Wednesday, July 24. 2013

Via Archinect

-----

Smart city infrastructure can augment the ability of managers, planners, designers and engineers to define and implement a fundamentally better next generation of buildings, cities, regions — right? Maybe. For that to be a serious proposition, it’s going to have to be normal for planners and designers not only to collaborate productively with engineers, but to do so with the full and competent participation of the only people they mistrust more than each other ... customers.

"A city is not a BMW," writes Carl Skelton. "You can't drive it without knowing how it works." In a weighty think-piece on Places, he argues that the public needs new tools of citizenship to thrive in a "new soft world" increasingly shaped by smart meters, surveillance cameras, urban informatics and big data. "To be a citizen of a digital city requires understanding what the databases do and don’t contain, and what they could contain, and how the software used to process that data and drive design decisions does, doesn’t, and might yet perform."

Via Forbes

-----

By Anna Secino

Smart cities have been creating a lot of buzz lately—thanks, in no small part, to the recent controversy over NSA surveillance, which cast a rather sinister light over visions of cities made more efficient through data collection of public resources. “It starts with monitoring water usage,” the naysayers cry, “But where does it end?”

This past week, two cities—Montpellier, France, and Dallas, Texas—released statements concerning their own attempts towards smartening up their infrastructure, which got us thinking about “Informed and Interconnected: A Manifesto for Smarter Cities,” a 2009 paper by Harvard Business School Professor Rosabeth Moss Kanter and IBM IBM +0.03% International Foundation President Stanley S. Litow. Its thoughts on and solutions for smart cities continue to be relevant four years later, as the cases in Montpellier and Dallas attest to.

A major concern with regards to smart cities is figuring out who, exactly, is in charge of all this data collection? The government? The tech companies? As a city strives towards streamlined convergence, how does it avoid creating an especially unscrupulous monopoly? “It is important to note that new technologies have additional potential to make communities smarter by combining sets of data and making them available not only to immediate decision makers but to a much wider network of officials and agencies so that they can make more informed decisions,” Kanter and Litow write.

Michel Aslanian, Montpellier’s Vice President of Innovation, believes that he has found the answer through making the $5.4 million research and development project a joint effort among stockholders, universities, startups, public utility operators, and Montpellier everymen. “The citizen is being made the author and actor in the development of the region,” he said regarding the “Ecocité” initiative, which hopes to collect data on public transportation, water usage, and other factors of city life that could lead to a greener, more efficient future.

Other cities have not been quite so eager to jump on the bandwagon. In Dallas, where most corporate and municipal buildings operate on old, inefficient equipment, the switch to newer, more energy-efficient models has been ponderous. Europe requires that buildings be energy efficient, but U.S. politicians have been reluctant to pitch their support behind a similar initiative. And with the majority of office buildings dating back sixty to seventy years, updating existing structures can be costly. For all the money that cities and businesses waste every year through electricity, water, and other resources, many refuse to fund a never-ending progression of equipment repair.

Supporters of both Dallas’s tortoise and Montpellier’s hare may want to acquaint themselves with Kanter and Litow’s vision for a city where high-tech advances help build efficient, egalitarian communities. Via a streamlined, interconnected approach, they argue, there would be less exclusion of racial or ethnic groups, as communities gather strength through individual differences, united in their efforts towards a better quality of life. In this scenario, technology serves merely as a tool for enhancing the very human pursuits of social- and self-betterment, with the monetary cost far outweighed by the environmental and communal benefits.

To learn more about Kanter’s and Litow’s ideas for the snowballing smart city movement—including their list of the top eight problems commonly faced by smart cities, and how these can be avoided—read their full manifesto here, on the HBS Working Knowledge website.

About the author: Writer Anna Secino is a student at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Tuesday, July 23. 2013

Via MIT News

-----

Illustration: Christine Daniloff/MIT

The comic-book hero Superman uses his X-ray vision to spot bad guys lurking behind walls and other objects. Now we could all have X-ray vision, thanks to researchers at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.

