Wednesday, February 26. 2014

Three years ago we published a post by Nicolas Nova about Salvator Allende's project Cybersyn. A trial to build a cybernetic society (including feedbacks from the chilean population) back in the early 70ies.

Here is another article and picture piece about this amazing projetc on Frieze. You'll need to buy the magazione to see the pictures, though!

-----

Via Frieze

Phograph of Cybersyn, Salvador Allende's attempt to create a 'socialist internet, decades ahead of its time'

This is a tantalizing glimpse of a world that could have been our world. What we are looking at is the heart of the Cybersyn system, created for Salvador Allende’s socialist Chilean government by the British cybernetician Stafford Beer. Beer’s ambition was to ‘implant an electronic nervous system’ into Chile. With its network of telex machines and other communication devices, Cybersyn was to be – in the words of Andy Beckett, author of Pinochet in Piccadilly (2003) – a ‘socialist internet, decades ahead of its time’.

Capitalist propagandists claimed that this was a Big Brother-style surveillance system, but the aim was exactly the opposite: Beer and Allende wanted a network that would allow workers unprecedented levels of control over their own lives. Instead of commanding from on high, the government would be able to respond to up-to-the-minute information coming from factories. Yet Cybersyn was envisaged as much more than a system for relaying economic data: it was also hoped that it would eventually allow the population to instantaneously communicate its feelings about decisions the government had taken.

In 1973, General Pinochet’s cia-backed military coup brutally overthrew Allende’s government. The stakes couldn’t have been higher. It wasn’t only that a new model of socialism was defeated in Chile; the defeat immediately cleared the ground for Chile to become the testing-ground for the neoliberal version of capitalism. The military takeover was swiftly followed by the widespread torture and terrorization of Allende’s supporters, alongside a massive programme of privatization and de-regulation. One world was destroyed before it could really be born; another world – the world in which there is no alternative to capitalism, our world, the world of capitalist realism – started to emerge.

There’s an aching poignancy in this image of Cybersyn now, when the pathological effects of communicative capitalism’s always-on cyberblitz are becoming increasingly apparent. Cloaked in a rhetoric of inclusion and participation, semio-capitalism keeps us in a state of permanent anxiety. But Cybersyn reminds us that this is not an inherent feature of communications technology. A whole other use of cybernetic sytems is possible. Perhaps, rather than being some fragment of a lost world, Cybersyn is a glimpse of a future that can still happen.

Tuesday, February 25. 2014

Via the guardian

-----

By Peter Bradshaw

Is our urban future bright or bleak? Peter Bradshaw provides a selection of celluloid cities you might consider moving to - or avoiding - if you are looking to relocate any time in the next 200 years or so.

METROPOLIS (1927) (dir. Fritz Lang)

Metropolis is the architectural template for all futurist cities in the movies. It has glitzy skyscrapers; it has streets crowded with folk who swarm through them like ants; most importantly, it has high-up freeways linking the buildings, criss-crossing the sky, on which automobiles and trains casually run — the sine qua non of the futurist city. Metropolis is a gigantic 21st-century European city state, a veritable utopia for that elite few fortunate enough to live above ground in its gleaming urban spaces. But it’s awful for the untermensch race of workers who toil underground. Photograph: Ronald Grant Archive.

ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK (1981) (dir. John Carpenter)

Made when New York still had its tasty crime-capital reputation, Carpenter’s dystopian sci-fi presents us with the New York of the future, ie 1988, and imagines that the authorities have given up policing it entirely and simply walled the city off and established a 24/7 patrol for the perimeter, re-purposing the city as a licensed hellhole of Darwinian violence into which serious prisoners will just be slung and then forgotten about, to survive or not as they can. Then in 1997 the President’s plane goes down in the city and he has to be rescued. New York is re-imagined as a lawless, dimly-lit nightmare. Not a great place to live. Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext/MGM.

