Friday, October 08. 2010

Via TFTS

Whilst few (and especially Apple) would refute that HTML5 is the future of the web (Apple, you may recall, see HTML5 as an outright replacement for Abobe’s Flash – not that Adobe are not opening embracing the HTML5 standard themselves) it seems HTML5 is still not ready for full web deployment as the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) have confirmed that they are running into interoperability issues meaning its not yet ‘ready for production’.

“The problem we’re facing right now is there is already a lot of excitement for HTML5, but it’s a little too early to deploy it because we’re running into interoperability issues,” says W3C’s Philippe Le Hegaret. “The real problem is can we make [HTML5] work across browsers and at the moment, that is not the case.”

This standpoint has been further backed up by industry analyst Al Hilwa (IDC) who highlights that, to date, mainstream browsers (not withstanding betas) are still not yet where they need to be for when the new standard hits. “HTML 5 is at various stages of implementation right now through the Web browsers. If you look at the various browsers, most of the aggressive implementations are in the beta versions,” Hilwa observes. “IE9 (Internet Explorer 9), for example, is not expected to go production until close to mid-next year. That is the point when most enterprises will begin to consider adopting this new generation of browsers.”

Interestingly, as an aside, whilst Hegaret sees HTLM5 as a ‘game changer’ and doesn’t doubt that HTLM5 will impact on the use of Abobe’s Flash on websites once the new standard is wholly adopted (HTML5 features integrated support for video and Canvas 2D) he still sees a place for both Flash and other comparable technologies (Microsoft’s Silverlight, for example) whilst Apple’s stance is, as alluded to previously, somewhat more hardline on this issue – if you need insight into Apple’s (in particular Jobs’) stance on the matter you can read more here or you can scroll down to the related posts section for yet more reading on the subject.

“We’re not going to retire Flash anytime soon,” says Hegaret who adds that “”You will see less and less websites using Flash” as HTML5 becomes the standard for website development.

So, quite when can we expect to see HTML5, which initially began development in 2004, hit the open web and become the de facto standard for web development? It seems that we are still looking at the 2 to 3 year timeframe though Hegaret has confirmed that the standard should be ‘feature-complete’ by the middle of next year.

Via SlashGear

Adobe’s cross-platform AIR application system has shown up for download for Android devices, giving developers using the framework a fifth platform on which their code can run. The new release – which can be found in the Android Market – means that AIR apps that run on Mac, Windows, Linux and iOS systems will now also be functional on Android devices.

Apps themselves will be distributed via the Android Market as usual, and as long as the user has the AIR runtime installed they’ll load just like regular apps do. An Android 2.2 Froyo device is required, and the apps themselves need to be formatted to suit a mobile device.

Via Treehugger

-----

by Stephen Messenger, Porto Alegre, Brazil

Like many youngsters, and those young at heart, seven-year-old Max Geissbuhler and his dad dreamed of visiting space -- and armed with just a weather balloon, video camera, and an iPhone, in a way they did just that. The father and son team from Brooklyn managed to send their homemade spacecraft up nearly 19 miles, high into the stratosphere, bringing back perhaps the most impressive amateur space footage ever.

Homemade Spacecraft from Luke Geissbuhler on Vimeo.

The duo housed the video camera, iPhone, and GPS equipment in a specially designed insulated casing, along with some hand-warmers and a note from Max requesting its safe return from whomever may find it after making it back to solid ground. All told, father and son spent eight months preparing for their homemade journey into space, in hopes of filming "the blackness beyond our earth".

Then, one day in August, Max and his father headed out to a nearby park to see their dreams realized. After attaching their equipment to a 19 inch weather balloon and switching on the camera, they watched as their simple craft disappear high into the sky.

After a little over an hour, the craft reached the stratosphere, 100 thousand feet overhead, capturing some incredible footage of space before the balloon popped and fell back towards earth. They found their spacecraft 25 miles away from where they had let it go, stuck up in a tree.

Although the camera's battery died some minutes before touching-down, the footage it returned is no short of impressive. And despite the fact that the craft didn't technically reach the boundaries of space, Max and his father are undoubtedly proud of their accomplishment.

Geissbuhler describes the experience on the video he uploaded to the Internet:

In August 2010, we set out to send a camera to space. The mission was to attach a HD video camera to a weather balloon and send it up into the upper stratosphere to film the blackness beyond our earth. Eventually, the balloon will grow from lack of atmospheric pressure, burst, and begin to fall.

It would have to survive 100 mph winds, temperatures of 60 degrees below zero, speeds of over 150 mph, and the high risk of a water landing. To retrieve the craft, it would need to deploy a parachute, descend through the clouds and transmit a GPS coordinate to a cell phone tower. Then we have to find it.

Needless to say, there are a lot of variables to overcome.

Just as the space-race of the 1960s was driven by a spirit of exploration and ingenuity, so too was the bold idea of Max and Luke Geissbuhler to film the darkness beyond our planet with their homemade spacecraft. And just as mankind was at once emboldened by the success of science and the realm of possibility was widened for an entire generation -- perhaps this father and son team can inspire others to follow their dreams, too, do-it-yourself style.

