Monday, December 26. 2011

Via ArchDaily

-----

de Karissa Rosenfield

Tunisian Revolution via cjb22 on flickr - http://www.flickr.com/photos/cjb22222222/5373435731/

It began on December 17th, 2010, when 26-year-old street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi drenched himself in paint thinner and lit a match in front of the provincial-capital building in Tunisia. Mannoubia Bouazizi stated, “My son set himself on fire for dignity.” Her 16-year-old daughter added, “In Tunisia, dignity is more important than bread.”

All over the world, the protestors of 2011 have stood-up for fairness and freedom. “Do-it-yourself democratic politics became globalized, and a real live protest went massively viral.” Authoritarian acts of violence and forceful evictions from “public” squares further exposed what the protestors were fighting for. In effort to honor the individuals who have made the greatest impact on our world during these past twelve months, TIME has named the 2011 person of the year as “The Protester”.

Day 36 Occupy Wall Street © David Shankbone

“Public” space has played an important role in this fight for social justice. Occupy Wall Street’s (OWS) eviction from the privately owned public space (POPS) Zuccotti Park, raised awareness on the privatization of the city and the illusion of being public. Architects became actively involved, assisting the development of temporary cities to support the movement, while questioning the “cult of homeownership” and the architect’s role in evolving the idea of housing.

Day 60 Occupy Wall Street © David Shankbone

“Among the ruins left behind by the eviction of bodies and the demolition of tents in lower Manhattan are the ruins of what the philosopher Hannah Arendt called the “space of public appearance.” Ever since the ancient Greeks, who served as Arendt’s model, the right to participate in this space has been conditional on the possession of personal wealth. One of the many contradictory functions of the modern state, addressed politically by unionized workers and by civil rights activists alike, has been to redistribute wealth — that is, to mediate the distribution of resources, services, and value. Any structural alternative must ultimately come to terms with this mediating function.” – Design Observer: Occupy: The Day After

Tanks in front of the Qasba in Tunisia © Gladys Martínez López

Citizens across the world continue to fight for social justice, occupying the streets and inhabiting public space in efforts to achieve significant change. Coverage of the indignados taking back Puerta del Sol in Madrid exclaimed, “The sun has risen. The people cried. The square is ours.”

Indignados taking back the square in Madrid © Jesus Solana

Follow this link to the must-read TIME Cover Story: The Protestor.

Personal comment:

"The protester" will be our last post on rblg for 2011, before we leave to the Alps and the snow for a couple of days!

Best whishes to all.

Friday, December 16. 2011

The inside of the greenhouse will be anything but ordinary. Four-metre-high stacks of growing trays on motorized conveyors will ferry plants up, down and around for watering, to capture the sun’s rays and then move them into position for an easy harvest. The array will produce about the same amount of produce as 6.4 hectares (16 acres) of California fields, according to Christopher Ng, chief operating officer of Valcent.

Personal comment:

Robotized salads!

Thursday, December 08. 2011

Via GOOD

-----

de Chappell Ellison

American Airlines’ filing for bankruptcy protection last week provoked surprisingly little reaction from the media or regular travelers. Perhaps we've grown immune to the whims of the rapidly changing airline industry, where the past three decades have seen the merging and dissolution of countless carriers.

Yet it wasn’t so long ago that air travel was synonymous with Americans’ visions of the future, when purchasing a boarding pass meant participating in the ever-expanding dreams of post-war America. Somewhere along the way, the optimistic glow surrounding air travel faded away, leaving a beleaguered industry that causes stress and frustration, not awe, for American travelers. And the dissolution of the industry was reflected in airports, where architectural innovation was quickly pushed aside to make room for quick, easy fixes.

The TWA Flight Center at John F. Kennedy International Airport was designed in 1962 by Eero Saarinen as a crown jewel of Modernist architecture that is still referred to as the ultimate symbol of the jet era. Forty years later, as parts of Saarinen's terminal were being demolished, construction began on Lord Norman Foster's new Terminal 3 at Beijing's Capital International Airport. Airport innovation has fled to developing countries, where the promise of travel is only beginning to achieve its glow.

Airport architecture of the jet era was defined by modernism, intended to be the stylistic cure-all for the world with its beautiful, clean structures that shunned ornament. At first, airports and modernism made perfect bedfellows—the hippest style in the world intertwined with the optimistic, promising future of air travel, which was first coming of age in the late 1950s. Together, the two created the jet era, the vision of air travel propagated through the Pan Am mystique and still recounted by baby boomers today. For those who traveled during this time, the luxury of the jet era cannot be understated.