LOGAN’S RUN (1976) (dir. Michael Anderson) This is set in an enclosed dome city in the post-apocalyptic world of 2274. It looks like an exciting, go-ahead place to live and it’s certainly a great city for twentysomethings. There are the much-loved overhead monorails and people wear the sleek, figure-hugging leotards, unitards, and miniskirts. The issue is that people here get killed on their 30th birthday. Some people escape the dome city to find themselves in deserted Washington DC, which is a wreck by comparison. Photograph: Ronald Grant Archive

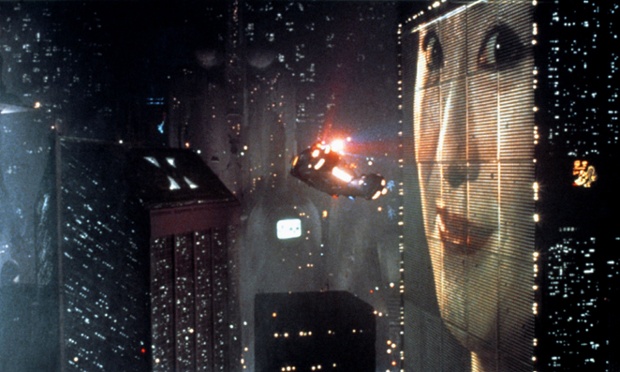

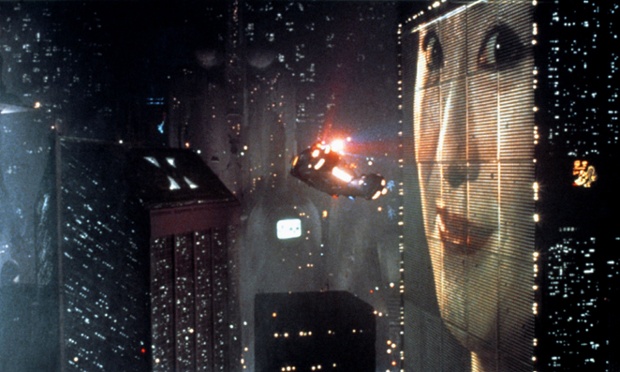

BLADE RUNNER (1982) (dir. Ridley Scott)

This film presents us with Los Angeles 2019, a daunting megalopolis in which “replicants” may be hiding out — that is, super-sophisticated organically correct servant-robots indistinguishable from actual humans, who have defied the rules forbidding them to enter the city. Special cops called “blade runners” have to hunt them down. The city is colossal, headspinningly big, a virtual planet itself; it is cursed with terrible weather, with very rainy nights, but interestingly hints at the economic and cultural might of Asia with loads of billboard ads from the Far East. Again, the crime figures may make this city a bit of a no-no. Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext/Warner Bros.

ALPHAVILLE (1965) (dir. Jean-Luc Godard)

Alphaville is a city on a distant planet and a very grim place, subject to Orwellian repression and thought-control by its tyrannical ruler, an AI computer called Alpha 60. The city is seen largely at night, with drab buildings which have neither the techno-futurist furniture nor the obvious decay that you expect from sci-fi dystopia. This is because it was filmed in 1960s inner-city Paris: Alphaville is the French capital’s intergalactic banlieue twin-town. Again, this isn’t a great movie-futurist city to settle down in, although the property prices are probably reasonable. Photograph: British Film Institute.

THINGS TO COME (1936) (dir. William Cameron Menzies)

The state-of-the-urban-art British city of Everytown is here shown, from the year 1940 to 2036. A pleasant place is entirely ruined by a catastrophic war which lasts decades and plunges the city into the familiar future-city mode B: post-apocalyptic chaos. The city is basically rubble and hideous gas and poison warfare have made matters worse. Cynical and ambitious types aspire to control Everytown, but the place has been made the nexus for human vanity and ambition. Another future city with a bad reputation. Photograph: ITV/REX

AKIRA (1988) (dir. Katsuhiro Otomo)

Neo-Tokyo, 2019. This gigantic city is like an impossibly huge sentient robot life-form in itself. It was built to replace the “old” Tokyo which was immolated in a huge explosion. Now the new city is a teeming, prosperous, hi-tech place but more than a little anarchic and strange, always apparently on the verge of breaking down, and also incubating weird spiritual forces. Biker gangs do battle there: the Capsules versus the Clowns. An exciting place to settle down — seen in the right light.

