Wednesday, October 27. 2010

Bioplastic Made from Poop, for a Profit!

Via GOOD

-----

by Alex Goldmark

Sometimes you can take two problems, add them together, and get a win-win solution. In this case, here are the two problems: First, as cities expand we create more waste and more sewage, and we don’t have any really good plan for it. And second, we keep making more and more plastic that never goes away, filling landfills or swimming in oceanic garbage patches. So, what’s the natural solution? Why not turn the poop into plastic that biodegrades? Simple, right? Actually, yes. It turns out it is.

Ryan Smith is CTO of Micromidas, and he turns poop into plastic for a living. “We take raw sewage from a waste water treatment plant and we convert it to biodegradable plastic.” He says it is “just a series of tanks, nothing complicated or fancy about it. Nothing that is technically too difficult.” That’s because he gets bacteria to do the hard work for him, and that’s the novelty of his product. Finding the bacteria, and mixing them up into the right combination, that’s a different story.

Right now, most plastic comes from petroleum. So as you tear open that new SD card from its packaging, or toss out the packing foam from your last Amazon order, you are, in essence consuming oil. There are various sugar- or corn-based bioplastics on the market already. (You can even follow this You Tube video and try to make your own.) These starch-based plastics solve the problem of living forever in a landfill or garbage patch, but if produced at the volume of petro-plastic, they would significantly drive up the price of corn or sugarcane. So a better solution, and the innovation here, is that Micromidas’ bioplastic adds sewage treatment to the enviro-benefits, and leaves corn out of the mix. It just so happens that’s also good for the bottom line.

(Dane Anderson Micromidas Engineer at work)

Here’s how it works, as explained by Smith. They take sewage and feed it to bacteria. “The bacteria store the organics as a bio-polymer … little plastic granules, or inclusions, inside their bodies … they are creating it.” Just like when we eat sugar and, through a series of metabolic processes, turn that into a fat, those little micro-buggers turn sewage into plastic in their bodies.

Then Micromidas uses a proprietary process that "disrupts" the cells and takes the plastic out. After they get it all cleaned up, the end product is a high-value, low-cost plastic resin ready to be sold off, and it biodegrades in under 18 months once disposed of.

Lest you go try this at home, the bacteria are no ordinary bottom-of-your-tub household contagions. Ryan Smith says, “we actually have bug hunters, or ecological microbiologists. They actually go out into nature, they grab a soil sample, a sample of pond water, a sample of waste water” and then through a series of screening mechanisms they pick out just the right microbes that are particularly good at consuming sewage and making bio-plastic.

The company then breeds and combines the best of these and now has a library of 50-60 bacteria with different traits for different kinds of sewage chomping and plastic pooping depending on the needs of the “feed source.” Yes, that’s another way of saying, there is a secret formula of bacteria that eat poop and poop plastic, and it varies depending on the sewage you want to feed them—that’s the business in a nutshell.

Technically speaking, what the bacteria create inside their bodies is a resin powder. Its not a final product by a long shot. Micromidas then has to sell that to a plastics processor. Smith concedes, “we are not currently at a point where we know for certain what application makes the most sense.” Over the past couple months they have developed enough of the plastic resin to send to testing labs to explore options. Possible final products currently being prototyped and tested could be foams, fibers, films, injection molds and lots of other fancy words that mean plastic packaging that doesn’t get anywhere near food. “Something you don’t eat with, but is a packaging material, and ecologically beneficial,” Smith says.

If he can prove his resin does the job, the economics are in his favor. For most plastics, the “feed stock” is about 50 percent of the production cost, whether it's petroleum or bioplastic, but in this case Micromidas actually gets paid to take the sewage off the hands of local processing plants. That’s starting production with a negative unit cost. Not a bad sign for sustainability.

Right now they are still paying for the heavy load of research, testing, and other start-up costs, but Smith says he’s expecting to make his bioplastic at competitive market prices for other disposable plastics when they finalize the formula.

They plan to build out their operation to a commercial scale (right now its prototype scale) within the next six to twelve months he says. Then the money, and the poop will roll in.

Images courtesy of Micromidas.

Hiroaki Umeda

Personal comment:

The grid is the message...

Where do Websites go to Die?

Via dpr-barcelona

In 1998 google was created.

