Wednesday, May 07. 2014

Vanishing Ice | #photo #book

Wednesday, October 30. 2013

Le drone, objet violent non identifié | #drones

Via Le Temps (thx Nicolas Besson for the link)

-----

Par Réda Benkirane

Dans un livre pionnier, «Théorie du drone», le philosophe français Grégoire Chamayou analyse le rôle grandissant du drone dans la guerre moderne, et sur ce qu’il changera en termes de géopolitique et de surveillance globale.

Grégoire Chamayou, Editions La Fabrique, 363 pages.

Le drone est un «objet violent non identifié» qui est en train de miner le concept de guerre tel qu’on le connaît depuis Sun Tzu jusqu’à Clausewitz. Dans une œuvre de pionnier, le philosophe français Grégoire Chamayou décode cet objet qui soulève quantité de questions relatives à la stratégie, à la violence armée, à l’éthique de la guerre et de la paix, à la souveraineté et au droit. Le drone et ses clones robotiques ouvrent au sein des conflits violents une vaste terra incognita totalement impensée par le droit international et les lois immémoriales de la guerre.

Dans un ouvrage magistral, le philosophe entreprend la toute première réflexion sur cette nouvelle forme de violence, née de la généralisation d’un gadget militaire, le drone, ce véhicule terrestre, naval ou aéronautique sans homme à son bord (unmanned).

Les drones Predator et Reaper ont la particularité de voler à plus de 6000 mètres d’altitude et d’être télécommandés par des individus souvent civils (faut-il les considérer comme des combattants?) depuis une salle de contrôle informatique du Nevada. D’un clic de souris, un téléopérateur appuie sur une gâchette et déclenche un missile distant de milliers de kilomètres qui immédiatement s’abat sur un village du Pakistan, du Yémen ou de Somalie. Le drone est «l’œil de Dieu», il entend et intercepte toutes sortes de données qu’il fusionne (data fusion) et archive à la volée: en une année, il a généré l’équivalent de 24 années d’enregistrements vidéo.

Cette Théorie du drone a le mérite d’informer sur la mutation majeure des conflits violents entamée sous les présidences Bush et adoptée par l’administration d’Obama. Le drone et la suite des engins tueurs qui se profilent à l’horizon – les Etats-Unis disposent de 6000 drones et travaillent à des avions de chasse sans pilote pour 2030 – transforment une tactique adjacente en stratégie globale, et font de l’anti-terrorisme et de la politique sécuritaire leur doctrine de combat du siècle. Initiés par les Israéliens, premiers adeptes de l’euphémique devise «personne ne meurt sauf l’ennemi», puis repris par les «neocons» américains, les drones font le miel de l’équipe d’Obama, pour qui «tuer vaut mieux que capturer», liquider par avance les suspects terroristes étant préférable à leur enfermement à Guantanamo.

L’auteur poursuit sa démonstration sur l’imprécision et la contre-productivité du drone; du fait de l’altitude à laquelle il opère, son rayon létal est de 20 mètres, tandis que celui d’une grenade est de 3 mètres. Seule la munition classique peut être véritablement considérée comme une «arme chirurgicale» du point de vue de sa précision létale. Etant donné les milliers de morts civils qu’ils ont occasionnés, les drones ont aussi le désavantage de rallier toujours plus les populations locales aux groupuscules terroristes.

L’auteur montre comment la diminution croissante des morts des militaires et l’extension continue du «dommage collatéral» – ce mot qui cache depuis la fin de la Guerre froide la liquidation informelle de civils non combattants – procèdent de l’assomption suivante: dès qu’un actant de «l’axe du mal» est identifié, son réseau social fait de facto partie du c(h)amp du mal que l’on pourra vitrifier depuis une interface informatique. Certains avancent même l’idéal déréalisant que la robotique létale constituerait l’«arme humanitaire» par excellence et l’auteur fait observer combien l’euphémisation des enjeux militaires est légitimée par la rhétorique du care. Chamayou voit dans la novlangue sur le militaire humanitaire les débuts d’une politique «humilitaire».

La géopolitique est en train de laisser place à une aéropolitique. La guerre n’est plus un affrontement ni un duel entre parties combattantes sur un territoire délimité, mais une «chasse à l’homme», où un prédateur poursuit partout et tout le temps une proie humaine. Les notions de temporalité, de territorialité, de frontière, d’éthique guerrière et de droit humanitaire sont rendues obsolètes par ces armes low cost et high-tech.

L’auteur prédit un avenir fait de robots-insectes miniaturisés – les nanotechnologies aidant – concourant à la mise en place d’un système panoptique complet qui risque d’enserrer les Etats et les citoyens.

Cet ouvrage, d’ores et déjà incontournable, en appelle à une prise de conscience politique face à la déshumanisation en cours derrière ce nouvel art de surveiller, d’intercepter et d’anéantir.

Related Links:

Personal comment:

Following my recent post about drones (as scanning devices), there are obviously different types of drones and like any other technology, it looks like that this one too has two sides... We are now probably in need of some renewed "Contrat Social" that would take into account additional "parameters" (between humans and machines/technologies + between humans and our planet --Contrat naturel--).

Friday, September 06. 2013

Landscape Futures Arrives

Via BLDGBLOG

-----

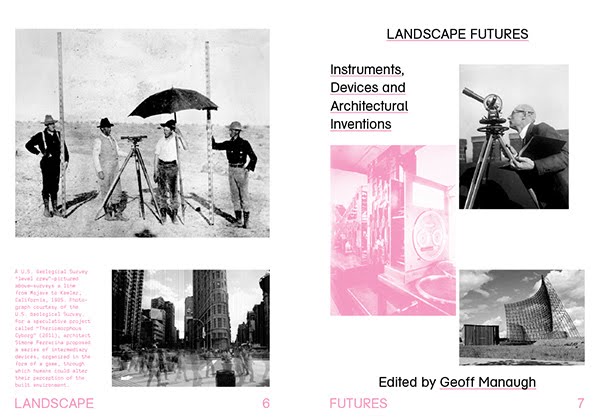

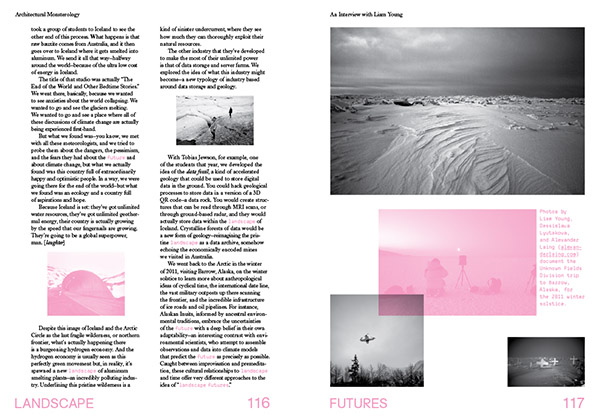

[Image: Internal title page from Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

At long last, after a delay from the printer, Landscape Futures: Instruments, Devices and Architectural Inventions is finally out and shipping internationally.