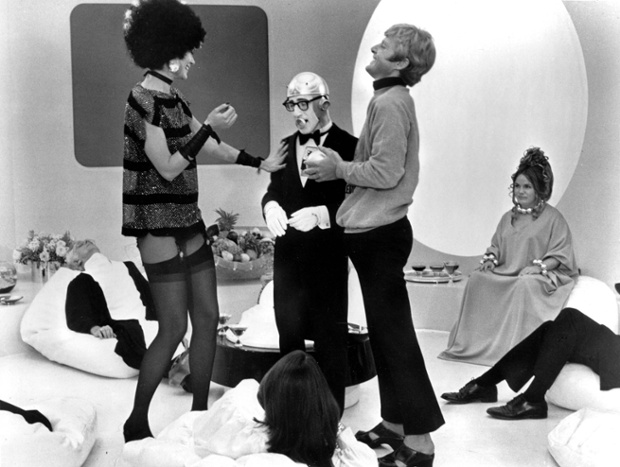

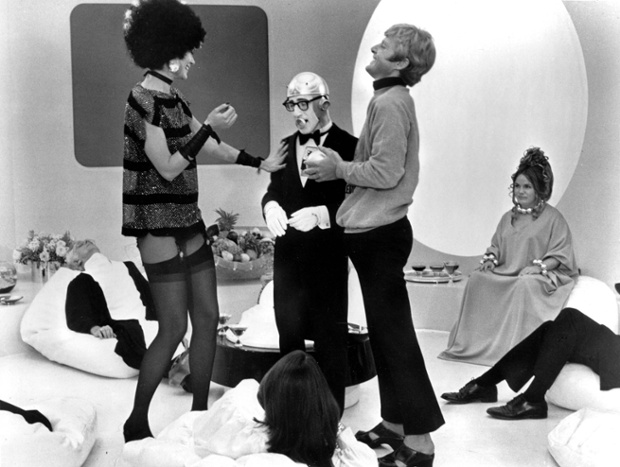

SLEEPER (1973) (dir. Woody Allen)

Greenwich Village in 2173 is a startling place: part of the 22nd-century police state in which the people are kept in a placid condition with brainwashing. A nerdy bespectacled health-food-store owner, who has been cryogenically frozen in 1973 and awakened into this brave new world, must now battle against the forces of mind-control. This Huxleyan futureworld actually looks rather pleasant, the architecture, décor and public transport are all not bad, and these are cities with “Orgasmatrons” which are guaranteed to give sexual satistfaction to those inside them. Photograph: Ronald Grant Archive

MINORITY REPORT (2002) (dir. Steven Spielberg)

Washington in the year 2054 is eerie and disorientating: a shadowy, noir-y city which appears often to be underlit, and yet it certainly enjoys the benefits of the digital revolution. Moving posters are the norm (actually, they’re commonplace in cities now) and images, text and data on screens can be manipulated with extraordinary ease. The populace is policed by a specialist unit called “PreCrime” which can predict and pre-empt the lawbreakers, but their prophetic dominance has created a spiritual malaise in the city’s atmosphere.

BABELDOM (2013) (dir. Paul Bush) This cult cine-essay by Paul Bush is all about a fictional mega-city called Babeldom. Where this city is supposed to be is a moot point. It is everywhere and nowhere. At first it is glimpsed through a misty fog: it is the city of Babel imagined by the elder Breughel in his Tower Of Babel. Then Bush gives us glimpses of a place made up of actual cities and then computer graphic displays take us through how a city develops its distinctive lineaments and growth patterns. Of all the future-cities on this list, Babeldom is probably the weirdest.

This article was amended on 30 January 2014 to correct the spelling of Paul Bush's name.

Tuesday, February 04. 2014

Via #algopop

-----

By Plummer Fernandez

Love in the time of algorithms by Dan Slater. A book about the online dating industry. I think the title of this book alone makes this relevant to #algopop.

Also researchers at the University of Iowa are developing an algorithm that much like Netflix, will recommend partners for dating based on data-mining rather than user input. The concept is based on the assumptions that a user’s self-curated profile is not entirely truthful, and that he or she 'may not know themselves well enough to know their own tastes in the opposite sex', so algorithms could potentially get to know the real you, and your potential partner, through your dating-site browsing habits.

