Wednesday, February 19. 2014

Via Frieze

-----

Fourteen30 Contemporary, Portland

In his video California Bloodlines (GPS Dozen) (all works 2013), California artist Jesse Sugarmann drives through a bright desert expanse in search of somewhere elusive. The camera is trained on the car’s dashboard and windshield, which are festooned with 12 GPS devices that relegate the dramatic landscape of sand and scrub, distant mountains and azure sky to a removed presence. As he drives, a chorus of robotic voices talk over one another, blurting out contradictory directions (‘Turn left!’, ‘Turn right!’, ‘Re-calculating!’). Sugarmann’s intended destination is California City, from which the artist’s exhibition at Fourteen30 Contemporary took its name: a place real enough to have assigned geo-positioning coordinates, yet not real enough for the dozen devices to reach consensus.

Geographically, California City is the third-largest city in the Golden State. Its 40- square-mile grid in the Mojave Desert was developed in the 1960s in tandem with the California Aqueduct, which would transform the arid terrain into a lush, cosmopolitan oasis, a two-hour drive north of Los Angeles. But when the aqueduct was rerouted to the west, development was abandoned. In the ensuing half-century, a population of 15,000 made California City home, leaving the unfinished infrastructure of sidewalks and roads to be slowly reclaimed by the desert. Today, the outskirts of this unrealized city play host to Air Force weapons testing and off-road motor sports.

Symbolically, the site evidences a kind of regional amnesia, in which the glitz and glamour of Southern California’s main cultural centre allows this also-ran destination to fade from collective memory. But Sugarmann leverages its metaphoric impact for more personal ends, using California City as a stage to contemplate his mother’s worsening Alzheimer’s. This place, which bears the fundamental shape of a city but conspicuously lacks the city itself, becomes an analogue for his mother’s frustrated attempts to recall and organize a past she knows exists, but can’t seem to access.

In a second video, California Bloodlines (Parts 1 and 2), the artist has arrived in California City, or at least one of its desolate cul-de-sacs. Joined by an assistant, Sugarmann performs a series of actions addressing the site’s past, present and the irreconcilable divide between them. Initially, they appear as stewards, attempting to restore the road to working condition. They patch a makeshift bonfire pit left by an off-road after-party, sweep sand off the weather-beaten pavement (as desert winds violently undo their efforts), and spread a new layer of asphalt. But with the appearance of a sand dragster, a vehicle equally at home on sand or tarmac, the site’s present-day activities creep in, creating a confused connection to its past: the duo spreads asphalt on the exterior of the dragster and sets it ablaze.

In California Bloodlines (Parts 1 and 2), Sugarmann interpolates scenes of his own ‘weapons testing’ in California City, drawing square-mile development tracts onto Perspex in liquid napalm and burning them into the surface. These works were displayed in the gallery like production stills or outtakes from the film, each image executed in thick black burn marks and feathery yellow flickers. It’s not hard to connect the geometric patterns of the tract with the mapping of the human brain in neuro-imaging techniques.

Sugarmann’s previous body of work focused almost exclusively on cars – as figurative bodies, ‘vehicles’ for projecting human desire and as ubiquitous monuments to the fact of obsolescence and mortality. With the California City videos, this connection between subjects and their automotive stand-ins is made more powerful by the artist’s equation of the landscape with memory. Here, the internal stage of mental function – or in the case of his mother, dysfunction – is depicted in physical, spatial terms. And, tragically, in the enacted folly of restoring unused roads, he illustrates how that which is forgotten can never be recovered.

John Motley

Monday, February 17. 2014

Via BLDGBLOG

-----

[Image: Photo by Danny Lane].

Earlier this winter, I missed an opportunity to travel over to Switzerland with architects Smout Allen and Kyle Buchanan who, at the time, were leading their students around the mountain landscapes of the Alps in order to learn about infrastructures of defense and national snow-production, among other things. It sounded like an amazing trip.

[Image: Photo by Kyle Buchanan].

However, I did get to see some photos sent back of the various and random things they visited in the resort city of Zermatt.

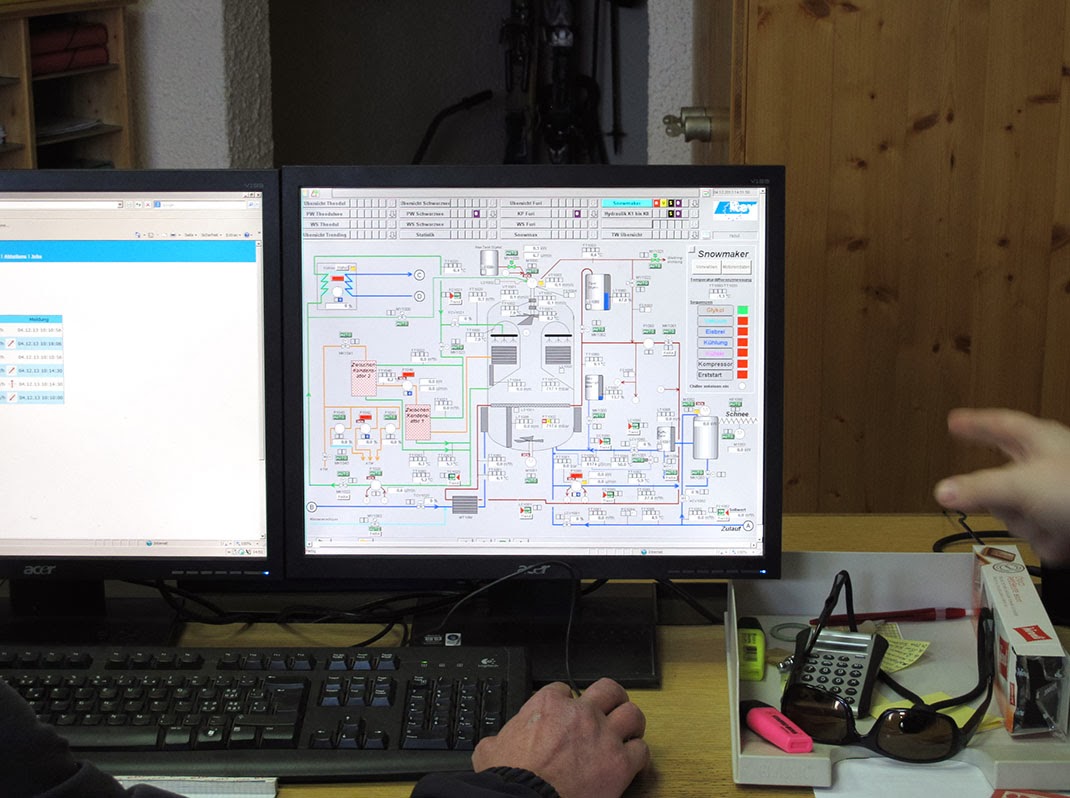

This included a huge machine known as The Snowmaker. Apparently originating in Israel, it was formerly used to cool South African diamond mines but since repurposed for spraying artificial snow onto ski slopes in the Alps.

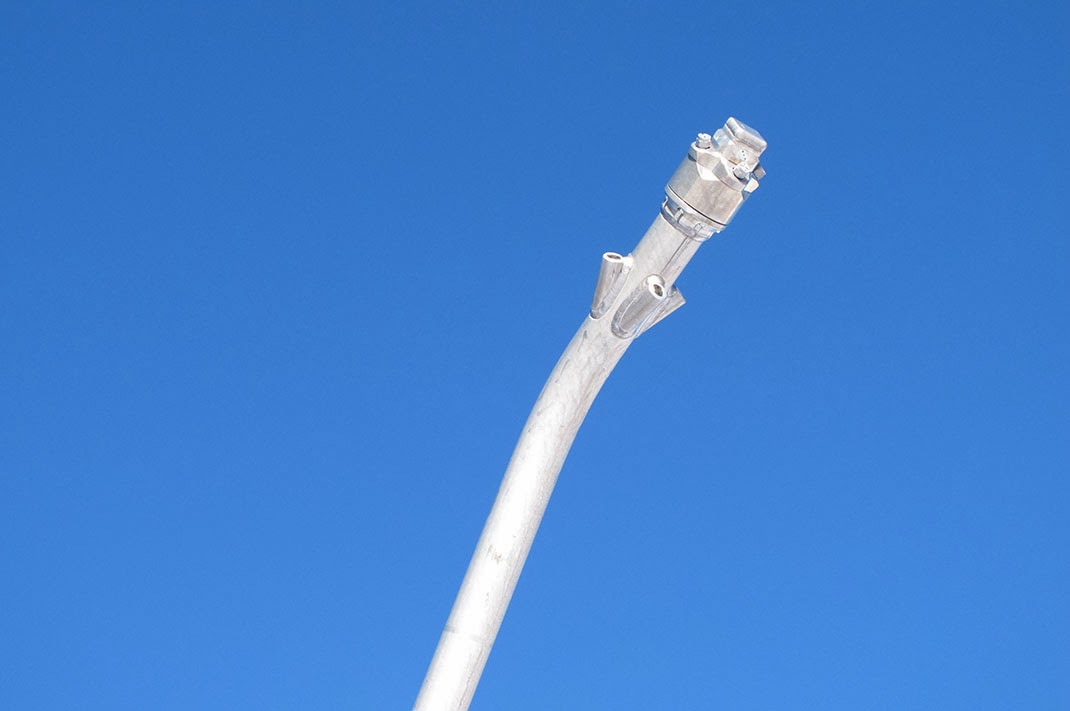

[Images: Photos by Kyle Buchanan].

The carefully choreographed operation requires a fan-like array of buried water pipes, pipes that spread throughout the resort like capillaries.

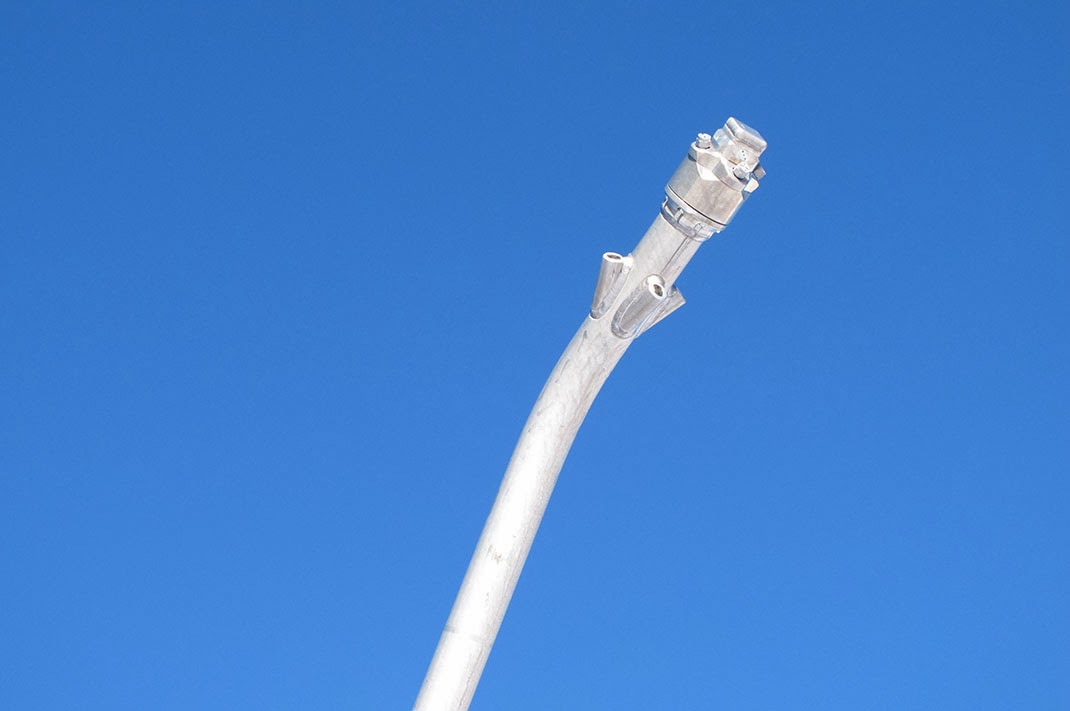

Snow—or what passes for it—then sprays out of thin, reed-like valves called "lances"—

[Image: Photo by Kyle Buchanan].

—resulting in other-worldly piles of fresh white powder, perfectly sculpted domes that later require selective placement elsewhere.

[Images: Photos by Danny Lane].

The shaping of the mountain landscape—so easily mistaken for nature—exhibits obvious features of artificiality, including careful lines and striated grooves resulting from deposition, sculpting, and maintenance.

[Image: Photo by Danny Lane].

The machine is literally an oversized air-conditioning unit, waiting to be put to use by landscape-printing crews whose work is mistaken for winter. It so efficiently—though inadvertently—produced ice while cooling diamond mines in Africa that it has since been put to use 3D-printing popular tourist landscapes into existence, like something out of Dr. Seuss.

To at least some extent, The Snowmaker—and newer technology like it—has replaced older, fan-based snow machines. These thus now sit in a maintenance shed, like antique airplane engines, both derelict and obsolete.

[Image: Photo by Danny Lane].

This is all just part of the dramaturgical stagecraft of Switzerland: winter becomes a precisely choreographed thermal event that just happens to take on spatial characteristics amenable to downhill skiing.

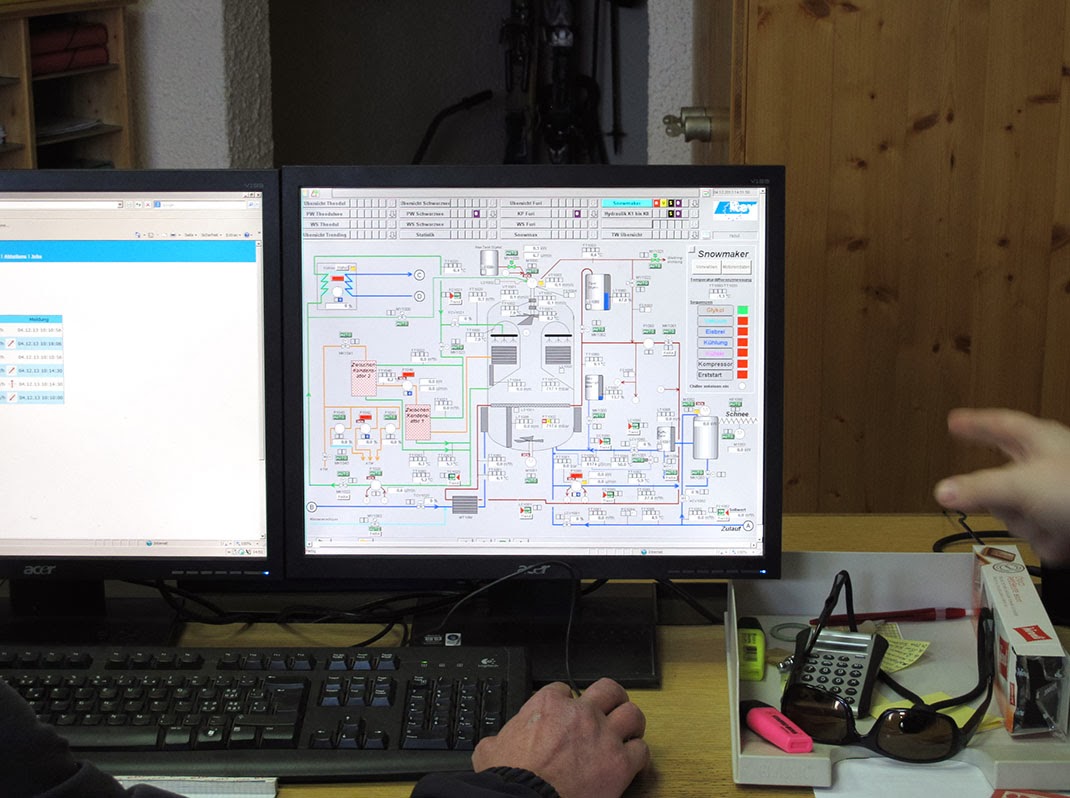

In any case, there are nearly 1,000 individual snow-production machines in Zermatt, only one of which is The Snowmaker. The whole system is controlled from a central computer, apparently operated by one wizard-like figure who is really just a stoned twentysomething in a wool hat, turning different parameters on and off and spraying whole new European landscapes into existence outside.

[Images: (top) Photo by Danny Lane; (bottom) photo by Kyle Buchanan].

It's like the Sorcerer's Apprentice at the top of the world, 3D-printing recreational mountainscapes. The landscape is a computer he alone knows how to use.

Imagine if Thomas Mann's Magic Mountain had taken place amidst a massive, artificially maintained and 3D-printed winter, and you might begin to grasp the unearthly strangeness here, the surreal mechanical goings-on at great altitude.

What appears, at first glance, to be a simple ski holiday actually turns out, upon later inspection, to be a landscape-scale encounter with artificiality and snow-based 3D-printing.

(See also Gizmodo, where these photographs were first published; thanks to Mara Kanthak for her help with translation in Switzerland).

Wednesday, February 12. 2014

While browsing around on the Internet, I found the remnants of this exhibition that took place in Yamaguchi Center for the Arts and Media in Tokyo back in 2010. To my big ignorance, I didn't know the work of Fujiko Nakaya dating back from the 1970ies. Now I do and I can see how far Blur, Diller & Scofidio's famous building (during Expo.01 in Switzerland back in 2001), was pushing Nakaya's ideas one step further/bigger.

Via Yamaguchi Center for the Arts & Media

-----

Artistic environmental spheres formed by fog, light and sound

Large-scale project unveiled simultaneously in three public spaces in and around YCAM

The upcoming CLOUD FOREST exhibition at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM] presents examples of newly discovered environmental creation, realized with an "artistic environments" themed fusion of artistic expression and information technology. Currently on show in three different public spaces in and around YCAM will be a large-scale collaborative project featuring "fog sculptures" by Fujiko Nakaya, an artist whose works have gained much attention at various occasions in Japan and overseas, along with the original light and sound art of Shiro Takatani.

These commissioned installations conceived in-residence at YCAM combine artificial fog, sunlight and sound, orchestrating with the help of originally developed devices and responding to changing weather conditions a variety of impressive sceneries. Visitors can experience transformations in their perception as they interact with artworks incorporating information technology while walking in the fog in the patios or surrounding park. While introducing and reevaluating foresighted art and science projects originally presented at the EXPO'70 Osaka, which eventually inspired this new project, the exhibition anticipates the future of environmental creation, "informational spheres" of tomorrow, and possible creative quests through art.

Related events

Opening events

Demonstrative Performance

August 7 (sat) 19:00 - 20:00

Venue: Foyer, Patios Admission free

Artists: Fujiko Nakaya, Shiro Takatani, softpad (Takuya Minami, Tomohiro Ueshiba, Hiroshi Toyama) In addition to Fujiko Nakaya and Shiro Takatani, the members of Kyoto-based art/design collective softpad, who took charge of the sound design for this exhibition, participate in a special experimental live performance incorporating the fog, light and sound installations in the patios and foyer.

Artist Talk

August 8 (san) 14:00-16:00

Venue: Studio B Admission free

Guests: Fujiko Nakaya, Shiro Takatani Moderator: Akira Asada

Artists involved in this exhibition appear as special guests in a casual talk session that gives them the opportunity to introduce their works. Moderator will be Akira Asada, a specialist in the field who is familiar with each artist's endeavors to date. While referring to the work of E.A.T. at the 1970 Osaka Expo's Pepsi Pavilion, which inspired this project in the first place, the artists will look back at such trailblazing achievements as Nakaya's "fog sculptures" and David Tudor's soundscapes originally presented at the Expo, and discuss the developments and prospects now, four decades later.

* There will be guided gallery tours offered during the period of the exhibition. Please check the exhibition website for more information on additional event.

Cloud Forest

Prospects of art-inspired new environmental creation

Rather than addressing "environmental" issues only from an ecological point of view, this "artistic environmental spheres" themed exhibition focuses on the mutual relationships between natural, social, mental and informational environments. Aiming to provide a stage for such diverse aspects of the subject matter to function as interfaces for each other, CLOUD FOREST pursues a contemporary form of environmental creation triggered off by transformations in human perception. The shifting perceptual experience of interacting with artworks incorporating information technology and YCAM's architectural characteristics makes the visitor aware of spatial transfigurations, and ultimately commands ideas related to "environments" of the future.

Fujiko Nakaya "Fog Sculpture #47773" Pepsi Pavilion Commissioned by Experiments in Art and Technology (EXPO' 70, Osaka, Japan 1970). Photo: ©Takeyoshi Tanuma

Environment as an art form

This exhibition is based on a definition of "environment" as a compound of mutually generative, penetrative and reflective areas. While there have been various movements in the past that proposed environments as stages for or components of art, such as land art or earth art, this exhibition aims to explore the creative aspects of media art for possible new forms of "environments". Think of it as an attempt to generate with the help of information technology open environments embracing multiple interlinked, mutually "environmental spheres". In this day and age, the concept of "environments" manifested through spatial transformations is surely going to write its own quiet yet forceful story.

40 years after the EXPO'70 Osaka: E.A.T. reinterpreted from a contemporary point of view

E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) attracted worldwide attention when the American experimental collective presented their work in the Pepsi Pavilion at the EXPO'70 Osaka. At this huge international event, the group of collaborating artists and scientists presented the astonishing results of their pioneering exploration of the relationship between environment and art, driven by the participating artists' innovative ideas. Considering the 40 years between then and the present day as a fundamental period of transition from the material productivity-based viewpoints of progressive science to invisible information capitalism, this exhibition attempts a critical review of the ideas and accomplishments of E.A.T. By interpreting such forward-thinking approaches of art and science with an eye on contemporary information society and perspectives of environmental creation, we aim to disclose a contemporary form of reality and its new environmental components.

"Island Eye Island Ear" Project by Experiments in Art & Technology (Knavelskar Island, Sweden 1974). Photo: Fujiko Nakaya

Environments emerging out of human perception and networking technology

This exhibition couples the "fog sculptures" of Fujiko Nakaya with the creative ideas of the late David Tudor, who was in charge of interactive sound when Nakaya's works were first introduced at the EXPO'70 Osaka's Pepsi Pavilion. The "fog sculptures" take on a variety of appearances at the main venues in and around YCAM, shown alongside a new installation piece incorporating Tudor's original concept of soundscapes based on environmental reverberation. Altogether, the displays can be considered as a collaborative attempt of new environmental creation, undertaken by Fujiko Nakaya together with the YCAM staff and such post-Expo generation artists as Shiro Takatani. These works utilizing information technology to incorporate in various ways transformations of both natural surroundings and human perception communicate a sensory idea of critical, totally new "spheres of artistic environments".

Fujiko Nakaya "GREENLAND GLACIAL MORAINE GARDEN" (Nakaya Ukichiro Museum of Snow and Ice,Kaga City, Japan 1994). Photo: Rokuro Yoshida

Cloud Forest

The exhibition's title, "CLOUD FOREST" is borrowed from the name of a subtropical forestal area that is characterized by a frequent formation of mist about the canopy level. It is a place that can be considered as a peculiar zone of active interpenetration right in the middle between wild nature and the realm of human society.

At the same time, the title is a reference to David Tudor's sound installation/performance piece "Rainforest". Approaching the laws of nature by means of cutting-edge technology, this exhibition pays deep homage also to the innovativeness of the "Island Eye Island Ear" project that Fujiko Nakaya conceived with Jacqueline Monnier back in the 1970s.

Environmental spheres in three installations

Patios... Interfaces of fog, light and sound

The entirely glass-walled patios - high open spaces that allow wind, rain and sunlight to fall in - are intermediate places combining/connecting the outside (natural environment) with the inside (artificial environment). This exhibition includes large-scale installations involving artificial fog, light (reflected sunlight) and sound, which transform the Center's two patios into interfaces between two different types of environments.

Influenced by the surrounding interior and exterior environments, the artificial fog that is emitted in varying intervals from multiple directions forms convections of various modes and configurations. In addition, a special mirror device is used to redirect sunbeams into the fog. As optical effects will vary significantly according to the fog's configuration, meteorological conditions, and the position of the sun, the displays will continue to take on different appearances depending on the time, position and angle. As locations, sizes, and positions of installed apparatus are different in both patios, visitors can appreciate two completely different installations. Furthermore, special sound systems installed inside the exhibition spaces allows visitors to perceive the soundscapes locally while walking.

"Cloud Forest" [Patio] (YCAM 2010)

"Cloud Forest" [Central Park] (YCAM 2010)

Also on display are photographs and video footage of previous works related to this exhibition (Fujiko Nakaya & David Tudor, EXPO'70 Osaka "Pepsi Pavilion", etc.)

Friday, January 31. 2014

With some delay...

Via Mammoth

-----

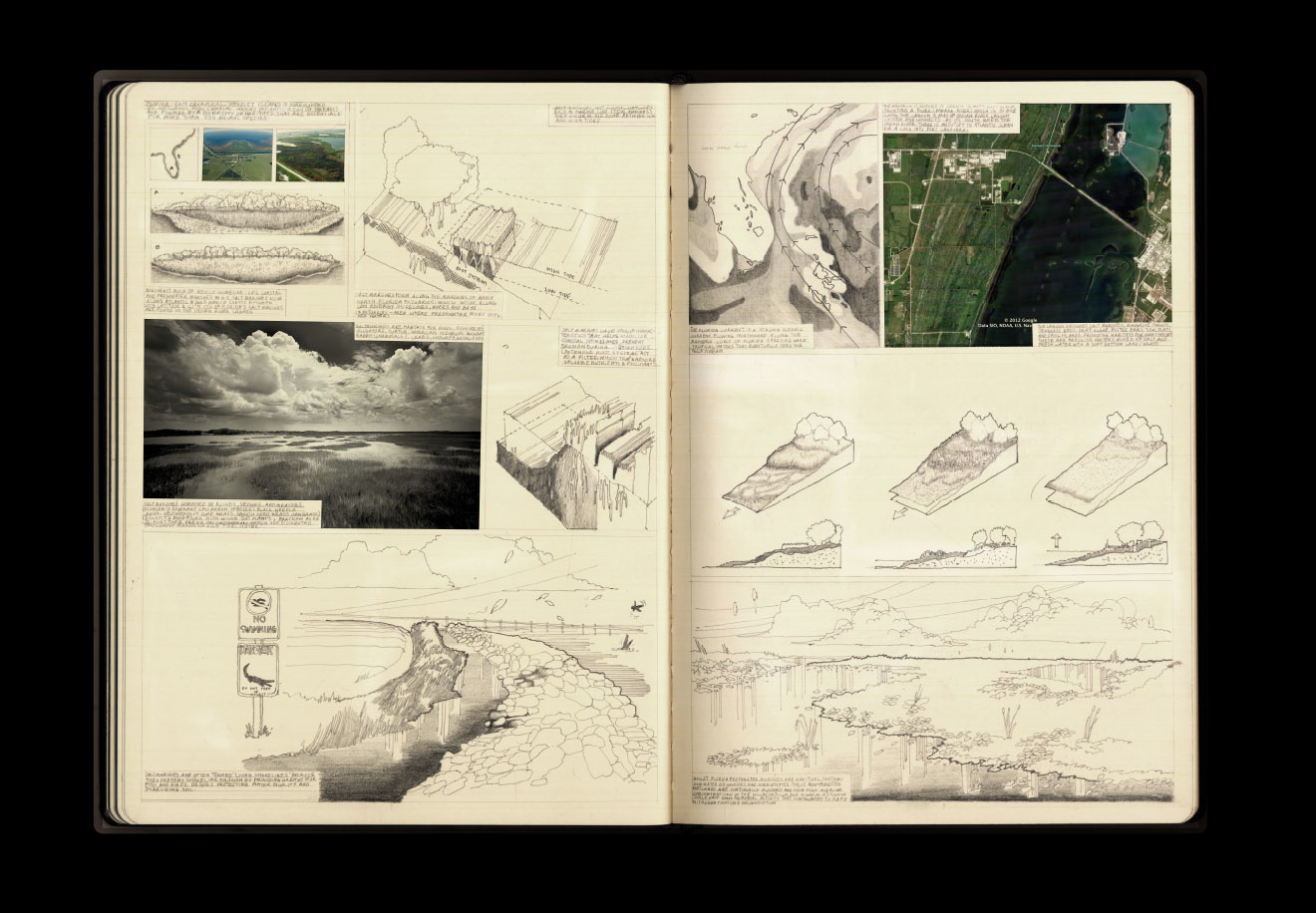

[The Audubon Society's micro-dredger, the John James, making new land in the Paul J. Rainey Wildlife Sanctuary in South Louisiana. Karen Westphal, Audubon’s Atchafalaya Basin program manager, will be speaking about this participatory micro-dredging project at DredgeFest Louisiana's symposium, which is this Saturday and Sunday at Loyola University in New Orleans.]

Tim Maly and I explain why we’re holding DredgeFest in Louisiana this coming weekend (and following week) for Gizmodo:

…south Louisiana is disappearing—terrifyingly fast. Sea-level rise, salt water intrusion, and canal excavation for industrial purposes have all combined with the constrainment of the river via flood control infrastructures to radically alter the balance between deposition, subsidence, and erosion. Instead of growing, the delta is now shrinking. Louisiana has lost over 1700 square miles of land (an area greater than the state of Rhode Island) since 1930. Without a change in course, it is anticipated to double that loss in the next fifty years. By 2100, subsidence, erosion, and sea level rise are projected to combine to leave New Orleans little more than an island fortress, effectively isolated in the rising Gulf of Mexico.

Moreover, even where the land itself may not be entirely submerged, the loss of barrier islands and coastal marshes exposes human settlements ever more precariously to the vicious effects of hurricanes and tropical storms, including the destructive waves known as storm surge.

This situation is entirely untenable. You thought Katrina was a terrible disaster? (It was.) Imagine what happens to New Orleans when a Category 6 hurricane hits in 2086, when even the highest ground in the French Quarter and the Garden District is barely above sea level and well below the ever-thickening barriers the Army Corps will throw up to protect America’s newest island.

In response to this apocalyptic but plausible threat, Louisiana is engaging in the world’s first large-scale experiment in restoration sedimentology. With the aid of components of the federal government like the Army Corps of Engineers and a bounty of funds earmarked for coastal restoration and protection as a result of payments owed by BP for the damages wrought by the 2010 Deep Horizon oil disaster, Louisiana has accelerated its nascent crash-program in experimental land-making machines, rapidly prototyping a wide array of weird and wonderful techno-infrastructural strategies for building land. This is an effort to cobble together a synthetic analog to the land-making machine that the Mississippi once was. If you want to understand the future of coastlines and deltas in a world of rising seas and surging storms, you should pay close attention to what is happening in Louisiana.

Read the full piece at Gizmodo. (And, if you’re able, come to DredgeFest Louisiana!)

Wednesday, January 15. 2014

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

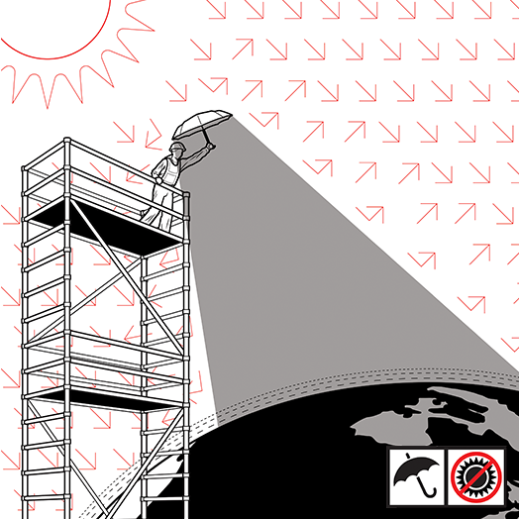

Illustration by McKibillo

More than a decade ago, Paul Crutzen, who won the 1995 Nobel Prize in chemistry for his research on the destruction of stratospheric ozone, popularized the term “Anthropocene” for Earth’s current geologic state. One of the more radical extensions of his idea—that human activity now dominates the planet’s forests, oceans, freshwater networks, and ecosystems—is the controversial concept of geoengineering, deliberately tinkering with the climate to counteract global warming. The logic is straightforward: if humans control the fate of natural systems, shouldn’t we use our technology to help save them from the risks of climate change, given that there’s little hope of cutting emissions enough to stop the warming trend?

In recent years a number of scientists—including Crutzen himself in 2006—have called for preliminary research into geoengineering techniques such as using sulfur particles to reflect some of the sun’s light back into space. With the publication of A Case for Climate Engineering, David Keith, a Harvard physicist and energy policy expert, goes one step further. He lays out arguments—albeit hedged with caveats—for actually deploying geoengineering. He says that releasing sun-blocking aerosol particles in the stratosphere (see “A Cheap and Easy Plan to Stop Global Warming,” March/April 2013) “is doable in the narrow technocratic sense.”

Indeed, Keith is steadfastly confident about the technical details. He says a program to cool the planet with sulfate aerosols—solar geoengineering—could probably begin by 2020, using a small fleet of planes flying regular aerosol-spraying missions at high altitudes. Since sunlight drives precipitation, could reducing it lead to droughts? Not if geoengineering was used sparingly, he concludes.

Australian ethicist Clive Hamilton calls the book “chilling” in its technocratic confidence. But Keith and Hamilton do agree on one thing: solar geoengineering could be a major geopolitical issue in the 21st century, akin to nuclear weapons during the 20th—and the politics could, if anything, be even trickier and less predictable. The reason is that compared with acquiring nuclear weapons, the technology is relatively easy to deploy. “Almost any nation could afford to alter the Earth’s climate,” Keith writes. That fact, he says, “may accelerate the shifting balance of global power, raising security concerns that could, in the worst case, lead to war.”