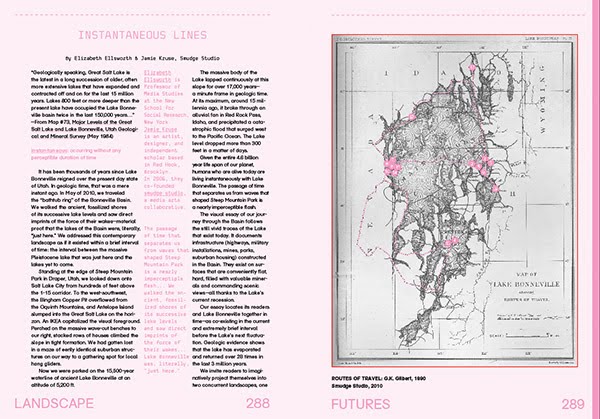

I am incredibly excited about the book, to be honest, and about the huge variety of content it features. It includes original essays by Sam Jacob, Cassim Shepard, and Elizabeth Ellsworth & Jamie Kruse of Smudge Studio; a short piece of dredge-themed landscape fiction by Pushcart Prize-winning author Scott Geiger; and a readymade course outline—open for anyone looking to teach a course on oceanographic instrumentation—by Mammoth's Rob Holmes.

These join reprints of classic texts by geologist Jan Zalasiewicz, on the incipient fossilization of our cities 100 million years from now; a look at the perverse history of weather warfare and the possibility of planetary-scale climate manipulation by James Fleming; and a brilliant analysis of the Temple of Dendur, currently held deep in the controlled atmosphere of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, and its implications for architectural preservation elsewhere.

And even these are complemented by an urban hiking tour by the Center for Land Use Interpretation that takes you up into the hills of Los Angeles to visit check dams, debris basins, radio antennas, and cell phone towers, and a series of ultra-short stories set in a Chicago yet to come by Pruned's Alexander Trevi.

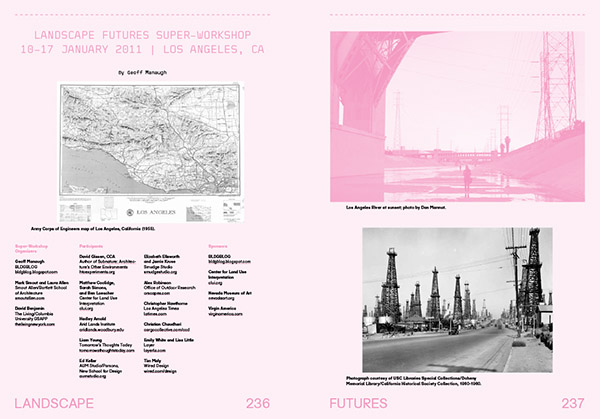

[Images: A few spreads from the "Landscape Futures Sourcebook" featured in Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

Of course, everything just listed supplements and expands on the heart of the book, which documents the eponymous exhibition hosted at the Nevada Museum of Art, featuring specially commissioned work by Smout Allen, David Gissen, and The Living, and pre-existing work by Liam Young, Chris Woebken & Kenichi Okada, and Lateral Office.

Extensive original interviews with the exhibiting architects and designers, and a long curator's essay—describing the exhibition's focus on the intermediary devices, instruments, and spatial machines that can fundamentally transform how human beings perceive and understand the landscapes around them—complete the book, in addition to hundreds of images, many maps, and an extensive use of metallic and fluorescent inks.

The book is currently only $17.97 on Amazon.com, as well, which seems like an almost unbelievable deal; now is an awesome time to buy a copy.

[Images: Interview spreads from Landscape Futures; book design by Everything-Type-Company].

In any case, I've written about Landscape Futures here before, and an exhaustive preview of it can be seen in this earlier post.

I just wanted to put up a notice that the book is finally shipping worldwide, with a new publication date of August 2013, and I look forward to hearing what people think. Enjoy!

Thursday, July 04. 2013

Eyes on the Sky – Weather as data paintings by Jed Carter

-----

Eyes on the Sky is a process-based investigation into generative design and the weather linking 64 public-access web cameras across Europe, recording the colour of the sky and producing a book that collects a week of paintings where cameras paint the weather.

Monday, June 04. 2012

Great speculations /// The Repertoire of Metabolism by Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist

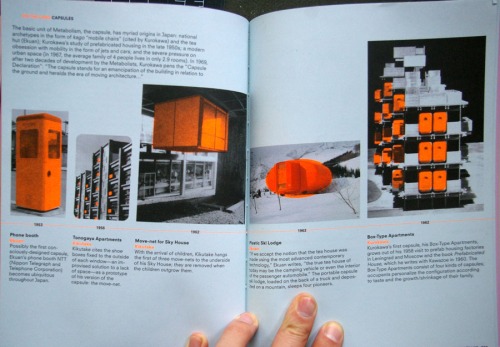

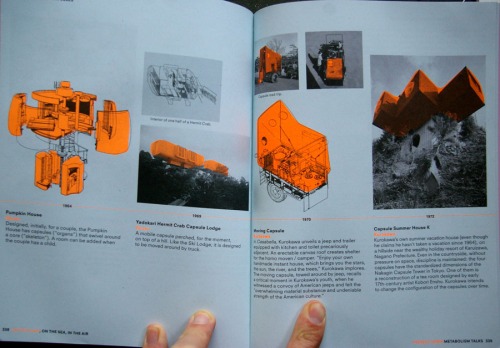

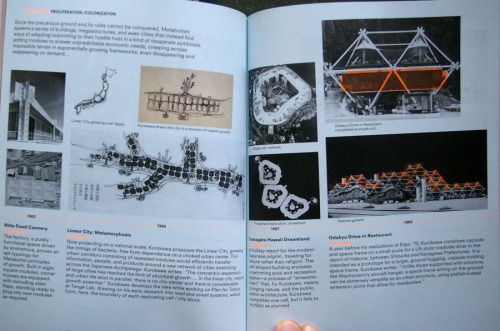

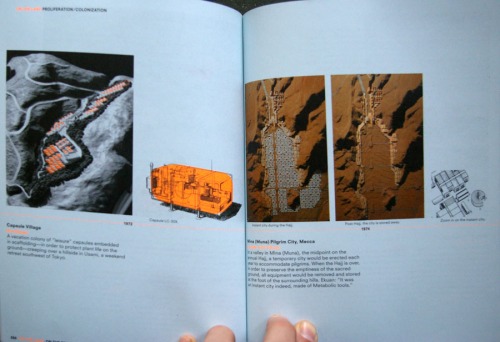

Photograph of the book Project Japan by Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist. (editors Kayoko Ota with James Westcott) Koln: Taschen, 2011.