Via Creative Applications

-----

By Lauren McCarthy & Kyle McDonald

AIT (“Social Hacking”), taught for the first time this semester by Lauren McCarthy and Kyle McDonald at NYU’s ITP, explored the structures and systems of social interactions, identity, and self representation as mediated by technology. The semester was spent developing projects that altered or disrupted social space in an attempt to reveal existing patterns or truths about our experiences and technologies, and possibilities for richer interactions.

The class began by exploring the idea of “social glitch”, drawing on ideas from glitch theory, social psychology, and sociology, including Harold Garfinkel’s breaching experiments, Stanley Milgram’s subway experiments, and Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical analysis of social interaction. If “glitch” describes when a system breaks down and reveals something about its structure or self in the process, what might this look like in the context of social space?

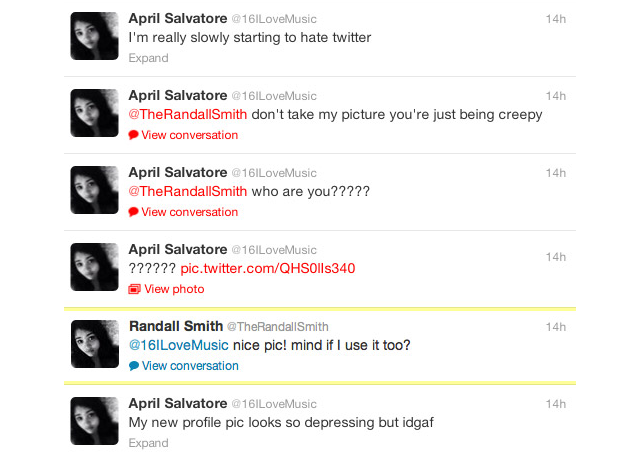

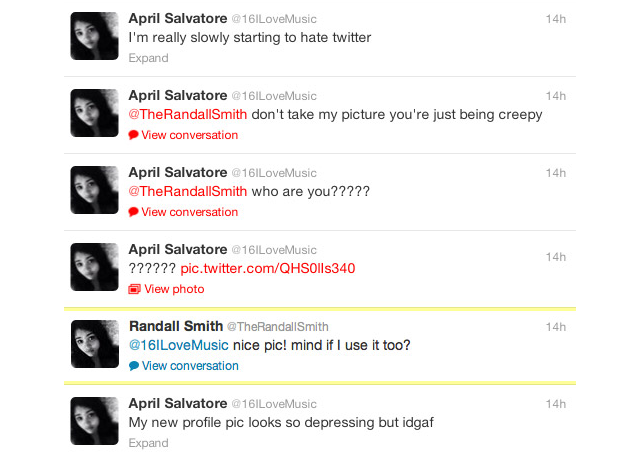

Bill Lindmeier wrote a Ruby script using the Twitter Stream API to listen for any Tweets containing “new profile pic.” When a Tweet was posted the script would download the user’s profile image, upload it to his own account and then reply to the user with a randomly selected Tweet, like “awesome pic!”. The reactions ranged from humored to furious.

Along similar lines, Ilwon Yoon implemented a script that searched for Tweets containing “I am all alone” and replied with cute images obtained from a Google image search and “you are not alone” text.

Mack Howell built on the in-class exercise of asking strangers to borrow their phone then doing something unexpected with it, asking to take pictures of strangers’ browsing history.

The class next turned it’s attention to social automation and APIs, and the potential for their creative misuse.