Thing reviewed

A Case for Climate Engineering

David Keith MIT Press, 2013

The potential sources of conflict are myriad. Who will control Earth’s thermostat? What if one country blames geoengineering for famine-inducing droughts or devastating hurricanes? No treaties ban climate engineering explicitly. And it’s not clear how such a treaty would operate.

Keith professes ambivalence about whether humans are truly able to wield such powerful technology wisely. Yet he feels that the more information scientists uncover about the risks of geoengineering, the lower the chances the technology will be used recklessly. Though his book leaves unanswered many of the questions that arise over how to govern geoengineering, a policy paper that he published in Science last year goes further to address them: he and a coauthor proposed government authority over research and a moratorium on large-scale geoengineering but said there should be no treaties regulating small-scale experiments.

Hamilton says this approach would lead nations on a path toward the conflict that he thinks would inevitably surround geoengineering. Allowing lightly regulated small experiments, he suggests, could undermine the urgency of political efforts toward cutting emissions. This, in turn, increases the possibility that geoengineering will be used, since failing to restrain emissions will leave temperatures rising. Hamilton accuses Keith of seeking a “naïve … cocoon of scientific neutrality” and says researchers cannot “absolve themselves of responsibility for how their schemes might be used or misused in the future.”

That may be true, but Keith deserves credit for directing attention to ideas he knows are dangerous. Accepting the concept of the Anthropocene means accepting that humans have the responsibility to find technological fixes for disasters they have created. But little progress has been made toward a process for rationally supervising such activity on a global scale. We need a more open discussion about a seemingly outlandish but real geopolitical risk: war over climate engineering.

Personal comment:

"Who will control Earth’s thermostat?" Oh well, following yesterday's news, I would suggest Google, they have "smart" technology ...

By the way, will we also reach some "climate neutrality quash" one day (compared to "net neutrality quashed" by a federal court), once global weather will definitely be an artifact and a product?

Friday, January 10. 2014

By fabric | ch

-----

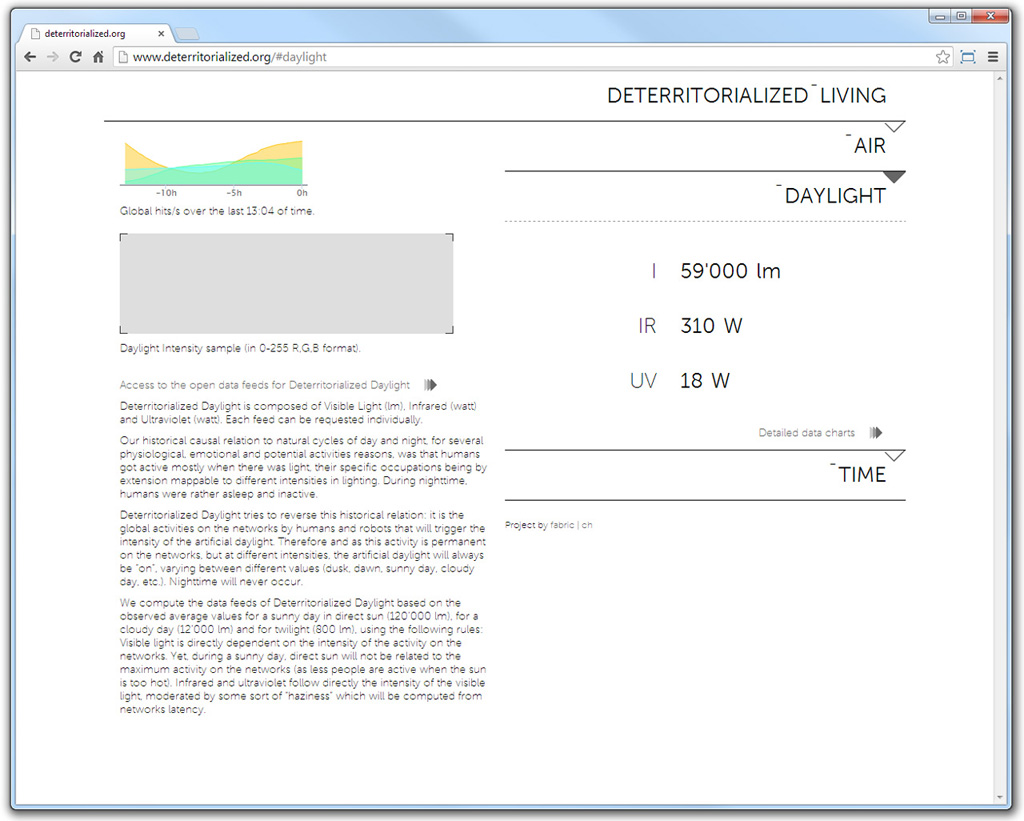

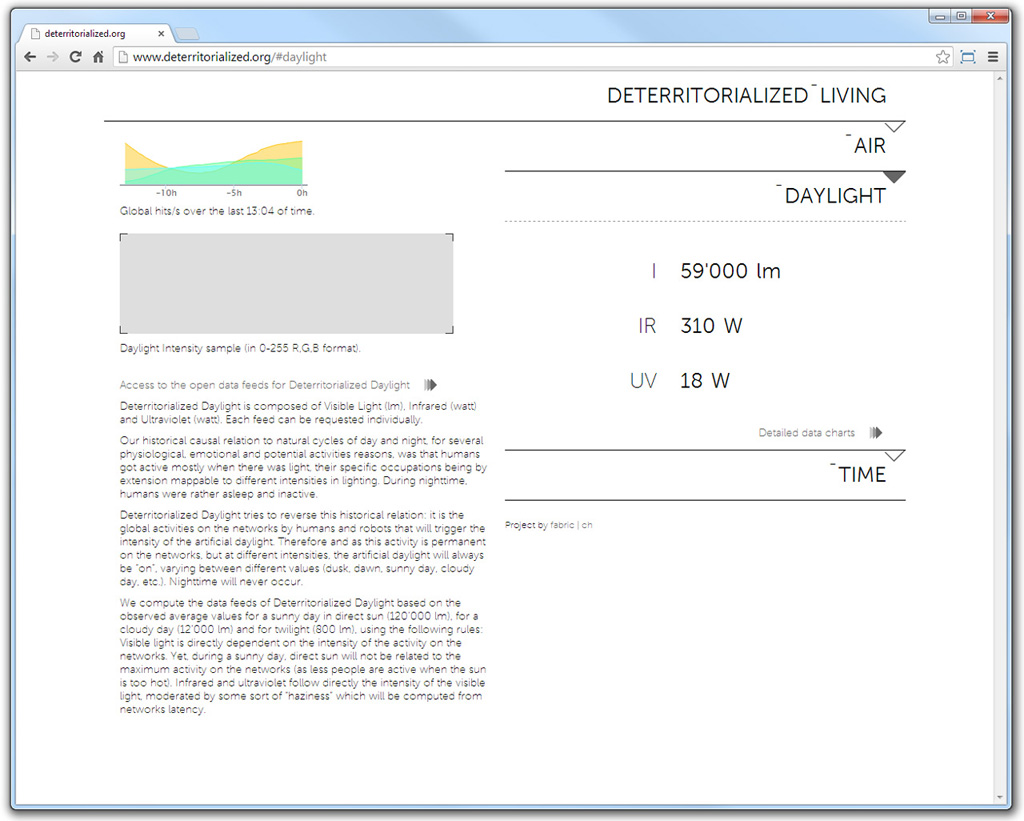

After its creation for Close, Closer, the Lisbon Architecture Triennale last summer, we had the opportunity to exhibit Deterritorialized Living for the first time in November 13 during Acces(s) Festival in Pau (curated by Ewenn Chardronnet), at the Maison de l'Architecture.

The project, which consists in an "artificial troposphere" that reverses our causal relationship to the rythms of day and night, air, seasons, time -- based on real time global network activity by both humans and robots and that is delivered in the form of open data feeds, fictional data in some ways -- was displayed accompanied by videos of former projects by fabric | ch.

Specifically, we took the ocasion to complete an electromagnetic sample of Deterritorialized Daylight, based on its feed of data.

The simple spatialization took the appearance of two strong controllable projectors and two light reflectors. These were the only sources of light in the exhibition space, accompanied by five screens that displayed the different data feeds and the interactive version of Deterritorialized Daylight (a controllable intensity of the 13 last hours). Two small but intense "suns", an "eclipse" and a "waning moon" seemed to appear in the space, at the same time.

The variable intensity of the light in the space defined a pattern of illumination within the exhibition room where the display tables took place, in an apparent random manner, yet following this pattern accordingly to their own reflection potential and their exhibition program.

Exhibition after exhibition, we plan to develop physical samples of the data feeds and materialize the "geoengineered" troposphere. We will also look into some architectural explorations of this "geoengineered" climate, architectural environments that will locate themselves within, or just use this deterritorialized atmosphere.

Tuesday, October 29. 2013

Via Treehhugger

-----

The possible applications for drones are growing every day. From watching out for poachers in wildlife parks in Africa to delivering textbooks to students, the autonomous flying machines are tackling problems both big and small. The ability for the drones to have onboard sensors and HD cameras makes them ideal tools for mapping and surveillance.

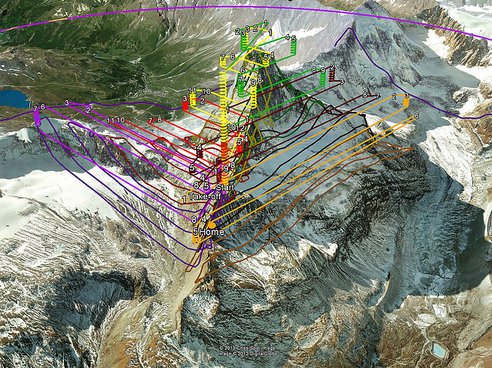

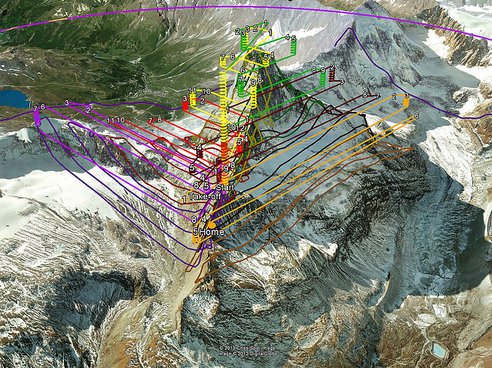

Taking that idea to the extreme, engineers from senseFly, partnered with Drone Adventures, Pix4D and Mapbox, were able to create a digital model of the Matterhorn with a 20-cm resolution in three dimensions. Two teams took the company's eBee drones to the mountain with Team 1 hiking to the summit and launching the devices to fly around the top of the peak. Team 2 launched eBees from the bottom of the mountain to cover the lower parts of the mountain.

© senseFly

SenseFly says, "The main challenges successfully overcome were to demonstrate the mapping capabilities of minidrones at a very high altitude and in mountainous terrain where 3D flight planning is essential, all the while coping with the turbulences typically encountered in mountainous environments."

For the project, 11 flights were made totaling 340 minutes. The drones took 2,188 photos and created an HD point-cloud with 3 million datapoints. The company's eMotion2 software provided the ground control for the flights, automatically creating flight paths for the multiple drones.

© senseFly

You can watch a video about the project below and see how the mapping and flight planning took place.

Friday, September 27. 2013

Via The Funambulist

-----

My regular readers would have understood that I develop a certain amount of quasi-pathological obsessions for a certain amounts of ideas or concepts that tend to come back regularly in my articles, in such a way that one could say that each article tends towards an attempt to articulate always the same idea. Among these obsessions is the idea of the archipelago and you will soon see that I did not finish to articulate a few thoughts around this idea yet, since an ambitious project of the same name will soon complement my writing on this blog.

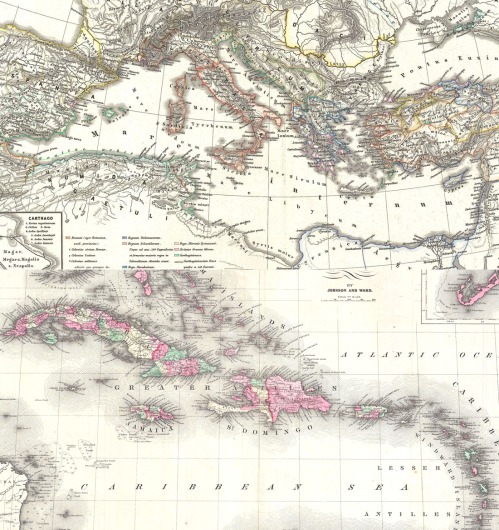

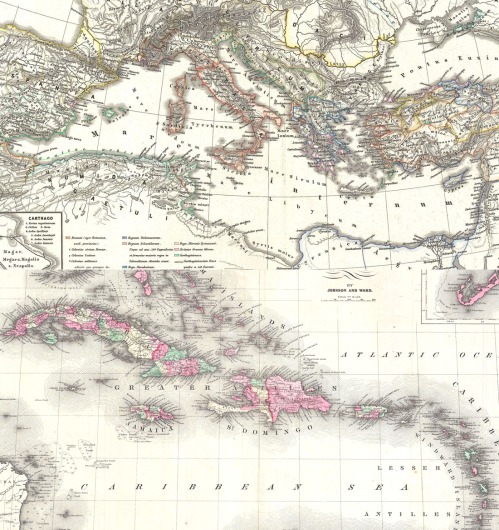

In the following text, I would like to approach the archipelago through the same way that I first did, through a philosopher that has been highly influential to me in this last decade, Édouard Glissant. The archipelago is for him a figure of a utopia towards which the world should tend in order to construct a politics of “the relation” rather than a politics of the universal. Of course, an archipelago is a very evocative example of territories that construct simultaneously the difference between each island, and a collective identity as a group; that is what makes it a strong figure for a new paradigm of sovereignty (see past article). However, according to Glissant, there is an additional complexity to it that enriches this territory of an exemplary ideology. In order to look at it more closely, we need to first observe its opposite, the continental sea — etymologically, the archipelago is also a sea before being a group of islands. The paradigmatic example of the continental sea, because of both its history and its contemporaneity is the Mediterranean Sea. The following excerpt is what he writes about it in one of his only translated books in English, about which we might want to observe the difficulty to translate the language — Glissant was talking about translation as an emerging art in itself — that Betsy Wings brilliantly managed to translate from French to English:

Compared to the Mediterranean, which is an inner sea surrounded by lands, a sea that concentrates (in Greek, Hebrew, and Latin antiquity and later in the emergence of Islam, imposing the thought of the One), the Caribbean is, in contrast, a sea that explodes the scattered lands into an arc. A sea that diffracts. Without necessarily inferring any advantage whatsoever to their situation, the reality of archipelagos in the Caribbean or the Pacific provides a natural illustration of the thought of Relation. (Édouard Glissant, The Poetics of Relation, trans Betsy Wing, Ann Harbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997)

When one looks at maps of the history of the Mediterranean Sea, whether dominated by the Greeks, the Romans, the Christians, the Muslims, the Ottomans, or the European colons (French, British and Italians), one can easily understand the consistence of the efforts that have been deployed for centuries to force the multiple into the uniform. In this regard, the Mediterranean itself a sort of virtually neutral territory that each nation, one by one, attempts to dominate in order to bring one’s identity to the rank of universal norm. The fact that the three largest monotheist religions — two of which are still the most populated in the world — emerged and developed around the Mediterranean, is symptomatic for Glissant of this obsessive will to unify. The geography of the region is, of course, not alone to blame, but one understands that in the case of the Mediterranean Sea, the territory of water constitutes a certain object of covetousness for the nations that surround it.

The Caribbean, as an archipelago constitutes, on the contrary, a layout of islands for which the water is the environing milieu; there is therefore no desire to dominate it since it has virtually no limits, and thus does not constitute a territory per se. History has not been ‘tender’ with these islands as they were the first territories discovered in the late 15th-century by Christopher Columbus who enslaved the indigenous population. Starting in the beginning of the 18th-century, during the colonial domination of the Spanish, the French and the British, hundreds of thousands of African slaves were brought by boat — the vessel of colonial uniformization for Glissant — and provided the manpower of the colonies until the first part of the 19th-century when slavery was progressively abolished. In the meantime, in 1791, Toussaint L’Ouverture and the slaves of Saint-Domingue won a historical war against the French colons and created an autonomous territory on what is now Haiti. The current blockade on Cuba from the United States is also revealing the various tensions that are still operative around this special territory.

Nonetheless, the Caribbean is also the territory of a concept that Glissant work his all life around, the one of creolization. Creole itself often refers to one of the local languages spoken in the Caribbean as something that emerged from the encounter of the colonial language (mostly Spanish and French) and the various languages spoken by the slave population. In general, creole can refer to a similar linguistic evolutionary process between any number of languages (colonial/colonized or not), and even at a broader level, the phenomenon of creolization, as understood by Glissant, constitutes a process in which any aspect of an individual or collective identity encounters another to create a new one, richer because integrating the difference, if not opposition, from which it is born. The jazz is one of the mot evocative example of such a process, as it was invented in the American plantations by slaves after their encounters with European music instruments. This music cannot possibly be considered without the resistive struggle that its birth constituted, since any act of freedom — creativity being at the paroxysm of it — accomplished by the slave materializes by definition a negation of his or her status.

The archipelago is the territory of creolization par excellence, as it embodies a geography of islands whose coast are in continuous contact with the unexpected — another important component of Glissant’s philosophy/poetry — of the otherness. The processes of exchanges — pacific or violent — that occur on it are a form of recognition of the difference with the otherness, that then construct voluntarily or not new aspects of individual and collective identities that are richer than a simple synthesis of the two original ones. In this regard, Glissant’s philosophy of the Relation can be understood as the social interpretation of Baruch Spinoza’s philosophy of affects that I have been evoking many times in the past. Just like Spinoza, Glissant starts by analyzing the world in a ‘neutral’ way, unfolding the nature of exchanges between humans and nations, and only then establishes an ethics based on this philosophical scheme. For Glissant, the archipelago constitutes the territory of his ethics.

For more in English about the philosophy and history of the Caribbean, consult the excellent Public Archive edited and written by Professor Peter Hudson.

Wednesday, September 18. 2013

Via BLDGBLOG

-----

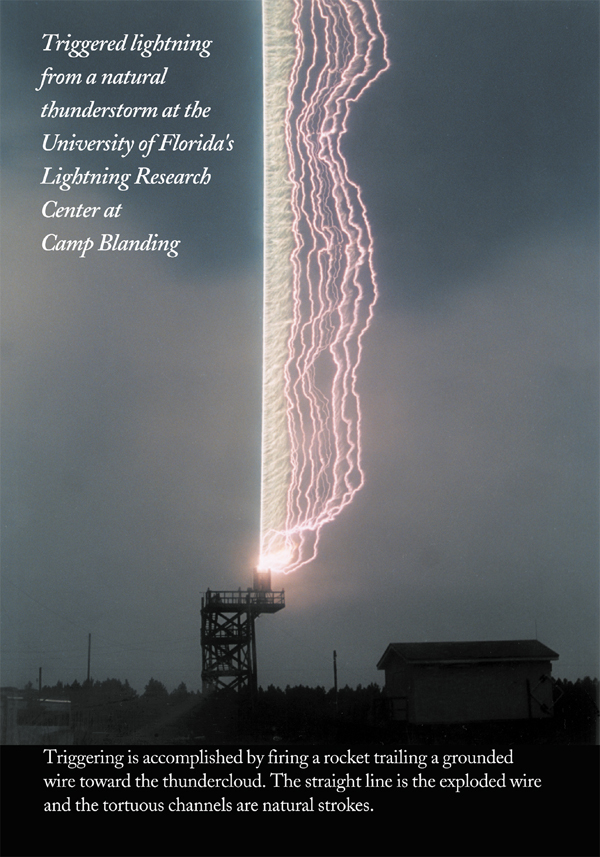

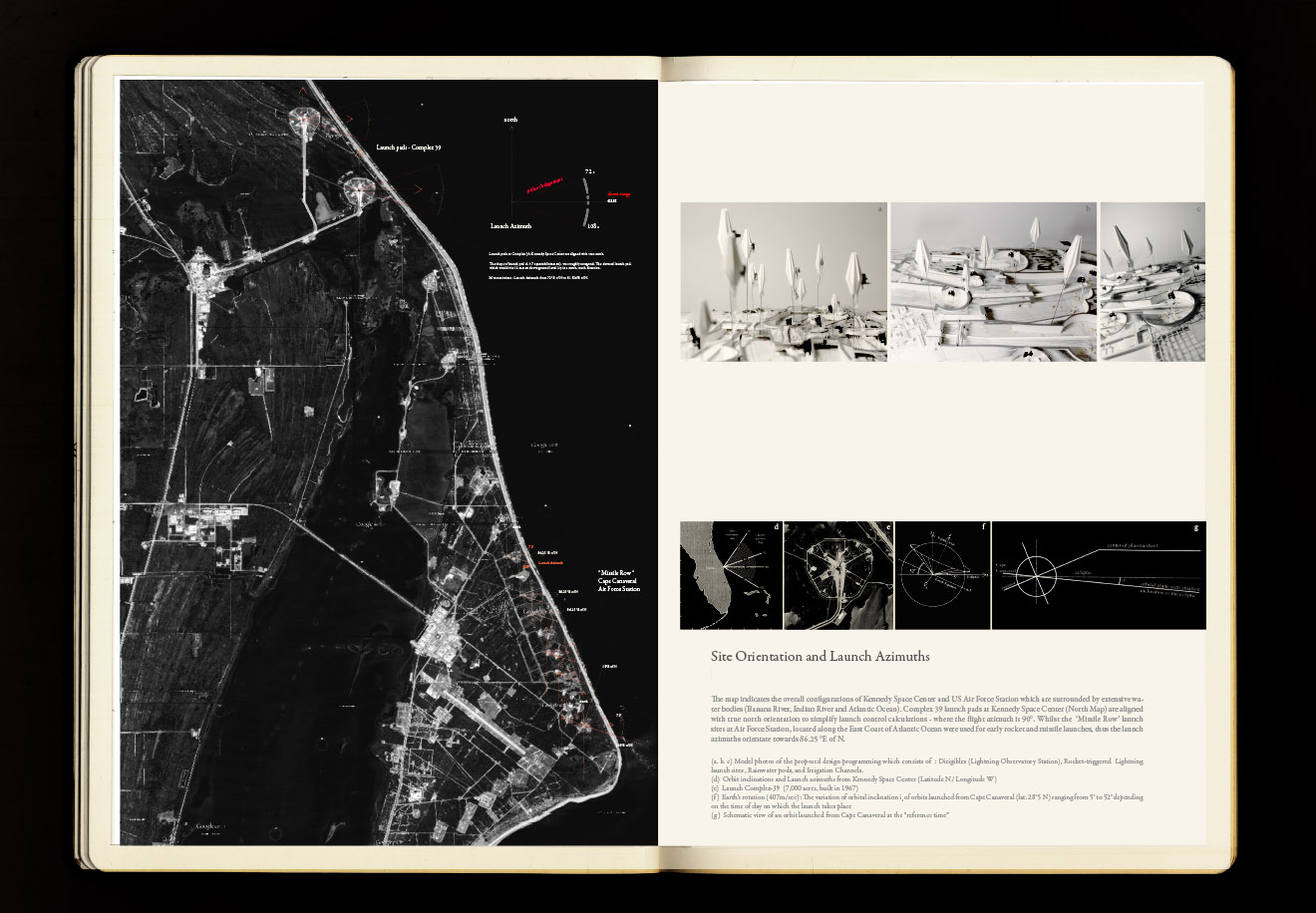

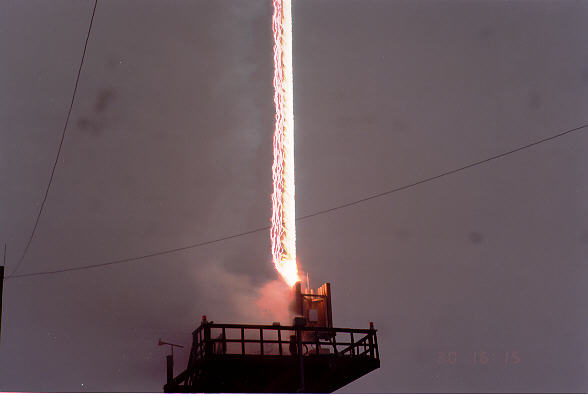

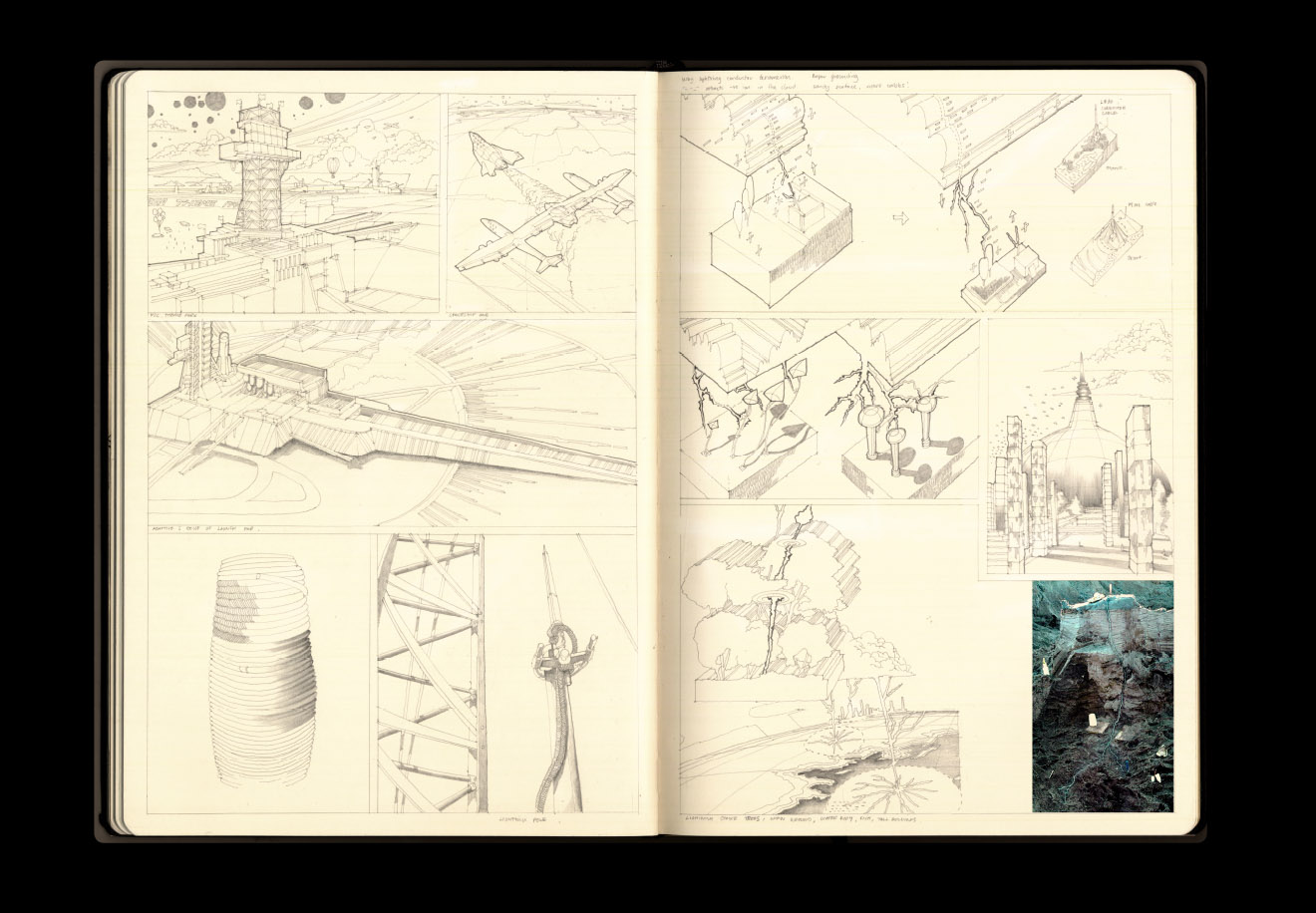

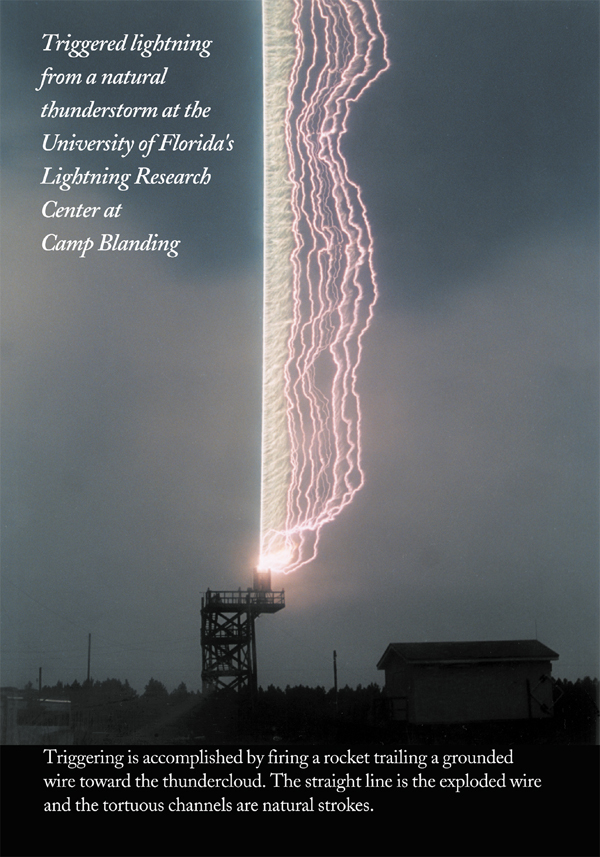

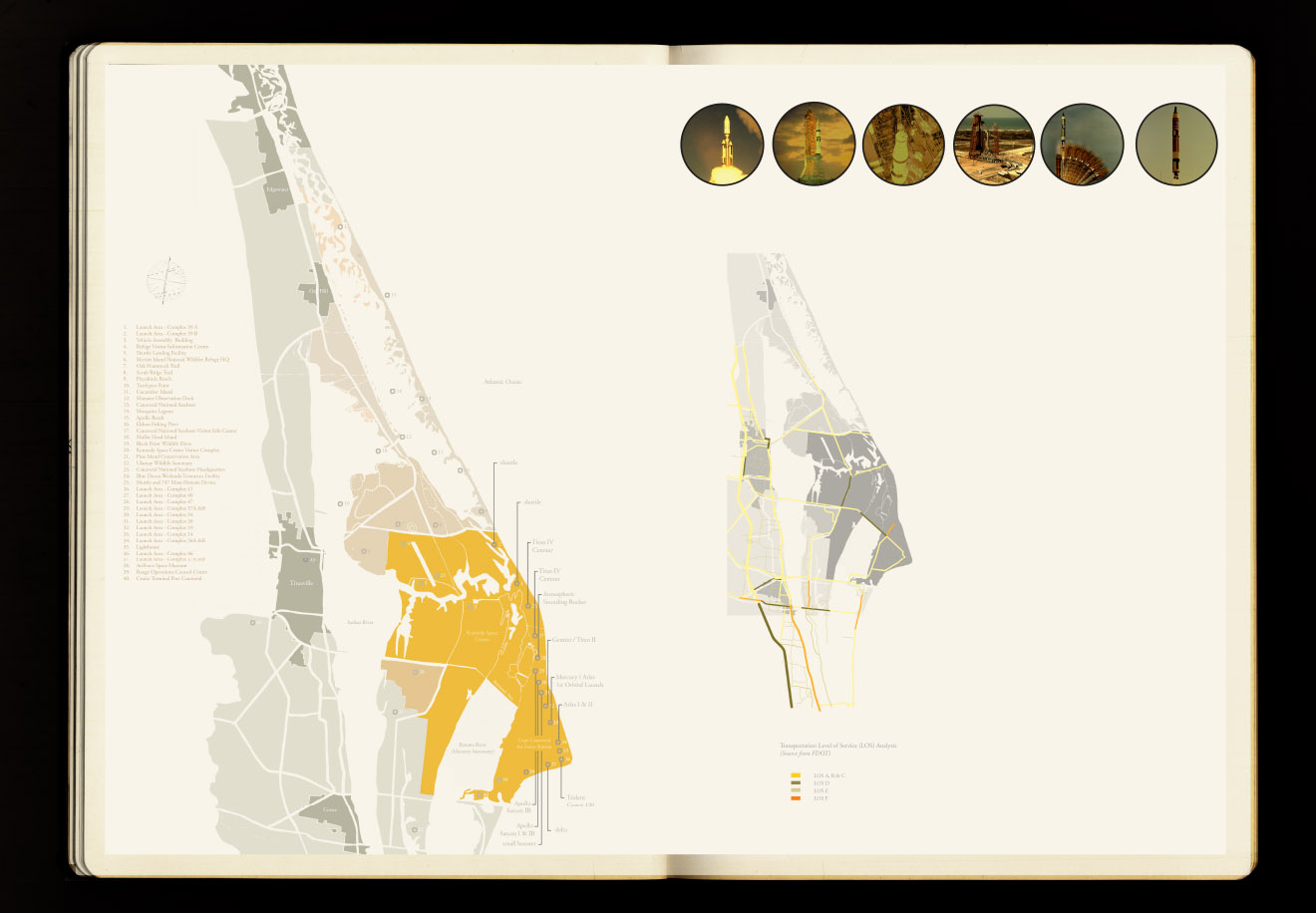

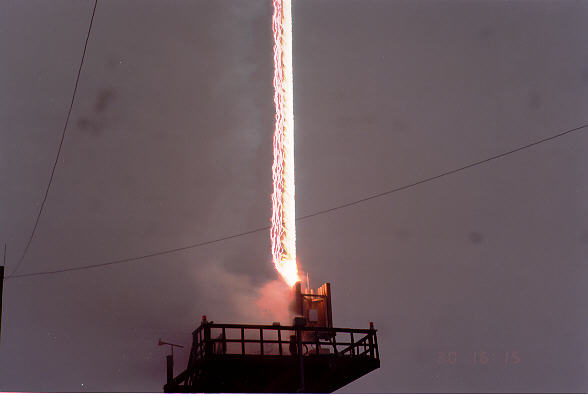

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida's Lightning Research Group].

