Thursday, April 30. 2009

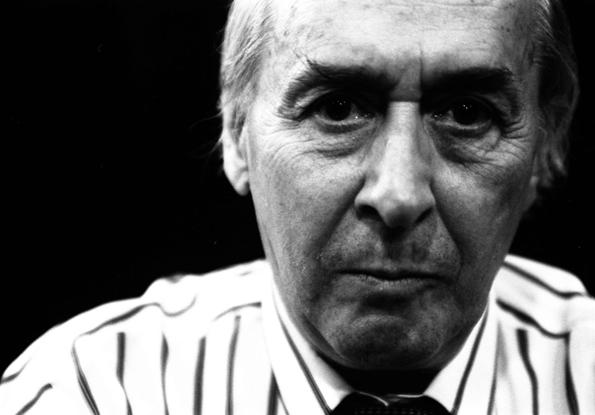

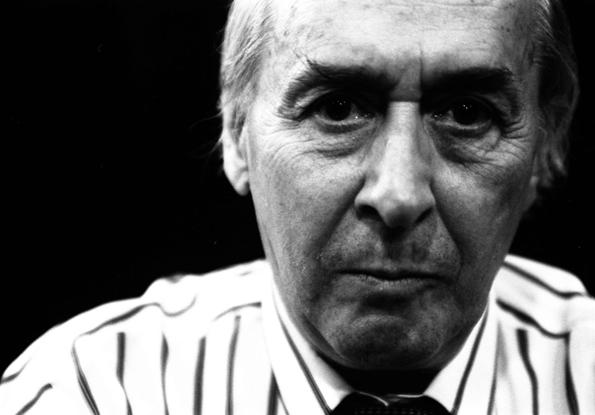

A homage to J G Ballard, the writer who saw terror and poetry in the city landscape

I am glad I didn’t ask to interview JG Ballard at his home in Shepperton in 2003, and instead chose to meet him at the Hilton hotel on Holland Park Avenue, West London - ironically a far more Ballardian building than his own home. “We could be anywhere!” he said to me, approvingly.

Very few writers’ names coin an adjective, but Ballard’s has. ‘Ballardian’ has come to refer to ‘dystopian modernity, bleak manmade landscapes and the psychological effects of technological, social or environmental developments’, according to the Collins English Dictionary. His fiction has always taken inspiration from the built environment - particularly the utopian dream of modernist architecture - and he was especially interested in the latent content of buildings, what they represented psychologically (or “does the angle between two walls have a happy ending?” as he once obliquely put it), and was an original and brilliant architecture critic in his own right. He was the only writer, for example, to notice that before 9/11 no one had considered the World Trade Centre to be a symbolic target at all - indeed, he noted, that was the whole point, it was a meaningless act and it was this that people found so unsettling.

I first met Ballard in 1997 at a Soho press screening for David Cronenberg’s Crash at which, slightly unnervingly, he sat directly behind me. The novel that the film was based on, along with its precursor The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), is perhaps the most outre of his work, exploring the sexuality of the car crash and its psychotic protagonist Vaughan’s desire to drive off a motorway flyover and collide with Elizabeth Taylor’s car.

The handful of occasions I spoke to him since then were exhilarating autopsies of a whole host of subjects, including multi-storey car parks (‘One of the most mysterious buildings ever built. What effect does using these buildings have on us? Are the real myths of this century being written in terms of these huge unnoticed structures?’), and his favourite building in London, Michael Manser’s Heathrow Hilton (1992) (‘Sitting in its atrium one becomes a more advanced kind of human being. One feels no emotions and could never fall in love.’). When talking to him, I recalled Will Self’s observation that ‘Ballard rolls the phrases around in his mouth as if they were ironic boiled sweets’.

His disaster novels of the 1960s - The Wind From Nowhere (1961), The Drowned World (1962), The Burning World (1964) and The Crystal World (1966)- revelled in their environmental cataclysms, which now seem eerily prescient. It was in the early 1970s with the novels Concrete Island (1974), High Rise (1975) and Crash (1973) that Ballard became the ‘poet of the motorways’, in which his protagonists embrace their hostile surroundings. In Concrete Island, Ballard maroons ‘wealthy architect’ Robert Maitland - Crusoe-like - in a triangular interzone of a motorway intersection. Maitland decides to stay there rather than go back to his former life.

