Monday, November 23. 2015

The Information Age Is Over. Welcome to the Infrastructure Age | #infrastructure

Note: this article was published a while ago and was rebloged here and there already. I kept it in my pile of "interesting articles to read later when I'll have time" for a long time as well therefore. But it make sense to post it in conjunction with the previous one about Norman Foster and by extension with the otehr one concerning the Chicago Biennial.

It is also sometimes interesting to read posts with delay, when the hype and buzzwords are gone. Written in the aftermath of the Tesla annoncement about its home battery (Powerwall), the article was all about energy revolution. But since then, what? We're definitely looking forward...

Via Gizmodo

-----

Photo: SpaceX

Nobody wants to say it outright, but the Apple Watch sucks. So do most smartwatches. Every time I use my beautiful Moto 360, its lack of functionality makes me despair. But the problem isn’t our gadgets. It’s that the future of consumer tech isn’t going to come from information devices. It’s going to come from infrastructure.

That’s why Elon Musk’s announcements of the new Tesla battery line last night were more revolutionary than Apple Watch and more exciting than Microsoft’s admittedly nifty HoloLens. Information tech isn’t dead — it has just matured to the point where all we’ll get are better iterations of the same thing. Better cameras and apps for our phones. VR that actually works. But these are not revolutionary gadgets. They are just realizations of dreams that began in the 1980s, when the information revolution transformed the consumer electronics market.

But now we’re entering the age of infrastructure gadgets. Thanks to devices like Tesla’s household battery, Powerwall, electrical grid technology that was once hidden behind massive barbed wire fences, owned by municipalities and counties, is now seeping slowly into our homes. And this isn’t just about alternative energy like solar. It’s about how we conceive of what technology is. It’s about what kinds of gadgets we’ll be buying for ourselves in 20 years.

It’s about how the kids of tomorrow won’t freak out over terabytes of storage. They’ll freak out over kilowatt-hours.

Beyond transforming our relationship to energy, though, the infrastructure age is about where we expect computers to live. The so-called internet of things is a big part of this. Our computers aren’t living in isolated boxes on our desktops, and they aren’t going to be inside our phones either. The apps in your phone won’t always suck you into virtual worlds, where you can escape to build treehouses and tunnels in Minecraft. Instead, they will control your home, your transit, and even your body.

Once you accept that the thing our ancestors called the information superhighway will actually be controlling cars on real-life highways, you start to appreciate the sea change we’re witnessing. The internet isn’t that thing in there, inside your little glowing box. It’s in your washing machine, kitchen appliances, pet feeder, your internal organs, your car, your streets, the very walls of your house. You use your wearable to interface with the world out there.

It makes perfect sense to me that a company like Tesla could be at the heart of the new infrastructure age. Musk’s focus has always been relentlessly about remolding the physical world, changing the way we power our transit — and, with SpaceX, where future generations might live beyond Earth. The opposite of cyberspace is, well, physical space. And that’s where Tesla is taking us.

But in the infrastructure age, physical space has been irrevocably transformed by cyberspace. Now we use computers to experience the world in ways we never could before computer networks and data analysis, using distributed sensor devices over fault lines to give people early warnings about earthquakes that are rippling beneath the ground — and using satellites like NASA’s SMAP to predict droughts years before they happen.

Of course, there are the inevitable dangers that come with infusing physical space with all the vulnerabilities of cyberspace. People will hack your house; they’ll inject malicious code into delivery drones; stealing your phone might become the same thing as stealing your car. We’ll still be mining unsustainably to support our glorious batteries and photovoltaics and smart dance clubs.

But we will also benefit enormously from personalizing the energy grid, creating a battery-powered hearth for every home. Plus the infrastructure age leads directly into outer space, to tackle big problems of human survival, and diverts our impoverished attention spans from gazing neurotically at the social scene unfolding in tiny glowing rectangles on our wrists.

The information age brought us together, for better or worse. It allowed us to understand our environment and our bodies in ways we never could before. But the infrastructure age is what will prevent us from killing ourselves as we grow up into a truly global civilization. That is far more important, and exciting, than any gold watch could ever be.

Norman Foster: "I have no power as an architect, none whatsoever" | #energy #sustainability

Note: Meanwhile, on the "big architects" end of the spectrum... Where I enjoyed to read the sentence " Foster is delighted that Britain now has an infrastructure commission, chaired by Andrew Adonis, which he says gives the opportunity to plan in 30-year cycles and remove the politics from infrastructure."

Via The Guardian

-----

By Rowan Moore

Norman Foster’s Millau viaduct in France, which has ‘cut out five-hour traffic jams’. Photograph: Michael Reinhard/Corbis

“Do you believe in infrastructure?” asks Norman Foster, with challenge in his voice. He does. Infrastructure, he says, is about “investing not to solve the problems of today but to anticipate the issues of future generations”. He cites his hero, Joseph Bazalgette, who, in solving Victorian London’s sewage problems, “thought holistically to integrate drains with below-ground public transportation and above-ground civic virtue”.

Foster is delighted that Britain now has an infrastructure commission, chaired by Andrew Adonis, which he says gives the opportunity to plan in 30-year cycles and remove the politics from infrastructure. He will expound these views this week at the Urban Age 10th anniversary Global Debates, Urban Age being the LSE’s Deutsche Bank-sponsored series of conferences in which high-powered and highly powerful people travel the world exchanging views on city building.

