Thursday, October 28. 2010

via Cyber Badger Research Blog

--

We [ Martin Dodge & Rob Kitchin ] are just checking the page proofs for our book Code/Space that is nearing publication after a somewhat slow production process through much of this year.

The book has an ISBN and is now listed on the MIT Press website, although we are waiting to see what cover design is going to be applied.

Code/Space is structured in four sections and has eleven chapters:

- I Introduction

- 1 Introducing Code/Space

- 2 The Nature of Software

- II The Difference Software Makes

- 3 Remaking Everyday Objects

- 4 The Transduction of Space

- 5 Automated Management

- 6 Software, Empowerment, and Creativity

- III The Transduction of Everyday Spatialities

- 7 Air Travel

- 8 Home

- 9 Consumption

- IV Future Code/Space

- 10 The Promise of Everyware

- 11 A Manifesto for Software Studies

- Brief Glossary of Concepts

- References

- Index

More details on our ongoing research on code/space and various published papers are listed on this webpage.

Monday, October 25. 2010

Via Mashable

-----

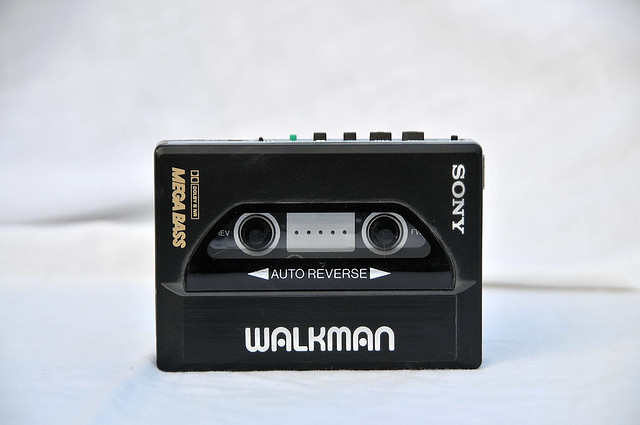

After retiring the floppy disk in March, Sony has halted the manufacture and distribution of another now-obsolete technology: the cassette Walkman, the first low-cost, portable music player.

The final batch was shipped to Japanese retailers in April, according to IT Media. Once these units are sold, new cassette Walkmans will no longer be available through the manufacturer.

The first generation Walkman (which was called the Soundabout in the U.S., and the Stowaway in the UK) was released on July 1, 1979 in Japan. Although it later became a huge success, it only sold 3,000 units in its first month. Sony managed to sell some 200 million iterations of the cassette Walkman over the product line’s 30-year career.

Somewhat ironically, the announcement was delivered just one day ahead of the iPod’s ninth anniversary on October 23, although the decline of the cassette Walkman is attributed primarily to the explosive popularity of CD players in the ’90s, not the iPod.

Personal comment:

R.I.P. the "cassette walkman". I thought it was already gone for years! Now this is the occasion to light up a candle.

-----

Remember the movie Lawnmower Man? Here's why we're not even close.

The early 90's were awesome. Bill Watterson was still drawing Calvin and Hobbes, the tattered remnants of the Cold War were falling down around our ears, and most of Wall Street was convinced the Macintosh was a computer for effete graphic designers and Apple was more or less on its way out.

Into this time of innocence came a radical vision of the future, epitomized by the movie Lawnmower Man. It was a future in which Hollywood starlets had virtual intercourse with developmentally challenged computer geeks in Tron-style bodysuits and everything looked like it was rendered by a Commodore Amiga.

Anyway, at that time Virtual Reality was a Big Deal. Jaron Lanier, the computer scientist most closely associated with the idea, was bouncing from one important position to another, developing virtual worlds with head mounted displays and, later, heading up the National Tele-immersion initiative, "a coalition of research universities studying advanced applications for Internet 2," whatever the heck that was.

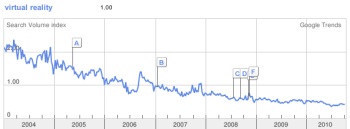

|

Google Trend shows the steady decline in searches for "Virtual Reality" |

Even so, some sensed that the technology wasn't bringing about the revolution that had been promised. In a 1993 column for Wired that earns a 9 out of 10 for hilarity and a 2 out of 10 for accuracy, Nicholas Negroponte, founder of the MIT Media Lab (who I'm praying will have a sense of humor about this) asked the question that was on everyone's mind: Virtual Reality: Oxymoron or Pleonasm?

It didn't matter if anyone knew what he was talking about, because time has proved most of it to be nonsense:

"The argument will be made that head-mounted displays are not acceptable because people feel silly wearing them. The same was once said about stereo headphones. If Sony's Akio Morita had not insisted on marketing the damn things, we might not have the Walkman today. I expect that within the next five years more than one in ten people will wear head-mounted computer displays while traveling in buses, trains, and planes.... One company, whose name I am obliged to omit, will soon introduce a VR display system with a parts cost of less than US$25."

Affordable VR headsets were just around the corner, really? And the only real barrier to adoption, according to Negroponte? Lag. Computers in 1993 just weren't fast enough to react in real time when a user turned his or her head, breaking the illusion of the virtual.