Ballard once famously said that ‘the future is going to be boring’ and that the whole world is ‘turning into a suburb of Dusseldorf’.

Ballard once famously said that ‘the future is going to be boring’ and that the whole world is ‘turning into a suburb of Dusseldorf’. In his later fiction, he turned to dissecting the infinite leisure that is awaiting us all, which he first wrote about in Vermilion Sands (1971) about an imaginary holiday resort. In Cocaine Nights (1996), Super-Cannes (2000) and Millennium People (2003), Ballard looked at gated communities and the nerve tonic of violence that was needed to shock his characters out of consumer capitalism. Ballard told me that whereas the 20th century was mediated through the car, the 21st century would be mediated through the home.

For Ballard, psychology and space were intertwined. His terrifying short story The Concentration City (1967) concerns a physics student, Franz, who tries to escape a seemingly illimitable city but who after 10 days of travelling realises he has arrived back to the same place and on the same day. Billennium is another superb short story about the psychological effects of overcrowding in which two young men discover a secret, larger-than-average room next to their own cubicle in a vast city. As they enjoy the extra personal space that they have never known, they allow their friends to share the space, which eventually ends up the same size as the room they were trying to escape from in the first place …

In a brilliant essay for The Guardian in 2006 in which he wrote about the blockhouses of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall on Utah beach, Ballard lamented the death of the utopian project of the ‘heroic period of modernism from 1920 to 1939’ – ‘We see its demise in 1960s kitchens and bathrooms, white-tiled laboratories that are above all clean and aseptic, as if human beings were some kind of disease. We see its death in motorways and autobahns, stone dreams that will never awake, and in the Turbine Hall at that middle-class disco, Tate Modern - a vast totalitarian space that Albert Speer would have admired, so authoritarian that it overwhelms any work of art inside it.’

Reading back my notes from an interview from 2003, I see how prescient he was about the speculative housing boom – ‘It’s our South Sea Bubble’ he told me (see online). Also, I see that we spoke about the inevitability of a terrorist attack in London. With Ballard gone, so is our early warning system.

-----

Via The Architect's Journal

Personal comment:

Intéressant article publié par The Arhitect's Journal à propos de l'intérêt que J.-G. Ballard portait à l'architecture et en quoi celle-ci était centrale à sa pensée. Bien entendu, pas uniquement l'architecture, mais aussi la technologie, les sciences, la critique sociale, la psychologie et le dystopisme constituaient les ingrédients principaux de sa littérature.

Tuesday, April 28. 2009

By Joe Fletcher on April 27th, 2009

Over the last few years, social computing has been relegated to asynchronous websites like FaceBook and Twitter, where users connect with many people and their collective information is harvested for the larger group. However these are still largely individually actions, not synchronous… yet we call it “social”. I would like to expand that definition.

Think of a computer where you sit down and work simultaneously with your friend. Imagine you and your friends all playing a game or solving a problem at the same time on the same computer. This has been one of the key aspects of our vision at Microsoft Surface. As I’ve presented over the last year on Surface, I’ve talked a lot about the aspects of social computing. Initially when I started on the team I was skeptical of social computing as Surface defines it: multiple people working around a single computer. Since that time, I have seen some of the great innovations and situations that Surface style social computing allows. With its vision system (instead of capacitive or infra-red), Surface can recognize 52 simultaneous points of touch, as well as physical objects, making it a computer for a truly social environment.

Social computing is described as the intersection between social behavior and computing systems, and often in somewhat ambiguous computational terms. I question how much of what happens on social sites like FaceBook [et al] is really social (I don’t often come to work sharing a list of 25 personal oddities about myself). The only real social aspect is that you’re sharing items with other people in an easy way across geographic divides. Although the web seems like a macrocosm of that definition. I’m not sure why things like instant messaging are not considered social computing, but they are more social than most sites bearing that label.

I would like to implore readers to expand their definition of the term social computing and realize it can apply to many more situations than it currently is; those being actual social situations. I would describe that as what Surface is aspiring to be, the first true social computer. It provides context and use for multiple people, on all sides. Although true social computing can be done with a single computer and two or more people, it may not be optimal. Below are a few of the ways I’ve come to think about social computer usage:

- Driver as a presenter: this happens when you’re showing someone a YouTube video

- Driver (w/ an influencer or back seat driver): this happens when you’re searching the internet for someone and someone is telling you what do type in

- Turn taking: passing a laptop back and forth to share information

- Simultaneous: both playing a game on Microsoft Surface. I’ll call this synchronous social activities. Very different from the three above it

Of course none of what I describe here is the current way we define social computing, which is why I’m asking people to expand their thinking. Perhaps there is another word to describe these situations? Whatever happens, it’s become clear to me that the computer cannot simply stay as the personal device it has been and designers should begin to think about social proximity activities and behaviors. As technology becomes more pervasive and cultures become more acquiesced to computers, there will be a need and desire to continue and expand the social aspects.