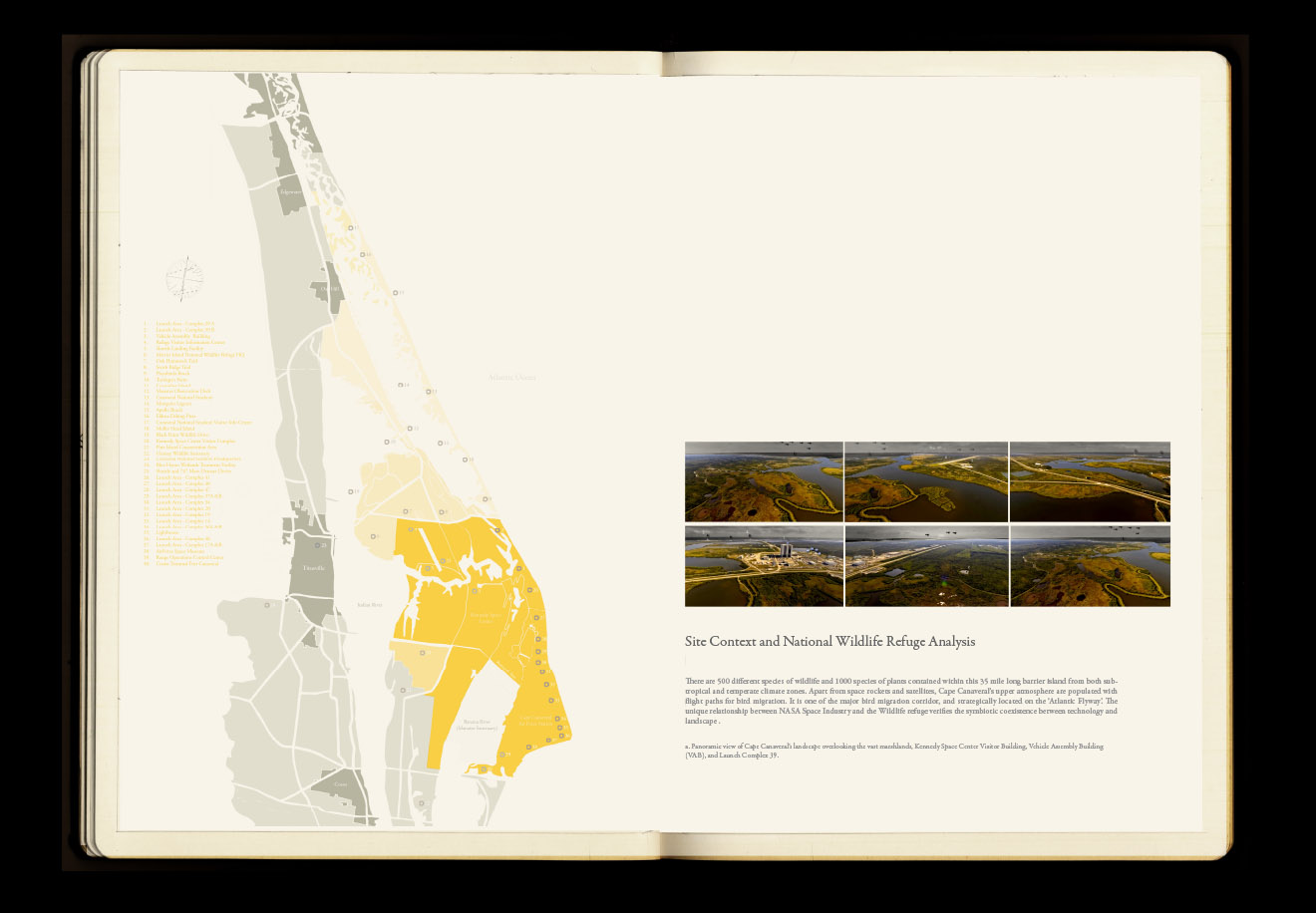

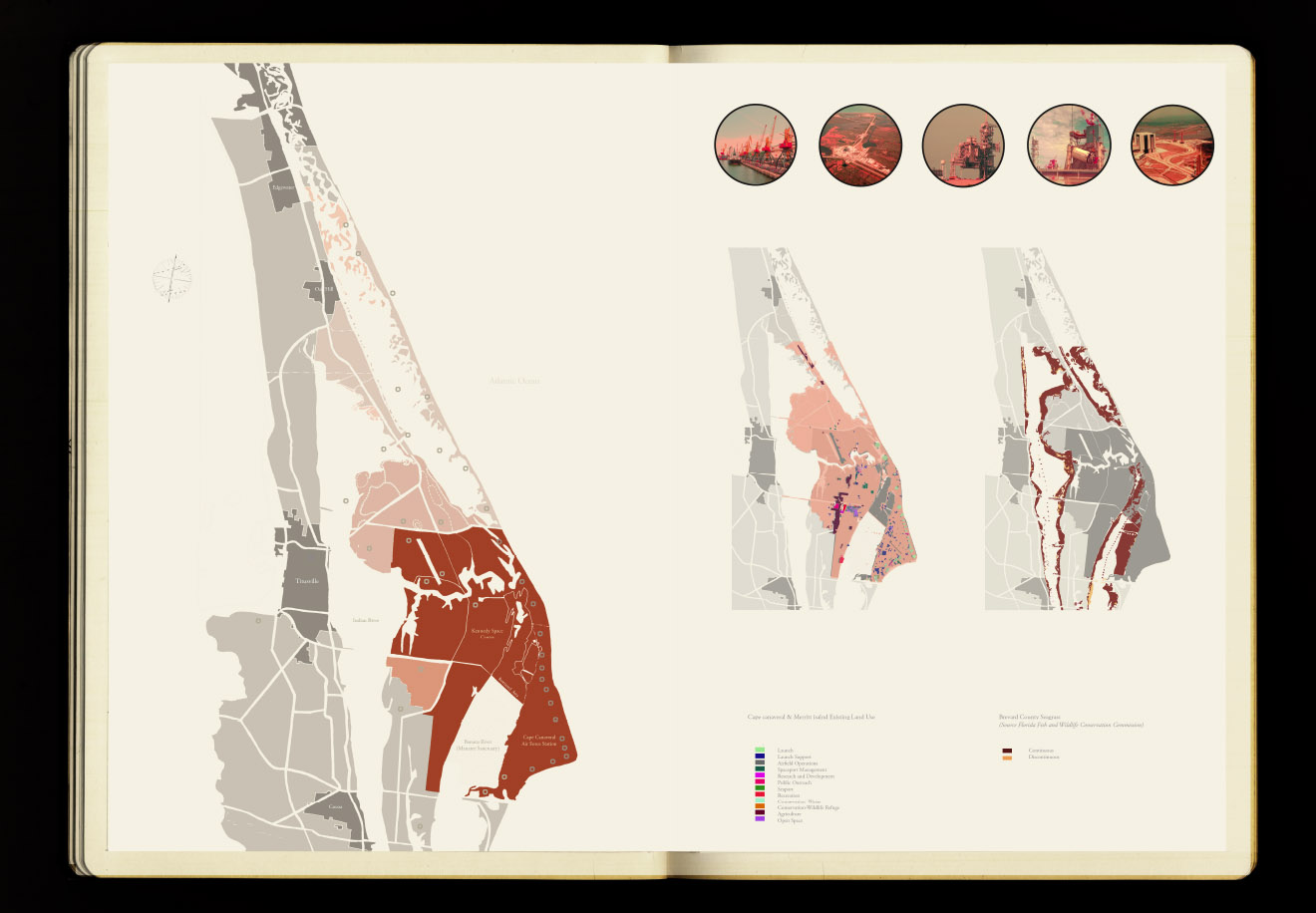

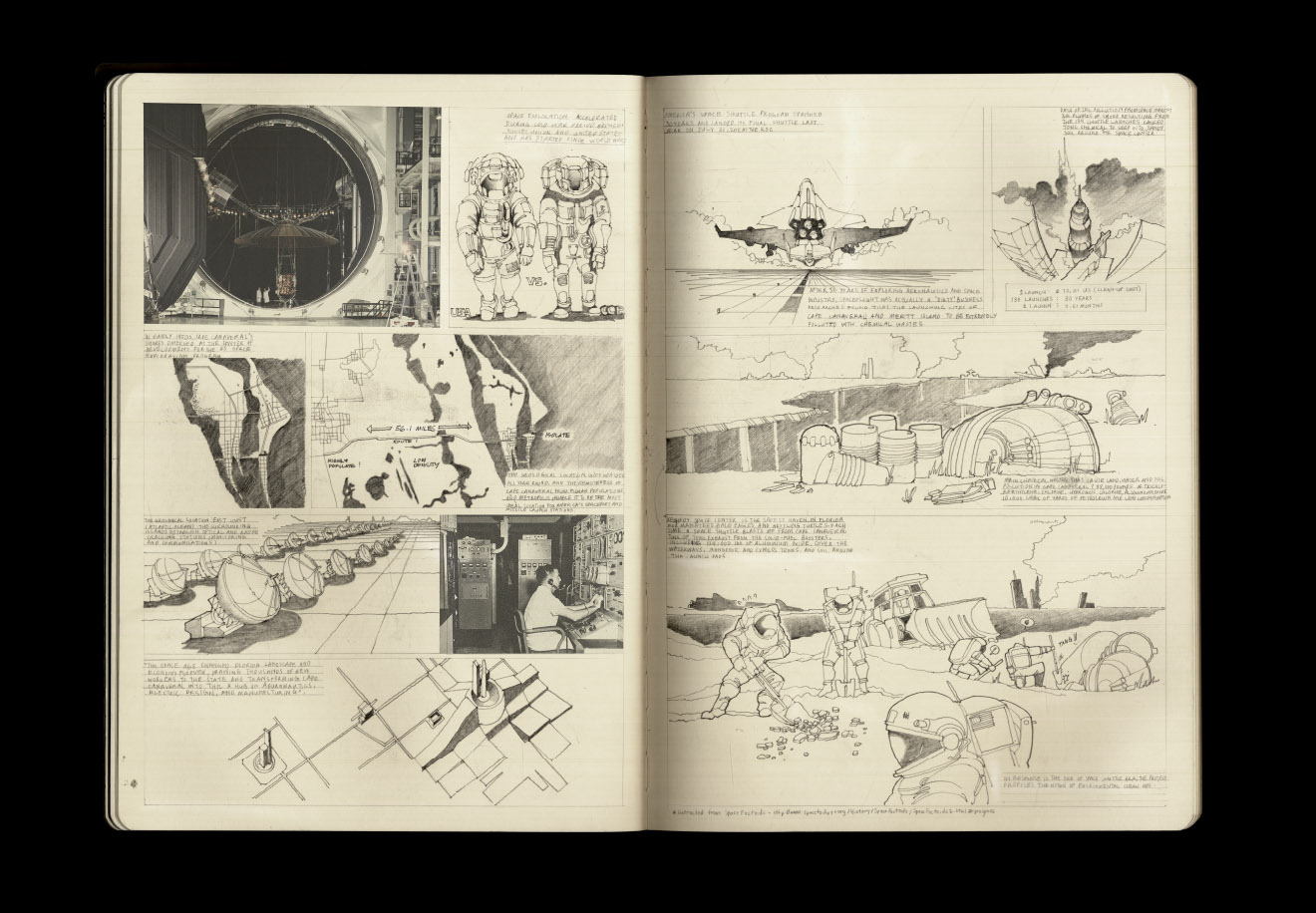

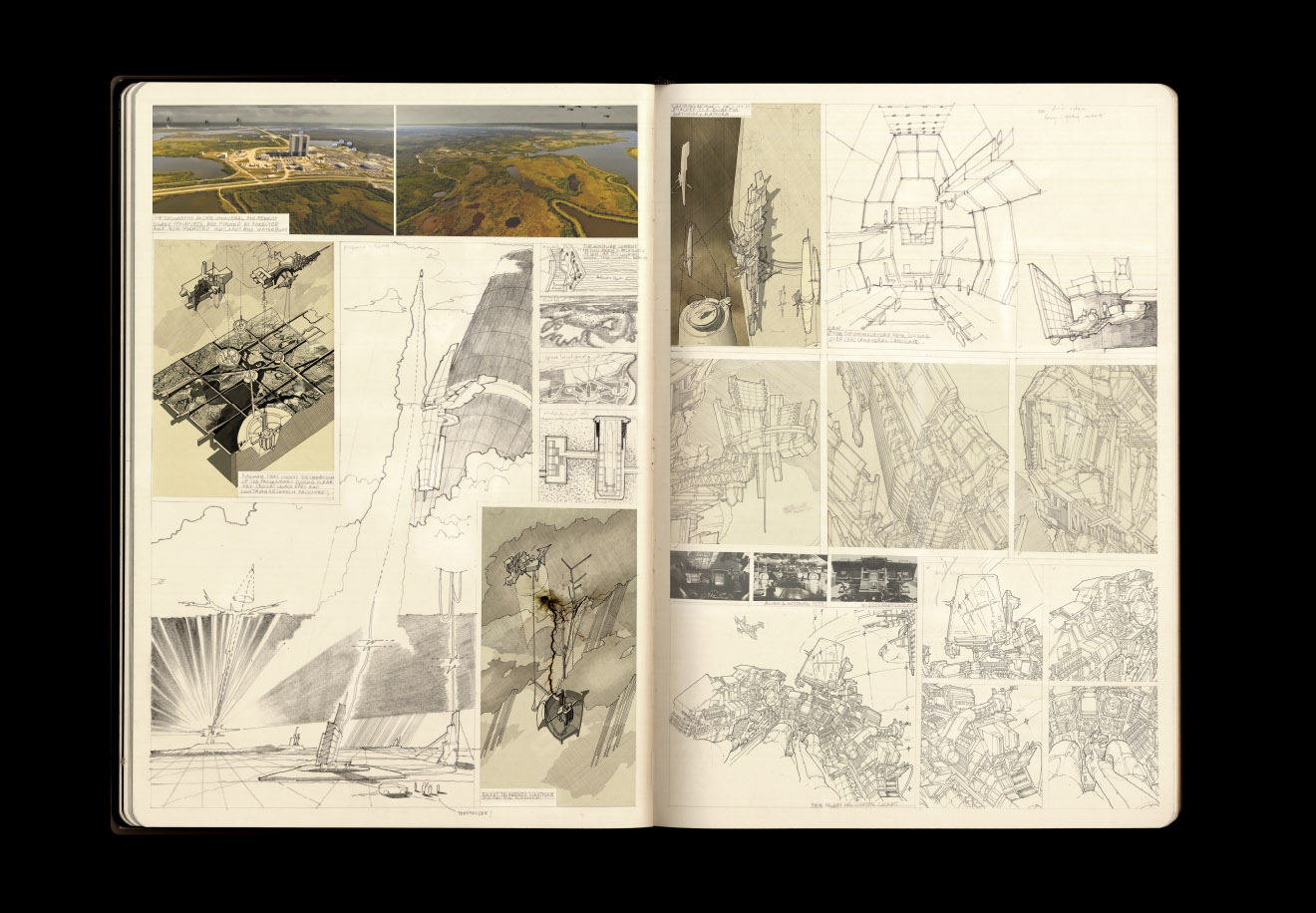

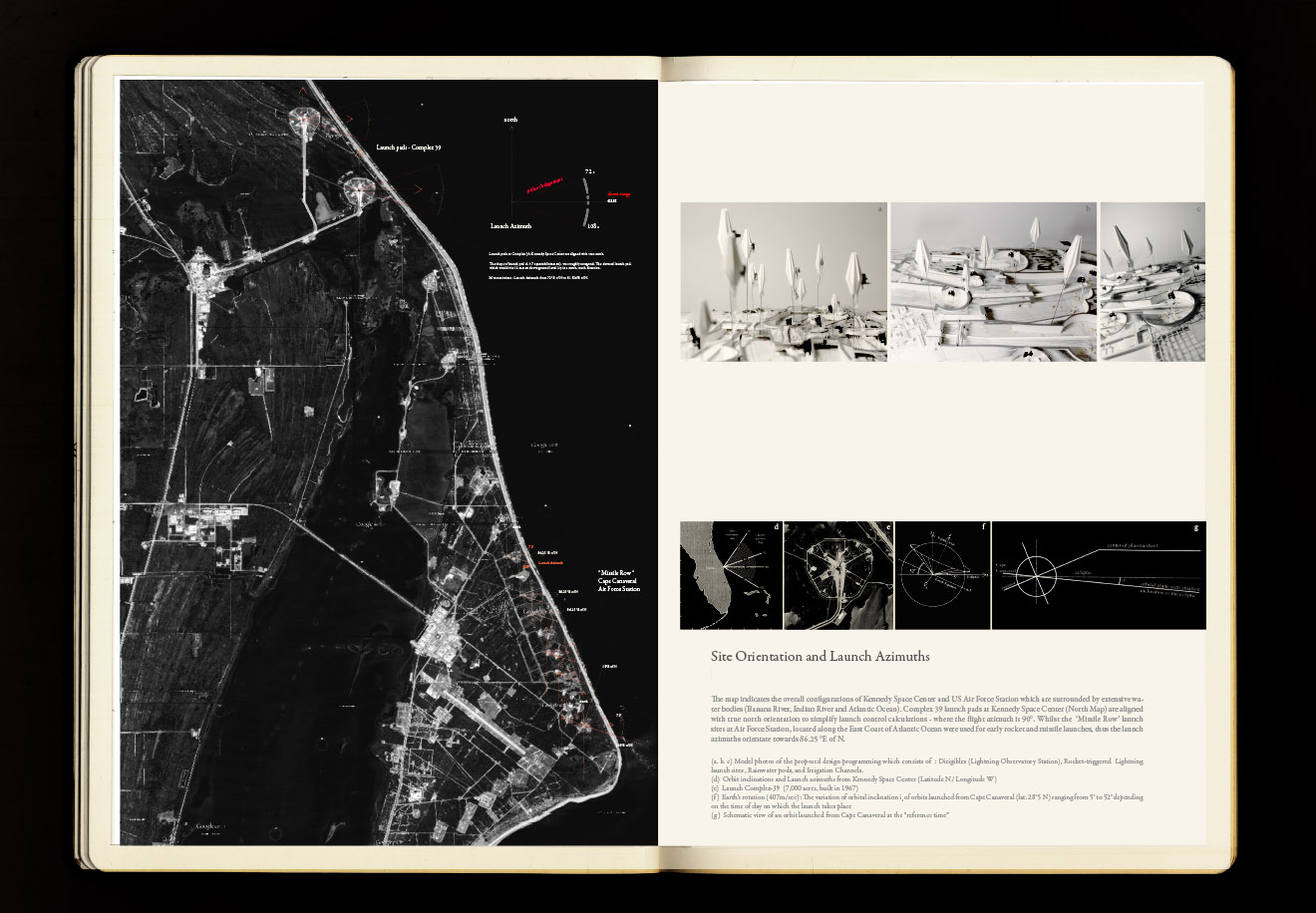

This past winter, I had the pleasure of traveling around south Florida with Smout Allen, Kyle Buchanan, and nearly two dozen students from Unit 11 at the Bartlett School of Architecture.