Statistics spin out of him about sustainability. “If you take the carbon footprint of London, that’s one seventh of that of Atlanta, so there’s a relationship between density and emissions. The whole climate change issue, which many would argue is about the survival of the species, comes down to urbanism.

Foster’s proposed design for the Thames Hub airport. Photograph: dbox/Foster & Partners

“When I was in Harvard recently, I said that each of us in this room, the energy that we consume in one year would equal the energy consumed by two Japanese, 13 Chinese, 31 Indians and 370 Ethiopians. So you start to take the relationship between energy consumed by a society and infant mortality, life expectancy, sexual freedom, academic freedom, freedom from violence. So those societies that consume more energy have more of those desirable qualities, so all those issues are inseparable from the nature of the infrastructure.” The connections between these points are not always clear, but the argument seems to be that better use of energy through better infrastructure will enable more people to live better.

Of his own work, Foster says that many of the most important projects are not what are normally considered buildings, but things such as the Millennium Bridge, the pedestrianisation of Trafalgar Square in London, the Millau viaduct in southern France and the remaking of the Marseille waterfront. More statistics: “Millau cut out five-hour traffic jams, which meant that the saving in CO2 from the 10% of traffic that is heavy good vehicles had an effect equivalent to a forest of 40,000 trees.”

He has campaigned vigorously for the Thames Hub, a new airport in the Thames estuary with an associated network of huge ambition: an orbital railway around London, a flood barrier, tidal energy generation. He is profoundly disappointed that his plan is likely to be rejected in favour of an expanded Heathrow: “The reality of a hub airport is that you can never ever do that at Heathrow. If you do that at Heathrow now you can absolutely guarantee that we will still be pedalling furiously to stand still. You can never accommodate long-term needs there.”

Norman Foster: ‘The whole climate change issue comes down to urbanism.’ Photograph: Manolo Yllera

But given what he just said about sustainability, should we be expanding airports at all? “Do you eat meat?” he asks scathingly. “You’re probably going to have your hamburger in spite of the fact that you’re going to make a much greater impact than any travel.” Air travel, he says, “compares well statistically with the amount of methane produced by cows and the amount of energy and water needed to produce a hamburger”.

“The reality is that all society is embedded in mobility. You’re going to take that flight. You’d be better to take the flight out of an airport that is driven by tidal power and which uses natural light, and which anticipates the day when air travel will be more sustainable.” He talks of solar-powered flight and planes made of lightweight composite materials.

It could also be asked what is the role of the architect in what is generally the province of engineers, planners and politicians. Around us is evidence of his practice’s apparent potency – towers in China and India, a model of the giant circle, one mile in circumference, which will be Apple’s new headquarters, images of a concept for habitats on Mars – but Foster says: “I have no power as an architect, none whatsoever. I can’t even go on to a building site and tell people what to do.” Advocacy, he says, is the only power an architect ever has.

To write about Foster presents a particular challenge to an architecture critic. The scale of his achievement is immense and he has created many outstanding buildings. A wise man recently pointed out that if Foster had only built his 20 or 30 best works, critical admiration would be virtually unqualified. It is largely because his practice has designed many more projects than this that he sometimes gets a bad press. But would it really have been better if he had confined himself to a boutique practice in order to preserve his architectural purity?

It can seem peevish and petty to question his work, but it is not beyond criticism. In particular, it can become weaker the more it makes contact with realities outside itself. If you look upwards in the Great Court he designed in the British Museum, you will see an impressive structure of steel and glass, but at your own level it becomes bland and sometimes clumsy. The Gherkin is a memorable presence on the London skyline, but awkward at pavement level. The Millennium Bridge, even with the modifications necessary to stop it wobbling, is confident and elegant except at its landing, where the overhang of its cantilever creates spaces that are plain nasty.

In the context of infrastructure, the question is also whether it adapts to the political, social and physical conditions that surround it. In answer to Foster’s question, yes, I do believe in infrastructure. Or, rather, I’d compare it to water: essential to existence, life-enhancing and sometimes beautiful, but with the power to damage and destroy if misused.

Design for the proposed drone-port project in Rwanda. Photograph: Foster & Partners

All this makes a new drone-port project in Rwanda one of Foster and Partners’ most intriguing. Conceived with Jonathan Ledgard, the director of Afrotech, who describes himself as a thinker on the future of Africa, it is a plan to create a network of cargo drones that can bring medical supplies and blood, plus spare parts, electronics and e-commerce, to hard-to-access parts of Africa. The drones have ports – shelters where they can safely land and unload, but which also serve as “a health clinic, a digital fabrication shop, a post and courier room, and an e-commerce trading hub, allowing it to become part of local community life”. Because of their inaccessible locations, they have to be built using materials close to hand, so techniques have been developed for efficiently making local earth into bricks and stones into foundations.

It is impossible at this point and at this distance to know if the drone-port project will achieve what it hopes, but its ambition to adapt to local conditions seems absolutely to the point. The interesting question is then how to bring the same thinking to infrastructure in a developed country, such as Britain. What is the right infrastructure for the society and culture of this country, at this point? Has it changed since Foster’s Victorian heroes, such as Bazalgette, did their work? Can we import the large-scale thinking of modern China and, if so, with what modification? These are good questions for an architect to address.