As an aside, while I bring up Surface several times in my posts, please don’t take that for blindly selling the technology. I am very aware of its flaws and issues, and part of my opportunity at Microsoft is to make those better. For those interested, here is my talk from MIX09 on Surface and touch computing where I discuss both my love and discomforts on those topics.

-----

Via Johnny Holland Magazine

Personal comment:

Je trouve intéressant, à un moment ou tout le monde fonce dans le tas du buzz "social computing", de questionner ce terme. Ici, le point intéressant est qu'on signale le caractère asynchrone de Facebook et Twitter (bien que Facebook prétende vouloir aller vers le temps réel avec le flux de chaque "Wall" --mais je ne serai pas étonné d'apprendre qu'ils sont en réalité revenu en arrière car cela s'avère assez indigeste et s'approche du spam--). Il y a quelques années, tout le monde ne jurait que par le "synchrone" et les "réseaux sociaux" étaient plutôt appelés des "multi-users" (chat, réalité virtuelle partagée, IM, jeux partagés, etc.). Il fallait du "temps réel", de l'interaction entre personnes et en direct.

Une fois la folie des réseaux sociaux passées, je ne serai pas étonné de voir resurgir le "temps réel" et peut-être que l'avenir des réseaux sociaux sera alors dans une hybridation synchrone-asynchrone, avec capacité de parfaitement "tuner" cette question des flux et du rapport au "temps réel" ou au "temps différé".

Monday, April 27. 2009

Today we're pleased to share an exciting new project that taps into the power of YouTube and Google Maps to spread the word about the state of our planet. Luc Besson's and Yann-Arthus Betrand's 90 minute full-length film "Home" will exclusively be available online on YouTube for English, French, Spanish and German–speaking countries beginning June 5 — just in time for the 37th World Environment Day.

Through stunning displays of aerial camerawork, the film will give people from all corners of the world a glimpse of our planet like never before and visually demonstrate the urgency for preservation efforts. In addition to its Internet premiere, "Home" will be shown in movie theaters and outdoors on big screens at key locations around the globe. It will also air on TV stations around the world. Using this unique distribution model, one with a massive online and offline effort, the film creators are able to reach the widest audience possible. So whether you'd prefer to head to the theaters, watch it under the stars, or just stay put on the couch — the way you view "Home" is up to you.

And starting today, YouTube channels in English, French, Spanish and German will feature behind-the-scenes looks from the making of the film, as well as interviews, and extras. To add even more dimension, Google Maps is featuring specially created layers that shed more light on some of the material covered in the movie. You can also use Maps to find a theater location near you.

To get a preview of what you can expect on June 5, check out some of the spectacular footage in the Home YouTube channel, like the video below of the Arctic world and its wild terrain that's essential to preserve. Or this one of Los Angeles exclusively seen from the sky, giving us a new perspective of the cityscape at night. And please respond and react to the film via video responses, comments, and ratings and share links via email with your friends.

Posted by Mats Carduner, Head of Google France and Southern Europe

-----

Via The Official Google Blog

Personal comment:

Exclusivité Youtube - Google (maps) pour la "world première" d'un film (sur le climat). Pas question de télévision, de festival de cinéma ou autre ici ... Uniquement une distribution massive, mondiale et gratuite (sponsorisée - "googlisée" -) par le web.

Mimi Ito, Daisuke Okabe, and Ken Anderson have an interesting chapter in the edited volume by Rich Ling & Scott Campbell (2009) “The reconstruction of space and time: mobile communication practices” which recently came out. The chapter is called “Portable Objects in Three Global Cities: The Personalization of Urban Places”. The authors explore how people use portable objects to ‘interface’ with urban space and locations. Up to now, the authors say, the dominant focus has been on conceptualizing the mobile phone as a personal communications technology. The emphasis in such studies has been on how interpersonal communication has been made possible “anytime, anyplace, anywhere”. To a much lesser extend the mobile phone has been conceptualized as a device that is tied to local situations. In this approach the mobile phone is seen as an interface to urban space. Mobile communication infrastructure intersects with the physical infrastructure of the city [1].