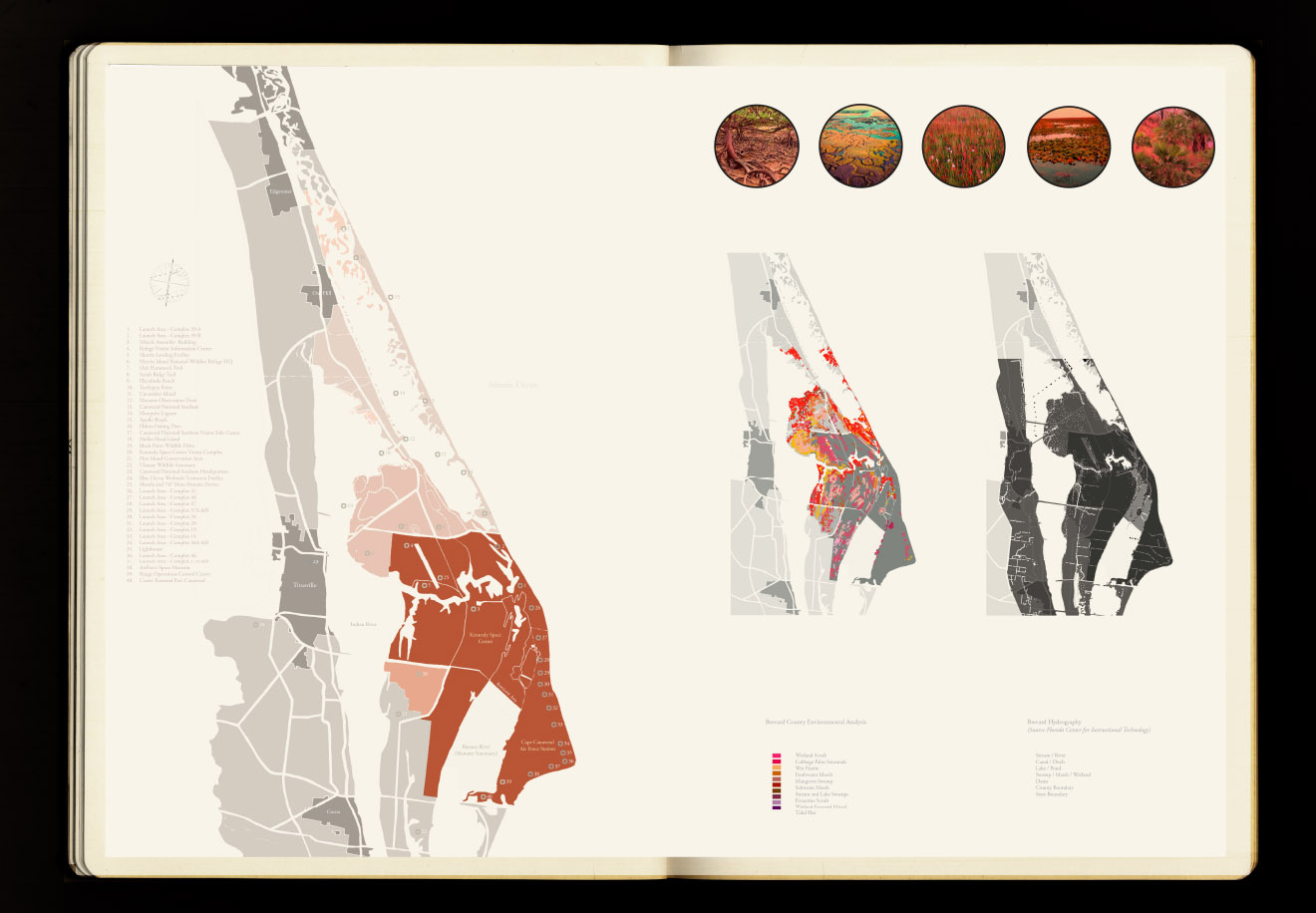

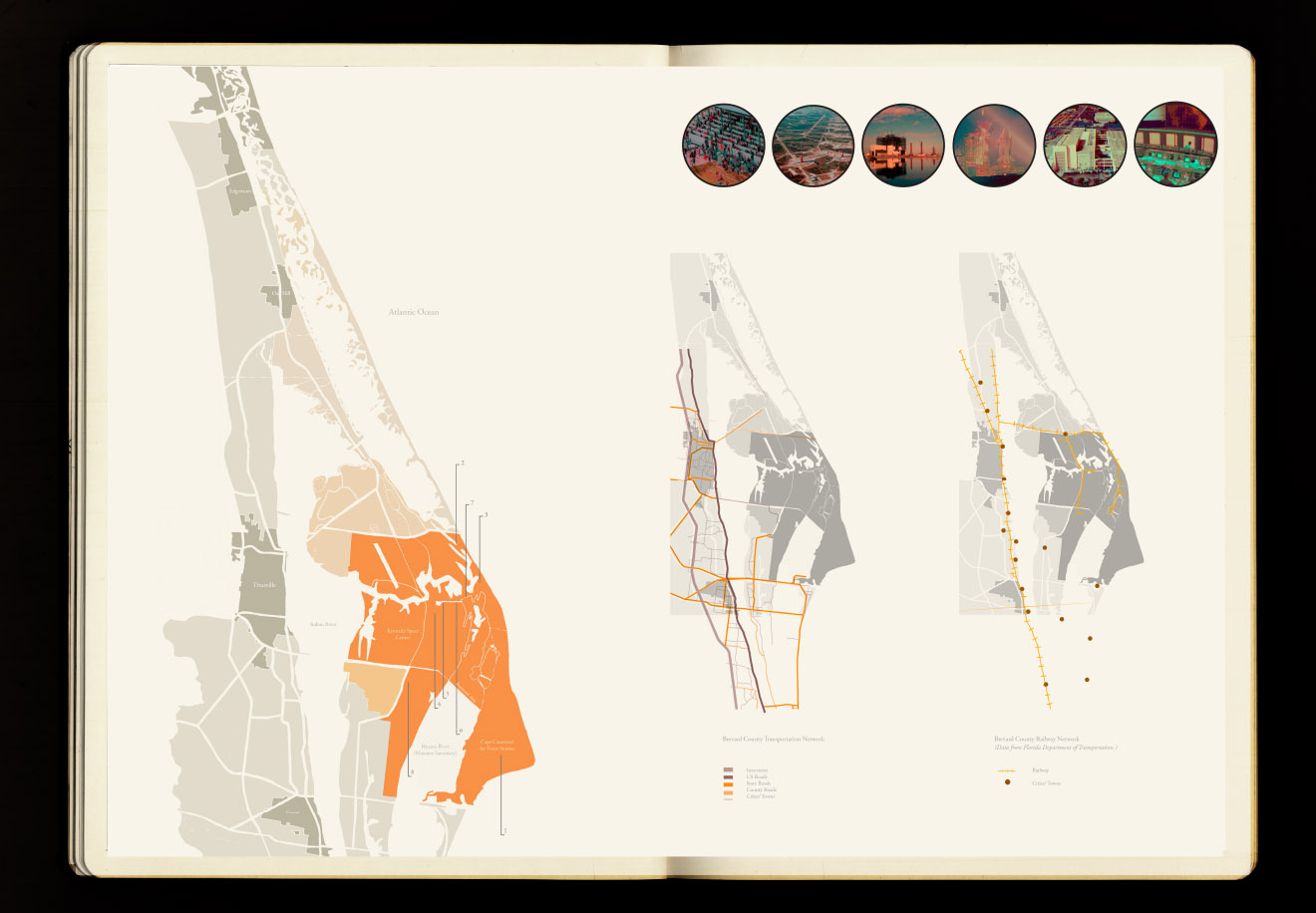

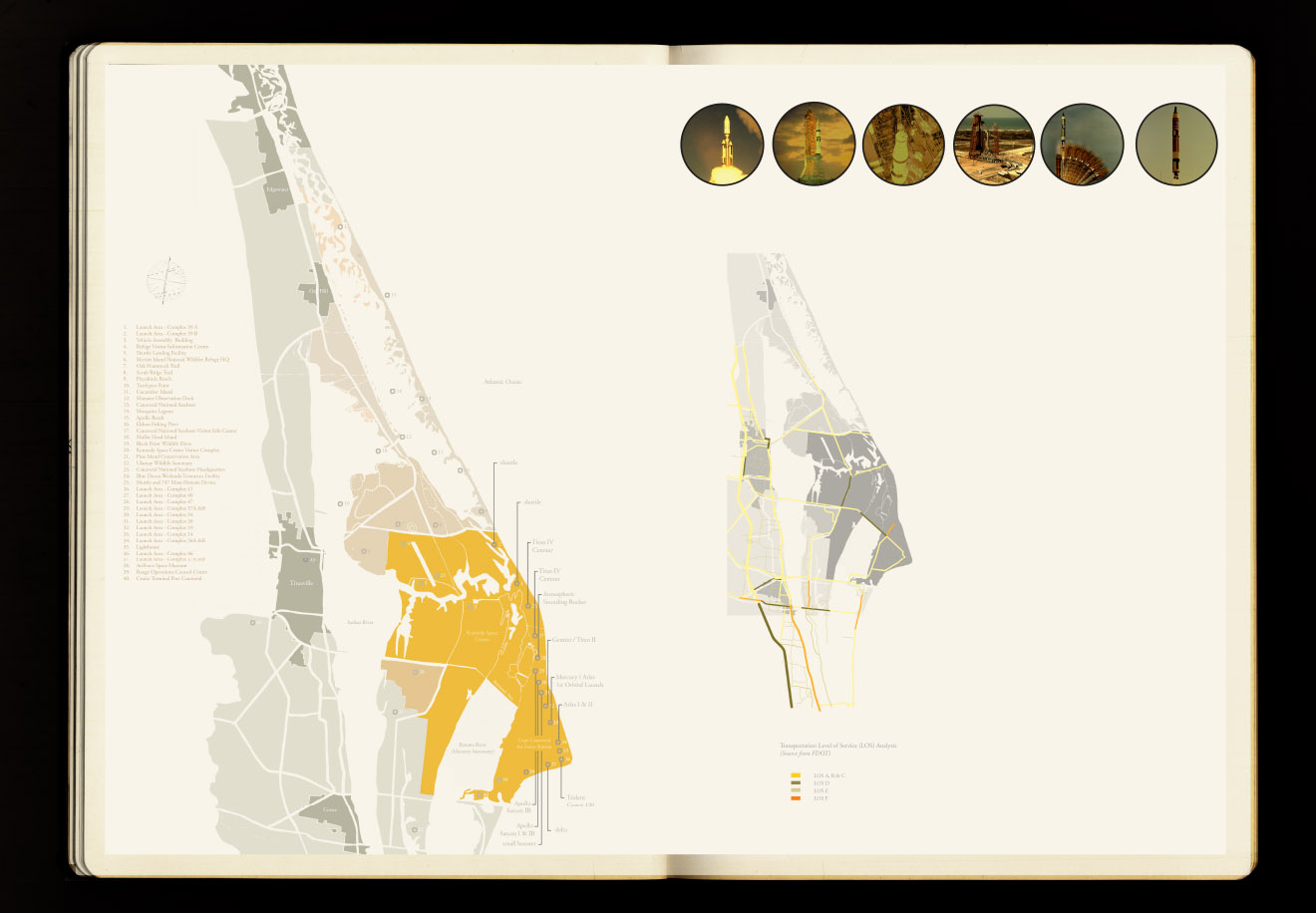

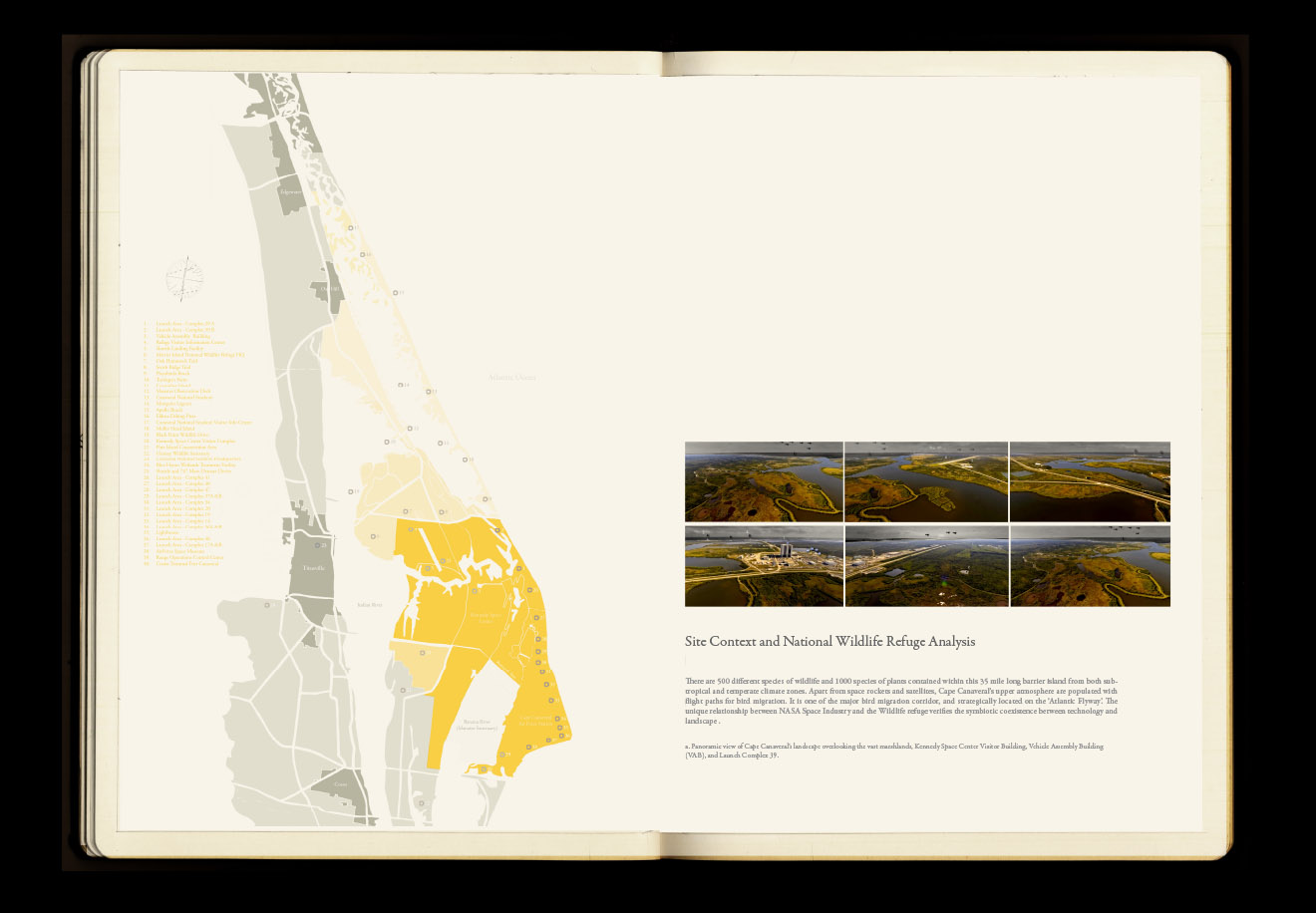

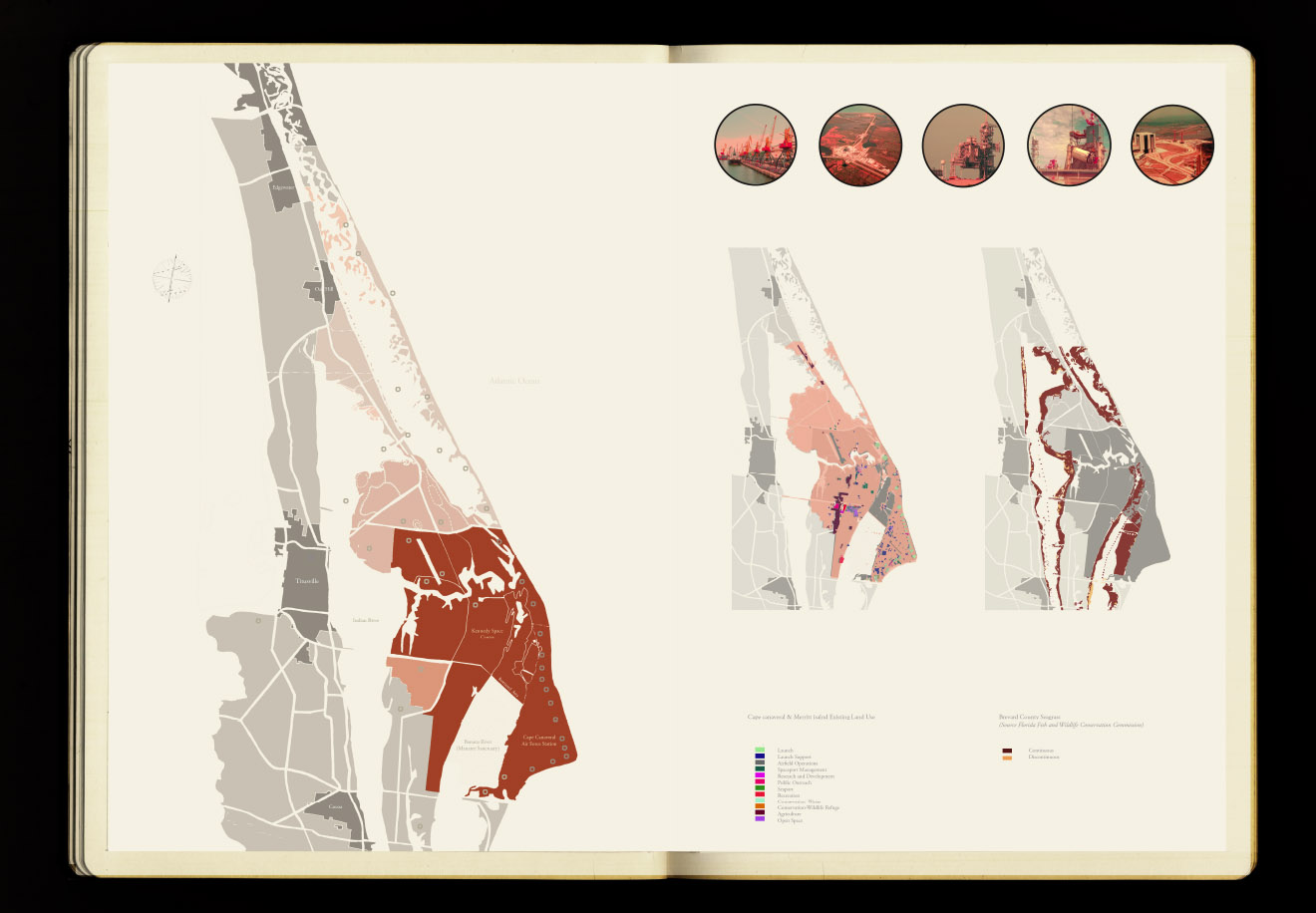

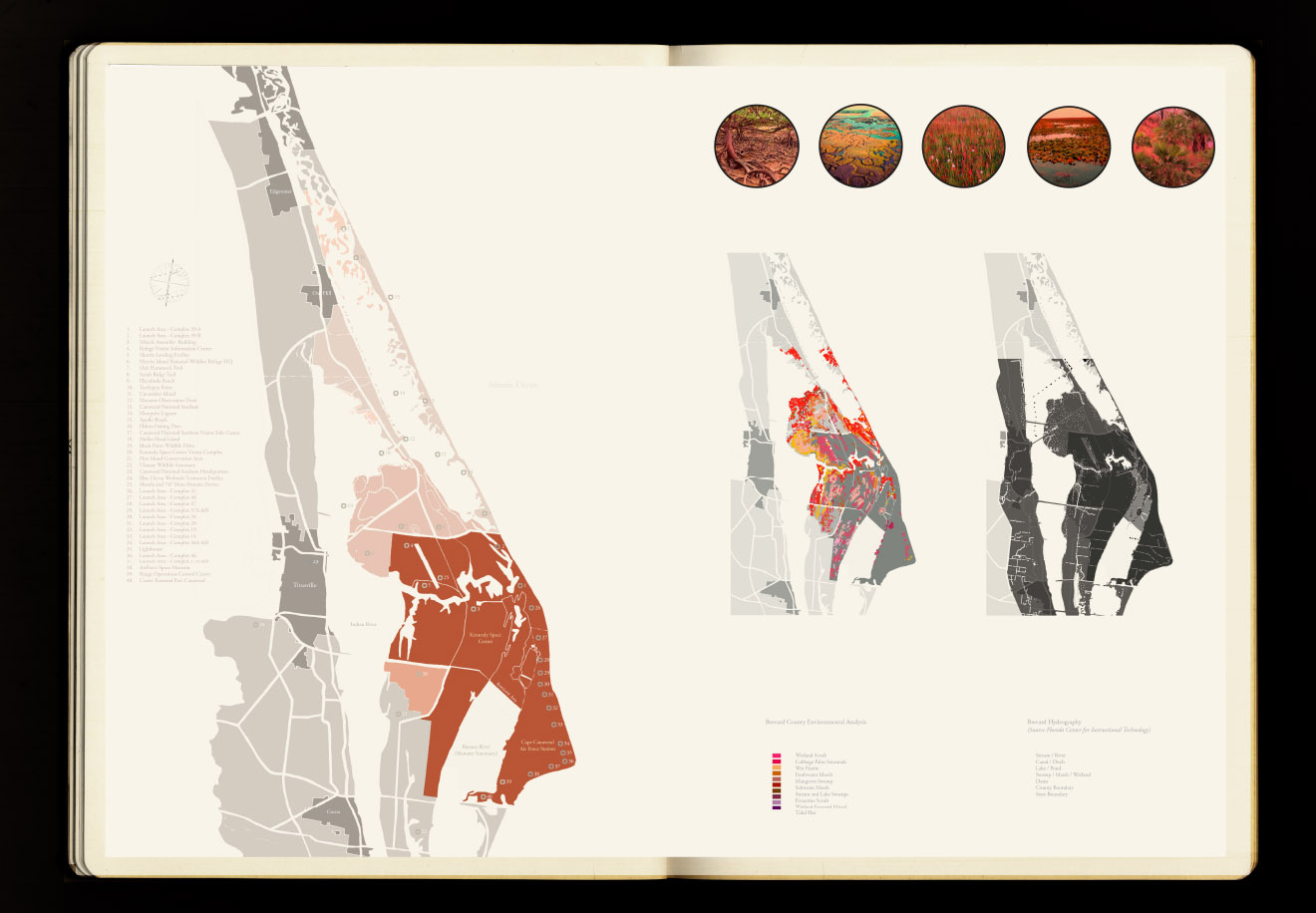

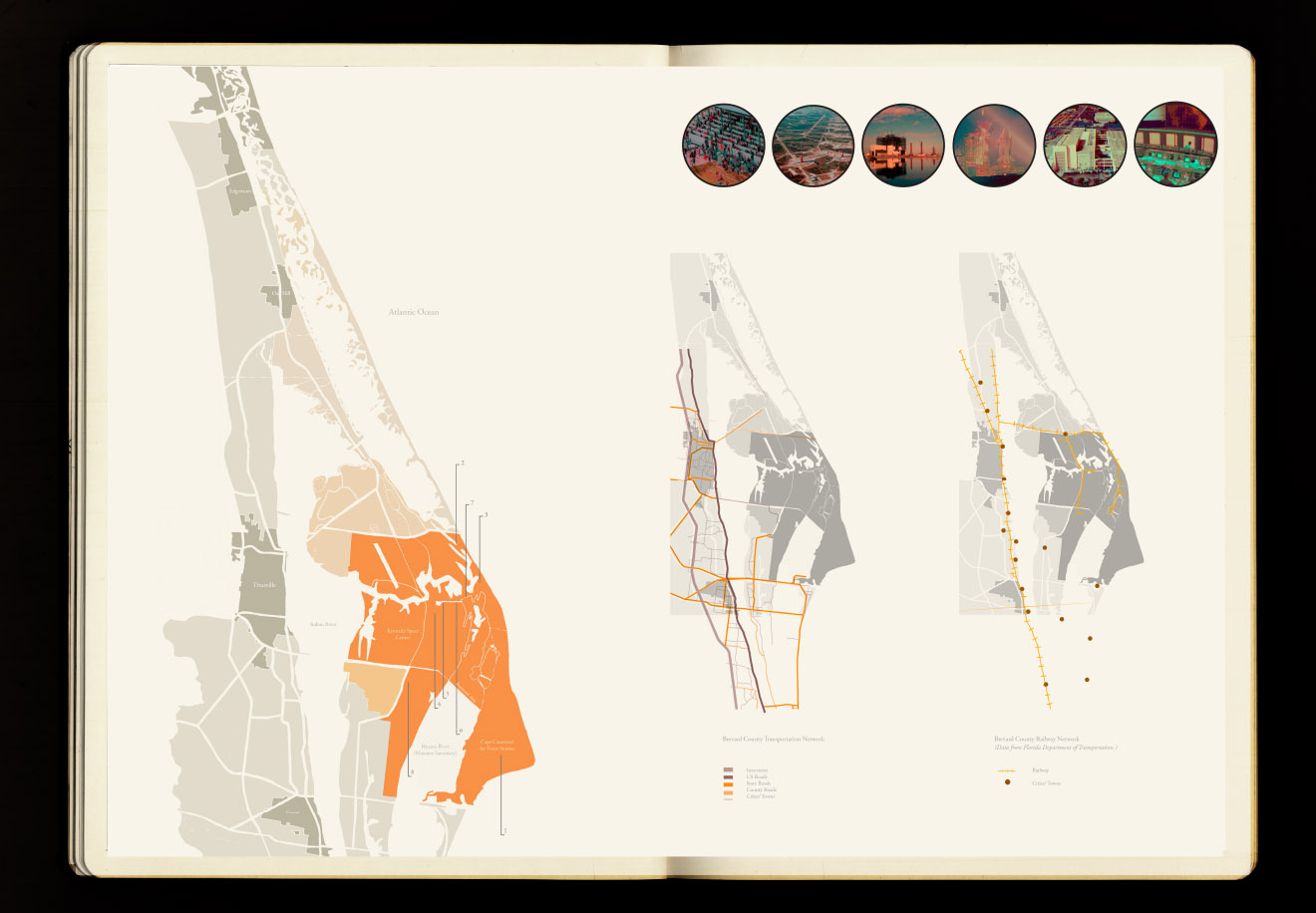

Florida's variable terrains—of sink holes, swamps, and eroding beaches—and its Herculean infrastructure, from canals and freeways to theme parks and rocket facilities, served as the narrative backdrop for the many architectural projects ultimately produced by the class (in addition, of course, to the 2012 U.S. Presidential election, the results of which we watched live from the bar of a tropical-themed hotel near Cape Canaveral, next door to Ron Jon).

