Via BLDGBLOG

-----

(...)

5) "Imagine a lush forest: silent but for the chirping of birds flying through a dense canopy overhead, and damp, aromatic earth underfoot. Now picture a mountain of incinerated trash, 12 million tons of what was once a toxic heap of rotting fish and vegetables, old clothes, broken furniture, diapers and all manner of discarded items." This describes a new project by architect Tadao Ando called the Sea Forest. The Sea Forest "will transform 88 hectares of reclaimed land, a 30-meter deep mound of alternating layers of landfill, into a dense forest of nearly half a million trees" in Tokyo Bay. Ando adds that it is also an experiment in climate-engineering, or weather control as the future of urban design: "not only will [the forest] become a refreshing retreat for stressed out city workers, it will also create a cool ocean breeze to sweep through the capital and cool its sweaty denizens in summer."

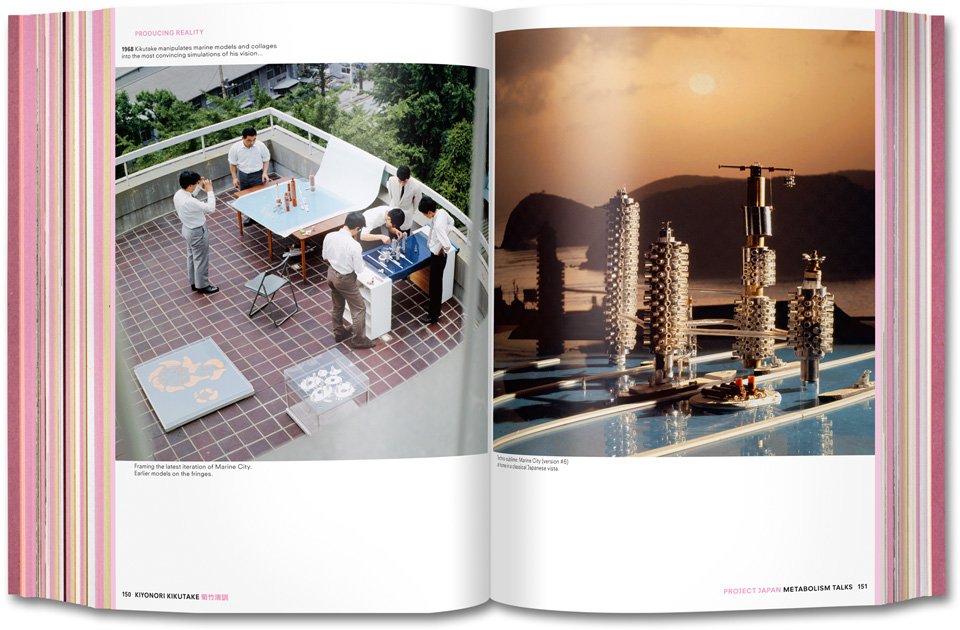

[Images: Spreads from Project Japan, courtesy of Taschen].

[Images: Spreads from Project Japan, courtesy of Taschen].

6) The new book Project Japan by Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist is an incredible document, in both physical and intellectual terms. The design, by Irma Boom, is gorgeous, and the contents—consisting of long, illustrated interviews with such figures as Arata Isozaki, Kenzo Tange's Tange Lab, Kiyonori Kikutake, Kisho Kurokawa, and many others, scattered amongst historical imagery and present-day site photos—offer a fascinating oral history of the Metabolist movement. As Koolhaas sums it up, Metabolism offered "a manifesto for the total transformation of the country" based on three specific principles. Still quoting Koolhaas:

a) The archipelago has run out of space: mostly mountainous, the surfaces fit for settlement are subdivided in microscopic, centuries old patchworks of ownership

b) Earthquakes and tsunamis make all construction precarious; urban concentrations such as Tokyo and Osaka are susceptible to potentially devastating wipeouts [ed. note: cf. today's calls for a "back-up Tokyo"]

c) Modern technology and design offer possibilities for transcending Japan's structural weakness, but only if they are mobilized systematically, almost militaristically, searching for solutions in every direction: on the land, on the sea, in the air...

Architecture thus becomes the literal geopolitical extension of the state, constructing new territory—such as floating forests and artificial islands—over which to govern. It's a kind of proactive gerrymandering, we might say: not redesigning the district map, but constructing new districts. In any case, I recommend the book.

(...)

[Images: Spreads from Project Japan, courtesy of

[Images: Spreads from Project Japan, courtesy of