But the hype didn't last long—by the 1970s, the jet era was over, and modernist architecture was increasingly labeled sterile, cold, and elitist. The post-war halo faded, taking modernism, World's Fairs, and futuristic visions with it. The country was mired in an energy crisis, causing nearly every teetering U.S. airline to tip into the red. Flights were hovering at 40 percent passenger capacity, while Pan Am sought a bailout from the Shah of Iran. Adding a few hijackings created perhaps the darkest days of the American airline industry, with Big Brother intruding into the austere, modernist terminals. "Terminals sprouted long tunnels, corridors, and labyrinthine extensions,” Janna Eggebeen writes in Airport Age: Architecture and Modernity in America. “Formerly open interiors were now darkened, partitioned and cordoned off. Choke points and security cameras further regulated but also deteriorated the airport experience. The air terminal now exuded the oppressiveness, dehumanization, authoritarianism, and tedium of late modern life."

As the airlines hurtled toward bankruptcy, the federal government watched nervously. In 1976, Congress had sunk billions into consolidating the failing railroad companies to create Conrail, and representatives realized that an intervention would be necessary to avoid the same costly fate for the airlines. So in 1978, Congress introduced the Airline Deregulation Act, allowing carriers to engage in competitive pricing for the first time—previously, the government had approved all airfares and flight schedules, which kept fares high and ridership low. Deregulation democratized air travel: Even with inflation adjusted, airfares of have fallen 25 percent since 1991, and planes now fly at an average 74 percent of capacity.

Airports struggled to adapt to the skyrocketing number of passengers. Like patching a flat tire, they tacked on satellite terminals and endless hallways replete with confusing signage. The architect and his optimistic visions were lost in the shuffle. "As airports grew in size and complexity… the architect became part of an expert team,” Eggebeen writes. Design was relegated to a supporting role in favor of a "make do and mend" approach.

Designers remain on the fringes of the air travel industry, attacking the symptoms of the problem one by one: Mobile apps to address boarding passes, checked luggage, and airport maps, for example, create a sort of traveler's ibuprofen that temporarily alleviates stress. Creating an app or renovating a terminal can’t solve the root problems. But with such a large and diverse cast of characters—air carrier employees, TSA officers, retail cashiers, baggage handlers—a complete overhaul is daunting.

And that’s exactly the problem: Design thinking, the phrase that so boldly offers itself in blogs and newspapers as the answer to all of our problems, becomes timid when faced with large, established systems. Design thinking can easily resolve the problem of getting water from one village to the next, but what if the two villages are already connected by a massive, faulty sewage system, controlled by scores of companies who have declared bankruptcy and switched ownership more than once, and are further thwarted by the objectives of third parties?

Our once-optimistic vision of the future of flight still permeates the terminals of America's oldest airports—seen in side-by-side people movers, revolving luggage carousels, and lounge chairs made in the by-gone modern era. They serve as reminders of air travel’s golden age and offer hope of a brighter future. The construction of Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport’s Terminal D in 2005 breathed life back into the system, proving that American air travel could once again have some semblance of opulence. The air travel industry may not have bottomed out yet, but Terminal D might represent the still-tiny light at the end of the tunnel. With 2 million square feet of open, sunny hallways adorned with fascinating art installations, Terminal D is a respite from DFW’s older, musty corridors, where the stress of lost luggage and delayed departures hangs in the air. Any airport that can bring even a sliver of joy back to the journey of the traveler is a step in the right direction.

Photo via (cc) Flickr user jronaldlee

Via ArchDaily

-----

de Karissa Rosenfield

Via tedprize.org

For the first time in history, the TED Prize winner is not an individual, but an idea that greatly impacts the future of planet Earth… and the winner is The City 2.0. The City 2.0 is the city of the future, a future in which more than ten billion people are dependent on. The idea is not a “sterile utopian dream” but rather a “real-world upgrade tapping into humanity’s collective wisdom.” More urban living space will be constructed over the next 90 years than all prior centuries combined, so it is time to get it right.

Continue reading for more information on The City 2.0 and details on how you can participate.

Provided by the TED Prize press release:

The City 2.0 promotes innovation, education, culture, and economic opportunity.

The City 2.0 reduces the carbon footprint of its occupants, facilitates smaller families, and eases the environmental pressure on the world’s rural areas.

The City 2.0 is a place of beauty, wonder, excitement, inclusion, diversity, life.

The City 2.0 is the city that works.

Each year, TED Prize is awarded to an “exceptional individual” who receives $100,000 and “One Wish to Change the World.” Visionaries from around the globe will be given the collective opportunity to craft one wish for The City 2.0.

Back in 2006, TIME’s person of the year was YOU. It became evident that we are in charge of shaping our own destiny and we are one collective whole. If you wish to contribute an idea for The City 2.0, write to tedprize@ted.com and join the conversation here.

The wish will be announced on February 29th, 2012 at the TED Conference in Long Beach, California.

“On a Leap Year date, we have the chance, collectively, to take a giant leap forward.”