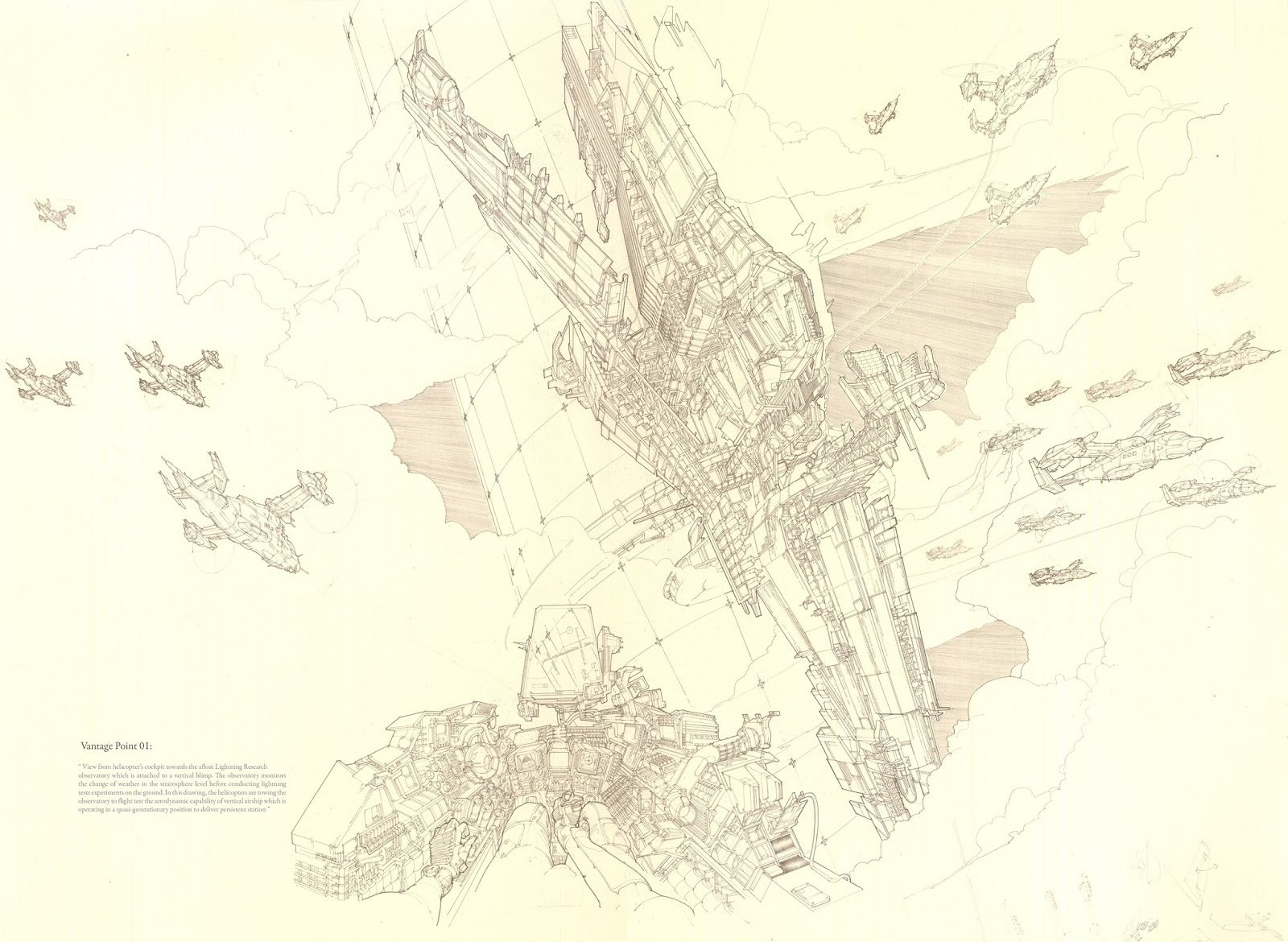

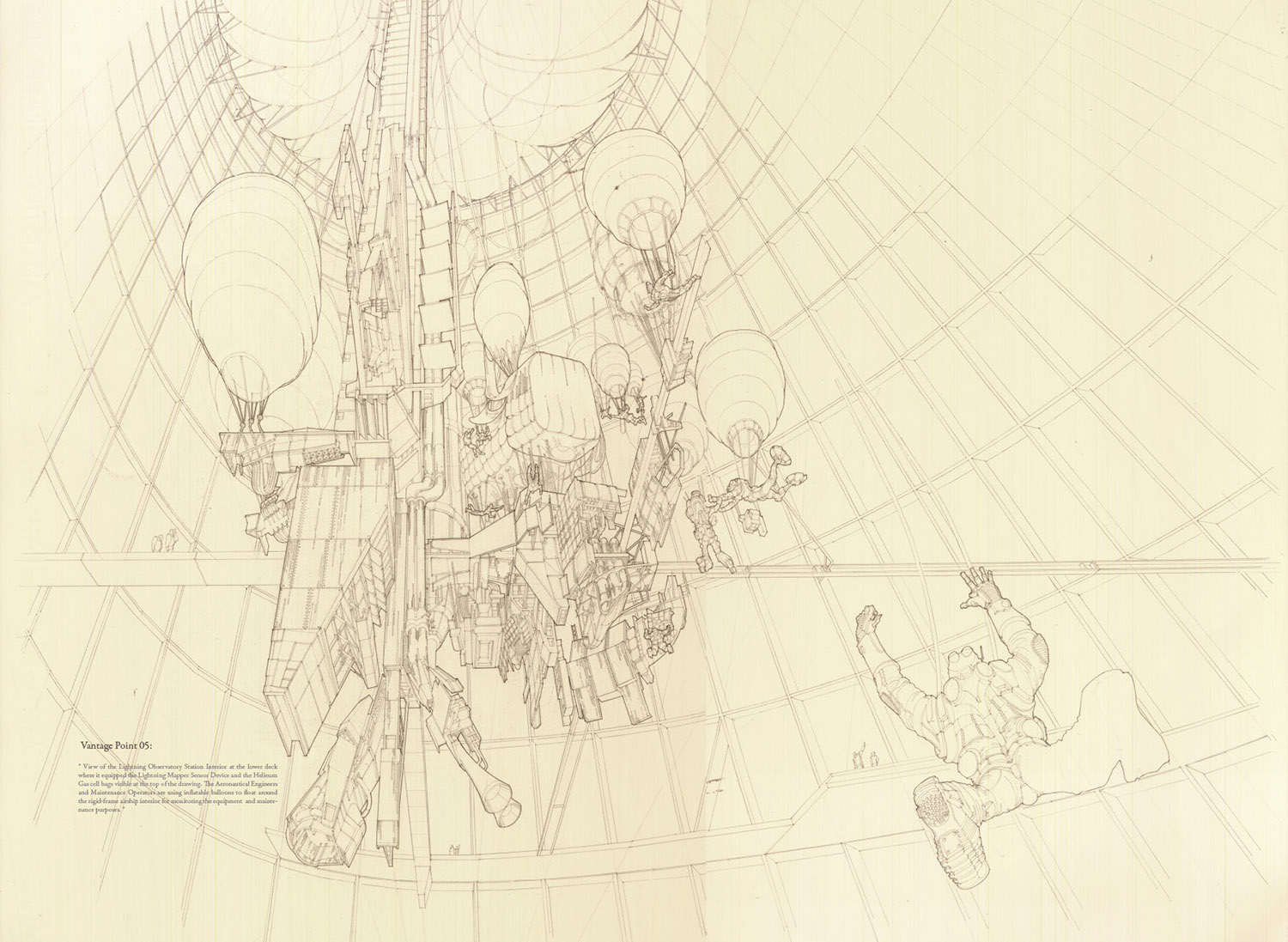

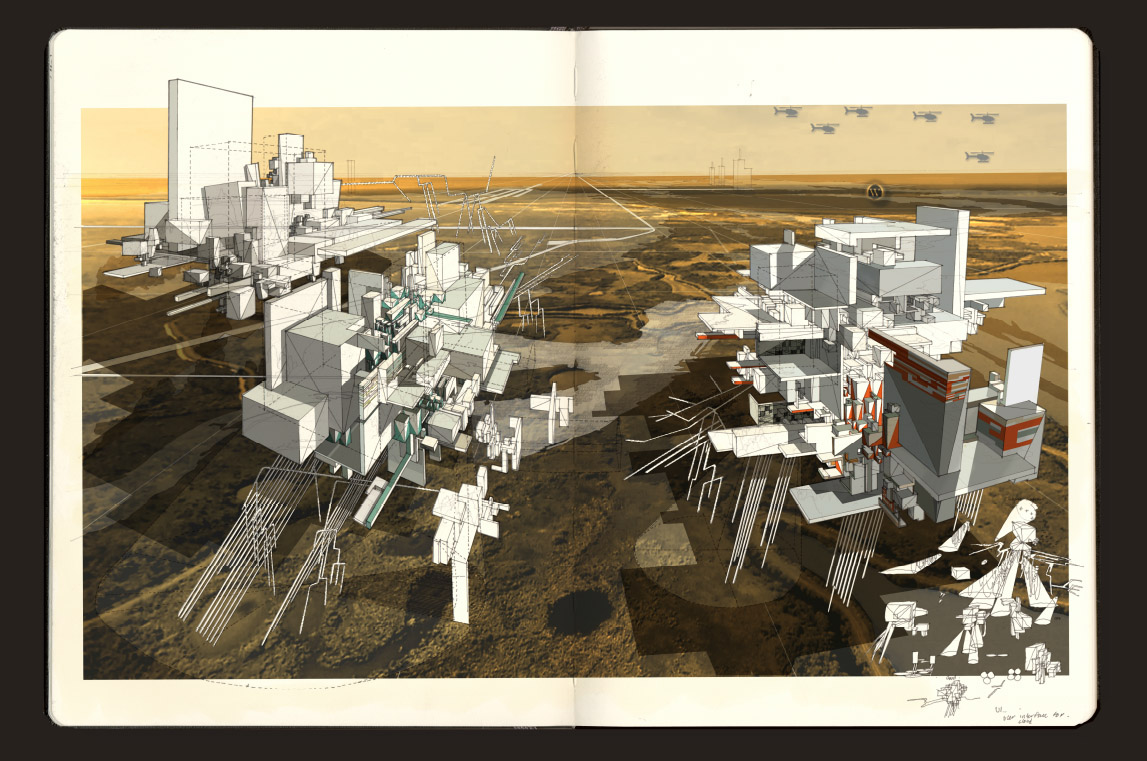

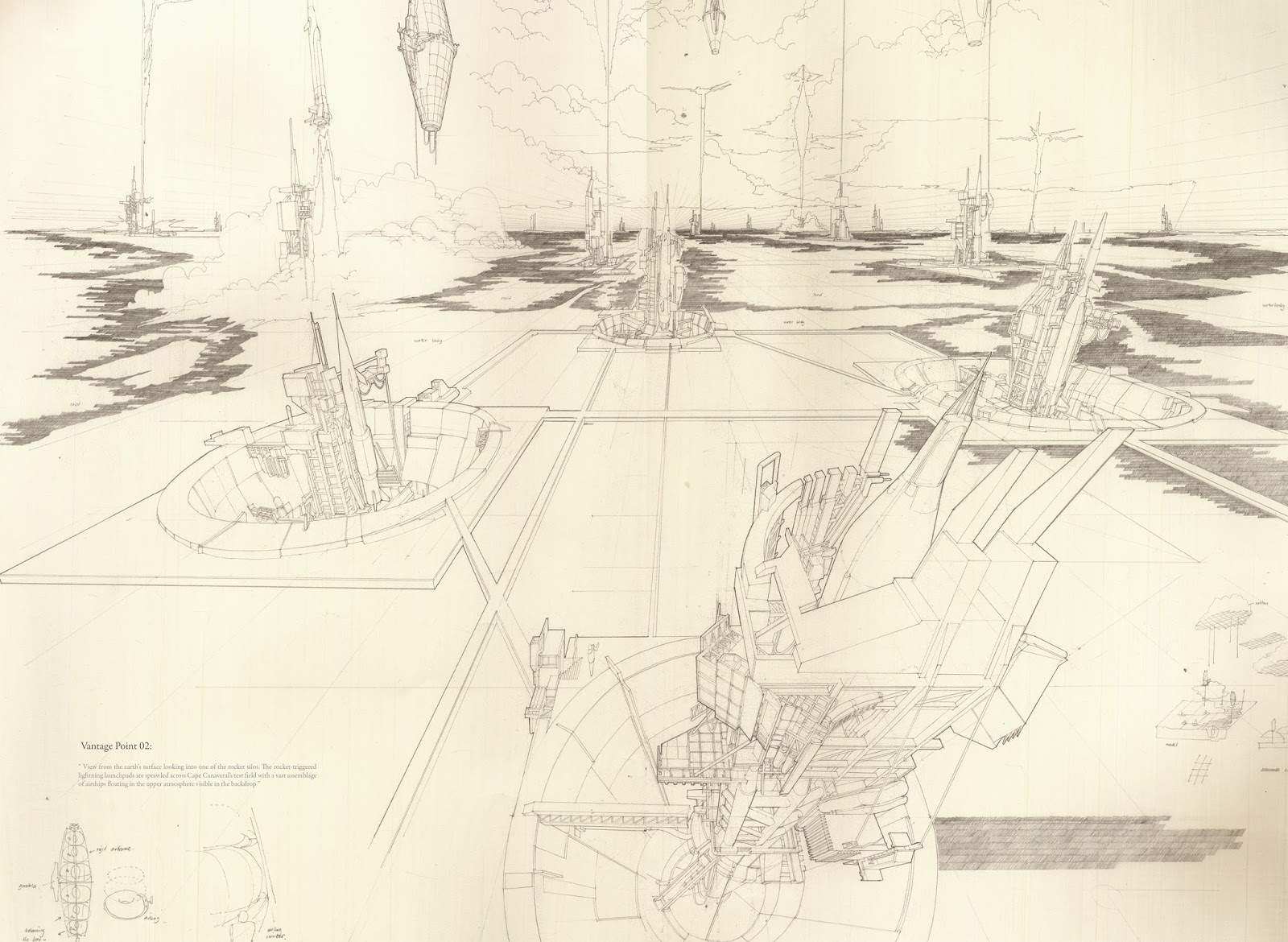

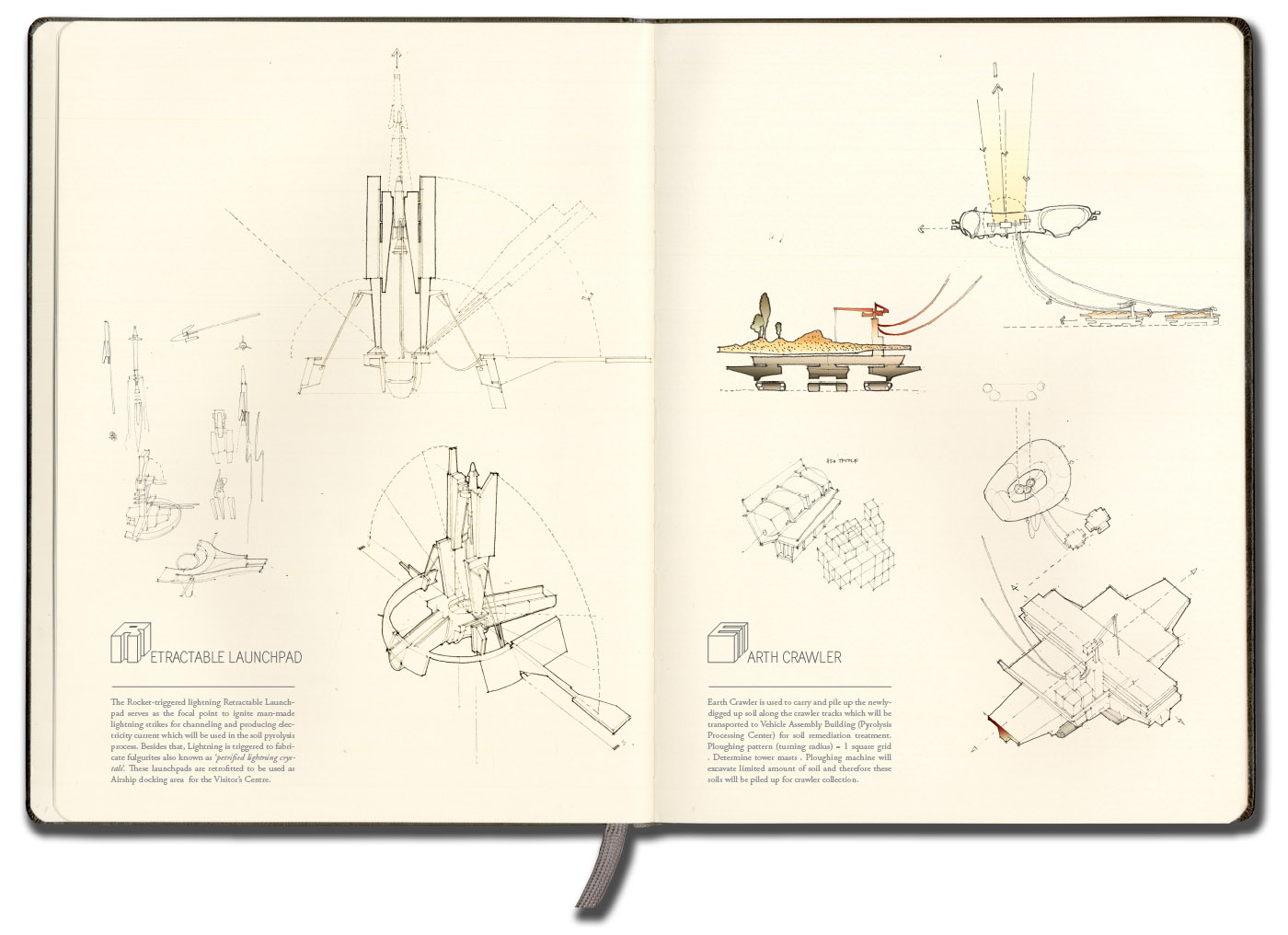

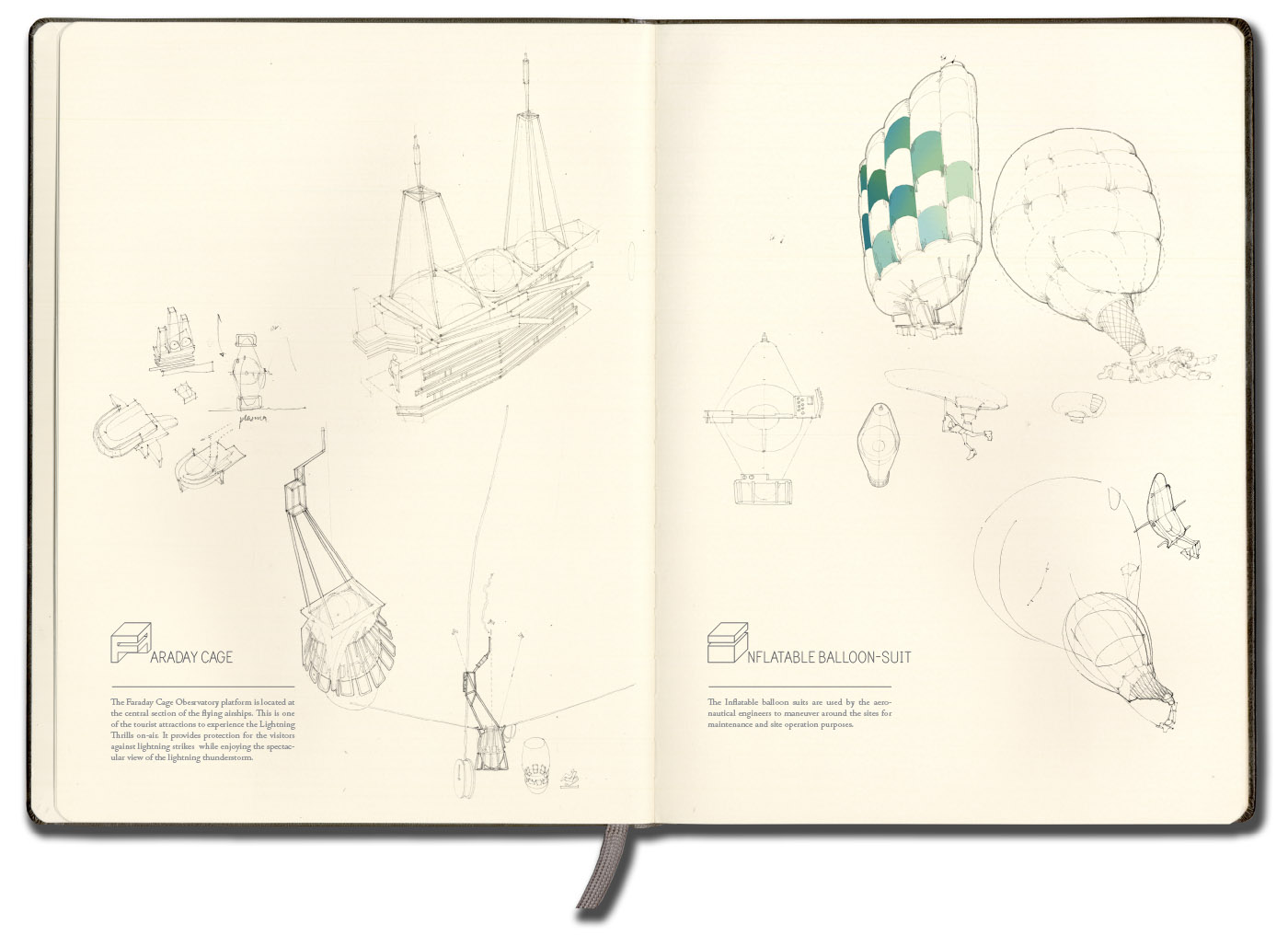

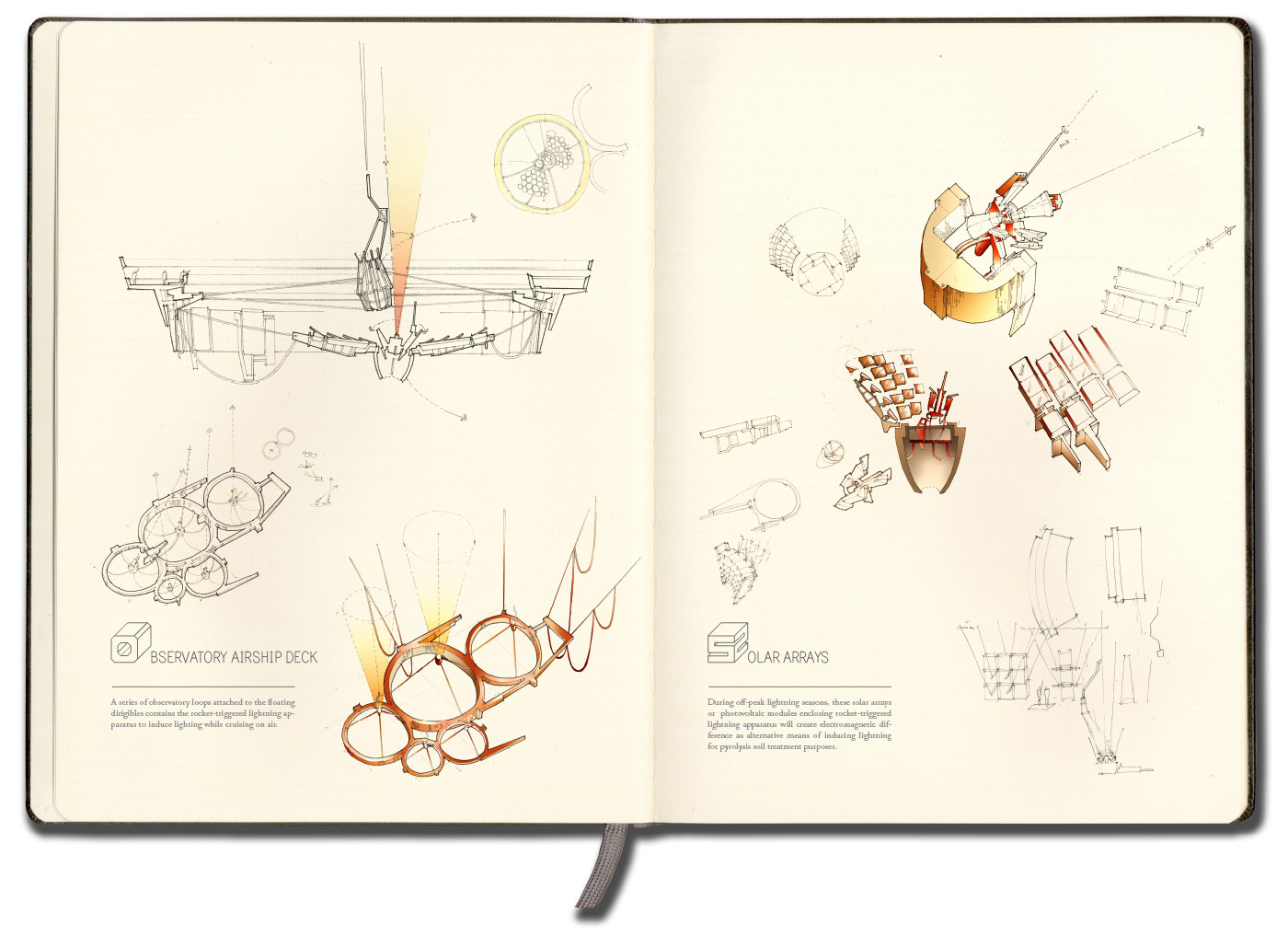

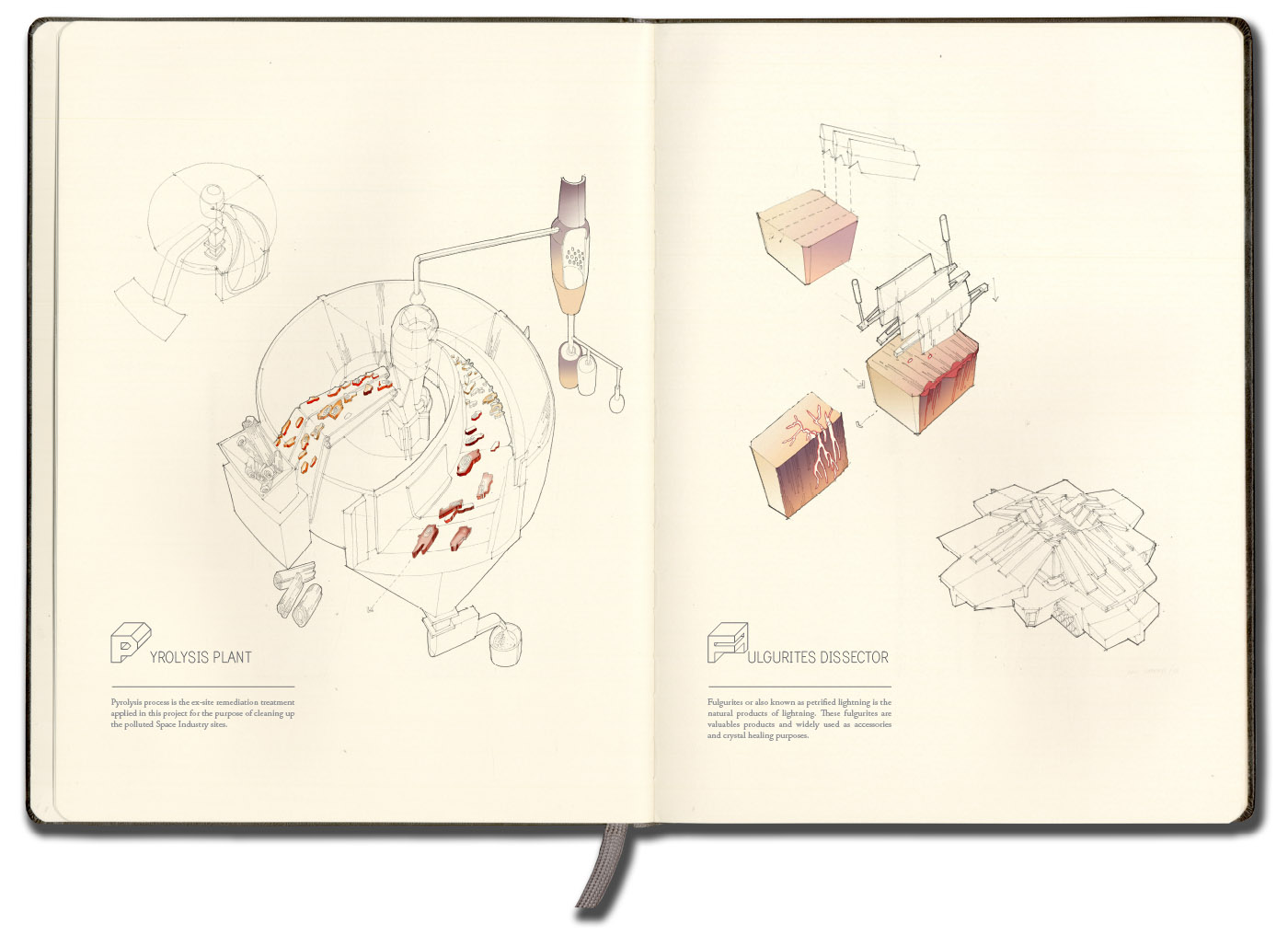

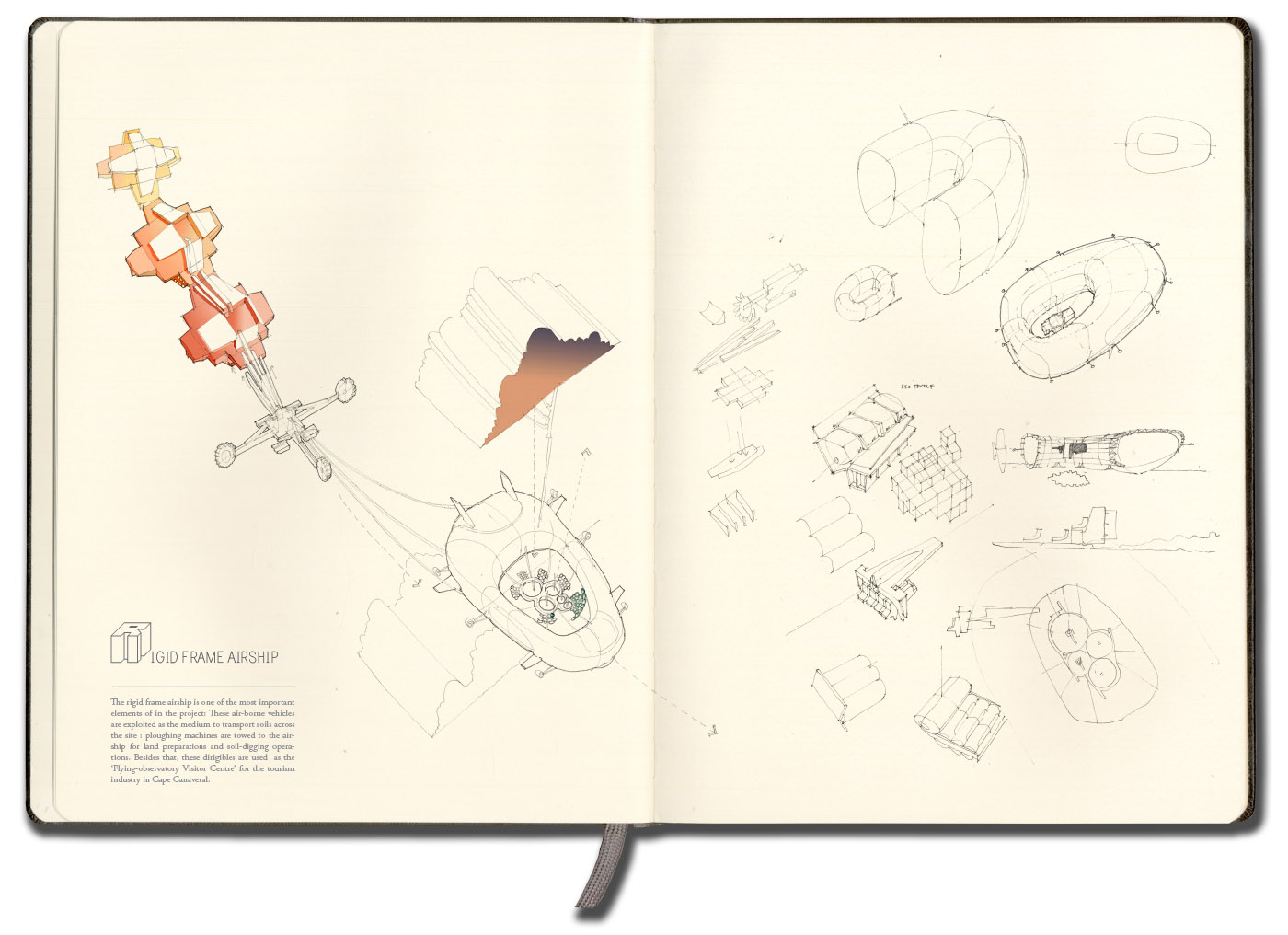

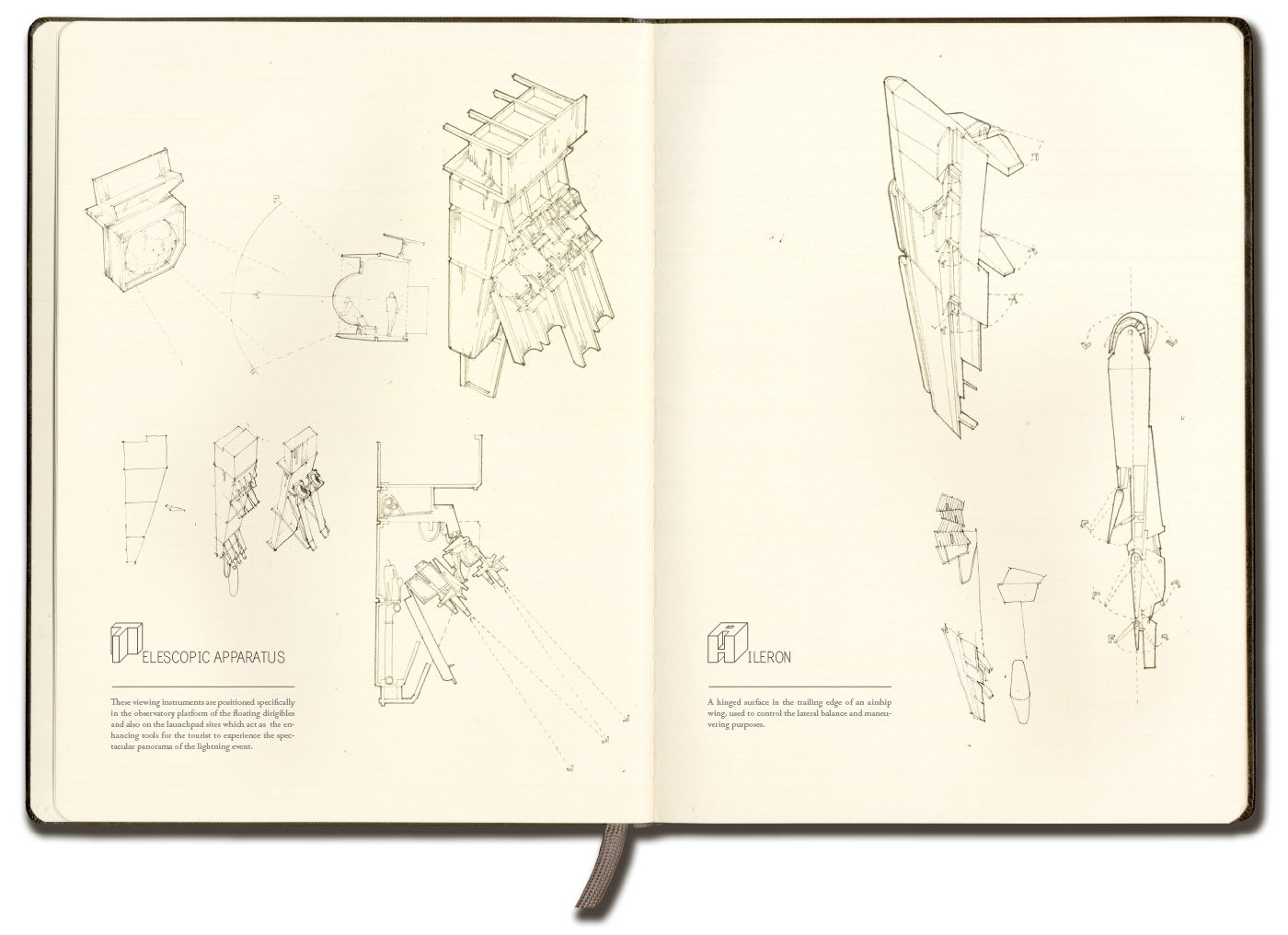

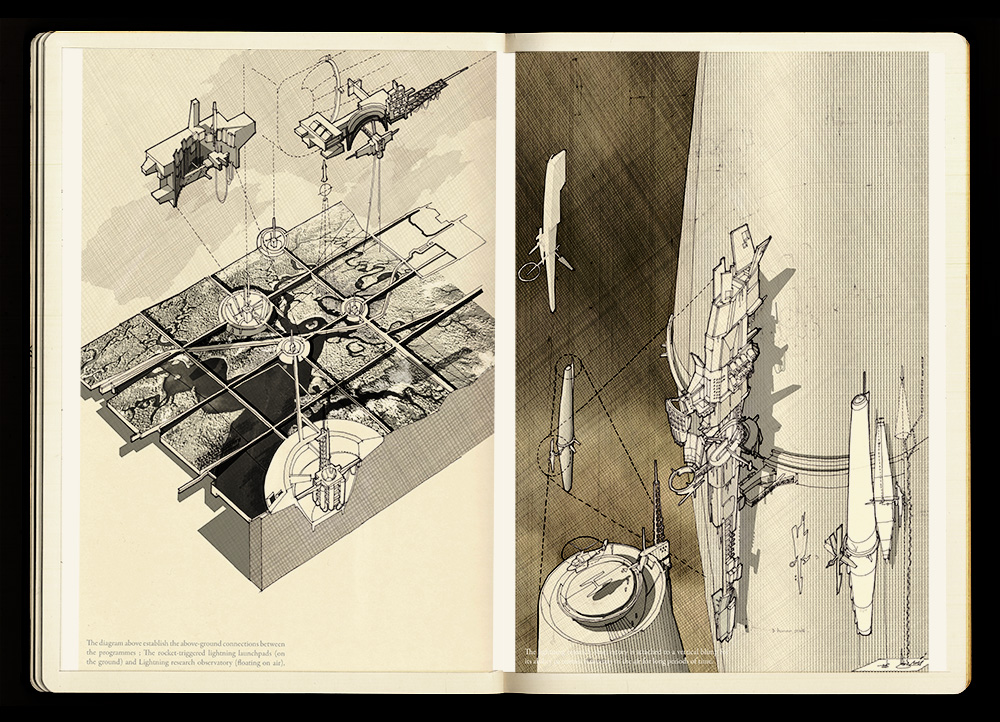

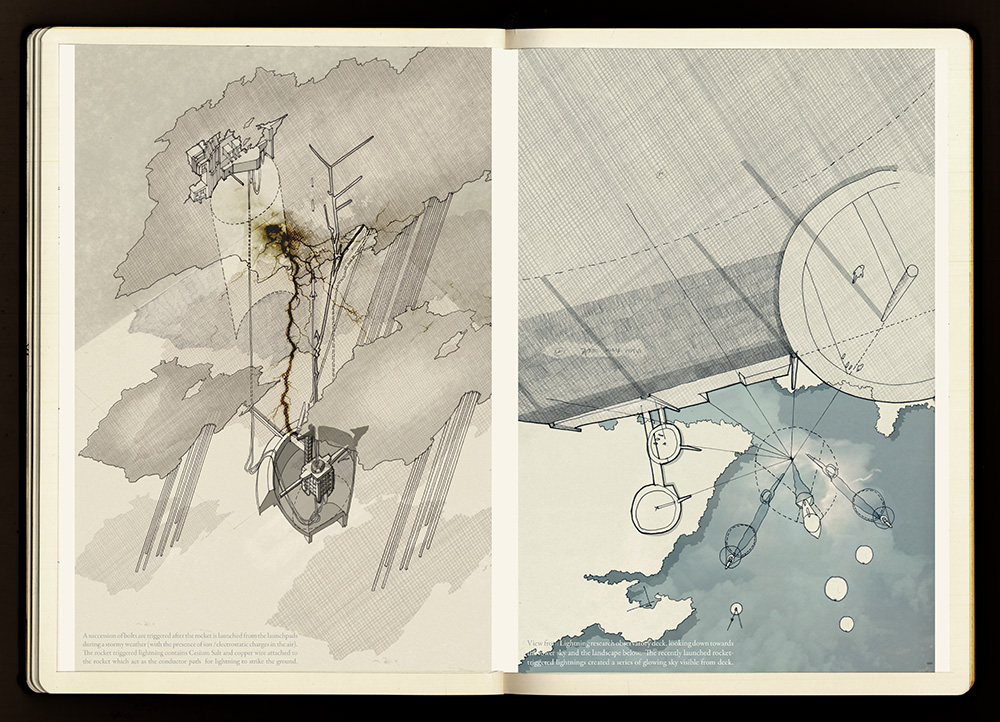

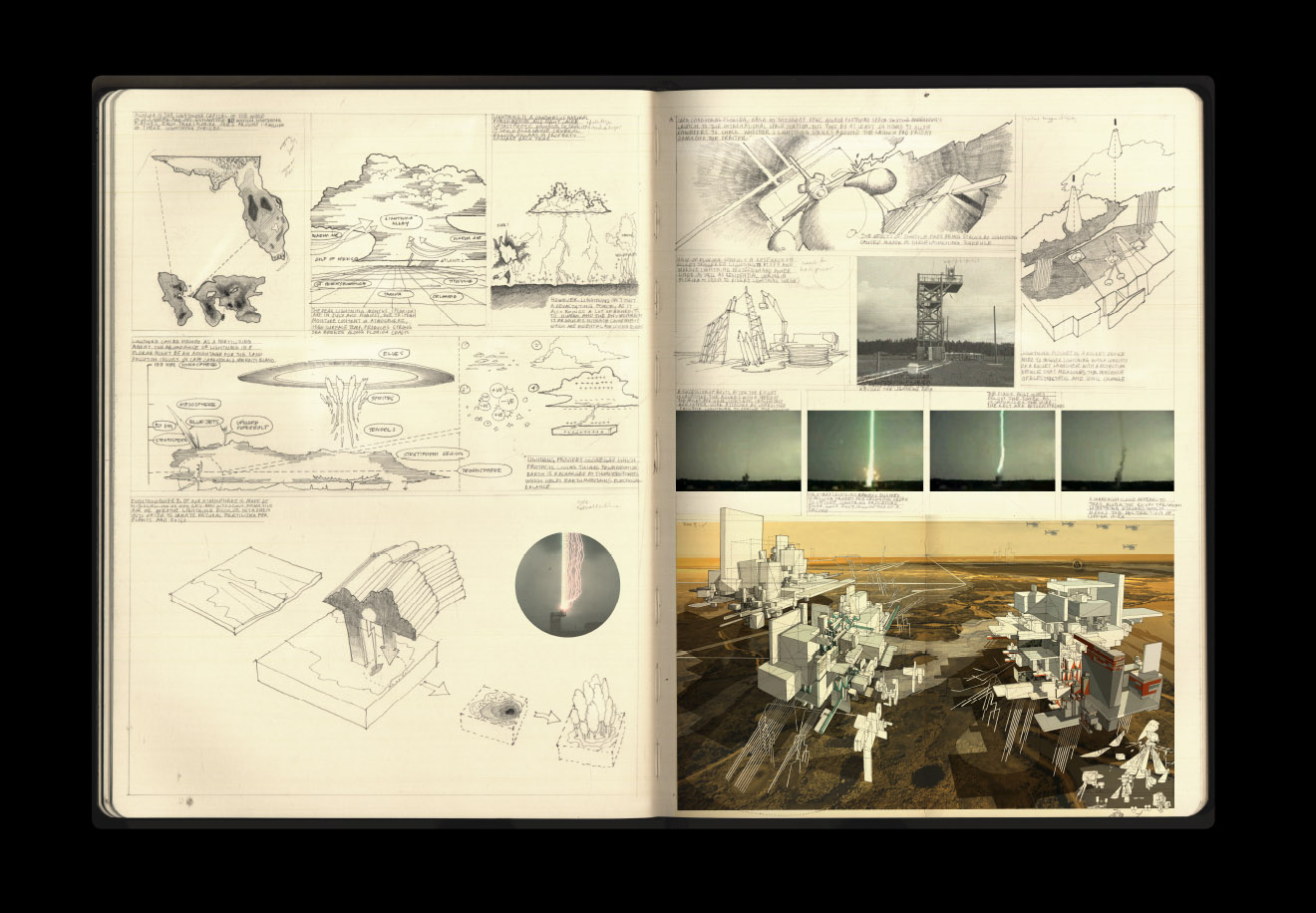

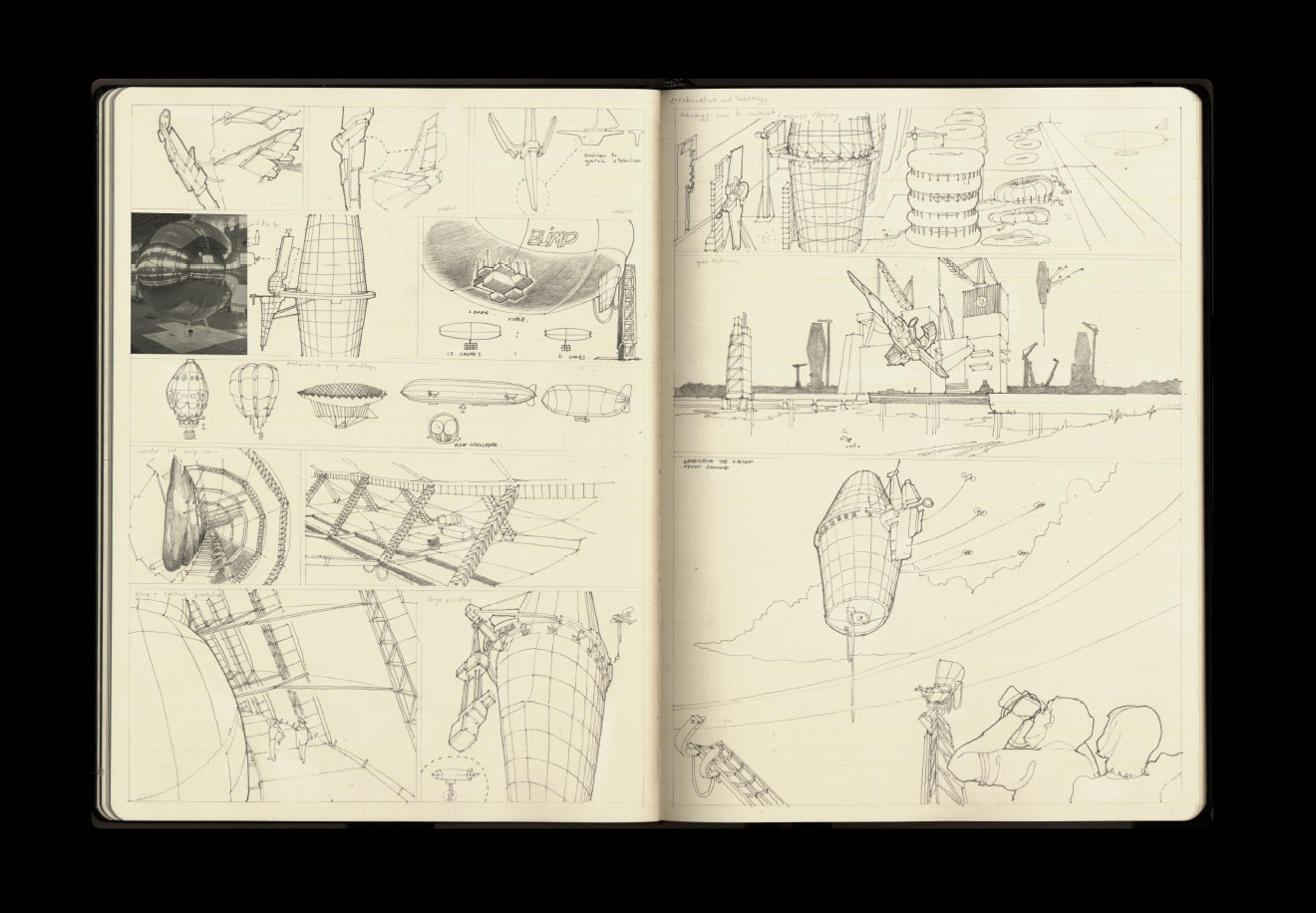

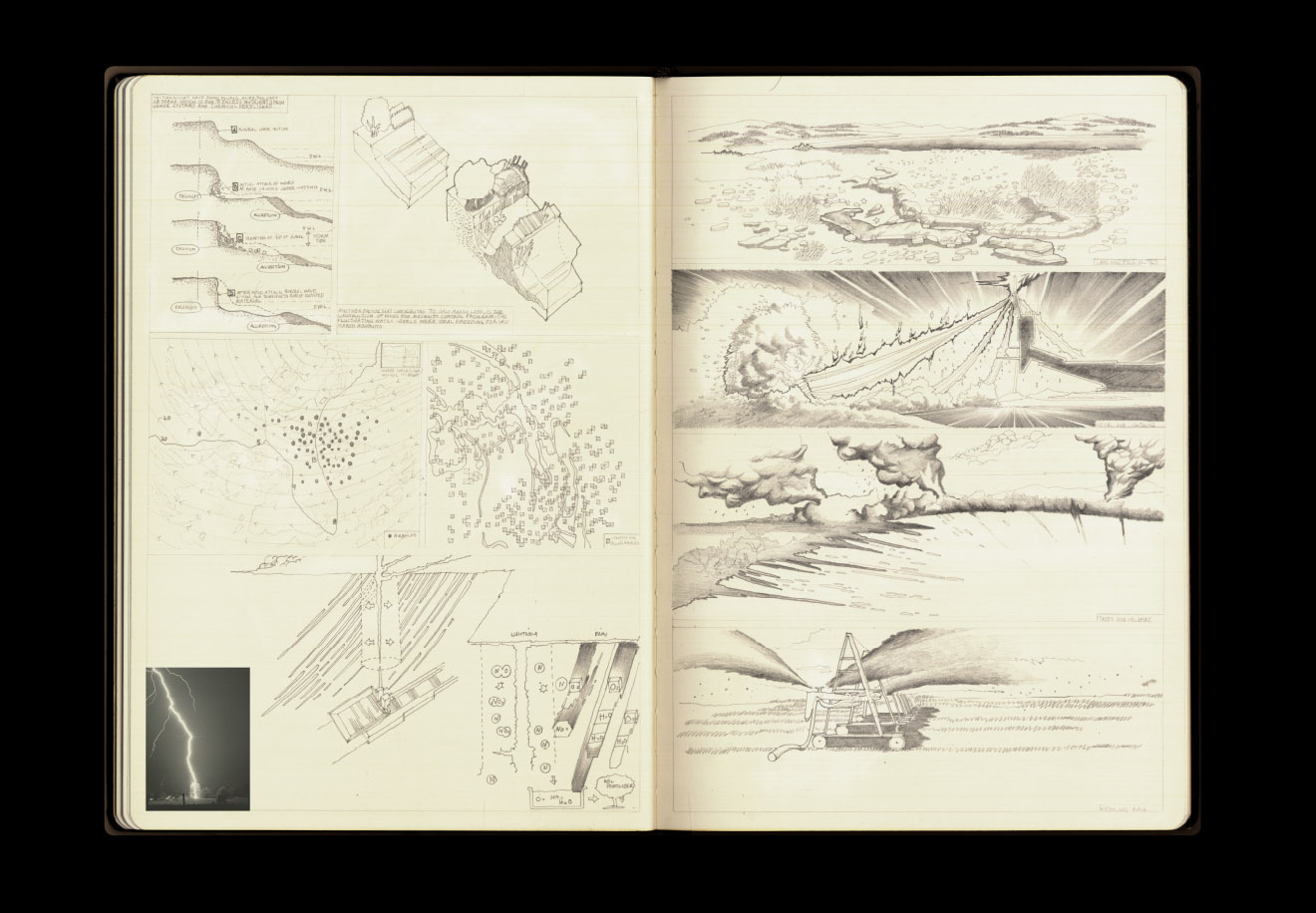