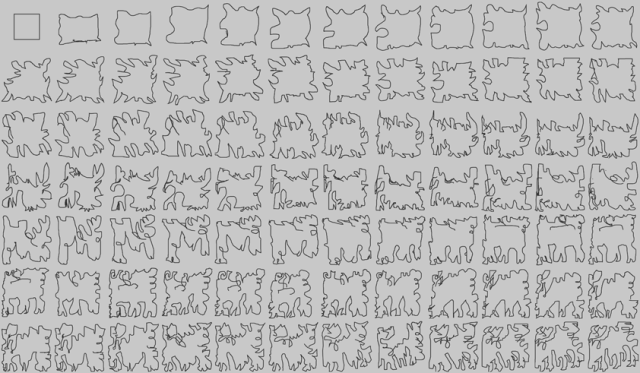

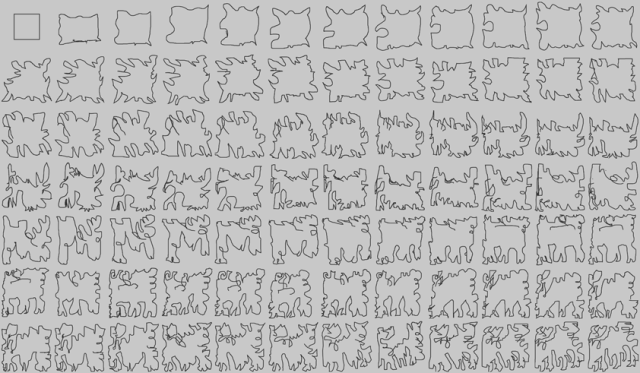

Gal Sasson used the Amazon Mechanical Turk API to create collaborative noise, creating a chain where each turker was prompted to replicate a drawing from the previous turker, seeding the first turker with a perfect square.

Mack Howell used the Google Street View Image API to map out the traceroutes from his location to the data centers of the his most frequently visited IPs.

In another assignment, students were prompted to create an “HPI” (human programming interface) that allowed others to control some aspect of their lives, and perform the experiment for one full week.

