Tuesday, November 05. 2013

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

Twitter data reveals the cities that set trends and those that follow. And the difference may be in the way air passengers carry information across the country, by-passing the Internet, say network scientists.

One of the defining properties of social networks is the ease with which information can spread across them. This flow leads to information avalanches in which videos or photographs or other content becomes viral across entire countries, continents and even the globe.

It’s easy to imagine that these trends are simply the result of the properties of the network. Indeed, there are plenty of studies that seem to show this.

But in recent years, researchers have become increasingly interested in the relationship between a network and the geography it is superimposed on. What role does geography play in the emergence and spread of trends? And which areas are trend setters and which are trend followers?

Today we get an answer of sorts thanks to the work of Emilio Ferrara and pals at Indiana University in Bloomington. These guys have examined the way trends emerge in cities across the US and how they spread to other cities and beyond.

Their research allows them to classify US cities as sources, those that lead the way in trends, or those that follow the trends which the team call sinks.

Their research also leads to a curious conclusion–that air travel plays a crucial role in the spread of information around the country This implies that trends spread from one part of the country to another not over the internet but via air passengers, just like diseases.

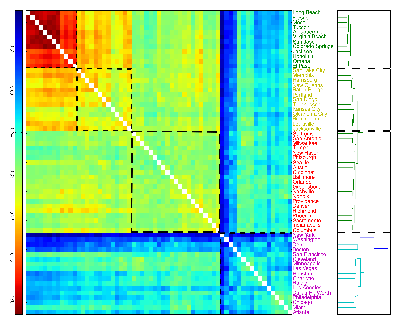

The method these guys use is straightforward. Twitter publishes a continuously updated list pf the the top ten most popular phrases or hashtags on its webpage. It also has webpages showing the trending topics for each of 63 US cities.

To capture the way these trends emerge and spread, Ferrra and co set up a web crawler to check each list every ten minutes between 12 April and 30 May 2013. In this way the collected over 11,000 different phrases and hashtags that became popular throughout these 50 days.

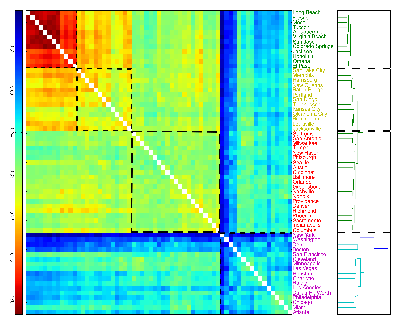

They then plotted the evolution of these trends in each US city over time. This allowed them to study how trends spread from one city to another and to look for clusters of cities in which the same topics trend together.

The results are revealing. They say most trends die away quickly–around 70 per cent of trends last only 20 minutes and only 0.3 per cent last more than a day.

Ferrara and co say they can see three distinct geographical regions that share similar trends–the East Coast, the Midwest and Southwest. It’s easy to imagine how trends arise at a low level and spread through the region through local links such as friends.

But these guys say there is also a fourth cluster of influential cities that also form a group where the emergence of trends is related. However, these place are not geographically related. They are metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles, New York, Atlanta, Chicago and so on.

What links these places is not geography but airports, say Ferrara and co. Their hypothesis is that topics trend in these places because of the influence of air passengers. In other words, trending topics spread just like diseases.

Ferrara and co have created a list of the cities that act as trend setters and those that act as trend followers.

The top five sources of trends are: Los Angeles, Cincinnati, Washington, Seattle and New York.

The top five trend followers (or sinks) are: Oklahoma City, Albuquerque, El Paso, Omaha and Kansas City.

That’s a fascinating result. In a sense it’s obvious that the large scale movement of people will influence the apread of information However, it’s not obvious that this should happen at a rate that is comparable to the spread of trends across the internet itself.

And it raises an interesting question that Ferrara and co hope to answer in future work. “Does information travel faster by airplane than over the Internet?” they ask.

We’ll be watching for when they reveal the answer.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1310.2671 : Traveling Trends: Social Butterflies or Frequent Fliers?

Personal comment:

Interesting results (information travels by plane either, like diseases...), yet when only 0.3% of "trends" last more than a day, we can wonder if it even matters to have concerns about the 99.7% other ones (just some crap lolcats stuff ?)... or that on the contrary, it could possibly be the revelator of incredible "short time" pulses of "things/memes/subjects" in and in-between cities?

Nonetheless, if being more picky about the trends that are analyzed, this could certainly reveal some interesting and spreading "mood" patterns between cities.