Urban Age Global Debates run until 3 December; lsecities.net/ua

Related Links:

Wednesday, November 18. 2015

Joseph Grima / Chicago Architecture Biennial | #exhibition

Note: still posting about exhibitions... the current one in Chicago that opened a month ago and will last until next January is certainly one to visit. I didn't had the occasion and wonder if I will... But the open angle usually taken by one of its curator, Jospeh Grima, when it comes to consider what is/might be(come) architecture, is certainly interesting as it also points out different ways and strategies of "being" an architect. Altough there is no reason to erase the old way, it just that it opens perspectives... I'll look forward for more inputs about the show.

Via ArchDaily

-----

A few weeks ago, during the opening of the Chicago Architecture Biennial, we eagerly awaited our opportunity to speak with Joseph Grima, the co-artistic director of the first Chicago Architecture Biennial. In an exhibition with such an open theme, we wanted to understand the driving forces behind the assembly of the participants, in addition to how the city of Chicago itself influenced decisions in the planning of this largest gathering of architecture in North America. Watch the video above and read a transcript of Grima's answers below.

Artistic Directors Joseph Grima & Sarah Herda. Image Courtesy of Chicago Architecture Biennial

ArchDaily: Can you introduce yourself and tell us about the motivations behind The State of the Art of Architecture?

"I’m Joseph Grima, I’m the co-artistic director of the first Chicago Architecture Biennial, The State of the Art of Architecture."

"Chicago is a city that has over a century of history of innovation and bold vision in architecture and that’s something that really permeates the culture the city—beyond the public administration but also into its inhabitants—a real appreciation for the value and potential of architecture."

"The Biennial was a project that was incubated by the city of Chicago. I was brought in by my co-artistic director, Sarah Herda, who was really involved in the very early stages of the conversation around what this Biennial could be. It’s a project the city is very much invested in, that it really sees being defining in terms of its future, and Sarah and I, when we were given the opportunity to think about what this first exhibition could be, we were really thinking about this is an incredibly important moment in the history of architecture in this region, in this country, in this continent, in fact, because it is in fact the largest exhibition of contemporary architecture that’s ever been staged in North America. And so it was very important to think about what kind of a statement would be made with this first exhibition and we decided very early on that it shouldn’t be given a theme; it shouldn’t look at a particular aspect of architecture but it should be, in a way, a point of observation into the landscape of contemporary architecture — not just in this country but around the world. And so the title, The State of the Art of Architecture, really attempts to capture this idea that architecture is something extremely broad, that takes on many, many different forms, and that is mutable. It changes over time. So this is the “state of the art” today, it’s where we are today. It’s a small selection. It’s, in a way, trying to sample a number of different visions of what architecture is and what it can be, but it’s also trying to make the point that architecture is not simply a profession — it’s not something that just simply serves the practical purpose of keeping the rain out. It’s much more than that. It’s a form of cultural practice. And it’s an art form: the art of architecture. And so these are the key ideas that we really wanted to tackle with this exhibition."

Joseph Grima during the press tour at the opening of the Chicago Architecture Biennial. Image © Diego Hernández

ArchDaily: How did you select the Biennial participants?

"We did very very extensive reviews, we went through a very extensive review process and looked at the work of over 500 architects. We didn’t necessarily chose them on the basis of their merit - of some being better than others or some being more interesting than others - but we wanted to offer an extremely transversal view into the preoccupations, the concerns, the ideals, the ideas, the impulses that animate architecture today. And so the participants were really selected on the basis of bold vision, and of taking a risk in thinking about what architecture could be. And, in some way, kind of pushing it beyond its current state, kind of giving it an impulse towards the future. And that took many, many different forms. And what we were really interested in, one of the reasons why no room has a particular theme, but all the projects are in dialogue, they are all pulling in completely different directions; they are all attempting to do different things and no two are really making the same statement about architecture. And so we see really, the exhibition as a conversation."

Chicago Horizon / Ultramoderne. Winner of BP Prize. Image © Diego Hernández

ArchDaily: Can you tell us what you hope the Biennial's more permanent legacy will be?

"It was really important to us, from the beginning, that this exhibition should not be some sort of transient that would come in, go out, remain here for three months, perhaps inspire people but leave nothing behind. But we also wanted to take the opportunity to actually leave something tangible behind, and so through a collaboration with the Department of Parks of the City of Chicago and also with the sponsorship of BP we were able to organize the commissioning of a series of pavilions - or rather we organized a competition that was also covered by ArchDaily - for the design of a Lakefront Kiosk that would serve, during the summer months, the purpose of a concession stand. And also, through the collaboration with three schools in Chicago, the commissioning of three other concession stands. So these little concession stands that will populate the Lakefront during the summer months are something that will live on, that will stay in Chicago — and will possibly move around because they’re permanent architecture, so to speak, but not permanent in their site. They can be moved to different locations from year to year. And they are really a demonstration of the fact that architecture has extraordinary potential on every scale. It doesn’t necessarily need to be an entire landscape or a city plan or a house in order to have architectural value. But it can, even on the scale of a concession stand, it can make a huge difference in the city."