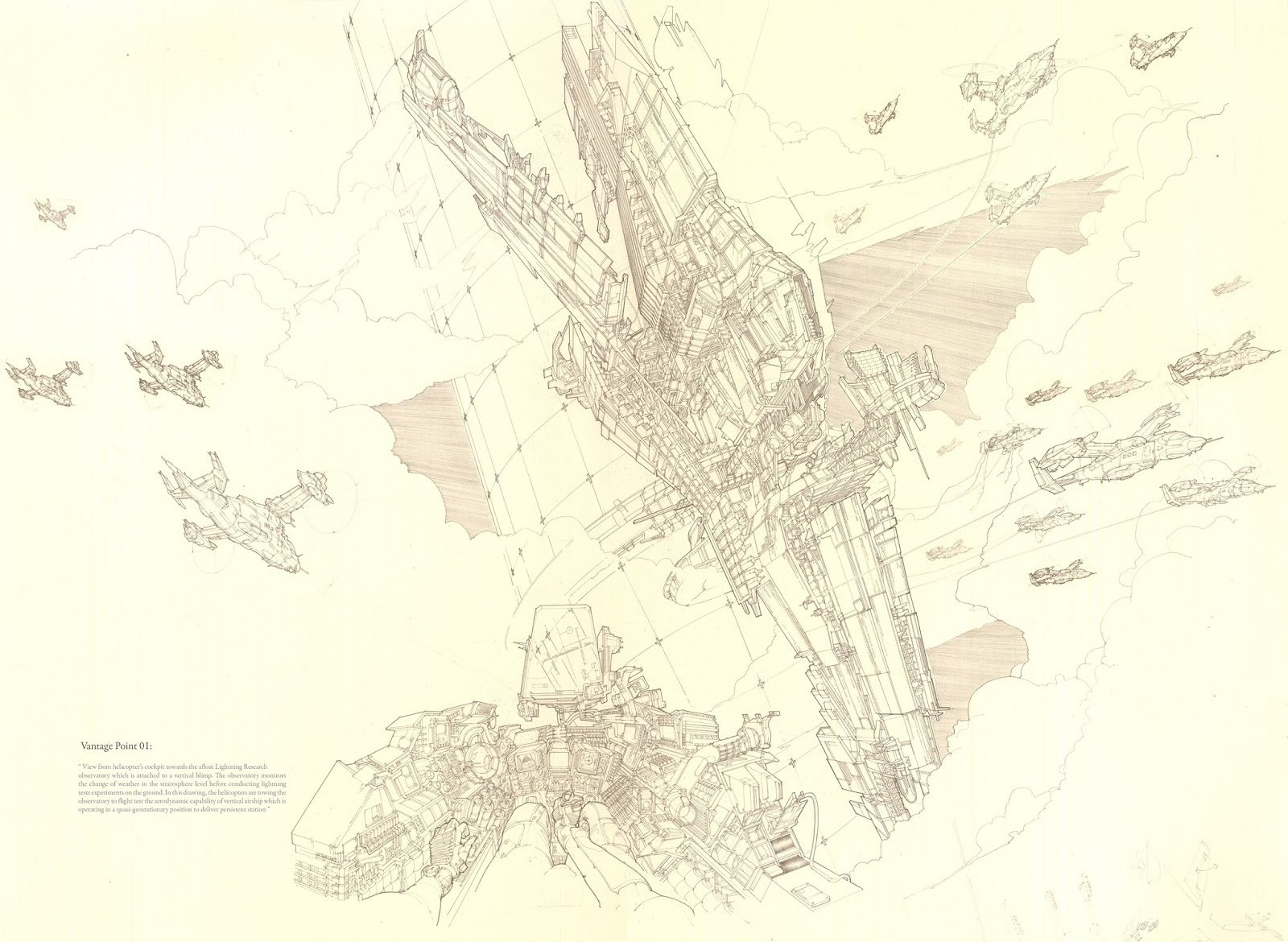

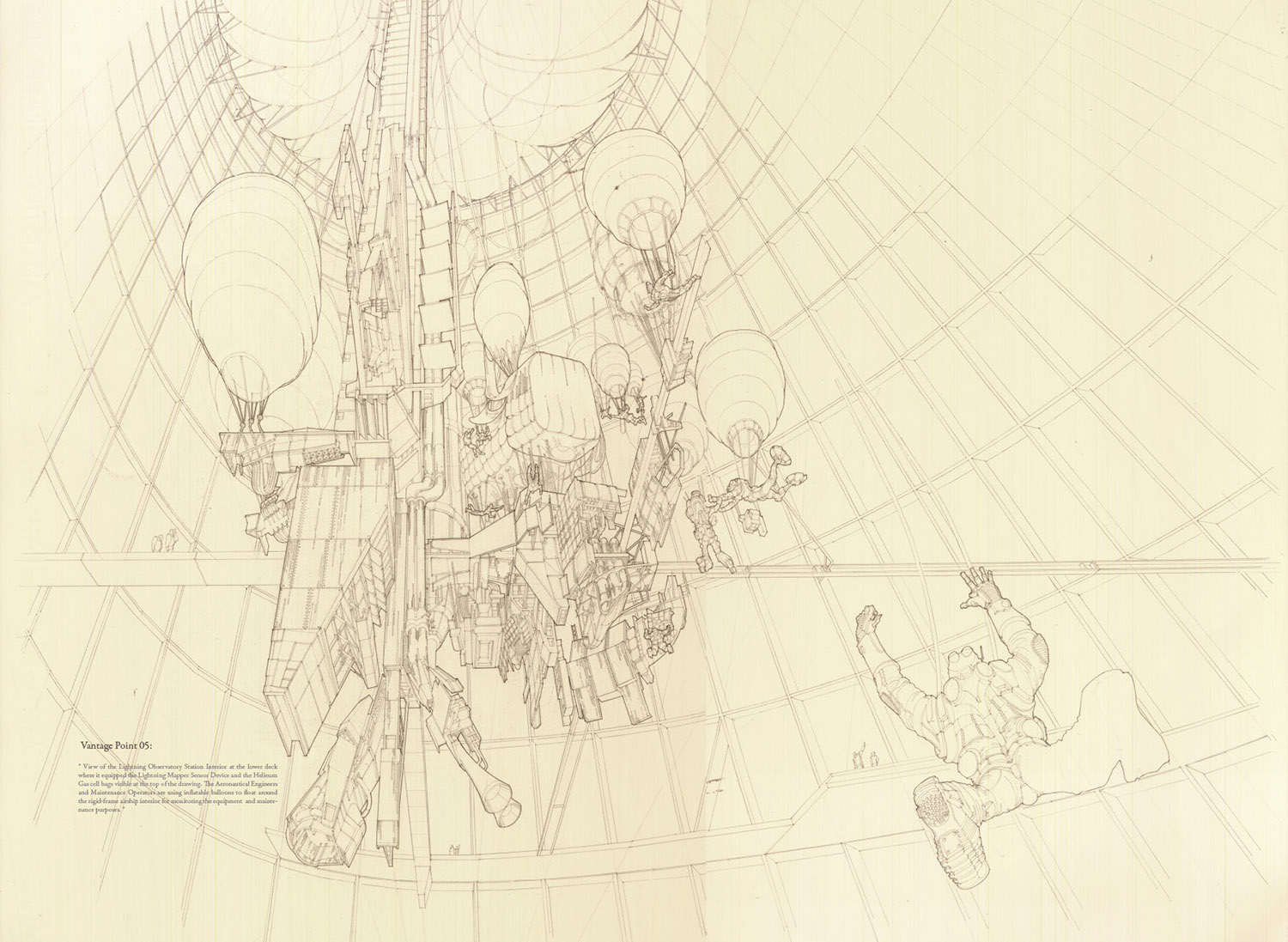

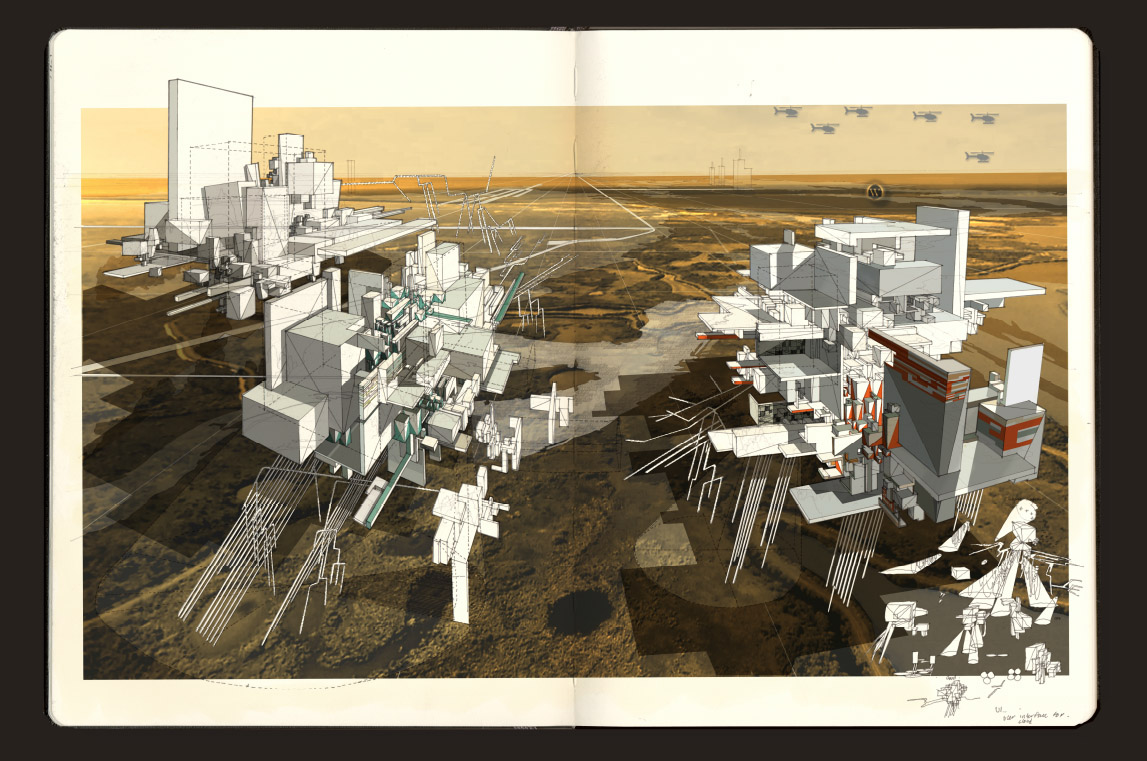

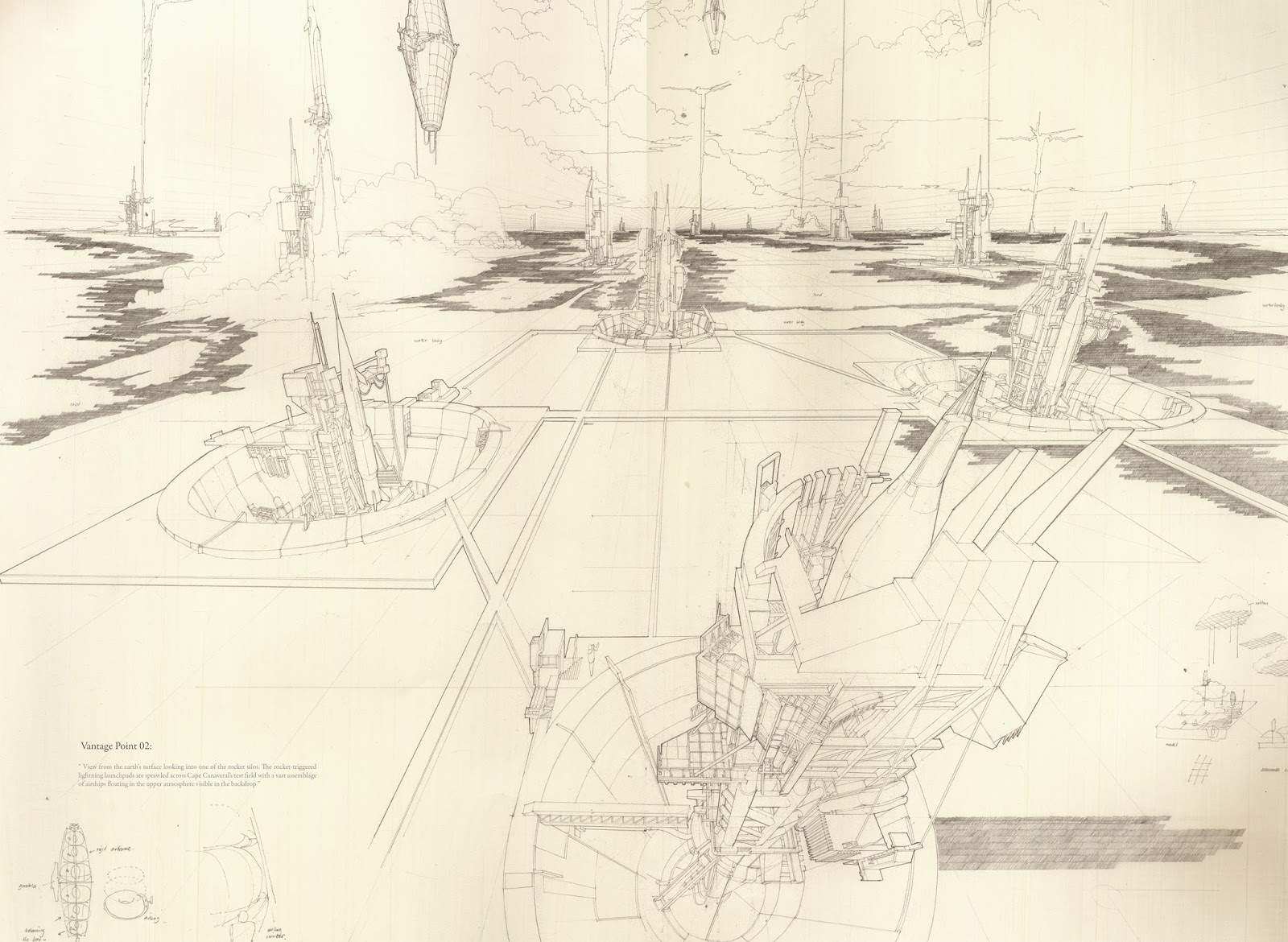

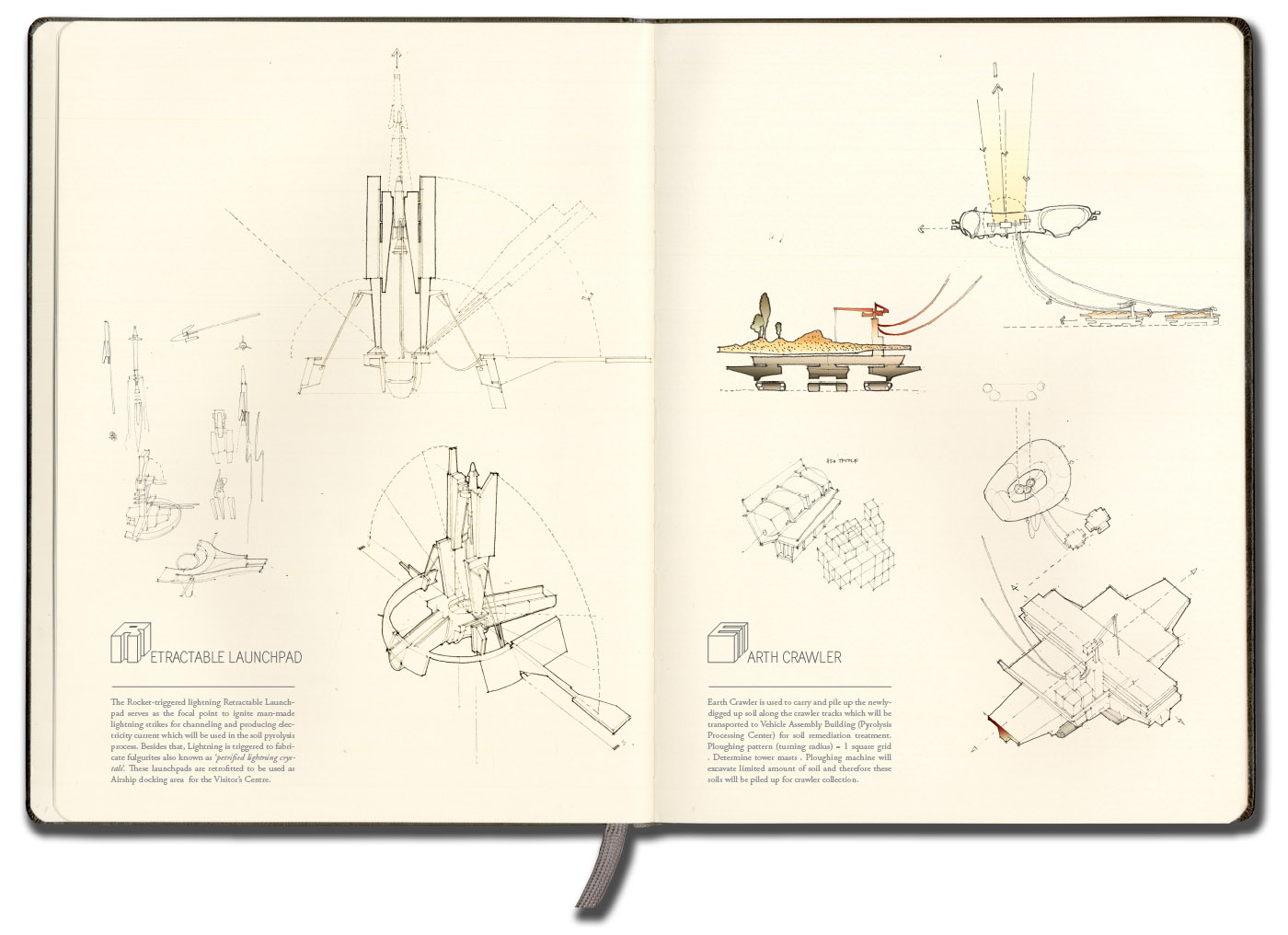

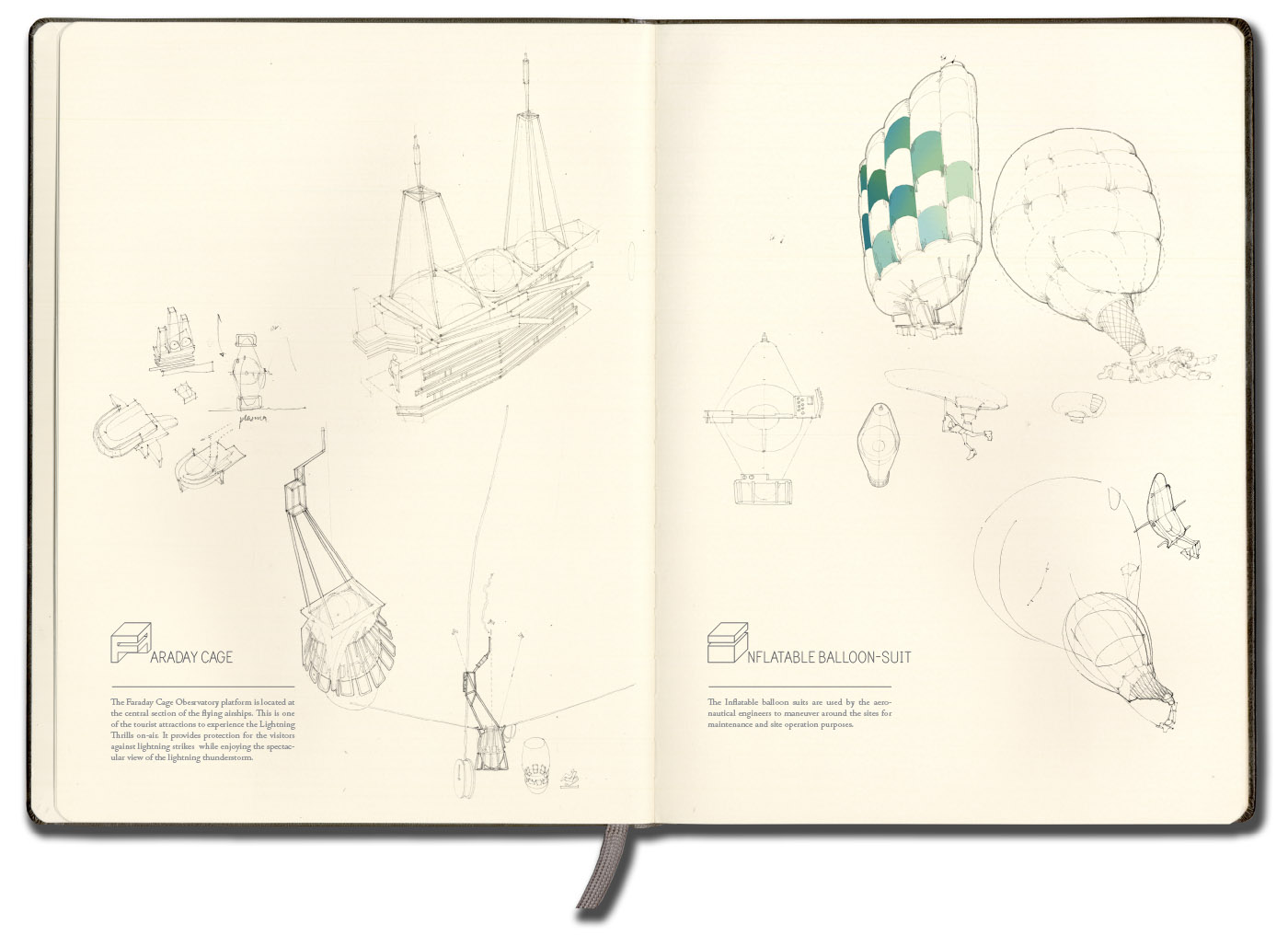

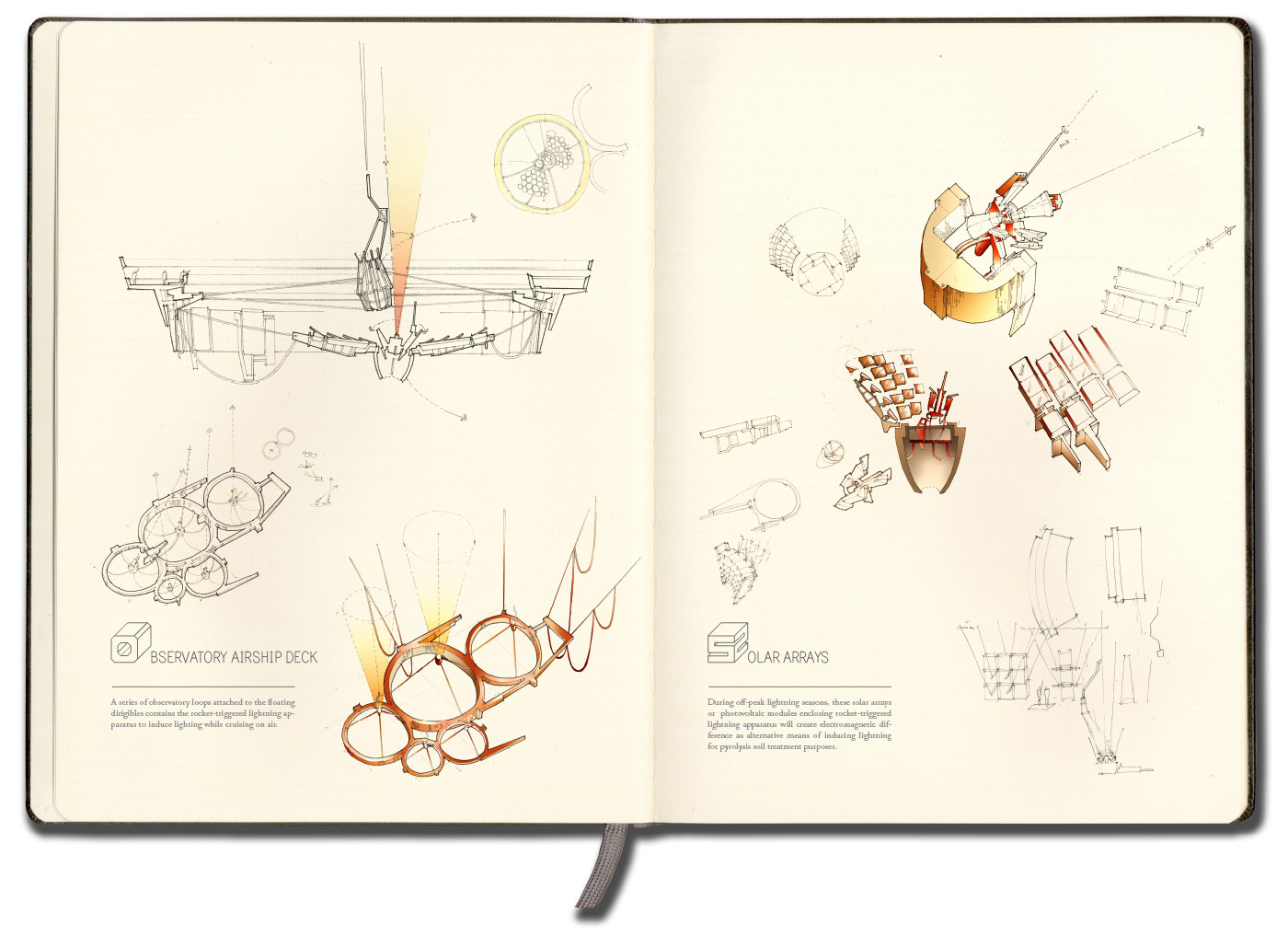

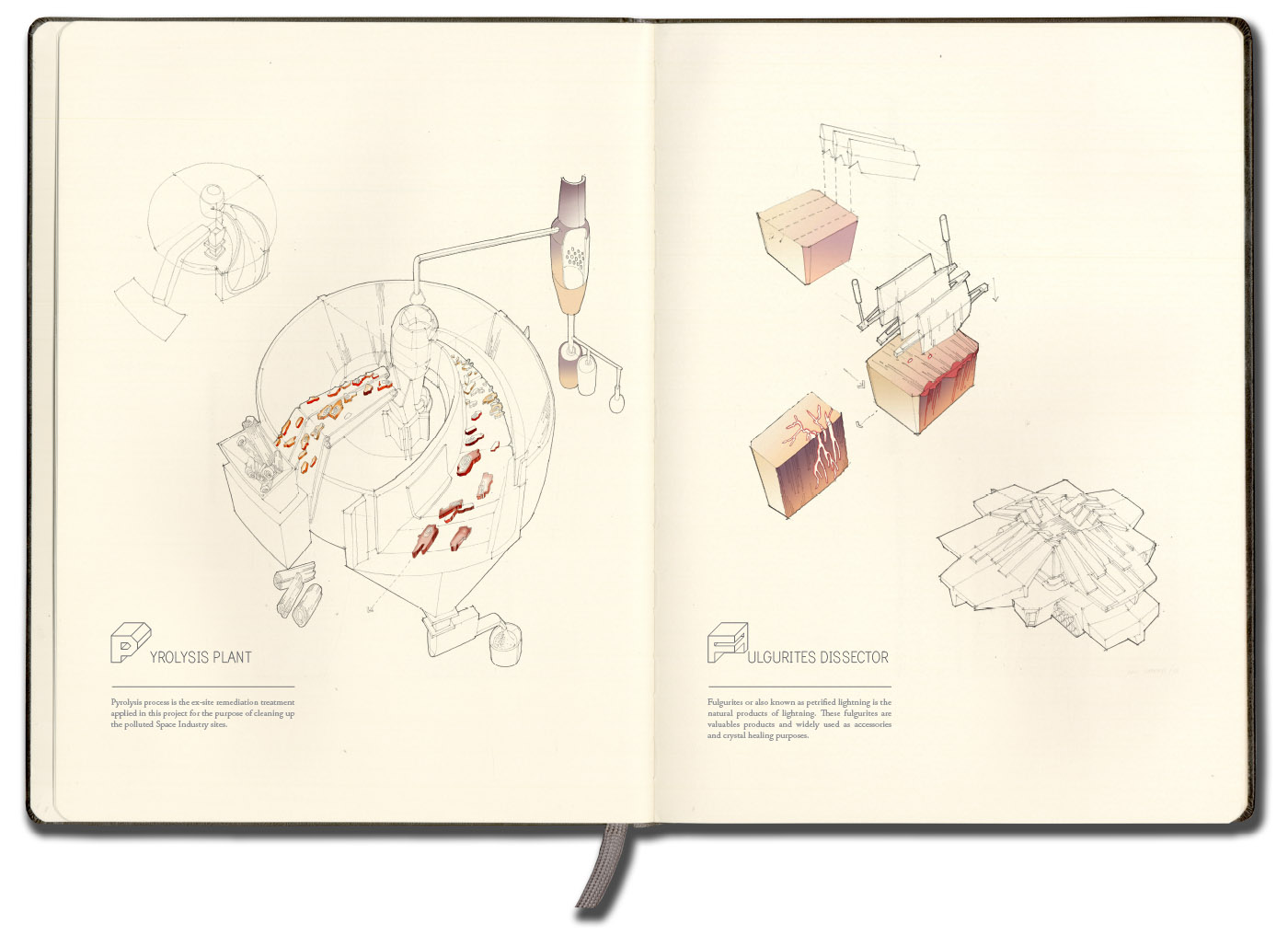

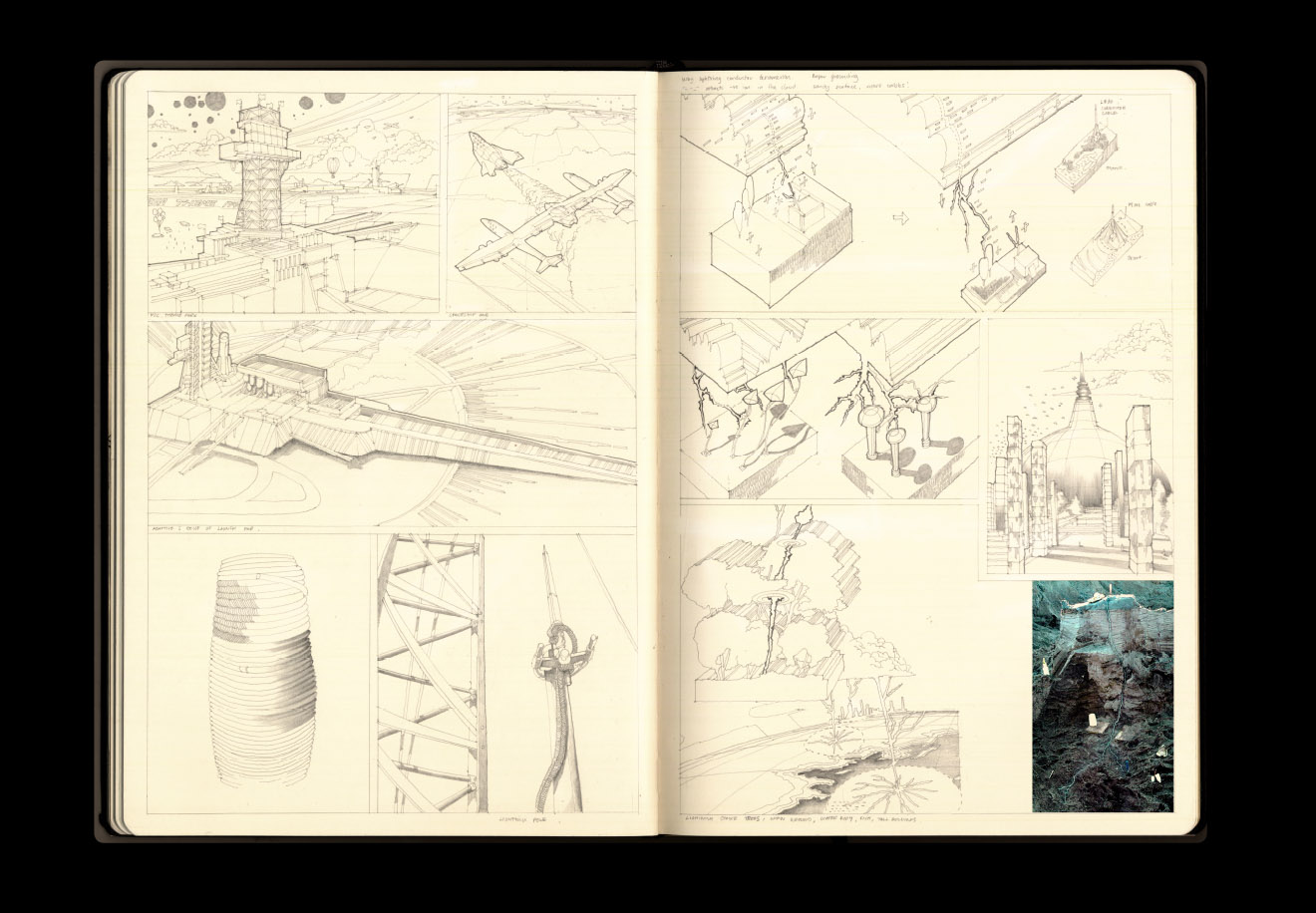

While there were many, many interesting projects resulting from the trip, and from the Unit in general, there is one that I thought I'd post here, by student Farah Aliza Badaruddin, particularly for the quality of its drawings.