Researchers have long attempted to build a device capable of seeing people through walls. However, previous efforts to develop such a system have involved the use of expensive and bulky radar technology that uses a part of the electromagnetic spectrum only available to the military.

Now a system being developed by Dina Katabi, a professor in MIT’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, and her graduate student Fadel Adib, could give all of us the ability to spot people in different rooms using low-cost Wi-Fi technology. “We wanted to create a device that is low-power, portable and simple enough for anyone to use, to give people the ability to see through walls and closed doors,” Katabi says.

The system, called “Wi-Vi,” is based on a concept similar to radar and sonar imaging. But in contrast to radar and sonar, it transmits a low-power Wi-Fi signal and uses its reflections to track moving humans. It can do so even if the humans are in closed rooms or hiding behind a wall.

As a Wi-Fi signal is transmitted at a wall, a portion of the signal penetrates through it, reflecting off any humans on the other side. However, only a tiny fraction of the signal makes it through to the other room, with the rest being reflected by the wall, or by other objects. “So we had to come up with a technology that could cancel out all these other reflections, and keep only those from the moving human body,” Katabi says.

Motion detector

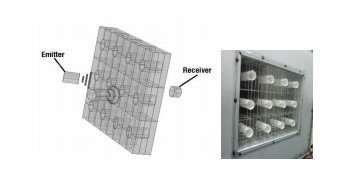

To do this, the system uses two transmit antennas and a single receiver. The two antennas transmit almost identical signals, except that the signal from the second antenna is the inverse of the first. As a result, the two signals interfere with each other in such a way as to cancel each other out. Since any static objects that the signals hit — including the wall — create identical reflections, they too are cancelled out by this nulling effect.

In this way, only those reflections that change between the two signals, such as those from a moving object, arrive back at the receiver, Adib says. “So, if the person moves behind the wall, all reflections from static objects are cancelled out, and the only thing registered by the device is the moving human.”

Once the system has cancelled out all of the reflections from static objects, it can then concentrate on tracking the person as he or she moves around the room. Most previous attempts to track moving targets through walls have done so using an array of spaced antennas, which each capture the signal reflected off a person moving through the environment. But this would be too expensive and bulky for use in a handheld device.

So instead Wi-Vi uses just one receiver. As the person moves through the room, his or her distance from the receiver changes, meaning the time it takes for the reflected signal to make its way back to the receiver changes too. The system then uses this information to calculate where the person is at any one time.

Possible uses in disaster recovery, personal safety, gaming

Wi-Vi, being presented at the Sigcomm conference in Hong Kong in August, could be used to help search-and-rescue teams to find survivors trapped in rubble after an earthquake, say, or to allow police officers to identify the number and movement of criminals within a building to avoid walking into an ambush.

It could also be used as a personal safety device, Katabi says: “If you are walking at night and you have the feeling that someone is following you, then you could use it to check if there is someone behind the fence or behind a corner.”

The device can also detect gestures or movements by a person standing behind a wall, such as a wave of the arm, Katabi says. This would allow it to be used as a gesture-based interface for controlling lighting or appliances within the home, such as turning off the lights in another room with a wave of the arm.

Venkat Padmanabhan, a principal researcher at Microsoft Research, says the possibility of using Wi-Vi as a gesture-based interface that does not require a line of sight between the user and the device itself is perhaps its most interesting application of all. “Such an interface could alter the face of gaming,” he says.

Unlike today’s interactive gaming devices, where users must stay in front of the console and its camera at all times, users could still interact with the system while in another room, for example. This could open up the possibility of more complex and interesting games, Katabi says.

Personal comment:

This will probably restart the interests of private companies to provide "public" or private wifi "for free" or at least to equip large urban areas without charging for the work and the hardware (as you won't need to be connected to the wifi to be tracked, see?). As long as they'll be allowed to collect data, mine for crowd patterns and behaviors... (a new case for persons in charge of data protection).