Monday, October 21. 2013

Note: will the communication industry be the one to finally build the Instant City?

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

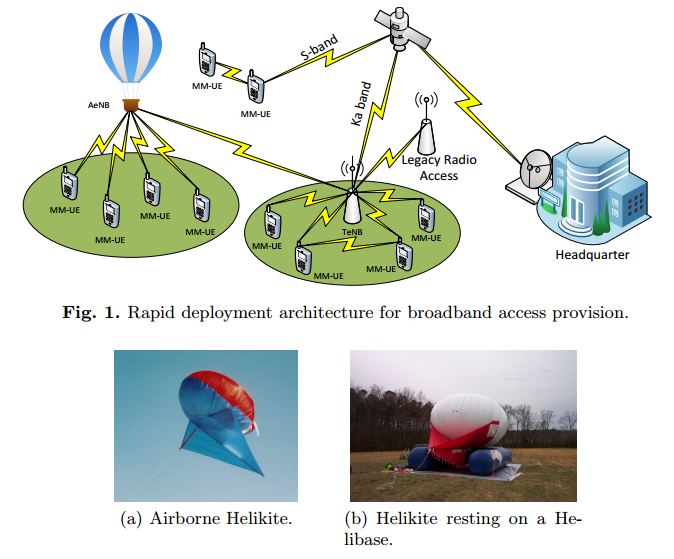

A rapidly-deployable airborne communications network could transform communications during disasters, say researchers

Most people will have had the experience of being unable to get a mobile phone signal at a major sporting event, music festival or just in a crowded railway station. The problem becomes even more acute in emergency situations, such as in earthquake disasters zones, where the telecommunications infrastructure has been damaged.

So the ability to set up a new infrastructure quickly and easily is surely of great use.

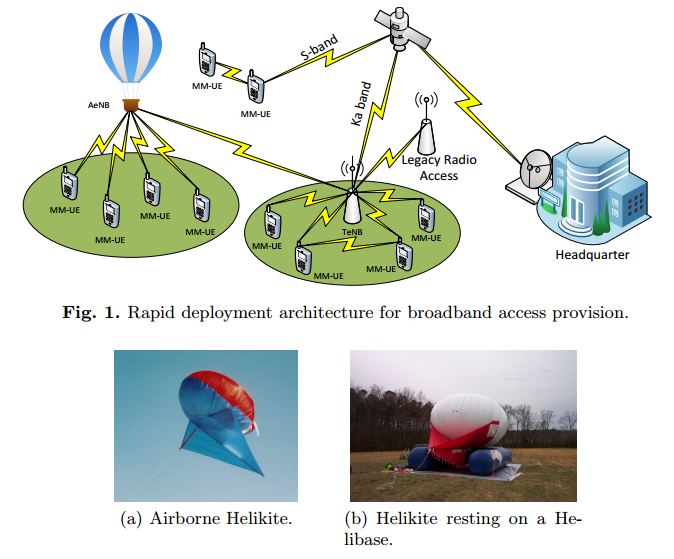

Today, Alvaro Valcarce at TRiaGnoSys, a mobile communications R&D company in Germany, and a few pals unveil a system that could make this easier. These guys have developed a rapidly deployable wireless network system in the form of airborne base stations carried aloft by kite-shaped balloons called Helikites with a lifting capacity of 10 kg and that can remain airborne at an altitude of up to 4 km for several days, provided the weather conditions allow.

Valcarce and co say the system can be quickly deployed and provides large local mobile phone coverage thanks to a combination of multiple airborne nodes that link in to terrestrial and satellite telecommunications systems.

Their idea is that these systems could be deployed by network companies during temporary events such as the Olympic Games, or by first responders to an emergency event to set up the vital communications infrastructure necessary to coordinate emergency services.

One of the key challenges is to get the new equipment to work seamlessly with existing terrestrial networks. And to that end, Valcarce have been testing their airborne Helikite.

The team has a number of challenges to overcome in its ongoing work. For example the altitude of the Helikite determines its coverage but also influences the network capacity and delays. Evaluating these effects is one part of their future goals.