Joseph Grima is an architect, writer, curator, and researcher based in Genoa, Italy. From 2011 to 2013 he was editor-in-chief of Domus, a monthly magazine of architecture, design, and art. Grima recently curated the 2014 Biennale Interieur in Kortrijk, Belgium, one of Europe's oldest design biennials, and was co-curator of the first edition of the Istanbul Design Biennial, a major international exhibition inaugurated in 2012. He is the 2015 Director of IDEAS CITY, an ideas festival organized by the New Museum in New York and dedicated to exploring the future of cities.

See ArchDaily's coverage of the Chicago Architecture Biennial.

Related Links:

Monday, November 09. 2015

Super Superstudio at PAC/Milano | #exhibition #speculation #questions

Note: I recently posted about the E.A.T exhibition (closed on 1s Nov.) at the Museum der Moderne in Salzburg. Now comes the time of a new important exhibition at PAC (Milano) looking back to influential predecessors: Superstudio ...

There have been many exhibitions or mentions recently about this radical italian group, sure. Yet he interesting twist this time is that first, it is curated by Andreas Angelidakis, greek architect which work and research lead him very close to contemporary art, if not to ("new aesthetic" ?) "digital-media artists" (as Andreas was/is part of the "neen" group, composed among others by artists such as Miltos Manetas, Rafael Rozendaal, Angelo Plessas, etc.); secondly, the exhibition displays unseen works and tries to connect Superstudio past activities to contemporary works in art^z

Btw, for friends also living or working in Lausanne, the curator of the exhibition - Andreas Angelidakis - will be present in the citry and give a talk during the coming "Post Digital Cultures" symposium organized by Festival Les Urbaines 2015, next early December.

Via Domus

-----

In Milan, a dialogue between Superstudio and 19 contemporary artists establishes connections and relations among the Florence group’s research and contemporary culture.

The Milan PAC presents the oeuvre of Superstudio (1966–1978), the group of radical architects and radical designers from Florence, which not only influenced the way of thinking and designing of architects such as Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas and Bernard Tschumi, but also definitively questioned the boundary between art and architecture, and which is regarded as the last great Italian avant-garde.

“The exhibition is the chance to investigate the possibilities of a form of discourse through images that is still open, in which the strength of Superstudio’s projects – drawn from the large and mostly unpublished archive of the group in Florence – and of their environments, displayed together for the first time, enables to disclose and establish relationships with contemporary art,” curators Vittorio Pizzigoni and Valter Scelsi explained.