Tuesday, July 09. 2013

Via MIT Technology Review

-----

By exploiting some exotic acoustic techniques, researchers have built a window that allows the passage of air but not sound

Noise pollution is one of the bugbears of modern life. The sound of machinery, engines, neighbours and the like can seriously affect our quality of life and that of the other creatures that share this planet.

But insulating against sound is a difficult and expensive business. Soundproofing generally works on the principle of transferring sound from the air into another medium which absorbs and attenuates it.

So the notion of creating a barrier that absorbs sound while allowing the free of passage of air seems, at first thought, entirely impossible. But that’s exactly what Sang-Hoon Kima at the Mokpo National Maritime University in South Korea and Seong-Hyun Lee at the Korea Institute of Machinery and Materials, have achieved.

These guys have come up with a way to separate sound from the air in which it travels and then to attenuate it. This has allowed them to build a window that allows air to flow but not sound.

The design is relatively simple and relies on two exotic acoustic phenomenon. The first is to create a material with a negative bulk modulus.

A material’s bulk modulus is essentially its resistance to compression and this is an important factor in determining the speed at which sound moves through it. A material with a negative bulk modulus exponentially attenuates any sound passing through it.

However, it’s hard to imagine a solid material having a negative bulk modulus, which is where a bit of clever design comes in handy.

Kima and Lee’s idea is to design a sound resonance chamber in which the resonant forces oppose any compression. With careful design, this leads to a negative bulk modulus for a certain range of frequencies.

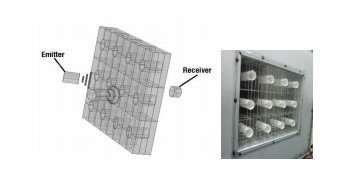

Their resonance chamber is actually very simple—it consists of two parallel plates of transparent acrylic plastic about 150 millimetres square and separated by 40 millimetres, rather like a section of double-glazing about the size of a paperback book.

This chamber is designed to ensure that any sound resonating inside it acts against the way the same sound compresses the chamber. When this happens the bulk modulus of the entire chamber is negative.

An important factor in this is how efficiently the sound can get into the chamber and here Kima and Lee have another trick. To maximise this efficiency, they drill a 50 millimetre hole through each piece of acrylic. This acts as a diffraction element causing any sound that hits the chamber to diffract strongly into it.

The result is a double-glazed window with a negative bulk modulus that strongly attenuates the sound hitting it.

Kima and Lee use their double-glazing unit as a building block to create larger windows. In tests with a 3x4x3 “wall” of building blocks, they say their window reduces sound levels by 20-35 decibels over a sound range of 700 Hz to 2,200 Hz. That’s a significant reduction.

And by using extra building blocks with smaller holes, they can extend this range to cover lower frequencies.

What’s handy about these windows is that holes through them also allow the free flow of air, giving ample ventilation as well.

The applications are many. Changing the size of the holes makes the windows tunable so they screen out only certain frequencies, the new designs have some interesting applications.

“For example, if we are in a combined area of sounds from sea waves of low frequency and noises from machine operating at a high frequency, we can hear only the sounds from sea waves with fresh air,” say Kima and Lee.

What’s more, they say the same idea should also work in water which could help in applications such as protecting marine animals from noise pollution.

A clever idea that tackles one of the increasingly common problems of modern living.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1307.0301: Air Transparent Soundproof Window.

Monday, July 01. 2013

Via Archinect

-----

A New Exhibit Reveals How Building Went Digital... And Why You Should Care.

As a revealing new exhibit at the Canadian Centre for Architecture shows, ambivalence about digital architecture was characteristic of most of the architects who pioneered it, including Peter Eisenman, Chuck Hoberman and Shoei Yoh. “The computer has become an opportunistic gadget for most of the profession,” Gehry tells the architect-cum-curator Greg Lynn (note: with all my respect, including for Gehry?) in an interview for the exhibition catalogue.

|