Having ironed out these kinds of operational problems, such a system will surely be valuable in a wide range of situations where reliable communication is not just a useful bonus but a life-saving necessity.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1307.3158 : Airborne Base Stations for Emergency and Temporary Events

Friday, September 20. 2013

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

By The Physics arXiv Blog

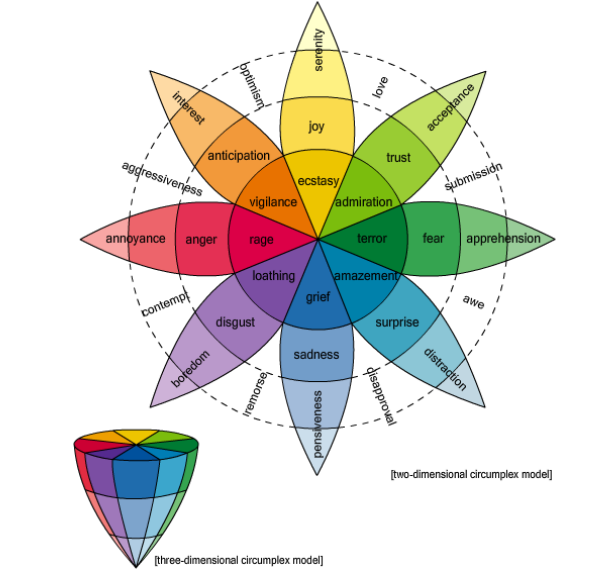

Sentiment analysis on the social web depends on how a person’s state of mind is expressed in words. Now a new database of the links between words and emotions could provide a better foundation for this kind of analysis.

One of the buzzphrases associated with the social web is sentiment analysis. This is the ability to determine a person’s opinion or state of mind by analysing the words they post on Twitter, Facebook or some other medium.

Much has been promised with this method—the ability to measure satisfaction with politicians, movies and products; the ability to better manage customer relations; the ability to create dialogue for emotion-aware games; the ability to measure the flow of emotion in novels; and so on.

The idea is to entirely automate this process—to analyse the firehose of words produced by social websites using advanced data mining techniques to gauge sentiment on a vast scale.

But all this depends on how well we understand the emotion and polarity (whether negative or positive) that people associate with each word or combinations of words.

Today, Saif Mohammad and Peter Turney at the National Research Council Canada in Ottawa unveil a huge database of words and their associated emotions and polarity, which they have assembled quickly and inexpensively using Amazon’s crowdsourcing Mechanical Turk website. They say this crowdsourcing mechanism makes it possible to increase the size and quality of the database quickly and easily.

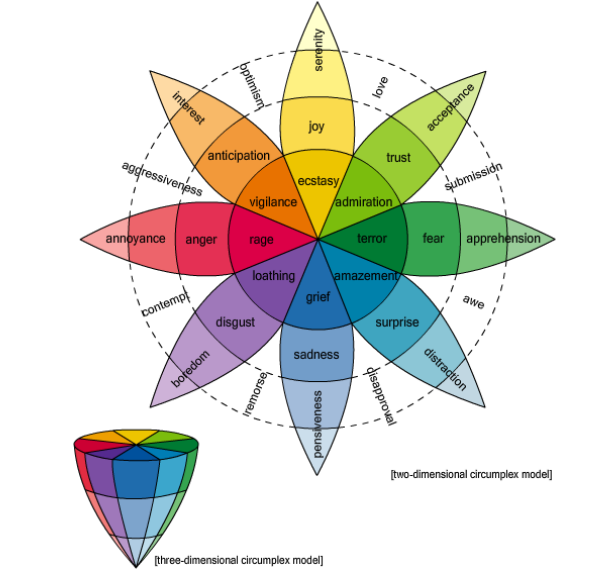

Most psychologists believe that there are essentially six basic emotions– joy, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and surprise– or at most eight if you include trust and anticipation. So the task of any word-emotion lexicon is to determine how strongly a word is associated with each of these emotions.

One way to do this is to use a small group of experts to associate emotions with a set of words. One of the most famous databases, created in the 1960s and known as the General Inquirer database, has over 11,000 words labelled with 182 different tags, including some of the emotions that psychologist now think are the most basic.

A more modern database is the WordNet Affect Lexicon, which has a few hundred words tagged in this way. This used a small group of experts to manually tag a set of seed words with the basic emotions. The size of this database was then dramatically increased by automatically associating the same emotions with all the synonyms of these words.

One of the problems with these approaches is the sheer time it takes to compile a large database so Mohammad and Turney tried a different approach.

These guys selected about 10,000 words from an existing thesaurus and the lexicons described above and then created a set of five questions to ask about each word that would reveal the emotions and polarity associated with it. That’s a total of over 50,000 questions.