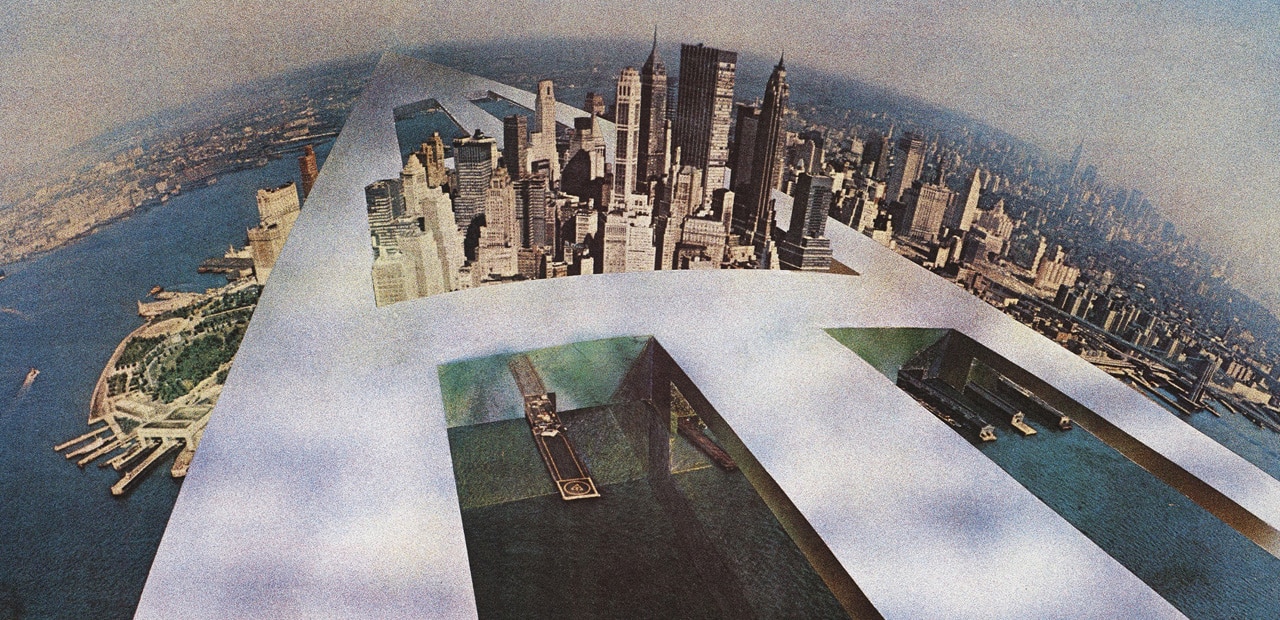

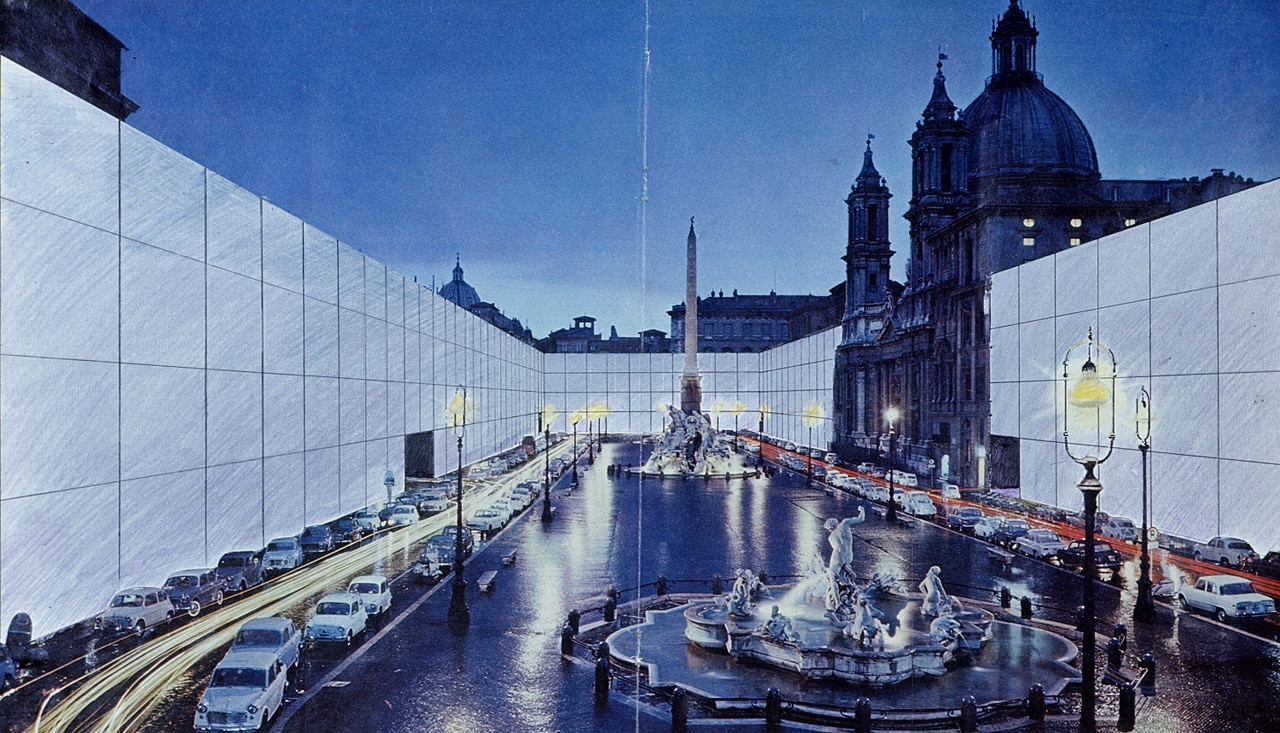

Superstudio, il Monumento Continuo, New York, 1969. MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Roma. Collezioni MAXXI Architettura. Fondo Superstudio. Above: Superstudio, il Monumento Continuo, Piazza Navona, 1970 Courtesy Pinksummer.

In a unique set-up, conceived by Baukuh and Valter Sclesi together with Superstudio, the Continuous Monument – perhaps the group’s most famous project – enters the PAC, which in itself is a monument to Italian modernity, transfiguring the exhibition space and captivating the viewer in a dynamic experience.

The exhibition will reconstruct Superstudio’s most important projects by bringing together its most representative pieces of design, installations and films, and by building – as a part of the total urbanisation model promoted by Superstudio itself – a dialogue with 19 works by 19 contemporary artists, who have drawn the raw material for their oeuvre from the Florence group’s research: Danai Anesiadou, Alexandra Bachzetsis, Ila Beka and Louise Lemoine, Pablo Bronstein, Stefano Graziani, Petrit Halilaj & Alvaro Urbano, Jim Isermann, Daniel Keller & Ella Plevin, Andrew Kovacs / Archive of Affinities, Rallou Panayotou, Paola Pivi, Angelo Plessas, Riccardo Previdi, RO/LU, Priscilla Tea, Patrick Tuttofuoco, Kostis Velonis, Pae White, Yacht-Utopia/Distopia.