Ito et al do not look at the mobile phone on its own. Instead, they take the phone as but one of the portable objects that are ‘interfaces’ to the city. These include media players, books, keys, credit and transit cards, identity and member cards. Together these comprise “the information-based ‘mobile kits’ of contemporary urbanites” (p. 67). So the mobile phone, instead of being studied in isolation, is part of a larger assembly of objects that people use to navigate the city, as well as to sustain social relations with other people [2]. Next they discuss three kinds of urban interfacing, which they have labelled cocooning, camping, and footprinting. Cocooning is the practise of people shielding themselves off in public settings. For instance by using portable media players, books, doing stuff on their mobile phones, etc. They create an invisible bubble of mobile private space around them. Camping is the practise of finding a nice spot in town - often in coffeehouses - and doing information related work there with laptops, mobile phones, etc. This can be both for work and private affairs (and often intermingle). Camping can co-exist with cocooning when people shield themselves off from physical social interactions through portable media objects. Footprinting describes the various customer transaction and loyalty schemes through which people leave traces in a particular location. It is “the process of integrating an individual’s trajectory into the transactional history of a particular establishment, and customer cards are the mediating devices” (p. 79). The authors have done fieldwork research in three big cities: Tokyo, Los Angeles, and London. Interestingly, they conclude that behaviors vary only slightly between these cities.

I find this approach very interesting for a number of reasons. First, the conceptualization as ‘urban interfaces’ focusses on the locative qualities of mobile media. The paper gives a nice categorization of the various ways in which mobile media act as interfaces between ‘the digital’ and ‘the physical’. Second, the mobile phone is not studied in isolation but as part of a larger array of informational objects that people carry along with them to manage and deal with urban life. Consequently, the image of the mobile phone shifts from an intrusive addition to an imagined once upon a time of ‘real’ public space, face to face interactions, spontaneous encounters and serendipitous discovery, etc., to a more pragmatic view on the mobile as an everyday necessity of urbanites. Third, Ito et al connect changes in the urban experience to changes in displaying identity in public spaces. This point receives scant attention in the chapter but is very important indeed.

I also have some points of critique on this conceptualization and approach. First, Ito et al predominantly focus on the interaction of people with the physical localities and infrastructure of the city (p 71-72). They take infrastructure as a collection of ‘dead’ objects (roads, public transport entry ports, toll roads, etc.) making urban life possible. Location in their view refers solely to a point in Euclidian space, a coordinate on the map so to say. The authors leave out the human aspect of location and infrastructure. In their own words “it becomes even more crucial that mobile communications research look at these more infrastructural and impersonal forms of social and cultural practise” (p. 72 - my emphasis). Yet locations and infrastructures are only abstracted ‘ideal’ or ‘categorical’ concepts of their phenomenological equivalents in lived space. They are the abstract counterparts of places and routes (or trajectories). I would say we should look at the human side of infrastructures as crossroads of experiences, in the vein of what geographer Doreen Massey has called the “throwntogetherness” of place as an event [3]. Of course many locative media projects exactly tried to visualize this human aspect of infrastructures and locations (e.g. Christian Nold’s biomapping).

A second critique on this approach is that it considers only one side of the hybrid relation between physical space and digitally mediated space. This conceptual framework gives prevalence to physical space over digital space. The main focus is on how the digital ’seeps’ into the physical and alters pre-existing situations there. But how does the physical seep into the digital realm? It is one-way, departing from the assumption of what Lev Manovich has called “augmented space” as an overlay of physical space [4]. This suggests that digital space is an extra layer to reality. As De Souza e Silva has argued, this idea of augmented space gives prevalence to behavior in the physical realm, rather than the interactions that take place in both types of spaces at the same time [5]. Instead, she argues, we must look at digitally mediated social behavior as taking place in ‘hybrid space’ [5].