They then asked these questions to over 2000 people, or Turkers, on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk website, paying 4 cents for each set of properly answered questions.

The result is a comprehensive word-emotion lexicon for over 10,000 words or two-word phrases which they call EmoLex.

One important factor in this research is the quality of the answers that crowdsourcing gives. For example, some Turkers might answer at random or even deliberately enter wrong answers.

Mohammad and Turney have tackled this by inserting test questions that they use to judge whether or not the Turker is answering well. If not, all the data from that person is ignored.

They tested the quality of their database by comparing it to earlier ones created by experts and say it compares well. “We compared a subset of our lexicon with existing gold standard data to show that the annotations obtained are indeed of high quality,” they say.

This approach has significant potential for the future. Mohammad and Turney say it should be straightforward to increase the size of the date database and at the same technique can be easily adapted to create similar lexicons in other languages. And all this can be done very cheaply—they spent $2100 on Mechanical Turk in this work.

The bottom line is that sentiment analysis can only ever be as good as the database on which it relies. With EmoLex, analysts have a new tool for their box of tricks.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1308.6297: Crowdsourcing a Word-Emotion Association Lexicon.

Wednesday, May 23. 2012

-----

by Bruce Sterling

*In contemporary practice, I guess this Vurb verbiage from FutureEverywhere boils down to “my pocket keeps beeping all the time,” but, well, of course in a network society you can take everyone you know and everyone you own, and scatter them across the planet’s surface. Especially if they already did that with you.

http://juhavantzelfde.com/post/23506562343/the-aspatial-city

(…)

“In the background there are at the same time deeper, more systemic developments taking place: high-speed internet access, ubicomp, cloud computing, sensor networks, big data, etc.. And out of these, some weird, boutique threads that are relevant to spatial practice, like the 3D printing of rooms, robots weaving buildings, self-driving cars, domestic drones, urban operating systems and nonhuman cities.

“A few weeks ago, my dear friend Ben Cerveny stopped over in Amsterdam for a weekend on his way to Geneva. For a few years, Ben had been living in Amsterdam for some months a year, traveling back to San Francisco and Los Angeles after summer and returning to Amsterdam after winter. (((No wonder I keep running into that Cerveny guy all the time.)))

“It had almost been two years since we last saw each other, but because we have constantly been in touch via Twitter, Facebook, Foursquare, Instagram and iChat, I felt like it had been only yesterday. When I explained this to Ben, he immediately said, without stopping to think about what he was saying, ‘oh of course: the continuous partial everywhere.’

“And that is exactly it. The continous partial everywhere is the aspatial experience of simultaneity in immediate media. I am in the city where my friends are at the same as the one where I am myself. The city for me is no longer only a city in space, but now also a city in time. An aspatial city, without distances, in a kind of aspace….”