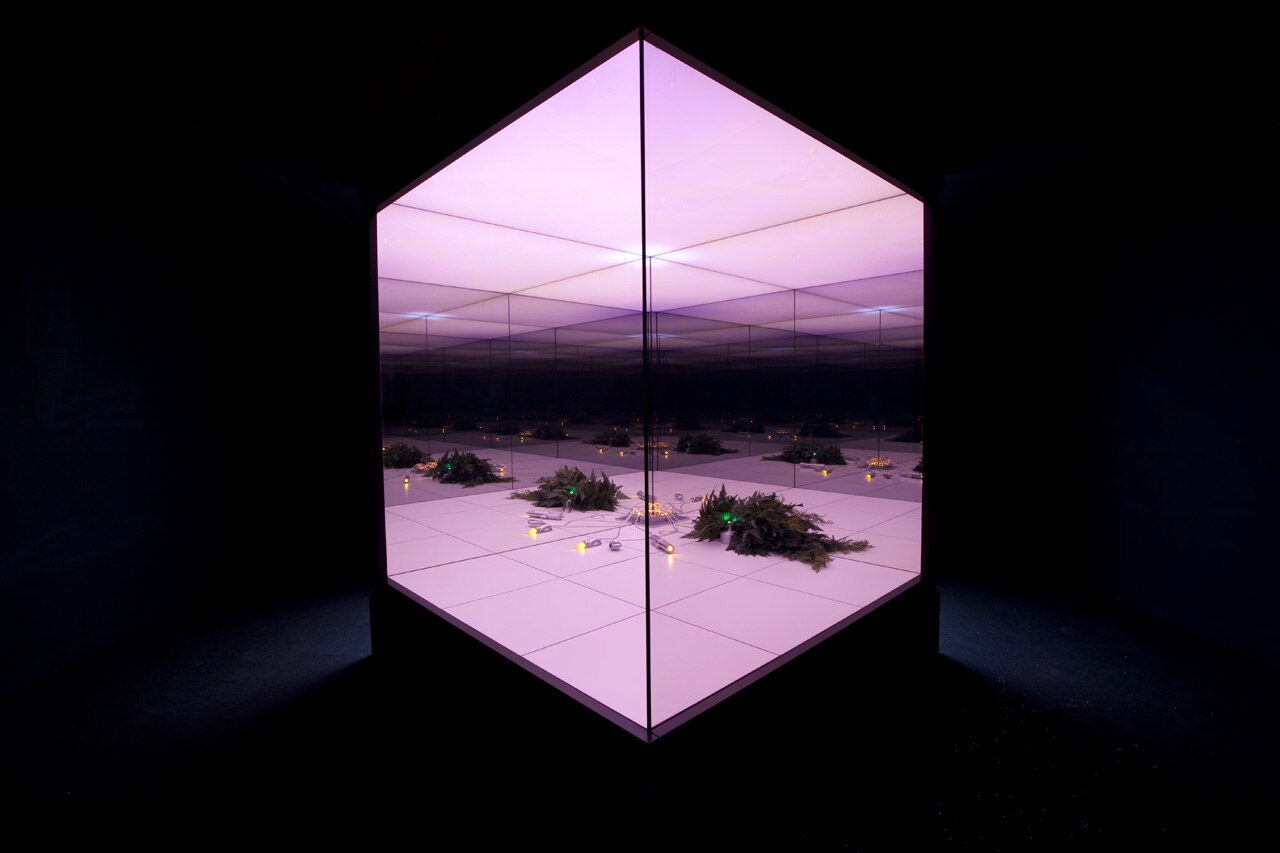

Petrit Halilaj & Alvaro Urbano, What comes first, 2015. Installation, mixed media. Courtesy the artists.

“In selecting contemporary artists to be included in the exhibition, we chose those works that could be imagined as potential answers to Superstudio’s questions. The group’s works from 1970 are still radical today, as they shaped an architecture of premonitions, rather than answers, of questions, rather than objects,” Andreas Angelidakis, co-curator of the exhibition, pointed out. “Their work has put together a number of enigmas, concerning not only architecture, but also the way we live on our planet. Fifty years later, we can start seeing the answers to those questions raised in projects such as The Continuous Monument or Fundamental Acts. A continuous glossy surface that meets all of our needs and desires, and spreads across the world? Could it be that this surface exists today in the form of the Internet?”