Reference: TED Prize, TIME Magazine

Wednesday, December 07. 2011

Via BLDGBLOG

-----

(...)

5) "Imagine a lush forest: silent but for the chirping of birds flying through a dense canopy overhead, and damp, aromatic earth underfoot. Now picture a mountain of incinerated trash, 12 million tons of what was once a toxic heap of rotting fish and vegetables, old clothes, broken furniture, diapers and all manner of discarded items." This describes a new project by architect Tadao Ando called the Sea Forest. The Sea Forest "will transform 88 hectares of reclaimed land, a 30-meter deep mound of alternating layers of landfill, into a dense forest of nearly half a million trees" in Tokyo Bay. Ando adds that it is also an experiment in climate-engineering, or weather control as the future of urban design: "not only will [the forest] become a refreshing retreat for stressed out city workers, it will also create a cool ocean breeze to sweep through the capital and cool its sweaty denizens in summer."

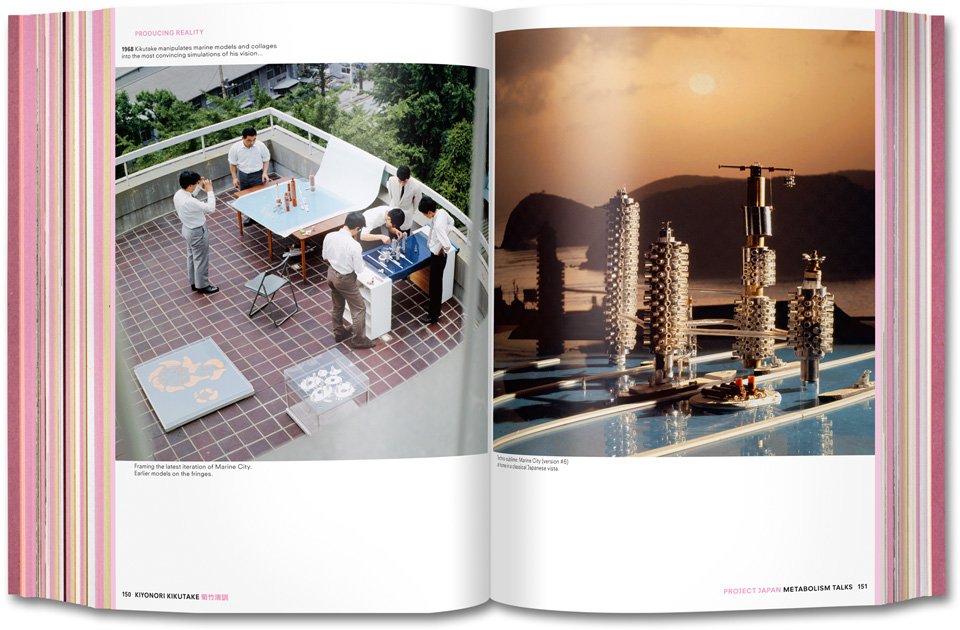

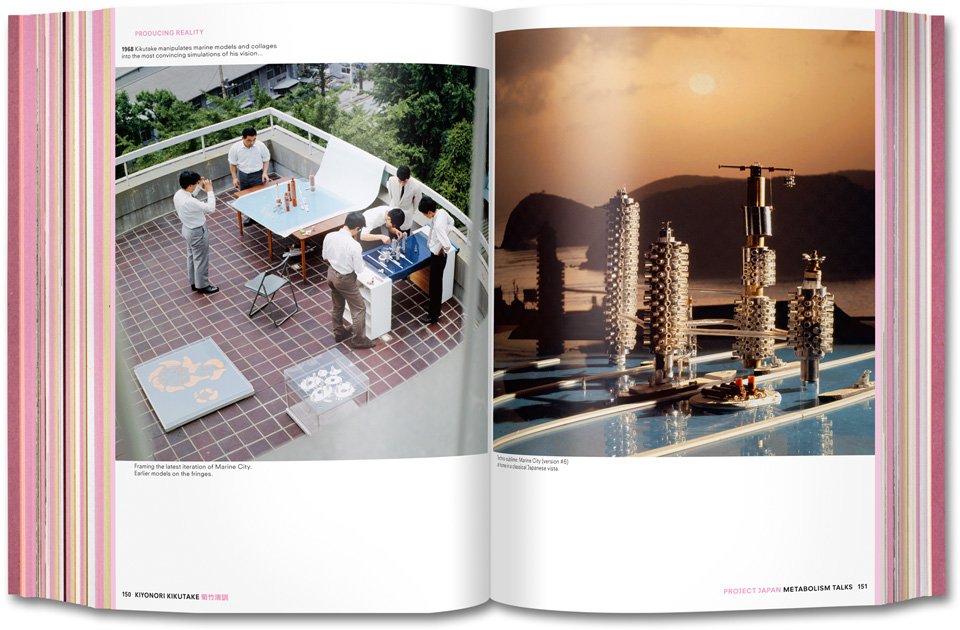

[Images: Spreads from Project Japan, courtesy of Taschen]. [Images: Spreads from Project Japan, courtesy of Taschen].