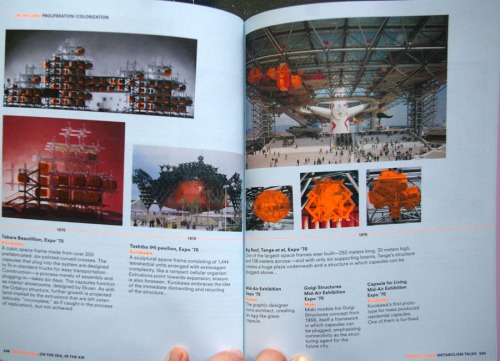

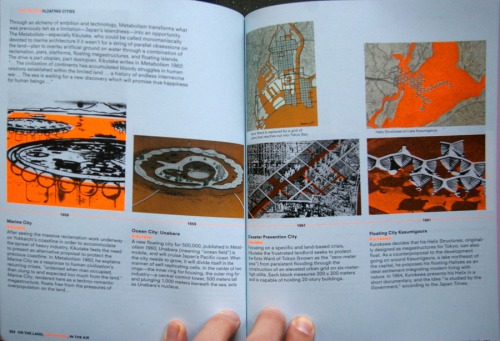

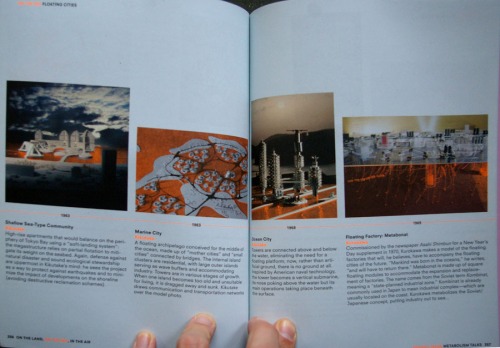

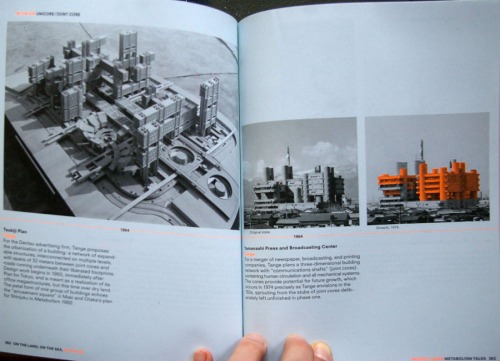

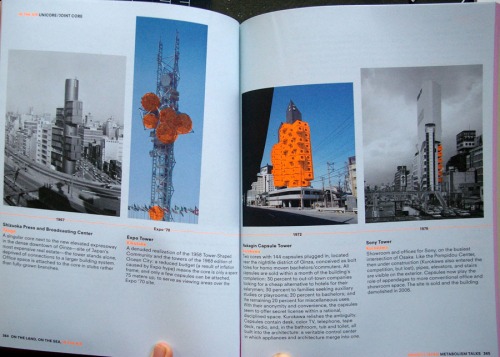

In a move that he clearly enjoy, Rem Koolhaas along with Hans Ulrich Obrist re-introduce the Metabolists in an era that consecrates SANAA and their followers as the new Japanese paradigm for global architecture. It is indeed difficult to find two visions of architecture that different and the fact that they were produced in the same country makes this opposition even more visible. The 700-page book Project Japan can therefore be considered, not as a retroactive manifesto (that was the self-definition of Koolhaas’ Delirious New York), but rather as a rehabilitative archive. It is a document that illustrates the coherency of a historical movement created as both individual and collective work in a way that cannot be observed in any way nowadays. Through interviews with almost all the actors of this movement -Kurokawa and Kitutake died since then-, R.Koolhaas and H.U.Obrist explore as much the origins of this ambition (they find them in Kenzo Tange’s experience of the war in China and its large territories) as the globalization of the movement which saw the Metabolists proposed many projects in the Middle East. The photographs of Charlie Koolhaas of several buildings built in the 60′s in their current state also bring an interesting comparison with the original documents and the endurance (or not) of those building to time.

Beyond the subjective reading of the two Europeans, this book is mostly a very valuable archive of documents created by the Metabolists, many of them which are probably not findable in already published books. In this regard, the Repertoire of Metabolism is particularly rich through its succinctness. In thirty four pages, we access to a visual inventory of the various architectural inventions or appropriations that the Metabolists have been developing through their work. The key typological words are the following:

- Capsules

- Ground/Artificial Ground

- Proliferation/Colonization

- Group Form

- Floating Cities

- Unicore/Joint core

- Megaforest

The following (bad quality) photos constitutes an excerpt of this chapter. They are all extracted from the book Project Japan by Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist. (editors Kayoko Ota with James Westcott) Koln: Taschen, 2011.

Thursday, April 19. 2012

Join Archinect in Hollywood this Thursday for "Publish Or... bracket [GOES SOFT]"

Archinect and Woodbury School of Architecture are proud to present:

Publish Or... bracket [GOES SOFT]

Thursday, April 19

6:00 p.m.

Sonic landscape by Health and Beauty.

WUHO Gallery

6518 Hollywood Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA 90028 (map)

Come say hello, mingle, and check out selected entries from bracket [goes soft]. Including work by Woodbury School of Architecture faculty member Ewan Branda.

Limited edition zine-syle [goes-soft] take-aways. First come, first serve.