Thursday, May 03. 2012

-----

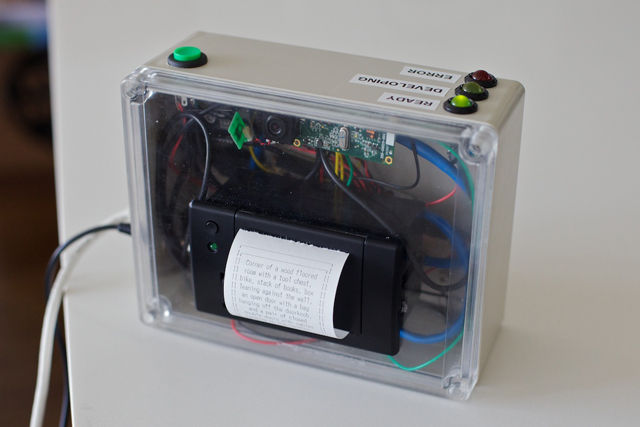

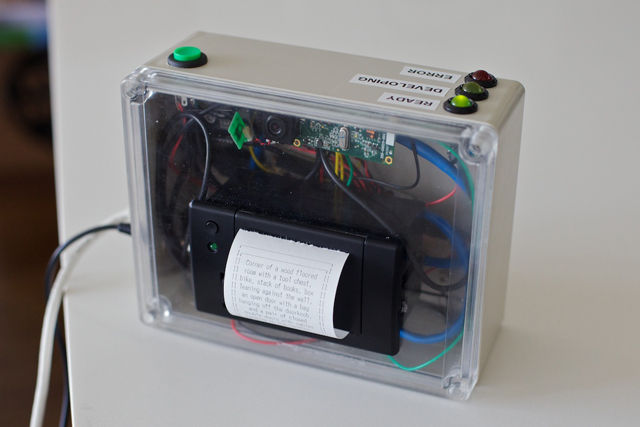

While most camera innovations are aimed at higher megapixel counts or new image capturing techniques, Matt Richardson is taking an entirely different route with the Descriptive Camera: creating a device that turns your captured imagery into words. Designed as part of a class for New York University's Interactive Telecommunications Program, the camera consists of a USB webcam, a shutter button, a small thermal printer, and an ethernet connection. When a picture is "snapped," it's sent off to humans for analysis via Amazon's Mechanical Turk API. The human on the other end then creates a written description of the image, which is sent back to the camera. The resulting text is printed with the thermal printer, framed by a Polaroid-style photo outline (an example Richardson provides reads "It's a dark room with a window. The image is quite pixelated."

According to Richardson's post about the project, the Amazon Human Intelligence Task — or HIT — cost is about $1.25 for each image, with results usually taking between three to six minutes to return. An "accomplice mode" actually lets the camera send out links to the image via instant messenger, providing a cheaper option for human interpretation. While the device currently requires external power from a 5-volt source, Richardson does hope to make a version at some point that runs off self-contained batteries and can use wireless data. It's certainly an interesting project, and we won't deny that we're smitten with the idea of taking images out and about in the world, and seeing them perceived through someone else's eyes.

Wednesday, May 02. 2012

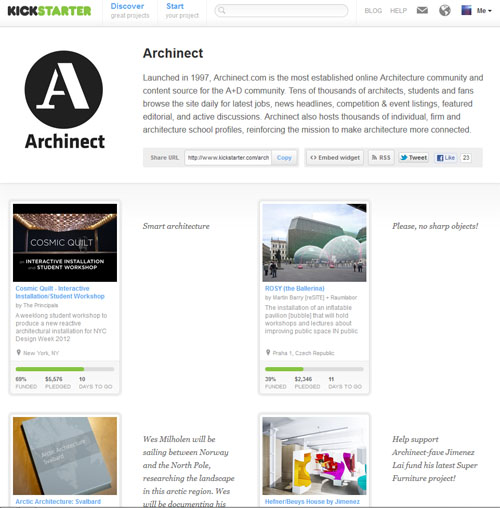

Archinect opened a page on Kickstarter with curated content.

Check it out to see if you want to help build an eco-pool in NYC, to support Raumlabor to build an inflatable or David Lynch to be documented! Or else...

Friday, March 23. 2012

Via Pasta&Vinegar

-----

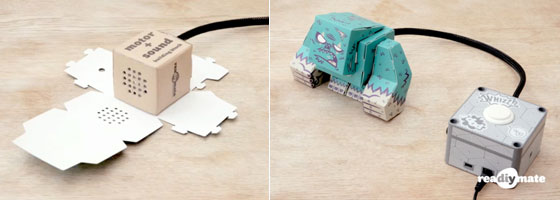

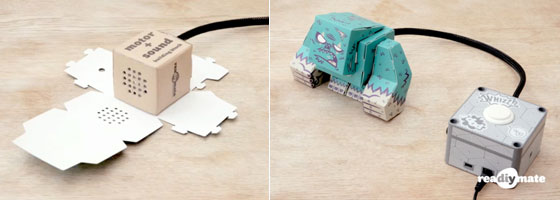

- reaDIYmate: Wi-Fi paper companions

"reaDIYmates are fun Wi-fi paper companions that move and play sounds depending on what's happening in your digital life. Assemble them in 10 minutes with no tools or glue, then choose what you want them to do through a simple web interface. Link them to your digital life (Gmail, Facebook, Twitter, Foursquare, RSS feeds, SoundCloud, If This Then That, and more to come) or control them remotely in real time from your iPhone."