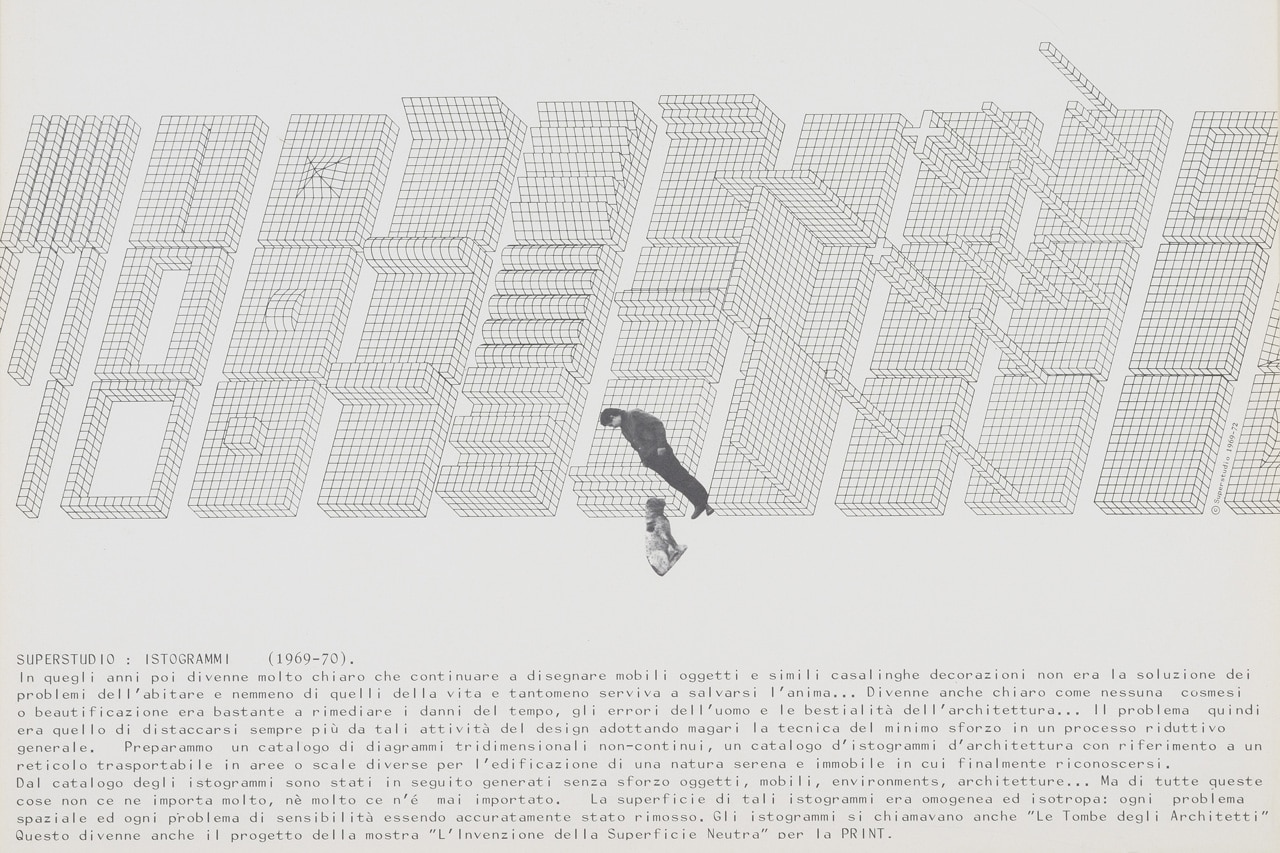

Superstudio, Istogrammi manifesto, 1972 (François Lauginie, FRAC Centre Orléans)

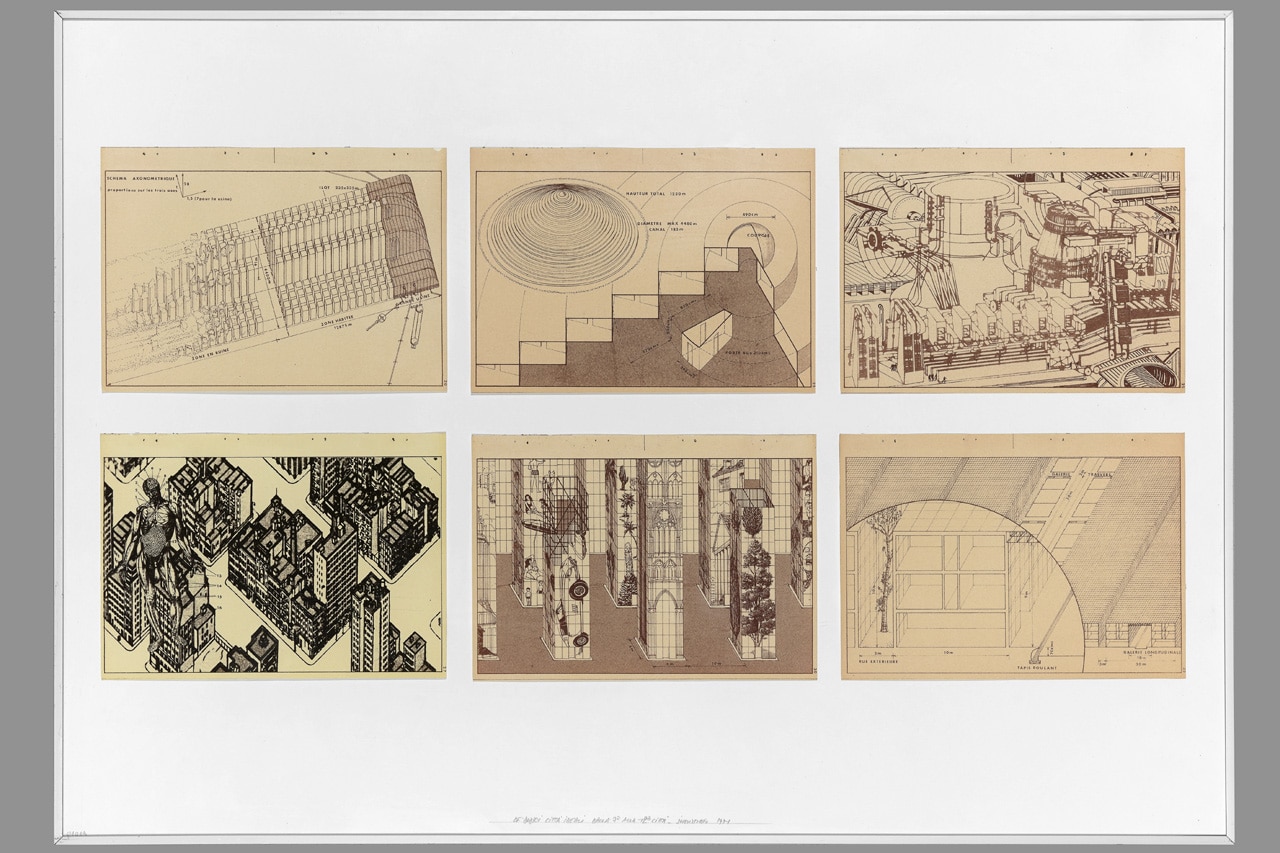

Superstudio, Le Dodici Città Ideali, settima - dodicesima città, 1971 (photo Giulio Boem).