Bracket [goes soft] examines the use and implications of soft today—from the scale of material innovation to territorial networks. While the projects in Bracket 2 are diverse in deployment and issues they engage, they share several key characteristics—proposing systems, networks and technologies that are responsive, adaptable, scalable, non-linear, and multivalent. Certain projects reveal how soft systems rely on engagement with their larger environment, collecting and sensingenvironmental atmospheric information, and through feedback, adapting the system to augment performance. Other projects examine how soft systems can function as interfaces with the environment—whether mitigating or harnessing it—operating at the scale of a wall, a building, or a landscape.Moreover, a particular strand of projects presented in Bracket 2 are tactical and strategic in nature, enabling them to operate, often covertly, within existing organizational structures, subverting rules and limitations for opportunism, to support new ecologies—whether natural, economic or political. Intelligence in other work lies in the organization and format of the system, accommodating transformation by rejigging components of the system itself. Adapting to extrinsic as well as intrinsic factors, enabling them to anticipate, recover and transform in unexpected situations, renders other speculations resilient to disturbances. Instead of mitigation, contingency in these soft systems is typically opportunistic. Lastly, select projects expose how the networking of smaller units or interventions, diffused across a larger territory, can generate, collect, or respond at a vast scale. Agile, these tentacular networks can diffuse or retract as resources or needs change.

The editorial board and jury for Bracket 2 includes Benjamin Bratton, Julia Czerniak, Jeffrey Inaba, Geoff Manaugh, Philippe Rahm, Charles Renfro, as well as co-editors Lola Sheppard and Neeraj Bhatia.

Bracket 2 is published by Actar and designed by Thumb.

Related Links:

Personal comment:

fabric | ch publishes its project Arctic Opening (pdf) in the second volume of Bracket. Subject of this edition of Bracket is "software", or how the projects that are presented "share several key characteristics—proposing systems, networks and technologies that are responsive, adaptable, scalable, non-linear, and multivalent."

Monday, March 26. 2012

By Revealing the Existence of Other Worlds, the Book is a Subversive Artifact

Excerpt from Le Processus by Marc-Antoine Mathieu (Delcourt 1993)

Following the three last articles in which I was preparing my reference texts in addition of those that I have been already writing in the past, this following article is an attempt to reconstitute the small presentation I was kindly invited to give by Carla Leitão for her seminar about libraries and archives at Pratt Institute. This talk was trying to elaborate a small theory of the book as a subversive artifact based on six literary authors that have in common a dramatization of their own medium, the book, within their books. The predicate of this essay lies in the fact that books are indeed subversive -and therefore suppressed by authoritarian power- as they reveal the existence of other worlds.

REFERENCE TEXTS/DRAWINGS ON THE FUNAMBULIST FOR CHAPTER 1

In his series Julius Corentin Acquefacques, prisonnier des rêves, Marc-Antoine Mathieu continuously explores and questions graphic novel as the medium he uses for his narratives to exist, and therefore to acquire a certain autonomy as soon as they have been created. In reusing the constructive elements of drawings within the narrative (preparatory sketches, vanishing points, framing bars, anamorphoses etc.) he creates several layers of universes that include our own, and therefore makes us wonder if our reality couldn’t be the fiction of a higher degree of reality.

It is not innocent that he uses the terminology of the dream to bases his stories as dreams constitute the daily experience we make of another world within the world. The nightmare here, is based on the impossibility for the main character, Julius Corentin Acquefacques to distinguish what is dream, what is his reality, what is the reality of those other worlds he can see for short instants and eventually what is the reality of his creator, the author himself.

In The Trial written by Franz Kafka and published in 1929, the book as an artifact is not literally present. However, the existence of other worlds within the narrative can be found in the fact that the version we know is the one assembled by Kafka’s best friend, Max Brod who re-assembled the chapters of the unachieved book according to his own interpretation and on the contrary of his friend’s wishes who wanted it to be burnt. Brod, in a research for rationality starts the narrative by the scene in which K., the protagonist, learns that he will be judged for something he ignores, continues it by K.’s experience of the administrative labyrinth and eventually finishes it by K.’s execution. In Towards a Minor Literature, Felix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze criticize this order, cannot seem to accept that such chapter about K.’s death has been written by Kafka and eventually consider that this event is nothing more than an additional part of the character’s delirium or dream within the story. As I have been writing before in an essay entitled The Kafkian Immanent Labyrinth as a Post-Mortem Dream, my own interpretation consists in starting with this ‘last’ chapter in which K. is executed, thus attributing the following delirium to the visions that K. experiences before dying. In other words, K. never really dies for himself even though he dies in the point of view of others, of course (to read more about this topic read also my review of Gaspard Noe’s Enter the Void). His perception of time exponentially decelerates tending more and more towards the exact moment of his death without ever reaching it: this is the Kafkian nightmare.

The fact that one can counts three (and probably so many more) ways of assembling the ten chapters written by Kafka make the book itself a labyrinth allowing the existence of several parallel worlds which all share the same composing elements but presents different essences of meaning.

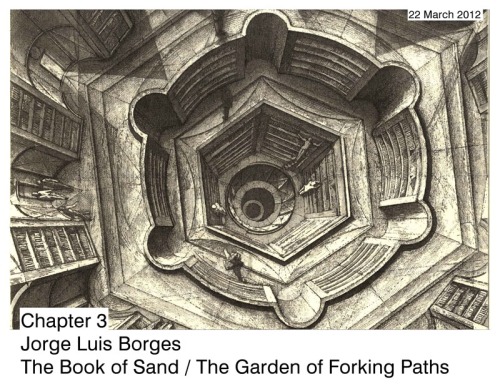

illustration by Erick Desmazieres

Jorge Luis Borges, whose filiation with Kafka is not to be demonstrated, is also well known for his quasi-Leibnizian (see previous article) invention of an infinity of parallel worlds through books. The Library of Babel (see previous post) is the most famous example as it introduces an infinite library containing every unique books that can be written in 410 pages with 25 symbols. At the end of this short story, Borges precises that this library could be in fact, contained in a single book which will be introduced later on in The Book of Sand (see the recent post about it): a book with an infinity of pages.

What is to be found in infinity seems to be indicated in the story The Secret Miracle (1943) in the following excerpt that could easily be used to essentialize Borges’ work and life:

Toward dawn he dreamed that he had concealed himself in one of the naves of the Clementine Library. A librarian wearing dark glasses asked him: “What are you looking for?” Hladik answered: “I am looking for God.” The librarian said to him: “God is in one of the letters on one of the pages of one of the four hundred thousand volumes of the Clementine. My fathers and the fathers of my fathers have searched for this letter; I have grown blind seeking it.”

in Labyrinths. New York: New Directions Book, 1962.