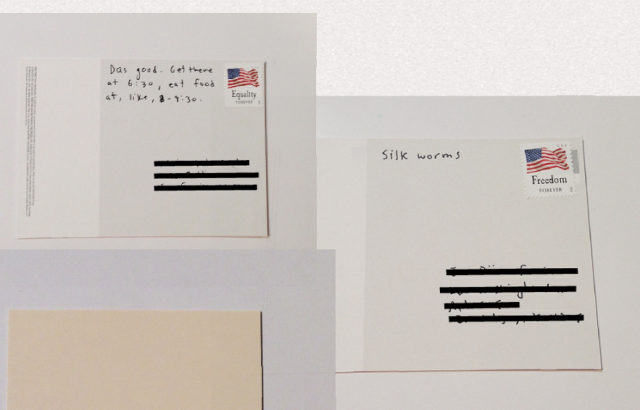

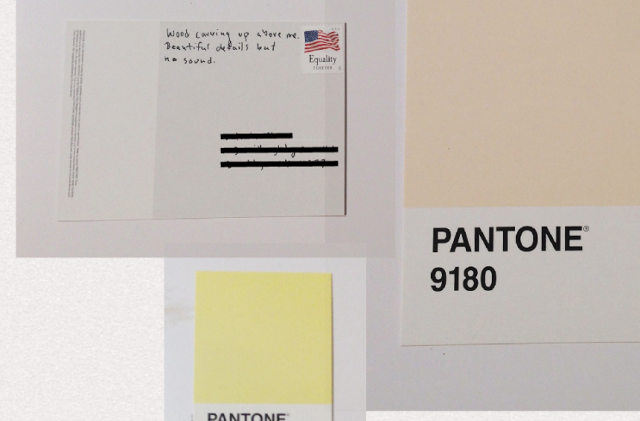

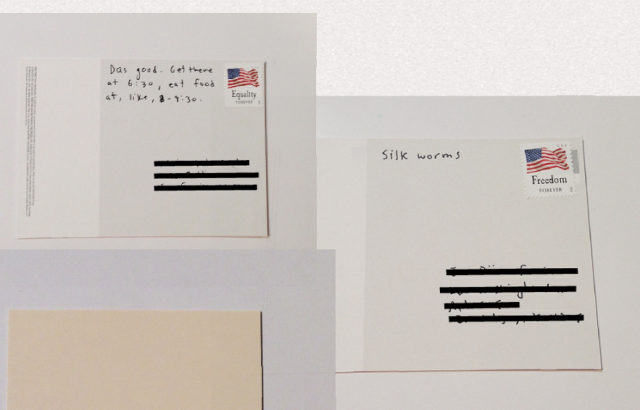

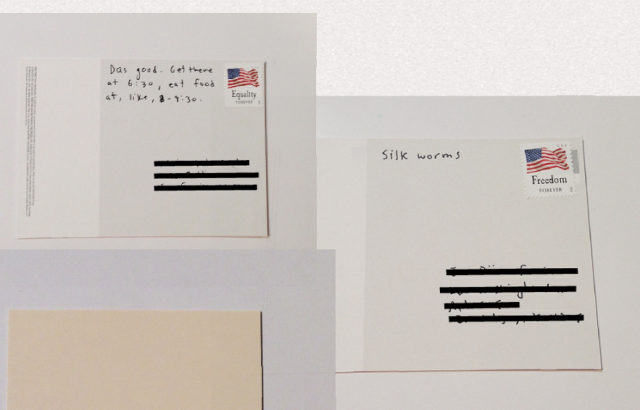

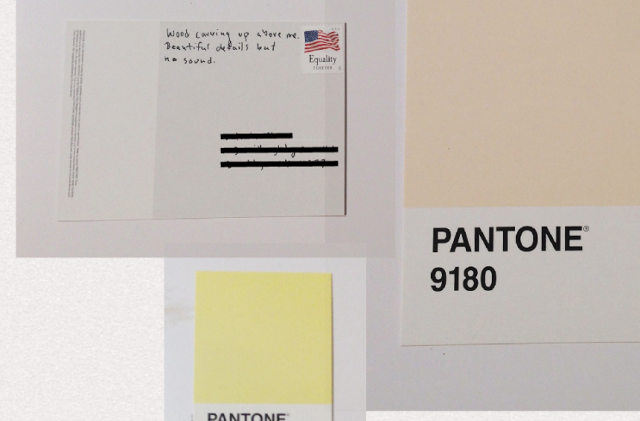

Anytime an email or Twitter direct message was sent to Ben Kauffman with the hashtag #brainstamp and a mailing address, he would get an SMS with the information and promptly right down on a postcard whatever was in his head at that exact moment. He would then mail the thoughts, at turns surreal and mundane, to the awaiting recipient. An alternative to normal social media, Ben challenged us to find ways to be more present while documenting our lives.

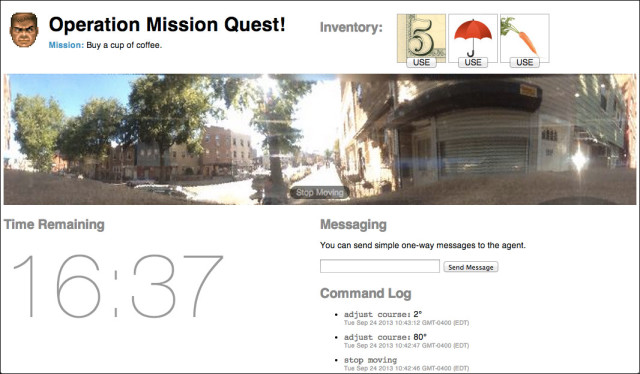

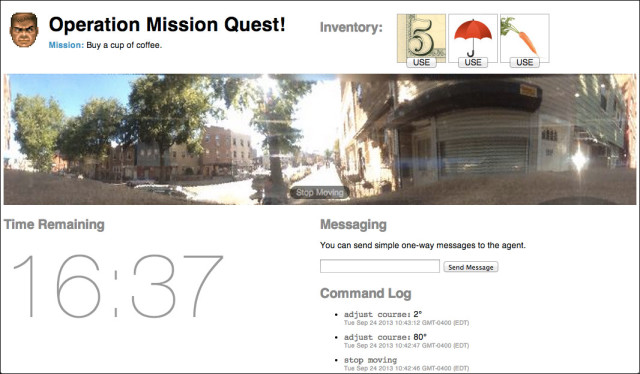

Bill Lindmeier invited his friends to control his movements in realtime through a Google-street-view-esque video interface, and asked them to complete a simple mission: Buy some coffee in under 20 minutes. The tools at their disposal: $5, an umbrella and a carrot.

Mack Howell created a journal written by Amazon Mechanical Turk workers, asking them to generate diary entries based on OpenPaths data sent automatically as he moved around.

In a project called My Friends Complete Me, Su Hyun Kim posted binary questions on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and let her friends collective opinion determine her life choices, including deciding whether to change her last name when she got married.