Tuesday, March 06. 2012

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

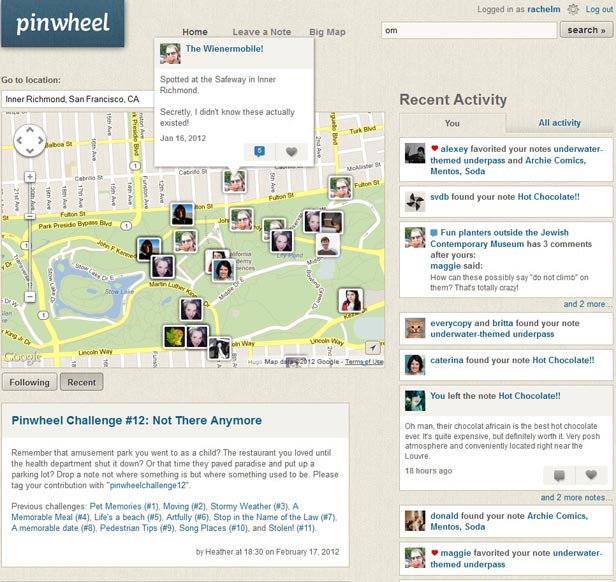

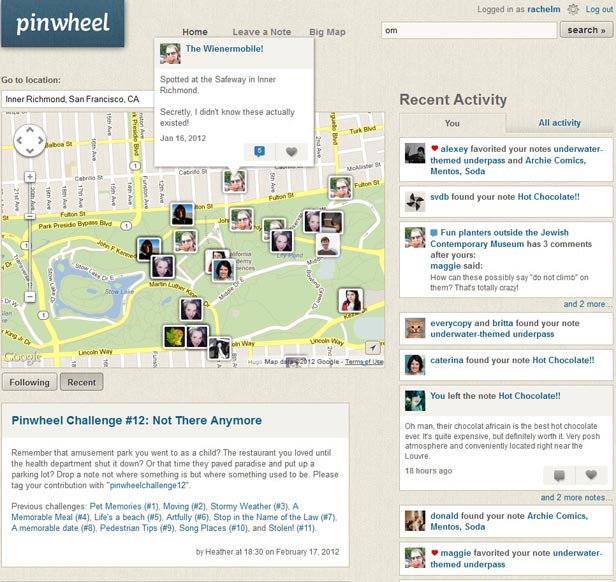

Pinwheel, a new site created by Flickr cofounder Caterina Fake, lets users post virtual notes anywhere.

By Rachel Metz

You've probably left plenty of notes for people in the past—on a kitchen counter, slipped through the slots of a locker, or even scrawled on a bathroom wall. But what if you could leave notes anywhere in the world for anyone to discover, and find ones posted by others?

That's the idea behind Pinwheel, the latest startup from Flickr cofounder Caterina Fake. Though the social site only recently emerged in a private beta testing phase, it's gaining buzz for its simple premise: letting people annotate a map with notes on any topic that can be shared with others.

Fake, a fan of the GPS treasure-hunting activity known as geocaching, says Pinwheel merges several ideas and inspirations. She first began toying with the idea of leaving virtual notes for others to find back in 1999, but the technology wasn't there to support it. And after cofounding Flickr in 2004, she was inspired by users of that site who would annotate satellite maps of their hometowns with notes about various locations. Now, as smart phones have become incredibly popular and location-based apps like Foursquare have blossomed, Fake is confident that the timing is right for Pinwheel, too.

The site's main page—which you need an invitation to see—shows a stream of recently posted notes, and users can browse a map there to check out public notes, leave notes, or search for notes or users.

Navigating the main map is like exploring a visual mash-up of a travel and restaurant guide peppered with memories of first kisses and apartments, event notices, historical facts, and more. There are burger and sushi recommendations, notes about good places to watch the sun set, and tags marking a long-gone movie theater and candy store. One user has been using Pinwheel to log crimes—including the kidnapping and return of Banana Sam, a squirrel monkey belonging to the San Francisco Zoo (now safely returned)—while another is recording historic facts in various cities.

"To me, when you are creating social software, the most exciting part of it is when people start using your tools for things you hadn't expected," Fake says.

At the moment, there is no Pinwheel smart-phone app to help you leave notes on the fly, so users simply log on to the Pinwheel website to do so (there is a mobile site, and Fake says an iPhone app is forthcoming).

Notes can be set as visible to any site user, or just to certain people that you've chosen to follow on the site. Currently, notes can only include text or photos, but Fake says this could eventually expand to audio or video clips as well.

As of early last week, only about 1,000 people were using the site, but Fake says tens of thousands of people have requested invites, and Pinwheel is now sending those out.

Jason Hong, an associate professor at Carnegie Mellon University who studies mobile social technology, sees interesting possibilities for Pinwheel as well as several challenges, including how to gain a critical mass of users and content given the popularity of existing tools like Yelp, Foursquare, and Twitter. "People are still struggling with what, exactly, they're using this for," he says.