-

More on Fantastic Flights

Amazing Photo of Earth Taken With Point-n-Shoot Camera and Balloon

Student Makes History with First Ever Human-Powered Ornithopter

World's First Flight Powered by 100% Algae Biofuels Completed

-----

by rholmes

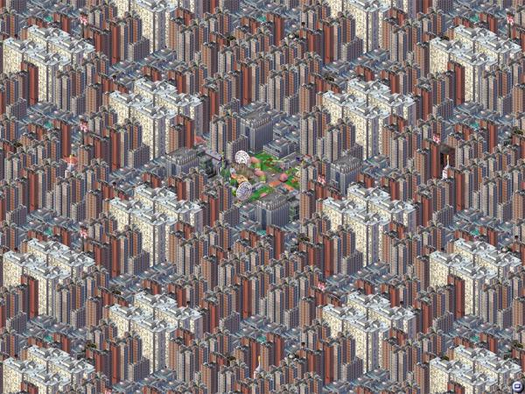

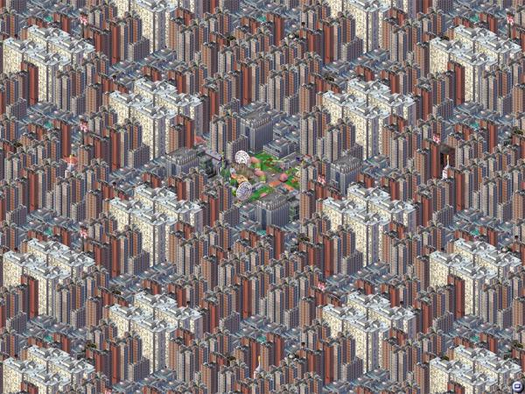

[Screenshot from "Magnasanti"]

Vincent Ocasla’s “Magnasanti” is a SimCity with six million inhabitants, which Ocasla argues represents the maximum possible stable population achievable within the game. A winning solution, he says, to a game without any programmed conditions for winning. Ocasla, a Filipino architecture student, spent four years constructing the SimCity — building the SimCity itself, but also studying the game systems, wading through equations, and working out optimal spatial solutions on graph paper. I was reminded of Magnasanti by Super Colossal’s post on it today, which you should read:

This is the kind of archiporn that I am a sucker for; gamespace urbanism exploited to its extreme condition. Can you ‘win’ urbanism? Is this even urbanism? If not, can we take anything from its construction? The primary move that the city makes is to remove cars altogether and base transport purely on subways. I suspect this is a method to exploit the space otherwise taken up by roads for real estate allowing for an increased population per tile, however, it is a strategy that many cities—Sydney included—are seriously looking into. Remove motor vehicles, increase public transport. Seems like a sound idea. But ultimately, Magnasanti has little to do with urban design and everything to do with gaming systems for maximum reward.

This, of course, is exactly right — the construction strategy for Magnasanti tells us very little about how to construct a city, but a great deal about how to manipulate the internal logic of SimCity (and that is instructive as to the distance between the logic of the city and the logic of SimCity, which results from SimCity being the embodiment of a particular set of assumptions about how cities are planned). Having been reminded, though, I should also link to this interview with Ocasla at Vice. Fascinatingly, Ocasla argues that he constructed Magnasanti as a critique of urban conditions, inspired by Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi. Magnasanti, he says, is not a blueprint for how to build a city. It’s an intentionally hellish vision which exploits the game’s internal logic as commentary:

There are a lot of other problems in the city hidden under the illusion of order and greatness: Suffocating air pollution, high unemployment, no fire stations, schools, or hospitals, a regimented lifestyle – this is the price that these sims pay for living in the city with the highest population. It’s a sick and twisted goal to strive towards. The ironic thing about it is the sims in Magnasanti tolerate it. They don’t rebel, or cause revolutions and social chaos. No one considers challenging the system by physical means since a hyper-efficient police state keeps them in line. They have all been successfully dumbed down, sickened with poor health, enslaved and mind-controlled just enough to keep this system going for thousands of years. 50,000 years to be exact. They are all imprisoned in space and time.

Given mammoth’s professed interest in finding overlap between gameworlds and cities, it’s probably not surprising that this leads me to wonder: what other games might be used to produce critiques of cities, or buildings, or landscapes? I’m particularly interested in this question because of a minor pet theory, which is that one of the most important futures for video games — if they are to become as important a venue for cultural expression as they have the potential to be — is less about the design of spectacularly complex linear (or even branching) narratives for video games, and more about the sharing, re-telling, discussion, and celebration of emergent narratives and objects created by players. Pro Vericelli or Oil Furnace, in other words, not Mass Effect.

A little while ago I spat out a series of tweets for “#idiosyncraticallyarchitecturalvideogames”, some of which (Love, Detonate, Mirror’s Edge) would seem to be excellent fodder for this sort of thing. If, for instance, as Geoff Manaugh has argued, “the bank heist and the prison break together might form the architectural scenario par excellance“, then surely a game like Subversion — “a Mission Impossible-style spy thriller” set within an infinite array of procedurally-generated cities, neighborhoods, buildings, and bank vaults — could be played with the intent of exploring such scenarios (and, if the player is particularly clever, played with the intent of expressing a certain set architectural ideas). What happens, basically, when architects play video games as architects?

[Thanks to Tim Maly for the tip on Subversion.]

Personal comment:

This is extreme "Plan voisin"!

|