Thirdly, important other location-based uses of portable information objects are being left out, such as navigation and wayfinding in (unknown) cities. The focus seems restricted to urban practises by people who actually inhabit or at least regularly frequent the city. In addition, footprinting is depicted as taking place solely in the commercial realm through customer loyalty cards. There is an abundance of locative media project that use geotagging as a way of leaving digital footprints or graffiti in the city (e.g. Dutch project Bliin). And the mobile device itself increasingly becomes the interface to footprinting. Many new high-end devices have automatic geotagging built in their photo camera, and come with various uploading services. Some devices already have NFC technology for micro-payments. It seems logical that more and more portable informational objects will converge into the mobile device. Will it ever come to the point that The Mobile City becomes “the city in our mobile”?

[1] It should be noted that in most writings on ‘locative’ aspects of mobile media there is an almost exclusive focus on the city as the locus of action. This is understandable since in the city many of the networks that make up present-day ‘hybrid space’ are present in much greater density, and arguably with much greater consequences. In what ways rural space is changing under the influence of mobile media is understudied, I guess, and probably just as important. Especially if we consider that according to Claude Fisher (1992) who studied early fixed line telephony certainly in the beginning the telephone has been more important for rural living than for urban living.

[2] A similar point about the research bias towards studying single technologies is made by Julsrud & Bakke in chapter 7 of this same volume (p. 160).

[3] Massey, D. B. (2005). For space. London; Thousand Oaks: SAGE. p. 140.

[4] Manovich, L. (2005). The Poetics of Augmented Space: Learning from Prada. 1-15. Retrieved from http://www.manovich.net/TEXTS_07.HTM

[5] De Souza e Silva, A. (2006). From Cyber to Hybrid: Mobile Technologies as Interfaces of Hybrid Spaces. Space and culture, 9(3), 261-278. Retrieved from http://www.lib.ncsu.edu/resolver/1840.2/80

-----

Via The Mobile City

Personal comment:

Un livre à la thématique pas vraiment surprenante, mais qui va dans le sens des concepts que nous utilisons tels que "relations spatiales médiatisées", "spatialités médiatisées", etc.

A version of the Turing Test now running in Second Life could one day prove that humanity is truly intelligent

Monday, April 27, 2009

Various versions of the Turing test have been put forward over the years but only one is so tough that even humans haven't yet passed it. That will change if Florentin Neumann at the University of Paderborn in Germany and a couple of pals have their way.

This alternate exam is called the Hofstadter-Turing Test, after Douglas Hofstadter who put forward a version of the idea in an essay called Coffee House Conversation in 1982. Here's how it works (pay attention because it contains a certain circularity to the argument):

An entity passes the Hofstadter-Turing Test if it first creates a virtual reality, then creates a computer program within that reality which must finally recognise itself as an entity within this virtual environment by passing the Hofstadter-Turing Test.

Spot the tricky circularity to this test? Players can only pass if they create a virtual intelligence which must then pass the test itself. And since that hasn't been achieved by any human in history, nobody has yet passed.

What's interesting about the paper though, is that Neumann and co claim that humanity is moving closer to achieving a pass. First of all, we're half way there because we've already built various virtual worlds. And now Neumann and co claim to have implemented a version of the Hofstadter-Turing Test in the Second Life virtual world.

"We have succeeded in implementing within Second Life the following virtual scenario: a keyboard, a projector, and a display screen. An avatar may use the keyboard to start and play a variant of game classic Pac-Man, i.e. control its movements via arrow keys."

They go on to say:

"With some generosity, this may be considered as 2.5 levels of the Hofstadter-Turing Test:

1st: The human user installs Second Life on his computer and sets up an avatar.

2nd: The avatar implements the game of Pac-Man within Second Life.

3rd: Ghosts run through the mace on the virtual screen.

Observe that the ghosts indeed contain some (although admittedly very limited)

form of intelligence represented by a simple strategy to pursue Pacman."

They're absolutely right that taking this on board requires a remarkable amount of generosity: the Ghosts in a Pacman game are unlikely to ever put in a decent challenge in any other type of Turing Test.

But suppose we give them the generosity they desire. The process raises some interesting ways of analysing the various levels of reality that could occur when machines become intelligent. And what of the possibility that our efforts may be validating the intelligence of a programmer exactly one level higher than us?

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/0904.3612: Variations of the Turing Test in the Age of Internet and Virtual Reality

-----

Via MIT Technology Review

Personal comment:

Où l'on reparle du Test de Turing et 2nd Life... Raisonnement un peu étriqué, mais qui n'est pas sans rappeler par certains aspects le côté absurde d'Electroscape 004 (AI vs AI in self space).

|