Regardless, investors are confident Pinwheel is on to something. The site recently raised $7.5 million in a Series A funding round led by Redpoint Ventures, which added to the $2 million in funding Pinwheel had previously raised. Fake's past success helped, too—photo-sharing site Flickr sold to Yahoo in 2005 and the recommendation engine Hunch, which she also cofounded, sold to eBay in 2011, both for undisclosed amounts.

And, unlike many other Silicon Valley startups, Pinwheel does have a business model: it plans to make money by allowing sponsored notes, something that it's already testing out.

Redpoint partner Geoff Yang says he liked the notion of bringing an offline activity like leaving notes onto the Web, and he sees the site as the combination of social, mobile, and local trends. "I thought the idea was really interesting—the notion that Pinwheel, in many respects, makes places come alive," he says.

Copyright Technology Review 2012.

Personal comment:

An idea (and technology) of annotating the physical world with digital (geolocalized) notes that comes again.

Tuesday, November 22. 2011

Via GeekOSystem via Computed·Blg

-----

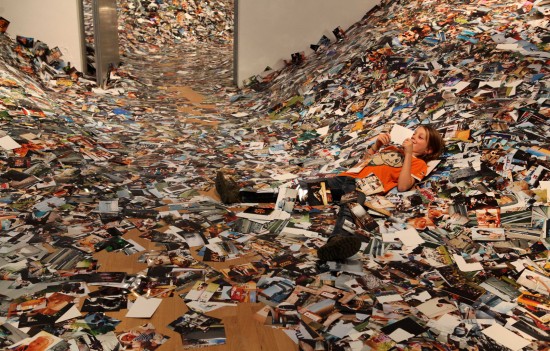

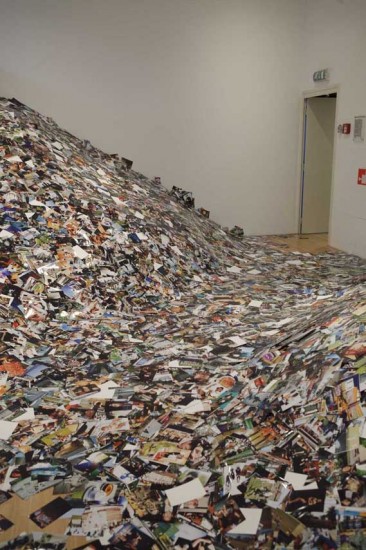

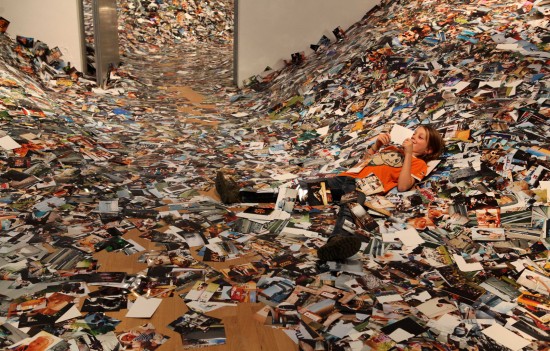

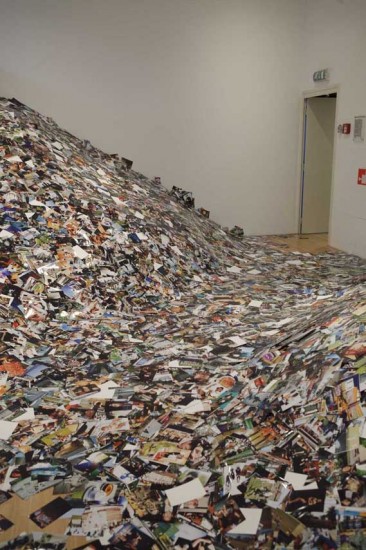

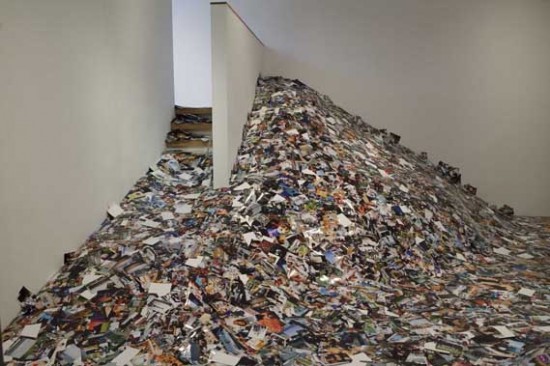

A new installation at the Amsterdam Foam gallery by Erik Kessels takes a literal look at the digital deluge of photos online by printing out 24 hours worth of uploads to Flickr. The result is rooms filled with over 1,000,000 printed photos, piled up against the walls.