12 years ago there were no blogs.

6 years ago YouTube did not exist, neither Facebook.

Twitter was created 4 years ago and the iPhone was born at the same time.*

In the year 3ϕϕ there will be the Dead Website Archive at the Munižaba cave [Croatia].

Following the same mission of the International Internet Preservation Consortium [IIPC], that is to acquire, preserve and make accessible knowledge and information from the Internet for future generations everywhere, and based in the same kind of philosophy as the project The Ruins of Twitter on the idea that the current times are the age of the data-loss paranoia… what if to have an archive of dead websites?

From David Garcia Studio‘s MAP 003: Archive, we can read:

Hundreds of websites are shut down daily, constantly eliminating traces of our present culture. Although services exist which make random “back ups” of the Internet, they are as robust as the media they are saved on to, and digital media has a frighteningly short lifespan.

According to Iliesiu, our behavior is based on an obsessive back-up system, where we save, we update and upgrade, in a race with crashing computers and obsolete hardware. With this obsesive behaviour and related with an article by E. Alan that we found a few years ago, it is understandable to have the same kind of concerns that Alan had when he wondered what happens to these “dead websites” after their death? And then he added: “Is there an archive where you can trace them? Does anyone keep statistics how many websites are dying daily or monthly? Which country or which category has actually the biggest cementry of websites?” Well, now it seems that we will be able to answer to this questions and say that dead websites will go to the Dead Website Archive in Munižaba.

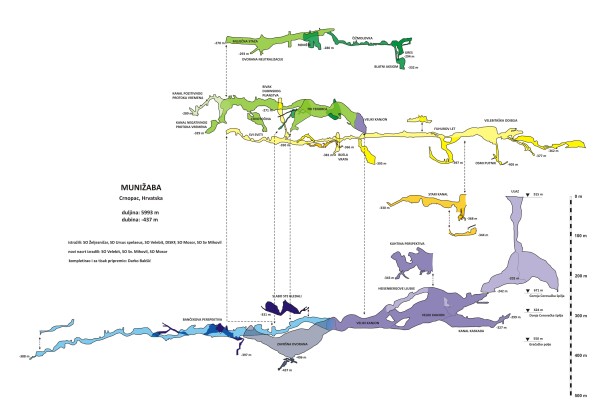

Munižaba cave. Source: Speleologija

Munižaba cave, section. Source: Speleologija

The Dead Website Archive proposed by David Garcia Studio, will convert what was once virtual and plural while in use, to a physical and single reality when it has been removed from the Web. The archive will be located over Europe’s largest cave in Croatia and it’s task is to select the relevant shut-down-websites, and proceed to laser cut the contents of the full site into thin polycarbonate A4 sheets.

This is a response to the call for attention to the urgent need to collect and preserve the world’s cultural and historical record, that is increasingly being produced digitally and in no other form, as the Library of Congress recently published:

It took two centuries for the Library of Congress to acquire its 29 million books and 105 million other items: manuscripts, motion pictures, sound recordings, maps, prints, photographs. Today it takes only 15 minutes for the world to produce an equal amount of information in digital form.

According to Jim Barksdale and Francine Berman, an estimated 44 percent of Web sites that existed in 1998 vanished without a trace within just one year. The average life span of a Web site is only 44 to 75 days. In this context, with websites dying what we can call “a strange death”, we can’t stop asking where did they go?… and start understanding the need to have a dead website archive.

Dead Website Archive at the Munižaba cave by David Garcia Studio

Dead Website Archive at the Munižaba cave by David Garcia Studio

If we agree with the Library of Congress on their definition for “Web Archiving” as the process of collecting documents from the Internet and bringing them under local control for the purpose of preserving the documents in an archive, we should also agree that the archiving process occupies a large amount of space. That’s why choosing the right place for this archive is also an important issue.

According to the Data Centre Knowledge, the ideal location for a Data Centre is one that can accommodate growth and change and is also protected from hazards with an easy access. This kind of locations can be as diverse as urban apartments or underground bunkers and silos; so, the idea to “colonize” the Munižaba cave and build there a bridge that acts as a building, where researchers can stay, work and descend to the cave when acces to the archive is required is quite creative. As David Garcia Studio explains:

In the depth of this natural hollow, the “website sheets” are arranged chronologically, placed directly upon the topography, lit by LEDs and visited as one would a library, or a forest. Down here, websites become unique realities, housed in a single location, guaranteeing a lifespan of hundreds of years; an alternative to the fleeting existence of a hard disk.