Many Borges’ readers will indeed know that himself lost his sight few decades after he wrote this story. What was this God that he was looking for in the many book of Buenos Aires’ National Library? Which kind of Kaballah did he create to find an esoteric meaning in the mathematics of the profane scriptures? Maybe did he have a glance to this infinity that he has been chanting for many years and became blind as a price to pay for it.

It is in fact, one thing to comprehend the infinity of contingencies that Borges presents, but it is another one to fathom it fully. Such transcendental understanding could indeed correspond to an encounter with what deserve to be called God. Borges gives us the chance, one more time, to experience such encounter through his story The Garden of Forking Paths (1941) which dramatizes a book in which the infinite combination of worlds constituted by a given sum of events since the dawn of times exists in parallel of each other:

“Here is Ts’ui Pên’s labyrinth,” he said, indicating a tall lacquered desk.

“An ivory labyrinth!” I exclaimed. “A minimum labyrinth.”

“A labyrinth of symbols,” he corrected. “An invisible labyrinth of time. To me, a barbarous Englishman, has been entrusted the revelation of this diaphanous mystery. After more than a hundred years, the details are irretrievable; but it is not hard to conjecture what happened. Ts’ui Pe must have said once: I am withdrawing to write a book. And another time: I am withdrawing to construct a labyrinth. Every one imagined two works; to no one did it occur that the book and the maze were one and the same thing. The Pavilion of the Limpid Solitude stood in the center of a garden that was perhaps intricate; that circumstance could have suggested to the heirs a physical labyrinth. Ts’ui Pên died; no one in the vast territories that were his came upon the labyrinth; the confusion of the novel suggested to me that it was the maze. Two circumstances gave me the correct solution of the problem. One: the curious legend that Ts’ui Pên had planned to create a labyrinth which would be strictly infinite. The other: a fragment of a letter I discovered.”

Albert rose. He turned his back on me for a moment; he opened a drawer of the black and gold desk. He faced me and in his hands he held a sheet of paper that had once been crimson, but was now pink and tenuous and cross-sectioned. The fame of Ts’ui Pên as a calligrapher had been justly won. I read, uncomprehendingly and with fervor, these words written with a minute brush by a man of my blood: I leave to the various futures (not to all) my garden of forking paths. Wordlessly, I returned the sheet.in Labyrinths. New York: New Directions Book, 1962.

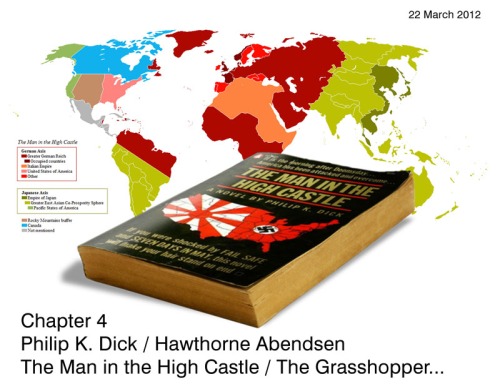

In 1962, Philip K. Dick writes a novel entitled The Man in the High Castle (see previous article) which dramatizes an uchronia for which Roosevelt died before ending his first mandate of President of the USA, replaced by an isolationist President who refuses to engage his county in the second World War. It results from this choice that the Nazis conquest Europe while the Japanese army colonizes East Asia (including Siberia) and eventually both combine their forces to invade the USA. Dick’s plot thus occurs in United States under nippo-nazi domination in which it is said to exist a book, The Grasshopper Lies Heavy written by a certain Hawthorne Abendsen who would describe in it a world in which the Allies won the over against the Axis. The book is, of course, forbidden as it allows the depiction of another reality than the one which is imposed by colonial empires:

At the bookcase she knelt. ‘Did you read this?’ she asked, taking a book out. Nearsightedly he peered. Lurid cover. Novel. ‘No,’ he said. ‘My wife got that. She reads a lot.’

‘You should read it.’

Still feeling disappointed, he grabbed the book, glanced at it. The Grasshopper Lies Heavy. ‘Isn’t this one of those banned-in-Boston books?’ he said.

‘Banned through the United States. And in Europe, of course.’ She had gone to the hall door and stood there now, waiting.

‘I’ve heard of this Hawthorne Abendsen.’ But actually he had not. All he could recall about the book was — what? That it was very popular right now. Another fad. Another mass craze. He bent down and stuck it back in the shelf. ‘I don’t have time to read popular fiction. I’m too busy with work.’ Secretaries, he thought acidly, read that junk, at home alone in bed at night. It stimulates them. Instead of the real thing. Which they’re afraid of. But of course really crave.The Man in the High Castle. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962.

The ban of books depicted in Dick’s uchronia brings us to worlds in which books have been definitely suppressed from society. In the well known 1984, written in 1949 by Georges Orwell, the only remaining book is the dictionary of the Newspeak which, editions by editions becomes thinner and thinner as the language is subjected by a strict progressive purge. Language, indeed, allows the formulation of other worlds which can be punished as thoughtcrimes. The Book is therefore not destroyed literally but its principal material is voluntarily put in scarcity.

‘The Eleventh Edition is the definitive edition,’ he said. ‘We’re getting the language into its final shape — the shape it’s going to have when nobody speaks anything else. When we’ve finished with it, people like you will have to learn it all over again. You think, I dare say, that our chief job is inventing new words. But not a bit of it! We’re destroying words — scores of them, hundreds of them, every day. We’re cutting the language down to the bone. The Eleventh Edition won’t contain a single word that will become obsolete before the year 2050.’

He bit hungrily into his bread and swallowed a couple of mouthfuls, then continued speaking, with a sort of pedant’s passion. His thin dark face had become animated, his eyes had lost their mocking expression and grown almost dreamy.

‘It’s a beautiful thing, the destruction of words. Of course the great wastage is in the verbs and adjectives, but there are hundreds of nouns that can be got rid of as well. It isn’t only the synonyms; there are also the antonyms. After all, what justification is there for a word which is simply the opposite of some other word? A word contains its opposite in itself. Take “good”, for instance. If you have a word like “good”, what need is there for a word like “bad”? “Ungood” will do just as well — better, because it’s an exact opposite, which the other is not. Or again, if you want a stronger version of “good”, what sense is there in having a whole string of vague useless words like “excellent” and “splendid” and all the rest of them? “Plusgood” covers the meaning, or “doubleplusgood” if you want something stronger still. Of course we use those forms already. but in the final version of Newspeak there’ll be nothing else. In the end the whole notion of goodness and badness will be covered by only six words — in reality, only one word. Don’t you see the beauty of that, Winston? It was B.B.’s idea originally, of course,’ he added as an afterthought.