Superstudio, Supersuperficie(1972), 2000 (photo ZEPstudio, Centro per l'Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci).

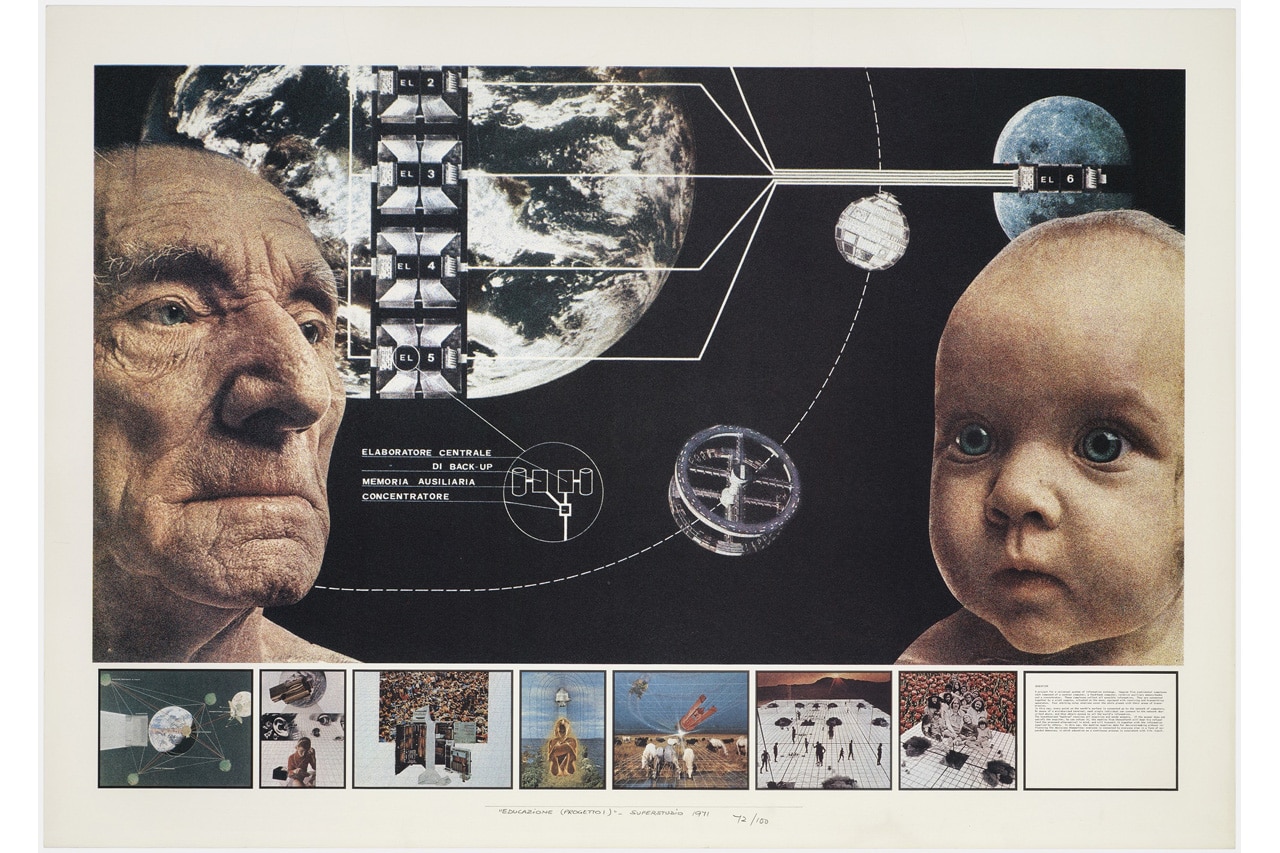

Superstudio, Atti Fondamentali, Educazione, Progetto 1, 1971 Collezioni MAXXI Architettura. Fondo Superstudio.

Ila Bêka & Louise Lemoine, La Maddalena, La Maddalena Chair, 2014. Sound and video installation. Courtesy Beka & Partners.

Paolo Bronstein, Temporary Structure, 2014. Ink and watercolor on paper. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Franco Noero, Torino.

Patrick Tuttofuoco, Revolving Landscape (San Paolo), 2006. Foto di Beppe Giardino.

-

Until January 6, 2016

Super Superstudio

curated by Andreas Angelidakis, Vittorio Pizzigoni and Valter Scelsi

produced by PAC with Silvana Editoriale

promoted by Comune di Milano – Cultura

supported by TOD’S

with the contribution of Alcantara and Vulcano

PAC

via Palestro 14, Milano

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.

Quicksearch

Categories

Calendar

|

|

November '15 |

|

||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | ||||||