The cave allows the user to select and photocopy an archived “web site” from the cave floor, or project it on large screens for group sudy.

Bridge as a building at the Dead Website Archive by David Garcia Studio

Web sites projected on large screens for group sudy at the Dead Website Archive

The Munižaba Cave is located in Crnopac [Croatia]. With an horizontal length of 6947 m and a depth of -437 m it is the perfect place to house the dead website archive, as David Garcia Studio is proposing. The counterpoint between arduous work that is required to move about in such an impressive natural space, and the conrast to the easy access and plural digital reality that defined the website when it was “alive”, is a way to remind us about the ephemeral life of some of our actions when we create and share contents.

Bridge as a building at the Dead Website Archive by David Garcia Studio

Some people think that archives have reached such epidemic proportions that, the digital revolution has not been able to solve the problem, but in fact it has aggravated it. Can we say that the Dead Website Archive will help us to solve this problem?

We’re not sure about the answer… whe can only speculate on the emotion of a future researcher while his eyes are discovering “ancient messages” in foreign languages, hidden in the caves and blurring into subterranean fountainheads:

“Estoy aquí entre archivos y kilos de bits… aquí debajo, ¿no me ves? Aquí…” -@pacogonzalez*

—–

The Dead Website Archive was published on MAP 003 Archive, a project by David Garcia Studio.

* Thanks to @pacogonzalez for the initial facts and the hidden message “I’m here, between archives and tons of bits… down here, don’t you see me? Here…”

Related reading:

- The Ruins of Twitter by Ioana Iliesiu

- Bloggers in the Archive by Geoff Manaugh

- Meeting the Challenge: Saving the World Wide Web at the Library of Congress

Related Links:

Nils Nova

Modification d'espace.

Space modification.

Sources : Booom, Nils Nova

Related Links:

The new North

Via Mammoth

-----

by rholmes

[Murmansk in polar night, photographed by flickr user euno.]

The Wall Street Journal recently ran a fascinating excerpt from geoscientist Laurence Smith’s new book, The World in 2050, which looks at how four global “megatrends” — “human population growth and migration; growing demand for control over such natural resource ’services’ as photosynthesis and bee pollination; globalization; and climate change” — are fueling both international involvement and urban growth in the Arctic:

Much of the planet’s northern quarter of latitude, including the Arctic, is poised to undergo tremendous transformation over the next century. As a booming population increases the demand for the Earth’s natural resources, and as lands closer to the equator face the prospect of rising water demand, droughts and other likely changes, the prominence of northern countries will rise along with their projected milder winters…

[In 2050, this] New North… might be something like America in 1803, just after the Louisiana Purchase from France. It, too, possessed major cities fueled by foreign immigration, with a vast, inhospitable frontier distant from the major urban cores. Its deserts, like Arctic tundra, were harsh, dangerous and ecologically fragile. It, too, had rich resource endowments of metals and hydrocarbons. It, too, was not really an empty frontier but already occupied by indigenous peoples who had been living there for millennia.

Flying over the American West today, one still sees landscapes that are barren and sparsely populated. Its towns and cities are relatively few, scattered across miles of empty desert. Yet its population is growing, its cities like Phoenix and Salt Lake and Las Vegas humming economic forces with cultural and political significance. This is how I imagine the coming human expansion in the New North. We’re not all about to move there, but it will integrate with the rest of the world in some very important ways.

I imagine the high Arctic, in particular, will be rather like Nevada—a landscape nearly empty but with fast-growing towns. Its prime socioeconomic role in the 21st century will not be homestead haven but economic engine, shoveling gas, oil, minerals and fish into the gaping global maw.

Read the full article at the Wall Street Journal.

Personal comment:

Of course, this makes me think of the project we've done last summer, Arctic Opening. The arctic region will certainly be the area where the fate of all "sustainable" approaches will finally be decided... And for my part, I'm not very optimistic about it unfortunately.

If we fail there (a new run for oil, gaz and natural ressources --not to mention for human living spaces-- that will possibly destroy the land), we'll probably fail everywhere else.

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.