1984. New York : Signet Classics, 1949

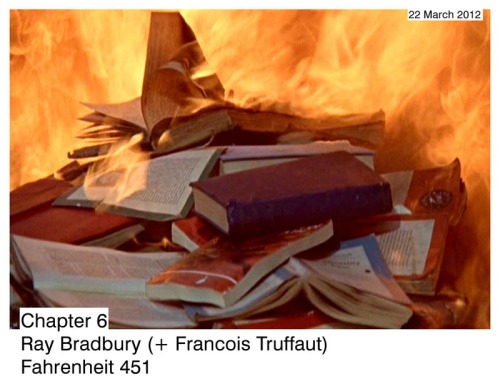

The quintessential narrative dramatizing the destruction of books is of course Fahrenheit 451 (see the recent article about it) written by Ray Bradbury in 1953. In this story, firemen are not people in charge of fighting against fire, but on the contrary, those in charge of inflaming books that have been banned as principal element of discord and inequality within society. Fahrenheit 451 (233 degrees Celsius) is indeed the temperature for which paper burns. Books are thus the object that allows the various human writings to remain archived for virtually eternity but which allow carry with them, their own fragility as their main material, paper, is vulnerable to the elements and fire in particular. Francois Truffaut, who released an excellent film adaptation of Bradbury’s novel in 1966, by showing a copy of Mein Kampf in his movie, did not miss to point out that a resistance movement that would undertake to save the books from fire could not possibly judge which books deserved to be kept and which one could be let to the institutional purge.

In the theater play Almansor that he wrote in 1820, Heinrich Heine makes the following tragic prophecy: Where we burn books, we will end up burning men. On May 10th 1933, the Nazis who recently reached the head of the executive and legislative power in Germany will burn thousands of books including Heine’s, which do not fit within the spirit of the new antisemitic/anti-communist politics they are willing to undertake. About a decade later, they will industrially kill eleven millions people (including six millions Jews) in what remains as the darkest moment of mankind’s history: the Holocaust.

Among the books burned in 1933, one could find the ones written by Marx, Freud, Brecht, Benjamin, Einstein, Kafka but also one of the father of science fiction, HG Wells. This last example illustrates well the will of the third Reich to annihilate any vision of the future that was not compliant with the one elaborated by the Nazis.

In latin, book burning ceremonies are called autodafé from Portuguese Acto da Fé (literally act of faith). Autodafé were common during the Spanish and Portuguese inquisition during the medieval era. Indeed, books listed in the Catholic Index (the list of books forbidden by the Church) and heretics were burned indistinctly in vast rituals of authoritarian religion. In 1933, this act of faith had been elaborated by Joseph Goebbels, minister of propaganda of the Reich and accomplished with great enthusiasm by hordes of students who collected and confiscated the books that have been listed as subversive. An important element in the principal autodafé of May 10th 1933 in Berlin was that the rain was preventing the flames to burn the book in such a way that firemen had to pour gasoline on the aggregation of books to set them ablaze. This significant ‘detail’ had probably a great influence on Bradbury in the elaboration of his narrative.

The books are therefore agents of infection in the point of view of an authoritarian ideological power. Their authors place in them the germs of subversion that are then spread to whoever read them. Knowledge is power as Foucault was insisting, imagination is, in fact, power to the same extent. The virtual access to other worlds via books is the possibility of a resistance in this given reality. For that, books have to be salvaged at any price. They constitute the archives of a civilization as much as they are the active agents of vitalization of a society that accepts the multiplicity of their narratives.