There’s a sense of waste and a maddening disorganization to it all, both of which are apparently intentional. According to Creative Review, Kessels said of his own project:

“We’re exposed to an overload of images nowadays,” says Kessels. “This glut is in large part the result of image-sharing sites like Flickr, networking sites like Facebook, and picture-based search engines. Their content mingles public and private, with the very personal being openly and un-selfconsciously displayed. By printing all the images uploaded in a 24-hour period, I visualise the feeling of drowning in representations of other peoples’ experiences.”

Humbling, and certainly thought provoking, Kessel’s work challenges the notion that everything can and should be shared, which has become fundamental to the modern web. Then again, perhaps it’s only wasteful and overwhelming when you print all the pictures and divorce them from their original context.

Tuesday, October 04. 2011

-----

de Zak Stone

Before there was MySpace, there was GeoCities, the vast metropolis of glitchy amateur websites, pulsating with gif animations, that were the hub of digital culture for countless late-'90s teens. If you haven't found yourself in some cobweb-coated corner of the internet in a while and landed on one of their sites, that's because Yahoo shut down U.S. GeoCities two years ago, just 10 years after acquiring it for $3.57 billion at the height of the dot-com boom.

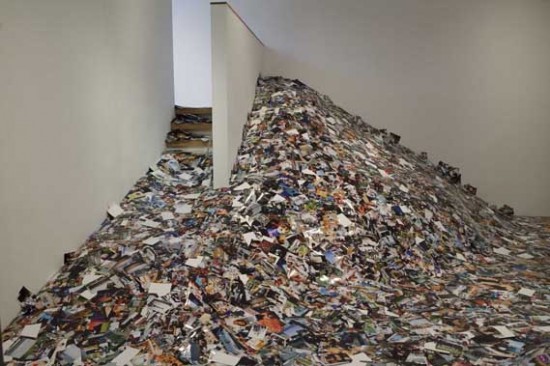

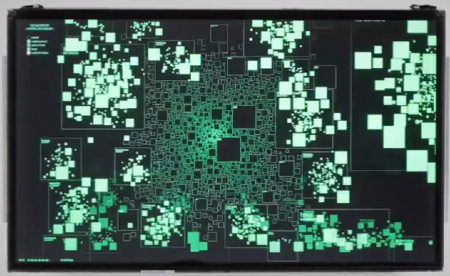

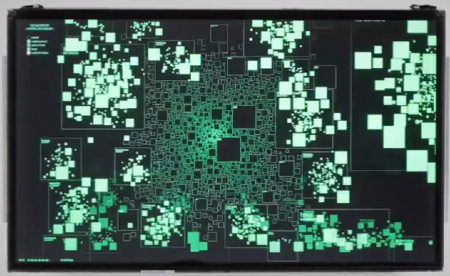

Pained by the potential loss of the record of 35 million participants' personal expression, the Internet Archive Team launched a project to save the GeoCities data for posterity, releasing a 641-GB torrent file worth of GeoCities data on the one year anniversary of its closing last October. Now this year, Dutch information designer Richard Vijgen has plotted that data along a scrollable world map of all those ancient GeoCities. He's calling it The Deleted City, "a digital archaeology of the world wide web as it exploded into the 21st century." It lives as an interactive touchscreen data visualization.

The project gives a visual representation to the change in thinking and living through the internet that we've undergone in the past decade and a half. Before the internet was understood as a (social) network, GeoCities conceived of it as a city, where "homesteaders" could build on a digital parcel, grouped in "neighborhoods" based on topic. (Celebrity oriented sites were grouped together in "Hollywood," for example.) The Deleted City replicates this logic by organizing the old websites along an urban grid. Thematic "neighborhoods" that had more content associated appear bigger. As you wander the city, you can zoom in to get more detail, and eventually locate individual html sites.

While GeoCities lives on in the popular imagination as the punchline of design and tech jokes—there's even a website to paint over slick 21st-century design with a GeoCities patina—Deleted Cities draws attention to the the way that it helped many people pioneer the web, and captures a slice of web history in a dynamic and elegant way.

Via Fast Company's Co.Design

|