According to Moore's Law, we've gone through something like 10 doublings of computer power since 1993, so computers should be about a thousand times as powerful as they were when this piece was written - not to mention the advances in massively parallel graphics processing brought about by the widespread adoption of GPUs, and we're still not there.

So what was it, really, that kept us from getting to Virtual Reality?

For one thing, we moved the goal posts - now it's all about augmented reality, in which the virtual is laid over the real. Now you have a whole new set of problems - how do you make the virtual line up perfectly with the real when your head has six degrees of freedom and you're outside where there aren't many spatial referents for your computer to latch onto?

And most important of all, how do you develop screens tiny enough to present the same resolution as a large computer monitor, but in something like 1/400th the space? This is exactly the problem that has plagued the industry leader in display headsets, Vuzix. Their products are fine for watching movies, but don't try using them as a monitor replacement.

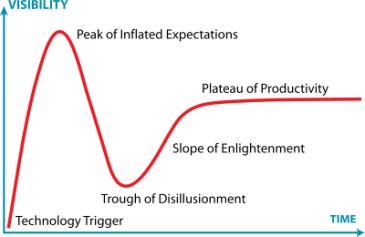

Consumer-level Virtual Reality, it turns out, is really, really hard - not quite Artificial Intelligence hard, but so much harder than anyone expected that people just aren't excited anymore. The Trough of Disillusionment on this technology is deep and long.

That doesn't mean Virtual Reality is gone forever - remember how many false starts touch computing had before technologists succeeded with, of all things, a phone?

And, just a coda, even though the public long ago gave up on searching for Virtual Reality, the news media never got tired of it. Which just shows you how totally out of touch we can be:

Thursday, October 07. 2010

How Globalization Is Bad for the World Economy

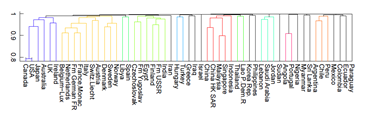

Evolutionary theory predicts that globalization should increase the risk of recession and slow recovery rates, a phenomenon borne out by real data, say econophysicists.

Biologists have long puzzled over the modular structure of living things, a module being a structure that can function relatively independently from other parts of the system. So a module might be an ecology, a society within that ecology, an individual animal, an organ, a cell within that organ, a gene within that cell, and so on.

Nature simply wreaks of modularity throughout its hierarchy. The question, until recently, was why. A couple of years back, Jun Sun and Michael Deem, a couple of of physicists at Rice University in Houston, came up with an answer. They said modularity allows a system to more easily evolve and reduces the chances of catastrophic collapse due to some kind of outside influence, such as climate change or disease.

They went to show that modularity emerges spontaneously in a evolutionary algorithms that change relatively slowly and swap information.

Today Deem and Jiankui He, also at Rice, apply this idea to the global trade network. Their hypothesis is that this network evolves in exactly the same way as natural systems, or at least, that it is constrained in the same way by the rate at which it changes, the fact that information flows within it.

That implies that modular structures ought to form spontaneously on all kinds of scales within this network. And indeed they do in the form of companies, trade groups, countries and so on.

However, globalization is a process that reduces modularity because it encourages an equality of trade between entities in different parts of the world. But in naturally evolved systems, far from increasing the robustness of the system to perturbations, a drop in modularity decreases it. Deem and He hypothesise that the same thing happens in the gobal trade network.

What's surprising is that their idea is actually borne out by the data. They've studied the nature of various global recessions since 1969 and say that the increase in globalization makes the global economy less stable. What's more, when a recession does hit, the recovery becomes slower as globalization increases.

The explanation is that modularity allows a hierarchy to form within a system and this helps a system to recover when trouble strikes. If this structure is absent or reduced in form, then the recovery is slower. Globalization seems to discourage the formation of the kind of trade groups that would form these structures.

Deem and He say the global economy is actually more fragile today than it was 40 years ago.

They also make a prediction. They say that a recession should encourage the formation hierarchies at least temporarily. What they mean is the formation of trade groups who trade preferentially with each other.

That doesn't sound too far fetched and given that the global economy is currently attempting to lift itself out of recession it shouldn't be too hard to test either.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1010.0410: Structure and Response in the World Trade Network

Personal comment:

Again, how globalization is considered to create depletion (in societies, ecologies, culture, etc.). And it looks to be true in most contexts.

On the other side, if we try to look for positive things, globalization and somehow the possibility to be mobile both physically and virtually also creates knowledge (the possibility to discover and experience other cultures, biotopes & enviroments, spaces, climates, contents, etc.) and miscgenation/creolization (a "recent" type of culture and spaces that is far from depletion). It does create (interesting things) too.

We won't go back to a fully "local world" I believe (would you like to be stuck in your little fragment of the world again? I don't and probably most people that went mobile and discovered others won't), as the globe is shrinking for centuries now.

So, the challenge would be rather to develop a "sustainable and culturally diversified/diversifying hyper localization --in the sense of a very connected (both immaterially and physically) local environment--, with all sorts of mobile and immobile --in the sense of mediated-- mobilities". At least this is what we are working on and trying to do at fabric | ch.

The concepts of "modules" and "modularity" in this article from the MIT, the flow of information within it and with its environment, etc. even if taken from economic's theory... is therefore quite interesting when one starts to think about "very connected local environment".

|