Tuesday, February 21. 2012

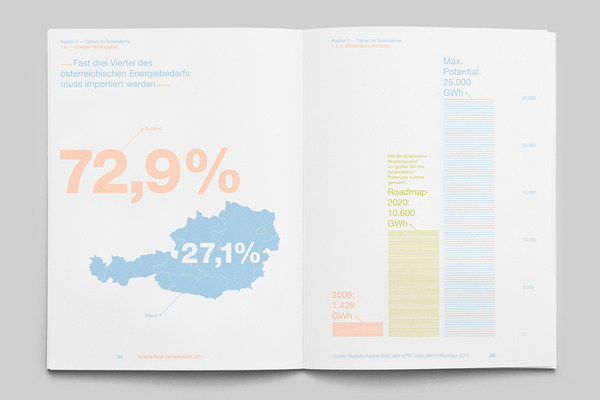

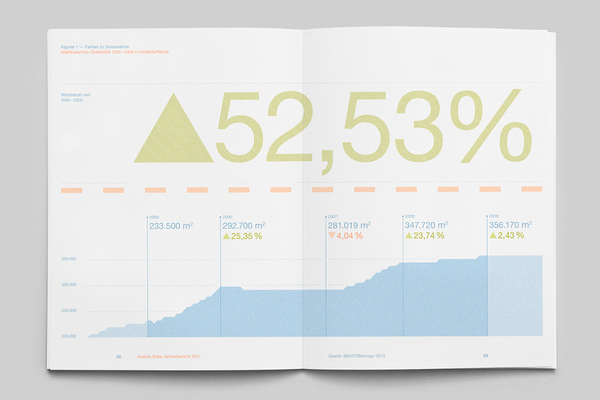

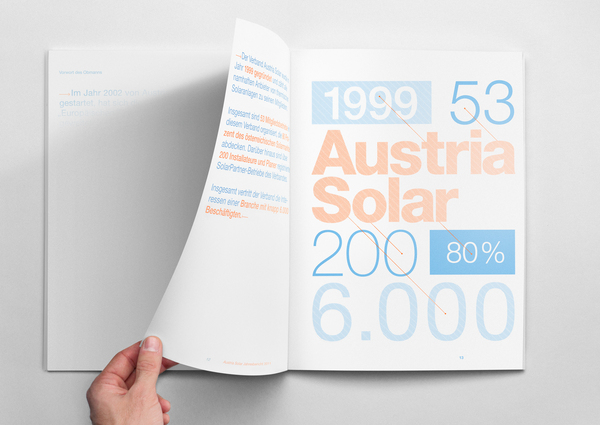

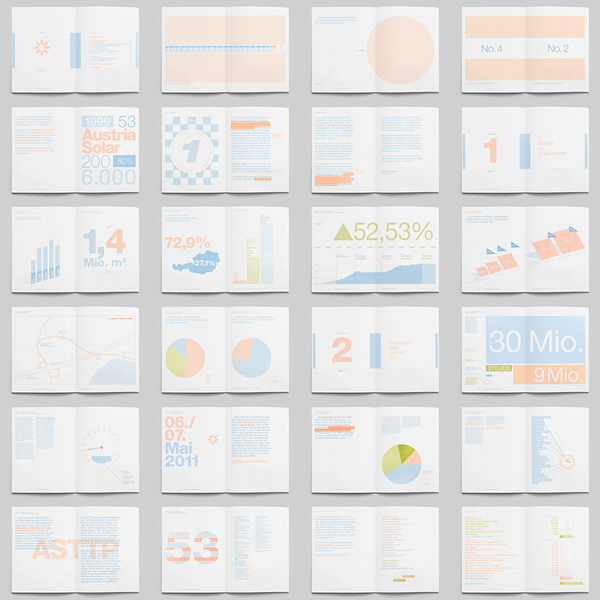

Le rapport annuel qui se révèle à la lumière du jour

Via Booketing

-----

L’association Austria Solar (regroupant des entreprises du secteur photovoltaïque), a demandé à l’agence Allemande, Service Plan de s’occuper de la création de leur rapport annuel. Ce sont les graphistes Matthäus Frost et Mathias Nösel qui ont travaillé sur ce projet pour le moins originale. Ils ont utilisé une encre spéciale qui permet l’apparition du contenu lorsque les pages réagissent avec les rayons du soleil. Plutôt astucieux ! Là où c’est fort, c’est que même dans une pièce éclairée, il ne se passe rien, c’est vraiment uniquement grâce à la lumière naturelle que le contenu se révèle.

Vous remarquerez donc une mise en page épurée, avec des infographies en trois couleurs. Afin de mieux vous rendre compte du résultat, vous pourrez découvrir à la suite, photos et vidéo. N’oublions pas de mentionner également le bon boulot de l’imprimeur, Mory & Meier.

Et pour finir, la vidéo qui montre la « transformation » en direct :

Personal comment:

Is this a basic phosphorescent ink (like there are also thermal inks that reacts to special temperatures) or a special one that seems to react only to the sun's light wavelength? In any case, it would be interesting to have colors/texts/patterns that appears only under very specific conditions (a very precise wavelength or temperature or when some particles are detected in the air). A low-fi "media facade" so to say.

Wednesday, February 01. 2012

Book Review: Programmed Visions: Software and Memory

ENIAC programmers, late 1940s. (U.S. military photo, Redstone Arsenal Archives, Huntsville, Alabama), from Programmed Visions by Wendy Hui Kyong Chun.

After “getting fit” and whatever else people typically declare to be their new year’s resolutions, this year’s most popular goal is surprisingly nerdy: learning to code. Within the first week of 2012, over 250,000 people, including New York’s mayor Michael Bloomberg, had signed up for weekly interactive programming lessons on a site called Code Year. The website promises to put its users “on the path to building great websites, games, and apps.” But as New Yorker web editor Blake Eskin writes, “The Code Year campaign also taps into deeper feelings of inadequacy... If you can code, the implicit promise is that you will not be wiped out by the enormous waves of digital change sweeping through our economy and society.”

If the entrepreneurs behind Code Year (and the masses of users they’ve signed up for lessons) are all hoping to ride the wave of digital change, Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, a professor of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University, is the academic trying to pause for a moment to take stock of the present situation and see where software is actually headed. All the frenzy about apps and “the cloud,” Chun argues, is just another turn in the “cycles of obsolescence and renewal” that define new media. The real change, which Chun lays out in her book Programmed Visions: Software and Memory, is that “programmability,” the logic of computers, has come to reach beyond screens into both the systems of government and economics and the metaphors we use to make sense of the world.

“Without [computers, human and mechanical],” writes Chun, “there would be no government, no corporations, no schools, no global marketplace, or, at the very least, they would be difficult to operate...Computers, understood as networked software and hardware machines, are—or perhaps more precisely set the grounds for—neoliberal governmental technologies...not simply through the problems (population genetics, bioinformatics, nuclear weapons, state welfare, and climate) they make it possible to both pose and solve, but also through their very logos, their embodiment of logic.”

To illustrate this logic, Chun draws extensively on history, theory, and detailed technical explanations, enriching cursory understandings of software. “Understanding software as a thing,” she writes, “means engaging its odd materializations and visualizations closely and refusing to reduce software to codes and algorithms—readily readable objects—by grappling with its simultaneous ambiguity and specificity.” Indeed, Chun spends a lot of time specifying computer terms. What's the difference between hardware, software, firmware, and wetware? Source code, compiled code, and written instructions? What is a thing and how did software become one? Even for a fairly nerdy computer user there’s a lot to pick up on. The book really shines, however, when Chun waxes poetic on the more ambiguous aspects of software.

The term “vaporware” refers to software that’s announced and advertised but never actually released for use, such as Ted Nelson’s infamous Xanadu project. Vaporware is problematic when it comes to theory because grand ideas and slick renderings rarely (if ever) align with the way technology looks and works in real life. Geert Lovink, Alexander Galloway, and others have called to banish “vapor theory,” theory built on hypothetical ideas about software rather than instantiations of it, which Lovink criticizes as, “gaseous flapping of the gums...generated with little exposure, much less involvement with those self-same technologies and artworks.” Chun concedes that while this embargo on vapor has been essential to grounding new media studies, “a rigorous engagement with software makes new media studies more, rather than less, vapory.” Vapor is not incidental to software, she argues, but actually essential to its understanding. This is what makes Chun’s theories exciting to follow: she engages renderings, dreams, and misunderstandings about technology rather than casting them aside. The key source of these misunderstandings is the use of the computer as metaphor.

People in previous generations conceptualized the world around them using technologies like clocks and steam engines. While these analog, mechanical devices are intricate, if one were to take apart a clock and and put it back together its inner workings could be understood. Digital computers are more complex because they are made of both tangible chips and immaterial codes, neither of which are intuitive to deconstruct. Further, all software interfaces, like the “paintbrush” tool in Photoshop, are metaphors themselves. “Who completely understands what one’s computer is actually doing at any given moment?” asks Chun, knowing that the answer is nobody. Yet this murky recursion of “unknowability” and vapors is exactly why Chun finds software to be such an apt metaphor for the world we live in. Recalling Stewart Brand’s call for a picture of the whole earth in 1968, Chun poses the question: what would a picture of the whole Internet look like? Except, in this case, to find out may not be the point. In the way that the stock market is based on speculation—virally spreading fear about the future of a company (as opposed to concrete evidence or actual bad management decisions) can cause a stock to tank—a technologized world is increasingly based on conjecture. In its unseeable, untouchable, and effectively unknowable nature, the computer represents the lens we need in order to think about the enormous and incomprehensible forces of social, economic, and political power that govern our lives. “[Software’s] ghostly interfaces embody—conceptually, metaphorically, virtually—a way to navigate our increasingly complex world,” writes Chun.