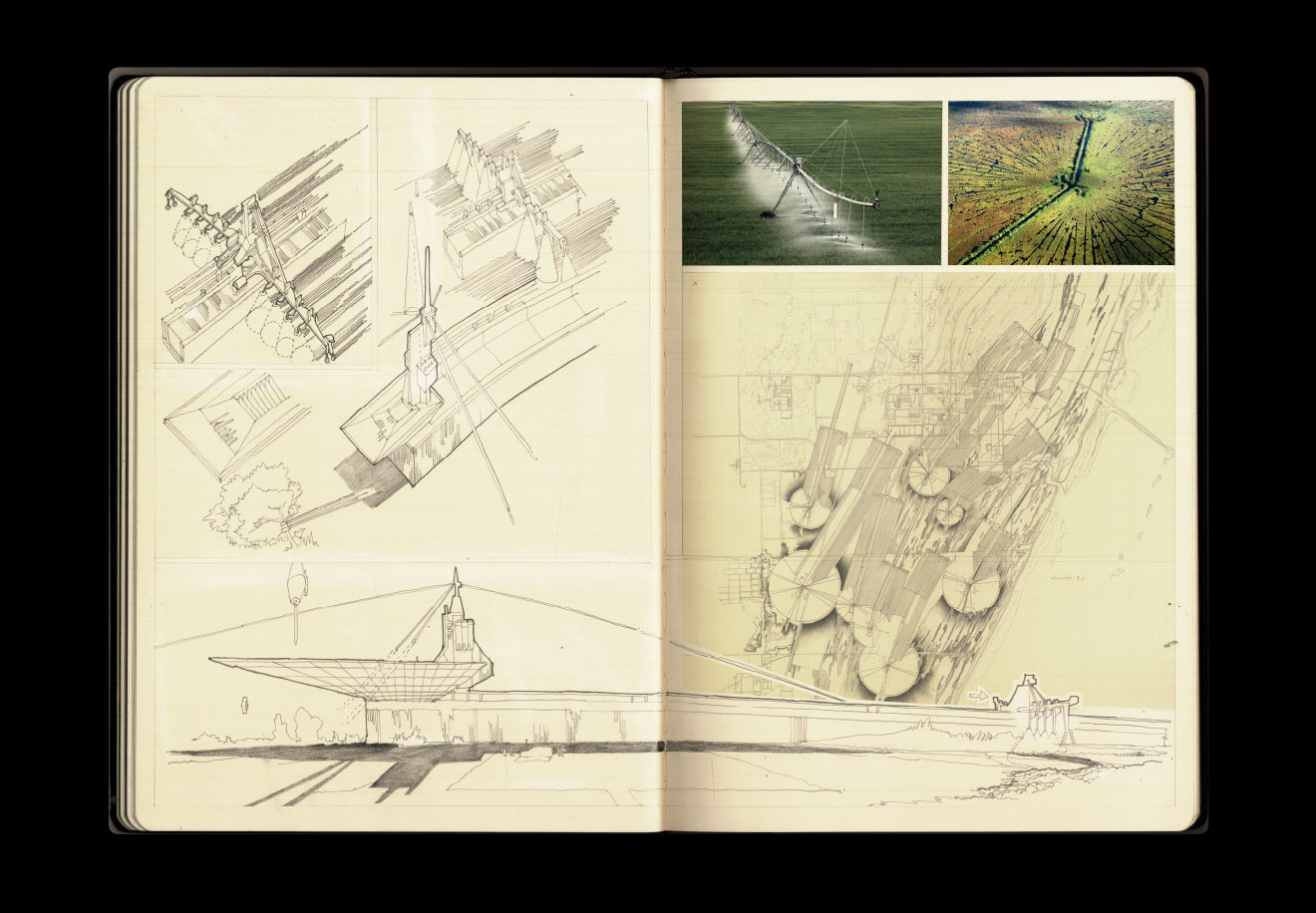

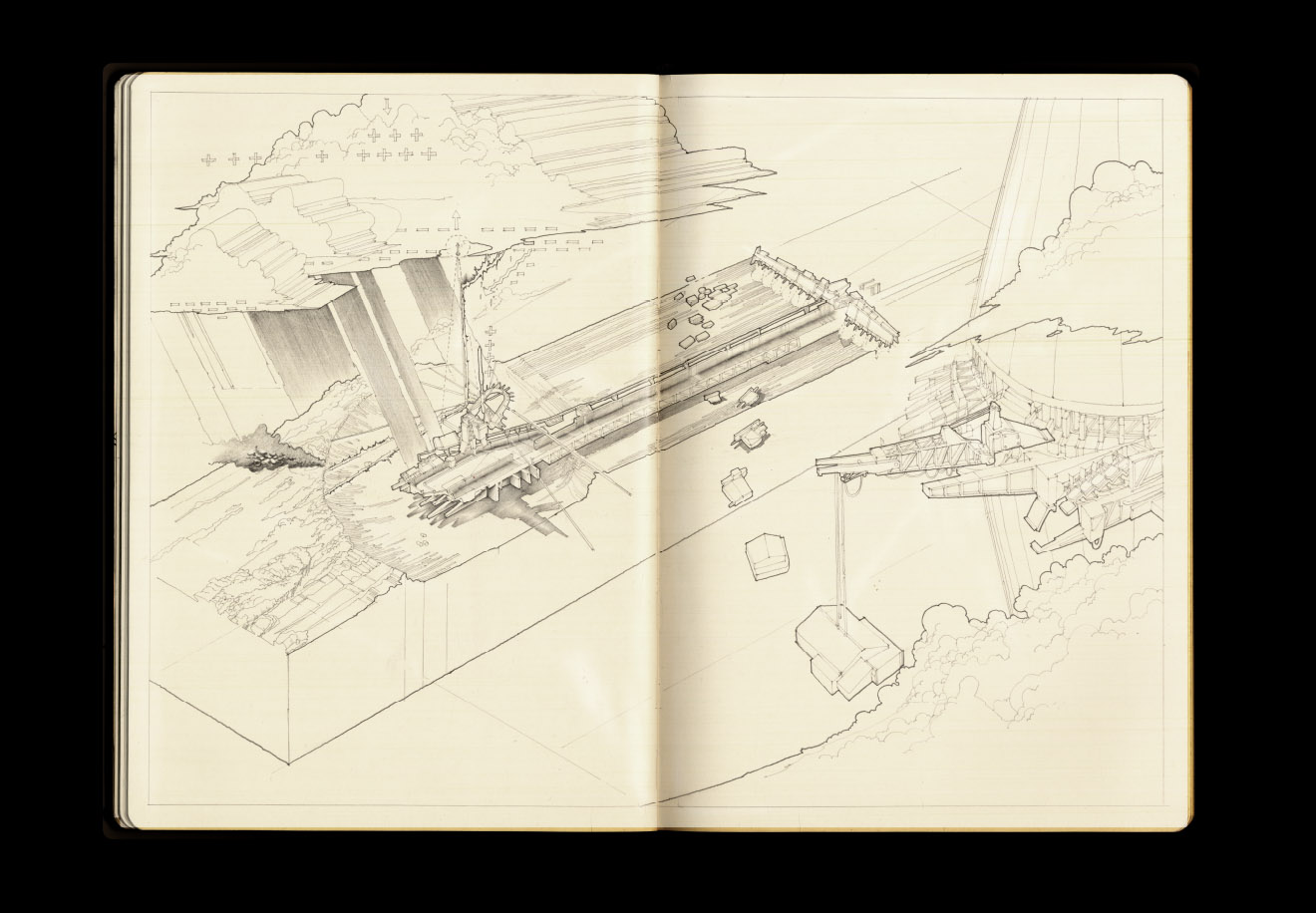

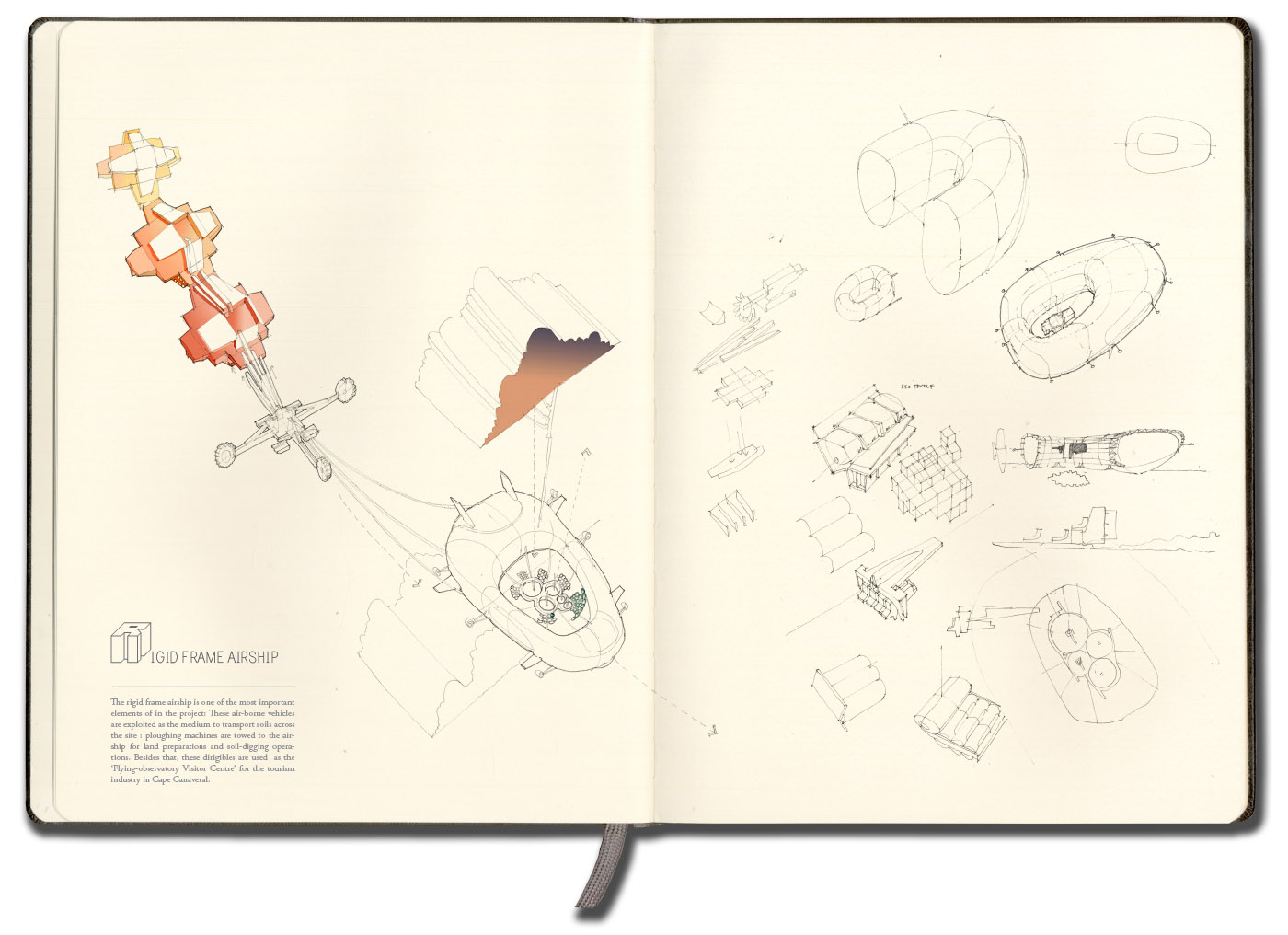

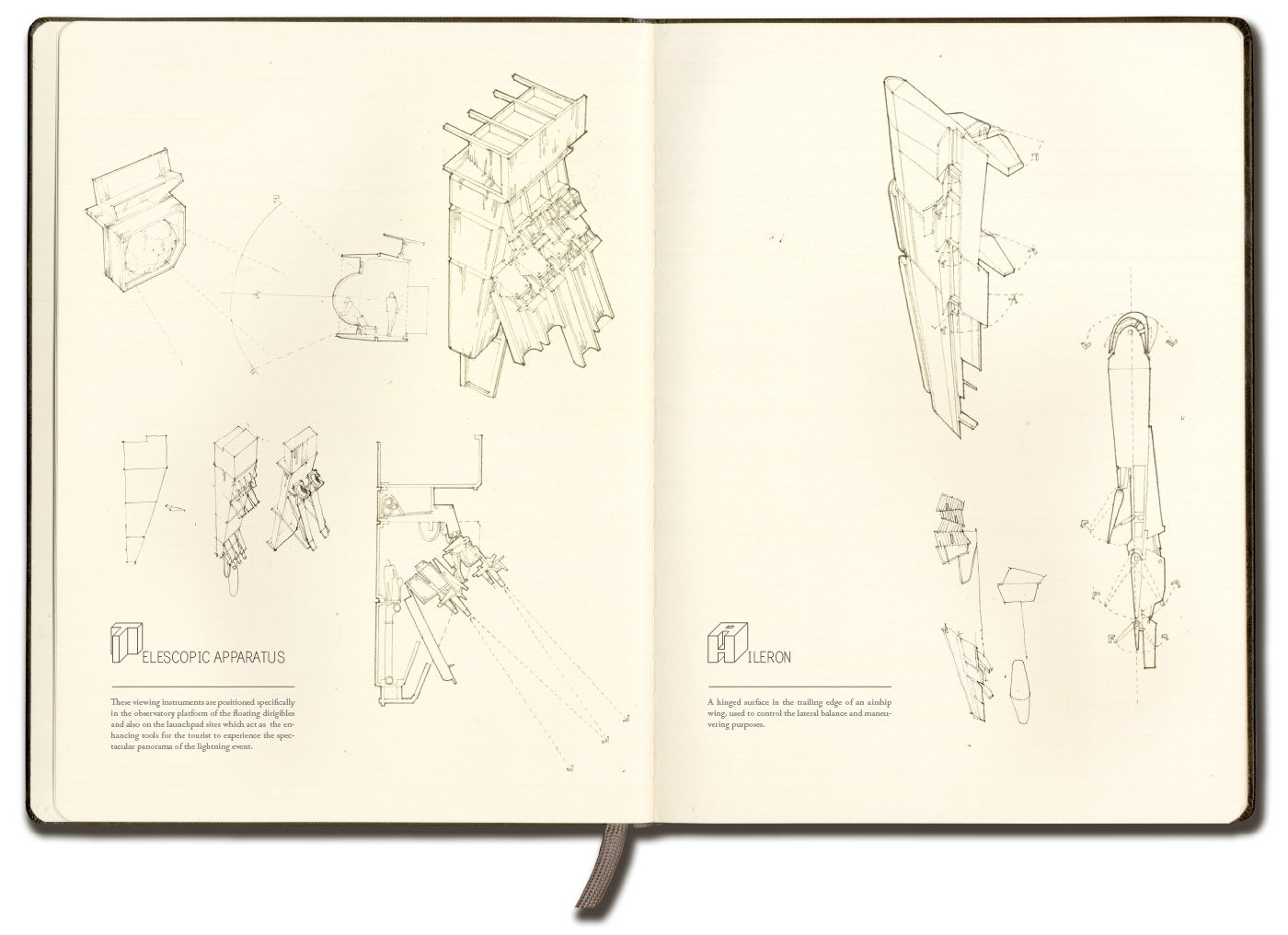

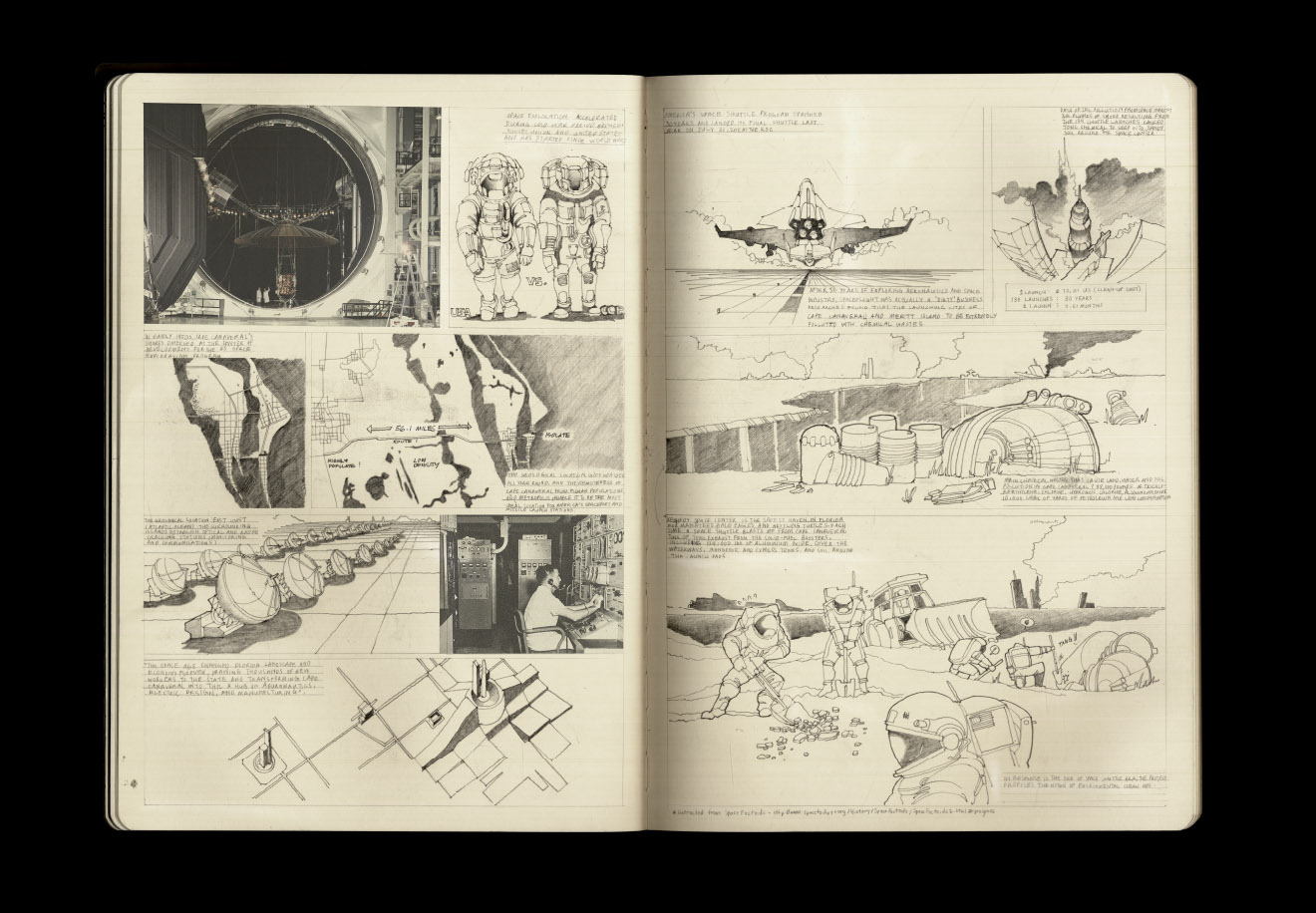

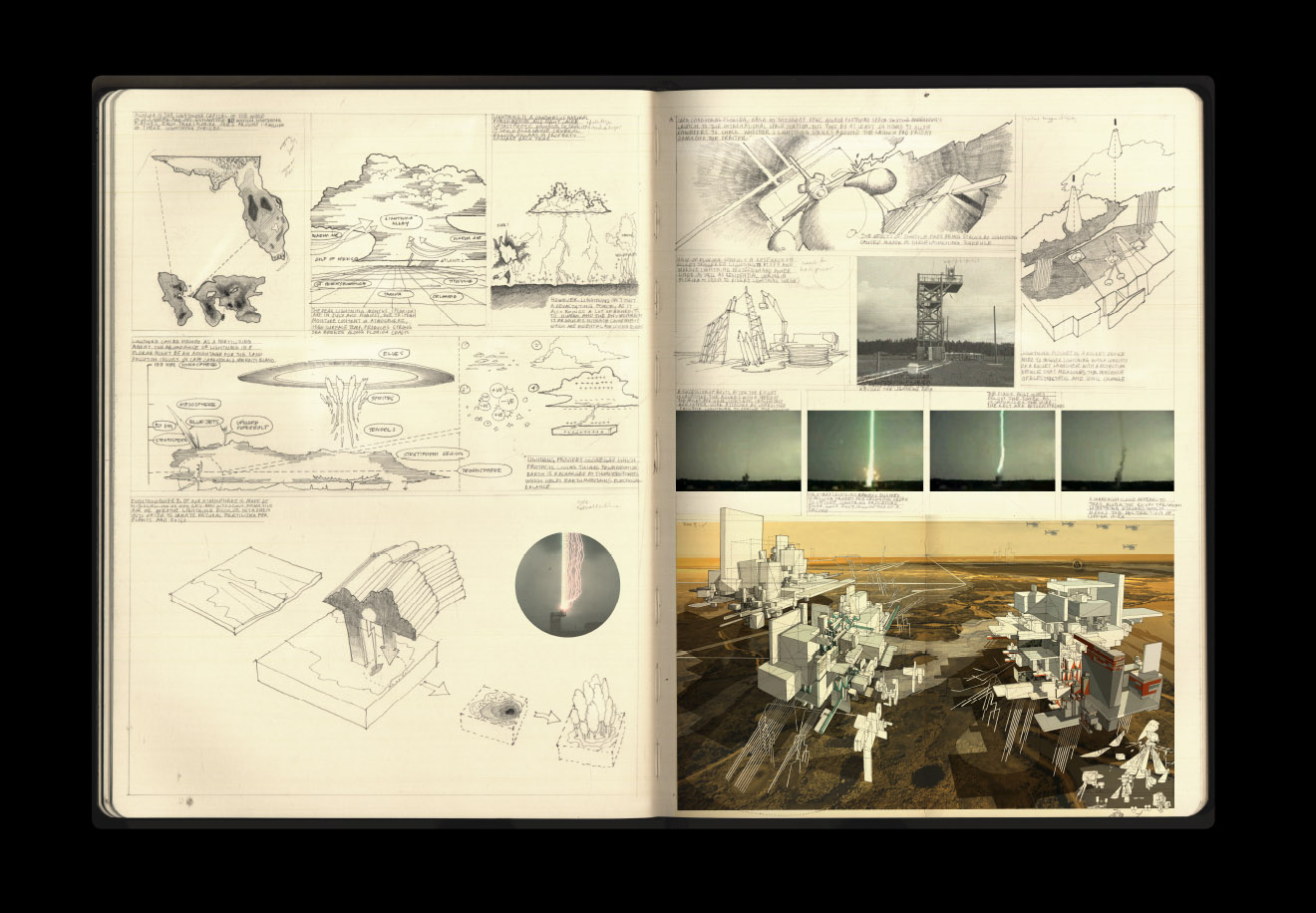

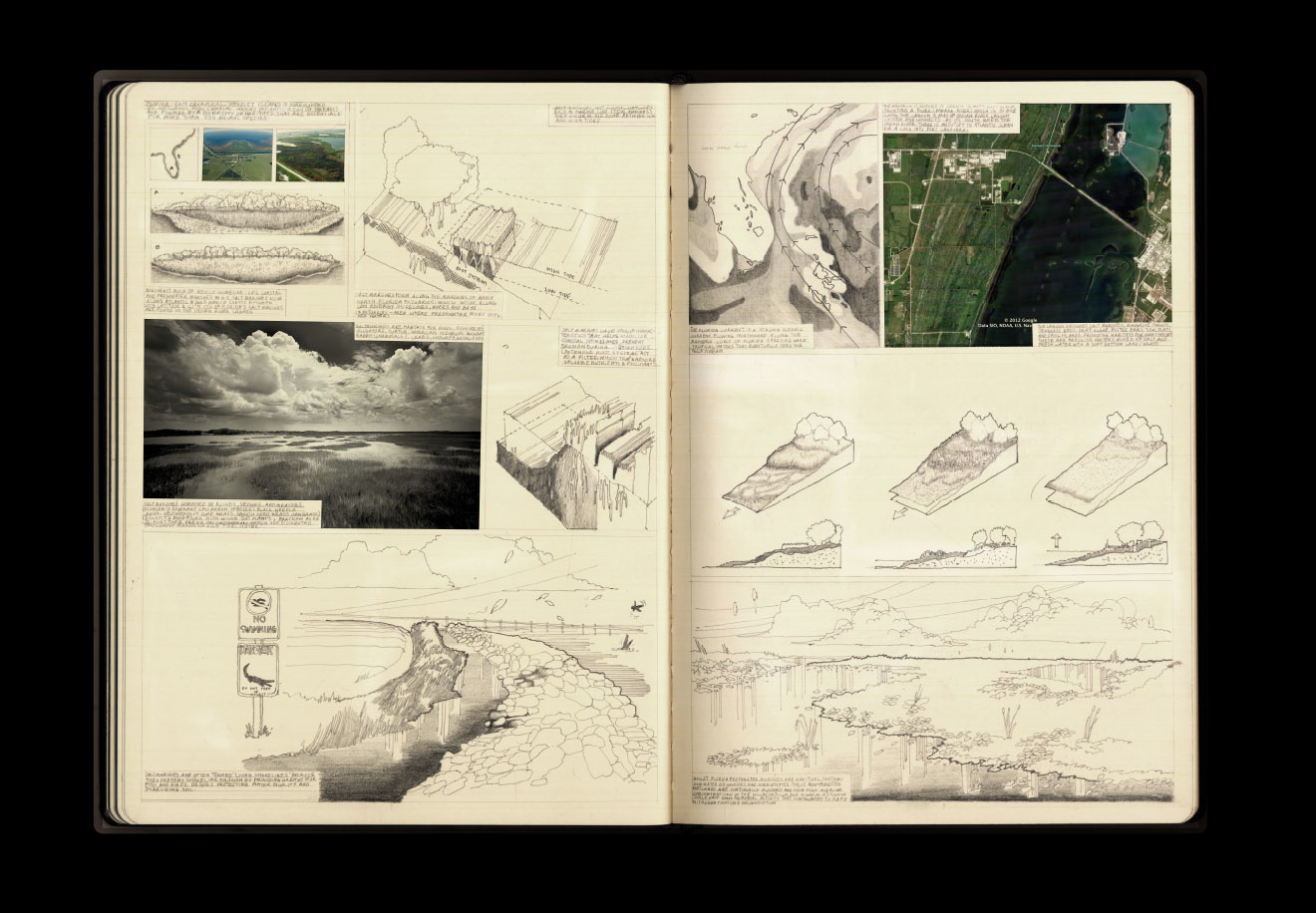

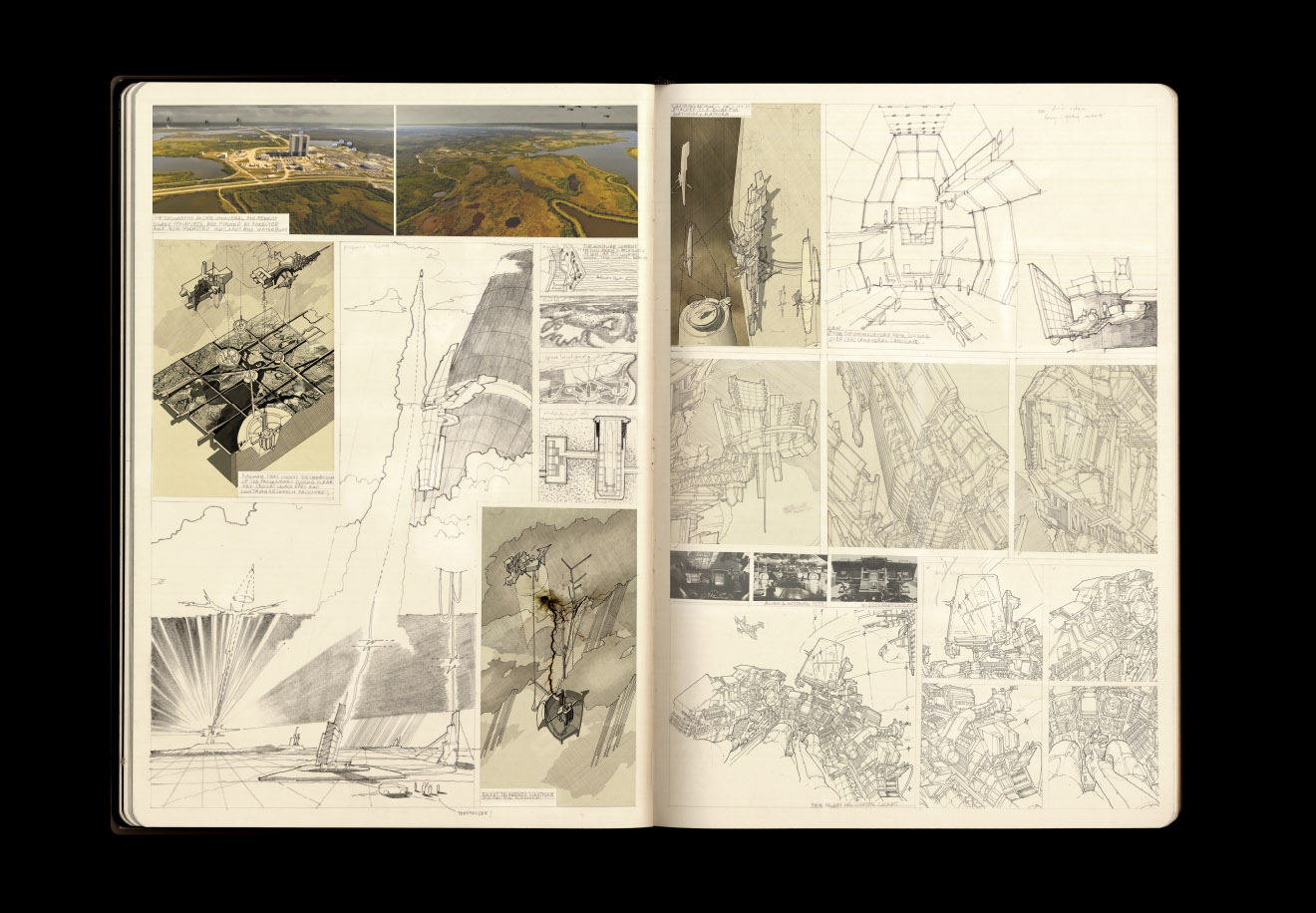

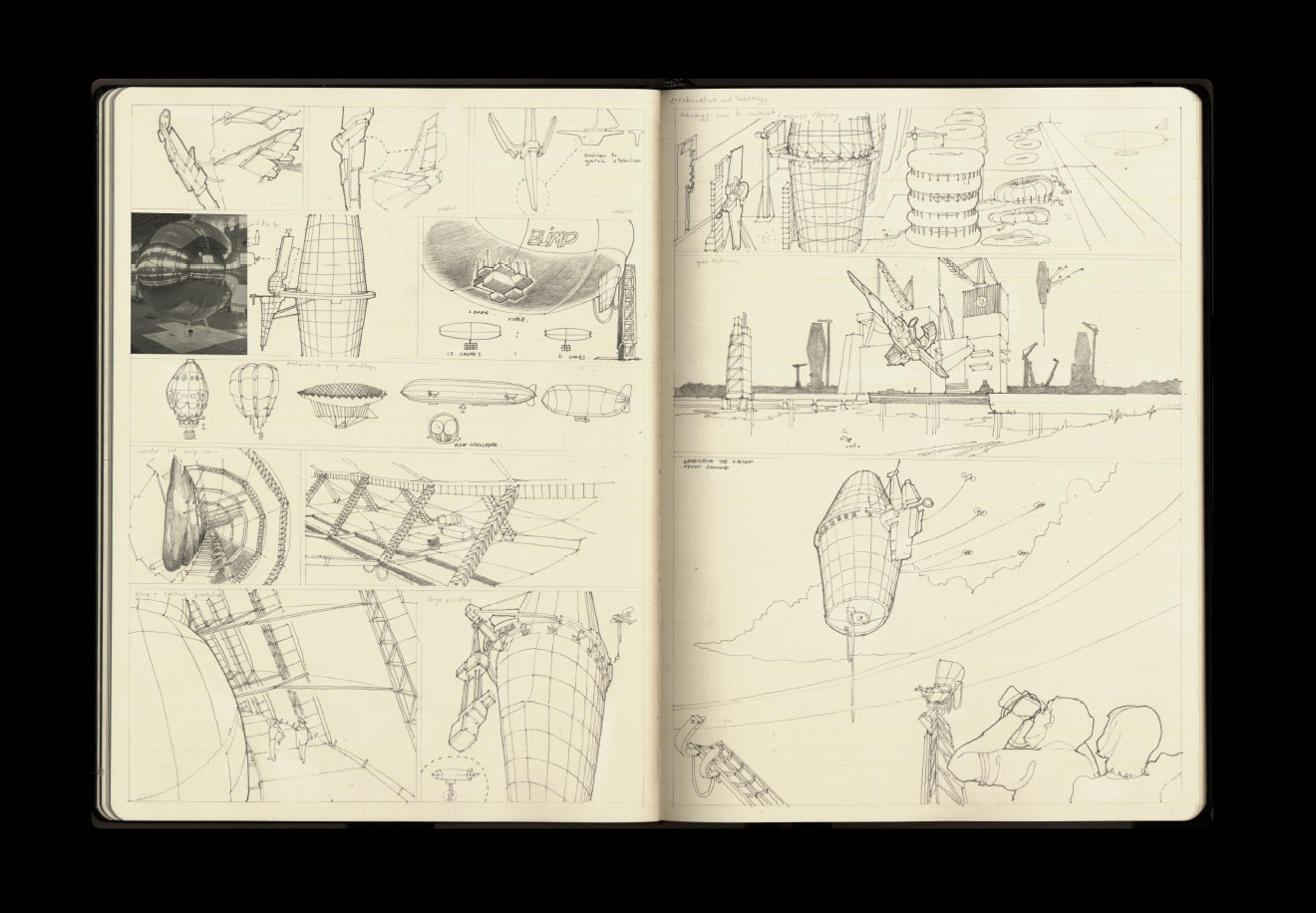

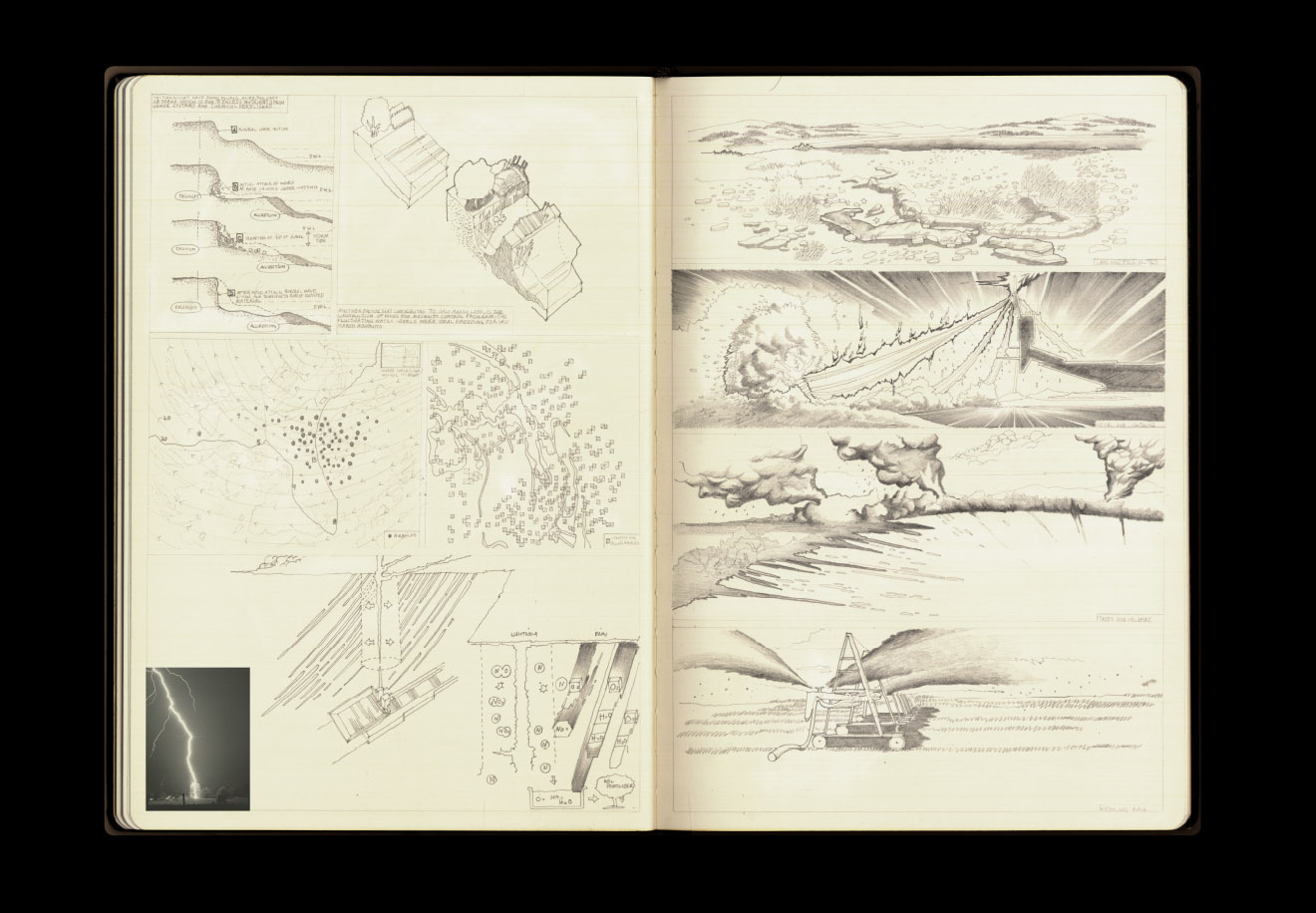

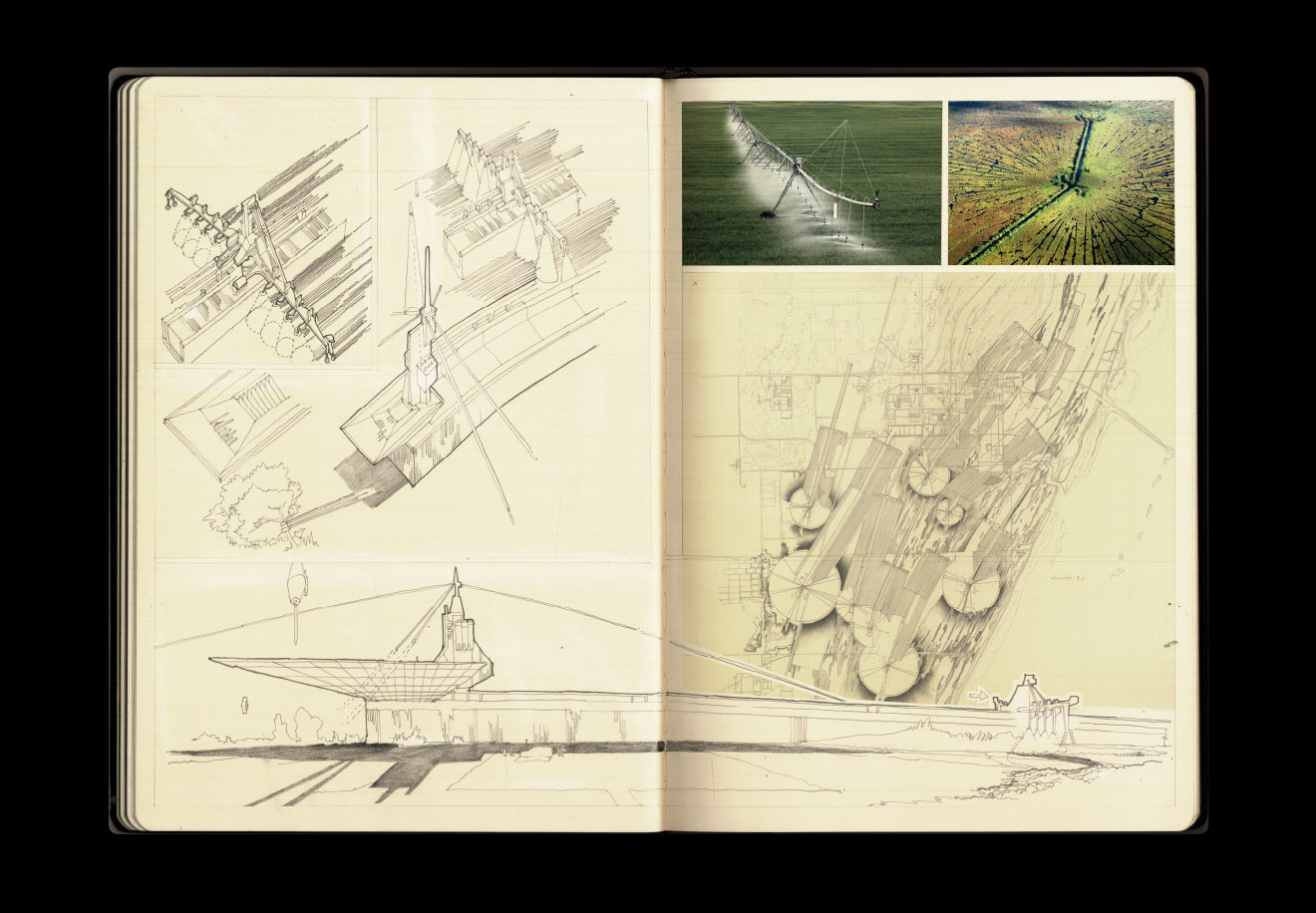

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

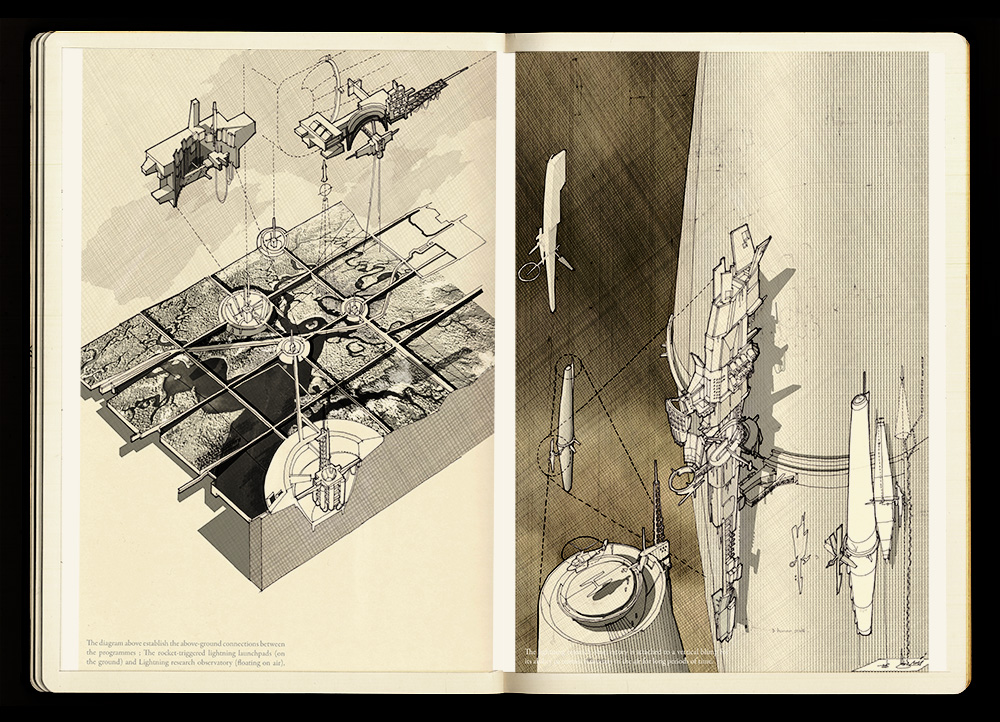

Badaruddin's project explored the large-scale architectural implications of applying radical weather technologies to the task of landscape remediation, asking specifically if Cape Canaveral's highly contaminated ground water—polluted by a "viscous toxic goo" made from tens of thousands of pounds of rocket fuels, chemical plumes, solvents, and other industrial waste products over the decades—could be decontaminated through pyrolysis, using guided and controlled bursts of lightning.

In her own words, Badaruddin explains that the would test "the idea that lightning can be harnessed on-site to pyrolyse highly contaminated groundwater as an approach to remediate the polluted site."

These controlled and repetitive lightning strikes would also, in turn, help fertilize the soil, producing a kind of bio-electro-agricultural event of truly cosmic (or at least Miller-Ureyan) proportions.

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida Lightning Research Group].

Her maps of the area—which she presents as if drawn in a Moleskine notebook—show the terrestrial borders of the proposal (although volumetric maps of the sky, showing the project's fully three-dimensional engagement with regional weather systems, would have been an equally, if not more, effective way of showing the project's spatial boundaries).

This raises the awesome question of how you should most accurately represent an architectural project whose central goal is to wield electrical influence on the atmosphere around it.

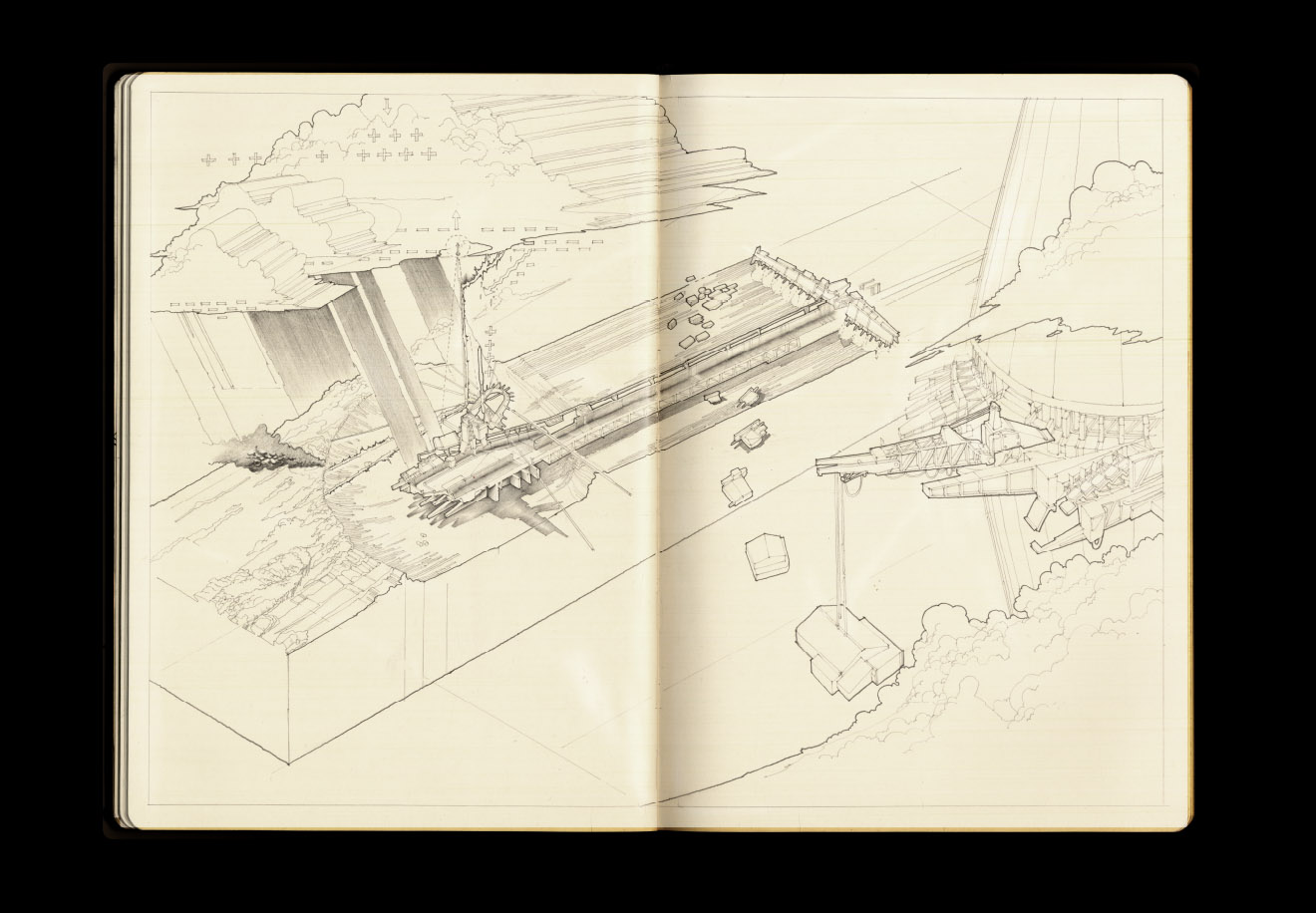

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

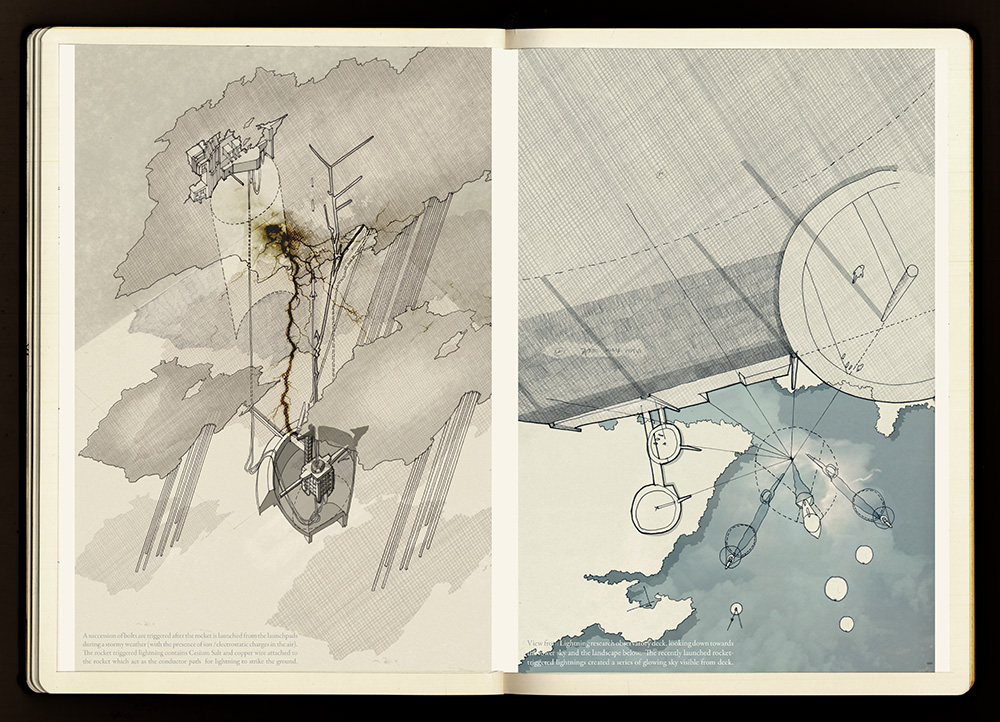

In short, her design proposes a new infrastructure of "rocket-triggered lightning technology," assisted and supervised by a peripheral network of dirigibles—floating airships that "surround the site and serve as the observatory platform for a proposed lightning visitor centre and the weather research center."

The former was directly inspired by real-world lightning research equipment found at the University of Florida's Lightning Research Group.

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida's Lightning Research Group].

Badaruddin's own rocket triggers would be used both to attract and "to provide direct lightning strikes to the proposed sites," thus pyrolizing the landscape and purifying both ground water and soil.

[Image: Aerial collage view of the lightning farm, by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

The result would be a lightning farm, a titanic landscape tuned to the sky, flashing with controlled lightning strikes as the ground conditions are gradually remediated—an unmoving, nearly permanent, artificial electrical storm like something out of Norse mythology, cleansing the earth of toxic chemicals and preparing the site for future reuse.

[Image: Collage of the lightning farm, by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

I should say that my own interest in these kinds of proposals is less in their future workability and more in what it means to see a technology taken out of context, picked apart for its spatial implications, and then re-scaled and transformed into a speculative work of landscape architecture. The value, in other words, is in re-thinking existing technologies by placing them at unexpected scales in unexpected conditions, simultaneously extracting an architectural proposal from that and perhaps catalyzing innovative new ways for the original technology itself to be redeveloped or used.

[Image: Farah Aliza Badaruddin].

It's not a question of whether or not something can be immediately realized or built; it's a question of how open-ended, fictional design proposals can change the way someone thinks about an entire field or class of technologies.

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

But I'll let Badaruddin's own extraordinary visual skills tell the story. Most if not all of these images can be seen in a much larger size if you open the images in their own windows; they're well worth a closer look—