A couple weeks were spent having focused discussions about security, privacy, and surveillance, including topics like quantified self, government surveillance and historical regimes of naming, and readings from Bruce Schneier, Evgeny Morozov and Steve Mann. In parallel, students were asked to examine their own social lives and compulsively document, share, intercept, impersonate, anonymize and misinterpret.

Mike Allison explored our voyeuristic nature and cultural craving for surveillance, allowing users to watch someone watch someone who may be watching them. In order to watch, users must lend their own camera to the system.

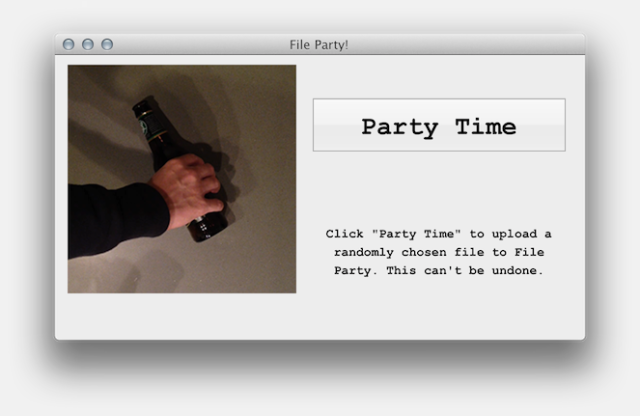

Bill Lindmeier created an app called File Party, a repository of files that have been randomly selected and uploaded from peoples’ hard-drive. In order to view the files, you have to upload one yourself.

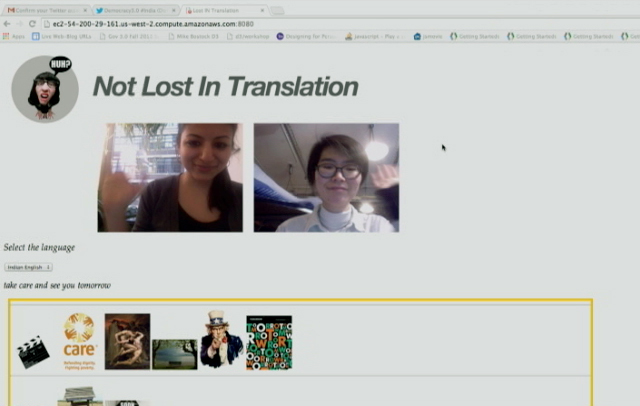

In a unit on computer vision and linguistic analysis, students were paired up and asked to create a chat application that provided a filter or adapter that improved their interaction.

Realizing how much is lost in translation and accents, Tarana Gupta and Hanbyul Jo developed a video chat tool which allows users to talk in their respective language and and displays in real-time text and images corresponding to what is being said.

In FlapChat, Su Hyun Kim and Gal Sasson rethought the way we interact with the web camera, allowing users to flap their arms to fly around a virtual environment while chatting.

Overall, the most successful moments in the class were the ones where students had an opportunity to examine an otherwise common technology or interaction from a new perspective. Short in-class exercises like “ask a stranger to use their phone, and do something unexpected” gave students a reference point for discussion. The “HPI” assignment gave students an unusual challenge of “performing” something for a week, lead to its own set of difficulties and realizations that are distinct from purely technical or aesthetic exercises. On the first day of class a contract was handed out requiring that students respect others’ positions in class, and take responsibility for any actions outside of class. This created a unfamiliar atmosphere and opened up the students to question their freedoms and responsibilities towards each other.

In the future, each two- or three-week section might be expanded to fit a whole semester. Of particular interest were the computer vision, security and surveillance, and mobile platforms sections. Leftover discussion from security and surveillance spilled into the next week, and assignments for mobile platforms could have been taken far beyond the proof-of-concept or design-only stages.

More information about the class, including the complete syllabus, reading lists, and some example code, is available on GitHub.

A condensed version of this class will be taught in January at GAFFTA in San Francisco, details will be announced soon with more information here.