The book looks at a broad range of examples from artists, scholars, and technologists to situate “programmability” in relation to everything from global systems like capitalist economics, neoliberal politics, and knowledge production to those of the mind and body: gender, race, and the structure of thought. The footnotes are full of interesting paths waiting to be followed: Frederick P. Brooks on why programming is fun and hacking is addictive, Ben Shneiderman on direct manipulation interfaces, Brenda Laurel on computers as theatre and how that relates to skeuomorphism, and Thomas Y. Levin on the temporality of surveillance, to name just a few. While it’s tempting to look to this web of ideas and the history of computing as an answer for why things are the way they are today, Chun's point in invoking all these voices is that it’s not that clear cut.

Some of the book’s propositions about our relationship to computers seem overblown: a priestly source of power, a form of magic, code as a fetish. If nothing else, these phrases are provocative and point to how potent Chun finds software to be in the world today. As more and more people find themselves able to create things out of code, it feels critical to understand software on both a practical and fundamental level.

Related Links:

Wednesday, December 07. 2011

The Rounds

Via BLDGBLOG

-----

(...)

5) "Imagine a lush forest: silent but for the chirping of birds flying through a dense canopy overhead, and damp, aromatic earth underfoot. Now picture a mountain of incinerated trash, 12 million tons of what was once a toxic heap of rotting fish and vegetables, old clothes, broken furniture, diapers and all manner of discarded items." This describes a new project by architect Tadao Ando called the Sea Forest. The Sea Forest "will transform 88 hectares of reclaimed land, a 30-meter deep mound of alternating layers of landfill, into a dense forest of nearly half a million trees" in Tokyo Bay. Ando adds that it is also an experiment in climate-engineering, or weather control as the future of urban design: "not only will [the forest] become a refreshing retreat for stressed out city workers, it will also create a cool ocean breeze to sweep through the capital and cool its sweaty denizens in summer."

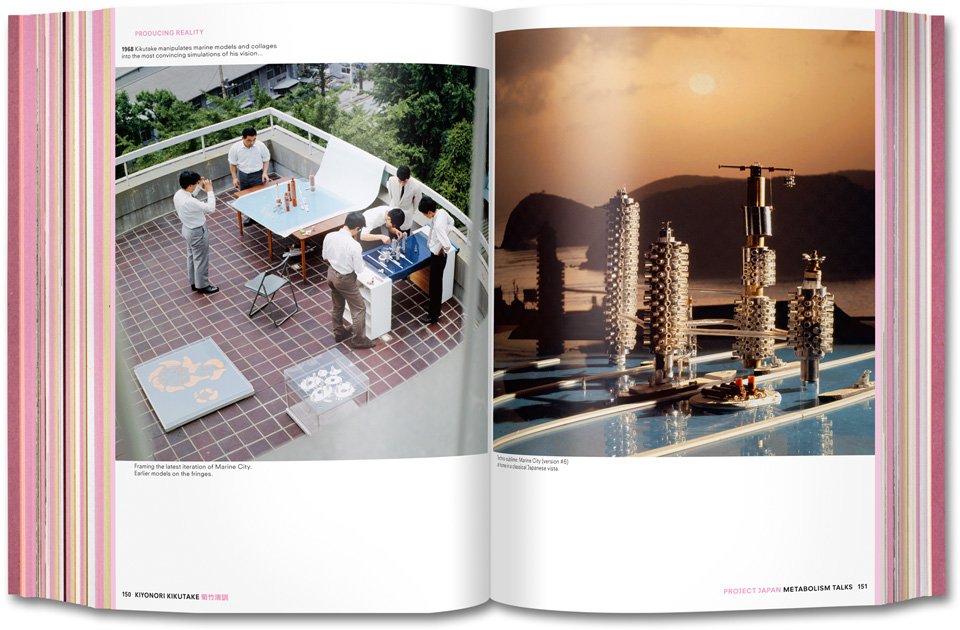

[Images: Spreads from Project Japan, courtesy of Taschen].

[Images: Spreads from Project Japan, courtesy of Taschen].

6) The new book Project Japan by Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist is an incredible document, in both physical and intellectual terms. The design, by Irma Boom, is gorgeous, and the contents—consisting of long, illustrated interviews with such figures as Arata Isozaki, Kenzo Tange's Tange Lab, Kiyonori Kikutake, Kisho Kurokawa, and many others, scattered amongst historical imagery and present-day site photos—offer a fascinating oral history of the Metabolist movement. As Koolhaas sums it up, Metabolism offered "a manifesto for the total transformation of the country" based on three specific principles. Still quoting Koolhaas:

a) The archipelago has run out of space: mostly mountainous, the surfaces fit for settlement are subdivided in microscopic, centuries old patchworks of ownership

b) Earthquakes and tsunamis make all construction precarious; urban concentrations such as Tokyo and Osaka are susceptible to potentially devastating wipeouts [ed. note: cf. today's calls for a "back-up Tokyo"]

c) Modern technology and design offer possibilities for transcending Japan's structural weakness, but only if they are mobilized systematically, almost militaristically, searching for solutions in every direction: on the land, on the sea, in the air...

Architecture thus becomes the literal geopolitical extension of the state, constructing new territory—such as floating forests and artificial islands—over which to govern. It's a kind of proactive gerrymandering, we might say: not redesigning the district map, but constructing new districts. In any case, I recommend the book.

(...)

Related Links:

fabric | rblg

This blog is the survey website of fabric | ch - studio for architecture, interaction and research.

We curate and reblog articles, researches, writings, exhibitions and projects that we notice and find interesting during our everyday practice and readings.

Most articles concern the intertwined fields of architecture, territory, art, interaction design, thinking and science. From time to time, we also publish documentation about our own work and research, immersed among these related resources and inspirations.

This website is used by fabric | ch as archive, references and resources. It is shared with all those interested in the same topics as we are, in the hope that they will also find valuable references and content in it.

Quicksearch

Categories

Calendar

|

|

July '25 | |||||

| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||