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

—including what amount to a short graphic novel telling the story of her proposed controlled-lightning landscape-decontamination facility.

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

All in all, whether or not architecturally-controlled lightning storms will ever purify the land and water of south Florida, it's a wonderfully realized and highly imaginative project, and I hope Badaruddin finds more opportunities, post-Bartlett, to showcase and develop her skills.

Friday, May 24. 2013

Via BLDGBLOG

-----

de noreply@blogger.com (Geoff Manaugh)

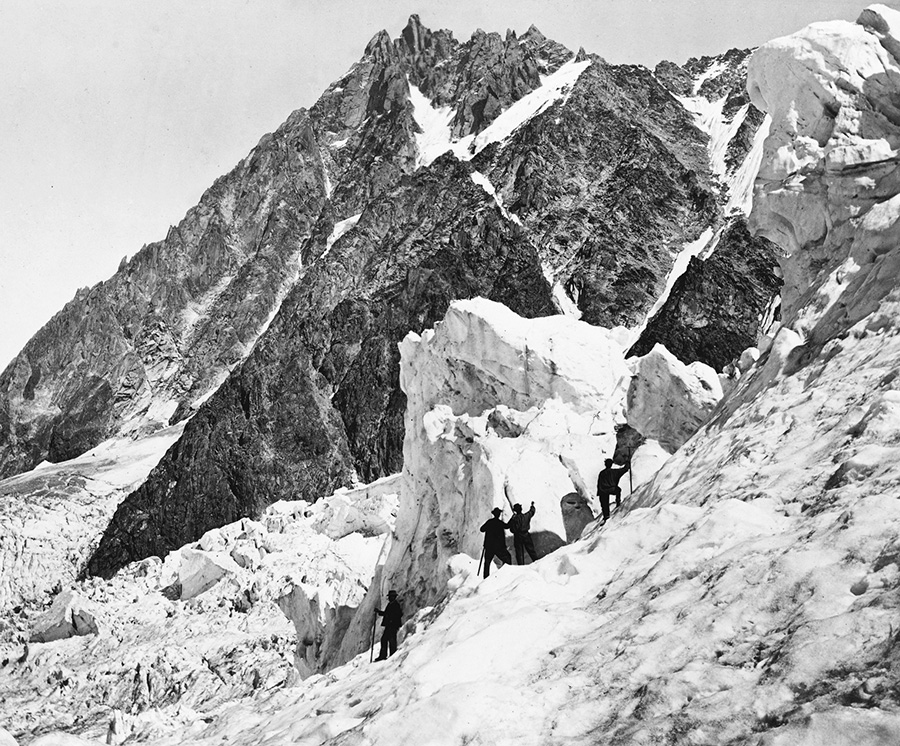

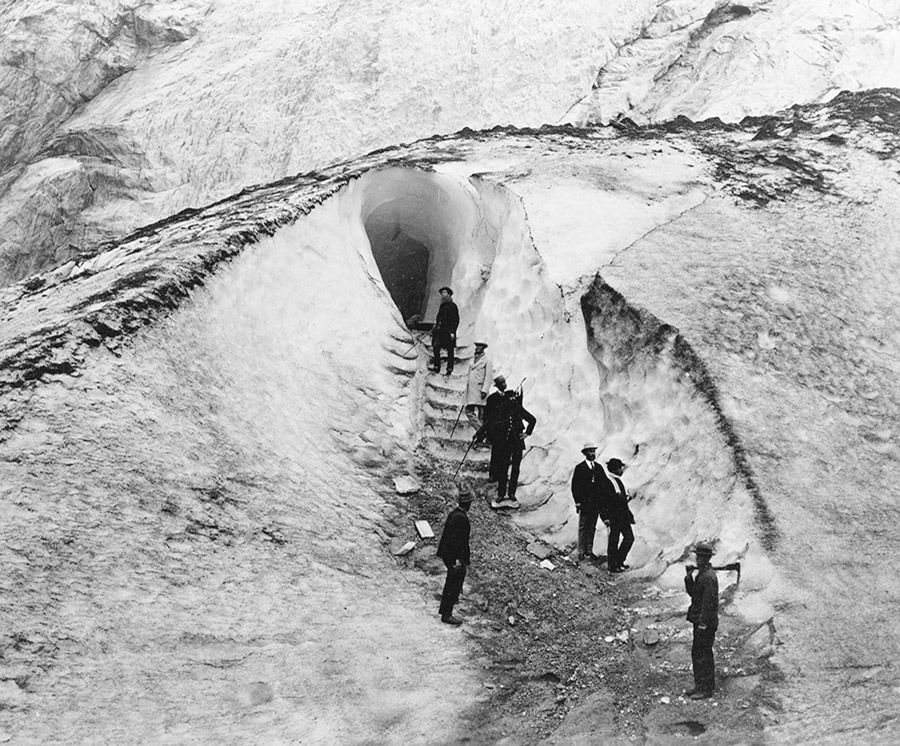

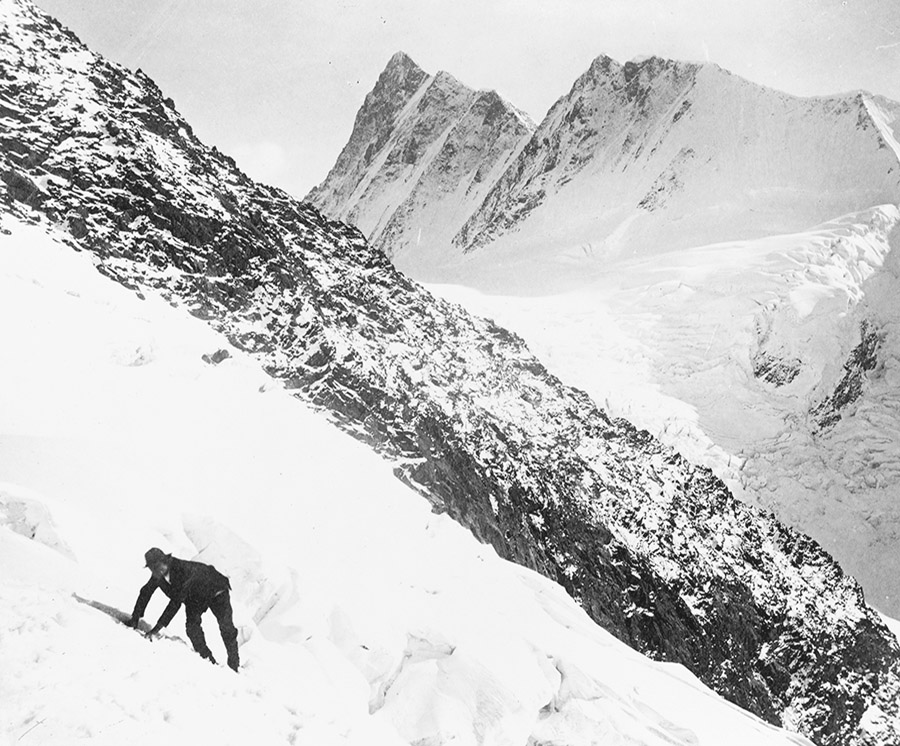

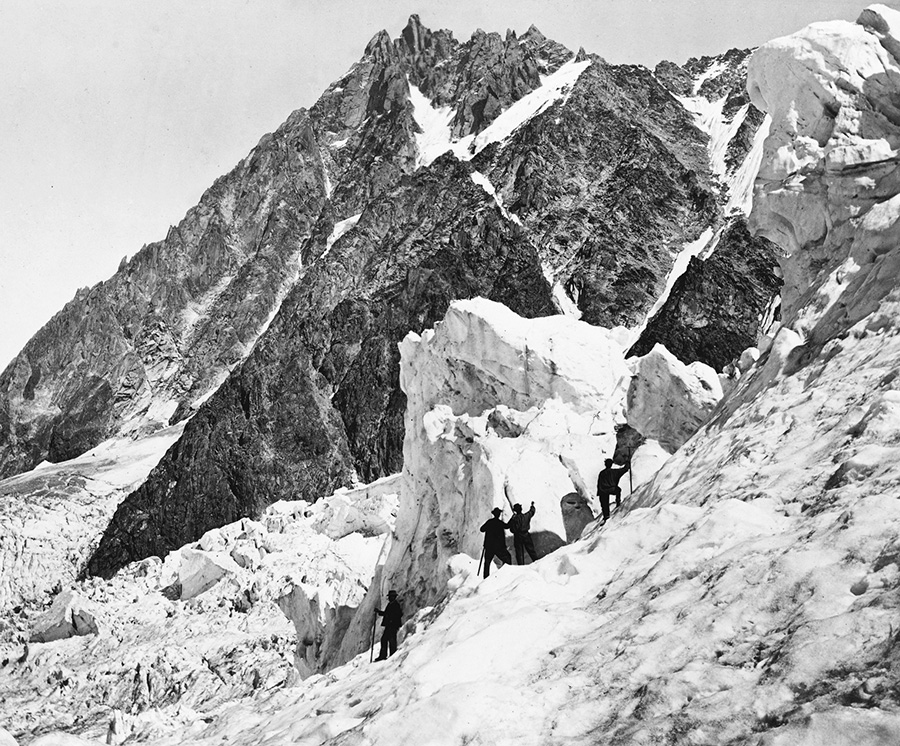

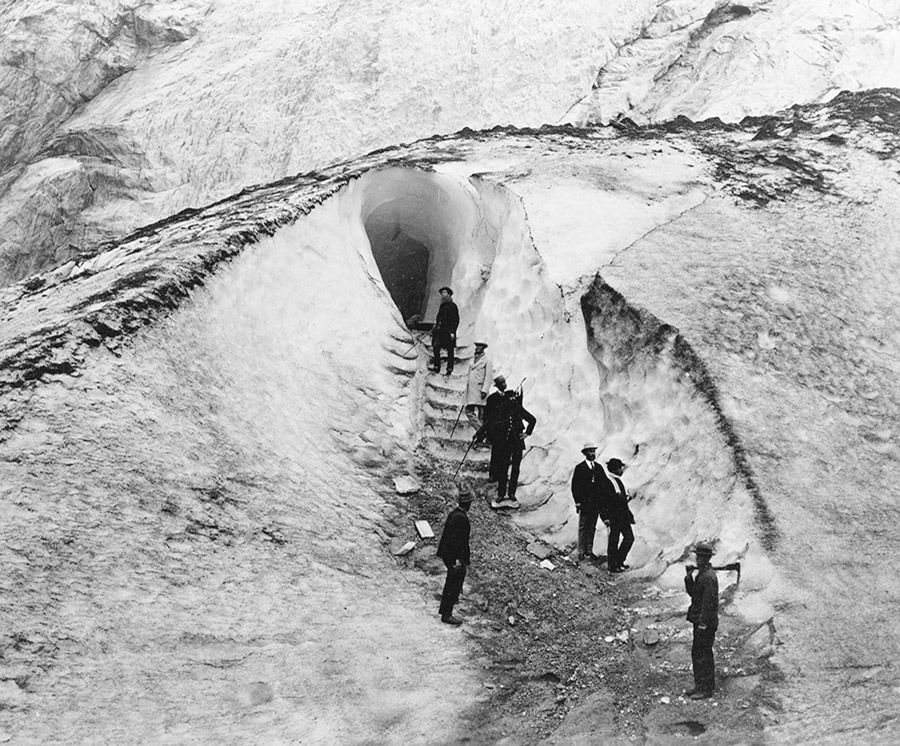

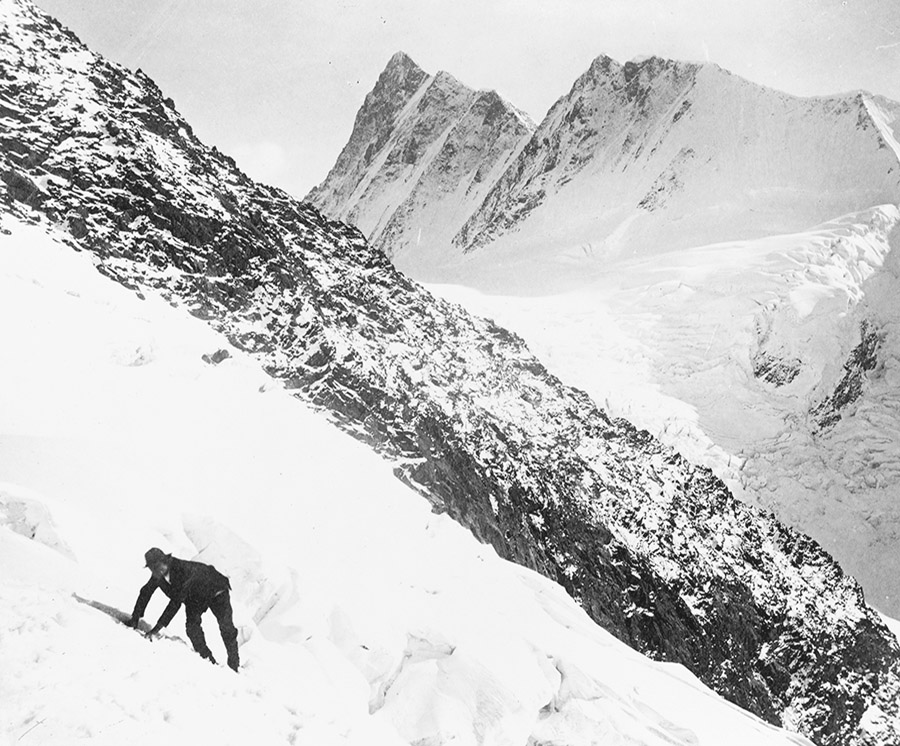

[Image: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division]. [Image: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division].

After posting several of these images in our recent Venue interview with outdoor equipment strategist Scott McGuire—easily one of my favorite interviews of late, touching on everything from civilianized military gear used in everyday hiking to REI-augmented wilderness camp sites as the true heirs of Archigram—I was so taken by their weirdly haunting views of humans wandering through extreme landscapes, dressed in 19th-century suits and top hats, carrying canes, that I thought I'd post a larger selection.

[Images: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division]. [Images: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division].

Middle class gentlemen and ladies in hooped skirts walk into ice caves and step gingerly across the cracked, abyssal surfaces of old mountain glaciers, pointing up at things they don't understand.

[Image: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division]. [Image: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division].

At times, these feel almost like photos from some as-yet-unwritten Gothic horror story, perhaps a 19th-century Swiss prequel to John Carpenter's The Thing, in which some purely accidental sequences of photos—

[Images: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division]. [Images: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division].

—imply a narrative of genial discovery, focused exploration, and eventual solo flight down the mountainside in terror.

In fact, I could easily imagine an Alpine variation on Michelle Paver's memorably unsettling Arctic ghost novel Dark Matter set in such geologically extravagant landscapes, as humans struggle to survive, both physically and psychologically, in this encounter with an incomprehensibly over-sized landscape millions of years older than they might ever be, naively setting up camp amidst a wilderness that does not want them there.

[Images: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division]. [Images: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division].

But then, at other times, these photos are almost like exaggerated set pieces by artists Kahn & Selesnick, whose work proposes fictional expeditions to otherworldly landscapes, missions to the moon, ancient salt cities, and more, all told through an almost unbelievably elaborate series of props, fake postcards, paintings, photographs, and more.

Like some unrealized backstory for their "Eisbergfreistadt" project, for example, or their "Circular River" expedition, men in wool vests pull one another up abstract glacial forms, as an incredible wooden staircase—if you look closely at the next image—races up the mountainside in the middle of nowhere.

[Image: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division]. [Image: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division].

After a point, these scenes are Chaplinesque and ridiculous, like turn-of-the-century bankers who got lost on a glacier in a Modernist play.

[Image: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division]. [Image: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division].

In any case, these all come courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, where substantially higher-res versions of each photo are available; but don't miss the additional photos in the interview with Scott McGuire over at Venue.

[Images: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division]. [Images: Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division].

|

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the