About the Tutors:

Kyle McDonald is a media artist who works with code, with a background in philosophy and computer science. He creates intricate systems with playful realizations, sharing the source and challenging others to create and contribute. Kyle is a regular collaborator on arts-engineering initiatives such as openFrameworks, having developed a number of extensions which provide connectivity to powerful image processing and computer vision libraries. For the past few years, Kyle has applied these techniques to problems in 3D sensing, for interaction and visualization, starting with structured light techniques, and later the Kinect. Kyle’s work ranges from hyper-formal glitch experiments to tactical and interrogative installations and performance. He was recently Guest Researcher in residence at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media, Japan, and is currently adjunct professor at ITP.

http://kylemcdonald.net

Lauren McCarthy is an artist and programmer based in Brooklyn, NY. She is adjunct faculty at RISD and NYU ITP, and a current resident at Eyebeam. She holds an MFA from UCLA and a BS Computer Science and BS Art and Design from MIT. Her work explores the structures and systems of social interactions, identity, and self-representation, and the potential for technology to mediate, manipulate, and evolve these interactions. She is fascinated by the slightly uncomfortable moments when patterns are shifted, expectations are broken, and participants become aware of the system. Her artwork has been shown in a variety of contexts, including the Conflux Festival, SIGGRAPH, LACMA, the Japan Media Arts Festival, the File Festival, the WIRED Store, and probably to you without you knowing it at some point while interacting with her.

http://lauren-mccarthy.com

Monday, February 03. 2014

An interesting call for papers about "algorithmic living" at University of California, Davis.

Via The Programmable City

-----

Call for papers

Thursday and Friday – May 15-16, 2014 at the University of California, Davis

Submission Deadline: March 1, 2014 algorithmiclife (at) gmail.com

As algorithms permeate our lived experience, the boundaries and borderlands of what can and cannot be adapted, translated, or incorporated into algorithmic thinking become a space of contention. The principle of the algorithm, or the specification of the potential space of action, creates the notion of a universal mode of specification of all life, leading to discourses on empowerment, efficiency, openness, and inclusivity. But algorithms are ultimately only able to make intelligible and valuable that which can be discretized, quantified, operationalized, proceduralized, and gamified, and this limited domain makes algorithms necessarily exclusive.

Algorithms increasingly shape our world, our thought, our economy, our political life, and our bodies. The algorithmic response of NSA networks to threatening network activity increasingly brings privacy and political surveillance under algorithmic control. At least 30% of stock trading is now algorithmic and automatic, having already lead to several otherwise inexplicable collapses and booms. Devices such as the Fitbit and the NikeFuel suggest that the body is incomplete without a technological supplement, treating ‘health’ as a quantifiable output dependent on quantifiable inputs. The logic of gamification, which finds increasing traction in educational and pedagogical contexts, asserts that the world is not only renderable as winnable or losable, but is in fact better–i.e. more effective–this way. The increased proliferation of how-to guides, from HGTV and DIY television to the LifeHack website, demonstrate a growing demand for approaching tasks with discrete algorithmic instructions.

This conference seeks to explore both the specific uses of algorithms and algorithmic culture more broadly, including topics such as: gamification, the computational self, data mining and visualization, the politics of algorithms, surveillance, mobile and locative technology, and games for health. While virtually any discipline could have something productive to say about the matter, we are especially seeking contributions from software studies, critical code studies, performance studies, cultural and media studies, anthropology, the humanities, and social sciences, as well as visual art, music, sound studies and performance. Proposals for experimental/hybrid performance-papers and multimedia artworks are especially welcome.

Areas open for exploration include but are not limited to: daily life in algorithmic culture; gamification of education, health, politics, arts, and other social arenas; the life and death of big data and data visualization; identity politics and the quantification of selves, bodies, and populations; algorithm and affect; visual culture of algorithms; algorithmic materiality; governance, regulation, and ethics of algorithms, procedures, and protocols; algorithmic imaginaries in fiction, film, video games, and other media; algorithmic culture and (dis)ability; habit and addiction as biological algorithms; the unrule-able/unruly in the (post)digital age; limits and possibilities of emergence; algorithmic and proto-algorithmic compositional methods (e.g., serialism, Baroque fugue); algorithms and (il)legibility; and the unalgorithmic.

Please send proposals to algorithmiclife (at) gmail.com by March 1, 2014.

Decisions will be made by March 8, 2014.

|