentaire mondiale nous a montré que cette libéralisation des marchés était destructrice pour l'agriculture vivrière, notamment des pays du sud, et qu'elle induit une très forte volatilité des prix qui fragilise les petites exploitations et sélectionne les plus compétitives. Ces petites exploitations paysannes, ultra majoritaires, sont directement concurrencées par l'agriculture industrielle des pays du Nord et l'agriculture ultra compétitive des grandes exploitations du Sud qui commettent des dégâts humains et environnementaux considérables.

Pensez-vous qu'on puisse encore changer de modèle économique et politique agricole?

Je pense surtout que c'est nécessaire et que nous n'avons pas d'autre choix. Un exemple instructif: pour l'année 2009, nous sommes en train d'exploser les chiffres de la faim dans le monde. Aujourd'hui, c'est davantage une question d'inégalités mondiales que de quantité, davantage un problème de juste répartition et de règles alimentaires.

Faut-il, comme pour le climat, agir dès à présent?

L'agriculture a une place dans la crise climatique: elle est à la fois victime (les régions qui souffrent déjà de la faim seront les plus touchées par le réchauffement, les régions tropicales et subtropicales vont voir leur potentiel agricole touché) et responsable (essentiellement le modèle agricole intensif et industriel des pays du nord). N'oublions pas par ailleurs que l'agriculture intensive est dépendante des ressources fossiles, qui sont en cours d'épuisement.

En Asie et ailleurs, on a vu des stagnations des rendements agricoles, stagnations imputées au modèle intensif: à savoir, l'épuisement des sols et des ressources hydriques, la résistance aux maladies et aux ravageurs (animaux nuisibles aux cultures)... De même, sur les cultures OGM en Argentine, on a vu des retournements de rendements...

Y a-t-il quand même de quoi garder un peu d'espoir ou tout est d'ores et déjà foutu, surtout pour les pays du Sud?

Ce qui est certain, c'est qu'il va y avoir une tension de plus en plus forte sur les terres. Si on ne change pas de mode de développement et de consommation, on va avoir besoin de terres à l'extérieur pour les besoins alimentaires et aussi pour la production d'agrocarburants par des grandes entreprises privées et les pays.

Mais si je suis une chercheuse engagée, c'est que j'ai de l'espoir, tout en sachant qu'il n'y a pas d'autre choix que de changer de modèle de développement et aussi les politiques qui les régulent. Il ne faut oublier qu'actuellement, trois quarts des personnes qui sont sous-nutries dans le monde sont des paysans.

Alors, quel modèle adopter?

Des centaines d'experts en agronomie de l'IAASTD, un organisme qui, pour faire vite, peut-être comparé au Giec pour le climat, mettent en avant l'agro-écologie, les connaissances indigènes, le lien de la production et des connaissances agricoles avec le fonctionnement des écosystèmes.

-----

Via Libération

Wednesday, July 15. 2009

This is a must-see. The beautifully made infographic animated movie "It's Time for Real / Eat Local, Eat Real" highlights the increasing tendency of food importation, and how this phenomenon influences the economy, the environment and our neighborhoods. The message is mainly meant for Canadians, but certainly applies universally.

The movie, with a graphical style similar to the Stranger than Fiction opening scene, is part of the campaign Eat Real, Eat Local [eatrealeatlocal.ca], by the Unilever brand Hellman's. More information about the design process and creation of the movie can be found at the Glossy project page:

"We all found the statistics pretty eye opening. I think everyone involved changed the way we buy our food. Yoho's wife had a baby girl in the middle of the project, and I grew a playoff beard which I've been reluctant to shave (just superstitious I guess). Challenges early on were the levels of legal approval the team at Unilever and Ogilvy had to go through on all the stats. Everyone wanted to make sure that the information was fair and irrefutable. All the food in the shoot was Canadian, which is no small challenge in spring. I don't think I've ever been hugged by agency and their clients in twenty years in the business. That was definitely a high point."

You can watch the video HERE.

-----

Via Information aesthetics

Personal comment:

"Information design" (motion, 3d) en rapport avec le post ci-dessous bien sûr. Concerne le canada, mais a le mérite de donner de la visibilité aux chiffres.

|

![[Satellite measurements of vegetation. Map by Robert Simmon, based on GIMMS vegetation data and World Wildlife Fund ecoregions data.]](http://blog.fabric.ch/fabric/images/1149_1260223207_1.jpg)

![[Land buyers and sellers, via mongabay.com]](http://blog.fabric.ch/fabric/images/1149_1260223208_2.jpg)