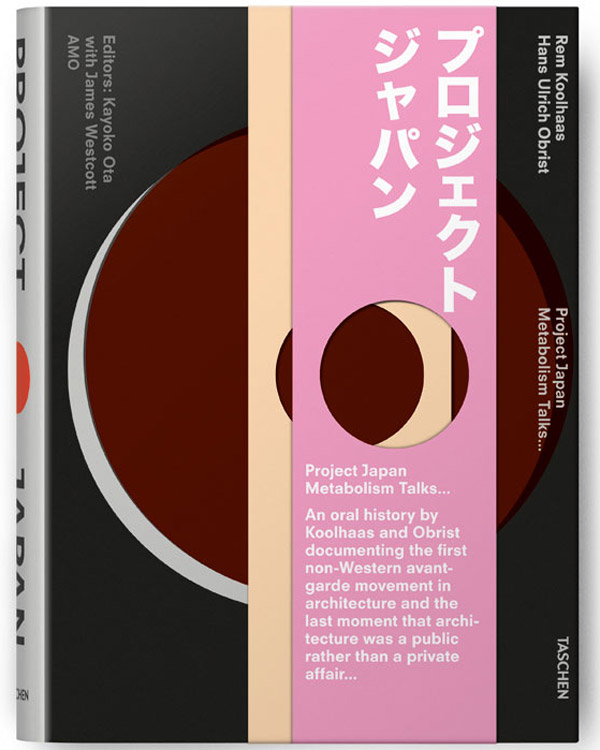

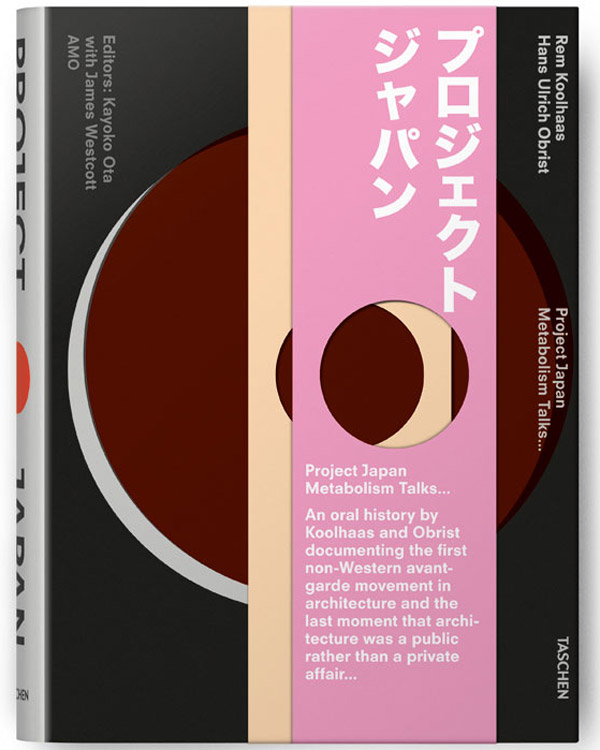

6) The new book Project Japan by Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist is an incredible document, in both physical and intellectual terms. The design, by Irma Boom, is gorgeous, and the contents—consisting of long, illustrated interviews with such figures as Arata Isozaki, Kenzo Tange's Tange Lab, Kiyonori Kikutake, Kisho Kurokawa, and many others, scattered amongst historical imagery and present-day site photos—offer a fascinating oral history of the Metabolist movement. As Koolhaas sums it up, Metabolism offered "a manifesto for the total transformation of the country" based on three specific principles. Still quoting Koolhaas:

a) The archipelago has run out of space: mostly mountainous, the surfaces fit for settlement are subdivided in microscopic, centuries old patchworks of ownership

b) Earthquakes and tsunamis make all construction precarious; urban concentrations such as Tokyo and Osaka are susceptible to potentially devastating wipeouts [ed. note: cf. today's calls for a "back-up Tokyo"]

c) Modern technology and design offer possibilities for transcending Japan's structural weakness, but only if they are mobilized systematically, almost militaristically, searching for solutions in every direction: on the land, on the sea, in the air...

Architecture thus becomes the literal geopolitical extension of the state, constructing new territory—such as floating forests and artificial islands—over which to govern. It's a kind of proactive gerrymandering, we might say: not redesigning the district map, but constructing new districts. In any case, I recommend the book.

(...)

|

[Images: Spreads from Project Japan, courtesy of

[Images: Spreads from Project Japan, courtesy of